Introduction

Since the turn of the 21st Century China has faced a growing problem of polluted water in its lake’s rivers and minor waterways, reaching a point where most policy makers began to accept river and lake pollution was impacting the ability of the nation to supply clean drinking water. Many attributed the situation to central and local governments prioritising economic development over environmental protection, tensions between central and local levels of government, and the complexity of the institutional structures surrounding the management of rivers and lakes across the country.

This situation took on added importance as attempts to address ecological issues (including water pollution), going back to the 1988 First Water Law, had failed to improve the situation. The goal of the Water Law was to develop an Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) system; designed to coordinate the ‘development and management of water, land, and related resources.’ The overall idea was to maximize productive use of natural resources (particularly water) ‘without compromising the sustainability of ecosystems’ (Li, Tong, and Wang 2020, 3). Despite the IWRM it was argued as late as 2007 that ‘China’s greatest development challenges…are in the areas where a dense population pushes up against the limits of water and what the land can provide’. (Naughton 2007, 30). This view was reinforced in 2010 when it was reported that just under half of China’s water was too polluted to be ‘made safe for drinking’ while of quarter was so polluted that it was ‘unfit even for industrial use’ (Stanway 2010, 1).

Since 2010 a range of policies have been implemented to deal with this situation, including the creation of Seven River Conservancy Commissions to engage in river basin management and the development (combination and recombination) of series of ministries and departments to address environmental pollution and degradation. The most recent attempt to address the nations polluted waterways and lakes occurred in December 2016, when the General Office of the Chinese Central Committee and the State Council issued The Options on Full Implementation of the River Chief System (RCS) Across the Country. The intent behind Options was not only to fully implemented the river chief system across all provinces, autonomous regions, and directly administered municipalities by 2018, but to bring the nations drinking water supply quality to no worse than category III.

Based on the river chef model established in the Options Erik Solheim, UN Under Secretary General and Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme, commented ‘I’m convinced that what I have seen in Pujiang County and Anji County will be the future of China, even the future of the world’ (cited in Xianqiang 2021, 435; emphasis added). It is to this observation that the reminder of this article will be directed. Specifically, the article will be divided into four sections. The first will provide a history of water pollution in China and why it became an issue needing a new approach based on the structure of the Chinese party-state administrative arrangements. The second section will provide a summary of the transfer and spread of the River Chief System before the passage of the Options and a brief discussion of the subsequent establishment of the national program. The third section will examine some of the issues that have emerged as a result of how the River Chief System operates at the local level (i.e., Provinces – Townships). The final section will discuss the likelihood of the River Chief System transferring to other nations, particularly considering the unique party-state structures that underpin the decision-making processes that led to the development and spread of the river chief system across China.

Basis of the Problem

China’s rivers and lakes were facing an environmental disaster by the early part of the 21st Century. This crisis encompassed issues such as water security, water shortages, a degradation of the overall river and lake ecosystem, and the impact water pollution was having on all of this.

1 Part of the problem can be seen in statistics that indicated that by 2020 (even after the implementation of the river chief system) almost two-thirds of China’s cities were suffering from some degree of water scarcity, with one-sixth suffering severe scarcity. While the rapid industrialization and urbanisation of the nation offers part of the explanation for scarcity (in the dryer parts of the Nation), it also helped to account for the situation where ‘Pollution in rivers and lakes in China is common, with 75% of the lakes showing varying degrees of eutrophication, and 30% of the water quality of the lakes in the V category, making it impossible to use directly’ (Wang, Wan, and Zhu 2021, 1436).

2 This problem is not only due to point and non-point pollution

3 reaching the nations waterways but by ‘inter-governmental rivalries [over water resources], corruption, and incentives that [traditionally] favor economic development over sustainable resource use...at local levels of government’ (Moor 2013, 1).

As alluded to, part of the issue of water pollution has been self-generated due to the complex nature of the bureaucracy associated with environmental regulation and control. Thus, at a minimum, the National People’s Congress has delegated issues of water management, pollution, and control to the: Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP); Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE); Ministry of Water Resources (MWR); Ministry of Land Resources; Ministry of Natural Resources; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs; and the Ministry of Finance. Because of this complex arrangement, not only is there competition between ministries for jurisdiction and prestige, but responsibilities for specific water related issues tends to be associated with different ministries, making it difficult to hold anyone unit or official responsible for the nations water ecosystem. More problematically, as turf fights occur, responsibility for different aspects of water management get shifted around, particularly when the government decides to re-organised, combined, and create new ministries or departments.

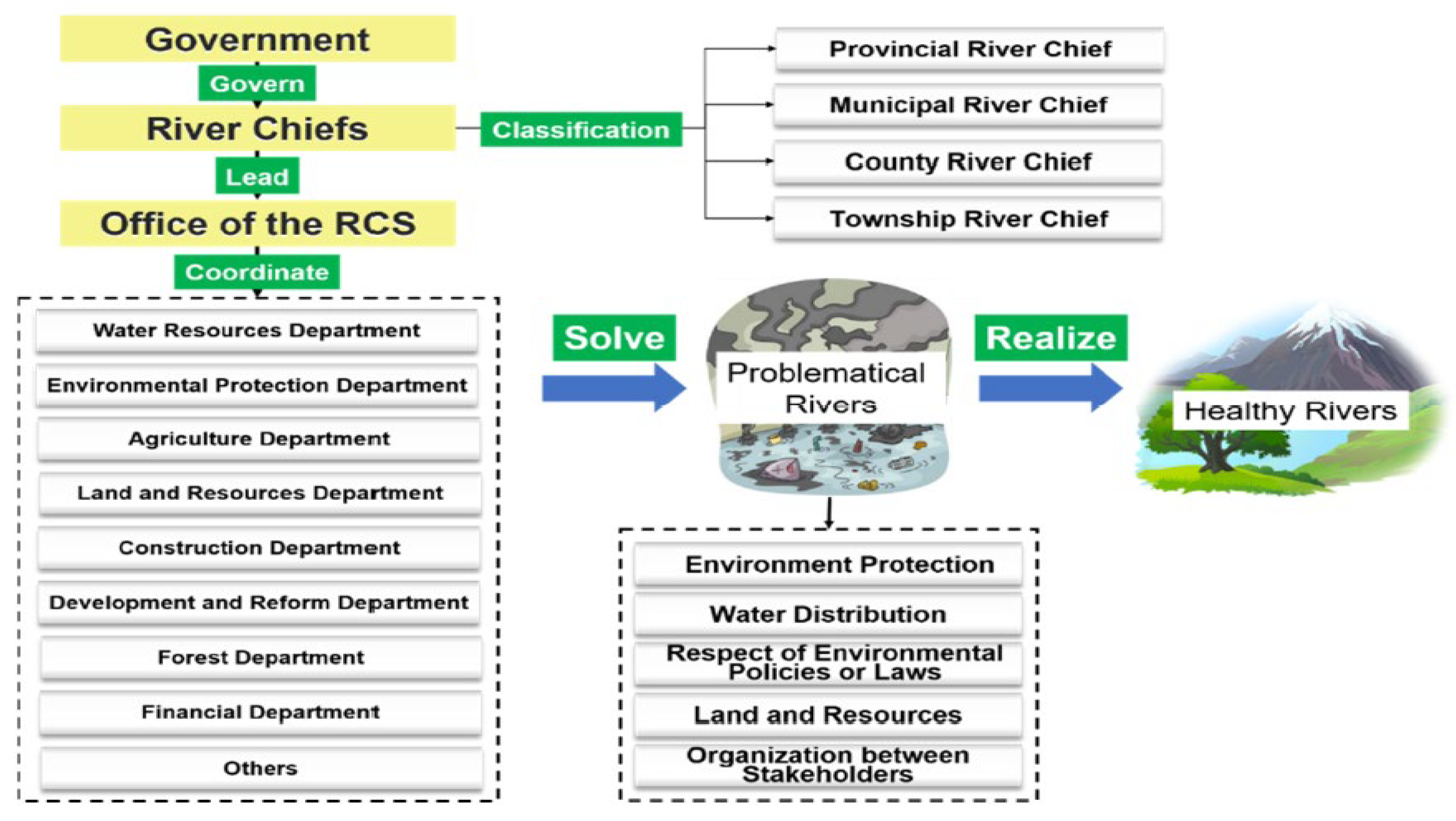

Complicating this picture even further are the range of departments associated with water policy that operate under these ministries across the different levels of local government. These include but are not limited to the provincial level departments such as: Water Resources Department; the Environmental Protection Department; the Agriculture Department; the Land Resources Department; Construction Department; Development and Reform Department; Forest Department and the Financial Department. This complex organisational matrix of responsibility led Silveira (2014) to conclude that fragmentation not only impacted on the nations water policy but that it had a significant ‘detrimental effect on the institutional capacity of the governance system to respond to water quality degradation’ but that when pollution events do occur it takes a considerably longer time to respond than would be the case for a more integrated system (Die 2019, 72).

This complex bureaucratic arrangement is further muddled due to the way the Chinese party-state governing system operates. Briefly, the party-state hierarchy has been developed to ensure that the rules and guidelines passed by the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the central ministries are effectively (at least on paper) implemented by lower level governing units in a hierarchy of power running down from Beijing to the province to the city to the county and finally the township (and in relation to the river chief system, villages, in 29 provinces). The power relations in the hierarchy are maintained through the appointment and appraisal processes where the leaders of lower-level governments are appointed (or removed) by the leaders of the superior government. These decisions are generally made based on performance assessments by the leaders of the higher-level governments (Chien & Hong 2018). This assessment structure can partially explain the poor conditions of the national water system as it has traditionally been biased toward economic development (regional GDP). Thus, the environment in general, and water quality more specifically, were rarely considered in performance reviews since the water ecosystem did not figure into previous conceptions of economic development at the local level.

This is further complicated by the mixing of party and government functions and positions (often referred to the ‘party and government on one shoulder-pole’, so that in some areas both party and government offices are responsible for overseeing the same policy area. It is also the case that sometimes the same official might hold both positions. This overlap makes it far less transparent when attempting to hold an office or individual within the government responsible for different aspects of water quality and environment.

History

China’s most recent drive to address its growing water issues can be traced back to the 1988 Water Law calling for ‘rationally developing, utilizing, and protecting water resources, preventing, and controlling water disasters’ (Water Law of the People’s Republic of China - 1988, Article 1). The core idea behind the Water Law was to create a system to better manage and monitor the nations waterways with legally binding enforcement mechanisms. In 2002 the Water Law was augmented to address some of the issues mentioned above, including a provision designed to combine water resource management with river basin and regional administrative management in an attempt to better integrate water resource management into the system (Global Water Partnership, 2015).

While there were other attempts to address water pollution between 1988 and 2004, the core to this article occurred in 2005 when President Hu Jintao directly addressed the need to consider the state of the nation’s ecology (particular its waterways), calling for: ‘a renewed environmental system of supervision and management – guojia jiancha (state supervision), difang jianguan (inspection and management by local governments), danwei fuze (units responsible)’ (Hunan 2011, 141). More importantly, President Hu’s call occurred at a symposium on population, resources and environment that was organised by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Bringing ecological issues to the forefront of the debate was a first step in recognising the need for central action in the area of water management. The importance that was beginning to be attached to environmentally friendly development was further integrated into the national discourse in 2006 with Premier Wen Jiabao’s address to the Sixth National Environmental Conference where he called for a ‘fairer, greener economy’.

All of this was amplified in 2008 when the Government issued the

Water Pollution Law. This law was an attempt to strengthen legislation related to water pollution thought the inclusion of substantial fines and penalties for businesses caught polluting waterways (Xinhua 2008). Around this time the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) (itself based on the US EPA which has historic to ties to its Chinese counterpart; see

https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/international-cooperation/epa-collaboration-china_.html), established a series of Regional Supervision Centers for Environmental Protection with the goal of improving ‘vertical supervision’ of existing environmental related legislation. More directly, at this time, the Ministry of Water Resources (MWR) created water quality bureaus within the existing river basin commissions (Moore 2013). Not only was Wen Jiabao concerned with the environment and the state of the nation’s water quality but so too was Xi Jinping, who as early as 2003 started to express concerns about the environment while he was the provincial leader (Party Secretary) of Zhejang Province. In fact, On Aug. 15, 2005, Xi Jinping, while on a visit to Anji, notably said that ‘lucid waters and lush mountains are as invaluable as silver and gold’ to China’s future (Solheim 2023, 1). This concern was carried forward to his Premiership where in his 2017 New Year’s message he laid out that ‘every river in China should have a River Chief’ to be responsible for its restoration and protection (Hao and Wan 2023).

While the political focus helped to bring water quality issues onto the agenda it was taken a step further in 2011 when the ‘three red lines’ policy was passed, placing water at the core of the increasingly ecological focus of the government. Briefly the three lines were designed to 1) control the amount of water used in the country 2) increase the efficiency of water used 3) reduce and limit the discharge of sewage into the water supply. The overall goal was to ensure that that 95% of tested water met national water quality guidelines of no worse than Level IV criteria. Then in 2015 the Water Pollution and Control Action Plan (Water Ten Plan) was implemented. The goal of this plan (which was devised with the input of over 12 ministries and departments) was to establish 10 goals (and 38 sub-goals) with deadlines and specific responsible units assigned to each (Tang et al. 2022). The overall aim was to prioritize water conservation with a ‘science-based’ treatment of the water flowing in rivers, lakes and ultimately the coastal seas. Unlike the river chief system, the idea was to bring in market mechanism for pollution prevention of the nation’s waterways but like the river chiefs it also had provisions to include the public in pollution control. The legislation also encouraged industry and governments to develop and implement advance systematic water pollution prevention and control mechanisms, that could be shown to protect the water ecosystem (Some of which have been utilised by a number of river chief systems; Tang et al. 2022).

Rise of the River Chief System

While these changes were occurring at the central level local level experiments were also occurring that addressed water quality issues, problems created by cross departmental responsibilities, intergovernmental issues (e.g., focus on GDP growth at the expense of the environment), and cross jurisdictional problems associated with rivers and lakes flowing across different provinces and townships.

While the origin of the river chief (

He-Zhang) system is slightly in dispute,

4 there is little doubt that in 2007 pollution flowing into Taihu Lake from feeder rivers caused a massive cyanobacteria (blue algae) outbreak that threatened Wuxi City’s drinking water supply. In response Wuxi issued the

River Cross Section Water Quality Control Goals and Assessment Method in Wuxi (trial version). The core idea of the trial was to establish a ‘river chief system’ that held named party and government officials (the chief executive of each county) accountable for monitoring, managing, and restoring the water quality in the different river-cross sections that fed into the lake. More importantly, the named individuals would have the results of water quality monitoring included in their performance evaluation by higher level governing authorities in addition to existing growth criteria.

Wuxi officials utilized this accountability system to address issues the governing structures created in the area of water quality control and management; particularly the freedom officials had to shift blame to other levels of administration or bureaucratic departments and the lack of water quality being an official element of the annual evaluation process of local officials. Recall, just some of the departments involved in water management at the sub-national level include the Water Conservancy Department, Environmental Protection Bureau, Economy and Trade Bureau, Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Bureau of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, Development and Reform Bureau, and even the Health Bureau. This crowed field led to a situation where local water management was ‘under the leadership of and accountable to both local governors and various vertical departments. [as a result] When the local water pollution control is not effective, though the local governors are accountable for this, they would shirk...their responsibility towards the departments in the vertical line. Therefore...local governors are not motivated to take responsibilities in water pollution control’ (Hao and Wan 2023, 12, emphasis in the original).

Complicating the picture prior to the advent of the river chief system, in Wuxi, the source of water pollution proved difficult to establish, and thus difficult to assess who should be held responsible: ‘When a river flows through different administrative areas, there are a series of conflicts...among local governments... concerning arguments over upstream or downstream, left banks or right banks, and main stream or tributaries’ (Hao and Wan 2023, 13). To address these (and other) issues that arose out of the traditional Tiara-Kuai governing structure, Wuxi established river chiefs to monitor and take direct responsibility for 64 (79 in total) major rivers sections in the area based on annual water quality targets, including the restoration of the overall ecology of the water environment. The principle being that those who achieved their targets would be rewarded with money and/or promotion. Those who failed to achieve their assigned targets (or be able to show signs of improvement) would be punished though fines or even the loss of promotional prospects. As stated by the CPC Wuxi Committee, for anyone not achieving their stated targets:

the Organizational Department (of the CPC), after an investigation, will veto the relevant leadership when they participate in a city-level competition for an effective leading group, or veto the relevant responsible officials when they participate in the competition for advanced or excellent individuals, or veto the promotion of those directly responsible officials. (Tai Hu Net 2016).

Within a year of the start of the trial river chief system it became clear that considerable improvements in water were being seen in Wuxi. At the time it was reported that ‘the overall compliance rate (i.e., those reaching required water quality) increased from 53.2 percent to 71.1percent’ (Donnellon-May 2023). This success quickly brought the Wuxi experiment to the attention of other administrative units in and outside of Jiangsu.

Movement of the River Chief System

Based on Wuxi’s ‘accomplishment’ in cleaning river and lake pollution and bringing formal accountability to the system of water management, other jurisdictions began looking to Wuxi as a model or using it as the basis of their own experiments with river chief systems (Zhang et al. 2022). While some of the cities and towns in Jiangsu province followed Wuxi with the implementation of their own river chief systems, the General Office of Jiangsu Provincial Government issuing the Notice on the Implementation of the Dual RLS in the Main Tributaries of Taihu Lake in 2008, the river chief system was officially promoted by the Jiangsu government as a policy across the province. In 2012 after multiple evaluations of the river chief system, Jiangsu Provincial officials adopted the river chief system as an endorsed policy across the province. In doing this, Jiangsu administrators vertically drew upon models that had been developed across Jiangsu (based in horizontal transfer from Wuxi). While not a complete list, some of the models discussed in the literature and by our interviewees as impacting the Jiangsu ‘model’ were those being used in Wuxi, Suqian and Shzhou.

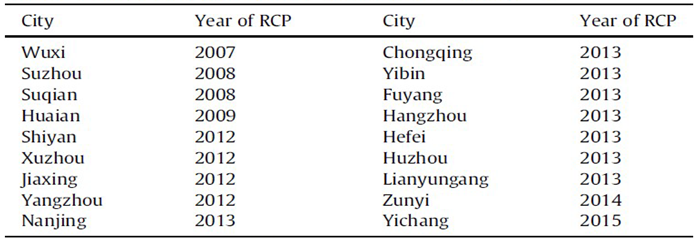

After the original Wuxi model appeared successful, the idea of the river chief system was quickly adapted and implemented in cities within Zhejiang and Jiangxi provinces (2007) and across city (municipal), county and watershed levels in; Henan, Liaoning and Yunnan provinces (2008); Guizhou and Hubei provinces (2009); Anhui, Zhejiang and Tianjin provinces (2013); Beijing and Fujian. For an illustration of how the river chef system spread from city-to-city and across provinces in the six years after the Wuxi model was developed see

Table 1, which illustrates the spread of the river chief system across the Yagtze river belt.

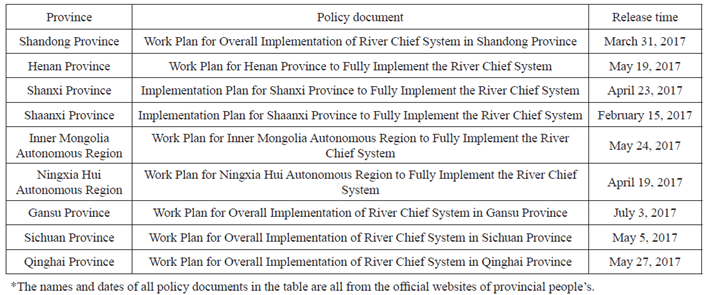

In a similar way,

Table 2 illustrates the way the river chief system spread across the Yellow River Basin immediately following the passage of the

Options on Comprehensively implementing the River Chief System.

While only tangentially referenced in an interview (respondent requested anonymity) it is worth noting that the relatively rapid spread of the river chief system appears to have emerged partially out of the same system that had led to its cause, ‘the party-state’. In brief, it was suggested that not only were officials aware of the reform as it was being developed but as party members, they were actively following developments (Interview W).

While the river chief system was spreading endogenous from city-to-city and province-to-province, in 2014 the Ministry of Water Resources issued the

Guidance Opinions on Strengthening the Management of Rivers and Lakes. This guidance was based on the collective experience of the emerging river chief system and made ‘explicit the requirement that local governments should contribute new ideas on rivers and lakes management, and that local government should promote and implement RCS’ (Xianqiang 2021 4). In total the river chief system transferred from Jiangsu Province to 25 other provinces before it was taken up by the General Office of the CPC Central Committee of the State Council, which issued

Opinions on the Full Implementation of River Chief System as a national policy in November 2016. This was followed up a year later with the issuance of the

Guidance Opinions on Implementing RCS in Rivers and Lakes that required all 31 provinces (including autonomous regions and directly administered municipalities) develop a river chief system to be administered at the provincial, city, county, and township level (see

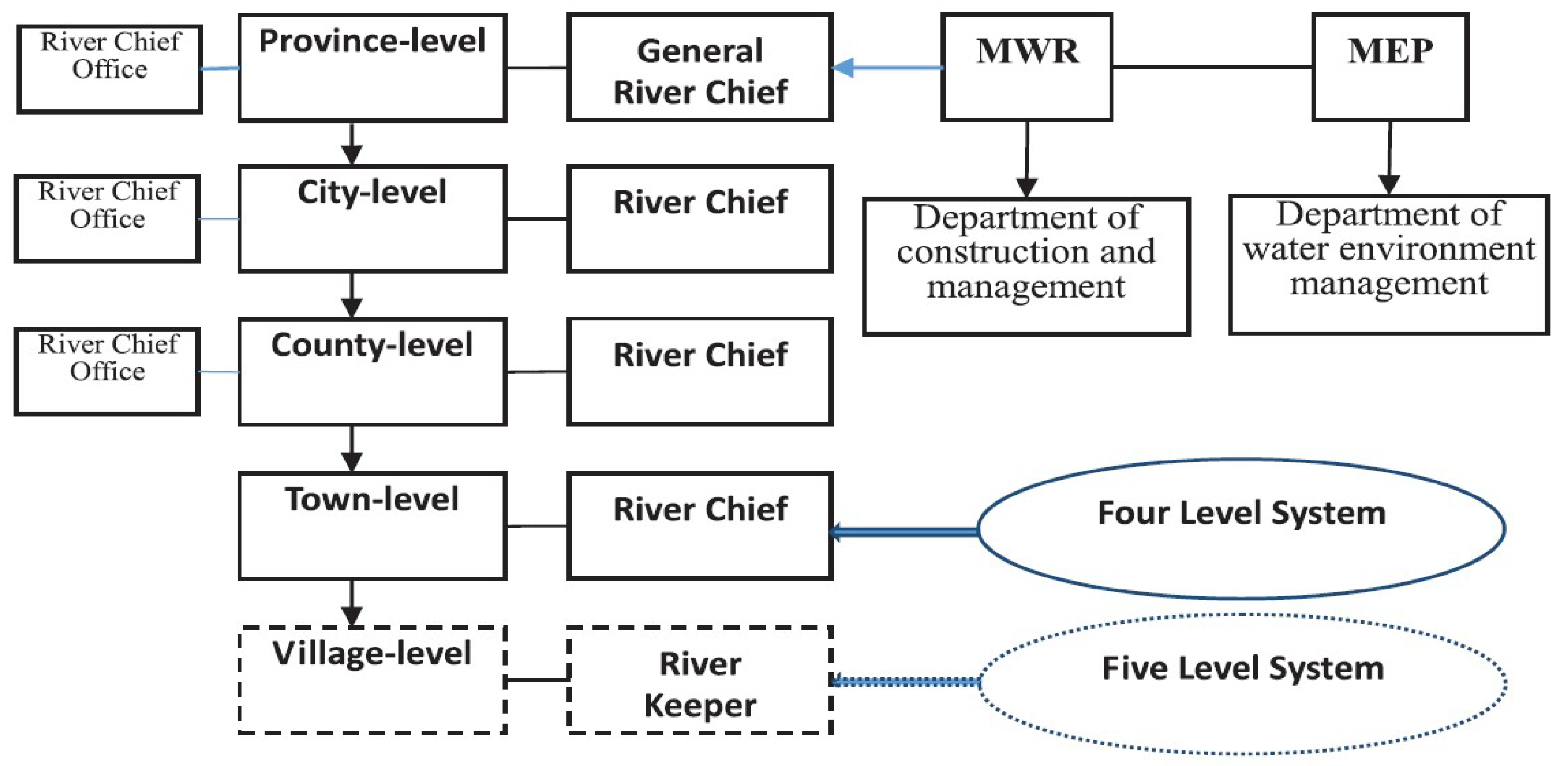

Figure 1).

Overall the spread of the river chief system took only a decade of gradual recognition and adaptation by local governments across mostly water rich cities and provinces in Eastern China before transferring up to the central government who subsequently transferred it back down to all local governments (currently involving all 5 tiers of government – provincial, city, county, town and village - in 29 provinces), who are still involved in experimenting and adapting the model that was designed based on the original Wuxi system, which was itself little more than an experiment designed to bring an emergency water quality situation under control.

While the models being utilised across the country vary, all must incorporate a series of tasks and assessment measures. At a general level each chief (and their deputy), regardless of the level operating at, are responsible for the maintained and protection of the rivers and lakes in their region. More specifically they have been tasked with 1) the protection of water resource 2) prevention and control of pollution entering the water way 3) the restoration of the water 4) management of the shoreline 5) management of the ‘water environment’, and 6) the enforcement of water related laws.

5

In addition, river chiefs at the provincial level assume overall responsibility for managing and protecting rivers and lakes in their jurisdiction. This provision includes prefecture-level cities. Units located at the county level and above must establish river chief system offices and infrastructure. These offices should themselves be designed to incorporate representatives from all the relevant departments and units involved in water management. The idea being to bring in the coordination between these units that was lacking prior to the rollout of the river chief system. Or as noted by Xianqiang, ‘All relevant departments and units shall work as mandated and collaboratively achieve the targets of all aspects’ of water management in the jurisdiction’ (2020, 3). It is important to note that in this the river chief office is:

responsible for the coordination, supervision, guidance, inspection, and communication of work, rather than replacing existing water-related functional departments. Through the regional water resources management committee or the inter-departmental joint meeting system, river chiefs at all levels can solve transfer problems and responsibility, policy goals and conflicts, lack of communication, and service omission of the watershed environment between different administrative departments (finance, water, environmental protection, agriculture, forestry, etc.), thereby reducing the obstacles from the fragmentation of bureaucratic management. (Wang, Wan, Zhu 2021, 3)

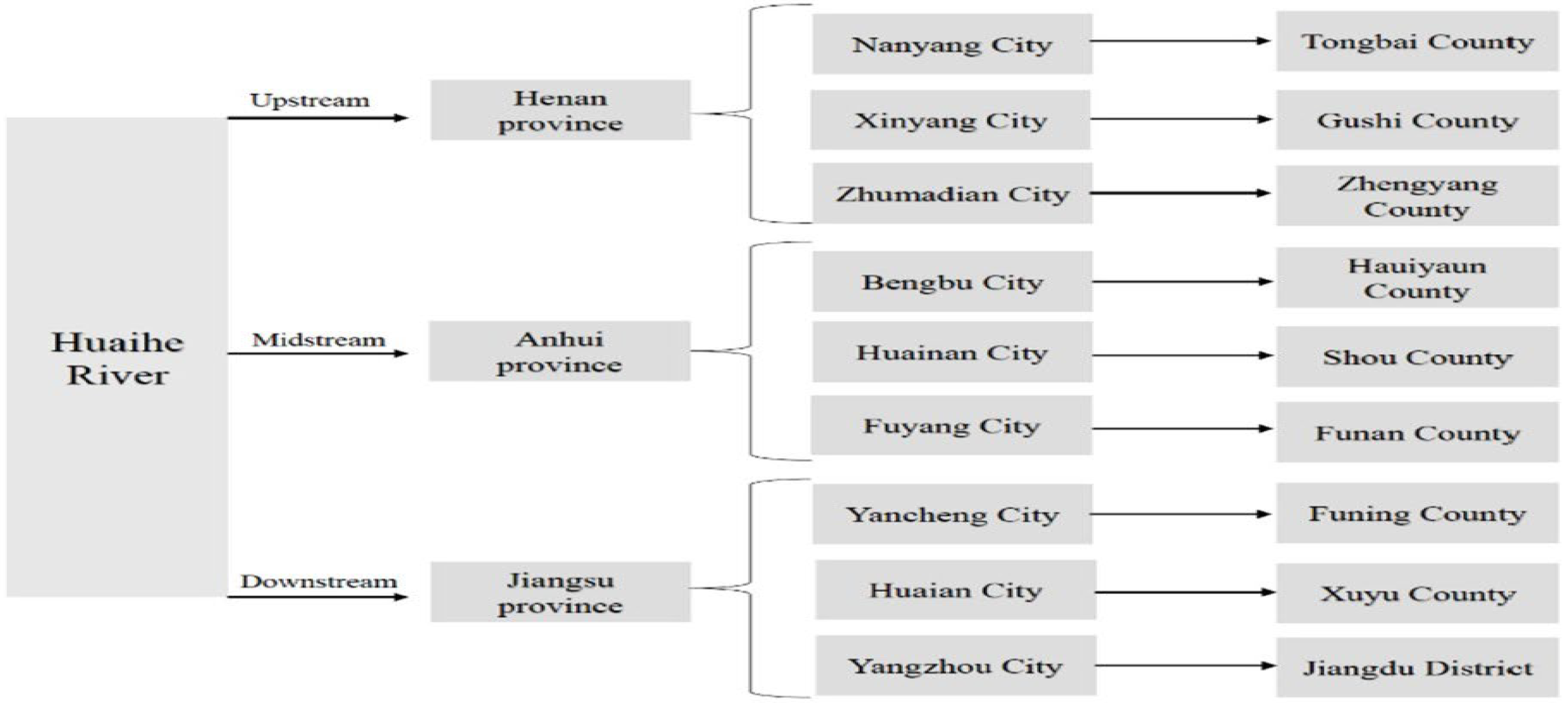

While the office of river chief systems helped to bring horizontal coordination to the water management system by bringing together the key departments and people responsible for the environmental management that impacted on the health of rivers in their jurisdiction, these offices only indirectly addressed problems of cross-jurisdictional coordination. These issues range from different jurisdictions being responsible for left versus right banks of rivers and lakes; issues that emerge from different jurisdictions being responsible for upper, middle and downstream sections of a single river (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) that often left the lowest section of the rivers having to take responsibility for activities occurring upstream despite having little to no power over these process, industries, or decisions.

To start addressing some of these issues, given that most rivers (river basins) and lakes in China transverse town, county, city and often provincial, boundaries (

Figure 4) the legislation mandated that for ‘large’ rivers and lakes spanning several jurisdictions (i.e., crossed regional boundaries), river chiefs will be held responsible for developing ‘mechanism for cooperation’ in the effective management along the entire river. More specifically the legislation mandates that river chiefs are responsible for the coordination of ‘joint prevention and control’ measures where pollution and ecosystem restoration impact on the upper and lower parts of a river or lake (and where it impacts on the left and right banks) in a river basin. To do this, some jurisdictions developed what has become known as the ‘conference system’, where the different jurisdictions associated with a river basin engage in direct consultations with their counterparts (though few involve cross basin management).

The core of the conference system is that it allows ‘river chiefs and departmental leaders at different levels, and from different regions, to consult on cross-jurisdictional and large-scale issues’ (Li, Tong, Wang 2020, 2).

In addition to the formal conference system jurisdictions are developing cross-jurisdictional agreements to improve the overall health of the river basin they are part of. For instance, it has been reported that Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou an Agreement on the Coordination of Chishui River Basin Environmental Protection’. The goal of the agreement has been to ‘jointly promote the ecological environment protection of the Chishui River Basin and strengthen the management of cross provincial waters.

Similar agreements for joint enforcement of violation of environmental standards has occurred among the provinces of Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan. Even city level river chief system offices are starting to engage in cross-jurisdictional agreements. For example, Luzhou, Zunyi, and Bijie signed the Agreement on the Coordination Working Mechanism of Fishery Administration in Co-managed water within Chishui River. This agreement has set the stage for a ‘coordination working mode, information reporting, enforcement, collaboration, action cooperation, mutual enforcement recognition’ across the city boundaries (Xianqiang 2021, 10).

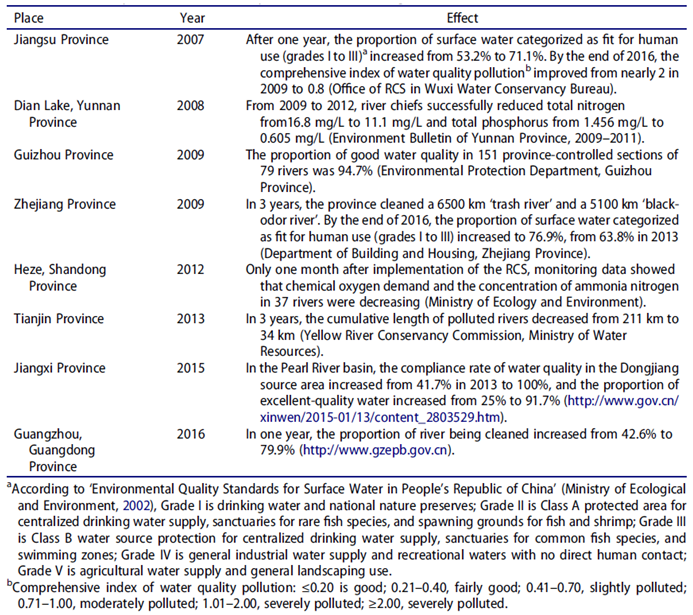

All told while there are clear variations in the impact of the river chief system across the country – particularly between Eastern Provence’s and Western Provence’s overall, as

Table 3 illustrates, it appears that the river chief system is making a difference in the quality of the water ecosystem across China. In fact, one of the most recent analyses of the effects of the river chief system in the Yellow River Basin concludes that ‘the implementation of the river chief system has played a significant positive role in improving the water environment quality of the Yellow River basin...[it] has achieved remarkable results in the short term’ (Zhang et al. 2023, 4412).

While antidotally Erik Solheim, the former executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme reported:

I visited Pujiang County…saw the wonderful transformation of rural Zhejiang...Pollutants in the rivers dyed the water white, so they were called “milky rivers” due to pollutants. Now over 97 percent of the surface water in Zhejiang is of excellent quality. The West Lake in Hangzhou and other lakes have been restored to their former beauty. No wonder the ancient Chinese said that “above is heaven, on Earth is Suzhou and Hangzhou” (Solheim 2023a, 1).

As such, while there is a lot more work to be done before all of China’s rivers and lakes are rated between Category I and III, since the initial pilot program was introduced in Wuxi surface water quality across the nation has seen dramatic improvement and one where China is seen as being among the leading nations in addressing water pollution in the world.

Seven Lingering Issues

While the available evidence indicates that the river chief system has led to an improvement in the water ecosystem across China, there remain a range of issues that are likely to impact its long-term ability to improve on its existing improvements, particularly once deep-water pollutants are considered and the ability of poorer provinces and regions to address non-point pollutants make their way up the agenda (Wang and Chen 2019).

First, the way the system has been structured makes success heavily dependent on the individual selected as river chiefs as it is apparent that the way policies are implemented at the local level tends to depend on not just on the ability of those chosen to act as river chiefs, but also the attitudes of those responsible for the implementation of the policies associated with the system. In brief, if career/party advancement pressures (such as salary or promotion) are not a motivating factor then it is hard to be sure that a river chief will be interested in the achievement of higher-level targets. Take age as an example of a potential obstacle to improvement, one local official (acting as a river chief) was reported to have said: ‘too old for promotion, too young to stop working, but just right for mahjong and drinking’ (Dai 2019, 77). Similar studies by Jin and Shen (2019) found that younger officials are still motivated by and prioritise GDP growth over environmental issues while older officials tend to be more motivated by the river chief assessment procedures.

Second, the veto system that has been integrated into the river chief assessment and evaluation systems are just one of many different potential vetoes’ that local officials face when engaged in the governing process. As such, while a local river chief might be motivated by water targets and pressures, they might be more motived by other ‘higher rated targets’, such as economic growth or meeting local health requirements.

Related to this, it has been reported that under some circumstance’s local officials have been motivated to manipulate information to make a situation look better than it is, particularly when the data is altered to ‘meet’ a target or be seen as doing better than required (see Dai 2015). Overall, because the system of accountability occurs within the party-state hierarchy where a higher-up governing official is responsible for the assessment, lower-level individuals might have an incentive to engage both rent-seeking behaviours and, in the extreme, corrupt practices (Wang and Chen 2019, 624).

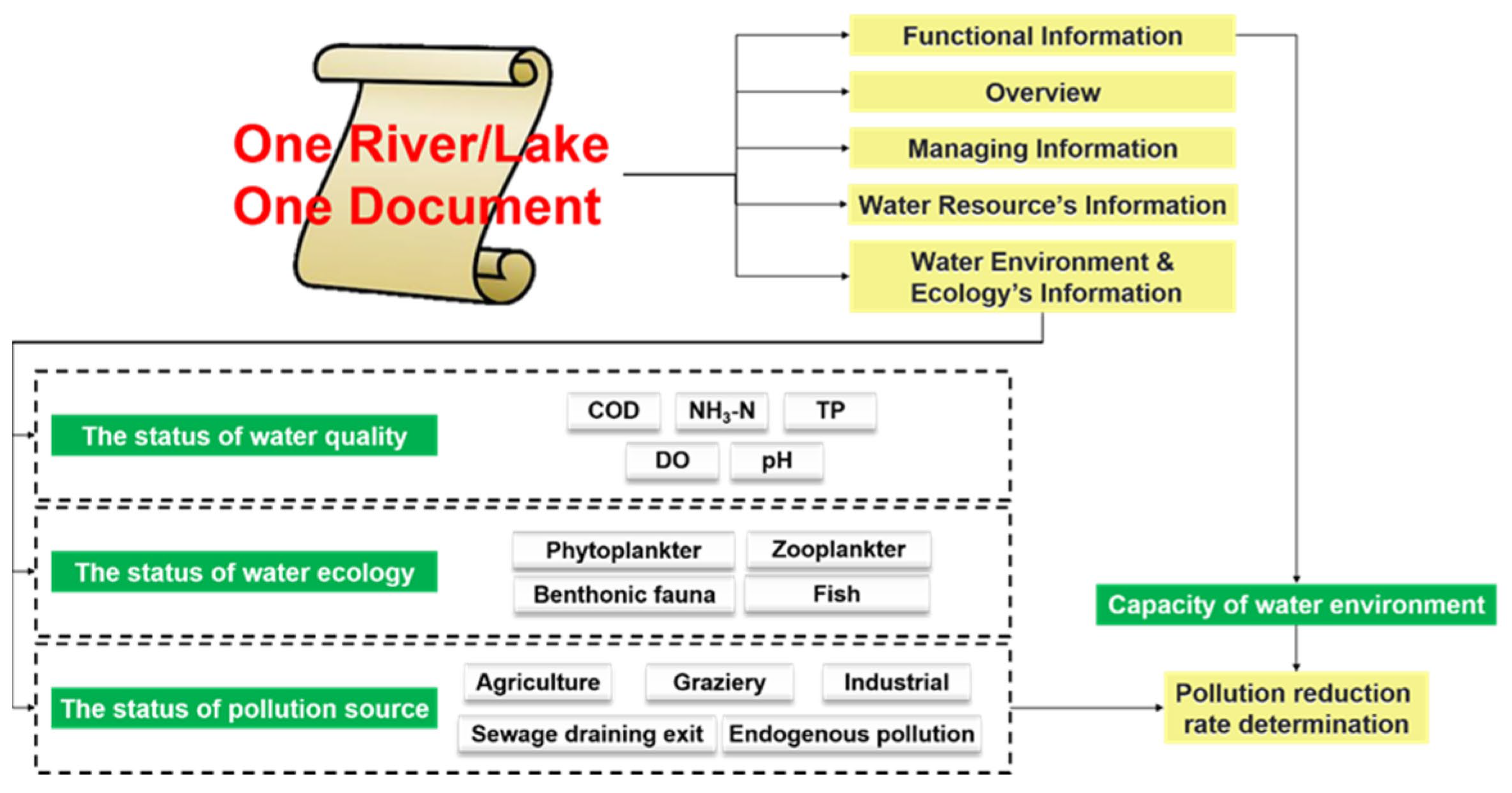

Further linked to the formal assessment process, is the fact that how performance and accountability are measured within the evaluation process tends to favour short-term quantifiable measures (such as the reduction of phosphorus and retaining a good PH balance) are favoured over less quantifiable long-term goals; such as, longer term water ecology renewal or sustainable (rather than simply eco-development which has much narrower target and performance measures) development goals (see Chien and Dong 2018). See

Figure 5 for a list of the types of pollutants and sources of these pollutants that are involved in the evaluation of river/lake health.

Third, to date, while some river chefs have started to coordinate across provinces and river basins (the conference system) this is still not well developed across the country. This leaves open issues where lack of upstream–downstream and left–right banks coordination results in different policies and procedures across a single river basin and in the right circumstance led to ‘dead zones in rivers/lakes protection’ where no authority is properly held responsible. Similarly, due to the weak nature (or complete lack) of cross province coordination it is often the case that activities upstream negatively impact the quality of water downstream (or in downstream lakes) and in ways that downstream jurisdictions are held responsible for factors beyond their control. For example, in the Chishui River Basin it was discovered that while ‘some provinces banned river sand mining and cage aquaculture others did not’ and that this led to unsolvable river pollution appearing in downstream rivers and lakes and negative economic impacts for those who did ban the practices (Xianqiang 2021; 11).

Fourth, while improvements have been made in the quality of surface water (particularly in Western Provinces), shortcomings in the monitoring and evaluation processes, deep water and ‘riverbed’ pollution tends to be neglected by river chiefs, particularly as they are not included in the overall assessment process. While this is partially a result that ‘each river has its own difficulties in water quality improvement’ and thus ‘finding a completely fair method to evaluate the performance of river chiefs is difficult’ (Liu, Chen, Liu, and Lin 2019; 11), it is possible that indicators will show surface water quality improvements but that these might not be long-term or built upon over time as the source of river pollution sinks to the bottom (i.e., measures have been designed to address the symptoms of river pollution rather than the underlying causes).

Fifth, despite the passage of the revised

Environmental Protection law of the Peoples Republic of China in 2014 (

Environmental Protection Law of People’s Republic of China, https://english.mee.gov.cn/), stipulating that the public should have an active role in environmental protection, since the launch of the river chief system across the country outside a few exceptions, the public are still not well utilised in the monitoring or feedback mechanism associated with the river chief or their evaluations. While the law provides the public the right to participate, know about, supervise, and litigate issues associated with water pollution and management including impact assessment, few Provinces have gone very far down the path of encouraging the public to participate in more than monitoring and reporting exercises, even where they have encouraged the development of different types of ‘river chiefs’ and watchers (see: Wu, Ju, Wang, Gu and Jiang 2020). This is a problem not only in terms of the law but also once one realises that the river chief system includes water bodies as small as canals, streams, and even canals, it becomes quite cumbersome for even village level river chiefs to fulfil all their duties without the help of the public.

Sixth, there is a clear distinction in the improvements being seen between provinces that will be difficult to overcome. The Western and Northwestern Provinces and autonomous regions are not finding the success that those in the Eastern and Southeastern Provinces are. Part of this is associated with the fact that these tend to be the poorer provinces and cities, and as such, do not have the technological capacity of their wealthier neighbours for the monitoring and cleaning of rivers and lakes. Part is that the administrative skills and abilities of the individuals selected as local leaders tends to be lower than those in better performing provinces and cities (though this might be partially addressed in the long-term by the Between Region Paring Assistance (BRPA) and the Inter-Regional Cadre Transfer system (IRCT). However, even with the two aforementioned efforts to help poorly performing provinces and regions, combined these difficulties will need to be addressed if China is going to successfully address long-term river and lake pollution across the nation.

Finally, it will be difficult to establish the motivation for engaging in the transfer and development process of the river chief system across China, which might impact its transferability and the differences in success that are being seen across jurisdictions in Chian. In brief, while it is possible to interview key individuals and stakeholders involved in the movement of the river chief, due to the nature of the party-state, and the way it is imbedded into the policymaking processes at all levels of government it hinders the ability of researchers to fully understand how policies move (though not when or where). Thus, while interviews have indicated that the primary motivation for the transfer of the river chief system into Huzhou was to become the local and national model (interview 17 October 2019), it was unclear why the official wanted this. Was it due to the desire for party advancement, better performance reviews, or for promotion from the city level government to provincial level government? Any one of these might have altered what was transferred and how the system was subsequently developed to fit the ‘needs’ of Huzhou, and how it has ultimately sbeen implemented.

Can the River Chief System Move Out of China?

Given the early success that China has experienced with the spread and national implementation of the river chief system, the question that must be asked is if it can be moved out of China. The answer to this depends on what one looks at. At the base level ideas can and do travel. As such, the ideas underpinning the river chief system can be moved to other locations. More specifically, idea that there is a link between a population’s health and the maintenance of its water supply is something that many governments can utilise when prioritising water clean-up and ecology. Similarly, the link between water ecology and health issues is movable to almost all jurisdictions. For example, in the United States there is growing awareness of the need to utilise green infrastructure and natural water ecology in the management of stormwater (Dolowitz 2022). It would be a short step to link this issue to the ideas of better overall water ecology. Similarly, the idea of being able to hold someone accountable for the condition of local lakes and rivers should be movable, even if it would need to be tailored to meet the different political structures associated with the locality.

Another idea that is embedded into the river chief system is the awareness of increasing public participation in the monitoring process. The idea of encouraging and finding ways to better integrate the public to help monitor and report on the visible (and if appropriate chemical) state of rivers and lakes is transferrable. In fact, we can see just such an approach being utilised in a small way by the Rivers Trust which runs a bi-annual ‘Big River Watch’ project designed to get the public involved in monitor the state of the rivers in the UK and Ireland over a five day period (see:

https://theriverstrust.org/take-action/the-big-river-watch).

While not an idea, one area where the river chief system is likely to offer a ‘best practice’ model is in the adaption and adaptation of technology in the monitoring of rivers by both officials and public participants in the system. This was seen internally when researchers found that:

based on the panel data of 108 prefecture-level cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) from 2004 to 2019. The results of this research show that: (1) GTI in the YREB shows a rapid growth trend, and the lower reaches are generally higher than the middle and upper reaches; (2) RCS can improve the local GTI by 19.43% and has a significant positive incentive effect on adjacent regions’ GTI, while the GTI itself can generate a positive spillover effect for adjacent regions…(Ding and Sun 2023)

This movement of monitoring technology is considerably easier than some of the other aspects of the system to be discussed below, especially when it comes to lower-level river chiefs and other involved in the monitoring process, due to the very nature of technology being ‘universally’ available on the ground. In fact, while not necessarily a result of policy transfer (as no data has been collected on this to date), subsequently to its use in areas of the Yangtze river basin, as part of the Big River Watch, a phone application has been utilised to facilitate the publics participation in the monitoring exercise (see: The River Trust:

https://theriverstrust.org/take-action/the-big-river-watch).

In addition to the use of the phone app, as in many of the river chief systems, the Big River Watch also utilises social media to both deliver information and collect it from the public. All told, as technology spreads and makes the monitoring of rivers easier and more interactive, it is likely that Chinese experiences will not only have a lot to teach the rest of the world but are likely to transfer too.

However, once we move outside of the arena of the ideas and technologies underpinning the river chief system, it becomes more difficult to see it being moved as a ‘model’ to other nations. First, it is not just about the ecology of rivers and lakes. Rather, it is an institutional solution to an institutionally created situation that is (in many ways) unique to the Chinese party-state. In most nations local leaders are elected and thus, directly accountable to the people. However, in China, where local leaders at the Provincial, City, County and Township levels are appointed, the principle-agent chain becomes considerably more complex. This is doubly true when it is realised that as a part-state many of the municipal positions are not only held by individuals selected to govern but are simultaneously held by either corresponding party officials or party officials who are in the government position.

Similarly, the river chief system, operating in part as an ‘internal’ monitoring and reward/punishment system is open to more manipulation than many nations would find acceptable if they could operate the bureaucratic processes in such a fashion. This is a result of most ‘democratic’ nations operating a tight division between party politics and a highly developed merit/exam based civil service hiring and promotion system ‘designed to ensure fair and open recruitment and competition and employment practices free of political influence or other nonmerit factors’ (US Office of Personal Management,

https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/performance-management/reference-materials/more-topics/merit-system-principles-and-performance-management). As such, the core mechanism of the river chief system is not about river management but rather a way the bureaucratic structures in China operate in a range of areas that is highly unlikely to work outside of Chian.

Conclusion

What started as a solution to an emergency arising out of a blue green algae bloom impacting the drinking water of Wuxi has grown to be a national policy. In this, policy learning and transfer were involved at all levels (for more see Dolowitz and Marsh 2000; Dolowitz 2017). First horizontally between cities both within and outside of Jiangsu Province, and then vertically to a number of different Provinces. From here the transfer and learning processes were a mix of horizontal and vertical transfers (both up to and down from higher level jurisdictions) and involved elements of both soft and hard learning. At this point the river chief system was adopted as party-state policy and sent down from Beijing to the provinces for implementation.

Early results, as the national policy is just over seven years old, seem to indicate that the river chief system is making a difference in the quality of surface water. More importantly, it is also clear that as the system has embedded new forms of local participation in the nations water monitoring systems. This has led to some villages and towns actively including citizens in the monitoring and reporting processes and corporations and schools into river adoption processes. All told, while the institutional situation that underpins the Chinese river chief system is unique to China, the overall experience, and techniques utilised by river chiefs are likely to have a great deal of potential to help other nations address their water ecology situations.

A good example of this could be the adaptation of the technology that underpins much of the water quality evaluations seen in river chief monitoring processes of the leading western provinces. This technological approach might be ‘exported’ to inform the UKs recent announcement regarding the Natural Capital and Ecosystem Assessment Program, which according to the UKRI is designed to investigate and integrate natural capital approaches into the governing processes of the marine environment (UKRI 2024). Making this movement possible can be seen in statements such as that made by Lord Benyon (Minister of State for Climate, Environment and Energy) when he noted that ‘It is more important than ever that we invest in advanced technology such as artificial intelligence, drones and molecular tools to bolster our capabilities to monitor biodiversity in our seas’ (UKRI 2024), all of which have been used in the application of the river chief system in Chian.

In a similar fashion, as a result of a Supreme Court decision in Sakett v. EPA, which substantially reduced EPA protections for streams that only flow during ‘rainy seasons’ or as a result of snow melt, there is a growing concern about the state of ‘about half of the nation’s [USA] wetlands and up to four million miles of streams that supply drinking water for up to four million people’ (Jacobo 2024). Clearly, while the situation is different, the experience of the more arid regions in Northern and Western China in implementing and operating river chief systems under similarly arid conditions might offer valuable lessons for many of the streams and wetlands impacted by the Sackett decision.

While it is hard to see the overall river chief system being transferred outside of China, it is it is equally possible to see the underlying ideas and technologies being developed and used to improve the water environment, and the efforts seen in some provinces, cities, towns, and villages to increase citizen participation could be promoted and make their way onto the global stage. Not only are regions and nations facing similar issues with water quality and ecological degradation, but the combination of high technological solutions combined with low technological public participation clearly offer others with ideas and potential solutions to pollution contamination of rivers, lakes, and shoreline environments.

| 1 |

While not the focus of this article, it is worth noting that in addition to water pollution, many Western and Northern parts of China are facing greater water resource constraints due to the arid and semi-arid nature of these provinces. In response, the government has instituted large scale water transfer projects, involving moving water from South-to-North. This movement itself makes addressing the issue of polluted waters vitally important. |

| 2 |

Water bodies in China are divided into five classes. Class I is the purest and safest and is seen as suitable for human consumption and a source for nature reserves; Class II is considered safe for centralized drinking and in marine protected areas; Class III is appropriate to ‘second class’ protected areas and centralised drinking water; Class IV is for industrial use and is not considered safe for human contact or drinking; Class V water is only considered safe for agricultural purposes; class V+ indicates the water is not suitable for any purpose (for more information on water quality standards see: https://english.mee.gov.cn/SOE/soechina1997/water/standard.htm). |

| 3 |

Point source pollution is pollution entering the waterways from an easily identifiable source, such as a specific factory. Non-point source pollution is pollution that enters the waterways from a broad area and its source is not easily pinpointed such street runoff or agricultural pollutants. |

| 4 |

Some authors associate the start of the river chief system with Changxing County (Zhejhiang Province) who issued a ‘river chief’ document as early as 2003 and subsequently appointed a river chief in Shuikou Village in 2005 (Xianqiang 2021). |

| 5 |

Note: in China the Provincial Party Committee Secretary, as the formal representative of the party, is technically the top ranking official in a province with the Governor as the second ranking official, making the Party Committee Secretary the primary official responsible for the RCS in the Province. |

References

- Chien, S.; Dong, L.H. River leaders in China: Party-state hierarchy and transboundary governance. Political Geography 2018, 62, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L. A New Perspective on Water Governance in China: Captain of the River. Water International 2015, 40, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L. Implementing the Water Goals—The River Chief Mechanism in China. In: Politics and Governance in Water Pollution Prevention in China. Politics and Development of Contemporary China. Cheatham: Palgrave 2019, 69-82.

- Dolowitz, D.; Marsh, D. Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making. Governance 2020, 13, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolowitz, D. ‘Does Transfer Lead to Learning? The international movement if information’: CEBRAP Review. Novos Estudos 2017, 17, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, R.; Sun, F. Impact of River Chief System on Green Technology Innovation: Empirical Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnellon-May, G. (28 August 2023),’Water Warriors: How China’s River Chiefs Aim to Tackle Water Pollution’, Asia Society. Available online: https://asiasociety.org/australia/water-warriors-how-chinas-river-chiefs-aim-tackle-water-pollution (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Environmental Protection Law of People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://english.mee.gov.cn/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Global Water Partnership. China’s Water Resources Management Challenge: The ‘Three Red Lines’, Elanders: Sweden, 2015.

- Hao, Y. , and Wan, T. (2023), The River Chief System and An Ecological Initiative for Public Participation, Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Huan, Q. Regional Supervision Centres for Environmental Protection in China. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 2011, 40, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo, J. (2024), ‘Streams that supply drinking water in danger following 2023 Supreme Court decision that stripped wetlands Protections’, ABC News online (16 April). Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/US/streams-supply-drinking-water-danger-2023-supreme-court/story?id=109139758 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Jin, G.; Shen, K. Promotion Incentives for Local Officials and the Evolution of River Chief System: A Perspective Based on Officials’ Age. Finance and Trade Economics 2019, 4, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Tong, J.; Wang, L. Full Implementation of the River Chief System in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3754–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Lin, L. The River Chief System and River Pollution Control in China: A Case Study of Foshan. Water 2019, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Richards, K. The He-Zang (River Chief/Keeper) System: an innovation in China’s water governance and management. International Journal of River Basin Management 2019, 17, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jang, L.; Yuan, H. Is China’s River Chief Policy Effective? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 220, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, A. (2014). China’s Political System, Economic Reform, and the Governance of Water Quality in Pearl River. In D. E. Garrick, D. Connell, & J. Pittock (Eds.), Federal Rivers: Managing Water in Multi-layered Management Systems (384pp). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Solheim, E. (2023), ‘A watershed moment for China’s green leap’, Sri Lanka Guardian. Available online: http://www.srilankaguardian.org/2023/08/a-watershed-moment-for-chinas-green-leap.html (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Solheim, E. (2023a), ‘Guest Opinion: A watershed moment for China’s green leap’. Available online: http://www.china.org.cn/world/Off_the_Wire/2023-08/16/content_103215816.htm (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Tang, W.; Pei, Y.; Xheng HZhao, Y.; Shu, L.; Zhang, H. Twenty years of China’s water pollution control: Experiences and challenges. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai Hu Net. (2016). Modern River Chief Mechanism Expended to Nationwide from Here. Available online: http://www.tba.gov.cn/tba/content/TBA/xwzx/slyw/0000000000011409.html (accessed on 12 January 2018).

- The Rivers Trust (2024). Available online: https://theriverstrust.org/take-action/the-big-river-watch (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- UKRI (2024), ‘Funding to improve biodiversity observation capabilities in UK waters’. Available online: https://www.ukri.org/news/funding-to-improve-biodiversity-observation-capabilities-in-uk-waters/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- US Environmental Protection Agency (2017). Available online: https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/international-cooperation/epa-collaboration-china_.html (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- US Office of Personal Management (2024). Available online: https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/performance-management/reference-materials/more-topics/merit-system-principles-and-performance-management (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Wan, B.; Wan, J.; Zhu, Y. River Chief System: an institutional analysis to address water shed governance in China. Water Policy, 1435. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X. River Chief System as a Collaborative Water Governance Approach in China. International Journal of Water Resource Development 2020, 36, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water Law of the People’s Republic of China - 1988, Article 1. Available online: https://lehmanlaw.com/resource-centre/laws-and-regulations/environment/water-law-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china-1988.html (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Wu, C.; Ju, M.; Wang, L.; Gu, X.; Jiang, C. Public Participation of the River Chief System in China. Water 2020, 12, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianqiang, T. (2021), ‘The River Chief System in China’, In: Ferrier, R.C. and Jenkins, A. (eds). Handbook of Catchment Management.

- Xinhua, “Tougher law to curb water pollution,” China Daily, February 29, 2008. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2008-02/29/content_6494712.htm (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Zhang, Z.; Xiong, C.; Yang, Y.; Liang, C.; Jiang, S. ‘What Makes the River Chief System in China Viable? Examples from the Huaihe River Basin’. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, X.; Zhang, C.; Sharifi, S. ‘Has China’s River Chief System Improved the Quality of Water Environment? Take the Yellow River Basin as an Example’. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2023, 32, 4403–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).