Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Purpose of Study

3. Research Framework

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Participants

3.3. Developmental Advising and Its Assessment - A Qualitative Review

3.3.1. Developmental Advising

3.3.2. National Academic Advising Association and ABET Standards

3.3.3. Assessing Advising

4. Theoretical, Conceptual and Practical Frameworks

4.1. Theoretical Framework

4.1.1. OBE Model

- Developing a clear set of learning outcomes around which all of the educational system’s components can be focused; and

- b. Establishing the conditions and opportunities within the educational system that enable and encourage all students to achieve those essential outcomes.

- Ensuring that all students are equipped with the knowledge, competence, and qualities needed to be successful after they exit the educational system; and

- b. Structuring and operating schools so that those outcomes can be achieved and maximized for all students.

- All components of the education system including academic advising should be based on, achieve and maximize a clear and detailed set of learning outcomes for each student; and

- b. All students should be provided with detailed real time and historic records of their performances based on learning outcomes for making informed decisions for improvement actions.

4.2. Conceptual Framework

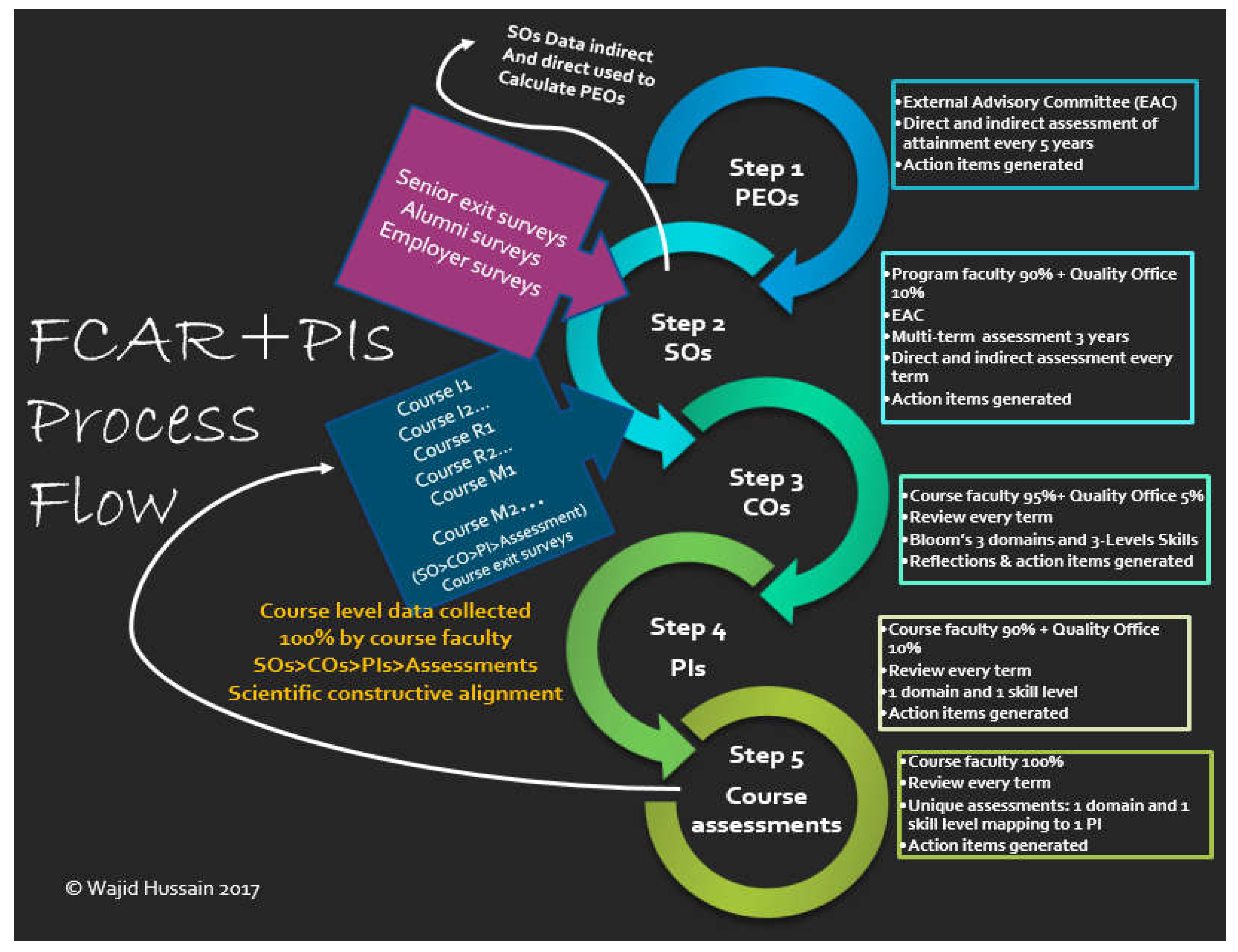

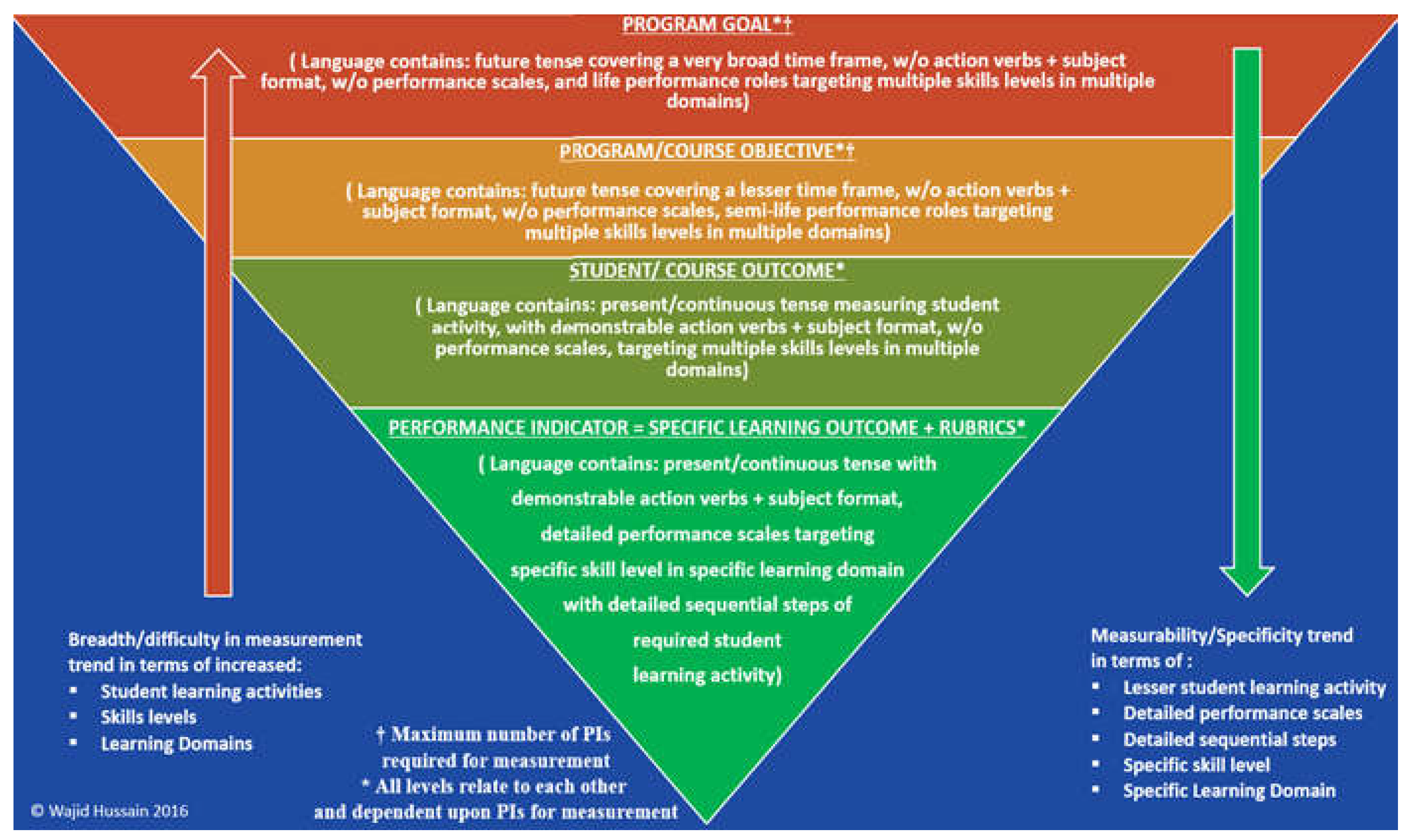

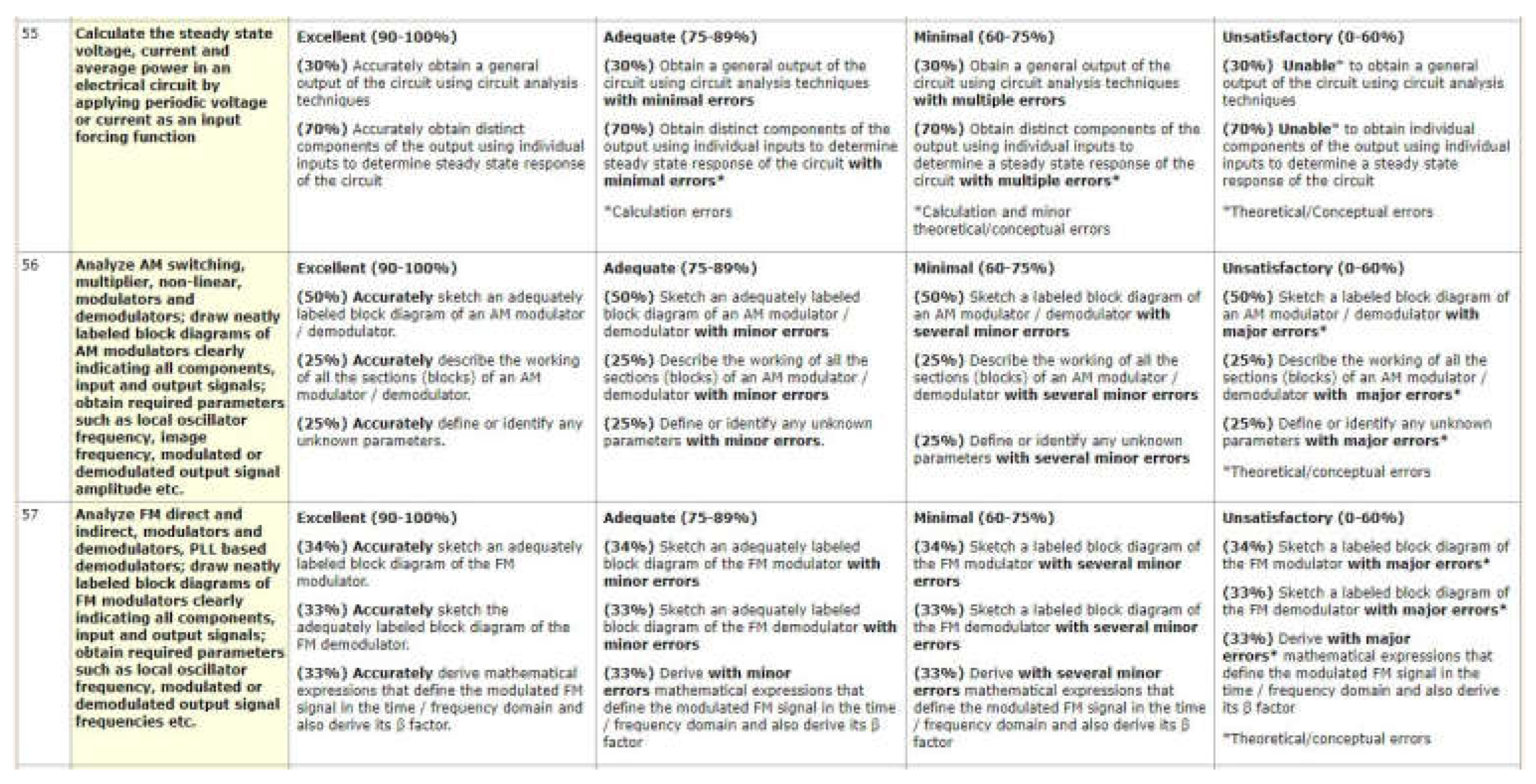

4.2.1. FCAR + Specific/Generic Performance Indicators Assessment Model

4.3. Practical Framework – Digital Platform EVALTOOLS ®

4.4. Practical Framework – Summary of Digital Technology and Assessment Methodology

- Measurement of outcomes information in all course levels of a program curriculum: introductory (100/200 level course), reinforced (300 level course) and mastery (400 level course). Engineering fundamentals and concepts are introduced in 100/200 level courses; then they are reinforced in 300 level courses through application and analysis problems; and finally in 400 level courses students attain mastery in skills with activity such as synthesis and evaluation [43,53,54,55].

- Well-defined performance criteria for course and program levels.

- Integration of direct, indirect, formative, and summative outcomes assessments for course and program evaluations.

- Program as well as student performance evaluations considering their respective measured ABET SOs and associated PIs as a relevant indicator scheme.

- 6 comprehensive Plan Do Check Act (PDCA) quality cycles to ensure quality standards, monitoring, and control of education process, instruction, assessment, evaluation, CQI, and data collection and reporting [47].

- Customized web-based software EvalTools® facilitating all of the above (Information on EvalTools®) [33].

5. Student Evaluations

- Level 1: Quantitative review of single or multi-term SOs data followed by a qualitative semantic analysis of language of SOs statements coupled with qualitative review of curriculum and course delivery information.

- Level 2: Quantitative review of single or multi-term SOs and PIs data followed by a qualitative semantic analysis of language of SOs and PIs statements, course titles and assessment types coupled with qualitative review of curriculum and course delivery information.

- Level 3: Quantitative review of single or multi-term SOs and PIs data followed by a qualitative semantic analysis of language of SOs and PIs statements, course titles and assessment types coupled with qualitative review of curriculum, course delivery and FCAR instructor reflections information.

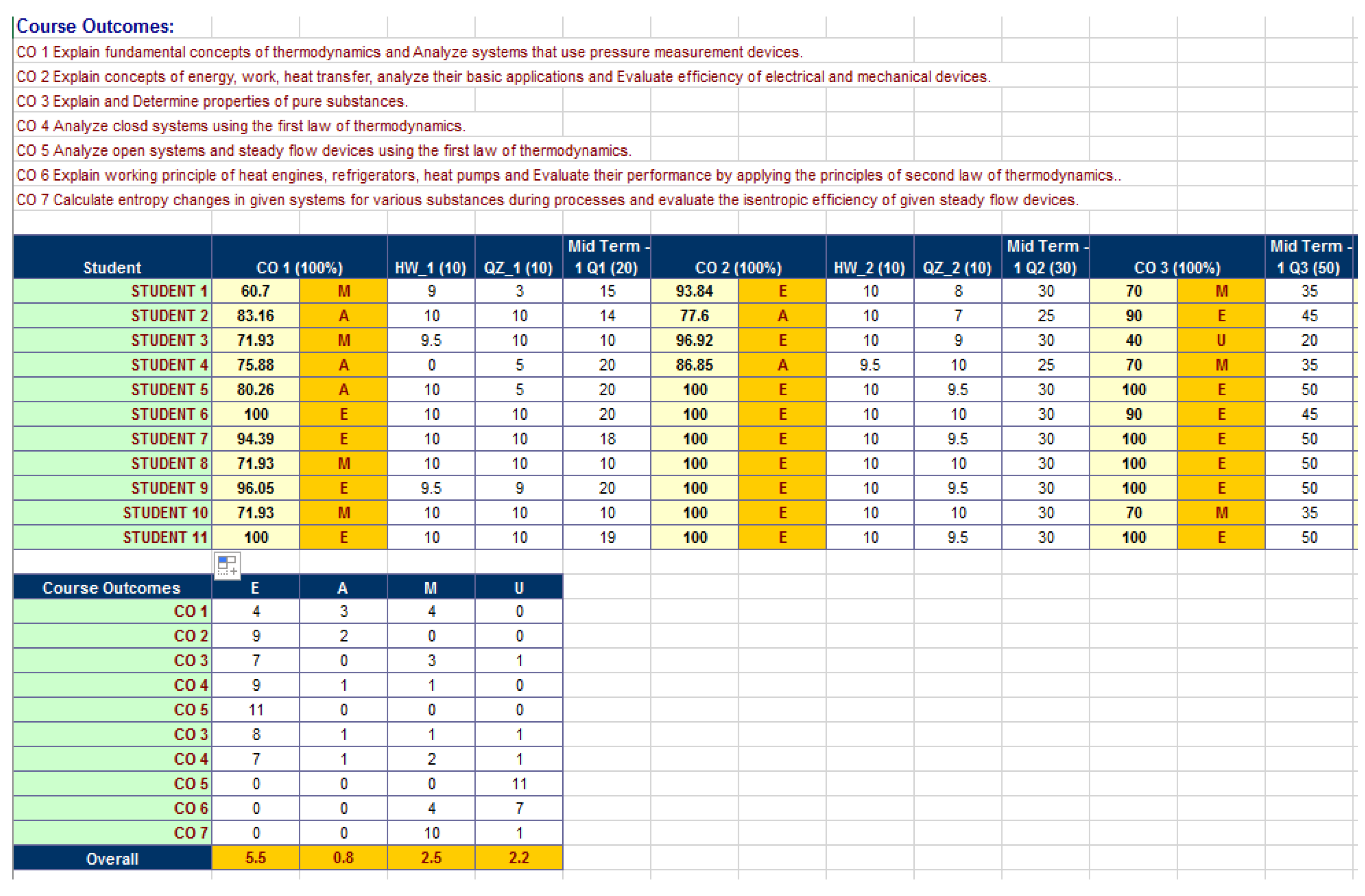

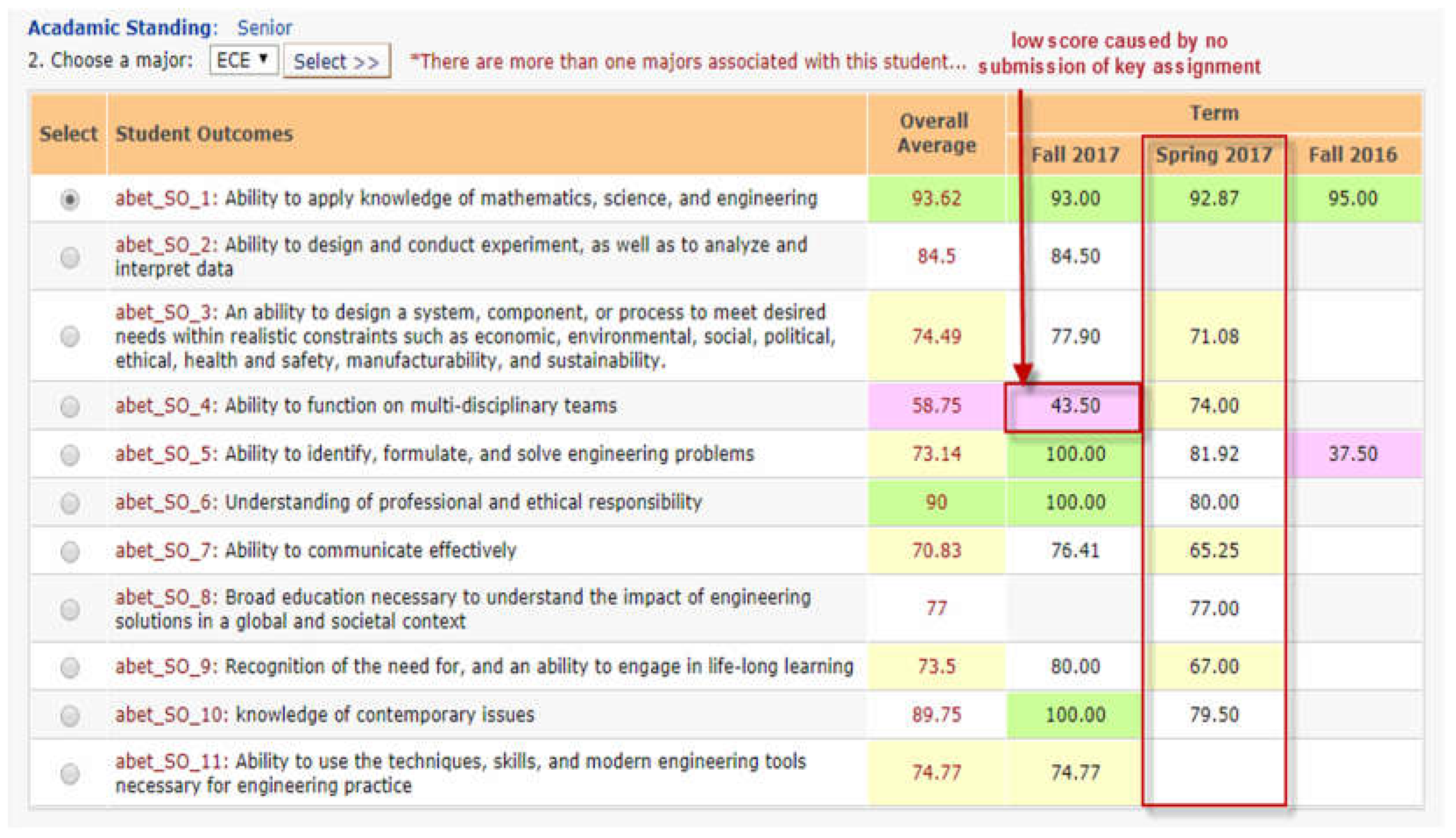

5.1. Automated ABET SOs Data for Every Enrolled Student

5.2. Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of Each Student’s ABET SOs Data

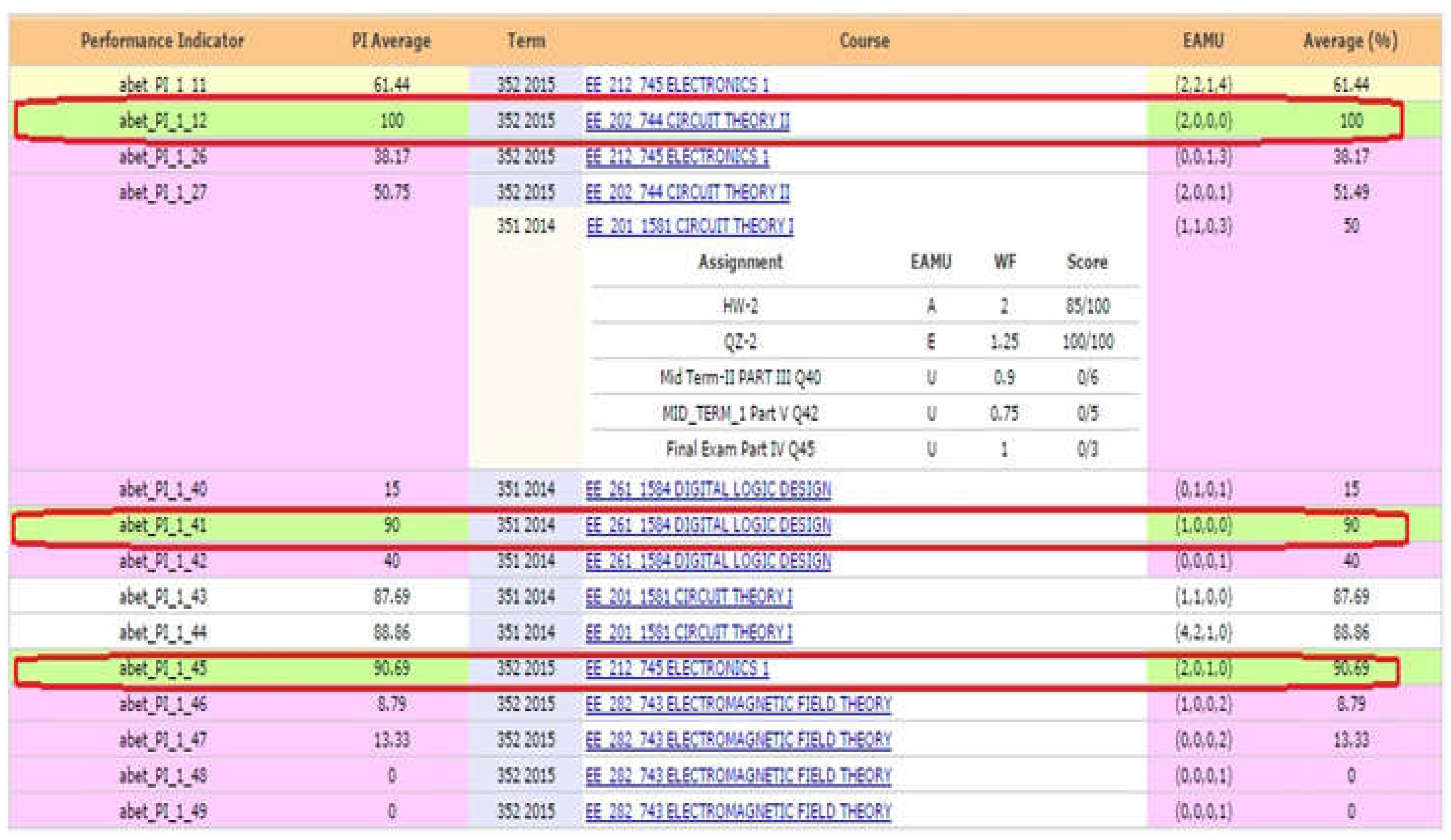

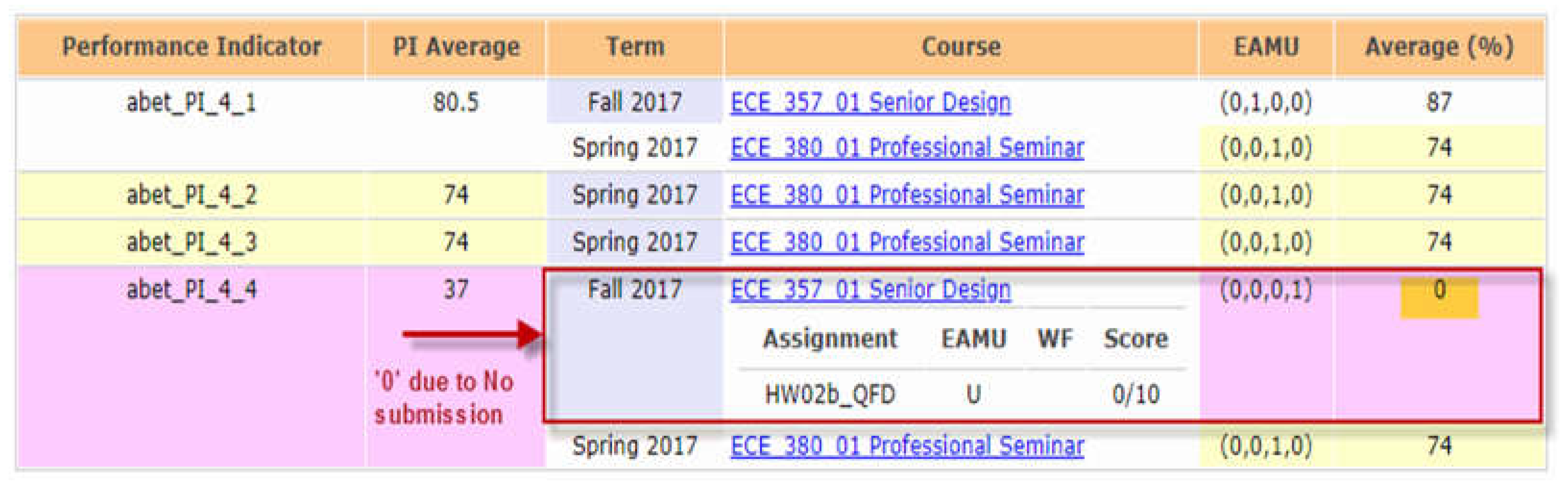

5.3. Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of Each Student’s PIs and Assessment Data

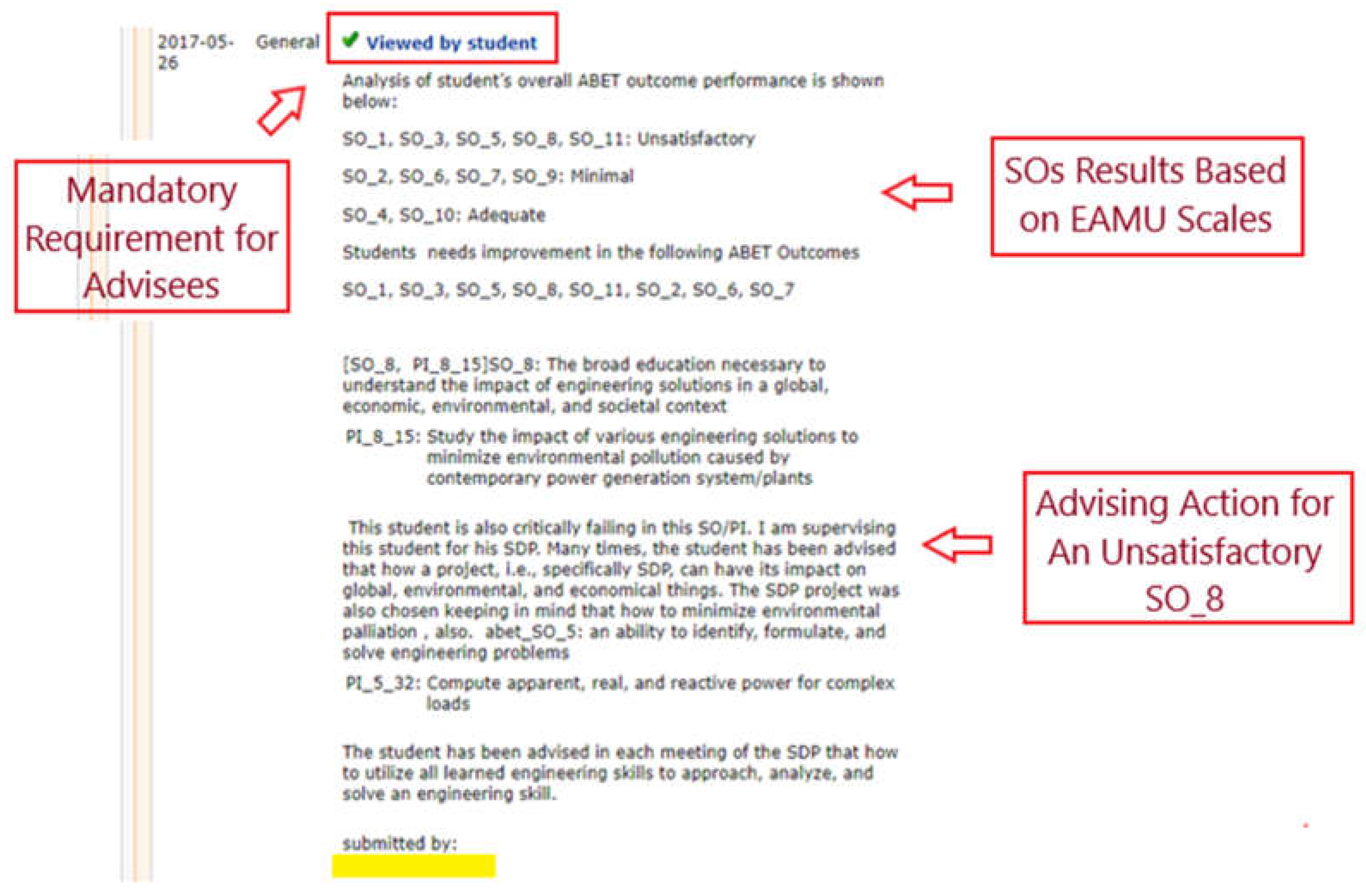

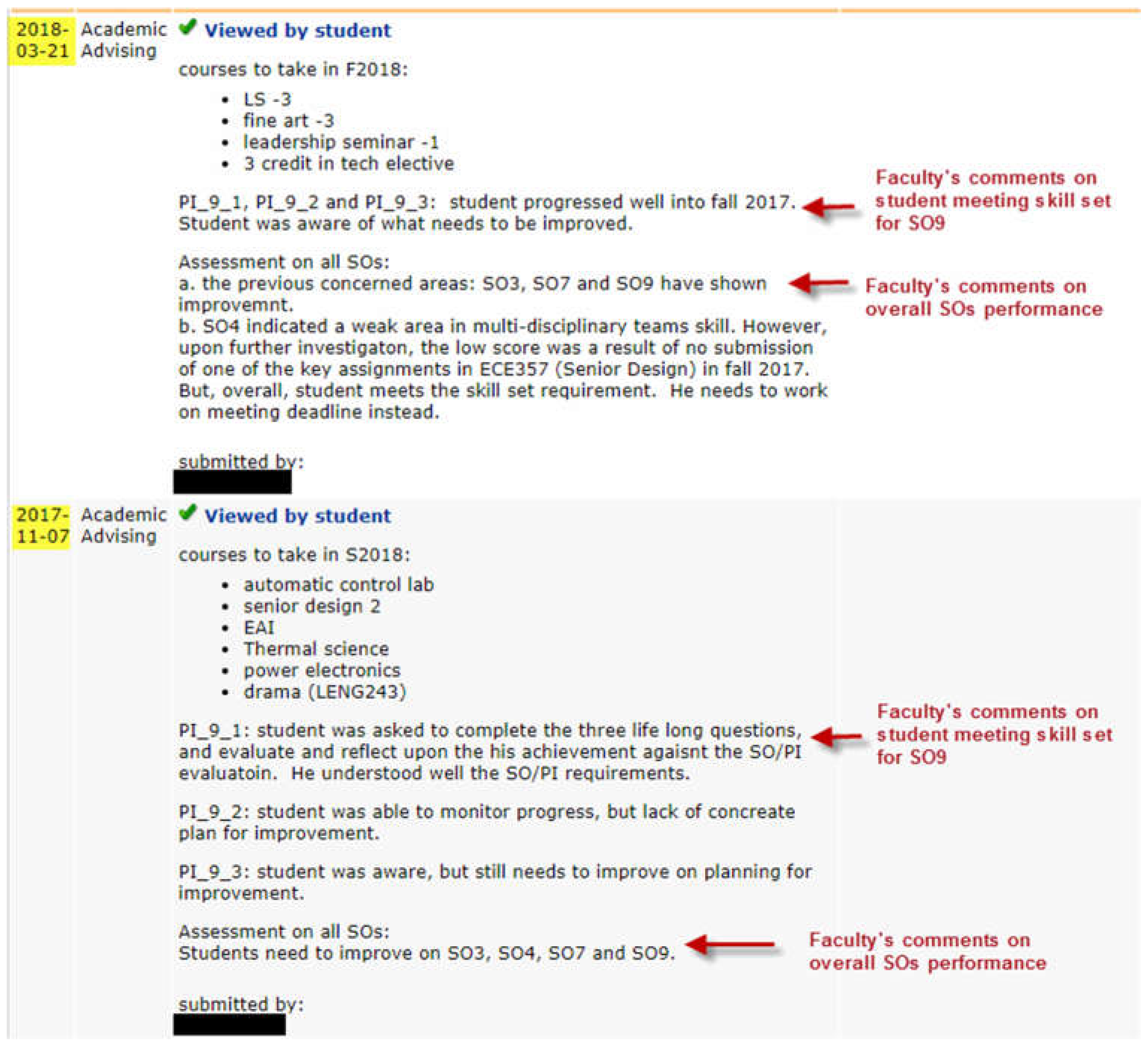

5.4. An Outcomes Based Advising Example

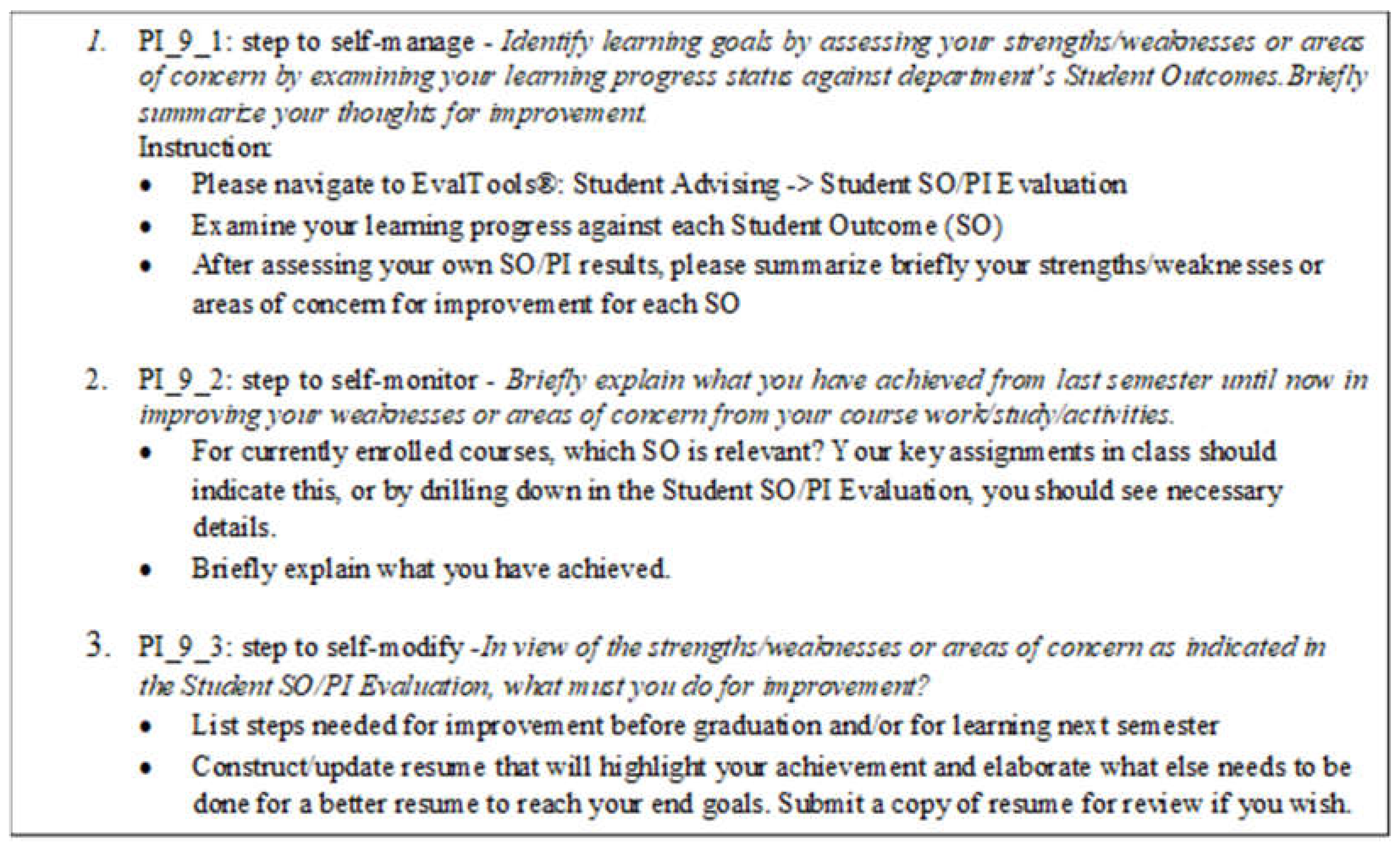

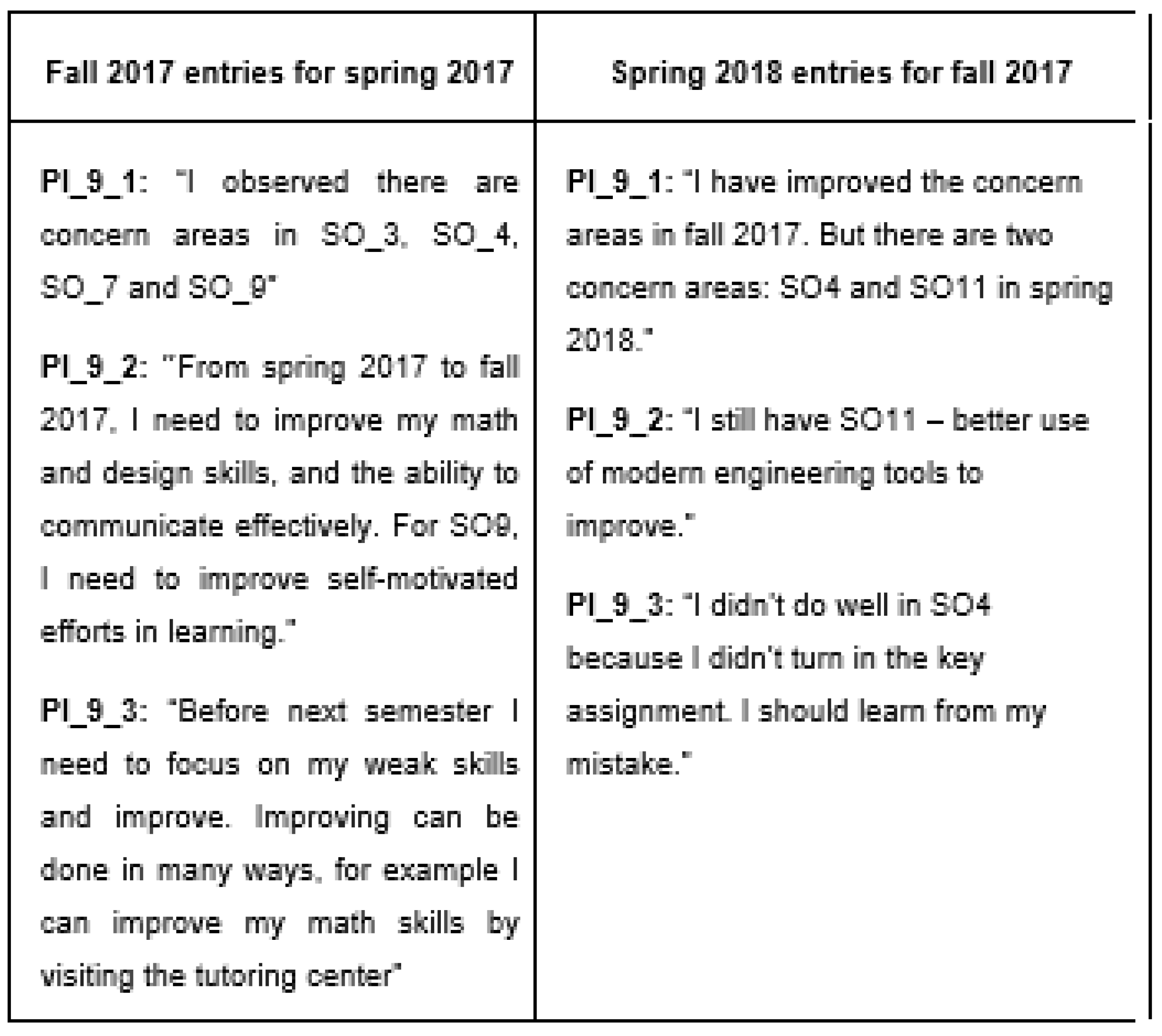

5.4. Students as Active Participants

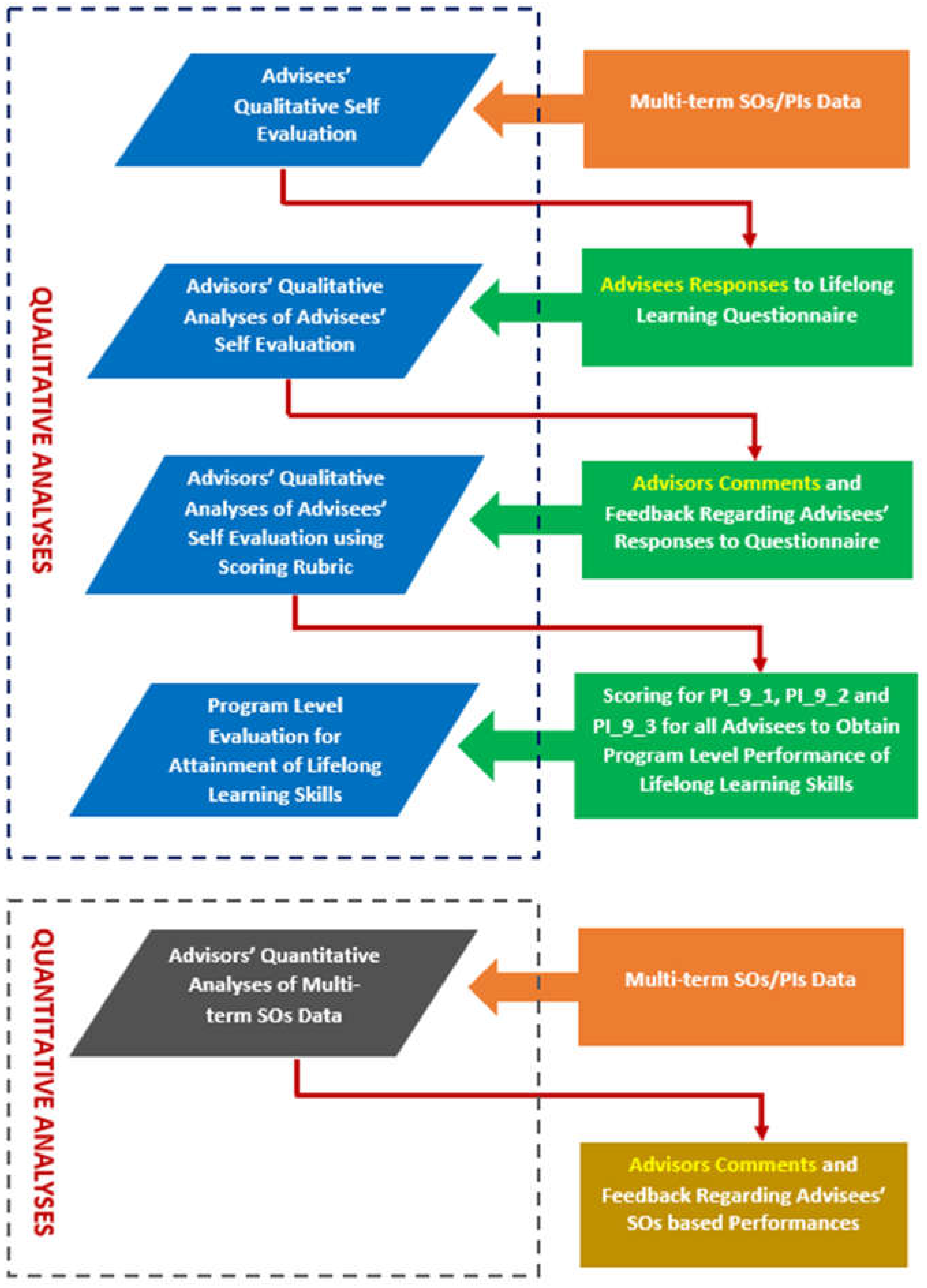

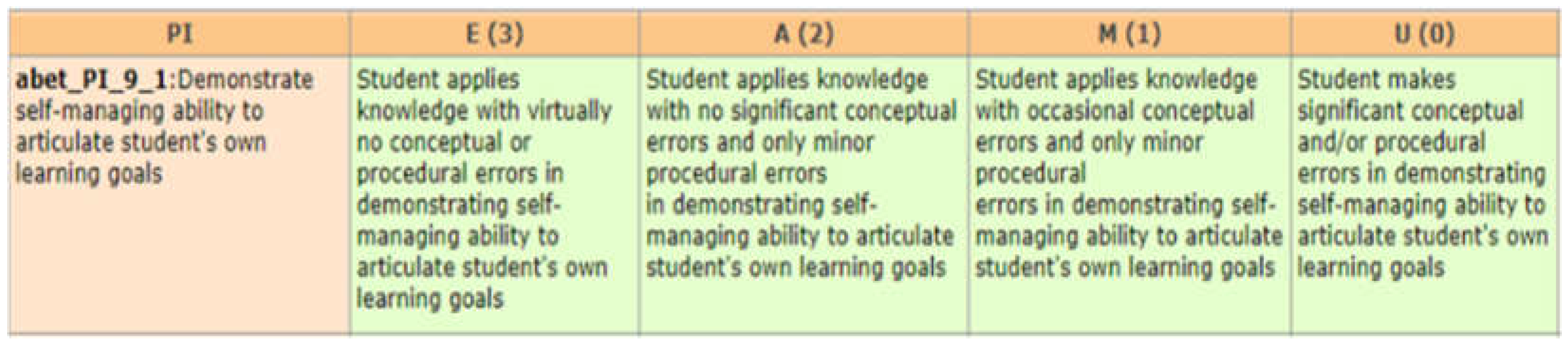

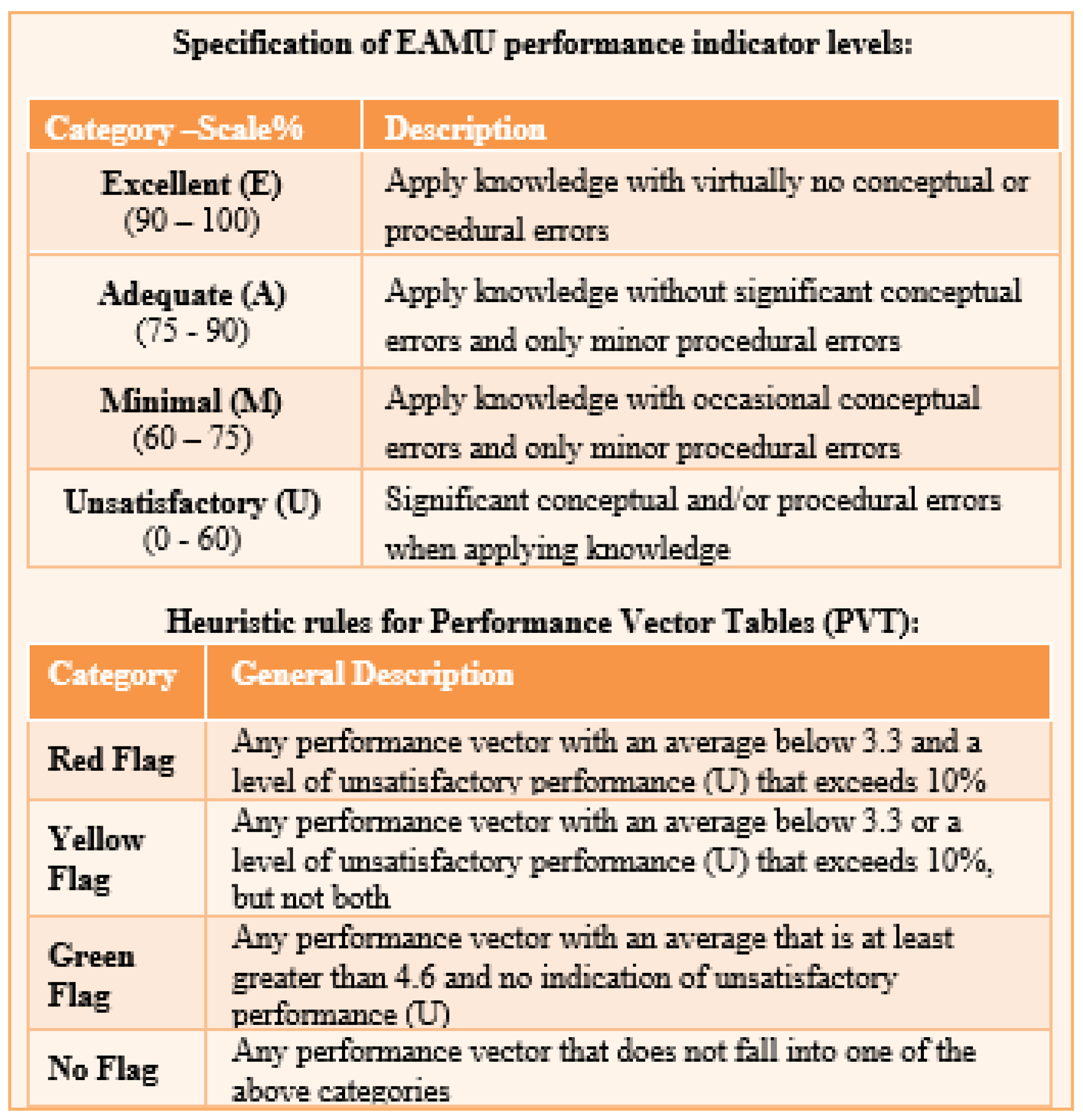

5.4.1. Process for Measuring Soft Skills in Student Advising Activities

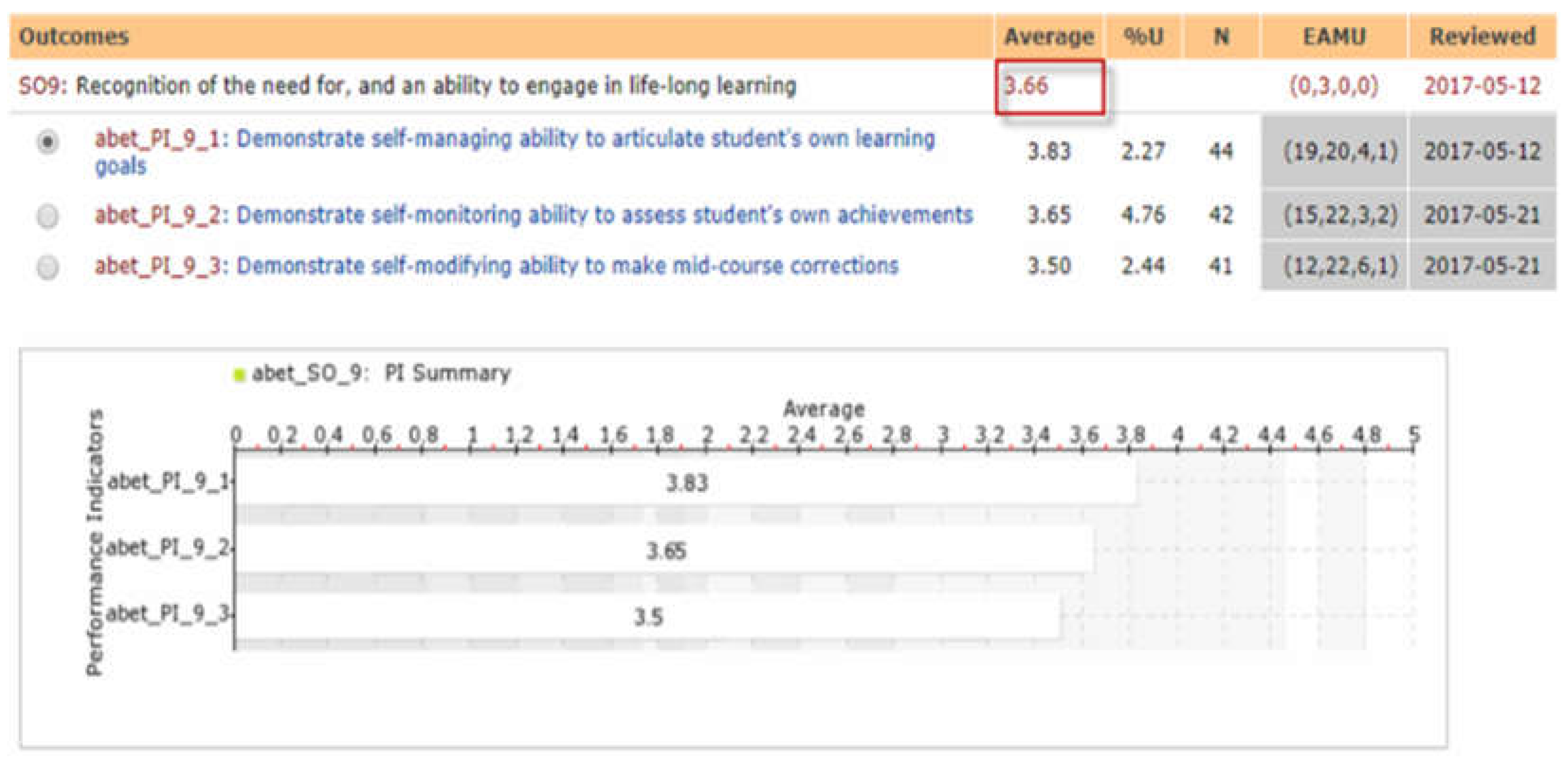

5.5. Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of Student Responses and Overall SOs Results

5.6. Added Advantage for Evaluating Advising at The Program Level

5.7. Quality Standards of Digital Developmental Advising Systems

5.8. Qualitative Comparison of Digital Developmental Advising with Prevalent Traditional Advising

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Question 1: To What Extent Should Engineering Programs Shift From Program to Student Centered Models That Incorporate Learning Outcomes for Evaluation of Individual Student Performances Besides Program Evaluations for Accreditation Requirements?

6.2. Research Question 2: To What Extent Can Manual Assessment Processes Collect, Store And Utilize Detailed Outcomes Data For Providing Effective Developmental Academic Advising To Every Student In An Engineering Campus Where Several Hundred Are Enrolled?

6.3. Research Question 3: To What Extent Can The Assessment Process be Automated Using Digital Technology so that Detailed Outcomes Information for Every Student on Campus Can be Effectively Utilized for Developmental Advising?

6.4. Research Question 3: What Specific Benefits Can Digital Automated Advising Systems Provide to Developmental Advisors and their Students?

7. Limitations

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Killen, R. (2007). Teaching strategies for outcome based education (second edn.). Cape Town, South Africa: Juta, & Co.

- Moon, J. (2000). Linking levels, learning outcomes and assessment criteria. Bologna Process.–European Higher Education Area. http://aic.lv/ace/ace_disk/Bologna/Bol_semin/Edinburgh/J_Moon_backgrP.

- Spady, W. (1994a). Choosing outcomes of significance. Educational Leadership, 51(5), 18–23.

- Spady, W. (1994b). Outcome-based education: Critical issues and answers. Arlington, VA: American Association of School Administrators.

- Spady, W. , Hussain, W., Largo, J., Uy, F. (2018, February) "Beyond Outcomes Accreditation," Rex Publishers, Manila, Philippines. https://www.rexestore.com/home/1880-beyond-outcomes-accredidationpaper-bound.html.

- Spady, W. (2020). Outcome-Based Education's Empowering Essence. Mason Works Press, Boulder, Colorado. http://williamspady.com/index.php/products/.

- Harden, R. M. (2002). Developments in outcome-based education. Medical Teacher, 24(2), 117–120. [CrossRef]

- Harden, R. M. (2007). Outcome-based education: The future is today. Medical Teacher, 29(7), 625–629. [CrossRef]

- Adelman, C. (2015). To imagine a verb: The language and syntax of learning outcomes statements. National Institute of Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA). http://learningoutcomesassessment.org/documents/Occasional_Paper_24.pdf.

- Provezis, S.

- Gannon-Slater, N. , Ikenberry, S., Jankowski, N., & Kuh, G. (2014). Institutional assessment practices across accreditation regions. Urbana, IL, National Institute of Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA). www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/documents/Accreditation%20report.pdf.

- Accreditation Board of Engineering & Technology (ABET), USA 2023, accreditation criteria, www.abet.org http://www.abet.org/accreditation/accreditation-criteria/.

- Dew, S. K. , Lavoie, M. In , & Snelgrove, A. (2011, June). An engineering accreditation management system. Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association. Paper presented at the 2nd Conference Canadian Engineering Education Association, Newfoundland, Canada., St. John’s. [CrossRef]

- Essa, E. , Dittrich, A., Dascalu, S., & Harris, F. C., Jr. (2010). ACAT: A web-based software tool to facilitate course assessment for ABET accreditation. Department of Computer Science and Engineering University of Nevada. http://www.cse.unr.edu/~fredh/papers/conf/092-aawbsttfcafaa/paper.pdf.

- Kalaani, Y. , Haddad, R. J. (2014). Continuous improvement in the assessment process of engineering programs. Proceedings of the 2014 ASEE South East Section Conference. 30 March. American Society for Engineering Education.

- International Engineerng Alliance (IEA), Washington Accord signatories (2023) https://www.ieagreements.org/accords/washington/signatories/.

- Middle States Commission of Higher Education (2023). Standards for accreditation, PA, USA. https://www.msche.org/.

- Mohammad, A. W. , & Zaharim, A. (2012). Programme outcomes assessment models in engineering faculties. Asian Social Science, 8(16). [CrossRef]

- Wergin, J. F. (2005). Higher education: Waking up to the importance of accreditation. Change, 37(3), 35–41.

- Sharon, A. Aiken-Wisniewski ; Joshua S. Smith ; Wendy G. Troxel (2010). Expanding Research in Academic Advising: Methodological Strategies to Engage Advisors in Research. NACADA Journal (2010) 30 (1): 4–13. [CrossRef]

- Appleby, D. C. (2002). The teaching-advising connection. In S. F. Davis & W. Buskist (Eds.), The teaching of psychology: Essays in honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie and Charles L. Braver. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Appleby, D. C. (2008). Advising as teaching and learning. In V. N. Gordon, W. R. Habley & T. J. Grites (Eds.), Academic Advising: A comprehensive handbook (second edn.) (pp. 85–102). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Campbell, S. (2005a). Why do assessment of academic advising? Part I. Academic Advising Today, 28(3), 1, 8.

- Campbell, S. (2005b). Why do assessment of academic advising? Part II. Academic Advising Today, 28(4), 13–14.

- Campbell, S. M. , & Nutt, C. L. (2008). Academic advising in the new global century: Supporting student engagement and learning outcomes achievement. Peer Review, 10(1), 4–7.

- Gordon, V., N. (2019). Developmental Advising: The Elusive Ideal. NACADA Journal (2019) 39 (2): 72–76. [CrossRef]

- Habley, W., R. And Morales, R., H. (1998). Advising Models: Goal Achievement and Program Effectiveness. NACADA Journal (1998) 18 (1): 35–41. [CrossRef]

- He, Y. , & Hutson, B. (2017). Assessment for faculty advising: Beyond the service component. NACADA Journal, 37(2), 66–75. [CrossRef]

- Kraft-Terry, S. , & Cheri, K. (2019). Direct Measure Assessment of Learning Outcome–Driven Proactive Advising for Academically At-Risk Students. NACADA Journal (2019) 39 (1): 60–76. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. (2000). Assessing the effectiveness of the advising program. In V. N. Gordon & W. R. Habley (Eds.), Academic advising: A comprehensive handbook. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Powers, K. L. , Carlstrom, A. H., & Hughey, K. F. (2014). Academic advising assessment practices: Results of a national study. NACADA Journal, 34(1), 64–77. [CrossRef]

- Swing, R. L. (Ed.) . (2001). Proving and improving: Strategies for assessing thejirst year of college (Monograph Series No. 33). U: Columbia, SC.

- Information on EvalTools®. http://www.makteam.com.

- Jeschke, M. P. , Johnson, K. E., & Williams, J. R. (2001). A comparison of intrusive and prescriptive advising of psychology majors at an urban comprehensive university. NACADA Journal, 21(1–2), 46–58. [CrossRef]

- Kadar, R. S. (2001). A counseling liaison model of academic advising. Journal of College Counseling, 4(2), 174–178. [CrossRef]

- Banta, T. W. , Hansen, M. J., Black, K. E., & Jackson, J. E. (2002). Assessing advising outcomes. NACADA Journal: spring, 22(1), 5–14. [CrossRef]

- National Academic Advising Association (NACADA) 2023. Kansas State University. KS, USA. https://nacada.ksu.

- Ibrahim, W. , Atif, Y., Shuaib, K., Sampson, D. (2015). A Web-Based Course Assessment Tool with Direct Mapping to Student Outcomes. Educational Technology & Society, 18 (2), 46–59.

- Kumaran, V., S. & Lindquist, T., E. (2007). Web-based course information system supporting accreditation. Proceedings of the 2007 Frontiers In Education conference. http://fieconference.org/fie2007/papers/1621.

- McGourty, J. , Sebastian, C., & Swart, W. (1997). Performance measurement and continuous improvement of undergraduate engineering education systems. Proceedings of the 1997 Frontiers in Education Conference, Pittsburgh, Pa. –8. IEEE Catalog no. 97CH36099 (pp. 1294–1301). 5 November.

- McGourty, J. , Sebastian, C. ( 87(4), 355–361. [CrossRef]

- Pallapu, S. K. (2005). Automating outcomes based assessment. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.199.4160&rep=rep1&type=pdf. 4160. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, W. , Mak, F., Addas, M. F. (2016). ‘Engineering Program Evaluations Based on Automated Measurement of Performance Indicators Data Classified into Cognitive, Affective, and Psychomotor Learning Domains of the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy,’ ASEE 123rd Annual Conference and Exposition, –29, New Orleans, LA. https://peer.asee. 26 June.

- Hussain, W. , & Spady, W. (2017). ‘Specific, Generic Performance Indicators and Their Rubrics for the Comprehensive Measurement of ABET Student Outcomes,’ ASEE 124th Annual Conference and Exposition, –28, Columbus, OH. 25 June.

- Mak, F. , & Sundaram, R. (2016). ‘Integrated FCAR Model with Traditional Rubric-Based Model to Enhance Automation of Student Outcomes Evaluation Process,’ ASEE 123rdAnnual Conference and Exposition, –29, New Orleans, LA. 26 June.

- Eltayeb, M. , Mak, F., Soysal, O. (2013).Work in progress: Engaging faculty for program improvement via EvalTools®: A new software model. 2013 Frontiers in Education conference FIE. 2012 (pp.1-6). [CrossRef]

- W. Hussain, W. G. Spady, M. T. Naqash, S. Z. Khan, B. A. Khawaja and L. Conner, "ABET Accreditation During and After COVID19 - Navigating the Digital Age," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 218997-21 9046, 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spady, W. & Marshall, K. J. (91). Beyond traditional outcome-based education. 19 October; 49.

- Spady, W. (88). Organizing for results: The basis of authentic restructuring and reform. Educational Leadership, 46, 7. 19 October.

- Spady, W. (summer 1992).

- Hussain, W. (2016) Automated engineering program evaluations—Learning domain evaluations—CQI. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VR4fsD97KD0.

- Hussain, W. (2017) Specific performance indicators.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9aKfJcJkNk.

- Hussain, W. , Addas, M. F., & Mak, F. (2016, October). Quality improvement with automated engineering program evaluations using performance indicators based on Bloom’s 3 domains. In Frontiers in education conference (FIE), 2016 IEEE, pp. 1–9. IEEE.

- Hussain, W. , & Addas, M. F. (2016, April). Digitally automated assessment of outcomes classified per Bloom’s Three Domains and based on frequency and types of assessments. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA). http://www.learningoutcomesassessment.org/documents/Hussain_Addas_Assessment_in_Practice.pdf.

- Hussain, W. , & Addas, M. F. (2015). “A Digital Integrated Quality Management System for Automated Assessmentof QIYAS Standardized Learning Outcomes”, 2nd International Conference on Outcomes Assessment (ICA), 2015, QIYAS, Riyadh, KSA.

- Estell, J. K. , Yoder, J-D. S., Morrison, B. B., & Mak, F. K. (2012). Improving upon best practices: FCAR 2. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. , & Chen, L. (2012). 29 March 2012; 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, F. , & Kelly, J. (2010). Systematic means for identifying and justifying key assignments for effective rules-based program evaluation. 40th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, –30, Washington, DC. 27 October.

- Miller, R. L. , & Olds, B. M. (1999). Performance assessment of EC-2000 student outcomes in the unit operations laboratory. ASEE Annual Conference Proceedings, 1999.

- Mead, P. F. , & Bennet, M. M. (2009). Practical framework for Bloom’s based teaching and assessment of engineering outcomes. Education and training in optics and photonics 2009. Optical Society of America, paper ETB3. [CrossRef]

- Mead, P. F. , Turnquest, T. T., & Wallace, S., D. (2006). Work in progress: Practical framework for engineering outcomes-based teaching assessment—A catalyst for the creation of faculty learning communities. 36th Annual Frontiers in Education Conference, pp. 19–20). [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, K.R. , & Okamoto, N. (2018). Improving Instruction and Assessment via Bloom’s Taxonomy and Descriptive Rubrics. ASEE 125th Annual Conference and Exposition, –28, Salt Lake City, UT. 25 June.

- Jonsson, A. , & Svingby, G. (2007). The use of scoring rubrics: Reliability, validity and educational consequences. Educational Research Review, 2(2), 130–144. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1747938X07000188. [CrossRef]

- Information on Blackboard®. https://www.blackboard.com/teaching-learning/learning-management/blackboard-learn.

|

| Area | Pedagogical Aspects | Digital Developmental Advising | Prevalent Traditional Advising | Sectional References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authentic OBE and Conceptual Frameworks | Based on Authentic OBE Frameworks | Maximum fulfillment of authentic OBE frameworks | Partial or Minimal fulfillment of authentic OBE frameworks | I, III.C, IV.A |

| Standards of Language of Outcomes | Maximum fulfillment of consistent OBE frameworks | Partial or Minimal fulfillment and lack of any consistent frameworks | I, III.C, IV.A, IV.B | |

| Assess students | All students assessed | Random or Select Sampling | I, III.C, IV.A, IV.B | |

| Specificity of Outcomes | Mostly specific resulting in valid and reliable outcomes data | Mostly generic resulting in vague and inaccurate results | I, III.C, IV.A, IV.B | |

| Coverage of Bloom’s 3 Learning Domains and Learning Levels | Specific PIs that are classified according to Bloom’s 3 learning domains and their learning levels | Generic PIs that have no classification | I, IV.B | |

| ‘Design Down’ Implementation | OBE power principle design down is fully implemented with specific PIs used to assess the course outcomes | OBE power principle design down is partially implemented with generic PIs used to assess the program outcomes | IV.B | |

| Assessment Practices | Description of Rubrics | Hybrid rubrics that are combination of analytic and holistic, topic specific, provide detailed steps, scoring information and descriptors | Mostly holistic generic rubrics, some could be analytic, rarely topic specific or provide detailed steps, without scoring information and detailed descriptors | IV.B |

| Application of Rubrics | Applied to most course learning activities with tight alignment | Applied to just major learning activities at the program level with minimal alignment | IV.B | |

| Embedded Assessments | The course outcomes and PIs follow consistent frameworks and are designed to enable embedded assessments methodology | The course outcomes and PIs do not follow consistent frameworks and are not designed to enable embedded assessments methodology | IV.B, IV.C | |

| Quality of Outcomes Data | Validity & Reliability of Outcomes Data | Specific outcomes and PIs, consistent frameworks and hybrid rubrics produce comprehensive and accurate assessment data for all students. Therefore, outcomes data can be used for advising purposes. | Generic outcomes and PIs, lack of consistent frameworks, and generic rubrics produce vague and inaccurate assessment data for small samples of students. Therefore, outcomes data cannot be used for advising purposes. | I, III.C, IV.B, IV.C, V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G, V.H |

| Statistical Power | Heterogeneous and accurate data. All students, All courses and All major assessments sampled | Random or selective sampling of students, courses and assessments | III.C, IV.A, IV.B, IV.C | |

| Quality of Multi-term SOs Data | Valid and reliable data. All data is collected from direct assessments by implementing: several essential elements of comprehensive assessment methodology specific PIs wide application of hybrid rubrics strictly following stringent QA processes and monitoring ensuring tight alignment with student learning. |

Usually not available and unreliable. Due to lack of: comprehensive assessment process specific PIs wide usage of rubrics stringent QA processes and appropriate technology. |

1, III.C, IV.A, IV.B, IV.C | |

| Staff | Access to Students Skills and Knowledge Information | Advisors can easily access student outcomes, assessment, and objective evidence besides academic transcripts information | Advisors cannot access student outcomes, assessment, and objective evidence. Advising is fully based on academic transcripts information | I, III.C, IV.B, IV.C, V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G, V.H |

| Advisor Interactions | Advisors have full access to detailed student past and present course performances thereby providing accurate informational resources to facilitate productive advisor-course instructor dialog | Advisors do not have access to any detail related to student past or present course performances thereby lacking any information resources for productive advisor-course instructor dialog | I, III.C, V, V.B, V.C | |

| Performance Criteria | Advisors apply detailed performance criteria and heuristics rules based on a scientific color coded flagging scheme to evaluate attainment of students outcomes | Advisors do not refer or apply any such performance criteria or heuristics rules due to lack of detailed direct assessments data and associated digital reporting technology | IV.C, V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G | |

| Access to Multi-term SOs Data | Advisors can easily access and use multi-term SOs data reports and identify performance trends and patterns for accurate developmental feedback | Advisors cannot access any type of multi-term SOs data reports and identify performance trends and patterns for accurate developmental feedback | V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G | |

| Mixed Methods Approaches to Investigation | Advisors can easily apply mixed methods approaches to investigation and feedback for effective developmental advising due to availability of accurate outcomes data, specific PIs and assessment information presented in organized formats using state of the art digital diagnostic reports | Advisors cannot apply mixed methods approaches to investigation and feedback for effective developmental advising due to lack of availability of accurate outcomes data, specific PIs and assessment information presented in organized formats using state of the art digital diagnostic reports | V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G | |

| Students | Student Accessibility of outcomes data | All students can review their detailed outcomes based performances, assessments information for multiple terms and examine trends in improvement or any failures | Students cannot review any form of outcomes based performances, assessments information for multiple terms and cannot examine trends in improvement or any failures | V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G |

| Student Follow Up Actions for Improvement | Both students and advisors can track outcomes based performances and systematically follow up on recommended remedial actions using digital reporting features | Both students and advisors cannot track outcomes based performances and therefore cannot systematically follow up on any recommended remedial actions | V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G | |

| Student Attainment of Lifelong Learning Skills | Students can use self-evaluations forms and reinforce their remediation efforts with guidance from advisors to enhance metacognition capabilities and eventually attain lifelong learning skills | Students do not have any access to outcomes data and therefore cannot conduct any form of self-evaluation for outcomes performances and therefore cannot collaborate with any advisors guidance on outcomes | V.E, V.F, V.G | |

| Process | Integration with Digital Technology | Pedagogy and assessment methodology fully support integration with digital technology that employs embedded assessments | Language of outcomes, alignment issues, lack of rubrics make it difficult to integrate with digital technology employing embedded assessments | I, IV.C, V.A, V.B, V.C, V.D, V.E, V.F, V.G |

| PDCA Quality Processes | 6 Comprehensive PDCA Quality Cycles for Stringent Quality standards, monitoring and control of education process | Lack of Well Organized and Stringent QA cycles or measures and technology for implementing education process. | I, III.C, IV.C | |

| Impact Evaluation of Advising | Credible impact evaluations of developmental advising can be conducted by applying qualifying rubrics to multi-year SOs direct assessment trend analyses information. There is no need of control or focus groups and credibility issues related to student survey feedback. | Impact evaluations are usually based on indirect assessments collected using student surveys. Several issues related to use of control or focus groups and credibility of feedback have to be accordingly dealt with. | V.H |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).