Submitted:

04 June 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Enhancing Efficacy through Multi-Targeting:

1.3. Improving Persistence and Longevity:

1.4. Expanding the Scope to Solid Tumors:

1.5. Addressing Safety Concerns:

1.6. CD19 Is a Crucial Target Antigen in B Cell Malignancies

2. Pathophysiology of CAR-T Cell Therapy Related Toxicities

2.1. Cytokine-Release Syndrome (CRS)

2.2. T and B Lymphocytes Aplasia and Opportunistic Infections

2.3. CRS-Related Coagulopathy

2.4. Cytopenias

2.5. Antigen Mutation

2.6. Neurotoxicity in CAR-T Cell Therapy

2.7. Graft-Versus-Host Disease (GVHD) in CAR-T Cell Therapy:

3. CAR-T Cell Therapy Related Toxicities

3.1. Management of Cytokine-Release Syndrome (CRS)

- Tocilizumab: Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor, thereby inhibiting the pro-inflammatory effects of IL-6. It is considered the primary recommendation for symptom relief in CRS associated with CAR-T cell therapy [36] .

- Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids may be used in conjunction with tocilizumab, particularly in severe cases of CRS. They help suppress inflammation and mitigate immune responses [88].

- Anakinra: Anakinra is an IL-1 receptor antagonist that has shown promise in alleviating both CRS and CRES (CAR-T cell-related encephalopathy syndrome). It can be used as an alternative or adjunctive therapy in managing CRS [88]

- GM-CSF deficiency or inhibition: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) deficiency or inhibition has been found to alleviate CRS and CRES while enhancing CAR-T cell anti-tumor effects. This suggests that targeting GM-CSF may be a potential therapeutic strategy for managing CRS [89].

- Reduction of tumor burden: Tumor burden positively correlates with CRS severity. Therefore, reducing tumor burden with traditional chemotherapy or radiotherapy before CAR-T cell infusion may help mitigate the risk and severity of CRS [36].

- Mechanistic understanding: Understanding the underlying mechanisms of CRS, including rapid CAR-T cell activation, cytokine secretion, and immune cell interactions (such as CD40/CD40L), can aid in developing targeted therapies and improving management strategies [87].

3.2. Management of CRS-Related Coagulopathy

- Monitoring: Regular monitoring of coagulation parameters, including prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen levels, and D-dimer levels, is essential for early detection of coagulopathy and timely intervention [59]. Imaging studies such as ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scans may also be necessary to assess for thrombotic complications.

- Risk stratification: Identifying patients at higher risk for developing CRS-related coagulopathy based on factors such as disease characteristics, tumor burden, and baseline coagulation profile can help tailor monitoring and treatment approaches [81].

- Individualized treatment: Treatment strategies should be individualized based on the severity of coagulopathy and the patient’s clinical status. In addition to anticoagulant drugs and replacement therapy, interventions such as fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support may be necessary to maintain hemodynamic stability [90].

- Management of underlying conditions: Addressing underlying conditions that may predispose patients to coagulopathy, such as infections or pre-existing coagulopathies, is crucial for optimal management [82] .

- Collaborative care: Close collaboration between hematologists, oncologists, intensivists, and other healthcare providers is essential for the multidisciplinary management of CRS- related coagulopathy, ensuring timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment [91].

3.3. The Management of T and B Lymphocytes Aplasia and Opportunistic Infections in the Context of CAR-T Cell Therapy Involves Several Key Strategies to Mitigate the Risks and Complications Associated with Immune System Compromise

- Immunoglobulin Supplementation: Given the impaired humoral immunity resulting from the depletion of normal B cells, immunoglobulin supplementation is crucial to restore humoral immunity and reduce the risk of infections. Regular monitoring of gamma globulin levels is essential, and supplementation should be initiated as necessary [92,93,94].

- Infection Monitoring and Prophylaxis: Patients undergoing CAR-T cell therapy are at increased risk of infections, particularly within the first 30 days post-infusion. Close monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection is essential. Prophylactic measures, such as administering acyclovir to prevent herpesvirus infections, are recommended [81].

- Management of Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS): CRS is a common complication of CAR-T cell therapy and can present with symptoms similar to those of infections. Distinguishing between CRS and infections is crucial for appropriate management. IL-6 plays a significant role in both CRS and infection-induced cytokine storms. Monitoring serum IL-6 levels can help differentiate between the two conditions. Prompt initiation of empiric anti-infective treatment, especially in neutropenic patients, is essential [81].

- Antiviral Prophylaxis for HBV Reactivation: Patients with resolved HBV infections are at risk of HBV reactivation following CAR-T cell therapy. Antiviral prophylaxis and regular monitoring for HBV reactivation are necessary to prevent complications [81].

- Dose-Escalation Regimens: High-dose CAR-T cell infusion may increase the risk of infections. Utilizing dose-escalation regimens may help mitigate this risk while maintaining therapeutic efficacy [86]. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing CAR-T cell therapy is essential to monitor for potential late-onset complications, including infections and immune system dysregulation.

3.4. Management of Cytopenias

- Cytokine Support: Administering cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), granulocyte colony- stimulating factor (G-CSF), or erythropoietin can help stimulate the production of specific blood cell types, thereby mitigating cytopenia. For example, IL-6 receptor blockade with tocilizumab has been used to manage cytokine release syndrome (CRS) associated with CAR-T cell therapy, which can also help in restoring blood cell counts [88].

- Transfusion Support: Blood transfusions, including packed red blood cells (PRBCs), platelets, and sometimes granulocyte transfusions, may be necessary to manage anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia resulting from CAR-T cell therapy-induced cytopenia [95].

- Growth Factors: Administration of growth factors such as G-CSF and erythropoietin can stimulate the production of neutrophils and red blood cells, respectively, thereby aiding in the recovery from neutropenia and anemia [96].

- Supportive Care: Maintaining hydration, electrolyte balance, and nutritional support is crucial for patients undergoing CAR-T cell therapy to support bone marrow recovery and mitigate the effects of cytopenia [97].

- Adjusting CAR-T Dose and Conditioning Regimens: Modifying the dose of CAR-T cells administered or adjusting the conditioning regimens used before CAR-T infusion may help reduce the severity of cytopenia while maintaining anti-tumor efficacy [98] .

3.5. GVHD Management

-

Immunosuppressive Medications:

- -

- Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) are often used as a first-line treatment.

- -

- Calcineurin inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporine, tacrolimus) are commonly employed to suppress the immune response.

-

Anti-thymocyte Globulin (ATG):

- -

- ATG can be used as part of the conditioning regimen before transplantation to reduce the risk of GVHD.

-

T-Cell Depletion:

- -

- Techniques to selectively remove T cells from the donor graft can reduce the risk of GVHD.

-

Photopheresis:

- -

- Extracorporeal photopheresis is a therapeutic option that involves collecting the patient’s white blood cells, treating them with a photosensitizing agent, and then exposing them to ultraviolet light before returning them to the patient.

-

Topical Therapy:

- -

- For skin involvement, topical corticosteroids or other skin-directed therapies may be employed.

-

Supportive Care:

- -

- Nutritional support, hydration, and infection prevention are crucial components of GVHD management.

| CAR-T cell Therapy | Targeted antigen |

Cancer Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| bb21217 | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | Enhanced persistence CAR-T therapy; in clinical trials |

| CTL019 | CD19 | B-cell malignancies | Early version of Kymriah; basis for FDA-approved therapy |

| CART-PSMA | PSMA | Prostate cancer | Investigational CAR-T therapy; in early-phase trials |

| CAR-EGFRvIII | EGFRvIII | Glioblastoma | Investigational CAR-T therapy targeting specific EGFR mutation |

| Mesothelin-CAR-T | Mesothelin | Mesothelioma, ovarian cancer | Experimental CAR-T therapy targeting mesothelin |

| MUC1-CAR-T | MUC1 | Various solid tumours | Investigational CAR-T therapy for multiple epithelial cancers |

| Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) | CD19 | B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) | First FDA-approved CAR-T therapy for paediatric and young adult patients |

| Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) | CD19 | Large B-cell lymphoma | Approved for adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma |

| Tecartus (brexucabtagene autoleucel) | CD19 | Mantle cell lymphoma | Approved for adults with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma |

| Breyanzi (lisocabtagene maraleucel) | CD19 | Large B-cell lymphoma | Approved for adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma |

| Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel) | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | First FDA-approved CAR-T therapy targeting BCMA for multiple myeloma |

| Carvykti (ciltacabtagene autoleucel) | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | Another BCMA-targeting CAR-T therapy for multiple myeloma |

| ALLO-501 (Allogeneic) | CD19 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Allogeneic CAR-T therapy under investigation; uses donor-derived cells |

| JCARH125 | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | Experimental CAR-T therapy; in clinical trials |

| CT053 | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | Investigational CAR-T therapy; in clinical trials |

| Method Type |

Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Methods |

Flow cytometry | Uses fluorescently labeled antibodies to measure the binding of CAR-T cells to antigens | High throughput, quantitative, multiple parameters | Requires fluorophore-labelled antibodies, can be costly |

| Conventional Methods |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | Measures binding indirectly by detecting cytokines or other proteins released upon CAR-T cell activation | Sensitive, quantitative | Indirect measurement, labor-intensive, endpoint analysis |

| Conventional Methods |

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Detects CAR-T cell binding to antigens in tissue sections using specific antibodies | Visual localization, can analyse tissue architecture | Qualitative, less quantitative, requires tissue samples |

| Conventional Methods |

Radioimmunoassay (RIA) | Uses radiolabelled antigens to study binding interactions | Highly sensitive, quantitative | Use of radioisotopes, safety concerns, expensive equipment |

| Advanced Methods |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures real-time binding kinetics of CAR-T cells to antigens on a sensor chip | Real-time data, kinetic analysis, no labelling required | Expensive, requires Specialized equipment |

| Advanced Methods |

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq) | Analyses gene expression of individual CAR-T cells to infer binding and activation states | High resolution, comprehensive data | Complex data analysis, high cost |

| Advanced Methods |

CRISPR Screening | Uses CRISPR/Cas9 to identify genes involved in CAR-T cell binding and activation | High-throughput, functional insights | Requires extensive validation, expensive |

| Advanced Methods |

Microscopy (Confocal, TIRF) | Visualizes the interaction of CAR-T cells with antigen-expressing cells using high-resolution imaging | High spatial resolution, dynamic studies possible | Limited to surface interactions, expensive equipment |

| Advanced Methods |

Mass Cytometry (CyTOF) | Combines flow cytometry with mass spectrometry for detailed phenotypic analysis | Multiparametric, high dimensional data | Requires specialized equipment, complex data interpretation |

| Advanced Methods |

Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) | Measures binding interactions by detecting changes in optical thickness on a biosensor surface | Real-time data, label-free | Less sensitive than SPR, limited to specific applications |

| Advanced Methods |

Multiplexed Cytokine Assays | Simultaneously measures multiple cytokines released upon CAR-T cell binding using bead-based methods | High throughput, comprehensive profiling | Requires multiplexing capability, can be costly |

| Advanced Methods |

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Measures the forces involved in CAR-T cell binding to antigens at the nanoscale | High sensitivity, detailed mechanical data | Technically challenging, expensive, limited throughput |

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Y. CAR-T Cell Therapy in Hematological Malignancies: Current Opportunities and Challenges. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 927153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.J.; Bishop, M.R.; Tam, C.S.; Waller, E.K.; Borchmann, P.; McGuirk, J.P.; Jäger, U.; Jaglowski, S.; Andreadis, C.; Westin, J.R.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, W.; Shi, M.; Yang, J.; Cao, J.; Xu, L.; Yan, D.; Yao, M.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; et al. Phase II Trial of Co-Administration of CD19- and CD20-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Relapsed and Refractory Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 5827–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Locke, F.L.; Bartlett, N.L.; Lekakis, L.J.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Braunschweig, I.; Oluwole, O.O.; Siddiqi, T.; Lin, Y.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T- Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.A.; Chavez, J.C.; Sehgal, A.R.; William, B.M.; Munoz, J.; Salles, G.; Munshi, P.N.; Casulo, C.; Maloney, D.G.; de Vos, S.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel in Relapsed or Refractory Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (ZUMA-5): A Single-Arm, Multicentre, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, F.L.; Ghobadi, A.; Jacobson, C.A.; Miklos, D.B.; Lekakis, L.J.; Oluwole, O.O.; Lin, Y.; Braunschweig, I.; Hill, B.T.; Timmerman, J.M.; et al. Long-Term Safety and Activity of Axicabtagene Ciloleucel in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma (ZUMA-1): A Single-Arm, Multicentre, Phase 1-2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Mo, F.; McKenna, M.K. Impact of Manufacturing Procedures on CAR T Cell Functionality. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 876339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, R.P.; Vessillier, S.; Rafiq, Q.A. Lentiviral Vectors for T Cell Engineering: Clinical Applications, Bioprocessing and Future Perspectives. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, M.; Solomon, S.R.; Arnason, J.; Johnston, P.B.; Glass, B.; Bachanova, V.; Ibrahimi, S.; Mielke, S.; Mutsaers, P.; Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, F.; et al. Lisocabtagene Maraleucel versus Standard of Care with Salvage Chemotherapy Followed by Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation as Second-Line Treatment in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma (TRANSFORM): Results from an Interim Analysis of an Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 2294–2308. [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal, A.; Hoda, D.; Riedell, P.A.; Ghosh, N.; Hamadani, M.; Hildebrandt, G.C.; Godwin, J.E.; Reagan, P.M.; Wagner-Johnston, N.; Essell, J.; et al. Lisocabtagene Maraleucel as Second-Line Therapy in Adults with Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma Who Were Not Intended for Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (PILOT): An Open-Label, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Yassine, F.; Moustafa, M.A.; Iqbal, M.; Murthy, H. Lisocabtagene Maraleucel in Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: What Is the Evidence? Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2022, 15, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, N.C.; Anderson, L.D., Jr; Shah, N.; Madduri, D.; Berdeja, J.; Lonial, S.; Raje, N.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Oriol, A.; et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.K.; Sidana, S.; Peres, L.C.; Colin Leitzinger, C.; Shune, L.; Shrewsbury, A.; Gonzalez, R.; Sborov, D.W.; Wagner, C.; Dima, D.; et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel for Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Real-World Experience From the Myeloma CAR T Consortium. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2087–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, S.; Lin, Y.; Goldschmidt, H.; Reece, D.; Nooka, A.; Senin, A.; Rodriguez-Otero, P.; Powles, R.; Matsue, K.; Shah, N.; et al. KarMMa-RW: Comparison of Idecabtagene Vicleucel with Real-World Outcomes in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeja, J.G.; Madduri, D.; Usmani, S.Z.; Jakubowiak, A.; Agha, M.; Cohen, A.D.; Stewart, A.K.; Hari, P.; Htut, M.; Lesokhin, A.; et al. Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel, a B-Cell Maturation Antigen-Directed Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): A Phase 1b/2 Open-Label Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.-Q.; Zhao, W.; Jing, H.; Fu, W.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, D.; Chen, D.; Schecter, J.M.; et al. Phase II, Open-Label Study of Ciltacabtagene Autoleucel, an Anti-B- Cell Maturation Antigen Chimeric Antigen Receptor-T-Cell Therapy, in Chinese Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (CARTIFAN-1). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindo, L.; Wilkinson, L.H.; Hay, K.A. Befriending the Hostile Tumor Microenvironment in CAR T-Cell Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 618387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.; Gottschalk, S. Engineered Cytokine Signaling to Improve CAR T Cell Effector Function. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 684642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cantillo, G.; Urueña, C.; Camacho, B.A.; Ramírez-Segura, C. CAR-T Cell Performance: How to Improve Their Persistence? Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 878209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, C.; Venetis, K.; Sajjadi, E.; Zattoni, L.; Curigliano, G.; Fusco, N. CAR-T Cell Therapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Other Solid Tumors: Preclinical and Clinical Progress. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2022, 31, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, G.; Reed, M.R.; Bielamowicz, K.; Koss, B.; Rodriguez, A. CAR-T Therapies in Solid Tumors: Opportunities and Challenges. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2023, 25, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roex, G.; Campillo-Davo, D.; Flumens, D.; Shaw, P.A.G.; Krekelbergh, L.; De Reu, H.; Berneman, Z.N.; Lion, E.; Anguille, S. Two for One: Targeting BCMA and CD19 in B-Cell Malignancies with off-the-Shelf Dual-CAR NK-92 Cells. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viardot, A.; Locatelli, F.; Stieglmaier, J.; Zaman, F.; Jabbour, E. Concepts in Immuno- Oncology: Tackling B Cell Malignancies with CD19-Directed Bispecific T Cell Engager Therapies. Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 2215–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, K.A.; Turtle, C.J. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells: Lessons Learned from Targeting of CD19 in B-Cell Malignancies. Drugs 2017, 77, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, P.; Neelapu, S.S. CAR-T Failure: Beyond Antigen Loss and T Cells. Blood 2021, 137, 2567–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgaonkar, A.; Udayakumar, D.; Yang, Y.; Harris, S.; Öz, O.K.; Ramakrishnan Geethakumari, P.; Sun, X. Current and Potential Roles of Immuno-PET/-SPECT in CAR T- Cell Therapy. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1199146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duell, J.; Leipold, A.M.; Appenzeller, S.; Fuhr, V.; Rauert-Wunderlich, H.; Da Via, M.; Dietrich, O.; Toussaint, C.; Imdahl, F.; Eisele, F.; et al. Sequential Antigen Loss and Branching Evolution in Lymphoma after CD19- and CD20-Targeted T-Cell-Redirecting Therapy. Blood 2024, 143, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haideri, M.; Tondok, S.B.; Safa, S.H.; Maleki, A.H.; Rostami, S.; Jalil, A.T.; Al-Gazally, M.E.; Alsaikhan, F.; Rizaev, J.A.; Mohammad, T.A.M.; et al. CAR-T Cell Combination Therapy: The next Revolution in Cancer Treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lei, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Fu, R. Challenges and Strategies Associated with CAR-T Cell Therapy in Blood Malignancies. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, J.H.; Frank, M.J.; Craig, J.; Patel, S.; Spiegel, J.Y.; Sahaf, B.; Oak, J.S.; Younes, S.F.; Ozawa, M.G.; Yang, E.; et al. CD22-Directed CAR T-Cell Therapy Induces Complete Remissions in CD19-Directed CAR-Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2021, 137, 2321–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maude, S.L.; Laetsch, T.W.; Buechner, J.; Rives, S.; Boyer, M.; Bittencourt, H.; Bader, P.; Verneris, M.R.; Stefanski, H.E.; Myers, G.D.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maus, M.V.; June, C.H. Making Better Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Adoptive T-Cell Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.; Rivière, I. The Basic Principles of Chimeric Antigen Receptor Design. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- June, C.H.; Sadelain, M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.W.; Kochenderfer, J.N.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Cui, Y.K.; Delbrook, C.; Feldman, S.A.; Fry, T.J.; Orentas, R.; Sabatino, M.; Shah, N.N.; et al. T Cells Expressing CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia in Children and Young Adults: A Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maude, S.L.; Frey, N.; Shaw, P.A.; Aplenc, R.; Barrett, D.M.; Bunin, N.J.; Chew, A.; Gonzalez, V.E.; Zheng, Z.; Lacey, S.F.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells for Sustained Remissions in Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B.L.; Miskin, J.; Wonnacott, K.; Keir, C. Global Manufacturing of CAR T Cell Therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2017, 4, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turtle, C.J.; Hanafi, L.-A.; Berger, C.; Hudecek, M.; Pender, B.; Robinson, E.; Hawkins, R.; Chaney, C.; Cherian, S.; Chen, X.; et al. Immunotherapy of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma with a Defined Ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 355ra116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuser, C.; Hombach, A.; Lösch, C.; Manista, K.; Abken, H. T-Cell Activation by Recombinant Immunoreceptors: Impact of the Intracellular Signalling Domain on the Stability of Receptor Expression and Antigen-Specific Activation of Grafted T Cells. Gene Ther. 2003, 10, 1408–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedan, S.; Posey, A.D., Jr; Shaw, C.; Wing, A.; Da, T.; Patel, P.R.; McGettigan, S.E.; Casado-Medrano, V.; Kawalekar, O.U.; Uribe-Herranz, M.; et al. Enhancing CAR T Cell Persistence through ICOS and 4-1BB Costimulation. JCI Insight 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, H.M.; Akbar, A.N.; Lawson, A.D.G. Activation of Resting Human Primary T Cells with Chimeric Receptors: Costimulation from CD28, Inducible Costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in Series with Signals from the TCR Zeta Chain. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.-G.; Ye, Q.; Poussin, M.; Harms, G.M.; Figini, M.; Powell, D.J., Jr. CD27 Costimulation Augments the Survival and Antitumor Activity of Redirected Human T Cells in Vivo. Blood 2012, 119, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guercio, M.; Orlando, D.; Di Cecca, S.; Sinibaldi, M.; Boffa, I.; Caruso, S.; Abbaszadeh, Z.; Camera, A.; Cembrola, B.; Bovetti, K.; et al. CD28.OX40 Co-Stimulatory Combination Is Associated with Long in Vivo Persistence and High Activity of CAR.CD30 T-Cells. Haematologica 2021, 106, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Xia, K.; Xie, Y.; Ye, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, R.; Long, J.; Wei, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. Combination of 4-1BB and DAP10 Promotes Proliferation and Persistence of NKG2D(bbz) CAR-T Cells. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 893124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Sun, M.; Li, B.; Pan, F.; Ma, A.; Liao, J.; Yin, T.; Tang, X.; Huang, G.; et al. IL-12 Nanochaperone-Engineered CAR T Cell for Robust Tumor-Immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2022, 281, 121341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avanzi, M.P.; Yeku, O.; Li, X.; Wijewarnasuriya, D.P.; van Leeuwen, D.G.; Cheung, K.; Park, H.; Purdon, T.J.; Daniyan, A.F.; Spitzer, M.H.; et al. Engineered Tumor-Targeted T Cells Mediate Enhanced Anti-Tumor Efficacy Both Directly and through Activation of the Endogenous Immune System. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2130–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewski, M.; Abken, H. CAR T Cells Releasing IL-18 Convert to T-Bethigh FoxO1low Effectors That Exhibit Augmented Activity against Advanced Solid Tumors. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 3205–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obstfeld, A.E.; Frey, N.V.; Mansfield, K.; Lacey, S.F.; June, C.H.; Porter, D.L.; Melenhorst, J.J.; Wasik, M.A. Cytokine Release Syndrome Associated with Chimeric-Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy: Clinicopathological Insights. Blood 2017, 130, 2569–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Sun, L.; Xing, C.; Zhang, S.; Yu, K. Prognostic Significance of Cytokine Release Syndrome in B Cell Hematological Malignancies Patients After Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2021, 41, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norelli, M.; Camisa, B.; Barbiera, G.; Falcone, L.; Purevdorj, A.; Genua, M.; Sanvito, F.; Ponzoni, M.; Doglioni, C.; Cristofori, P.; et al. Monocyte-Derived IL-1 and IL-6 Are Differentially Required for Cytokine-Release Syndrome and Neurotoxicity due to CAR T Cells. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Tian, S.; Wang, J.; Ma, H.; Qian, K.; Zhang, X. Co-Expression of CD40/CD40L on XG1 Multiple Myeloma Cells Promotes IL-6 Autocrine Function. Cancer Invest. 2015, 33, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giavridis, T.; van der Stegen, S.J.C.; Eyquem, J.; Hamieh, M.; Piersigilli, A.; Sadelain, M. CAR T Cell-Induced Cytokine Release Syndrome Is Mediated by Macrophages and Abated by IL-1 Blockade. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; Cron, R.Q.; Hartwell, J.; Manson, J.J.; Tattersall, R.S. Silencing the Cytokine Storm: The Use of Intravenous Anakinra in Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis or Macrophage Activation Syndrome. Lancet Rheumatol 2020, 2, e358–e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhou, L.; Ye, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Tang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Qian, W.; Liang, A. Risk of HBV Reactivation in Patients With Resolved HBV Infection Receiving Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy Without Antiviral Prophylaxis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 638678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, J.; Han, M.; Meng, F.; Zhou, J. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Immunocompromised Patients: Humoral versus Cell-Mediated Immunity. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- deHaas, P.A.; Young, R.D. Attention Styles of Hyperactive and Normal Girls. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1984, 12, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, F.A.; Bernstein, I.L.; Khan, D.A.; Ballas, Z.K.; Chinen, J.; Frank, M.M.; Kobrynski, L.J.; Levinson, A.I.; Mazer, B.; Nelson, R.P., Jr; et al. Practice Parameter for the Diagnosis and Management of Primary Immunodeficiency. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005, 94, S1–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapel, H.; Cunningham-Rundles, C. Update in Understanding Common Variable Immunodeficiency Disorders (CVIDs) and the Management of Patients with These Conditions. Br. J. Haematol. 2009, 145, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Romero, F.A.; Taur, Y.; Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.J.; Hohl, T.M.; Seo, S.K. Cytokine Release Syndrome Grade as a Predictive Marker for Infections in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated With Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, J.W.Y.; Law, A.W.H.; Law, K.W.T.; Ho, R.; Cheung, C.K.M.; Law, M.F. Prevention and Management of Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation in Patients with Hematological Malignancies in the Targeted Therapy Era. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 4942–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhu, X.; Mao, X.; Huang, L.; Meng, F.; Zhou, J. Severe Early Hepatitis B Reactivation in a Patient Receiving Anti-CD19 and Anti-CD22 CAR T Cells for the Treatment of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H.; Iqbal, M.; Chavez, J.C.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A. Cytokine Release Syndrome: Current Perspectives. Immunotargets Ther 2019, 8, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsrud, A.; Craig, J.; Baird, J.; Spiegel, J.; Muffly, L.; Zehnder, J.; Tamaresis, J.; Negrin, R.; Johnston, L.; Arai, S.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors Associated with Bleeding and Thrombosis Following Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 4465–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, K.; Cheng, H.; Cao, J.; Shi, M.; Qiao, J.; Yan, Z.; Jing, G.; Pan, B.; Sang, W.; et al. Coagulation Disorders after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: Analysis of 100 Patients with Relapsed and Refractory Hematologic Malignancies. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020, 26, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Yu, Q.; Teng, X.; Guo, X.; Wei, G.; Xu, H.; Cui, J.; Chang, A.H.; Hu, Y.; Huang, H. CRS-Related Coagulopathy in BCMA Targeted CAR-T Therapy: A Retrospective Analysis in a Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavroudi, I.; Papadaki, V.; Pyrovolaki, K.; Katonis, P.; Eliopoulos, A.G.; Papadaki, H.A. The CD40/CD40 Ligand Interactions Exert Pleiotropic Effects on Bone Marrow Granulopoiesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011, 89, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Gao, S.; Shao, Q.; Yue, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Shao, Z.; Fu, R. Case Report: Sirolimus Alleviates Persistent Cytopenia After CD19 CAR-T-Cell Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 798352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, R.; Graham, C.; Yallop, D.; Jozwik, A.; Mirci-Danicar, O.C.; Lucchini, G.; Pinner, D.; Jain, N.; Kantarjian, H.; Boissel, N.; et al. Genome-Edited, Donor-Derived Allogeneic Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Paediatric and Adult B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Results of Two Phase 1 Studies. Lancet 2020, 396, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Tang, K.; Luo, Y.; Seery, S.; Tan, Y.; Deng, B.; Liu, F.; Xu, X.; Ling, Z.; Song, W.; et al. Sequential CD19 and CD22 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy for Childhood Refractory or Relapsed B-Cell Acute Lymphocytic Leukaemia: A Single-Arm, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.N.; Fry, T.J. Mechanisms of Resistance to CAR T Cell Therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sun, Q.; Liang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Tu, H.; Liu, Y.; Tu, S.; et al. Mechanisms of Relapse After CD19 CAR T-Cell Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Its Prevention and Treatment Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, L. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy for Pediatric B-ALL: Narrowing the Gap Between Early and Long-Term Outcomes. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leahy, A.B.; Newman, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Myers, R.; DiNofia, A.; Dolan, J.G.; Callahan, C.; Baniewicz, D.; Devine, K.; et al. CD19-Targeted Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy for CNS Relapsed or Refractory Acute Lymphocytic Leukaemia: A Post-Hoc Analysis of Pooled Data from Five Clinical Trials. Lancet Haematol 2021, 8, e711–e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, P.J.; Roddie, C.; Bader, P.; Basak, G.W.; Bonig, H.; Bonini, C.; Chabannon, C.; Ciceri, F.; Corbacioglu, S.; Ellard, R.; et al. Management of Adults and Children Receiving CAR T-Cell Therapy: 2021 Best Practice Recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE) and the European Haematology Association (EHA). Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ganapathy, T.; Radhakrishnan, R.; Sakshi, S.; Martin, S. CAR γδ T Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy. Is the Field More Yellow than Green? Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, H.R.; Mirzaei, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Hadjati, J.; Till, B.G. Prospects for Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) γδ T Cells: A Potential Game Changer for Adoptive T Cell Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2016, 380, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Deng, B.; Yin, Z.; Lin, Y.; An, L.; Liu, D.; Pan, J.; Yu, X.; Chen, B.; Wu, T.; et al. Combination of CD19 and CD22 CAR-T Cell Therapy in Relapsed B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia after Allogeneic Transplantation. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Wu, Z.; Jia, H.; Tong, C.; Guo, Y.; Ti, D.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; et al. Bispecific CAR-T Cells Targeting Both CD19 and CD22 for Therapy of Adults with Relapsed or Refractory B Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Ding, L.; Shi, W.; Wan, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Song, L.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Co-Administration of CD19 and CD22 CAR-T Cells in Children with B-ALL Relapse after CD19 CAR-T Therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gust, J.; Hay, K.A.; Hanafi, L.-A.; Li, D.; Myerson, D.; Gonzalez-Cuyar, L.F.; Yeung, C.; Liles, W.C.; Wurfel, M.; Lopez, J.A.; et al. Endothelial Activation and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Neurotoxicity after Adoptive Immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T Cells. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1404–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Santomasso, B.D.; Locke, F.L.; Ghobadi, A.; Turtle, C.J.; Brudno, J.N.; Maus, M.V.; Park, J.H.; Mead, E.; Pavletic, S.; et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Tummala, S.; Kebriaei, P.; Wierda, W.; Gutierrez, C.; Locke, F.L.; Komanduri, K.V.; Lin, Y.; Jain, N.; Daver, N.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy - Assessment and Management of Toxicities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santomasso, B.D.; Park, J.H.; Salloum, D.; Riviere, I.; Flynn, J.; Mead, E.; Halton, E.; Wang, X.; Senechal, B.; Purdon, T.; et al. Clinical and Biological Correlates of Neurotoxicity Associated with CAR T-Cell Therapy in Patients with B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, D.B.; Danish, H.H.; Ali, A.B.; Li, K.; LaRose, S.; Monk, A.D.; Cote, D.J.; Spendley, L.; Kim, A.H.; Robertson, M.S.; et al. Neurological Toxicities Associated with Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. Brain 2019, 142, 1334–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudno, J.N.; Kochenderfer, J.N. Toxicities of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells: Recognition and Management. Blood 2016, 127, 3321–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grupp, S.A.; Kalos, M.; Barrett, D.; Aplenc, R.; Porter, D.L.; Rheingold, S.R.; Teachey, D.T.; Chew, A.; Hauck, B.; Wright, J.F.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells for Acute Lymphoid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, K.A.; Hanafi, L.-A.; Li, D.; Gust, J.; Liles, W.C.; Wurfel, M.M.; López, J.A.; Chen, J.; Chung, D.; Harju-Baker, S.; et al. Kinetics and Biomarkers of Severe Cytokine Release Syndrome after CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T-Cell Therapy. Blood 2017, 130, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Gardner, R.; Porter, D.L.; Louis, C.U.; Ahmed, N.; Jensen, M.; Grupp, S.A.; Mackall, C.L. Current Concepts in the Diagnosis and Management of Cytokine Release Syndrome. Blood 2014, 124, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teachey, D.T.; Lacey, S.F.; Shaw, P.A.; Melenhorst, J.J.; Maude, S.L.; Frey, N.; Pequignot, E.; Gonzalez, V.E.; Chen, F.; Finklestein, J.; et al. Identification of Predictive Biomarkers for Cytokine Release Syndrome after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karschnia, P.; Jordan, J.T.; Forst, D.A.; Arrillaga-Romany, I.C.; Batchelor, T.T.; Baehring, J.M.; Clement, N.F.; Gonzalez Castro, L.N.; Herlopian, A.; Maus, M.V.; et al. Clinical Presentation, Management, and Biomarkers of Neurotoxicity after Adoptive Immunotherapy with CAR T Cells. Blood 2019, 133, 2212–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, N.V.; Shaw, P.A.; Hexner, E.O.; Pequignot, E.; Gill, S.; Luger, S.M.; Mangan, J.K.; Loren, A.W.; Perl, A.E.; Maude, S.L.; et al. Optimizing Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy for Adults With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- & Hu, S. Overview of Immunosuppressive Therapy in Solid Organ Transplantation. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1975–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kruetzmann, S.; Rosado, M.M.; Weber, H.; Germing, U.; Tournilhac, O.; Peter, H.-H.; Berner, R.; Peters, A.; Boehm, T.; Plebani, A.; et al. Human Immunoglobulin M Memory B Cells Controlling Streptococcus Pneumoniae Infections Are Generated in the Spleen. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta S & Patel Approach to Immunodeficiency Diseases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 544–550.

- Author Index. Vox Sang. 2011, 101, 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Panitsas, F.P.; Theodoropoulou, M.; Kouraklis, A.; Karakantza, M.; Theodorou, G.L.; Zoumbos, N.C.; Maniatis, A.; Mouzaki, A. Adult Chronic Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) Is the Manifestation of a Type-1 Polarized Immune Response. Blood 2004, 103, 2645–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.J.; Bohlke, K.; Lyman, G.H.; Carson, K.R.; Crawford, J.; Cross, S.J.; Goldberg, J.M.; Khatcheressian, J.L.; Leighl, N.B.; Perkins, C.L.; et al. Recommendations for the Use of WBC Growth Factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3199–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turtle, C.J.; Hanafi, L.-A.; Berger, C.; Gooley, T.A.; Cherian, S.; Hudecek, M.; Sommermeyer, D.; Melville, K.; Pender, B.; Budiarto, T.M.; et al. CD19 CAR-T Cells of Defined CD4+:CD8+ Composition in Adult B Cell ALL Patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2016, 126, 2123–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penack, O.; Holler, E.; van den Brink, M.R.M. Graft-versus-Host Disease: Regulation by Microbe-Associated Molecules and Innate Immune Receptors. Blood 2010, 115, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malard, F.; Mohty, M. Updates in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease Management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 1637–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, S.; Slatter, M.; Skinner, R. Recent Advances in the Management of Graft-versus- Host Disease. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, S.; Zhong, D.; Xie, W.; Huang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y. Role of Toll-Like Receptor Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Graft-versus-Host Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, D.L.; Hwang, W.-T.; Frey, N.V.; Lacey, S.F.; Shaw, P.A.; Loren, A.W.; Bagg, A.; Marcucci, K.T.; Shen, A.; Gonzalez, V.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Persist and Induce Sustained Remissions in Relapsed Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 303ra139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster, S.J.; Bishop, M.R.; Tam, C.S.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munshi, N.C.; Anderson, L.D., Jr.; Shah, N.; et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Riviere, I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: foundation of a promising therapy. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2016, 3, 16015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- June, C.H.; O’Connor, R.S.; Kawalekar, O.U.; et al. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2018, 359, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maecker, H.T.; McCoy, J.P.; Nussenblatt, R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the Human Immunology Project. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012, 12, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Brand names | Company | Targets | References |

| Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) | Novartis | CD19 and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) |

[2] |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) | Gilead | CD19 and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) |

[4,5,6] |

| Brexucabtagene autoleucel (Tecartus) | Gilead | CD19 and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) |

[7,8] |

| Lisocabtagene maraleucel | Bristol Myers Squibb | CD19 and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) |

[9,10,11] |

| Idecabtagene vicleucel | Bristol Myers Squibb and Bluebird Bio |

CD19 and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) |

[1,12,13,14] |

| Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Carvykti) | Legend and Janssen | CD19 and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA) |

[15,16] |

|

Steps |

Process |

Reference |

|---|---|---|

| T Cell Collection | T cells are harvested from either the peripheral blood of patients or healthy donors. These T cells are isolated and prepared for their transformation. | [1,31] |

| Genetic Engineering |

CAR construction comprises of: Extracellular domain (scFv) that recognizes specific tumor surface antigens. Transmembrane Domain: Anchors the CAR in the cell membrane. Intracellular Signaling Domain: Transmits activation signals upon antigen recognition. |

[32,33] |

| Antigen Independence: | (i) CAR-T cells recognize tumor antigens independently of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) presentation. | [34] |

|

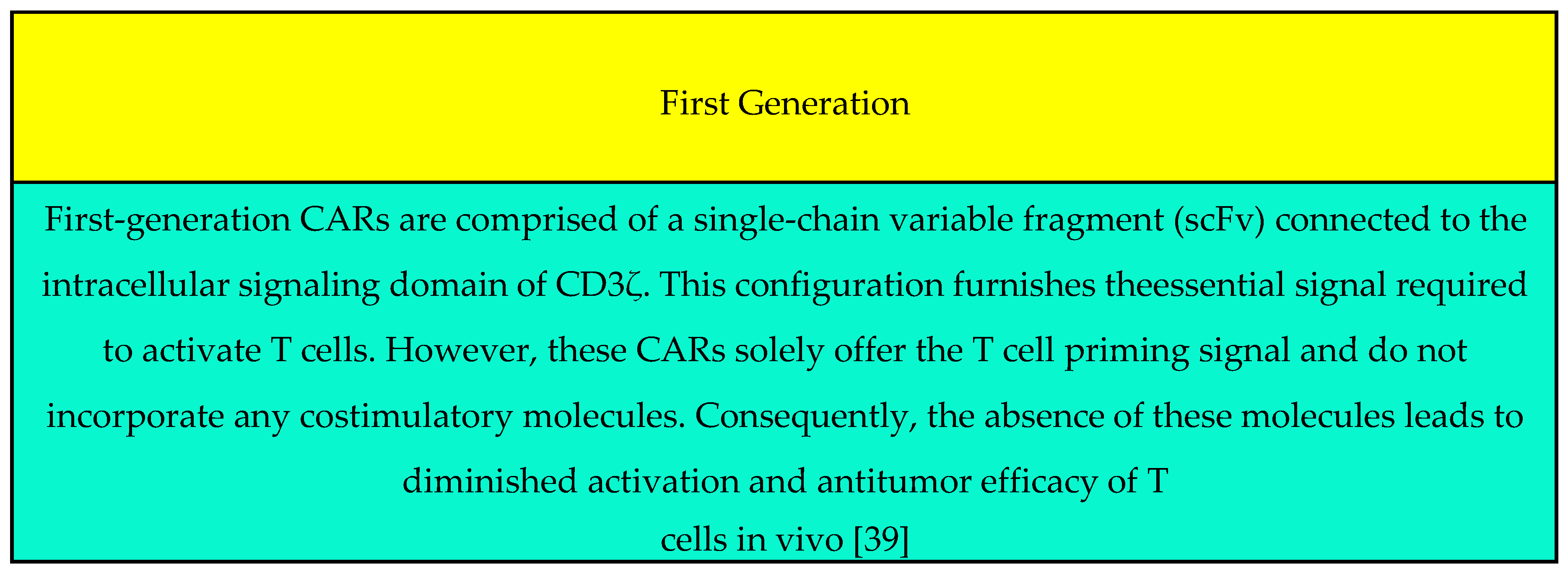

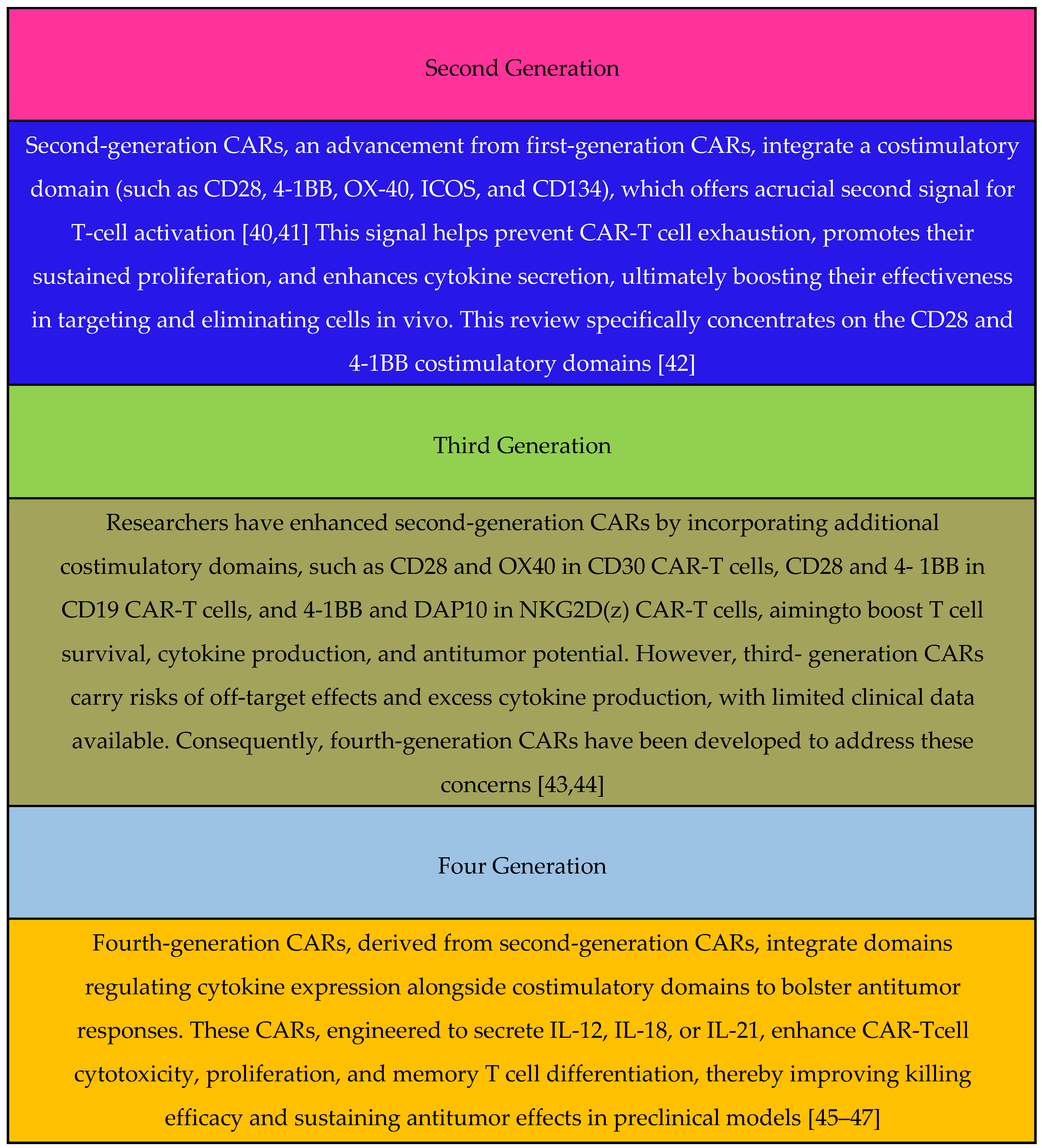

Generation: (It can be found in Figure 1) |

(ii) First-Generation CAR: Limited proliferative capacity due to lack of costimulatory signals. Second-Generation CAR: Enhanced proliferation and cytokine release. Third-Generation CAR: Combines distinct costimulatory molecules. |

[35,36] |

| “In vitro” Expansion | Cell Culturing: Modified T cells undergo extensive expansion in vitro. | [37] |

| Lymphodepletion |

Preparation: Patients receive lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Infusion: Genetically engineered CAR-T cells are re- infused into the patient. |

[1,38] |

| Target Recognition and Proliferation |

Deployment: CAR-T cells circulate in the patient’s bloodstream. Target Lock-On: CARs recognize specific antigens (often Tumor- Associated Antigens (TAAs). 1. Rapid Proliferation: Activated CAR-T cells multiply, mounting an anti-tumor assault. |

[4] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).