Introduction

CAR-T therapy has achieved considerable success in the treatment of hematologic tumors by using patient derived autologous T cells with αβTCR (αβ T cells). Although effective, the autologous setting of CAR-T cells has also highlighted the limitations of this therapy including (i) disease progression during manufacture (ii) T cell dysfunction of heavily pretreated patients, and (iii) logistical and cost constraints in individualized manufacturing processes 1. To alleviate these inadequacies, allogeneic CAR strategies have been actively developed using NK cells albeit with time-consuming cell expansion and difficulty in cryopreservation 2.

In human peripheral blood, αβ T cells constitute majority of T cells which are used as a source of current CAR-T cells. While T cells with Vγ9Vδ2 TCR (γδ T cells) constitute a small (2 -5 %) fraction of total T cells, they exhibit potent antitumor activity via release of inflammatory cytokines including IFN-γ that inhibit tumor growth and granzymes and perforin that directly kill tumors 3. Recognition by Vγ9Vδ2 TCR is independent of MHC but dependent on butyrophilin (BTN) 3A1/2A1 4,5 and this lack of MHC restriction makes γδ T cells highly unlikely to cause GVHD 6. It indeed has been shown that an adoptive transfer of allogeneic γδ T cells expanded from healthy donors exhibited a good safety profile in a patient with a solid tumor 7,8. Another possible advantage of γδ T cells as a source of CAR-T cells is that they recognize tumor cells through phosphoantigens highly expressed in tumor cells 9. It has been shown that expanded γδ T cells exert anti-tumor function, although modest-to-moderate, in early phase clinical trials 10, suggesting genetic modification with CAR expression provide more beneficial therapeutic effect. Moreover, γδ T cells can be easily expanded using nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (N-BPs) such as zoledronic acid 11 and cryopreserved without loss of immune cell functions 12. Taken together, γδ T cells appear to have potential as a source of allogeneic ‘off-the-shelf’ CAR-T cells 13. However, given the innate-like immune cell nature and effector-cell-like metabolic properties of γδ T cells in periphery 14, the persistence/survival and durability of anti-tumor function of CAR-modified Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in vivo remain a major concern.

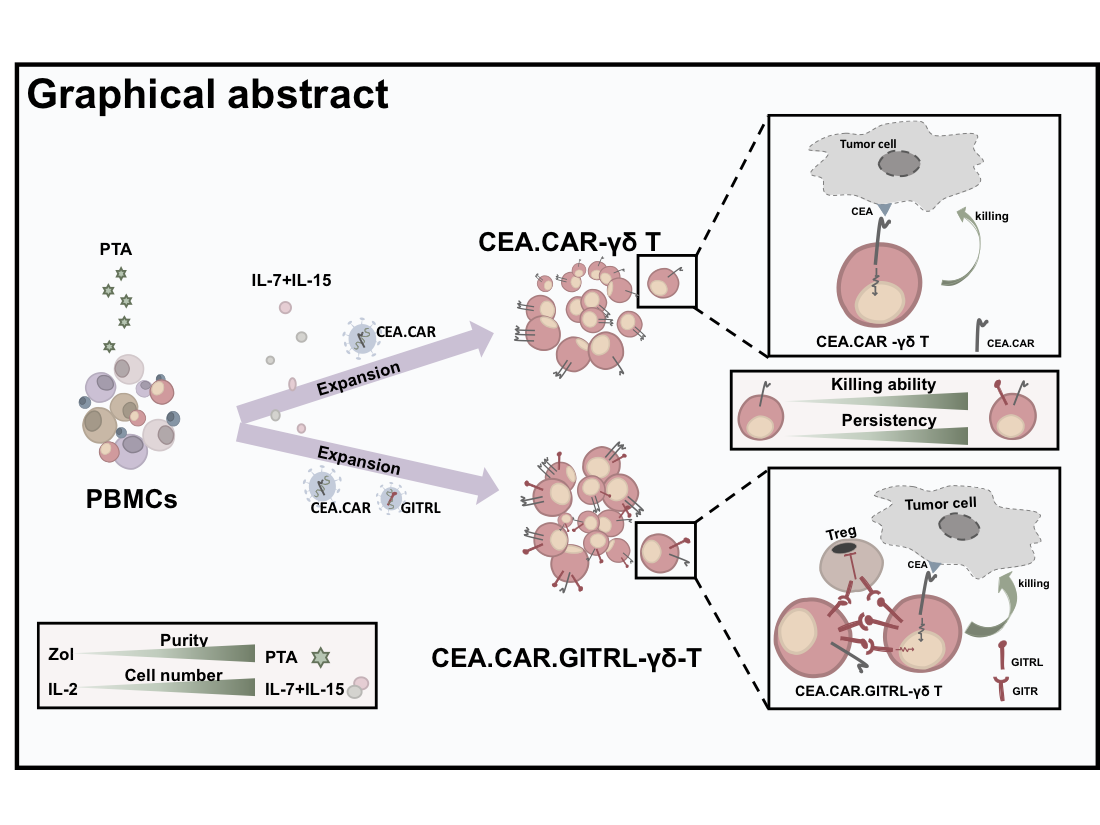

In the present study, using a novel N-BP prodrug, tetrakis-pivaloyloxymethyl 2-(thiazole-2-ylamino)ethylidene-1,1-bisphosphonate (PTA) which stimulates and propagate Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with high purity15, γδ T cells modified to express construct containing scFv specific to CEA and signaling domains of CD3ζ and CD28 were explored for their persistency, localization, phenotypic features, and tumor suppressive activity in a xenograft model using NOG mice.

Results

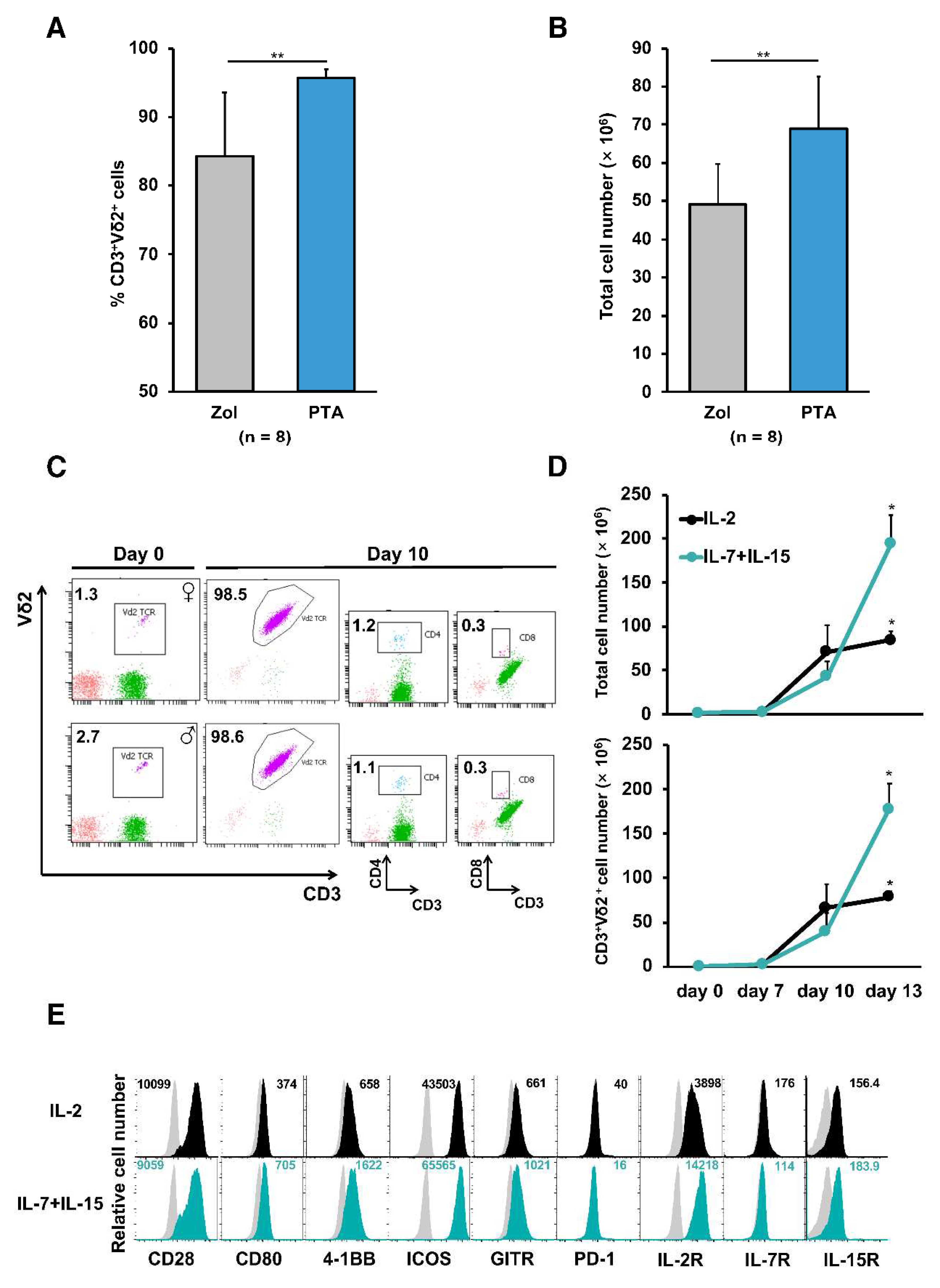

In order to obtain the sufficient number of γδ T cells with high purity, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were stimulated by a novel prodrug PTA or, as a reference, zoledronate (Zol) and cultured in the presence of IL-2. Consistent with results reported previously

15, PTA stimulation of PBMCs resulted in greater number of cells with higher percentage of CD3

+Vδ2

+ T cells when compared to Zol stimulation as previously reported

16 (

Figure 1A and B). These PTA-stimulated γδ T cell preparations contained quite a few CD4

+ or CD8

+ T cells responsible for GVHDs (

Figure 1C). It has been demonstrated that the combination of IL-7 and IL-15 mediate a faster and prolonger proliferation of αβ T cells

17. Therefore, we next compared the ability of IL-2 and IL-7 plus IL-15 to expand γδ T cells. PBMCs stimulated with PTA and cultured with IL-7 plus IL-15 yielded greater cell numbers as compared to IL-2 (

Figure 1D). γδ T cells expanded in the presence of IL-2 or IL-7 plus IL-15 expressed similar levels of costimulatory receptors such as CD28 and GITR (

Figure 1E).

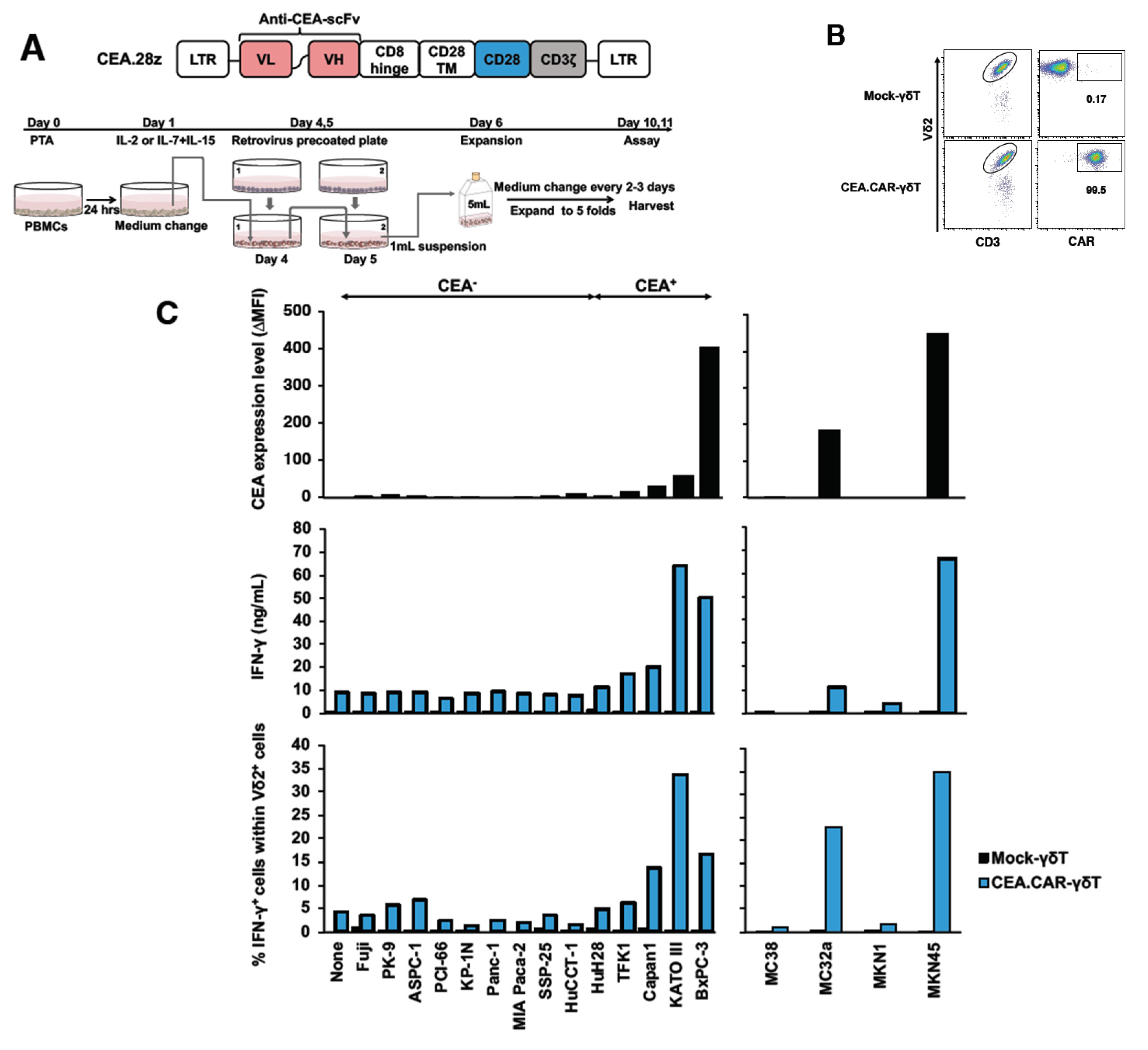

Having established an optimal condition for stimulation and expansion of γδ T cells, we next examined whether those γδ T cells can be transduced with CAR gene and express functional CAR. To this end, γδ T cells engineered to express a CAR composed of anti-CEA scFv F11-39 in the ectodomain and CD28 and CD3ζ signaling endodomains using retrovirus vectors (

Figure 2A)

18. We usually obtained more than 95% of Vδ2

+ cells expressing CAR (CEA.CAR-γδ T) (

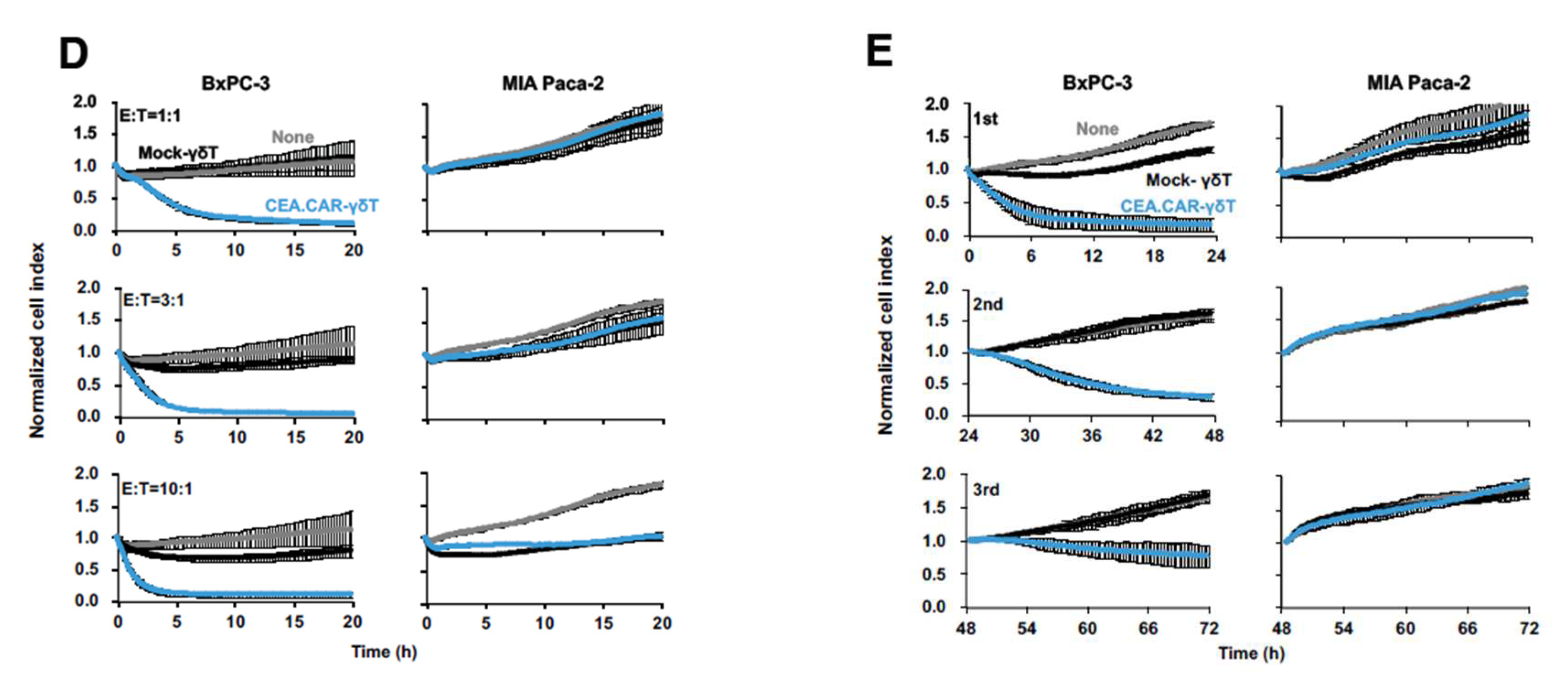

Figure 2B). These CEA.CAR-γδ T cells produced IFN-γ upon cocultured with tumors expressing various levels of CEA, but not cocultured with CEA

- tumors (

Figure 2C and

Figure S1), killed CEA

+ but not CEA

- tumors at various E:T ratios (

Figure 2D) and serially (

Figure 2E). Mock-transduced -γδ T cells (Mock-γδ T cells) did not respond to neither CEA

+ nor CEA

- tumors. It is noteworthy that CEA.CAR-γδ T cells produced IFN-γ upon incubation with CEA

+ (MC32a), but not CEA

- tumor (MC38) cell lines originated from mice, which do not express BTN3A1/2A1

19, indicating that CAR signaling solely, independent of γδ TCR, can induce activation of CEA.CAR-γδ T cells.

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of CEA.CAR-γδ T cells in vivo, we set up experiments where CEA.CAR-γδ T cells were transferred into NOG mice bearing 7-day-old tumor expressing CEA but not GD2 (BxPC-3) (

Figure 3A). It has been reported that CAR elicits ligand-independent constitutive signaling (tonic signaling) albeit varying levels that induces T cell exhaustion

20 but may also contribute to γδ T cells to control tumor growth, therefore, γδ T cells expressing functional but irrelevant (GD2 specific) CAR (GD2.CAR-γδ T cells) (

Figure S2) also served as a control. As shown in

Figure 3B, CEA.CAR-γδ T cells, but not Mock-γδ T cells nor GD2.CAR-γδT cells, suppressed growth of BxPC-3 tumor. The infusion of these γδ T cell preparations did not induce weight loss. In a clinical situation, patients often receive lymphodepletion or myeloablative lymphodepletion prior to CAR-T cell infusion to improve clinical efficacy and/or delay graft rejection in an autologous and allogeneic setting

21,22. Immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice were treated with fludarabine (Flud), cyclophosphamide (CY) and total body irradiation (TBI) (

Figure S3A) to confirm lymphodepletion (

Figure S3B). Then CEA.CAR-γδ T cells were transferred into 8-day-old CEA

+ tumor (MC32a)-bearing C57BL/6 mice that received the treatment (

Figure S3C), we found that CEA.CAR-γδ T cells, but not Mock-γδ T cells, suppressed tumor growth (

Figure S3D). In tumor-bearing NOG mice, CEA.CAR-γδ T cells gradually reduced in the periphery but gradually accumulated in the tumor (

Figure 4). This accumulation of CEA.CAR-γδ T cells in the tumor appeared antigen-dependent since CEA.CAR-γδ T cells but not GD2.CAR-γδ T cells nor Mock-γδ T cells accumulated in the tumors (

Figure 4A and

Figure S4). We also investigated the expressions of co-inhibitory receptors on γδ T cells in mice bearing CEA

+ tumors (

Figure S5). We found that γδ T cells irrespective of CAR transduction expressed Tim-3 and LAG-3, which declined gradually over time. It was noted that CEA.CAR-γδ T cells in tumor tissues, but not CEA.CAR-γδ T cells from other tissues nor Mock-γδ T cells from all tissues examined, expressed PD-1 at a later time point. The tumor used in this experiment expressed PD-L1 in vitro and in vivo (

Figure S6).

To determine durability of these CEA.CAR-γδ T cells to maintain tumor reactivity, single cell suspension of PBMCs, spleen and tumor tissues were cultured in the presence of CEA

+ (BxPC-3) or CEA

- (MIA Paca-2) tumors and Vδ2

+ cells were analyzed for IFN-γ production by ICS. As shown in

Figure 5, transferred CEA.CAR-γδ T cells, irrespective of whether collected from peripheral blood (as PBMCs), spleen, or tumor tissues (as tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)), rapidly lost ability to produce IFN-γ upon coculture with CEA

+ tumor cells (BxPC-3). CEA.CAR expression on γδ T cells from PBMC remained unchanged by day 20 (

Figure S7). It is noteworthy that those CEA.CAR-γδ T cells largely retained ability to produce IFN-γ upon stimulation with PMA plus ionomycin.

As such CEA.CAR-γδ T cells do not completely lose functionality, we sought to determine whether an additional costimulatory signal may improve CAR-γδ T cell functions in vivo. We employed GITR signaling that provides potent costimulation and may synergize with CD28 signaling for T cell activation

23. To this end, we transduced a gene encoding a ligand for GITR (GIRTL) to deliver a signal through GITR in addition to CAR to γδ T cells (CEA.CAR.GITRL-γδ T cells). GITR expression was confirmed to be expressed on expanded γδ T cells (

Figure 1E). Both genes were successfully transduced in γδ T cells and expressed on the cell surface of γδ T cells (

Figure 6A). Co-expression of GITRL significantly enhanced expression of IFN-γ and CD107a, and serial killing function upon coculture with CEA

+ tumors (

Figure 6B and C). Then we compared the ability of CEA.CAR-γδ T cells and those co-expressing GITRL to control tumor growth in NOG mice bearing 11-day-old CEA

+ tumor. As shown in

Figure 6D, co-expression of GITRL on CEA.CAR-γδ T cells enhanced tumor suppression concomitant with increased infiltration into the tumor and retention in periphery (

Figure 6E and F).

Discussion

Potent tumor killing function 3, lack of allogenicity 5-7, simplicity of expansion 11 and cryopreservation without loss of functionality 12 make γδ T cells an excellent candidate as a source of allogeneic “off-the-shelf” CAR-T cells. Attempts of CAR transduction into γδ T cells expanded using zoledronate have been reported 24-26, but the purities of γδ T cell population do not seem sufficient that required further purification before application. In the present study, we demonstrated that γδ T cells stimulated with a novel prodrug PTA 15 achieved greater expansion with high purity as compared to those stimulated with other reagents 16,27. Typically, PBMCs stimulated with PTA resulted in the cell population containing ~1.5% CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as compared to ~ 19% CD8+ T cells in zoledronate 16 and 2.7-10.7% CD8+ T cells in isopentenyl pyrophosphate 27. Our results indicate that PTA offers a great opportunity of obtaining a γδ T cell preparation with least contamination of αβ T cells that cause GVHDs in an allogeneic setting.

As a proof of concept, we employed a second generation CD28 and CD3ζ endodomain-containing CAR and CEA as a target antigen with a favorable expression profile including limited normal tissue expression and broad expression on many solid tumors 28,29, in which safety and efficacy have been confirmed using CEA-transgenic mice transferred with CEA-specific CAR-αβ T cells in our previous study 18 . We could successfully transduce these γδ T cells with CAR in a highly efficient manner without loss of viability. Using the same virus vectors, we have experienced lower transduction efficiency in αβ T cells stimulated anti-CD3 that resulted in ~66 % CAR+ cells. Previous studies reported by other groups using Zol stimulated γδ T cells also showed lower efficiency in transduction 24-26 (<60% CAR+). Although these differences in transduction efficiency may be attributable to the difference in multiplicity of infection (MOI; 18.5 or 28.5 in this study), it may be possible that higher replication rate of γδ T cells induced by PTA contributed to this transduction efficiency and one of the advantages of using PTA in a γδ T cell preparation.

CEA-specific CAR-γδ T cells respond to various tumor cell lines expressing different levels of CEA even in the absence of signals through γδ TCR and kill tumor cells in a CEA dependent manner. Although it has been reported that serial killing by CAR-γδ T cells was rarely observed and never been demonstrated directly 30,31, we could demonstrate that CEA.CAR-γδ T cells kill tumor serially, an important feature of T cells with efficient tumor control capability 32-35.

While Themeli et al. 36 demonstrated CAR-γδ T cells almost completely eradicated tumors in an intraperitoneal Rai tumor model, we could not show complete eradication of tumors, which is consistent to others 26,37. In our study, CEA.CAR-γδ T cells seemed to rapidly lose abilities to control tumors, since transferred CEA.CAR-γδ T cells recovered from tumor-bearing mouse rapidly become unresponsive to tumor. Roszenbaum et al. proposed that the restricted ability to control tumors by CAR-γδ T cells was due to limited persistence of CAR-γδ T cells and demonstrated that repeated infusion of the CAR-γδ T cells improved anti-tumor effects 26. However, our results clearly demonstrate that CEA.CAR-γδ T cells accumulated and retained in tumors as assessed by fluorescence IHC staining and flow cytometry with using anti-Vδ2 and/or anti-human CD45 mAbs.

It has been reported that CAR expression on αβ T cells within tumor tissues often eluded the detection by conventional flow cytometry due to the rapid downmodulation and subsequent degradation within the cells upon ligand recognition 38,39, accordingly we could not demonstrate CAR expression on γδ T cells within tumors. Although the proper downmodulation of CAR upon ligand binding has been suggested to be required for optimal function of CAR-T cell with αβ TCR 40, recent study has demonstrated that the downregulation of CAR is responsible for the limited CAR-αβ T cell functions in lymphoma and solid tumor models 38,41. However, sustained CAR expression was observed on Vδ2+ cells in PBMC by up to 20 days after the transfer and become unresponsive to tumors, indicating that the loss of CAR expression does not solely account for unresponsiveness of CAR-γδ T cells to tumors.

Although tumors employed in this study express PD-L1 in vivo and in vitro (

Figure S6), it is unlikely that co-inhibitory molecules, such as CTLA-4 and PD-1, was involved in suppression of T cell function in TME

42, since CTLA-4 was not expressed on CEA.CAR-γδ T cells and PD-1 was expressed only at quite later time points after the transfer. Furthermore, it has been shown that ex vivo expanded γδ T cells are relatively resistant to PD-1 mediated suppression

43. Expression of Tim-3 and LAG-3, which also play an immunosuppressive role in TME

44, was higher in earlier time points and rapidly decreased at later time points when CEA.CAR-γδ T cells became unresponsive to tumors. Taken altogether, these results suggest that the loss of function of CEA.CAR-γδ T cells are not due to limited persistency of infused CEA.CAR-γδ T cells nor loss of CAR expression. Furthermore, immunosuppressive mechanisms in TME may not play a dominant role in the unresponsiveness of CEA.CAR-γδ T cells to tumors.

It has been shown that ligation of GITR delivers a potent costimulatory signal to T cells including γδ T cells 23,45. Furthermore, not only αβ T cells but also γδ T cells are sensitive to regulatory T cell mediated suppression 45 which is inhibited by GITR signaling induced in regulatory T cells 46-48. In the present study, instead of incorporating GITR signaling domain in CAR construct (3rd generation CAR), γδ T cells were co-transduced with CAR consisting CD3ζ and CD28 signaling domain together with a ligand for GITR. This strategy allows GITRL to deliver a GITR signal in CEA.CAR-γδ T cells and also regulatory T cells abundant in tumor microenvironment to inhibit their suppressive function, the latter possibility of which has not been addressed in the present study. Forced expression of GITR ligand on CEA.CAR-γδ T cells enhanced IFN-γ production and serial killing function in vitro and improved in vivo anti-tumor activity associated with increased accumulation in the tumor and enhanced persistency in the periphery. The underlying mechanisms by which GITR signaling enhances CEA.CAR-γδ T cell function remain to be elucidated but may involve metabolic changes that support effector functions. 49 It is also possible that GITR signaling promotes CAR-γδ T cells, like αβ T cells 49, to differentiate central memory T cells that maintain effector functions.

In conclusion, while further optimization is necessary, the present results demonstrate a potential of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells as a source of ‘off-the-shelf’ CAR-T cell products. The optimization will inevitably include the incorporation of additional measures to ensure their functionality in vivo.

Materials and Methods

NOD/Shi-scid/IL-2Rγnull mice, known as NOG mice, and C57BL/6NcrSlc mice were purchased from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Kawasaki, Japan) and Japan SLC Inc (Shizuoka, Japan), respectively. Mice were fed a standard diet, housed under specific pathogen free conditions, and used at 6 – 8 weeks of age. All animal experiments were conducted under protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Mie University Life Science Center.

The following antibodies and regents were used for cells surface and intracellular staining; FITC-anti-human TCR Vδ2 (Clone: B6), APC-anti-human TCR Vδ2 (Clone: B6), PE-anti-human CD28 (Clone: CD28.2), PE-anti-human GITR (Clone: 621), PE-anti-human CD25 (IL-2R) (Clone: M-A251), PE-anti-human CD127 (IL-7R) (Clone: A019D5), APC-anti-human CD215 (IL-15Rα) (Clone: JM7A4), PE-anti-human CD137 (4-1BB) (Clone: 4B4-1), APC-anti-human CD279 (PD-1) (Clone: EH12.2H7), PE-anti-human CD278 (ICOS) (Clone:C398.4A), PE/Cyanine 7-anti-human CD45RA (Clone: HT100), and as isotype controls, FITC-human IgG1 isotype control (Clone:QA16A12), APC-mouse IgG1, κ (Clone: MOPC-21), PE-mouse IgG1, κ (Clone: MOPC-21), FITC-mouse IgG1, κ, (Clone: MOPC-21), PerCP/Cy5.5-mouse IgG1, κ (Clone: MOPC-21) PE-mouse IgG2a, k, isotype control (Clone: MOPC-173) were from BioLegend; V450-anti-human CD3 (Clone: UCHT1), V500-anti-human CD8 (Clone: RPA-T8), APC-anti-human CD4 (Clone: RPA-T4), V450-anti-human CD45 (Clone: HI30), PE-anti-human CD45 (Clone: HI30) and APC-anti-human CD107a (Clone: H4A3) and Golgi Stop were from BD biosciences; FITC-anti-human CD62L (Clone: DREG-56), PE/Cyanine 7-anti-human CD45RA (Clone: HI100), eFlour 450-anti-IFNγ (Clone: 4S.B3), Alexa488 anti-rabbit IgG, and FITC-anti-Ki67 (Clone: SolA15) were from Invitrogen; FITC-anti-CD66e (CEA) (Clone: REA876) was from Miltenyi Biotec; PE-anti-human GD2 (Clone:14G2a) was from Santa Cruz; PE-conjugated-GITR Ligand (Clone: 109101), Streptavidin APC-conjugated and Streptavidin PE-conjugated were from R&D Systems. Goat-anti-human IgG kappa LC, purchased from MBL. Zoledronate was purchased from NOVARTIS. Tetrakis-pivaloyloxymethyl 2-(thiazole-2-ylamino)ethylidene-1,1-bisophosphohonate (PTA) was synthesized as described 50 and dissolved in DMSO 11. A final working solution of PTA contained 0.1% DMSO. Modified Yessel’s medium was prepared in house with 35.34 g of IMDM (Gibco) 6.048 g of NaHCO3, 200 mL of human AB serum (Gemcell), 4 mL of 2-aminoethanol (Nacalai Tesque) in PBS, 80 mg of apo-transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mL of 1 mg/mL human insulin (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 0.01N HCl, 200 μl of fatty acid mixture containing 4 mg of linoleic acid, 4 mg of oleic acid and 4 mg of palmitic acid in ethanol (all from Sigma-Aldrich), and 20 mL of penicillin/streptomycin solution (Gibco) in 2 L distilled water (MiliQ). After sterilization with 0.22 μm filter, the medium was kept at -20°C until use.

CAR construct consisting of a sequence identical to a scFv of mAb F11-39 specific to CEA in the VL-VH orientation along with a CD8α hinge, CD28 transmembrane domain, plus CD28 and CD3ζ signaling domains were prepared as described 18 except CD8, CD28, and CD3ζ sequences were replaced with human sequences. A scFv derived from mAb 220-51 51 was replaced with that from mAb F11-39 in a GD2-specific CAR construct. Construct for GITR ligand contains a sequence of full length human GITR ligand cloned into a pMS3 retroviral vector using Not I and Xho I double digestion sites. The murine stem cell virus LTR was used to drive CAR expression. Virus solutions were obtained as described 52. Briefly, after transduction into 293T cells (ATCC CRL-3216) with a Retrovirus Packaging Kit Eco (#6160; Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), the cell culture supernatant was used to transduce PG13 cells ((ATCC CRL-10686)). PG13 cells were transduced with transiently produced ecotropic retroviruses to produce GaLV-pseudotyped retroviruses.

Stimulation and expansion of Vγ9Vδ2 TCR T cells were conducted as described with a slight modification15. Briefly, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy adult donors were obtained by density gradient separation (Ficoll-RaqueTM Plus, Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were then plated at 1.5×106 cells/1.5 mL in a well of 24-well plate in YM-AB medium with 1μM PTA. After 24 hours, the medium was replaced YM-AB medium with additional supplementation of 300 IU/mL of IL-2 (NOVARTIS) or 25 ng/mL of IL-7 (BioLegend) plus 25 ng/mL of IL-15 (BioLegend) and subsequently expanded to 2 to 5-fold with fresh medium containing IL-2 or IL-7 plus IL-15 at every 2-3 days.

Transduction of γδ T cells with the viral vector was conducted using the RetroNectin-bound virus infection method, wherein virus solutions were preloaded onto Retro-Nectin (#T100A; Takara Bio)-coated wells of a 24-well plate containing 1-mL culture medium as described 53. Briefly, day 4 and 5 of γδ T cells in stimulation/expansion culture as above were retrovirally transduced with CAR together with or without GITRL at MOI of 18.5 or 28.5. On day 6, cells were transferred into a T25 Flask with 5 mL YM-AB medium containing IL-7 (25 ng/mL) plus IL-15(25 ng/mL) and subsequently expanded to 2 to 5-fold at every 2-3 days. CAR expression was determined by staining with biotinylated CEA prepared in house using biotin-labelling kit-NH2 (DOJIN, Japan).

Murine colon carcinoma MC38 cells and MC38 cells expressing human CEA (designated MC32a), human pancreatic tumor cell lines BxPC-3, PK9, ASPC1, PCI-66 KP-1N, Panc-1, Capan1, MIA Paca-2, human biliary duct tumor cell lines SSP-25, HuCCT-1, HuH28, TFK1, human gastric tumor cell lines Kato III, MKN45, MKN1,and human periosteal sarcoma Fuji were cultured in RPMI-1640 (WAKO, Japan) supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 10% FCS (Biowest), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Cytokine production was analyzed using intracellular cytokine flow cytometry (ICS) or ELISA as previously described

52. Briefly, CEA.CAR-γδ T cells (2 × 10

5 cells/0.2 ml/well) were co-cultured with tumor cells (2 × 10

5 cells/0.2 ml/well) in a well of 96-well plate for 6 hours in ICS and 24 hours in ELISA using a kit for IFN-γ (Invitrogen). Long-term cytotoxicity was measured using the xCELLigence (ACEA Bioscience) impedance-based assay. Briefly, tumor cells were seeded at 7000 cells/well of a 96-well E-Plate (ACEA Bioscience) and allowed to grow for 18-20 hours. CEA.CAR-γδ T cells were then added at various E/T ratios and tumor growth or death as indicated by cell index was monitored up to 72 – 96 hours. Serial killing activity of CEA.CAR-γδ T cells was also assessed by the xCELLigence. Briefly, tumor cells were seeded at 7000, 3500 and 1750 cells/well for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd round co-culture, respectively, and allowed for growth for 18-20 hours. Then CEA.CAR-γδ T cells were added at 7000 cells/well and co-cultured for 24 hours (initial co-culture). CEA.CAR-γδ T cells from the initial co-cultures were serially transferred to a new well with previously seeded tumor cells at 24-hour interval for subsequent rounds of killing (2nd and 3rd) (

Figure S8.).

NOG mice were inoculated s.c. with MIA Paca-2 or BxPC-3 (4 - 5 × 106 cells) on day 0 followed by i.v. injection with CEACAR-γδ T cells or mock transduced γδ T cells (5 – 10 × 106 cells) on day 7 or day 11. Tumor areas were measured by a caliper using the formula (length × width) at the indicated time points.

Blood, spleen and tumor tissues from NOG mice (n = 4) transferred with CEA.CAR-γδ T cells were collected. PBMCs were separated by Ficoll (Ficoll-Paque PLUS, Sigma-Aldrich). ACK lysing buffer was used for lysis of red blood cells in spleen cells. Tumor tissues were minced in 10 mL HBSS containing 10 mg/ml of collagenase (BioRAD), incubated at 37°C for 30 min with frequent mixing and filtered through pre-wet 40 µm strainer. Single cell suspensions at 2 × 106 cells/mL for PBMCs, 2-8 × 106 cells/mL for spleens, and 0.3 - 3 × 106 cells/mL for tumor tissues were cocultured with BxPC-3 or MIA Paca-2 (2 × 106/mL) and subjected for IFN-γ ICS after gating on Vδ2+ cells.

Snap frozen tumor tissues were embedded in OCT compound (SAKURA), and stored at -80°C until they were sectioned at 3 µm thickness. All sections were stained with fluorescent dye-conjugated anti-CD45, anti-PD-L1 and/or anti-cytokeratin and DAPI. A fluorescence microscope BX53 (Olympus) mounted with DP73 camera (Olympus) was used for imaging of fluorescence IHC staining.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD where error bars are shown. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests using Microsoft Excel. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experiments were conducted more than two times and one of the representative results is shown.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Y.W., L.W., N.S., S.O., T.H., H.F., and K.S. conducted the experiments and analyzed the results; Y.K., Y.T., Y.A., S.O., and J.M. provided reagents; T.K. and H.S. conceived the study; T.K. supervised the work, interpreted data, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 20K07674 to T.K. and 19K09195 to L.W.. The authors thank Miss. Kazuko Shirakura and Miss. Chisaki Hyuga for their skilled technical assistance. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Roddie, C.; O'Reilly, M.; Pinto, J.D.A.; Vispute, K.; Lowdell, M. Manufacturing chimeric antigen receptor T cells: issues and challenges. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingemann, H. Challenges of cancer therapy with natural killer cells. Cytotherapy 2015, 17, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, E.; Bocca, P.; Emionite, L.; Cilli, M.; Cipollone, G.; Morandi, F.; Raffaghello, L.; Pistoia, V.; Prigione, I. Mechanisms of the Antitumor Activity of Human Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells in Combination With Zoledronic Acid in a Preclinical Model of Neuroblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigau, M.; Ostrouska, S.; Fulford, T.S.; Johnson, D.N.; Woods, K.; Ruan, Z.; McWilliam, H.E.; Hudson, C.; Tutuka, C.; Wheatley, A.K.; et al. Butyrophilin 2A1 is essential for phosphoantigen reactivity by γδ T cells. Science 2020, 367, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, A.; Peigné, C.-M.; Léger, A.; Crooks, J.E.; Konczak, F.; Gesnel, M.-C.; Breathnach, R.; Bonneville, M.; Scotet, E.; Adams, E.J. The Intracellular B30.2 Domain of Butyrophilin 3A1 Binds Phosphoantigens to Mediate Activation of Human Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells. Immunity 2014, 40, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, I.; Bertaina, A.; Prigione, I.; Zorzoli, A.; Pagliara, D.; Cocco, C.; Meazza, R.; Loiacono, F.; Lucarelli, B.; Bernardo, M.E.; et al. γδ T-cell reconstitution after HLA-haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation depleted of TCR-αβ+/CD19+ lymphocytes. Blood 2015, 125, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaggar, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Li, M.; Wu, Q.; Lin, L.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Allogenic Vγ9Vδ2 T cell as new potential immunotherapy drug for solid tumor: a case study for cholangiocarcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Alnaggar, M.; Kouakanou, L.; Li, J.; He, J.; Yang, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lin, L.; et al. Allogeneic Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell immunotherapy exhibits promising clinical safety and prolongs the survival of patients with late-stage lung or liver cancer. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gober, H.-J.; Kistowska, M.; Angman, L.; Jenö, P.; Mori, L.; De Libero, G. Human T Cell Receptor γδ Cells Recognize Endogenous Mevalonate Metabolites in Tumor Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniger, D.C.; Moyes, J.S.; Cooper, L.J.N. Clinical Applications of Gamma Delta T Cells with Multivalent Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Cancer immunotherapy harnessing γδ T cells and programmed death-1. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 298, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Tay, J.C.; Zhang, X.; Zha, S.; Zeng, J.; Tan, W.K.; Liu, X.; et al. Large-scale expansion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with engineered K562 feeder cells in G-Rex vessels and their use as chimeric antigen receptor–modified effector cells. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depil, S.; Duchateau, P.; Grupp, S.A.; Mufti, G.; Poirot, L. ‘Off-the-shelf’ allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneville, M.; O'Brien, R.L.; Born, W.K. γδ T cell effector functions: a blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Murata-Hirai, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Hayashi, K.; Kumagai, A.; Nada, M.H.; Wang, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Kamitakahara, H.; et al. Expansion of human γδ T cells for adoptive immunotherapy using a bisphosphonate prodrug. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Sakuta, K.; Noguchi, A.; Ariyoshi, N.; Sato, K.; Sato, S.; Hosoi, A.; Nakajima, J.; Yoshida, Y.; Shiraishi, K.; et al. Zoledronate facilitates large-scale ex vivo expansion of functional γδ T cells from cancer patients for use in adoptive immunotherapy*. Cytotherapy 2008, 10, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieri, N.; Camisa, B.; Cocchiarella, F.; Forcato, M.; Oliveira, G.; Provasi, E.; Bondanza, A.; Bordignon, C.; Peccatori, J.; Ciceri, F.; et al. IL-7 and IL-15 instruct the generation of human memory stem T cells from naive precursors. Blood 2013, 121, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ma, N.; Okamoto, S.; Amaishi, Y.; Sato, E.; Seo, N.; Mineno, J.; Takesako, K.; Kato, T.; Shiku, H. Efficient tumor regression by adoptively transferred CEA-specific CAR-T cells associated with symptoms of mild cytokine release syndrome. OncoImmunology 2016, 5, e1211218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, M.M.; Willcox, C.R.; Salim, M.; Paletta, D.; Fichtner, A.S.; Noll, A.; Starick, L.; Nöhren, A.; Begley, C.R.; Berwick, K.A.; et al. Butyrophilin-2A1 Directly Binds Germline-Encoded Regions of the Vγ9Vδ2 TCR and Is Essential for Phosphoantigen Sensing. Immunity 2020, 52, 487–498e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Hackett, C.S.; Brentjens, R.J. Engineering strategies to overcome the current roadblocks in CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, D.M.; Grupp, S.A.; June, C.H. Chimeric Antigen Receptor– and TCR-Modified T Cells Enter Main Street and Wall Street. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.-L.; Huang, Y.; Liang, X.; Jiang, L.; Yang, X.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Han, W.-D.; et al. Genetically engineered T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraehenbuehl, L.; Weng, C.-H.; Eghbali, S.; Wolchok, J.D.; Merghoub, T. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging immunomodulatory pathways. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischer, M.; Pscherer, S.; Duwe, S.; Vormoor, J.; Jürgens, H.; Rossig, C. Human γδ T cells as mediators of chimaeric-receptor redirected anti-tumour immunity. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 126, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capsomidis, A.; Benthall, G.; Van Acker, H.H.; Fisher, J.; Kramer, A.M.; Abeln, Z.; Majani, Y.; Gileadi, T.; Wallace, R.; Gustafsson, K.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered Human Gamma Delta T Cells: Enhanced Cytotoxicity with Retention of Cross Presentation. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenbaum, M.; Meir, A.; Aharony, Y.; Itzhaki, O.; Schachter, J.; Bank, I.; Jacoby, E.; Besser, M.J. Gamma-Delta CAR-T Cells Show CAR-Directed and Independent Activity Against Leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wen, Q.; He, W.; Yang, J.; Zhou, C.; Xiong, W.; Ma, L. Optimized protocols for γδ T cell expansion and lentiviral transduction. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nap, M.; Mollgard, K.; Burtin, P.; Fleuren, G.J. Immunohistochemistry of Carcino-Embryonic Antigen in the Embryo, Fetus and Adult. Tumor Biol. 1988, 9, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Deng, X.; Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Ahram, M.; Sloane, B.F.; Friedman, E. Oncogenic c-Ki-ras but Not Oncogenic c-Ha-ras Up-regulates CEA Expression and Disrupts Basolateral Polarity in Colon Epithelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 27902–27907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertner, J.; Wiedemann, A.; Poupot, M.; Fournié, J.-J. Human γδ T lymphocytes strip and kill tumor cells simultaneously. Immunol. Lett. 2007, 110, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, R.; Chennupati, V.; Ramachandran, B.; Hansen, M.R.; Singh, S.; Grewal, I.S. Selective recruitment of γδ T cells by a bispecific antibody for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2274–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaaz, S.; Baetz, K.; Olsen, K.; Podack, E.; Griffiths, G.M. Serial killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes: T cell receptor triggers degranulation, re-filling of the lytic granules and secretion of lytic proteins via a non-granule pathway. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995, 25, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, P.; Hofmeister, R.; Brischwein, K.; Brandl, C.; Crommer, S.; Bargou, R.; Itin, C.; Prang, N.; Baeuerle, P.A. Serial killing of tumor cells by cytotoxic T cells redirected with a CD19-/CD3-bispecific single-chain antibody construct. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 115, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regoes, R.R.; Yates, A.; Antia, R. Mathematical models of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte killing. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007, 85, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganusov, V.V.; De Boer, R.J. Estimating In Vivo Death Rates of Targets due to CD8 T-Cell-Mediated Killing. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11749–11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themeli, M.; Kloss, C.C.; Ciriello, G.; Fedorov, V.D.; Perna, F.; Gonen, M.; Sadelain, M. Generation of tumor-targeted human T lymphocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells for cancer therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniger, D.C.; Switzer, K.; Mi, T.; Maiti, S.; Hurton, L.; Singh, H.; Huls, H.; Olivares, S.; A Lee, D.; E Champlin, R.; et al. Bispecific T-cells Expressing Polyclonal Repertoire of Endogenous γδ T-cell Receptors and Introduced CD19-specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Qiu, S.; Chen, J.; Jiang, S.; Chen, W.; Jiang, J.; Wang, F.; Si, W.; Shu, Y.; Wei, P.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Designed to Prevent Ubiquitination and Downregulation Showed Durable Antitumor Efficacy. Immunity 2020, 53, 456–470e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Sim, S.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Singh, R.; Hwang, S.; Kim, Y.I.; Park, S.H.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, D.G.; Oh, H.S.; et al. Desensitized chimeric antigen receptor T cells selectively recognize target cells with enhanced antigen expression. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyquem, J.; Mansilla-Soto, J.; Giavridis, T.; van der Stegen, S.J.C.; Hamieh, M.; Cunanan, K.M.; Odak, A.; Gönen, M.; Sadelain, M. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature 2017, 543, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.J.; Majzner, R.G.; Zhang, L.; Wanhainen, K.; Long, A.H.; Nguyen, S.M.; Lopomo, P.; Vigny, M.; Fry, T.J.; Orentas, R.J.; et al. Tumor Antigen and Receptor Densities Regulate Efficacy of a Chimeric Antigen Receptor Targeting Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 2189–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, D.H.; Bronte, V. Immune suppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomogane, M.; Sano, Y.; Shimizu, D.; Shimizu, T.; Miyashita, M.; Toda, Y.; Hosogi, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Kimura, S.; Ashihara, E. Human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells exert anti-tumor activity independently of PD-L1 expression in tumor cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 573, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.C.; Joller, N.; Kuchroo, V.K. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-inhibitory Receptors with Specialized Functions in Immune Regulation. Immunity 2016, 44, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Sousa, N.; Ribot, J.C.; Debarros, A.; Correia, D.V.; Caramalho. ; Silva-Santos, B. Inhibition of murine γδ lymphocyte expansion and effector function by regulatory αβ T cells is cell-contact-dependent and sensitive to GITR modulation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 40, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, J.; Nishikawa, H.; Muraoka, D.; Wang, L.; Noguchi, T.; Sato, E.; Kondo, S.; Allison, J.P.; Sakaguchi, S.; Old, L.J.; et al. Two Distinct Mechanisms of Augmented Antitumor Activity by Modulation of Immunostimulatory/Inhibitory Signals. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 2781–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Kato, T.; Hirayama, M.; Orito, Y.; Sato, E.; Harada, N.; Gnjatic, S.; Old, L.J.; Shiku, H. Regulatory T Cell–Resistant CD8+ T Cells Induced by Glucocorticoid-Induced Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Signaling. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 5948–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza-Gonzalez, A.; Zhou, G.; Singh, S.P.; Boor, P.P.; Pan, Q.; Grunhagen, D.; de Jonge, J.; Tran, T.K.; Verhoef, C.; Ijzermans, J.N.; et al. GITR engagement in combination with CTLA-4 blockade completely abrogates immunosuppression mediated by human liver tumor-derived regulatory T cellsex vivo. OncoImmunology 2015, 4, e1051297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabharwal, S.S.; Rosen, D.B.; Grein, J.; Tedesco, D.; Joyce-Shaikh, B.; Ueda, R.; Semana, M.; Bauer, M.; Bang, K.; Stevenson, C.; et al. GITR Agonism Enhances Cellular Metabolism to Support CD8+ T-cell Proliferation and Effector Cytokine Production in a Mouse Tumor Model. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Hayashi, K.; Murata-Hirai, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Okamura, H.; Minato, N.; Morita, C.T.; Tanaka, Y. Targeting Cancer Cells with a Bisphosphonate Prodrug. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 2656–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Horibe, K.; Furukawa, K. Enhancement of in vitro and in vivo anti-tumor activity of anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody 220-51 against human neuroblastoma by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Int. J. Mol. Med. 1998, 2, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akahori, Y.; Wang, L.; Yoneyama, M.; Seo, N.; Okumura, S.; Miyahara, Y.; Amaishi, Y.; Okamoto, S.; Mineno, J.; Ikeda, H.; et al. Antitumor activity of CAR-T cells targeting the intracellular oncoprotein WT1 can be enhanced by vaccination. Blood 2018, 132, 1134–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, K.; Kato, T.; Miyahara, Y.; Naota, H.; Mineno, J.; Ikeda, H.; Shiku, H. siRNA-mediated silencing of PD-1 ligands enhances tumor-specific human T-cell effector functions. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).