1. Introduction

Surface water is an indispensable part of the Earth's ecosystem and a significant influencing factor in climate change, ecological environmental protection, and human production and life [

1]. It plays crucial roles in various aspects such as environmental monitoring and management [

2], ecological protection and restoration, disaster prevention and control, emergency response, agricultural production, land use, and people's water safety [

3]. By obtaining and analyzing the spatial distribution and area information of water bodies, we can guide and support humans to adopt better ways of living [

4]. Consequently, precise mapping of surface water holds significant importance for both environmental surveillance and societal advancement.

Due to its expansive coverage, relatively high spatial and temporal resolutions, as well as the distinct advantage of uninterrupted Earth surface monitoring, Remote Sensing (RS) technology has become a ubiquitous tool in the extraction of surface water [

5]. The methods utilized for water extraction from satellite remote sensing images can be categorized into three principal groups: (1) threshold-based methods, (2) machine learning methods, and (3) hybrid methods. During the process of water extraction, threshold-based methods primarily depend on the spectral reflectance properties of water bodies within specific bands, encompassing both single-band threshold techniques and multi-band threshold methodologies. The former utilizes information from a single band [

6] for water body identification, while the latter uses a set of multi-band data to detect water bodies through mathematical and logical operations, such as Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) [

7], Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) [

8], Multi-band Water Index (MBWI) [

9], Background Difference Water Index (BDWI) [

10], Normalized Difference Water Fraction Index (NDWFI) [

11], Composite Normalized Difference Water Index (CNDWI) [

12], etc. Fuzzy C-means, K-means clustering, support vector machine, decision tree, random forest and other machine learning methods are used to identify and extract water bodies. Hybrid methods integrate water features and machine learning classifiers or multi-classifier ensembles to achieve high-precision water body extraction. The image processing involved in hybrid methods is complex, with multiple influencing factors and high uncertainty. Typically, traditional methods heavily depend on the expertise of domain experts and may have limited abilities to express features, which makes it challenging to fully grasp intricate semantic details and spatial connections between pixels.

Compared to traditional water extraction methods, deep learning methods possess the capability to learn and explore deep features, enabling the acquisition of more complex and nonlinear water characteristics [

13]. They can avoid the need for manual adjustment of optimal thresholds, adapt to large-scale learning, and exhibit higher flexibility and generality, thus finding widespread applications in water extraction research. Isikdogan [

14] introduced a unique CNN design named DeepWaterMap, utilizing a fully convolutional network structure that minimizes the number of parameters requiring training and enables comprehensive, large-scale analysis. The network embeds the shape, texture, and spectral features of water bodies to eliminate interfering features such as snow, ice, clouds, and terrain shadows. Chen [

15] presented a novel approach for detecting open surface water in urbanized areas, employing unequal and physical size constraints to recognize water bodies in urban environments. This method addresses the serious confusion errors of traditional water resource indices in high spatial resolution images. The potential application of the method in large-scale water detection tasks is evidenced through experimental verification on spectral libraries and genuine high spatial resolution RS imagery. Kang et al. [

16] introduced a multi-scale context extraction network, MSCENet, aimed at precise and efficient extraction of water bodies from high-resolution optical RS images. This network incorporates multi-scale feature encoders, feature decoders, and context feature extraction modules. Specifically, the feature encoder employs Res2Net to capture rich multi-scale details of water bodies, effectively handling variations in their shape and size. The context extraction module, comprising an expanded convolutional unit and a sophisticated multi-kernel pooling unit, further distills multi-scale contextual information to produce refined high-level feature maps. Luo et al. [

17] proposed an automated method for surface water mapping and constructed a novel surface water mapping model called WatNet. This model addresses the issue of diminished mapping precision caused by the resemblance of non-water features to water features, employing a tailored design for mapping surface water to achieve precise identification of smaller water bodies. The study also constructed the Earth Surface Water Knowledge Base (ESWKB), a freely available dataset based on Sentinel-2 images. Li et al. [

18] proposed a water index-driven deep fully convolutional neural network (WIDFCN) method that achieves precise water delineation without relying on manually collected samples. WIDFCN effectively handles scale and spectral variations of surface water and demonstrates robustness in experiments involving different types of shadows, such as those from buildings, mountains, and clouds. The most important aspect of this method is the extraction of high-precision but incomplete water membranes from water spectral indices, which are then expanded to enhance completeness. This approach realizes an efficient strategy for automatically generating training samples without the need for manual labeling, significantly reducing economic costs. Zhang et al. [

19] proposed an end-to-end CNN water segmentation network, MRSE-Net, based on multi-scale residual and squeeze-excitation (SE) attention. The network enhances prediction results using the SE-attention module to alleviate water boundary ambiguity and reduces the number of model parameters using multi-scale residual modules to accurately extract water pixels, addressing the problem of fuzzy boundaries of small river water bodies. Yu et al. [

20] proposed a network called WaterHRNet, which is composed of multi-branch high-resolution feature extractor (HRNet), feature attention module and segmentation header module. It is a hierarchical focus high-resolution network that can provide high-quality, strong semantic feature representation for precise segmentation of water bodies in various scenarios. Xin Lyu et al. [

21] proposed a multi-scale normalized attention network, MSNANet, for accurate water body extraction in complex scenes. The network incorporates the Multi-Scale Normalized Attention (MSNA) module to fuse multi-scale water body features, highlighting feature representations. It utilizes an optimized spatial pyramid pooling (OASPP) module to refine feature representations using contextual information, improving segmentation performance. Kang et al. [

22] proposed WaterFormer, a combination of transformer and convolutional neural network, for accurate water detection tasks. The network includes dual-stream CNNs, Cross-Level Visual Transformers (CL-ViT), lightweight attention modules (LWA), and sub-pixel upsampling modules (SUS).The network includes dual-stream CNNs, Cross-Level Visual Transformers (CL-ViT), lightweight attention modules (LWA), and sub-pixel upsampling modules (SUS). The dual-stream network abstracts water features from multiple perspectives and levels, embeds cross-level visual transformers in the dual stream to capture long-range dependencies between foundational spatial information and high-order semantic features, and enhances feature abstraction and generates high-resolution, high-quality class-specific representations using lightweight attention modules and sub-pixel upsampling modules.

From the above analysis of the current mainstream water extraction techniques, we can clearly understand that most of the methods are based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). Although CNNs possess powerful feature extraction capabilities, the diversity of water body spatial distributions and the complexity of environmental backgrounds can lead to the loss of boundary details and affect the accuracy of water body extraction when using CNNs on medium-resolution satellite remote sensing images. Thus, they exhibit certain limitations in water body extraction. In recent years, Transformers have attracted attention due to their outstanding semantic representation capabilities and advantages in modeling global information relationships. Particularly, the Swin Transformer [

23] has demonstrated strong feature extraction capabilities, contextual modeling capabilities, and multiscale feature fusion capabilities, providing a strategy for precise water body extraction from remote sensing images. However, research in this area is currently limited. The aim of this research, therefore, is to investigate a novel integration of deep learning networks that leverages multiscale information to the fullest extent, thereby enhancing the identification of water body features. For the first time, we combine deformable convolutions [

24] with the Swin Transformer to increase effective receptive fields and better integrate global semantic information.

This network skillfully combines the powerful local feature extraction capabilities of CNNs with the extensive global feature extraction capabilities of Swin Transformers, enabling high-precision extraction of water bodies. Our main contributions in this research are outlined as follows:

(1) We designed a new combination of deep learning networks, which combines CNNs and Swin Transformers for the first time. The refined model emphasizes the extraction of water body features, particularly the accurate delineation of water body boundaries. To achieve this goal, we capture the image's details and edge information through CNNs and model global contextual information using Swin Transformers to better capture image semantic information. This hybrid model can consider both detailed information in images and global contextual information, thereby improving the accuracy and performance of semantic segmentation.

(2) Considering the complex morphology and size variations of water body boundaries, we use deformable convolutions for the precise extraction of water body boundary features. Deformable convolutions, by introducing offsets, can adaptively adjust the receptive fields, allowing convolutional kernels to adaptively deform on input feature maps according to target shapes, thereby capturing water body features more accurately.

(3) To ascertain the efficacy of our approach, we apply it to water bodies of different sizes and in different environments. We utilized the image dataset of Sentinel-2 to conduct tests in both high mountainous and cloud-covered areas. The results indicate that the model exhibits a high level of accuracy.

The content distribution of the remaining sections of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 introduces the details of the data and methods used in this study.

Section 3 analyzes the experimental results and provides the experimental configuration.

Section 4 discusses the ablation experiments. Finally, our conclusions are presented in

Section 5.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

The experiments were conducted on an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700H 2.30 GHz processor with 16.0 GB of RAM, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 Laptop GPU, and CUDA 11.2. The input image size was set to 256×256, batch size to 2, epochs to 200, and the learning rate to 0.002.

We trained and validated our model on the ESWKB dataset. We divided the dataset into a training set, a test set, and a validation set in a ratio of 6:2:2, with images randomly cropped to the specified pixel size of 256×256. Additionally, simple data augmentation techniques were applied to the training set, including image flipping and random rotations by multiples of 90°.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the SwinDefNet performance, we utilized four widely recognized metrics in the field of semantic segmentation: accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1 score.

The fraction of accurately predicted pixels relative to all pixels is known as accuracy. The fraction of accurately predicted water body pixels among all pixels projected to be water bodies is expressed as precision. Out of all actual water body pixels, recall is the proportion of water body pixels that were accurately anticipated. The F1 score, which is a measure of the model's overall performance, is the harmonic mean of accuracy and recall.

In these evaluation metrics, accuracy represents the proportion of pixels that are correctly predicted relative to the total number of pixels. The precision quantifies the proportion of pixels that are labeled as bodies of water but are also bodies of water. Recall, on the other hand, measures the proportion of pixels correctly identified in the actual water body. F1 score is the harmonic average of accuracy and recall and can be used as a comprehensive measure of the overall performance of the model.

The calculation methods for accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score are as follows:

In the formulas, TP represents true positives, indicating the number of samples where the model correctly predicts water body when the actual class is water body; TN represents true negatives, indicating the number of samples where the model correctly predicts non-water body when the actual class is non-water body; FP represents false positives, indicating the number of samples where the model incorrectly predicts water body when the actual class is non-water body; FN represents false negatives, indicating the number of samples where the model incorrectly predicts non-water body when the actual class is water body.

3.3. Method Comparison

To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, we compared it with four commonly used methods: U-Net, ResNet, DeepLabv3+, and DeepWaterMapv2. Here are detailed descriptions of these methods:

U-Net: U-Net is a fully convolutional neural network architecture with an encoder-decoder structure that is widely used for image segmentation tasks due to its ability to capture contextual information and precise localization. The encoder extracts image features through convolutional layers, while the decoder progressively restores the spatial resolution of the image. By introducing skip connections, it merges the features from the encoder and decoder to improve segmentation accuracy. U-Net has been widely applied in remote sensing image segmentation due to its efficient and reliable performance. The model explored in this study also adopts an encoder-decoder structure, hence we chose this model for comparison.

ResNet: ResNet (Residual Network) [33] is a CNN designed to address the issues of gradient vanishing and representation bottlenecks in deep networks. By introducing Residual Blocks, the model allows the network to learn residual representations between input and output, optimizing deep networks. This structure enables ResNet to construct deeper network models while maintaining lower error rates. ResNet comes in multiple versions, and in this paper, we utilize ResNet-50.

DeepLabv3+: DeepLabv3+ is an advanced semantic segmentation model that integrates multi-scale features through an encoder-decoder structure, combined with dilated convolutions and ASPP modules to expand the receptive field and capture contextual information. The decoder module effectively merges high and low-resolution features to refine segmentation results, particularly focusing on object boundaries.

DeepWaterMapv2: DeepWaterMapv2 focuses on surface water mapping tasks and adopts the U-Net network structure. By iteratively applying convolutional and pooling operations, it effectively extracts key features from images for the precise identification and extraction of water body regions.

3.4. Analysis of Experimental Results

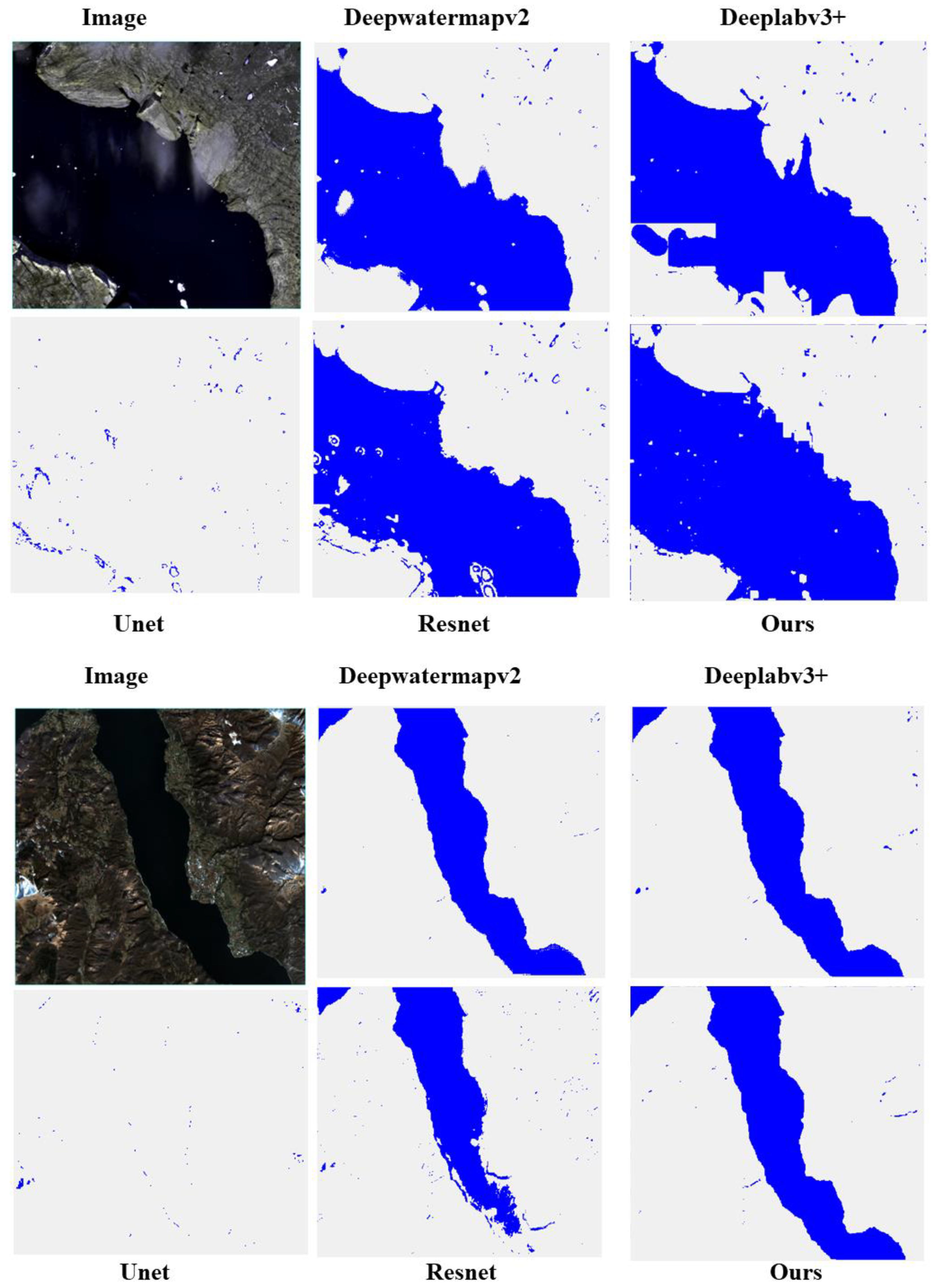

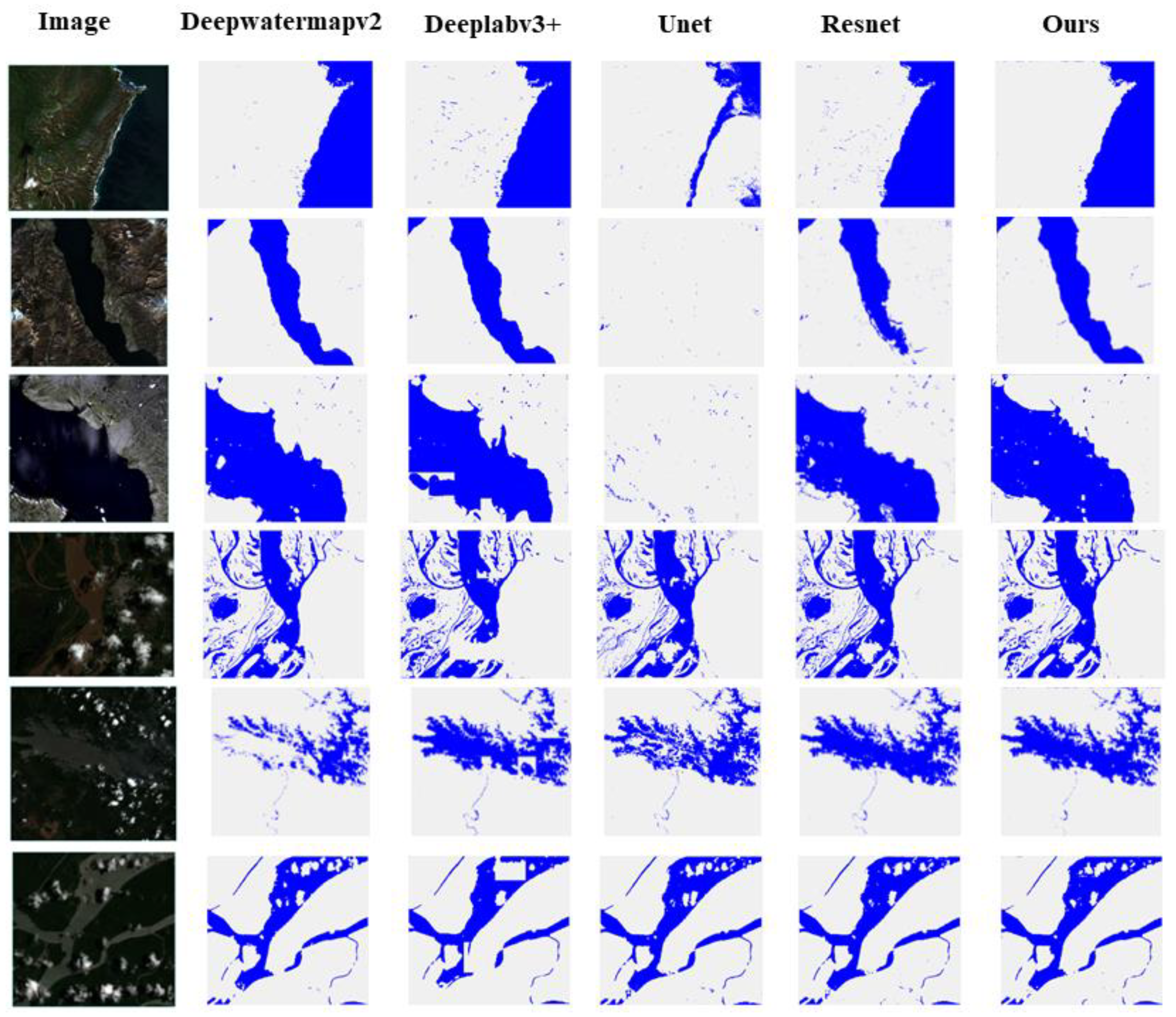

After completing model training, we used 20% of the dataset for validation. In the validation set, we selected six images to demonstrate the prediction results (as shown in

Figure 7), including mountainous regions with large variations in terrain and areas with high cloud cover. To accurately evaluate the performance of SwinDefNet ,we compare it with other advanced water body detection methods,

Table 2 presents the average values of four evaluation metrics for all images in the test set. Additionally, compared to other methods, our model achieved results of over 90%, with values of 97.89% for accuracy, 94.98% for precision, 90.05% for recall, and 92.33% for F1 score, respectively.

Through comparison and analysis of the four metrics, we found that our model achieved the highest accuracy among all methods. This indicates that our model has the best overall predictive ability for mapping surface water and can better extract water bodies from remote sensing images. Additionally, when compared to other methods, our model also achieved the highest recall, indicating that it can capture more water pixels during surface water mapping, with the lowest degree of omission in extracting water pixels.

Analyzing

Table 2, we found that in the test, ResNet achieved an F1 score of 92.68%, which is 0.35% higher than our proposed model, indicating that ResNet has better overall performance. However, its recall was 88.96%, indicating that it would miss many water pixels during extraction, showing a certain gap in the fine extraction of water bodies. DeepWaterMapv2 achieved a precision as high as 99.07%, but with a recall of only 91.89%. This suggests that the DeepWaterMapv2 method sacrifices recall for precision in model prediction, indicating room for improvement in the fine extraction of water bodies.

Figure 7 compares the predicted images generated by different methods, while

Figure 8 shows the true labels of the predicted images.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present partial results of surface water mapping in mountainous and cloudy regions, with other result comparisons provided in the

Appendix at the end of the document. We observe that our proposed model exhibits excellent noise suppression in the background (see

Figure 9), outperforming ResNet and DeepLabv3+ methods. Moreover, satisfactory extraction results are achieved for winding small rivers and complex urban areas (see

Figure 10). Compared to other methods, the boundaries are clearer, and in regions with higher cloud cover, our model has the lowest probability of misclassifying the background as water, compared to U-Net and ResNet methods.

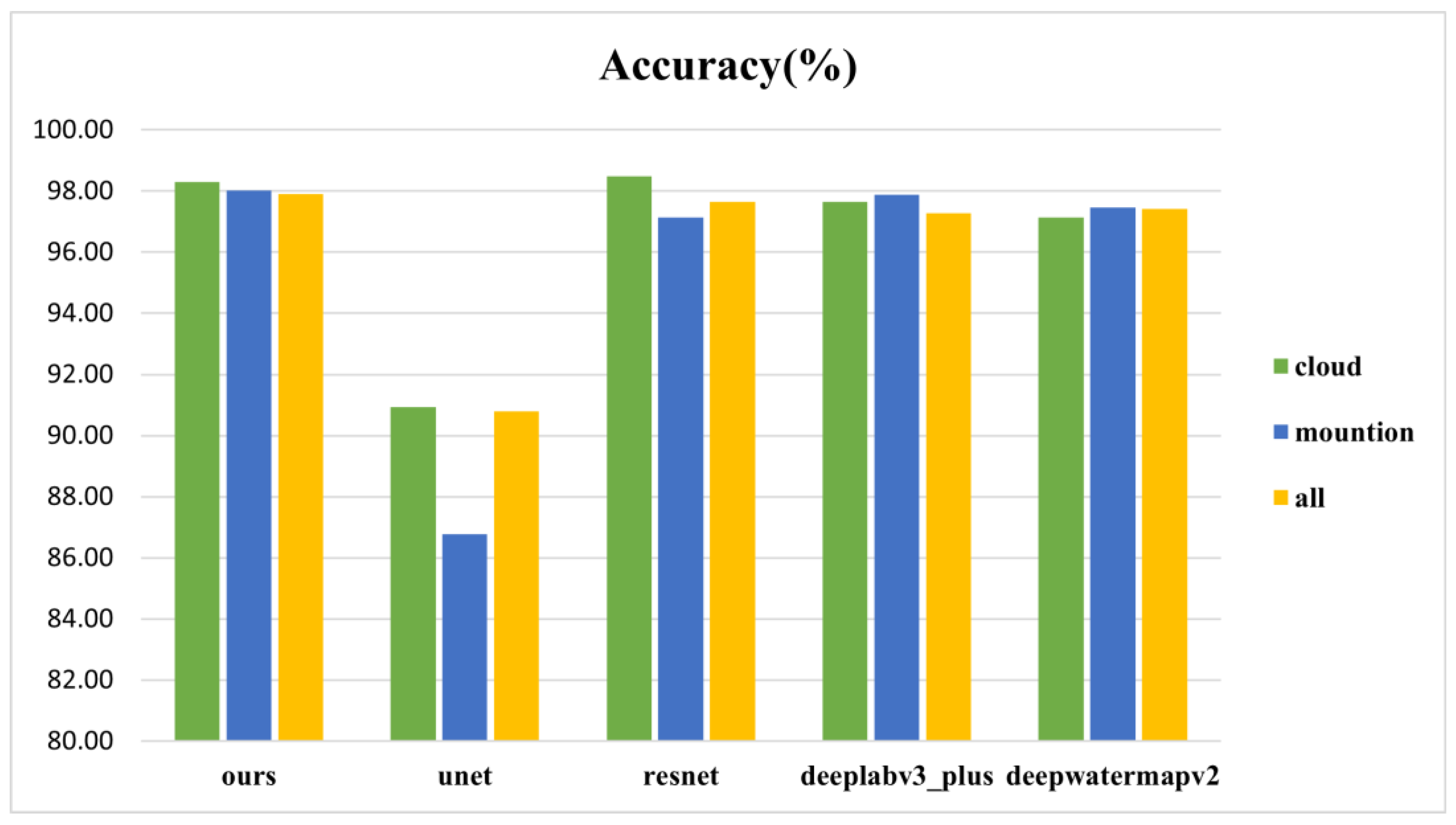

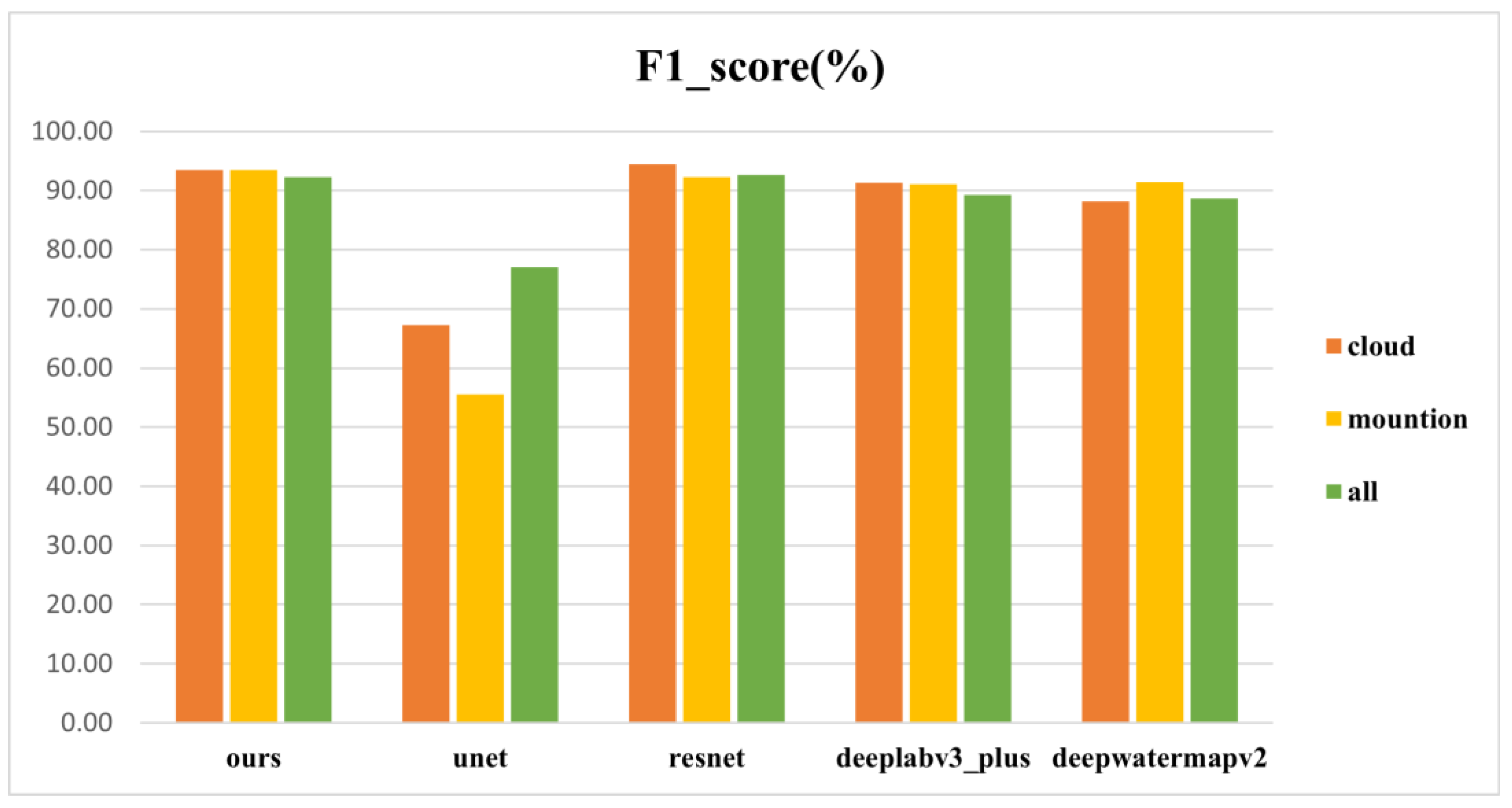

In order to further confirm the reliability and accuracy of our method, we conducted tests in various regions, comparing the performance of U-Net, ResNet, DeepLabv3+, and DeepWaterMapv2 in cloudy and mountainous areas. The results for accuracy and F1 score are shown in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, respectively.

Table 3 provides detailed numerical values of the four evaluation metrics for the five methods in the three regions and the entire validation dataset.

Observing

Table 3, we can see that our proposed model performs best in mountainous regions, with accuracy, recall, and F1 score values of 98.03%, 96.61%, and 93.52%, respectively. In the extraction of water bodies in mountainous regions, except for U-Net, all other methods achieved satisfactory results, with accuracy above 97%. Although U-Net's performance in mountainous regions is not ideal, it achieved good results in handling elongated and small water bodies in cloudy and urban areas.

Our model achieved an accuracy and F1 score of 98.30% and 93.46%, respectively, in cloudy areas. Compared to the best-performing ResNet, the differences are only 0.19% and 1%, respectively. Compared to other methods, our recall is highest at 92.22%, indicating that when predicting cloudy areas, we sacrificed some accuracy to reduce the omission of water pixels, enabling fine extraction of water bodies. This is also evidenced by our predicted images. Meanwhile, by comparing the labeled image with the predicted image, we observed that our model exhibits a higher similarity in extracting small water bodies' boundaries. This indicates that our experiment has certain advantages in refining the processing of small water bodies.

4. Discussion

In this part, we performed ablation tests to evaluate the significance of various components, along with discussing the impact of the Swin Transformer and Deformable Convolution on the network's performance. The model used the same training set, test set, and validation set in the ablation experiments.

Firstly, to validate the effectiveness of Swin Transformer in land water mapping tasks, we first compared the combined Swin Transformer and DeepLabV3+ model (see Model 1 in

Table 4) with the DeepLabV3+ model using the original Xception backbone (see Model 3 in

Table 4). Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and f1_score were used as evaluation metrics, the results showed that using Swin Transformer improved Accuracy and f1_score by 1.20% and 3.93% respectively. Precision and Recall also increased by 6.82% and 0.28% respectively. The analysis indicated that using Swin Transformer increased the accuracy of model predictions and improved its reliability. Additionally, there was a 6.82% increase in Precision which suggests that after incorporating Swin Transformer into the model, it became more accurate at predicting water pixels in instances where it is necessary for classification tasks while reducing classification errors caused by misjudgments of water pixels.

Secondly, to validate the effectiveness of Deformable Convolutional Networks (Deformable Conv), we compared a DeepLabV3+ model with Swin Transformer as its backbone network using regular 3×3 convolutions with another one using Deformable Conv (refer to Model 2 in

Table 4). The results showed that after incorporating Deformable Convolutional Networks into our model's architecture led to improvements in Accuracy (+0.22%), Precision (+0.03%), Recall (+1.01%), and f1_score (+0.6%). This indicates an enhancement in both accuracy and reliability after integrating Deformable Conv into our model's architecture while also improving its ability to identify water pixels through an increase of +1 .01 % recall rate.

Through experimental analysis, we can confirm that both Swin Transformer and Deformable Conv are beneficial for water extraction tasks. The combined use of these two components has also enhanced the precision of land water mapping to achieve fine-grainedextraction of water bodies.

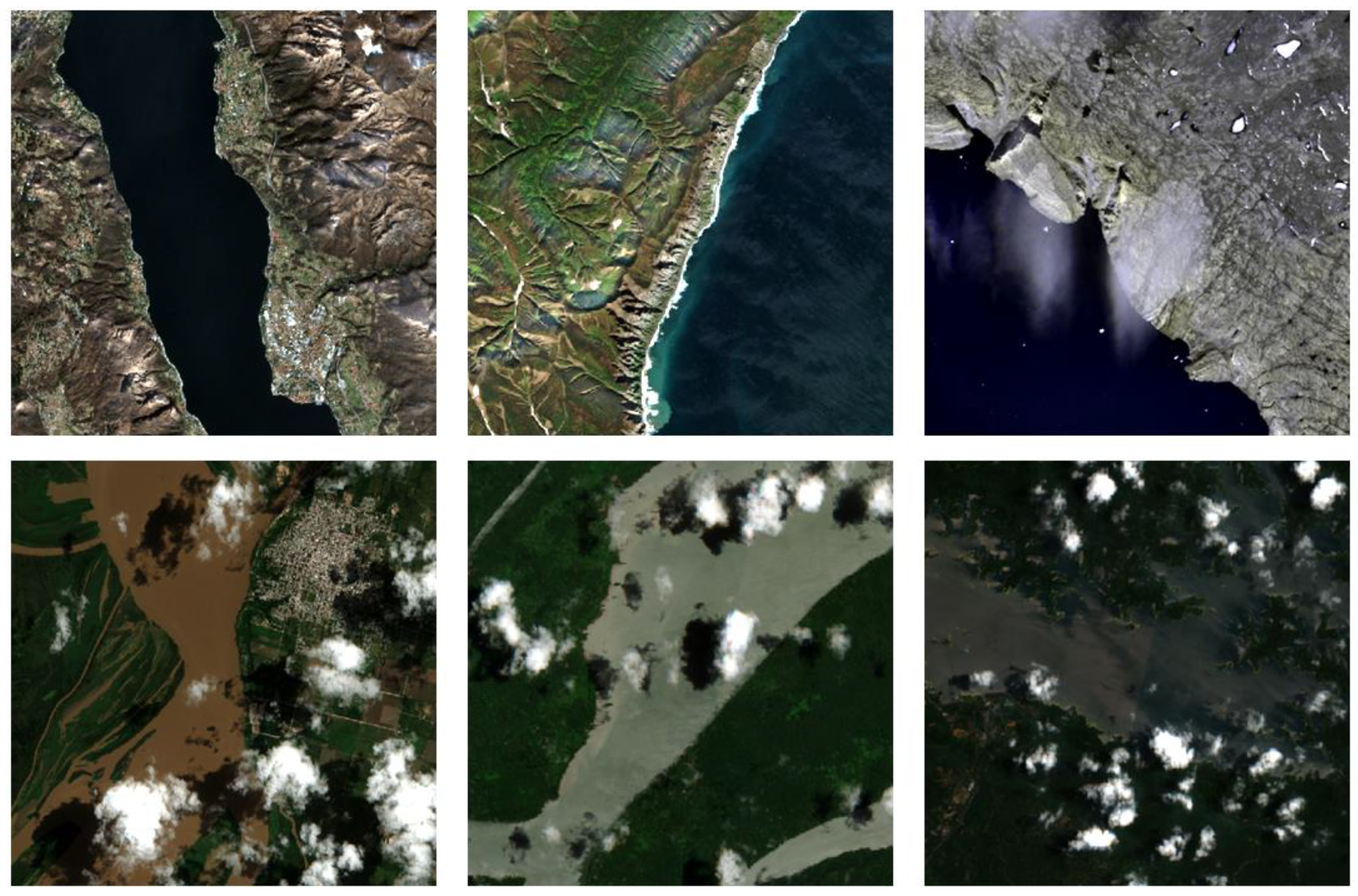

Figure 1.

Representation of Regions in Images (The first line represents mountains, and the second line represents cloud regions.).

Figure 1.

Representation of Regions in Images (The first line represents mountains, and the second line represents cloud regions.).

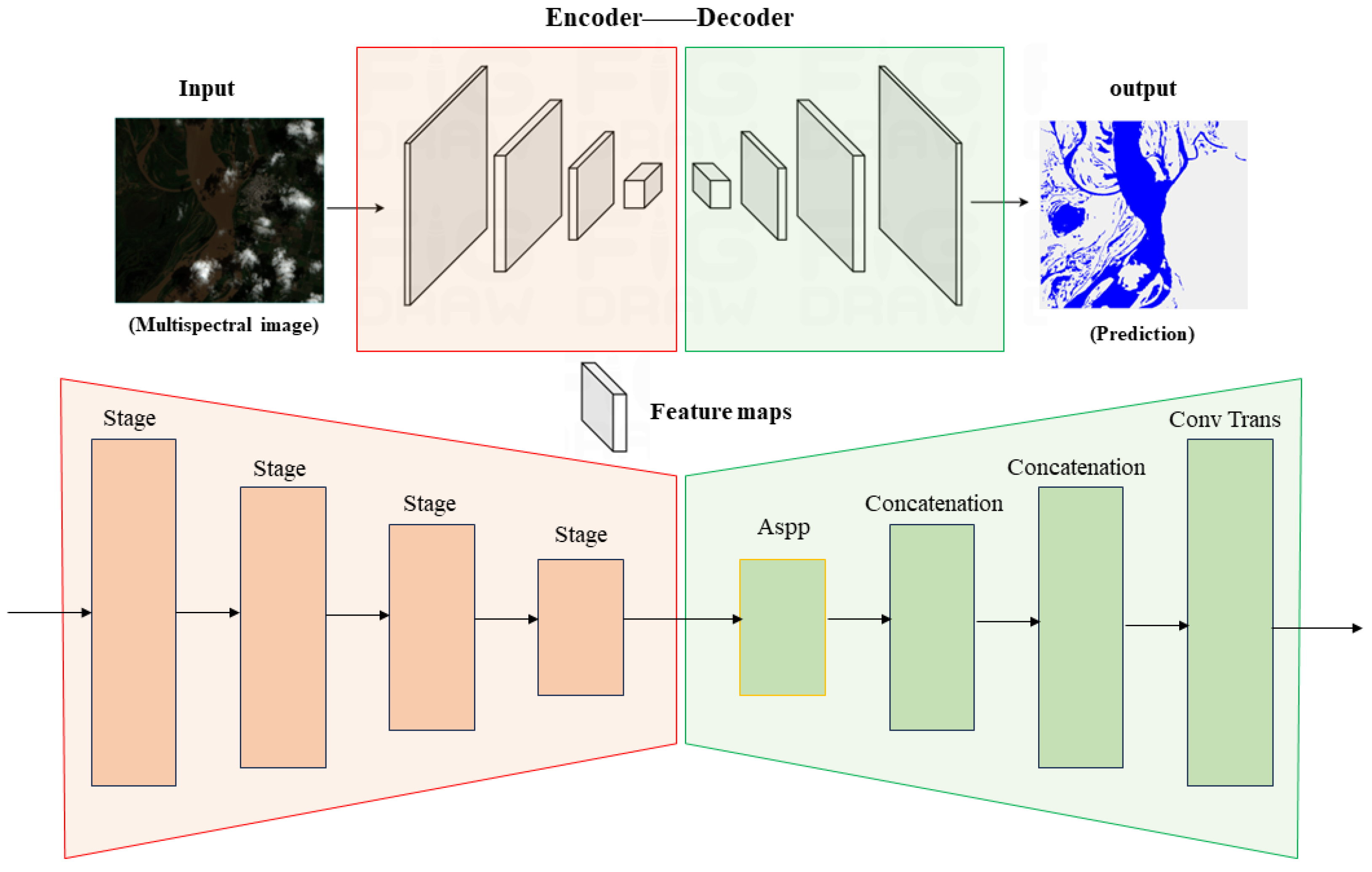

Figure 2.

Use of encoder-decoder architecture in semantic segmentation. (Encoder: the spatial dimensions of features gradually decrease while the depth (number of channels) increases. Decoder: the spatial dimensions of feature maps gradually increase while the depth decreases).

Figure 2.

Use of encoder-decoder architecture in semantic segmentation. (Encoder: the spatial dimensions of features gradually decrease while the depth (number of channels) increases. Decoder: the spatial dimensions of feature maps gradually increase while the depth decreases).

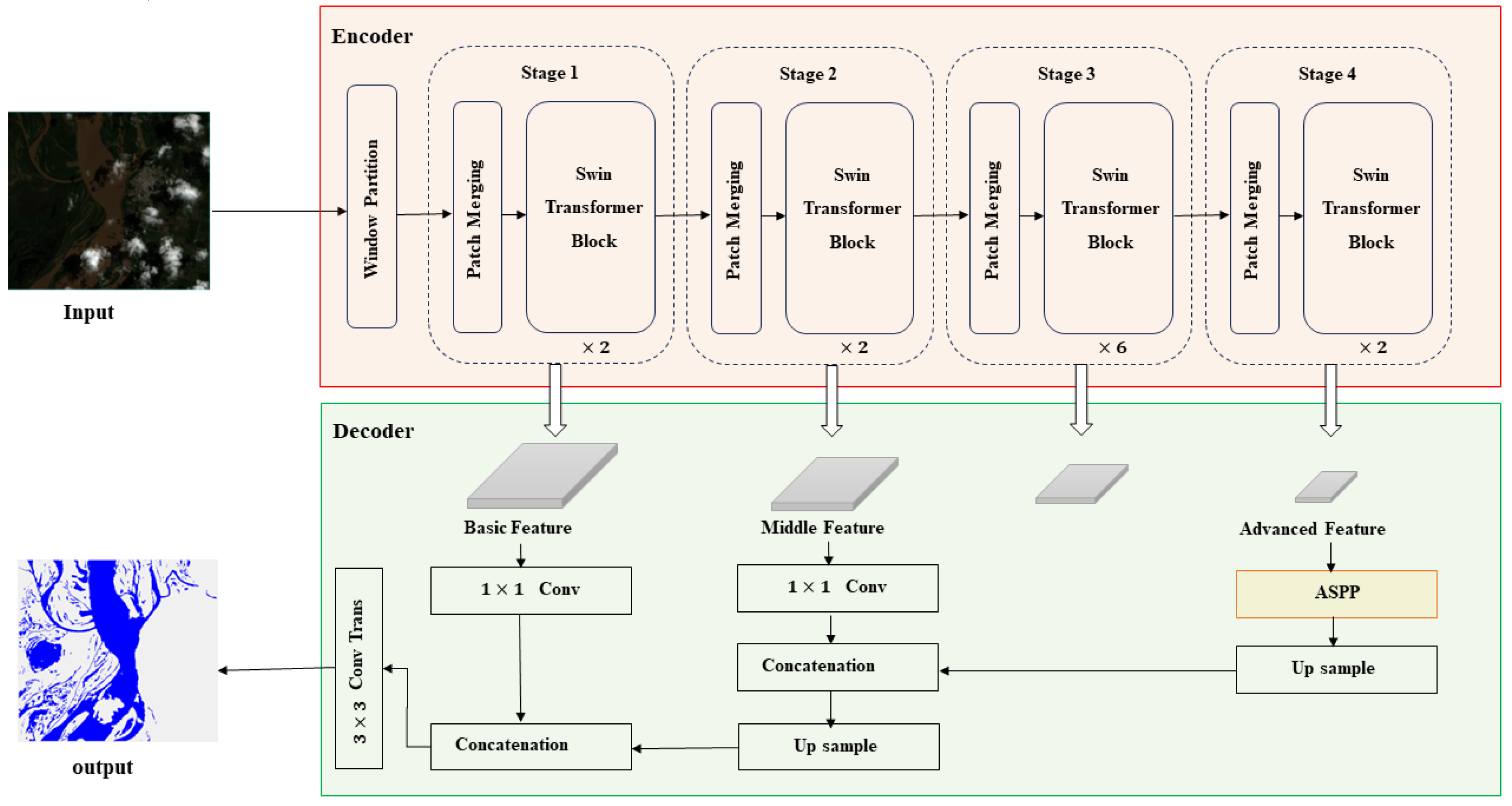

Figure 3.

Figure 3. SwinDefNet's network structure diagram. Normalization and ReLU activation layers follow each convolution operation in the network.

Figure 3.

Figure 3. SwinDefNet's network structure diagram. Normalization and ReLU activation layers follow each convolution operation in the network.

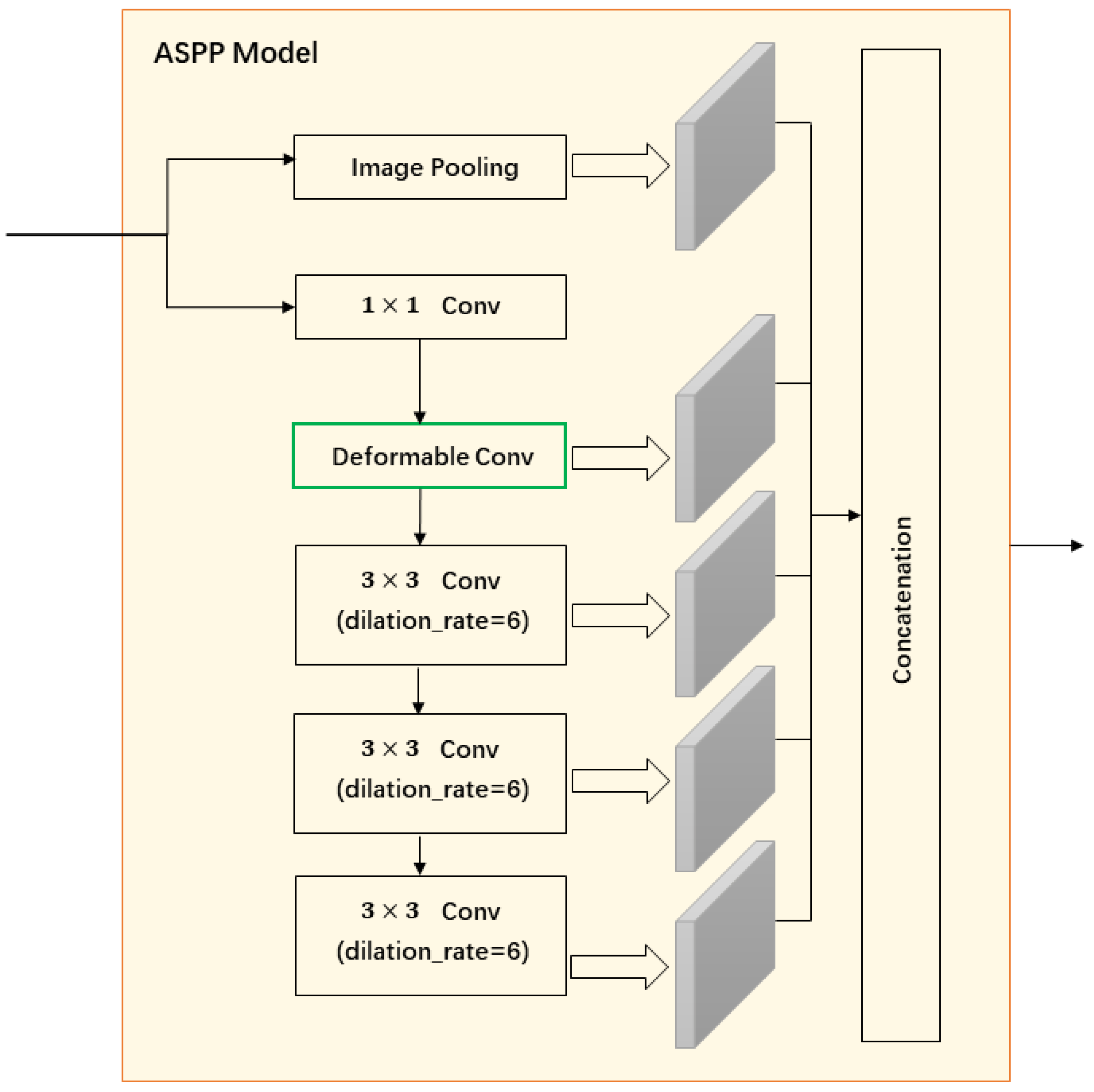

Figure 4.

Internal details of the ASPP module.

Figure 4.

Internal details of the ASPP module.

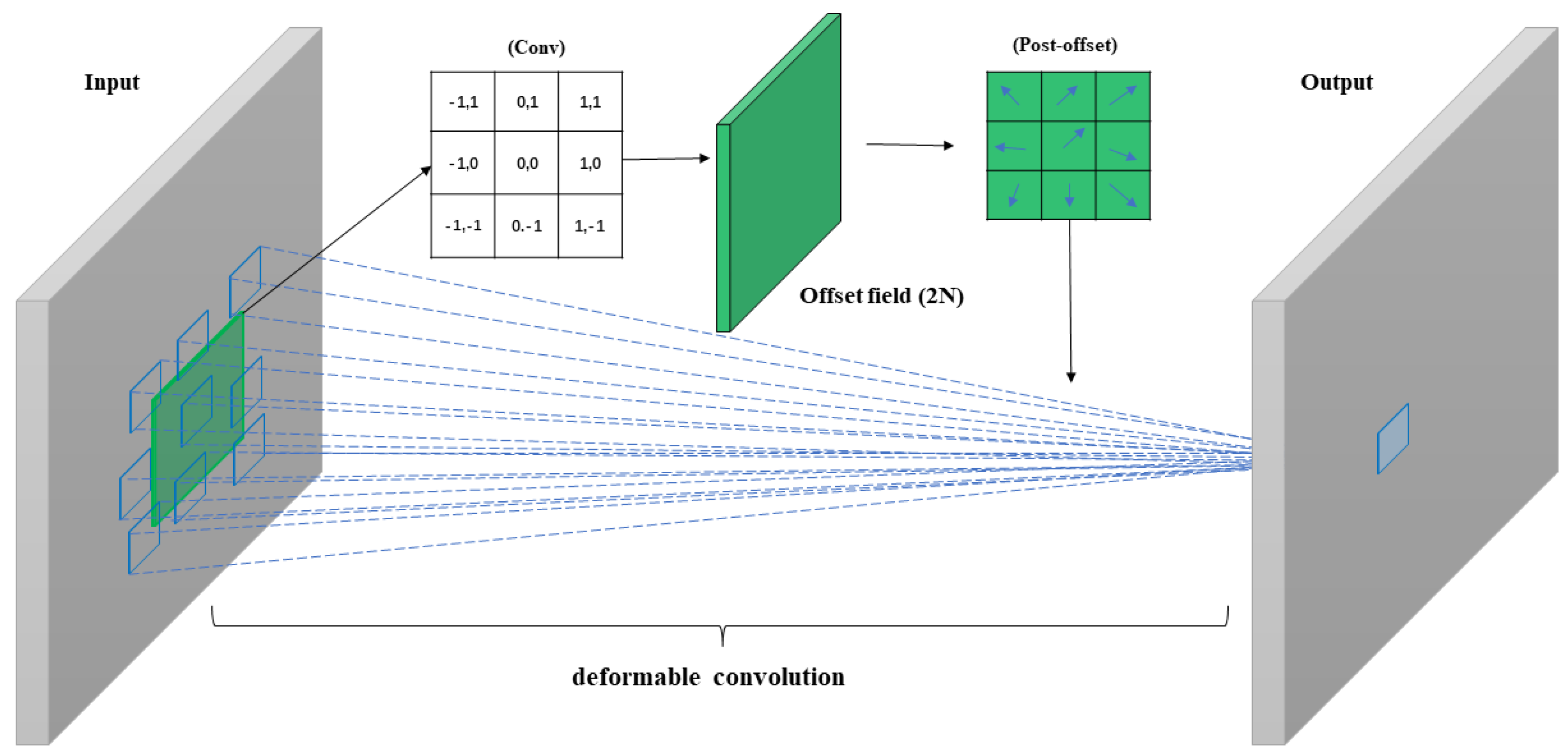

Figure 5.

Using 3×3 convolution as an example, this demonstrates the offset process of deformable convolution and shows the corresponding effective receptive field.

Figure 5.

Using 3×3 convolution as an example, this demonstrates the offset process of deformable convolution and shows the corresponding effective receptive field.

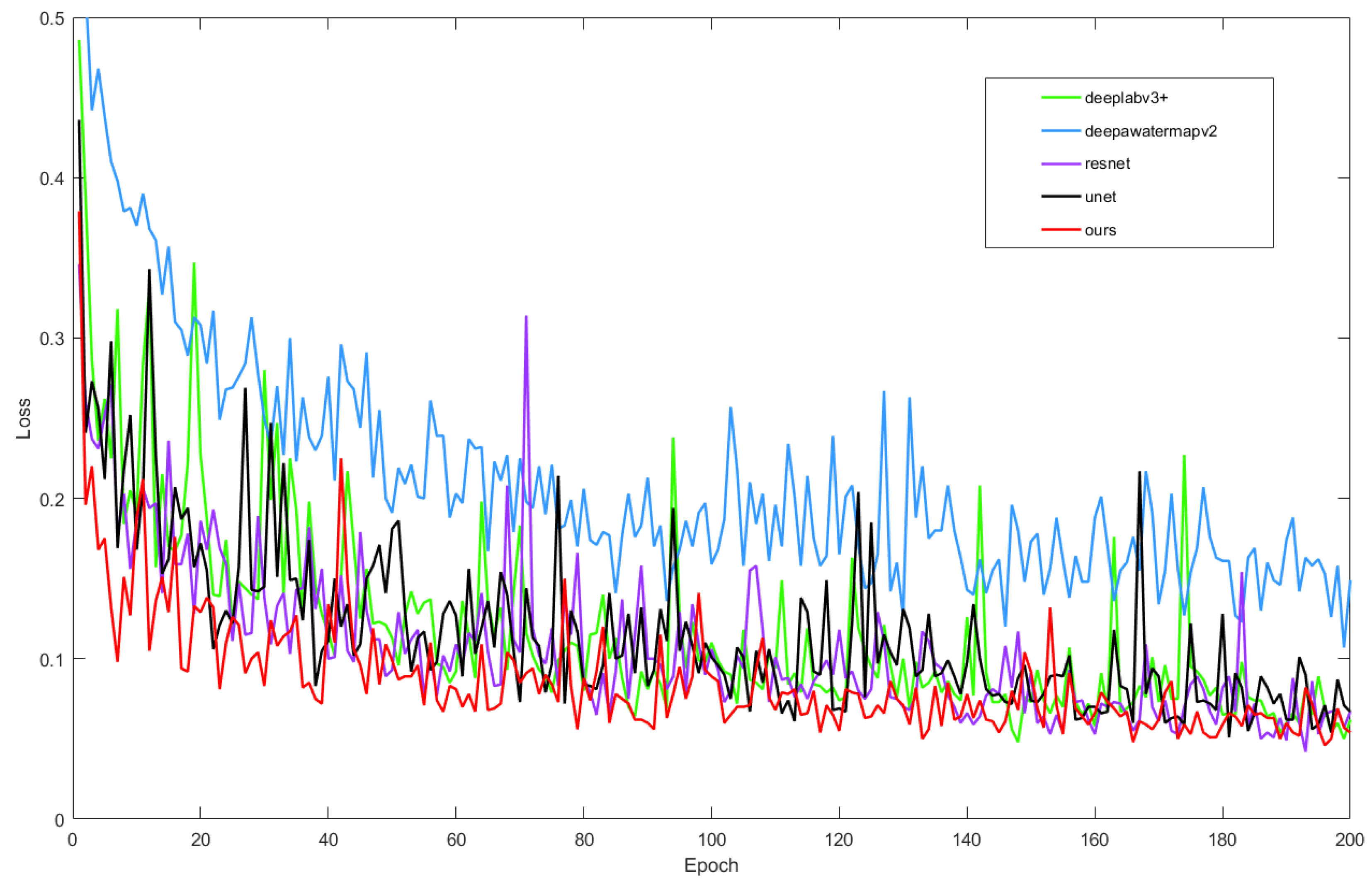

Figure 6.

Visualization of the loss for U-Net, ResNet, DeepLabv3+, DeepWaterMapv2, and our proposed model after 200 epochs of training.

Figure 6.

Visualization of the loss for U-Net, ResNet, DeepLabv3+, DeepWaterMapv2, and our proposed model after 200 epochs of training.

Figure 7.

Comparison of predicted results using different methods on test images, with red circles indicating areas of comparison between the predicted images generated by each method.

Figure 7.

Comparison of predicted results using different methods on test images, with red circles indicating areas of comparison between the predicted images generated by each method.

Figure 8.

Labels data for illustrating the prediction results.

Figure 8.

Labels data for illustrating the prediction results.

Figure 9.

Results of water extraction in hilly regions are compared with existing approaches and our suggested model in mountainous regions.

Figure 9.

Results of water extraction in hilly regions are compared with existing approaches and our suggested model in mountainous regions.

Figure 10.

Comparison of our suggested model's and other approaches' water extraction outcomes in cloudy regions.

Figure 10.

Comparison of our suggested model's and other approaches' water extraction outcomes in cloudy regions.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the accuracy of several methods in various geographical areas.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the accuracy of several methods in various geographical areas.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the F1 score of several methods in various geographical areas.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the F1 score of several methods in various geographical areas.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Challenges of Different Regions.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Challenges of Different Regions.

| Region |

Characteristics |

Challenges |

| Mountainous Area |

Large undulating terrain, complex landforms, scattered water bodies, and high-altitude areas that may be covered by ice and snow. |

Water bodies are often obstructed by mountains, resulting in incomplete extraction information; their scattered distribution leads to a small extraction scale range; there is also potential interference from ice and snow. |

| Cloudy Area |

Under conditions of frequent clouds, rain, and fog, cloud cover areas are large and last for long durations. Clouds exhibit spectral characteristics similar to water bodies in some bands. |

Cloud cover affects the transmission and reflection characteristics of remote sensing images, increasing the difficulty of water body extraction. Due to their spectral similarities, confusion between clouds and water bodies is prone to occur. |

Table 2.

Evaluation metrics of different methods. Average values for validation set images.

Table 2.

Evaluation metrics of different methods. Average values for validation set images.

| Method |

Accuracy(%) |

Precision(%) |

Recall(%) |

f1_score(%) |

| Ours |

97.89 |

94.98 |

90.05 |

92.33 |

| Unet |

90.79 |

95.24 |

72.17 |

77.03 |

| Resnet |

97.65 |

97.26 |

88.96 |

92.68 |

| Deeplabv3_plus |

97.27 |

93.80 |

86.53 |

89.22 |

| Deepwatermapv2 |

97.41 |

99.07 |

81.89 |

88.69 |

Table 3.

Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score results of water mapping in different regions for the five methods.

Table 3.

Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score results of water mapping in different regions for the five methods.

| Method |

Ours |

Unet |

Resnet |

Deeplabv3+ |

Deepwatermapv2 |

| Mountainous Area |

| Accuracy |

98.03% |

86.77% |

97.14% |

97.88% |

97.47% |

| Precision |

95.99% |

89.24% |

97.97% |

95.42% |

99.34% |

| Recall |

91.61% |

49.18% |

87.91% |

89.18% |

85.65% |

| f1_score |

93.52% |

55.56% |

92.32% |

91.08% |

91.46% |

| Cloud Area |

| Accuracy |

98.30% |

90.93% |

98.49% |

97.64% |

97.14% |

| Precision |

94.97% |

93.66% |

97.12% |

93.81% |

98.61% |

| Recall |

92.22% |

63.05% |

92.12% |

89.27% |

84.85% |

| f1_score |

93.46% |

67.29% |

94.46% |

91.33% |

88.19% |

Table 4.

The results of the ablation experiments.

Table 4.

The results of the ablation experiments.

| Model |

Swin Transform |

Deformable Conv |

Accuracy(%) |

Precision(%) |

Recall(%) |

f1_score(%) |

| 1 |

✓ |

✓ |

97.89 |

94.98 |

90.05 |

92.33 |

| 2 |

✓ |

|

97.67 |

94.96 |

89.04 |

91.73 |

| 3 |

|

✓ |

96.70 |

88.17 |

89.77 |

88.40 |