Submitted:

31 May 2024

Posted:

06 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Essential Oil Chemistry

2.2. Ethical Review and Informed Consent

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Treatment

2.5. Sampling

2.6. Oral DNA Extraction

2.7. Amplicon library preparation and sequencing

2.8. Bioinformatic Analyses and Ecological Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition

3.2. Demographic Features of the Study Population

3.3. Microbiome Diversity and Composition

3.3.1. Sequencing Data Profiles

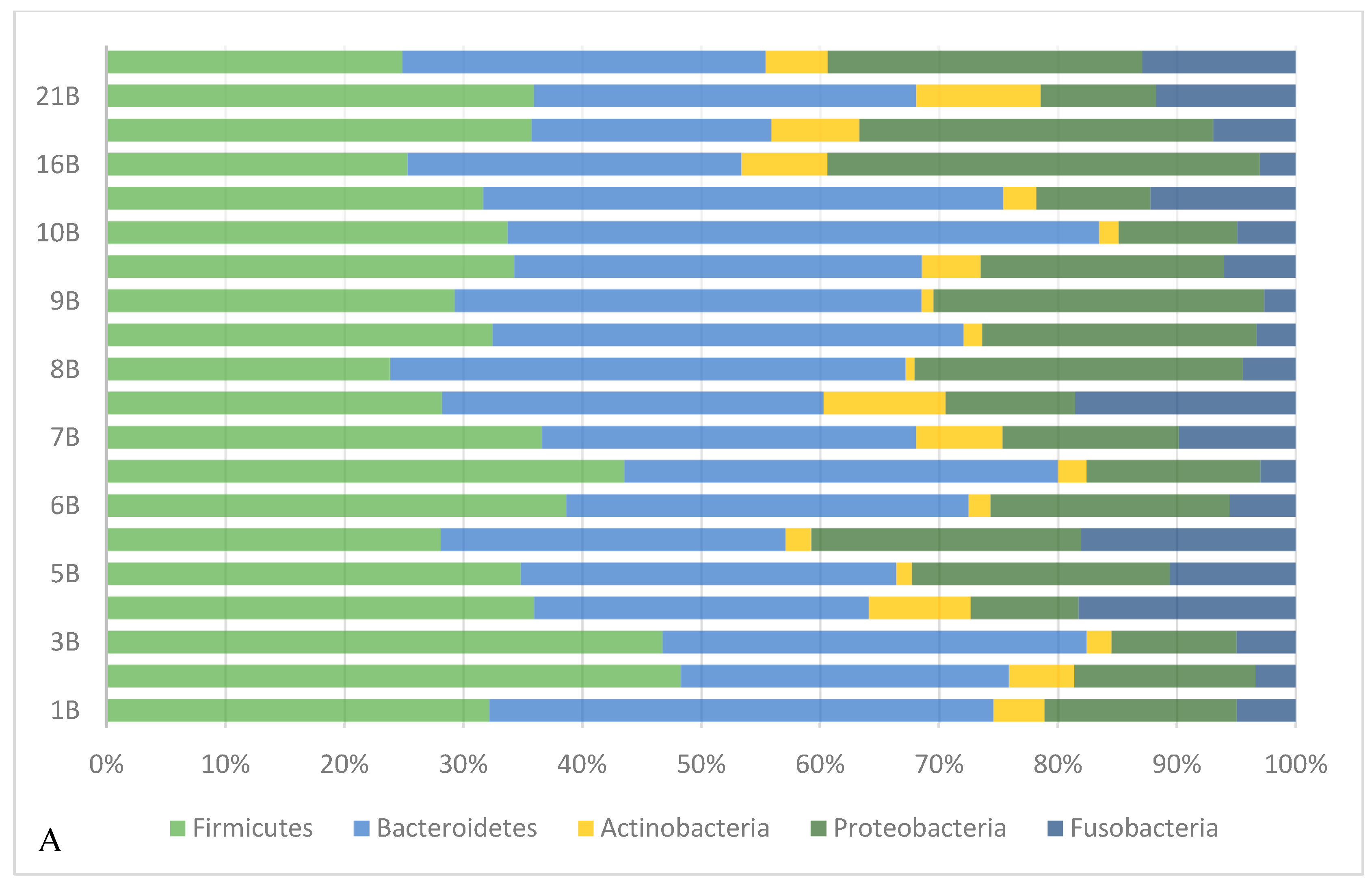

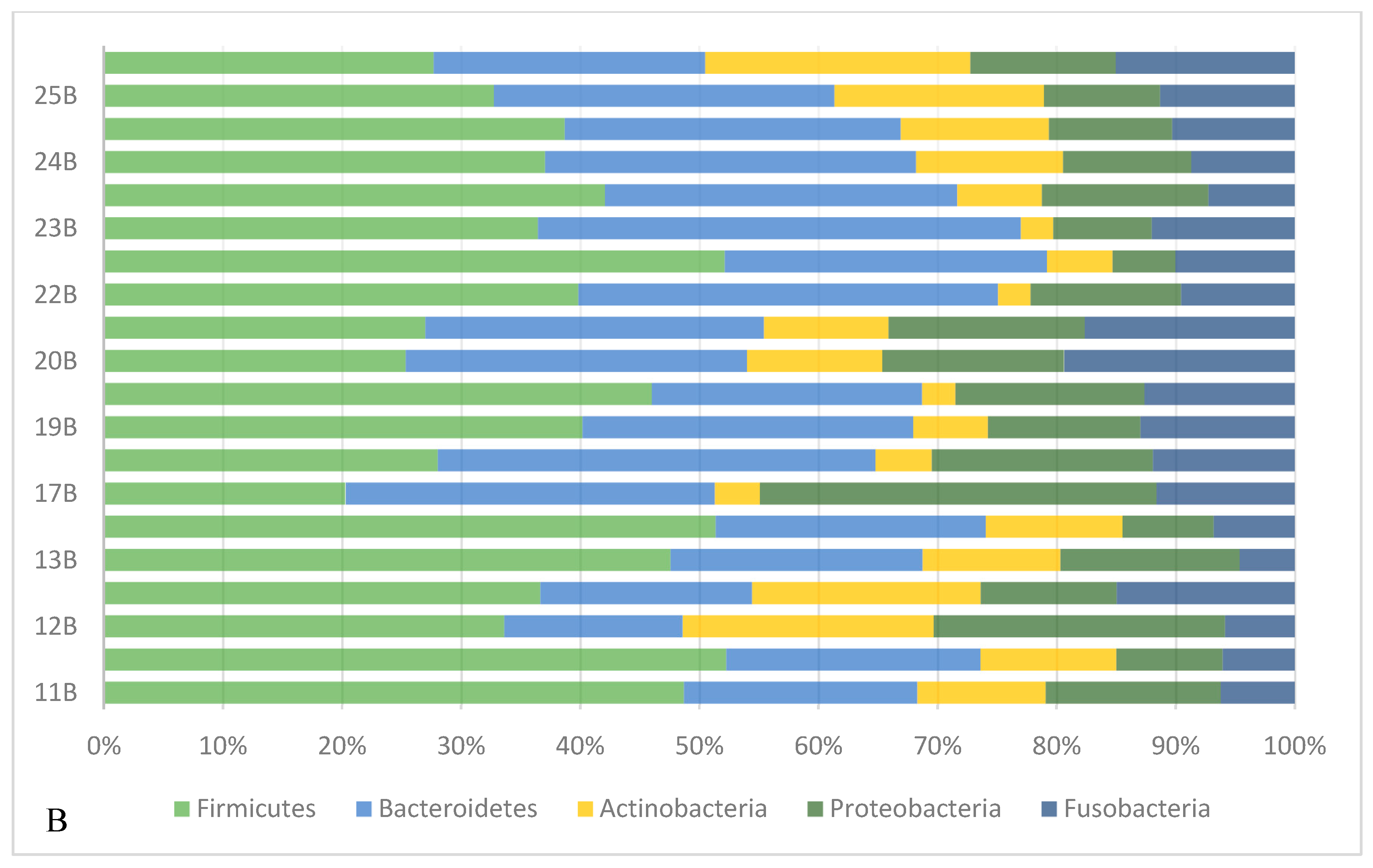

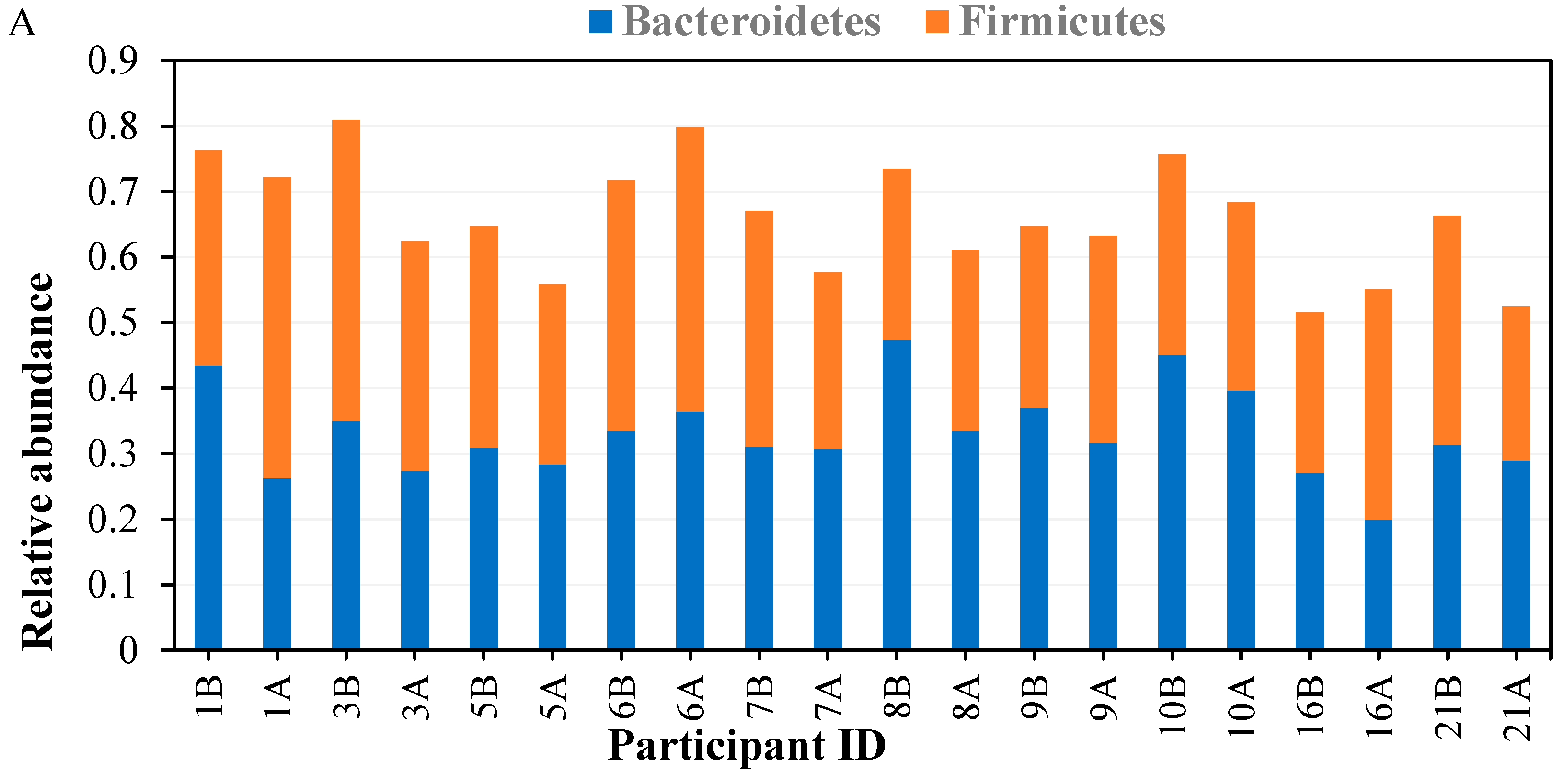

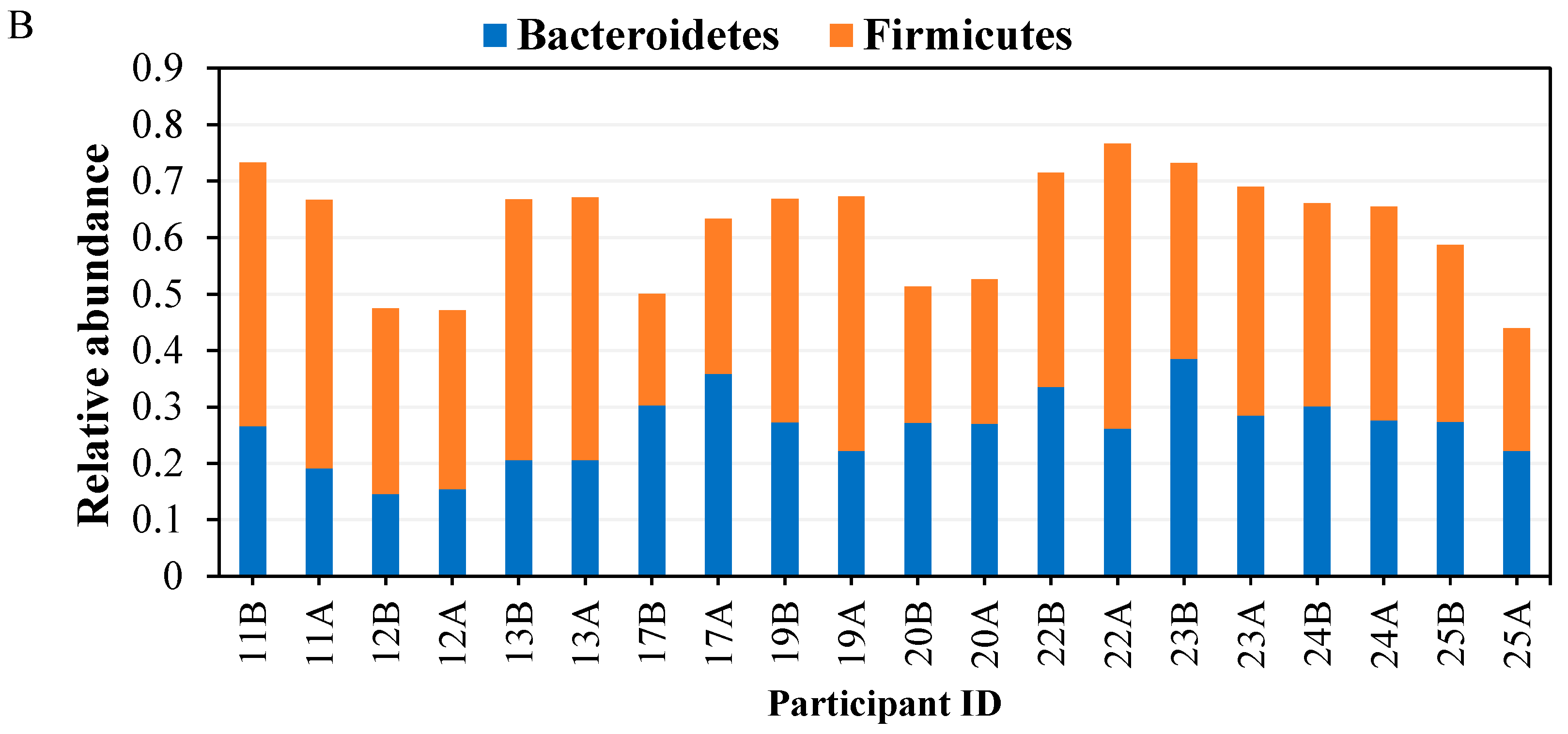

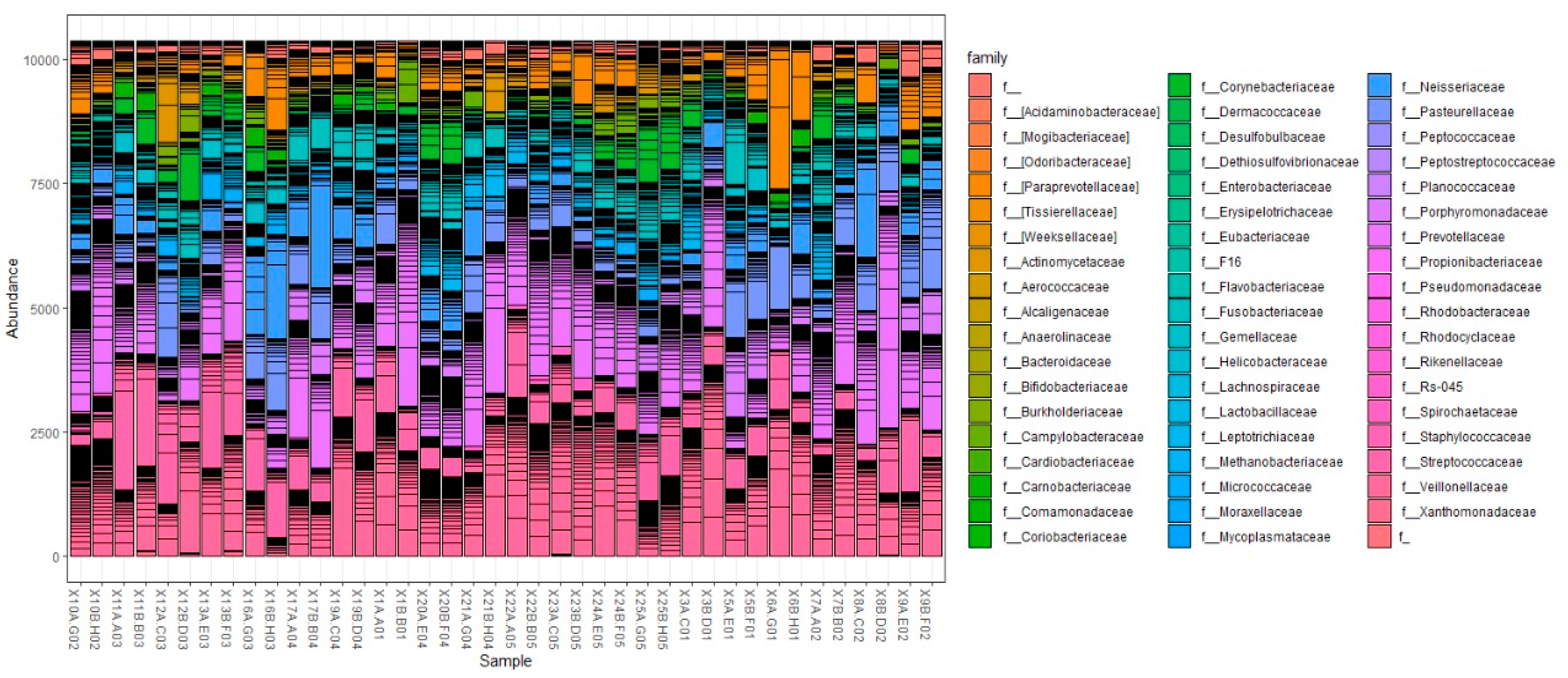

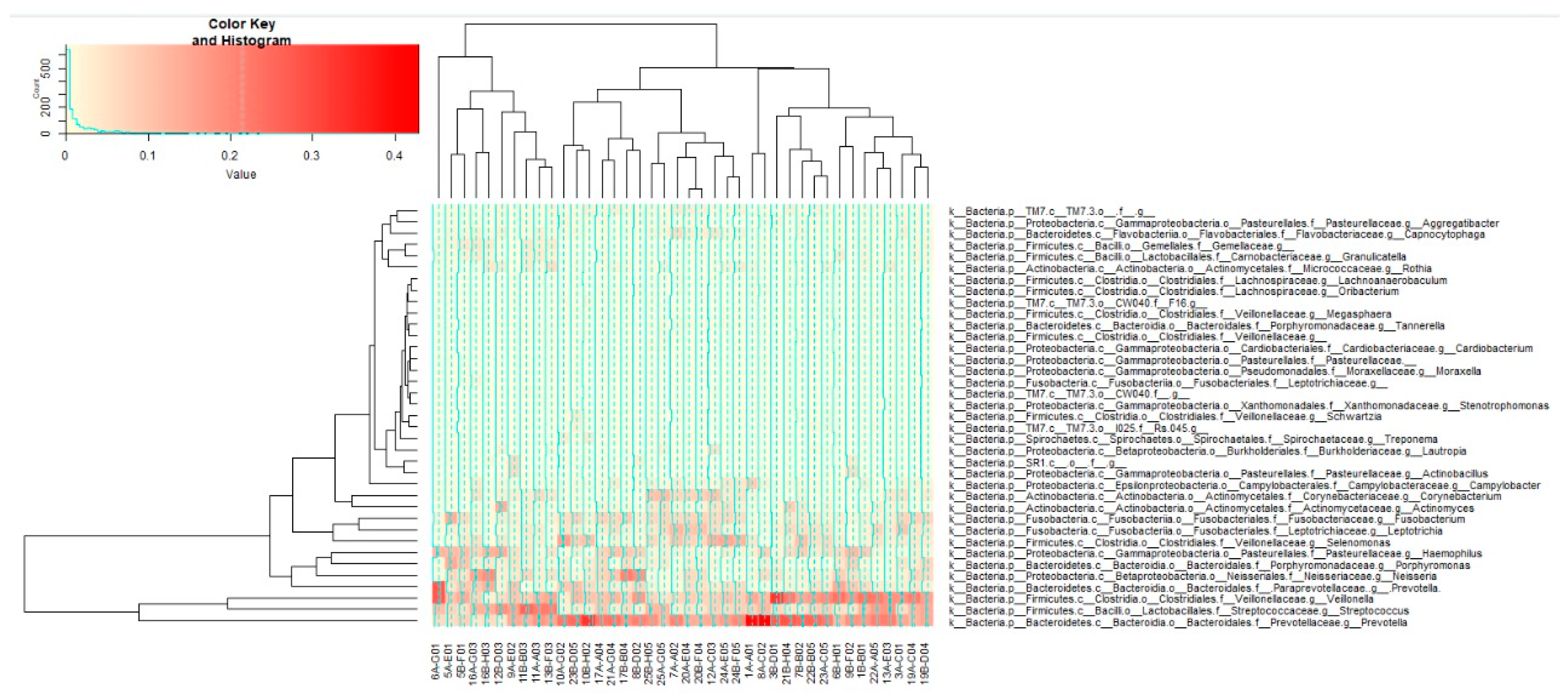

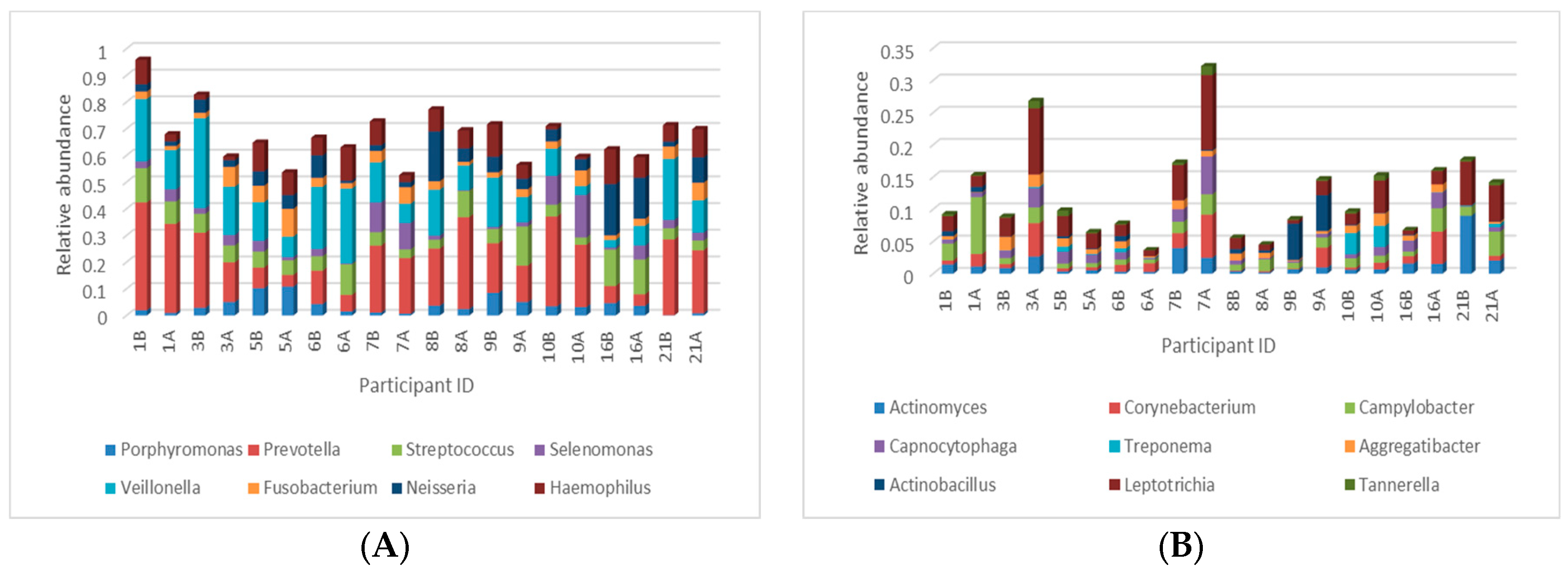

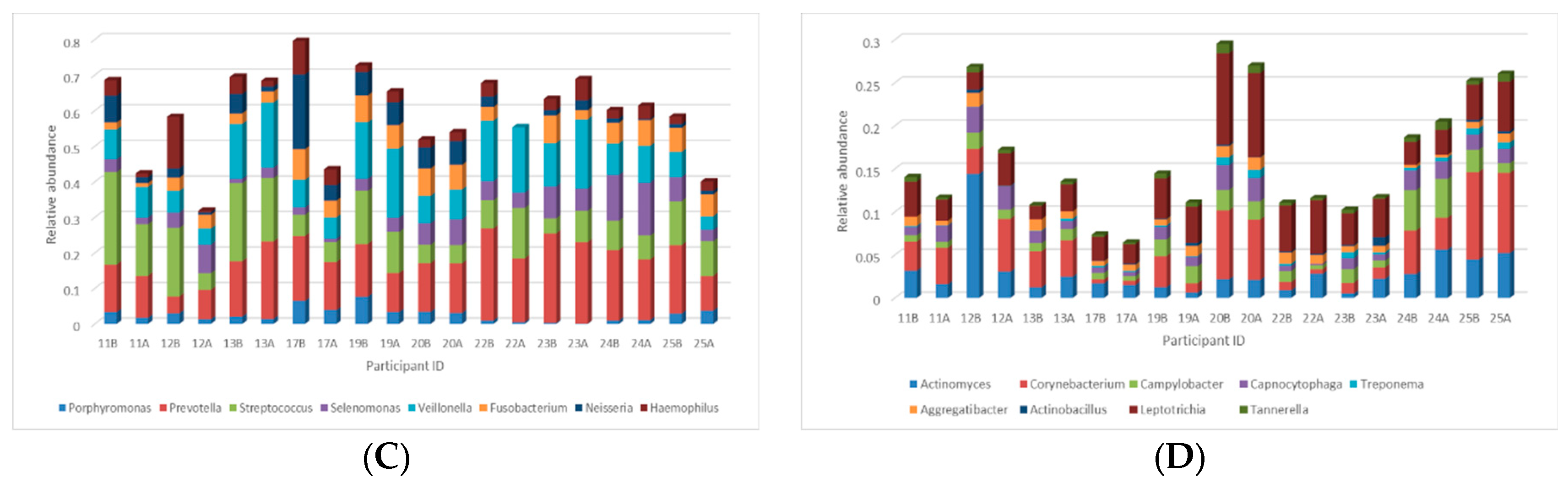

3.3.2. Taxonomical Classification

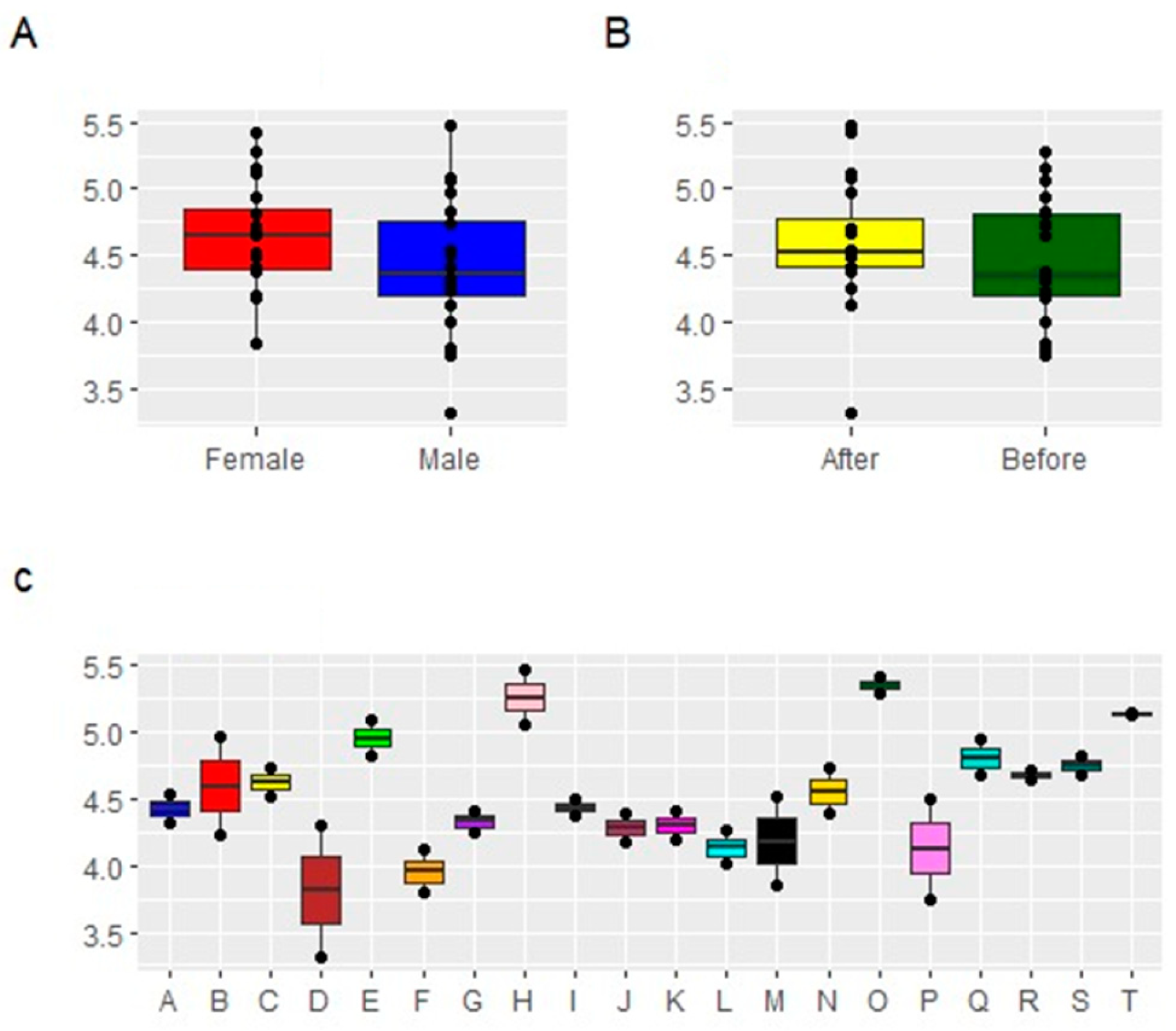

3.3.3. Alpha Diversity

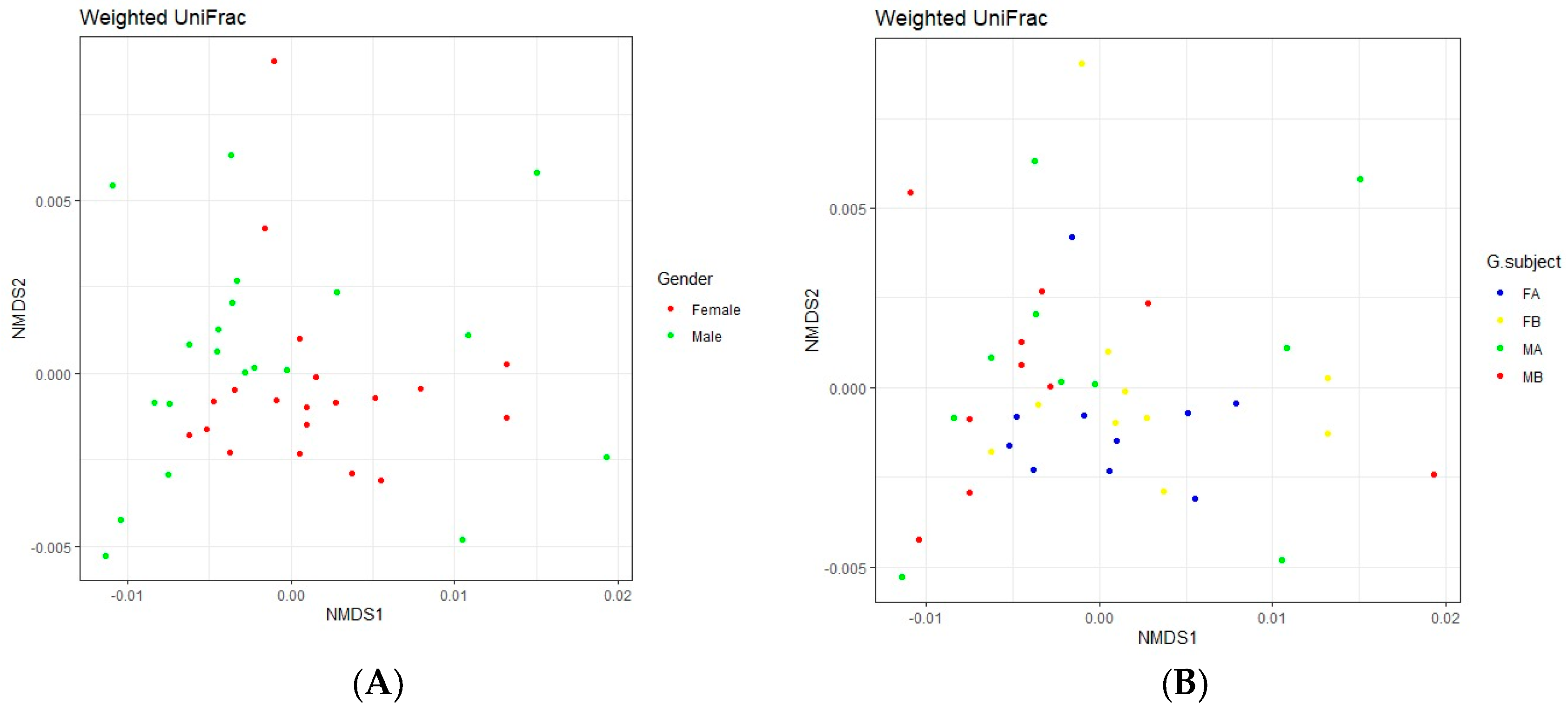

3.3.4. Beta Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ursell, L.K.; Metcalf, J.L.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. Defining the Human Microbiome. Nutr Rev 2012, 70, S38–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Abu-Ali, G.; Huttenhower, C. The Healthy Human Microbiome. Genome Med 2016, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Segre, J.A. The Human Microbiome: Our Second Genome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2012, 13, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, P.N.; Deshmukh, R. Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2019, 23, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghi, L.; DiMassa, V.; Harrington, A.; Lynch, S.V.; Kapila, Y.L. The Oral Microbiome: Role of Key Organisms and Complex Networks in Oral Health and Disease. Periodontol 2000 2021, 87, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santonocito, S.; Giudice, A.; Polizzi, A.; Troiano, G.; Merlo, E.M.; Sclafani, R.; Grosso, G.; Isola, G. A Cross-Talk between Diet and the Oral Microbiome: Balance of Nutrition on Inflammation and Immune System’s Response during Periodontitis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, T. Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease: Maintaining a Healthy, Balanced Ecosystem and Reversing Dysbiosis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, F.Q.; Almeida-da-Silva, C.L.C.; Huynh, B.; Trinh, A.; Liu, J.; Woodward, J.; Asadi, H.; Ojcius, D.M. Association between Periodontal Pathogens and Systemic Disease. Biomed J 2019, 42, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matayoshi, S.; Tojo, F.; Suehiro, Y.; Okuda, M.; Takagi, M.; Ochiai, M.; Kadono, M.; Mikasa, Y.; Okawa, R.; Nomura, R.; et al. Effects of Mouthwash on Periodontal Pathogens and Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshipura, K.J.; Muñoz-Torres, F.J.; Morou-Bermudez, E.; Patel, R.P. Over-the-Counter Mouthwash Use and Risk of Pre-Diabetes/Diabetes. Nitric Oxide 2017, 71, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, F.; Gu, H.; Wei, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, H. Comparative Evaluation of the Salivary and Buccal Mucosal Microbiota by 16S RRNA Sequencing for Forensic Investigations. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, W.G.; Prosdocimi, E.M. Profiling of Oral Bacterial Communities. J Dent Res 2020, 99, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.L.; Morton, J.T.; Dinis, M.; Alvarez, R.; Tran, N.C.; Knight, R.; Edlund, A. Deep Metagenomics Examines the Oral Microbiome during Dental Caries, Revealing Novel Taxa and Co-Occurrences with Host Molecules. Genome Res 2021, 31, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Işcan, G.; Kirimer, N.; Kürkcüoğlu, M.; Başer, K.H.C.; Demirci, F. Antimicrobial Screening of Mentha Piperita Essential Oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3943–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Takizawa, T. Screening of the Antibacterial Effects of a Variety of Essential Oils on Respiratory Tract Pathogens, Using a Modified Dilution Assay Method. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2001, 7, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soković, M.; Glamočlija, J.; Marin, P.D.; Brkić, D.; Griensven, L.J.L.D. van Antibacterial Effects of the Essential Oils of Commonly Consumed Medicinal Herbs Using an In Vitro Model. Molecules 2010, 15, 7532–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, S.; Takizawa, T.; Yamaguchi, H. Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils and Their Major Constituents against Respiratory Tract Pathogens by Gaseous Contact. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2001, 47, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandava, K.; Batchu, U.R.; Kakulavaram, S.; Repally, S.; Chennuri, I.; Bedarakota, S.; Sunkara, N. Design and Study of Anticaries Effect of Different Medicinal Plants against S.Mutans Glucosyltransferase. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019, 19, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitsiou, E.; Mitropoulou, G.; Spyridopoulou, K.; Tiptiri-Kourpeti, A.; Vamvakias, M.; Bardouki, H.; Panayiotidis, M.; Galanis, A.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Chlichlia, K.; et al. Phytochemical Profile and Evaluation of the Biological Activities of Essential Oils Derived from the Greek Aromatic Plant Species Ocimum Basilicum, Mentha Spicata, Pimpinella Anisum and Fortunella Margarita. Molecules 2016, 21, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, H.; Osawa, K.; Yasuda, H.; Hamashima, H.; Arai, T.; Sasatsu, M. Inhibition by the Essential Oils of Peppermint and Spearmint of the Growth of Pathogenic Bacteria. Microbios 2001, 106 Suppl 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mimica-Dukić, N.; Bozin, B.; Soković, M.; Mihajlović, B.; Matavulj, M. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Three Mentha Species Essential Oils. Planta Med 2003, 69, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, K.; Crown, A.; Carlson, R. Multidrug and Pan-Antibiotic Resistance—The Role of Antimicrobial and Synergistic Essential Oils: A Review. Nat Prod Commun 2020, 15, 1934578X2096259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, D.; Licker, M.; Alexa, E.; Popescu, I.; Jianu, C.; Buda, V.; Dehelean, C.A.; Ghiulai, R.; Horhat, F.; Horhat, D.; et al. <p>Evaluation of Essential Oil Obtained from <em>Mentha×piperita</Em> L. against Multidrug-Resistant Strains</P>. Infect Drug Resist. [CrossRef]

- Jeyakumar, E.; Lawrence, R.; Pal, T. Comparative Evaluation in the Efficacy of Peppermint (Mentha Piperita) Oil with Standards Antibiotics against Selected Bacterial Pathogens. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2011, 1, S253–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotan, R.; Kordali, S.; Cakir, A. Screening of Antibacterial Activities of Twenty-One Oxygenated Monoterpenes. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2007, 62, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraji, A.; Yazdanpanah, S.; Alizadeh, F.; Mirzamohammadi, S.; Ghasemi, Y.; Pakshir, K.; Yang, Y.; Zomorodian, K. Screening the Antifungal Activities of Monoterpenes and Their Isomers against Candida Species. J Appl Microbiol 2020, 129, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghgoo, R.; Abbasi, F. Evaluation of the Use of a Peppermint Mouth Rinse for Halitosis by Girls Studying in Tehran High Schools. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2013, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyldgaard, M.; Mygind, T.; Meyer, R.L. Essential Oils in Food Preservation: Mode of Action, Synergies, and Interactions with Food Matrix Components. Front Microbiol 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Park, S.J.; Yang, W.M. Inhalation of Essential Oil from Mentha Piperita Ameliorates PM10-Exposed Asthma by Targeting IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 Pathway Based on a Network Pharmacological Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghodrati, M.; Farahpour, M.R.; Hamishehkar, H. Encapsulation of Peppermint Essential Oil in Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: In-Vitro Antibacterial Activity and Accelerative Effect on Infected Wound Healing. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2019, 564, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarresi, M.; Farahpour, M.-R.; Baradaran, B. Topical Application of Mentha Piperita Essential Oil Accelerates Wound Healing in Infected Mice Model. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Wahab, N.; Warikoo, R. Bioefficacy of Mentha Piperita Essential Oil against Dengue Fever Mosquito Aedes Aegypti L. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2011, 1, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadollahi, A.; Khoobdel, M.; Zahraei-Ramazani, A.; Azarmi, S.; Mosawi, S.H. Effectiveness of Plant-Based Repellents against Different Anopheles Species: A Systematic Review. Malar J 2019, 18, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Malik, A. Antimicrobial Action of Essential Oil Vapours and Negative Air Ions against Pseudomonas Fluorescens. Int J Food Microbiol 2010, 143, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scartazzini, L.; Tosati, J.V.; Cortez, D.H.C.; Rossi, M.J.; Flôres, S.H.; Hubinger, M.D.; Di Luccio, M.; Monteiro, A.R. Gelatin Edible Coatings with Mint Essential Oil (Mentha Arvensis): Film Characterization and Antifungal Properties. J Food Sci Technol 2019, 56, 4045–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.K.; Goswami, P.; Verma, R.S.; Padalia, R.C.; Chauhan, A.; Singh, V.R.; Darokar, M.P. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Bergamot-Mint (Mentha Citrata Ehrh.) Essential Oils Isolated from the Herbage and Aqueous Distillate Using Different Methods. Ind Crops Prod 2016, 91, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoussi, M.; Noumi, E.; Trabelsi, N.; Flamini, G.; Papetti, A.; De Feo, V. Mentha Spicata Essential Oil: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities against Planktonic and Biofilm Cultures of Vibrio Spp. Strains. Molecules 2015, 20, 14402–14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decarlo, A.; Johnson, S.; Ouédraogo, A.; Dosoky, N.S.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical Composition of the Oleogum Resin Essential Oils of Boswellia Dalzielii from Burkina Faso. Plants 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzychczy-Sroka, B.; Talaga-Ćwiertnia, K.; Sroka-Oleksiak, A.; Gurgul, A.; Zarzecka-Francica, E.; Ostrowski, W.; Kąkol, J.; Drożdż, K.; Brzychczy-Włoch, M.; Zarzecka, J. Standardization of the Protocol for Oral Cavity Examination and Collecting of the Biological Samples for Microbiome Research Using the Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Own Experience with the COVID-19 Patients. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.J.S.; Parmar, V.; Blaser, M.J. Assessing Saliva Microbiome Collection and Processing Methods. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caselli, E.; Fabbri, C.; D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Bassi, C.; Mazzacane, S.; Franchi, M. Defining the Oral Microbiome by Whole-Genome Sequencing and Resistome Analysis: The Complexity of the Healthy Picture. BMC Microbiol 2020, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation: Preparing 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Amplicons for the Illumina MiSeq System. Part No. 15044223 Rev B. Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA. Available online: https://www.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina-support/documents/documentation/chemistry_documentation/16s/16s-metagenomic-library-prep-guide-15044223-b.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, A.; Park, J.; Chen, Y.-A.; Kawashima, H.; Mizuguchi, K. Impact of Quality Trimming on the Efficiency of Reads Joining and Diversity Analysis of Illumina Paired-End Reads in the Context of QIIME1 and QIIME2 Microbiome Analysis Frameworks. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSantis, T.Z.; Hugenholtz, P.; Larsen, N.; Rojas, M.; Brodie, E.L.; Keller, K.; Huber, T.; Dalevi, D.; Hu, P.; Andersen, G.L. Greengenes, a Chimera-Checked 16S RRNA Gene Database and Workbench Compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72, 5069–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-High-Throughput Microbial Community Analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq Platforms. ISME J 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, W. Application of High-Throughput Sequencing in Understanding Human Oral Microbiome Related with Health and Disease. Front Microbiol 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shade, A.; Handelsman, J. Beyond the Venn Diagram: The Hunt for a Core Microbiome. Environ Microbiol 2012, 14, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaura, E.; Keijser, B.J.; Huse, S.M.; Crielaard, W. Defining the Healthy “Core Microbiome” of Oral Microbial Communities. BMC Microbiol 2009, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, M.; Ojcius, D.M.; Yilmaz, Ö. The Oral Microbiota: Living with a Permanent Guest. DNA Cell Biol 2009, 28, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aas, J.A.; Paster, B.J.; Stokes, L.N.; Olsen, I.; Dewhirst, F.E. Defining the Normal Bacterial Flora of the Oral Cavity. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 5721–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crielaard, W.; Zaura, E.; Schuller, A.A.; Huse, S.M.; Montijn, R.C.; Keijser, B.J. Exploring the Oral Microbiota of Children at Various Developmental Stages of Their Dentition in the Relation to Their Oral Health. BMC Med Genomics 2011, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.; Kong, J.; Jia, P.; Wei, C.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Z.; Huang, W.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Xiang, C. Analysis of Oral Microbiota in Children with Dental Caries by PCR-DGGE and Barcoded Pyrosequencing. Microb Ecol 2010, 60, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musić, L.; Par, M.; Peručić, J.; Badovinac, A.; Plančak, D.; Puhar, I. Relationship Between Halitosis and Periodontitis: A Pilot Study. Acta Stomatol Croat 2021, 55, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Hong, J.-Y. Oral Microbiome as a Co-Mediator of Halitosis and Periodontitis: A Narrative Review. Frontiers in Oral Health 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, S.; Edlund, M.; Claesson, R.; Carlsson, J. The Formation of Hydrogen Sulfide and Methyl Mercaptan by Oral Bacteria. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1990, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bayati, F.A. Isolation and Identification of Antimicrobial Compound from Mentha Longifolia L. Leaves Grown Wild in Iraq. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2009, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, C.; Zhang, N.; Peng, Y.; Ma, Y.; Gu, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Menthone Exerts Its Antimicrobial Activity Against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus by Affecting Cell Membrane Properties and Lipid Profile. Drug Des Devel Ther 2023, Volume 17, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Morales, J.; Mark Welch, J.L.; Dewhirst, F.E.; Borisy, G.G. Site-Specialization of Human Oral Gemella Species. J Oral Microbiol 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyoshi, T.; Oge, S.; Nakata, S.; Ueno, Y.; Ukita, H.; Kousaka, R.; Miura, Y.; Yoshinari, N.; Yoshida, A. Gemella Haemolysans Inhibits the Growth of the Periodontal Pathogen Porphyromonas Gingivalis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 11742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Welch, J.L.; Rossetti, B.J.; Rieken, C.W.; Dewhirst, F.E.; Borisy, G.G. Biogeography of a Human Oral Microbiome at the Micron Scale. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, E791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esberg, A.; Barone, A.; Eriksson, L.; Lif Holgerson, P.; Teneberg, S.; Johansson, I. Corynebacterium Matruchotii Demography and Adhesion Determinants in the Oral Cavity of Healthy Individuals. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Participant ID |

Gender | Age | Teeth n. |

Oral-Hygiene Devices at home |

City of residency |

| 1 | Male | 23 | 32 | None | Ismailia |

| 3 | Male | 23 | 32 | Floss | Cairo |

| 5 | Male | 24 | 32 | None | Cairo |

| 6 | Male | 23 | 30 | None | Ismailia |

| 7 | Male | 23 | 32 | None | Sinai |

| 8 | Male | 22 | 32 | None | Ismailia |

| 9 | Male | 22 | 31 | None | Ismailia |

| 10 | Male | 23 | 31 | None | Ismailia |

| 11 | Female | 21 | 32 | None | Eltour |

| 12 | Female | 21 | 32 | None | Suez |

| 13 | Female | 21 | 32 | None | Suez |

| 16 | Male | 21 | 32 | None | Suez |

| 17 | Female | 21 | 32 | None | Suez |

| 19 | Female | 21 | 31 | None | Suez |

| 20 | Female | 21 | 32 | None | Suez |

| 21 | Male | 23 | 32 | Floss | Ismailia |

| 22 | Female | 25 | 32 | None | Ismailia |

| 23 | Female | 22 | 32 | None | Ismailia |

| 24 | Female | 25 | 31 | Floss | Suez |

| 25 | Female | 33 | 32 | Floss | Ismailia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).