Introduction

In Quebec, healthcare is essential not only for individual well-being but also as a cornerstone of economic prosperity. The provision of health services plays a critical role in enhancing quality of life and generating employment, accounting for nearly 40% of provincial public spending as of 2020. This increase is partly due to the disproportionate rise in compensation among medical professionals, as noted by Hébert et al. (2017). In peripheral regions, healthcare serves as a primary employment source, significantly influencing the economic landscape (Bailly and Périat, 2003). This trend reinforces a hospital-centric approach through the establishment of senior residences and new medical units in regional and non-local hospitals. Additionally, reforms in the 2000s led to a notable increase in administrative personnel at the expense of clinical staff, resulting in a 5% decrease in clinical positions (Hébert, 2013). Consequently, one in every six positions in the healthcare sector now involves administrative duties.

The current socio-political context, marked by demographic aging, health assumes paramount importance. This demographic shift presents unique challenges for rural communities, which often face limited access to healthcare services (Arpin-Simonetti, 2018), potentially hindering their development. Health challenges prevalent in these regions include a higher incidence of conditions such as diabetes and elevated mortality rates for various diseases compared to urban areas, including lung cancer, ischemic heart disease, strokes, chronic pulmonary diseases, mental disorders (with increased suicide risk, particularly among males), road accidents, and infant mortality (INSPQ, 2019).

Access to quality healthcare is a fundamental human right and a critical determinant of well-being, significantly impacting population health and welfare (Evans et al., 1994). Rural areas worldwide face significant challenges in accessing essential healthcare services. Numerous studies confirm the connection between rural living and reduced access to, and utilization of, healthcare services (Hicks, 1991; Farrington and Farrington, 2005; Hausdorf et al., 2008; Al-Taiar et al., 2010).

Primary care services are vital for population health by providing disease management and prevention, health advocacy, neonatal care, and end-of-life support (Bourgueil et al., 2021). Studies have shown that inequities in accessing quality healthcare services can exacerbate health disparities (Gatrell, 2005; Thompson, 2011; Wang, 2012). Therefore, addressing these inequities is a primary goal for policymakers overseeing healthcare administration, aiming to enhance quality of life for all individuals.

In Quebec, significant disparities in healthcare provision are evident across the province. Official government statistics show that approximately 90% of rural and remote residents can reach a general practitioner or a Local Community Service Center (CLSC) within a 15-minute drive (INSPQ, 2009). However, statistics from 2019 indicate that 71% of emergency room visits were non-urgent, with 72% of patients having assigned doctors, suggesting inefficiencies in healthcare utilization (Fleury, 2019). The availability of healthcare providers diminishes notably from urban to rural areas, particularly affecting the availability of general practitioners, leading to a lack of physicians in many rural regions, especially in northern and eastern Quebec.

Contemporary public policies often prioritize the allocation of healthcare resources to urban centers, frequently at the expense of rural areas. This prioritization is evident in the concentration of major hospital facilities in urban hubs such as Montreal and the preferential placement of elderly care residences adjacent to regional hospital complexes rather than local ones. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 revealed the intrinsic limitations of this centralized healthcare service model. This revelation is particularly significant within the realm of regional development, where disparities in healthcare accessibility can exacerbate preexisting societal inequities and impede broader socio-economic advancement.

Nevertheless, existing scholarly investigations frequently treat rural areas as homogenous entities, neglecting nuanced variations in local conditions. There is a pressing need for a more granular approach, necessitating the categorization of rural areas into sub-regions based on differences in geographic size, population density, and road network accessibility. Such an approach would facilitate a more precise understanding of the intricacies underlying rural healthcare dynamics, enabling tailored interventions and policy prescriptions aimed at mitigating disparities and fostering equitable healthcare access across diverse rural landscapes.

This text underscores the vital role of health in personal welfare and economic development, with a particular focus on the obstacles encountered by rural communities in securing healthcare. While some improvements have been made, the ongoing scarcity of healthcare practitioners in rural locales emphasizes the immediate need for policy reforms. The COVID-19 crisis further unveiled the inadequacies of centralized healthcare systems, necessitating a reconsideration of strategies to ensure equal access in all territories. Addressing these disparities requires targeted policy interventions and further research to understand the specific needs of different rural areas, ensuring equitable healthcare access and fostering socio-economic growth. Promoting a sophisticated comprehension of rural healthcare demands and advancing regional growth strategies is key to cultivating healthcare parity and socio-economic progression.

Challenges in Rural Healthcare Access

Rural areas confront unique challenges that significantly impede healthcare accessibility. While geographic access plays a pivotal role, it's not the sole determining factor, particularly for secondary healthcare services. Often, urban-centric analyses overlook the specific hurdles encountered by demographic groups such as the elderly, children, and individuals with disabilities. Moreover, current performance indicators often fall short in accurately gauging access to family doctors or assessing the effectiveness of incentives for primary care physicians, partly due to an overreliance on patient registration rates. These challenges intersect, creating complex barriers to healthcare access and resulting in disparities in health outcomes between rural and urban populations. A 2003 study (ASSSM, 2003) found that 25% of Quebec residents seeking primary care faced such obstacles, primarily due to accessibility issues. A decade later, in 2013, nearly one-third of Canadians aged 15 and above reported difficulties accessing healthcare services. Ensuring adequate access to primary care is crucial, as it is associated with an increase in life expectancy of two years (Martinez et al., 2004). Notably, individuals living in rural areas have a life expectancy two years shorter than their urban counterparts.

Amidst these challenges, there has been a consistent rise in waiting times for appointments with primary care physicians, escalating from 477 days in 2019 to 599 days in 2021. Despite 82% of Quebec's population being affiliated with a primary care physician, approximately 20% encounter barriers to access due to prolonged waiting lists. Such hurdles may compel underserved populations to accept their predicament, leading to diminished rates of examinations and screening tests.

In the rural and remote regions of Quebec, the provision of adequate healthcare services remains a formidable challenge. These areas grapple with shortages of healthcare professionals due to less favorable working conditions and harsh environmental factors. Compounded by constraints such as restricted road infrastructure and sparse public transport networks, individuals lacking private transportation options face considerable difficulties in accessing healthcare services. Addressing these issues necessitates tailored interventions that consider the unique needs and circumstances of rural communities. Numerous studies have examined the gap in healthcare access between urban and rural areas, revealing lower accessibility in rural regions (Laditka et al., 2009; McGrail and Humphreys, 2009). While some research specifically investigates the impact of geographical distance on accessibility, others highlight a link between increased rurality and higher hospitalization rates, as well as a lower likelihood of having a physician in remote areas. Disparities also vary depending on territorial classifications, with rural settings experiencing reduced availability of primary care physicians.

Further impediments encountered by rural and remote areas exacerbate the challenges in healthcare access. Insufficient road infrastructure poses constraints on the availability of health services, with transportation accessibility directly impacting ease of access (Girard, 2006; Starfield et al., 2005). In many rural regions, automobiles serve as the primary mode of transportation for accessing healthcare services, due to the absence of public transportation networks. Healthcare access is intricately linked with transportation availability and social vulnerability. While much attention has been directed towards healthcare accessibility in urban environments, several studies have explored this issue in rural settings, consistently affirming the correlation between rural locations and diminished accessibility to care.

Available data underscores significant disparities in the health statuses of urban and rural residents. Emergency services often serve as the primary healthcare option in remote areas, indicating a shortage of primary care physicians. Despite rural populations generally experiencing poorer health outcomes, they are not consistently recognized as vulnerable by urban-centric researchers. For instance, a report on primary medical service access overlooks issues related to geographic isolation in rural areas. Healthcare access in rural areas is hindered by geographical remoteness, inadequate infrastructure, workforce shortages, financial limitations, and socio-cultural barriers. Despite efforts to address these issues, gaps persist, leading to an overreliance on emergency services and a lack of precise performance metrics. A comprehensive understanding of these challenges is essential for crafting interventions that bridge the healthcare access gap and ensure equitable health outcomes for all citizens.

Understanding Territorial Equity

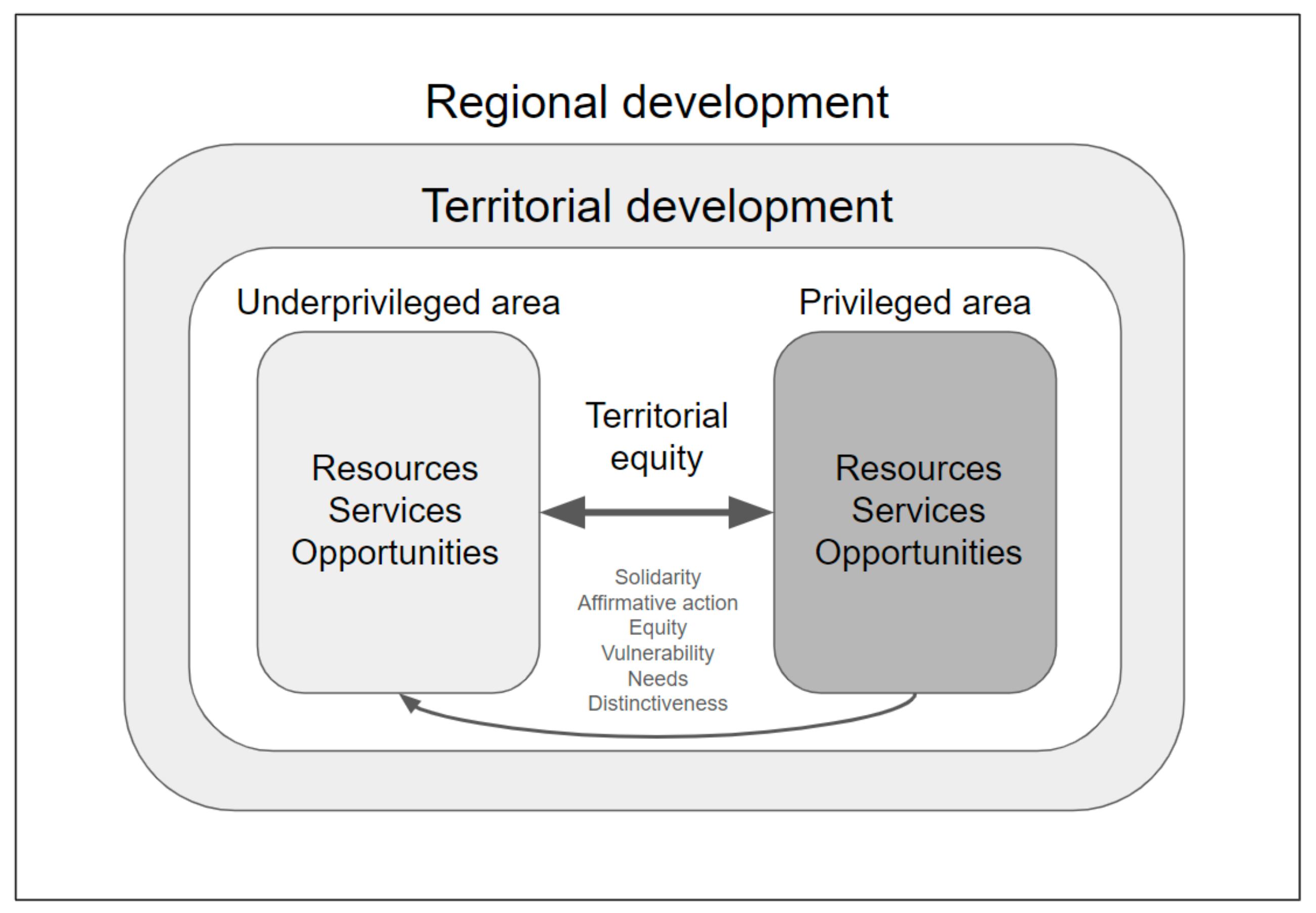

Territorial equity, essential for promoting balanced development, social justice, and sustainable growth across geographical regions, embodies a spatial framework shaped by societal entities to foster sustenance, progress, and communal welfare (Escobar, 2008). It embraces the notion of "well-being at home and well-being together," promoting social cohesion and interaction through shared responsibility and solidarity (Putnam, 2000). Decisions made in the name of territory influence compromises, sustainability efforts, and highlight its multidimensional nature (Harvey, 1989), positioning territorial development as an entrenched project in tangible, inhabited spaces, requiring a comprehensive understanding of territory as a reservoir, a challenge, and a consequence of developmental endeavors (Brenner, 2009), facilitating interactions between agents and structures, leveraging diverse territorial attributes for economic advancement (Scott, 2001).

Territorial development, reliant on territorial distinctiveness, creates disparities in the distribution of resources and fosters tensions despite egalitarian principles (Martin & Sunley, 2006). Yet, adopting a territorial development approach in the early 2000s proved effective in countering negative regional stereotypes, initiating a positive developmental cycle (Moulaert & Nussbaumer, 2005; Fournis, 2012), maximizing the environment's inherent potential. Territorial equity aims to rectify inequalities by ameliorating underprivileged territories through spatial planning, development initiatives, and social policies, rather than relying solely on public expenditure and affirmative action (Rodríguez-Pose & Tijmstra, 2019), making spatial action integral to ensuring social equity, closely linked with territorial equity (Allmendinger, 2009).

Territorial equity, referring to the fair distribution of resources, opportunities, and services across geographical regions, aims to mitigate imbalances and promote equitable development (Barca, McCann, & Rodríguez-Pose, 2012). Assessments of equity reveal the diverse impacts of factors like urban proximity on service accessibility and resource allocation, highlighting economic disparities stemming from variations in population density (Duranton & Rodríguez-Pose, 2004). Unlike spatial equity, which focuses on location, territorial equity addresses territorially localized inequalities (Pike & Tomaney, 2010), encompassing principles of solidarity, equal developmental opportunities, and affirmative action (Hudson, 2005).

However, development often exhibits asymmetry, with competitiveness and regulatory measures becoming increasingly crucial due to limited financial and political resources (OECD, 2018). Rooted in Rawlsian principles, territorial equity prioritizes the needs of the least advantaged and advocates for policies of affirmative action in favor of marginalized territories (Keeley, 2012), aiming to establish a framework that provides equitable access to opportunities such as employment and services (Healey, 1997). Territorial equity aims to reduce spatial development disparities by directing resources to the least advantaged territories, considering factors like resource availability, developmental progress, transportation access, and vulnerability to poverty (Rigby & Essletzbichler, 2002), providing a nuanced understanding of disparities within and between communities, impacting their developmental trajectories (Smith & Easterly, 2007).

Figure 1.

Territorial equity and regional development.

Figure 1.

Territorial equity and regional development.

Development, whether sustainable or not, unfolds within, for, through, and alongside territories, inherently concerning the development of territories, whether on a global scale or within territorially anchored societies or activities (Scott, 1998). While ideas may originate globally, action is typically localized, regional, or national, confined within well-defined territorial boundaries (Brenner & Schmid, 2015). Moreover, considering future generations necessitates the involvement of current territorially-bound generations (Bourdieu, 1977).

At a national or regional scale, development can lead to spatial disparities, with certain regions bearing the burden of progress (Pike et al., 2015). Sustainability, while desirable, proves elusive universally, raising questions of equity (Leach et al., 2018). The concept of "territorial sacrifices" highlights areas that contribute significantly to broader territories but disproportionately suffer from ensuing crises, as seen in former industrial regions undergoing conversion in Europe (Smith, 2008).

Promoting universally applicable norms encounters challenges when implementing them within specific geographic contexts, potentially conflicting with national sovereignty (Bhagwati, 2004). Sustainability imperatives may challenge the relevance of territorial considerations, particularly regarding issues like atmospheric rights or biocapacity ownership (Gardiner, 2004). In such cases, human-centric concerns often supersede territorial inequalities (Dryzek, 2013).

In healthcare, achieving territorial equity involves ensuring equitable access to essential medical services, preventive care, and health infrastructure for all individuals, regardless of their location (Levesque et al., 2013). This requires a comprehensive approach addressing geographical, social, economic, and cultural determinants shaping health outcomes in rural areas (WHO, 2018). Healthcare systems influenced by market dynamics often lead to uneven distribution of medical professionals, exacerbating territorial disparities in healthcare access and contributing to health inequality (Hartwig, 2017).

Health disparities arise from various factors, including genetic predispositions, environmental influences, and individual preferences (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2006). However, metrics like the Gini coefficient oversimplify complex realities (Deaton & Zaidi, 2002). Social inequalities often exhibit spatial patterns, with variations in distribution across different environments (Galster et al., 2010). Geographical health inequalities can be analyzed compositionally, considering individual characteristics, or contextually, focusing on local attributes (Pampalon et al., 2009).

The environment encompasses economic, social, institutional, and physical dimensions, influencing resource distribution across territories (McMichael, 2000). In conclusion, territorial equity plays a crucial role in fostering balanced development, social justice, and sustainable growth within defined spatial boundaries. Territorial development, grounded in tangible spaces and local contexts, requires a nuanced understanding of territory's role in economic dynamics. Targeted interventions are needed to address spatial inequalities and enhance opportunities for all. Achieving territorial equity in healthcare demands a holistic approach considering geographic, socio-economic, and infrastructural factors. The discourse highlights ongoing challenges in realizing territorial equity's transformative potential in creating a more just and sustainable society.

Implications for Regional Development

The relationship between regional development and healthcare access is intricate and mutually reinforcing (Bloland et al., 2012). Regional development has the potential to enhance healthcare accessibility through various means, including infrastructure improvement, human resource development, technological advancement, and governance enhancement. Conversely, accessible healthcare contributes to population health, diminishes economic burdens, and stimulates regional growth (Lohr & Steinwachs, 2002).

Nonetheless, significant challenges persist, particularly in rural and peripheral areas (Ricketts, 2000). These areas often grapple with healthcare provider shortages, unequal service distribution, workforce mobility issues, and various barriers such as geographical, financial, cultural, linguistic, and organizational obstacles (Pathman et al., 2004). Addressing these challenges necessitates not only addressing healthcare provision but also promoting preventive measures, health promotion, managing chronic conditions, and adapting to various demographic, epidemiological, technological, climatic, and societal changes (Dussault & Franceschini, 2006).

The lack of equitable healthcare access not only affects individual health outcomes but also hampers broader regional development objectives. A healthy population is crucial for sustainable economic progress, supporting a productive workforce and mitigating healthcare-related economic strains. Equitable healthcare access can attract investments, drive innovation, and enhance overall quality of life in rural regions (Basu, 2020). Therefore, prioritizing healthcare as a driver of regional development is essential for policymakers aiming to foster inclusive growth and resilient communities.

The relationship between health and economic prosperity is well-documented, with numerous studies highlighting their interdependence (Weisbrod and Helminiak, 1977; Audibert, 1986; Audibert, 1997a and 1997b; Girardin et al., 2004). Population health significantly influences economic performance, as evidenced by positive correlations between life expectancy and economic outcomes (Cuddington & Hancock, 1994; Sach & Warner, 1997; Bloom & Malaney, 1998; Arora, 2001; Acemoglu & Johnson, 2007; Bloom & Finlay, 2009). The healthcare sector plays a pivotal role in shaping communities and regional development, extending beyond individual care to reconfigure social and economic structures (Gostin et al., 2019).

Efforts to address the challenges of equitable healthcare access in rural areas require targeted policies that promote healthcare workforce retention, infrastructure improvement, and reduction of barriers to care (WHO, 2018). Recognizing health as an investment in human capital is crucial, as optimal health enhances productivity and educational outcomes (Bloom and Canning, 2008; Sullivan et al., 2010).

However, assessing the economic implications of health encounters various challenges due to the complex nature of health and its overlaps with other factors such as education, environment, and culture (Fourcade and Von Lennep, 2016). Nonetheless, access to health services emerges as a critical component of regional development, influencing quality of life, disease prevention and treatment, and public health promotion (Boisvert et al., 2019).

In summary, the relationship between regional development and healthcare access is symbiotic. While regional development efforts aim to enhance healthcare accessibility, equitable healthcare access, in turn, contributes to regional prosperity by improving population health and fostering drivers of development like employment and innovation. Overcoming obstacles to equitable healthcare access is essential for inclusive growth and resilient community development, underscoring the pivotal role of accessible healthcare services in shaping prosperous and healthy societies.

Strategies for Promoting Territorial Equity in Healthcare

Addressing territorial equity in healthcare necessitates tailored strategies and collaborative efforts among diverse stakeholders to ensure accessible and quality healthcare services for all regions. Concurrently, fostering collaboration, partnerships, dialogues, consultations, co-creations, co-productions, and co-evaluations among the diverse stakeholders involved in regional development and healthcare accessibility is crucial.

Zuindeau (2005) delineates two strategic pathways for achieving territorial equity: internal interventions that align local production and consumption patterns with sustainability goals, and global institutional dynamics that realign international market mechanisms with sustainability objectives. These pathways illustrate the multifaceted nature of addressing territorial equity, highlighting the need for both local and global interventions to create sustainable healthcare systems.

Investment in healthcare infrastructure, including facilities construction and enhancement, telemedicine networks, and transportation systems, is pivotal for improving accessibility in rural areas (World Health Organization, 2020). Incentivizing healthcare professionals' recruitment and retention in rural areas through training programs and innovative staffing models is essential for addressing healthcare shortages (Henderson, 2002). Empowering local communities to participate in healthcare decision-making fosters collaborations between healthcare providers and community organizations, ensuring that healthcare services align with local needs (Foster-Fishman et al., 2010). These collaborative efforts serve as integral components of territorial equity in healthcare, facilitating the development of inclusive and sustainable healthcare systems.

Furthermore, leveraging digital health technologies, mobile applications, and data analytics can facilitate remote healthcare services and improve health information exchange in rural settings (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2017). The integration of technology into healthcare delivery models underscores the importance of innovation in addressing healthcare access disparities, particularly in underserved regions.

The E2SFCA method (Enhanced Two-Step Floating Catchment Area) plays a crucial role in identifying regions with healthcare access deficits, enabling optimized resource allocation to enhance equity. This method has proven effective in uncovering disparities in medical access, particularly in rural areas (Wang et al., 2018). Recent studies, such as Simoneau's (2023) research on access to general practitioners in rural regions of Quebec, demonstrate the effectiveness of advanced methods like the E2SFCA in uncovering disparities in medical access. These findings underscore the method's potential to drive improvements in territorial equity and advocate for its adoption as a tool for enhancing healthcare accessibility across diverse regional settings.

Achieving territorial equity in healthcare demands a multifaceted approach encompassing infrastructure investment, workforce development, community engagement, policy innovation, and technological integration. By leveraging innovative methodologies like the E2SFCA, stakeholders can better identify and address healthcare access deficits, ultimately fostering inclusive and sustainable regional development.

Conclusion

Promoting equitable healthcare access in rural areas is paramount for advancing regional development and ensuring the well-being of all populations. Not only does equitable healthcare access improve individual health outcomes, but it also fosters a healthy and productive population, thereby supporting regional prosperity. By addressing healthcare disparities and implementing targeted interventions, policymakers can establish a robust healthcare framework characterized by equity, inclusivity, and resilience. Collaboration among stakeholders from various sectors is vital for devising and implementing sustainable strategies that prioritize the health and dignity of every individual, regardless of their location.

Building on this foundation, the intricate relationship between regional development and healthcare accessibility highlights their mutual dependence in fostering thriving communities. Regional development initiatives optimize resource usage and administrative structures to enhance healthcare access, while equitable healthcare provision drives regional prosperity by improving public health and supporting key development factors like employment and innovation. Recognizing this interplay between health and economic performance underscores the importance of prioritizing accessible healthcare to sustain regional development efforts.

However, rural areas face significant challenges in achieving equitable healthcare access, necessitating targeted interventions to overcome deficiencies and geographical barriers. These areas often grapple with shortages of healthcare providers, inadequate infrastructure, and geographical barriers that hinder access to quality care. Urgent action is required, emphasizing tailored strategies, collaboration, and innovative methodologies like the E2SFCA method to refine resource distribution and strengthen healthcare equity, especially in underserved rural areas. The E2SFCA method facilitates the identification of healthcare access deficits, enabling optimized resource allocation to enhance equity, particularly in underserved rural areas.

Investing in healthcare infrastructure and telemedicine networks holds promise for improving accessibility for rural populations. Incentivizing the recruitment and retention of healthcare professionals in rural areas through training programs and financial incentives is crucial. Engaging local communities in healthcare decision-making processes fosters collaboration and ensures that services meet local needs. Looking ahead, embracing holistic approaches and innovative solutions is essential to address healthcare access disparities and promote sustainable regional development.

Ensuring equitable healthcare access is a cornerstone of the well-being and prosperity of all communities. Through collaborative action and innovative solutions, policymakers can pave the way for a future where healthcare access is equitable, laying the foundation for sustainable development and inclusive growth.

References

- ACEMOGLU, D., & JOHNSON, S. (2007). Disease and development: The effect of life expectancy on economic growth. Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 925-985.

- AGENCE DE LA SANTÉ ET DES SERVICES SOCIAUX DE MONTRÉAL. (2003). Besoins et difficultés d’accès aux services de premier contact, Canada, Québec, Montréal - Analyse des données de l’enquête sur l’accès aux services de santé, 2003. Available online: https://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/fichiers/2003/03-704-01.pdf.

- ALLMENDINGER, P. (2009). Rescaling Territorial Governance: The Case of Territorial Development Agencies in England. Regional Studies, 43(1), 33-45.

- AL-TAIAR, A., CLARK, A., LONGENECKER, J. C., & WHITTY, C. J. M. (2010). Physical accessibility and utilization of health services in Yemen. International Journal of Health Geographics, 9, 38. [CrossRef]

- ARNSTEIN, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224.

- ARPIN-SIMONETTI, E. (2018). Développement régional: Un Québec en morceaux. Relations, 798, 14-16.

- ARORA, S. (2001). Health, Human Productivity, and Long- Term Economic Growth. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(4), 1137-1176.

- AUDIBERT, M. (1986). Agricultural non-wage production and health status: A case study in a tropical environment. Journal of Development Economics, 24(2), 275-291.

- AUDIBERT, M. (1997a). La cohésion sociale est-elle un facteur de l’efficience technique des exploitations agricoles en économie de subsistance ? Revue d’économie du développement, 5(3), 69–90. [CrossRef]

- AUDIBERT, M. (1997b). Technical inefficiency effects among paddy farmers in the villages of the “Office du Niger”, Mali, West Africa. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 8(4), 379-394.

- AUDIBERT, M., ET AL. (1999). Rôle du paludisme dans l’efficience technique des producteurs de coton du nord de la Côte-d’Ivoire. Revue d’économie du développement, 7(4), 121–148. [CrossRef]

- AUDIBERT, M., MATHONNAT, J., & HENRY, M. C. (2003). Malaria and property accumulation in rice production systems in the savannah zone of Cote d’Ivoire. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 8(5), 471–483. [CrossRef]

- AUDIBERT, M., BRUN, J. F., MATHONNAT, J., & HENRY, M. C. (2009). Effets économiques du paludisme sur les cultures de rente : L’exemple du café et du cacao en Côte d’Ivoire. Revue d’économie du développement, 17, 145. [CrossRef]

- BÄCKSTRAND, K., (2006). Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. European environment, 16(5), pp.290-306.

- BAILLY, A., & PÉRIAT, M. (2003). Activités de santé et développement régional : Une approche médicométrique. Géocarrefour, 78(3), 235–8. [CrossRef]

- BARCA, F., MCCANN, P., & RODRÍGUEZ-POSE, A. (2012). The Case for Regional Development Intervention: Place-Based Versus Place-Neutral Approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 134-152.

- BASU, J. (2020). Multilevel Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission Among Patients With Opioid Use Disorder in Selected US States: Role of Socioeconomic Characteristics of Patients and Their Community, Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology, 7, p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- BELL, C., DEVARAJAN, S., & GERSBACH, H. (2003). The Long-Run Economic Costs of AIDS: Theory and an Application to South Africa (Policy Research Working Papers). The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- BHAGWATI, J. (2004). In Defense of Globalization. Oxford University Press.

- BLOLAND, P. ET AL. (2012). The Role of Public Health Institutions in Global Health System Strengthening Efforts: The US CDC’s Perspective’, PLoS Medicine, 9(4), p. e1001199. [CrossRef]

- BLOOM, D.E., & MALANEY, P.N. (1998). Macroeconomic consequences of the Russian mortality crisis. World Development, 26(11), 2073–2085. [CrossRef]

- BLOOM, D. E., & CANNING, D. (2008). Global demographic change: Dimensions and economic significance. Population and Development Review, 34, 17–51. [CrossRef]

- BLOOM, D.E., & FINLAY, J.E. (2009). Demographic Change and Economic Growth in Asia. Asian Economic Policy Review, 4(1), 45–64. [CrossRef]

- BLOOM, D.E., KUHN, M. AND PRETTNER, K., 2019. Health and economic growth. In Oxford research encyclopedia of economics and finance.

- BOISVERT, I. (2019). Mécanismes d’accès aux services de proximité: état des connaissances. Québec, Québec: Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS), Direction des services sociaux.

- BOURDIEU, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge University Press.

- BOURGUEIL, Y., RAMOND-ROQUIN, A., & SCHWEYER, F.-X. (2021). Qu’appelle-t-on « soins primaires » ? In Les soins primaires en question(s) (pp. 5–13). Rennes: Presses de l’EHESP. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/les-soins-primaires-en-question–9782810908820-p-5.htm.

- BOURQUE, D., & FAVREAU, L. (2005). Le développement des communautés et la santé publique au Québec. Service social, 50(1), 295–308. [CrossRef]

- BRENNER, N. (2009). The Urban Question as a Scale Question: Reflections on Henri Lefebvre, Urban Theory and the Politics of Scale. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(2), 361-378.

- BRENNER, N., & SCHMID, C. (2015). Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban? City, 19(2-3), 151-182.

- CARIOU, C., DUFEU, I., & LECONTE, P. (2020). I. François Perroux – Économie, pouvoir et stratégie. In Les grands auteurs en stratégie (pp. 28–44). Caen: EMS Editions. [CrossRef]

- COOKE, M., & KOTHARI, U. (2001). Participation: The new tyranny? Zed Books.

- CHESHIRE, P., & GORDON, I. R. (1996). Territorial Competition: Some Lessons for Policy. Urban Studies, 33(8), 1287-1313.

- CUDDINGTON, J.T. AND HANCOCK, J.D. (1994) ‘Assessing the impact of AIDS on the growth path of the Malawian economy’, Journal of Development Economics, 43(2), pp. 363–368. [CrossRef]

- DEATON, A., & ZAIDI, S. (2002). Guidelines for Constructing Consumption Aggregates for Welfare Analysis. World Bank Publications.

- DRYZEK, J. S. (2013). The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses. Oxford University Press.

- DURANTON, G., & RODRÍGUEZ-POSE, A. (2004). Rethinking the Costs of Sprawl. Journal of Economic Geography, 4(2), 479-499.

- DUSSAULT, G. AND FRANCESCHINI, M.C., 2006. Not enough there, too many here: Understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Human resources for health, 4, pp.1-16.

- ESCOBAR, A. (2008). Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes. Duke University Press.

- EVANS, D.R. (1994) ‘Enhancing quality of life in the population at large’, Social Indicators Research, 33(1–3), pp. 47–88.

- FARRINGTON J., FARRINGTON C. (2005). Rural accessibility, social inclusion and social justice: Towards conceptualisation. J Transp Geogr. 13(1):1–12. [CrossRef]

- FLEURY, M. J. (2019). Surveillance de l'utilisation des urgences au Québec par les patients ayant des troubles mentaux. INSPQ, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, BiESP, Bureau d'information et d'études en santé des populations.

- FOSTER-FISHMAN, P.G. AND DROEGE, E., 2010. Locating the system in a system of care. Evaluation and program planning, 33(1), pp.11-13.

- FOURCADE, N. AND VON LENNEP, F. (2016) ‘16. L’état de santé des français’, in Traité de santé publique. Cachan: Lavoisier (Traités), pp. 131–139. [CrossRef]

- FOURNIS, Y. (2012). Le développement territorial entre sociologie des territoires et science régionale : La voix du GRIDEQ. Revue d’Économie Régionale & Urbaine, 533-554. [CrossRef]

- GALLUP, J.L., SACHS, J.D. AND MELLINGER, A.D. (1999) ‘Geography and Economic Development’, International Regional Science Review, 22(2), p. 56.

- GALLUP, J. AND SACHS, J. (2001) ‘The economic burden of malaria’, The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 64(1_suppl), pp. 85–96. [CrossRef]

- GALSTER, G., ET AL. (2010). Challenges in Developing Comparable Measures of Urban Neighborhood Poverty: The Case of the Urban Affairs Review. Urban Affairs Review, 45(1), 90-129.

- GARDINER, S. M. (2004). Ethics and Global Climate Change. Ethics, 114(3), 555-600.

- GATRELL, A.C. (2005) ‘Complexity theory and geographies of health: A critical assessment’, Social Science & Medicine, 60(12), pp. 2661–2671. [CrossRef]

- GIRARD, J.-P. (2006). Notre système de santé autrement: L’engagement citoyen par les coopératives. Éditions BLG.

- GIRARDIN, O. ET AL. (2004) ‘Opportunities and limiting factors of intensive vegetable farming in malaria endemic Côte d’Ivoire’, Acta Tropica, 89(2), pp. 109–123. [CrossRef]

- GOSTIN, L.O., MONAHAN, J.T., KALDOR, J., DEBARTOLO, M., FRIEDMAN, E.A., GOTTSCHALK, K., KIM, S.C., ALWAN, A., BINAGWAHO, A., BURCI, G.L. AND CABAL, L., 2019. The legal determinants of health: Harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development. The lancet, 393(10183), pp.1857-1910.

- GROSSMAN, M. (1972) ‘On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health’, Journal of political economy, p. 34.

- HENDERSON, J. 2002. "Building the rural economy with high-growth entrepreneurs," Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, vol. 87(Q III), pages 45-70.

- HARVEY, D. (1989). The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change. Blackwell.

- HARTWIG, J. (2017). Market Share and Price in the US Healthcare Sector: The Case of Preferred Provider Organizations. International Journal of Health Economics and Management, 17(4), 519-541.

- HAUSDORF K, ROGERS C, WHITEMAN D. (2008). Rating access to health care: Are there differences according to geographical region? Aust N Z J Public Health. 32(3): 246–9. [CrossRef]

- HEALEY, P. (1997). Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. UBC Press.

- HEALTH RESOURCES AND SERVICES ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE OF HEALTH EQUITY. 2018. Health Equity Report 2017. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- HÉBERT, R., Québec (Province), and Ministère de la santé et de services sociaux (2013) Rapport du Groupe de travail sur les coopératives de santé. Available online: https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/239193 (accessed on 29 September 2019).

- HÉBERT, G., SULLY, J.-L. AND NGUYEN, M. (2017) ‘L’allocation des ressources pour la santé et les services sociaux au Québec :’, p. 80.

- HICKS, L.L. AND GLENN, J.K. (1991). Rural populations and rural physicians: Estimates of critical mass ratios, by specialty. The Journal of Rural Health, 7, pp.357-371.

- HUDSON, R. (2005). Territory and Development: The Spatiality of Development in the Global Economy. Routledge.

- IGLEHART, J.K., 2018. The challenging quest to improve rural health care. N engl j med, 378(5), pp.473-479.

- INSTITUT NATIONAL DE SANTÉ PUBLIQUE DU QUÉBEC. (2009). Rapport Annuel de Gestion 2008-2009. Québec.

- INSTITUT NATIONAL DE SANTÉ PUBLIQUE DU QUÉBEC. (2019). Rapport Annuel de Gestion 2018-2019. Québec.

- KEELEY, M. (2012). Territorial Equity, Social Justice and Planning: From Rawls to Sustainability. Routledge.

- KICKBUSCH, I. (1997). Health promotion: Concepts and practice. WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- LABONTE, R., FEATHER, J., HILLS, M., & GODUE, C. (1999). Community development in health promotion: A report on the 1998 International Conference on Community Development in Health Promotion, held in Toronto, Canada, April 26-29, 1998. Health Promotion International, 14(3), 261-268.

- LADITKA, J.N., LADITKA, S.B. AND PROBST, J.C. (2009). Health care access in rural areas: Evidence that hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in the United States may increase with the level of rurality. Health & Place, 15(3), pp. 761–770. [CrossRef]

- LEACH, M., ET AL. (2018). Equity and Sustainability in the Anthropocene: A Social–Ecological Systems Perspective on Their Interactions. Sustainability Science, 13(6), 1593-1603.

- LEVESQUE, J. F., ET AL. (2013). Assessing the Performance of Equity in Health Care: A Systematic Review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 66.

- LEWIS, T.P. AND KRUK, M.E., (2019). The Lancet Global Health Commission on High Quality Health Systems: Countries are seizing the quality agenda. Journal of Global Health Science, 1(2).

- LOHR, K.N. AND STEINWACHS, D.M., 2002. Health services research: An evolving definition of the field. Health services research, 37(1), p.15.

- LORENTZEN, A. (2007) ‘The Spatial Dimension of Innovation: Embedding proximity in socio-economic space’, in Conference European network for industrial policy.

- MARMOT, M., & WILKINSON, R. (2006). Social Determinants of Health. Oxford University Press.

- MARTIN, R., & SUNLEY, P. (2006). Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395-437.

- MARTINEZ, J. ET AL. (2004) Does living in rural communities rather than cities really make a difference in people’s health and wellness? Montréal: Institut national de santé publique Québec, Direction planification, recherche et innovation, Unité connaissance-surveillance.

- MCDONALD, S. AND ROBERTS, J. (2006) ‘AIDS and economic growth: A human capital approach’, Journal of Development Economics, 80(1), pp. 228–250. [CrossRef]

- MCGRAIL, M.R. AND HUMPHREYS, J.S. (2009). A new index of access to primary care services in rural areas. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 33(5), pp. 418–423. [CrossRef]

- MCMICHAEL, A. J. (2000). The Urban Environment and Health in a World of Increasing Globalization: Issues for Developing Countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 78(9), 1117-1126.

- MOULAERT, F. AND NUSSBAUMER, J. (2005). Defining the Social Economy and its Governance at the Neighbourhood Level: A Methodological Reflection, Urban Studies, 42(11), pp. 2071–2088. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2018). "Competitive Cities and Climate Change." OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2018/03.

- OPÉRATION VEILLE ET SOUTIEN STRATÉGIQUE ET COLLECTIF DES PARTENAIRES EN DÉVELOPPEMENT DES COMMUNAUTÉS (2022). États généraux en développement des communautés. Octobre 2023.

- OWENS, A., ET AL. (2019). Geographical Context and Health Policy: A Comparative Analysis of Urban Policy Mobility in Amsterdam and Manchester. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(5), 858-876.

- PAMPALON, R., ET AL. (2009). Indices of Social and Material Deprivation for Use in Small-Area Health Research: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges. Social Indicators Research, 94(1), 83-100.

- PATHMAN, D.E., KONRAD, T.R., DANN, R. AND KOCH, G., (2004). Retention of primary care physicians in rural health professional shortage areas. American journal of public health, 94(10), pp.1723-1729.

- PIKE, A., & TOMANEY, J. (2010). Neo-Endogenous Regional Development and Displacement in the European Union. Growth and Change, 41(3), 385-415.

- PIKE, A., ET AL. (2015). Towards a Resilient City Region? Resilience and Recovery in the Glasgow City Region City Region. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 327-343.

- PRESTON, S. H. (1975). The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Population studies, 29(2), 231-248.

- PUTNAM, R.D. (1993). The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life.

- PUTNAM, R.D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster.

- RICKETTS, T.C., (2000). The changing nature of rural health care. Annual review of public health, 21(1), pp.639-657.

- RIGBY, D., & ESSLETZBICHLER, J. (2002). Agglomeration Economies and Productivity Differences in US Counties. Regional Studies, 36(6), 631-645.

- RODRÍGUEZ-POSE, A., & TIJMSTRA, S. (2019). Territorial Equity: Conceptualizations, Indicators, and Implications. Regional Studies, 53(2), 179-190.

- SACHS, J.D. AND WARNER, A.M. (1997) ‘Sources of Slow Growth in African Economies’, Journal of African Economies, 6(3), pp. 335–376. [CrossRef]

- SACHS, J. (2003) Institutions Don’t Rule: Direct Effects of Geography on Per Capita Income. w9490. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, p. w9490. [CrossRef]

- SCOTT, A. J. (1998). Regions and the World Economy: The Coming Shape of Global Production, Competition, and Political Order. Oxford University Press.

- SCOTT, A. J. (2001). Territoriality and Local Politics. Studies in Comparative International Development, 36(1), 27-52.

- SMITH, A., & EASTERLY, W. (2007). Territorial Power in a Fragmented World. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(2-3), 634-644.

- SMITH, A. (2008). Re-scaling the Region and Periphery: The Territorial Dimensions of Welfare-to-Work in the UK. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(1), 212-224.

- SIMONEAU, C. (2023) An Analysis of Primary Care Physician Accessibility and Medical Resource Distribution in Eastern Quebec: Utilizing an Enhanced Two-Step Floating Catchment Area (E2SFCA) Methodology. Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences, 6(10), 342-356.

- STARFIELD, B. (2005). Measurement of Outcome: A Proposed Scheme: Measurement of Outcome. Milbank Quarterly, 83(4), p. 3-11. [CrossRef]

- SULLIVAN, S. E., BARUCH, Y., & SCHEPMYER, H. (2010). The why, what, and how of reviewer education: A human capital approach. Journal of Management Education, 34(3), 393-429.

- THOMPSON KLEIN, J. (2011) ‘Une taxinomie de l’interdisciplinarité’, Nouvelles perspectives en sciences sociales, 7(1), p. 15. [CrossRef]

- WANG, F. (2012) ‘Measurement, Optimization, and Impact of Health Care Accessibility: A Methodological Review’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(5), pp. 1104–1112. [CrossRef]

- WANG, X. ET AL. (2018). Spatial accessibility of primary health care in China: A case study in Sichuan Province, Social Science & Medicine, 209, pp. 14–24. [CrossRef]

- WEISBROD, B. A., & HELMINIAK, T. W. (1977). Parasitic diseases and agricultural labor productivity. Economic development and cultural change, 25(3), 505-522.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO). (2018). Primary Health Care on the Road to Universal Health Coverage: 2019 Global Monitoring Report. WHO.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO). (2020). Retention of the health workforce in rural and remote areas: A systematic review. Human Resources for Health Observer Series No. 25. WHO.

- ZIMMERMAN, M. A. (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581-599.

- ZUINDEAU, B. (2005). Équité territoriale: Quelles lectures par les théories du développement durable ?. Reflets et perspectives de la vie économique, XLIV, 5-18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).