1. Introduction

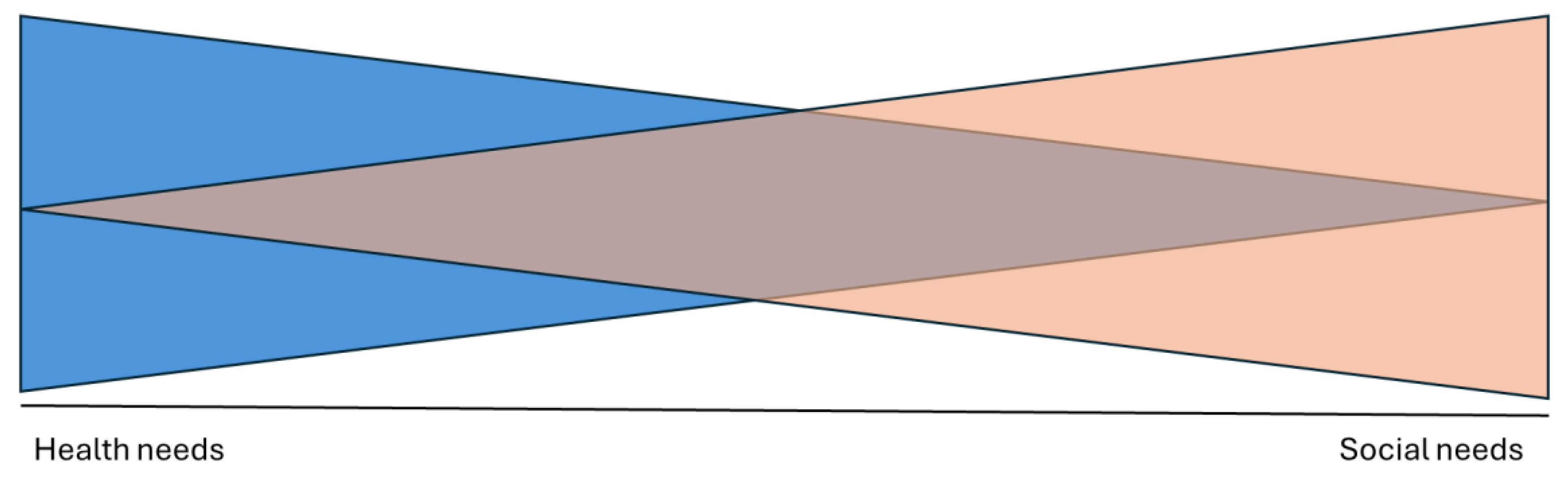

Human health and social needs exist along a dynamic continuum. This continuum (

Figure 1), illustrates that increases in health incidences may be related to unmet social needs; while those with social privileges and adequate support may experience less frequent or severe health incidences.[

1,

2,

3] Recognizing that health status is inextricably impacted by social determinants of health, community paramedicine has both an opportunity and a responsibility to address social needs in effort to reduce healthcare inequities.[

4,

5]

Community paramedicine is a healthcare approach where paramedics expand their traditional emergency response roles to provide a broader spectrum of services within the community, such as providing and supporting care to community members with chronic diseases, structural barriers to accessing care, and socio-economic issues.[

6] Instead of solely focusing on acute emergency care and transportation to hospitals, community paramedics utilise their medical expertise to deliver primary care, preventive services, and health education and promotion directly to individuals in their homes or community settings. Community paramedicine programs have existed since the early 2000s and have historically focused on resource optimization.[

7,

8] While this remains a predominant driver, innovation in recent years demonstrates that when community paramedicine is integrated into healthcare, it is well-positioned to meet the needs of structurally marginalized communities by focusing services for those facing barriers accessing equitable care.[

9,

10,

11,

12]

A recent scoping review by Lunn et al. explored how community paramedicine supports social needs along a health and social continuum.[

13] The review described the evolving ways community paramedicine models are addressing health and social needs within communities around the world. A key recommendation from the review was the need to meaningfully engage communities when developing programs to understand, co-design and implement a model that addresses the specific needs of each community; however, there was a lack of evidence to guide this approach. The results highlighted the opportunity to determine best practices for conducting community needs assessments that include equitable partner engagement and harnessing community expertise.

Communities are experts in their health and social experiences and are therefore key partners in co-designing service delivery. Where community paramedicine programs continue to develop programming without meaningful community engagement, they risk exacerbating health services inequities. Where health systems remain the sole architects and without understanding and addressing the needs of communities, there will be gaps in delivery and challenges in conducting meaningful evaluation. Conversely, co-designing community-led and integrated healthcare programming will enhance feasibility and sustainability, and ideally, promote equitable experiences and meaningful outcomes.

Applying a systems thinking lens, we identified community paramedicine more broadly as it is positioned within integrated healthcare systems, and how healthcare itself is positioned within greater society.[

14] Recognizing that system complexities impact health status, paramedicine has a social responsibility to meaningfully engage in community needs assessments to co-design service delivery and generate upstream health and social solutions for individuals and communities.[

5,

9,

14,

15] However, there remains a lack of guidance related to conducting needs assessments in community paramedicine, leading to inconsistencies in design, development, implementation, and evaluation of outcomes.[

13] Due to the lack of appropriate needs assessment tools in paramedicine and the potential to learn from strategies implemented in other professions, this study aimed to identify elements of community needs assessments and use those elements to inform the development of a bespoke tool for those developing community paramedicine programs. We conducted a multi-methods study comprised of a document analysis and feedback from system partners to achieve the following aims in the context of Canadian paramedicine:

Identify and explore existing community needs assessment tools informing community paramedicine and health-social services program development.

Identify gaps in community needs assessment strategies to enhance community-led, and co-designed service delivery.

Produce draft materials to be presented at a meeting of community paramedicine system partners and gather their feedback to inform a final version.

2. Methods

Study Design

This manuscript describes a multi-phase project which aimed to produce the Community Paramedicine Needs Assessment Tool (CPNAT). While systems are vast, and include geopolitical implications on health status, we set boundaries for this study to support feasibility. Therefore, this study focused on community paramedicine within Canada. However, the output from this study may have applicability in other contexts outside of Canada with careful considerations related to transferability.

Positionality

TM is an able-bodied, Canadian, white woman. She is a degree-educated paramedic, researcher, and a subject matter and research expert on community paramedicine in Canada.

BS is an able-bodied, Australian, white man, who is a doctoral-educated paramedic, researcher and educator with multi-methods methodological expertise and research expertise in community paramedicine.

CC is an able-bodied, Canadian, white woman. She is a doctoral candidate, paramedic, researcher, and subject matter expert on paramedicine in Canada.

AH is an able-bodied, Canadian, East-Indian man, who is a doctoral-educated researcher with methodological expertise in health professions education.

LC is an able-bodied, British, white woman, who is a doctoral-educated health researcher with methodological expertise and research expertise on community paramedicine in Canada, community health, and social determinants of health.

AB is an able-bodied, Irish Canadian, white man, who is a doctoral-educated paramedic, researcher and educator with methodological expertise including document analysis, and research expertise in community paramedicine.

We acknowledge that our positionality as a team and as individuals means we approached this study from a specific lens. As such, it was important to engage with partners throughout the development of this tool to gain broader perspectives, diverse opinions, and rich feedback.

Document Analysis

The review by Lunn et al. demonstrated a lack of peer reviewed studies which aligns with the findings of community paramedicine programs internationally, and we therefore sought to also include grey literature.[

7,

13] A document analysis was considered the most appropriate choice aligned with the timelines, resources, and feasibility of this initial phase of project work to identify best practices. Document analysis is a qualitative research approach where texts are systematically explored and interpreted by the researcher to evoke meaning, understanding and generate knowledge relative to specific research question(s).[

16,

17] While document analysis is often used in triangulation to complement other methodologies, it can be used as a stand-alone method.[

17] We registered the project on the Open Science Framework (OSF) to enhance transparency and trustworthiness of study design and implementation -

https://osf.io/2d9j6/. We report our findings using the Checklist for the Use and Reporting of Document Analysis (CARDA).[

18]

Using O’Leary’s eight-step planning approach for document analysis [

19], we identified the following documents for inclusion:

Community needs assessment in published and grey literature in community paramedicine and other health and social care professions in Canada with a targeted literature review.

Community needs assessment tools used to guide program design and development by community paramedicine service providers in Canada.

The results of these approaches were included and examined in the document analysis. We processed the texts using the eight-step approach outlined by O’Leary.[

19]

We asked questions about the texts and referred to this as the interview. The interview phase was conducted by TM. Questions were informed by the findings of Lunn et al. scoping review.[

13] (see Online Resource I).

Document corpus

Documents were included as described above. Documents were also included if they were used to guide community paramedicine program design and development in Canada. Documents were excluded if they did not describe a community needs assessment, described an individual patient-level needs assessment, were duplicate, were not produced in English, or were unable to be collected for review.

Document collection and management

We conducted a focused search of the literature to identify community needs assessment tools in health and social care professions in both published and grey literature. The search strategy involved searches with no date limitations in MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Google Scholar using combinations of the following phrases and keywords informed by the objectives of the study: needs assessment, community needs assessment, social needs assessment, conducting needs assessment, and community-level needs assessment. The grey literature search was guided by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) grey matters checklist.[

20] We conducted backward citation chasing of literature search results.[

21] We sought needs assessment tools and other program design documents via direct request to members of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) Group Technical Committee on Community Paramedicine Program Development via the CSA Communities website. Documents were stored on a password-protected computer in a private folder. Documents were identified and collected by the team between January and March 2024.

Document quality

We found the documents to be of reasonable quality. Documents collected from database searches were comprehensive in addition to those sourced from searching grey literature. While some online tools comprised extensive chapters, other documents lacked structure. Documents were fully complete and free of obvious production gaps or redactions. We found that all documents provided content that directly addressed the research questions.

Data analysis

We performed abductive coding to identify key elements of community needs assessments. The data were analysed for the prevalence of key elements, deductively coded against Lunn et al.’s scoping review findings, and inductively coded against the document data itself. Extraction and coding were performed by TM and a 20% sample was reviewed by AB.

Needs assessment domains

We grouped elements according to the social determinants of health outlined in the scoping review and further refined these categories by grouping and collapsing common items to align with the World Health Organization (WHO) social determinants of health equity domains.[

22] (see

Table 1 and

Figure 2). The items were organized into their respective key concept areas by TM and reviewed by AB. We identified gaps by considering what was not present in the data (informed by a systems thinking approach used and published as part of a larger pan-Canadian paramedicine project [

14]) and identified elements in the scoping review by Lunn et al.[

13] that did not appear in the data for this study. Interpretation of the data was completed in a summative process, while seeking to remain objective to the content and its relevance to the research questions.

The draft CPNAT was created by combining the findings of our existing scoping review and the extracted data from the document analysis - see

Table 2 to review all key elements incorporated into the first draft of the CPNAT.

3. Feedback from system partners

Procedure

We presented the first draft of the CPNAT to system partners in community paramedicine at the 20th International Roundtable on Community Paramedicine meeting which took place on June 7th and 8th 2024 in Quebec City, Canada. The draft was distributed by email to conference attendees a week in advance of the feedback session. An explanatory statement on the nature of the session along with a copy of the ethics approval letter was also attached to this email. Participants were informed of the voluntary nature of their participation and their right to withdraw or not participate at any stage of the process. On the day, members of the project team facilitated a 60-minute feedback session with participants. During this 60-minute period, participants worked in small groups to review and provide feedback on the draft CPNAT using an online Google form that was saved to a secure Monash Google Drive account.

Data analysis

All data were collated and organised for review by the project team after the event. Responses from participants were reviewed individually and categorised via a high-level deductive content analysis [

23] informed by the six CPNAT related questions posed to the participants (i.e., structure of tool, concept clarity, missing elements, additional guidance, utility in context, and additional feedback – see Online Resource 2). Where possible, responses were matched directly to existing codes developed in the document analysis to focus possible edits.

Trustworthiness

To promote trustworthiness [

24] of our study findings, we explored the documents’ agendas and biases, such as who produced them and the audience the documents were intended for, based on criteria such as relevance and reliability as described by O’Leary.[

19] We conducted our research using a systematic approach for planning and conducting document analyses described by O’Leary, and reported our findings using the CARDA checklist, all underpinned by a reflexive approach.[

25] Data were organized and stored in password-protected archives. We spent time engaging with and revisiting the data over multiple months to support credibility. Dependability was maintained through abductive coding, including a rationale for code creation in alignment with pre-existing frameworks. Reproduction and confirmability were ensured by publicly registering our project on OSF and supporting alignment through a clear audit trail of detailed notes related to data sources, comments, and changes from the first draft of the CPNAT through to the final published version.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Monash University (project ID #42775).

4. Results and Findings

Document analysis

Of the included documents, 25 were published in the United States of America, nine in Canada, and one each in Italy, Israel, Jamaica, and South Korea (based on a project in Vietnam). Documents were published from 2001 to 2023. They comprised a mix of reports, guidelines, reviews, and tools and all were available in digital format. See Online Resource 3 for detailed extraction data and document characteristics.

Six of the nine documents published in Canada (67%) explored community needs assessment in the context of Indigenous reconciliation and health justice.[

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] These key elements identified in the provision of reconciliation informed a designated section guiding considerations for equity and Indigenous health justice within the draft CPNAT. While intersectionality was identified in the scoping review as an important area to explore within paramedicine, with implications that impact health status, outcome, and healthcare experiences – considerations of intersectionality in needs assessment approaches remained a gap throughout this review with only seven documents (18%) outlining considerations of intersectionality in needs assessment approaches.[

27,

28,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]

System partner feedback

A total of 33 group responses were received from 112 participants at the feedback session. Twenty-eight groups provided detailed feedback on the structure and content of the tool. For example, participants spoke of the ability of the tool to provide an overview of the health and social care system, stating ““it is very comprehensive. It covers all key areas that allow you to understand all aspects in health and non-health partnerships, service delivery, and system gaps.” In relation to its ability to provide the information that they as developers of CP programs would need, participants were resounding in their support for the tool, stating it “appears to provide a robust assessment of community overview and needs from various lenses and perspectives.”

However, using the tool would present challenges to some. For example, some highlighted the need for “an option to skip sections that aren’t needed”, while others stated that the tool’s “length makes building a case in your head dynamically hard to retain”. In its attempts to be comprehensive some felt that the tool “is trying to determine too many things. It seems like it didn’t match a need assessment with program delivery.” Despite its comprehensiveness, some participants highlighted areas where the tool may struggle to adequately or accurately capture diverse community needs, such as transient populations, increasing vaccine hesitancy, and poor health literacy among others.

A total of 21 group responses suggested the need for additional guidance and resources to use the tool, such as a user toolkit. Several groups suggested the need for a completed example community needs assessment, or at a minimum, examples of the types of answers that the tool might generate. Several participants raised questions related to scalability, for example “How do we apply the tool to specific communities? Specific buildings that we serve?”. Finally, participants provided feedback that guidance on what to do with the completed tool and the answers within was required - e.g., how does the information lead to supporting a gap analysis, what is the process for scoring of answers, and how should they use this information to guide program development.

Finally, there were several suggestions to develop a branching logic software-based version of the tool to encourage uptake and increase applicability in the future. These would help to categorize the importance of certain answers to specific communities or populations via a “smart form that skips repetitive or irrelevant sections and brings you to the next most important piece.” The potential to integrate existing data sources (publicly available and privately held) and machine learning into a future digital tool was also mentioned by some groups.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to identify and explore community needs assessment tools informing community paramedicine and health-social service program development. Through a document analysis and the input of system partners, we drafted and finalised a needs assessment tool for use by community paramedicine programs. Informed by our analysis, we discerned the need to plan and co-design needs assessments with communities, the need to intentionally assess for inequities, and opportunities for future directions.

Community paramedicine programs are not off-the-shelf solutions to addressing unmet health and social needs.[

37] Upstream solutions should be tailored to align with community needs. Recent reviews of community paramedicine program development indicated a lack of structured tools to facilitate such assessments, and an ongoing need for such tools to prevent blind spots when developing programs.[

13] If we continue to remain unaware of community needs – from the community’s perspective – while we innovate and expand community paramedicine programs, we may not be optimally designing such programs to meet community needs. At best, this risks inappropriate and inefficient resource use, and at worst, we may be directly exacerbating health inequities. Therefore, it is imperative that communities are lead partners in the co-design of needs-based services from the outset of community paramedicine program development. However, meaningful community engagement takes time, can face significant barriers, and requires collaboration.[

38,

39,

40]

Planning allows for involvement of key partners from the beginning of the process, cultivating trusting relationships and community support that is essential for empowering community agency and leadership.[

41] Community involvement can enhance outcomes by generating community-based participatory research evidence.[

42,

43] Through planning, key partners in allied health and social services can be identified to contribute and share in the effort. These relationships will be valuable for collaborating to generate strategies for services to address community needs and reduce inequities. The comprehensive outcomes of this document analysis also highlight the need to prioritize detailed planning when conducting a community needs assessment. Developing a plan for assessing community needs will support service leaders in understanding how to best serve their communities in logical, efficient, and prioritized ways.[

42,

44] This requires clearly identifying the purpose of the needs assessment. Rigorous application of the CPNAT to yield trustworthy outcomes will require significant support in the form of meaningful engagement strategies, and appropriate funding.[

45] Robust assessment will take time – it will need to be thorough, iterative, flexible, and responsive to community partner capacity and priorities. Paramedic service leaders should be flexible with timelines to support community agendas.

Another challenge for those who use the CPNAT is how to prioritise identified needs. Outcomes of the CPNAT are non-prescriptive and when performed rigorously, applying the tool will yield valuable findings to inform strategies that better align services with community needs. It is imperative to identify community priorities to establish trust and respect, especially when these misalign with health-system priorities. We also offer that there is opportunity here for service leaders to identify strategies that support collaboration, and integrate care with other health- and social-care professions - not all community needs are best met by community paramedicine programs.[

13] Identifying allied health, social, community partners, and populations with needs and their caregivers in the planning stage and mitigating barriers to participation, will enable community-led and co-designed outcomes and priorities.[

43] Applying a strengths-based approach to identify and support existing community initiatives that focus on outcomes of health justice for structurally marginalized groups will help to ensure that any identified priorities are meaningfully addressed by community paramedicine programs in collaboration with other health and social care services.[

46,

47]

We must however acknowledge that the evolution of community paramedicine has been largely driven by health system utilization measures, policies that do not engage with communities, and health system structures that vary greatly and are deeply embedded.[

8] Recognizing that healthcare in Canada is ultimately inherited and structured by colonialism, health-system driven initiatives risk overlooking inequities in healthcare experiences and health outcomes.[

48,

49] Therefore, it is imperative that the CPNAT becomes a core tenet in the development of programs moving forward, with the intentionality of considering intersectionality when assessing for inequities to reduce barriers and promote health justice for structurally marginalised populations.[

13,

50,

51] For example, there is an identified need within Canada for ongoing commitments of reconciliation that support Indigenous communities’ self-determination and that they be restored with agency and autonomy. One way to enact this commitment is by engaging Indigenous communities in co-design, or better yet to co-create community paramedicine programs serving their communities.[

52] To not do so means that health and social program development remains largely health-system driven and designed, risking further embedding settler colonialism and structures that promote inequity.

Limitations

The document analysis was limited to those documents that can be collected. While we aimed to be comprehensive in identification and collection methods, there may be additional documents that exist but aren’t available in a public domain. We limited the review to English language documents. We acknowledge that the inclusion of English-only documents risks excluding potentially useful information from authors or jurisdictions where English is not the primary language. We acknowledge that we did not use community-based participatory approaches when developing the CPNAT due mainly to project constraints (e.g., academic timelines, funding period). We did however engage with system partners and offer the CPNAT as a foundation on which future work can build and enhance the tool by using equity-serving and participatory research approaches that involve communities. As such, we published the CPNAT under a Creative Commons licence to facilitate future enhancements and iterations by the community.

Future directions

Despite direct outreach to community paramedicine services in Canada to explore current tools used in program design and development, less than 25% of documents were collected from this source. This may be reflective of the reality that service leaders in Canada are limited by operational demands, budget cycles, policy momentum or disruption, and are often required to develop programming strategy in the absence of standards or guidance.[

8] This does not discredit initiatives created in this order, rather it recognizes the need to apply evidence-informed guidance to ensure quality of initiatives once available. Community paramedicine continues to be well-positioned within healthcare to be responsive to the dynamic evolution of community needs. Community paramedicine leaders are now supported with this tool to inform community needs- and values-based care models. The CPNAT provides a structured tool to guide needs assessment and will enhance health equity by supporting alignment of community needs and services, with standard use for service design and delivery.

The iterative next steps of this multi-phase project include opportunities to improve application and accessibility of the tool through formatting, translation, testing, evaluation, and ongoing improvement. Equity-focused implementation strategies and community-based participatory research methods should be applied going forward in the continued development of the CPNAT, including data stewardship.[

43,

47,

53] This equity-focused lens should continue when synthesizing tool outcomes into service initiatives. Ideally the decision-making processes applied to optimize the CPNAT and produce equity-generating initiatives will be participatory and inclusive.[

43,

54] An opportunity exists for researchers and service leaders to explore transferability and adaptability of the CPNAT for use in alternate jurisdictions, beyond Canada.

6. Conclusions

This study involved a document analysis that identified and synthesized community health and social needs assessment tools and frameworks. Feedback from system partners on these synthesized findings informed the CPNAT. The development of this tool was prioritized in response to an identified need for a structured guide to approach community needs assessment to inform community paramedicine program design and delivery. The CPNAT will improve health equity by guiding community paramedicine programs to better align their services with the health and social care needs of communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: TM, CC, AB; Methodology: TM, AB. Formal analysis: TM, BS, CC, AH, LC, AB. Data Curation: TM, AB. Writing - Original Draft: TM, AB. Writing - Review & Editing: TM, BS, CC, AH, LC, AB. Visualization: AB. Project administration: AB. Funding acquisition: TM, CC, AB.

Funding

This work was supported by Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC). HEC is an independent, not-for-profit charity funded primarily by Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of Health Canada. The CPNAT publication is provided “as is” and is for informational/educational purposes only.

Data Availability

Data related to this project are available on request from the authors and archived on the OSF project page at

https://osf.io/2d9j6/.

Acknowledgments

This collaborative project was conducted on colonised Indigenous lands now referred to as Canada. These lands are home to the many diverse First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples whose ancestors have stewarded this land since time immemorial. We wish to thank Sarah Olver, Jennifer Crook, and Neil Drimer from Healthcare Excellence Canada for their support and commitment to the project. We also wish to acknowledge Gary Wingrove, JD Heffern, Michael Nolan, and the participants at the International Roundtable on Community Paramedicine (IRCP). Thank you to Chelsea Lanos for her support of the partner convening. Finally, thank you to the CSA Group Technical Committee on Community Paramedicine, IRCP, the Paramedic Chiefs of Canada, the Paramedic Association of Canada, and the McNally Project for Paramedicine Research for their support and endorsement of this project.

Conflicts of Interest

Tyne Markides, Brendan Shannon, Aman Hussain, and Liz Caperon have no previous or existing relationship with HEC to declare. Alan Batt and Cheryl Cameron are faculty and have existing relationships with HEC across several projects.

References

- Essington, T., Bowles, R., & Donelon, B. (2018). The Canadian Paramedicine Education Guidance Document. Ottawa: Paramedic Association of Canada.

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation : health equity through action on the social determinants of health : final report of the commission on soci al determinants of health. Combler le fossé en une génération : instaurer l’équité en santé en ag issant sur les déterminants sociaux de la santé : rapport final de la Commission des Déterminants sociaux de la Santé, 247.

- Porroche-Escudero, A. (2024). Health systems and quality of healthcare: bringing back missing discussions about gender and sexuality. Health Systems, 13(1), 24–30. [CrossRef]

- Allana, A., & Pinto, A. (2021). Paramedics Have Untapped Potential to Address Social Determinants of H ealth in Canada. Healthcare Policy | Politiques de Santé, 16(3), 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W., Allana, A., Beaune, L., Weiss, D., & Blanchard, I. (2022). Principles to Guide the Future of Paramedicine in Canada. Prehospital Emergency Care, 26(5), 728–738. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, B., Baldry, S., O’Meara, P., Foster, N., Martin, A., Cook, M., … Miles, A. (2023). The definition of a community paramedic: An international consensus. Paramedicine, 20(1), 4–22. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, B., Batt, A. M., Eaton, G., Bowles, K.-A., & Williams, B. (2021). Community Paramedicine Scoping Exercise. Melbourne, Australia: Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3LX7GiT.

- Shannon, B., Eaton, G., Lanos, C., Leyenaar, M., Nolan, M., Bowles, K., … Batt, A. (2022). The development of community paramedicine; a restricted review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), 3547–3561. [CrossRef]

- Batt, A., Hultink, A., Lanos, C., Tierney, B., Grenier, M., & Heffern, J. (2021). Advances in Community Paramedicine in Response to COVID-19. Ottawa: CSA Group. Retrieved from https://www.csagroup.org/article/research/advances-in-community-paramedicine-in-response-to-covid-19/.

- Leyenaar, M. S., McLeod, B., Jones, A., Brousseau, A.-A., Mercier, E., Strum, R. P., … Costa, A. P. (2021). Paramedics assessing patients with complex comorbidities in community settings: results from the CARPE study. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 23(6), 828–836. [CrossRef]

- Taplin, J., Dalgarno, D., Smith, M., Eggenberger, T., & Ghosh, S. M. (2023). Community paramedic outreach support for people experiencing homelessness. Journal of Paramedic Practice, 15(2), 51–57. [CrossRef]

- Ashton, C., & Leyenaar, M. S. (2019). Health Service Needs in the North: A Case Study on CSA Standard for Community Paramedicine. Toronto: CSA Group. Retrieved from https://www.csagroup.org/article/research/health-service-needs-in-the-north/.

- Lunn, T. M., Bolster, J. L., & Batt, A. M. (2024). Community Paramedicine Supporting Community Needs: A Scoping Review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 2024(1), 4079061. [CrossRef]

- Batt, A. M., Lysko, M., Bolster, J. L., Poirier, P., Cassista, D., Austin, M., … Tavares, W. (2024). Identifying Features of a System of Practice to Inform a Contemporary Competency Framework for Paramedics in Canada. Healthcare, 12(9), 946. [CrossRef]

- Drennan, I. R., Blanchard, I. E., & Buick, J. E. (2021). Opportunity for change: is it time to redefine the role of paramedics in healthcare? Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 23(2), 139–140. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A. (2021, December 29). Key Methods Used in Qualitative Document Analysis. SSRN Scholarly Paper, Rochester, NY. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Cleland, J., MacLeod, A., & Ellaway, R. H. (2023). CARDA: Guiding document analyses in health professions education resea rch. Medical Education, 57(5), 406–417. [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, Z. (2017). The Essential Guide to Doing Your Research Project (3rd ed.). London: SAGE Publications.

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. (2019). Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Retrieved from https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters.

- Haddaway, N. R., Grainger, M. J., & Gray, C. T. (2021, February 16). citationchaser: An R package and Shiny app for forward and backward citations chasing in academic searching. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Operational framework for monitoring social determinants of health equity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240088320.

- Pandey, J. (2019). Deductive Approach to Content Analysis. In M. Gupta, M. Shaheen, & K. P. Reddy (Eds.), Qualitative Techniques for Workplace Data Analysis (pp. 145–169). Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E., & Magilvy, J. K. (2011). Qualitative Rigor or Research Validity in Qualitative Research. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 16(2), 151–155. [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773384. [CrossRef]

- Mannix, T. R., Austin, S. D., Baayd, J. L., & Simonsen, S. E. (2018). A Community Needs Assessment of Urban Utah American Indians and Alaska Natives. Journal of Community Health, 43(6), 1217–1227. [CrossRef]

- Cain, C. L., Orionzi, D., O’Brien, M., & Trahan, L. (2017). The Power of Community Voices for Enhancing Community Health Needs Assessments. Health Promotion Practice, 18(3), 437–443. [CrossRef]

- Taplin, J. G., Bill, L., Blanchard, I. E., Barnabe, C. M., Holroyd, B. R., Healy, B., & McLane, P. (2023). Exploring paramedic care for First Nations in Alberta: a qualitative study. Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal, 11(6), E1135–E1147. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Long Term Care. (2020). Community Paramedicine for Long-Term Care: Framework for Planning, Implementation and Evaluation. Toronto: Ministry of Long Term Care.

- BCEHS. (2019). Community Paramedicine - Community Selection. Vancouver, British Columbia: BCEHS.

- Bigras, P. (2020). WAHA Paramedic Service’s Indigenous Community Paramedic Program: Assessment of Health and Social Needs. Moosonee.

- County of Renfrew Paramedic Services. (2020). Community Needs Assessment. Organizational guideline. Pembroke, ON: County of Renfrew.

- Rayan-Gharra, N., Ofir-Gutler, M., & Spitzer, S. (2022). Shaping health: conducting a community health needs assessment in culturally diverse peripheral population groups. International Journal for Equity in Health, 21(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Suiter, S. V. (2017). Community health needs assessment and action planning in seven Dominican bateyes. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Berkley-Patton, J., Thompson, C. B., Lister, S., Hudson, G., Hudson, W., & Hudson, E. (2020). Engaging Church Leaders in a Health Needs Assessment Process to Design a Multilevel Health Promotion Intervention in Low-resource Rural Jamaican Faith Communities. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital. (2024). Community Health Needs Assessment. Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital. Retrieved from https://nvrh.org/community-health-needs-assessment/.

- CSA Group. (2017). CAN/CSA Z1630:17 Community paramedicine: Framework for program development. Toronto: CSA Group.

- Mittal, P., & Bansal, R. (2024). Issues and Challenges in Community Engagement. In P. Mittal & R. Bansal (Eds.), Community Engagement for Sustainable Practices in Higher Education: From Awareness to Action (pp. 211–224). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Turin, T. C., Chowdhury, N., Haque, S., Rumana, N., Rahman, N., & Lasker, M. A. A. (2021). Meaningful and deep community engagement efforts for pragmatic research and beyond: engaging with an immigrant/racialised community on equitable access to care. BMJ Global Health, 6(8). [CrossRef]

- Sved, M., Latham, B., Bateman, L., & Buckingham, L. (2023). Hearing what matters: a case study of meaningful community engagement as a model to inform wellbeing initiatives. Public Health Research & Practice, 33(2) e3322316. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. K. (2003). Putting the Community Back in Community Health Assessment: A Process and Outcome Approach with a Review of Some Major Issues for Public Health Professionals. Journal of Health & Social Policy, 16(3), 19–33. [CrossRef]

- The University of Kansas. (n.d.). Chapter 3. Assessing Community Needs and Resources | Section 1. Develo ping a Plan for Assessing Local Needs and Resources | Checklist | Comm unity Tool Box. Retrieved October 27, 2024. from https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community -needs-and-resources/develop-a-plan/checklist.

- Akintobi, T. H., Lockamy, E., Goodin, L., Hernandez, N. D., Slocumb, T., Blumenthal, D., … Hoffman, L. (2018). Processes and Outcomes of a Community-Based Participatory Research-Driven Health Needs Assessment: A Tool for Moving Health Disparity Reporting to Evidence-Based Action. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 12(1), 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Feldhaus, H. S., & Deppen III, P. (2018). Chapter 30: Community Needs Assessments. In Handbook of Community Movements and Local Organizations in the 21st Ce ntury (pp. 497–510). Cham: Springer International Publishing. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-77416-9.

- Hernandez, S. G., Genkova, A., Castañeda, Y., Alexander, S., & Hebert-Beirne, J. (2017). Oral Histories as Critical Qualitative Inquiry in Community Health Ass essment. Health Education & Behavior, 44(5), 705–715. [CrossRef]

- Cockrell, K. R., Reed, B., & Wilson, L. (2019). Rural paramedics’ capacity for utilising a salutogenic approach to hea lthcare delivery: a literature review. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 16. [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P., Abdul Aziz, Y., Lambert, M., Bartholomew, K., Rankin, N., Fusheini, A., … Crengle, S. (2023). A scoping review of equity-focused implementation theories, models and frameworks in healthcare and their application in addressing ethnicit y-related health inequities. Implementation Science, 18(1), 51. [CrossRef]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Retrieved from http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisition_lists/2015/w15-24-F-E.html/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf.

- Turpel-Lanfond (Aki-Kwe), M. E. (2020). In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-Specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care. Retrieved from https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2021/02/In-Plain-Sight-Data-Report_Dec2020.pdf1_.pdf.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C., Whelan, J., Brimblecombe, J., & Allender, S. (2022). Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health: a perspective on definition and distinctions. Public Health Research & Practice, 32(2). Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/node/318244.

- First Nation Information Governance Centre. (n.d.). OCAP Principles. Retrieved June 11, 2023, from. Retrieved from https://fnigc.ca/.

- Vanstone, M., Canfield, C., Evans, C., Leslie, M., Levasseur, M. A., MacNeil, M., … Abelson, J. (2023). Towards conceptualizing patients as partners in health systems: a systematic review and descriptive synthesis. Health Research Policy and Systems, 21(1), 12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).