1. Introduction

Existing research demonstrates that the distribution of research efforts focusing on specific genes, proteins, and molecular mechanisms is biased by social factors that are not always related to the importance of corresponding molecules for living organisms. For example, analysis of temporal patterns of publications on specific genes suggests that some genes received exceptional attention due to societal needs [cure for an important disease] [

1]. Only a fraction of protein kinases, ion channels, G protein-coupled receptors, and nuclear receptors received significant research attention, not explained by their more important roles in cells [

2,

3,

4].

Surprisingly the list of proteins [

3] and genes [

5] which attracted most of the research attention did not change over the period of 20 years. A high level of research attention to a selected list of molecules may be partly explained by trends in the scientific community resulting from dynamics of social networks [

1]. These trends are successfully modeled based on vast publication data demonstrating that researchers predominantly publish on genes that are already popular in research literature [

6,

7]. At least partly these trends may originate from the social phenomena known as “famous for being famous” in popular culture. Additional social bias results from a catch-22 situation when research hypotheses are being developed using molecular pathways and functional biological categories based on well-annotated molecules. The resulting hypotheses focus further research efforts on the same set of molecules and pathways [

8]. A recent analysis of gene features in association with the number of published studies showed that features that hinder our ability to study specific genes using traditional methodologies are associated with a smaller number of papers [

5].

Taken together these studies suggest that medico-biological research is prone to bias due to a broad range of factors, which all together concentrate the attention of researchers on a small number of well-known molecules/mechanisms leaving others underexplored. In accordance with this view, central to mechanistic toxicology is a narrow range of molecular pathways that are assumed to be involved in a significant part of toxicities. It is unclear however if there are other molecular mechanisms overlooked by previous research which also play a significant role in toxicity events. A recent attempt to identify in an unbiased manner molecular mechanisms most sensitive to a broad range of chemical exposures demonstrated that indeed a range of molecular mechanisms poorly covered by toxicological research may be as sensitive to toxins as those that received significant attention [

9,

10].

Toxicology started to use molecular biology tools in the late 1970s [

11], however, the rapid transformation into a molecular discipline was triggered by the publication of

Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: a Vision and a Strategy in 2007 by the US National Research Council [

12]. One important component of this transformation consists in the understanding of molecular mechanisms that causally link exposures with adverse outcomes - toxicity pathways or adverse outcome pathways (AOP) [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Characterization of AOP is critically important for the transition to pathway-based toxicity testing [

17]. Thus, a systematic effort is needed to identify and characterize AOP and ensure that no important mechanisms linking exposures and toxicities have been overlooked.

In this report, we attempt to use minimally biased approaches to identify underexplored genes and molecular mechanisms sensitive to chemical exposures to inform toxicological community on the important directions of the future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sensitivity of Genes to Chemical Exposures

Previous research developed an approach to identify genes sensitive to chemical exposures in an unbiased way [

9,

18]. In short, transcriptomic data were extracted from toxicological experiments in which gene expression changes in responses to chemical exposures were analyzed using high-throughput methods. Transcriptomic information from 2,169 individual in-vivo and in-vitro studies using human, rat, or mouse cells or tissue covering experiments with 1,239 chemical compounds was extracted from the Comparative Toxicogenomic Database (CTD) [

19]. Genes that are not present in the genomes of all three species were excluded from further analysis. The number of published chemical-gene interactions (CGI) was calculated for 17,338 genes to represent their sensitivity to chemical exposures. It is important to note that ranked sensitivities of genes to chemical exposures do not depend on the composition of chemicals used for the identification of CGI numbers [

9]. The full list of genes with their corresponding CGI numbers is available through Mendeley Data [

20]. The threshold between genes highly sensitive to chemical exposures and genes with low sensitivity was determined using a method for the identification of cutoff points in descriptive high-throughput omics studies [

21]. This approach identifies an inflection point in a ranked distribution of variables if this distribution follows a biphasic pattern. In the current study, the method identified a cutoff between the big number of genes with low CGI numbers (< 73) and the smaller group of genes with high CGI numbers (≥ 73).

2.2. Number of Publications Per Gene

The level of research attention for every human gene was evaluated by the number of PubMed publications that mentioned the gene in the title and/or abstract. This analysis was done by T. Stoeger’s group using PubTator [

22]. As a result of this research, the authors created a database and a tool

Find My Understudied Genes (FMUG) (

https://fmug.amaral.northwestern.edu/) which contains the number of publications per every human gene. This information for 19,243 genes was downloaded for our analysis. We used the same method for cutoff point identification as described in the previous paragraph [

21] to determine the threshold between underexplored (< 200 publications/gene) and well-explored (≥ 200 publications/gene) genes.

2.1. Underexplored Pathways Sensitive to Chemical Exposures

To analyze biological categories enriched by underexplored genes sensitive to chemical exposures the list of all genes sensitive to chemical exposures (CGI number ≥ 73] with their respective publication numbers was used for gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) [

23,

24]. GSEA was developed to characterize the cumulative shift of genes in a particular pathway towards an increase or decrease of expression. As such, it was designed for an input in which values of gene expression changes have positive and negative values. To prepare datasets suitable for GSEA, in accordance with our threshold of 200 publications/gene we subtracted 200 from the values of publications/gene, to achieve negative publication values for underexplored genes and positive for well-explored genes. The resulting gene list with publication values was uploaded to GSEA and analyzed against three independent databases: Reactome [

25,

26], KEGG [

27], and Gene Ontology [

28,

29]. Additionally, the shortlist of top genes with the highest number of CGIs (CGI number ≥ 76) and the 10

th percentile lowest number of publications (≤ 20 publications/gene) was uploaded to ShinyGO 8.0 [

30], and enriched functional terms were explored with default settings.

3. Results

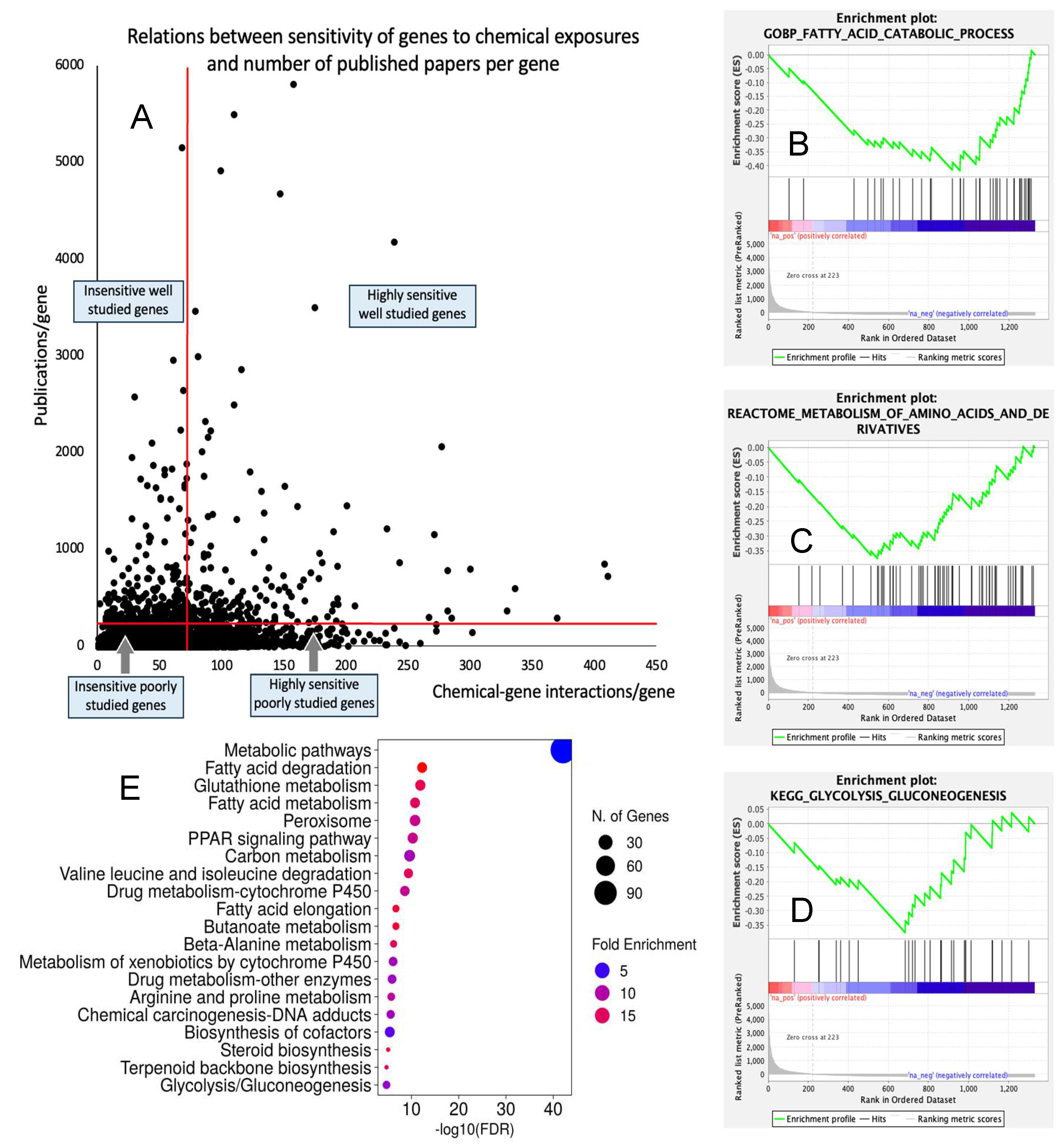

The overlap between the CGI/gene dataset and publication numbers/gene dataset consisted of 16,095 genes. Out of this list, 1,333 (8.3%) and 14,768 (91.7%) genes had high (≥ 73 CGIs) and low (< 73 CGIs] sensitivity to chemical exposures respectively; and 555 (3.5%] and 15,540(96.5%] genes were well explored (≥ 200 publications/gene) and underexplored (< 200 publications/gene) respectively. Among 1,333 chemically sensitive genes, 223 (16.7%) were well explored and 1,110 (83.3%) genes were underexplored. The distribution of chemical sensitivities vs the number of publications per gene is shown in

Figure 1A.

GSEA analysis conducted against three databases of biological pathways/categories retrieved coherent results demonstrating that chemically sensitive underexplored genes are enriched significantly with metabolic categories. Categories that were enriched with FDR q < 0.1 are shown in

Table 1. Specifically, a range of biological categories related to lipid metabolism was significantly enriched. Enriched categories also included the metabolism of amino acids, glucose, and nucleosides (see

Figure 1B-D for representative enrichment plots).

We further used the shortlist of chemically sensitive genes selected based on a stringent criterion for the level of knowledge availability (≤ 20 publications/gene) to identify enriched categories using ShinyGO 8.0. The results of this analysis (

Figure 1E) confirm that underexplored chemically sensitive genes enrich metabolic pathways, including the metabolism of lipids, amino acids, and glucose, along with categories representing the existing focus of toxicology (e.g., glutathione metabolism, cytochrome P450).

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that metabolic pathways, especially the metabolism of fatty acids and amino acids, and to a lesser degree metabolism of glucose are underexplored molecular mechanisms sensitive to chemical exposures. These results are concordant with the traditional structure of toxicology. The field of “metabolic disruption” started to take shape only recently. Indeed the term “metabolic disruption” was first proposed by Casals-Casas and Desvergne in 2011 [

31] and it was further promoted by the group of multidisciplinary experts in 2015 [

32]. PubMed search conducted on 05/16/2024 with the key word “metabolic toxicity” retrieved only 247 studies. For comparison, searchers with the key words “endocrine disruption”, “reproductive toxicity”, “neurotoxicity”, and “carcinogenicity” resulted in 4273, 4944, 91356, and 228470 studies. The Society of Toxicology does not have a specialty section in its structure focusing on metabolic toxicity and most toxicological textbooks do not have chapters focusing on metabolic toxicity as well. The importance of the focus of future efforts on the identification of metabolic molecular mechanisms affected by chemical exposures is dictated by the current epidemic of metabolic disease, one of the biggest public health issues in the modern-day [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

The major limitation of this study consists of the use of existing gene annotations to identify molecular mechanisms associated with underexplored genes. This approach does not allow identification of toxicological mechanisms that are not present in current annotations of underexplored genes. It is reasonable to assume that due to the underexplored nature of these genes, their annotations are far from being complete, and future research may identify other functions of currently underexplored genes. Another limitation is that our crude approach does no allow identification of the role of each gene in the development of toxicity outcomes. Some chemically sensitive genes may be causally involved in toxicities, others may be involved in compensatory responses, and some other genes may be involved in neither but represent a side effect of AOP or compensatory mechanisms activation. Despite these limitations, we suggest that the current analysis identifies underexplored area of toxicology. Additional research effort in this area may provide significant progress and important discoveries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AS; methodology, AS and OA; validation, AS and OA; formal analysis, AS and OA; investigation, AS and OA; resources, AS; data curation, AS and OA; writing—original draft preparation, AS; writing—review and editing, AS and OA; visualization, AS; supervision, AS.; project administration, AS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data on chemical-gene interactions per gene used in this study are available through Mendeley Data [

20]. All data on PubMed publications numbers per gene used in this study are available through

Find My Understudied Genes [FMUG] database [

https://fmug.amaral.northwestern.edu/].

Conflicts of Interest

Alexander Suvorov reports a relationship with ReGENE LLC that includes board membership, equity or stocks, and funding grants. Olatunbosun Arowolo declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Hoffmann, R.; Valencia, A. Life Cycles of Successful Genes. Trends Genet. 2003, 19, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grueneberg, D.A.; Degot, S.; Pearlberg, J.; Li, W.; Davies, J.E.; Baldwin, A.; Endege, W.; Doench, J.; Sawyer, J.; Hu, Y.; et al. Kinase Requirements in Human Cells: I. Comparing Kinase Requirements across Various Cell Types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 16472–16477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.M.; Isserlin, R.; Bader, G.D.; Frye, S.V.; Willson, T.M.; Yu, F.H. Too Many Roads Not Taken. Nature 2011, 470, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, T.I.; Bologa, C.G.; Brunak, S.; Campbell, A.; Gan, G.N.; Gaulton, A.; Gomez, S.M.; Guha, R.; Hersey, A.; Holmes, J.; et al. Unexplored Therapeutic Opportunities in the Human Genome. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeger, T.; Gerlach, M.; Morimoto, R.I.; Nunes Amaral, L.A. Large-Scale Investigation of the Reasons Why Potentially Important Genes Are Ignored. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, T.; Hoffmann, R. Temporal Patterns of Genes in Scientific Publications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 12052–12056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, A.I.; Hogenesch, J.B. Power-Law-like Distributions in Biomedical Publications and Research Funding. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.A.; Tomczak, A.; Khatri, P. Gene Annotation Bias Impedes Biomedical Research. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorov, A.; Salemme, V.; McGaunn, J.; Poluyanoff, A.; Teffera, M.; Amir, S. Unbiased Approach for the Identification of Molecular Mechanisms Sensitive to Chemical Exposures. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arowolo, O.; Salemme, V.; Suvorov, A. Towards Whole Health Toxicology: In-Silico Prediction of Diseases Sensitive to Multi-Chemical Exposures. Toxics 2022, 10, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri, S.; Patton, G.W.; Chanderbhan, R.F.; Mattia, A.; Klaassen, C.D. From Classical Toxicology to Tox21: Some Critical Conceptual and Technological Advances in the Molecular Understanding of the Toxic Response Beginning From the Last Quarter of the 20th Century. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 161, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC <i>Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a, Strategy</i>; National Research Council: Washington, D.C. NRC Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy; National Research Council: Washington, D.C. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vinken, M. The Adverse Outcome Pathway Concept: A Pragmatic Tool in Toxicology. Toxicology 2013, 312, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Revised Guidance Document on Developing and Assessing Adverse Outcome Pathways; OECD Environment, Health and Safety Publications Series on Testing and Assessment No. 184: Paris, France, 2017.

- Ankley, G.T.; Bennett, R.S.; Erickson, R.J.; Hoff, D.J.; Hornung, M.W.; Johnson, R.D.; Mount, D.R.; Nichols, J.W.; Russom, C.L.; Schmieder, P.K.; et al. Adverse Outcome Pathways: A Conceptual Framework to Support Ecotoxicology Research and Risk Assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.C. ToxCast on Target: In Vitro Assays and Computer Modeling Show Promise for Screening Chemicals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, A172–a172a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, D.; Choi, J. Application of ToxCast/Tox21 Data for Toxicity Mechanism-Based Evaluation and Prioritization of Environmental Chemicals: Perspective and Limitations. Toxicol. Vitro Int. J. Publ. Assoc. BIBRA 2022, 84, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorov, A.; Salemme, V.; McGaunn, J.; Poluyanoff, A.; Amir, S. Data on Chemical-Gene Interactions and Biological Categories Enriched with Genes Sensitive to Chemical Exposures. Data Brief 2020, 33, 106398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.P.; Grondin, C.J.; Johnson, R.J.; Sciaky, D.; McMorran, R.; Wiegers, J.; Wiegers, T.C.; Mattingly, C.J. The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database: Update 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D948–D954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorov, A.; Salemme, V.; McGaunn, J.; Poluyanoff, A.; Amir, S.; Arowolo, O. Sensitivity of Genes, Molecular Pathways and Disease Related Categories to Chemical Exposures. 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- Suvorov, A. Simple Method for Cutoff Point Identification in Descriptive High-Throughput Biological Studies. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta-Research: Understudied Genes Are Lost in a Leaky Pipeline between Genome-Wide Assays and Reporting of Results Available online: https://elifesciences.org/reviewed-preprints/93429v1 [accessed on 24 March 2024].

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U A 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V.K.; Lindgren, C.M.; Eriksson, K.F.; Subramanian, A.; Sihag, S.; Lehar, J.; Puigserver, P.; Carlsson, E.; Ridderstrale, M.; Laurila, E.; et al. PGC-1alpha-Responsive Genes Involved in Oxidative Phosphorylation Are Coordinately Downregulated in Human Diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003, 34, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, B.; Matthews, L.; Viteri, G.; Gong, C.; Lorente, P.; Fabregat, A.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Cook, J.; Gillespie, M.; Haw, R.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D498–D503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat, A.; Jupe, S.; Matthews, L.; Sidiropoulos, K.; Gillespie, M.; Garapati, P.; Haw, R.; Jassal, B.; Korninger, F.; May, B.; et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D649–D655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene Ontology: Tool for the Unification of Biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium; Aleksander, S. A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. The Gene Ontology Knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A Graphical Gene-Set Enrichment Tool for Animals and Plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals-Casas, C.; Desvergne, B. Endocrine Disruptors: From Endocrine to Metabolic Disruption. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2011, 73, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindel, J.J.; vom Saal, F.S.; Blumberg, B.; Bovolin, P.; Calamandrei, G.; Ceresini, G.; Cohn, B.A.; Fabbri, E.; Gioiosa, L.; Kassotis, C.; et al. Parma Consensus Statement on Metabolic Disruptors. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2015, 14, 54–015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.W.; Zhuo, X.; Cheng, Y.J.; Albright, A.L.; Narayan, K.M.; Thompson, T.J. Trends in Lifetime Risk and Years of Life Lost Due to Diabetes in the USA, 1985-2011: A Modelling Study. LancetDiabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics, D. of H.I.S. Crude and Age-Adjusted Percentage of Civilian, Noninstitutionalized Adults with Diagnosed Diabetes, United States, 1980–2010.; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Diabetes Translation: Atlanta, GA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Design and Validation of a Histological Scoring System for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatol. Baltim. Md 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, H.M.; Sirlin, C.; Behling, C.; Middleton, M.; Schwimmer, J.B.; Lavine, J.E. Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Critical Appraisal of Current Data and Implications for Future Research. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2006, 43, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obesity and Overweight Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [accessed on 26 March 2024].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author[s] and contributor[s] and not of MDPI and/or the editor[s]. MDPI and/or the editor[s] disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).