1. Introduction

The ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) is a single continuous layer of flat to cuboidal cells weakly attached to the basal membrane that covers the ovary. The OSE is sometimes referred to as mesothelial-type of epithelial cells since it shares a common embryological background and characteristics with peritoneal mesothelial cells (MCs) [

1]. The OSE directly develops from the celomic epithelium. Mullerian duct, an embryological precursor for female reproductive organs, including the fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix and upper vagina also derives from this celomic layer, which has a mesodermal origin [

2,

3,

4]. In fact, the OSE is frequently referred to in the literature as the ovarian mesothelium [

3]. On the other hand, the OSE is continued by the mesovarium, a flat sheet of peritoneum associated with the ovaries that project from the posterior surface of the broad ligament of the uterus. It attaches to the hilum of the ovary, encloses its neurovascular supply, and forms the mesentery of the ovary [

1,

3,

5,

6]. Approximately 90% of ovarian cancer (OC) arises from the OSE, while a small portion originates from germ cells or sex-cord stromal tissues. Epithelial OC is classified in five sub-groups: low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSOC), high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), mucinous, endometroid and clear cell ovarian carcinomas [

7]. HGSOC is the most aggressive, lethal and common subtype of epithelial OC, accounting for about 70% [

5,

8]. HGSOC is thought to arise from either the transformation of ovarian surface cells or from precursor lesions in the fallopian tubal epithelium [

1,

4,

7].

Metastases from the primary ovarian/fallopian tube carcinoma to the peritoneum are highly frequent. The peritoneum is composed of a monolayer of MCs resting on a connective tissue with few fibroblasts, immune cells, adipocytes and vessels [

9]. It includes parietal peritoneum, which covers the internal wall of the abdominal cavity; and visceral peritoneum, that lines the abdominal organs. In ovarian carcinomatosis, cancer cells detach from the primary tumor, disseminate through the peritoneal cavity and attach to and invade trough the mesothelium. Our group described, for the first time, that a sizeable population of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) originated through a mesothelial-to-mesenchymal trasition (MMT) process accumulates in the peritoneal stroma and promotes OC adhesion, invasion, vascularization and growth. MMT is a key event in the pathogenesis of ovarian carcinomatosis [

10,

11,

12]. During MMT, considered as an epitelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like process, MCs lose the apico-basolateral polarity and the intercellular adhesions, changing from a cobblestone-like morphology to a fibroblast-like one. They increase their migration and invasive capacity, invading the submesothelial area, and also enhance production of extracellular matriz (ECM) components [

13]. In parallel, an elevated expression of metalloproteinases (MMPs) that degrade the basement membrane is observable. These changes are the consequence of a profound genetic reprogramming, characterized by the down-regulation of epithelial markers [

14,

15]; and the final acquisition of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) as a marker of myofibroblasts, among others [

16].

CAFs are activated fibroblasts (myofibroblasts) present in the stroma of solid tumors [

17]. CAFs may originally derive from different sources, depending on the cancer type or the individual area within the tumor. The activation of resident fibroblasts has been considered the main origin of CAFs in the tumor microenvironment [

18]. Bone marrow-derived precursors, endothelial cells through an endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndTM), adipocytes [

19], and epithelial cells through EMT have been proposed as alternative resources of myofibroblasts [

12,

20,

21,

22].

Herein, we compared, for the first time, CAFs present in primary ovarian carcinomas with CAFs from peritoneal carcinoma implants. Our results show that CAFs with ovarian localization express mesothelial-related markers in a similar way to CAFs originated through MMT in peritoneal carcinoma implants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Samples and Cell Cultures

Human peritoneal MCs (HPMCs) isolated by digestion of omentum samples from non-oncological patients undergoing abdominal surgery were used as control. Briefly, omentum samples were digested with a 0.25% trypsin solution containing 0.02% EDTA for 15 min with occasional agitation at 37ºC. Cells were cultured in Earle’s M199 medium (Biological Indutries, Beit Haemek, Israel) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2% Biogro-2 (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 ºC.To induce MMT

in vitro, HPMCs were treated with 0.5 ng/mL transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) plus 2.5 ng/mL interleukin-1β (IL-1β; R&D Systems) (T + I), for 72 h, which has been shown to be a suitable MMT model [

23,

24,

25].

CAFs for ex vivo expansion were obtained from fresh tumor tissue samples of epithelial OC patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery. Patients did not received chemotherapy before surgery. Ovarian carcinomas (n=7) and secondary tumors (n=5) were cut in small pieces of approximately 3 mm in diameter and carefully placed on the bottom of high cell bind culture plates (25 cm2 flask; Corning, USA) [

26]. Fibroblast-like cells were allowed to growth out in Earle’s M199 medium (Biological Industries) supplemented with 20% of FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 2% Biogro-2 (Biological Industries), at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until they reached 75% of confluence. The remaining tissue pieces were removed and cells remained stable for at least 2 passages.

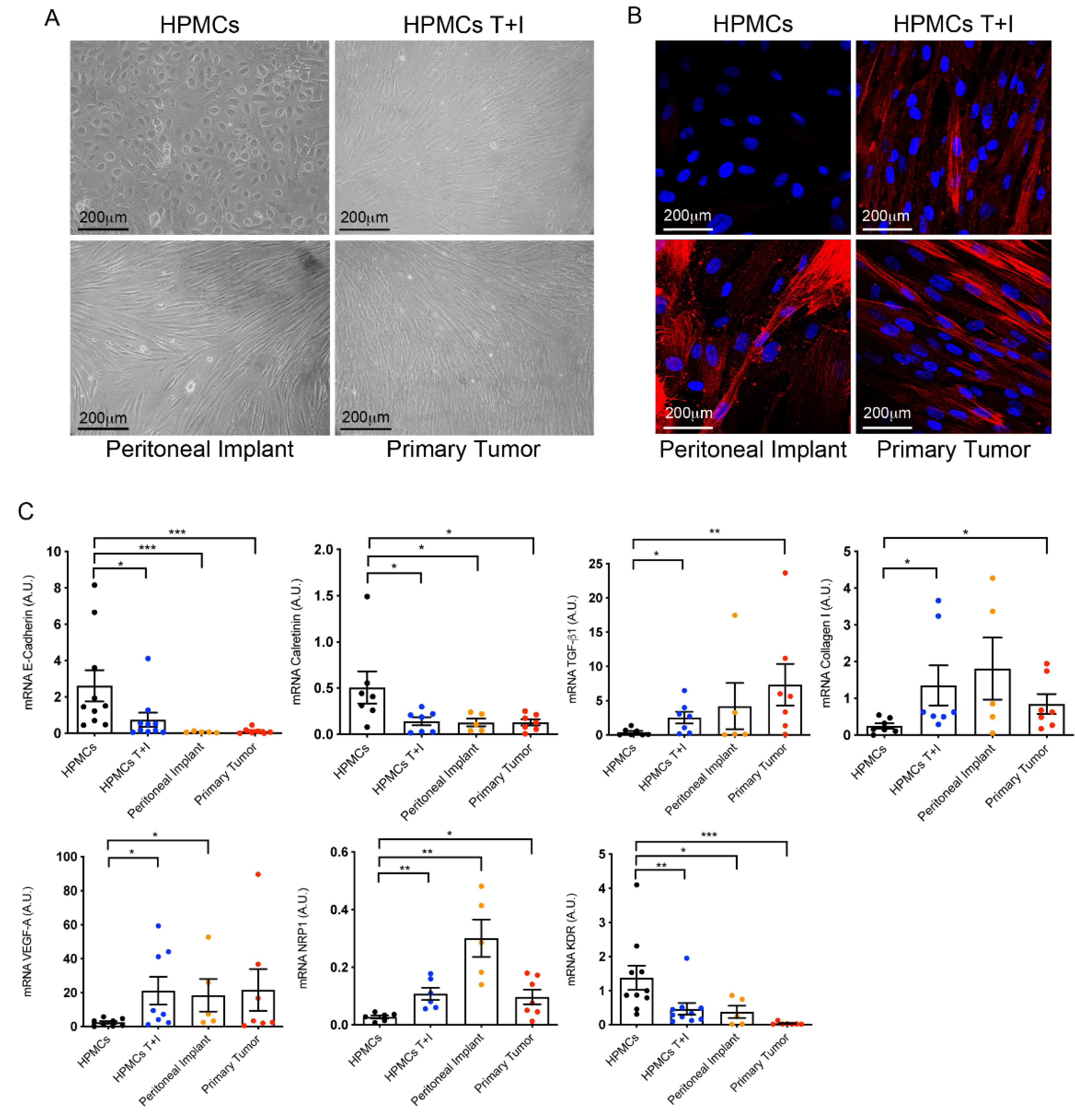

Brightfield images of cell cultures were obtained with 10X objective using a Nikon COOLPIX 4500 camera coupled Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope.

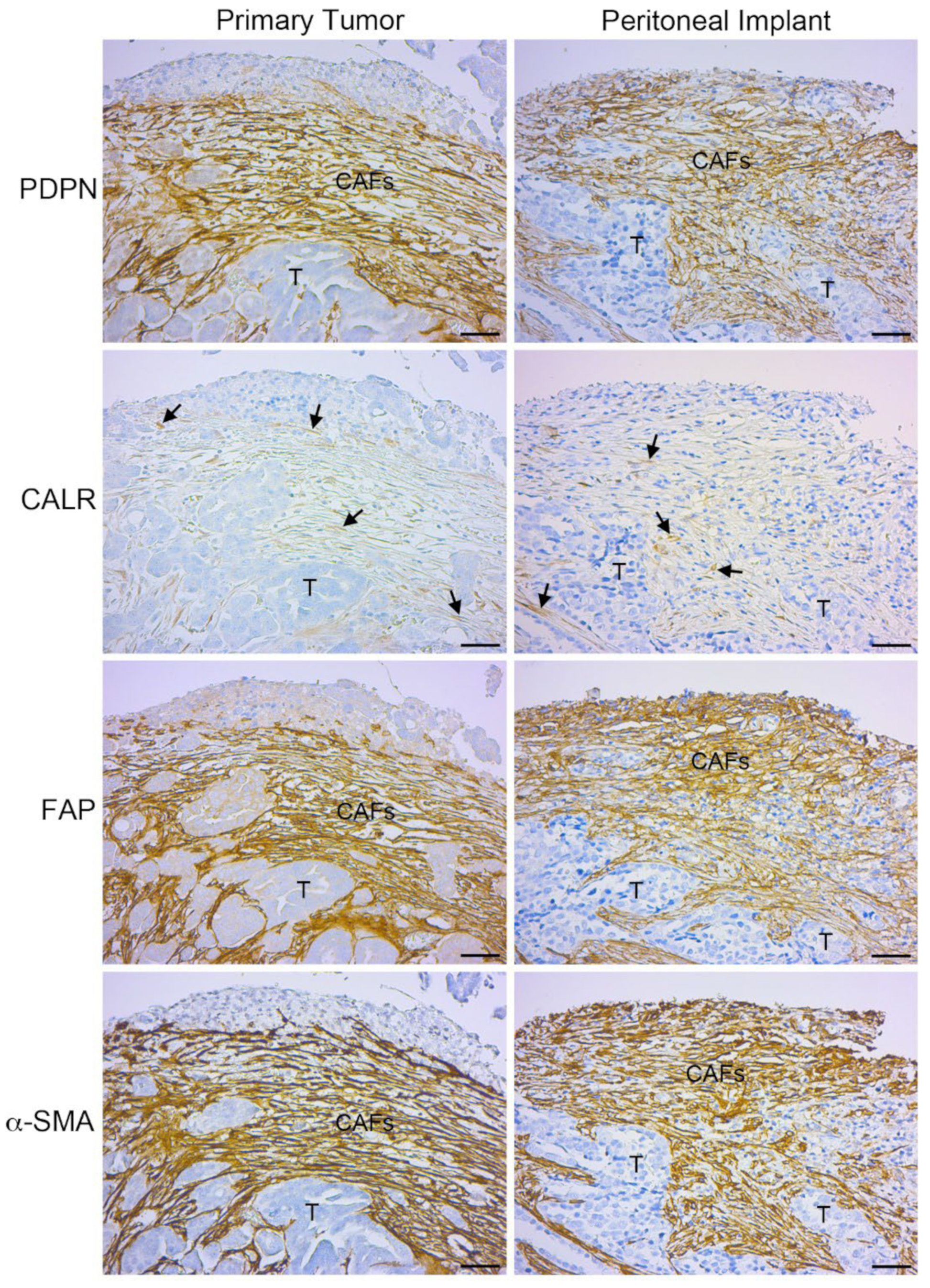

Primary tumor biopsies and their corresponding peritoneal implants from a total of 9 patients with HGSOC were considered for immunohistochemical analysis.

The study was carried out in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and applicable regulations, as well as the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from the patients, with the approval of the Clinical Ethics Committee of the Hospitals Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (ethics approval number: 11.17; Madrid, Spain) and Fundación Jiménez Díaz (ethics approval number: 11/17; Madrid, Spain).

2.2. Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to visualize α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Clone 1A4, 1:3000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) in cell cultures. Cells were plated on 22 mm2 coverslips placed in 24-well tissue culture plates and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Samples were then permeabilised in 0.1% NP-40 and blocked for non-specific unions in 0.1% BSA, 0.2% NP40 and 0.05% Tween 20 diluted in PBS 1x. After the primary antibody, samples were incubated with a secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor-488 (Thermo Scientific). Finally, nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Merck Millipore). Confocal images were captured with a LSM710 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.3. Reverse Transcription—Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

MMT-related mRNAs were analysed by RT-qPCR in cell cultures of HPMCs, peritoneal implants and primary tumors. Cells were lysed in TRIzol Reagent (Ambion, Van Allen Way, Carlsbad CA, USA) and total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Complementary DNA was obtained from 2 µg RNA by reverse transcription (Applied Biosystems, Cheshire, UK). Quantitative PCR was carried out in a LightCycler 480 II (LightCycler 480 1.5.0 software; Roche Diagnostics), using a SYBR Green kit (Roche Diagnostics) and specific primers for E-cadherin (CDH1), calretinin (CALB2), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2/KDR), collagen I (COL1A1), transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), neuropilin 1 (NRP1) and H3 histone (Supplementary Table S1). Samples were normalized with respect to the value obtained for H3 histone.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemical analysis, patient biopsies were fixed in neutral-buffered 3.7% formalin and embedded in paraffin to obtain serial sections 3 m thick. Deparaffinized tissues were heated to expose the hidden antigens using Real Target Retrieval Solution containing citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (Sigma-Aldrich). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with Real Peroxidase-Blocking Solution (Dako). Samples were stained using primary antibodies to detect PDPN (clone NZ-1, 1:500, Origine, Rockville, US), pan-CK (clone PCK-26; Sigma-Aldrich), CALR (clone DC8, Invitrogen by Life Technologies), α-SMA (clone 1A4; Sigma-Aldrich) and FAP (clone EPR20021; Abcam). Biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG, anti-mouse IgG or anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories) was applied to detect primary antibodies. Complexes were visualized using the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Reagent, Peroxidase, R.T.U. (Vector Laboratories) and 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Dako) as chromogen. Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.4.0 (455) for macOS (GraphPad software, San Diego, United States). Results are represented as mean ± SEM in bar graphics. Data groups were compared with the non-parametric Mann–Whitney rank sum U-test. A p-value< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Signs are Detected in CAFs Isolated from Primary Ovarian Tumors

Cells from primary tumors and peritoneal implants showed spindle-like morphology, a similar appearance to that of MCs transdifferentiated in vitro with TGF-β1 plus IL-1β and contrary to control MCs which maintained a cobblestone phenotype (

Figure 1A). The myofibroblast activation of cells was validated by the staining of cultures with α-SMA. As expected transdifferentiated cells isolated from primary tumor tissues and their corresponding peritoneal metastases expressed α-SMA in a similar manner than MCs trasdifferentiated in vitro (

Figure 1B).

At molecular level (

Figure 1C), the expression of E-cadherin, which represents an EMT hallmark, was strongly repressed in cells isolated from primary and secondary tumors as compared to omentum cells. Likewise, calretinin, a recognized mesothelial marker, significantly decreased its expression in cells isolated from both primary and secondary tumor explants. Conversely, primary OC cells showed a significant up-regulation of MMT-associated markers including TGF-β1 and the ECM component collagen I in a similar way that MCs trasdifferentiated

in vitro. Molecular analysis of the angiogenic factor VEGF-A showed that there was a tendency to increase in stromal cells of primary carcinomas as compared to control MCs, although statistical significance was not reached. Regarding the receptor KDR (VEGFR2) and the co-receptor NRP1, implicated in proliferation and invasion, respectively, the former decreased its expression and the latter was augmented as compared with control MCs. Both dysregulations were similar to those observed in MCs transdifferentiated in vitro and CAFs from peritoneal implats.

3.2. Primary Ovarian Carcinomas Show CAFs Expressing Mesothelial Cell Markers

Serial sections showed immunohistochemical staining of mesothelial markers, such as podoplanin (PDPN) and calretinin in fibroblast-like cells located in areas surrounding tumor glands of primary neoplasias and peritoneal metastases (

Figure 2). Of note is the low staining intensity observed for calretinin in the stroma of primary and secondary tumors. This result is consistent with the quantification of calretinin at mRNA level (

Figure 1 C). The co-localization mesothelial markers with active fibroblast markers (FAP and α-SMA) is evident in tumors with ovarian localization and very similar to the staining observed in secondary peritoneal implants (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Ovarian carcinomatosis is a complex metastatic disease involving tumor cells and a supporting stroma formed by a fibrotic, immune and microvascular microenvironment. In the context of OC metastasis, CAFs of mesothelial origin acquire a notorious relevance, since they constitute an important population in the peritoneal environment and play a significant role in OC progression [

26]. MMT has been previously described in peritoneal ascitic fluid samples as well as in peritoneal biopsies from patients with advanced OC [

12,

27,

28]. However, the study of CAFs surrounding the tumor at its primary location (ovary) had been neglected.

Here, we analyzed the expression of MMT-related markers in ex vivo-expanded cells from primary ovarian tumors and compared them with peritoneal explants. The fibroblast-like morphology and expression of αα-SMA indicated that cultured cells were active fibroblasts (myofibroblasts) in both cases. Downregulation of typical mesothelial markers, like e-cadherin and calretinin, as well as the overexpression of mesenchymal markes, including TGF-β1 and collagen I, in fibroblasts isolated from primary tumors suggest an MMT-related signature similar to that observed in MCs stimulated in vitro or in fibroblasts expanded ex vivo from metastatic peritoneal tissues. We have also found an upregulation of VEGF-A and the co-receptor neuropilin-1, as well as an underexpression of the receptor KDR/VEGFR-2 compared to control MCs. On this note, previous studies from our group pointed to mesothelial-derived CAFs as the principal producers of VEGF in the peritoneal metastatic niche [

12,

27]. The functional relevance of the switch of the KDR/VEGFR-2 and neuropilin-1 during MMT has also previously characterized. In fact, the treatment with neutralizing anti-VEGF or anti-Nrp-1 antibodies showed that both molecules play a relevant role driving MCs from a proliferative response to an invasive behavior through the peritoneal membrane [

29].

On the other hand, we have analyzed biopsies of primary ovarian carcinomas for the detection of CAFs expressing mesothelial markers. In this regard, PDPN, which expression in physiological conditions is limited to the mesothelium lining serous cavities and the endothelium of lymphatic vessels [

30,

31,

32,

33], was intensely stained in FAP/α-SMA double positive CAFs in primary and secondary tumors. Interestingly, it was shown that PDPN-positive CAFs can predict poor cancer prognosis [

34]. In this regard, we have recently shown that the immunohistochemical detection of CAFs expressing PDPN is mainly associated to peritoneal implants of aggressive histological subtypes of epithelial OC [

28]. Taken toghether these data it is tempting to think that intratumoral PDPN-positive CAFs could have a mesothelial origin also in primitive neoplasms.

Calretinin is a calcium adhesion protein, which expression in health is mainly related to the nervous system and MCs. In disease, calretinin is expressed in MC neoplasms (mesothelioma) [

35,

36]. However, in peritoneal implants calretinin does not label the epithelial tumor cells and it expression is limited to the sourrounding stroma [

12,

27,

37]. Consistent with the transcriptional data in ex vivo cultures shown above, calretinin weakly labeled stromal zones with PDPN/FAP/α-SMA triple positive CAFs in intraovarian biopsies. This weak staining could be related with a terminal time point of the MMT process, when mesothelial markers are above to become extinct.

Here we used PDPN and calretinin as principal mesothelial markers. Our data suggest that CAFs accompanying primary epithelial ovarian tumors and CAFs sourrounding to peritoneal metastatic implants have a similar mesothelial background. The detection of PDPN and calretinin in intraovarian CAFs suggests that they could derive from the adjacent mesovarium through an MMT process. Of note, PDPN and calretinin are not immunoexpressed in OC cells, being its staining limited to CAFs. In accordance to these results, our group previously demonstrated that CAFs can derive from the MCs that line the visceral peritoneum through an MMT-process in locally advanced primary colorectal carcinomas by means of the submesothelial detection of mesothelial markers, including calretinin, mesothelin and cytokeratin 7 [

38]. However, in the context of OC, PDPN and calretinin are also detectable in the OSE, as well as in the cortical inclusion cysts (formed by invaginations of OSE) [

39]. Therefore, the close similarity of both ovarian-associated surfaces makes difficult to identify with precission the real origin of CAFs in primary OC. The mesenchymal conversion via EMT of the epitelial cells that cover the ovarian surface is a possibility that cannot be discarded. In fact, the mesothelium of continuity and the OSE share the basal expression of several markers, including among others E-cadherin, N-cadherine, cytokeratins, mesothelin, WT1, CA125/MUC16 and neuropilin-1 [

5,

39]. Interenstingly, among these mesothelial/epithelial ovarian surface markers, CA125, N-cadherin, cytokeratins, mesothelin and neuropilin-1 are also frequently detected in epithelial OC cells [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. In fact, ovarian stem cells existing within the OSE may be responsible for epithelial ovarian tumorogenesis by an EMT mechanism [

1,

6]. On the other hand, primary ovarian mesothelioma is a rare event. This evidence would preferentially support an epithelial rather than a mesothelial origin for CAFs [

45]. Further studies by using “omic” technologies that compare expression profiles of CAFs from primary tumors with CAFs from metastatic sites could help to clarify the similarities and/or differences between CAFs with distinct serous location. In addition, the identification of the molecular profile of intraovarian CAFs could be useful for the prediction of OC progression and/or for the availability of design new potential therapeutic targets [

40].

5. Conclusions

This study shows for the first time the presence of CAFs derived through MMT in primary ovarian tumors. They could represent an important value for the early detection of OC and its characterization would help in the design of therapeutic strategies that target them, as CAFs play major roles in the progression of OC. The MMT-targeted treatments could have an impact on patients by decreasing the peritoneal metastasis rate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T-S., J-A.J-H., M.L-C. and P.S.; methodology, H.T-S. and P.S.; formal analysis H.T-S. and P.S.; investigation, H.T-S., M.L-C. and P.S.; biological resources, J-A.J-H., M-C.F-C., I.C-G., R.S-C. and L.G-C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T-S. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, H.T-S., J-A.J-H., M.L-C. and P.S.; supervision, M.L-C. and P.S.; funding acquisition, M.L-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation/Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (MICIN/FEDER), grant number PID2022-142796OB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 to MLC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospitals Puerta Hierro de Majadahonda, Madrid (protocol code 11.17; date 06/12/2017) and Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid (protocol code: 11/17; date 06/13/2017 and protocol code: 19/23; date 10/24/2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Okamura, H.; Katabuchi, H. Pathophysiological Dynamics of Human Ovarian Surface Epithelial Cells in Epithelial Ovarian Carcinogenesis. In International Review of Cytology; Elsevier, 2004; Vol. 242, pp. 1–54 ISBN 978-0-12-364646-0.

- Salamanca, C.M.; Maines-Bandiera, S.L.; Leung, P.C.K.; Hu, Y.-L.; Auersperg, N. Effects of Epidermal Growth Factor/Hydrocortisone on the Growth and Differentiation of Human Ovarian Surface Epithelium. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2004, 11, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auersperg, N.; Wong, A.S.T.; Choi, K.-C.; Kang, S.K.; Leung, P.C.K. Ovarian Surface Epithelium: Biology, Endocrinology, and Pathology*. Endocr. Rev. 2001, 22, 255–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritch, S.J.; Telleria, C.M. The Transcoelomic Ecosystem and Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Dissemination. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 886533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N.; Thompson, E.W.; Quinn, M.A. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Interconversions in Normal Ovarian Surface Epithelium and Ovarian Carcinomas: An Exception to the Norm. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 213, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, T.; Hong, W.; Ye, H.; Hu, C.; Zheng, Y. Mechanism for the Decision of Ovarian Surface Epithelial Stem Cells to Undergo Neo-Oogenesis or Ovarian Tumorigenesis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 50, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoutrop, E.; Moyano-Galceran, L.; Lheureux, S.; Mattsson, J.; Lehti, K.; Dahlstrand, H.; Magalhaes, I. Molecular, Cellular and Systemic Aspects of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer and Its Tumor Microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundfeldt, K. Cell–Cell Adhesion in the Normal Ovary and Ovarian Tumors of Epithelial Origin; an Exception to the Rule. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003, 202, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, N.; Sacchi, G. Atlas of Peritoneal Histology. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2000, 20 Suppl 3, S5–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Antón, L.; Cardeñes, B.; Sainz De La Cuesta, R.; González-Cortijo, L.; López-Cabrera, M.; Cabañas, C.; Sandoval, P. Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Exosomes in Peritoneal Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynne-Vidal, A.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.; Fernández-Chacón, C.; López-Cabrera, M.; Sandoval, P. The Mesothelial Origin of Carcinoma Associated-Fibroblasts in Peritoneal Metastasis. Cancers 2015, 7, 1994–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, P.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A.; Rynne-Vidal, Á.; Pérez-Lozano, M.L.; Gilsanz, Á.; Ruiz-Carpio, V.; Reyes, R.; García-Bordas, J.; Stamatakis, K.; Dotor, J.; et al. Carcinoma-associated Fibroblasts Derive from Mesothelial Cells via Mesothelial-to-mesenchymal Transition in Peritoneal Metastasis. J. Pathol. 2013, 231, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Ramírez-Huesca, M.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A.; Sánchez-Tomero, J.A.; Álvarez, V.; Cirujeda, A.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. Peritoneal Dialysis and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition of Mesothelial Cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perl, A.-K.; Wilgenbus, P.; Dahl, U.; Semb, H.; Christofori, G. A Causal Role for E-Cadherin in the Transition from Adenoma to Carcinoma. Nature 1998, 392, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeichi, M. Morphogenetic Roles of Classic Cadherins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1995, 7, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular Mechanisms of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orimo, A.; Weinberg, R.A. Stromal Fibroblasts in Cancer: A Novel Tumor-Promoting Cell Type. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmouliere, A.; Guyot, C.; Gabbiani, G. The Stroma Reaction Myofibroblast: A Key Player in the Control of Tumor Cell Behavior. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2004, 48, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangoni, R.G.; Korman, B.; Varga, J. Adipocytic Progenitor Cells Give Rise to Pathogenic Myofibroblasts: Adipocyte-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Its Emerging Role in Fibrosis in Multiple Organs. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2020, 22, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangai, T.; Ishii, G.; Kodama, K.; Miyamoto, S.; Aoyagi, Y.; Ito, T.; Magae, J.; Sasaki, H.; Nagashima, T.; Miyazaki, M.; et al. Effect of Differences in Cancer Cells and Tumor Growth Sites on Recruiting Bone Marrow-Derived Endothelial Cells and Myofibroblasts in Cancer-Induced Stroma. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 115, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, G.; Sangai, T.; Ito, T.; Hasebe, T.; Endoh, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Harigaya, K.; Ochiai, A. In Vivo Andin Vitro Characterization of Human Fibroblasts Recruited Selectively into Human Cancer Stroma. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 117, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, E.M.; Potenta, S.; Xie, L.; Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. Discovery of Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition as a Source for Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 10123–10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, P.; Loureiro, J.; González-Mateo, G.; Pérez-Lozano, M.L.; Maldonado-Rodríguez, A.; Sánchez-Tomero, J.A.; Mendoza, L.; Santamaría, B.; Ortiz, A.; Ruíz-Ortega, M.; et al. PPAR-γ Agonist Rosiglitazone Protects Peritoneal Membrane from Dialysis Fluid-Induced Damage. Lab. Invest. 2010, 90, 1517–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, J.; Aguilera, A.; Selgas, R.; Sandoval, P.; Albar-Vizcaíno, P.; Pérez-Lozano, M.L.; Ruiz-Carpio, V.; Majano, P.L.; Lamas, S.; Rodríguez-Pascual, F.; et al. Blocking TGF-Β1 Protects the Peritoneal Membrane from Dialysate-Induced Damage. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 1682–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strippoli, R.; Benedicto, I.; Perez Lozano, M.L.; Pellinen, T.; Sandoval, P.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; Del Pozo, M.A. Inhibition of Transforming Growth Factor-Activated Kinase 1 (TAK1) Blocks and Reverses Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition of Mesothelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, K.; Li, T.-S.; Miura, S.; Hasegawa, Y.; Miura, K. Biological Differences Between Ovarian Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Contralateral Normal Ovary-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rynne-Vidal, A.; Au-Yeung, C.L.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A.; Pérez-Lozano, M.L.; Cremades-Jimeno, L.; Bárcena, C.; Cristóbal-García, I.; Fernández-Chacón, C.; Yeung, T.L.; Mok, S.C.; et al. Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition as a Possible Therapeutic Target in Peritoneal Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer: Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Peritoneal Metastatic Niche. J. Pathol. 2017, 242, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Antón, L.; Sandoval, P.; González-Mateo, G.T.; Kopytina, V.; Tomero-Sanz, H.; Arriero-País, E.M.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A.; Fabre, M.; Egaña, I.; Ferrer, C.; et al. Targeting Carcinoma-associated Mesothelial Cells with Antibody–Drug Conjugates in Ovarian Carcinomatosis. J. Pathol. 2023, 261, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Lozano, M.L.; Sandoval, P.; Rynne-Vidal, Á.; Aguilera, A.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A.; Albar-Vizcaíno, P.; Majano, P.L.; Sánchez-Tomero, J.A.; Selgas, R.; López-Cabrera, M. Functional Relevance of the Switch of VEGF Receptors/Co-Receptors during Peritoneal Dialysis-Induced Mesothelial to Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, M.I.; Millien, G.; Hinds, A.; Cao, Y.; Seldin, D.C.; Williams, M.C. T1α, a Lung Type I Cell Differentiation Gene, Is Required for Normal Lung Cell Proliferation and Alveolus Formation at Birth. Dev. Biol. 2003, 256, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahtab, E.A.F.; Wijffels, M.C.E.F.; Van Den Akker, N.M.S.; Hahurij, N.D.; Lie-Venema, H.; Wisse, L.J.; DeRuiter, M.C.; Uhrin, P.; Zaujec, J.; Binder, B.R.; et al. Cardiac Malformations and Myocardial Abnormalities in Podoplanin Knockout Mouse Embryos: Correlation with Abnormal Epicardial Development. Dev. Dyn. 2008, 237, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, V.; Dadras, S.S.; Johnson, L.A.; Jackson, D.G.; Hong, Y.-K.; Detmar, M. Up-Regulation of the Lymphatic Marker Podoplanin, a Mucin-Type Transmembrane Glycoprotein, in Human Squamous Cell Carcinomas and Germ Cell Tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schacht, V. T1 /Podoplanin Deficiency Disrupts Normal Lymphatic Vasculature Formation and Causes Lymphedema. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Zhong, K.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.; Huang, L. Podoplanin-Positive Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Predict Poor Prognosis in Lung Cancer Patients. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, Volume 11, 5607–5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doglioni, C.; Dei, A.P.; Laurino, L.; Iuzzolino, P.; Chiarelli, C.; Celio, M.R.; Viale, G. Calretinin: A Novel Immunocytochemical Marker for Mesothelioma: Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1996, 20, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotzos, V.; Vogt, P.; Celio, M.R. The Calcium Binding Protein Calretinin Is a Selective Marker for Malignant Pleural Mesotheliomas of the Epithelial Type. Pathol. - Res. Pract. 1996, 192, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.S.; Leong, A.S.-Y.; Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, I.; Ahn, G.H.; Kim, H.S.; Chun, Y.K. Calretinin, CD34, and α-Smooth Muscle Actin in the Identification of Peritoneal Invasive Implants of Serous Borderline Tumors of the Ovary. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordillo, C.H.; Sandoval, P.; Muñoz-Hernández, P.; Pascual-Antón, L.; López-Cabrera, M.; Jiménez-Heffernan, J.A. Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Contributes to the Generation of Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts in Locally Advanced Primary Colorectal Carcinomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto Mesenchymal to Epithelial Transition in the Human Ovarian Surface Epithelium Focusing on Inclusion Cysts. Oncol. Rep. 2009, 21. [CrossRef]

- Bast, R.C.; Klug, T.L.; John, E.St.; Jenison, E.; Niloff, J.M.; Lazarus, H.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Leavitt, T.; Griffiths, C.T.; Parker, L.; et al. A Radioimmunoassay Using a Monoclonal Antibody to Monitor the Course of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 309, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assidi, M. High N-Cadherin Protein Expression in Ovarian Cancer Predicts Poor Survival and Triggers Cell Invasion. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 870820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, M.A.; Robertson, D.I. The Cytokeratin Profiles of Ovarian Common “Epithelial” Tumors. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 1989, 10, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassan, R.; Kreitman, R.J.; Pastan, I.; Willingham, M.C. Localization of Mesothelin in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2005, 13, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Xi, Q.; Wang, F.; Sun, Z.; Huang, Z.; Qi, L. Increased Expression of Neuropilin 1 Is Associated with Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimercati, L.; Cavone, D.; Delfino, M.C.; Bruni, B.; De Maria, L.; Caputi, A.; Sponselli, S.; Rossi, R.; Resta, L.; Fortarezza, F.; et al. Primary Ovarian Mesothelioma: A Case Series with Electron Microscopy Examination and Review of the Literature. Cancers 2021, 13, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).