Submitted:

29 May 2024

Posted:

30 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. The Foundations: From LUCA to LECA

2.1. Six Central Pathways to Be Coordinated

2.2. Coordination Hub-1 in LECA: The RB-E2F Pathway

2.3. Two Additional Coordination Hubs in LECA: PTEN and TOR

3. New Coordination Challenges and Solutions in Metazoans

3.1. Sex and Soma-Germline Differentiation as Stress Response

3.2. Programmed Cell Death as Stress Response

3.3. The New Coordination Hub in Metazoans: p53

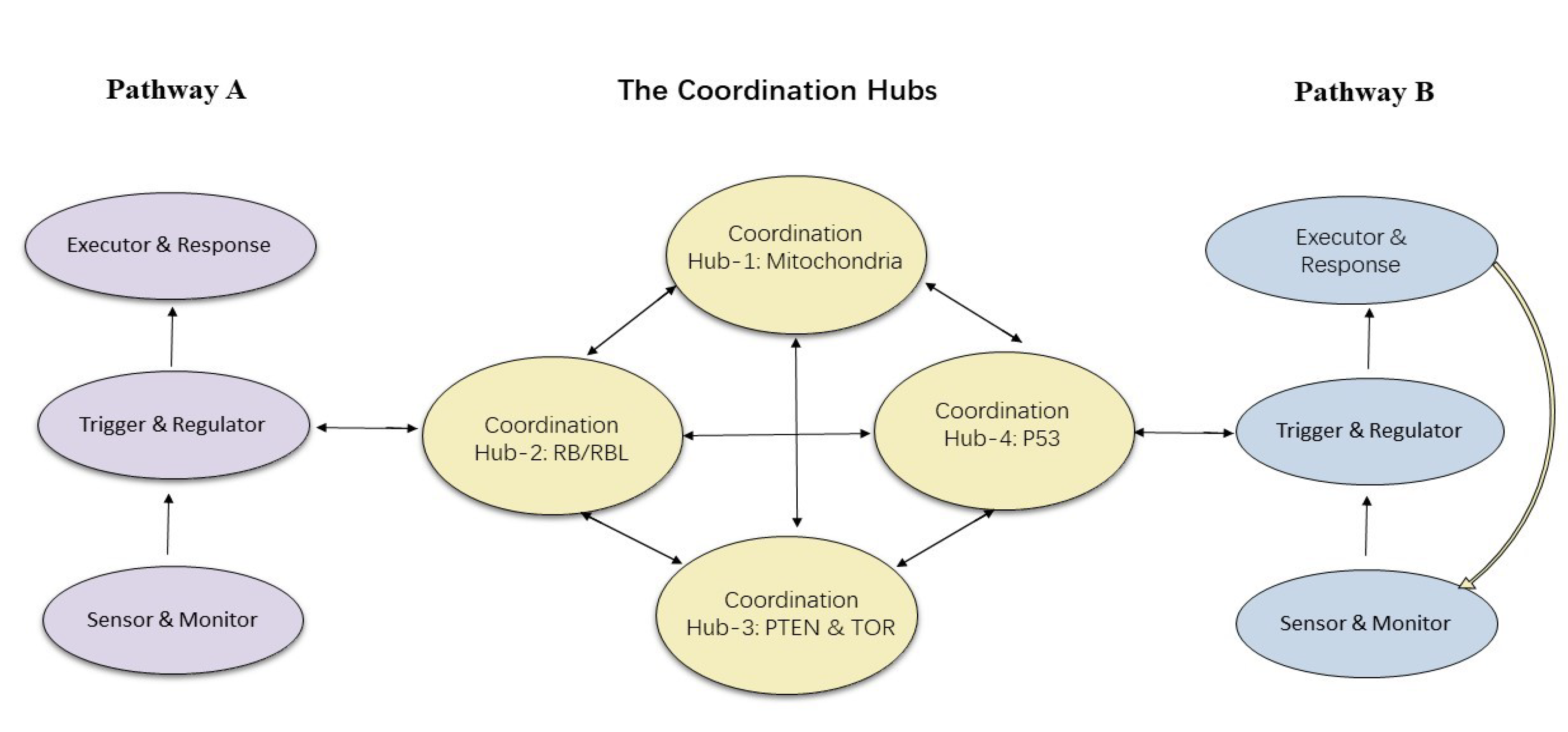

4. Coordination in Metazoans: Cross-Talk and Communication

4.1. Crosstalk: Direct

4.2. Crosstalk: Indirect

4.3. Communications

4.4. Why Are the Mitochondria So Central to the Coordination Network in Metazoans?

5. Discussion

5.1. Principal Implications

5.2. Implications for Understanding Aging, Cancer, and Lifespan

References

- Åberg, E.; Saccoccia, F.; Grabherr, M.; Ore, W.Y.J.; Jemth, P.; Hultqvist, G. Evolution of the p53-MDM2 pathway. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2017, 17, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamska, M. (2015). Developmental signaling and the emergence of animal multicellularity. In I. Ruiz-Trillo, & A. M. Nedelcu. (Eds.), Evolutionary transition to multicellular life: Principles and mechanisms (pp. 425–450). Springer.

- Aitken, R.J.; Findlay, J.K.; Hutt, K.J.; Kerr, J.B. Apoptosis in the germ line. Reproduction 2011, 141, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åkerfelt, M.; Morimoto, R.I.; Lea Sistonen. Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development, and lifespan. Nature Reviews, Molecular Cell Biology 2010, 11, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktipis, C.A.; Boddy, A.M.; Jansen, G.; Hibner, U.; Hochberg, M.E.; Maley, C.C.; et al. Cancer across the tree of life: Cooperation and cheating in multicellularity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 370, 20140219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, A.S. Cellular hyperproliferation and cancer as evolutionary variables. Current Biology 2012, 22, R772–R778. [Google Scholar]

- Ameisen, J.C. The origin of programmed cell death. Science 1996, 272, 1278–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameisen, J.C. On the origin, evolution, and nature of programmed cell death: A timeline of four billion years. Cell Death Differ 2002, 9, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S.S.; Wiley, H.S.; Sauro, H.M. Design patterns of biological cells. BioEssays 2024, 46, 2300188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aouacheria, A.; de Laval, W.R.; Combet, C.; Hardwick, J.M. Evolution of Bcl-2 homology motifs: homology versus homoplasy. Trends in Cell Biology 2013, 23, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardi, L.D.; Sage, J. RB goes mitochondrial. Genes & Development 2013, 27, 975–979. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Auger, J-P.; et al. 2024. Metabolic rewiring promotes anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Banjara, S.; Suraweera, C.D.; Hinds, M.G.; Kvansakul, M. The Bcl-2 Family: Ancient Origins, Conserved Structures, and Divergent Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Greenwood, J.; Jones, A.W.; et al. Core control principles of the eukaryotic cell cycle. Nature 2022, 607, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, J.S.; George, J.P. S.; Mccall, K. Programmed cell death in the germline. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2005, 16, 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Bayles, K.W. Bacterial programmed cell death: Making sense of a paradox. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2014, 12, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, E.M.; Platanias, L.C. The evolution of the TOR pathway and its role in cancer. Oncogene 2013, 32, 3923–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechtel, W. Analysing network models to make discoveries about biological mechanisms. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 2019, 70, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, W. Hierarchy and levels: analysing networks to study mechanisms in molecular biology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B 2020, 375, 20190320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beere, H.M.; Wolf, B.B.; Cain, K.; Mossert, D.D.; Mahboubi, A.; Kuwana, T.; Tailor, P.; Morimoto, R.I.; Cohen, G.M.; Green, D.R. Heat-shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis by preventing recruitment of procaspase-9 to the Apaf-1 apoptosome. Nature Cell Biology 2010, 2, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyi, V.A.; Ak, P.; Markert, E.; Wang, H.; Hu, W.; Puzio-Kuter, A.; et al. The origins and evolution of the p53 family of genes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2010, 2, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 22. Berenguer, Marie, & Duester, G. Retinoic Acid, RARs and early development. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology, 2022; 69, T59–T67. [CrossRef]

- Berthelet, J.; Dubrez, L. Regulation of apoptosis by inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs). Cells 2013, 2, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertheloot, D.; Latz, E.; Franklin, B.S. Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell death. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 2021, 18, 1106–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla, U.S. Understanding complex signaling networks through models and metaphors. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2003, 81, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Ghosh, M.K. HAUSP, a novel deubiquitinase for Rb-MDM2 the critical regulator. FEBS Journal 2014, 281, 3061–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialik, S.; Zalckvar, E.; Ber, Y.; Rubinstein, A.D.; Kimchi, A. Systems biology analysis of programmed cell death. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2010, 35, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, S.; Harashima, H.; Chen, P.; Heese, M.; Bouyer, D.; Sofroni, K.; Schnittger, A. The retinoblastoma homolog RBR1 mediates localization of the repair protein RAD51 to DNA lesions in Arabidopsis. EMBO Journal 2017, 36, 1279–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglou, S.G.; Bendena, W.G.; Chin-Sang, I. An overview of the insulin signaling pathway in model organisms drosophila melanogaster and caenorhabditis elegans. Peptides 2021, 145, 170640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, F.J.; Tait, S.W. G. Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nature Review Molecular Cell Biology 2020, 21, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.; Doolittle, W.F. Eukaryogenesis, how special really? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 2015; 112, 10278–10285. [Google Scholar]

- Böttger, A.; Alexandrova, O. Programmed cell death in Hydra. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2007, 17, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, C.; Gu, W. P53 regulation by ubiquitin. Febs Letters 2011, 585, 2803–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broz, D.K.; Mello, S.S.; Bieging, K.T.; Jiang, D.; Dusek, R.L.; Brady, C.A.; et al. Global genomic profiling reveals an extensive p53-regulated autophagy program contributing to key p53 responses. Genes & Development 2013, 27, 1016–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, T.; Larson, B.T.; Linden, T.A.; Vermeij, M.J. A.; Mcdonald, K.; King, N. Light-regulated collective contractility in a multicellular choanoflagellate. Science 2019, 366, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, J. Cancer and ageing: rival demons? Nature Reviews, Cancer 2003, 3, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Peng, B.; Yao, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, K.; Yang, X.; Yu, L. The ancient function of RB-E2F Pathway: Insights from its evolutionary history. Biology Direct 2010, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalhoub, N.; Baker, S.J. PTEN and the PI3-Kinase Pathway in Cancer. Annual. Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2009, 4, 127–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandel, N.S. Evolution of mitochondria as signaling organelles. Cell Metabolism 2015, 22, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, J.; He, L. & Stiles, B.L. PTEN: Tumor suppressor and metabolic regulator. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2018, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chinnadurai, G.; Vijayalingam, S.; Gibson, S.B. BNIP3 subfamily BH3-only proteins: mitochondrial stress sensors in normal and pathological functions. Oncogene 2008, 27, S114–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipuk JE, Bouchier-Hayes L, Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD, Green DR. PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science 2005, 309, 1732–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, L.A.; Vertegaal, A.C. O. ; (2024). SUMO proteases: from cellular functions to disease. Trends in Cell Biology, 20. [CrossRef]

- Conlin, P.L.; Ratcliff, W.C. (2016). Trade-offs drive the evolution of increased complexity in nascent multicellular digital organisms. In K. J. Niklas, & S. A. Newman (Eds.), Multicellularity: Origins and evolution (pp. 131–149). MIT Press.

- Crighton, D.; O' Prey, J.; Bell, H.S.; Ryan, K.M. P73 regulates DRAM-independent autophagy that does not contribute to programmed cell death. Cell Death & Differentiation 2007, 14, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Crighton, D.; Wilkinson, S.; Ryan, K.M. DRAM links autophagy to p53 and programmed cell death. Autophagy 2007, 3, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crighton, D.; Wilkinson, S.; O' Prey, J.; Syed, N.; Smith, P.; Harrison, P.R.; et al. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell 2006, 126, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Cohen, M.L.; Teng, C.; Han, M. The tumor suppressor Rb critically regulates starvation-induced stress response in C. elegans. Current Biology 2013, 23, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacks, J.B.; Mark C., F.; Buick, R.; Eme, L.; Gribaldo, S.; Roger, A.J.; Brochier-Armanet, C.; Devos, D.M. The changing view of eukaryogenesis – fossils, cells, lineages and how they all come together. Journal of Cell Science 2016, 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dam, T.J. P. V.; Zwartkruis, F.J. T.; Bos, J.L.; Snel, B. Evolution of the TOR pathway. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2011, 73, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Danko, M.; Kozlowski, J.; Schaible, R. Unraveling the non-senescence phenomenon in Hydra. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2015, 382, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, R. Neuroimmune Interaction: from the Brain to the Immune System and vice versa. Physiology Review 2018, 98, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, E.H.; Erwin, D.H. Gene Regulatory Networks and the Evolution of Animal Body Plans. Science 2006, 311, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mendoza, A.; Suga, H.; Permanyer, J.; Irimia, M.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. Complex transcriptional regulation and independent evolution of fungal-like traits in a relative of animals. eLife, 2015, 4, e08904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Vecchio, D.; Ninfa, A.J.; Sontag, E.D. Modular cell biology: Retroactivity and insulation. Molecular Systems Biology 2008, 4, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desvoyes, B.; Fernández-Marcos, M.; Sequeira-Mendes, J.; Otero, S.; Vergara, Z.; Gutierrez, C. Looking at plant cell cycle from the chromatin window. Frontiers in Plant Science 2014, 5, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, F.A.; Rubin, S.M. Molecular mechanisms underlying RB protein function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2013, 14, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazet-Lošo, T.; Tautz, D. Phylostratigraphic tracking of cancer genes suggests a link to the emergence of multicellularity in metazoan. BMC Biology 2010, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doonan, J.H.; Sablowski, R. 2010. Walls around tumors — why plants do not develop cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer, 10, 794–802.

- Dötsch, V.; Bernassola, F.; Coutandin, D.; Candi, E.; Melino, G. P63 and p73, the ancestors of p53. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2010, 2, a004887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrand, P.M.; Ramsey, G. The nature of programmed cell death. Biological Theory 2019, 14, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifer, K. & Vertegaal, A.C.O. SUMOylation-Mediated Regulation of Cell Cycle Progression and Cancer. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2015, 40, 779–793. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg-Lerner, A.; Bialik, S.; Simon, H-U. ; Kimchi, A. Life and death partners: Apoptosis, autophagy and the cross-talk between them. Cell Death & Differentiation 2009, 16, 966–975. [Google Scholar]

- Emanuele, M.J.; Enrico, T.P.; Mouery, R.D.; Wasserman, D.; Nachum, S.; Tzur, A. (2020) Complex Cartography: Regulation of E2F transcription factors by Cyclin F and Ubiquitin. Trends in Cell Biology, 30 (8), 640–652. [CrossRef]

- Engeland, K. Cell cycle regulation: P53-p21-RB signaling. Cell Death & Differentiation 2022, 29, 946–960. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, S.R.; Chen, Z.; Kramer, E.; Zeng, Q.; Young, S.; Robertson, H.M.; et al. Premetazoan genome evolution and the regulation of cell differentiation in the choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta. Genome Biology 2013, 14, R15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Kraynak, J.; Knisely, J.P. S.; Formenti, S.C.; Shen, W.H. PTEN as a guardian of the genome: Pathways and targets. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2020, 10, a036194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Majada, V.; Welz, P.S.; Ermolaeva, M.A.; Schell, M.; Adam, A.; Dietlein, F.; et al. The tumor suppressor CYLD regulates the p53 DNA damage response. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Serrano, M.; Blasco, M.A. The common biology of cancer and ageing. Nature 2007, 448, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, D.T.; Li, S.C.; Yashiroda, Y.; Yoshimura, M.; Li, Z.; Isuhuaylas, L.A. V.; et al. BIONIC: Biological network integration using convolutions. Nature Methods 2022, 19, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, R.; Serrano-Marin, J. The unbroken Krebs cycle. Hormonal-like regulation and mitochondrial signaling to control mitophagy and prevent cell death. BioEssays 2022, 45, 2200194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, Y.; Steller, H. Live to die another way: Modes of programmed cell death and the signals emanating from dying cells. Nature Review Molecular Cell Biology 2015, 16, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.C.; Olson, C.A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease, Nature Neuroscience 2017, 20, 145–155. 20. [CrossRef]

- Gaddy, M.A.; Kuang, S.; Alfhili, M.A.; Lee, M.H. The soma-germline communication: Implications for somatic and reproductive aging. BMB Reports, 2021, 54, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacinti, C.; Giordano, A. RB and cell cycle progression. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5220–5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Common and divergent functions of Beclin 1 and Beclin 2. Cell Research 2013, 23, 1341–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey-Smith, P. (2009). Darwinian Populations and Natural Selection. Cambridge University Press.

- Gonzalez, S.; Rallis, C. The TOR signaling pathway in spatial and temporal control of cell size and growth. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2017, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goul, C.; Peruzzo, R.; Zoncu, R. The molecular basis of nutrient sensing and signaling by mTORC1 in metabolism regulation and disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023, 24, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Bové, X.; Sebé-Pedrós, A.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. The Eukaryotic ancestor had a complex ubiquitin signaling system of archaeal origin. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2014, 32, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.; Şerban, M.; Scholl, R.; Jones, N.; Brigandt, I.; Bechtel, W. Network analyses in systems biology: New strategies for dealing with biological complexity. Synthese 2018, 195, 1751–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.J.; Zhang, X.D.; Sun, W.; Qi, L. ; Wu, J-C.; and Qin, Z-H. (2015). DRAM1 regulates apoptosis through increasing protein levels and lysosomal localization of BAX. Cell Death & Disease, 2015; 6, e1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; White, E. Autophagy, metabolism, and cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 2016, 81, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwon, Y.; Maxwell, B.A.; Kolaitis, R.; Zhang, P.; Kim, H.J. & Taylor, J.P. (2021) Ubiquitination of G3BP1 mediates stress granule disassembly in a context-specific manner. Science, 2021; 372, eabf6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, A. Retinoblastoma-related proteins in lower eukaryotes. Communicative & Integrative Biology 2009, 2, 538–544. [Google Scholar]

- Harashima, H.; Sugimoto, K. Integration of developmental and environmental signals into cell proliferation and differentiation through retinoblastoma-related 1. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2016, 29, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harputlugil, E.; Hine, C.; Vargas, D.; Robertson, L.; Manning, B.D.; Mitchell, J.R. The TSC complex is required for the benefits of dietary protein restriction on stress resistance in vivo. Cell Reports 2014, 8, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwell, L.H.; Hopfield, J.J.; Leibler, S.; Murray, A.W. From molecular to modular cell biology. Nature 1999, 402 (suppl 6761), 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.M.; Brocca, S.; Sacco, E.; Spinelli, M.; Papaleo, E.; Lambrughi, M.; et al. A comparative study of Whi5 and retinoblastoma proteins: From sequence and structure analysis to intracellular networks. Frontiers in Physiology 2014, 4, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, M.A. Chapter 1- Introduction to autophagy: Cancer, other pathologies, inflammation, immunity, infection and aging, vol. 1–4. Autophagy: Cancer, Other Pathologies, Inflammation, Immunity, Infection, and Aging 2014, 35, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, C.S.; Low, D.A. Signals of growth regulation in bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2009, 12, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, C.M.; Ron, D. The mitochondrial UPR-protecting organelle protein homeostasis. Journal of Cell Science 2010, 123, 3849–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; et al. Beclin 2 functions in autophagy, degradation of G protein-coupled receptors, and metabolism. Cell 2013, 154, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, L.L. M.; Jones, N.S.; Fricker, M.D. A mechanistic explanation of the transition to simple multicellularity in fungi. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, I.A. & Vertegaal, A. C. O. A comprehensive compilation of SUMO proteomics Nature Reviews, Cell and Molecular Biology 2022, 23, 715–731. [Google Scholar]

- Hernansaiz-Ballesteros, R.D.; Földi, C.; Cardelli, L.; et al. (2021) Evolution of opposing regulatory interactions underlies the emergence of eukaryotic cell cycle checkpoints. Scientic Report, 11, 11122. [CrossRef]

- Herron, M.D. What are the major transitions. Biology & Philosophy 2021, 36, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Herron, M.D.; Borin, J.M.; Boswell, J.C.; Walker, J.; Chen, I-C. K.; Knox, C.A.; et al. (2019). De novo origins of multicellularity in response to predation. Scientific Reports 9, 2328. [PubMed]

- Hilgendorf, K.I.; Leshchiner, E.S.; Nedelcu, S.; Maynard, M.A.; Calo, E.; Ianari, A.; Walensky, L.D. & Lees, J.A. The retinoblastoma protein induces apoptosis directly at the mitochondria. Genes & Development 2013, 27, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoareau, M.; Rincheval-Arnold, A. Gaumer, & S. Guénal, I. DREAM a little dREAM of DRM: Model organisms and conservation of DREAM-like complexes. Bioessays 2023, 46, 2300125. [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser, M. Origin and function of ubiquitin-like proteins. Nature 2009, 458, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmeyer, T.T.; Burkhardt, P. Choanoflagellate models- Monosiga brevicollis and Salpingoeca rosetta. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2016, 39, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, K. The evolutionary origins of programmed cell death Signaling. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2020, 12, a036442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.D.; Hodakoski, C.; Barrows, D.; Mense, S.M.; Parsons, R.E. PTEN function, the long and the short of it. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2014, 39, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Kaluarachchi, S.; van Dyk, D.; Friesen, H.; Sopko, R.; Ye, W.; et al. Dual regulation by pairs of cyclin-dependent protein kinases and histone deacetylases controls G1 transcription in budding yeast. PLoS Biology 2009, 7, e1000188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Ma, X.; Zhao, Y.; Miao, L. The C. elegans homolog of RBBP6 (RBPL-1) regulates fertility through controlling cell proliferation in the germline and nutrient synthesis in the Intestine. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, S.R.; Miller, W.T. Receptor tyrosine kinases: mechanisms of activation and signaling. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2007, 19, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husnjak, K.; Dikic, I. Ubiquitin-Binding Proteins: Decoders of Ubiquitin-Mediated Cellular Functions. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2012, 81, 291–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, R.H.; Caceres, E.F.; Escasinas, A.; Alhasan, H.; Howard, J.A.; Deery, M.J.; Ettema, T.I. J.; Robinson, N.P. (2017) Functional reconstruction of a eukaryotic-like E1/E2/(RING) E3 ubiquitylation cascade from an uncultured archaeon. Nature Communications, 8, 1120. [CrossRef]

- Jékely, G. Evolution: How not to become an animal. Current Biology 2019, 29, R1240–R1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Martin, V.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; Johnson, D.G.; Alonso, M.; White, E.; et al. The RB-E2F1 pathway regulates autophagy. Cancer Research 2010, 70, 7882–7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, D. (2015). In I. Ruiz-Trillo, & A. M. Nedelcu. (Eds.), Evolutionary transition to multicellular life: Principles and mechanisms (pp. 451-468). Springer.

- Kauffman, S.A. (1993). The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Kawabe, Y.; Schilde, C. ; Chen, Z-H.; Du, Q.; Schaap. P.; et al. (2015). The Evolution of Developmental Signaling in Dictyostelia from an Amoebozoan Stress Response. In I. Ruiz-Trillo, & A. M. Nedelcu. (Eds.), Evolutionary transition to multicellular life: Principles and mechanisms (pp. 451-468). Springer.

- Kennedy, D.; Jäger, R.; Mosser, D.D.; Afshin Samali. Regulation of apoptosis by heat shock proteins. IUMBM Life 2014, 66, 327–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, L.N.; Leone, G. The broken cycle: E2F dysfunction in cancer. Nature Review Cancer 2019, 19, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerszberg, M.; Wolpert, L. The Origin of Metazoa and the Egg: a Role for Cell Death. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1998, 193, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Nikkanen, J.; Yatsuga, S.; Jackson, C.; Wang, L.; Pradhan, S.; et al. MTORC1 regulates mitochondrial integrated stress response and mitochondrial myopathy progression. Cell Metabolism 2017, 26, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.Y.; Sharpless, N.E. The regulation of INK4/ARF in cancer and aging. Cell 2006, 127, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. Cancer-susceptibility genes. Gatekeepers and caretakers. Nature 1997, 386, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, T.B. L. The evolution of aging. Nature 1977, 270, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, T.B. L. The odd science of aging. Cell 2005, 120, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, T.B. L.; Austad, S.N. Why do we age? Nature 2000, 408, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klim, J.; Gladki, A.; Kucharczyk, R.; Zielenkiewicz, U.; Kaczanowski, S. Ancestral state reconstruction of the apoptosis machinery in the common ancestor of eukaryotes. G3 (Bethesda) 2018, 8, 2121–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoll, A.H. The multiple origins of complex multicellularity. Annual Review of Earth & Planetary Sciences 2011, 39, 217–239. [Google Scholar]

- Komander, D.; Rape, M. The Ubiquitin Code. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2012, 81, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, K.; Miyashita, T.; Hang, H.; Hopkins, K.M.; Zheng, W.; Cuddeback, S.; et al. Human homologue of S. pombe Rad9 interacts with BCL-2/BCL-xL and promotes apoptosis. Nature Cell Biology 2000, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, S.G.; Nedelcu, A.M. (2016). The mechanistic basis for the evolution of soma during the transition to multicellularity in the volvocine algae. In K. J. Niklas, & S. A. Newman (Eds.), Multicellularity: Origins and evolution (pp. 43–71). The MIT Press.

- König, S.G.; Nedelcu, A.M. The genetic basis for the evolution of soma: Mechanistic evidence for the co-option of a stress-induced gene into a developmental master regulator. Proceedings of the Royal Society. Biological sciences 2020, 287, 20201414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V.; Aravind, L. Origin and evolution of eukaryotic apoptosis: The bacterial connection. Cell Death and Differentiation 2002, 9, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V.; Yutin, N. The dispersed archaeal eukaryome and the complex archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2014, 6, a016188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, L.J.; Herrera, M.G.; Winkhofer, K.F. The Role of Ubiquitin in Regulating Stress Granule Dynamics. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13, 910759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G.; Levine, B. Autophagic cell death: The story of a misnomer. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2008, 9, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G.; Marino, G.; Levine, B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Molecular Cell 2010, 40, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbadia, J.; Morimoto, R.I. Repression of the Heat Shock Response Is a Programmed Event at the Onset of Reproduction. Molecular Cell 2015, 59, 639–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbadia, J.; Brielmann, R.M.; Neto, M.F.; Lin, Y.F.; Haynes, C.M.; Morimoto, R.I. Mitochondrial stress restores the heat shock response and prevents proteostasis collapse during aging. Cell Reports 2017, 21, 1481–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labi, V.; Erlacher, M. How cell death shapes cancer. Cell Death & Disease 2015, 6, e1675. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, E.W.; Brosens, J.J.; Gomes, A.R.; Koo, C. Forkhead box proteins: Tuning forks for transcriptional harmony. Nature Reviews Cancer 2013, 13, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.P.; Verma, C. Mdm2 in evolution. Genes& Cancer 2012, 3, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, N. (2015) Lane, N. (2015). The vital question: Energy, evolution, and the origins of complex life. W. W. Norton & Co.

- Lane, N.; Martin, W. The energetics of genome complexity. Nature 2010, 467, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavie, J.; De Belvalet, H.; Sonon, S.; Ion, A.M.; Dumon, E.; Melser, S.; et al. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of mitochondrial proteins regulates energy metabolism. Cell Reports 2018, 23, 2852–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lean, C.; Plutynski. A. The evolution of failure: explaining cancer as an evolutionary process. Biology and Philosophy 2016, 31, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Chen, M, & Pandolfi, P. P. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumor suppressor: New modes and prospects. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 19, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, T. C, & King, N. Evidence for sex and recombination in the choanoflagellate salpingoeca rosetta. Current Biology 2013, 23, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levin, T.C.; Greaney, A.J.; Wetzel, L.; King, N. The rosetteless gene controls development in the choanoflagellate S. rosetta. eLife 2014, 3, e04070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, A.J. ; p53: 800 million years of evolution and 40 years of discovery. Nature Reviews Cancer 2020, 20, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.B.; et al. The role of RAD9 in tumorigenesis. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology 2011, 3, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.B.; et al. p53 and RAD9, the DNA Damage Response, and Regulation of Transcription Networks. Radiation Research 2017, 187, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. MTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. ” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2020, 21, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, K.M.; van Amerongen, R.; Nusse, R. Generating cellular diversity and spatial form: Wnt signaling and the evolution of multicellular animals. Developmental Cell 2016, 38, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomonosova, E.; and Chinnadurai, G. BH3-only proteins in apoptosis and beyond: an overview. Oncogene 2009, 27, S2–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, G.; Levin, A.J. (2016) The p53 protein: from cell regulation to cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine.

- Luo, A.; et al. H2B ubiquitination recruits FACT to maintain a stable altered nucleosome state for transcriptional activation. Nature Communications 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiuri, M.C.; Galluzzi, L.; Morselli, E.; Kepp, O.; Malik, S.A.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy regulation by p53. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2010, 22, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, O.; Quirós, P.M.; Auwerx, J. Mitochondria and epigenetics– Crosstalk in homeostasis and stress. Trends in Cell Biology 2017, 27, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilainen, O.; Sleiman, M.S. B.; Quiros, P.M.; Garcia, S.M. D. A.; Auwerx, J. The chromatin remodeling factor ISW-1 integrates organismal responses against nuclear and mitochondrial stress. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.K.; Bertoli, C. & de Bruin, R.A.M. Cell cycle control in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiroli, F.; Penengo, L. Histone Ubiquitination: An Integrative Signaling Platform in Genome Stability. Trends in Genetic 2021, 37, 566–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, B.A.; Gwon, G.; Mishra, A.; Peng, J.; Nakamura, H.; Zhang,K. ; Kim, H.J.; Taylor, J.P. Ubiquitination is essential for recovery of cellular activities following heat shock. Science 2021, 372, eabc3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams HH, Srinivasan B, Arkin AP. The evolution of genetic regulatory systems in bacteria. Nature Review Genetics 2004, 5, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mello, S.S.; Attardi, L.D. Deciphering p53 signaling in tumor suppression. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2018, 51, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michod, R.E. Cooperation and conflict in the evolution of individuality. I. Multilevel selection of the organism. The American Naturalist 1997, 149, 607–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michod, R.E. (2003). Cooperation and conflict mediation during the origin of multicellularity. In P. Hammerstein (Ed.), Genetic and cultural evolution of cooperation (pp. 291–307). MIT Press.

- Michod, R.E. On the transfer of fitness from the cell to the multicellular organism. Biology & Philosophy 2005, 20, 967–987. [Google Scholar]

- Michod, R.E. Evolution of individuality during the transition from unicellular to multicellular life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 2007, 104, 8613–8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michod, R.E. (2011). Evolutionary transition in individuality: Multicellularity and sex. In B. Calcott, & K. Sterelny (Eds.), The major transitions in evolution revisited (pp. 169–198). MIT Press.

- Michod, R.E.; Herron, M.D. Cooperation and conflict during evolutionary transitions in individuality. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2006, 19, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michod, R.E.; Nedelcu, A.M. On the reorganization of fitness during evolutionary transitions in individuality. Integrative & Comparative Biology 2003, 43, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Michod, R.E. ; (1998). Origin of sex for error repair: III. selfish sex. Theoretical Population Biology, 53, 60–74.

- Michod, R.E.; Viossat, Y.; Solari, C.A.; Hurand, M.; Nedelcu, A.M. Life-history evolution and the origin of multicellularity. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2006, 239, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhailov, K.V.; Konstantinova, A.V.; Nikitin, M.A.; Troshin, P.V.; Rusin, L.Y.; Lyubetsky, V.A. The origin of Metazoa: A transition from temporal to spatial cell differentiation. Bioessays 2009, 31, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, M.; Falcone, I.; Conciatori, F.; Matteoni, S.; Sacconi, A.; Luca, T.D.; et al. PTEN status is a crucial determinant of the functional outcome of combined MEK and mTOR inhibition in cancer. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 43013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milo, R.; Itzkovitz, S.; Kashtan, N.; Levitt, R.; Shen-Orr, S.; Ayzenshtat, I.; et al. Superfamilies of evolved and designed networks. Science 2004, 303, 1538–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milo, R.; Shen-Orr, S.; Itzkovitz, S.; Kashtan, N.; Chklovskii, D.; Alon, U. Network motifs: Simple building blocks of complex networks. Science 2002, 298, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, R.M.; Whitmarsh, A.J. Mitochondrial Proteins Moonlighting in the Nucleus. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2022, 40, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortzfeld, B.M.; Taubenheim, J.; Klimovich, A.V.; Fraune1, S.; Rosenstiel, P.; Bosch, T.C. G. Temperature and insulin signaling regulate body size in Hydra by the Wnt and TGF-beta pathways. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottis, A. Sébastien Herzig, & Auwerx, J. Mitocellular communication: Shaping health and disease. Science 2019, 366, 827–832. [Google Scholar]

- Nanjundiah, V. (2016). Cellular slime mold development as a paradigm for the transition from unicellular to multicellular life. In K. J. Niklas, & S. A. Newman (Eds.), Multicellularity: Origins and evolution (pp 105–130). MIT Press.

- Napoli, M.; Flores, E.R. The family that eats together stays together: New p53 family transcriptional targets in autophagy. Genes & Development 2013, 27, 971–974. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu, A.M. Sex as a response to oxidative stress: Stress genes co-opted for sex. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2005, 272, 1935–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu, A.M. Comparative genomics of phylogenetically diverse unicellular eukaryotes provide new insights into the genetic basis for the evolution of the programmed cell death machinery. Journal of Molecular Evolution 2009, 68, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu, A.M. The evolution of multicellularity and cancer: Views and paradigms. Biochemical Society Transactions 2020, 48, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu, A.M.; Michod, R.E. Sex as a response to oxidative stress: The effect of antioxidants on sexual induction in a facultatively sexual lineage. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2003, 270, S136–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelcu, A.M.; Michod, R.E. The evolutionary origin of an altruistic gene. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2006, 23, 1460–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelcu, A.M.; Michod, R.E. (2011). Molecular mechanisms of life history trade-offs and the evolution of multicellular complexity in Volvo calean green algae. In T. Flatt, & A. Heyland (Eds.), Mechanisms of life history evolution (pp. 271–283). Oxford University Press.

- Nedelcu, A.M.; Tan, C. Early diversification and complex evolutionary history of the p53 tumor suppressor gene family. Development Genes and Evolution 2007, 217, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelcu, A.M.; Driscoll, W.W.; Durand, P.M.; Herron, M.D.; Rashidi, A. On the paradigm of altruistic suicide in the unicellular world. Evolution 2011, 65, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelcu, A.M.; Marcu, O.; Michod, R.E. Sex as a response to oxidative stress: A twofold increase in cellular reactive oxygen species activates sex genes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2004, 271, 1591–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolay, B.N.; Danielian, P.S.; Kottakis, F.; Lapek, J.D.; Sanidas, I.; Miles, W.O.; et al. Proteomic analysis of pRb loss highlights a signature of decreased mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Genes & Development 2015, 29, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar]

- Niklas, K.J.; Newman, S.A. The origins of multicellular organisms. Evolution & Development 2013, 15, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Niklas, K.J.; Newman, S.A. (2016). Multicellularity: Origins and evolution, The MIT Press.

- Niklas, K.J.; Newman, S.A. The many roads to and from multicellularity. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 71, 3247–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunoura, T.; Takaki, Y.; Kakuta, J.; Nishi, S.; Takami, H. Insights into the evolution of archaea and eukaryotic protein modifier systems revealed by the genome of a novel archaeal group. Nucleic Acids Research 2011, 39, 3204–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, S. (2006). Evolution and the levels of selection.

- Ouyang, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, S.; Wang, F-T. ; Zhou, T-T.; Liu, B.; et al. Programmed cell death pathways in cancer: A review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Proliferation 2012, 45, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, N.J.; Pearson, B.J.; Levin, M.; Alvarado, A.S. Planarian PTEN homologs regulate stem cells and regeneration through TOR signaling. Disease Models and Mechanisms 2008, 1, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ǿvrebǿ, J.I.; Ma, Y.; Edgar, B.A. Cell growth and the cell cycle: new insights about persistent questions. BioEssays, 2022, 44, 2200150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panatta, E.; Zampieri, C.; Melino, G.; Amelio, I. Undertanding p53 tumour surressor network. Biology Direct 2021, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pankow, S.; Bamberger, C. The p53 tumor suppressor-like protein nvp63 mediates selective germ cell death in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Ahn, J-W. ; Kim, Y-K.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, W.T.; Pai, H-S. Retinoblastoma protein regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and endoreduplication in plants. The Plant Journal 2005, 42, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, R. Discovery of the PTEN tumor suppressor and its connection to the PI3K and AKT oncogenes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2020, 10, a036129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, B.J.; Alejandro, A.S. A planarian p53 homolog regulates proliferation and self-renewal in adult stem cell lineages. Development 2010, 137, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polager, S.; Ginsberg, D. P53 and E2F: partners in life and death. Nature Reviews Cancer 2009, 9, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, A.M.; Gribaldo, S. Eukaryotic origins: how and when was the mitochondrion acquired? Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2014, 6, a015990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.M.; et al. Deciphering functional roles and interplay betweenBeclin1and Beclin2in autophagosome formation and mitophagy. Science Signaling 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.D.; White, E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science 2010, 330, 1344–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raff, M.C. Social controls on cell survival and cell death. Nature 1992, 356, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, K.; Haslbeck M, Buchner J. The heat shock response: life on the verge of death. Molecular Cell 2010, 40, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, A.J.; Munoz-Gomez, S.A.; Kamikawa, R. The origin and diversification of mitochondria. Current Biology 2016, 27, R1177–R1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Rocher, N.; Pérez-Posada, A.; Leger, M.M.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. The origin of animals: An ancestral reconstruction of the unicellular-to-multicellular transition. Open Biology 2021, 11, 200359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Trillo, I. (2016). What are the genomes of premetazoan lineages telling us about the origin of Metazoa? In K. J. Niklas, & S. A. Newman (Eds.), Multicellularity: Origins and evolution (pp. 171–184). The MIT Press. Springer.

- Ruiz-Trillo, I.; Nedelcu, A.M. (2015). Evolutionary transitions to multicellular life: Principles and mechanisms.

- Rutkowski, R.; Hoffman, K.; Gartner, A. Phylogeny and Function of the Invertebrate p53 Superfamily. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2010, 2, a001131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatini, D.S. Twenty-five years of mTOR: Uncovering the link from nutrients to growth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 2017, 114, 11818–11825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivam, S.; DeCaprio, J.A. The DREAM complex: Master coordinator of cell cycle-dependent gene expression. Nature Reviews Cancer 2013, 13, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez-Rodriguez, J.; Kremling, A.; Gilles, E.D. Dissecting the puzzle of life: modularization of signal transduction networks. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2005, 29, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggere, R.M. S.; Lee, C.W. J.; Chan, I.C. W.; Durnford, D.G.; Nedelcu, A.M. A life-history trade-off gene with antagonistic pleiotropic effects on reproduction and survival in limiting environments. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences 2022, 289, 20212669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap, P. Evolution of developmental signaling in Dictyostelid social amoebas. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2016, 39, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schertel, C.; Conradt, B.C. elegans orthologs of components of the RB tumor suppressor complex have distinct pro-apoptotic functions. Development 2007, 134, 3691–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, M.; Ben-Shannan T., L.; Rolls, A. Neuronal regulation of immunity: why, how and where? Nature Reviews Immunology 2021, 21, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmoller, K.M.; Turner J., J.; Kõivomägi, M.; Skotheim, J.M. Dilution of the cell cycle inhibitor Whi5 controls budding-yeast cell size. Nature 2015, 526, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, D.T.; Haddock, S.H. D.; Bredeson, J.V.; Green, R.E.; Simakov, O.; Rokhsar, D.S. Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals. Nature 2023, 618, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A.; Degnan, B.M.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. The origin of Metazoa: A unicellular perspective. Nature Reviews Genetics volume 2017, 18, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, S.; Peterson, T.R.; Sabatini, D.M. Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Molecular Cell 2010, 40, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serfontein, J.; Nisbet, R.E. R.; Howe, C.J.; de Vries, P.J. Evolution of the TSC1/TSC2-TOR Signaling Pathway. Science Signaling 2010, 3, ra49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.M.; Codogno, P. Autophagy is a survival force via suppression of necrotic cell death. Experimental Cell Research 2012, 318, 1304–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Xia, Z.; Yang, H.; Hu, R. The ubiquitin codes in cellular stress response. Protein & Cell 2024, 15, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J.; McCormick, F. The RB and p53 pathways in cancer. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Norberg, E.; Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg, H. Mutant p53 as a regulator and target of autophagy. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 10, 607149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siau, J.W.; Coffill, C.R.; Zhang, W.V.; Tan, Y.S.; Hundt, J.; Lane, D.; et al. Functional characterization of p53 pathway components in the ancient metazoan. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 33972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, Herbert A. 1962[1996]. The Architecture of Complexity. In H. A. Simon (Ed.), The sciences of the artificial (pp. 183–216). MIT Press.

- Sinha, S.; Levine, N. The autophagy effector Beclin-1: a novel BH3-only protein. Oncogene 2009, 27, S137–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.M.; Szathmáry, E. The origin of chromosomes I. Selection for linkage. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1993, 164, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogabe, S.; Hatleberg, W.L.; Kocot, K.M.; Say, T.E.; Stoupin, D.; Roper, K.E.; et al. Pluripotency and the origin of animal multicellularity. Nature 2019, 570, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowpati, D.T.; Ramamoorthy, S.; Mishra, R.K. Expansion of the polycomb system and evolution of complexity. Mechanisms of Development 2015, 138, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, J.B.; Haigs, M.C. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nature Cell Biology 2018, 20, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stielow, B.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Y.; Simon, C.; Pogoda, H.M.; Jiang, J.; et al. The SAM domain-containing protein 1 (SAMD1) acts as a repressive chromatin regulator at unmethylated CpG islands. Science advances 2021, 7, eabf2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, H.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. Development of ichthyosporeans sheds light on the origin of metazoan multicellularity. Developmental Biology 2013, 377, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, H.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. (2015). Filastereans and Ichthyosporeans: Models to Understand the Origin of Metazoan Multicellularity. In I. Ruiz-Trillo, & A. M. Nedelcu. (Eds.), Evolutionary transition to multicellular life: Principles and mechanisms (pp. 117-128). Springer.

- Suh, E.K.; Yang, A.; Kettenbach, A.; Bamberger, C.; Michaelis, A.H.; Zhu, Z.; et al. p63 protects the female germ line during meiotic arrest. Nature 2006, 444, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.X.; et al. SUMO protease SENP1 deSUMOylates and stabilizes c-Myc. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 2018; 115, 10983–10988. [Google Scholar]

- Szathmáry, E. Toward major evolutionary transitions theory 2.0. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 2015, 112, 10104–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szathmáry, E.; Smith, J.M. The major evolutionary transitions. Nature 2003, 374, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szathmáry, E.; Wolpert, L. (2003). The transition from single cells to multicellularity. In P. Hammerstein (Ed.), Genetic and Cultural Evolution of Cooperation (pp. 271–290). MIT Press.

- Takemura, M. Evolutionary history of the retinoblastoma gene from archaea to eukarya. Biosystems 2005, 82, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.; Fujimoto, M.; Takii, R.; Takaki, E.; Hayashida, N.; Nakai, A. Mitochondrial SSBP1 protects cells from proteotoxic stresses by potentiating stress-induced HSF1 transcriptional activity. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Kang, R. (2022). Cell death: Machinery and regulation. In (Eds.), Mechanisms of Cell Death and Opportunities for Therapeutic Development (pp. 47–64). Elsevier.

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Berghe, T.V.; Vandenabeele, P. & Kroemer, G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Research 2019, 29, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tatebe, H.; Shiozaki, K. Evolutionary conservation of the components in the tor signaling pathways. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.E.; Zhang, Y.; Stefely, J.A.; Veiga, S.R.; Thomas, G.; Kozma, S.C.; et al. Mitochondrial complex I activity is required for maximal autophagy. Cell Reports 2018, 24, 2404–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomer, J. TOR complex 2 is a master regulator of plasma membrane homeostasis. Biochemical Journal 2022, 479, 1917–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Garcia, G.; Bian, Q.; Steffen, K.; Dillin, A. Mitochondrial stress induces chromatin reorganization to promote longevity and UPRmt. Cell 2016, 165, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos, A.S.; Pearson, R.B.; Papenfuss, A.T.; Goode, D.L. Somatic mutations in early metazoan genes disrupt regulatory links between unicellular and multicellular genes in cancer. eLife 2019, 8, e40947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigos, A.S.; Pearson, R.B.; Papenfuss, A.T.; Goode, D.L. Altered interactions between unicellular and multicellular genes drive hallmarks of transformation in a diverse range of solid tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114, 6406–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigos, A.S.; Pearson, R.B.; Papenfuss, A.T.; Goode, D.L. How the evolution of multicellularity set the stage for cancer. British Journal of Cancer 2018, 118, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Deursen, J.M. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 2014, 509, 439–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, R.M.; Kupai, A.; Rothbart, S.B. Chromatin regulation through ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like histone modifications. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2021, 46, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaseva, A.V.; Marchenko, N.D.; Ji, K.; Tsirka, S.E.; Holzmann, S.; Moll, U.M. p53 opens the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to trigger necrosis. Cell 2012, 149, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga-Fernades, H.; Pachnis, V. Neuroimmune regulation during intestinal development and homeostasis. Nature Immunology 2017, 18, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venniyoor, A. PTEN: A thrifty gene that causes disease in times of plenty? Frontiers in Nutrition 2020, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, R. Multicellular individuality: The case of bacteria. Biological Theory 2019, 14, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertegaal, A.C. O. Signalling mechanisms and cellular functions of SUMO. Nature Reviews, Cell and Molecular Biology 2022, 23, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizioli, M.G.; Liu, T.; Miller, K.N.; Robertson, N.A.; Gilroy, K.; Lagnado, A.B.; et al. Mitochondria-to-nucleus retrograde signaling drives formation of cytoplasmic chromatin and inflammation in senescence. Genes & Development 2020, 34, 428–445. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G.P.; Erkenbrack, E.M.; Love, A.C. Stress-induced evolutionary innovation: A mechanism for the origin of cell types. BioEssays 2019, 41, 1800188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walston, H.; Iness, A.N.; Litovchick, L. DREAM On: Cell Cycle Control in Development and Disease. Annual Review of Genetics 2021, 55, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y. Brain nuclear receptors and cardiovascular Function. Cell & Bioscience 2023, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, E.; Thoppli, H.; Riabowol, K. Senescence and Apoptosis: Architects of Mammalian Development. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 8, 620089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, I.R.; Irwin, M.S. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifications of the p53 family. Neoplasia 2006, 8, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, Irving L. Stem cells are units of natural selection for tissue formation, for germline development, and in cancer development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2015, 112, 8922–8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, N.V.; Kocot, K.M.; Moroz, T.P.; Mukherjee, K.; Williams, P.; Paulay, G.; et al. Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2017, 1, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar]

- White, E. Autophagy and p53. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2016, 6, a026120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.; Lattime, E.C.; Guo, J.Y. (2021). Autophagy Regulates Stress Responses, Metabolism, and Anticancer Immunity. Trends in Cancer 2021, 7, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, L.; Szathmáry, E. Evolution and the egg. Nature 2002, 420, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodland, H.R. The Birth of Animal Development: Multicellularity and the Germline. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 2016, 117, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; DeGregori, J.; Shohet, R.; Leone, G.; Stillman, B.; Nevins, J.R.; Williams, R.S. Cdc6 is regulated by E2F and is essential for DNA replication in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 1998, 95, 3603–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Shen, W.H. PTEN: A new guardian of the genome. Oncogene 2008, 27, 5443–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonekawa, T.; Thorburn. A. Autophagy and cell death. Essays in Biochemistry 2013, 55, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, L. PUMA, a potent killer with or without p53. Oncogene 2009, 27, S71–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachar, I.; Szathmáry, E. Breath-giving cooperation: Critical review of origin of mitochondria hypotheses. Biology Direct 2017, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatulovskiy, E.; Zhang, S.; Berenson, D.F.; Topacio, B.R.; Skotheim, J.M. Cell growth dilutes the cell cycle inhibitor Rb to trigger cell division. Science 2020, 369, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Rayburn, E.R.; Agrawal, S.; Zhang, R. Stabilization of E2F1 protein by MDM2 through the E2F1 ubiquitination pathway. Oncogene 2005, 24, 7238–7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hama, Y.; Mizushima, N. The evolution of autophagy proteins-diversification in eukaryotes and potential ancestors in prokaryotes. Journal of Cell Science 2021, 134, jcs233742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Bramsiepe, J.; Van Durme, M.; Komaki, S.; Prusicki, M.A.; Maruyama, D.; et al. Retinoblastoma related1 mediates germline entry in arabidopsis. Science 2017, 356, eaaf6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; Karin, M. Autophagy, inflammation, and immunity: A Troika governing cancer and its treatment. Cell 2016, 166, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Tian, Y. NuRD mediates mitochondrial stress-induced longevity via chromatin remodeling in response to acetyl-CoA level. Science Advances 2020, 6, eabb2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Although pseudo- or quasi- multicellularity exists in bacteria and Archaea (e.g., myxobacteria, cyanobacteria), genuine multicellularity, simple and then complex, exists only in eukaryotes (cf. Ventura 2019). |

| 2 | For a complete picture, we also include “(extra-body) exchange”, denoting the relationship between an organism and its environment. |

| 3 | RB-E2F is perhaps more useful for aerobic than anaerobic metabolism, and (most) metazoans are aerobic. This also suggests that RB-E2F is indispensable for genuinely multicellularity in metazoans (Attardi & Sage 2013). |

| 4 | In this sense, sex itself should not be considered to be a major transition (Herron 2021; see also Michod 2011, 186-9). More appropriately, sex laid a key foundation for the emergence of more complex individuality in multicellular organisms, as an unintended consequence. |

| 5 | Regulated cell death is perhaps a more fitting term than the more widely known programmed cell death (PCD). It is now commonly accepted that ferroptosis is not a distinct form of PANoptosis. For instance, ferroptosis is also connected with mitochondria and the p53 pathway. |

| 6 | Thus, components of PCD pathways in unicellular eukaryotes may function primarily as part of the mitochondria regulating or protecting machinery. |

| 7 | This fact is consistent with the more recent finding that ctenophores (comb jelly fish), rather than poriferas are the more likely sister group to all other animals (Schultz et al. 2023). See also Whelan et al. 2017. |

| 8 | The level of “intra-body but extra-cellular communication” is highlighted to denote the one that distinguishes genuine multicellular organisms such as metazoans from unicellular organisms. |

| 9 | In mammalians, Beclin-2 (BECN2), a homologue of Beclin-1 (and ATG-6), plays similar but non-identical functions in key pathways (He et al. 2013; Galluzzi & Kroemer 2013; Quiles et al. 2023). |

| Type | Sub-category | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-talk (intracellular) | Direct: via: 1) shared components and links, and 2) regulation of the expression of downstream genes. |

|

| Indirect: via coordination hubs. | RB-E2F, PTEN, TOR | |

| Intra-cellular (and intra-body) communication | Regular and irregular: between different cellular apparatuses and organelles | Between the nucleus, cytoplasm, and the mitochondria, vis targeting and regulation of gene expression. Intracellular stress signals. |

| Extra-cellular (and extra-body) exchange2 | Regular and irregular: between the organism and the external environment | Food and waste, nutritional changes, extra-body stresses, damages, and invasions. |

| Type | Sub-category | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-talk (intra-cellular) | Direct: via 1) gene expression, 2) via shared components and links | RB-E2F and p53-MDM2; apoptosis and autophagy |

| Indirect: via coordination hub. | RB-E2F, PTEN, TOR, p53-MDM2 | |

| Intra-body and intra-cellular communication | Regular and irregular: between different cellular apparatuses and organelles | Between the nucleus, cytoplasm, and the mitochondria, vis targeting and regulation of gene expression. Intracellular stress signals. |

| Intra-body but extra-cellular communication8 | Regular and irregular: between different cell types, tissues, and organs. | Hormone (e.g., insulin) and other extracellular ligands (e.g., lipids). Other intra-body stresses as signals |

| Extra-body (and extra-cellular) exchange | Regular and irregular: between the organism and the external environment | Food and waste, seasonal change, nocturnal cycles, and other extra-body inputs and outputs. Extra-body stresses, toxins, damages, and invasions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).