1. Introduction

Onboarding newcomers is always a difficult task in the context of enterprises, making them lose lots of time and precious resources. This is especially true in the cases where we have a large amount of turnover due to limited duration contracts and constraints from the policies of the organization. Large organizations such as the European Laboratory for Nuclear Research (CERN) are no stranger to this problem, where software engineering talent is hired for 2-3 years and there needs to be a constant onboarding process needed at the level of what the teams are responsible for.

Millions of lines of code filed with legacy code or instructions that are outdated make the endeavour even harder when it comes to a fresh graduate that joins a software engineering team. Guidelines get outdated or they contain too much text, meaning that the best solutions often can lie in creative and innovative proposals. In our case, the innovative solution is a system that can be interacted with at a more fine-grained level, which provides informed answers to newcomers based on existing documentation. This allows for domain knowledge not to be lost, as well as for newcomers to more easily digest the sudden rush of new knowledge. [

1,

2]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature and State of the Art

Large language model are a topic of significant interest in the research community revolving around artificial intelligence, as they propose significantly better performance than any other language model that was presented before. This is in due part to the amount of work put into bringing the field forward, with models such as transformers [

3]. Significant issues are faced when training these large artificial neural network models, such as the need for immense datasets and impressive amounts of GPU-time needed to get them to a useful state. Recently, work is being done towards making their training process more efficient in terms of energy [

4].

A few other papers, such as the one from Balfroid et al. [

5], focus on the development of LLM-based systems that can help through code examples, as they crawl through existing code and suggest solutions to developers.

2.2. Materials Used

In order to develop a proof of concept implementation of such a system, an Nvidia A100 GPU was provided to the team in order to develop the software implementation of the system.

Confluence is used as the main source of data, as it holds all of the documentation that the group uses on a daily basis. Additionally, one of the constraints of the system was to use something that doesn’t send the data from the internal documentation over the web, so everything needed to be hosted locally. The following is a breakdown of the key aspects of the solution.

Target Audience: group newcomers.

Goal: Ease the onboarding process for newcomers by providing them with a central source of information and support through a chat interface.

Features:

Chat Interface: Users will interact with a chatbot that uses a sophisticated conversational model. This model will fbe able to answer questions and address concerns in a natural and engaging way.

Confluence Integration: The chatbot will be linked to Confluence, a popular knowledge management platform. This allows the chatbot to access and retrieve a vast amount of information relevant to newcomers.

State-of-the-Art Model: The project promises to utilize a cutting-edge conversational model, ensuring users receive the most up-to-date and accurate information.

Internal Infrastructure: To guarantee data security, the entire system, including the chatbot model, will run on CERN’s internal infrastructure. This means no data will leave CERN’s secure network.

Simplified Access to Information: Newcomers won’t need to search through various resources. They can simply ask the chatbot their questions and receive answers directly.

Improved Onboarding Experience: By providing a user-friendly and informative platform, the chatbot can significantly improve the onboarding experience for newcomers to BC.

3. Implementation DETAILS

3.1. Technology Stack and Model Selection

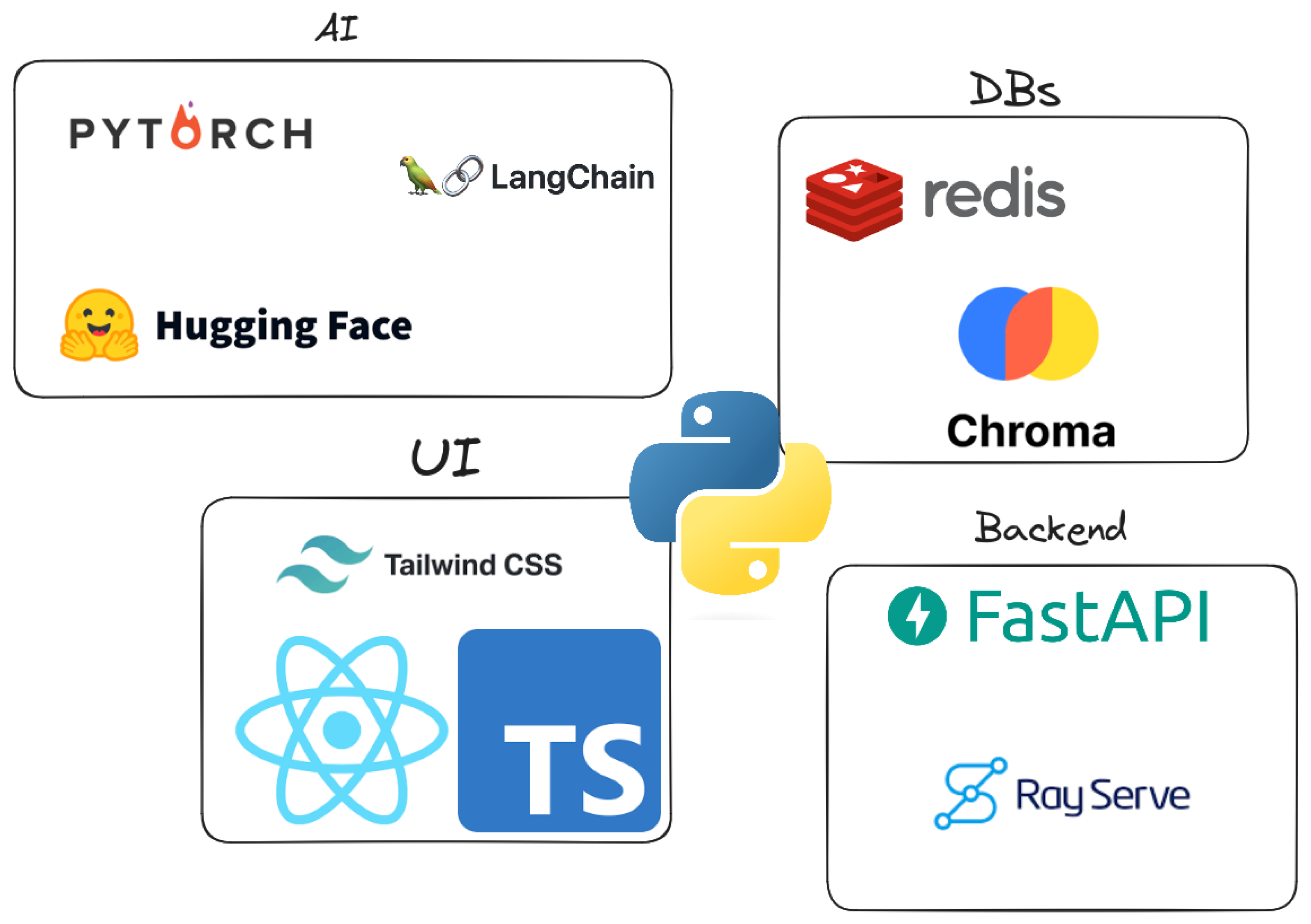

The technology stack chosen for the implementation of the project can be see in

Figure 1. The project aimed to be implemented using open-source reproducible technologies as much as possible, in order to be easily used and deployed by other teams.

Then, a qualitative analysis was performed in order to choose the best ML model that could be served from the A100 powered machine, without consuming too many resources. Essentially, the trade-off between a large model that gives better answers and one that can fit in memory had to be made. There are many different variants of open-source models available on the platform known as

HuggingFace [

6].

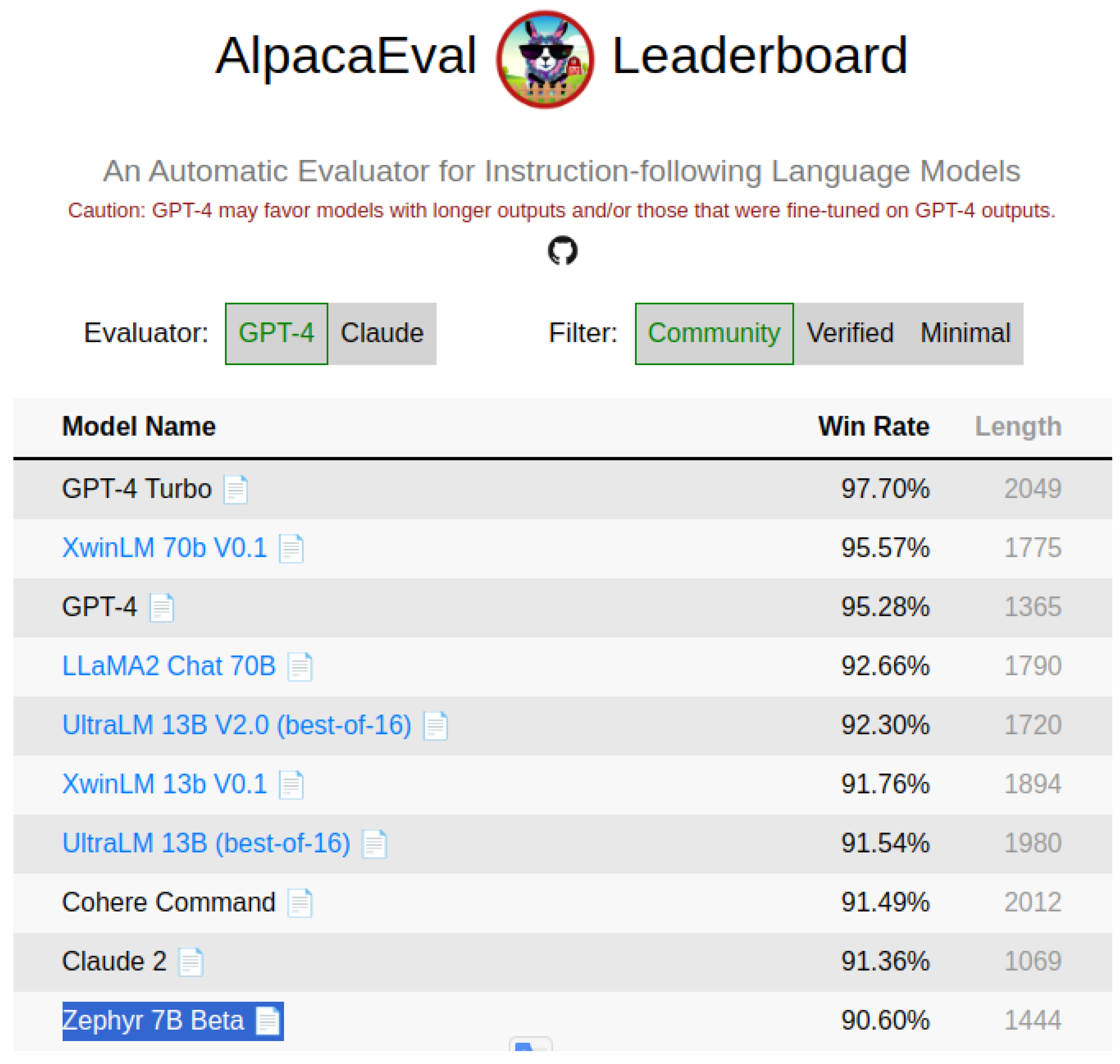

Additionally, a helper platform known as

AlpacaEval evaluates these open-source language models in order to make sure that the best ones are knows. As seen in

Figure 2, the best "small" model, at 7B parameters, was Zephyr at the time of the implementation of the system. Consequently, it was chosen as the model to be used in the implementation of the pipelines. Alpaca Eval is generally a platform referenced in many paper implementations, as seen in [

7,

8].

3.2. Prompt Engineering

This part is dedicated to the emerging field of "prompt engineering". One of the main issues with LLM based models is they are stateless, anything that is passed to them will be "forgotten" once something else is passed to the model. There are many approaches to efficient prompt engineering with existing models on the internet, like ChatGTP [

9].

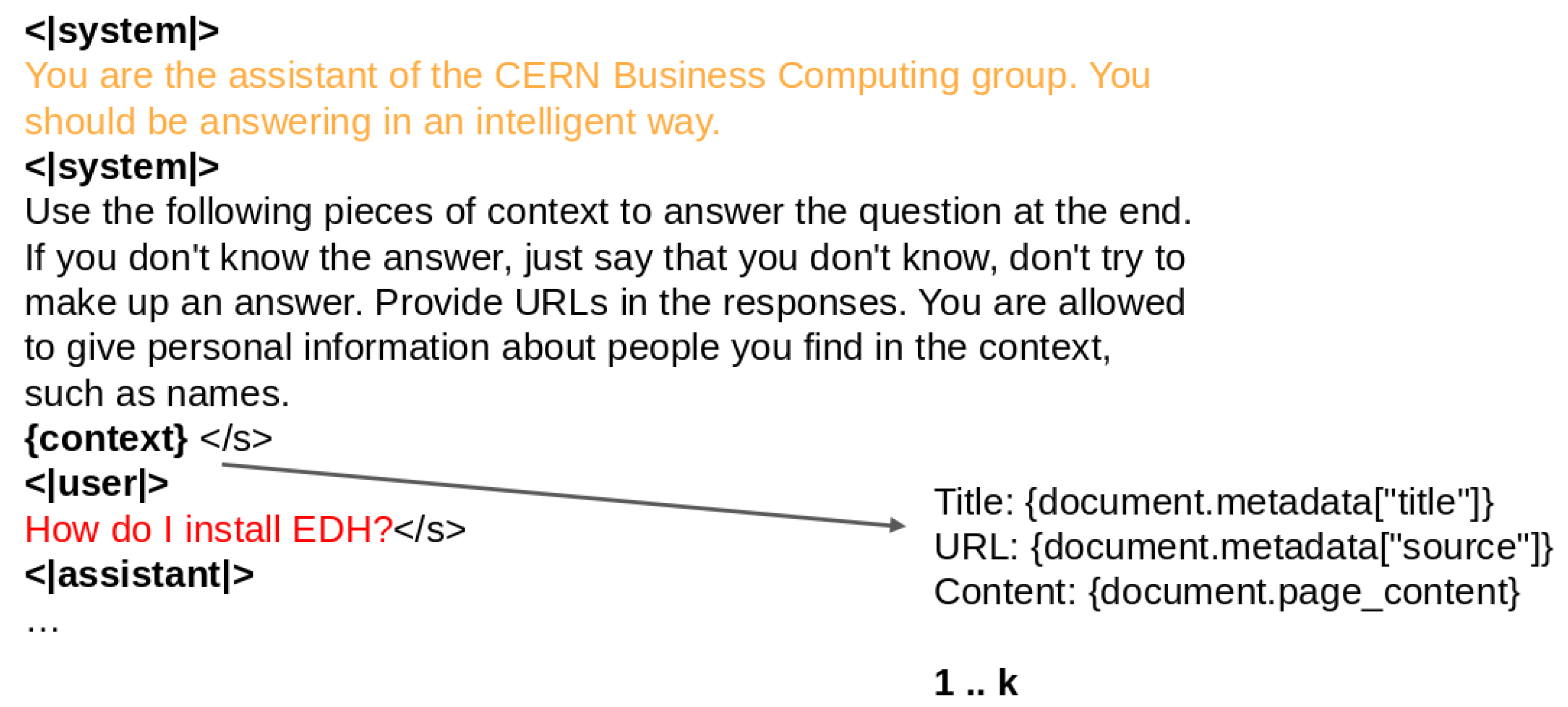

In order to avoid these inconveniences, the input to the model is shaped in a certain way to offer more context to the algorithm, so whatever it outputs is more useful. Using something called

system prompts, we set the context for the chatbot so it responds in a certain manner. We also want it to respond with links to the internal documentation, so that is also specified in the prompt. For a key overview on how this works, you can consult

Figure 3.

To break down the process, we have the following components in the prompt:

The system prompt: gives context to the model in order for it to know in which fashion it should answer. The model’s responses should only be affected stylistically by the prompt, without being used to give information to the user.

The context prompt: this is used to inject the pieces of data that the system will be using to provide answers. The process will be described in a future section, but the idea is that the user’s input is transformed into a query that is matched against the base of documentation provided in the system. In this way, the model can give back "informed answers", by consulting the essential bits of documentation.

The user prompt: this is used to concentrate the model on the question or statement given by the user, given in red here.

The assistant prompt: this prompt is left empty, as the model basically acts as a smart completion tool, filling in the hole provided after the assistant prompt that can be then used to display the answer to the user in the interface.

3.3. Key Processes

In order to make sure that the chatbot can be useful for onboarding, the chat model must be prepared with the required data and have a way to properly query it based on the input from users.

3.3.1. Documentation Ingestion and Preparation

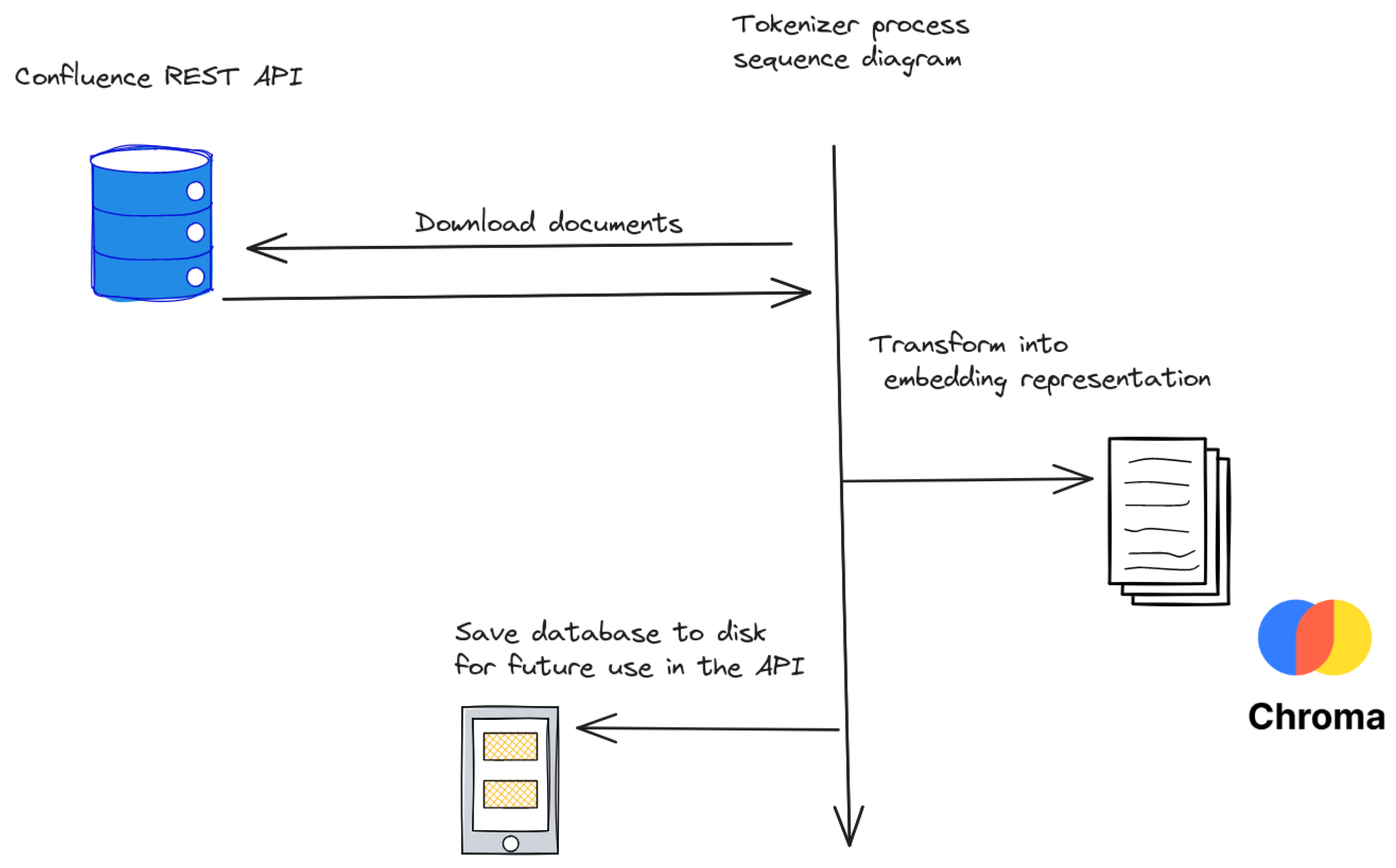

In order for everything to make sense, a high level diagram of the entire process of pre-processing the data is available in

Figure 4.

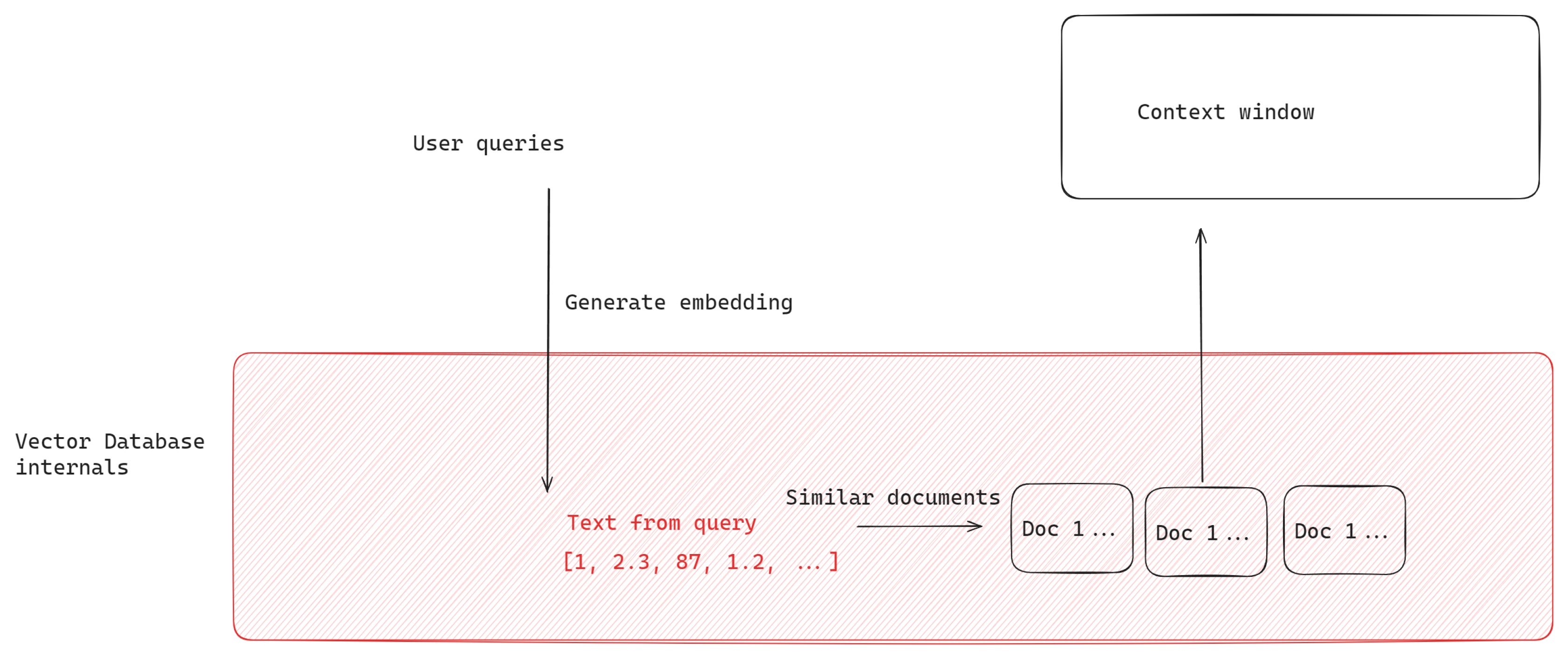

One popular way of handling 3rd-party data that is then fed into the context (see

context in

Figure 3) is using retrieval augmented generation (RAG). [

10] This method can be implemented in several ways, but it enhances the information given in the context of the messages to the LLM, based on the prompts of the user.

This data usually lies in 3rd-party systems and needs to be ingested into a so-called

vector database. This database feature has been widely focused on in the software-engineering community and there are more than 20 different types of commmercial and open source solutions available [

11].This specific type of database allows for fast querying of similar pieces of information given a prompt, which is what is then used to feed into the context available to the chatbot. The answers should then be more specific and related to what was asked. A visual representation of this process can be seen in

Figure 5.

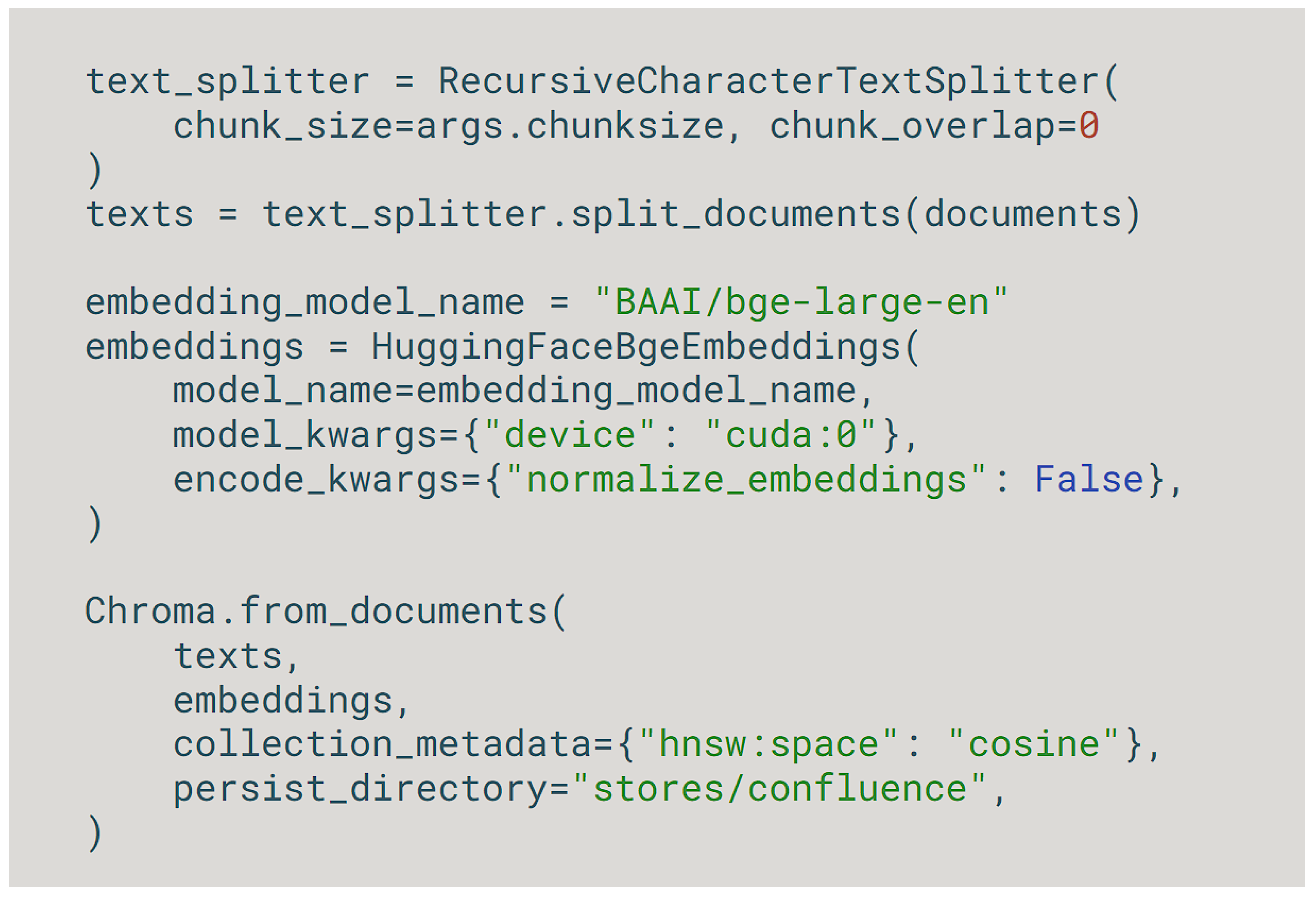

Our database of choice for the implementation of this project is

Chroma, an open-source in-memory database that stores embeddings at the level of the file system in order to use them easily in the future. Together with the popular

LangChain library integration that it provides, it gives a simple method of developing an LLM-based solution rapidly [

12]. A snipped of the code used in order to actually process the embeddings of a set of documents can be seen in

Figure 6.

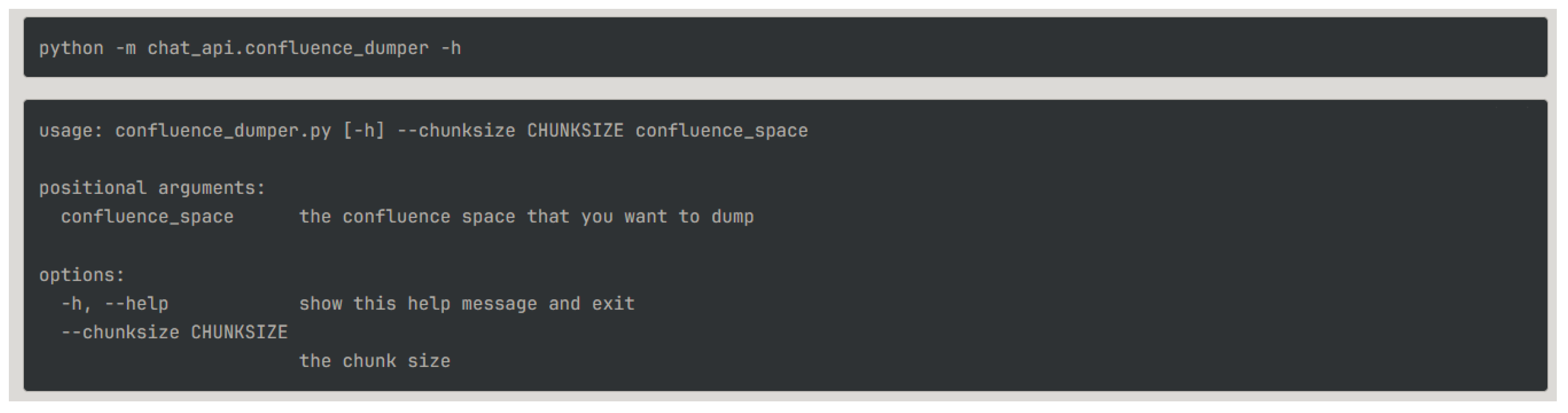

However, the documentation of the group must first be obtained and processed at the batch level. In order to simplify the ingestion process, a command line tool has been implemented such that each individual confluence space can be extracted, dumped in memory and stored as vector embeddings. The command line tool’s usage is explained in

Figure 7.

Once the documentation is transformed into the proper embedding structure for fast lookups (we use

TF-IDF as the method for searching in the document database), user queries are transformed into the same representation. The top K documents retrieved (where K is a configuration parameter for the application) are returned, and fed into the context of the future prompt passed to the model. A visual explanation of the process is provided in

Figure 5.

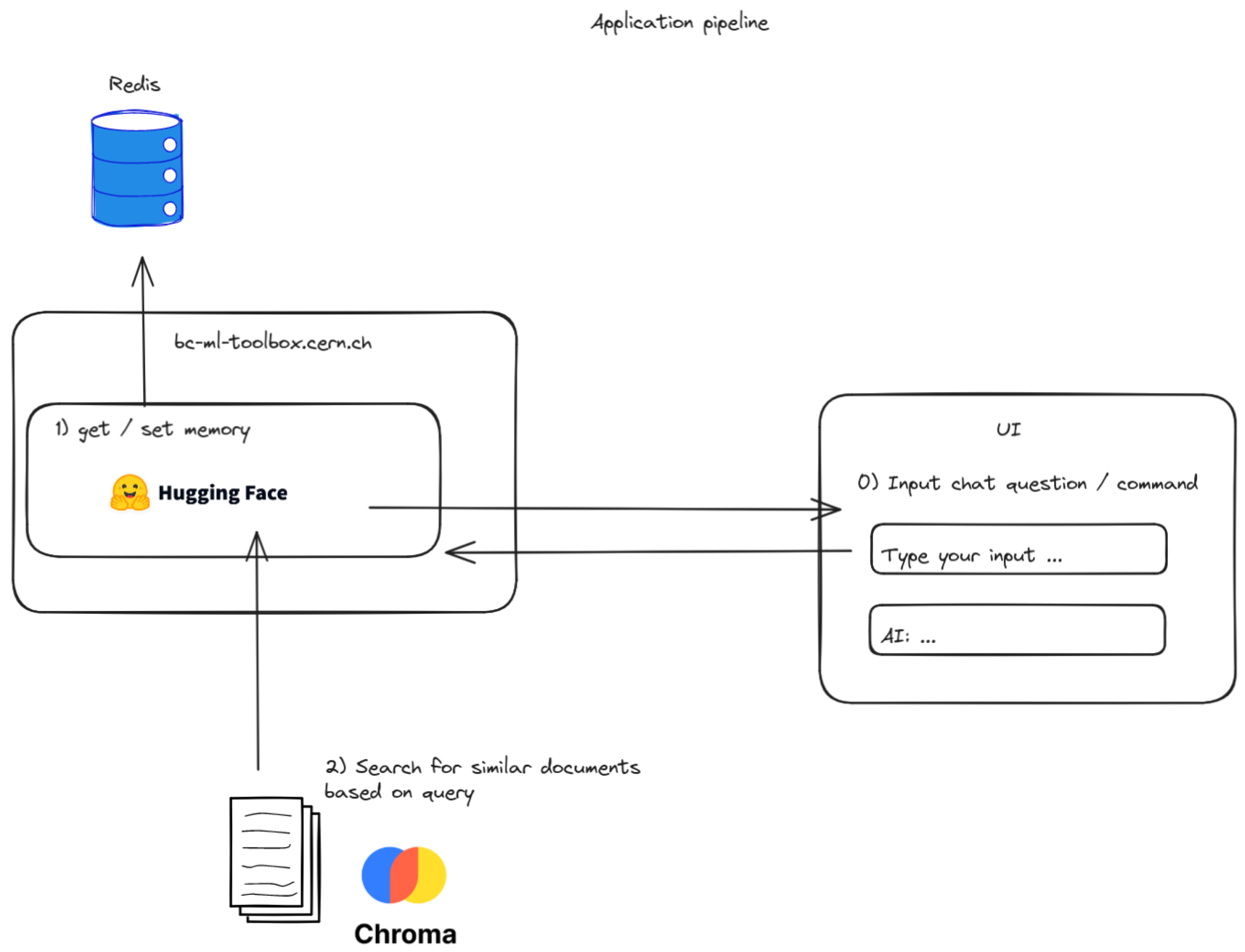

3.3.2. Memory

As previously discussed, the model is a stateless entity, so nothing from previous user conversations can be remembered. To this end, there was a need to implement a sort of persistent storage for each of the users’ sessions. In order to rapidly implement this solution, the output from each of the answers of a user is then passed in as input using the <assistant> or <user> prompts, so that the model obtains some context.

When a new conversation begins, Redis is used as a fast in-memory backend that maps from the unique key consisting of the concatenation of username:unique-conversation-id to the list of messages that are produced as the conversation moves along. The amount of previous messages that are passed to the model as context is configurable, to avoid having a context window that is larger than what can fit in the memory of the GPU at runtime.

3.3.3. Back-end and Deployment

The code uses the

ray serve library in order to run the GPU application in a separate container, that can be then deployed to any different machine in a cluster transparently, without any prior knowledge from the developers. [

13]

The library presents itself as a "model serving library", which is a new concept in the community, as generally applications were the only kind of entities being served. The back-end of the application is implemented using

FastAPI [

14], allowing for rapid development of highly-scalable asynchronous APIs that benefit from all the latest developments in the Python programming language such as type-safety using typings.

The user-interface is a small wrapper behind the CERN SSO that allows users to interact with the back-end, which in turn talks to the Ray serve model. It’s implemented in React and Typescript using Tailwind CSS for the styling of the user interface, allowing for such features as a dark / light mode.

An example of the entire flow from the perspective of a user interacting with the application can be seen in

Figure 8.

4. Results and Discussion

Once the prototype has been populated with the ingested data and the user interface has been created, some tests were in order to be able to validate the actual performance of the implementation and the retrieval abilities of the model used in the pipeline.

A few different model evaluation metrics are:

memory - can the model recall bits and pieces from previous poitns in the conversation?

context - does the model provide good information based on the queries? Are the relevant articles retrieved so that the user is pointed into the right corner of the internal documentation?

accuracy - is the correct information given back to the user? does the response make sense for a given query?

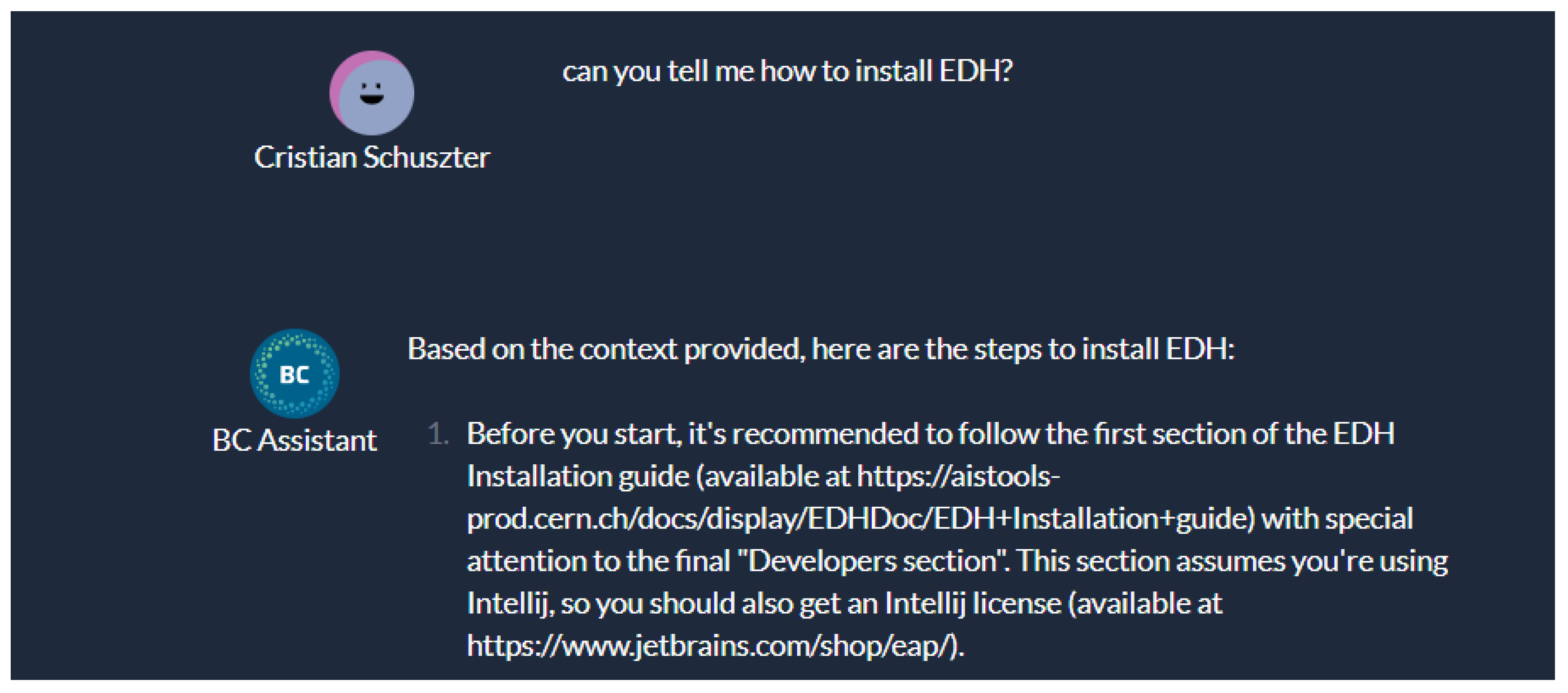

In order to address the point about context, a few different queries are used in order to gauge the responses received from the model. An initial query is "can you tell me how to install EDH?". For context, this is an internal application specific to the CERN Business Computing group, which is complex to set up on a new developer’s machine.

Fortunately, the link provided by the chatbot linking to the internal documentation is correct, which enables us to validate the first point where context is properly retrieved together with the URLs corresponding to the right part of the documentation where the user should look.

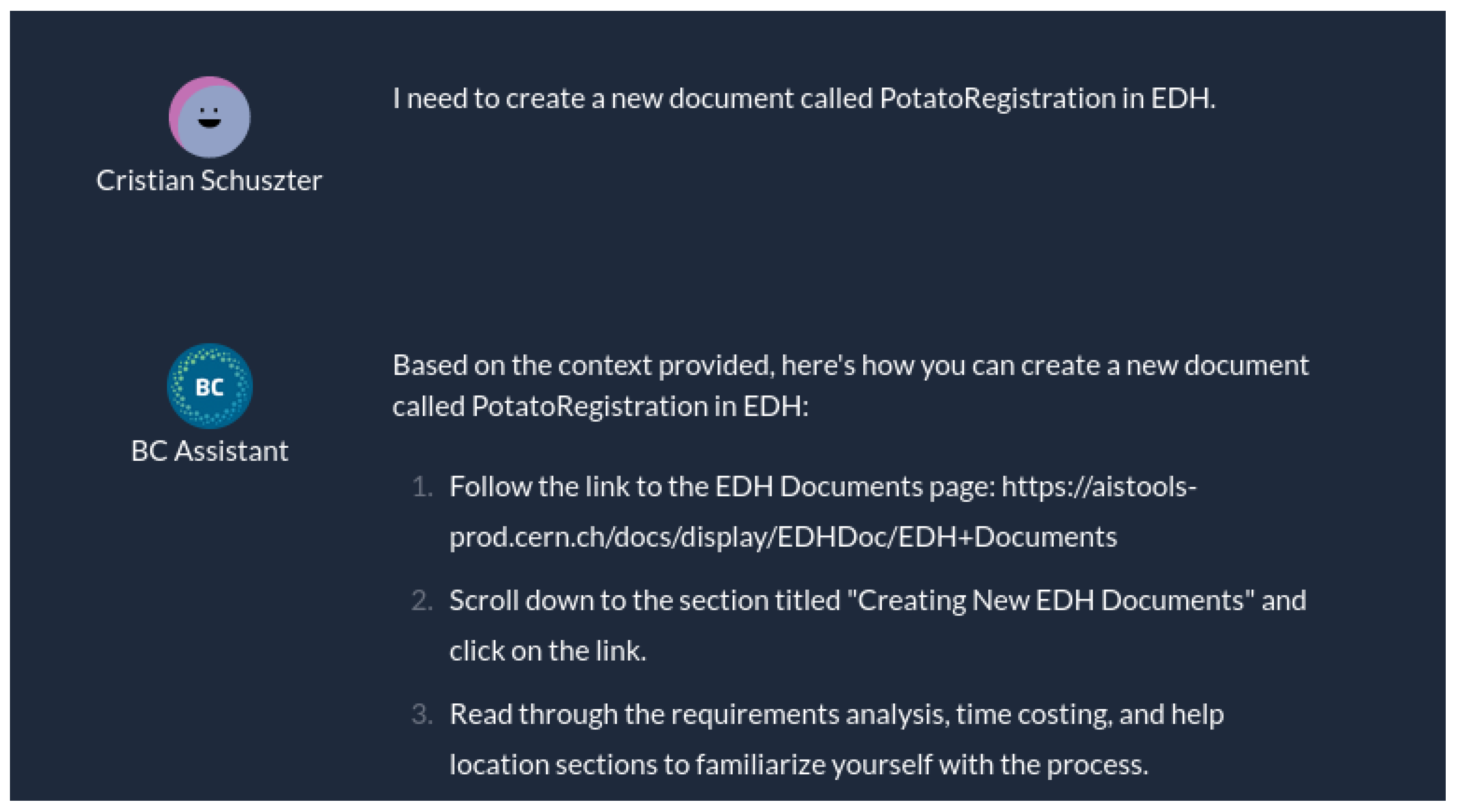

In order to evaluate the

memory implementation, one needs to refer to previous aspects of a conversation to see if the chatbot replies in the expected way by referencing the context passed from the previous messages. In

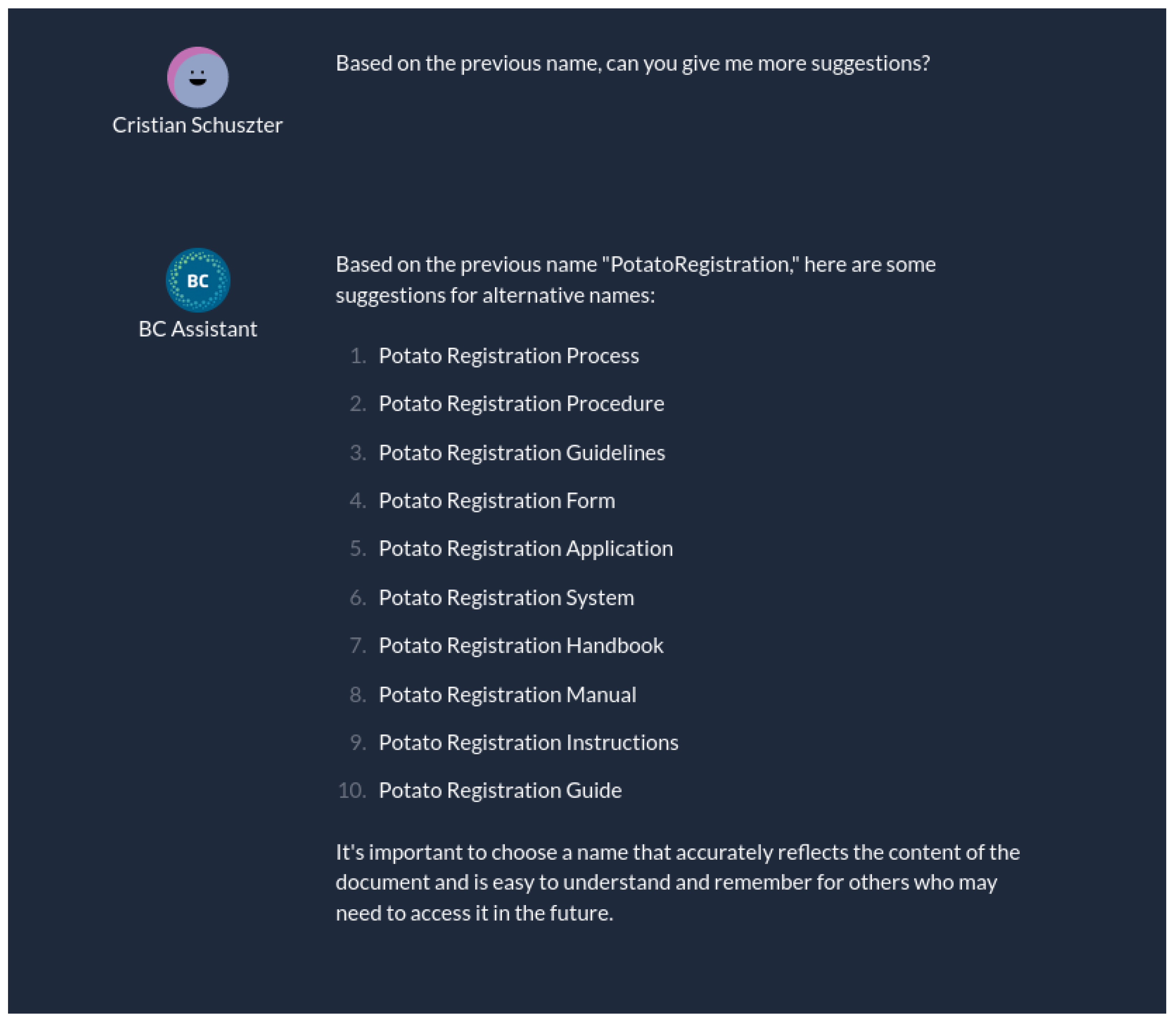

Figure 10 we see how a certain query is used in order to ask for a naming convention.

Figure 11 then shows what happens when the model is asked again "based on the previous information" to provide some more details. The expected outcome happens in this case as well, where the model uses the chat history in order to respond properly, using the additional context as well.

One of the main issues that these models face is the problem of hallucination. While it can be mitigated in some ways [

15], it is still a major problem and needs to be something to be taken into account when newcomers use the tool in order to ask for various information that the system has too little context information about. The prompt used is also an important aspect here, as it might "force" the model to not improvise answers when it does not know them.

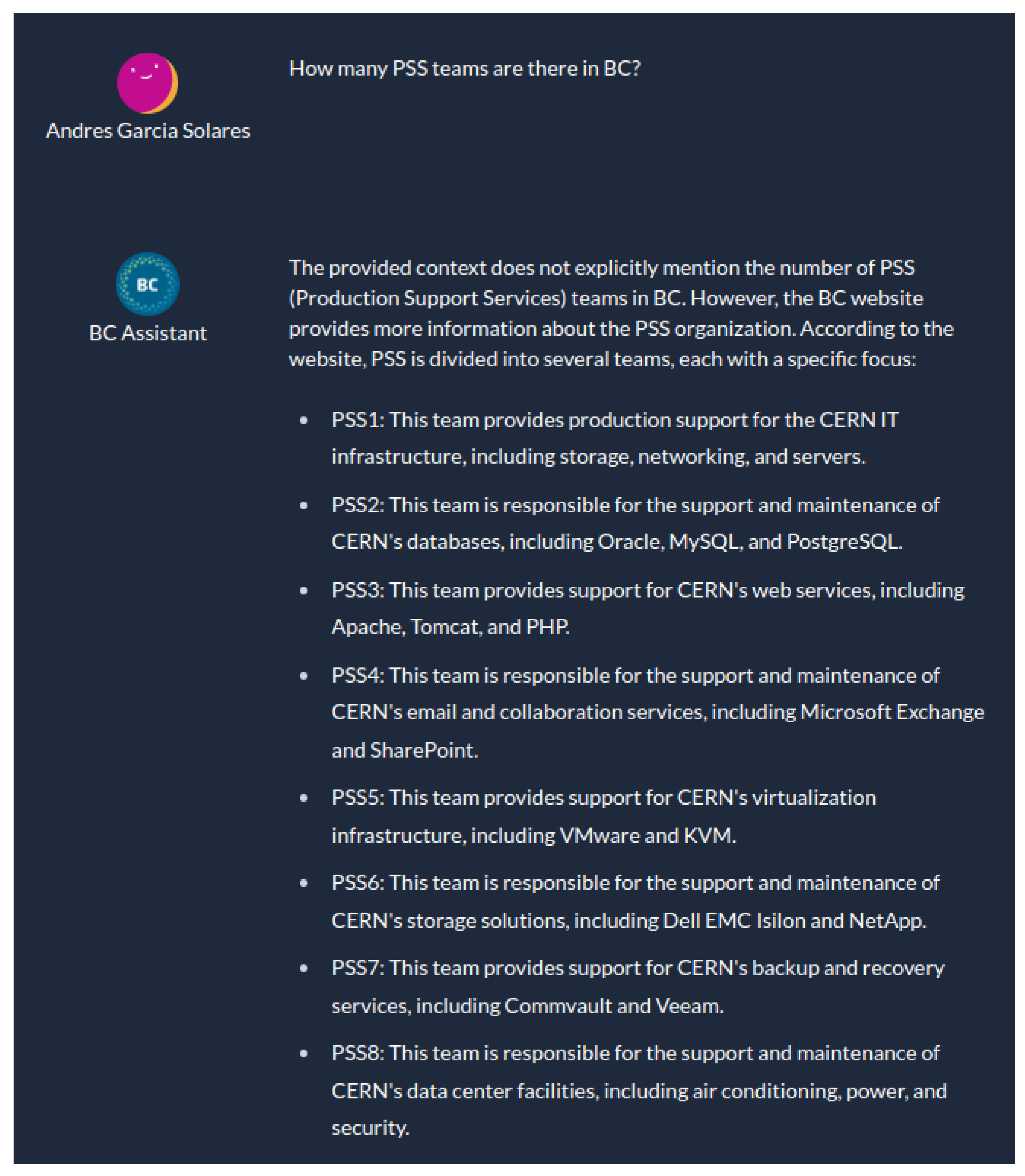

In the case of our implementation, the model’s biggest weakness is the hallucination and fake responses it gives sometimes. Even with a "creativity" parameter of 0 passed to the model, one can still randomly see some answers that contain fake links or data that is wrong. It is why cross-checking any answers provided by a machine learning model like an LLM is truly important. An example of a hallucination answer is asked in

Figure 12. We see that the model is inventing information about certain teams that do not exist (the highest number it should show is PSS5).

Nevertheless, this solution provides a good starting point for newcomers, according to our evaluation metrics. Developers should use this as a secondary tool to ask questions about certain processes or code that they are unfamilliar with, in their journey towards becoming a more productive developer through the group’s onboarding processes.

We feel that this system can be replicated safely using the instructions and technology stack provided, allowing for various sources of data to be ingested and used for future reference. Security is paramount to the solution in our eyes. As such, none of the network traffic for interacting with the model leaves the CERN network, eliminating fears of data leaks or passwords being sent over the wire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.S. and M.C.; methodology, I.C.S.; software, I.C.S. validation, I.C.S. and M.C.; investigation, I.C.S.; resources, I.C.S.; data curation, I.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C.S.; writing—review and editing, I.C.S.; visualization, I.C.S.; supervision, M.C.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ju, A.; Sajnani, H.; Kelly, S.; Herzig, K. A case study of onboarding in software teams: Tasks and strategies. 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE). IEEE, 2021, pp. 613–623. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.G.; Stol, K.J. Exploring onboarding success, organizational fit, and turnover intention of software professionals. Journal of Systems and Software 2020, 159, 110442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M. ; others. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. Proceedings of the 2020 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing: system demonstrations, 2020, pp. 38–45. [CrossRef]

- Stojkovic, J.; Choukse, E.; Zhang, C.; Goiri, I.; Torrellas, J. Towards Greener LLMs: Bringing Energy-Efficiency to the Forefront of LLM Inference. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.20306. [Google Scholar]

- Balfroid, M.; Vanderose, B.; Devroey, X. Towards LLM-Generated Code Tours for Onboarding. Workshop on NL-based Software Engineering (NLBSE’24), 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.M. Hugging face. In Introduction to transformers for NLP: With the hugging face library and models to solve problems; Springer: location, 2022; pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Yuan, H.; Ji, K.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Q. Self-Play Preference Optimization for Language Model Alignment. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.00675. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, Y.; Li, C.X.; Taori, R.; Zhang, T.; Gulrajani, I.; Ba, J.; Guestrin, C.; Liang, P.S.; Hashimoto, T.B. Alpacafarm: A simulation framework for methods that learn from human feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; Sandborn, M.; Olea, C.; Gilbert, H.; Elnashar, A.; Spencer-Smith, J.; Schmidt, D.C. A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with chatgpt. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2302.11382. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, H. Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.10997. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.J.; Wang, J.; Li, G. Survey of vector database management systems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.14021. [Google Scholar]

- Topsakal, O.; Akinci, T.C. Creating large language model applications utilizing langchain: A primer on developing llm apps fast. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Engineering and Natural Sciences, 2023; Vol. 1, pp. 1050–1056.

- Karau, H.; Lublinsky, B. Scaling Python with Ray; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: location, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lathkar, M. Getting started with FastAPI. In High-Performance Web Apps with FastAPI: The Asynchronous Web Framework Based on Modern Python; Springer: location, 2023; pp. 29–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Yu, T.; Xu, Y.; Lee, N.; Ishii, E.; Fung, P. Towards mitigating LLM hallucination via self reflection. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, 2023, pp. 1827–1843. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).