A diagnosis for febrile rash in returning travelers from the tropics presents a diagnostic challenge. It should immediately point to arboviral disease to avoid any further transmission in non-endemic country where the vector is widespread.

The diagnosis may be oriented by the epidemiological background, the natural history of the disease, the clinical signs, and routine lab testing[

1].

In September 2023, a 39-year-old male presented with fever (39

oC), headache, myalgia, and a distinctive rash as shown in (

Figure 1). Additionally, laboratory analyses indicated leukocytes at 4700/µL, neutrophils at 3619/µL, lymphocytes at 705/µL, and a platelet count of 177,000/µL. Notably, dengue NS1 test returned negative on the initial day of illness, but anti-dengue IgM and IgG were detectable on day five of illness.

Dengue, a mosquito-borne flavivirus with four serotypes, circulates in

Aedes mosquitoes and viremic humans, ranking second only to malaria as the primary cause of fever in returning travelers and contribute to cluster outbreaks in individuals with naïve immunity to dengue viruses[

2,

3].

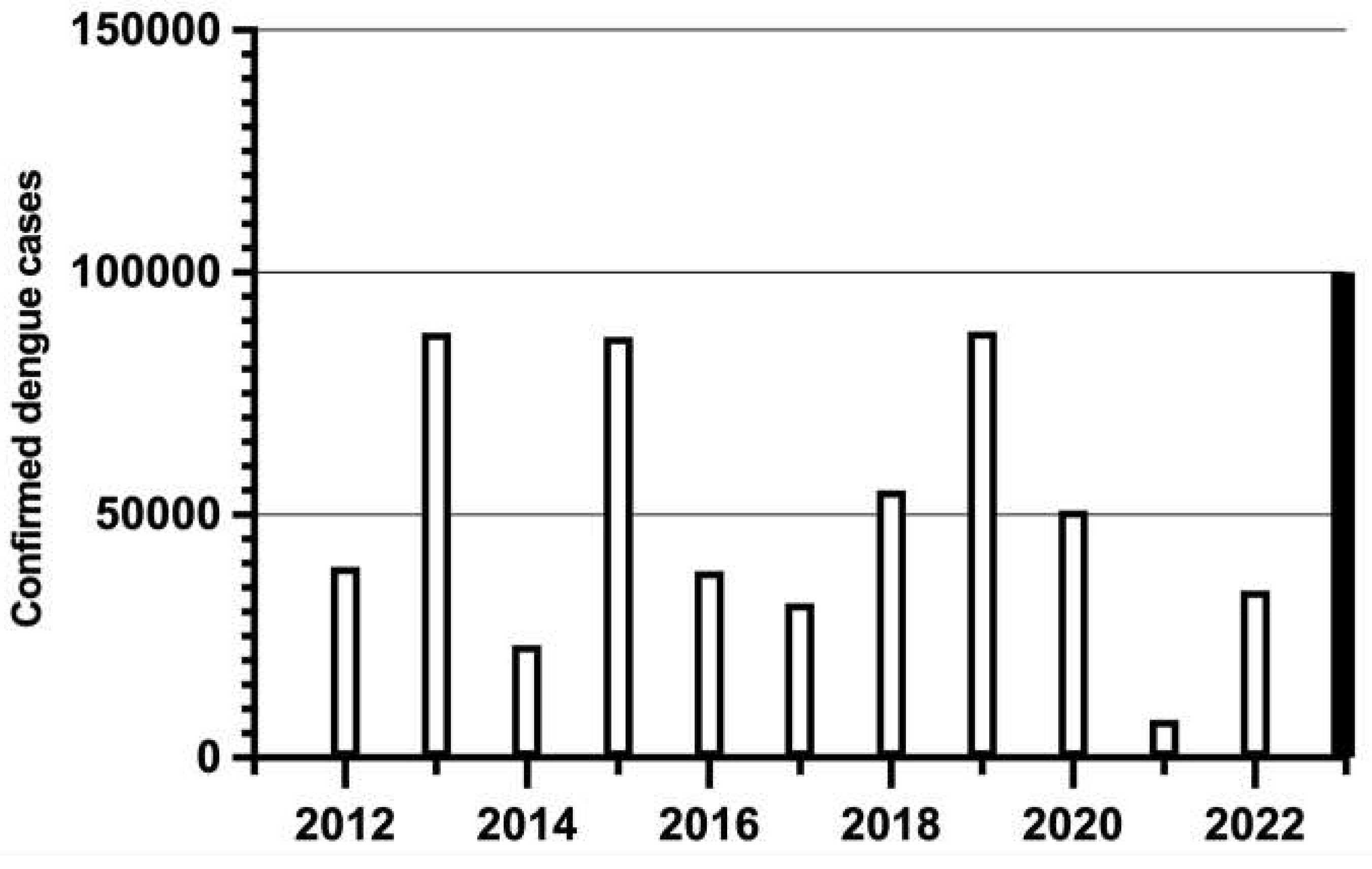

Dengue virus infection poses a significant health threat to Thailand, particularly in Bangkok. A decade ago, in 2013, the incidence rates were alarmingly high, with 136.6 cases per 100,000 population[

4]. In the same year, dengue infection accounted for 40% of the primary causes of illness in patients seeking treatment at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases[

5]. The incidence of dengue in 2023 crossed 111 cases per 100,000 population according to the Ministry of Public Health in Thailand (

Figure 2).

This recent large outbreak in Thailand, raises concerns about potential spread to non-endemic areas (

Figure 2). The influx of 28 million travelers in 2023, many without immunity, heightens concerns about its transmission to temperate regions where potential vectors may exist.

This is well illustrated in France, a country where Aedes albopictus is present. Between May 1, 2023, and September 29, 2023, a total of 1099 cases of dengue were imported in France, and Thailand emerged as the primary source of dengue-infected travelers after French overseas territories. Several of these imported cases led to six autochtonous dengue clusters, involving 31 cases, with 1 to 11 cases per cluster.

This alert emphasizes to heightened vigilance and considering dengue as a potential diagnosis when encountering travelers with febrile rash even before confirmation with lab tests, and take immediate steps to isolate the patients, preventing further autochthonous transmission. These proactive measures are essential for reducing outbreak risk and averting public health crises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.I., A.P., and E.C.; methodology, H.A.I., A.P., R.C., S.C., and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.I and E.C.; writing—review and editing, A.P., R.C., S.C. H.A.I., and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. For this case report, an exemption was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (MUTM-EXMPT 2024-003), on February 12, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the study subject involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patient who volunteered to be part of this report and thank all the staff at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hochedez, P. , et al., Management of travelers with fever and exanthema, notably dengue and chikungunya infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2008. 78(5): p. 710-3.

- Wilder-Smith, A. , et al., Dengue. Lancet, 2019. 393(10169): p. 350-363.

- Imad, H.A. , et al., A Cluster of Dengue Cases in Travelers: A Clinical Series from Thailand. Trop Med Infect Dis, 2021. 6(3).

- Thisyakorn, U. , et al., Epidemiology and costs of dengue in Thailand: A systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2022. 16(12): p. e0010966.

- Luvira, V. , et al., Etiologies of Acute Undifferentiated Febrile Illness in Bangkok, Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2019. 100(3): p. 622-629.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).