Submitted:

23 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Disseminate standards for collection of data from participants enrolled in ME/CFS studies that is, a set of recommended data elements (RDEs).

- Consider language and cultural issues, as well as equity, diversity and concerns on inclusion criteria such as design and methods.

- Improve data quality and research on ME/CFS for benefiting patients and practitioners.

Development Process

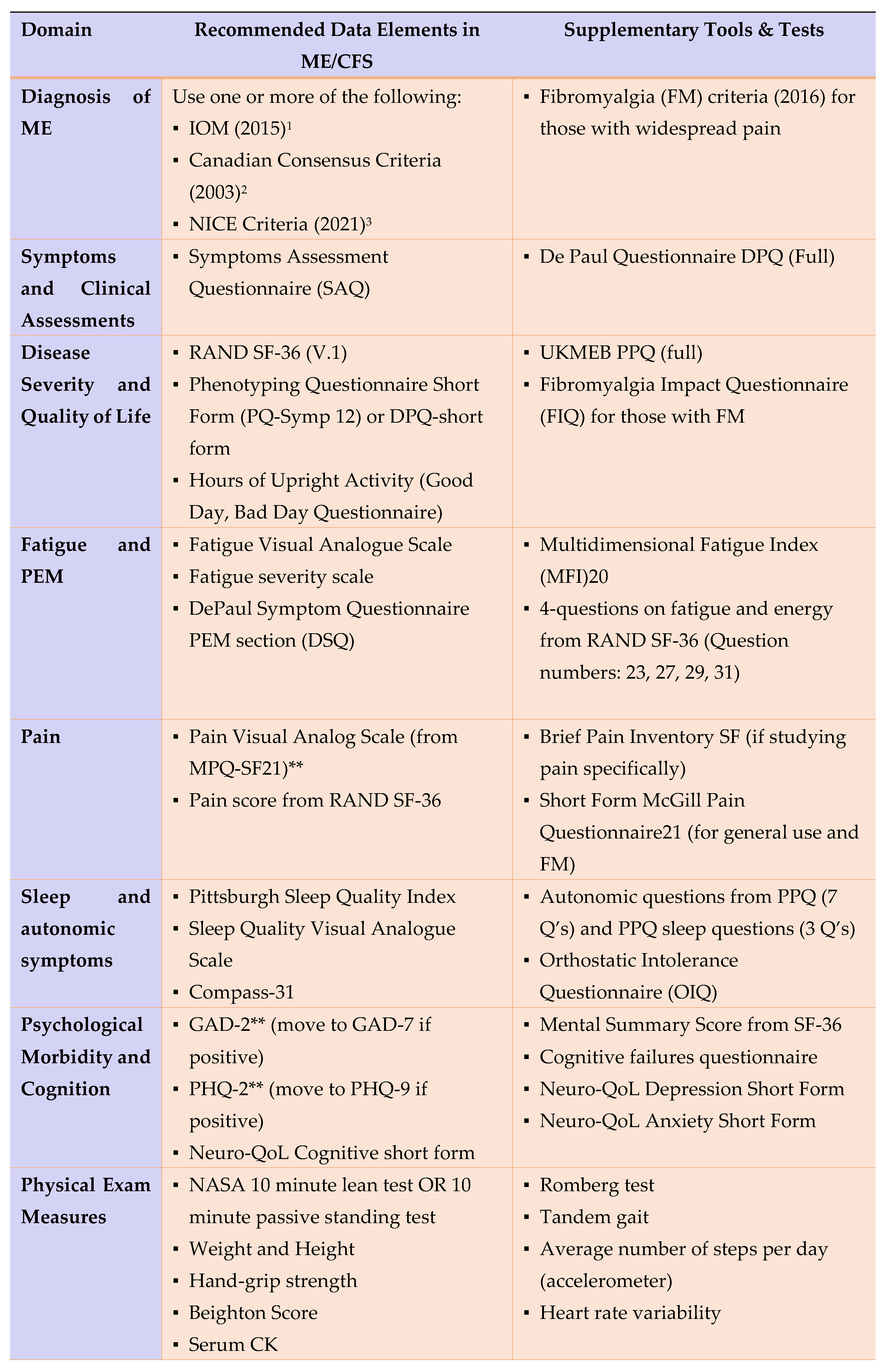

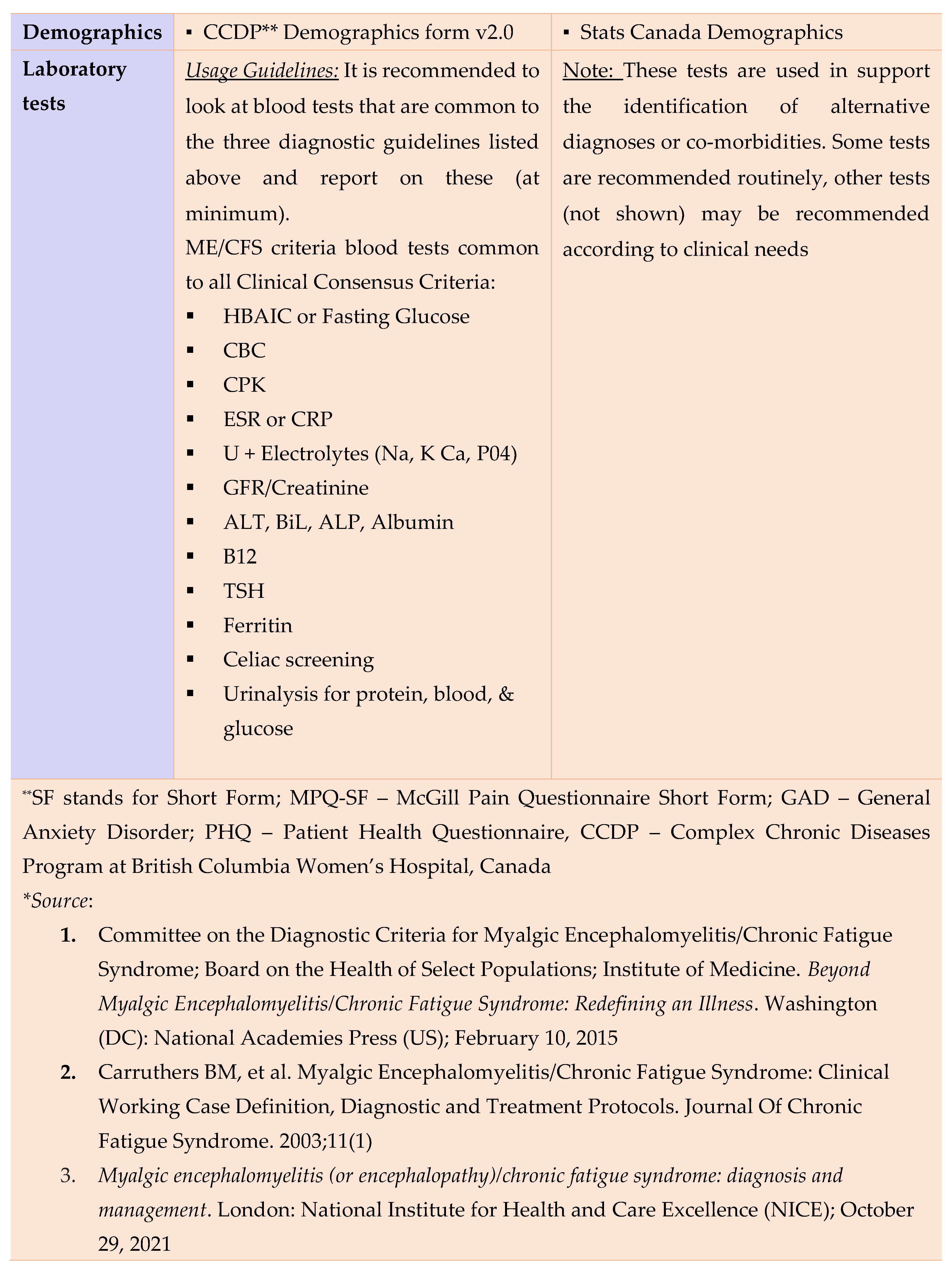

Data Collection Standardization

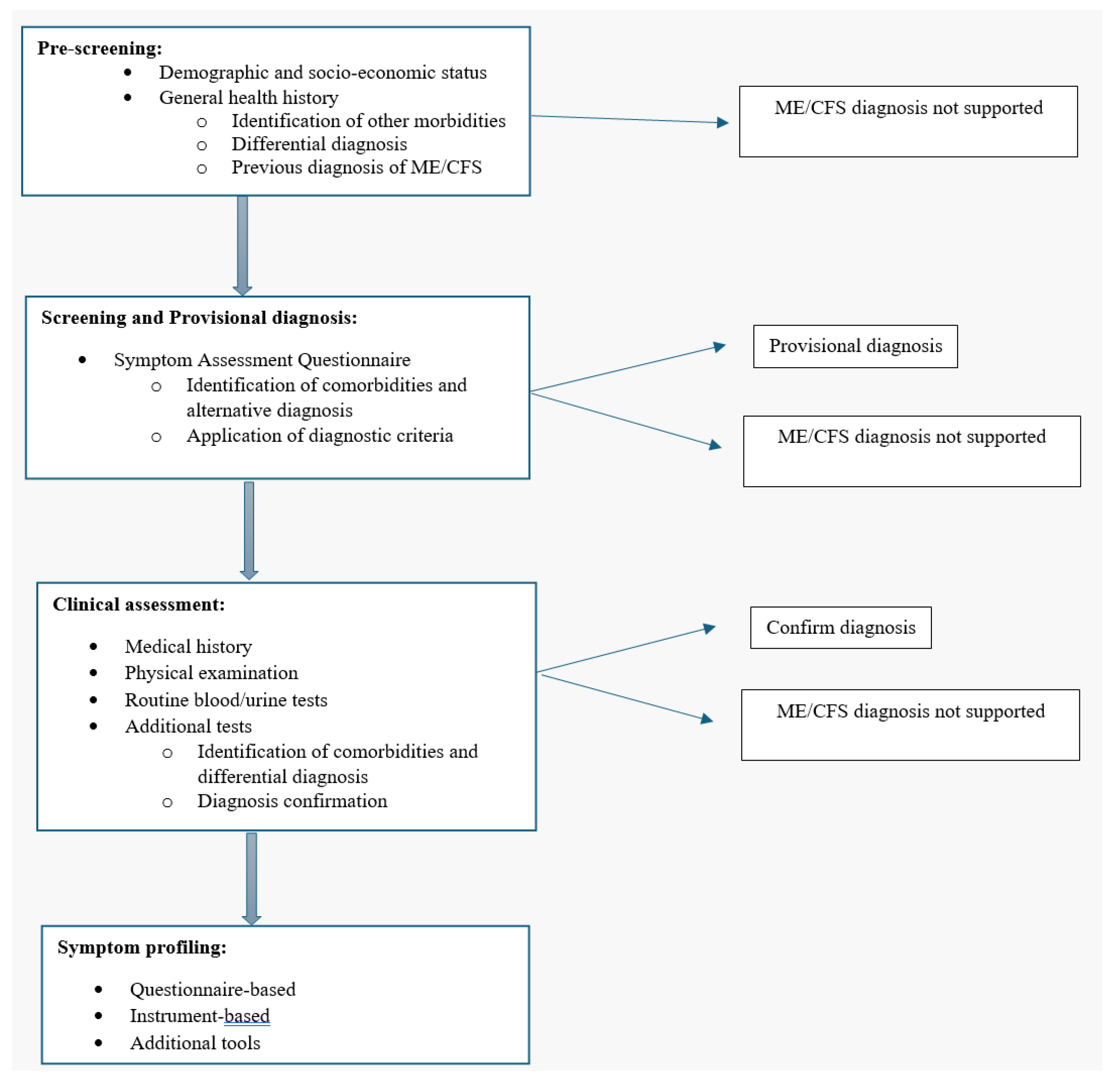

- (a)

- Core General Information

- (b)

- Provisional diagnosis

- (c)

- Clinical assessment and d) symptom profiling (diagnosis confirmation) (reference: MDE’s by ICanCME WG5)

Additional Considerations on ME/CFS Research

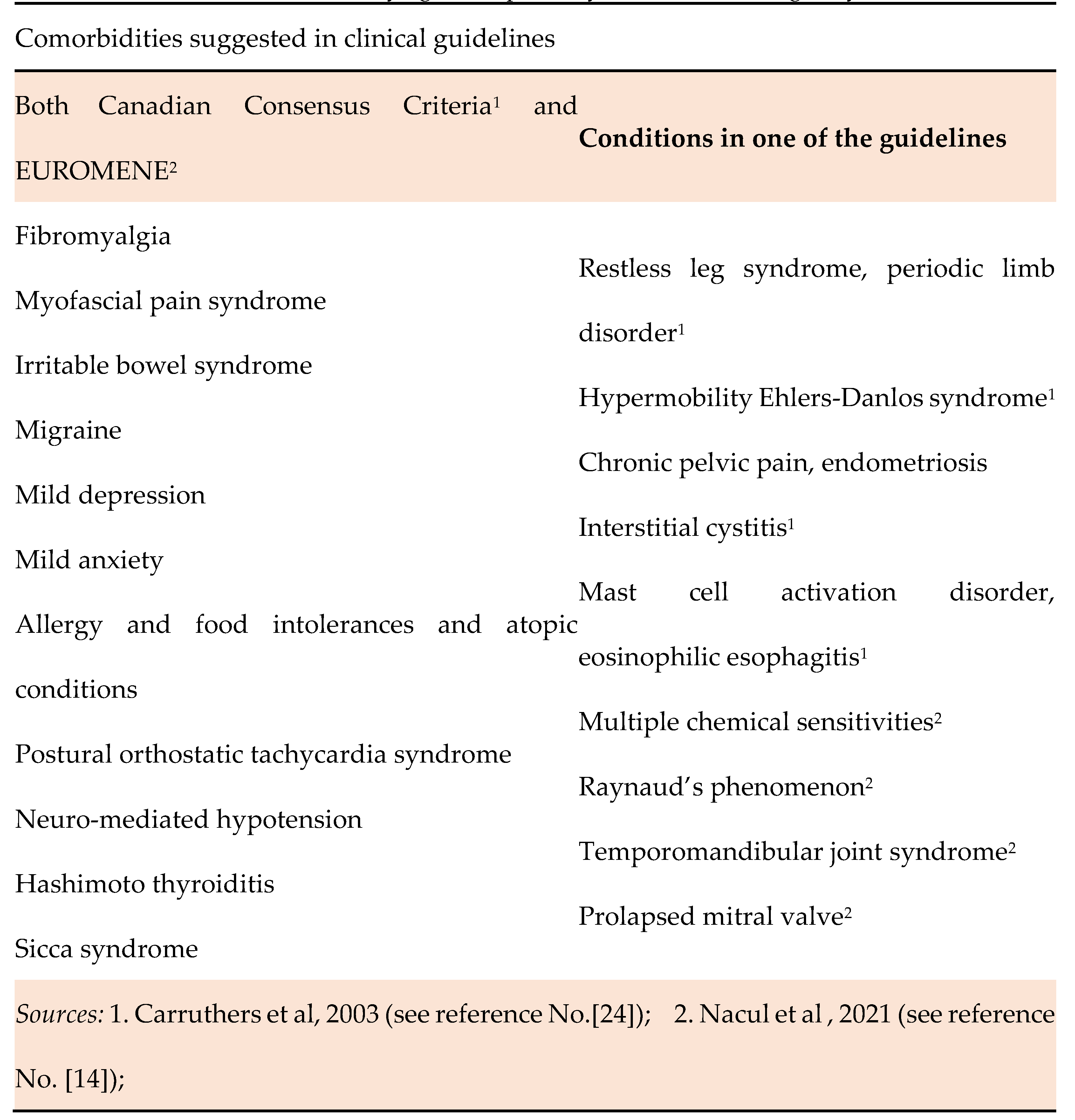

- Comorbidities and their identification in ME/CFS

- 2.

- Long-COVID and ME/CFS

- 3.

- Concerns of bias in epidemiological studies

- 4.

- Equity Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Considerations

- 5.

- Language and Culture Considerations

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Lim, E.-J.; Son, C.-G. Review of case definitions for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Journal of Translational Medicine 2020, 18, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, B.M.; van de Sande, M.I.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; Staines, D.; Powles, A.C.P.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria. Journal of Internal Medicine 2011, 270, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.S.; Bradley, A.S.; Bishop, K.N.; Kiani-Alikhan, S.; Ford, B. Chronic fatigue syndrome, the immune system and viral infection. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2012, 26, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, E.M.; Geraghty, K.; Kingdon, C.C.; Palla, L.; Nacul, L. A logistic regression analysis of risk factors in ME/CFS pathogenesis. BMC Neurol 2019, 19, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacul, L.; O'Boyle, S.; Palla, L.; Nacul, F.E.; Mudie, K.; Kingdon, C.C.; Cliff, J.M.; Clark, T.G.; Dockrell, H.M.; Lacerda, E.M. How Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Progresses: The Natural History of ME/CFS. Frontiers in Neurology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacul, L.C.; Lacerda, E.M.; Pheby, D.; Campion, P.; Molokhia, M.; Fayyaz, S.; Leite, J.C.D.C.; Poland, F.; Howe, A.; Drachler, M.L. Prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: a repeated cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Medicine 2011, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics, C. CCHS_Ann_2015-16_stata_dta.zip. In Canadian Community Health Survey: Public Use Microdata File, 2015/2016, V1 ed.; Statistics, C., Ed. Abacus Data Network: 2018; hdl:11272.1/AB2/VXU9UQ/DL3LBC.

- Schäfer, M.L. [On the history of the concept neurasthenia and its modern variants chronic-fatigue-syndrome, fibromyalgia and multiple chemical sensitivities]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2002, 70, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubMed. Number of articles published in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Availabe online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=myalgic+encephalomyelitis+chronic+fatigue+syndrome&filter=simsearch3.fft&filter=dates.2010-2022 (accessed on.

- Jason, L.A.; Sunnquist, M.; Brown, A.; Evans, M.; Vernon, S.D.; Furst, J.; Simonis, V. Examining case definition criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis. Fatigue 2014, 2, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacul, L.C.; Lacerda, E.M.; Campion, P.; Pheby, D.; Drachler, M.d.L.; Leite, J.C.; Poland, F.; Howe, A.; Fayyaz, S.; Molokhia, M. The functional status and well being of people with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and their carers. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirin, A.A. A preliminary estimate of the economic impact of long COVID in the United States. Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior 2022, 10, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excellence, N.I.f.H.a.C. Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management. NICE Guideline, No.206; National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, 2021.

- Nacul, L.; Authier, F.J.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Lorusso, L.; Helland, I.B.; Martin, J.A.; Sirbu, C.A.; Mengshoel, A.M.; Polo, O.; Behrends, U.; et al. European Network on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (EUROMENE): Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis, Service Provision, and Care of People with ME/CFS in Europe. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICAnCME. What is ICanCME? Availabe online: https://www.icancme.ca/ (accessed on February 05).

- Haney E, S.B. McDonaugh M. Diagnostic Methods for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Systematic Review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Annals of Internal Medicine 2015, 162, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-López, F.; Mudie, K.; Wang-Steverding, X.; Bakken, I.J.; Ivanovs, A.; Castro-Marrero, J.; Nacul, L.; Alegre, J.; Zalewski, P.; Słomko, J.; et al. Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Burden of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Across Europe: Current Evidence and EUROMENE Research Recommendations for Epidemiology. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroke), N.N.I.f.N.D.a. NINDS Common Data Elements - Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 01/09/2020 ed.; National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke: 2020.

- Mudie, K.; Estévez-López, F.; Sekulic, S.; Ivanovs, A.; Sepulveda, N.; Zalewski, P.; Mengshoel, A.M.; De Korwin, J.-D.; Hinic Capo, N.; Alegre-Martin, J.; et al. Recommendations for Epidemiological Research in ME/CFS from the EUROMENE Epidemiology Working Group. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, B.M.; Jain, A.K.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Lerner, A.M.; Bested, A.C.; Flor-Henry, P.; Joshi, P.; Powles, A.C.P.; et al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal Of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome 2003, 11, 7–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM. Institute of Medicine, Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. Mil Med 2015, 180, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, E.B.; Nacul, L.; Mengshoel, A.M.; Helland, I.B.; Grabowski, P.; Krumina, A.; Alegre-Martin, J.; Efrim-Budisteanu, M.; Sekulic, S.; Pheby, D.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Investigating care practices pointed out to disparities in diagnosis and treatment across European Union. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0225995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacul, L.; Lacerda, E.M.; Kingdon, C.C.; Curran, H.; Bowman, E.W. How have selection bias and disease misclassification undermined the validity of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome studies? J Health Psychol 2019, 24, 1765–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, B.M.; Jain, A.K.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Lerner, A.M.; Bested, A.C.; Flor-Henry, P.; Joshi, P.; Powles, A.C.P.; et al. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Clinical Working Case Definition, Diagnostic and Treatment Protocols. Journal Of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome 2003, 11, 7–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, V.; Beckerman, H.; Lankhorst, G.J.; Bouter, L.M. How to measure comorbidity. a critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol 2003, 56, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guralnik, J.M. Assessing the impact of comorbidity in the older population. Ann Epidemiol 1996, 6, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K.J.; Löhn, M. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Comorbidities: Linked by Vascular Pathomechanisms and Vasoactive Mediators? Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Marrero, J.; Faro, M.; Aliste, L.; Sáez-Francàs, N.; Calvo, N.; Martínez-Martínez, A.; de Sevilla, T.F.; Alegre, J. Comorbidity in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Psychosomatics 2017, 58, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, B.S.; Linn, M.W.; Gurel, L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1968, 16, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskulin, D.C.; Athienites, N.V.; Yan, G.; Martin, A.A.; Ornt, D.B.; Kusek, J.W.; Meyer, K.B.; Levey, A.S. Comorbidity assessment using the Index of Coexistent Diseases in a multicenter clinical trial. Kidney Int 2001, 60, 1498–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.L.; Weitzer, D.J. Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)—A Systemic Review and Comparison of Clinical Presentation and Symptomatology. Medicina 2021, 57, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Lipkin, W.I. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1187163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano JB, M.S., Marshall JC, RFelan P, Diaz JV. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2022, 22, E102–E107. [CrossRef]

- Woodrow, M.; Carey, C.; Ziauddeen, N.; Thomas, R.; Akrami, A.; Lutje, V.; Greenwood, D.C.; Alwan, N.A. Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Long COVID. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, R.; Armstrong, S.M.; Salvant, E.; Ritzker, C.; Feld, J.; Biondi, M.J.; Tsui, H. Recognition of Long-COVID-19 Patients in a Canadian Tertiary Hospital Setting: A Retrospective Analysis of Their Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, C. Long-Covid and ME/CFS - Are they the same condition? Availabe online: https://meassociation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/LONG-COVID-AND-MECFS-ARE-THEY-THE-SAME-CONDITION-MAY-2023.pdf (accessed on Feb 27).

- UK, G.U.C.C.-i.t. Coronavirus cases in England. Availabe online: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases?areaType=nation&areaName=England (accessed on Feb 27).

- Gordis, L. Bias, Confounding, and Interaction. In Epidemiology, Saunders Elsevier: 2008; pp. 247–256.

- Rothman, K.J. Epidemiology. An Introduction. In Epidemiology. An Introduction, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2002; pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Last, J. A Dictionary of Epidemiology, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baguley, T. Understanding statistical power in the context of applied research. Applied Ergonomics 2004, 35, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.S.C.; Nunes, B.P.; Duro, S.M.S.; Facchini, L.A. Socioeconomic determinants of access to health services among older adults: a systematic review. Revista de Saúde Pública 2017, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, C.; Giotas, D.; Nacul, L.; Lacerda, E. Health Care Responsibility and Compassion-Visiting the Housebound Patient Severely Affected by ME/CFS. Healthcare 2020, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuluunbaatar E, T.M., Nacul L. Epidemiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis among individuals with self-reported Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and their health-related quality of life in Canada. In Proceedings of International Association of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (IACFSME) 2023, New York, New York, USA.

- Hunt, S.M.; Bhopal, R. Self report in clinical and epidemiological studies with non-English speakers: the challenge of language and culture. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2004, 58, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C. Translation of Questionnaires for Use in Different Languages and Cultures. In Handbook of Psychology and Diabetes, Routledge: 1994; p. 13.

- Statistics Canada, G.o.C. Indigenousidentity by Registered or Treaty Indian Status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts. Availabe online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/ (accessed on November 15).

- Canada, G.o. Indigenous health care in Canada. Availabe online: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1626810177053/1626810219482 (accessed on November 17).

- Nguyen, N.H.; Subhan, F.B.; Williams, K.; Chan, C.B. Barriers and Mitigating Strategies to Healthcare Access in Indigenous Communities of Canada: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Project, B.G. Our Participants. Availabe online: https://www.bcgenerationsproject.ca/about/our-participants/ (accessed on March 21).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).