Submitted:

21 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

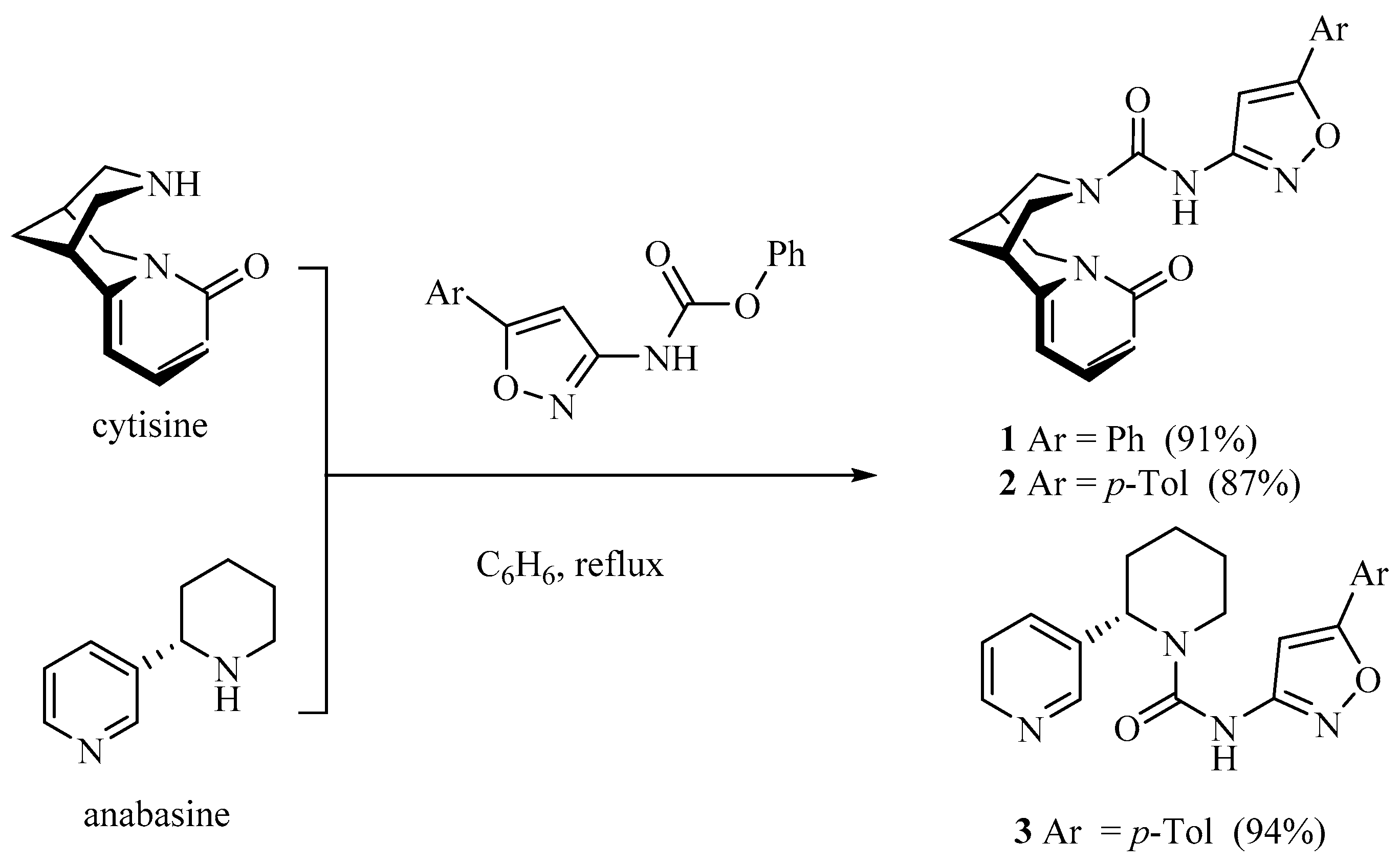

2.1. Chemistry

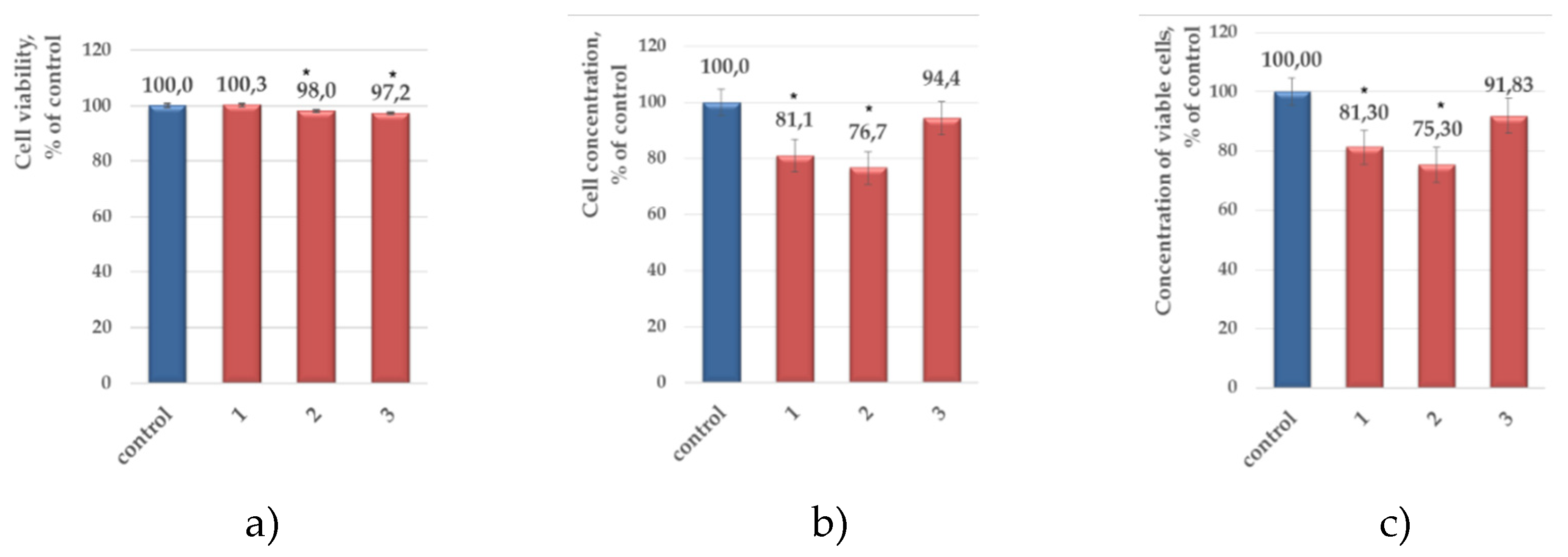

2.2. Evaluation of Antitumor Activity

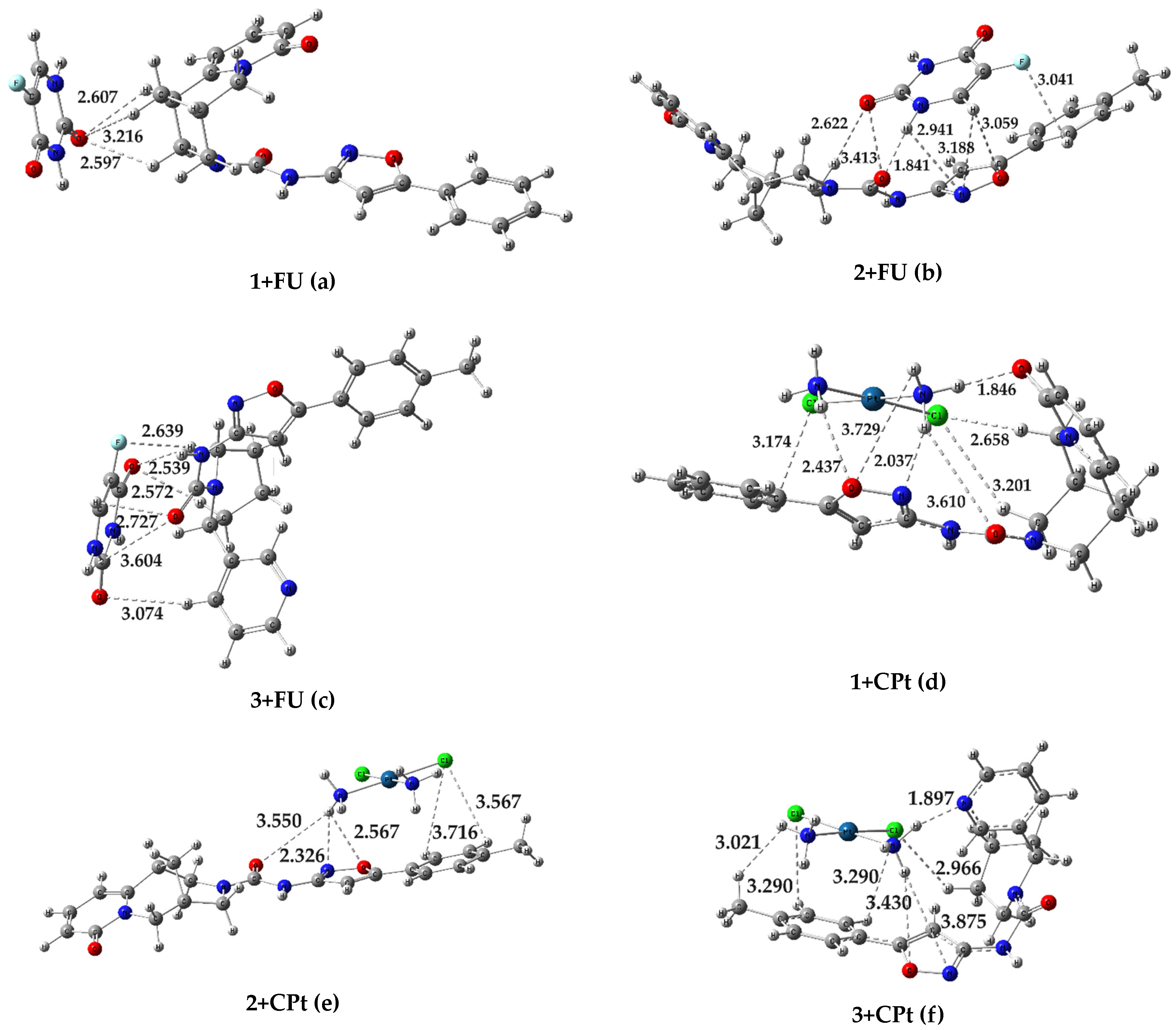

2.3. Quantum Chemical Modeling

| Conjugate | ∆Ef, а.е. | ∆Ef, kcal/mol |

| 1+FU | -0,009871226 | -6,19 |

| 2+FU | -0,026896256 | -16,88 |

| 3+FU | -0,018223976 | -11,44 |

| 1+CPt | -0,03977506 | -24.96 |

| 2+CPt | -0,02215013 | -13.90 |

| 3+CPt | -0,03375495 | -21.18 |

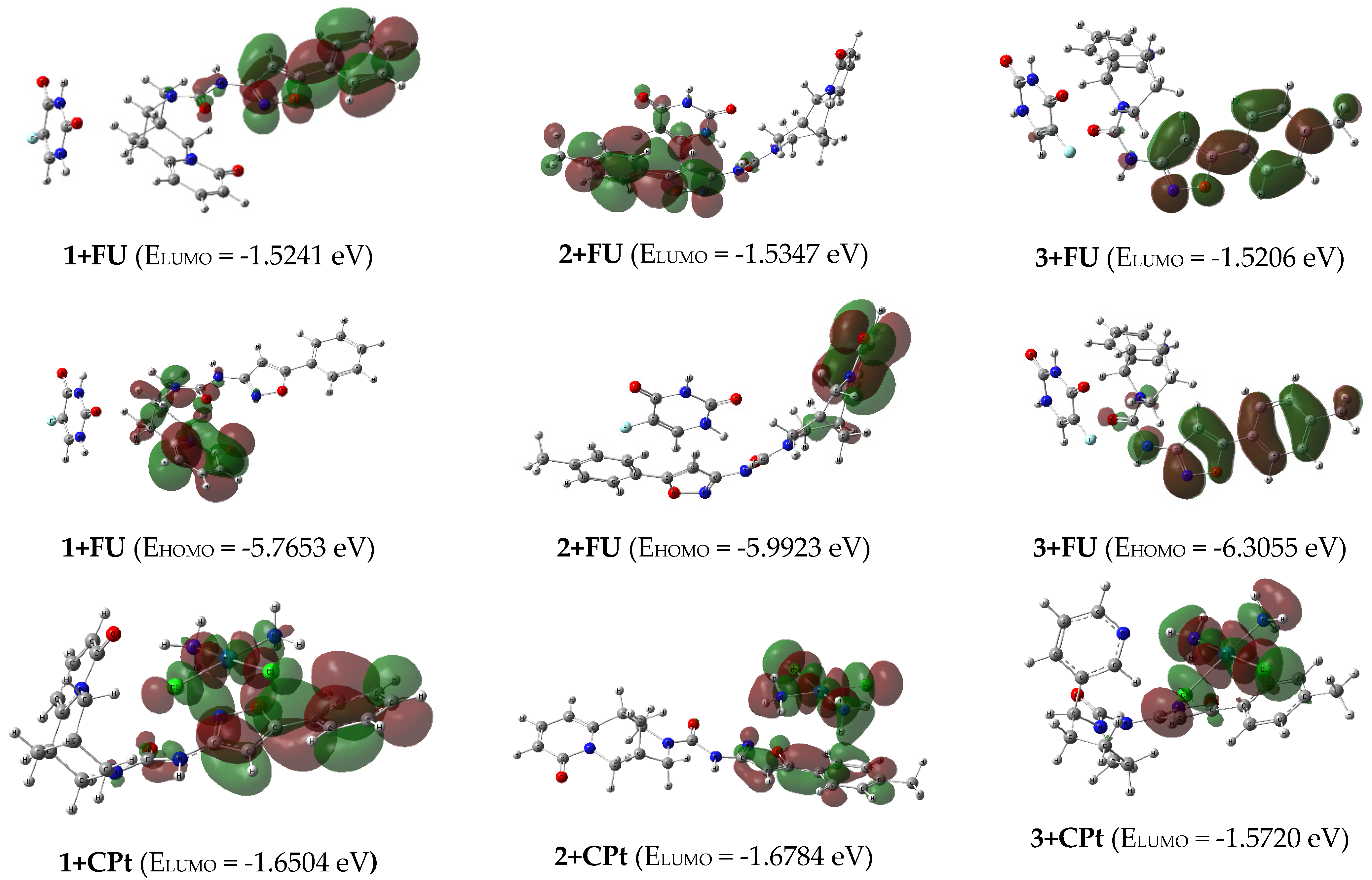

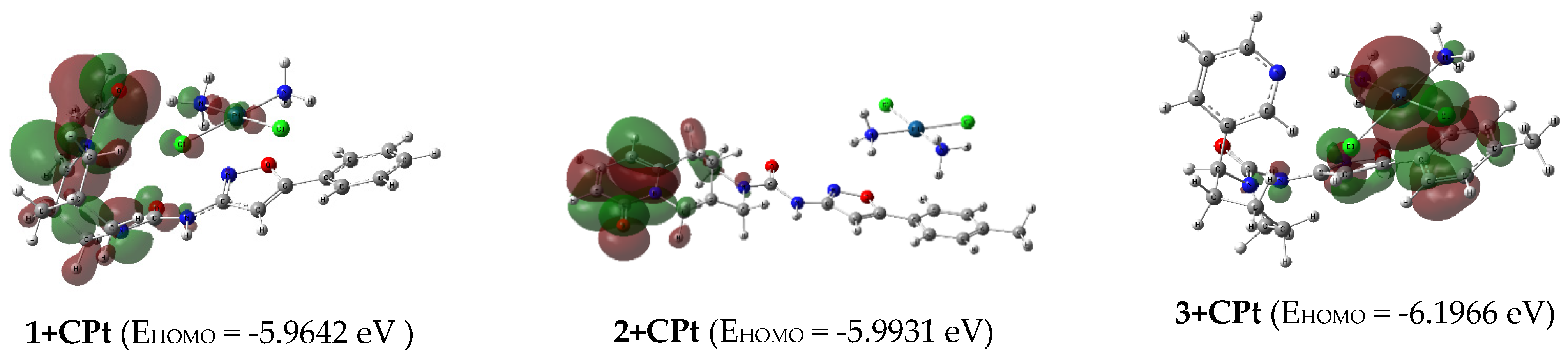

| ЕHOMO, eV | ЕLUMO, eV | ∆E, eV | μ (eV) | χ (eV) | η (eV) | S (eV-1) | ω (eV) | D, Db | |

| 1 | -5.7689 | -1.5192 | 4.2496 | -3.6441 | 3.6441 | 2.1248 | 0.2353 | 3.1248 | 10.24 |

| 2 | -5.9797 | -1.4343 | 4.5454 | -3.7070 | 3.7070 | 2.2727 | 0.2200 | 3.0232 | 5.24 |

| 3 | -6.2992 | -1.5160 | 4.7833 | -3.9076 | 3.9076 | 2.3917 | 0.2091 | 3.1922 | 6.94 |

| FU | -6.6562 | -1.2798 | 5.3765 | -3.9680 | 3.9680 | 2.6883 | 0.1860 | 2.9281 | 5.13 |

| 1+FU | -5.7653 | -1.5241 | 4.2412 | -3.6447 | 3.6447 | 2.1206 | 0.2358 | 3.1321 | 8.23 |

| 2+FU | -5.9923 | -1.5347 | 4.4575 | -3.7635 | 3.7635 | 2.2288 | 0.2243 | 3.1775 | 3.57 |

| 3+FU | -6.3055 | -1.5206 | 4.7849 | -3.9131 | 3.9131 | 2.3925 | 0.2090 | 3.2000 | 2.01 |

| CPt | -6.5305 | -1.7475 | 4.7830 | -4.1390 | 4.1390 | 2.3915 | 0.2091 | 3.5817 | 15.94 |

| 1+CPt | -5.9642 | -1.6504 | 4.3139 | -3.8073 | 3.8073 | 2.1570 | 0.2318 | 3.3601 | 9.44 |

| 2+CPt | -5.9931 | -1.6784 | 4.3147 | -3.8358 | 3.8358 | 2.1574 | 0.2318 | 3.4100 | 19.75 |

| 3+CPt | -6.1966 | -1.5720 | 4.6246 | -3.8843 | 3.8843 | 2.3123 | 0.2162 | 3.2625 | 7.77 |

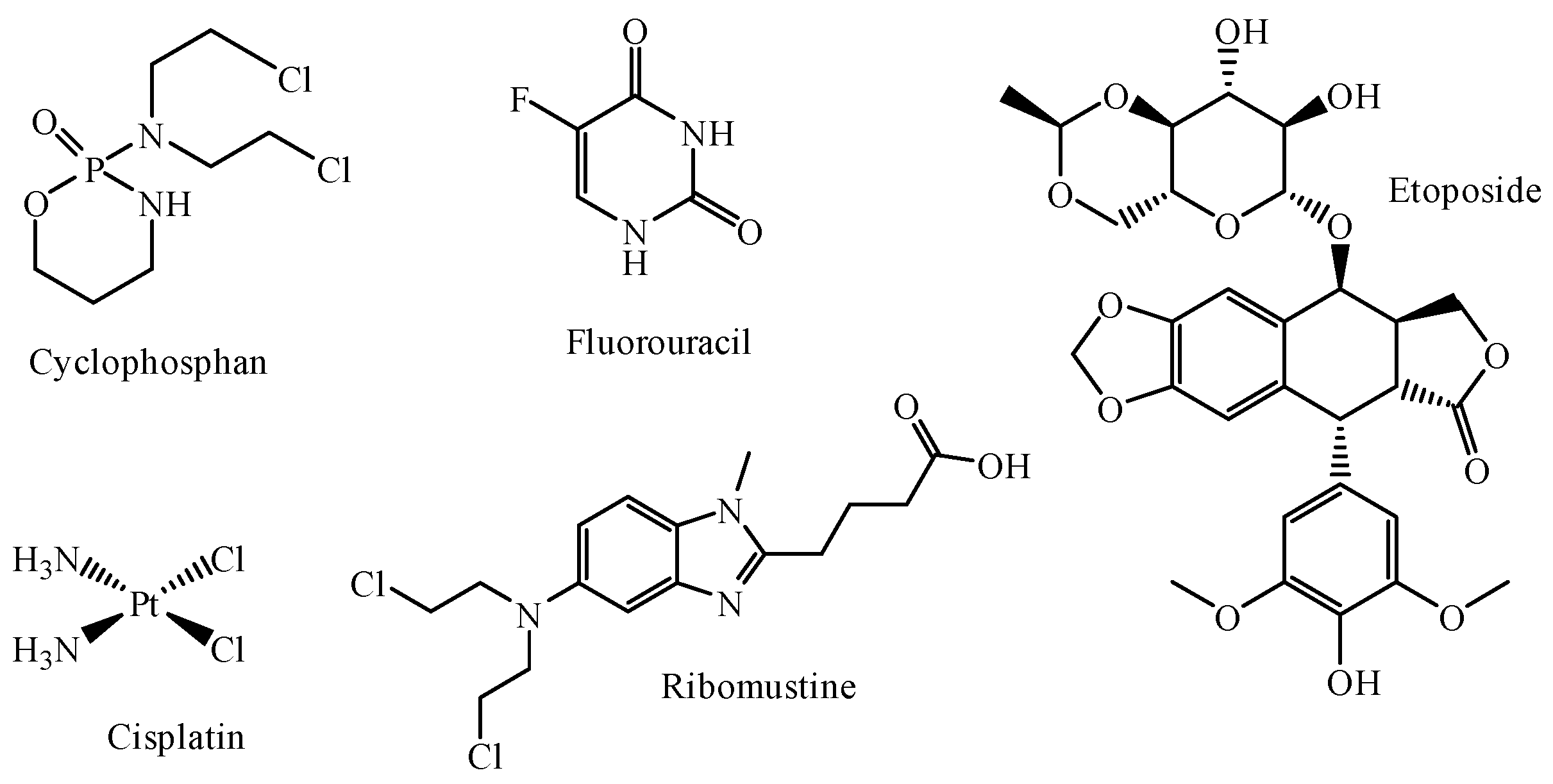

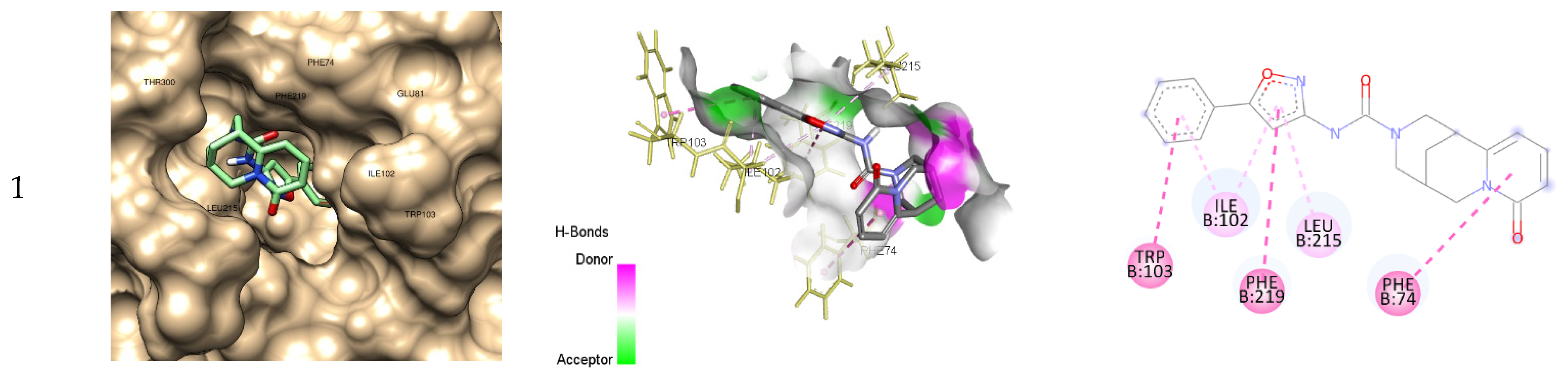

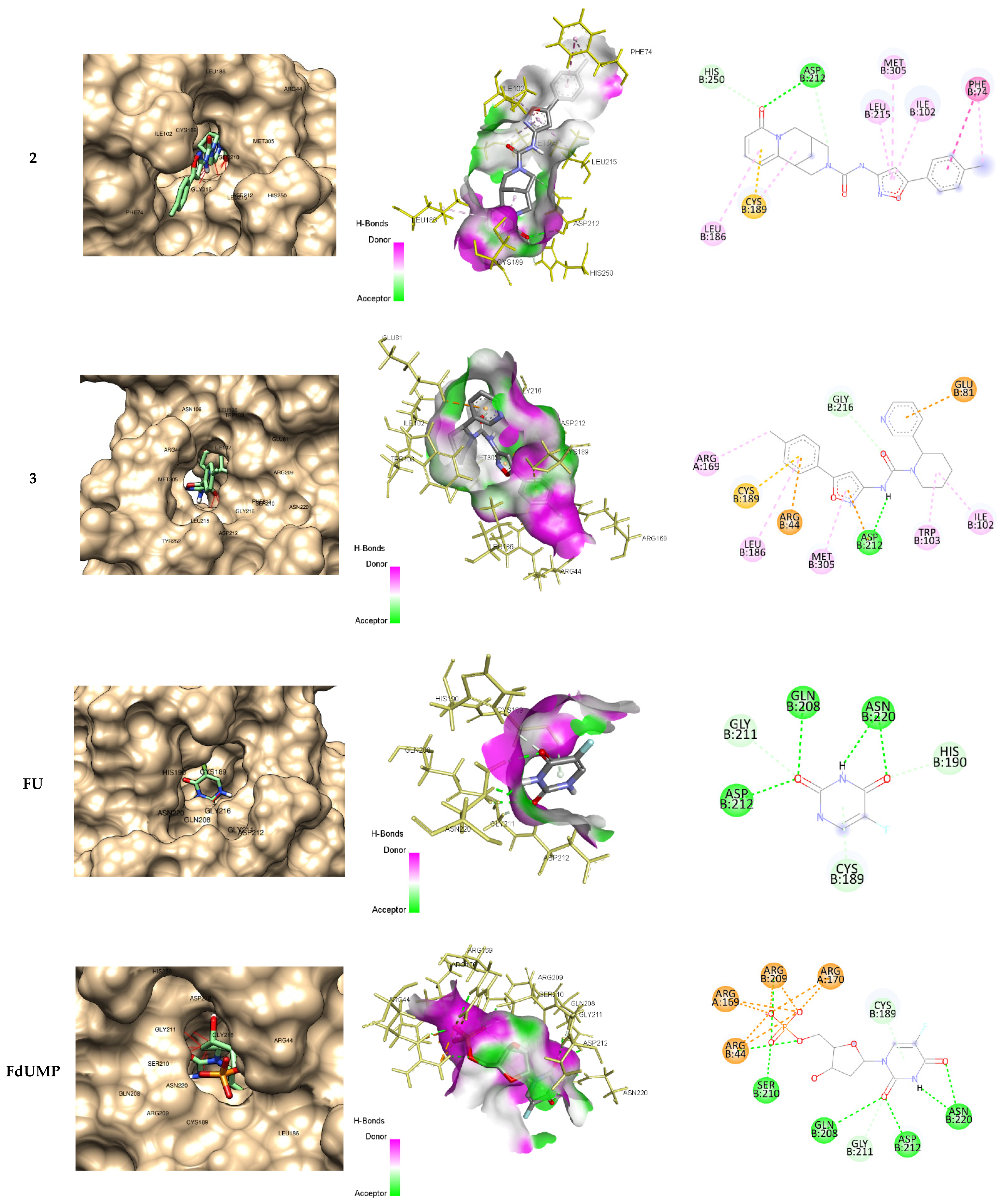

2.4. Docking Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Chemistry Section

3.1.1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Anabasine and Cytisine Ureas 1-3.

3.2. In Vitro Biological Assays

3.3. Quantum Chemical Methods.

3.4. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

References

- Duarte, D.; Vale, N. Evaluation of synergism in drug combinations and reference models for future orientations in oncology. Curr. Res. Pharmacol Drug Discov 2022, 3, 100110. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, C.; Ko, S.G. Synergistic effects of natural products in combination with anticancer agents in prostate cancer: A scoping review. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 963317. [CrossRef]

- Gaston, T.E.; Mendrick, D.L.; Paine, M.F.; Roe, A.L.; Yeung, C.K. Natural is not synonymous with “Safe”: Toxicity of natural products alone and in combination with pharmaceutical agents. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2020, 113, 104642. [CrossRef]

- Hackman, G.L.; Collins, M.; Lu, X.; Lodi, A.; DiGiovanni, J.; Tiziani, S. Predicting and Quantifying Antagonistic Effects of Natural Compounds Given with Chemotherapeutic Agents: Applications for High-Throughput Screening. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12(12), 3714. [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.M.; Hawash, M.; Amer, J.; Jarrar, A.; Qadri, S.; Alnimer, I.; Sharaf, A.; Zalmoot, R.; Hammoudie, O.; Hameedi, S.; Mousa, A. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Isoxazole-Amide Analogues as Anticancer and Antioxidant Agents. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 6633297. [CrossRef]

- Arya, G.C.; Kaur, K.; Jaitak, V. Isoxazole derivatives as anticancer agent: A review on synthetic strategies, mechanism of action and SAR studies. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 221, 113511. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Park, S.E.; Mozaffari, S.; El-Aarag, B.; Parang, K.; Tiwari, R.K. Design, Synthesis, and Antiproliferative Activity of Benzopyran-4-One-Isoxazole Hybrid Compounds. Molecules 2023, 28, 4220. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Mo, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, H. The recent progress of isoxazole in medicinal chemistry. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 26(12), 3065. [CrossRef]

- Kolesnik, I.A.; Kletskov, A.V.; Potkin, V.I., Knizhnikov, V.A.; Zvereva, T.D.; Kurman, P.V.; Tokalchik, Yu.P.; Kulchitsky, V.A. Glycylglycine and Its Morpholide Derivatives Containing 5-(p-Tolyl)isoxazole and 4,5-Dichloroisothiazole Moieties. Russ J Org Chem 2021, 57, 1584. [CrossRef]

- Kletskov, A.V.; Potkin, V.I.; Kolesnik, I.A.; Petkevich, S.K.; Kvachonak, A.V.; Dosina M.O.; Loiko D.O.; Larchenko M.V.; Pashkevich, S.G.; Kulchitsky, V.A. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Novel Comenic Acid Derivatives Containing Isoxazole and Isothiazole Moieties. Natural Product Communications 2018, 13(11), 1507. [CrossRef]

- Potkin, V. I.; Petkevich, S. K.; Kletskov, A. V.; Zubenko, Y. S.; Kurman, P. V.; Pashkevich, S. G.; Kulchitskiy, V. A. The synthesis of isoxazolyl- and isothiazolylcarbamides exhibiting antitumor activity. Russian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2014, 50(11), 1667. [CrossRef]

- Potkin, V.; Pushkarchuk, A.; Zamaro, A.; Zhou, H.; Kilin, S.; Petkevich, S.; Kolesnik, I.; Michels, D.L.; Lyakhov, D.A.; Kulchitsky, V.A. Effect of the isotiazole adjuvants in combination with cisplatin in chemotherapy of neuroepithelial tumors: experimental results and modeling. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 13624. [CrossRef]

- Kulchitsky, V.A.; Potkin, V.I.; Zubenko, Y.S.; Chernov, A.N.; Talabaev. M.V.; Demidchik, Y.E.; Petkevich, S.K.; Kazbanov, V.V.; Gurinovich, T.A.; Roeva, M.O.; Grigoriev, D.G.; Kletskov, A.V.; Kalunov, V.N. Cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic drugs and heterocyclic compounds at application on the cells of primary culture of neuroepithelium tumors. Medicinal Chemistry 2012, 8(1), 22-32. [CrossRef]

- Giakoumettis, D.; Kritis, A.; Foroglou, N. C6 cell line: the gold standard in glioma research. Hippokratia 2018, 22(3), 105.

- Dabbish, E.; Scoditti, S.; Shehata, M.N. I.; Ritacco, I.; Ibrahim, M.A.A., Shoeib, T.; Sicilia, E. Insights on cyclophosphamide metabolism and anticancer mechanism of action: A computational study. J Comput Chem 2024, 45, 663. [CrossRef]

- Knüpfer, H.; Stanitz, D.; Preiss, R. CYP2C9 polymorphisms in human tumors. Anticancer Res 2006, 26(1A), 299.

- Uthansingh, K.; Parida, P.K.; Pati, G.K.; Sahu, M.K.; Padhy, R.N. Evaluating the Association of Genetic Polymorphism of Cytochrome p450 (CYP2C9*3) in Gastric Cancer Using Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (PCR-RFLP). Cureus 2022, 14(7), e27220. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Aldebasi, Y.H.; Alsuhaibani, S.A.; Khan, M.A. Thymoquinone Augments Cyclophosphamide-Mediated Inhibition of Cell Proliferation in Breast Cancer Cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2019, 20(4), 1153. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Lazarín, A.L.; Martínez-Torres, A.C.; de la Hoz-Camacho, R.; Guzmán-Aguillón, O.L.; Franco-Molinaa, M.A.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C. The bovine dialyzable leukocyte extract, immunepotent CRP, synergically enhances cyclophosphamide-induced breast cancer cell death, through a caspase-independent mechanism. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 131. [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, S.A.; Hamdy, O.; Soliman, M.M.; El Gayar, A.M.;, El-Mesery, M. Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide in combination with pitavastatin or simvastatin against breast cancer cells. Med. Oncol. 2023, 41(1), 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yin, Y.; Xu S.J.; Chen, W.S. 5-Fluorouracil: mechanisms of resistance and reversal strategies. Molecules 2008, 13(8), 1551. [CrossRef]

- Azwar, S.; Seow, H.F.; Abdullah, M.; Faisal Jabar M.; Mohtarrudin, N. Recent Updates on Mechanisms of Resistance to 5-Fluorouracil and Reversal Strategies in Colon Cancer Treatment. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10(9), 854. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.F.; Muqaddas, M.; Sarwar, S. Biochemical mechanisms of etoposide; upshot of cell death. IJPSR 2015, 6(12), 4920.

- Dasari, S.; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. European Journal of Pharmacology 2014, 740, 364. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, V. Metabolism and mechanisms of action of bendamustine: Rationales for combination therapies. Seminars in Oncology 2002, 29(4), 4. [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.; Schwartz, H.R.; Honeywell, M.E.; Stewart, M.S.; Cruz-Gordillo, P.; Joyce, A.J.; Landry, B.D.; Lee, M.J. Drug antagonism and single-agent dominance result from differences in death kinetics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16(7), 791. [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, P.; De Proft, F.; Langenaeker, W. Conceptual Density Functional Theory. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103(5), 1793. [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functionaldispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem Phys. 2010, 132 (15), 154104. [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Hansen, A.; Brandenburg, J.G.; Bannwarth, C. Dispersion-Corrected Mean-Field Electronic Structure Methods. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5105. [CrossRef]

- Goerigk, L.; Hansen, A.; Bauer, C.; Ehrlich, S.; Najibi, A.; Grimme, S. A look at the density functional theory zoo withthe advanced GMTKN55 database for general main group thermochemistry, kinetics and noncovalent interactions. Phys.Chem.Chem.Phys. 2017, 19, 32184. [CrossRef]

- Raju, R.K.; Bengali, A.A.; Brothers, E.N. A unified set of experimental organometallic data used to evaluate modern theoretical methods. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 13766. [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. Journal of Chemical Physics 1993, 98, 5648. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Physical Review B 1988, 37, 785. [CrossRef]

- Makrlik, E.; Toman, P.; Vanura, P. A combined experimental and DFT study on the complexation of Mg2+ with beauvericin E. Structural Chemisty 2012, 23, 765. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.L.; Li, W.Z.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Xia, C. Novel guanidinium zwitterion and derived ionic liquids: physicochemical properties and DFT theoretical studies. Structural Chemistry 2011, 22, 1119. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, R. A.; Dunning, Jr. T. H.; Harrison, R. J. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 6796. [CrossRef]

- Dunning, Jr. T. H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007. [CrossRef]

- Papajak, E.; Truhlar, D.G. Efficient Diffuse Basis Sets for Density Functional Theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 597. [CrossRef]

- Hay, P. J.; Wadt, W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299. [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999. [CrossRef]

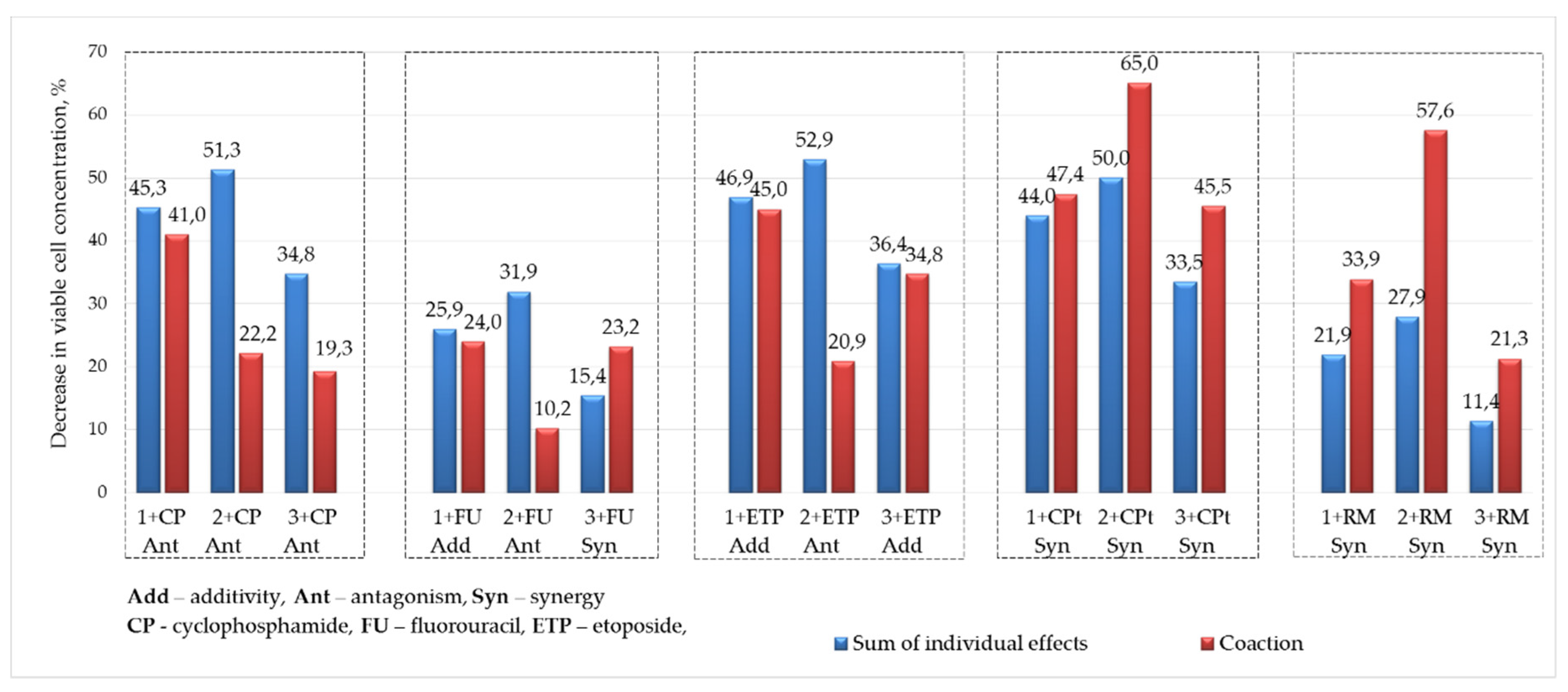

| Decrease in viable cell concentration, % | Compound, c = 200 µM (0,2% DMSO) | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Drug, c = 50 µM |

||||||

| Drug, c = 5µM | 18,7 | 24,7 | 8,2 | ||||||

| CP | 26,6 | 41,0 | Σ 45,3 | 22,2 | Σ 51,3 | 19,3 | Σ 34,8 | CF | 33,2 |

| (Ant) | (Ant) | (Ant) | |||||||

| FU | 7,2 | 24,0 | Σ 25,9 | 10,2 | Σ 31,9 | 23,2 | Σ 15,4 | FU | 42,3 |

| (Add) | (Ant) | (Syn) | |||||||

| ETP | 28,20 | 45,0 | Σ 46,9 | 20,9 | Σ 52,9 | 34,8 | Σ 36,4 | ET | 44,2 |

| (Add) | (Ant) | (Add) | |||||||

| CPt | 25,3 | 47,4 | Σ 44,0 | 65,0 | Σ 50,0 | 45,5 | Σ 33,5 | CP | 93,0 |

| (Syn) | (Syn) | (Syn) | |||||||

| RM | 3,2 | 33,9 | Σ 21,9 | 57,6 | Σ 27,9 | 21,3 | Σ 11,4 | RM | 35,7 |

| (Syn) | (Syn) | (Syn) | |||||||

| ∗Σ is the sum of the effects of a single compound and drug | |||||||||

| Binding energy, ΔG (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant, Ki | Residues Interactions | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | Electrostatic interactions |

Hydrophobic Bond | Pi-Sulfur | |||

| 1 | -9.3 | 152 nM | 0 | 0 | 6 (LEU215, PHE74, PHE219, ILE102, TRP103) | 0 |

| 2 | -9.9 | 55 nM | 3 (ASP212, HIS250) | 0 | 7 (PHE74, ILE102, LEU215, MET305, LEU186, CYS189) | 1 (CYS189) |

| 3 | -10.0 | 47 nM | 2 (ASP212, GLY216) | 3 (ARG44, GLU81, ASP212) | 6 (ARG169, LEU186, MET305, TRP103, ILE102) | 1 (CYS189) |

| FU | -5.1 | 183 μM | 8 (ASP212, GLN208, ASN220, GLY211, HIS190, CYS189) | 0 | 0 | 1 (CYS189) |

| FdUMP | -9.5 | 109 nM | 14 (ASN220, ASP212, GLN208, GLN211, CYS189, SER210, ARG44, ARG169, ARG170, ARG209) | 8 (ARG44, ARG169, ARG209, ARG107) | 0 | 1 (CYS189) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).