Submitted:

21 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Materials and Methods

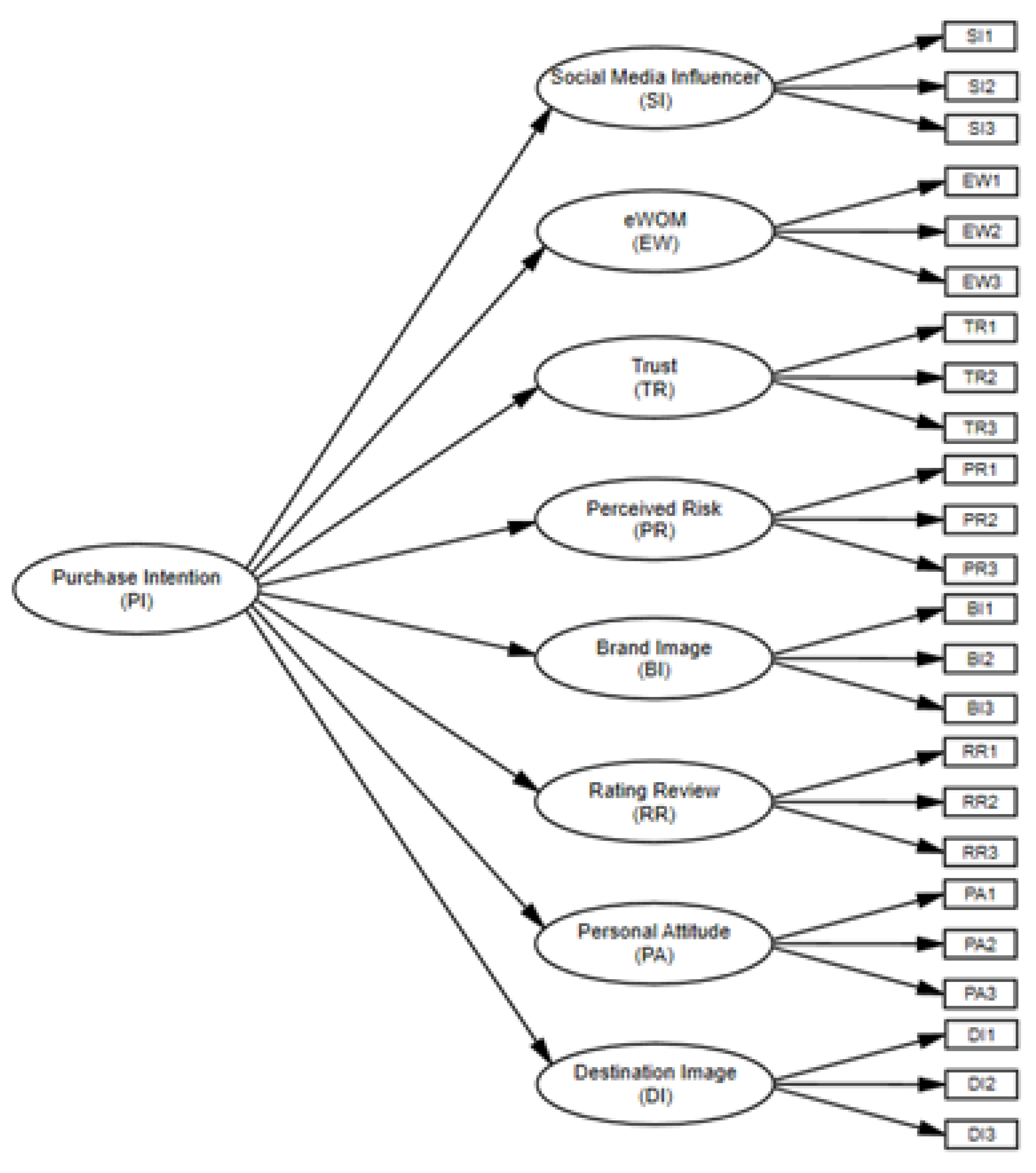

2.1. Dependent Variable

2.1.1. Purchase Intention

2.2. Independent Variable

2.2.1. Social Media Influencer

2.2.2. e-WOM

2.2.3. Trust

2.2.4. Perceived Risk

2.2.5. Brand Image

2.2.6. Rating Review

2.2.7. Personal Attitude

2.2.8. Destination Image

Methodology

| Phase 1: Qualitative research to seek expert consensus regarding purchase intention of overseas travel packages | |

| # | Step details |

| 1 | Determine problems by combining research and literature in the relevant field. |

| 2 | Determine the qualifications of a group of 21 experts. |

| 3 | A questionnaire was sent to 21 experts over 3 rounds using e-Delphi to gather their opinions. Round 1: Create an open-ended questionnaire Round 2: Create a questionnaire by extracting the analysed answers from the first round into variables. Round 3: To ensure the accuracy of the experts' responses in second round. |

| 4 | Summarized to obtain indicators based on the consensus measurement method of 21 experts using Fuzzy Delphi Theory. |

| Phase 2: Quantitative research was conducted using an online questionnaire | |

| 5 | Creating an online questionnaire from experts in step 1 was used to ask and collect information from a group of 800 people who had previously purchased overseas travel packages on social media. |

| 6 | To summarize the results of the quantitative research, the process involves collecting data, analysing them, and presenting the findings in a concise manner. |

3.1. Qualitative Research using the e-Fuzzy Delphi Technique

3.2. Quantitative Research with an Online Questionnaire

4. Results

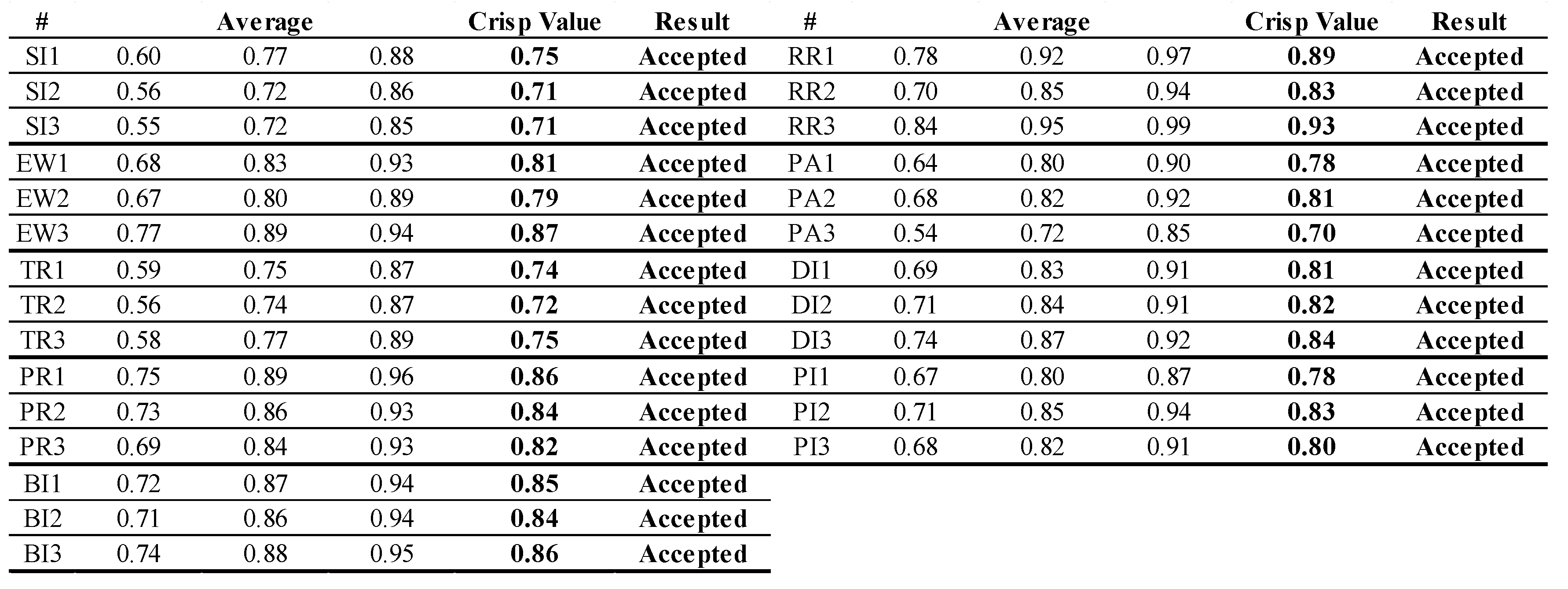

4.1. Expert consensus on Fuzzy Set Delphi

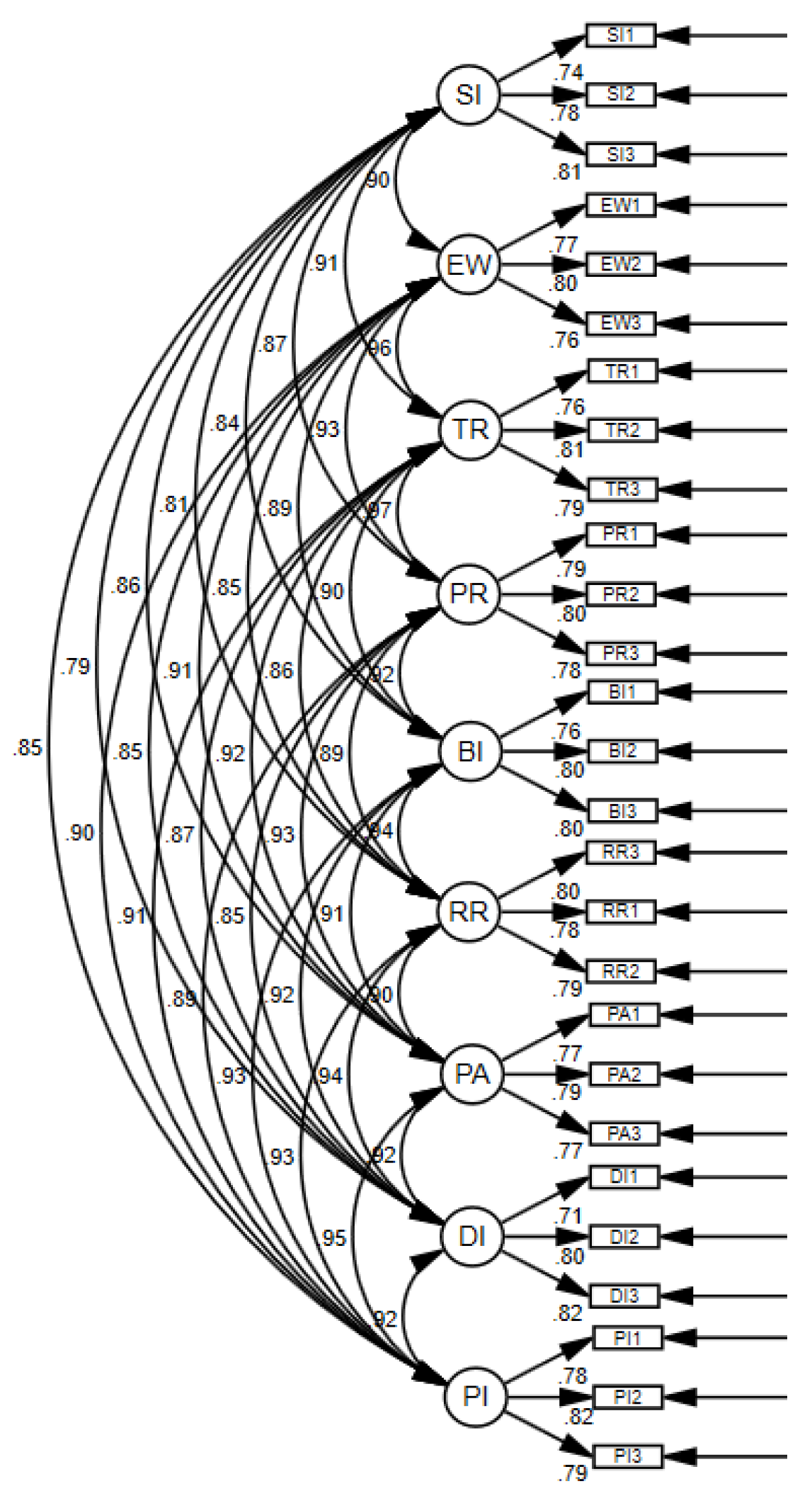

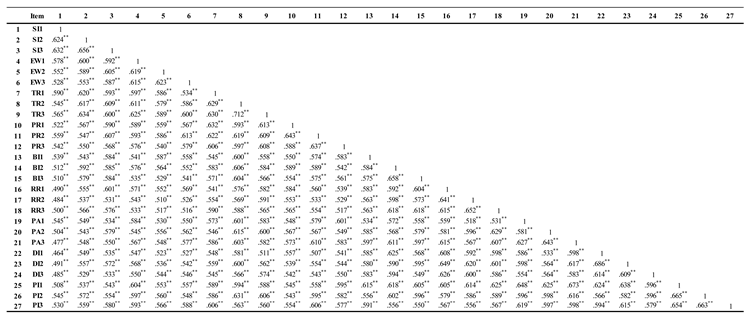

4.2.-First-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

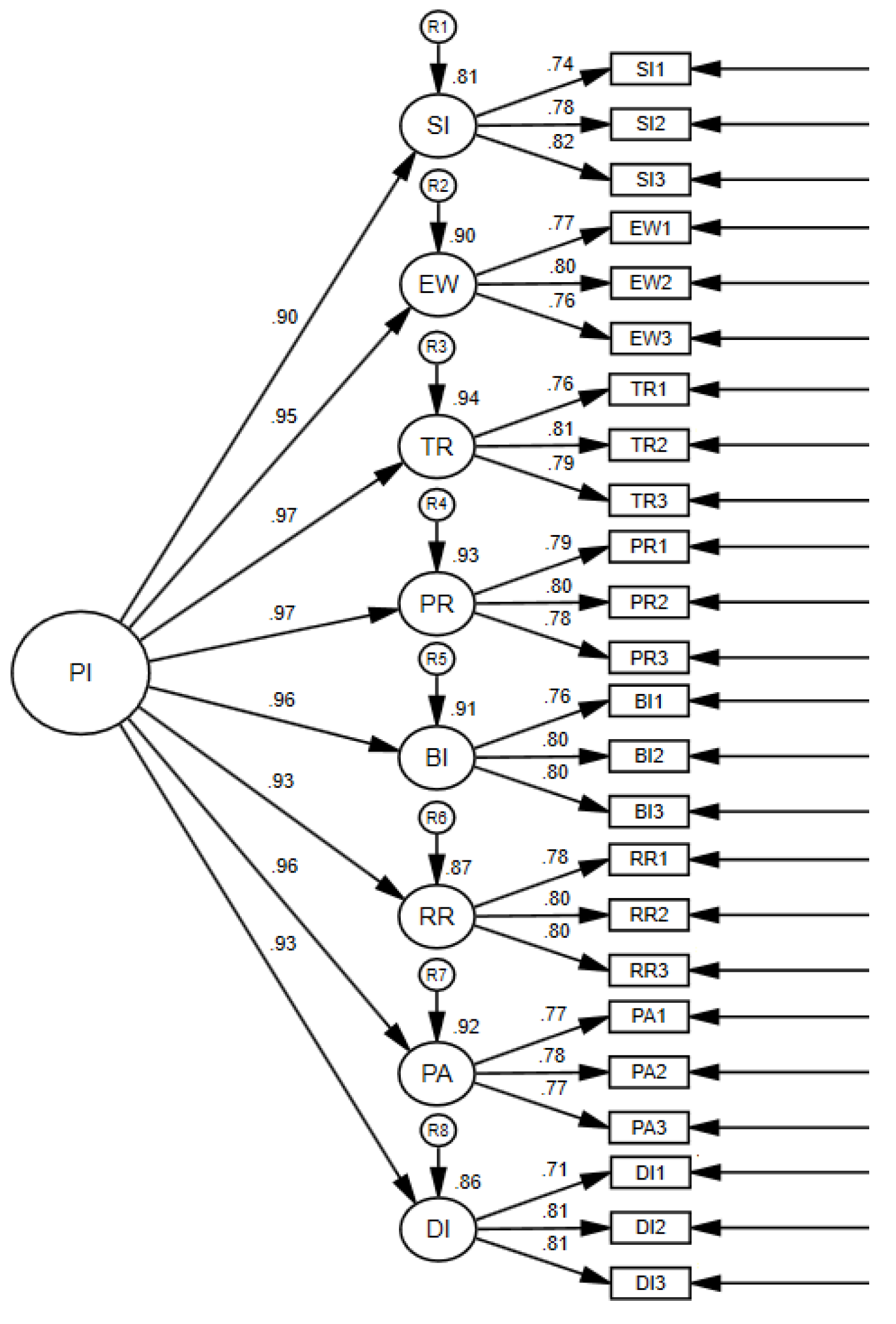

4.3. Second-Order Confirmatory Factor

5. Discussion

6. Suggestions

6.1. Suggestions for Applying the Research Results

6.2. Suggestions for future research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Twenty-year national strategy. (2023). Retrieved from https://www.bic.moe.go.th/images/stories/pdf/National_Strategy_Summary.pdf.

- Meriana, V. , & Kurniawati, N. (2023). The Impact of Covid-19 on Consumer Behavior in Choosing Staycation. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 4(1), 1-7.

- Lim, W. M. , & Lee, S. (2020). Determinants of airline customers' intentions to use low-cost carriers in Southeast Asia. Journal of Air Transport Management, 84, 101762.

- Department of Tourism, Thailand. (2023, April 15). List of licensed tourism businesses. Retrieved from https://www.dot.go.th/news/1/2.

- Everyday Marketing. (2022, August 17). The world's top 10 highest online shoppers 2022. Retrieved from https://www.everydaymarketing.co/top-10-worlds-highest-online-shoppers-2022/.

- Blognone. (2023, January 18). Social media user statistics Thailand 2023. Retrieved from https://www.blognone.com/node/132231.

- Sucisanjiwani, N. P. E., & Yudhistira, I. G. A. A. The role of social media as a media promotion for tourism products. Journal of Business on Hospitality and Tourism 2023, 9, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C. M., Wang, E. T., Fang, Y. H., & Huang, H. Y. Understanding customers' repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Information Systems Journal 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, S., Jayashree, S., Rezaei, S., Kasim, A., & Okumus, F. Attracting tourists to travel companies' websites: The structural relationship between website brand, personal value, shopping experience, perceived risk and purchase intention. Current Issues in Tourism 2018, 21, 616–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. C. , & Chen, H. C. (2017). The Fuzzy Set Delphi Method for Consensus Building and Decision Making. In C. C. Hsu & Y. L. Hu (Eds.), Fuzzy Decision Making: Theory, Methods, and Applications (pp. 1-26). Springer.

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lahap, J., Ramli, N. S., Said, N. M., Radzi, S. M., & Zain, R. A. A study of brand image towards customer's satisfaction in the Malaysian hotel industry. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2016, 224, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-K.; Wu, C.-E. An investigation of the relationships among destination familiarity, destination image and future visit intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.-H.; Wen, M.-J.; Huang, L.-C.; Wu, K.-L. Online hotel booking: The effects of brand image, price, trust and value on purchase intentions. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2015, 20, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidharta, R.B.F.I.; Sari, N.L.A.; Suwandha, W. PURCHASE INTENTION PADA PRODUK BANK SYARIAH DITINJAU DARI BRAND AWARENESS DAN BRAND IMAGE DENGAN TRUST SEBAGAI VARIABEL MEDIASI. Mix. J. Ilm. Manaj. 2018, 8, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, R. Impact of Perceived Risk on Consumer Purchase Intention towards Luxury Brands in Case of Pandemic: The Moderating Role of Fear. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2021, 10, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusniawati, V.; Prasetyo, A. PENGARUH E-WOM DAN BRAND IMAGE TERHADAP ONLINE PURCHASE INTENTION FASHION MUSLIM PADA MILENIAL SURABAYA. J. Èkon. Syariah Teor. dan Ter. 2022, 9, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, H.T.; Lestari, D. The Influence of Perceived Service Quality on Purchase Intention with Trust Plays a Mediating Role and Perceived Risk Plays a Moderating Role in Online Shopping. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2023, 23, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiyanti, N.; Mohaidin, Z. The Linking of Brand Personality, Trust, Attitude and Purchase Intention of Halal Cosmetic in Indonesia; A Conceptual Paper. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastiti, D.M.; Syavaranti, N.; Aruman, A.E. The Effect of Corporate Re-branding on Purchase Intention through The Brand Image of PT Pelita Air Service. J. Consum. Sci. 2021, 6, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alianto, C.; Semuel, H.; Wijaya, S. Website Quality and the Role of Travel Perceived Risk in Influencing Purchase Intention: A Study on Bali Tourism Board’s Official Website. 2nd International Conference on Business and Management of Technology (ICONBMT 2020). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndonesiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 275–282.

- Zarch, M.R.A.; Makian, S.; Najjarzadeh, M. Multidimensional interdisciplinary variables influencing tourist online purchasing intention at World Heritage City (City of Yazd, Iran). SN Bus. Econ. 2023, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2018, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U. (2017). Influencer marketing in travel and tourism. In Advances in Social Media for Travel, Tourism and Hospitality (pp. 147-156). Routledge.

- Xu, X., & Pratt, S. Social media influencers as endorsers to promote travel destinations: An application of self-congruence theory to the Chinese Generation Y. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2018, 35, 958–972. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanda, A.; Sumarwan, U.; Tinaprillia, N. THE EFFECT OF SOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCER ON BRAND IMAGE, SELF-CONCEPT, AND PURCHASE INTENTION. J. Consum. Sci. 2019, 4, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, D.R. Digital Marketing Strategy to Increase Brand Awareness and Customer Purchase Intention (Case Study: Ailesh Green Consulting). Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadlifatin, R.; Persada, S.F.; Munthe, J.H.; Ardiansyahmiraja, B.; Redi, A.A.N.P.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Belgiawan, P.F. UNDERSTANDING FACTORS INFLUENCING TRAVELER’S ADOPTION OF TRAVEL INFLUENCER ADVERTISING: AN INFORMATION ADOPTION MODEL APPROACH. Business: Theory Pr. 2022, 23, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyraff, M.A.; Hanafiah, M.H.M.; Zain, N.A.M.; Amir, A.F. The Influence of Instagram Influencers Source Credibility towards Domestic Travel Intention. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 12, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluri, A., Slevitch, L., & Larzelere, R. E. The Influence of Embedded Social Media Channels on Travelers' Gratifications, Satisfaction, and Purchase Intentions. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly 2015, 57, 250–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, V.S.Y.; Lo, J.C.Y.; Chiu, D.K.; Ho, K.K. Evaluating social media’s communication effectiveness on travel product promotion: Facebook for college students in Hong Kong. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2022, 51, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arta, I.G.; Yasa, N. THE ROLE OF PURCHASE INTENTION ON MEDIATING THE RELATIONSHIP OF E-WOM AND E-WOM CREDIBILITY TO PURCHASE DECISION. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Economic Sci. 2019, 86, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. A.S.D.Rathnayake; Lakshika, V. Impact Of Social Media Influencers’ Credibility on The Purchase Intention: Reference to The Beauty Industry. Asian J. Mark. Manag. 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, J.Y.; Prasasti, A. Brand Trust Capacity in Mediating Social Media Marketing Activities and Purchase Intention: A Case of A Local Brand That Go-Global During Pandemic. Indones. J. Bus. Entrep. 2023, 9, 81–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noufa, S.S.; Alexander, R.; Shanmuganathan, K. The Impact of Social Media Marketing Activities on Consumers Purchase Intention towards Handloom Clothes in Eastern Province, Sri Lanka. Wayamba J. Manag. 2022, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadli, T.; Hartono, V.C.; Proboyo, A. Mediation Role of Purchase Intention on The Relationship Between Social Media Marketing, Brand Image, and Brand Loyalty: A Case Study of J&T Express Indonesia. Petra Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2022, 5, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, A.A.; Rizan, M.; Febrilia, I. The Influence of Social Media Marketing and E-Wom on Purchase Decisions Through Purchase Intention: Study on Ready-to-Eat Food. J. Din. Manaj. DAN Bisnis 2022, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermawan, E.; Sanjaya, A.; Wediawati, T. The Effect of Social Media Marketing and Brand Awareness on Purchase Decisions through Purchase Intention in Kopiria. PINISI Discret. Rev. 2022, 6, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalesaran, C.J.J.; Mangantar, M.; Gunawan, E.M. THE EFFECT OF SOCIAL INFLUENCE AND PRODUCT ATTRIBUTES ON CUSTOMER PURCHASE INTENTION: A STUDY OF SECOND-HAND CLOTHES IN MANADO. J. EMBA : J. Ris. Èkon. Manajemen, Bisnis dan Akunt. 2022, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Khurshid, M.; Khan, M.H. Developing Trust through Social Media Influencers and Halal Tourism to Impact the Travel Decision of Travelers. J. Islam. Relig. Stud. 2022, 7, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafdinal, W.; Setyawati, L.; Rachman, A. Information adoption on social Media: How does it affect travel intention? Lessons from West Java. J. Tour. Sustain. 2022, 2, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, I.E.; Gabor, M.R. The Influence of Social Networks in Travel Decisions. ECONOMICS 2021, 9, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, F.E.V.S.; Tiarawati, M. The Effect of Social Media Influencer and Brand Image On Online Purchase Intention During The Covid-19 Pandemic. Ilomata Int. J. Manag. 2021, 2, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong, P.H. Impact of social media marketing and e-wom on purchase intention of consumer goods buyers. Laplage em Rev. 2021, 7, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodi, I.W.G.A.S.; Putra, B.N.K.; Prayoga, I.M.S.; Vipraprastha, T. Generasi Z di Bali: Lifestyle dan Social Media Influencer Mengubah Smoker Menjadi Vapor. Matrik : J. Manajemen, Strat. Bisnis dan Kewirausahaan 2021, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christi, M., & Junaedi, S. The Influence of Social Media on Consumer Purchase Intentions: Like Behavior as a Moderator. Journal of Social Science 2021, 2, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Natasha; Zunvindri; Abdurachman, E. The Effects of Social Media, Email Marketing, Website, Mobile Applications Towards Purchase Intention - Consumer Decisions. 2nd Southeast Asian Academic Forum on Sustainable Development (SEA-AFSID 2018). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndonesiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 10–12.

- Rathore, S. Analysing the Influence of User-Generated-Content (UGC) on Social Media Platforms in Travel Planning. Turizam 2020, 24, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, A.; Khadka, I. Social Media Marketing in Nepal: A Study of Travel Intermediaries of the Kathmandu Valley. PYC Nepal J. Manag. 2016, 9, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Ilkan, M. Impact of online WOM on destination trust and intention to travel: A medical tourism perspective. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Luo, X.; Riaz, M.U. On the Factors Influencing Green Purchase Intention: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S. B., & Jin, B. Predictors of Purchase Intention Toward Green Apparel Products. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 2017, 21, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Consumer familiarity, ambiguity tolerance, and purchase behavior toward remanufactured products: The implications for remanufacturers. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwidienawati, D.; Tjahjana, D.; Abdinagoro, S.B.; Gandasari, D. ; Munawaroh Customer review or influencer endorsement: which one influences purchase intention more? Heliyon 2020, 6, e05543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardar, A.; Manzoor, A.; Shaikh, K.A.; Ali, L. An Empirical Examination of the Impact of eWom Information on Young Consumers' Online Purchase Intention: Mediating Role of eWom Information Adoption. SAGE Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Consumers' purchase intentions in social commerce: the role of social psychological distance, perceived value, and perceived cognitive effort. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anubha Mediating role of attitude in halal cosmetics purchase intention: an ELM perspective. J. Islam. Mark. 2021, 14, 645–679. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fang, X.; Yan, F. The Purchase Intention for Agricultural Products of Regional Public Brands: Examining the Influences of Awareness, Perceived Quality, and Brand Trust. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunyai, J.; Yen-Nee, G.; Mohaidin, Z.; Razali, M.W.M. Malaysian Facebook Users Online Airline Tickets Purchase Intention: Antecedents and Outcome of eWOM. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 1370–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleo, & Sopiah. The Influence of Social Media Marketing Activities on Purchase Intention Through Brand Awareness. KnE Social Sciences 2021, 5, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Faisal, A.; Ekawanto, I. The role of Social Media Marketing in increasing Brand Awareness, Brand Image and Purchase Intention. Indones. Manag. Account. Res. 2022, 20, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahratu, S.; Hurriyati, R. Electronic Word of Mouth and Purchase Intention on Traveloka. 3rd Global Conference On Business, Management, and Entrepreneurship (GCBME 2018). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IndonesiaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 33–36.

- Lin, C.-H. , & Chen, H. (2022). A Study on the Influence of College Students' Perceived Anfu Sports Shoes E-Word of Mouth and Product Attitude on Purchase Intention. Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Economic Management and Model Engineering (ICEMME 2022), 233.

- Tulipa, D.; Muljani, N. The Country of Origin and Brand Image Effect on Purchase Intention of Smartphone in Surabaya - Indonesia. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALNefaie, M., Khan, S., & Muthaly, S. Consumers' Electronic Word of Mouth-Seeking Intentions on Social Media Sites Concerning Saudi Bloggers' YouTube Fashion Channels: An Eclectic Approach. International Journal of Business Forecasting and Marketing Intelligence 2019, 5, 238–257. [Google Scholar]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Chervany, N.L. What Trust Means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 6, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, M. What influences patients' willingness to choose in online health consultation? An empirical study with PLS-SEM. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 2423–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q. The effects of tourism e-commerce live streaming features on consumer purchase intention: The mediating roles of flow experience and trust. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 995129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zdemir, E., & Sonmezay, M. The Effect of the E-Commerce Companies Benevolence, Integrity and Competence Characteristics on Consumers Perceived Trust, Purchase Intention and Attitudinal Loyalty. Business and Economics Research Journal 2020, 11, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.-J.; Lee, C.-K.; Chung, N. Investigating the Role of Trust and Gender in Online Tourism Shopping in South Korea. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 37, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tislar, C.; Sterkenburg, J.; Zhang, W.; Jeon, M. How Emotions Influence Trust in Online Transactions Using New Technology. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2014, 58, 1531–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Zhao, B., & Chen, J. The Construction of Consumer Dynamic Trust in Cross-Border Online Shopping - Qualitative Research Based on Tmall Global, JD Worldwide and NetEase Koala. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science 2022, 5, 50–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, S.; Si, Y. The Evaluation Model of Transaction Trust in online Group-buying Based on Transaction History Information. 2016 Joint International Information Technology, Mechanical and Electronic Engineering Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Kao, D.T. The Impact of Transaction Trust on Consumers' Intentions to Adopt M-Commerce: A Cross-Cultural Investigation. CyberPsychology Behav. 2009, 12, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J., & Wang, C. (2008). Knowledge and Trust in E-Consumers' Online Shopping Behavior. 2008 International Symposium on Electronic Commerce and Security, 117-120.

- Sharif, M.S.; Shao, B.; Xiao, F.; Saif, M.K. The Impact of Psychological Factors on Consumers Trust in Adoption of M-Commerce. Int. Bus. Res. 2014, 7, p148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, S.-M.; Liao, H.-L.; Chen, H.-M. Factors That Affect Consumers’ Trust and Continuous Adoption of Online Financial Services. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, p108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R.; Staelin, R. A Model of Perceived Risk and Intended Risk-Handling Activity. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoj, B.; Korda, A.P.; Mumel, D. The relationships among perceived quality, perceived risk and perceived product value. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2004, 13, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Dyer, J.S.; Butler, J.C. Measures of Perceived Risk. Manag. Sci. 1999, 45, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.-W.; Miao, Y.-F.; Fang, Y.-H.; Lin, R.-Y. Establishing the Adoption of Electronic Word-of-Mouth through Consumers’ Perceived Credibility. Int. Bus. Res. 2013, 6, p58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. T., Brock, J. L., Shi, G. C., Chu, R., & Tseng, T. Perceived Benefits, Perceived Risk, and Trust. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2013, 25, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal, IJSREM. Execution and Emission Analysis of Supercharged IDI Diesel Engine Fuelled With Waste Cooking Oil Biodiesel. International Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management 2022, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bicen, P. (2014). Consumer Perceptions of Quality, Risk, and Value: A Conceptual Framework. Global Perspectives in Marketing for the 21st Century, 1-4.

- Lee, J. How eWOM Reduces Uncertainties in Decision-making Process: Using the Concept of Entropy in Information Theory. J. Soc. e-Business Stud. 2011, 16, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., & Ziobrowski, A. J. The Borrower's Perceived Risk in Mortgage Choice. Real Estate Economics 2015, 44, 676–705. [Google Scholar]

- Research on the Influence of Video Marketing of Social Media Influencers on Consumers Purchase Intention of Beauty Products---Taking YouTube as an Example. (2021). Academic Journal of Business & Management, 3(2), 1-8.

- Adnyani, D.A.M.E.S.; Sukaatmadja, I.P.G. PERAN PERCEIVED RISK DALAM MEMEDIASI PENGARUH PERCEIVED QUALITY TERHADAP PERCEIVED VALUE. E-Jurnal Manaj. Univ. Udayana 2019, 8, 7072–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, H.; Liu, Y. Disentangling the factors driving electronic word-of-mouth use through a configurational approach. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Qu, H.; Kim, Y.S. A study of the impact of personal innovativeness on online travel shopping behavior—A case study of Korean travelers. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. The Impact of Brand Image on Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 03, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amron, A. The Influence of Brand Image, Brand Trust, Product Quality, and Price on the Consumer's Buying Decision of MPV Cars. European Scientific Journal, ESJ 2018, 14, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchi, L.; Driesener, C.; Nenycz-Thiel, M. Brand image and brand loyalty: Do they show the same deviations from a common underlying pattern? J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbete, G.S.; Tanamal, R. Effect of Easiness, Service Quality, Price, Trust of Quality of Information, and Brand Image of Consumer Purchase Decision on Shopee Online Purchase. J. Inform. Univ. Pamulang 2020, 5, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelia, N.; Ekonomi, U.P.M.S.B.D. The Effect of Primary and Secondary Brand Association on Fast Food Industry. Kaji. Brand. Indones. 2022, 4, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa Ayu Abhinandati Prajna Pratisthita, Yudhistira, P. G. A., & Agustina, N. K. W. (2022). Effect of Brand Positioning, Brand Image, and Perceived Price on Consumer Repurchase Intention Low-Cost Carrier. Jurnal Manajemen Teori dan Terapan | Journal of Theory and Applied Management, 15(2), 246-258.

- Purnamabroto, D. F., Susanti, N., & Cempena, I. B. (2022). The Influence of Word of Mouth, Service Quality, and Brand Image on Consumer Loyalty Through Brand Trust in PT. Virama Karya (Persero) Surabaya. International Journal of Economics Business and Management Research, 6(8), 1-12.

- Aristana, I.K.G.A.; Yudhistira, P.G.A.; Sasmita, M.T. The Influence of Brand Image and Brand Trust on Consumer Loyalty (Case Study on Consumers of PT Citilink Indonesia Branch Office Denpasar). TRJ Tour. Res. J. 2022, 6, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketut, Y. I. (2018). The Role of Brand Image Mediating the Effect of Product Quality on Repurchase Intention. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 83(11), 165-172.

- Filieri, R. What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative influences in e-WOM. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B.; Chen, W. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.A.; Browning, V. The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Lee, T. Gender differences in consumers’ perception of online consumer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. 2010, 11, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, B.M.; McGuire, K.A. Effects of Price and User-Generated Content on Consumers’ Prepurchase Evaluations of Variably Priced Services. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 38, 562–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, H.; Xia, Q.; Gu, Q. How Social Interaction Affects Purchase Intention in Social Commerce: A Cultural Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezakati, H.; Amidi, A.; Jusoh, Y.Y.; Moghadas, S.; Aziz, Y.A.; Sohrabinezhadtalemi, R. Review of Social Media Potential on Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration in Tourism Industry. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Design is More Than Looks: Research on the Affordance of Review Components on Consumer Loyalty. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, ume 15, 3347–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Duarte, P. An integrative model of consumers' intentions to purchase travel online. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Chung, J.-E. Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Bai, B.; Stahura, K.A. The Marketing Effectiveness of Social Media in the Hotel Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 39, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Assessing the moderating effect of subjective norm on luxury purchase intention: a study of Gen Y consumers in India. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, B.A.; Hartmann, M.; Simons, J. Impacts from region-of-origin labeling on consumer product perception and purchasing intention – Causal relationships in a TPB based model. Food Qual. Preference 2015, 45, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Ladhari, R.; Nataraajan, R. Personality traits and complaining behaviors: A focus on Japanese consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, S.; Van Loo, E.J.; Bijttebier, J.; Vanhonacker, F.; Lauwers, L.; Tuyttens, F.A.; Verbeke, W. Determinants of consumer intention to purchase animal-friendly milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 8304–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai-zhong, H. E. , Cai, Y., Cai, L., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Conversation, Storytelling, or Consumer Interaction and Participation? The Impact of Brand-Owned Social Media Content Marketing on Consumers' Brand Perceptions and Attitudes. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(2), 267-296.

- Sarker, S. Influence of Personality in Buying Consumer Goods-A Comparative Study between Neo-Freudian Theories and Trait Theory Based on Khulna Region. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2013, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location Upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Ladhari, R.; Chiadmi, N.E. Destination personality and destination image. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 32, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.H.; Chen, K.; Yen, D.C.; Tran, T.P. A study of factors that contribute to online review helpfulness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, R.; Henkel, P.; Agrusa, W.; Agrusa, J.; Tanner, J. Thailand as a tourist destination: Perceptions of international visitors and Thai residents. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 11, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, S.A.; Kurniawati, M.; Nata, J.H. Ramadhani, S.A.; Kurniawati, M.; Nata, J.H. Effect of Destination Image and Subjective Norm toward Intention to Visit the World Best Halal Tourism Destination of Lombok Island in Indonesia. KnE Soc. Sci. 2020, 83–95–83–95. [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, P. The Delphi Method and its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. Futures 1971, 3, 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Chairaksa, S., & Pankham, S. The Influence of Trust and Perceived Risk on Purchase Intention of Overseas Travel Packages on Social Media in Thailand. Journal of Travel Research 2023, 62, 415–432. [Google Scholar]

- Robkob, P., & Pankham, S. Factors Influencing the Intention to Use Mobile Banking Services: A Case Study of Thai Consumers. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce 2023, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Meedach, T., & Lekcharoen, S. Fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS Approach for Supplier Selection: A Case Study in the Thai Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2345. [Google Scholar]

- Rangsoongnoen, S. (2011). Structural Equation Modeling: LISREL, PRELIS, SIMPLIS (2nd ed.). Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Press.

- Mudambi; Schuff Research Note: What Makes a Helpful Online Review? A Study of Customer Reviews on Amazon.com. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 185. [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R.; Raguseo, E.; Vitari, C. What moderates the influence of extremely negative ratings? The role of review and reviewer characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 77, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. What makes an online consumer review trustworthy? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Mitra, S.; Zhang, H. Research Note—When Do Consumers Value Positive vs. Negative Reviews? An Empirical Investigation of Confirmation Bias in Online Word of Mouth. Inf. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lehto, X.; Kandampully, J. The role of familiarity in consumer destination image formation. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Hosanagar, K.; Tan, Y. Do I Follow My Friends or the Crowd? Information Cascades in Online Movie Ratings. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 2241–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiripu, I.P.; Mishra, P.K.; Saini, A.; Biswal, A. Testing the impact of uncertainty reducing reviews in the prediction of cross domain social media pages ratings. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2022, 14, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistical Values | CMIN/DF | AGFI | GFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria for Consideration | ≤ 2.00 | 0.90 ≤ | 0.90 ≤ | 0.90 ≤ |

| Statistics Obtained | 1.632 | 0.928 | 0.945 | 0.985 |

| Consideration | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified |

| Statistical Values | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | RMR |

| Criteria for Consideration | 0.90≤ | 0.90 ≤ | ≤ 0.08 | ≤ 0.08 |

| Statistics Obtained | 0.981 | 0.985 | 0.032 | 0.013 |

| Consideration | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified |

|

| Factors | Statistical values | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | b | SE | P Value | ||

| Social Media Influencer (SI) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| SM1 : You purchase an overseas travel package on social media from a famous influencer. | 0.739 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.55 |

| SM2 : You purchase an overseas travel package on social media from a trending influencer. | 0.779 | 1.019 | 0.054 | *** | 0.61 |

| SM3 : You purchase an overseas travel package on social media based on the influencer's lifestyle. | 0.814 | 1.103 | 0.056 | *** | 0.66 |

| e-WOM (EW) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| EW1 : You always recommend acquaintances to buy overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.772 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.60 |

| EW2 : You always express positive opinions about your overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.797 | 0.987 | 0.047 | *** | 0.64 |

| EW3 : You always tell about your good experiences regarding overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.763 | 0.913 | 0.046 | *** | 0.58 |

| Trust (TR) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| TR1 : You trust buying overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.763 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.58 |

| TR2 : You trust the quality of overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.812 | 1.064 | 0.050 | *** | 0.66 |

| TR3 : You trust in the detailed information of overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.785 | 1.008 | 0.049 | *** | 0.62 |

| Perceived Risk (PR) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| PR1 : You acknowledge the risks of purchasing overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.787 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.62 |

| PR2 : You are aware of the risks of purchasing overseas travel packages on social media regarding the protection of personal information from being leaked. | 0.798 | 0.938 | 0.043 | *** | 0.64 |

| PR3 : You recognize the risk of purchasing overseas travel packages on social media that the travel program will not be as specified by the travel company. | 0.784 | 0.914 | 0.043 | *** | 0.61 |

| Brand Image (BI) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| BI1 : You think that companies that sell overseas travel packages on social media have easily recognizable logos. | 0.760 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.58 |

| B2 : You think that companies selling overseas travel packages on social media have a good reputation. | 0.796 | 1.000 | 0.049 | *** | 0.63 |

| BI3 : You think that companies selling overseas travel packages on social media are widely known. | 0.801 | 1.014 | 0.049 | *** | 0.64 |

| Rating Review (RR) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| RR1 : You purchase a overseas travel package on social media based on the level of review ratings. | 0.798 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.64 |

| RR2 : You bought an overseas travel package on social media after reading a travel review that had fun content. | 0.780 | 1.063 | 0.050 | *** | 0.61 |

| RR3 : You purchased an overseas travel package on social media based on informative travel reviews. | 0.794 | 1.040 | 0.048 | *** | 0.63 |

| Personal Attitude (PA) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| PA1 : You like buying overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.773 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.60 |

| PA2 : You feel pleasure in purchasing overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.787 | 0.972 | 0.047 | *** | 0.62 |

| PA3 : You feel more satisfied purchasing overseas travel packages on social media than purchasing them directly through tour operators. | 0.766 | 0.949 | 0.047 | *** | 0.59 |

| Destination Image (DI) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| DI1 : You purchase overseas travel packages on social media based on the reputation and popularity of the tourist destination. | 0.711 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.51 |

| DI2 : You purchase overseas travel packages on social media based on the unique culture of the tourist destination. | 0.803 | 1.046 | 0.055 | *** | 0.65 |

| DI3 : You buy overseas travel packages on social media based on the beauty of the tourist destinations. | 0.820 | 1.122 | 0.058 | *** | 0.67 |

| Purchase Intention (PI) | - | 1.000 | - | - | |

| PI1 : When you think of buying a overseas travel package. You will think of buying on social media as the first option. | 0.784 | 1.000 | - | - | 0.61 |

| PI2 : You intend to purchase overseas travel packages on social media in the future. | 0.825 | 1.006 | 0.045 | *** | 0.68 |

| PI3 : You intend to continually purchase overseas travel packages on social media. | 0.789 | 0.985 | 0.046 | *** | 0.62 |

| Statistical Values | CMIN/DF | AGFI | GFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria for Consideration | ≤ 3.00 | 0.90 ≤ | 0.90 ≤ | 0.90 ≤ |

| Statistics Obtained | 2.049 | 0.918 | 0.933 | 0.975 |

| Consideration | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified |

| Statistical Values | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | RMR |

| Criteria for Consideration | 0.90 ≤ | 0.90 ≤ | ≤ 0.08 | ≤ 0.08 |

| Statistics Obtained | 0.972 | 0.975 | 0.041 | 0.018 |

| Consideration | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified | Qualified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).