Submitted:

23 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Clinical Data

2.2. Laboratory Tests

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Blood – Based Biomarkers and Treatment Response

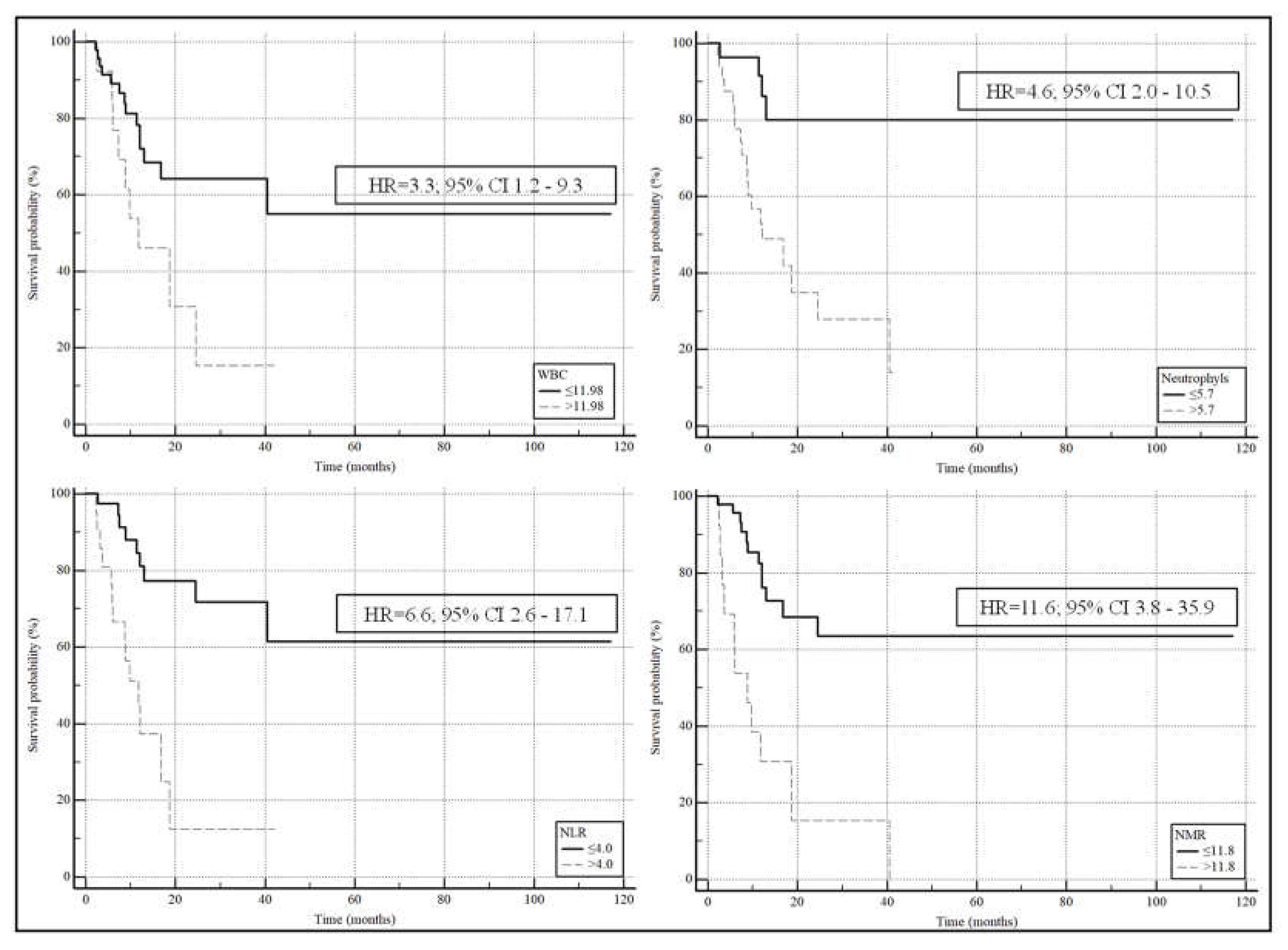

3.2. Blood – Based Biomarkers and Overall Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Available on https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/cancers/15-trachea-bronchus-and-lung-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed on 08/05/2024.

- Colombino, M.; Paliogiannis, P.; Cossu, A.; Santeufemia, D.A.; Sardinian Lung Cancer (SLC) Study Group; Sini, M. C.; Casula, M.; Palomba, G.; Manca, A.; Pisano, M.; et al. EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK, and cMET genetic alterations in 1440 Sardinian patients with lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Pulm Med 2019, 19, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Koning, H.J.; van der Aalst, C.M.; de Jong, P.A.; Scholten, E.T.; Nackaerts, K.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Lammers, J.J.; Weenink, C.; Yousaf-Khan, U.; Horeweg, N.; et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available on https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. Accessed on 08/05/2024.

- Hendriks, L.E.; Kerr, K.M.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.S.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Solomon, B.J.; et al. Non-oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2023, 34, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzu, C.; Canova, S.; Paliogiannis, P.; Lobrano, R.; Sala, L.; Cortinovis, D.L.; Colonese, F. Duration of immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer survivors: A lifelong commitment? Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Rashid, S.; Al-Bozom, I.A. PD-L1 immunostaining: what pathologists need to know. Diagn Pathol 2021, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, B.; Pau, M.C.; Zinellu, E.; Mangoni, A.A.; Paliogiannis, P.; Pirina, P.; Fois, A.G.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A. Association between red blood cell distribution width and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Li, J.; Ma, X.; Pan, L. The predictive value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Respir Med 2020, 14, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaan, H.; Kalami, N.; Ghasempour Alamdari, M.; Emami Alorizy, S.M.; Ghaedi, A.; Bazrgar, A.; Khanzadeh, M.; Lucke-Wold, B.; Khanzadeh, S. Diagnostic value of the neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in discrimination between tuberculosis and bacterial community acquired pneumonia: A meta-analysis. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 2023, 33, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios as prognostic biomarkers in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Future Oncol 2023, 19, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ye, S. Platelet-lymphocyte ratio is a prognostic marker in small cell lung cancer-A systemic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2023, 12, 1086742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzu, C.; Cortinovis, D.L.; Colonese, F.; Canova, S.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A.; Paliogiannis, P. Blood cell count indexes as predictors of outcomes in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with Nivolumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2018, 67, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginesu, G.C.; Paliogiannis, P.; Feo, C.F.; Cossu, M.L.; Scanu, A.M.; Fancellu, A.; Fois, A.G.; Zinellu, A.; Perra, T.; Veneroni, S.; et al. Inflammatory indexes as predictive biomarkers of postoperative complications in oncological thoracic surgery. Curr Oncol 2022, 29, 3425–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliogiannis, P.; Ginesu, G.C.; Tanda, C.; Feo, C.F.; Fancellu, A.; Fois, A.G.; Mangoni, A.A.; Sotgia, S.; Carru, C.; Porcu, A, et al. Inflammatory cell indexes as preoperative predictors of hospital stay in open elective thoracic surgery. ANZ J Surg 2018, 88, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.; Uchino, J.; Yokoi, T.; Kijima, T.; Goto, Y.; Suga, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Nakamura, R.; Morimoto, K.; Nakao, A.; et al. Prognostic Nutritional Index and Lung Immune Prognostic Index as prognostic predictors for combination therapies of immune checkpoint inhibitors and cytotoxic anticancer chemotherapy for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prelaj, A.; Ferrara, R.; Rebuzzi, S.E.; Proto, C.; Signorelli, D.; Galli, G.; De Toma, A.; Randon, G.; Pagani, F.; Viscardi, G.; et al. EPSILoN: A prognostic score for immunotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A validation cohort. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punekar, S.R.; Shum, E.; Grello, C.M.; Lau, S.C.; Velcheti, V. Immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: Past, present, and future directions. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 877594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 2078–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Luft, A.; Vicente, D.; Tafreshi, A.; Gümüş, M.; Mazières, J.; Hermes, B.; Çay Şenler, F.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadgeel, S.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Speranza, G.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; Dómine, M.; Hui, R.; Hochmair, M.J.; Clingan, P.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Updated analysis from KEYNOTE-189: Pembrolizumab or placebo plus Pemetrexed and Platinum for previously untreated metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Cobo, M.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Menezes, J.; Richardet, E.; Bennouna, J.; Felip, E.; Juan-Vidal, O.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab with two cycles of chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone (four cycles) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: CheckMate 9LA 2-year update. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Ohe, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Hayashi, H.; Fukuhara, T.; Sato, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Hotta, K.; Sugawara, S.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: 5-year outcomes in Japanese patients from CheckMate 227 Part 1. Int J Clin Oncol 2023, 28, 1354–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiriu, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Nagano, T.; Hazama, D.; Sekiya, R.; Katsurada, M.; Tamura, D.; Tachihara, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Nishimura, Y. The time-series behavior of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is useful as a predictive marker in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0193018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, G.T.; Weiner, L.M.; Atkins, M.B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2016, 17, e542–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawinkels, L.J.; Zuidwijk, K.; Verspaget, H.W.; de Jonge-Muller, E.S.; van Duijn, W.; Ferreira, V.; Fontijn, R.D.; David, G.; Hommes, D.W.; Lamers, C.B.; et al. VEGF release by MMP-9 mediated heparan sulphate cleavage induces colorectal cancer angiogenesis. Eur J Cancer 2008, 44, 1904–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhab, L.J.B.; Saber-Ayad, M.M.; Al-Hakm, R.; Nair, V.A.; Paliogiannis, P.; Pintus, G.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M. Chronic inflammation and cancer: The role of endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation. Curr Pharm Des 2021, 27, 2156–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmied, L.; Höglund, P.; Meinke, S. Platelet-mediated protection of cancer cells from immune surveillance - possible implications for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 640578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Yue, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, X.; Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; et al. Correlations between peripheral blood biomarkers and clinical outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients who received immunotherapy-based treatments. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2021, 10, 4477–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Xia, L.; Gao, P.; et al. The predictive value of inflammatory biomarkers for major pathological response in non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy and its association with the immune-related tumor microenvironment: a multi-center study. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2023, 72, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Global cohort (n=62) |

Responders (n=47) |

Non-responders (n=15) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 68.5 (62.0-74.0) | 66.0 (61.3-72.8) | 71.0 (64.8-75.0) | 0.17 |

| Gender (M/F) | 45/17 | 34/13 | 11/4 | 0.94 |

| Smoking status, n (no/former/yes) | 3/45/11 | 3/33/9 | 0/12/2 | 0.51 |

| Histological type, n (ADK/SQ) | 53/9 | 41/6 | 12/3 | 0.49 |

| PDL1, n (yes/no) | 30/30 | 23/22 | 7/8 | 0.77 |

| Stage T, n (T1/T2/T3/T4) | 4/2/3/53 | 4/2/2/39 | 0/0/1/14 | 0.53 |

| Stage N, n (N0/N1/N2/N3) | 3/9/11/38 | 3/9/8/26 | 0/0/3/12 | 0.18 |

| Deceased, n (yes/no) | 23/37 | 10/35 | 13/2 | <0.0001 |

| Overall survival, (months) | 12.1 (7.4-24.3) | 14.5 (9.1-31.9) | 7.5 (4.2-11.2) | 0.0015 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.3±1.7 | 12.6±1.7 | 11.9±1.8 | 0.47 |

| RDW, (%) | 14.7 (13.8-15.8) | 14.7 (13.4-15.8) | 14.8 (14.1-15.6) | 0.53 |

| WBC, n (×109 L) | 8.86 (7.40-11.15) | 8.74 (6.91-10.72) | 8.96 (7.96-13.73) | 0.29 |

| Neutrophils, n (×109 L) | 6.00 (4.10-7.60) | 5.62 (3.80-7.37) | 6.40 (5.59-11.95) | 0.074 |

| Lymphocytes, n (×109 L) | 1.70 (1.30-2.20) | 1.80 (1.40-2.44) | 1.40 (1.10-1.98) | 0.10 |

| Monocytes, n (×109 L) | 0.60 (0.50-0.80) | 0.60 (0.50-0.80) | 0.60 (0.50-0.80) | 0.55 |

| Platelets, n (×109 L) | 287 (253-355) | 287 (254-362) | 293 (247-349) | 0.91 |

| NLR | 3.45 (2.18-5.47) | 3.31 (2.15-4.12) | 5.36 (2.78-10.82) | 0.019 |

| NMR | 9.75 (7.60-11.80) | 9.20 (7.45-11.20) | 14.00 (8.82-21.20) | 0.013 |

| MLR | 0.33 (0.23-0.53) | 0.33 (0.23-0.51) | 0.40 (0.21-0.55) | 0.67 |

| PLR | 169 (118-246) | 163 (114-244)) | 209 (131-248) | 0.17 |

| SII | 985 (624-1838) | 945 (552-1373) | 1395 (929-3334) | 0.025 |

| AISI | 543 (277-1072) | 487 (273-955) | 837 (357-1524) | 0.20 |

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.0424 | 0.9735 to 1.1162 | 0.23 |

| Gender (M/F) | 0.9510 | 0.2564 to 3.5275 | 0.94 |

| Smoking status, n (no/former/yes) | 1.0444 | 0.2906 to 3.7533 | 0.95 |

| Histological type, n (ADK/SQ) | 1.7083 | 0.3707 to 7.8732 | 0.49 |

| PD-L1, n (yes/no) | 1.1948 | 0.3706 to 3.8525 | 0.77 |

| Stage T, n (T1/T2/T3/T4) | 2.3437 | 0.5289 to 10.3860 | 0.26 |

| Stage N, n (N0/N1/N2/N3) | 2.7685 | 0.9610 to 7.9752 | 0.06 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 0.7851 | 0.5462 to 1.1286 | 0.19 |

| RDW, (%) | 1.1248 | 0.8202 to 1.5426 | 0.47 |

| WBC, n | 1.0731 | 0.9289 to 1.2395 | 0.34 |

| Neutrophils, n | 1.1335 | 0.9724 to 1.3213 | 0.11 |

| Lymphocytes, n | 0.4280 | 0.1620 to 1.1309 | 0.09 |

| Monocytes, n | 0.2614 | 0.0253 to 2.7002 | 0.26 |

| Platelets, n | 0.9987 | 0.9939 to 1.0036 | 0.60 |

| NLR | 1.2561 | 1.0519 to 1.4998 | 0.012 |

| NMR | 1.1410 | 1.0121 to 1.2864 | 0.03 |

| MLR | 1.8104 | 0.1299 to 25.2236 | 0.66 |

| PLR | 1.0018 | 0.9983 to 1.0053 | 0.32 |

| SII | 1.0002 | 0.9999 to 1.0005 | 0.27 |

| AISI | 1.0000 | 0.9997 to 1.0003 | 0.84 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| NLR | 1.3210 | 1.0648 to 1.6387 | 0.01 | 1.8300 | 1.1236 to 2.9806 | 0.02 |

| NMR | 1.1585 | 1.0070 to 1.3328 | 0.04 | 1.1698 | 1.0019 to 1.3657 | 0.047 |

| Global cohort (n=60) |

Survivors (n=37) |

Non-survivors (n=23) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 68.0 (62.0-73.5) | 66.0 (62.0-73.3) | 70.0 (61.5-74.5) | 0.37 |

| Gender (M/F) | 44/16 | 27/10 | 17/6 | 0.94 |

| Smoking status, n (no/former/yes) | 3/43/11 | 3/25/7 | 0/18/4 | 0.35 |

| Histological type, n (ADK/SQ) | 51/9 | 33/4 | 18/5 | 0.25 |

| PD-L1, n (yes/no) | 29/29 | 18/17 | 11/12 | 0.79 |

| Stage T, n (T1/T2/T3/T4) | 4/2/3/51 | 4/2/2/29 | 0/0/1/22 | 0.23 |

| Stage N, n (N0/N1/N2/N3) | 3/8/10/38 | 3/7/5/21 | 0/1/5/17 | 0.15 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.3±1.7 | 12.6±1.8 | 12.2±1.7 | 0.43 |

| RDW, (%) | 14.6 (13.6-15.7) | 14.4 (13.3-15.8) | 14.8 (14.1-15.6) | 0.51 |

| WBC, n (×109 L) | 8.94 (7.41-11.53) | 8.26 (6.36-9.92) | 9.69 (7.97-14.03) | 0.026 |

| Neutrophils, n (×109 L) | 6.00 (4.10-7.81) | 5.30 (3.48-7.03) | 7.00 (6.00-11.95) | 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes, n (×109 L) | 1.70 (1.30-2.23) | 1.80 (1.40-2.50) | 1.50 (1.13-2.00) | 0.14 |

| Monocytes, n (×109 L) | 0.60 (0.50-0.80) | 0.60 (0.50-0.80) | 0.80 (0.50-0.80) | 0.32 |

| Platelets, n (×109 L) | 287 (252-353) | 270 (238-336) | 314 (281-407) | 0.052 |

| NLR | 3.45 (2.20-5.42) | 2.94 (1.92-3.88) | 4.56 (3.07-9.49) | 0.012 |

| NMR | 9.60 (7.60-11.75) | 9.00 (7.08-11.05) | 10.40 (8.80-18.18) | 0.007 |

| MLR | 0.34 (0.24-0.54) | 0.33 (0.24-0.41) | 0.43 (0.24-0.58) | 0.16 |

| PLR | 169 (119-246) | 136 (107-201) | 220 (145-273) | 0.016 |

| SII | 985 (626-1709) | 849 (488-1081) | 1493 (1000-2578) | 0.0004 |

| AISI | 594 (279-1168) | 351 (256-794) | 1016 (470-1836) | 0.006 |

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.0268 | 0.9706 to 1.0863 | 0.36 |

| Gender (M/F) | 0.9529 | 0.2928 to 3.1016 | 0.94 |

| Smoking status, n (no/former/yes) | 1.3482 | 0.4379 to 4.1505 | 0.60 |

| Histological type, n (ADK/SQ) | 2.2917 | 0.5458 to 9.6219 | 0.26 |

| PD-L1, n (yes/no) | 1.1551 | 0.4030 to 3.3107 | 0.79 |

| Stage T, n (T1/T2/T3/T4) | 3.4877 | 0.6931 to 17.5496 | 0.13 |

| Stage N, n (N0/N1/N2/N3) | 2.0009 | 0.9653 to 4.1472 | 0.06 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 0.8804 | 0.6468 to 1.1982 | 0.42 |

| RDW, (%) | 1.1224 | 0.8410 to 1.4978 | 0.43 |

| WBC, n | 1.2202 | 1.0339 to 1.4400 | 0.019 |

| Neutrophils, n | 1.2916 | 1.0692 to 1.5604 | 0.008 |

| Lymphocytes, n | 0.5819 | 0.2719 to 1.2454 | 0.16 |

| Monocytes, n | 1.7055 | 0.2449 to 11.8784 | 0.59 |

| Platelets, n | 1.0014 | 0.9977 to 1.0052 | 0.45 |

| NLR | 1.3601 | 1.0949 to 1.6896 | 0.005 |

| NMR | 1.2159 | 1.0396 to 1.4221 | 0.015 |

| MLR | 5.6613 | 0.4789 to 66.9198 | 0.17 |

| PLR | 1.0023 | 0.9988 to 1.0058 | 0.19 |

| SII | 1.0004 | 1.0000 to 1.0007 | 0.054 |

| AISI | 1.0002 | 0.9999 to 1.0005 | 0.20 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | p-value | aOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| WBC | 1.2596 | 1.0458 to 1.5171 | 0.015 | 1.2475 | 1.0317 to 1.5084 | 0.023 |

| Neutrophils | 1.3112 | 1.0698 to 1.6071 | 0.009 | 1.2990 | 1.0527 to 1.6028 | 0.015 |

| NLR | 1.3498 | 1.0758 to 1.6936 | 0.01 | 1.3489 | 1.0632 to 1.7114 | 0.014 |

| NMR | 1.2502 | 1.0311 to 1.5158 | 0.02 | 1.5685 | 1.0901 to 2.2568 | 0.015 |

| AUC | 95% CI | p-value | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 0.672 | 0.539 to 0.788 | 0.017 | >11.98 | 39 | 89 |

| Neutrophyls | 0.746 | 0.617 to 0.849 | 0.0001 | >5.7 | 83 | 65 |

| NLR | 0.749 | 0.620 to 0.852 | 0.0001 | >4.0 | 61 | 81 |

| NMR | 0.707 | 0.576 to 0.818 | 0.0038 | >11.8 | 48 | 92 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aHR | 95% CI | p-value | aHR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| WBC | 1.1966 | 1.0443 to 1.3711 | 0.01 | 1.1191 | 0.9944 to 1.2594 | 0.062 |

| Neutrophils | 1.2297 | 1.0745 to 1.4074 | 0.003 | 1.1480 | 1.0162 to 1.2970 | 0.027 |

| NLR | 1.3016 | 1.1267 to 1.5037 | 0.003 | 1.2141 | 1.0666 to 1.3819 | 0.003 |

| NMR | 1.0217 | 1.0056 to 1.0380 | 0.008 | 1.0174 | 1.0027 to 1.0324 | 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).