1. Introduction

One of the primary objectives in sports training, physical preparation, and physiotherapy is to develop strategies, models, training guidelines, and optimal periodization to enhance physical condition and sports performance. [

1,

2]. The existing literature mentions the need to develop absolute stenght and vertical jump in different sports modalities; Possible interventions with specific physical stimuli with a variety of positive and negative results are currently being discussed in the search to improve the aforementioned capabilities, the most studied focus on addressing muscle deficits, muscle strengthening, preventing injuries and return to play; the last-mentioned area studied mainly in football [

3,

4].

Given the physical demands of each sport, strength and conditioning training programs are specifically designed [

5], understanding that numerous sports have specific gestures that include jumps, kicks, sprints, and changes of direction. It should be considered that both strength training and other physical abilities will be appropriate for the programming and training of the elite athlete; In the same way, the evidence emphasizes good planning such as the duration and periodization of these training, finding variants in the time of completion of the motor task, the way of applying them, and even whether it is appropriate to physically stimulate, considering the biological principles of training required for optimal preparation[

6,

7,

8].

Fast and sudden movements are integral to the daily training of both high-performance and recreational athletes. Several authors have been studying, and they emphasize the need to intervene in muscle groups with greater tension, eccentric load, level of activity, and injury levels after high sporting demand [

9,

10,

11]. One of these muscle groups is the hamstrings, for which several programs have been generated that seek to intervene with a specialized or specific protocol, among the most outstanding are: Nordic exercise, the FIFA 11+ program, and Core stability exercises, each of these applied over a period of time and with positive results at a clinical and sporting level [

12,

13,

14].

Eccentric activation induces greater muscle tension, strengthening the muscle, reducing injury incidence, increasing fascicle length, and minimizing lower limb asymmetries. [

15]. Research describes that the greater risk of suffering a hamstring injury is related to a greater age range in athletes, or in athletes who have a previous hamstring injury [

16,

17,

18].

Hamstring injuries primarily occur when players perform running training, this muscle group is susceptible to injuries due to its anatomical arrangement and its correlation of strength with the quadriceps, considering its biomechanical functioning in which its mechanism of action on the joints (knee and hip) occur together (Lombard's paradox), with opposite effects on the length of the hamstrings and quadriceps generating a greater risk of injury; Finally, adding to the functions of this muscle group, the function in deceleration when walking, running and making sudden changes in direction at high speed should be highlighted, although further research is recommended in terms of correlation [

19,

20].

This study focuses on analyzing several sports modalities of which we highlight the need to carry out studies and analyzes that can help to understand and improve the bibliography base for future research, are described below:

In Taekwondo the trained skills depend on kicking techniques, so the vast majority of injuries are located in the lower limbs [

21], and to improve and prevent these injuries, it is recommended to carry out an adequate dosage program of physical exercises, which includes as one of the objectives the improvement of strength in the lower limbs [

22].

In athletics, however, the volume and strength of the hamstrings are related to an improvement in sprint power [

23], it should also be noted that strength training in the lower limbs turns out to be long-term, for a program to be effective in reducing the risk of injuries [

24].

In climbers, physical characteristics are predominantly marked in the upper limbs; however, with a lower prevalence in the lower limb, practitioners of this sport are required to have good hip flexibility, high aerobic resistance, strength in the hamstrings, back and good vertical jump ability, to execute the impulses that could depend on and vary depending on the sporting subdiscipline [

25,

26].

In basketball, it is known that maximum eccentric strength is an important factor for rapid and successful deceleration, and according to a cross-sectional study analyzed the athletes with higher levels of strength in Nordic exercise had a greater skill for deceleration and jump [

27].

Finally, in cycling, repetitive knee movement requires simultaneous activation of the hamstrings and quadriceps in an agonist and antagonist manner, making it necessary to focus on prevention and strengthening of the lower area, involving strength phases in the entire lower limb to prevent muscle imbalance situations [

28].

Musculoskeletal damage to the hamstrings is common in different sports modalities [

16], highly studied in footballers according to current reference reviews [

17,

29], although there is insufficient information on the incidence of these injuries in other sports modalities. [

30,

31].

Currently, Nordic exercises are part of physiotherapy and training treatments, to gain strength and prevent hamstring injuries in athletes, in its application, great benefits and recommendations have been found [

8,

32,

33], despite being a training considered "Gold Standard", its effectiveness in other sports modalities other than football is not clear.

This study analyzes the effects of Nordic walking exercises on the hamstrings and their relationship with absolute strength and vertical jump variables, gaining an understanding of the exercise's effect based on the demands of soccer, athletics/sprinting, basketball, sport climbing, cycling, and taekwondo.

2. Materials and Methods

It is a quasi-experimental pre- and post-test study[

34], to evaluate the effects of stimuli with Nordic exercises on the vertical jump and absolute strength of athletes. The Nordic-type physical stimuli were distributed in an intervention of 9 total weeks, which includes 1 week of initial evaluation (pre-test), 7 weeks of training, and 1 week of final evaluation (post-test).

2.1. Participants

A call was made during 2022 to the gyms and federations of the different sports modalities mentioned, which met the following inclusion criteria: a) Athletes who are registered in federations, gyms and sports clubs in the Imbabura province, Republic of Ecuador ; b) That they have systematic experience in the sports discipline for at least 12 months; c) That they have an age range between 16 and 28 years; d) Athletes or legal representatives who sign the informed consent; e) That they are not in the competitive stage according to their training macrocycle for each sporting modality; f) That they do not present pathologies, respiratory or musculoskeletal injuries; g) They have not completed a Nordic or similar protocol for at least 6 months prior to the intervention; h) They have a similar vertical jump and absolute strength index in the lower limbs.

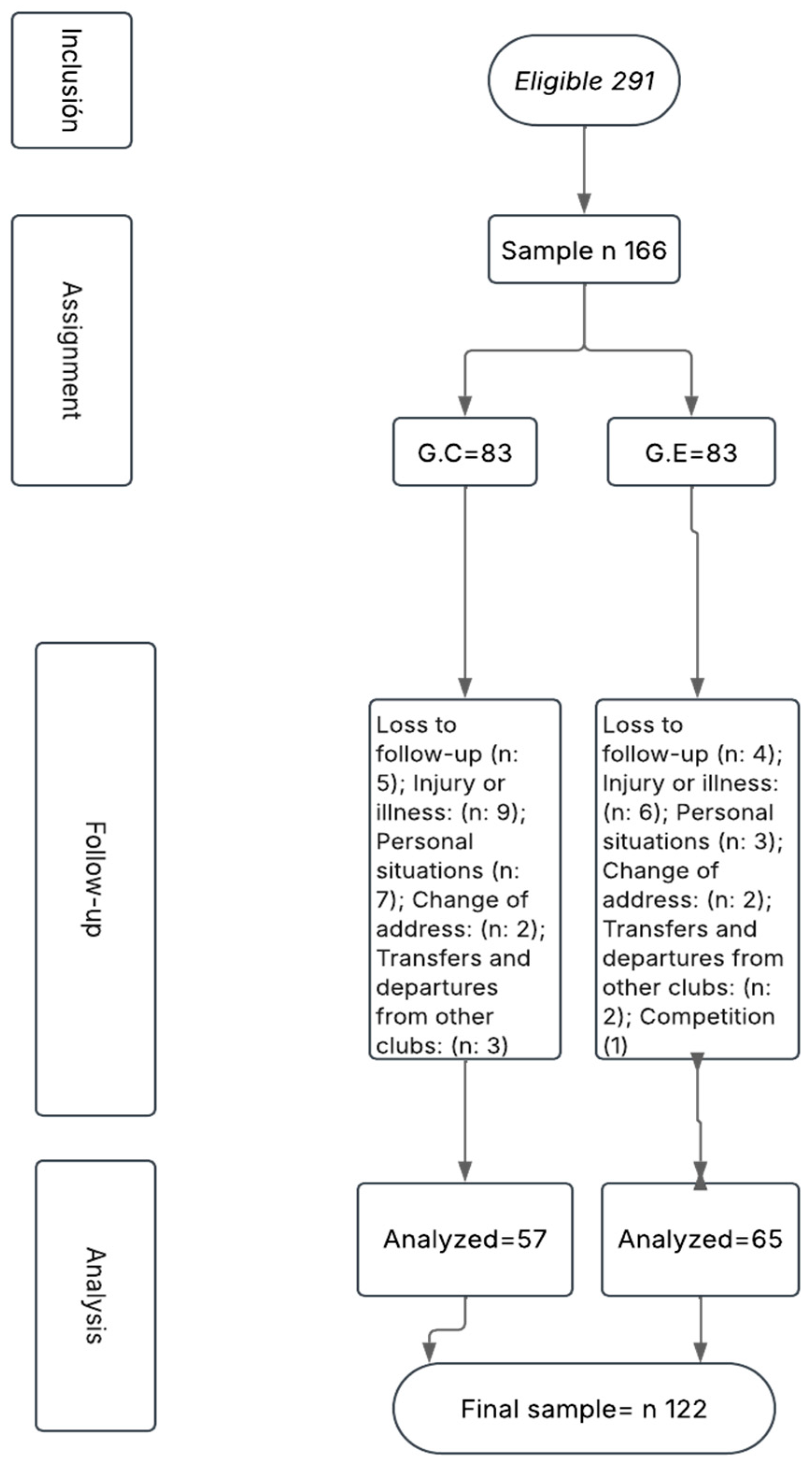

166 eligible athletes were registered, through simple random sampling (5% error and 95% confidence level), reaching a sample of 122 subjects, whose graphic protocol is described in

Figure 1. The sample was classified into two independent groups, a control group that performed their usual training for each sport (G.C), and an experimental group (G.E), which added Nordic exercises to their usual training. Both independent groups must have homogeneity in the variables of vertical jump and absolute strength of the dominant and non-dominant side, since the latter is measured on both sides, to avoid false results (

Table 1).

To assign the groups, a draw was carried out through an automated spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel 2021, where each participant was assigned a number, which was kept hidden until after the draw ended; identifying it at the time of assignment, where they were randomly subdivided into two independent groups: G.C (n=83) and G.E (n=83).

During the evaluation and intervention process, some athletes were excluded due to the causes explained in

Figure 1. Therefore, finally, the G.C was made up of 57 athletes and the G.E by 65 athletes (18±3 years), of different modalities: football (n=24), athletics/speed-100 and 200m (n=20), sport climbing (n=20), basketball (n=24), taekwondo (14 athletes) and cycling (n=20), describing their particularities in

Table 1.

2.2. Instrumentos

- (1)

Instrument 1: Vertical Jump: reliability of 0.97; VERT vertical jump device with G Windth of Nickel technology, to determine the jump distance in cm. [

35]

- (2)

Instrument 2: Absolute strength: lower limb dynamometer; strength levels, CRANE SCAL brand electronic leg scale, expresses values in kilograms and newtons. [

36]

2.3. Procedures

Before starting the research, potential participants were called, they were informed about the process, they signed the informed consent for their participation; highlighting that not all athletes coincided in time, since we are looking for those who are not in the stages close to their championships, from that point onwards to begin the intervention.

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality of personal data. The project was approved by the Honorable Board of Directors: of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Universidad Técnica del Norte-Ibarra, Republic of Ecuador, with resolution of the Directors Board: N° 325-CD 2021

7 physiotherapists were trained for the initial and final evaluation, who were already part of a pilot study where 60 athletes of different modalities were analyzed in the report published by Gómez, & Moya. [

8] The coaches of each sports discipline were also trained for the intervention and application of the protocol in conjunction with the aforementioned physiotherapists.

The research is classified into three phases:

- (1)

Pre-test: a) The participants were gathered by sports discipline in the training places, the study and informed consent were socialized; b) After this process, a draw was held to define the G.C and G.E.; c) Pre-test evaluations were carried out in the training places, prior to an agreement with the athletes and their coaches, establishing 2 previous days where they did not do any training, and came from a weekend of rest; d) The estimated evaluation time according to the pilot test carried out was 13 minutes per athlete.

- (2)

-

Training with Nordic exercises

Execution of the Nordic Hamstring Exercise:

a. Starting position:

Kneel on a padded surface.

Keep your torso upright and straight, looking forward.

Your partner or therapist holds your ankles firmly.

b. Activation and descent:

Contract your glutes, core, and back muscles to stabilize the trunk.

Arms should be crossed over the chest or extended alongside the body.

Begin to lean the torso forward, gradually extending the knees without bending at the hips.

Descend as slowly as possible, causing an eccentric extension of the hamstrings (Graph 1 and Graph 2)

Graph 1.

Training with Nordic exercises.

Graph 1.

Training with Nordic exercises.

Graph 2.

Grupal Training with Nordic exercises.

Graph 2.

Grupal Training with Nordic exercises.

- (3)

Posttest: After seven weeks of training, the corresponding evaluations were carried out on each athlete in each independent group. The same procedure was carried out as in the pretest, except for phase b, since the athletes had already been drawn.

For the pretest and posttest evaluations, a 20-minute warm-up was previously performed that included: general and specific joint mobility, upper and lower limb from proximal to distal, jogging on the ground, stretching of quadriceps and hamstrings, squats, weight dead and bridge-type exercises, with 10s of tension and 10s of rest, three series each.

Three evaluations were carried out, the average for the record was determined, the first day was evaluated with the vertical jump test, and on the second day the evaluations were carried out with the dynamometer.

2.4. Training with Nordic Exercises (Table 2)

- (1)

For 7 weeks, we worked with the G.E prior to the usual training sessions.

- (2)

A 15-minute warm-up similar to the pre-test was performed and a 5-minute cool-down period.

For training with Nordic exercises, the following planning was developed (

Table 2): a) During week 2 to week 4, it began with 2 series, and from week 5 to 8 with 3 series; b) For repetitions, it was considered to increase two repetitions per week or microcycle until week six, where it was maintained until week 7 and 8; c) It was ensured that the athletes maintain tension peaks in the 2s position initially, and gradually increase it to 5s; d) The breaks between series and series were 2min; with a total duration of 23 to 25 minutes.

The trained physiotherapists worked together with the training staff of each sporting discipline, monitoring each athlete in their individual progression, both in the G.E and the G.C, this was done in the same way in the G.C, who continued with their usual training, without any significant change.

2.5. Statistic Analysis

A database was developed, which was processed through the SPSS V.28 statistical package. The qualitative gender variable is presented in frequencies (f) and percentages (%); the quantitative variables, age, strength of the initial and final dominant side, strength of the initial and final non-dominant side, initial and final vertical jump, in mean values and standard error of the mean (±)

For inferential statistics, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was previously applied, identifying parametric data as there was a normal distribution, using the Student t test for related samples (t value) in intergroup comparisons, and the Student t test for independent samples to compare independent groups, with a significance value p= < 0.05.

3. Results

The initial dominant side strength (pre-intervention) between the control (G.C) and experimental (G.E) groups showed no significant differences, with an average of 12 kg; The strength of the non-dominant side also lacks significant differences with an average strength of 11 kg, and the vettical jump is between 40.5 and 42 cm, without significant differences between the G.C and G.E (

Table 3), which shows homogeneity of the independent samples in the study variables.

The G.E received the intervention for 7 weeks, generating significant differences between the initial and final values: The absolute strength of the dominant side initially registered averages of 12.4kg, and at the end of the intervention there was an increase of 14.5kg, with significant differences (p=<0.01). The absolute strength of the non-dominant side presented mean values of 11.1kg, and after the intervention time it increased to 13.8kg, likewise with significant differences between means (p=<0.01). The vertical jump was initially 42.4cm, and at the end 45.8cm was recorded, between the final and initial value, with a significant difference between means (p=<0.01) as described in table 4. In intergroup comparison of the G.C (

Table 4) no significant differences were evident between the pretest and posttest data in the three variables studied.

An important mean difference is evident between the vertical jump and the absolute strength of the final dominant and non-dominant side, when comparing the results between independent groups (p=<0.05), as described in

Table 5.

The strength values were analyzed by sport discipline, where the absolute strength of the dominant and non-dominant sides in the Experimental Group (EG) did not undergo significant changes between the initial and final assessments, except in football and basketball, where a significant difference was observed (p ≤ 0.05). Vertical jump increased significantly (p ≤ 0.05) in the Experimental Group (EG), except in cycling and taekwondo, where no changes were observed after the intervention (

Table 6).

In

Table 7, the repeated measures ANOVA shows that there was a significant difference in the three variables: dominant absolute strength (F=6.6; p=<0.01; ηp²=0.044); non-dominant (F=8.3; p=<0.01; ηp²=0.07); and explosive strength (F=19.03; p=<0.01; ηp²=0.14); indicating a reduction in the time/group interaction factor (T*G). However, in the time/sport discipline/group interaction factor (T.S.G), there were no significant differences in the three variables, as each displayed a different behavior.

4. Discussion

Our research aimed to analyze the effects of Nordic hamstring exercises on the lower limbs and their relationship with absolute strength and vertical jump performance, in accordance with the physical demands of various sports disciplines such as football, sprinting/track and field, basketball, sport climbing, cycling, and taekwondo.

To ensure population homogeneity, inclusion criteria and statistical tests such as Student's t-test were applied, confirming the absence of significant differences prior to the intervention. Additionally, differences were identified between the independent groups (Control Group – C.G. and Experimental Group – E.G.), both with high levels of participation. The majority of participants demonstrated right-side dominance. Notably, this is one of the few studies incorporating multiple sports disciplines into a single analysis, aiming to determine whether the effects of Nordic hamstring exercises are statistically significant and practically relevant for regular implementation.

The results are consistent with the existing scientific evidence on the benefits of Nordic hamstring exercises in enhancing lower limb muscle strength, particularly in injured athletes. The Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF) recommends the implementation of these exercises to both improve strength and prevent injuries, emphasizing their adaptability in terms of load and volume. Therefore, the present study included the disciplines and supports the applicability of Nordic exercises in both sports and therapeutic settings.

Several authors highlight the effectiveness of Nordic hamstring exercises in increasing eccentric hamstring strength in both male and female athletes. In this study, the intervention protocol maintained equal training volume, load, and frequency for both genders. Nonetheless, there is a recognized need for future studies with larger, gender-stratified samples to infer whether sex-specific responses to the intervention may occur.

According to Capaverde et al. [

41], age does not influence the effects of Nordic training protocols, with applicability ranging from adolescence to adulthood without significant differences (p = 0.12). Similarly, our study involved participants with a mean age of 18 years, ranging from 16 to 28, suggesting the intervention's suitability across various age groups.

There is limited literature regarding the influence of Nordic exercises on absolute strength. Current research also explores the development of new devices that support data collection and protocol implementation. Two reviewed articles assessed healthy athletes using dynamometry (expressed in newtons), reporting baseline values between 180 and 300 N (approximately 18 to 30 kg), with no significant pre- and post-intervention changes. In our study, control group participants showed average values of 12 kg (118 N), with no significant change (p > 0.05), while the experimental group recorded an average of 14.5 kg (143 N), with statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05).

Vianna et al. [

40] reported a significant increase in absolute strength (p = 0.003) in female football players after eight weeks of Nordic hamstring training, supporting its efficacy in strengthening the hamstrings.

Regarding vertical jump performance, de Villarreal et al. [

43] note that this ability can be improved through plyometric training programs incorporating bodyweight exercises and change-of-direction drills. Rønnestad and Mujika [

44] attribute such improvements to neuromuscular factors, such as increased motor unit recruitment angles, which enhance knee joint stability during jumping. In our study, a significant increase in jump height was observed in the experimental group, from 42 cm to 45 cm (p < 0.01).

Although absolute strength significantly improved in football and basketball, no relevant changes were observed in other disciplines (p > 0.05), consistent with Whyte et al. [

45], who reported up to a 19% increase in both dominant and non-dominant limbs, although interaction effects were not statistically significant. Still, these findings carry clinical implications, suggesting that Nordic exercises are beneficial for targeted interventions on the hamstrings [

46].

Most existing studies have focused primarily on football. A strength of our research is its inclusion of various sports disciplines. Significant improvements were observed in football and basketball. In contrast, a slight decrease in absolute strength was found in taekwondo, possibly related to the type of training used, as no significant differences were found between pre- and post-tests. Cardozo and Moreno-Jiménez [

47] advocate for the development of new parameters and more precise assessment tools to evaluate strength in taekwondo.

Regarding vertical jump performance, Nordic training led to height increases across most disciplines (p < 0.05), supporting Whyte’s [

45] conclusion that Nordic hamstring exercises enhance eccentric isokinetic strength and reduce injury risk in the hamstrings. However, no significant changes were found in cycling and taekwondo.

Study limitations include the inability to attribute strength gains solely to the Nordic exercises, as both control and experimental groups continued their regular training programs with progressive overload. While no significant differences were observed in the control group, slight improvements in strength and jump height were still recorded. Caution is advised in dosage and implementation, as despite appearing simple, these exercises are technically demanding, especially for individuals who do not train regularly or follow a structured program. Additionally, due to the small sample size, results should be interpreted with care, and future studies with larger samples and gender-based comparisons are encouraged.

This study considered sports disciplines such as taekwondo, cycling, basketball, sprinting/track and field, and sport climbing, where literature on the application of Nordic hamstring exercises is scarce. Therefore, this research serves as a theoretical and methodological foundation for future interventions in these sporting contexts.

5. Conclusions

The athletes have an age range between 16 and 28 years old, distributed between men and women in two independent groups, with homogeneous levels of strength in the initial stage. Applying an intervention process, it is concluded that the absolute and vertical jump of the G.E showed a significant positive difference between the initial and final phase, unlike the G.C. However, when analyzing the effects of Nordic training by sports discipline, it turned out to be effective in improving vertical jump in the modalities of football, basketball, athletics and climbing, taking into account the characteristics of these sports modalities that use movements where the hamstrings produce eccentric actions. Absolute strength only improved significantly in basketball, not registering major changes in the rest of the sports modalities studied. It is advisable to include stimuli with Nordic exercises according to the periodization and planning of strength training, because despite being considered "Gold Standard" exercises for hamstrings, they do not seem to be necessary in various sports modalities.

Practical Applications

- (1)

As has been described in this study, after the application of a Nordic training protocol in athletes of different modalities, it focused on the improvement of absolute strength and vertical jump, concluding that not all sports generate gains in this physical capacity.

- (2)

In this sense, it is considered that doctors, physiotherapists or people related to the protocol can develop this strength training program in accordance with the stage of the macrocycle they are going through.

- (3)

According to the results achieved, vertical jump improved in most of the modalities studied, except in cycling and taekwondo; Therefore, they can be applicable to improve the aforementioned capacity only in sports where Nordic stimulation has positive effects.

- (4)

Regarding absolute strength, the implemented protocol has positive effects on absolute strength in basketball and soccer.

- (5)

The scope of the 7-week Nordic training protocol has limited effects; Therefore, its improvement may be temporary or may be linked to load management within each macrocycle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: V.P.-M.; Methodology: V.P.-M.; S.C.-M.; Validation: R.P.-G. and V.P.-M.; Formal analysis: V.P.-M; S.C.-M. and R.P.-G.; Investigation: V.P.-M., R.P.-G.; Resources: R.P.-G.; Data curation: V.P.-M.. and R.P.-G.; Writing—original draft preparation: V.P.-M. and S.C.-M. Funding acquisition: R.P.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Honorable Board of Directors: ID: N° 325-CD 2021; Faculty of Health Sciences of the Universidad Técnica del Norte- Ibarra- Ecuador.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the qualitative nature of the study.

Acknowledgments

To the Research Project “Optimización del proceso de dirección del entrenamiento en deportes de cooperación-oposición (Senescyt: CEB-PROMETEO-007-2013). To the AFIDESA Research Group of the Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas-ESPE. On the other hand, we also thank the Research Project called:“Análisis de la fuerza muscular pre y post entrenamiento Nórdico en deportistas de Imbabura período 2022” (Resolution: 325-CD), of the Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra-Ecuador.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no interest conflict.

References

- Bompa T, Buzzichelli C. Periodization of strength training for sports USA: Human Kinetics Publishers; 2021.

- Calero-Morales S, Vinueza-Burgos GD, Yance-Carvajal CL, Paguay-Balladares WJ. Gross Motor Development in Preschoolers through Conductivist and Constructivist Physical Recreational Activities: Comparative Research. Sports. 2023; 11(3): 61. [CrossRef]

- Biz C, Nicoletti P, Baldin G, Bragazzi NL, Crimì A, Ruggieri P. Hamstring strain injury (HSI) prevention in professional and semi-professional football teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021; 18(16): 8272. [CrossRef]

- Buckthorpe M, Danelon F, La Rosa G, Nanni G, Stride M, Della Villa F. Recommendations for hamstring function recovery after ACL reconstruction. Sports Medicine. 2021; 51(4): 607-624. [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys I, Moody J. Strength and conditioning for sports performance. 2nd ed. NY: Routledge; 2021.

- Augustsson J, Alt T, Andersson H. Speed Matters in Nordic Hamstring Exercise: Higher Peak Knee Flexor Force during Fast Stretch-Shortening Variant Compared to Standard Slow Eccentric Execution in Elite Athletes. Sports. 2023; 11(7): 130. [CrossRef]

- Kasper K. Sports training principles. Current sports medicine reports. 2019; 18(4): 95-96. [CrossRef]

- Gómez RP, Moya VP. Analysis of the Nordic curl protocol in the flexibility of athletes. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación. 2023; 48: 720-726. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Piqueras P, Martínez-Serrano A, Freitas TT, Gómez Díaz A, Loturco I, Giménez E, et al. Weekly Programming of Hamstring-Related Training Contents in European Professional Soccer. Sports. 2024; 12(3): 73. [CrossRef]

- Lee JW, Mok KM, Chan HC, Yung PS, Chan KM. Eccentric hamstring strength deficit and poor hamstring-to-quadriceps ratio are risk factors for hamstring strain injury in football: A prospective study of 146 professional players. Journal of science and medicine in sport. 2018; 21(8): 789-93. [CrossRef]

- Patiño BA, Uribe JD, Valderrama V. Bibliometric analysis of plyometrics in sport: 40 years of scientific production. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación. 2024; 53: 183-195. [CrossRef]

- Franchina M, Turati M, Tercier S, Kwiatkowski B. FIFA 11+ Kids: Challenges in implementing a prevention program. Journal of Children's Orthopaedics. 2023; 17(1): 22-27. [CrossRef]

- Freeman BW, Young WB, Talpey SW, Smyth AM, Pane CL, Carlon TA. The effects of sprint training and the Nordic hamstring exercise on eccentric hamstring strength. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness. 2019; 59(7): 1119-1125. [CrossRef]

- van de Hoef PA, Brink MS, Huisstede BM, van Smeden M, de Vries N, Goedhart EA, et al. Does a bounding exercise program prevent hamstring injuries in adult male soccer players?–A cluster-RCT. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2019; 29(4): 515-523. [CrossRef]

- Rudisill SS, Varady NH, Kucharik MP, Eberlin CT, Martin SD. Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention and risk factor management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American journal of sports medicine. 2023; 51(7): 1927-1942. [CrossRef]

- Danielsson A, Horvath A, Senorski C, Alentorn-Geli E, Garrett WE, Cugat R, et al. The mechanism of hamstring injuries–a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2020; 21: 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Alvares JB, Dornelles MP, Fritsch CG, de Lima-E-Silva FX, Medeiros TM, Severo-Silveira L, et al. Prevalence of hamstring strain injury risk factors in professional and under-20 male football (soccer) players. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2020; 29(3): 339-345. [CrossRef]

- Timmins RG, Bourne MN, Shield AJ, Williams MD, Lorenzen C, Opar DA. Short biceps femoris fascicles and eccentric knee flexor weakness increase the risk of hamstring injury in elite football (soccer): a prospective cohort study. British journal of sports medicine. 2016; 50(24): 1524-1535. [CrossRef]

- Kalema RN, Schache AG, Williams MD, Heiderscheit B, Siqueira Trajano G, Shield AJ. Sprinting biomechanics and hamstring injuries: Is there a link? A literature review. Sports. 2021; 9(10): 141. [CrossRef]

- Reis FJ, Macedo AR. Influence of hamstring tightness in pelvic, lumbar and trunk range of motion in low back pain and asymptomatic volunteers during forward bending. Asian spine journal. 2015; 9(4): 535. [CrossRef]

- Willauschus M, Rüther J, Millrose M, Walcher M, Lambert C, Bail HJ, et al. Foot and Ankle Injuries in Elite Taekwondo Athletes: A 4-Year Descriptive Analysis. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021; 9(12): 2021 23259671211061112. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura Y, Sakuma K, Fujita S, Aoki K, Takazawa Y. Effects of various numbers of runs on the success of hamstring injury prevention program in sprinters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15): 9375. [CrossRef]

- Nuell S, Illera-Dominguez V, Carmona G, Macadam P, Lloret M, Padullés JM, et al. Hamstring muscle volume as an indicator of sprint performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2021; 35(4): 902-909. [CrossRef]

- Minghelli B, Machado L, Capela R. Musculoskeletal injuries in taekwondo athletes: a nationwide study in Portugal. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 2020; 66(2): 124-132. [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie R, Monaghan L, Masson RA, Werner AK, Caprez TS, Johnston L, et al. Physical and physiological determinants of rock climbing. International journal of sports physiology and performance. 2020; 15(2): 168-179. [CrossRef]

- Donti O, Papia K, Toubekis A, Donti A, Sands WA, Bogdanis GC. Flexibility training in preadolescent female athletes: Acute and long-term effects of intermittent and continuous static stretching. Journal of sports sciences. 2018; 36(13): 1453-1460. [CrossRef]

- Smajla D, Kozinc Z, Šarabon N. Associations between lower limb eccentric muscle capability and change of direction speed in basketball and tennis players. PeerJ. 2022; 10: e13439. [CrossRef]

- Kotler DH, Babu AN, Robidoux G. Prevention, evaluation, and rehabilitation of cycling-related injury. Current sports medicine reports. 2016; 15(3): 199-206. [CrossRef]

- Tumiñá-Ospina DM, Rivas-Campo Y, García-Garro PA, Gómez-Rodas A, Afanador DF. Efectividad de los ejercicios nórdicos sobre la incidencia de lesiones de isquiotibiales en futbolistas profesionales y amateur masculinos entre los 15 y 41 años. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte. 2022; 11(3): 47-65. [CrossRef]

- Edouard P, Pollock N, Guex K, Kelly S, Prince C, Navarro L, et al. Hamstring muscle injuries and hamstring specific training in elite athletics (track and field) athletes. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022; 19(17): 10992. [CrossRef]

- Huygaerts S, Cos F, Cohen DD, Calleja-González J, Guitart M, Blazevich AJ, et al. Mechanisms of hamstring strain injury: interactions between fatigue, muscle activation and function. Sports. 2020; 8(5): 65. [CrossRef]

- Saleh A, Al Attar W, Faude O, Husain MA, Soomro N, Sanders RH. Combining the Copenhagen adduction exercise and nordic hamstring exercise improves dynamic balance among male athletes: a randomized controlled trial. Sports Health. 2021; 13(6): 580-587. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert M, Ripley N, McMahon JJ, Evans M, Haff GG, Comfort P. The effect of Nordic hamstring exercise intervention volume on eccentric strength and muscle architecture adaptations: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Sports Medicine. 2020; 50: 83-99. [CrossRef]

- Siedlecki SL. Quasi-experimental research designs. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 2020; 34(5): 198-202. [CrossRef]

- Manor J, Bunn J, Bohannon RW. Validity and reliability of jump height measurements obtained from nonathletic populations with the VERT device. Journal of geriatric physical therapy. 2020; 43(1): 20-23. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Franco N, Jiménez-Reyes P, Montaño-Munuera JA. Validity and reliability of a low-cost digital dynamometer for measuring isometric strength of lower limb. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2017; 35(22): 2179-2184. [CrossRef]

- Raya-Gonzalez J, Castillo D, Clemente FM. Injury prevention of hamstring injuries through exercise interventions. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2021; 61(9): 1242-1251. [CrossRef]

- Ishøi L, Krommes K, Husted RS, Juhl CB, Thorborg K. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of common lower extremity muscle injuries in sport–grading the evidence: a statement paper commissioned by the Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF). British journal of sports medicine. 2020; 54(9): 528-537. [CrossRef]

- Al Attar WS, Soomro N, Sinclair PJ, Pappas E, Sanders RH. Effect of injury prevention programs that include the Nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injury rates in soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine. 2017; 47: 907-916. [CrossRef]

- Vianna KB, Rodrigues LG, Oliveira NT, Ribeiro-Alvares JB, Baroni BM. A preseason training program with the nordic hamstring exercise increases eccentric knee flexor strength and fascicle length in professional female soccer players. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2021; 16(2): 459. [CrossRef]

- Capaverde VD, Oliveira GD, de Lima-E-Silva FX, Ribeiro-Alvares JB, Baroni BM. Do age and body size affect the eccentric knee flexor strength measured during the Nordic hamstring exercise in male soccer players? Sports Biomechanics. 2021;: 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Drury B, Peacock D, Moran J, Cone C, Campillo RR. Different interset rest intervals during the Nordic hamstrings exercise in young male athletes. Journal of athletic training. 2021; 56(9): 952-959. [CrossRef]

- de Villarreal ES, Molina JG, de Castro-Maqueda G, Gutiérrez-Manzanedo JV. Effects of plyometric, strength and change of direction training on high-school basketball player’s physical fitness. Journal of Human Kinetics. 2021; 78(1): 175-186. [CrossRef]

- Rønnestad BR, Mujika I. Optimizing strength training for running and cycling endurance performance: A review. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2014; 24(4): 603-612. [CrossRef]

- Whyte EF, Heneghan B, Feely K, Moran KA, O'Connor S. The effect of hip extension and Nordic hamstring exercise protocols on hamstring strength: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2021; 35(10): 2682-2689. [CrossRef]

- Llurda-Almuzara L, Labata-Lezaun N, López-de-Celis C, Aiguadé-Aiguadé R, Romaní-Sánchez S, Rodríguez-Sanz J, et al. Biceps femoris activation during hamstring strength exercises: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16): 8733. [CrossRef]

- Cardozo LA, Moreno-Jiménez J. Valoración de la fuerza explosiva en deportistas de taekwondo: una revisión sistemática. Kronos. 2018; 17(1): 1-15. https://revistakronos.info/articulo/valoracion-de-la-fuerza-explosiva-en-deportistas-de-taekwondo-una-revision-sistematica-2430-sa-y5b4e14fcec173.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).