Submitted:

21 May 2024

Posted:

22 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Diagnosis

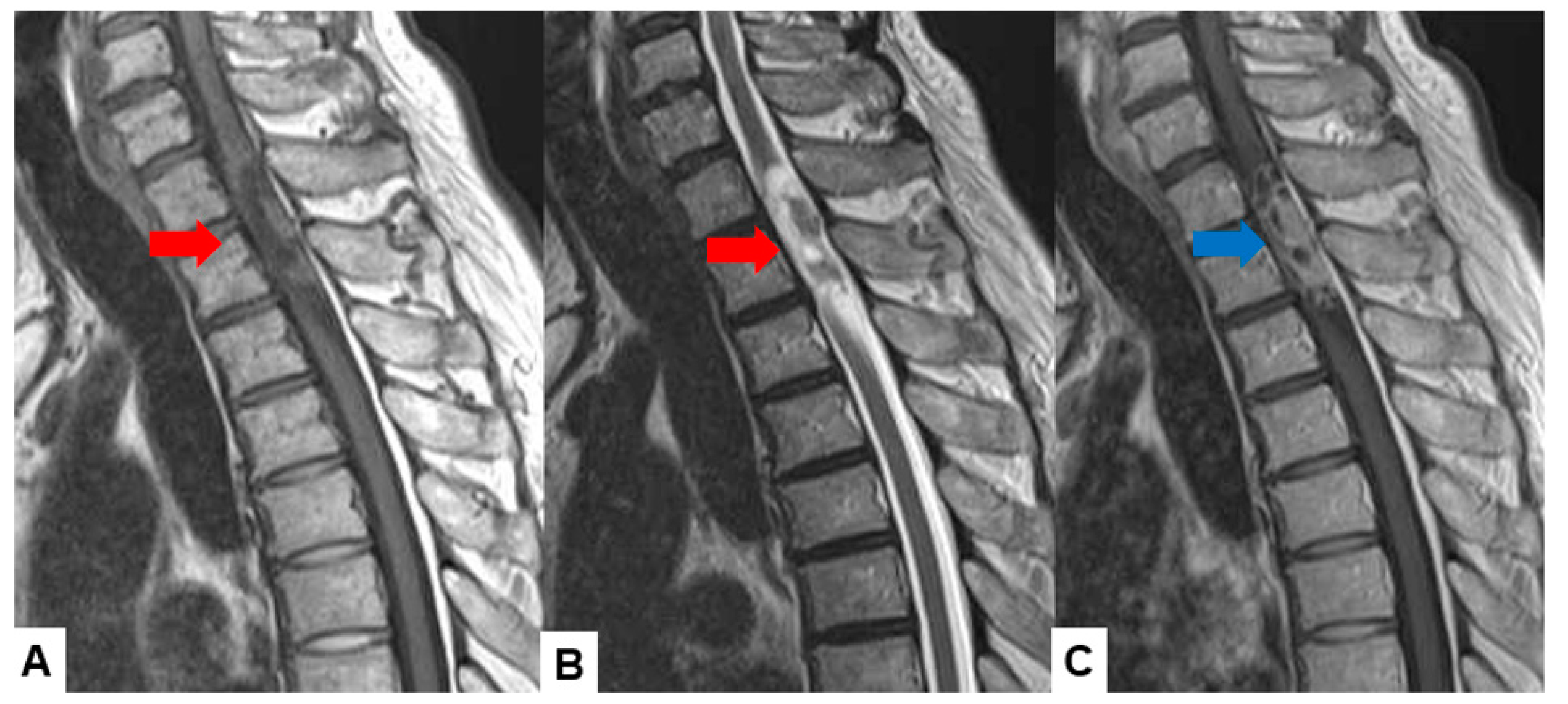

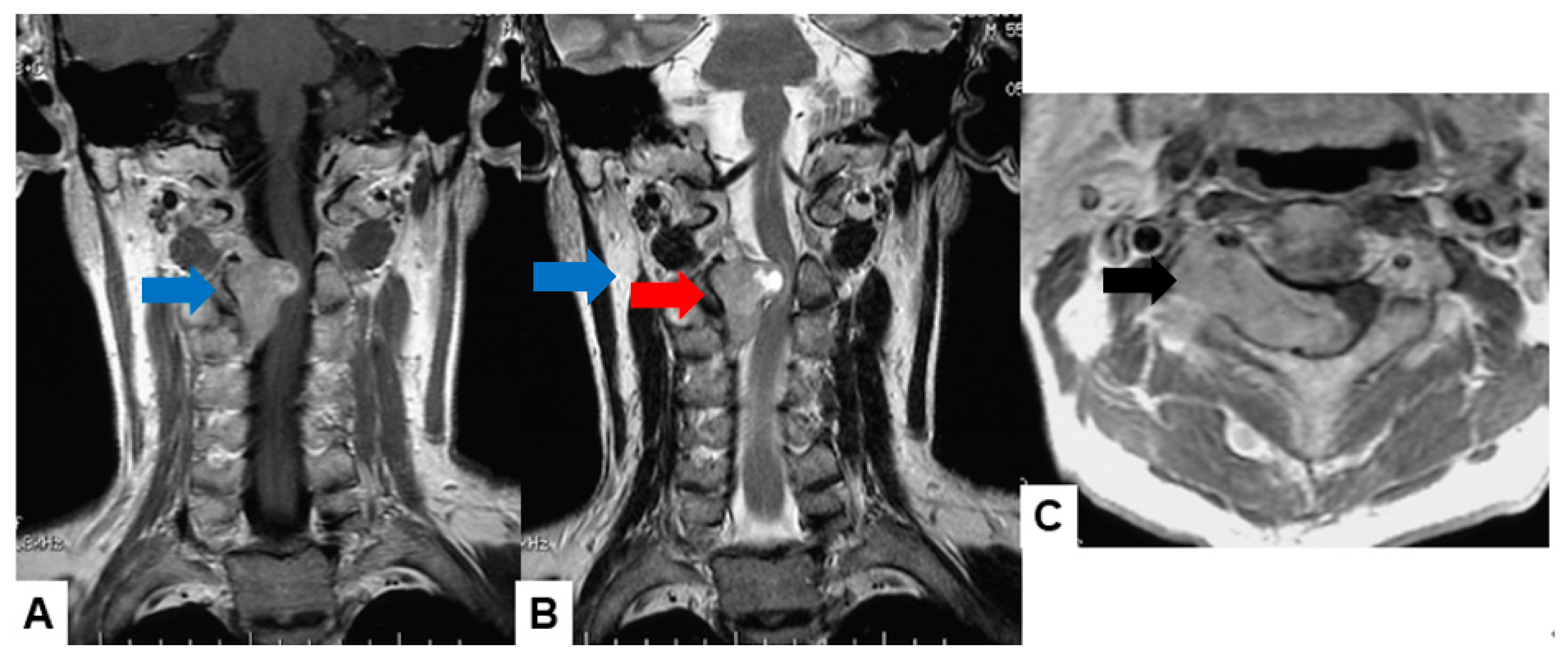

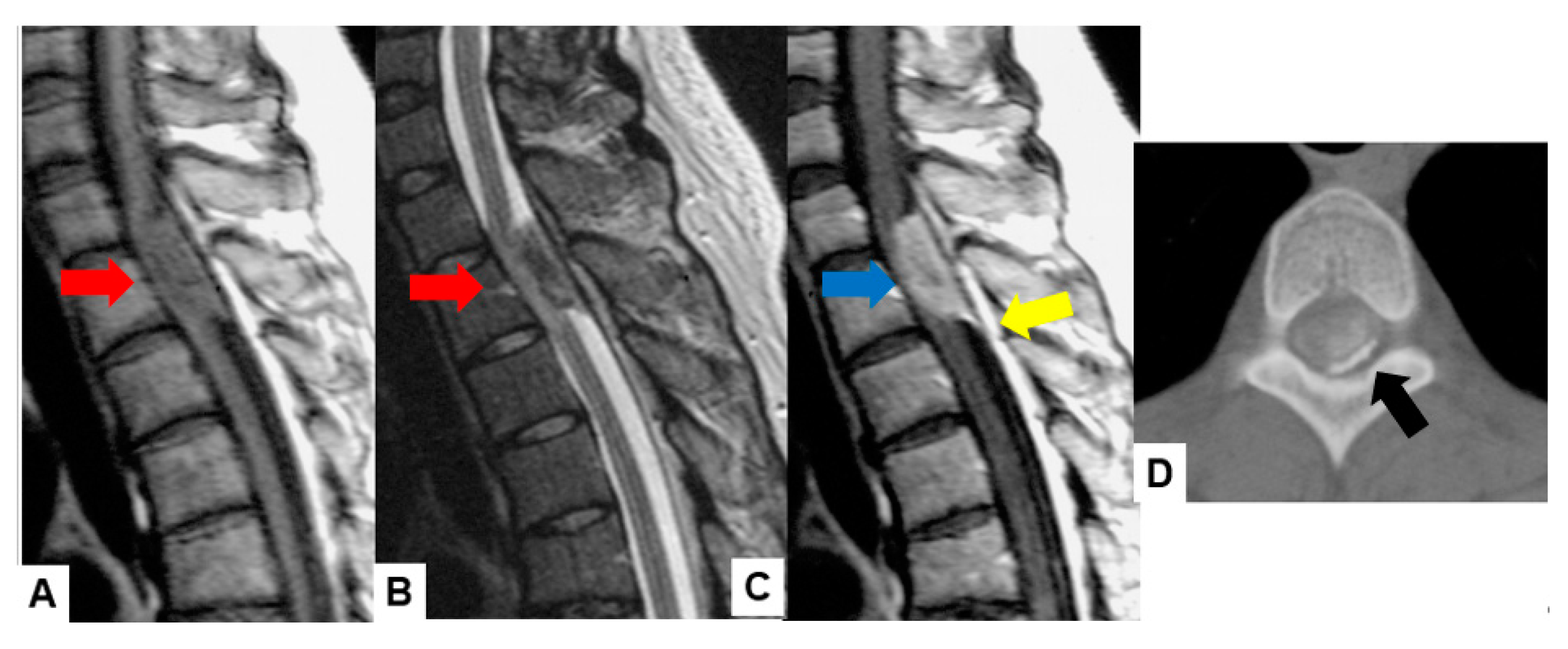

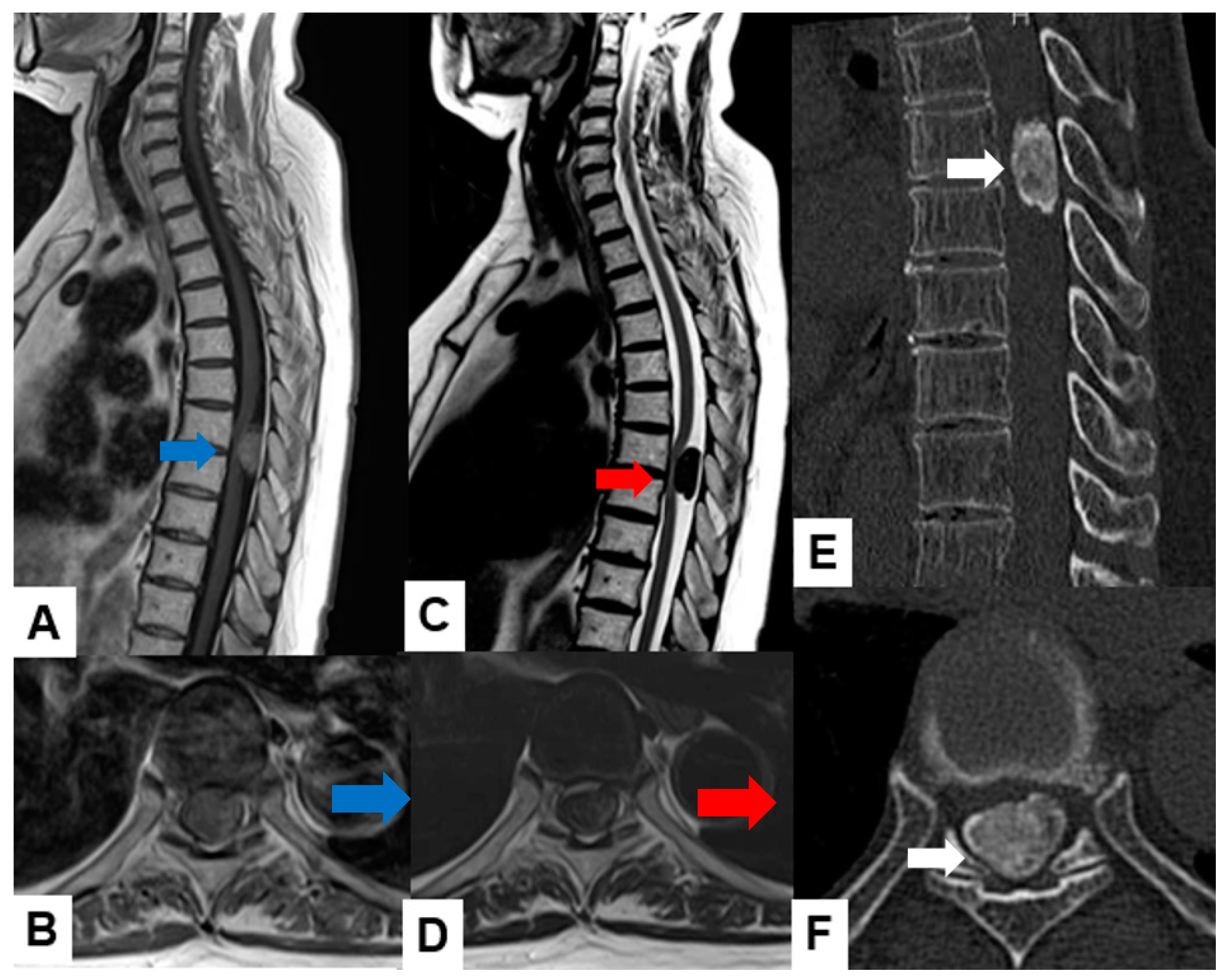

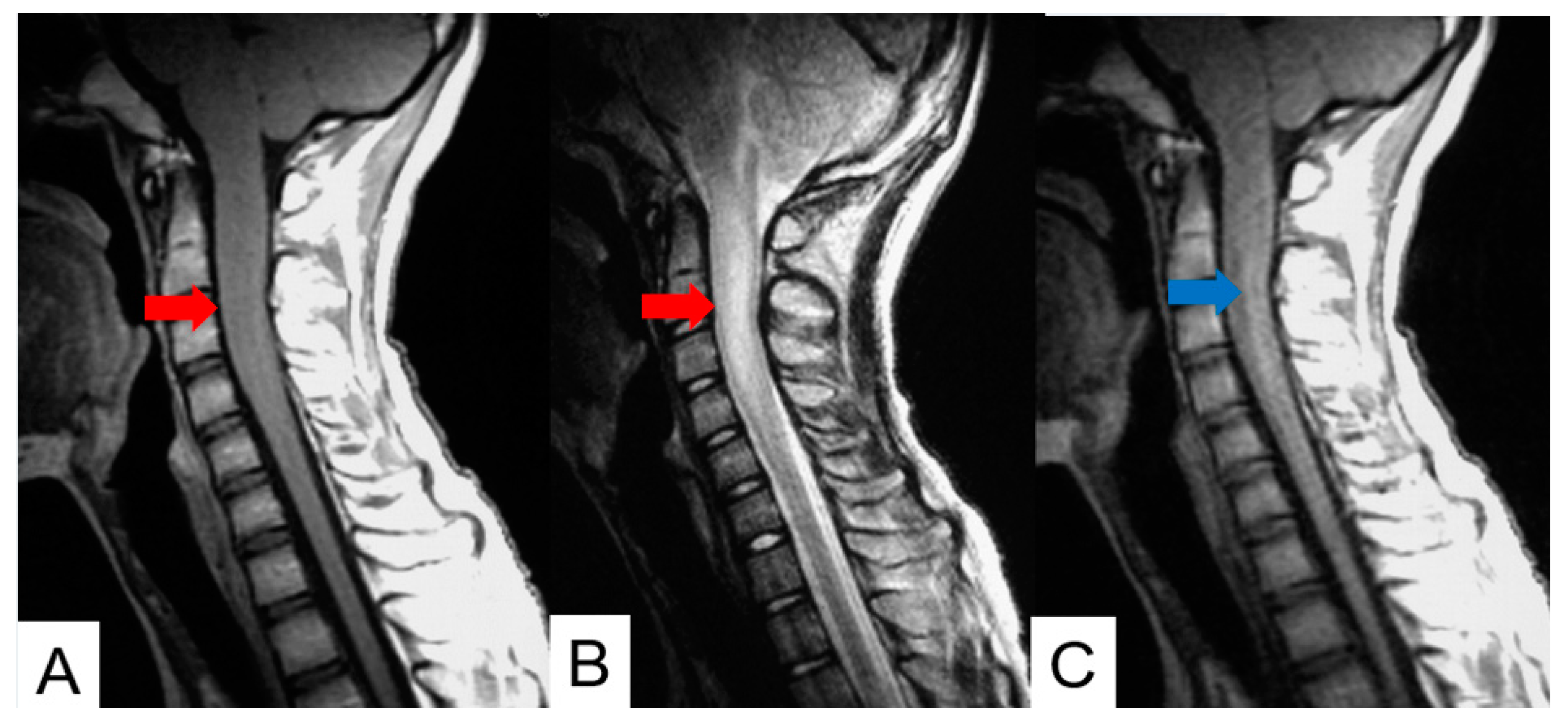

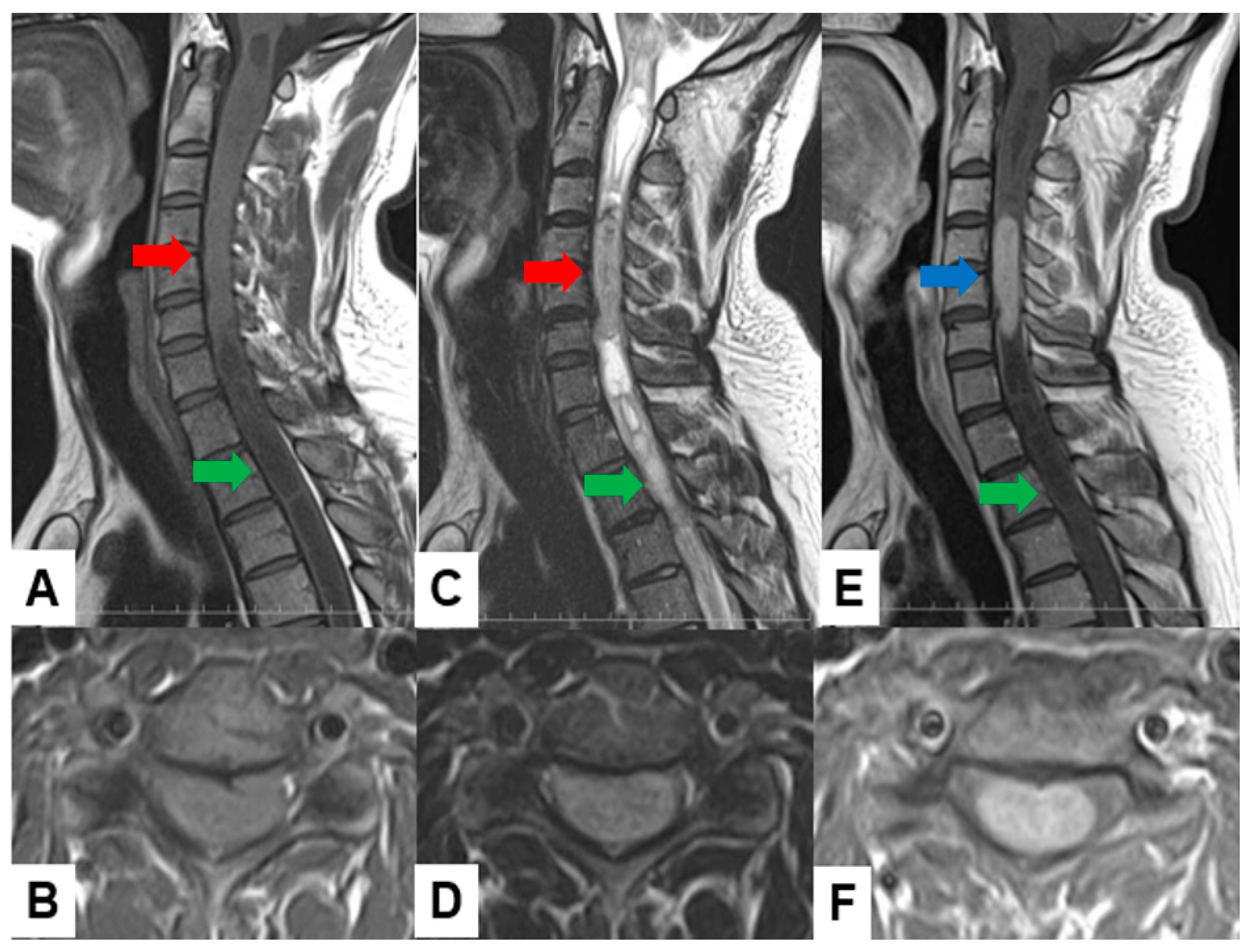

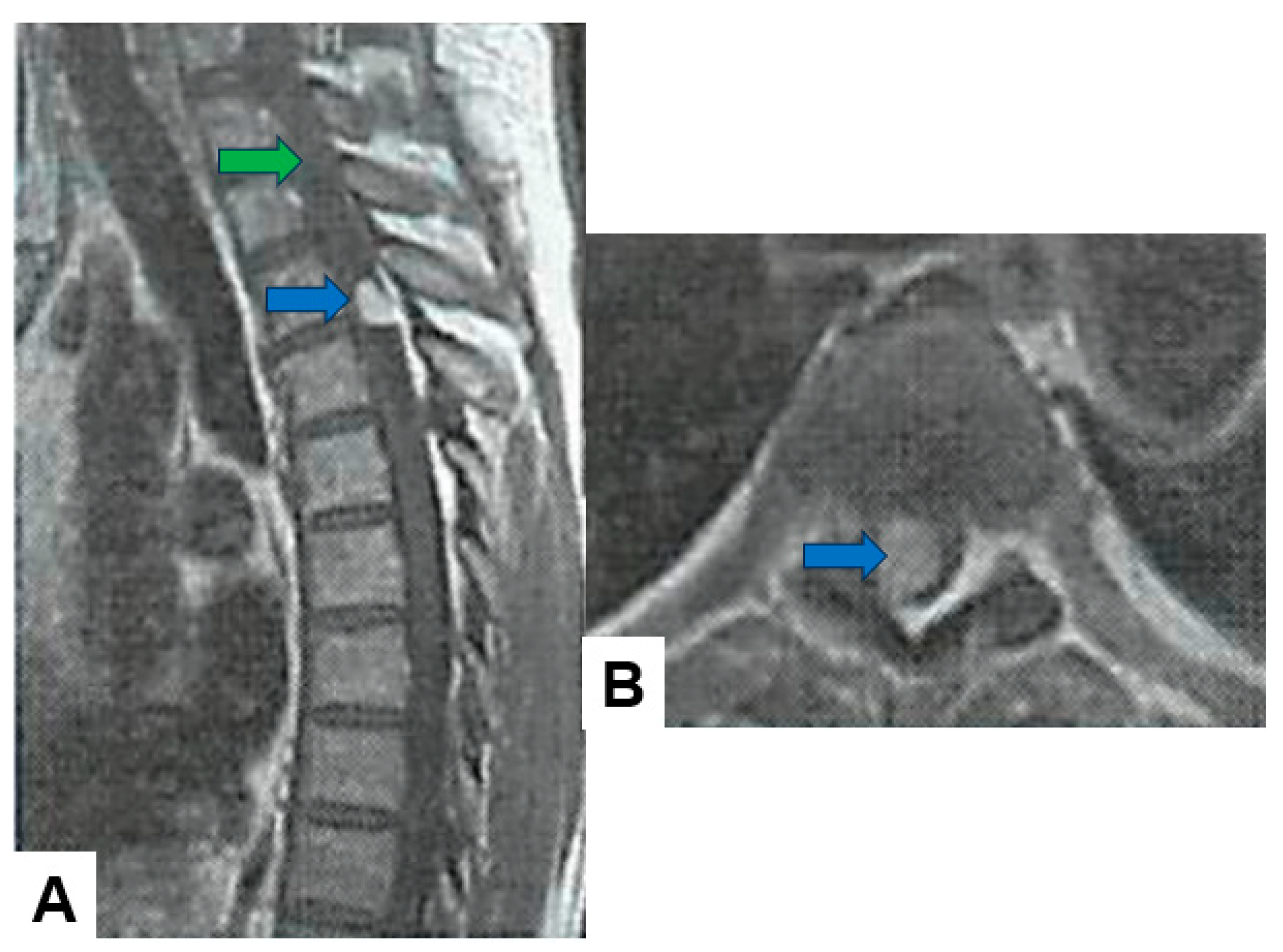

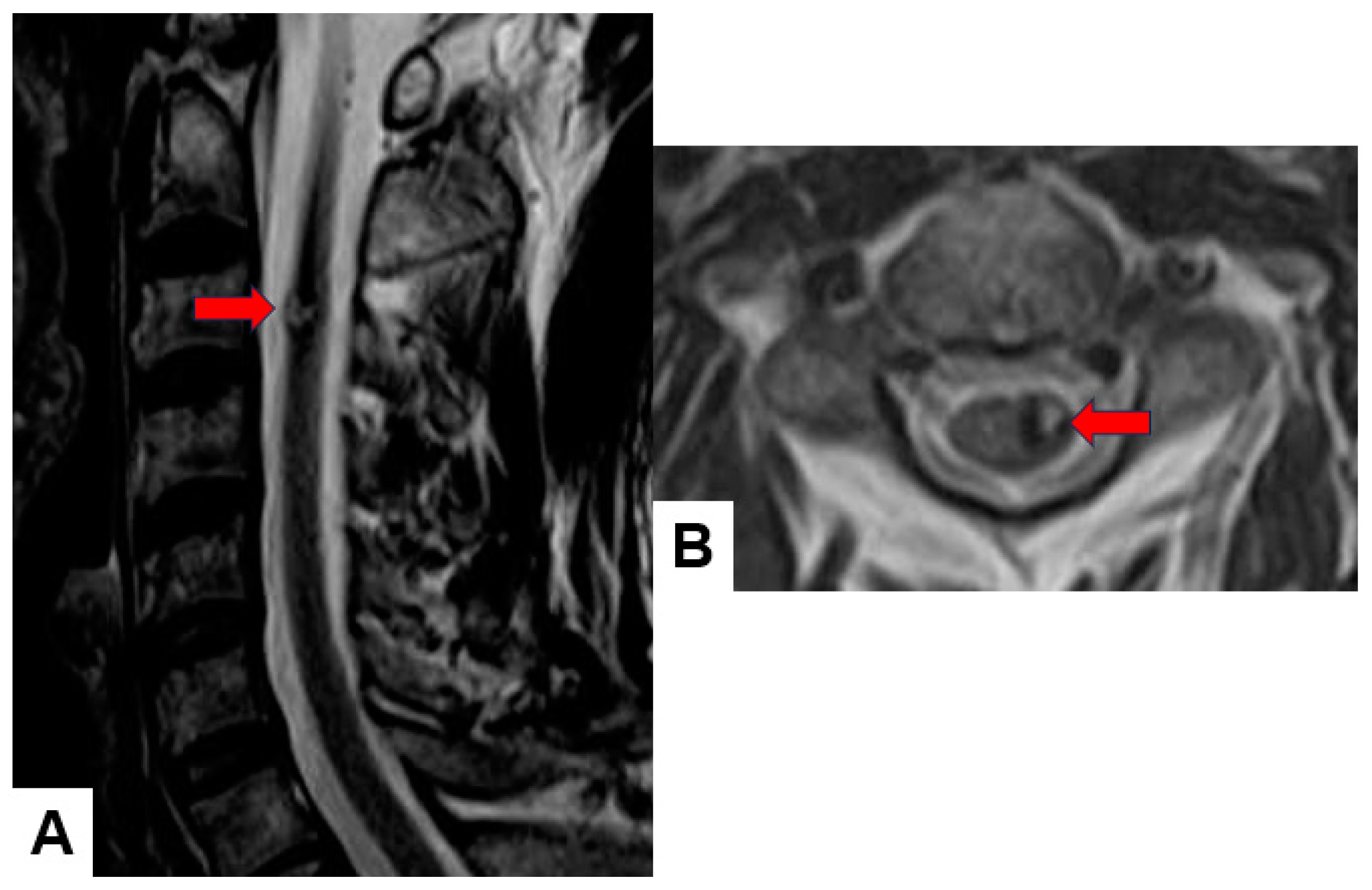

2.1. MRI and CT

2.2. Molecular and Genetic Profiling

3. Current Treatment Strategies and Their Limitations

3.1. Surgical Method

3.2. Radiotherapy

3.3. Systemic Therapy

4. Emerging Treatment Strategies

4.1. Immunotherapy

4.2. Neural Stem Cells

4.3. Cancer Vaccine

4.4. Tumor-Targeted Therapies (Nanotechnology)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimm, S.; Chamberlain, M.C. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009, 9, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, M.K.; Geraghty, J.R.; Engelhard, H.H.; Linninger, A.A.; Mehta, A.I. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: A review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg. Focus 2015, 39, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniutti, M.; Sasso, A.L.; Carai, A.; Colafati, G.S.; Piccirilli, E.; Del Baldo, G.; Mastronuzzi, A. Central nervous system tumours in neonates: what should the neonatologist know? Eur J Pediatr. 2024, 183, 1485–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raco, A.; Esposito, V.; Lenzi, J.; Piccirilli, M.; Delfini, R.; Cantore, G. Long- term follow-up of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a series of 202 cases. Neurosurgery 2005, 56, 972–981. [Google Scholar]

- Parsa, A.T.; Lee, J.; Parney, I.F.; Weinstein, P.; McCormick, P.C.; Ames, C. Spinal cord and intradural-extraparenchymal spinal tumors: current best care practices and strategies. J. Neurooncol. 2004, 69, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall DP, Googe DJ, Emery RL, Thompson DB, Campbell SE, Ly JQ, et al. Extramedullary intradural spinal tumors: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2007, 36, 185–198. [CrossRef]

- Ciftdemir, M.; Kaya, M.; Selcuk, E.; Yalniz, E. Tumors of the spine. World J Orthop. 2016, 7, 109–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, J.M.; Hoang, S.; Mesfin, F.B. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors. StatPearls Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2022.

- Arnautovic, K.; Arnautovic, A. Extramedullary intradural spinal tumors: a review of modern diagnostic and treatment options and a report of a series. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2009, 9, 40–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 10. Chamberlain MC, Tredway TL. Adult primary intradural spinal cord tumors: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011, 11, 320–328. [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.M.; McCarthy, B.J.; McLendon, R.E.; Dolecek, T.A.; Kruchko, C.; Douglas, L.L.; Ajani, U.A. Descriptive epidemiology of malignant and nonmalignant primary spinal cord, spinal meninges, and cauda equina tumors, United States, 2004–2007. Cancer. 2012, 118, 4220–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, M.T.; Johnson, M.D.; Sul, J.; Mohile, N.A.; Korones, D.N.; Okunieff, P.; Walter, K.A. Primary spinal cord glioma: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database study. J Neurooncol. 2010, 98, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristante, L.; Herrmann, H.D. Surgical management of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: functional outcome and sources of morbidity. Neurosurgery. 1994, 35, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, F.J.; Farmer, J.P.; Freed, D. Adult intramedullary astrocytomas of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg. 1992, 77, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David N Louis, Arie Perry, Pieter Wesseling, Daniel J Brat, Ian A Cree, Dominique Figarella-Branger, Cynthia Hawkins, H K Ng, Stefan M Pfister, Guido Reifenberger, Riccardo Soffietti, Andreas von Deimling, David W Ellison, The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary, Neuro-Oncology, 2021, Volume 23, Issue 8, Pages 1231–1251. [CrossRef]

- Porras, J.L.; Pennington, Z.; Hung, B.; Hersh, A.; Schilling, A.; Goodwin, C.R.; Sciubba, D.M. Radiotherapy and Surgical Advances in the Treatment of Metastatic Spine Tumors: A Narrative Review. World Neurosurg. 2021; 151, 147–154. [CrossRef]

- Elsberg, C.A. Some aspects of the diagnosis and surgical treatment of tumors of the spinal cord: With a study of the end results in a series of 119 operations. Ann Surg. 1925, 81, 1057–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, A.M.; Shen, S.H.; Salgado, M.A.; Congdon, K.L.; Sanchez-Perez, L. Promising vaccines for treating glioblastoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2018, 18, 1159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.S.; Prados, M. Textbook of neuro-oncology, 2025, 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.

- Hu, J.; Liu, T.; Han, B.; Tan, S.; Guo, H.; Xin, Y. A Potential Approach for High-Grade Spinal Cord Astrocytomas. Front Immunol. 2021, 11, 582828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sumdani, H.; Aguilar-Salinas, P.; Avila, M.J.; Barber, S.R.; Dumont, T. Utility of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Spine Surgery: A Systematic Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2022, 161, e8–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, C.; Melnick, K.; Porche, K.; Dastmalchi, F.; Hoh, D.J.; Rahman, M.; Ghiaseddin, A. Glioma immunotherapy: Advances and challenges for spinal cord gliomas. Neurospine. 2022, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missenard, G.; Bouthors, C.; Fadel, E.; Court, C. Surgical strategies for primary malignant tumors of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2020, 106, S53–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolov, G.; Kehayov, I.; Kitov, B. Clinical aspects of spinal meningiomas: a review. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2021, 63, 24–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeller, K.K.; Shih, R.Y. Intradural extramedullary spinal neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2019, 39, 468–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Castro, E.; Meraz-Soto, J.M.; Hernández-Dehesa, I.A.; Tena-Suck, M.L.; Hernández-Reséndiz, R.; Mateo-Nouel, E.J.; Ponce-Gómez, J.A.; Arriada-Mendicoa, J.N. Spinal Ependymomas: An Updated WHO Classification and a Narrative Review. Cureus. 2023 Nov 20;15:e49086. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Jung, C.H. Metastatic spinal tumor. Asian Spine J. 2012, 6, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, F.M.; Soo, M.Y.; Ng, T. Chordoma: radiological-pathological correlation. Australas Radiol. 2005, 49, 261–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thippeswamy, P.B.; Soundararajan, D.C.R.; Kanna, R.M.; Kuna, V.S.; Rajasekaran, S. Sporadic Intradural Extramedullary Hemangioblastoma of Cauda Equina with Large Peritumoral Cyst-A Rare Presentation. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2022, 31, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, K.; Tomita, H.; Hara, A. Peritumoral Edema in Gliomas: A Review of Mechanisms and Management. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, M.; Dumrongpisutikul, N.; Intrapiromkul, J.; Yousem, D.M. Detection of intratumoral calcification in oligodendrogliomas by susceptibility-weighted MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012, 33, 858–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bönig, L.; Möhn, N.; Ahlbrecht, J.; Wurster, U.; Raab, P.; Puppe, W.; Sühs, K.W.; Stangel, M.; Skripuletz, T.; Schwenkenbecher, P. Leptomeningeal Metastasis: The Role of Cerebrospinal Fluid Diagnostics. Front Neurol. 2019, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Razek, A.A.K.; Gamaleldin, O.A.; Elsebaie, N.A. Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors of Head and Neck: Imaging-Based Review of World Health Organization Classification. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2020, 44, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraky, A.M.; Beck, R.T.; Treffy, R.W.; Aaronson, D.M.; Hedayat, H. Role of Advanced MR Imaging in Diagnosis of Neurological Malignancies: Current Status and Future Perspective. J Integr Neurosci. 2023, 22, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemay, A.; Gros, C.; Zhuo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Duan, Y.; Cohen-Adad, J.; Liu, Y. Automatic multiclass intramedullary spinal cord tumor segmentation on MRI with deep learning. Neuroimage Clin. 2021, 31, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, A. Promise and Provisos of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Healthcare. J Healthc Leadersh. 2022, 14, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, M.K.; Geraghty, J.R.; Engelhard, H.H.; Linninger, A.A.; Mehta, A.I. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015, 39, E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallo, G.I.; Freed, D.; Epstein, F. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2003, 19, 641–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.S.; Choi, Y.S.; Ahn, S.S.; Yi, S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.K. Differentiation between spinal cord diffuse midline glioma with histone H3 K27M mutation and wild type: Comparative magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroradiology 2019, 61, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M.; Anoosha, P.; Yesudhas, D.; Gromiha, M.M. Identification of potential driver mutations in glioblastoma using machine learning. Brief Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, C.; von Haken, M.; Meyer-Puttlitz, B.; Wiestler, O.D.; Reifenberger, G.; Pietsch, T.; von Deimling, A. Molecular genetic analysis of ependymal tumors. NF2 mutations and chromosome 22q loss occur preferentially in intramedullary spinal ependymomas. Am J Pathol. 1999, 155, 627–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, D.D.; Mugge, L.A.; Awan, O.K.; Gong, A.D.; Fanous, A.A. Spinal Meningiomas: A Comprehensive Review and Update on Advancements in Molecular Characterization, Diagnostics, Surgical Approach and Technology, and Alternative Therapies. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sestini, R.; Bacci, C.; Provenzano, A.; Genuardi, M.; Papi, L. Evidence of a four-hit mechanism involving SMARCB1 and NF2 in schwannomatosis-associated schwannomas. Hum Mutat. 2008, 29, 227–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar M.A.; El-Baba C.; Elnaggar M.H.; Elkholy Y.O.; Mottawea M.; Johar D.; Al Shehabi T.S.; Kobeissy F.; Moussalem C.; Massaad E.; Omeis I, Darwiche N, Eid AH. Novel therapeutic strategies for spinal osteosarcomas. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 64, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- Ottenhausen, M.; Ntoulias, G.; Bodhinayake, I.; Ruppert, F.-H.; Schreiber, S.; Förschler, A.; Boockvar, J.A.; Jödicke, A. Intradural spinal tumors in adults—Update on management and outcome. Neurosurg. Rev. 2019, 42, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, H.G.; Dunn, I.F. Chondrosarcoma and Chordoma of the Skull Base and Spine: Implication of Tumor Location on Patient Survival. World Neurosurg. 2022, 162, e635–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahangar, P.; Akoury, E.; Ramirez Garcia Luna, A.S.; Nour, A.; Weber, M.H.; Rosenzweig, D.H. Nanoporous 3D-Printed Scaffolds for Local Doxorubicin Delivery in Bone Metastases Secondary to Prostate Cancer. Materials. 2018, 11, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, R.; Anazawa, U.; Hotta, H.; Watanabe, I.; Takahashi, Y.; Matsumoto, S. The utility of augmented reality in spinal decompression surgery using CT/MRI fusion image. Cureus. 2021, 13, :e18187. [CrossRef]

- Burström, G.; Persson, O.; Edström, E.; Elmi-Terander, A. Augmented reality navigation in spine surgery: a systematic review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2021, 163, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jud, L.; Fotouhi, J.; Andronic, O.; Aichmair, A.; Osgood, G.; Navab, N.; Farshad, M. Applicability of augmented reality in orthopedic surgery - a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020, 21, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugahara, K.; Koyachi, M.; Koyama, Y.; Sugimoto, M.; Matsunaga, S.; Odaka, K.; Abe, S.; Katakura, A. Mixed reality and three dimensional printed models for resection of maxillary tumor: a case report. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2021, 11, 2187–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, R.; Anazawa, U.; Hotta, H.; Watanabe, I.; Takahashi, Y.; Matsumoto, S. A Novel Technique of Mixed Reality Systems in the Treatment of Spinal Cord Tumors. Cureus. 2022, 14, e23096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmesallamy, W.A.E.A.; Yakout, H.; Hassanen, S.; Elshekh, M. The role of intraoperative ultrasound in management of spinal intradural mass lesions and outcome. Egypt J Neurosurg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, F.; Vetrano, I.G.; Filippini, A.; Del Bene, M.; Perin, A.; Casali, C.; Legnani, F.; Saini, M.; DiMeco, F. Intraoperative ultrasound in spinal tumor surgery. J Ultrasound. 2014, 17, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selbekk, T.; Jakola, A.S.; Solheim, O.; Johansen, T.F.; Lindseth, F.; Reinertsen, I.; Unsgård, G. Ultrasound imaging in neurosurgery: approaches to minimize surgically induced image artefacts for improved resection control. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013, 155, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.W.; Noh, S.H.; Park, J.Y.; Cho, Y.E.; Chin, D.K. Retrospective Study on Accuracy of Intraoperative Frozen Section Biopsy in Spinal Tumors. World Neurosurg. 2019, 129, e152–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.W.; Hartov, A.; Kennedy, F.E.; Miga, M.I.; Paulsen, K.D. Intraoperative brain shift and deformation: a quantitative analysis of cortical displacement in 28 cases. Neurosurgery 1998, 43, 749–58; discussion 758–60.

- Reinertsen, I.; Lindseth, F.; Askeland, C.; Iversen, D.H.; Unsgard, G. Intra-operative correction of brain-shift. Acta Neurochir 2014, 156, 1301–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, D.; Trantakis, C.; Renner, C.; Arnold, S.; Schmitgen, A.; Schneider, J.; Meixensberger, J. Application of intraoperative 3D ultrasound during navigated tumor resection. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2006, 49, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prada, F.; Del Bene, M.; Mattei, L.; Lodigiani, L.; DeBeni, S.; Kolev, V.; Vetrano, I.; Solbiati, L.; Sakas, G.; DiMeco, F. Preoperative magnetic resonance and intraoperative ultrasound fusion imaging for real-time neuronavigation in brain tumor surgery. Ultraschall Med. 2015, 36, 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyurikova, O.; Dembitskaya, Y.; Yashin, K.; Mishchenko, M.; Vedunova, M.; Medyanik, I.; Kazantsev, V. Perspectives in Intraoperative Diagnostics of Human Gliomas. Comput Math Methods Med. 2015, 2015, 479014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belykh, E.; Martirosyan, N.L.; Yagmurlu, K.; Miller, E.J.; Eschbacher, J.M.; Izadyyazdanabadi, M.; Bardonova, L.A.; Byvaltsev, V.A.; Nakaji, P.; Preul, M.C. Intraoperative Fluorescence Imaging for Personalized Brain Tumor Resection: Current State and Future Directions. Front Surg. 2016, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixidor, P.; Arráez, M.Á.; Villalba, G.; Garcia, R.; Tardáguila, M.; González, J.J.; Rimbau, J.; Vidal, X.; Montané, E. Safety and Efficacy of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid for High Grade Glioma in Usual Clinical Practice: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0149244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjipanayis, C.G.; Stummer, W.; Sheehan, J.P. 5-ALA fluorescence-guided surgery of CNS tumors. J. Neurooncol. 2019, 141, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, M.; Kulesza, B.; Stoma, F.; Osuchowski, J.; Mańdziuk, S.; Rola, R. Characteristics of Fluorescent Intraoperative Dyes Helpful in Gross Total Resection of High-Grade Gliomas-A Systematic Review. Diagnostics. 2020, 10, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacioni, S.; D'Alessandris, Q.G.; Giannetti, S.; Della Pepa, G.M.; Offi, M.; Giordano, M.; Caccavella, V.M.; Falchetti, M.L.; Lauretti, L.; Pallini, R. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (5-ALA)-Induced Protoporphyrin IX Fluorescence by Glioma Cells-A Fluorescence Microscopy Clinical Study. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takami, T.; Naito, K.; Yamagata, T.; Ohata, K. Surgical management of spinal intramedullary tumors: radical and safe strategy for benign tumors. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015, 55, 317–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucia, E.J.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Chang, S.W.; Spetzler, R.F. Surgical technique and outcomes in the treatment of spinal cord ependymomas, part 1: intramedullary ependymomas. Neurosurgery. 2011, 68(1 Suppl Operative), 57-63; discussion 63. [CrossRef]

- Ohata, K.; Takami, T.; Gotou, T.; El-Bahy, K.; Morino, M.; Maeda, M.; Inoue, Y.; Hakuba, A. Surgical outcome of intramedullary spinal cord ependymoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1999, 141, 341–346; discussion 346–347. [CrossRef]

- Goto, T.; Ohata, K.; Takami, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Nishio, A.; Morino, M.; Tsuyuguchi, N.; Hara, M. Prevention of postoperative posterior tethering of spinal cord after resection of ependymoma. J Neurosurg. 2003, 99, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenhausen, M.; Ntoulias, G.; Bodhinayake, I.; Ruppert, F.H.; Schreiber, S.; Förschler, A.; et al. Intradural spinal tumors in adults – Update on management and outcome. Neurosurg Rev. 2019, 42, 371–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giammattei, L.; Penet, N.; Parker, F.; Messerer, M. Intramedullary ependymoma: Microsurgical resection technique Neurochirurgie. 2017, 63, 398–401. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Parker, W.E.; Barzilai, O.; Bilsky, M.H. Surgical management of intramedullary spinal cord tumors Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2020, 31, 237–49. [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Barr, M.M.; Huang, K.T.; Moses, Z.B.; Iorgulescu, J.B.; Chi, J.H. Recent advances in intradural spinal tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tendulkar, R.D.; Pai Panandiker, A.S.; Wu, S.; Kun, L.E.; Broniscer, A.; Sanford, R.A.; Merchant, T.E. Irradiation of pediatric high-grade spinal cord tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010, 78, 1451–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, A.I.; Mohrhaus, C.A.; Husain, A.M.; Karikari, I.O.; Hughes, B.; Hodges, T.; Gottfried, O.; Bagley, C.A. Dorsal column mapping for intramedullary spinal cord tumor resection decreases dorsal column dysfunction. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2012, 25, 205–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wo, J.Y.; Viswanathan, A.N. Impact of Radiotherapy on Fertility, Pregnancy, and Neonatal Outcomes in Female Cancer Patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009, 73, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dea, N.; Gokaslan, Z.; Choi, D.; Fisher, C. Spine oncology‒primary spine tumors. Neurosurgery. 2017, 80(3S), S124–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purvis, T.E.; Goodwin, C.R.; Lubelski, D.; Laufer, I.; Sciubba, D.M. Review of stereotactic radiosurgery for intradural spine tumors. CNS Oncol. 2017, 6, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S Shin, D.W.; Sohn, M.J.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, D.J.; Jeon, S.R.; Hwang, Y.J.; Jho, E.H. Clinical analysis of spinal stereotactic radiosurgery in the treatment of neurogenic tumors. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015, 23, 429–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerszten, P.C.; Quader, M.; Novotny, J., Jr.; Flickinger, J.C. Radiosurgery for benign tumors of the spine: clinical experience and current trends. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2012, 11, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.; De Martin, E.; Milanesi, I.; Fariselli, L. Intradural extramedullary benign spinal lesions radiosurgery. Medium- to long-term results from a single institution experience. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013, 155, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.C.; Gorlia, T.; et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, Hau P, Brandes AA, Gijtenbeek J, Marosi C, Vecht CJ, Mokhtari K, Wesseling P, Villa S, Eisenhauer E, Gorlia T, Weller M, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Mirimanoff RO; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 459–66. [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, M.C. Temozolomide for recurrent low-grade spinal cord gliomas in adults. Cancer. 2008, 113, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaley, T.J.; Mondesire-Crump, I.; Gavrilovic, I.T. Temozolomide or bevacizumab for spinal cord high-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2012, 109, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.H.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, C.Y.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, M.M.; Choe, G.; Kim, I.A.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.J. Temozolomide for malignant primary spinal cord glioma: an experience of six cases and a literature review. J Neurooncol. 2011, 101, 247–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Menezes, A.H.; Torner, J.C. Role of resection and adjuvant therapy in long-term disease outcomes for low-grade pediatric intramedullary spinal cord tumors. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2016, 18, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, M.C. Etoposide for recurrent spinal cord ependymoma. Neurology. 2002, 58, 1310–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhrai, N.; Neophytou, P.; Dieckmann, K.; Nemeth, A.; Prayer, D.; Hainfellner, J.; Marosi, C. Recurrent spinal ependymoma showing partial remission under Imatimib. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2004, 146, 1255–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, K.A.; Afridi, S.K.; Evans, D.G.; et al. The response of spinal cord ependymomas to bevacizumab in patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017, 26, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karajannis, M.A.; Legault, G.; Hagiwara, M.; Ballas, M.S.; Brown, K.; Nusbaum, A.O.; Hochman, T.; Goldberg, J.D.; Koch, K.M.; Golfinos, J.G.; Roland, J.T.; Allen, J.C. Phase II trial of lapatinib in adult and pediatric patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 and progressive vestibular schwannomas. Neuro Oncol. 2012, 1163–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouladi, M.; Stewart, C.F.; Blaney, S.M.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Schaiquevich, P.; Packer, R.J.; Gajjar, A.; Kun, L.E.; Boyett, J.M.; Gilbertson, R.J. Phase I trial of lapatinib in children with refractory CNS malignancies: a Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28, 4221–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWire, M.; Fouladi, M.; Turner, D.C.; Wetmore, C.; Hawkins, C.; Jacobs, C.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, D.; Goldman, S.; Fisher, P.; Rytting, M.; Bouffet, E.; Khakoo, Y.; Hwang, E.I.; Foreman, N.; Stewart, C.F.; Gilbert, M.R.; Gilbertson, R.; Gajjar, A. An open-label, two-stage, phase II study of bevacizumab and lapatinib in children with recurrent or refractory ependymoma: a collaborative ependymoma research network study (CERN). J Neurooncol. 2015, 123, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kringel, R.; Lamszus, K.; Mohme, M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Glioblastoma-Current Concepts and Promising Future. Cells. 2023, 12, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.; Li, D.; Zhu, X. Cancer immunotherapy: Pros, cons and beyond. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 124, 109821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorens-Bobadilla, E.; Martin-Villalba, A. Adult NSC diversity and plasticity: the role of the niche. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2017, 42, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboody, K.S.; Brown, A.; Rainov, N.G.; Bower, K.A.; Liu, S.; Yang, W.; Small, J.E.; Herrlinger, U.; Ourednik, V.; Black, P.M.; Breakefield, X.O.; Snyder, E.Y. Neural stem cells display extensive tropism for pathology in adult brain: evidence from intracranial gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000, 7, 97:12846–51. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.23.12846. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001 Jan 16;98:777. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Cargioli, T.G.; Machluf, M.; Yang, W.; Sun, Y.; Al-Hashem, R.; Kim, S.U.; Black, P.M.; Carroll, R.S. PEX-producing human neural stem cells inhibit tumor growth in a mouse glioma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 5, 11:5965–70. [CrossRef]

- Aboody, K.; Capela, A.; Niazi, N.; Stern, J.H.; Temple, S. Translating stem cell studies to the clinic for CNS repair: current state of the art and the need for a Rosetta stone. Neuron. 2011, 70, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropper, A.E.; Zeng, X.; Haragopal, H.; Anderson, J.E.; Aljuboori, Z.; Han, I.; Abd-El-Barr, M.; Lee, H.J.; Sidman, R.L.; Snyder, E.Y.; Viapiano, M.S.; Kim, S.U.; Chi, J.H.; Teng, Y.D. Targeted Treatment of Experimental Spinal Cord Glioma With Dual Gene-Engineered Human Neural Stem Cells. Neurosurgery. 2016, 79, 481–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, Y.D.; Abd-El-Barr, M.; Wang, L.; Hajiali, H.; Wu, L.; Zafonte, R.D. Spinal cord astrocytomas: progresses in experimental and clinical investigations for developing recovery neurobiology-based novel therapies. Exp Neurol. 2019, 311, 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Tang, L.; Li, X.; Fan, F.; Liu, Z. Immunotherapy for glioma: current management and future application. Cancer Lett. 2020, 476, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, T.; Han, B.; Tan, S.; Guo, H.; Xin, Y. Immunotherapy: a potential approach for high-grade spinal cord astrocytomas. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 582828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zong, Z.; Zhang, H. Current immunotherapies for glioblastoma multiforme. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 603911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Weber, M.H.; Gokaslan, Z.; Wolinsky, J.P.; Schmidt, M.; Rhines, L.; Fehlings, M.G.; Laufer, I.; Sciubba, D.M.; Clarke, M.J.; Sundaresan, N.; Verlaan, J.J.; Sahgal, A.; Chou, D.; Fisher, C.G. Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression and Steroid Treatment: A Systematic Review. Clin Spine Surg. 2017, 30, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.T.; Nie, Y.; Sun, S.N.; Lin, T.; Han, R.J.; Jiang, J.; Li, Z.; Li, J.Q.; Xiao, Y.P.; Fan, Y.Y.; Yuan, X.H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, B.B.; Zeng, M.; Li, S.Y.; Liao, H.X.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.W. Tumor-associated antigen-based personalized dendritic cell vaccine in solid tumor patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020, 69, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsuya, K.; Akiyama, Y.; Iizuka, A.; Miyata, H.; Deguchi, S.; Hayashi, N.; Maeda, C.; Kondou, R.; Kanematsu, A.; Watanabe, K.; Ashizawa, T.; Abe, Y.; Ito, I.; Oishi, T.; Sugino, T.; Nakasu, Y.; Yamaguchi, K. Alpha-type-1 Polarized Dendritic Cell-based Vaccination in Newly Diagnosed High-grade Glioma: A Phase II Clinical Trial. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 6473–6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.N.; Huang, Y.C.; Yang, D.M.; Kikuta, K.; Wei, K.J.; Kubota, T.; Yang, W.K. A phase I/II clinical trial investigating the adverse and therapeutic effects of a postoperative autologous dendritic cell tumor vaccine in patients with malignant glioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2011, 18, 1048–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Sun, Z.; Song, D.; Cheng, Y. Targeted and intracellular delivery of protein therapeutics by a boronated polymer for the treatment of bone tumors. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 7, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirkhah, P.; Denyer, S.; Bhimani, A.D.; Arnone, G.D.; Esfahani, D.R.; Aguilar, T.; Zakrzewski, J.; Venugopal, I.; Habib, N.; Gallia, G.L.; Linninger, A.; Charbel, F.T.; Mehta, A.I. Magnetic Drug Targeting: A Novel Treatment for Intramedullary Spinal Cord Tumors. Sci Rep. 1: 8, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, D.; Zarei, M.; Rahimi, M.; Khazaie, M.; Asemi, Z.; Mir, S.M.; Sadeghpour, A.; Karimian, A.; Alemi, F.; Rahmati-Yamchi, M. ; Salehi R, Niaragh F, Yousefi M, Khelgati N, Majidinia M, Safa A, Yousefi B. et al. Preparation and in-vitro evaluation of pH-responsive cationic cyclodextrin coated magnetic nanoparticles for delivery of methotrexate to the Saos-2 bone cancer cells. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol, 2020; 57, 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, W.; Jing, D.; Yang, L.; Guo, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Pu, F.; Shao, Z. Engineered exosome as targeted lncRNA MEG3 delivery vehicles for osteosarcoma therapy. J. Control. Release. 2022, 343, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade 1 | These are the least malignant tumors and are usually associated with long-term survival. They grow slowly and have an almost normal appearance when viewed through a microscope. Surgery alone may be an effective treatment for this grade tumor. |

| Grade 2 | These tumors are slow-growing and look slightly abnormal under a microscope. Some can spread into nearby normal tissue and recur, sometimes as a higher grade tumor. |

| Grade 3 | These tumors are, by definition, malignant although there is not always a big difference between grade II and grade III tumors. The cells of a grade III tumor are actively reproducing abnormal cells, which grow into nearby normal brain tissue. These tumors tend to recur, often as a grade IV. |

| Grade 4 | These are the most malignant tumors. They reproduce rapidly, can have a bizarre appearance when viewed under the microscope, and easily grow into nearby normal brain tissue. These tumors form new blood vessels so they can maintain their rapid growth. They also have areas of dead cells in their centers. |

| Neuroepithelial tissue | |

| Paraspinal nerves | |

| Meninges | meningothelial cells mesenchymal primary melanocytic lesions other neoplasms |

| Lymphoma and hematopoietic neoplasms | |

| Germ cell tumors | |

| Metastatic tumors |

| Tumor location |

| MRI intensity, CT density |

| Enhancement pattern |

| Bone erosion |

| Accompanied findings (peritumoral cyst, edema, flow void, calcification, etc.) |

| Other study (angiography, PET, CSF study, etc.) |

| Category | meningioma | schwannoma |

|---|---|---|

| T2 weighted MR imaging | iso-low | high, heterogenous |

| Enhance | homogenous | heterogenous |

| Location | lateral | posterior |

| Cyst | - ~ + | ++ |

| Calcification | - ~ + | - |

| Tumor angle | dull | sharp |

| Dural tail | + | - |

| Mobile tumor | - | + |

| Tumor | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Ependymoma | 50-60% |

| - myxopapillary | 20-30% |

| Astrocytoma | 15-30% |

| - pilocytic | 10-45% |

| - high grade | 10-33% |

| Hemangioblastoma | 3-11% |

| Cavernous angioma | 4-5% |

| Schwannoma | 1% |

| Metastasis | 1% |

| Tumor | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Astrocytoma | 41% |

| - pilocytic | 6% |

| - high grade | 26% |

| Ganglioglioma | 27% |

| Ependymoma | 12% |

| - myxopapillary | 35% |

| Hemangioblastoma | 2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).