1. Introduction

Transporting 80 % of the world’s trade by volume, international shipping is vital to the world economy (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2022). Widespread outsourcing and an increased sophistication of logistics provisions mean that the international shipping industry has evolved to having an integral and strategic role within many global industries (Coe, 2014). But the maritime sector has significantly high levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and without new policies, they are estimated to rise significantly (Bullock et al., 2020). According to the fourth GHG study of the International Maritime Organization (IMO, 2020), international shipping emitted 1 076 million tonnes carbon dioxide equivalents a year in 2018, corresponding to some 2.89 % global GHG emissions, and such emissions could double by 2050. Oil products constitute >99 % of total energy for international shipping. In 2021 biofuels met <0.5 % of total energy demand from international shipping (International Energy Agency (IEA), 2022). Reducing the use of fossil fuels and GHG emissions of international shipping is a major challenge for the maritime sector. Achieving ambitious GHG goals critically depends on widespread deployment of low and zero carbon (LoZeC) fuels for marine propulsion (Pettit et al., 2018; IEA, 2022). All LoZeC fuels known today, such as biofuels, biogas, and renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs)[1] have different potentials, advantages, limitations and costs (Wang & Wright; 2021; Cullinane & Yang, 2022; Solakivi et al., 2022), and strong policy is needed to scale up production and use of these fuels.

In 2018, the IMO adopted an initial climate strategy for international shipping, aiming to reduce carbon intensity of ships by at least 40 % by 2030 and 70 % by 2050. Total emissions shall be cut by at least 50 % by 2050, compared to 2008 (IMO, 2018). To complement the strategy, IMO (2021) adopted a set of short-term measures including mandatory goal-based operational and technical requirements. The IMO initial strategy was widely criticized for lacking high ambitions (Doelle & Chircop, 2019; Joung et al., 2020; Rayner et al., 2021; Bullock et al., 2022; Leeuwen & Monios, 2022; Bach & Hansen, 2023), and the IMO climate strategy was revised in 2023, setting a net-zero emissions target by mid-century and interim targets for 2030 and 2040 (IMO, 2023). This criticism and the slow progress in IMO motivated EU policymakers to act unilaterally and present and adopt EU policies for decarbonizing shipping (Wettestad & Guldbrandsen, 2022; Vogler, 2023). After two years of negotiations, the co-legislators of the EU, the Council of the EU (Council) and the European Parliament (EP), agreed on the FuelEU Maritime (FEUM) regulation to stimulate the uptake of LoZeC fuels in maritime transport (EU, 2023a), and to include of shipping in the EU emissions trading system (EU ETS) (EU, 2023b).

This paper aims to critically analyse the policy process and politics in the EU on decarbonizing maritime shipping. It focuses on FEUM, a highly interesting case of decarbonization and clean energy transition to reach the EU target of climate neutrality. It is the first legislation ever for stimulating uptake of LoZeC fuels and decarbonizing maritime shipping. It represents a policy domain with several vested interests and nested policy domains, e.g., climate policy, energy policy, transport policy, industry policy, innovation and technology policy, agricultural policy and forestry policy (Urban et al., 2024), providing insights on variety of interests from politics, business and civil society. Analysing policy does not only include effects and effectiveness, but the narratives, discourses and argumentation attached to meaning making and framing of problems encountered in society, different policy options and the ambiguities of policymaking (Hajer, 1995; Dryzek, 2007; Lynggaard, 2019). As discussed by von Malmborg (2023a, 2024a), EU politics on decarbonizing shipping is an argumentative struggle in which actors try to make others see the problem and policy solution according to their views and seek to position other actors in a specific way. To understand policies for decarbonizing maritime shipping, such as FEUM, one must understand the meanings and politics of the policy (cf. Cairney, 2023). Such analysis could further our understanding of the politics of the clean energy and just transition more broadly (cf. Kuzemko et al., 2019; Bressand & Ekins, 2021; Pearse, 2021). There are only few studies on the politics related to the decarbonization of maritime shipping (e.g., Earsom & Delreux, 2021; De Beukelaer, 2022, 2023; Wettestad & Guldbrandsen, 2022; Vogler, 2023; von Malmborg, 2023a, 2024a, 2024b), but none analysing in-depth how different policy actors engage in giving meaning to the concept of ‘decarbonizing maritime shipping’ as a basis for adopting legitimate policies. This paper aims at filling this research gap. Applying argumentative discourse analysis (Hajer, 1995) in combination with theory on discursive interaction strategies and discursive agency (Dewulf & Bouwen, 2012; Lynggaard & Triantafillou, 2023), tapping the conversation on decarbonizing maritime shipping, this paper analyses the following research questions:

How did the meaning decarbonizing maritime shipping evolve?

What storylines and discourses framed the policy debate?

What conflicts and coalitions were present in the policy debate?

How did different policy actors interact and communicate to agree to structure and institutionalize a common discourse that could frame a broadly legitimate policy in a landscape of competing discourses?

2. Research on Policy for Decarbonizing Maritime Shipping

A complex set of political, institutional, organizational, structural, behavioural, market and non-market failures constitute barriers to decarbonization of international shipping (Rayner, 2021; Dyrhauge & Rayner, 2023). For instance, split incentives between ship-owners and hirers decreases owners’ motivation to invest in solutions benefiting others. In addition, investors tend to be risk averse. Many banks have reduced their ship financing commitments, restricting access to capital and credit necessary for technology retrofits. Finally, interests of incumbent players represent a huge political challenge for decarbonizing shipping, as in decarbonization in general (Nasiritousi, 2017; Overland, 2018; Paterson & Laberge, 2018; Bressand & Ekins, 2021; Newell et al., 2021; Paterson, 2021). They refer to high costs of alternatives to fossil fuels and long lifetimes of investments in ships as well as concerns of global competitiveness of the EU shipping industry that could face costly transitions, why they prefer global policy under IMO rather than EU policy (Dyrhauge & Rayner, 2023). Incumbent shipping companies, shipping trade associations and the fossil fuel industry often accept the need to deliver a ‘fair share’ of GHG emission reductions but insist that policy instruments must not inhibit economic growth (Rayner et al, 2021).

Steen et al. (2019) and Bergek et al. (2021) argue that different LoZeC technologies have different advantages and disadvantages making them suitable for different sector segments, why there is a need for segment specific policies. Harahap et al. (2023, p. 11) argue that a “combination of demand pull-types of instruments, technology-push instruments, and fiscal policies are essential to meet the net-zero emissions in the shipping sector”. Bach et al. (2020, p. 16) argue more specifically for the need of “further funding possibilities, market stimulation measures, development of educational policies, and creation of further synergies between the [technological innovation systems for different LoZeC fuels]”. It is particularly important to uphold and further strengthen climate policy to create incentives for production and uptake of LoZeC technologies (Bach et al., 2020). Various states and organizations at the IMO have proposed market-based measures (MBMs) as a cost-effective solution to reduce GHG emissions from international shipping (Leeuwen & Koppen, 2016; Shi, 2016; Lagouvardou et al. 2020; Psaraftis et al., 2021). Leeuwen and Koppen (2016) argues that how companies respond to economic stimuli generated by MBMs depends on the kind of environmental strategy they employ. They conclude that incumbents in the shipping sector is mostly crisis-oriented, meaning that staying within compliance is the main ambition. The cost-inducing fee-based or cap-and-trade based MBMs that are considered by IMO fit well with this crisis-oriented focus. This potential will be much larger when the MBMs are able to support a change to a process-oriented strategy. Finally, Leeuwen and Koppen (2016) argue that more needs to be done by governmental actors, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and cargo-owners to move ship owners to a process-oriented strategy, i.e., facilitating investments to develop preventive technologies, raising awareness of end-consumers and supporting information-based MBMs that improve corporate branding and market access. De Beukelaer (2022, 2023) analysed the political economy of the potential re-uptake of wind propulsion to decarbonize shipping, finding that full decarbonization requires a combination of technological innovation and reduced demand of transport services, whereby he joins the ‘sufficiency’ school of climate governance (Sorrell, 2015).

There is a small but increasing body of literature on policy processes for decarbonizing maritime shipping, none so far using discourse analysis. Focusing on influential actors in IMO climate governance, Earsom and Delreux (2021) analysed to role of the EU in the negotiations on the IMO initial climate strategy. They found that the EU’s goal achievement was the result of a mechanism triggered by (i) its overarching objective for action in the IMO on GHG emissions in international shipping, (ii) an entrepreneurial coalition partner sharing the same goals; and (iii) mounting momentum for action in the IMO. The leadership of the EU in forming international environmental agreements has attracted attention among scholars (Kalfagianni & Young, 2022). The EU holds normative power, but concerns are raised about its leadership being perceived as a form of soft imperialism by other states, particularly in the Global South (Afionis & Stringer, 2014). The same holds true for tensions between internal policy coherence and the EU’s aspiration to exercise global environmental leadership. Credibility is essential to enhance persuasion. Vogler and Stephan (2007) argue that for the EU to be able to convince others to follow its lead, it needs to live up to its own high standards of environmental protection. The European Green Deal presented by the European Commission (EC) in 2019 (EC, 2019), and the subsequent adoption of FEUM and the inclusion of shipping in EU ETS in 2023 (EU, 2023a, 2023b), are means for the EU to show such ‘exemplary leadership’ (Tobin et al., 2023; von Malmborg, 2024a). Also focusing on influential actors, von Malmborg (2024a) analysed the strategies of the EC and Transport & Environment (T&E), the European confederation of green mobility NGOs, as policy entrepreneurs in the policy process leading to the adoption of FEUM. Through extensive coalition-building and successful problem and policy framing, T&E gathered enough support to stand the grounds against heavy lobbying from incumbents and raise the ambition of the FEUM regulation. In a related study, von Malmborg (2023a) identified two advocacy coalitions in the policy process on FEUM, one stalling policy change and one advocating disruptive change. The co-legislators reached consensus on a middle-ground after negotiations in a bargaining mode. Negotiations through bargaining instead of deliberation hampered policy learning across the two coalitions (von Malmborg, 2024b).

In all, previous research on the political economics and policy on decarbonization of shipping indicates a need for strengthened climate policy and a mix of policy instruments, including segment/technology specific measures, to overcome different barriers. Crisis-oriented incumbents are stalling change, while more process-oriented, progressive companies could help push forward the decarbonization. In the case of FEUM, different coalitions with different views and narratives about the problem and suitable solutions competed in an argumentative struggle for monopoly of their views as the basis for how to design the legislation. How a problem and solution is framed and building of coalitions have big impact on acceptance among legislators. This research tells us about different arguments, but not how different policy actors interacted and argued for their cases. This paper will fill that research gap.

3. Discourse Analysis

Simply put, politics is about translating values into narratives about problems and viable policy solutions, which are further developed and concretized into political proposals on goals, strategies and policy instruments. These are situated within discursive frames, i.e. cognitive and normative structures that affect and limit social actors (Lynggaard, 2019). Discursive framing is central to politics and the policy process, i.e. the process of public policy and the complex interactions involving people and organizations, events, contexts and outcomes over time (Dryzek, 1997; Weible, 2023).

Discourse analysis has become widely accepted for analysing policy, also environmental policy. Hajer (1995) and Dryzek (1997) presume that discourses facilitate and hinder political entities’ and societies’ understanding and action on certain social or physical phenomena negotiated in policymaking. Discourse analysis ‘offers a reflexive understanding of “the political” and transforms the practice of environmental] policy analysis’ (Feindt & Oels, 2005, p. 169). Discourse analysis has been used increasingly to analyse EU politics (Howarth & Torfing, 2005; Lynggaard, 2019), including EU environmental, energy and climate politics (Machin, 2019; Bressand & Ekins, 2021; Dunlop, 2022; von Malmborg, 2023b).

Most discourse analytical approaches assume that our conceptions of ‘real-world’ phenomena is constructed through processes of social meaning-making, which rely on the use of language as well as social practices (Foucault, 1973; Laclau & Mouffe, 1985; Hajer, 1995; Schiffrin et al., 2001; Keller, 2012). The use of discourse analysis in political science has been influenced by a variety of philosophical and disciplinary traditions, partially translated into analytical approaches, e.g., Discourse Theory (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985), Argumentative Discourse Analysis (Hajer, 1995), Deliberative Discourse Analysis (Dryzek, 1997), Sociology of Knowledge Approach to Discourse (Keller, 1998). Featuring many applications to the environmental policy domain but less so in the energy or transport policy domains, these approaches all focus on discourses related to policymaking (Keller & Poferl, 2011). These approaches presume that discourses facilitate and hinder how political entities and societies understand and act on certain social or physical phenomena that are negotiated in environmental or energy policymaking.

Studies of environmental policy discourses are mostly based on approaches focusing on sociocultural meaning structures (Feindt & Oels, 2005; Hajer & Versteeg, 2005; Leipold et al., 2019), acknowledging that environmental problems are social constructs. These meaning structures are reached by identifying the properties of text, speech or the symbolic aspect of actions, often related to a specific problem area, such as climate governance (Oels, 2005; Bäckstrand & Lövbrand, 2019) or overall structures of environmental policy such as ecological modernization (Machin, 2019). Concepts such as ‘decarbonization’ and ‘maritime decarbonization’, analysed in this paper, are constantly disputed in a struggle for knowledge, interpretation, meaning and implementation.

In this study, argumentative discourse analysis (ADA) is used in combination with theory on discursive interaction strategies (Dewulf & Bouwen, 2012) and discursive agency (Lynggaard & Triantafillou, 2023). The reason to choose ADA is that it was developed to study environmental policy. The phrase argumentative discourse analysis is derived from the suggestion that it is better to speak of an argumentative turn than a linguistic turn. In ADA, analysis goes beyond the investigation of different interpretations of (technical) facts alone. The challenge for ADA is to find ways of combining analysis of the discursive production of ‘reality’, with analysis of the socio-political practices from which social constructs emerge and in which actors are engaged. ADA is based on three interrelated elements: discourse, practices and meaning. The allocation of meaning in each context is thus analysed in terms of particular forms of discourse within the context of the particular practices in which the discourse is produced. Hence ADA is not simply about analysing arguments -– it is much more about analysing politics as a play of ‘positioning’ at particular ‘sites’ of discursive production (Hajer, 2002). ADA includes several conceptual tools that facilitate empirical research: discourse, storyline, discourse coalition, discourse structuration, and discourse institutionalization. All are intended to overcome static gaps between individuals and institutions and therefore aim to understand how interrelationships are constantly produced, reproduced, challenged, and transformed.

Hajer (1995, p. 44) defines discourses as “a specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorizations that are produced, reproduced, and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities”. These patterns determine the understanding of specific practices and events in the policy process. They are fundamental to the formation and expression of political truth claims, engagement in, and the self-positioning of individuals and collectives for or against policy change (Fischer, 2003; Leipold & Winkel, 2017).

The concept of storyline is a key concept in discourse analysis. They are narratives on social phenomena that play a significant role in clustering of knowledge, positioning of actors and creation of coalitions among the actors within a given policy domain (Hajer, 1995, 2002; Hajer & Versteeg, 2005). They are the means through which different elements of physical and social phenomena are united into specific, closed problems and given meaning. Discourse coalitions comprise sets of storylines, the actors who adhere to and articulate such storylines, and practices that are consistent with the storylines. Unlike advocacy coalitions, which are based on collaboration of actors with shared beliefs (Jenkins-Smith et al., 2018), ‘discourse coalitions are not necessarily based on shared interests and goals, but rather on shared terms and concepts through which meaning is assigned to social and physical processes and the nature of the policy problem under consideration is constructed’ (Hajer, 1996, p. 247). Building on Foucauldian discourse theory, Hajer assumes that it is neither possible nor analytically necessary to deduce ‘beliefs’ (a mental/actor-centred category) from discursive events and patterns. Discourse coalitions are formed on shared narratives which are articulated in a condensed form through storylines. What is more, Hajer (1995, 1996) argues that actors with different beliefs might build a single discourse coalition in case they are able to articulate their distinct perspectives within the same narrative/storyline.

When policy actors frame the meaning of an issue in diverging terms, they must deal with this difference in further conversation. Hajer (1995, 2002) argues that interdiscursive communication can create new meanings and new identities and help overcome dualities between conflicting discourses for the discourses to frame a new or change an existing policy. Interdiscursive communication may alter cognitive patterns and create new cognitions and new positionings. Hence, it fulfils a key role in processes of political change. Unless a discourse is hegemonic, meaning socially or culturally predominant in the policy debates, no actor usually fully controls the policy process or can impose single-handedly its preferred framing. Discursive hegemony is achieved through discourse structuration, whereby the storylines and agents of a discourse coalition achieve coherence and credibility, and discourse institutionalization, where the concepts articulated by a discourse coalition come to be acted on within the policy process and replace previous understandings of the issue (Hajer, 1995; Bulkeley, 2020). Discourse institutionalization may be achieved by drawing on resources such as knowledge, legitimacy, power, and demonstration of material benefits. Only in favourable circumstances can policy entrepreneurs or policy brokers with key positions in the policy process change the dominant policy image and foster institutional change (Anderson et al., 2020). Policy entrepreneurs can use different discursive interaction strategies for discursively (re)framing the policy, e.g., frame incorporation, frame disconnection, frame polarization, frame accommodation, and frame reconnection (Dewulf & Bouwen, 2012), or different discursive agency strategies (Lynggaard & Triantafillou, 2023).

Drawing on the notion of interdiscursive communication, discourse analysts have recently come to focus on discursive agency (Leipold & Winkel, 2017; Lynggaard & Triantafillou, 2023). Leipold and Winkel (2017, p. 524) define discursive agency as “an actor’s ability to make him/herself a relevant agent in a particular discourse by constantly making choices about whether, where, when, and how to identify with a particular subject position in specific story lines within this discourse”. Lynggaard and Triantafillou (2023) propose three general types of discursive agency: (i) manoeuvring within a given discursive framework, (ii) navigating between different and conflicting discourses, and (iii) transforming existing discourses. They also propose seven strategies for discursive agency that policy actors can use in relation to the general types: (i) normative power, (ii) manipulation, (iii) exclusion, (iv) multiple functionality, (v) vagueness, (vi) rationalism, and (vii) securitization. In discourse manoeuvring, policy actors can use normative power to ‘propagate policy change or stability by strict reference to the normative power of existing hegemonic discourse”, or manipulation to “consolidate existing policy by pretending paradigm change’ (Lynggaard & Triantafillou, 2023, p. 1941). In discourse navigation, policy actors can use exclusion to ‘argue that one discourse is more legitimate than another’, multiple functionality to ‘argue that a policy must accommodate legitimate (but conflicting) discourses’, and vagueness to ‘’ropagate a policy change by general and vague articulations of discourse(s) downplaying discursive conflicts”. Finally, in discourse transformation, a policy actor can use rationalism to ‘invoke novel scientific ideas and findings to challenge and reform an existing policy and discourse’, or securitization to ‘propagate policy change based on another discourse than the hitherto hegemonic one to address a threat to polity survival’. How policy actors decide on which of the seven discursive agency strategies to engage in to influence policy depends on the discursive situation.

4. Methodolgy

4.1. Argumentative Discourse Analysis

To analyse the discourses and discursive agency related to FEUM, a case study approach was used (Yin, 1994). This approach is suitable because the research problems are qualitative in nature. As for discourse analysis, I will use Hajer’s (1995) Argumentative Discourse Analysis (ADA). The reason to choose ADA is that it was developed to study environmental policy and focus on argumentation rather than arguments. As mentioned, previous studies indicate that EU politics on decarbonizing maritime shipping is an argumentative struggle between different actors with competing views on problems and appropriate policy design (von Malmborg, 2023a, 2024a). Taking the idea of a social construction of social and physical phenomena seriously, it is not individuals or organizations that are subject to in-depth analysis as the practices in which they engage. Thus, an emphasis on the argumentative dimension refers not so much to the analysis of the noun ‘argument’ as to the verb to ‘argue’ (Hajer, 1995, 2002). While the analysis of arguments could very well have been done within the framework of more traditional approaches to discourse analysis, ADA tracks how people position each other through language use or how they are positioned through commonly used discourses (Hajer, 2002; Hajer & Versteeg, 2005; Cotton et al., 2014). Of course, people can also be quite literally framed by discourse, but the poststructuralist orientation of discourse analysis emerges here in the assumption that this always happens through (re)creation of special relationships. A characteristic of ADA is that it has a strong empirical focus and attempts to shed light on many mechanisms that come into play that produce specific political ‘realities’. Policy discourses pull together a multitude of actors with their own legitimate perspectives and modes of talking or engaging in an issue, and the ADA aims to uncover these relationships. In practice, the ADA draws out the embedded contextual factors in which policy strategies emerge by focusing upon the linguistic strategies that actors mobilize in public dialogue over environmental decision-making.

4.2. Notes on Material and Data Analysis

The study focuses on politics, discourses and discursive agency in supranational policymaking in EU. Thus, it analyses storylines, discourses and discourse coalitions including actors at different levels of EU policymaking, i.e. the EC as agenda-setter, the Council and the EP as co-legislators, the governments of 27 member states (MSs) as the ones representing MSs in Council negotiations, companies, business associations, environmental organizations, think tanks and other interest groups (IGs). This approach is justified by the fact that they are all part of the multilevel governance setting of policymaking processes in the EU as a polity (Hooghe & Marks, 2001; Bache & Flinders, 2004; Hix, 2007). Many studies of coalitions in the EU exclude the EC, MSs, the Council and the EP, and focus on coalitions of IGs only. This gives knowledge about the ones trying to influence the decision-makers, but it tells little about storylines, discourses and coalitions among the actors that finally decides on EU policy. Thus, it is relevant to include the EC, the Council and the EP as they often ‘speak’ for different discourse coalitions in the final negotiations. It is also relevant to include the governments of MSs since they are the ones that should transpose EU law into national legislation and are actively influencing the EC, the EP and other MSs in the Council. MSs constitute the Council, one of the co-legislators. However, narratives and storylines of a MS government are often the results of national negotiations and can change with the next election, which can be held during an ongoing negotiation. The case is similar for the EP, where negotiations take place between party groups and committees, and elections are held every fifth year. As an example, the EP has been strong on climate policy the last decades (Wettestad et al., 2012; Dupont et al., 2023), but there is increasing support for climate deniers in the upcoming EU elections in spring 2024. The European far right is negatively polarizing and currently waging a ‘cultural war’ on ambitious EU-level climate policies (Cunningham et al., 2024). The top candidate of far-right Sweden Democrats in the 2024 EU elections has told he want to repeal the European Green Deal (EGD) (EC, 2019) and Fit for 55 climate package (EC, 2021a).

The EP consists of 705 Members of the EP (MEPs), belonging to seven party groups.[2] MEPs are elected every five years. The last elections to the EP were held in spring 2019, with EPP as the largest party (24.2 %), S&D (20.5 %) in second place, followed by Renew Europe (14.4 %) and the Greens/EFA (9.9 %). The president and commissioners of the EC are usually former national ministers appointed for five-year terms. The governments of EU MSs and the EP approved the current president of the EC Ursula von der Leyen (Germany, conservative) and the commissioners, including transport commissioner Adina Vălean (Romania, national liberal), in autumn 2019. They entered office in November 2019.

Data was collected using a mixed method approach combining qualitative text analysis and semi-structured interviews. As for texts, data was collected from official and confidential documents presenting positions of different policy actors (

Table 1), such as (i) policy papers from the EC (Directorate-General for Transport (DG MOVE), (ii) positions of the Council and member states (MS), (iii) positions of the EP and its party groups and committees, (iv) reports and policy papers from T&E as policy entrepreneur on FEUM, (v) stakeholders’ responses to the public consultation on FEUM and stakeholders’ position papers, and (vi) editorials, open editorials and articles in newspapers and magazines. In all, 83 text documents and one online conference video were analysed.

Decision-making in the Council and in the tripartite inter-institutional negotiations between the Council, the EP and the EC (trilogues) is secluded (Reh et al., 2013; Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, 2021) and most research on EU policy draws on voting results in the Council and the EP since it is hard for scholars to get access to the negotiations. In this study, collaboration with the Swedish Ministry of Infrastructure, responsible for transport policy, provided the possibility to get access to reports on negotiations in the Council shipping working party and trilogues sent by Sweden’s Permanent Representation to the EU to the Ministry of Infrastructure. Getting access to Sweden’s reports is relevant since Sweden held the Council Presidency during final trilogue negotiations on FEUM and was the one making the deals with the EP on behalf of the 27 MSs in the Council. Such sharing of confidential information for research purposes is generally very rare (Lundgren et al., 2022). These provided a unique opportunity to analyse positions and changes in positions as well as the argumentation of different actors and the co-legislators during negotiations in the Council and the trilogues. This is a methodological merit, which gives possibilities to analyse in more detail the argumentation and discursive agency of different actors. I judge the likelihood that the findings based on Sweden’s reports would be systematically affected by bias to be limited. Swedish officials’ reporting from the meetings should have no incentives to falsely convey the positions of other EU MSs, the EC or the EP to the Government Offices of Sweden, since those positions are used to formulate Swedish negotiation strategies in the Council, and negotiation strategies in the trilogue negotiations as Council Presidency.

To identify views and narratives of companies, business associations, environmental organizations and think tanks, in addition to those mentioned in the EC public consultation and position statements, searches were made using Google. Searches were made for ‘fueleu+maritime’, ‘shipping+decarbon*’, ‘maritime+decarbon*’, ‘shipping+decarbon*’, ‘fueleu+maritime+compan*’, ‘fueleu+maritime+ngo’, ‘electrofuels+eu’, and ‘rfnbo+eu’.To get a better understanding of positions and narratives of key actors in the policy process, but more particularly the argumentative turns and discursive agency of these actors, the qualitative text analysis was complemented with five interviews with key individuals at the most important organizations in the case, the EC, T&E, the EP and the Council (

Table 2). The EC and T&E where the main architects, the policy entrepreneurs, behind the competing proposals in the policy process on FEUM (von Malmborg, 2024a). In addition to interviews with these actors, interviews were also held with representatives of the Council and the EP as co-legislators. These were the transport attaché of Swedish Presidency of the Council, and the lead political assistants of the EP rapporteur on the FEUM file. These two persons were spokespersons for the Council and the EP at ‘technical’ level and key in the inter-institutional negotiations between the Council and the EP, as most negotiations were held at this level. They provided the political lead negotiators with technical, strategic, and tactical policy advise for the political negotiations leading to agreement and adoption of the FEUM regulation. The EP and the Council are the co-legislators in the EU, and the ones that must reach consensus on a policy. The Swedish transport attaché also acted as chair of the Council transport working group during final trilogue negotiations, consolidating positions of MSs.

The qualitative text analysis of the written and audiovisual material was done manually and searched for views and narratives of various policy actors (mainly as collectives) on decarbonization of shipping, alternative shipping fuels, RFNBOs, electrofuels, policy design related to the FEUM regulation. What problem framing and policy options did the EC propose and what were the justifications for these proposals? What were the responses and counterproposals presented by the governments of different MSs, the Council as an institution, the EP rapporteur and the EP as an institution, and different IGs? Did the views and storylines change during the policy process?

First, data was coded as storylines. Actors’ views and narratives on problems, including levels of emission reductions required, were consolidated and categorized as problem storylines (PROB1–PROB4). Views and narratives on scope of the policy, and overall approaches to and design elements of policies were consolidated into different storylines and categorized as policy storylines related to the specific policy domain (POL1–POL10). Maturity was reached when no more new or contradictory views or narratives were identified to add to existing storylines or constitute new ones. In general, narratives and storylines on policies were related to specific design elements of policies. Dichotomies of narratives and storylines were grouped as lines of dispute in two dimensions related to the emergency of the problem, and the associated need for stronger or weaker policy, making it possible to group storylines into discourses. Storylines related to wide scope and radical change are considered to advocate stronger policy, while storylines related to narrow scope and incremental change are considered to advocate weaker policy. The policy actors were then plotted in a matrix using a mix of clustering and storylines as relations (Weible & Workman, 2022) to find out who shared storylines and who belonged to different discourse coalitions.

Since both FEUM and EU ETS shipping addresses GHG emission reductions not only for intra-EU voyages, but also all extra-EU voyages to and from ports of call in third countries, it could be expected that third country shipping companies and third countries would have made attempts to influence EU policy. No official documents indicating such advocacy was found, but the Commission mentions that some international players were critical towards including extra-EU shipping in EU ETS (EC, 2021e). No initiatives of advocacy from third countries were directed towards the Swedish Presidency during the trilogues. In the report of the EP rapporteur[3] on FEUM (Warborn, 2022) and the final report from the EP on FEUM (EP, 2022), all organizations which have provided input are listed. All of these, except World Shipping Council (WSC), were European IGs and companies. The responses to the EC public consultation (EC, 2021f) mainly came from EU citizens and organizations. Out of 136 responses, 18 came from companies, IGs and academics outside the EU, half of which came from the UK. Other countries represented were Norway, the United States, Türkiye, Hong Kong, Switzerland, Canada, and Brazil. In addition, several international environmental NGOs (ENGOs) were active in the policy discussions, collaborating with T&E. These are all included in the analysis. This said, the views, narratives and storylines identified, and the composition of discourse coalitions could look different if more secluded advocacy of third countries and third country organizations could be identified.

5. EU Policy for Decarbonizing Maritime Shipping

Shipping is a key sector for the EU economy. About three quarters of all international trade in and out of the EU is carried by sea (European Maritime Safety Agency, 2023), and the sector contributes with EUR 149 billion to EU gross domestic product and two million jobs in 2020, of which 685,000 at sea (Oxford Economics, 2020). The EU fleet consists of 23,400 vessels and constitutes 39.5 % of the world fleet. The European shipping industry is diversified and includes transportation of goods by sea, transport of people by sea, service, and offshore support vessels, and towing and dredging at sea. Freight transport, including towing and dredging (53 %) followed by passenger transport (37 %) are the two largest segments regarding employment (Oxford Economics, 2020).

Indicators showed that rising GHG emissions from maritime shipping is problematic. The EU shipping sector emitted 138 million tonnes carbon dioxide in 2018, corresponding to some 11 % of all EU transport carbon dioxide emissions and 3–4 % of total EU carbon dioxide emissions (EC, 2021c). The GHG emissions from EU maritime transport (i.e., emissions related to intra-EU routes and incoming and outgoing routes), increased by 48 % between 1990 and 2008 (EC, 2013). In the same period, total GHG emission in the EU decreased by 11 % why the share of emissions from shipping rose. EU-related emissions from shipping are expected to further increase by 51 % by 2050 compared to 2010-levels if no policy instruments are adopted. This can be compared to the EU target of net-zero emissions by 2050. According to the European Commission (2021c, 2021e), the current fuel mix in the maritime sector is made up of >99 % fossil fuels. This is due to insufficient incentives for operators to reduce GHG emissions and a lack of mature, affordable, and globally utilisable alternatives to fossil fuels in the sector.

The issue of decarbonizing the EU maritime sector entered the EU policy agenda with the 2013 strategy for integrating maritime transport emissions in the EU’s GHG reduction policies (EC, 2013). However, prior to FEUM and the inclusion of shipping in EU ETS in 2023, international shipping was the only mode of transport not included in the EU’s commitment for GHG emissions reductions (Dyrhauge & Rayner, 2023). In the 2013 strategy, the Commission proposed a three-staged approach:

Requirements for ships to monitor, report and verify GHG emission,

Setting a GHG target for shipping, and

Introduce policy instruments to reach the target.

The first stage included establishment of the EU regulation on monitoring, reporting and verification of emissions of additional GHGs and emissions from additional ship types, first adopted in 2015 and revised in 2023 (EU, 2023c). The second stage included the indicative target to reduce GHG emissions from the transport sector by 90 % by 2050, included in the Climate Target Plan (European Commission, 2020).

The third step was the proposal in the Fit for 55 package to establish the FEUM regulation (2021b) and include shipping in EU ETS (EC, 2021d), both adopted in 2023. This step was part of implementing the EGD, which was presented in December 2019 by the newly instated President of the EC, Ursula von der Leyen, as a response to the climate and environmental challenges facing the world, manifested in the United Nations Paris Agreement on climate change. The EGD is EU’s climate plan and green growth strategy up to 2050. As part of EGD, a new European Climate Law (ECL) was adopted in July 2021 (EU, 2021), stating that EU greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions shall be reduced by 55 % by 2030, and that the EU will be climate-neutral by 2050. To realize these targets, EC presented in July 2021 a broad legislative package to make EU legislation Fit for 55 (EC, 2021a). As for EU ETS and FEUM, the purpose was to make maritime shipping contribute to reaching EU’s new climate targets by setting a price on GHG emissions from maritime shipping and requiring the shipping sector to use low and zero-carbon fuels and reduce GHG emissions, (EC, 2021b, 2021c).

After a combination of deliberative negotiations and bargaining, the Council and the EP reached a political agreement on FEUM on 23 March 2023 (von Malmborg, 2023a, 2024a). FUEM was formally adopted by the EP and the Council in July 2023 (EU, 2023), establishing the world’s most ambitious legislation to stimulate deployment of LoZeC fuels and decarbonizing maritime shipping, beyond the borders of the EU. In short, FEUM provides that:

GHG intensities from shipping well-to-wake[4] should be reduced by 2 % from 2025, 6 % from 2030, 14.5 % from 2035, 31 % from 2040, 62 % from 2045 and 80 % from 2050,

A multiplier of 2 can be applied when using renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs)[5] to reduce GHG emission intensities. A sub-quota of 2 % for RFNBOs will be adopted by 2034, if an EC’s analysis of the RFNBO market shows that a multiplicator is not enough to drive market development beyond 1 % in the fuel mix by 2031,

ships moored at the quayside in a port of call in an EU member state (MS) shall connect to on-shore power supply and use it for all its electrical power demand at berth, unless they can demonstrate that they use an alternative zero-emission technology, and

If these requirements are not met, ships shall pay a penalty. Revenues from penalties shall be allocated to the MSs, for use to support rapid deployment and use of renewable and low-carbon fuels in the maritime sector, given that they report every five years to the EC.

These requirements apply to ships above 5 000 gross tonnage[6] and encompass 100 % of their intra-EU voyages and 50 % of their voyages between EU ports of call and ports of call located in third countries.

6. Storylines and Argumentation

The following subsections present the storylines and argumentations identified related to problem framings and related framings of policy options of different policy actors. How a condition is framed as a problem influences how we think about the problem (Knaggård, 2015). This enables coupling to certain policies, but not to others (Herweg, 2016). As summarized in

Table 3, this case identified 14 storylines, four on the problem framing (PROB1–PROB4) and ten on policy framing (POL1–POL10). They evolved in a dialectic conversation. Taken together, they constitute two competing discourses (see section 7), providing two different meanings of ‘decarbonizing maritime shipping’. The main lines of conflict in the negotiations between the co-legislators related to the framing of the problem (including competitiveness, levels of emission reductions and views of maritime fuels), the basic nature of the policy instrument (technology neutral or technology specific), and the allocation of revenues from penalties. Storylines and argumentation related to these elements are presented and discussed in the following sub-sections.

Views also differed on addressees and scope of the regulation, but these were not as decisive for the design of the FEUM regulation and easily reconciled. For instance, the EU regulation on monitoring, reporting and verification of GHG emissions from ships does not include ships below 5,000 gross tonnage. Thus, there is no legal basis – at the moment – to include smaller ships in FEUM. The situation was identical for the introduction of shipping in EU ETS. Sentiments for taking account for national/regional conditions was found not only in the Council, but also in the EP and was easily resolved, which rendered some temporal exemptions.

6.1. Problem Framing

All policy actors agreed that the main aim of the FEUM regulation was for the shipping sector to contribute to meeting the EU target on climate neutrality by 2050. However, views differed on nature and urgency of the problem and thus to what extent GHG emissions should be reduced to 2050 and interim checkpoints in 2030, 2035, 2040 and 2045.

According to the EC and incumbents in the maritime and fossil fuel industries, climate change is a threat to our economies and all sectors must reduce emissions, but competitiveness and economic growth must not decrease. EU policy on decarbonization of shipping must consider the fact that maritime transport services in EU and between EU and third countries can be provided by operators of all nationalities. The global nature of the sector underlines the importance of flag neutrality and a favourable regulatory framework, which would protect the competitiveness of EU ports, ship owners and ship operators (ECSA & ICS, 2021). A level playing field for ship operators and shipping companies in terms of levelized costs for shipowners and ship operators is critical to a well-functioning EU market for maritime transport (EC, 2021b). This implies that not only intra-EU voyages should be covered by EU policy, but all ships making port calls in the EU. The need for a level playing-field was not disputed in the policy domain, but views differed on what is meant with ‘competitiveness’.

In its Climate Target Plan (CTP), EC argued that a 90 % reduction in transport sector GHG emissions is needed by 2050 to achieve economy wide climate neutrality by 2050 (EC, 2020). All transport modes, including shipping, will have to contribute to the efforts. The necessary technology development and deployment should happen already by 2030 to prepare for much more rapid change thereafter. In its proposal for the FEUM regulation, EC (2021c, p. 1) argued that “renewable and low-carbon fuels should represent 6–9 % of the maritime transport fuel mix in 2030 and 86–88 % by 2050 to contribute to the EU economy wide GHG emissions reduction targets.” An important framing condition for the EC was that the costs of LoZeC fuels are high and will remain high for decades, and that current supply is limited. Stimulating further innovation for decarbonizing maritime shipping through lower costs of alternative fuels will keep its competitiveness; both at global level by ensuring the operation of trade links, and at EU level through continuous quality leadership (EC, 2013).

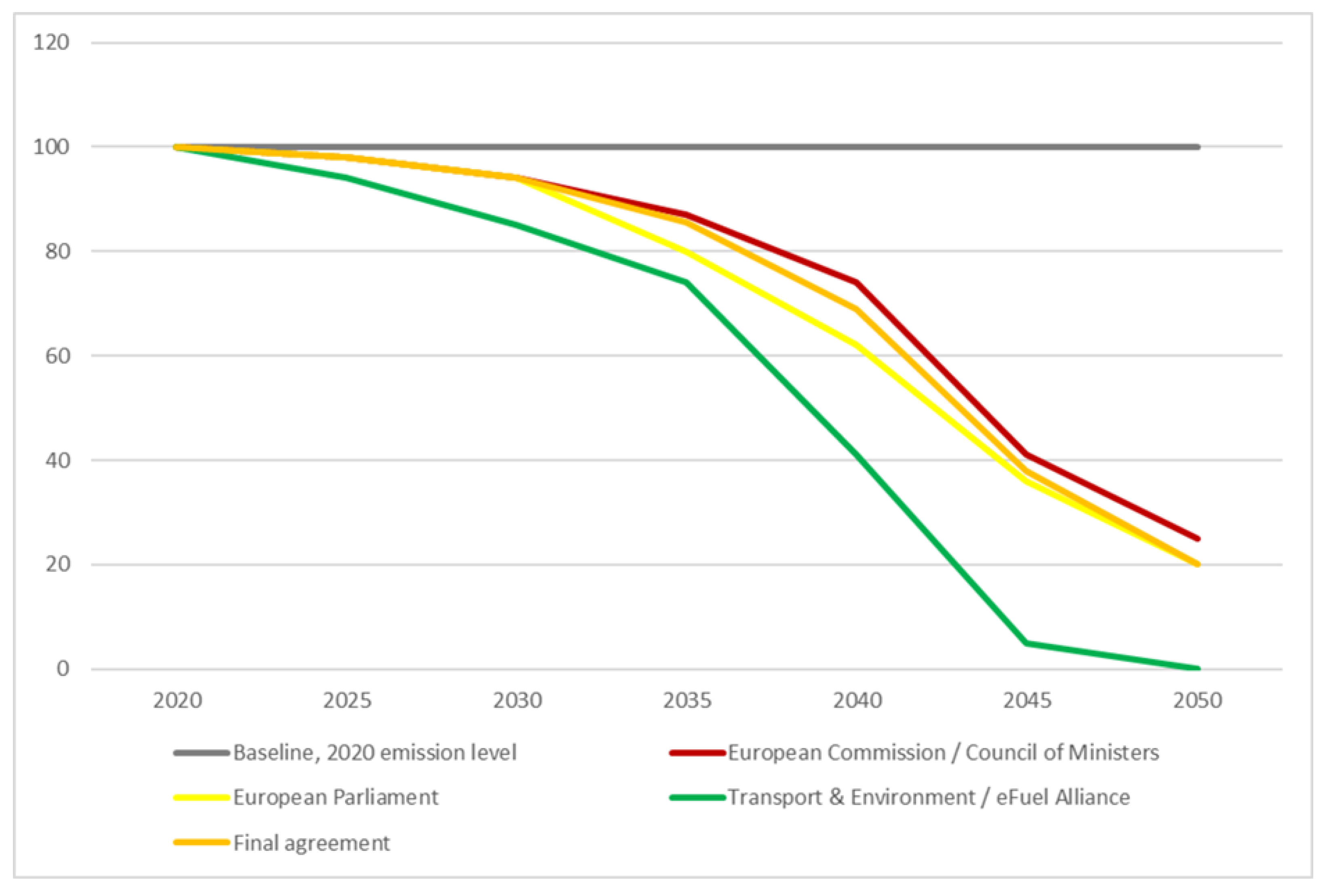

As for the ambition of the FEUM regulation, the EC proposed moderate GHG intensity targets for 2025–2050 (EC, 2021b): -2 % from 2025, -6 % from 2030, -13 % from 2035, -26 % from 2040, -59 % from 2045 and -75 % from 2050. When designing the legislation, the EC wabbled the targets to allow the fossil fuel industry to switch from oil to liquid natural gas (LNG) and the green fuels industry time to ramp up production:

“We have made a conscious choice to start with maybe a lower ambition level, to give time to the market to develop and to ensure that in time these necessary quantities of green fuels will be available to everyone who needs them,” said Roxana Lesovici, a member of the cabinet of EU transport commissioner Adina Vălean, speaking at a conference on green innovation in the maritime sector in September 2021.[7]

In dialectic response to the above problem framing, ENGOs and progressive companies in the maritime value chain stressed that climate change is an emergency, and that emission reductions must be on par with the Paris Agreement targets, thus be reduced significantly also in a short-term perspective. All fossil fuels must be banned, and use of the most effective alternative fuels, i.e. RFNBOs, must be drastically increased. Thus, T&E, together with Seas at Risk and the Getting to Zero Coalition[8] called on the EU to set a clear target for zero-emission shipping by 2050, and make sure that new policy works towards achieving the EU target of climate neutrality by 2050. Leaders of companies and NGOs in the Getting to Zero Coalition (2022) stated that:

”As the EU member states already support full decarbonization of international shipping by 2050 in the IMO, setting this target at home would also strengthen the EU’s position globally and drive progress towards global regulation. Emission reductions should be 100 % in 2050.”

As for the ambition of the FEUM regulation, T&E proposed much higher and steeper GHG intensity reduction targets for 2025–2050 (T&E, 2022b): -6 % from 2025, -15 % from 2030, -26 % from 2035, -59 % from 2040, -95 % from 2045 and -100 % from 2050.

In the Council of transport ministers, most MSs supported EC’s proposal on moderate GHG targets. However, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Luxemburg, the Netherlands and Sweden, emphasized in a joint statement[9] at the EU transport ministers’ meeting in Luxemburg on 2 June 2022, that FEUM needs more ambition and a proactive legislative framework to reduce GHG emissions from the sector, meeting the target of climate neutrality by 2050. They stressed that higher ambitions on the demand side are needed to contribute to strengthen the competitiveness of the EU maritime sector and provide planning reliability for fuel suppliers, ship owners and operators. Higher ambitions are also needed to maintain EU and MS credibility in their efforts to promote an ambitious global GHG reduction strategy within the IMO, which is crucial to maintain a level playing field.

In the EP, FEUM was handled by the Committee on transport and tourism (TRAN), in combination with the Committee on environment, public health and food safety (ENVI) and the Committee on industry, research and energy (ITRE). Mr Jörgen Warborn (Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from Sweden), representing European People’s Party (EPP), was holding the lead as TRAN’s rapporteur. In his draft report, Warborn (2022) supported the ambition level for reduced GHG intensities proposed by the EC. However, the ENVI committee, the Greens, the Lefts, Social democrats (S&D) and Renew Europe (liberals) argued for higher ambitions. After negotiations between the party groups, TRAN (2022) adopted the draft report with amendments. While keeping the EC’s proposed cuts for 2025 and 2030, TRAN introduced higher cuts to GHG intensity from 2035 onwards: i.e., -20 % from 2035, -38 % from 2040, -64 % from 2045 and -80 % from 2050. The EP adopted the final report with support from EPP, S&D and Renew Europe. The file passed without any amendments. The Greens and ENVI opted for a 100 % GHG intensity reduction by 2050 in line with the proposal of T&E, with no success. The Greens’ shadow rapporteur in TRAN, MEP Jutta Paulus, criticized the rejection of the amendments proposed by Greens and ENVI (Cuffe & Paulus, 2022):

“A majority of conservatives, liberals and social democrats in the EP wants to relieve the shipping industry of its obligations in climate and environmental protection, although the EU officially advocates stricter requirements on the international stage,” she said.

6.2. Policy Framing

A vast majority (95 %) of stakeholders confirmed in the public consultation (EC, 2021f) that it is ‘very relevant’ or ‘relevant’ to promote the uptake of LoZeC fuels and diversify the fuel mix of maritime transport to accelerate the decarbonization of international shipping. Most agreed that decarbonization of shipping requires a combination of demand-pull and technology-push types of policy instruments (cf. Harahap et al., 2023). Among the latter are further funding possibilities to stimulate innovation (cf. Bach et al., 2020), which will be provided by FEUM through the allocation of revenues from FuelEU penalties.

6.2.1. Pushing Technology through Funding

A majority of actors, including the EC, the EP, business associations, companies and ENGOs argued that revenues from the penalties should be allocated to an EU wide fund that would finance innovation projects to support the rapid deployment and the use of LoZeC fuels in the maritime sector, by stimulating (i) production of larger quantities of LoZeC fuels, (ii) construction of appropriate bunkering facilities or onshore power supply infrastructure in ports, and (iii) development, testing and deployment of the most innovative technologies in the fleet to achieve significant emission reductions. An EU wide fund, like the Innovation Fund (EC, 2021b) or a new Ocean Fund (EP, 2022), would pool EU resources to finance innovation of the most promising technologies by economies of scale, giving highest return of investment.

MSs in the Council had a different view. In response to the EC proposal, they argued that innovation projects would better be funded by MSs, who could allocate funding to decarbonization projects that are most innovative from a national perspective. Thus, they argued in unison that penalties should be collected by and allocated to the MSs. However, the main reason behind this was rather for MSs to keep some competence in the implementation of FEUM. There is a constant debate on subsidiarity and the need for collective action on the EU level. MSs often contest EU energy and climate policy based on either sovereignty (subsidiarity claims) (Wettestad et al., 2012; Herranz-Surralés, 2019; Herranz-Surralés & Solorio, 2022). MSs usually want room for manoeuvring, flexibility, related to national circumstances. Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, energy, climate and transport policy are shared competence between MSs and the EU, with energy policy being based on Article 194 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (EU, 2012). EU climate policy is based on Articles 191–193 of TFEU. EU transport policy is based on Articles 90–100 of TFEU. In response to the subsidiarity principle, the EC claimed in its FEUM proposal the need for exclusive action on EU level, with no room for member state flexibility:

“Without action at EU level, a patchwork of regional or national requirements across EU members states would risk triggering the development of technical solutions that may not necessarily be compatible with each other. /…/ As the problem drivers identified in the context of this proposal do not fundamentally differ from one EU member state to another and given the cross-border dimension of sector’s activities, these issues can be best addressed at EU level. EU action can also inspire and pave the way to develop future measures accelerating the uptake of alternative fuels at global level.” (EC, 2021b, p. 4–5).

Thus, EC proposed a regulation instead of a directive. A regulation is effective towards the legal subjects (in this case shipping companies) directly, while a directive must be transposed into national legislation, opening for MSs implementing EU provisions in different ways. Allocating revenues from penalties to MSs gives them some room for manoeuvring.

6.2.2. Pulling Demand of LoZeC Fuels

The central element of FEUM is pulling demand by requiring shipowners to use LoZeC fuels. In accordance with neo-classic economic theory (Azar & Sandén, 2011), the EC held that innovation is best stimulated by technology neutral policy. Given the array of technologies used in the sector (Christodoulou & Cullinane, 2022), EC’s policy proposal for FEUM suggested that an increased uptake of LoZeC fuels should be stimulated by a goal-based approach, setting technology neutral GHG intensity reduction targets (see section 6.1), without legislators telling which fuel(s) to use (EC, 2021b, 2021c). The EC proposal was heavily influenced by shipping associations, incumbent shipping and fossil-fuel companies (InfluenceMap, 2023), arguing that the most effective, zero-emission fuels like RFNBOs are too expensive and that investments in their production is costly and associated with high economic risks and low profits. Industry associations such as the European Community Shipowners’ Associations (ECSA), the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), the World Shipping Council (WSC) and FuelsEurope advocated that a technology neutral and goal-based approach such as GHG intensity targets would be more suitable than a blending mandate (e.g. ECSA & ICS, 2021).

T&E in collaboration with other ENGOs, business associations and progressive companies from the maritime value chain had a different view on how to stimulate innovation of LoZeC fuels, particularly RFNBOs. They argued in dialectic response, that the technology neutral approach proposed by the EC and the incumbent shipping and fossil fuel industry will see ship operators choose the cheapest fuel options to cut emissions, LNG and biofuels, fuels that ENGOs oppose. T&E and allies argued that RFNBOs are key to reduce emissions by 100 % and reach decarbonization by 2050. The share of LoZeC fuels must be at least 18 % in 2030 and 85 % in 2040 (T&E, 2022b).

Thus, T&E and allies, such as Seas at Risk, members of Getting to Zero Coalition, the Clean Air Task Force, a US based ENGO pushing for technology and policy changes needed to achieve a zero-emissions planet at an affordable cost, Environmental Defense Fund, a US based ENGO, and progressive companies and organizations across the maritime value chain, wanted EU lawmakers to spur the uptake of RFNBOs via the inclusion of technology specific measures such as multipliers and mandatory sub-quotas (T&E, 2022c, 2022d). Technology specific measures are considered the best to stimulate innovation according to evolutionary economic theory (Foray, 2018). According to, i.a., Getting to Zero Coalition, Environmental Defense Fund, Maersk, Global Maritime Forum, Siemens and Hydrogen Europe, EU policymakers should set a target of at least 5 % scalable zero-emission fuels used in shipping activities covered by EU regulation by 2030. This would “help make the ensuing rapid scale-up and uptake of RFNBOs commercially viable by 2030, thus making the 2050 energy transition end date within reach” (Getting to Zero Coalition, 2022). T&E (2022c, 2022d) and a large coalition of actors in the maritime shipping value chain (eFuel Alliance, 2022) recommended policymakers in the Council and the EP to go even further and:

set a minimum share of >6 % RFNBOs use on ship operators from 2030, >12 % from 2035, >24 % from 2040, >36 % from 2045 and >48 % from 2050, and

bridge the cost-competitiveness gap with other alternative fuels via introduction of a multiplier of 5 for RFNBOs.

According to T&E and its allies (T&E, 2022b, 2022c), high(er) sub-quotas will stimulate market development and deployment of RFNBOs. This could help unlock massive investments and job opportunities in Europe and globally, as well as contribute to making the EU the leading global supplier of zero-emission shipping and fuel production technology. This is also important from a strategic autonomy perspective, giving first movers’ advantage to the EU hydrogen economy, T&E claimed in tandem with green politicians in the EP (Cuffe & Paulus, 2022).

In the Council, most MSs supported the technology neutral approach of the EC, but Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Luxemburg, and the Netherlands, influenced by T&E and their national shipping and fuel industries, who are first movers in green shipping and green shipping fuels, opted for a multiplier and sub-quota on RFNBOs. Negotiations in the Council led EU transport ministers to agree on a compromise and call for a multiplier of 2 for RFNBOs (Council, 2022).

The EP was also divided on this issue. EP rapporteur Warborn and EPP shared the view of the EC and the majority of MSS and proposed a technology neutral approach (Warborn, 2022). However, the Greens, the Lefts and ENVI, inspired by T&E and eFuel Alliance, opted for a 6 % sub-quota and a multiplier of 5 for RFNBOs (Cuffe & Paulus, 2022). S&D and Renew Europe shared the sentiment of the technology specific approach but suggested a sub-quota of 2 % and a multiplier of 2. After negotiations, the TRAN committee agreed on a multiplier of 2 and a sub-quota of 2 % for the use of RFNBOs from 2030. This was adopted in the EP plenary with support from EPP, Renew Europe and S&D.

7. Discourses and Coalitions

As presented in section 6, the EU institutions, MSs, party groups, companies and IGs had different views on the discursive framing of problems and suitable solutions for the FEUM regulation. We can identify two strands of storylines developed in dialectic conversation with each other. Argumentation in each strand developed as the storylines were criticized by opponents. The main lines of dispute, critical for the design of FEUM, were the urgency of climate action and associated ambition levels of GHG reductions and the storylines on how to best stimulate the innovation and uptake of LoZeC fuels, particularly RFNBOs.

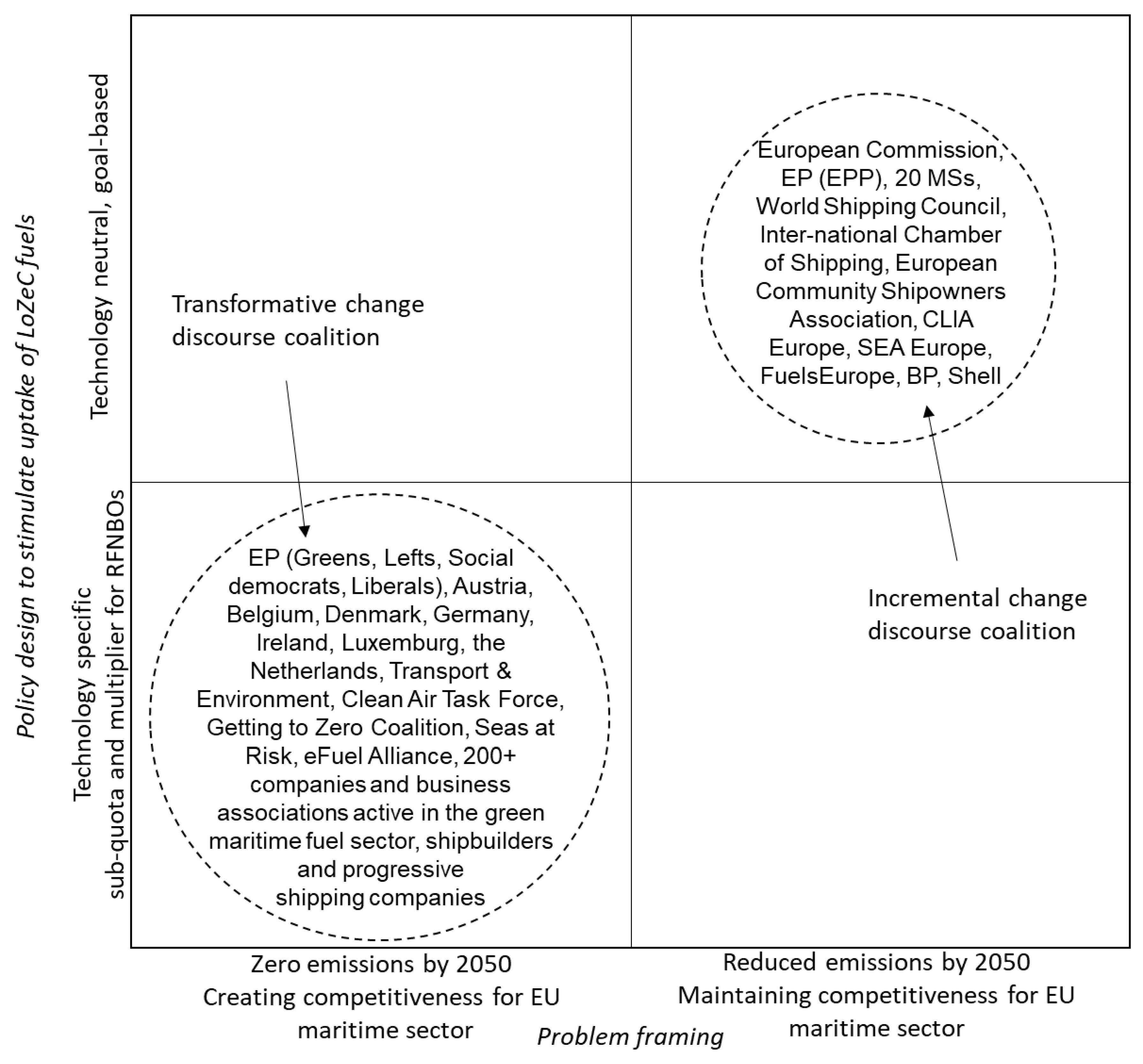

From analysing the storylines of different policy actors, two discourses and related discourse coalitions can be identified (

Figure 1), focusing on: (i) technology-neutrality for

incremental change to reach moderate emission reductions, and (ii) technology-specificity aiming at

transformative change for climate neutrality. Discourse coalitions comprise sets of storylines, the actors who adhere to and articulate such storylines, and practices that are consistent with the storylines. The incremental change coalition, which was subordinate in terms of members but dominant in terms of capital invested, comprised of the EC, most MSs, EPP, ECSA, WSC, ICS, incumbent shipping companies and the fossil-fuel industry. The transformative change coalition, dominant in terms of number of members but not invested capital, comprised ENGOs like T&E, CATF, SaR and EDF, a small group of MSs, the green-left party groups in the EP, GtZC, eFuel Alliance, and progressive companies from the maritime shipping value chain. A shared understanding of the policy problem or policy proposal does not necessarily mean that members of a discourse coalition share a similar worldview. This explains why EPP and most MSs in the Council, having agreed to the EU target on climate neutrality by 2050, were part of the same discourse coalition as the fossil-fuel industry. They did not share beliefs, but they shared a set of storylines.

The incremental change discourse was worried about economic impacts of high costs of alternatives to fossil fuels, especially RFNBOs,[10] the need for transition fuels and thus aims at more moderate emission reductions. According to its storylines, high ambitions for emission reductions risk reducing the competitiveness of the EU maritime sector. To address these problems, storylines to frame policy focused on technology neutrality and the need for a goal-based approach where legislators do not pick ‘winning’ technologies. These storylines were ‘invented’ by the EC as a policy entrepreneur, under heavy influence of lobbying by international and European shipping associations, incumbent shipping companies and the fossil fuel industry (InfluenceMap, 2023). The EC communicated its storylines in the proposal for the FEUM regulation (EC, 2021b, 2021c). In addition, it sought to gather support for its discursive framing by participating in conferences and stakeholder consultations in the European Sustainable Shipping Forum and the European Ports Forum, as well as being present at the negotiations in the Council and in the trilogue negotiations. Here, the main purpose was to influence and answer questions from MSs, MEPs and other stakeholders, and to act as an ‘entrepreneurial gatekeeper’; selecting, rejecting or reshaping the ideas that floated around in the “policy primeval soup” (Kingdon, 1984, p. 140).

The transformative change discourse framed the problem as climate change as an emergency and thus a need for ambitious GHG emission reductions, banning fossil fuels and a need for rapid scale-up of production and deployment of zero-carbon maritime fuels. The discursive framing of the policy to address these problems includes technology specific policy with sub-quotas and a multiplier for the most advanced and effective zero-carbon fuels, i.e. RFNBOs. It was argued that this could help unlock massive investments and job opportunities in Europe and globally, and that it will increase competitiveness of the EU maritime sector as a frontrunner in the clean transition, becoming a leading global supplier of zero-emission shipping and fuel production technology, as well as gaining first mover advantage to the EU hydrogen economy. These storylines were ‘invented’ by T&E as a policy entrepreneur, in collaboration with other ENGOs and progressive actors in the maritime value chain, as a response to the EC proposal on FEUM. Through careful construction of a broad coalition of allies (T&E, 2022c), T&E found effective ways to leverage the knowledge and skills of others towards a common goal. Such policy network is a repository of knowledge, know-how, war stories, and professional gossip, and can be vital sources of information for policy entrepreneurs (Petridou & Mintrom, 2021). Advocating a different framing than the EC, T&E and allies particularly wanted to influence the Council and the EP once the EC had presented its proposal. To communicate the storylines and gather support for these alternative discursive framings, T&E and allies wrote reports, position papers, op-eds and participated in expert group meetings, conferences and targeted stakeholder consultations such as the European Sustainable Shipping Forum and the European Ports Forum. T&E and allies had no influence on the EC proposal, but was rather successful in its communication towards some MSs and the EP, Thus, the storylines of T&E were told also by progressive MSs and green-leftish party groups in the EP in negotiations in the Council and the EP.

Both discourses were legitimate, but neither of them was hegemonic, meaning socially or culturally predominant in the policy debates on FEUM. Discursive hegemony is achieved through discourse structuration and discourse institutionalization (Hajer, 1995; Bulkeley, 2020). Discourse institutionalization may be achieved by drawing on resources such as knowledge, legitimacy, power, and demonstration of material benefits. In the case of FUEM, both discourses were coherent and credible, thus structured. In addition, both the EC and T&E had knowledge, statistics and technical-economic analysis as a backbone for presenting their problem framings and policy options. The concepts, elements and storylines articulated by both discourse coalitions were acted on in the policy process, but none of them replaced each other’s understandings of the issue, why they were not fully institutionalized. As discussed by von Malmborg (2024a), the EC and T&E as policy entrepreneurs coupled their own strands of problems, policies and politics in their respective part of the policy domain, but they were not able to couple all streams entirely. In a sense, the two competing discourses were semi-hegemonic.

8. Discursive Agency to Reach Consensus

Discursive frames are not only cognitive and normative structures that influence and constrain social actors. They are political resources that can be harnessed in a strategic way (Lynggaard, 2019). Discursive framing is an inherently political process. As Baumgartner and Jones (1993, p. 6) put it, “every interest, every group, every policy entrepreneur has a primary interest in establishing a monopoly – a monopoly on political understandings concerning the policy of interest, and an institutional arrangement that reinforces that understanding”. Here, monopoly can be understood as discursive hegemony. As a result, different discursive frames often compete.

Not all discursive frames work. They must make sense, be acceptable and appeal to a sufficiently large constituency to rally wide support (Benford & Snow, 2000). The most effective frames are usually those that appeal to a hegemonic discourse with well-established interest, cognitive scripts, norms and identities (Bocquillon, 2018). Moreover, for a discourse to durably shape politics, it needs to become embedded in an institutional framework consisting of stable organizational, procedural and normative structures (Baumgartner & Jones, 1993; Lenschow & Zito, 1998; Nilsson, 2005). Only through a process of discourse institutionalization can the reconfiguration of the policy space, and incidentally the coherence between certain discourses and discursive frames, become generally accepted and durable (Bocquillon, 2018; Bressand & Ekins, 2021).

There were two competing discourses and discourse coalitions in the EU on decarbonization of maritime shipping, one including among others the EC, a majority of MSs and incumbents, the other including among others T&E, other ENGOs, progressive companies, and several party groups in the EP. With no truly hegemonic discourse, discursive agency on FEUM can be characterized as interdiscursive communication ‘navigating between different and conflicting discourses’. The aim of such navigation is to mutate the competing discourses into one. In the case of FEUM, this means one discourse that could frame a consensual agreement on the FEUM policy between the Council and the EP as co-legislators. Lynggaard and Triantafillou (2023) outline three specific strategies of agency for such navigation: (i) exclusion, (ii) multiple functionality, and (iii) vagueness. These are related to the different discursive interaction strategies proposed by Dewulf and Bouwen (2012).

Table 4 outlines the interlinkages between the discursive interaction strategies and the strategies for discursive agency analysed in this paper.

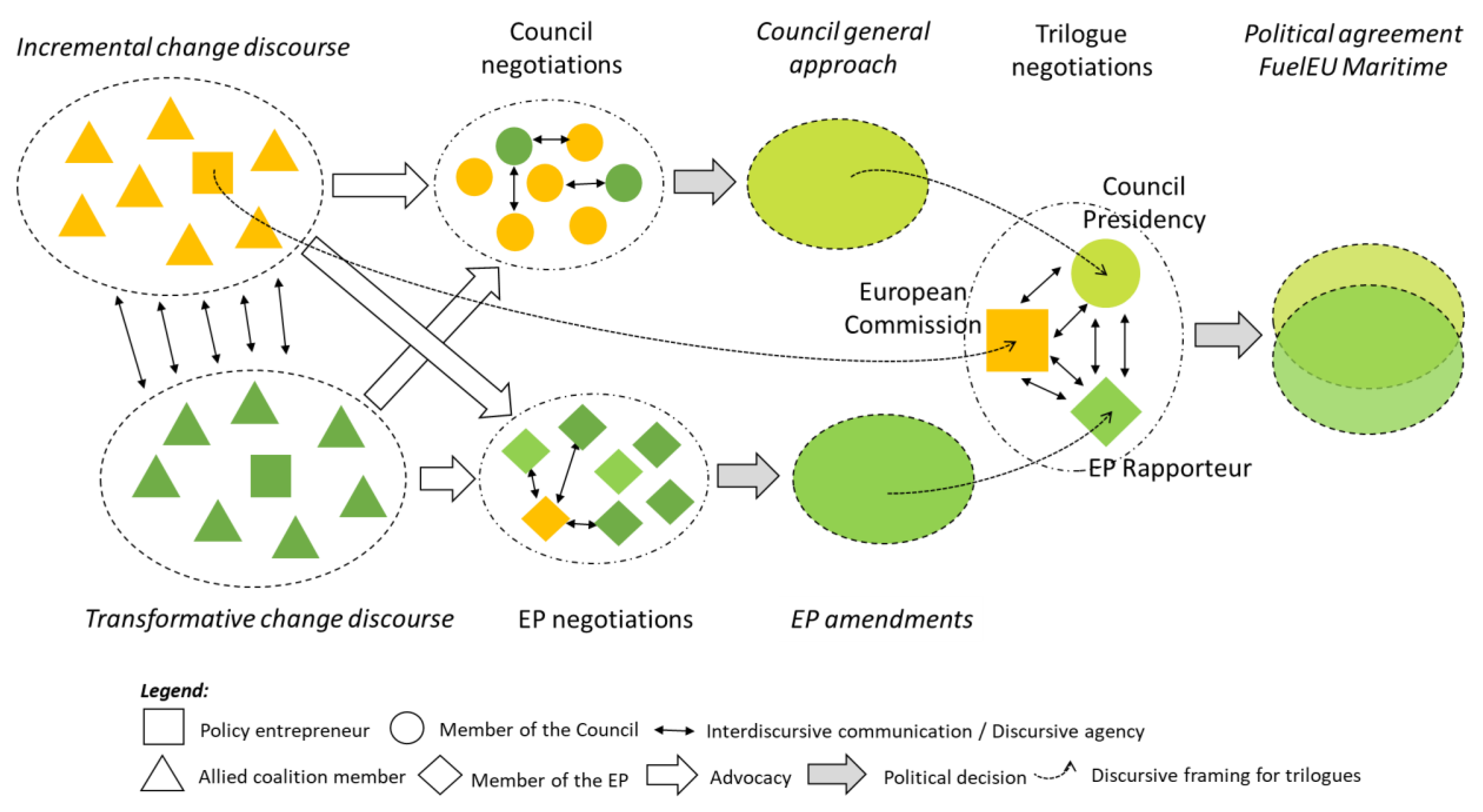

The transformative change discourse evolved as a critical response to the incremental change discourse. The two discourses continued to evolve in dialectic conversation with each other. Once mature, actors of the two discourse coalitions tried to influence members of the Council and the EP as co-legislators to make them legitimate. These institutions moulded the discourses and the discursive frames in intra-institutional negotiations which were then used to frame their respective negotiation mandates on FEUM (Council, 2022; EP, 2022). The discourses were further moulded in inter-institutional negotiations between the co-legislators, who eventually found a compromise (

Figure 2).

8.1. Exclusion Increased Polarization

The initial attempts to navigate between competing discourses were made by EC and T&E and their allies while trying to influence different stakeholders, particularly MSs in the Council and party groups in the EP when they were preparing negotiations on their mandates for the upcoming trilogues. The two discourses and related policy proposals were polarized. In dialectic conversations with the EC proposal, T&E and its allied interacted with the EC’s storylines and discursive frames by ‘exclusion’ as a discursive agency strategy, criticizing, polarizing and disconnecting the challenging elements from the ongoing conversation as irrelevant and unimportant, e.g. moderate emission reductions and technology neutrality implying that fossil LNG could still be used. T&E together with Seas at Risk, an association of ENGOs dedicated to marine protection, argued that the Fit for 55 package related to shipping does not add up to the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global heating to 1.5 degrees, nor the EU target on climate neutrality by 2050 (T&E, 2022a). Dr. Lucy Gilliam, senior shipping policy officer at Seas at Risk argued that:

“The most insidious aspect of the proposals is that they will create a system that incentivises a shift from one fossil-fuel to another. In its current form, FuelEU Maritime will actually incentivise the use of fossil gas in form of LNG for shipping well into the 2040s” (Seas at Risk, 2022).

Responding to the critique of including LNG in FEUM, slowing the adoption of zero-emission fuels while locking in reliance on fossil gas, the EC argued that a sudden switch to RFNBOs is unrealistic due to supply issues. Joaquim Nunes de Almeida, director for energy-intensive industries and mobility with the EC’s DG for Growth, said:

“We have to be aware of the constraints in which industry is operating right now, and right now the truth of the matter is that you still have very little renewables and hydrogen or decarbonised forms of energy available in Europe” (Euractive, 2021).

The EC and allies did the same with the T&E storylines. For instance, industry players, such as CLIA Europe, a cruise lines trade association, and SEA Europe, a group representing shipbuilders and maritime equipment manufacturers, obstructed attempts to make the purchase of RFNBOs compulsory, as the current low supply makes these fuels hugely expensive (Euractive, 2021). A sub-quota on RFNBOs will increase costs for the shipping sector to meet the GHG target by 20–30 %, they argued. In addition, WSC expressed concern that the RFNBO sub-quota proposed by T&E could lead to unnecessary complexity rather than long-term investment in low-carbon paths, distracting from the goal to reduce GHG intensity so that achieving interim quotas becomes the focus.

The discursive agency of exclusion did not help to solve the differences between the discourses, rather it increased the polarization. The Council and the EP adhered to different discourses and discourse coalitions respectively.

8.2. Trilogues as a Venue for Reaching Consensus

The principal policy venues in policymaking on EU legislation are the negotiations in the Council, the EP and so-called trilogues, i.e. tripartite negotiations between the Council, the EP and the EC (Pollack, 2014). Informal trilogues have become an institutionalized standard operating procedure in the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in December 2009 (Brandsma, 2015; Roederer-Rynning, 2019). Under co-decision, negotiation in trilogues can facilitate cooperation between the two co-legislators, by creating ‘mutual confidence, and positive trust spirals’ and by augmenting ‘skills at political compromise’ (March & Olsen, 1998, p. 960). In trilogue meetings, the institutions are represented by negotiating delegations tasked with facilitating and finding a legislative compromise through consensus between institutions. The main actors in the political navigation to reach consensus on FEUM, which took place in the trilogue negotiations between the Council, the EP and the EC in spring 2023, were the Council, or rather the rotating Council Presidency, represented by the transport attaché and the EU ambassador of the Swedish Presidency and their team, and the EP, represented by rapporteur Warborn, his team of political assistants and fellow MEPs from different party groups and committees. The Council and the EP represented each of the discourses and discourse coalitions – although somewhat changed (see section 8.3). In addition, the EC, represented by a director, a head of unit and policy officers from DG MOVE, took part to answer questions but also to be an ‘entrepreneurial gatekeeper’. All institutions were also represented by their legal services.

Consensus between the EU co-legislators can be reached in different ways. The mode of negotiation to be found in general EU decision-making processes, including trilogues, is contextually determined (Elgström & Jönsson, 2011). Processes of learning have resulted in changes in the EU’s negotiation style: problem-solving has become increasingly institutionalized within the EU machinery (Elgström & Jönsson, 2011). Day-to-day negotiations are largely deliberative exercizes trying to reach agreement through the force of the better argument. Convincing others of the right thing to do, rather than bargaining via threats and promises, is the morally superior way of interaction in the EU (Heisenberg, 2008; Naurin & Wallace, 2008; Elgström & Jönsson, 2011; Roederer-Rynning & Greenwood, 2021). Under certain circumstances, however, conflictual bargaining occurs. The pattern varies with levels of politicization and polarization and type of policy, and according to the stage in the decision-making process (Elgström & Jönsson, 2011).

In the case of FEUM, the issues of emission reduction trajectories and technology neutral goal-based vs. technology specific policies and policy design options such as level of sub-quota and multiplier were highly politicized (von Malmborg, 2023a, 2024b). The high salience and level of politicization relates to FEUM, together with the inclusion of shipping in EU ETS, being the first EU policy in a field that require rather high emission reductions. Expectations were high for ambitious emission reduction targets and policies that could gain EU leadership in the clean energy transition, but incumbents required low impacts on competitiveness of EU shipping in a truly globalized sector. In addition, FEUM had the potential to be the world’s most ambitious legislation for decarbonizing maritime shipping, with the EU having ambitions to be a global leader in climate governance (von Malmborg, 2024a). In all, this made negotiations in the trilogues to be of a bargaining rather than deliberative mode (cf. von Malmborg, 2023a) stalling policy learning across coalitions (von Malmborg, 2024b).

8.3. Multiple Functionality Incorporated Elements of Competing Discourses