1. INTRODUCTION

Consciousness of the role of feeding on the health is constantly increasing, and hence people are searching for foods and beverages with allegations of health properties [

1]. Thus, functional beverages such as kombucha fit the perspectives of different consumers as functional foods and can be considered as healthy drinks [

2].

Various studies have shown that the consumption of kombucha is associated with antioxidant [

3,

4,

5], antimicrobial [

6,

7] and antiproliferative [

4,

8] properties, a reduction in triglyceride levels, treatment of digestive diseases, and stimulation of the immunological system [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The beverage also contains metabolites such as organic acids, vitamins, minerals, and phenolic compounds [

13,

14].

Kombucha, which originated in the region of Manchuria (China), is basically a mixture of sugar with tea fermented by a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeasts (SCOBY) [

15]. Black or green teas are the most used teas and sucrose the most used sugar, but currently other substrates with bioactive properties are being studied and used, such that the beverage presents functional properties [

16,

17]. To be considered as a functional food, it must conform with the following requisites be a food product, have scientific evidence sustaining the benefit of the product, show measurable physiological effects and be consumed daily as part of the normal diet [

18].

Of the microorganisms capable of carrying out these conversions Acetobacter Xylinum is the bacterium most mentioned, plus the yeast genera

Brettanomyces,

Zygosaccharomyces,

Saccharomyces and

Pichia [

19,

20]. According to Leal et al., (2018) [

21], kombuchas are a source of bioactive components such as polyphenols and glucuronic acid. Basically, the lactic acid bacteria transform the glucose into gluconic acid and the fructose into acetic acid, while the yeast hydrolyse the sucrose producing fructose and glucose, a true symbiosis between the yeast and bacteria, producing a cellulose pellicle known as SCOBY, which remains suspended in the tea containing the metabolites [

22].

The presence and amounts of metabolites depend on the types of microorganism in the symbiotic culture used to ferment the kombucha, also considering the time, temperature, amount of sucrose and type of tea used in the fermentation [

23,

24]. The fermentation time is an important factor, influencing the antioxidant and sensory properties of the fermented product, which suffers a sudden fall in pH value and consequent increase in acidity, a characteristic typical of this beverage [

25,

26].

Sensorially, kombucha can be described as a refreshing, slightly sweet, carbonated, acidic, functional tea, which helps promote health by way of a symbiotic culture containing acetic acid bacteria and yeasts [

21]. Yuliana et al., (2023) [

27], used cocoa honey as the fermentation substrate for the tea in the presence of SCOBY, and observed that the acidity and total soluble solids decreased after six days of fermentation, confirming the good sensory quality of the kombucha beverage.

The beverage kombucha can present a natural flavour or a typical flavour caused by using diverse fruits such as apples [

28], cocoa [

27], coffee [

26] or diverse flowers, amongst other ingredients such as the milk used in the initial culture [

29].

In addition to being an extremely popular beverage, coffee contains bioactive compounds, as do

Camellia sinensis teas, to which health benefits are attributed, the principal components being caffeine and phenolic compounds – catechins in tea and chlorogenic acids in coffee [

30,

31,

32].

Amongst coffee classifications, we can find traditional and special coffees. Special coffee indicates coffee with a score above 80 points on a scale between 0 and 100 points, awarded according to a sensory evaluation by a Q Grader (a professional taster specialized in special coffees) using the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) methodology [

33].

The objective of this study was to elaborate a kombucha with the addition of special coffee from the 1st fermentation and evaluate the physicochemical, colorimetric, and sensory characteristics of the beverage. A simple study design was used, where the coffee infusion was the only variable, and the percentage of Camellia sinensis green tea was fixed. After 18 days of fermentation (5 days of aerobic fermentation and 13 days of anaerobic fermentation) the beverages were analysed and compared.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

The green tea used was from the Leão brand (Brazil).

The special coffee used was 100% arabica Red Catuai (IAC H 2077), originating in Natércia (MG, Brazil) and distributed by Coffee Run Bike, considering the sensory evaluation described on the label.

The fermentation process takes place in 3-liter glass jars. The glass jars used were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 minutes. During the fermentation process, the glass jars were covered with paper towel and secured with elastic tape. Production was kept in the dark, at an average temperature of 28.8ºC.

2.2. Elaborating Process

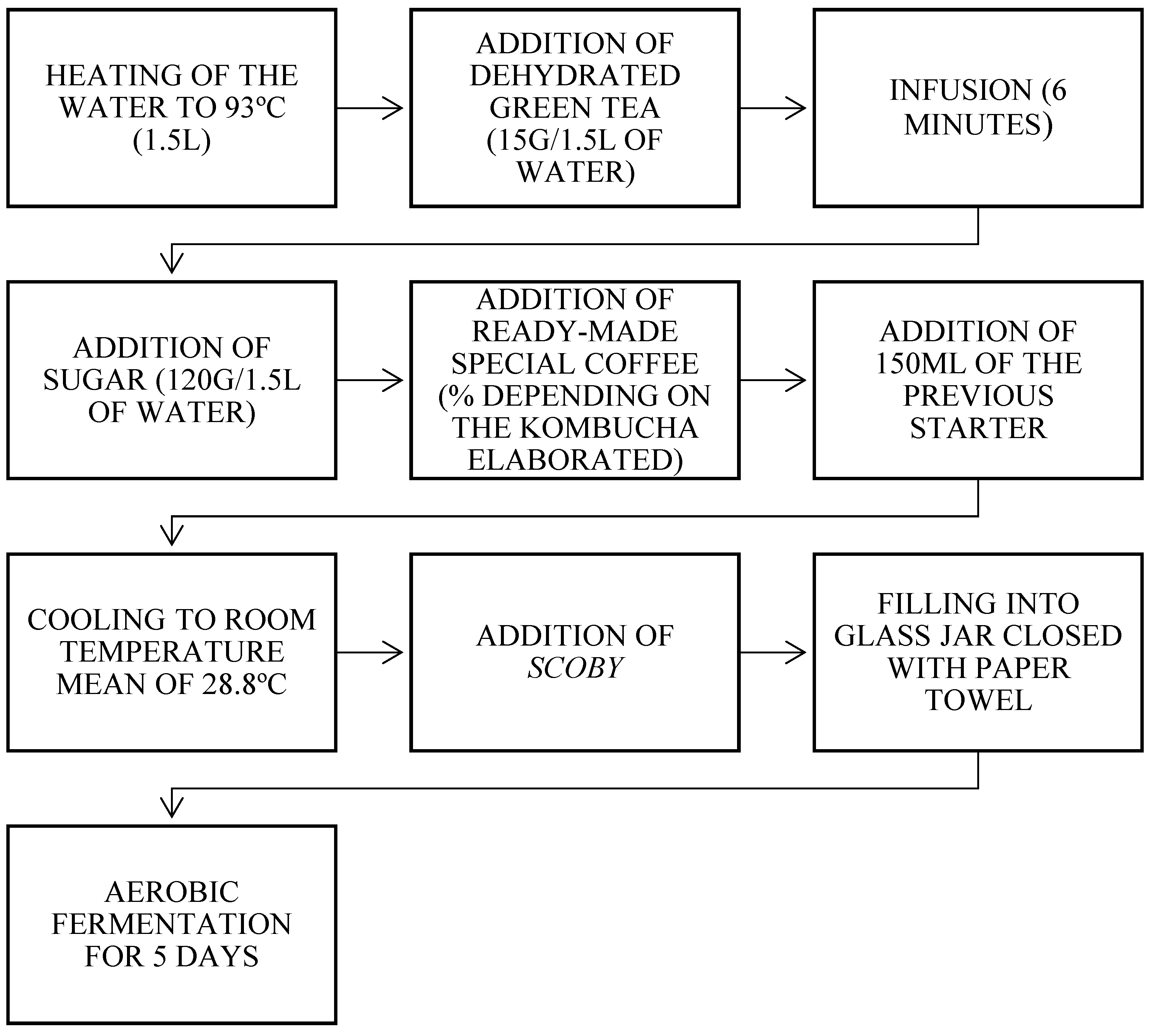

The flowsheet in

Figure 1 shows the process used for the coffee flavoured kombucha beverage up to the 1

st fermentation, with the description of each part of the flowsheet described in steps.

2.2.1. 1st Step: Preparation of the Coffee Infusion

The coffee infusion was produced by the V60 equipment (Hario - Japan). A quantity of 10 g of coffee powder was placed in contact with 100 mL of water (hot brew process – extraction at 93ºC by the V60 filtration). This filtration method allows for an efficient extraction of the compounds conferring a mild sweetish flavour on the beverage, thus producing the coffee infusion used to elaborate the kombucha beverages. Due to the single large hole and the grooves at an angle of 60º from the base to the top of the filter, the air manages to escape without impeding the expansion of the coffee grounds caused by the vapour.

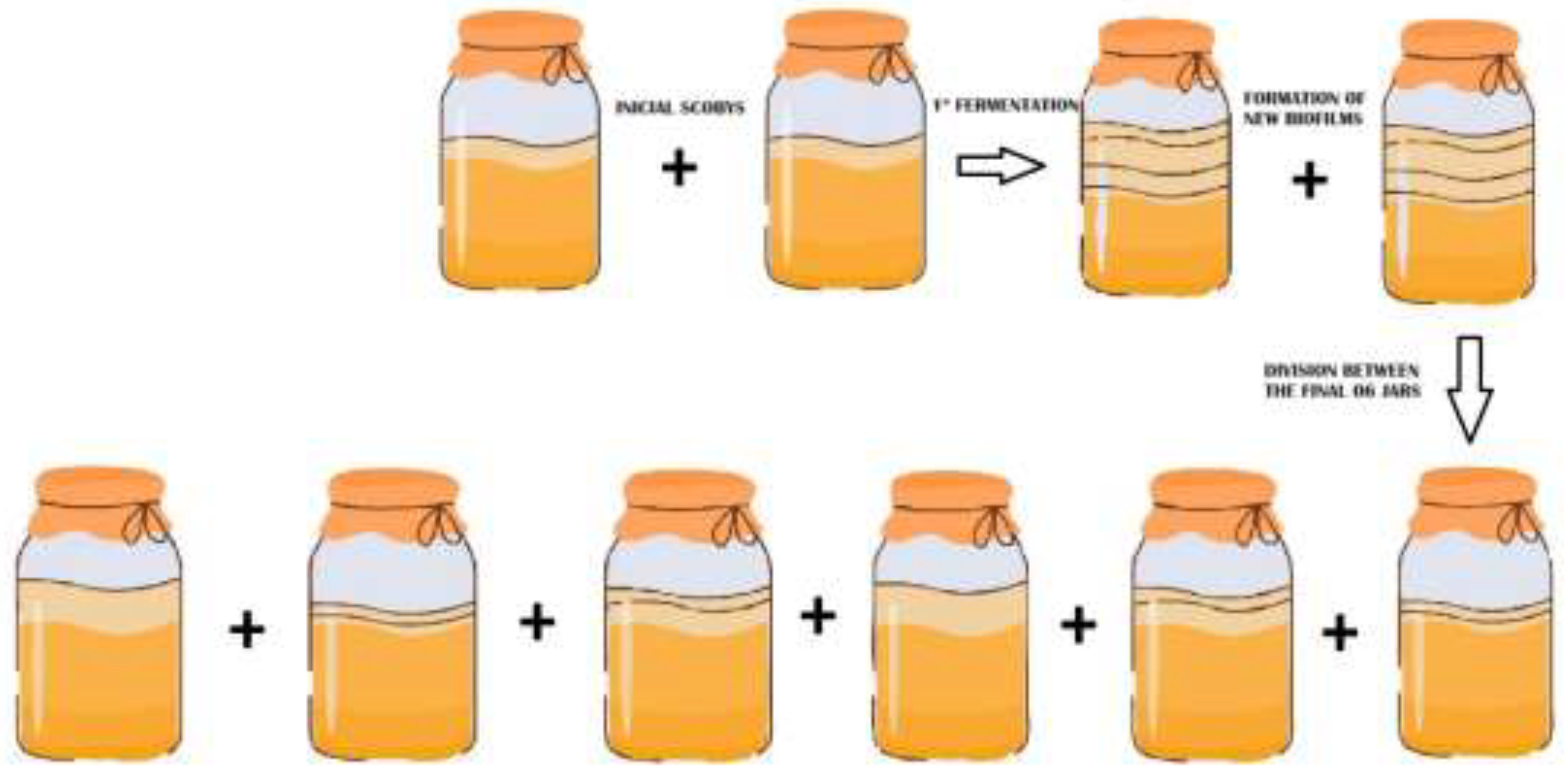

2.2.2. 2nd Step: Obtaining the SCOBY Cultures and Preparing the Material

Two scobys, weighing between 200g and 300g, were donated by a kombucha micro company located in the city of Salvador (Bahia, Brazil). Each scoby was added to a 3-litre glass jar containing 200 mL of tea, 200 g of sugar, 150 mL of starter (tea from the previous kombucha) and 1.5 mL boiled mineral water. The formation of four new scobys (biofilms) was observed in each jar, which were divided between 4 more glass jars, giving a total of 6 jars, each containing scobys of equivalent weight, with the same individual conditions described previously (design 01). The whole process was carried out under controlled conditions of temperature and moisture content, maintained at about 28ºC and 69%, respectively.

2.2.3. 3rd Step: Experimental Design

Various preliminary tests were carried out with different fermentation times and amounts of ingredients until a kombucha beverage with an acceptable flavour was obtained. The sensory evaluation was carried out with kombucha beverage consumers with a daily consumption frequency, using a 3-point scale (disliked; neither liked/nor disliked; liked). A kombucha denominated as the control was obtained and used to elaborate the subsequent formulations with different concentrations of coffee infusion (

Table 1).

2.2.4. Preparation of Kombucha Beverage Formulations with Different Coffee Proportions

The biofilm samples (scobys) did not have identical weights since the materials were of a natural origin, but they all contained, on average, between 200g and 300g.

After the first derivation (when the original

scoby created another biofilm), tests were carried out with the previously mentioned proportions of 13% of green tea and 2% of coffee, 11% of tea and 4% of coffee, 4% of tea and 11% of coffee, and 2% of tea and 13% of coffee (

Figure 2).

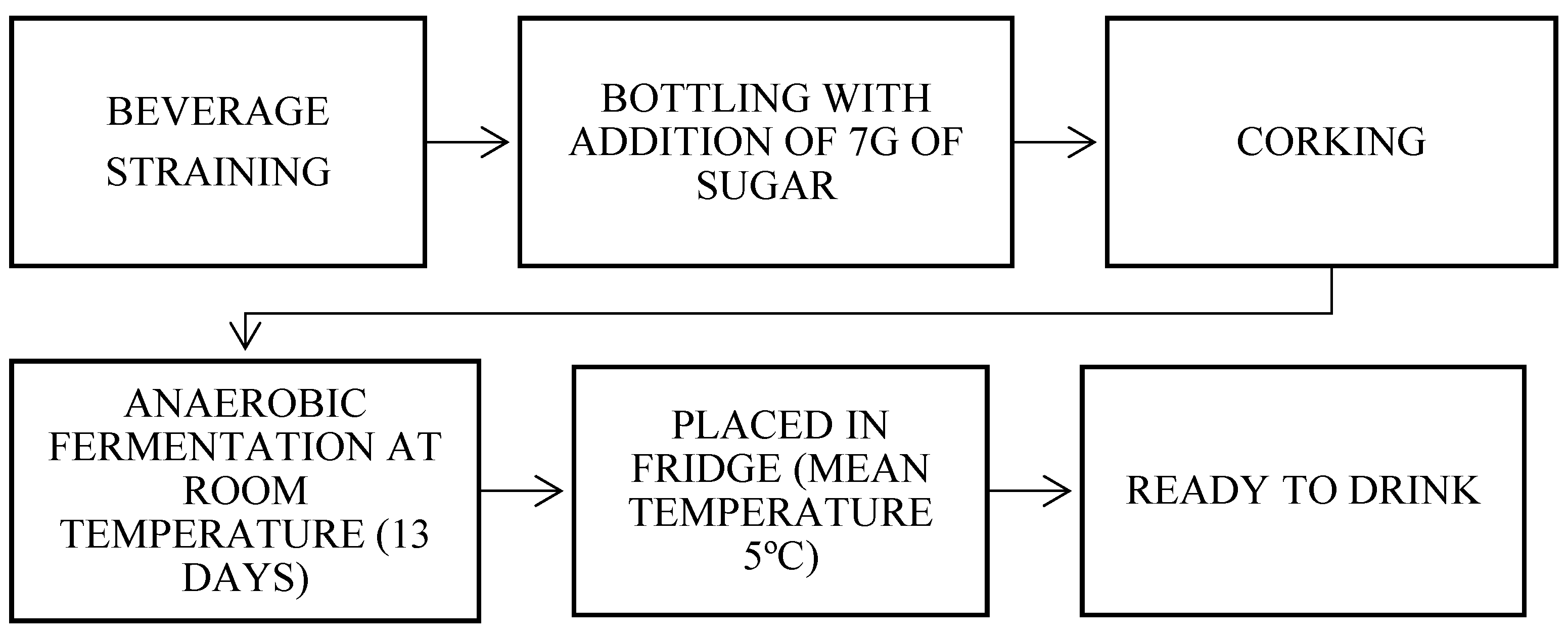

After 5 days of aerobic fermentation, the beverages were bottled, 7g of sugar added, the bottles sealed and left for 13 days at room temperature. Anaerobic fermentation occurred during this step of the process, with the formation of gas (

Figure 4). The liquid was then transferred to 370 mL glass bottles, refrigerated for 2 days at 7ºC, and then analysed (

Figure 3).

2.2. Sensory Analysis

Before the sensory analysis, the formulations were analysed for their microbiological innocuity, for the safety of the evaluators.

A preliminary sensory analysis was carried out during the fermentations to adjust the fermentation time according to the flavour agreeability, on a scale of disliked, neither liked/nor disliked and liked.

One hundred and twenty acid beverage consumers from the academic community and invited external kombucha appreciators, took part in the sensory acceptance test of the four formulations denominated as K1, K2, K3 and K4. The participants evaluated the acceptance of colour, aroma and flavour using a 10cm scale with extremes of “disliked extremely’ and ‘liked extremely’, intermediated by the term ‘neither liked/nor disliked’ [

34]. The samples, refrigerated at 7ºC, were coded with three digits, balanced using a complete block design and presented in a monadic way with drinking water at room temperature to rinse the palate.

The test was applied in the Sensory Analysis Laboratory of the Faculty of Pharmacy (UFBA) according to the ABNT NBR ISO 13299 norms. The project was appreciated and approved by the Ethics in Research Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy/UFBA under report number CAAE: 57013122.4.0000.8035.

2.3. Physicochemical Analyses

Some parameters, such as the pH value, alcoholic degree, and volatile acidity, were analysed according to the methodologies described in NI (Normative Instruction) nº 41/2019 [

35].

The pH was determined using a KASVI (K38-1465) pH-meter.

To determine the alcoholic degree, 100 mL of the sample were placed in the distillation flask of an Electronic Hydrostatic Balance, mod. Superalcomat (Gilbertini) together with 20 mL of water. A volume of 80 mL was collected and the alcoholic ºG read using the Oenochemical Electronic Distilling Unit Super D.E.E. (Gilbertini). The volatile acidity was also determined using the Oenochemical Electronic Distilling Unit Super D.E.E. (Gilbertini) with 20 mL of sample. The reducing and total sugar contents, and the ash, moisture, lipid, and protein contents were determined according to the AOAC methodologies [

36] indicated for beverages. Total sodium was analysed by atomic emission spectrophotometry (AES) (Varian Spectra AA 55B, Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia).

A total of 275 mL of each kombucha formulation was used to determine these parameters.

2.4. Colorimetric Analysis

The colorimetric parameters were determined using a Konica Minolta colorimeter (Chroma Meter CR-5) in the transmittance mode with a standard D65 luminant and 10º observational field, according to the standardization of the

Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIELabe CIEL*C*h) system and the OIV norms (2022) [

38]. A 10 mm thick 5 mL glass cuvette was used to measure the colour of the samples in triplicate, determining the values for luminosity (L* = 0 or L* = 100), red/green colour component (a+* and a-*), blue/yellow colour component (b+* and b-*), Chroma (C*) and hue (h). The colour tests were carried out in triplicate as shown in

Table 3.

2.5. Microbiological Analyses

The four samples were tested for the presence of Salmonella and Escherichia Coli, obtaining negative results for these bacteria, thus confirming the safety of the kombuchas according to the parameters of Guide 23 of 2019 [

38].

2.6. Statistical Analyses

The data were analysed statistically using the XLSTAT program to calculate the Univariate Variance Analysis (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test, considering (p = 0.05).

3. RESULTS

Table 2 shows the physicochemical analysis of the kombucha formulations. Amongst the 4 formulations, the total sugar content showed no significant differences. The sugar content is an important parameter since it could be associated with the sensory acceptance of the product, apart from being an important data for the nutritional formation of the beverage. The sugar content, among the formulations, ranged from 5.8 to 7.0g/100g, if compared with the sugar values present in soft drinks, the formulations (K1 to K4) have 32 to 40% less sugar. Soft drinks have a sugar content between 8.5 and 11.8 g/100g [

39].

The ash and protein contents resulted in no significant differences between the four formulations. With respect to the pH value, all the formulations presented values that characterized the formulations as kombuchas, but in relation to volatile acidity, only k4 meets the legislation standard. The attributes of total sugars, ash and protein contents resulted in no significant differences between the four samples. However, there was a significant difference of more than 5% with respect to the pH value, volatile acidity, alcoholic degree and the sodium, moisture, and lipid contents.

Considering the caloric value, the formulations have values between 35 and 39 kcal, in caloric terms these formulations are close to soft drinks, which have 39 to 42 kcal. The formulations (K1, K2, K3 ou K4) can be substitutes for soft drinks, with the advantage of having low sugar concentrations.

In relation to sodium, the concentration varied from 0.61 to 0.75 mg/100 mL, in the formulations. This value is considered low when compared to soft drinks, which have an average of 8 to 11 mg/100 mL.

The

Table 3 shows the values obtained for the colour parameters and, it is possible to observe excellent discrimination of formulations by colour parameters. Notably, the higher the coffee concentration, the higher the values for C* (colour purity), a* and b*, suggesting K4 as a beverage tending towards reddish-brown and slightly more turbid (L=86.9) as compared to the others. The a* values vary according to the increase in coffee concentration, which went from -0.8 to 1.9 with 18 days of fermentation. Miranda et al., (2023) [

26] found values of a*=0.62 using 2% coffee infusion in the preparation of kombuchas.

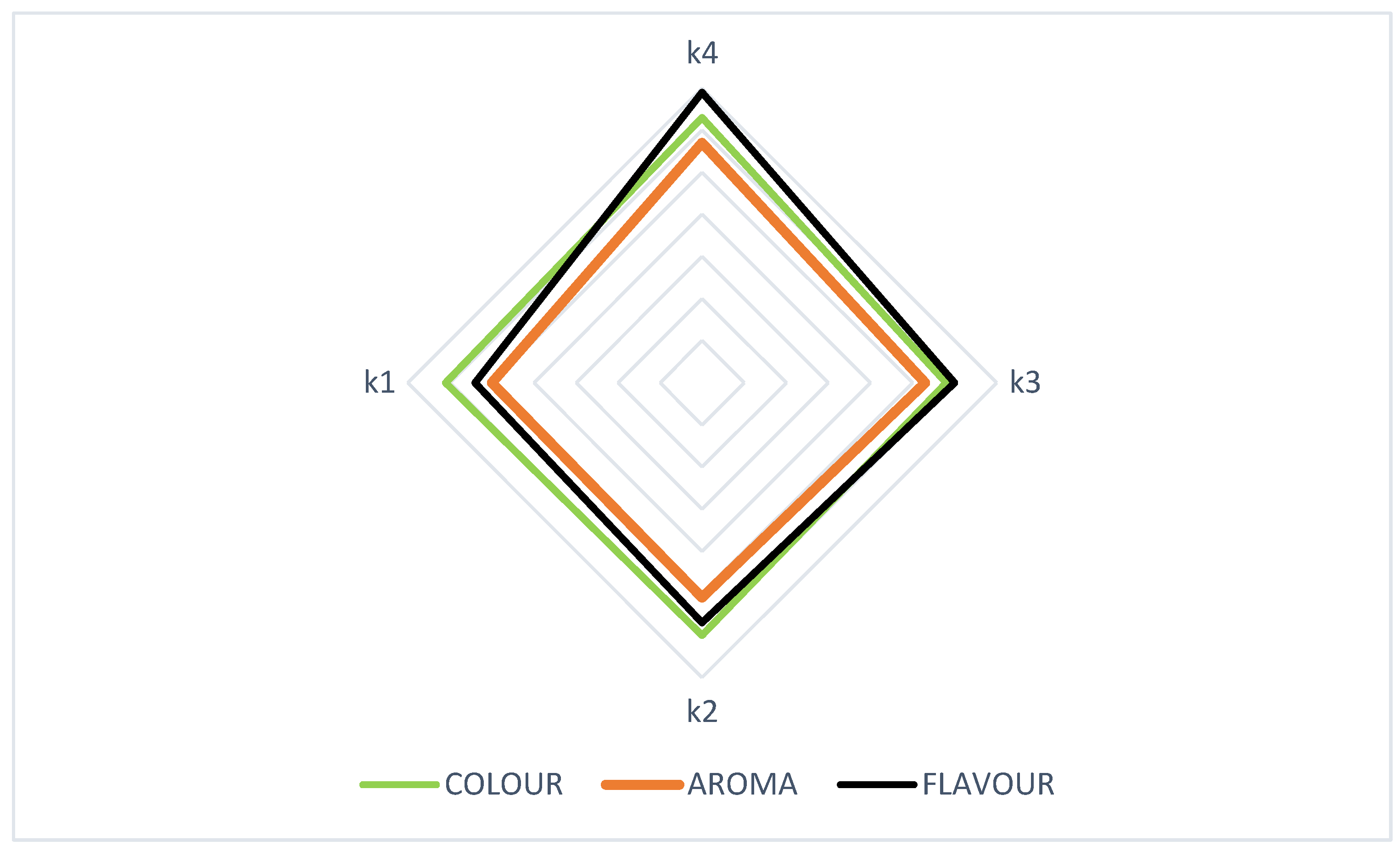

With respect to the sensory analysis, the evaluators carried out the acceptance test for the attributes of colour, aroma, and flavour (

Figure 4). Before carrying out the sensory analysis, the four formulations (K1, K2, K3, and K4) were tested for Salmonella and Escherichia Coli, obtaining negative results for the pathogenic bacteria, that is, conforming to the parameters of Normative Instruction (NI) nº 41/2019 [

35], confirming the safety of the kombuchas as adequate for consumption.

The variance analysis (ANOVA) (p<0.05) of the evaluation data for the kombucha samples showed no significant difference between the formulations for the colour and aroma data. However, there was a significant difference between the samples for flavour, K3 and K4 receiving the highest score (

Table 4). It is important to consider that the acceptability of the flavour of these formulations was greater than score six, that is, further from the zone of doubt or rejection, on the 10cm scale.

The representation of acceptance, in the form of a figure (

Figure 5), shows greater flavour distension at the extreme of the K4 formulation, compared to K3, K2 and K1.

5. DISCUSSION

According to Brazilian legislation, to be considered as kombucha, a beverage should present volatile acidity, alcoholic degree, and pH value in determined specific ranges to guarantee its identity standard. Of the proposed formulations, only kombucha K4 was not classified as an alcoholic kombucha. There was probably a slowdown in fermentation, as coincidentally K4 has the highest concentration of sugar, indicating that it was not consumed in fermentation.

With respect to the pH value, all the formulations presented values that characterized the formulations as kombuchas. The pH value is one of the most important environmental parameters that affect the fermentation of kombucha, since some of the acids formed, such as acetic and gluconic acids, could be responsible for the biological activities of the resulting beverages [

40].

The formulation K4 showed the highest indices for total sugars, pH value and the ash and lipid contents, together with K3, and presented the highest sodium index.

With respect to the volatile acidity, only K1 and K2 qualified as kombucha, and with respect to the alcohol content only K4 can be considered non-alcoholic, with a value of <0.5 %v/v. Regarding the pH value, all the formulations were within the established parameters of from 2.5 to 4.2 [

35]. The coffee concentration probably influenced the development of fermentation by the yeasts or bacteria, since a slightly higher pH value was observed on increasing the coffee concentration when compared with the beverage prepared with the smallest coffee concentration. The same behaviour was observed for the volatile acidity, that is, the acidity decreased on increasing the coffee concentration.

Sodium levels, an important and mandatory parameter of technical regulation RDC nº 429/2020 [

41], ranged from 0.61 to 0.75 mg/100g. RDC nº 429/2020 [

41] describes standards for declaring nutritional information for food products that require information on the amount of sodium on the product label. When comparing the sodium content of the formulations (K1 to K4) with the levels of this element in soft drinks, it can be seen that kombuchas have around 91% less sodium than soft drinks. High sodium intake is linked to high blood pressure, which compromises health and increases the risk of cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and myocardial infarction.

Comparing the caloric value of kombucha formulations with soft drinks, the difference is very small, but kombucha has bioactive compounds that bring benefits to the health of the gastrointestinal system. The possibility of replacing soft drink consumption with kombucha is very beneficial for your health, as the amount of common sugar and preservatives ingested will be lower.

The color of the kombucha drink is an important parameter, as it is slightly cloudy and slightly yellowish. Adding coffee to the preparation of kombucha causes significant changes in color parameters [

26]. Thus, the values of the a* parameter indicate a redder drink when increasing the coffee concentration. The variation of *a (-0.8 to 1.9) is due to the increase in the concentration of coffee used in preparation, these values are proportional to those found by [

26], but the color depends on the type of coffee and its preparation .For the parameter of colour, kombucha K4 was the most appreciated with a mean score of 6.35, followed by K1 with 6.10, K2 with 6.03 and finally K3 with 5.84. Formulation K4 presented the following values for the colour parameters – a* (1.9), b* (34.5), C* (36.5), and L (86.9), hence the highest acceptance for the colour of the kombuchas was associated with the highest concentrations of coffee.

In relation to flavour, the most appreciated kombucha was again K4, with a mean of 6.96, followed by K3 with 6.07. We might suggest that the colour of the kombuchas might have influenced the acceptance of the flavour of the darker beverages. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Osterbauer et al. (2005) [

42] showed the influence of colour on flavour and odour. The authors showed the perception of colour-odour congruency. Therefore, these colour-flavour interactions are probably “real”.

Thus, kombucha K4, with the highest coffee percentage was the most accepted amongst the evaluators for all the parameters. This was also the sweetest of the beverages with the lowest acidity and the only one considered non-alcoholic, which might have influenced the perception of the evaluators. According to Rossini and Bogsan (2023) [

43], before NI nº 41/2019 [

35], there was no control of kombucha production in Brazil, and in 2021, almost 100% of the kombuchas were classified as alcoholic, a result not favourable to the proposal of kombuchas.

On the other hand, K1 was the least accepted of the kombuchas for the parameters of aroma and flavour, this being the kombucha closest to the original kombucha beverage, resulting in a more acid beverage with a lower sugar content and highest alcoholic degree (

Table 2). This formulation showed the highest volatile acidity, smallest colour purity value (C*) and highest luminosity (L).

The analysis of the acceptance representation, in the form of a figure (

Figure 5), shows a slight distension towards the extreme of the K4 formulation, which be due to the flavour, as it was the only attribute that differed between the formulations.

We suggest that the use of coffee in the production of kombucha presented a positive impact on the acceptance of these beverages. We also suggest refining the process and carrying out new analyses such as those for antioxidant activity and the antimicrobial effect, since this study focussed on the development and obtaining of a coffee-flavoured kombucha beverage. It is also important to control the process to obtain a non-alcoholic kombucha, to increase the impact on its consumption.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Laboratory of Bromatology and the Laboratory for Studies in Food Microbiology (LEMA) of the Federal University of Bahia. Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Programa de Desenvolvimento da Pos-Graduacao (PDPG -Grant Number: 88881.708195/2022-01)

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declared there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the research described, publication of the results or financial questions.

References

- Liu, X.; Song, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, X.; Liu, J.; Granato, D.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J. Effects of different dietary polyphenols on conformational changes and functional properties of protein–polyphenol covalent complexes. Food Chem. 2021, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwetcharoen, H.; Phung, L.T.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, S.; Tippayawat, P.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. Kombucha Healthy Drink—Recent Advances in Production, Chemical Composition and Health Benefits. Fermentation 2023, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Yan, F.; Cao, Z.; Xie; F.; Lin, J. Antioxidant activities of kombucha prepared from three different substrates and changes in content of probiotics during storage. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Dai, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, J. Kombucha fermentation enhances the health-promoting properties of soymilk beverage. J. Func. Food. 2019, 62, 103549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiripun, V.; Apisittiwong, T. Polyphenol and antioxidant activities of Kombucha fermented from different teas and fruit juices. J. Curr. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkod, T.; Bovonsombut, S.; Tragoolpua, Y. Efficacy of kombucha obtained from green, oolong, and black teas on inhibition of pathogenic bacteria, antioxidation, and toxicity on colorectal cancer cell line. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleil, M. M.; Ellatif, S.A.; Soliman, M. H, Abd Elrazik, E. S.; Fadel, M.S. A bioprocess development study of polyphenol profile, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Kombucha enriched with Psidium guajava L. J. Microbiol. Biotech. Food Sci. 2020, 9, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.R.; Azevedo, R.O; Martino, H.S.D.; Cameron, L.C.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Barros, F.A.R. Kombuchas from green and black teas have different phenolic profile, which impacts their antioxidant capacities, antibacterial and antiproliferative activities. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloulou,A.; Hamden, K.; Elloumi, D.; Ali, M.B.; Hargafi4, K.; Bassem Jaouadi, B.; Ayadi, F.; Elfeki, A.; Ammar, E. Hypoglycemic and antilipidemic properties of kombucha tea in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012. 12, 63.

- Jung, Y.; Kim, I.; Mannaa, M.; Kim, J.; Wang, S.; Park, I.; Kim, J.; Seo, Y.S. Effect of kombucha on gut-microbiota in mouse having nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoko, S.B.B; Harisman, E.K.; Y.E. Puspitasari. The kombucha from Rhizophora mucronata Lam. herbal tea: Characteristics and the potential as an antidiabetic beverage. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2020, 8(5), 410-42.

- Cardoso, R.R.; Moreira, L.D.P.D.; Costa, M.A. C.; Toledo, R.C.L.; Grancieri, M.; Nascimento, T.P.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Matta, S.L.P.; Eller, M.R.; Martino, H.S.D.; Barros, F.A.R. Kombuchas from green and black teas reduce oxidative stress, liver steatosis and inflammation, and improve glucose metabolism in Wistar rats fed a high-fat high-fructose diet. Food Funct. 2021, 12(21), 10813–10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.A.; Uekane, T.M.; Miranda, J.F; Motta, R.J.C.B.; Silva, C.B.; Pitangui, N.S.; Gonzalez, A.G.M.; Fernandes, F.F.; Lima, A.R. Kombucha beverage from non-conventional edible plant infusion and green tea: Characterization, toxicity, antioxidant activities and antimicrobial Properties. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 34, 102032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Júnior, J.C.; Magnani, M.; Costa, W.K.A.; Madruga, M.S.; Olegário, L.S.; Borges, G.S.C.; Dantas, A.M.; Lima, M.S.; Lima, L.C.; Brito, I.L.; Cordeiro, A.M.T.M. Traditional and flavored kombuchas with pitanga and umbu-cajá pulps: Chemical properties, antioxidants, and bioactive compounds. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, T.; Li, H.; Mastroyannis, A.; He, S.; Rahaman, A.; Chang, K. Effect of fermentation time on physiochemical properties of kombucha produced from different teas and fruits: comparative study. J. Food Qual. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariff, R.M; Chai, X.Y.; Chang,L.S.; Fazry, S.; Othman, B.A.; Babji, A.S.; Lim, S.J. Recent trends in Kombucha: Conventional and alternative fermentation in development of novel beverage. Food Biosci. 2023. 53. [CrossRef]

- Emiljanowicz, K.E.; Malinowska-Pànczyk, E. Kombucha from alternative raw materials – The review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3185–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, J.A.; Bibiloni, M. D. M. Functional Foods. Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Elsevier Reference Collection, 2016; pp. 57-161. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.C.; Chen, C. Effects of origins and fermentation time on the antioxidant activities of kombucha. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbasa, R.V.; Loncar, E.S.; Vitas, J.S.; Canadanovic-Brunet, J.M. Influence of starter cultures on the antioxidant activity of kombucha beverage. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.M.; Suárez, L.V.; Jayabalan, R.; Oros, J.H.; Escalante-Aburto, A. A review on health benefits of kombucha nutritional compounds and metabolites. CYTA—J. Food 2018, 16, 390–399. [CrossRef]

- Jayabalan, R.; Malbaša, R.V.; Loncar, E.S.; Vitas, J.S.; Sathishkumar, M. A review on kombucha tea–microbiology, composition, fermentation, beneficial effects, toxicity, and tea fungus. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. 2014, 13, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer-Petrovska, B.; Petrushevska-Tozi, L. Mineral and water soluble vitamin content in the kombucha drink. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 35, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitas, J.S.; Malbasa, R.V.; Grahovac, J.A.; Loncar, E.S. The antioxidant activity of kombucha fermented milk products with stingingnettle and winter savory. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2013, 19, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Z.; Asir, Y. Assessment of instrumental and sensory quality characteristics of the bread products enriched with Kombucha tea. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.F; Belo, G.M.P.; Limal, S.; Silva, K.A.; Uekane, T.M.; Gonzales, A.G.M.; Branco, V.N.C.; Pitangui, N.S.; Fernandes, F.F.; Lima, A.R. Arabic coffee infusion based kombucha: Characterization and biological activity during fermentation, and in vivo toxicity. Food Chem. 2023, 412, 135556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulianaa, N.; Nurainya, F.; Sari, G.W.; Widiastuti, S.E.L. Total microbe, physicochemical property, and antioxidative activity during fermentation of cocoa honey into kombucha functional drink. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubaidah, E.; Yurista, S.; Rahmadani, N.R. Characteristic of physical, chemical, and microbiological kombucha from various varieties of apples. IOP Conf. Series: Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 131, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkaya, P.; Akan,E.; Kinik, O. Use of kombucha culture in the production of fermented dairy beverages. LWT- Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 137, 110326.

- Dias, RC.E.; Benassi, M.T. Discrimination between Arabica and Robusta Coffees Using Hydrosoluble Compounds: Is the Efficiency of the Parameters Dependent on the Roast Degree? Beverages, 2015, 1, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.S.A.; Teixeira, B.S.; Sauthierb, M.C.S.; Santana, M.V.A.; Santos, W.N.L. Santana, D.A. Multivariate analysis of the composition of bioactive in tea of the species Camellia sinensis. Food Chem. 2019, 273, 39–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, C.A.; Zanzarin, D.M.; Marco, P.H.; Porto, C.; Prado, R.M.; Carvalhaes, F.; Pilau, E.J. Metabolomic kinetics investigation of Camellia sinensis kombucha using mass spectrometry and bioinformatics approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L. L.; Cardoso, W. S.; Guarçoni, R. C.; Fonseca, A. F. A.; Moreira, T.R.; Caten, C. S. The consistency in the sensory analysis of coffees using Q-graders. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, N. D. M.; Petenate, A. J.; Silva, M. A. A. P. Performance of the hybrid hedonic scale as compared to the traditional hedonic, self-adjusting and ranking scales. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16(8), 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento/Gabinete da Ministra. Instrução Normativa n_ 41, de 17 de setembro de 2019. Estabelece o Padrão de Identidade e Qualidade da Kombucha em todo o território Nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 18 de setembro de 2019. Seção 1. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/instrucao-normativan-41-de-17-de-setembro-de-2019-216803534 (accessed on 01 march 2024).

- AOAC - Association of Official Analytical Chemistry. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Analytical Chemistry.12 ed. Washington, DC, 1992. 1115p.

- OIV – International Organisation of vine and wine - Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis, 2022. Paris, 1514 p, Edition 2022.

- BRASIL. Agência Nacional De Vigilância Sanitária. Guia para comprovação da segurança de alimentos e ingredientes. GUIA nº 23, versão 1, de 23 de julho de 2019. Gerência De Produtos Especiais Gerência Geral De Alimentos. Brasília. Anvisa. Disponível em: <http://antigo.anvisa.gov.br/documents/10181/5355698/Guia+Seguran%C3%A7a+de+Alimentos.pdf/dae93caa-7418-4b9a-97f2-2ec9ebc139e2> Accesso: Dec. 11, 2023.

- Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos – TACO. 4ª edição revisada e ampliada. 2011. 161 pág. Campinas, Brazil.

- Villarreal-Soto, S. A; Beaufort, S.; Bouajila, J.; Souchard, J-P.; Taillandier, P. Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 580-588. [CrossRef]

- Osterbauer, R. A.; Matthews, P. M.; Jenkinson, M.; Beckmann, C. F.; Hansen, P. C.; Calvert, G. A. Color of scents: Chromatic stimuli modulate odor responses in the human brain. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2005, 93, 3434–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, D.; Bogsan, C. Is It Possible to Brew Non-Alcoholic Kombucha? Brazilian Scenario after Restrictive Legislation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Agência Nacional De Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução da diretoria colegiada - RDC nº 429, de 8 de outubro de 2020. Brasília. https://antigo.anvisa.gov.br/documents/10181/3882585/RDC_429_2020_.pdf/9dc15f3a-db4c-4d3f-90d8-ef4b80537380> Accesso: Dec. 01, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).