1. Introduction

The European Union has made significant strides toward achieving almost all the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

1]. Eurostat data indicates that SDG 11, "Sustainable Cities and Communities," emphasizes the necessity for elevated living standards among citizens [

2]. As urbanization continues to rise globally, it becomes imperative to comprehend the connections between urbanized environments and the well-being and health of individuals [

3]. With these in mind, there is a recognized and actively promoted role for citizens in various aspects of the European Green Deal. The Conference on the Future of Europe has brought attention to the importance of participatory processes, particularly in the context of the European Green Deal [

4]. The current research is driven by a commitment to enhancing outdoor environment quality in urban areas and improving the well-being of residents.

During last 100 years urban planning development has approached three different paradigm shifts driven by the following: technical conditions for roads and cars; road safety and visibility conditions for pedestrians and cyclists; and environmental conditions and its effects on dark skies, plants, animals and people [

5]. Outdoor lighting is revealed as a powerful tool to support Sustainable Development Goals [

6], which must be considered and balanced to make sustainable decisions. It is a complex issue that involves multiple aspects, e.g., energy consumption, lighting pollution, aesthetics and safety [

7]. To date, some researchers have provided insights into the body of knowledge involving city lighting, from different perspectives: energy performance, smart cities, user satisfaction, etc [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Research is still limited in fields such as environmental science, psychology, biology, medicine and astronomy, specifically the effects of LED lighting on animals, plants and mainly people [

13]. There is a noticeable lack of research on sustainable cities at night and the impact of light pollution from outdoor lighting on humans, flora and fauna in the context of the UN’s SDGs [

14,

15]. Until now the issue of cities for the future has not been treated in a comprehensive manner and this is due mainly to the lack of understanding of complex issues that are interrelated, therefore more studies are required to help further understanding [

5,

16].

Despite the links already demonstrated between the built environment and health and well-being [

17,

18], specifically psychophysical well-being [

19,

20,

21,

22], there are fundamental aspects that have been paid less attention. Lighting adds different meanings to people's experience of space: cognitive-affective, associative and motivational [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] directly influencing affect, emotion, mood, attention, imagination, perception, memory, judgment, closeness, openness and communication [

28,

29]. So, when designing a lighting system, it is essential to consider physical, physiological, and psychological requirements. It is important to develop architectural lighting planning that acts as a filter between people and their environment [

30].

Lighting is fundamental to people's social lives and the best way to create the link between lighting design and urban spaces is through the concept of "legibility", originally developed by urban planner Kevin Lynch in the 1950s [

31]. Making the urban night space a legible space gives the user the ability to "read" their environment, their routes and shapes depending on their perception and understanding of places and how they are connected to each other. It is important to develop architectural lighting planning that acts as a filter between people and their environment [

30]. Lighting designers need to understand how different users in fact read the social space, their map or image of that space.” [

32]

The façades of buildings delimit the social space and in the urban environment, they are a decisive factor in the perception of the citizen [

33,

34], determining the order and the way in which different objects in the visual environment are observed, this can help to understand the linkages between urbanized environments and wellbeing and health [

35,

36]. The challenge is understanding why there are places that encourage certain moods. In 1998, neuroscientists Fred H. Gage and Peter Ericksson announced the discovery that the human brain can produce new neurons favoured by richly stimulating environments [

37], this was the birth of neuroarchitecture [

38]. Recent research focuses on the application of the scientific method in the design of architectural spaces, known as Evidence-Based Design (EBD), which links scientific evidence and design parameters with user outcomes. New technological advances and interdisciplinary approaches enable the scientific community to employ neurophysiological and traditional techniques to measure user experiences, offering tools for the study of cognitive and emotional response [

39,

40,

41].

One of these tools is Kansei engineering (also referred to as affective engineering), which is a consumer-oriented method of product design. It is defined as “translating technology of a consumer's feeling and image for a product into design elements” [

42,

43,

44,

45]. The applications of Kansei engineering are numerous, especially in product development [

48,

49,

50], recent studies address the effect of indoor lighting design [

46,

47] but in the field of urban lighting the studies are still limited [

51,

52]. Traditionally, research aiming at user responses to lighting environment comes from the field of psychology or engineering, not considering parameters of lighting design that could effectively cater to specific user needs.

This study focuses on urban lighting design, exploring its effect on citizens´ emotions. A methodology based on Kansei engineering is developed in response to the question: How does lighting of facades within the urban space influence people's emotions?

2. Methodology

The methodology proposed is based on Kansei engineering and is performed using surveys. Surveys are a common research method used worldwide and considered suitable for gathering self-reported quantitative and qualitative data from a large number of respondents [

53,

54]. The use of an online mechanism offers significant advantages over more traditional survey techniques [

55], as from just a few clicks, it is possible to get an answer from anyone, anywhere in the world, at any time. The authors used an online tool to implement the survey questionnaire.

Kansei Engineering translates people's feelings into concrete design elements since it works with symbolic attributes and people's perceptions expressed in their own language. It enables linking the object of study with the user, seeing the object from a perspective that goes beyond its function and use, seeking the perfect balance between function-use of the object and acceptance-enjoyment of the design on the part of the user. This technique provides a method based on the selection of symbolic attributes (words or aesthetic descriptors) and user perceptions (emotions) generated from user language.

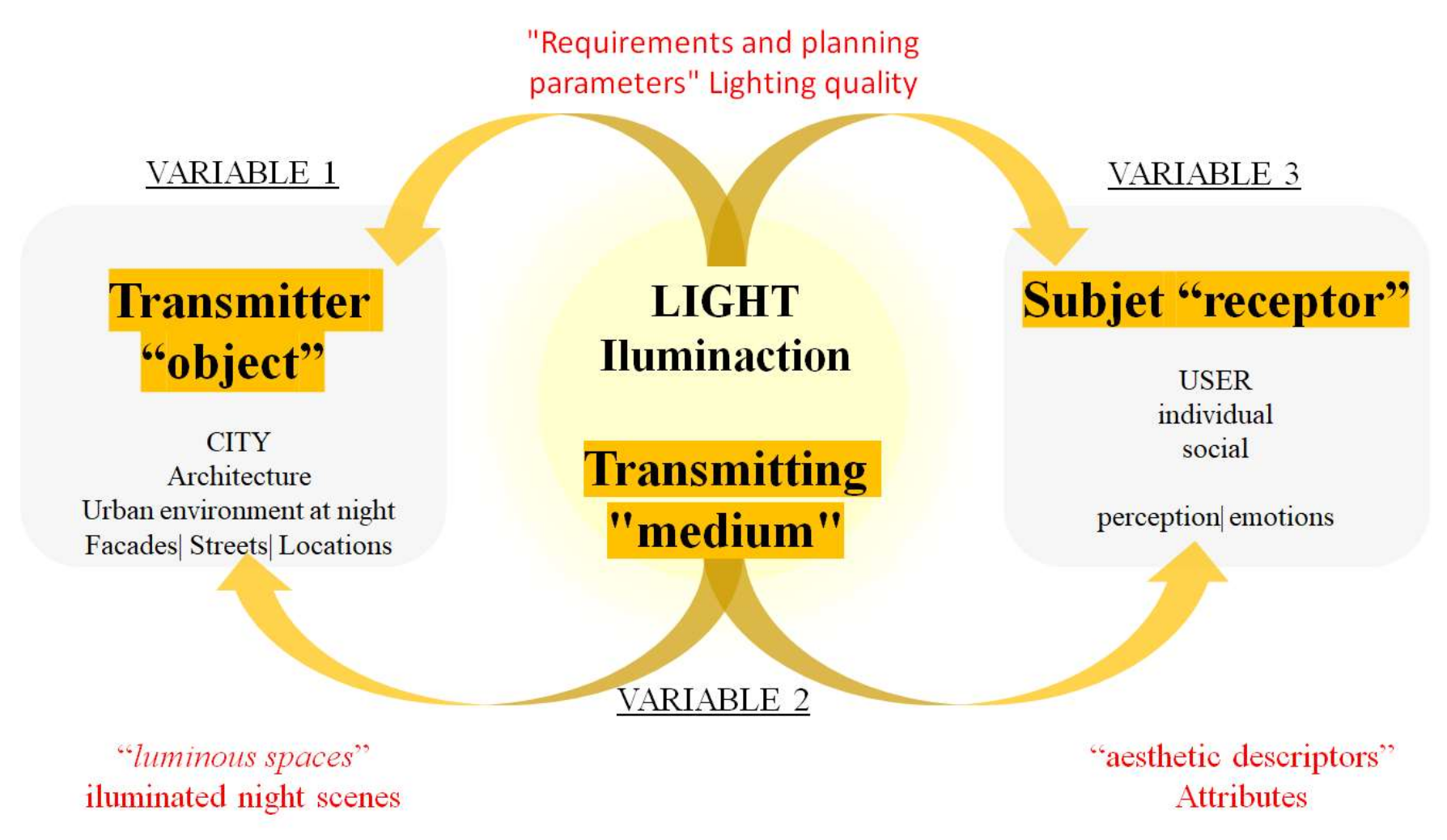

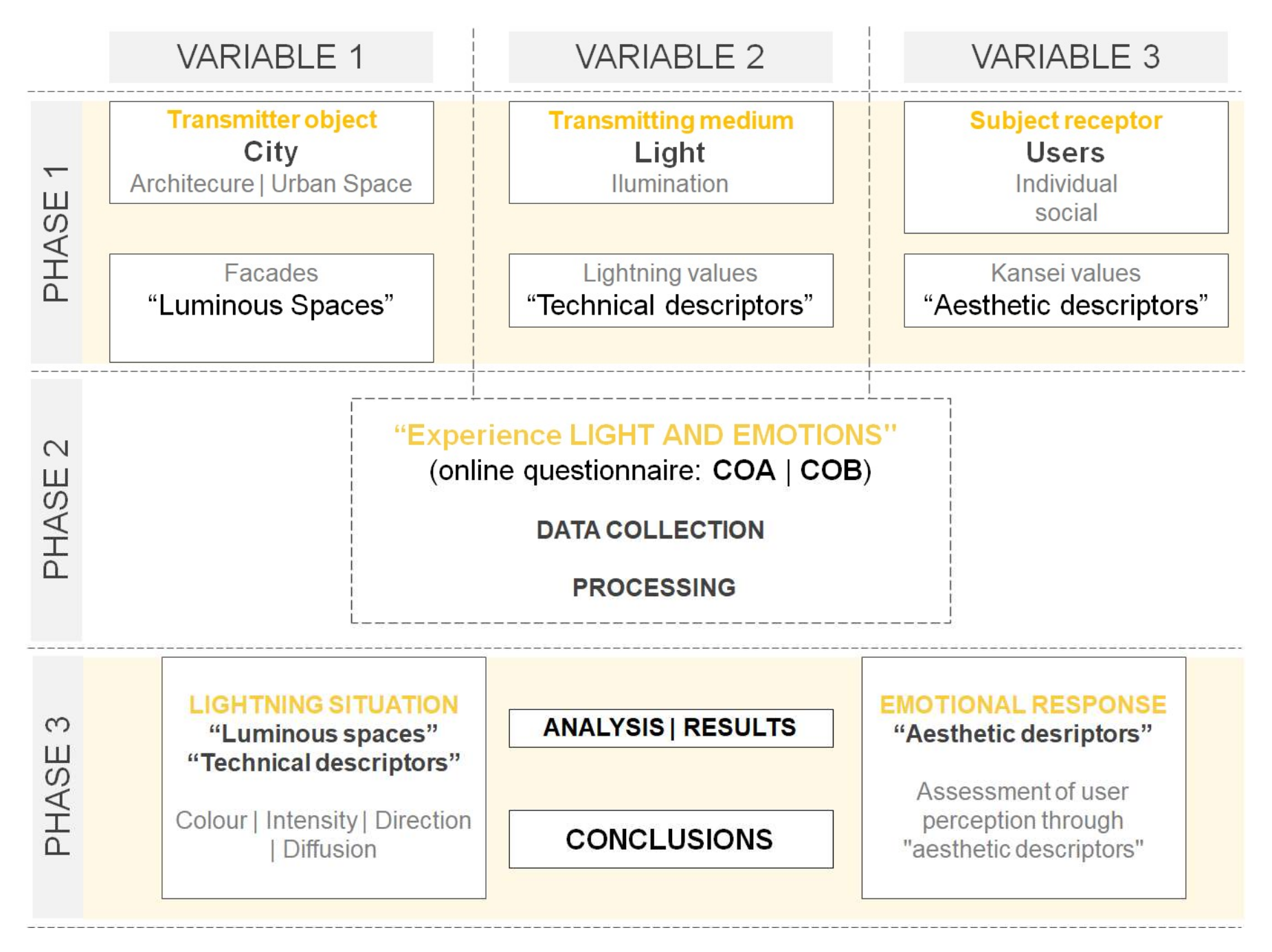

Figure 1 shows the main methodology elements. The product to be studied is “the facades of buildings within an urban space” called from now on “luminous space”, the citizen “user” through the questionnaires containing “aesthetic descriptors” to express the “emotions”.

The answers to these questionnaires are intended to evaluate the reaction of users to variations in façade lighting within the urban space and thus provide design solutions that improve people's perception and well-being, with the aim to create emotionally efficient bright urban spaces (

Figure 2).

3. Variables

The variables involved in the development of the methodology used are 3:

3.1. “ Luminous Spaces”

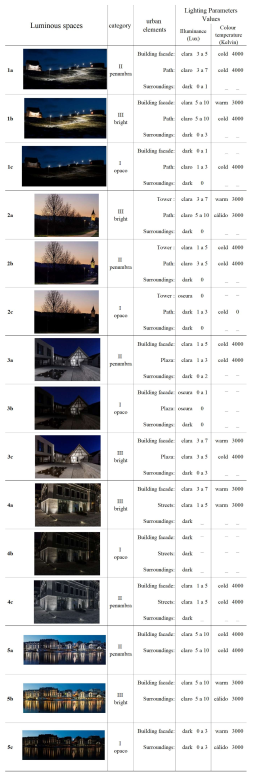

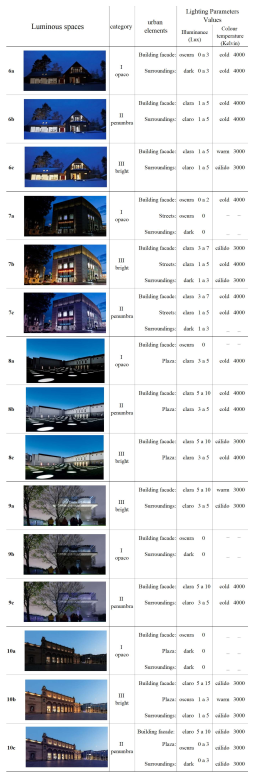

Variable 1 are images (stimulus) of “luminous spaces”. The lighting satisfies, on one hand, the functional need of the users (free circulation), and on the other hand, it fulfills a purely aesthetic factor of beautification of the city. The selection process of the “luminous spaces” was developed from professional lighting design projects, carried out by different architectural studios together with the most recognized lighting manufacturers on the market, such as Erco, Zumtobel or Siteco.

The selection of the “luminous spaces” responds to the objective of representing different situations that arise within urban spaces in terms of the use of the building, architectural style, geographical location, population density, etc. In addition, an analysis was carried out according to the classification of the German regional office and planning, which distinguishes cities and municipalities according to the number of inhabitants and the importance they have for their respective region considering small city (5,000- 10,000), medium city (20,000-50,000 inhabitants) and large city (cities between 1000,000-5000.00 inhabitants).

The process of searching for the different “luminous spaces” started from a selection of almost 90 images of which 15 were chosen, the most representative in terms of their architectural style and use of space. The “luminous spaces” selected are:

Luminous space 1 (Figure 3) in a small city.

A road on the outskirts of the city. Functional lighting for public road lighting and accent lighting for façade lighting. The road and the façade have an intense clear illuminance, differing only in color temperature, the road having a cold color temperature and the façade warm.

Luminous space 2 (Figure 4) in a small city.

A footpath near the city. It has functional lighting for public lighting of pedestrian streets and accent lighting highlighting a church tower in the distance. The pedestrian street and the church tower have a dim light illuminance, and both have a warm color temperature.

Luminous space 3 (Figure 5) in a small city.

Building facades around a square. It has accent lighting for façade lighting. The square has a soft light illuminance resulting from the accent lighting, the environment is dark, and it has a warm color temperature.

Luminous space 4 (Figure 6) in a small city.

Building facades in streets of the old town. It has accent lighting for façade lighting. The streets have very dim light illuminance resulting from the accent lighting, the environment is dark and has a warm color temperature.

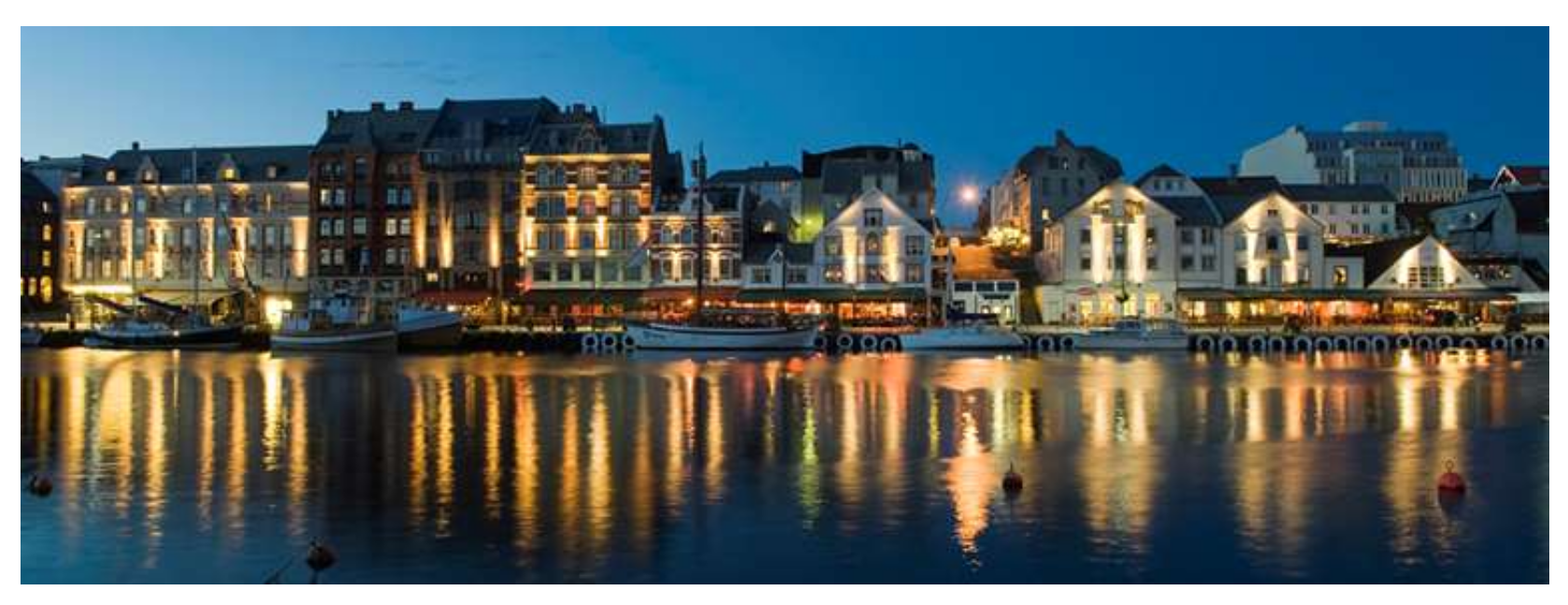

Luminous space 5 (Figure 7) in a medium city.

Building facades on the boardwalk, in a coastal city. It has accent lighting to illuminate the facades of buildings along a boardwalk. The lighting of the facades of buildings stands out, which has clear and bright illuminance, intense and warm color temperature.

Luminous space 6 (Figure 8) in a medium city.

Façade of a single-family home. It has accent lighting to illuminate the façade of the home. The façade lighting has a clear and intense illuminance, the environment is dark and has a warm color temperature.

Luminous space 7 (Figure 9) in a large city.

Commercial building façade. It has accent lighting to light the facade of the commercial building and advertising lighting, the environment is also illuminated with functional lighting for public street lighting. This bright space is perceived as dark despite being illuminated with quality color temperature, where the advertising lighting stands out.

Luminous space 8 (Figure 10) in a large city.

Facade of a museum within the city. It has accent lighting from inside the building through the windows and skylights that overlook the garden, the environment is kept illuminated thanks to the uniform light that comes from the interior and presents two color temperatures, one warm for the facades and another cold for the garden area.

Luminous space 9 (Figure 11) in a large city.

Façade of a public building within the city. It has accent lighting for the façade of the building, the environment is dark and has a warm colour temperature.

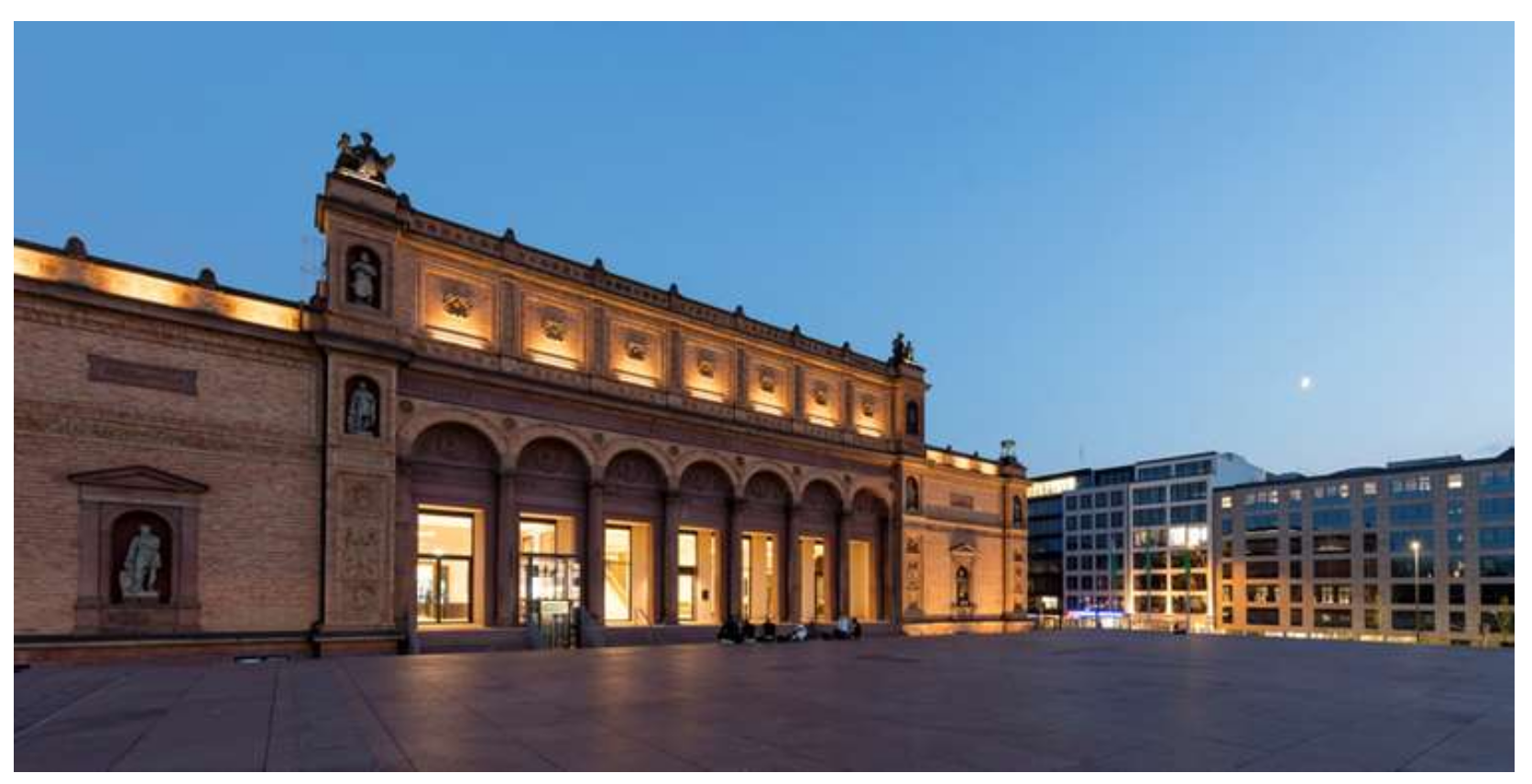

Luminous space 10 (Figure 12) in a large city.

Façade of an art gallery building in front of a square within the city. It has accent lighting for the façade of the building, the environment is dark and has a warm colour temperature.

Luminous space 11 (Figure 13) in a large city.

Bridge and architectural landmark within the city. It has functional lighting for the public lighting of the bridge and accent lighting highlighting the tower of a church in the distance, the environment is dark and has a warm colour temperature.

Luminous space 12 (Figure 14) in a large city.

Façade of a cathedral in a square within the city. It has accent lighting for the cathedral and surrounding buildings, the environment is dark and has a warm colour temperature.

Luminous space 13 (Figure 15) in a large city.

Facades of the sales stalls inside a market within the city. It has functional lighting that is required for work lighting and atmospheric lighting that fulfills the functional lighting in circulation areas, the environment is dark and has a warm colour temperature.

Luminous space 14 (Figure 16) in a large city.

Facade of an office building within the city. It has functional lighting that is required for work lighting and to illuminate the public lighting of the avenue busy with vehicular traffic, the environment is clear and has cold a colour temperature.

Luminous space 15 (Figure 17) in a large city.

Facade of a hotel within the city. It has accent lighting for the hotel building, highlighting architectural elements and prioritizing the main entrance, the environment is dark and has a warm colour temperature.

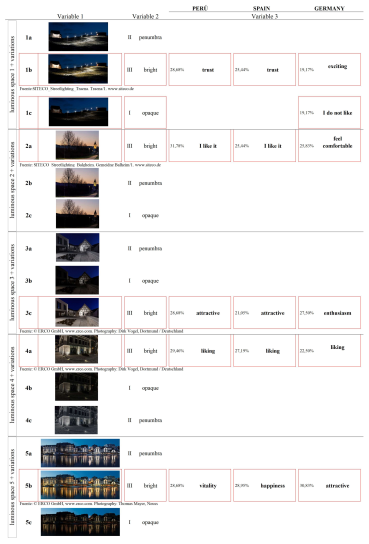

3.2. Technical Descriptors

Variable 2 is the “technical descriptor”. It is urban lighting, the “transmitting” medium, which has a leading role at night, and depends on the different parameters and lighting requirements of each “luminous space”, it transmits a certain stimulus (positive or negative) to users.

Within urban lighting we find different lighting parameters that serve as a tool when developing the lighting design. For this research work we have focused on two of them, illuminance (lux) and colour temperature (Kelvin), since they are the easiest to recognize or differentiate, using basic concepts such as light-dark when talking about illuminance or of warm-cold light when talking about colour temperature.

For this research, 15 “luminous spaces” were shown, and two lighting variations were incorporated into each of them, thus obtaining 3 categories of “luminous spaces” (

Table 1 and

Table 2):

Category I, OPAQUE luminous space (dark, gloomy), those spaces whose urban elements and/or surroundings look dark.

Category II, luminous space PENUMBRA (weak shadow between light and darkness), those spaces where either the environment or part of the urban elements look dark.

Category III, BRIGHT luminous space (clarity, sharpness), those spaces whose urban elements and/or surroundings look clear.

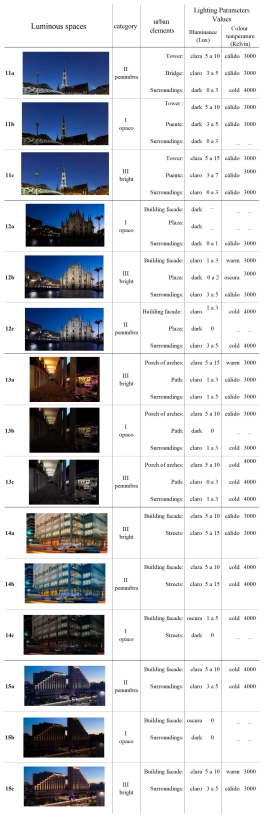

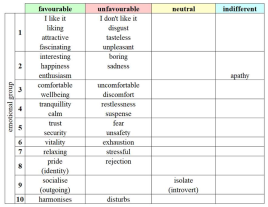

3.3. “ Aesthetic Descriptors”

Variable 3 are the “aesthetic descriptors” or attributes, which are the perception or emotion of the participant (response or reaction) selected to describe the “luminous spaces” presented through the lighting scenes.

The “aesthetic descriptors” are defined based on the work of José Luis Diaz and Enrique O. Flores [

56] , where they presented a detailed list of 328 terms of human emotion in Spanish. A selection of the positive and negative “aesthetic descriptors” that could be used to describe the “luminous spaces” was carried out, this gave rise to the basis for the final list used in the “Online Questionnaire A_COA” with 60 attributes. From this base list, a new filter was made, removing those “aesthetic descriptors” with similar meaning, for example, calm, stillness, serenity.

Furthermore, each “aesthetic descriptor” was analysed, as well as each of its synonyms, choosing only those that best expressed people's emotional reaction to the lighting scenarios. This resulted in a final list of 18 pairs of attributes which were ordered into 10 groups according to their meaning or definition and classified into four categories, which have been called perception categories (favourable, unfavourable, neutral, and indifferent). This final list of attributes was made in the official language of each country, that is, a list of “aesthetic descriptors” was prepared for Peru and Spain in Spanish and another in German for Germany.

Table 3 shows a translation of the “aesthetic descriptors” into English.

3.4. “ Light and Emotions Experience” (COA|COB)

The Survey used to perform this research is made up of two link questionnaires COA and COB and is named “light and emotions experience”. The “aesthetic descriptors” used in COB are a result of the answers to COA.

The COA is the first part of the “light and emotions experience”, using an “aesthetic descriptor” it seeks to obtain a response from the intuitive and spontaneous perception of the participant, it consists of three parts:

Part 1: Relevant general data of the participants such as gender, age, level of training, nationality, place of residence and date.

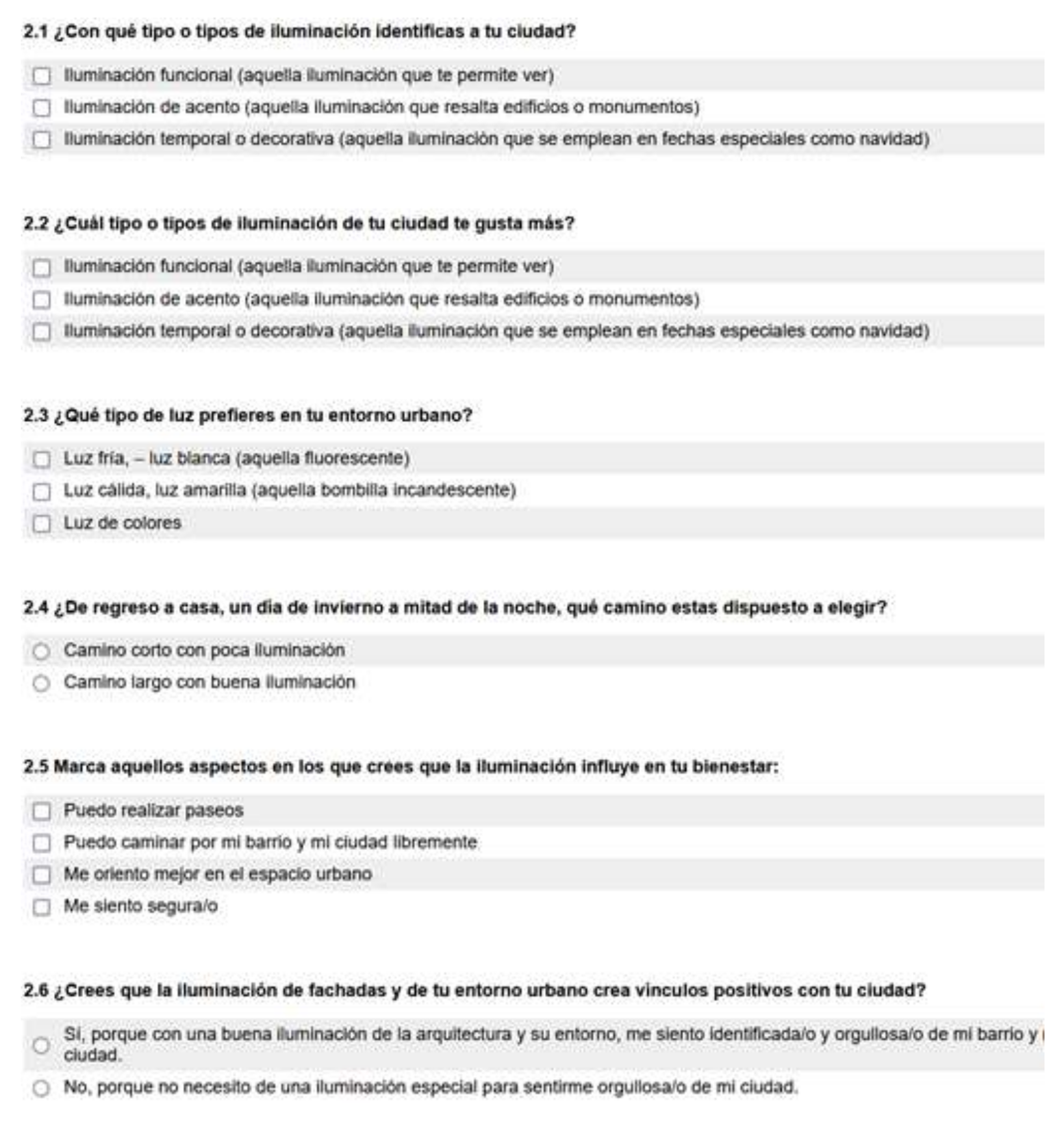

Part 2: Preferences for “luminous spaces”, questions are asked so the participants choose an answer among the predefined options and thus give an opinion about their experience on the type of lighting they relate to, as well as other aspects related to the influence of lighting on their well-being and their connection to the city. (

Figure 18)

An example of this kind of question is:

What kind of lighting would you identify your city with?

- □

Functional lighting (to see)

- □

Accent lighting (to highlight façades and monuments)

- □

Temporary or decorative lighting (only used on specific dates, such as Christmas)

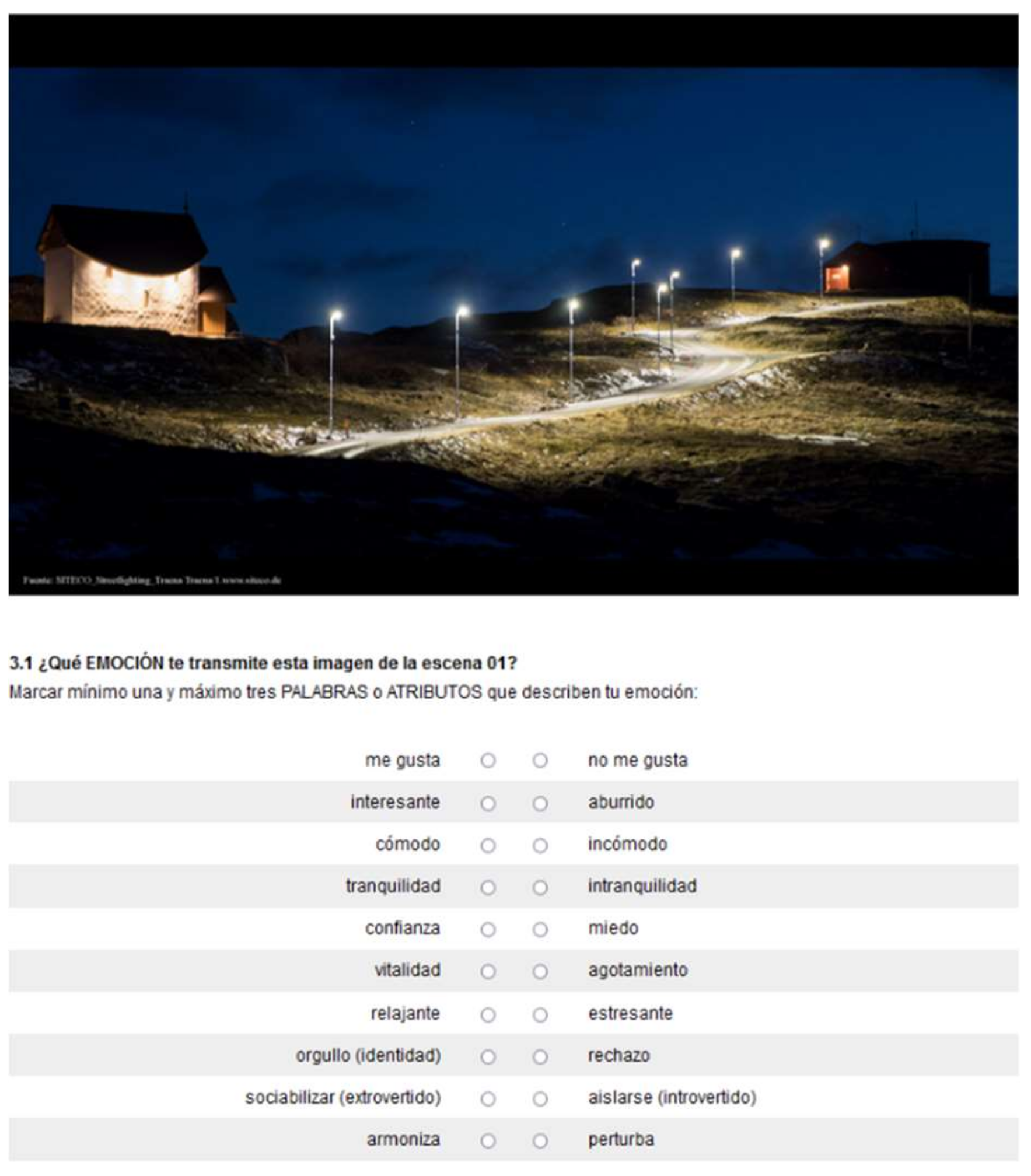

Part 3: A choice of “aesthetic descriptors” that describe the perception of the participants when observing the different “luminous spaces” is made. Here a closed question is asked in combination with an image, where the participant has the possibility of choosing one or more response options. Below, in

Figure 19, the “luminous space 01” is shown as presented in the “light and emotion experience COA”, this was carried out in all the luminous spaces presented from 01 to 15 (image 17).

COB is the second part of the “light and emotions experience”, where we sought to delve deeper into the participants' perception of the “luminous spaces” presented. For this purpose, a questionnaire was developed based on the answers most selected by the participants in the COA, which are accompanied by direct and specific questions about the “image-perception-emotion” linking each of the “luminous spaces” to get a concrete answer. COB consists of three parts:

Part 1: Relevant general data like COA.

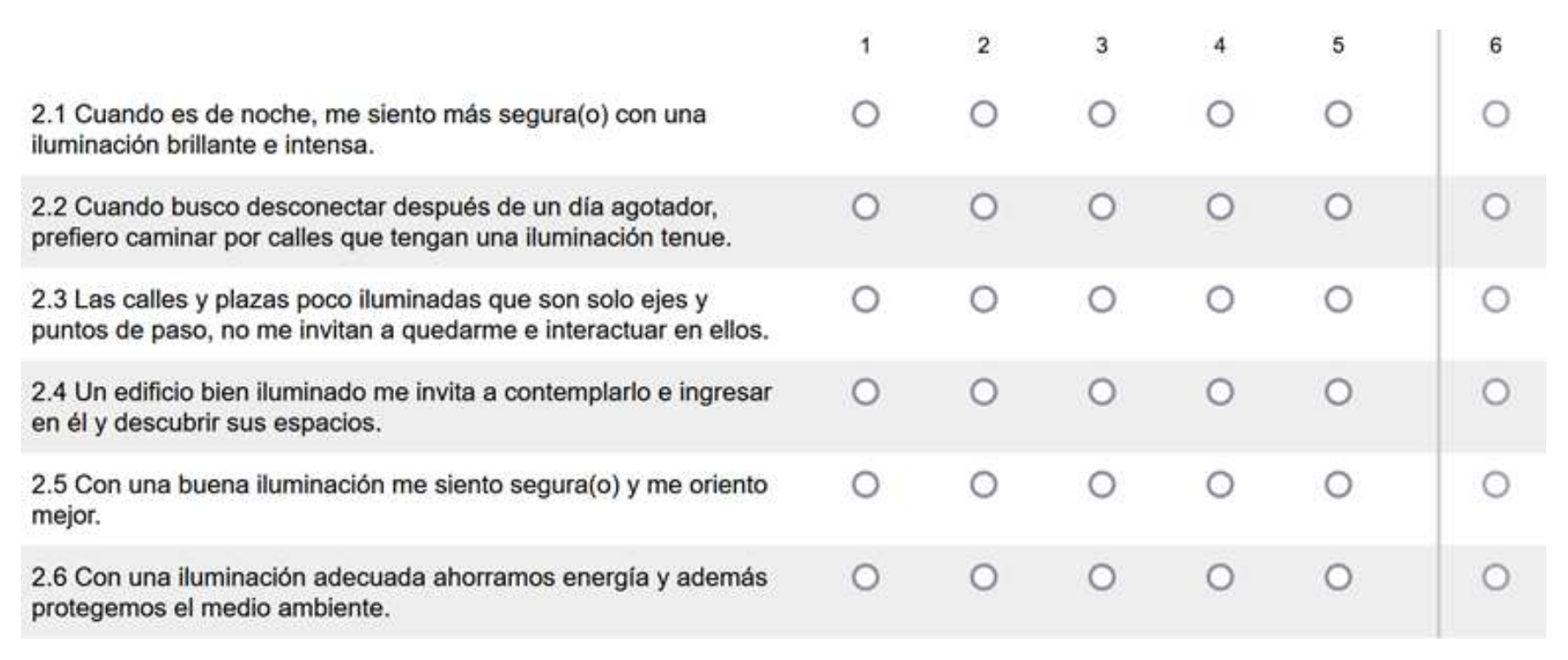

Part 2: Scale questions are formulated so the participant answers whether they agree or disagree with the question asked using a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 means that you do not agree “at all”, 5 means that you “completely” agree, and 6 means that you “don't know” (

Figure 20).

An example of this kind of question is:

At night, I feel safer with bright and intense lighting.

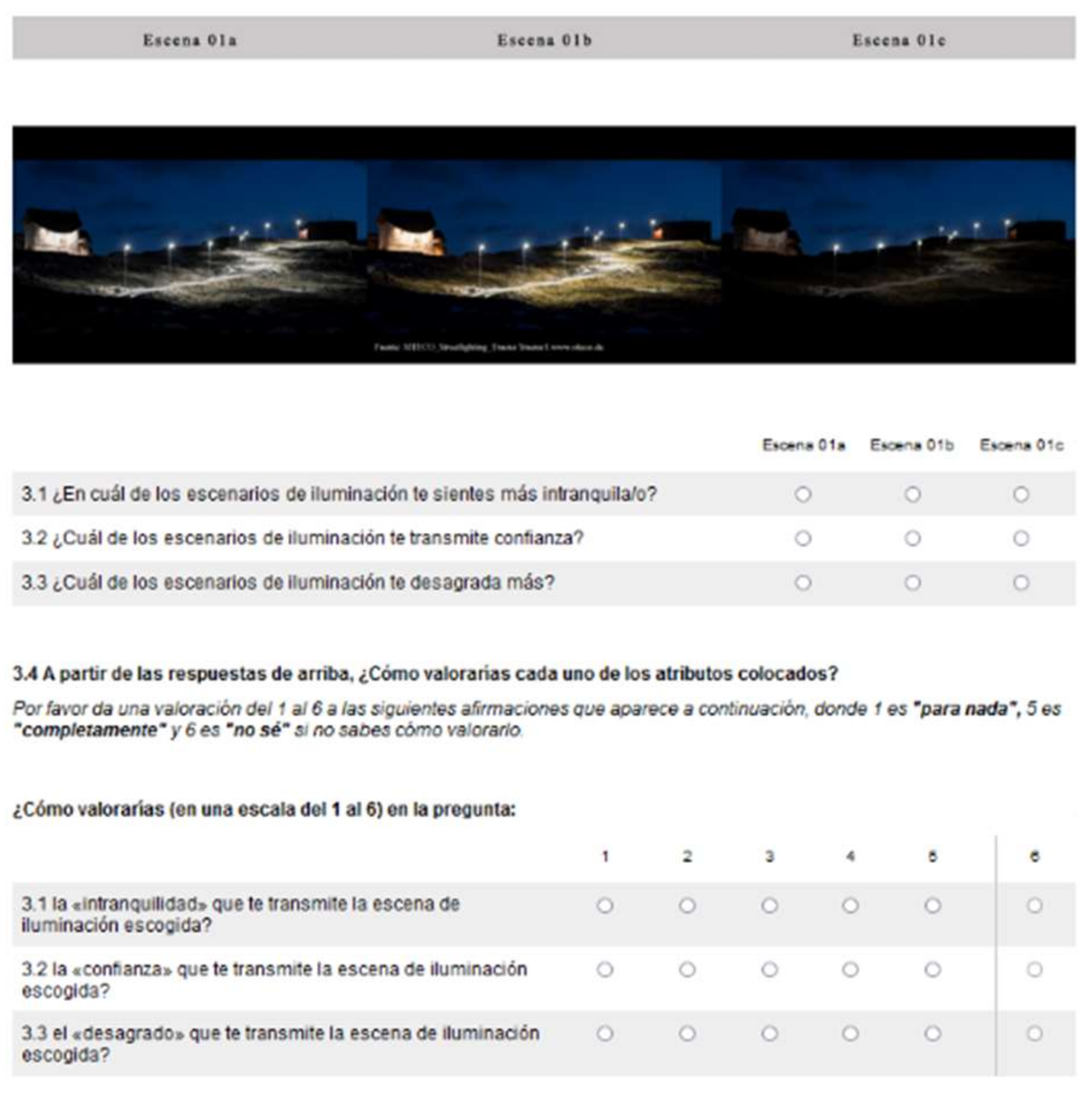

Part 3, Preferences for “luminous spaces”, here 3 “luminous spaces” are presented, with different lighting parameters, along with specific questions, so that the participant can choose the “luminous space” that best suits them linked to the “aesthetic descriptor” of the question asked. In addition, the participant will also be able to give a rating on a scale of 1 to 6 for each “aesthetic descriptor” according to the “luminous space” chosen (

Figure 21).

3.5. Process and Participants, Group Selection

Within the process of developing the online questionnaires, the validity of their content was also carried out by experts or specialists in the subject of lighting, architecture, and emotions, who evaluated the relevance, clarity, and coherence of the test.

The “light and emotions experience” (COA | COB) was carried out in Peru, Spain, and Germany. The choice of these countries was due to personal bond and therefore the ease of accessing information and getting participants. The participants were divided into two groups: group 1, common participants, non-architects or designers, and group 2, architects.

The collaboration of at least 120 people was sought in each of the questionnaires and more than 750 links were distributed, from which the incomplete ones were discarded, leaving 84 participants in the COA and 123 participants in the COB.

3.6. Data Correlation and Validation

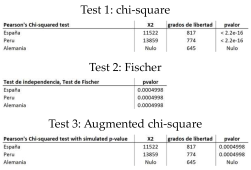

To verify if there is a correlation between the categorical or qualitative variables, “luminous spaces” and the “aesthetic descriptors”, a chi-square test was carried out.

In this test, a margin of error of 0.05 was used and the following hypotheses were proposed:

H0. null hypothesis: the type of lighting does not influence people's emotions.

H1. alternative hypothesis: the type of lighting does influence people's emotions.

After the analysis, it was observed that in most cases in all three countries, the calculated chi-square is greater than the theoretical chi-square, that is, it rejects the null hypothesis, with which it was concluded that the type of lighting does influence people’s emotions or in other words, the observed difference is not a product of chance.

Despite this, two more tests were carried out since in Peru, Spain, and Germany the number of participants in the “light and emotions experience” reached a total of 120 people and does not correspond to a large sample that is needed for chi-square testing. For this reason, a second test was carried out with the Fischer method, which accepts small samples. Finally, to corroborate these results, a third test was carried out, with the chi-square, increasing the number of replications or permutations up to 2000 replications, as shown below (

Table 4).

In all calculations the P-value is less than 0.05, therefore, it can be concluded that there is an association between the variables (“luminous spaces” and “aesthetic descriptors”), the dependent variables.

4. Results

Regarding the profile of the participants, Peru and Spain had a greater participation of females, who represent 58% of the total participants in the COA and 67% of the total participants in the COB, while in Germany, males had the greatest participation with 54% of the total participants in the COA and 62% of the total participants in the COB. According to the age range, there is coincidence between the three countries, since most participants belonged to the age group between 40 and 65 years, which represented 67% of the total participants in the COA and 65% in the COB in Peru and Spain, while in Germany they represented 49% in the COA and 55% in the COB. Furthermore, it was observed that in terms of the results according to nationality in Peru and Spain, up to 8 different nationalities participated, Peruvians had the largest number of participants with 54% in the COA and 45% in the COB. In Germany, 4 different nationalities participated, with Germans standing out in participation with 90% in the COA and 98% in the COB. Likewise, when analysing the results by profession, it is observed that of all the people who participated in these three countries, the vast majority are not architects, which is considered positive since the “light and emotions experience” was directed at the common inhabitant.

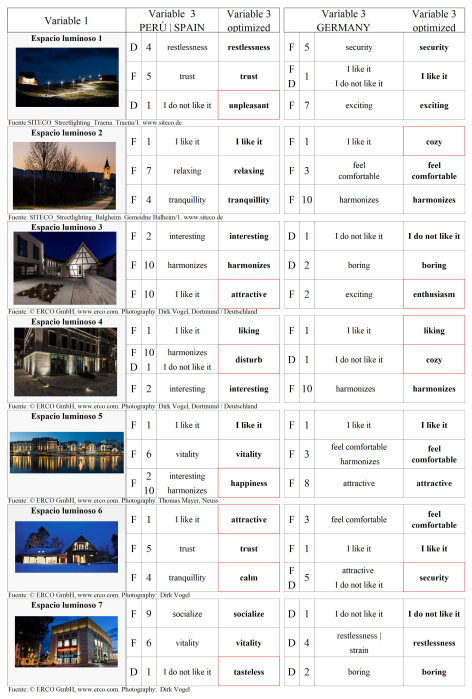

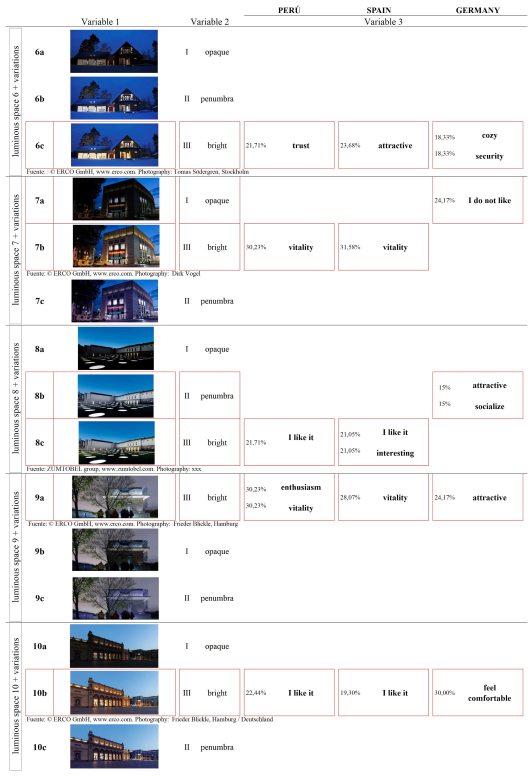

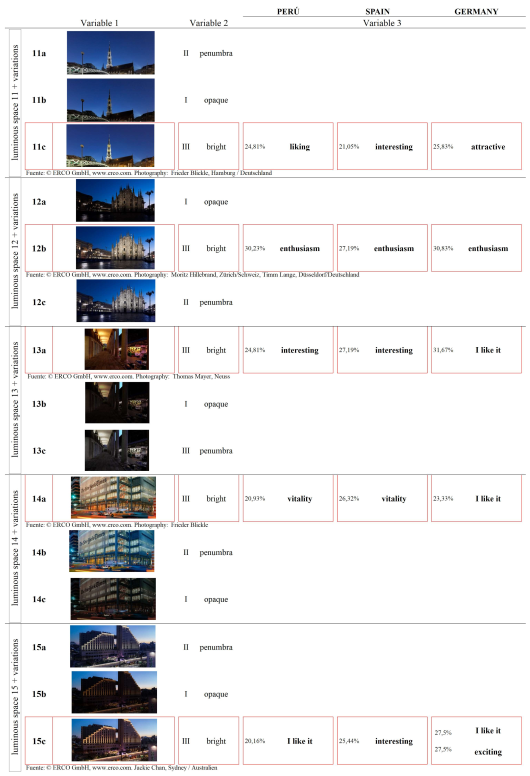

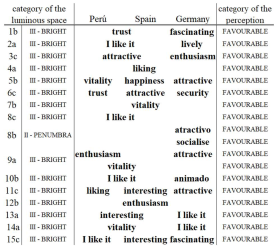

4.1. COA

The main objective of the “light and emotions experience” COA was to find out the participants' perceptions of the “luminous spaces” (variable 1) presented in the questionnaire, by choosing 3 “aesthetic descriptors” (variable 3) as shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6. This resulted in the optimization of the aesthetic descriptors for use in the COB. As can be seen in

Table 4 and

Table 5, column 3 shows the aesthetic descriptors in Spanish, column 4 shows their optimization, column 5 shows the aesthetic descriptors in German and column 6 shows their optimization. As an example, “luminous space 1” (

Table 5) has been rated with two unfavourable aesthetic descriptors, (uneasiness and I don't like it) and with a favourable one (trust) in Peru and Spain, while in Germany they rated it with 3 favourable aesthetic descriptors (safety, I like it and fascinating) and one unfavourable one (I don't like it). After the analysis of these results, the aesthetic descriptors that formed part of the COB were, uneasiness, trust, and dislike (replacing I don't like it) in Peru and Spain; while in Germany they were security, I like it and exciting. The descriptors that were modified are marked in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

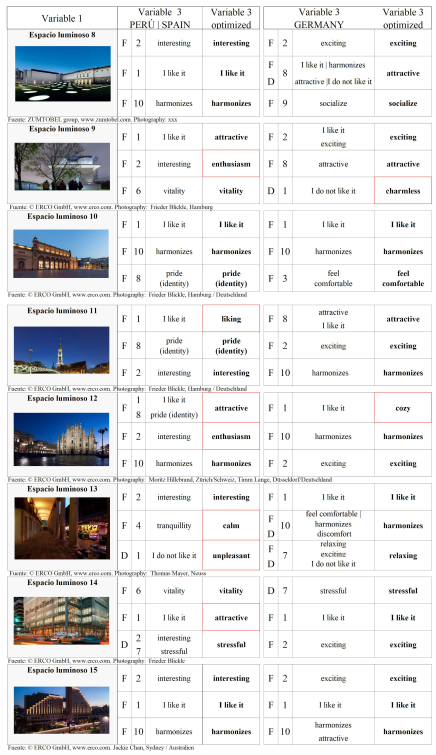

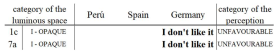

4.2. COB

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 show the selection of the “aesthetic descriptor” in each country according to the variation of the “luminous space”. As an example, in luminous space 1 the selected variations are:

1a, category of perception II – PENUMBRA,

1b, category III – BRIGHT

1c, category I- OPAQUE.

Peru, Spain, and Germany chose the luminous space 1b of category III – BRIGHT to link it to the favourable aesthetic descriptor “trust”, with a majority rating between 4 and 5. While in Germany it was linked to the favourable aesthetic descriptor “exciting” with a rating of 5. With the same number of votes and a rating of 5, Germany also chose the luminous space 1c of category I -OPACO, linking it to the aesthetic descriptor “I don't like it”.

The following tables show the predominant selection for each case.

Table 10 refers to the favourable responses and

Table 11 to unfavourable ones.

After analysing the citizen response to the COB in the three participating countries, the reaction of the participants to the “luminous spaces” is classified based on the size of the city:

In a small city, both Peru, Spain and Germany chose the “luminous space” from category III – BRIGHT to link it to the category of favourable perception. Furthermore, in Germany they chose a category I – OPAQUE to link it to an unfavourable perception category.

In a medium-sized city, both Peru, Spain and Germany unanimously chose the “luminous space” from category III – BRIGHT to link it to the category of favourable perception.

In a large city in Peru and Spain they unanimously chose the luminous space from category III – BRIGHT to link it to the category of favourable perception. However, Germany chose the “luminous space” of category III – BRIGHT to link it to the favourable perception category, but they also chose a “luminous space” from category II – PENUMBRA to link it to a favourable perception category and a “luminous space” of category I – OPAQUE to link it to an unfavourable perception category.

5. Conclusions

The Kansei engineering method has made establishing relationships between the sensations experienced and the physical characteristics of the luminous space possible

From the point of view of outdoor lighting design planning, Kansei methodology can contribute to a better understanding of user needs within the urban space, serving as a guide to specialists when making lighting decisions, and thus meeting their expectations. Therefore, it is considered a very useful and recommended instrument not only from the beginning of lighting projects, but also applicable to lighting master plans.

The method used contributes to a multidisciplinary design approach, performing a simultaneous analysis of all the requirements and design parameters (architectural, psychological, biological, environmental and social) that intervene from the first design phases of the project, which will allow qualitative lighting solutions aimed at user satisfaction with the urban night space.

From a comprehensive point of view, the instrument generated enables identifying not only quantitative values of the urban night space (luminous spaces and technical descriptors) but also qualitative values (aesthetic descriptors), which are both decisive instruments when measuring user satisfaction.

The “Light and emotions experience” showed differences in terms of the gender of the people who participated between the Spanish-speaking countries and Germany, since in Peru and Spain the largest number of participants were female (58% COA | 67% COB). While in Germany males (54% COA | 62% COB) had the greatest participation. On the other hand, very similar results were observed in terms of the age range in these three countries, where the majority ranges between 40 and 65 years (PE-ES 67% COA | 65% COB) (DE 49% COA | 55% COB). Likewise, of all the people who participated in these three countries, the vast majority are not architects or designers, which is considered positive since the experience of light and emotions was basically aimed at the common inhabitant (PE-ES 84% COA | 67% COB) (FROM 85% COA | 98% COB).

The “luminous spaces” generated a similar reaction in Peru, Spain and Germany in terms of the participants' perceptions of the images shown, highlighting: acceptance of category III which has light Illuminance (Em) and a warm or warm-cold colour temperature (k) and rejection of category I, which has dark illuminance (Em) and a warm or cold colour temperature (k).

Considering the “technical descriptors” in a bright space, the combination of lighting parameters that are well received are clear illuminance with a warm or warm-cold colour temperature. But if the “luminous space” has dark illuminance, it will always be perceived in a negative way, regardless of colour temperature.

From the point of view of “aesthetic descriptors”, the majority of people in the three participating countries selected “aesthetic descriptors” in a positive emotional group. Furthermore, participants in Peru and Spain significantly coincided in their preferences regarding bright space not only in the choice of favourable perception, but also in the choice of the aesthetic descriptor. In the case of Germany, like Peru and Spain, they coincide in most of the “luminous spaces” in terms of choosing the favourable perception, but they differ from the emotional group, since they chose another aesthetic descriptor.

In addition, the participants in Germany, unlike Peru and Spain, also chose aesthetic descriptors that belong to a negative emotional group, linking them to two “luminous spaces”.

Regarding the geographical classification of the city and the use of urban space, the participants in Peru, Spain and Germany perceived “luminous spaces” in a small, medium or large city in a similar way. The size of the city or its urban configuration did not play an important role when choosing their preferences. Likewise, regardless of the use or activity of the observed light space, the participants almost always linked favourable “aesthetic descriptors” to those “luminous spaces” where the illuminance is clear and has a warm or warm-cold colour temperature, which shows that people's comfort, “feeling good”, “feeling safe” within the urban space during night-time hours has more to do with lighting than with the urban space itself. In other words, during the night we perceive the city differently than during daylight hours. In this sense, lighting through clear illuminance allows us to see, orient ourselves. and avoid accidents, thus having an important role in our perception, since it allows us to feel safe trusting and confident, etc. In addition, the choice of colour temperature was also important when choosing or rejecting “luminous spaces”, where the majority preferred a warm colour temperature, which is light that relaxes, calms and is preferred by participants.

From a social and geographical perspective, Peru and Spain responded in a very similar way when choosing the “aesthetic descriptors”, where most participants preferred the aesthetic descriptors belonging to the category of favourable perception. Germany, however, chose aesthetic descriptors from the favourable and unfavourable category. What can be stated in general is that Peruvians and Spaniards perceive the urban nocturnal space in a very similar way when identifying it with the category of perception and that despite belonging to different geographical spaces, they are more united by history, culture, and language. Germany, despite its geographical proximity to Spain, sharing the same continent, the same schedule, the same seasons of the year, etc., perceives the urban nocturnal space choosing the category of perception differently. On the other hand, while Peru chose aesthetic descriptors from the favourable perception category for 12 “luminous spaces” from the 15 presented, Spain chose this category for 8 “luminous spaces” and Germany only for 6. This shows that participants in Spain, despite having responded very similarly to participants in Peru, when performing a more detailed analysis, their responses are closer to those of the participants in Germany than to those from Peru. Therefore, it can be stated that the perception of urban nocturnal space by Spaniards and Germans is similar when identifying a space with an “aesthetic descriptor” from a positive or negative emotional group. The perception of Peruvians compared to Germans has significant differences at the level of the perception category and the emotional group. In this sense, it can be concluded that the cultural and geographical aspect will significantly influence people's perception, so it is crucial to take them into account when making decisions regarding the lighting project, as stated in the hypothesis.

The positive perception of warm colour temperatures coincides with the environmental recommendations since this is the least harmful to the environment. Therefore, it is important to take this into account when choosing the colour temperature.

Acknowledgments

Project PID2020-114873RB-C32 (Monitoring of public spaces and the stimuli of urban materials in citizens), financed by MCIN/ AEI /10.13039/501100011033.

References

- C. C. M. Kyba et al., “Artificially lit surface of Earth at night increasing in radiance and extent,” Sci. Adv., vol. 3, no. 11, pp. 1–9, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. U. R. O. S. Tat and S. T. H. E. Sdgs, E u r o s tat supports the sdgs. 2023.

- C. Tonne et al., “Defining pathways to healthy sustainable urban development,” Environ. Int., vol. 146, p. 106236, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Drevet, “The conference on the future of Europe,” Futur. Anal. Prospect., vol. 2020-April, no. 435, pp. 105–113, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Zielinska-Dabkowska and K. Bobkowska, “Rethinking Sustainable Cities at Night: Paradigm Shifts in Urban Design and City Lighting,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 10, p. 6062, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Tavares, D. Ingi, L. Araújo, P. Pinho, and P. Bhusal, “Reviewing the Role of Outdoor Lighting in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 22, p. 12657, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Masullo et al., “An Investigation of the Influence of the Night Lighting in a Urban Park on Individuals’ Emotions,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 14, p. 8556, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Beccali et al., “Energy saving and user satisfaction for a new advanced public lighting system,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 195, pp. 943–957, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Paredes, J. Canny, R. Ko, B. Hartmann, E. Calle, and G. Niemeyer, “Fiat lux - Interactive urban lights for combining positive emotion and efficiency,” in DIS 2016 - Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Fuse, 2016, pp. 785–795. [CrossRef]

- B. N. Silva, M. Khan, and K. Han, “Towards sustainable smart cities: A review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 38, pp. 697–713, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Scorpio et al., “Virtual Reality for Smart Urban Lighting Design: Review, Applications and Opportunities,” Energies, vol. 13, no. 15, p. 3809, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Valetti, F. Floris, and A. Pellegrino, “Renovation of Public Lighting Systems in Cultural Landscapes: Lighting and Energy Performance and Their Impact on Nightscapes,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 509, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Morgan Pattison, M. Hansen, and J. Y. Tsao, “LED lighting efficacy: Status and directions,” Comptes Rendus Phys., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 134–145, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Pérez Vega, K. M. Zielinska-Dabkowska, S. Schroer, A. Jechow, and F. Hölker, “A Systematic Review for Establishing Relevant Environmental Parameters for Urban Lighting: Translating Research into Practice,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 1107, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Jägerbrand, “Development of an Indicator System for Local Governments to Plan and Evaluate Sustainable Outdoor Lighting,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 1506, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Calvillo Cortés and L. E. Falcón Morales, “Emotions and the Urban Lighting Environment: A Cross-Cultural Comparison,” SAGE Open, vol. 6, no. 1, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, and P. G. Enticott, “Impact of built environment design on emotion measured via neurophysiological correlates and subjective indicators: A systematic review,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 66, p. 101344, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Razmara, H. Asadpour, and M. Taghipour, “Healing landscape: How healing parameters in different special organization could affect user’s mental health?,” A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 269–283, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y.-K. Lee, C.-K. Lee, J. Choi, S.-M. Yoon, and R. J. Hart, “Tourism’s role in urban regeneration: Examining the impact of environmental cues on emotion, satisfaction, loyalty, and support for Seoul’s revitalized Cheonggyecheon stream district,” J. Sustain. Tour., vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 726–749, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Kraus, “Color as a Psychological Agent to Perceived Indoor Environmental Quality,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2019, vol. 603, no. 5. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Guzzo, C. Suess, and T. S. Legendre, “Biophilic design for urban hotels – prospective hospitality employees’ perspectives,” Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 2914–2933, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Magera and N. Ermilov, “Factors affecting the emotions of Moscow Metro passengers,” in E3S Web of Conferences, 2023, vol. 402. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Castro-Toledo, J. O. Perea-García, R. Bautista-Ortuño, and P. Mitkidis, “Influence of environmental variables on fear of crime: Comparing self-report data with physiological measures in an experimental design,” J. Exp. Criminol., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 537–545, 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. Turekulova, A. D. Kovatchev, and G. R. Iskhojanova, “Methodological approach to creating an urban lighting atmosphere with regard to human needs,” Spatium, no. 43, pp. 16–25, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peter. Robert. Boyce, “Light, lighting and human health,” Light. Res. Technol., vol. 54, no. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. V. Mazuelos, E. M. Chavez, M. A. V. Zuñiga, and S. M. Chavez, “Systematized care environments for children under 5 years of age | Ambientes sistematizados de atención para niños menores de 5 años,” RISTI - Rev. Iber. Sist. e Tecnol. Inf., vol. 2021, no. E44, pp. 203–209, 2021.

- Y. Wei, Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, and C. Liu, “A Study of the Emotional Impact of Interior Lighting Color in Rural Bed and Breakfast Space Design,” Buildings, vol. 13, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Edensor, “Light design and atmosphere,” Vis. Commun., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 331–350, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Masullo et al., “An Investigation of the Influence of the Night Lighting in a Urban Park on Individuals’ Emotions,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. MacCheroni, G. Salvadori, F. Leccese, and G. Tambellini, “Why Transforming Cities Should Rethink the Scale of Urban Lighting,” 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kevin Lynch, “The Image of the City.” Cambridge, Mass., 1960.

- Slater, and M. Sloane, “Social Research in Design,” no. October, p. 37, 2014.

- M. Leandro Rojas, “Ambiente, Conducta y Sostenibilidad. Estado de la cuestión sobre psicología ambiental,” 2011. Available online: http://www.iip.ucr.ac.cr/sites/default/files/contenido/informe6.pdf.

- M. N. Molina González, Bienestar, espacios y percepciones. Diseño a través del tacto. 2019.

- Beaven, Space, light and allegiance in the piazza di spagna in the seventeenth century. 2021.

- A. Portnov, R. Saad, T. Trop, D. Kliger, and A. Svechkina, “Linking nighttime outdoor lighting attributes to pedestrians’ feeling of safety: An interactive survey approach,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 11 Novembe, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Bourgeois, The Genesis of Salk Institute. 2013.

- H. Medhat Assem, L. Mohamed Khodeir, and F. Fathy, “Designing for human wellbeing: The integration of neuroarchitecture in design – A systematic review,” Ain Shams Eng. J., vol. 14, no. 6, p. 102102, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Abbas, D. Kumar, and N. Mclachlan, “The psychological and physiological effects of light and colour on space users,” in Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology - Proceedings, 2005, vol. 7 VOLS, pp. 1228–1231. [CrossRef]

- S. Fotios and M. Johansson, “Appraising the intention of other people: Ecological validity and procedures for investigating effects of lighting for pedestrians,” Light. Res. Technol., vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 111–130, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Cherubino Martinez-Levy et al., “Consumer Behaviour through the Eyes of Neurophysiological Measures: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends,” Comput. Intell. Neurosci., vol. 2019, p. 1976847, 2019. Available online: https://pubmedncbinlmnihgov/31641346/.

- C. C. Hsu, S. C. Fann, and M. C. Chuang, “Relationship between eye fixation patterns and Kansei evaluation of 3D chair forms,” Displays, vol. 50, pp. 21–34, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Hartono, “The modified Kansei Engineering-based application for sustainable service design,” Int. J. Ind. Ergon., vol. 79, p. 102985, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Su, S. Yu, J. Chu, Q. Zhai, J. Gong, and H. Fan, “A novel architecture: Using convolutional neural networks for Kansei attributes automatic evaluation and labeling,” Adv. Eng. Informatics, vol. 44, p. 101055, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Nagamachi, “Kansei Engineering: A new ergonomic consumer-oriented technology for product development,” Int. J. Ind. Ergon., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 3–11, Jan. 1995. [CrossRef]

- Llinares, F. Bisegna, and V. Blanca-Giménez, “Affective evaluation of the luminous environment in university classrooms,” J. Environ. Psychol., vol. 58, pp. 52–62, Aug. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Castilla, C. Llinares, F. Bisegna, and V. Blanca-Giménez, “Emotional evaluation of lighting in university classrooms: A preliminary study,” Front. Archit. Res., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 600–609, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, F. Liu, and J. Ye, “A product form design method integrating Kansei engineering and diffusion model,” Adv. Eng. Informatics, vol. 57, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Ren, F. Guo, M. Hu, Q. Qu, and F. Li, “A consumer-oriented kansei evaluation model through online product reviews,” J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 10997–11012, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Cong, C.-H. Chen, X. Meng, Z. Xiang, and L. Dong, “Conceptual design of a user-centric smart product-service system using self-organizing map,” Adv. Eng. Informatics, vol. 55, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Calvillo Cortés, “Luz y emociones : Estudio sobre la influencia de la iluminación urbana en las emociones; tomando como base el diseño emocional.,” UPC, 2010.

- G. Yu, J. Tang, J. Na, and T. Ma, “Nighttime as Experiences: The Influence of Perceived Value on Urban Waterfront Night Cruise Loyalty,” SAGE Open, vol. 12, no. 2, 2022. [CrossRef]

- 53. B. A. Pfleeger, S.L.; Kitchenham, “Principles of survey research: Part 1: Turning lemons into lemonade.,” 2001.

- A. Tang, M. A. Babar, I. Gorton, and J. Han, “A survey of architecture design rationale,” J. Syst. Softw., vol. 79, no. 12, pp. 1792–1804, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Solomon, “Conducting Web-based surveys,” Pract. Assessment, Res. Eval., vol. 7, no. 19, pp. 1–5, 2001.

- E. O. F. José Luis Díaz, “La estructura de la emoción humana: Un modelo cromático del sistema afectivo.,” Historia Santiago., vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 20–35, 2001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).