Submitted:

15 May 2024

Posted:

15 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

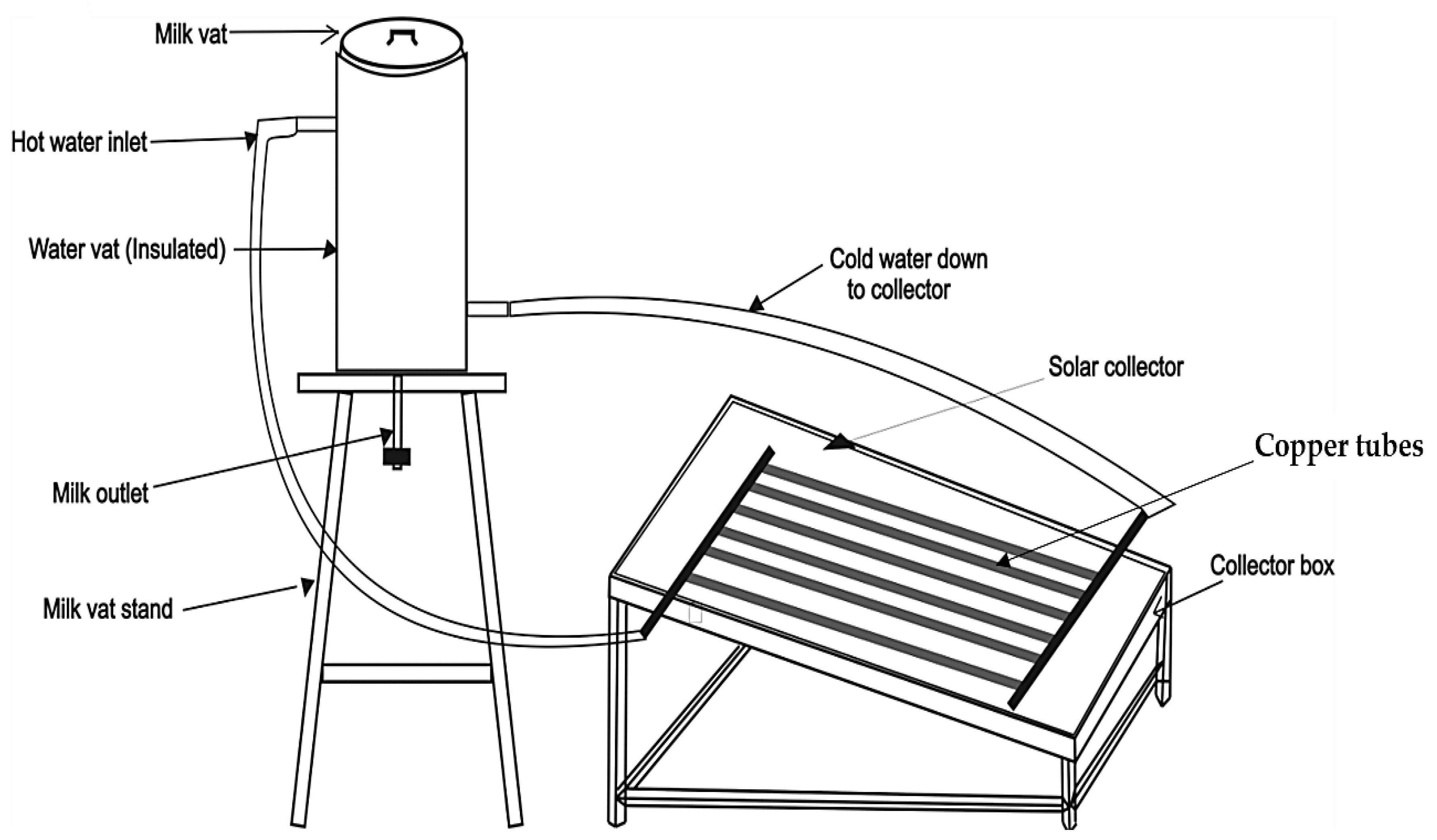

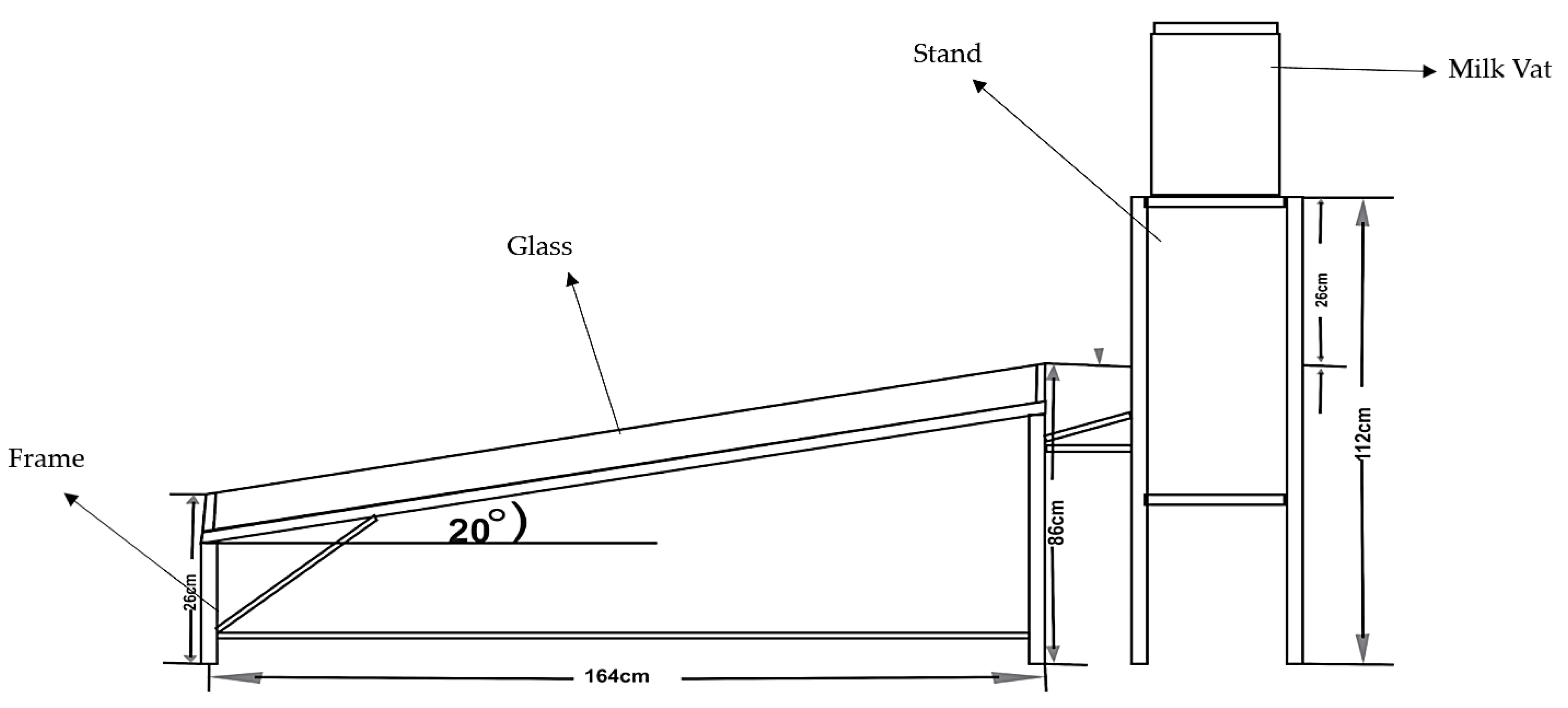

2.1. Design and Fabrication of the Pasteurization System

2.1.1. Flat Plate Solar Collector

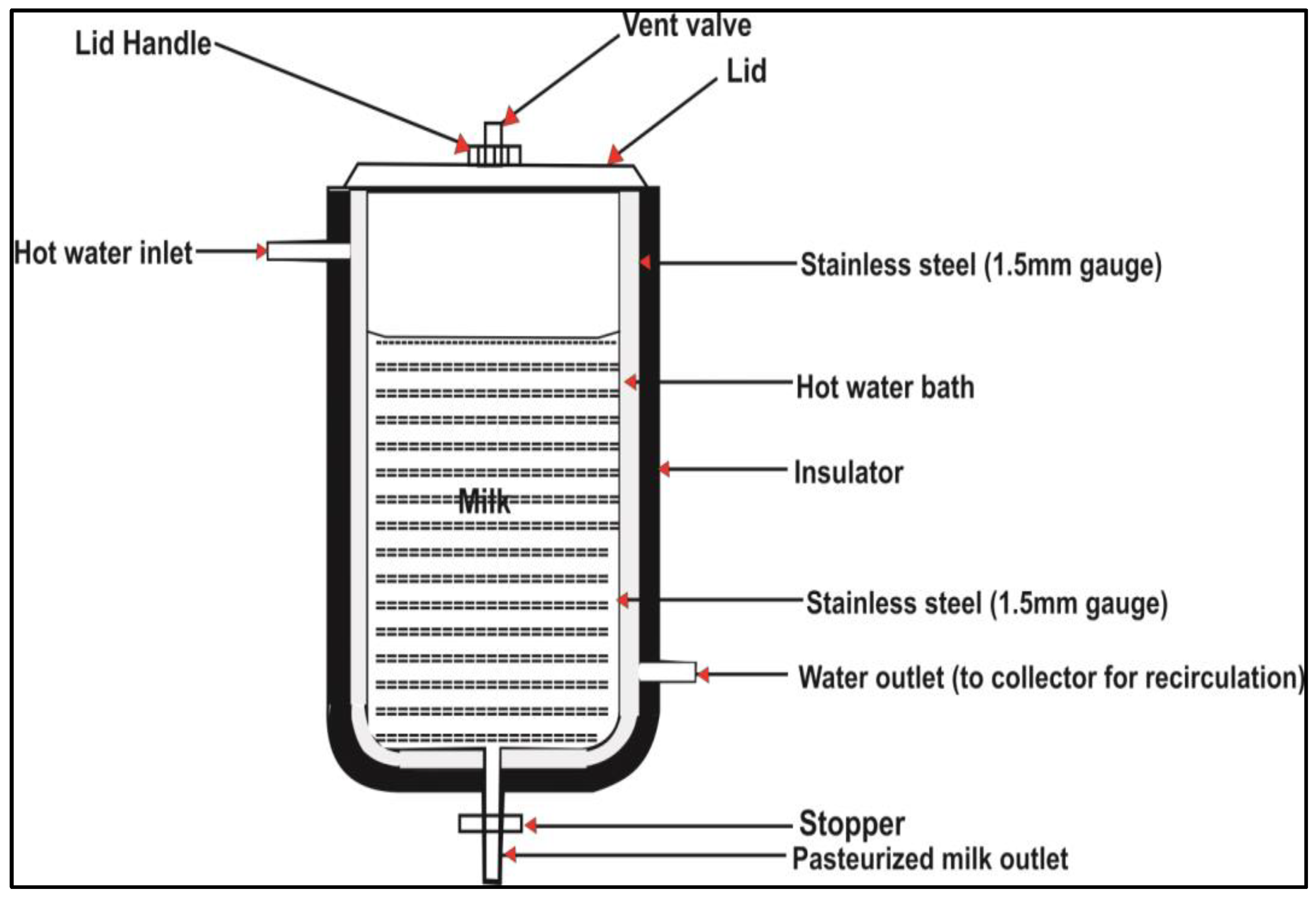

2.1.2. Milk Vat

2.2. Principles of Operation of the Solar Pasteurizer

2.3. Experimental Set-Up and Evaluation of the Performance of Solar Milk Pasteurizer

Location of Trial

2.4. The Climate of Navrongo

2.5. Source of Milk Samples

2.6. Milk Pasteurization

2.7. Microbial Analysis of Pasteurized and Unpasteurized Milk

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

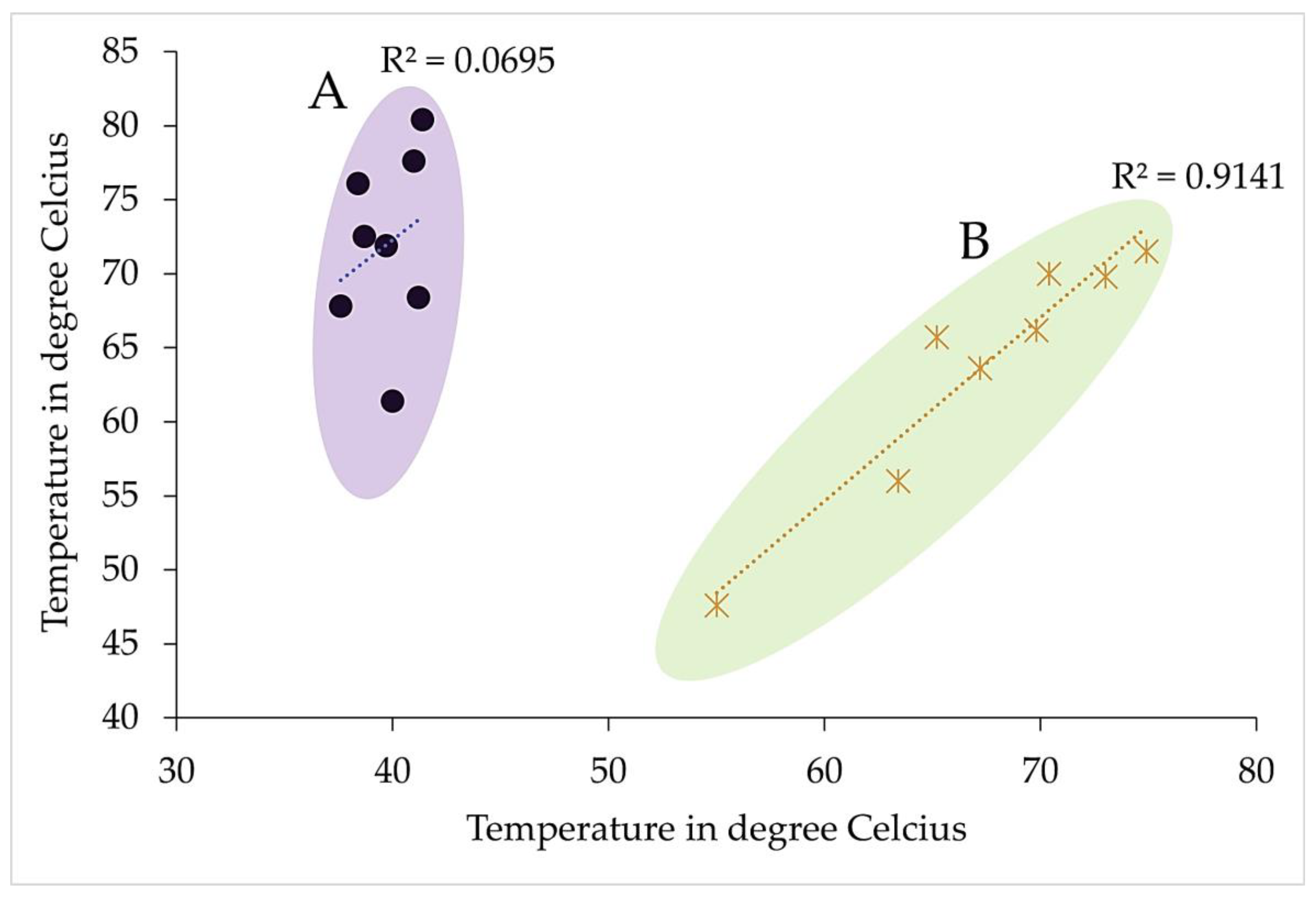

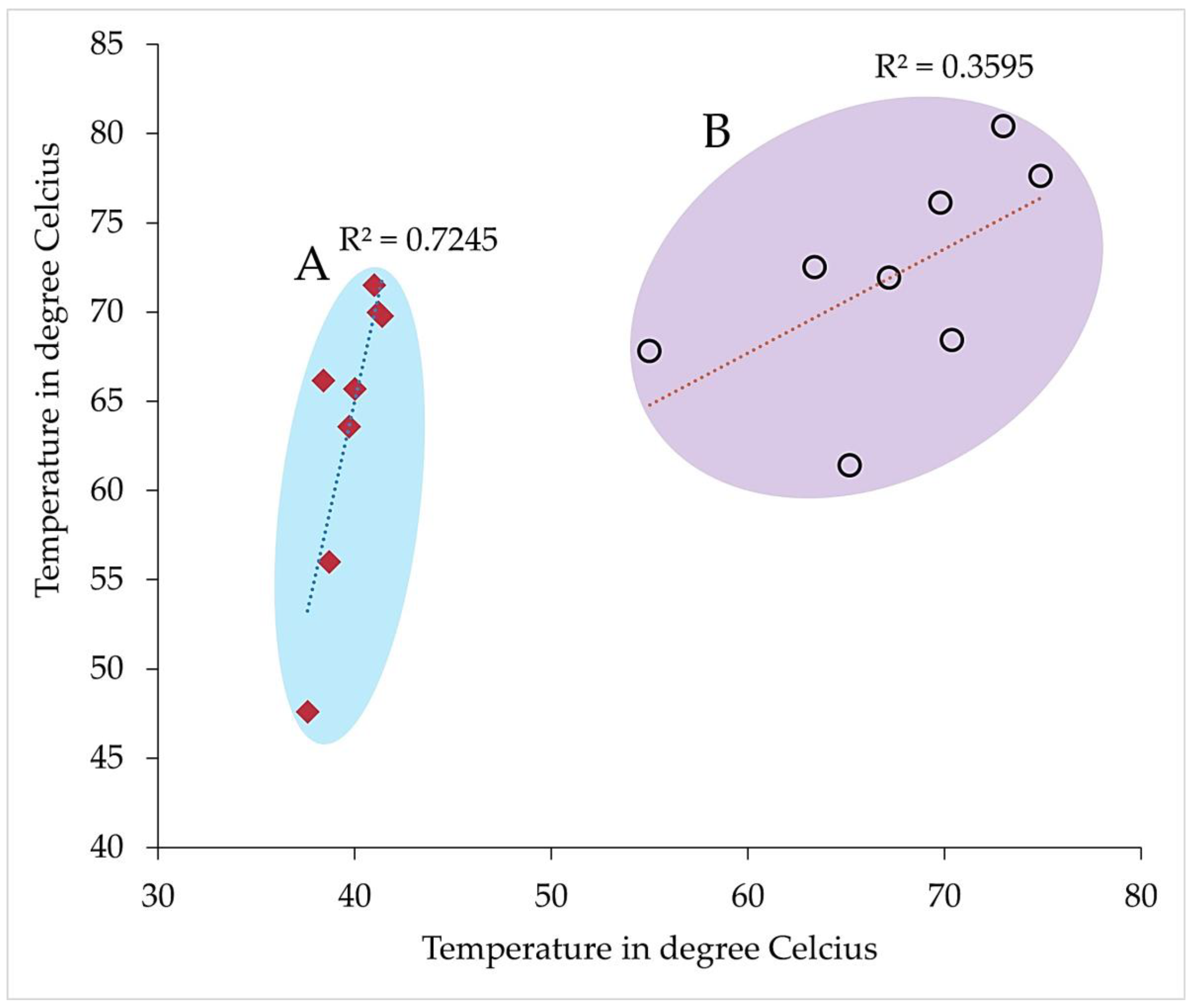

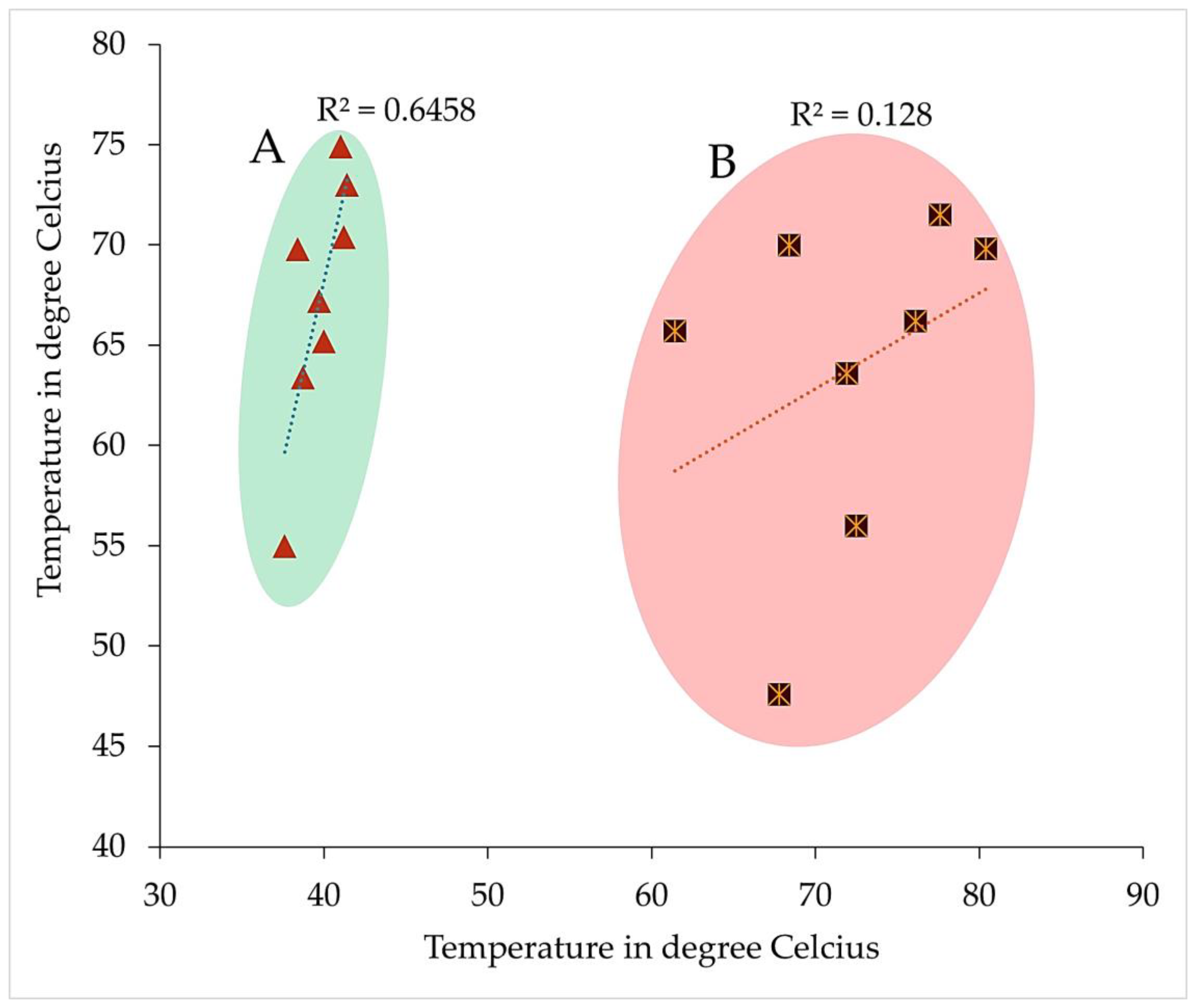

3.1. Maximum Attainable Temperatures during Solar Pasteurization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interests

References

- Arnold, N., (2019). How Is Pasteurization Used to Process Food? Food Science and Technology, 315.

- Escuder-vieco, D., Espinosa-martos, I., Rodríguez, J. M., & Corzo, N. (2018). High-Temperature Short-Time Pasteurization System for Donor Milk in a Human Milk Bank Setting. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9(May). [CrossRef]

- Zufall, B. C., & Wackerbauer, K. (2018). The Biological Impact of Flash Pasteurization Over a Wide Temperature Interval. 106(May 2000), 163–168. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. W., & Haenlein, G. F. W. (2013). Milk and Dairy Products in Human Nutrition: Production, Composition and Health., November 2017, 1–700. [CrossRef]

- Guetouache, M., Guessas, Bettache, Medjekal, & Samir. (2014). Composition and nutritional value of raw milk. Issues in Biological Sciences and Pharmaceutical Research, 2(10), 115–122. [CrossRef]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H., Rejman, K., Laskowski, W., & Czeczotko, M. (2019). Milk and Dairy Products and Their Nutritional Contribution to the Average Polish Diet. Nutrients, 11(8), 1771. [CrossRef]

- Yvan Chouinard, P., & Girard, C. L. (2014). From the Editors—Nutritional interest of milk and dairy products: Some scientific data to fuel the debate. Animal Frontiers, 4(2), 4–6. [CrossRef]

- LeJeune, J. T., & Rajala-Schultz, P. J. (2009). Unpasteurized Milk: A Continued Public Health Threat. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 48(1), 93–100. [CrossRef]

- Lucey, J. A. (2015). Raw Milk Consumption: Risks and Benefits. Nutrition Today, 50(4), 189–193. [CrossRef]

- Vasavada, P. C. (1988). Pathogenic Bacteria in Milk — A Review. Journal of Dairy Science, 71(10), 2809–2816. [CrossRef]

- Kaferstein, F., & Abdussalam, M. (1999). Policy and Practice: Food Safety in the 21st Century. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 77(4), 347–351.

- Bari, M. L., Grumezescu, A., Ukuku, D. O., Dey, G., & Miyaji, T. (2017). New food processing technologies and food safety. Journal of Food Quality, 2017, 2–4. [CrossRef]

- Uyttendaele, M., Franz, E., & Schlüter, O. (2015). Food safety, a global challenge. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(1), 2–7. [CrossRef]

- https://www.cdc.gov/, 2014.

- Vranješ, A. P., Popović, M., & Jevtić, M. (2015). Raw milk consumption and health. Srpski Arhiv Za Celokupno Lekarstvo, 143(1–2), 87–92. [CrossRef]

- Donkor, E., Aning, K., & Quaye, J. (2010). Bacterial contaminations of informally marketed raw milk in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal, 41(2), 58–61. [CrossRef]

- Fatouma Mohamed, A. latif, AE, F., AA, O., CN, S., A, M., A, M., MK, S., & S, Y. (2017). Evaluation of Microbiological Quality of Raw Milk from Farmers and Dairy Producers in Six Districts of Djibouti. Journal of Food Microbiology, Safety & Hygiene, 02(03). [CrossRef]

- Verraes, C., Claeys, W., Cardoen, S., Daube, G., De Zutter, L., Imberechts, H., Dierick, K., & Herman, L. (2014). A review of the microbiological hazards of raw milk from animal species other than cows. International Dairy Journal, 39(1), 121–130. [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Kwarteng, J., Akabanda, F., Agyei, D. and Jespersen, L., 2020. Microbial safety of milk production and fermented dairy products in Africa. Microorganisms, 8(5), p.752.

- Orwa, J. D., Matofari, J. W., & Muliro, P. S. (2017). Handling practices and microbial contamination sources of raw milk in rural and peri urban small holder farms in Nakuru County, Kenya. International Journal of Livestock Production, 8(1), 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Cempírková, R. (2007). Contamination of cow’s raw milk by psychrotrophic and mesophilic microflora in relation to selected factors. Czech Journal of Animal Science, 52(11), 387–393. [CrossRef]

- Reta, M. A., Bereda, T. W., & Alemu, A. N. (2016). Bacterial contaminations of raw cow’s milk consumed at Jigjiga city of Somali regional state, Eastern Ethiopia. International Journal of Food Contamination, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Agyei, D., Owusu-Kwarteng, J., Akabanda, F. and Akomea-Frempong, S., 2020. Indigenous African fermented dairy products: Processing technology, microbiology and health benefits. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 60(6), pp.991-1006.

- Ciochetti, D. A., & Metcalf, R. H. (1984). Pasteurization of naturally contaminated water with solar energy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 47(2), 223-228.

- Asumadu-sarkodie, S., & Owusu, P. A. (2016). A review of Ghana’ s solar energy potential. AIMS Energy, 4(September), 675–696. [CrossRef]

- Adra, F. (2014). Renewable Energy – An Eco-Friendly Alternative? Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, July.

- Al-hilphy, A. R. S., & Ali, H. I. (2013). Milk Flash Pasteurization by the Microwave and Study its Chemical, Microbiological and Thermo Physical Characteristics. 4(7). [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G. L. (2019). Thermosyphon circulation in solar collectors. Solar Energy, 24(February), 191–198. [CrossRef]

- Webster, T. (2015). Thermosiphon water heaters with heat exchangers Experimental Evaluation of Solar Thermosyphons with Heat Exchangers? Solar Energy, 38(July), 219–231.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Navrongo, 2023.

- APHA. 1992. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 18th edition. American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA) and Water Pollution Control Federation (WPCF), Washington, DC.

- Boye, J.I. and Arcand, Y., 2016. Current Trends in Green Technologies in Food Production and Processing. Sustainable Food and Beverage Industries: Assessments and Methodologies, p.1.

- Regattieri, A., Piana, F., Bortolini, M., Gamberi, M. and Ferrari, E., 2016. Innovative portable solar cooker using the packaging waste of humanitarian supplies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 57, pp.319-326.

- Manju, S. and Sagar, N., 2017. Progressing towards the development of sustainable energy: A critical review on the current status, applications, developmental barriers and prospects of solar photovoltaic systems in India. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 70, pp.298-313.

- Das, S.R., 2008. Health impact assessment from food and water at BUET student dormitories.

- Jain, G., Singh, C., Coelho, K. and Malladi, T., 2017. Long-term implications of humanitarian responses: The case of Chennai.

- Brett, J., Kelton, D., Majowicz, S.E., Snedeker, K. and Sargeant, J.M., 2011. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of pasteurization on milk vitamins, and evidence for raw milk consumption and other health-related outcomes. Journal of food protection, 74(11), pp.1814-1832.

- Wilson, G.S., 1943. The pasteurization of milk. British medical journal, 1(4286), p.261.

- Franco, Judith & Saravia, Luis & Javi, Verónica & Caso, Ricardo & Fernandez, Carlos. (2008). Pasteurization of goat milk using a low-cost solar concentrator. Solar Energy. 82. 1088-1094. [CrossRef]

- Walstra P., Wouters J.T.M., Geurts T.J., Dairy Science and Technology, 2006, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA, pp. 497–512.

- da Silva, G. C., Tiba, C., & Calazans, G. M. T. (2016). Solar pasteurizer for the microbiological decontamination of water. Renewable Energy, 87, 711-719.

- Wayua, F. O., Okoth, M. W., & Wangoh, J. (2013). Design and performance assessment of a flat-plate solar milk pasteurizer for arid pastoral areas of kenya. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 37(2), 120-125.

- Ciochetti, D.A. and Metcalf, R.H., 1984. Pasteurization of naturally contaminated water with solar energy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 47(2), pp.223-228.

- Mulwa DWK (2009). Microbiological quality of camel milk along the market chain and its correlation with food-borne illness among children and young adults in Isiolo, Kenya. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

- KEBS (2007b); “Drinking Water – specification”, Kenya standard, KS 459-1: 2007, Third Edition, Pgs 1-7.

- Choudhary, R., & Bandla, S. (2012). Ultraviolet pasteurization for food industry. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering, 2(1), 12-15.

- Sepulveda, D. R., Góngora-Nieto, M. M., Guerrero, J. A., & Barbosa-Cánovas, G. V. (2005). Production of extended-shelf-life milk by processing pasteurized milk with pulsed electric fields. Journal of Food Engineering, 67(1-2), 81-86.

- Dag, D., Singh, R. K., & Kong, F. (2020). Developments in radio frequency pasteurization of food powders. Food Reviews International, 1-18.

- Silva, F. V., & Gibbs, P. A. (2012). Thermal pasteurization requirements for the inactivation of Salmonella in foods. Food Research International, 45(2), 695-699.

| Time/GMT | Average Ambient Temp. /°C | Average collector Temp. / °C | Average Water Temp. / ˚C | Average Milk Temp. / °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10:00 | 37.6 ±0.89 | 67.8 ±7.73 | 55.0 ±8.03 | 47.6 ±4.93 |

| 11:00 | 38.7 ±1.20 | 72.5 ±4.66 | 63.4 ±4.04 | 56.0 ±6.44 |

| 12:00 | 38.4 ±5.41 | 76.1 ±2.13 | 69.8 ±4.09 | 66.2 ±2.59 |

| 13:00 | 41.4 ±0.55 | 80.4 ±2.71 | 73.0 ±3.39 | 69.8 ±2.28 |

| 14:00 | 41.0 ±0.82 | 77.6 ±5.02 | 74.9 ±2.39 | 71.5 ±1.91 |

| 15:00 | 41.2 ±0.45 | 68.4 ±6.88 | 70.4 ±3.85 | 70.0 ±1.58 |

| 16:00 | 40.0 ±0.00 | 61.4 ±4.98 | 65.2 ±2.17 | 65.7 ±2.49 |

| Total average | 39.7 ±2.45 | 71.9 ±7.87 | 67.2 ±7.50 | 63.6 ±8.92 |

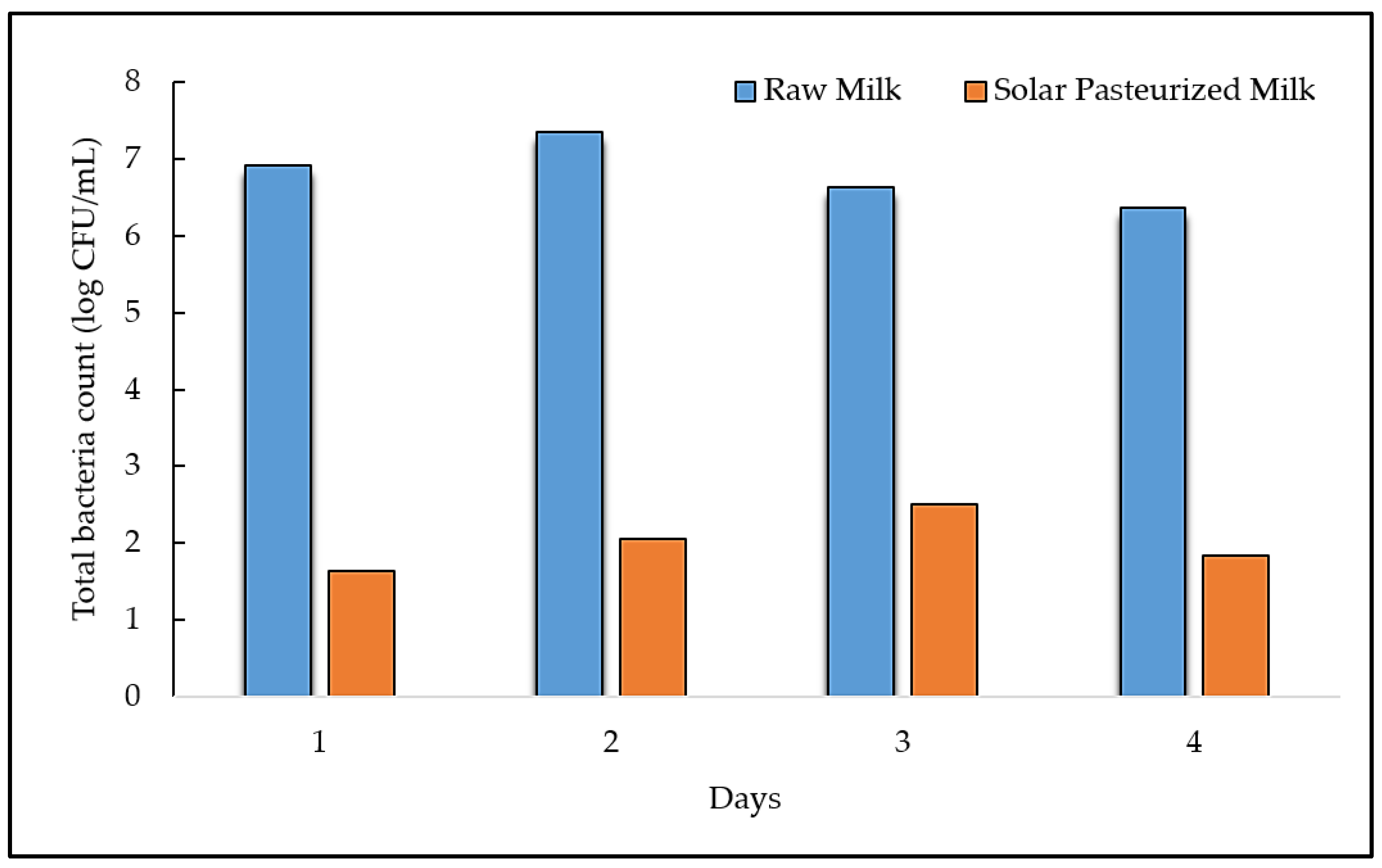

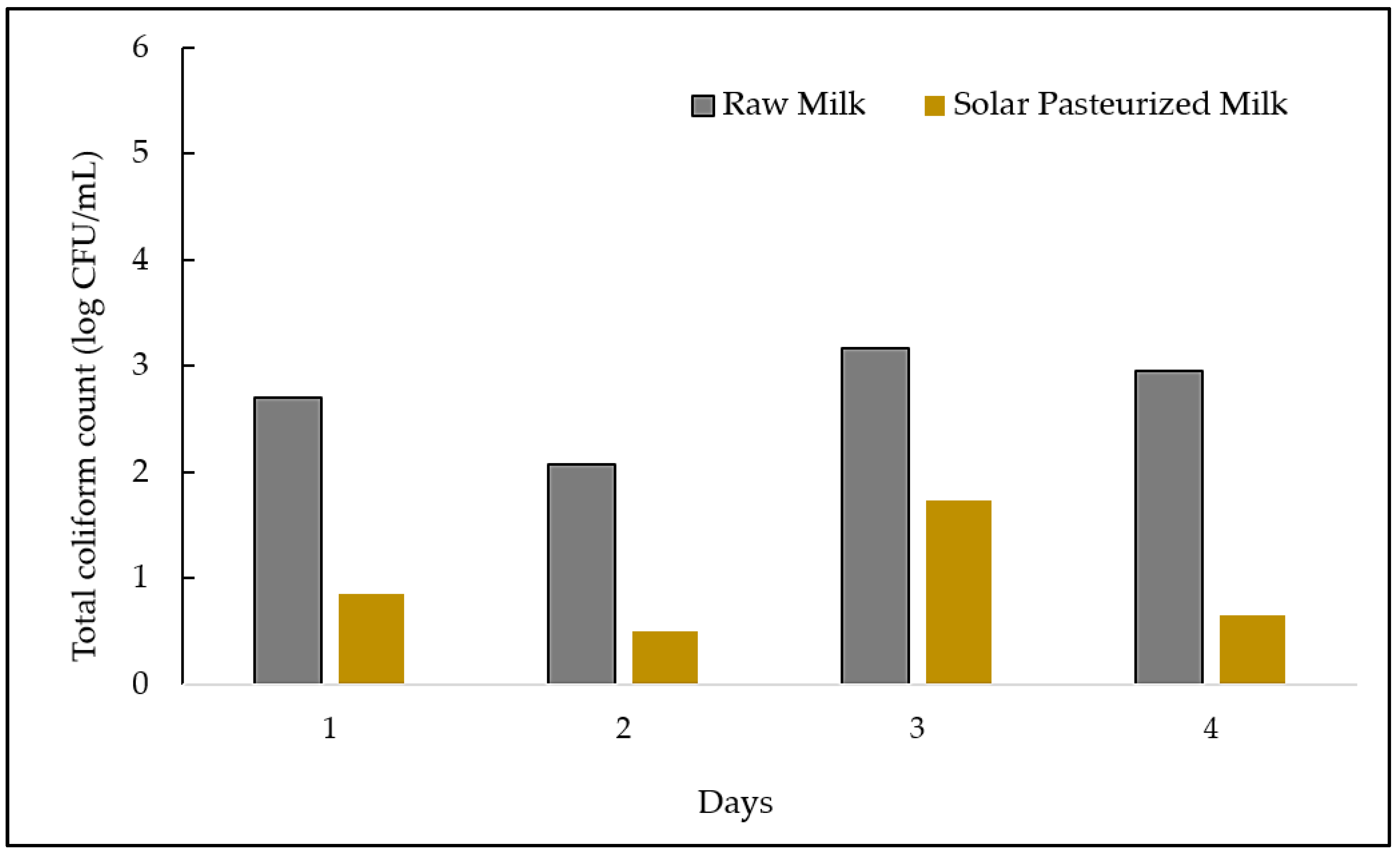

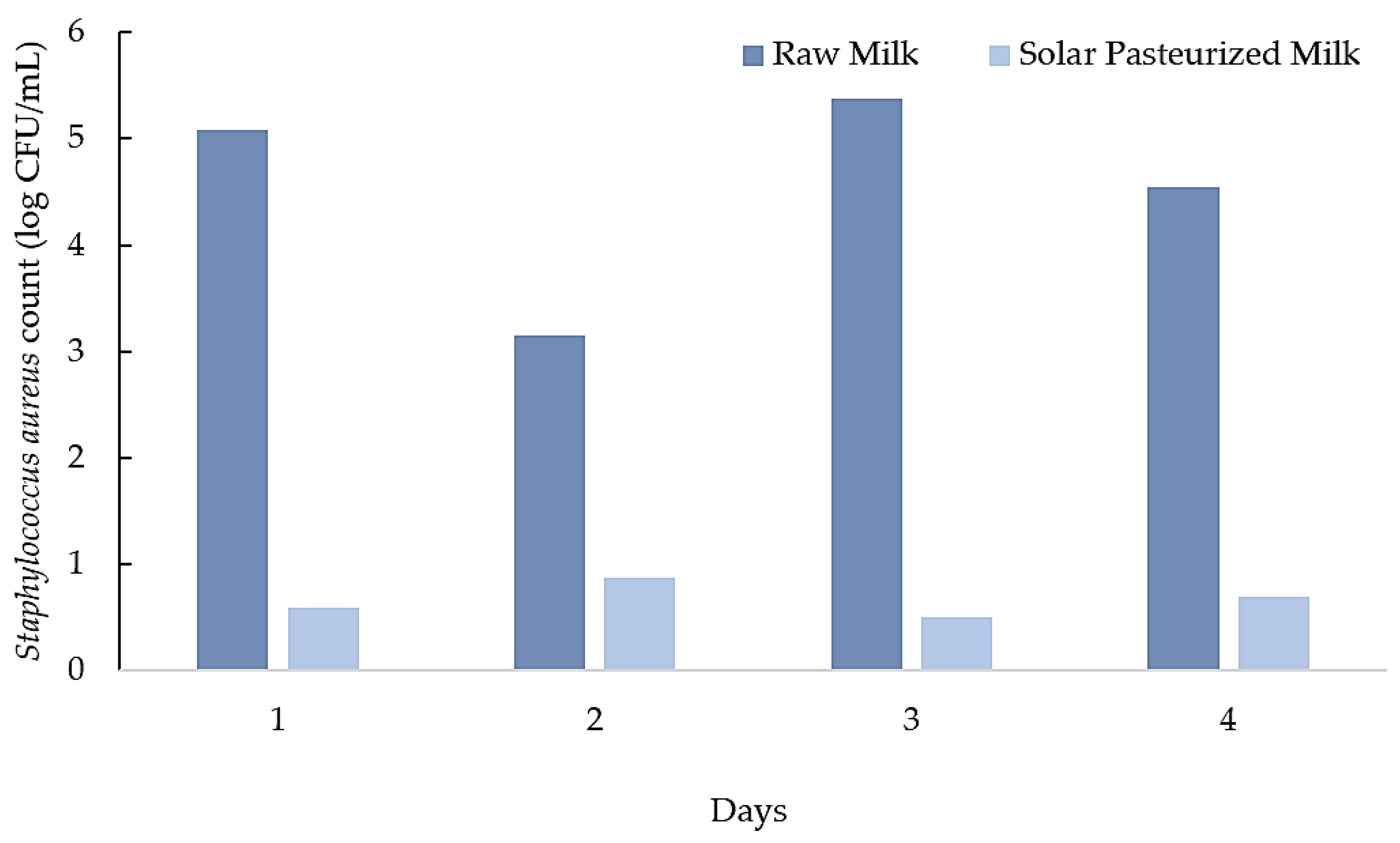

| Experimental days | Bacterial counts (log CFU/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bacteria count | Total coliforms | Staphylococcus aureus | ||||

| RM | SPM | RM | SPM | RM | SPM | |

| 1. | 6.92 | 1.64 | 2.7 | 0.85 | 5.08 | 0.6 |

| 2. | 7.35 | 2.05 | 2.08 | 0.5 | 3.15 | 0.87 |

| 3. | 6.63 | 2.5 | 3.17 | 1.74 | 5.37 | 0.51 |

| 4. | 6.37 | 1.83 | 2.95 | 0.65 | 4.55 | 0.7 |

| Mean ±S.D | 6.82 ±0.42 | 2.01 ±0.37 | 2.73 ±0.47 | 0.94 ±0.56 | 4.54 ±0.99 | 0.67 ±0.15 |

| 6.6x106 | 1.0x102 | 5.4x102 | 0.9x10 | 3.5x104 | 0.5x10 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).