Submitted:

10 May 2024

Posted:

13 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. hOSEC (human Organotypic Skin Explant Culture)

2.2. Inoculation of M. leprae

2.3. Histomorphology analysis of hOSEC

2.4. Molecular analysis of hOSEC

2.5. Viability using in vivo model

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

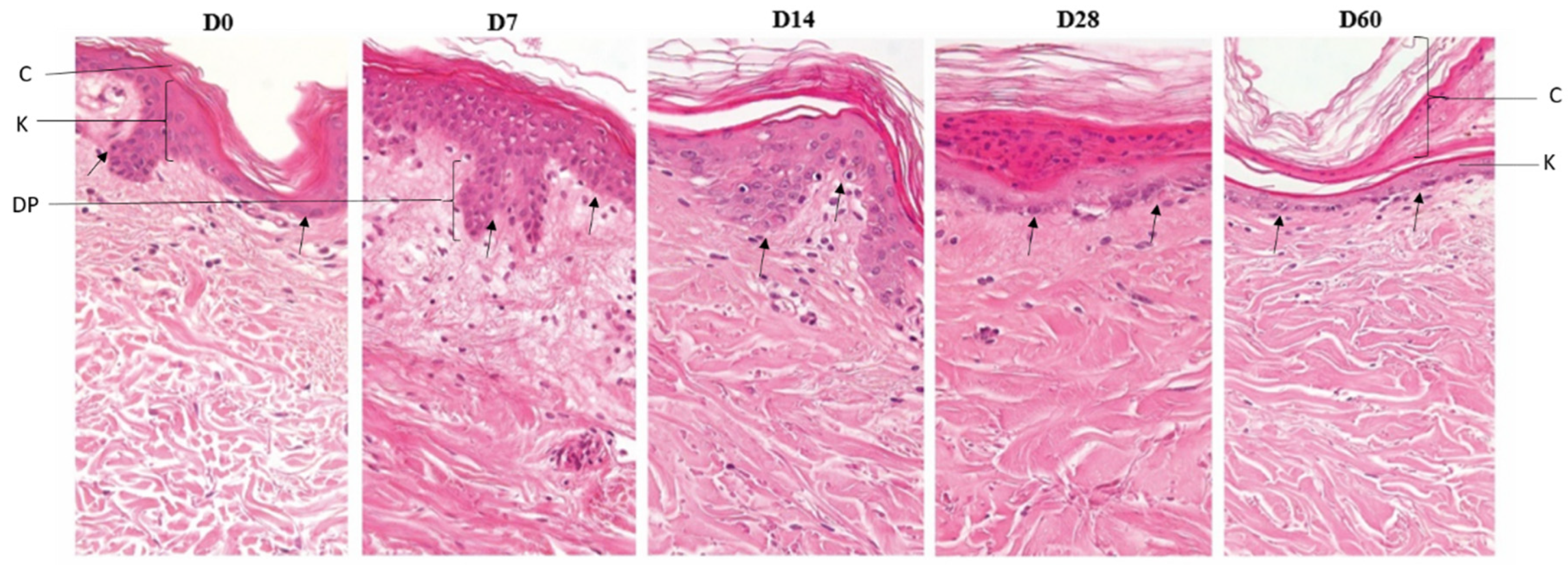

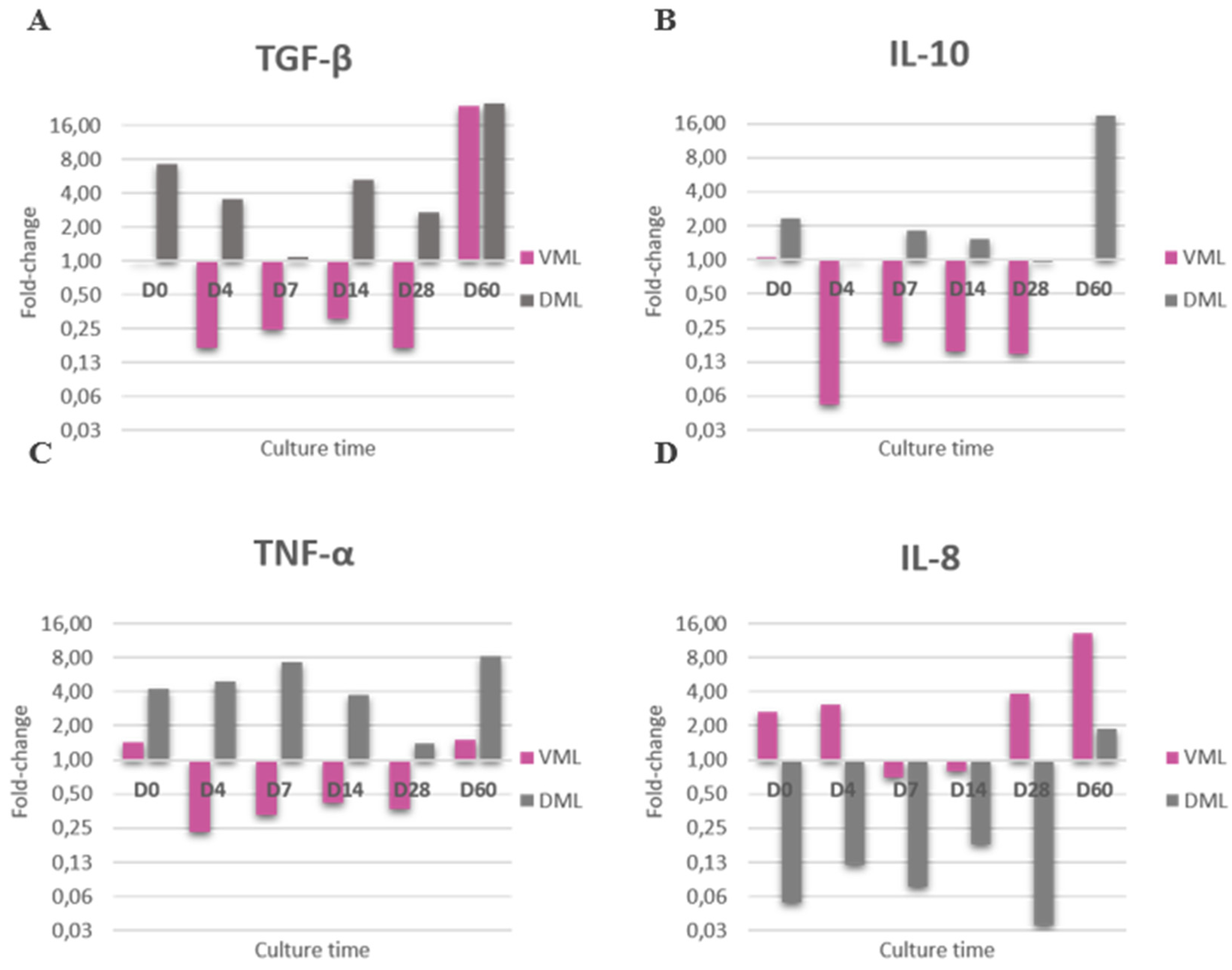

3.1. Characterization of donor skin and histomorphology

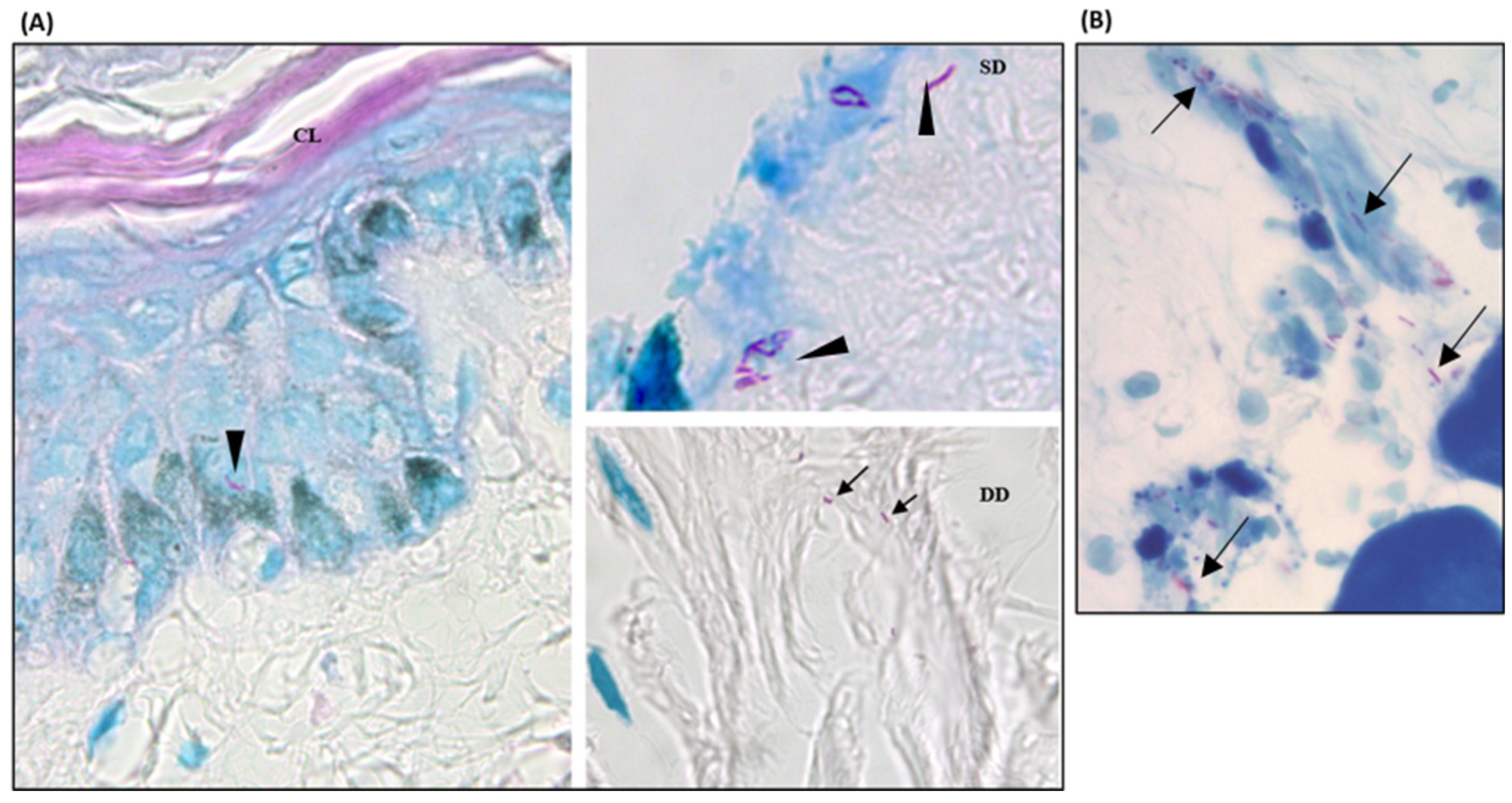

3.2. Viability of bacilli in hOSEC

3.3. Maintenance of viable and infective bacilli in hOSEC

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansen, G.H.A.; Looft, C. Leprosy: in its Clinical & Pathological Aspects. Reviews of books - Translated by Norman Walker, M. D. Pp. xi., 162. Bristol: John Wright & Co. 1895, 73- 74.

- Singh, A.K.; Bishai, W.R. Partners in Crime: Phenolic Glycolipids and Macrophages. Trends Mol Med. 2017, 23, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, S.; Rambukkana, A. Cell Biology of Intracellular Adaptation of Mycobacterium leprae in the Peripheral Nervous System. Microbiol Spectr. 2019, 7(4). [CrossRef]

- Global leprosy (Hansen disease) update, 2021: moving towards interruption of transmission. (2020). Weekly epidemiological record. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9837-409-430 (accessed on 08/03/2024).

- Ridley, D.S.; Jopling, W.H. Classification of leprosy according to immunity: a five-group system. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 1966, 34, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.C.; Lockwood, D.N. Leprosy now: epidemiology, progress, challenges, and research gaps. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011, 11, 464–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amako, K.; Lida, K.; Saito, M.; Ogura, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Yoshida, S. Non-exponential growth of Mycobacterium leprae Thai-53 strain cultured in vitro. Microbiol Immunol. 2016, 60, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaque, M. Attempts to Grow Mycobacterium leprae in a Medium with Palmitic Acid as the Substrate. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 1993, 61, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.S. Cultura do Mycobacterium leprae (Verificação dos Trabalhos de Vaudremer). Trabalho do Laboratório de Bacteriologia e Sorologia do Departamento de Prophylaxia da Lepra. 1937, Paulo. 133-140. Available online: http://hansen.bvs.ilsl.br/textoc/revistas/1937/PDF/v5n2/v5n2a01.pdf.

- Hudson, M.; Balls, M. European experimental animal use declines ever so slightly. ATLA, 2010, 38, 529–532. [CrossRef]

- Ranganatha, N.; Kuppast, A. review on alternatives to animal testing methods in drug development. Academic Sciences. 2012, 5, p. 28-32.

- Frade, M.A.C.; Andrade, T.A.M.; Aguiar, A.F.C.L.; Guedes, F.A.; Leite, M.N.; Passos, W.R.; et al. Prolonged viability of human organotypic skin explant in culture method (hOSEC). An Bras Dermatol. 2015, 90, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombone, A.P.F.; Pedrini, S.C.B.; Diório, S.M.; Belone, A.F.F.; Fachin, L.R.V.; Nascimento, D.C.; et al. Optimized Protocols for Mycobacterium leprae Strain Management: Frozen Stock Preservation and Maintenance in Athymic Nude Mice. J Vis Exp. 2014, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.S.; Naaz, F.; Katara, D.; Misba, L.; Kumar, D.; Dwivedi, D.K.; et al. Viability of Mycobacterium leprae in the environment and its role in leprosy dissemination. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016, 82, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, H.W.; Lee, B.C.; Choi, E.S.; Choi, I.J.; Lee, Y.S.; Goh, S.H. Identification of valid reference genes for gene expression studies of human stomach cancer by reverse transcription-qPCR. BMC Cancer. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, S.; Smith, K.A. Differentiation of T cell lymphokine gene expression: the in vitro acquisition of T cell memory. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 173, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negera, E.; Walker, S.L.; Bobosha, K.; Bekele, Y.; Endale, B.; Tarekegn, A.; et al. The effects of Prednisolone Treatment on cytokine expression in Patients with erythema nodosum leprosum reactions. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 1–15, DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00189. eCollection 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; et al. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.N.; Lahiri, R.; Pittman, T.L.; Scollard, D.; Truman, R.; Moraes, M.O.; et al. Molecular determination of Mycobacterium leprae viability by use of real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 2124–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, C.C. The experimental disease that follows the injection of human leprosy bacilli into foot-pads of mice. J Exp Med. 1960, 112: 445-454. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.V.P.M.; Deps, P.D.; Antunes, J.M.A.P. Armadillos and leprosy: from infection to biological model. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo. 2019, 61:e44. [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.B. Susceptibility and resistance in leprosy: Studies in the mouse model. Immunol Rev. 2021 301(1):157-174. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Maeda, Y.; Fukutomi, Y.; Makino, M.; An in vitro model of Mycobacterium leprae induced granuloma formation. BMC Infect Dis. 2013 20; 13:279. [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.N.; Viegas, J.S.R.; Praça, F.S.G.; Paula, N.A.; Ramalho L.N.Z.; Bentley, M.V.L.B.; Frade, M.A.C. Ex vivo model of human skin (hOSEC) for assessing the dermatokinetics of the anti-melanoma drug Dacarbazine. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2021 1:160:105769. [CrossRef]

- Danso, M.O.; Berkers, T.; Mieremet, A.; Hausil, F.; Bouwstra, J.A. An ex vivo human skin model for studying skin barrier repair. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 24, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Garcia, J.; Sebastian, A.; Alonso-Rasgado, T.; Bayat, A. Optimization of an ex vivo wound healing model in the adult human skin: Functional evaluation using photodynamic therapy. Wound Repair Regen. 2015, 23, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, J.; Green, H. Differentiation-related death of an established keratinocyte line in suspension culture. J. Cell. Physiol. 1978, 93,3, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.T.; Green, H. Differentiation of the epidermal keratinocyte in cell culture: formation of the cornified envelope. Cell. 1976, 9, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Hong, S.J.; Jia, S.; Zhao, Y.; Galiano, RD.; Mustoe, T.A. Application of a partial-thickness human ex vivo skin culture model in cutaneous wound healing study. Lab. Invest. 2012, 92, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, T.; Qu, J.; Cholewa-Waclaw, J.; Burr, K.; Raaum, R.; Rambukkana, A. Reprogramming Adult Schwann Cells to Stem Cell-like Cells by Leprosy Bacilli Promotes Dissemination of Infection. Cell. 2012, 152, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.S.; Montalvão, P.P.; Oliveira, I.T.; Wachholz, P.A. Neoplastic cells parasitized by Mycobacterium leprae: report of two cases of melanocytic nevus and one of basal cell carcinoma. Surgical and Experimental Pathology. 2019, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, R.; Randhawa, B.; Krahenbuhl, J. Application of a viability-staining method for Mycobacterium leprae derived from the athymic (nu/nu) mouse foot pad. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 54, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truman, R.W.; Krahenbuhl, J.L. Viable M. leprae as a research reagent. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. 2001, Dis. 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baque, R.H.; Gilliam, A.O.; Robles, L.D.; Jakubowski, W.; Slifko, T.R. A real-time RT-PCR method to detect viable Giardia lamblia cysts in environmental waters. Water Res. 2011, 45, 3175–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, R.A.; Guarines, K.M.; Montenegro, L.M.L.; Lira, L.A.S.; Falcão, J.; Melo, F.L.; et al. Assessment of messenger RNA (mRNA) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a marker of cure in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turankar, R.P.; Turankara, R.P.; Lavania, M.; Darlongd, J.; Saib, K.S.R.S.; Senguptaa, U.; et al. Survival of Mycobacterium leprae and association with Acanthamoeba from environmental samples in the inhabitant areas of active leprosy cases: A cross sectional study from endemic pockets of Purulia, West Bengal. Infect. Genet. Evol. 72, 199-204. [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.H.; Lenz, S.M.; Raya, N.A.; Lahiria R.; Adams L.B. Assessment of esxA, hsp18, and 16S transcript expression as a measure of Mycobacterium leprae viability: A comparison with the mouse footpad assay. Lepr Rev (2023) 94, 7–18. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.S.; Oliveira, D.A.S.; Santos, J.P.; Ribeiro, C.C.D.U.; Baêta, B.A.; Teixeira, R.C.; et al. Ticks as potential vectors of Mycobacterium leprae: Use of tick cell lines to culture the bacilli and generate transgenic strains. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 12. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lavania, M.; Katoch, K.; Katoch, V.M.; Gupta, A.K.; Chauhan, D.S.; Sharma, R.; et al. Detection of viable Mycobacterium leprae in soil samples: insights into possible sources of transmission of leprosy. Infect Genet Evol. 2008, 8, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.N.; Talhari, C.; Moraes, M.O.; Talhari, S. PCR-Based Techniques for Leprosy Diagnosis: From the Laboratory to the Clinic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetsuksiri, B.; Rudeeaneksin, J.; Supapkul, P.; Wachapong, S.; Mahotarn, K.; Brennan, P.J. A simpliced reverse transcriptase PCR for rapid detection of Mycobacterium leprae in skin specimens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006, 48, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I., Ahuja, M., Lavania, M., Pathak, V.K., Turankar, R.P., Singh, V., et al. Efficacy of fixed duration multidrug therapy for the treatment of multibacillary leprosy: A prospective observational study from Northern India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.S.; Fontes, A.N.B.; Lopes, M.Q.P.; Suffys, P.N.; Moraes, M.O.; Lara, F.A. Heterogeneous persistence of Mycobacterium leprae in oral and nasal mucosa of multibacillary patients during multidrug therapy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, 2022, 117. [CrossRef]

- Ishaque, M. Growth of Mycobacterium leprae under low oxygen tension. Microbios. 1990, 64, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wheat, W.H.; Casali, A.L.; Thomas, V.; Spencer, J.S.; Lahiri, R.; Williams, D.L.; et al. Long-term Survival and Virulence of Mycobacterium leprae in Amoebal Cysts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamayooran, G.; Pena, M.; Sharma, R.; Truman, R.W. The armadillo as an animal model and reservoir host for Mycobacterium leprae. Clin. Dermatol. 2015, 33, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchheimer, W.F.; Storrs, E.E. Attempts to establish the armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus Linn.) as a model for the study of leprosy. I. Report of lepromatoid leprosy in an experimentally infected armadillo. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 1971, 39, 693–702.

- Balbino, C.A.; Pereira, L.M.; Curi, R. Mecanismos envolvidos na cicatrização: uma revisão. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Farmacêuticas. 2005, 41, 27-51. DOI.org/10.1590/S1516-93322005000100004.

- Barrientos, S.; Stojadinovic, O.; Golinko, M.S.; Brem, H.; Tomic-Canic, M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008, 16, 585–601. [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.A.; Coker, R. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998, 30, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gailit, J.; Welch, M.P.; Clark, R.A.F. TGF-beta 1 stimulates expression of keratinocyte integrins during re-epithelialization of cutaneous wounds. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1994, 103, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennekampff, H.O.; Hansbrough, J.F.; Kiessig, V.; Doré, C.; Sticherling, M.; Schröder, J.M. Bioactive interleukin-8 is expressed in wounds and enchances wound healing. J. Surg. Res. 2000, 93, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Ohshima, T.; Konto, T. Regulatory role of endogenous interleukin-10 in cutaneous inflammatory response of murine wound healing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commum. 1999, 256, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Ramakrishnan, L. The Role of the Granuloma in Expansion and Dissemination of Early Tuberculous Infection. Cell. 2009, 136, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktariana, D.; Saleh, I.; Hafy Z.; Liberty, I.A.; Salim E.M.; Legiran L. The Role of Interleukin-10 in Leprosy: A Review. Indian Journal Leprosy. 2022, 94: 321-334.

- Barnes, P.F.; Chatterjee, D.; Brennan, P.J.; Rea, T.H.; Modlin, R.L. Tumor Necrosis Factor Production in Patients with Leprosy. Infection and immunity. 1992, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushima, K.; Yang, D.; Oppenheim, J.J. Interleukin-8: An evolving chemokine. Cytokine. 2022, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, B.J.D.; Mendes, M.A.; Silva, G.M.S.; Sammarco-Rosa, P.; Moraes M.O.; Jardim, M,R.; et. al Gene Expression Profile of Mycobacterium leprae Contribution in the Pathology of Leprosy Neuropathy. Front. Med. 2022, 9:861586. [CrossRef]

| Target | Sequence | Cycling | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | 5' TCGAACGGAAAGGTCTCTAAAAAATC 3’ 5' CCTGCACCGCAAAAAGCTTTCC 3' |

2 min at 95°C; 45 cycles of 2 min at 94°C, 2 min at 60°C and 3 min at 72°C; and 10 min at 72°C | [14] |

| 18S rRNA | 5' GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT 3' 5' CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG 3' |

2 min at 95°C; 38 cycles of 94°C for 2 min, 60°C for 2 min and 72°C for 3 min; and 72°C for 10 min. | [15] |

| IL-1β | 5’ CTTCATCTTTGAAGAAGAACCTATCTTCTT 3’ 5’ AATTTTTGGGATCTACACTCTCCAGCTGTA 3’ |

95°C for 2 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 62°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. | [16] |

| TGF-β | 5' ACATCAACGCAGGGTTCACT 3' 5' GAAGTTGGCATGGTAGCCC 3' |

95°C for 2 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. | [17] |

| TNF-α | 5’ TGGCTTTCACATACTGCTGGTA 3’ 5′ GCTGGTTATCTCTCAG CTCCA 3' |

95°C for 2 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. | [17] |

| IFN-γ | 5’ GGCTTTTCAGCTCTGCATCG 3’ 5’ TCTGTCACTCTCCTCTTTCCA 3’ |

95°C for 2 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. | [17] |

| IL-8 | 5’ ACCGGAAGGAACCATCTCAC 3’ 5’ AAACTGCACCTTCACACAGAG 3’ |

95°C for 2 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. | [17] |

| IL-10 | 5’ TGAGAACCAAGACCCAGACA 3’ 5’ TCATGGCTTTGTAGATGCCT 3’ |

95°C for 2 min and 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec, 60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 20 sec. | [17] |

| Day | Skin 1 | Skin 2 | Skin 3 | Skin 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0 | 28,05 | 34,73 | 30,29 | UR |

| 37,32 | 38,30 | 33,51 | UR | |

| ND | 35,34 | 34,95 | ND | |

| D4 | 28,66 | 32,66 | 28,74 | 29,21 |

| 28,45 | 31,70 | 29,84 | 28,17 | |

| 27,70 | 31,08 | 28,01 | 28,03 | |

| D7 | 29,21 | 30,75 | 33,35 | 28,62 |

| 29,77 | 30,27 | 33,19 | 29,16 | |

| 29,70 | 33,21 | 29,43 | 31,28 | |

| D14 | 29,71 | 29,80 | 29,80 | 29,12 |

| 29,01 | 29,19 | 28,92 | 30,10 | |

| 30,00 | 30,54 | 28,79 | 31,37 | |

| D28 | 31,03 | 30,65 | 28,37 | 33,13 |

| 31,27 | 32,37 | 31,61 | 29,31 | |

| 31,43 | 33,82 | 33,70 | ND | |

| D60 | 31,30 | UR | 29,81 | 30,61 |

| 37,17 | UR | 30,22 | ND | |

| 39,71 | UR | 32,90 | UR |

| Inoculum (nº of animals) | ZN (+) (%) | FF (+) (%) | RT-PCR (+) (%) | At least one microscopy analysis (+ ) (%) | ZN and RT-PCR (+) (%) | FF and RT-PCR (+) (%) | At least one microscopy analysis (+) and RT-PCR (+) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D28 (10) | 6 (60,0) | 5 (50,0) | 6 (60,0) | 8 (80) | 4 (40,0) | 4 (40,0) | 6 (60,0) |

| D60 (7) | 3 (42,9) | 0 (0,0) | 3 (42,9) | 3 (42,9) | 1 (14,3) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (14,3) |

| Total (17) | 9 (52,9) | 5 (50,0) | 9 (52,9) | 11 (64,7) | 5 (29,4) | 4 (40,0) | 7 (41,2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).