Submitted:

10 May 2024

Posted:

13 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

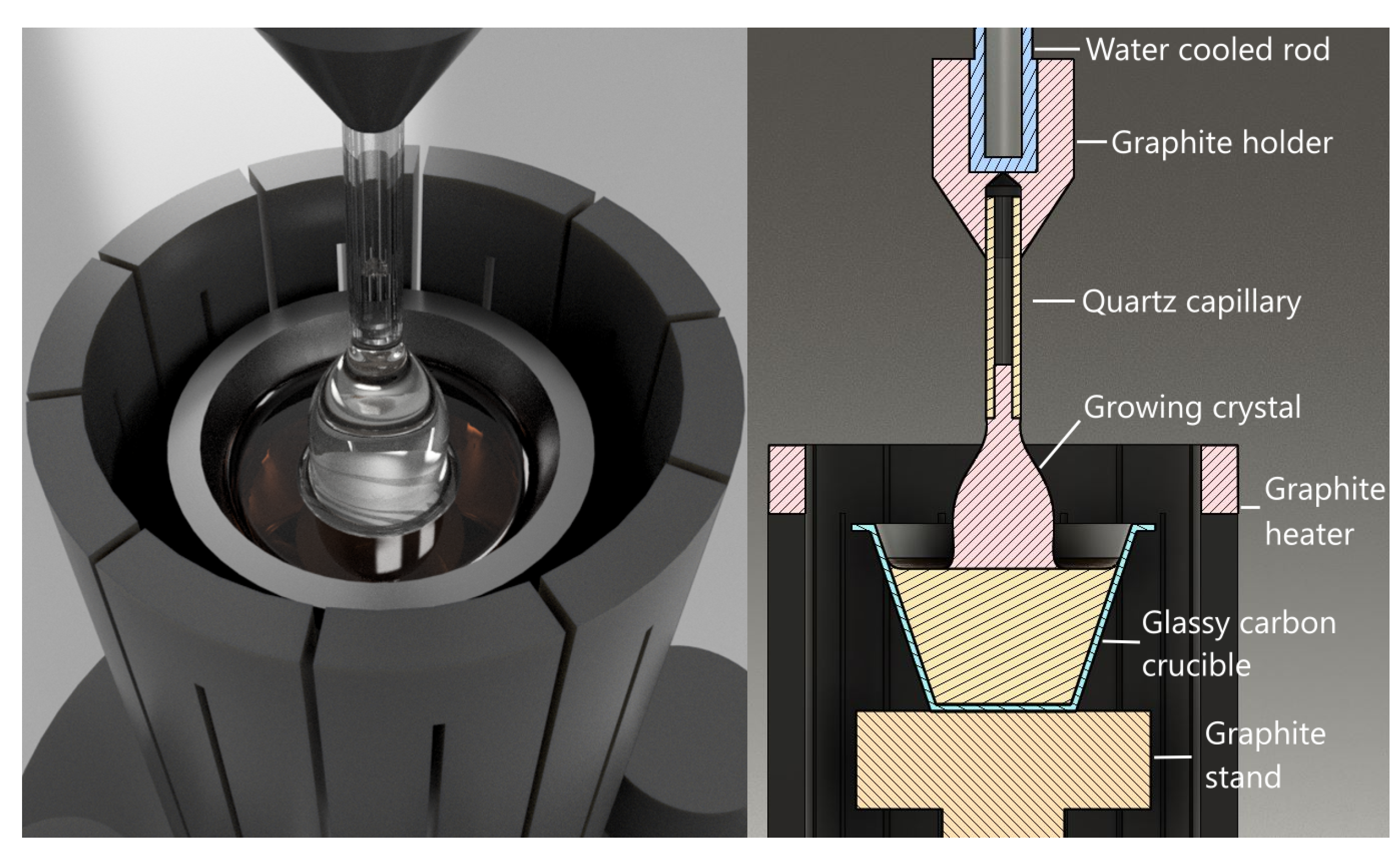

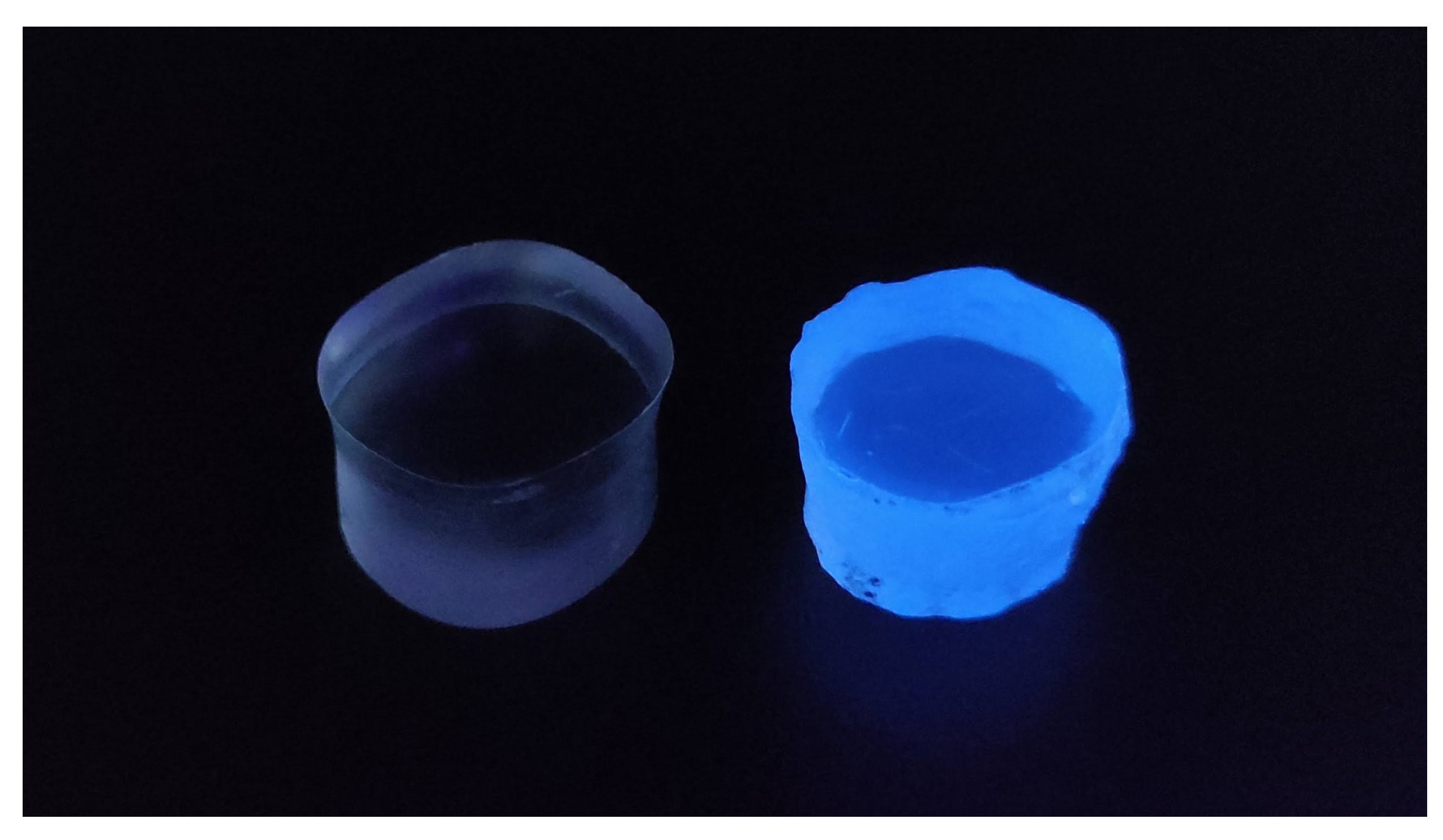

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Calculations

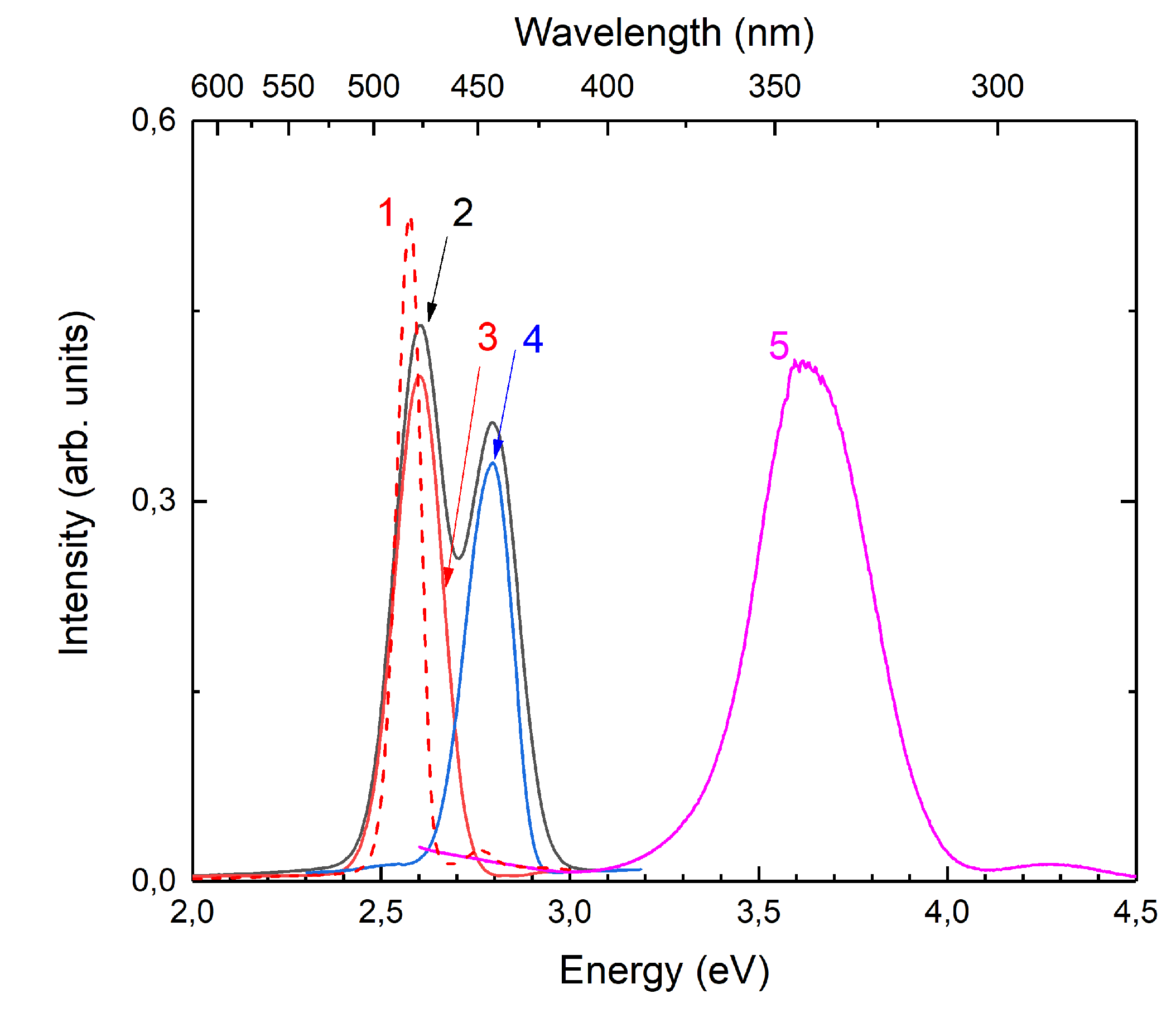

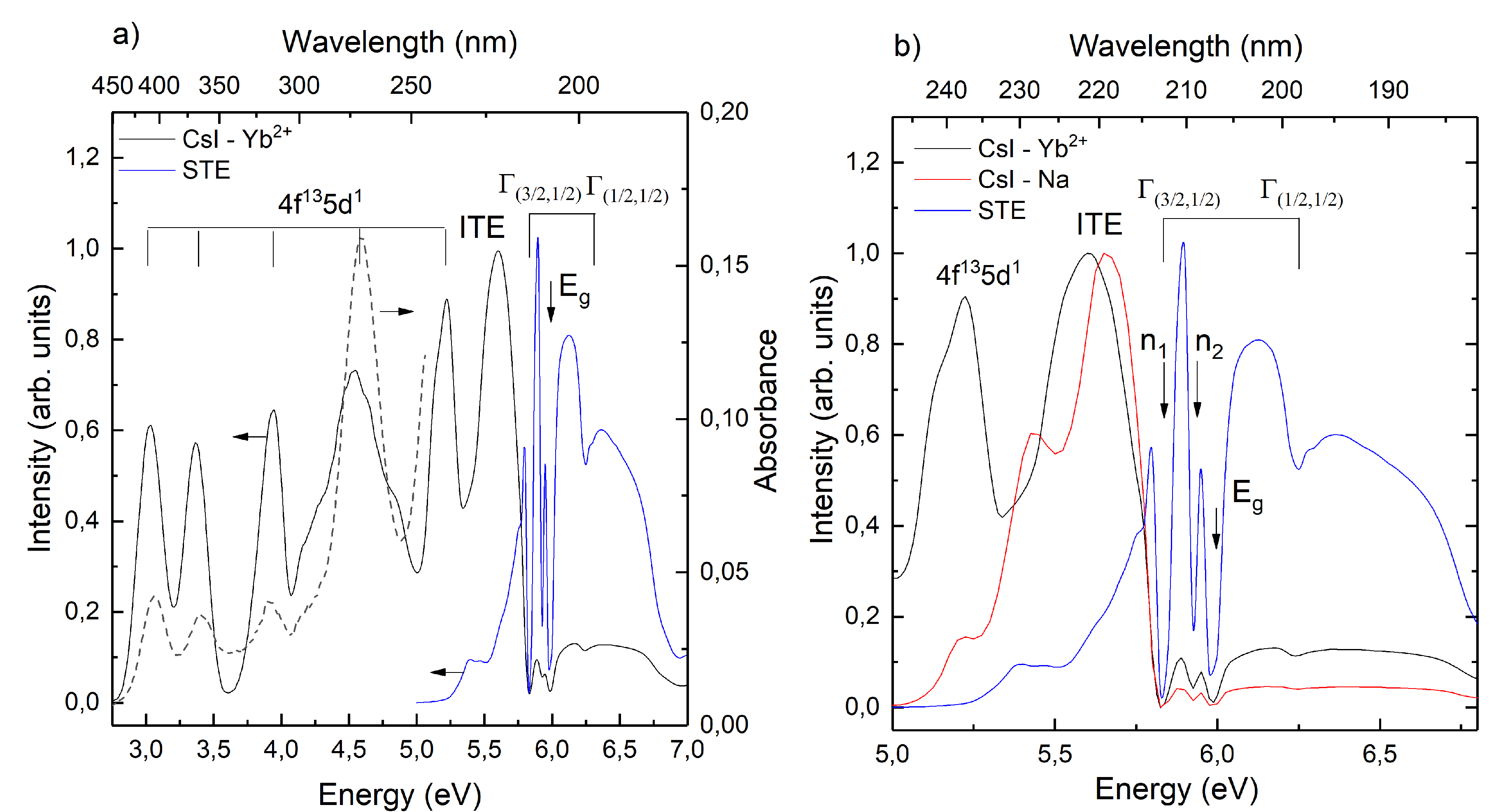

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VUV | Vacuum ultraviolet |

| VASP | The Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package |

| SiPM | Silicon photomultiplier |

| STE | Self-trapped exciton |

References

- Van Sciver, W.; Hofstadter, R. Scintillations in Thallium-Activated CaI2 and CsI. Physical Review 1951, 84, 1062–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, D.W.; Beron, B.L.; Yenicay, G.; Zulliger, H.R. The Fluorescent Response of NaI(Tl), CsI(Tl), CsI(Na) and CaF2(Eu) to X-Rays and Low Energy Gamma Rays. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 1967, 14, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, V.; Trefilova, L.; Meleshko, A.; Alekseev, V.; Kosinov, N. Charge transfer processes in CsI:Tl using near-UV light. Journal of Luminescence 2014, 155, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanaka, K.; Kayal, A.H.; Mezger, A.C.; Rossel, J. Self-Trapped Exciton Luminescence after Tunnelling of Vk and Nao Centers in CsI:Na Crystals. physica status solidi (b) 1981, 108, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, V.; Trefilova, L.; Meleshko, A.; Ganja, Y. Short-living absorption and emission of CsI(Na). Journal of Luminescence 2011, 131, 2579–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savel’ev, V.; Avdonin, V.; Dugarova, L.; Nedashkovskij, A.; Plachenov, B. Aggregation of Eu2+centers in alkali halide crystals doped with Eu. Fizika Tverdogo Tela 1974, 16, 1090–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev, V.; Trefilova, L.; Karnaukhova, A.; Ovcharenko, N. Energy transfer mechanism in CsI:Eu crystal. Journal of Luminescence 2014, 148, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gektin, A.; Shiran, N.; Belsky, A.; Vasyukov, S. Luminescence properties of CsI:Eu crystals. Optical Materials 2012, 34, 2017–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, Y.; Kurosawa, S.; Yokota, Y.; Hayasaka, S.; Kamada, K.; Yoshino, M.; Yamaji, A.; Chani, V.; Ohashi, Y.; Sakuragi, S.; Yoshikawa, A. Growth and Scintillation Properties of Two-Inch-Diameter SrI2(Eu) Single Crystals. Crystal Growth & Design 2018, 18, 3747–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galenin, E.; Sidletskiy, O.; Dujardin, C.; Gektin, A. Growth and Characterization of SrI2:Eu Crystals Fabricated by the Czochralski Method. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2018, 65, 2174–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerechuk, A.; Galenin, E.; Nesterkina, V.; Sidletskiy, O.; Dujardin, C. Growth and scintillation performances of SrI2:Eu with low activator concentration. Journal of Crystal Growth 2019, 521, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loef, E.V.D.; Dorenbos, P.; van Eijk, C.W.E.; Krämer, K.; Güdel, H.U. High-energy-resolution scintillator: Ce3+ activated LaBr3. Applied Physics Letters 2001, 79, 1573–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekhin, M.S.; de Haas, J.T.M.; Khodyuk, I.V.; Krämer, K.W.; Menge, P.R.; Ouspenski, V.; Dorenbos, P. Improvement of γ-ray energy resolution of LaBr3:Ce3+ scintillation detectors by Sr2+ and Ca2+ co-doping. Applied Physics Letters 2013, 102, 161915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourret-Courchesne, E.D.; Bizarri, G.; Hanrahan, S.M.; Gundiah, G.; Yan, Z.; Derenzo, S.E. BaBrI:Eu2+, a new bright scintillator. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2010, 613, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendrik, R.; Shalaev, A.A.; Myasnikova, A.S.; Bogdanov, A.; Kaneva, E.; Rusakov, A.; Vasilkovskyi, A. Optical and structural properties of Eu2+ doped BaBrI and BaClI crystals. Journal of Luminescence 2017, 192, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaev, A.A.; Shendrik, R.; Myasnikova, A.S.; Bogdanov, A.; Rusakov, A.; Vasilkovskyi, A. Luminescence of BaBrI and SrBrI single crystals doped with Eu2+. Optical Materials 2018, 79, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalapska, T.; Moretti, F.; Bourret, E.; Bizarri, G. Effect of Au codoping on the scintillation properties of BaBrCl:Eu single crystals. Journal of Luminescence 2018, 202, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravleva, M.; Stand, L.; Wei, H.; Hobbs, C.; Boatner, L.A.; Ramey, J.O.; Shah, K.; Burger, A.; Rowe, E.; Bhattacharya, P.; Tupitsyn, E.; Melcher, C.L. Hygroscopicity evaluation of halide scintillators. 2013 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (2013 NSS/MIC), 2013, pp. 1–5. ISSN 1082-3654. [CrossRef]

- Mianowska, Z.; Moszynski, M.; Brylew, K.; Chabera, M.; Dziedzic, A.; Gektin, A.V.; Krakowski, T.; Mianowski, S.; Syntfeld-Każuch, A.; Szczesniak, T.; Zezulinski, K. The light response of CsI:Tl crystal after interaction with gamma radiation study using analysis of single scintillation pulses and digital oscilloscope readout. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2022, 1031, 166600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qi, H.; Liu, F.; Meng, H.; Cai, J.; Xu, S.; Jing, S.; Hong, F.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, R.; Lai, J.; Xu, F.; Wang, L. Approaching the Theoretical Light Yield Limit in CsI (Tl) Scintillator Single Crystals by a Low-Temperature Solution Method. Crystal Growth & Design 2020, 20, 3474–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Liu, B.; Xiang, X.; Chen, L.; Xu, M.; Song, X.; Ruan, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y. Enhanced light output of CsI(Na) scintillators by photonic crystals. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2020, 969, 164007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodiya, D.S.; Singh, S.G.; Chandrakumar, K.R.S.; Patra, G.D.; Ghosh, M.; Pitale, S.; Sen, S. Optimizing the Scintillation Kinetics of CsI Scintillator Single Crystals by Divalent Cation Doping: Insights from Electronic Structure Analysis and Luminescence Studies. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2024, 128, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Chernyak, D.; Liu, J. Light yield of cold undoped CsI crystal down to 13 keV and the application of such crystals in neutrino detection. The European Physical Journal C 2020, 80, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailik, V.B.; Kapustyanyk, V.; Tsybulskyi, V.; Rudyk, V.; Kraus, H. Luminescence and scintillation properties of CsI: A potential cryogenic scintillator. physica status solidi (b) 2015, 252, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.I.; Chernov, S.A.; Trinkler, L.E. Time-resolved luminescence of CsI:Tl crystals excited by pulsed electron beam. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 1997, 122, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.T.; Grim, J.Q.; Li, Q.; Ucer, K.B.; Moses, W.W. Excitation density, diffusion-drift, and proportionality in scintillators. physica status solidi (b) 2011, 248, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, M.M.; Costa, F.E.; Shimizu, S.; Kubota, S. Radiation damage of CsI(Tl) scintillators: blocking of energy transfer process of Vk centers to Tl+ activators. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2002, 486, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suta, M.; Wickleder, C. Spin Crossover of Yb2+ in CsCaX2 and CsSrX2 (X = Cl, Br, I) – A Guideline to Novel Halide-Based Scintillators. Advanced Functional Materials 2017, 27, 1602783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suta, M.; Wickleder, C. Synthesis, spectroscopic properties and applications of divalent lanthanides apart from Eu2+. Journal of Luminescence 2019, 210, 210–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoi, K.; Arai, M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Nakauchi, D.; Koshimizu, M.; Yanagida, T.; Asai, K. Photoluminescence and scintillation properties of Yb2+-doped ACaCl3 (A = Cs, Rb, K) crystals. Journal of Luminescence 2020, 227, 117521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolszczak, W.; Krämer, K.W.; Dorenbos, P. Engineering near-infrared emitting scintillators with efficient Eu2+ → Sm2+ energy transfer. Journal of Luminescence 2020, 222, 117101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaev, A.A.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Rusakov, A.I.; Sokol’nikova, Y.V.; Myasnikova, A.S. Growth and Study of Scintillation Properties of BaBrI Crystals Activated by Samarium Ions. Physics of the Solid State 2019, 61, 2403–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaev, A.; Shendrik, R.; Rusakov, A.; Bogdanov, A.; Pankratov, V.; Chernenko, K.; Myasnikova, A. Luminescence of divalent lanthanide doped BaBrI single crystal under synchrotron radiation excitations. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2020, 467, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, T.; Witzke, H.; McClure, D.S. The 4f14→4f135d transition of Yb2+ ion in NaCl crystals. Journal of Luminescence 1981, 24-25, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O. , J.R. Doubly-valent rare-earth ions in halide crystals. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 1991, 52, 101–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Okada, G.; Sekine, D.; Yanagida, T.; Koshimizu, M.; Kawamoto, H.; Asai, K. Radiation induced change in the optical properties of NaCl:Yb crystal. Radiation Measurements 2020, 133, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ren, G.; Nikl, M.; Chen, X.; Ding, D.; Li, H.; Pan, S.; Yang, F. CsI:Tl+,Yb2+: ultra-high light yield scintillator with reduced afterglow. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 3312–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, R.H.; Kappers, L.A.; Hamilton, D.S.; Brecher, C.; Ovechkina, E.E.; Miller, S.R.; Nagarkar, V.V. Multiple thermoluminescence glow peaks and afterglow suppression in CsI:Tl co-doped with Eu2+ or Yb2+. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2015, 80, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, V.; Kozlova, A.P.; Buzanov, O.A.; Chernenko, K.; Shendrik, R.; Šarakovskis, A.; Pankratov, V. Time-resolved luminescence and excitation spectroscopy of co-doped Gd3Ga3Al2O12 scintillating crystals. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 20388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuomela, A.; Zhang, M.; Huttula, M.; Sakirzanovas, S.; Kareiva, A.; Popov, A.I.; Kozlova, A.P.; Aravindh, S.A.; Cao, W.; Pankratov, V. Luminescence and vacuum ultraviolet excitation spectroscopy of samarium doped SrB4O7. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 826, 154205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, A.P.; Kasimova, V.M.; Buzanov, O.A.; Chernenko, K.; Klementiev, K.; Pankratov, V. Luminescence and vacuum ultraviolet excitation spectroscopy of cerium doped Gd3Ga3Al2O12 single crystalline scintillators under synchrotron radiation excitations. Results in Physics 2020, 16, 103002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernenko, K.; Kivimäki, A.; Pärna, R.; Wang, W.; Sankari, R.; Leandersson, M.; Tarawneh, H.; Pankratov, V.; Kook, M.; Kukk, E.; Reisberg, L.; Urpelainen, S.; Käämbre, T.; Siewert, F.; Gwalt, G.; Sokolov, A.; Lemke, S.; Alimov, S.; Knedel, J.; Kutz, O.; Seliger, T.; Valden, M.; Hirsimäki, M.; Kirm, M.; Huttula, M. Performance and characterization of the FinEstBeAMS beamline at the MAX IV Laboratory. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 2021, 28, 1620–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärna, R.; Sankari, R.; Kukk, E.; Nõmmiste, E.; Valden, M.; Lastusaari, M.; Kooser, K.; Kokko, K.; Hirsimäki, M.; Urpelainen, S.; Turunen, P.; Kivimäki, A.; Pankratov, V.; Reisberg, L.; Hennies, F.; Tarawneh, H.; Nyholm, R.; Huttula, M. FinEstBeaMS – A wide-range Finnish-Estonian Beamline for Materials Science at the 1.5 GeV storage ring at the MAX IV Laboratory. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2017, 859, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratov, V.; Kotlov, A. Luminescence spectroscopy under synchrotron radiation: From SUPERLUMI to FINESTLUMI. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2020, 474, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratov, V.; Pärna, R.; Kirm, M.; Nagirnyi, V.; Nõmmiste, E.; Omelkov, S.; Vielhauer, S.; Chernenko, K.; Reisberg, L.; Turunen, P.; Kivimäki, A.; Kukk, E.; Valden, M.; Huttula, M. Progress in development of a new luminescence setup at the FinEstBeAMS beamline of the MAX IV laboratory. Radiation Measurements 2019, 121, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendrik, R.; Kaneva, E.; Pankratova, V.; Pankrushina, E.; Radomskaya, T.; Gavrilenko, V.; Loginova, P.; Pankratov, V. Intrinsic luminescence and radiation defects in scapolite. Chemical Physics Letters 2024, 838, 141081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initiomolecular dynamics for liquid metals. Physical Review B 1993, 47, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HPC-cluster “Akademik, V.M. Matrosov”. Irkutsk Supercomputer Center of SB RAS.

- Inorganic Crystal Structure Database. FIZ Karlsruhe – Leibniz Institute for Information Infrastructure.

- Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2011, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, B.P.; Altarawy, D.; Didier, B.; Gibson, T.D.; Windus, T.L. New Basis Set Exchange: An Open, Up-to-Date Resource for the Molecular Sciences Community. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2019, 59, 4814–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suta, M.; Urland, W.; Daul, C.; Wickleder, C. Photoluminescence properties of Yb2+ ions doped in the perovskites CsCaX3 and CsSrX3 (X = Cl, Br, and I) – a comparative study. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2016, 18, 13196–13208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, T.; McClure, D.S.; Wong, W.C. Luminescence kinetics of Yb2+ in NaCl. Physical Review B 1993, 48, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, S.W.; Smith, M.J.A. 4f14 to 4f135d optical transitions of divalent ytterbium in the potassium and sodium halides. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics 1985, 18, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, B.W. Spectra of Doubly and Triply Ionized Ytterbium, Yb III and Yb IV. JOSA 1965, 55, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.K.; Tanner, P.A. Simulation of 4f–5d transitions of Yb2+ in potassium and sodium halides. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2008, 20, 215228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, J.T.; Wilkins, M.H.F.; Oliphant, M.L.E. Phosphorescence and electron traps - I. The study of trap distributions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1997, 184, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelletti, R. Thermally Stimulated Depolarization Studies of Ionic Solids. In Defects in Solids: Modern Techniques; Chadwick, A.V., Terenzi, M., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1986; pp. 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poźniak, J.; Poźniak, J.K. Thermally Stimulated Depolarization Currents in Me2+-Doped NaCl-Type Alkali Halide Crystals. physica status solidi (b) 1997, 200, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Shirai, M.; Kan’no, K.i. Time-Resolved Spectroscopic Study on the Type I Self-Trapped Excitons in Alkali Halide Crystals: II. Excitation Spectra and Relaxation Processes. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 1995, 64, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onodera, Y. Energy Bands in CsI. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 1968, 25, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Bizarri, G.A.; Yang, K.; Mayhugh, M.R.; Menge, P.R.; Williams, R.T. Coupled rate and transport equations modeling proportionality of light yield in high-energy electron tracks: CsI at 295 K and 100 K; CsI:Tl at 295 K. Physical Review B 2015, 92, 115207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.T.; Ucer, K.B.; Grim, J.Q.; Lipke, K.C.; Trefilova, L.M.; Moses, W.W. Picosecond Studies of Transient Absorption Induced by BandGap Excitation of CsI and CsI:Tl at Room Temperature. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2010, 57, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendrik, R.Y.; Kovalev, I.I.; Rusakov, A.I.; Sokol’nikova, Y.V.; Shalaev, A.A. Luminescence of BaBrI Crystals Doped with Ce3+ Ions. Physics of the Solid State 2019, 61, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Gridin, S.; Ucer, K.B.; Williams, R.T.; Del Ben, M.; Canning, A.; Moretti, F.; Bourret, E. Picosecond Absorption Spectroscopy of Excited States in BaBrCl with and without Eu Dopant and Au Codopant. Physical Review Applied 2019, 12, 014035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).