Submitted:

09 May 2024

Posted:

12 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

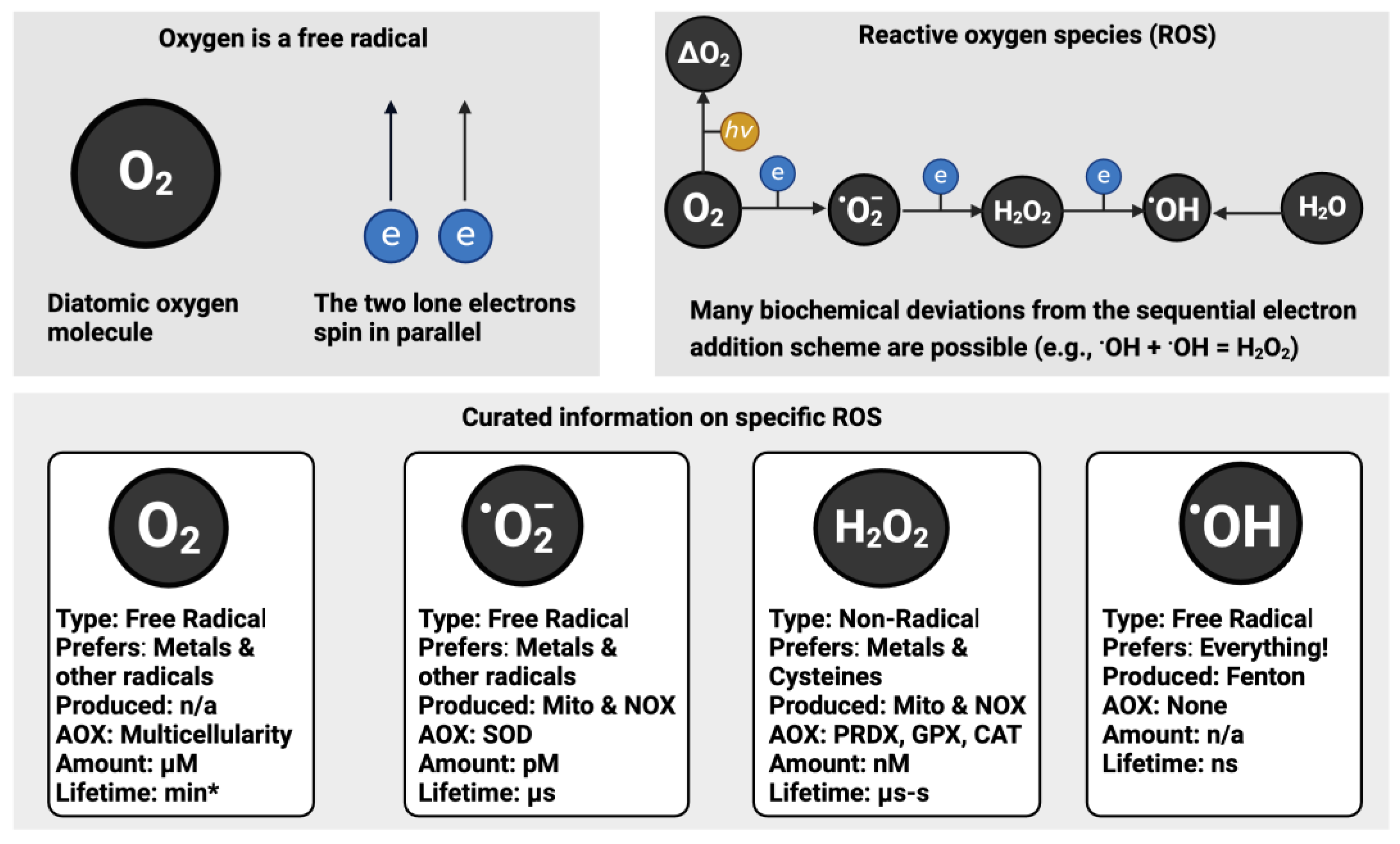

1.1. Oxygen

1.2. ROS

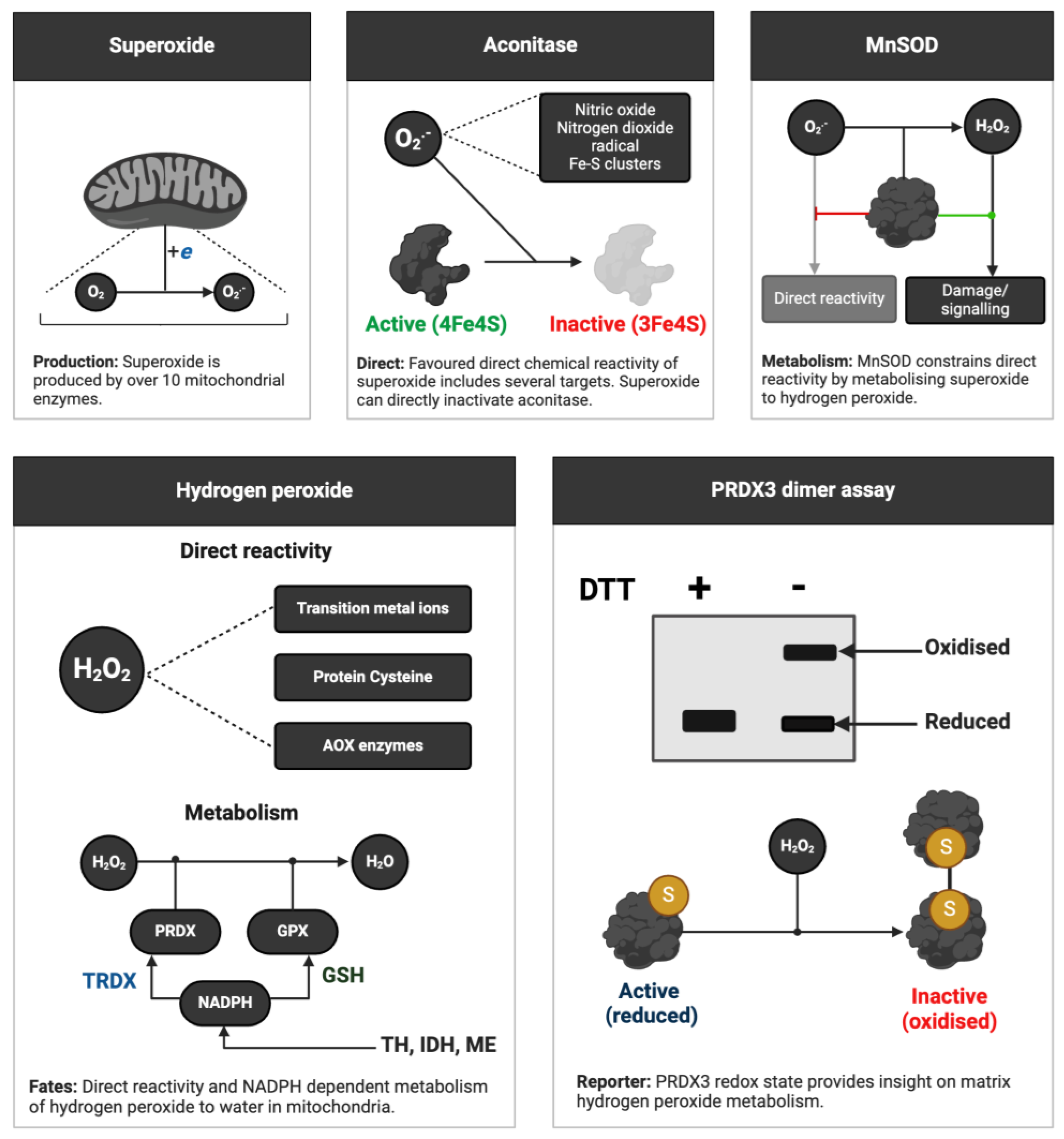

- Superoxide is not necessarily super. The “superoxide” moniker originated from the odd stoichiometry of a chemical reaction in 1934 (Neuman, 1934). It had nothing to do with any special “super” biochemical reactivity as an oxidant (Sawyer and Valentine, 1981). Sawyer and Valentine commented that the probability of superoxide oxidising a molecule to yield the peroxide dianion is nil. Moreover, McCord and Fridovich discovered superoxide dismutase (SOD) by observing that superoxide reduced ferric cytochrome c (McCord and Fridovich, 1969, 1968).

- Each ROS is biochemically unique (Dickinson and Chang, 2011; Gutteridge, 2015; Winterbourn, 2008). Superoxide appreciably reacts with a small number of targets, such as tryptophan free radicals (Carroll et al., 2018). Conversely, the ferocious hydroxyl radical, rapidly reacts with virtually every organic molecule at a diffusion-controlled rate (Halliwell, 2007).

- There is no set percentage rate of superoxide production from consumed oxygen (Boveris and Chance, 1973; Chance et al., 1979). As studies comparing rest to exercise attest (Goncalves et al., 2015), the dynamic variable rate of mitochondrial superoxide production is context-dependent (Cobley, 2018; Sidlauskaite et al., 2018).

-

To quote Sies and Jones “ROS is a term, not a molecule” (Sies and Jones, 2020).Equation 1: Oxygen + electron → superoxide

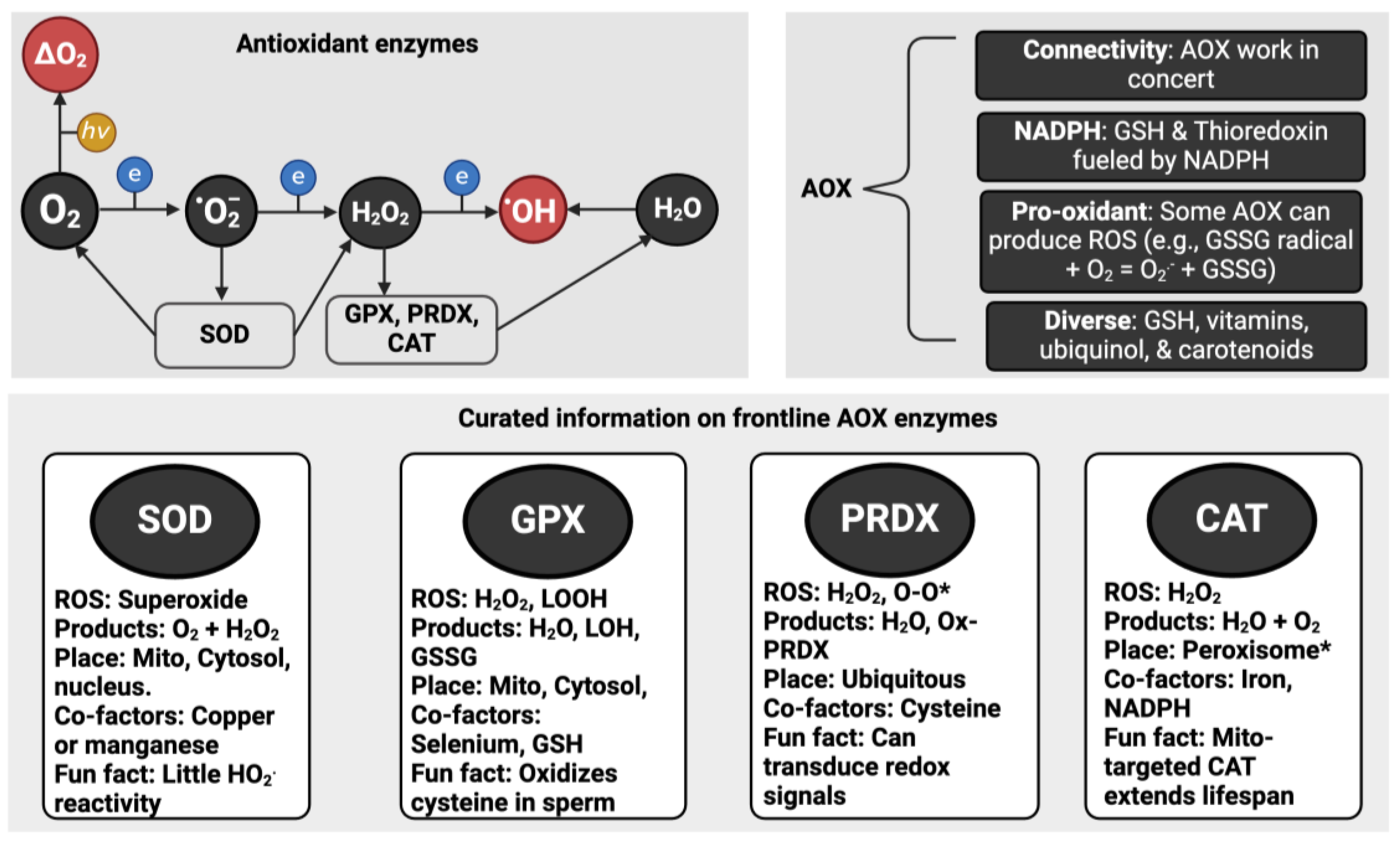

1.3. Antioxidants

“any substance that delays, prevents or removes oxidative damage to a target molecule” OR “a substance that reacts with an oxidant to regulate its reactions with other targets, thus influencing redox-dependent biological signalling pathways and/or oxidative damage”

- There is no one “best” antioxidant. Just like ROS, they are all different (see Figure 2).

- A few “frontline” enzymes like SOD do most of the redox “heavy-lifting”. Ordinarily, SOD isoforms consume most of the superoxide produced in a cell (Imlay, 2008). So, only picomoles remain for other molecules, such as vitamin C, to “scavenge”. For example, 3.01 x 1018 (5 µM) superoxide molecules can be produced per second in Escherichia coli, but SOD limits [superoxide] by 4-logs to 6.0 x 1014 molecules corresponding to 0.0009 µM or 900 picomoles (Imlay, 2013).

- An antioxidant is context-dependent. SOD generates hydrogen peroxide and oxygen. So, it is an antioxidant in concert with other enzymes (Winterbourn, 1993). Further, when mis-metalled the mitochondrial SOD isoform produces hydroxyl radical (Ganini et al., 2018).

- Many antioxidants “moonlight”. Sticking with SOD, the copper zinc isoform can act as a transcription factor (Tsang et al., 2014) and a cysteine oxidase (Winterbourn et al., 2002). Relatedly, SOD regulates electrochemistry by preventing superoxide, an excellent Brønsted base, consuming protons via spontaneous dismutation (Kettle et al., 2023).

- Some antioxidant enzymes react with many species. Like how superoxide also reacts with (and inactivates) CAT and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) (Blum and Fridovich, 1985; Kono and Fridovich, 1982), emerging evidence demonstrates that SOD metabolises hydrogen sulfide (Switzer et al., 2023), which complements prior evidence of reactivity, albeit kinetically slow, with hydrogen peroxide (Liochev and Fridovich, 2002).

- No specific antioxidants target the hydroxyl radical. If you had a 100 kg athlete, you’d need to load them with 50 kg of the antioxidant to meaningfully scavenge the hydroxyl radical on mass action and kinetic grounds (Dickinson and Chang, 2011; Winterbourn, 2008).

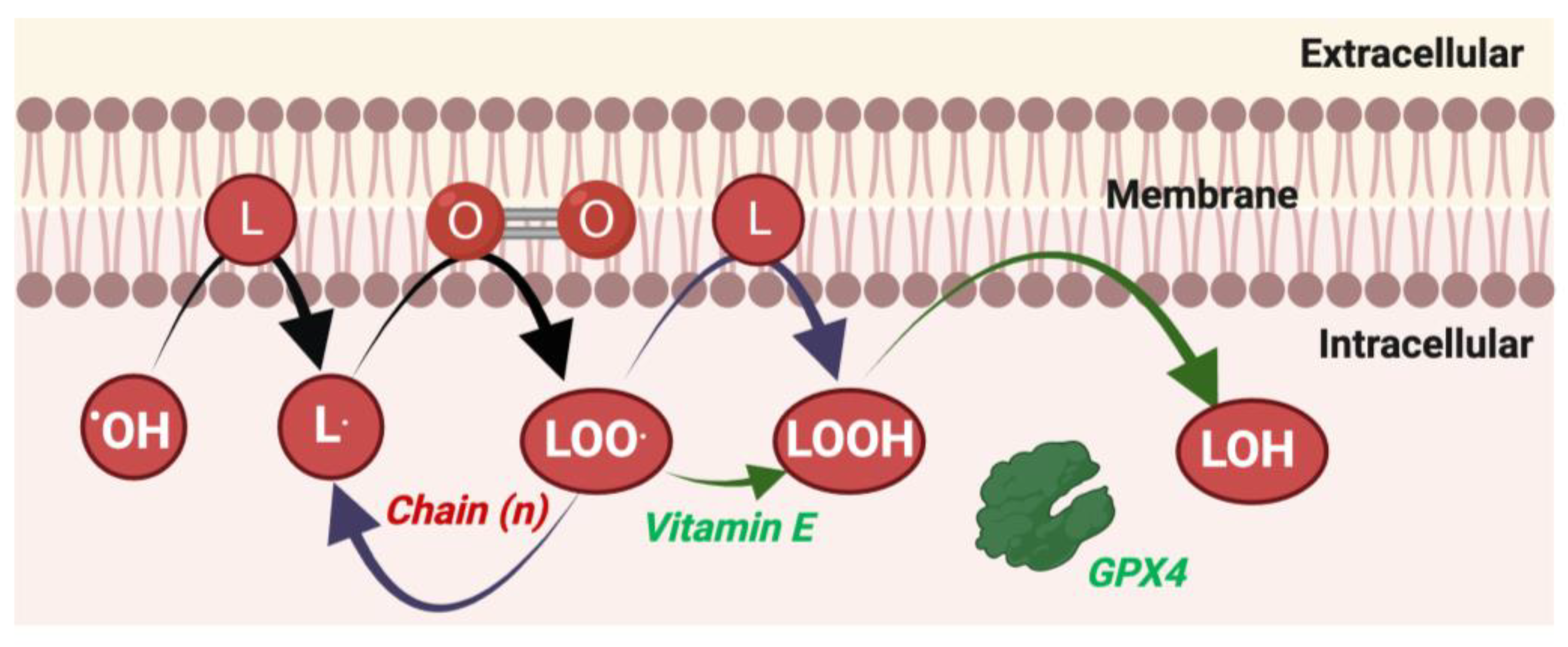

- Reactive species can be antioxidants. Nitric oxide reacts with lipid peroxyl radicals to terminate a free radical chain reaction (Niki, 2009; Yin et al., 2011). The nitrated lipids so-formed may possess anti-inflammatory properties (Melo et al., 2019).

- As in real estate, location matters. Polyphenols may be antioxidants in the gut (Halliwell et al., 2000) before being metabolised to and secreted in pro-oxidants forms (Owens et al., 2018). Touted ‘antioxidants’ like polyphenols often exert beneficial effects by acting as pro-oxidants (Halliwell, 2009, 2008).

1.4. Oxidative Stress

- One invariably exposes the sample to 21% oxygen. Mitochondrial superoxide production depends, in part, on [oxygen] (Murphy, 2009). So, raising [oxygen] from 1-10% to 21% (Ast and Mootha, 2019) by aerating the sample would be expected artificially increase superoxide production (Keeley and Mann, 2019).

- The ‘ROS’ in the sample will have inevitably disappeared before one can measure them. They ephemerally flit in and out of existence on nanosecond timescales (10-9 of a second). So, what is one really measuring? Potentially, the rate of artificial ROS production in a heavily oxygenated sample (Murphy et al., 2022).

- Although it is possible to minimise the above (e.g., degassing the sample and rapidly adding a probe), it is arduous. Even if artificial generation were minimised, a superoxide probe, for example, must still compete with SOD (Zielonka and Kalyanaraman, 2018), hampering the ability to detect all of the molecule in the sample. There is always the possibility of inadvertent artefacts, such as the release of redox-active iron ions from the haemolysis of erythrocytes in blood samples.

- Many lysis buffers contain ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide and lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) (Eid et al., 2024)

- Cutting-edge genetically encoded probes cannot be used in humans (Erdogan et al., 2021).

- It is an artificial redox challenge imposed on ex vivo biological material and may have questionable relevance to the ability of said material to ‘defend’ against other species, such as superoxide.

- It can be useful with aqueous antioxidants, like vitamin C, in so far as confirming nutrient loading, when combined with assays to measure the nutrient content, and potential for redox-activity. The potential is non-equivalent to the actual activity.

- The actual antioxidant activity of blood plasma will be influenced by erythrocytes and surrounding tissues, such as the endothelium.

- There are many commercial ‘kits’ for TAC. Please carefully consider their use and properly report their information. Statements like ‘TAC was measured with X-kit’ without detailing the procedure are discouraged.

- Use other assays to better interpret TAC in plasma (see cheat codes 4-9) and refrain from measuring it in tissues—as a general rule one would be better advised to measure antioxidant enzymes.

- Low-molecular weight ‘antioxidants’ also contribute to TAC activity. For example, peroxyl radicals react fast with cysteine, such as the micromole levels of albumin cysteine in plasma. Free radical chain reactions generate other ROS, such as superoxide (Winterbourn, 1993; Winterbourn and Metodiewa, 1994).

- The word total, unless carefully qualified (as in non-enzymatic capacity against peroxyl radical), is a misleading misnomer (Sies, 2007).

- Do consider the assay biochemistry. For instance, some SOD assays are prone to artefacts arising from other molecules able to reduce cytochrome c and the complex biochemistry of assay reporter molecules, such as nitro-blue tetrazolium (Beyer and Fridovich, 1987).

- Do quantify the systemic release of antioxidant enzymes by ELISA and immunoblot (Salzano et al., 2014), especially in exosomes (Lisi et al., 2023). Don’t measure GSH or antioxidant enzyme activity (e.g., GPX) in plasma/serum (Cobley et al., 2017). The concentration of GSH, glutathione reductase, and NADPH needed to sustain appreciable plasma GPX activity is minimal.

- Do use HPLC, with appropriate controls to block artificial oxidation (e.g., N-ethylmaleimide or iodoacetamide (Hansen and Winther, 2009)), to quantify GSH and GSSG. Don’t read too much into the thermodynamic reducing potential of the redox couple (GSH/GSSG) as computed using the Nernst equation (Flohé, 2013).

- Do follow best practice for quantitative immunoblotting using validated antibodies (Janes, 2015; Marx, 2013).

- Do consider the possibility that enzyme activities measured ex vivo may not reflect what is possible in vivo. For example, for thioredoxin reductasese much would depend on the continual supply of NAPDH (Jones and Sies, 2015).

- Do consider that there is no one true ‘best’ antioxidant (i.e., there is no one master antioxidant ring to rule them all).

| n | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

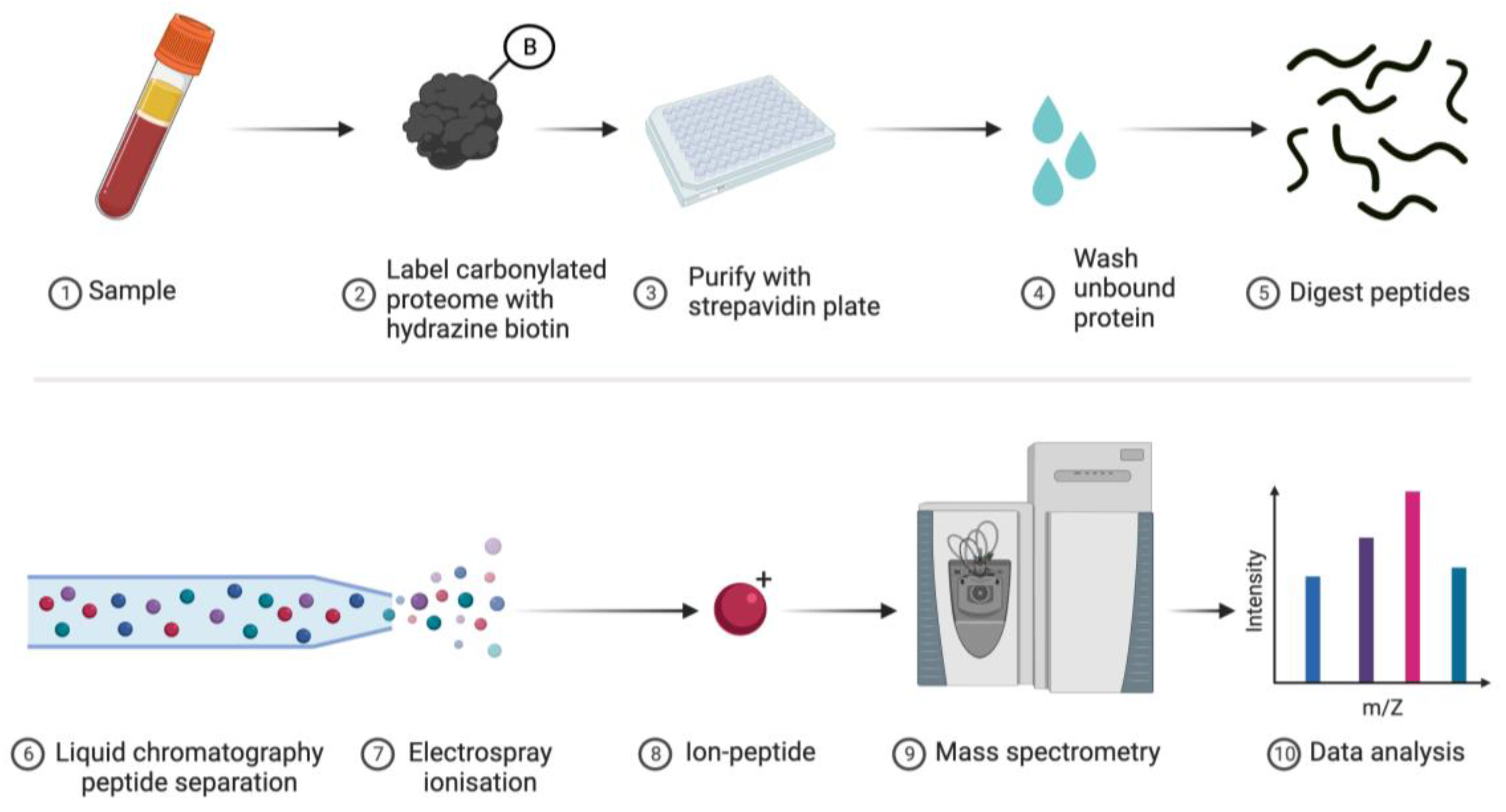

| 1 | Proteomics | One can collaborate with specialist labs or access services to identify and quantify specific types of oxidised amino acid, such as carbonylated proteins (see Figure 5), on a proteome-wide scale using bottom-up MS (Aebersold and Mann, 2003). Sophisticated modification specific workflows are available (Aldini et al., 2015; Batthyány et al., 2017; Bollineni et al., 2014; Fedorova et al., 2014; Madian et al., 2011; Madian and Regnier, 2010). |

| 2 | ELISA | Simple and user-friendly ELISA kits can quantify total protein carbonylation (Buss et al., 1997). |

| 3 | Immunoblot | Pan-proteome immunoblots with modification specific antibodies or derivatisation reagents can be performed (Cobley et al., 2014). The OxyBlot™ for protein carbonylation represents an enduringly popular approach (Frijhoff et al., 2015). |

| 4 | Fluorescent | Derivatising protein carbonyl groups with fluorophores, such as rhodamine-B hydrazine, allows for quantifying their levels via SDS-PAGE (Georgiou et al., 2018; Weber et al., 2015), especially when protein content can be normalised with a spectrally-distinct amine-reactive probe like AlexaFluor™647-N-hydroxysuccinimide (F-NHS). Novel N-terminal reactive reagents, such as 2-pyridinecarboxyaldehyde, may also be used (Bridge et al., 2023; MacDonald et al., 2015). |

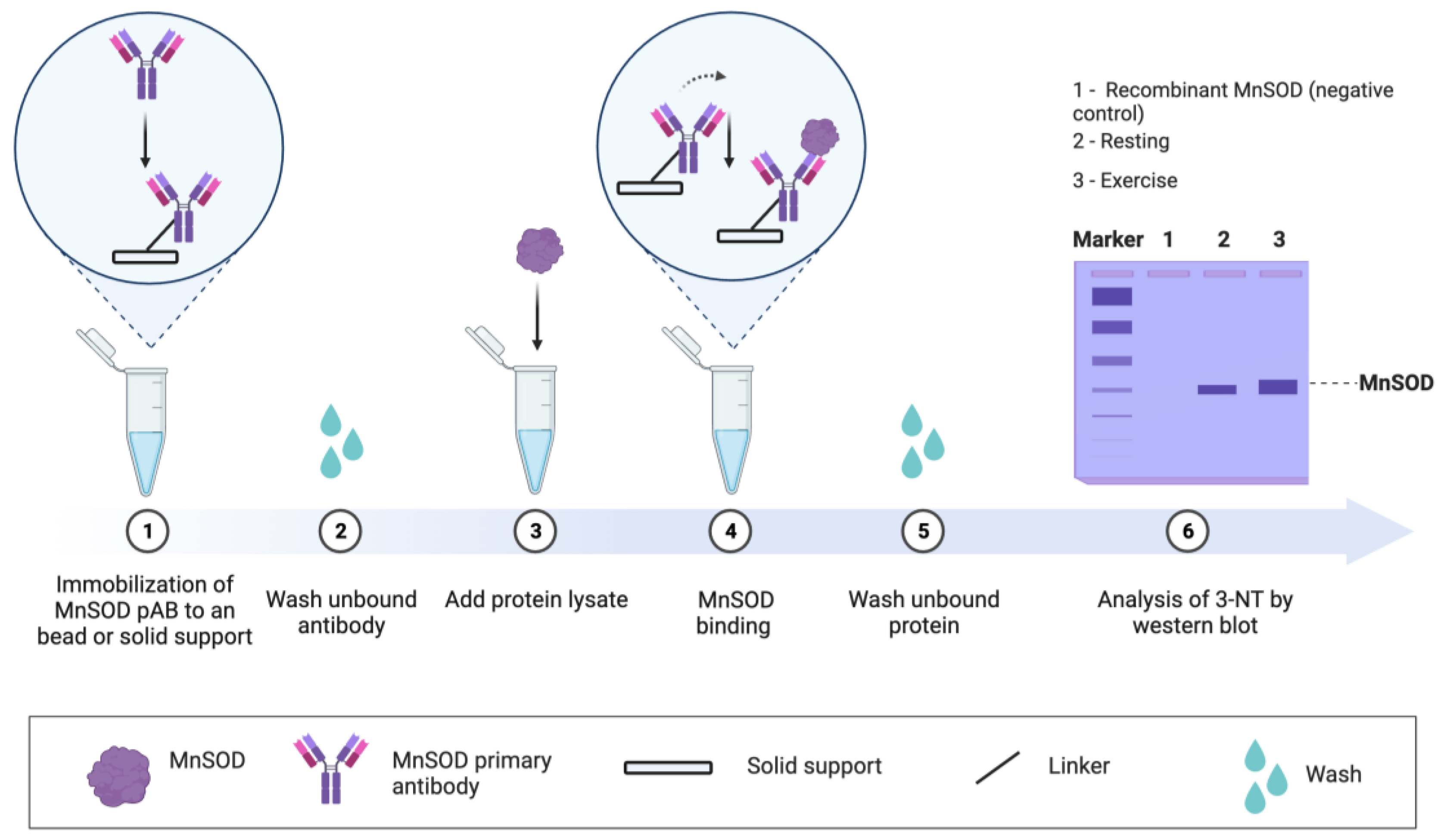

| 5 | Targeted | Specific proteins can be analysed by 1-4, such as MS for residue level analysis (Cobley et al., 2019b), when a protein is immunopurified. Targeted approaches can address specific questions (Place et al., 2015; Safdar et al., 2010), especially when the functional impact of the oxidation event is known (see Figure 6). For example, tyrosine 34 nitration impairs manganese SOD activity by electrically repelling superoxide (MacMillan-Crow et al., 1996). Electrostatic repulsion helps explain why the rate of superoxide dismutation via O2.- + O2.- colliding to form hydrogen peroxide and oxygen is near zero (Fridovich, 1989). Approach 4 combined with an ELISA assay may support protein-specific oxidative damage analysis in a microplate. |

- Assay techniques: The validated analytical tools relating to DNA oxidation are applicable to RNA oxidation, as the latter is quantified using ELISA, PCR-based technology, and chromatograph procedures, such as HPLC with electrochemical potential detection (Floyd et al., 1986) and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry or gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Dizdaroglu et al., 2001; Larsen et al., 2019). Note, most ELISA kits cannot discriminate between RNA and DNA oxidation products (Larsen et al, 2022).

- Sample type: RNA oxidation can be quantified in urine, blood and/or tissue (cells). Detection of 8-oxoGuo urinary excretion is possible but must be corrected for urine dilution (via urine volume, creatinine or density). Blood plasma is an acceptable material to measure RNA oxidation, although the data should be carefully interpreted with appropriate physiological modelling (Larsen et al., 2019; Poulsen et al., 2019). Tissue quantification has the advantage of tissue-specific interpretation, unlike plasma and urine collection (Larsen et al, 2022).

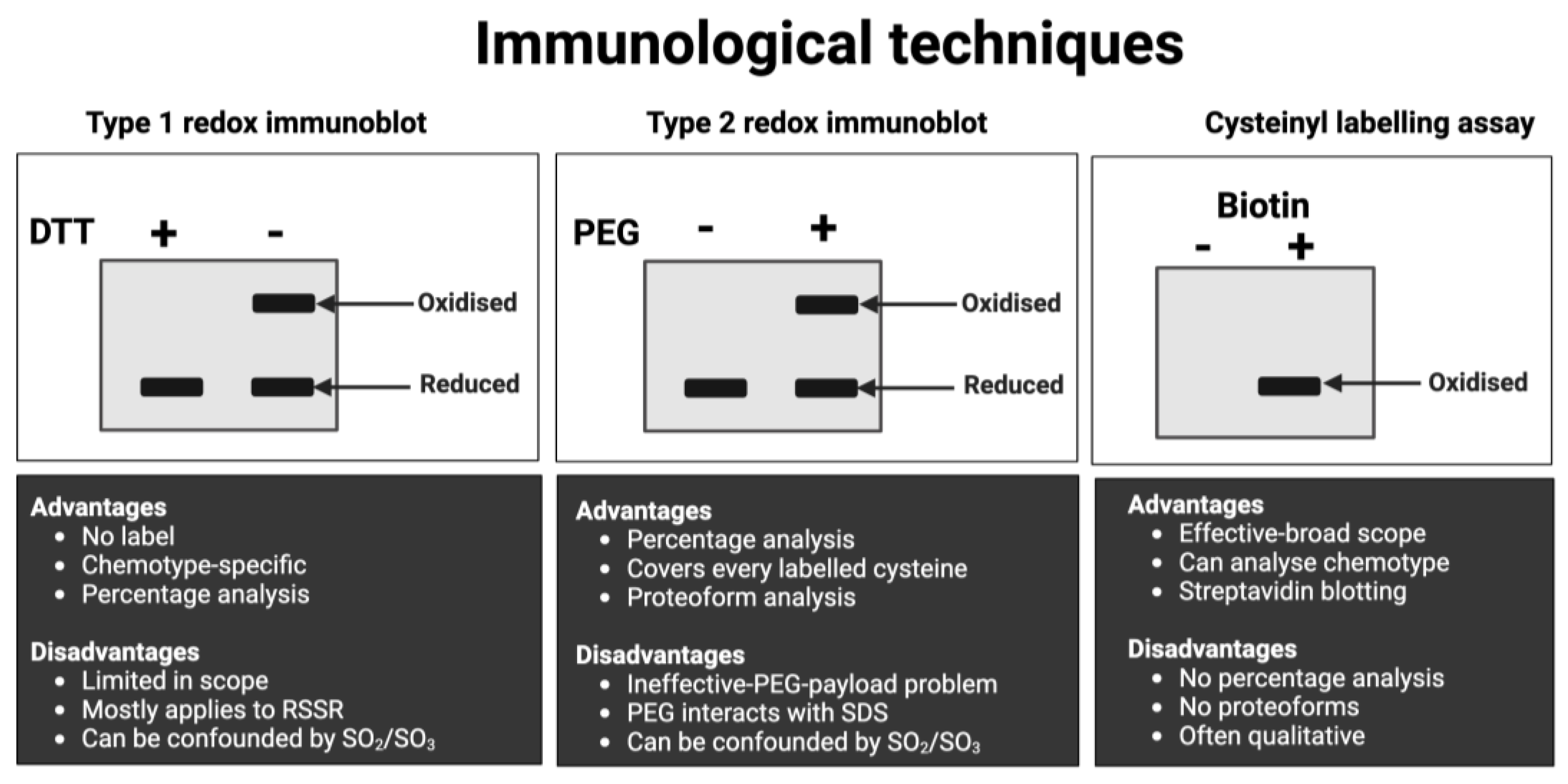

- Do minimise artificial cysteine oxidation by alkylating reduced cysteines with suitable reagents, such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). Note these reagents can label other amino acids, react with sulfenic acids, and persulfides (Hansen and Winther, 2009; Reisz et al., 2013; Schilling et al., 2022).

- Do bear in mind that not every protein and every cysteine is yet measurable in one run using MS technology (Timp and Timp, 2020).

- Do consider that different workflows measure different forms of cysteine oxidation, so-called chemotypes. For example, a chemotype-specific proteomic approach demonstrated that fatiguing exercise increased S-glutathionylation, cysteine covalently attached to glutathione via a disulfide bond, in mice (Kramer et al., 2018).

- Do consider supplementing the analysis with global readouts of cysteine oxidation, such as an Ellman’s test (Ellman, 1959), or chemotype-specific pan-proteome immunoblots (Saurin et al., 2004).

- Do consider that many techniques don’t measure “over-oxidised” chemotypes, such as sulfinic acids.

- Don’t assume a technique will necessarily work! Mobility-shift immunoblots usually fail to detect the protein because the bulky PEG-payloads sterically block primary antibody binding.

- Don’t assume cysteine oxidation is functional without evidence.

- Don’t assume the cysteine oxidation is necessarily oxidative eustress without evidence.

- Don’t assume an outcome assay result is caused by cysteine oxidation without evidence.

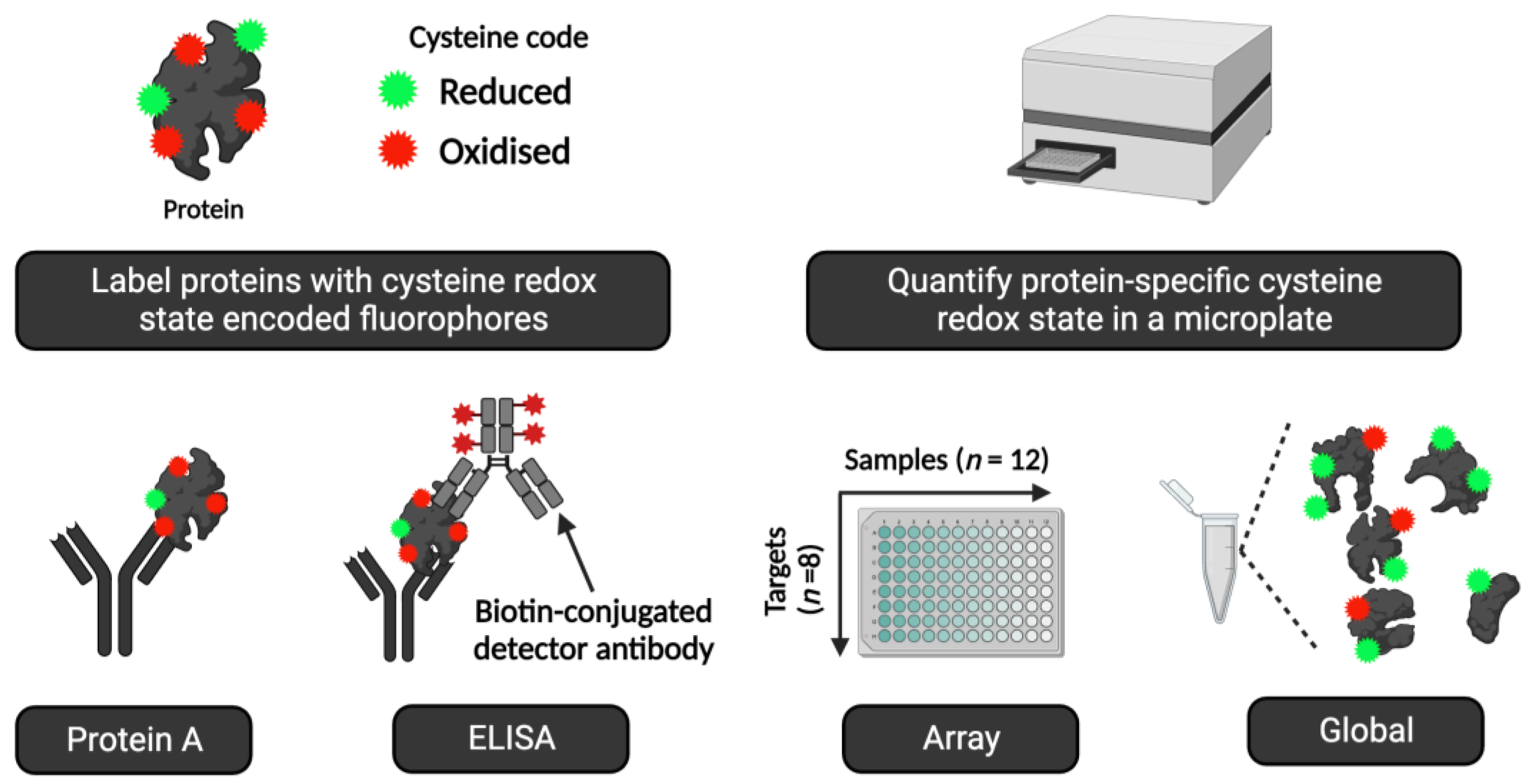

- Standard operating procedures are available (Tuncay et al., 2022). The cysteine labelling procedures can be adapted to suit specific experimental needs. For example, to omit some costly preparatory steps, reduced cysteines can be labelled with an F-MAL in ALISA. In this case, increased cysteine oxidation would decrease the observed F-MAL signal.

- The assays can operate in different modes, from global (i.e., all proteins/no antibodies) to multiparametric array mode, in microscale and macroscale (e.g., slab-gel format).

- In some cases, the assays provide information on protein function, such as the difference in transcription factor cysteine redox states in the cytosol vs. the nucleus.

- Interpretationally, a change reflects a difference in the rate of ROS-sensitive cysteine oxidation and antioxidant-sensitive reduction across the entire protein. The summed weighted mean of all individual residues. Responding to both ROS and AOX inputs is useful.

- The assays are compatible with chemotype-specific* cysteine labelling (Alcock et al., 2017) and direct-reactivity approaches (Shi and Carroll, 2020). For example, the methods are compatible with reaction-based sulfenic acid fluorophores (Ferreira et al., 2022).

- Unless the target has one cysteine like ND3-Cys39 in complex I (Burger et al., 2022; Chouchani et al., 2013), the assays cannot disclose the identity of the oxidised cysteine residues.

- For some exercise-sensitive proteins, such as PGC-1α (Cobley et al., 2012; Egan and Sharples, 2023; Egan and Zierath, 2013), the lack of an ELISA kit may make it impossible to run the assay.

| Type | Benefit | Description (useful property as applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA | Throughput Multiplexed Sensitive Rapid |

High sample n-plex analysis (adds statistical power) Parallel assessment of multiple 2-10 proteins (enables screening) Picomole sensitivity (supports human biomarker studies) Performed in 1 day with minimal hands-on time (benefits screens) |

| Redox | Cysteine holistic Percentages Moles Context Chemotype Process-sensitive |

Agnostic of any one cysteine residue (adds coverage of the entire molecule) Quantifies cysteine redox state in percentages (interpretational useful) Quantifies cysteine redox state in moles (interpretational useful) Provides cysteine proteome context (interpretationally use) Support chemotype-specific analysis (supports mechanistic studies) Results are sensitive to oxidative and antioxidative processes scaled across every cysteine residue on the target protein (interpretationally useful) |

| Performance | Valid Effective Accurate Reliable Reproducible Range |

Draws on highly-principled redox and immunological methods (robust) They work (e.g., compare to Click-PEG) (means to study the specific protein) Data correspond to ground-truth standards (adds percentage analysis) High consistency between samples (adds robustness) Delivers consistent results (adds robustness) Operates across a large dynamic range (useful for human applications) |

| Microplate | Simple Easy-to-do Off-the-shelf Automated |

Simple to understand, interpret, and operate (supports accessibility) Little technical skill required to deliver actionable results (accessibility) Compatible with commercial ELISA kits (accessibility) Delivers rapid and automated data within seconds (time-efficient) |

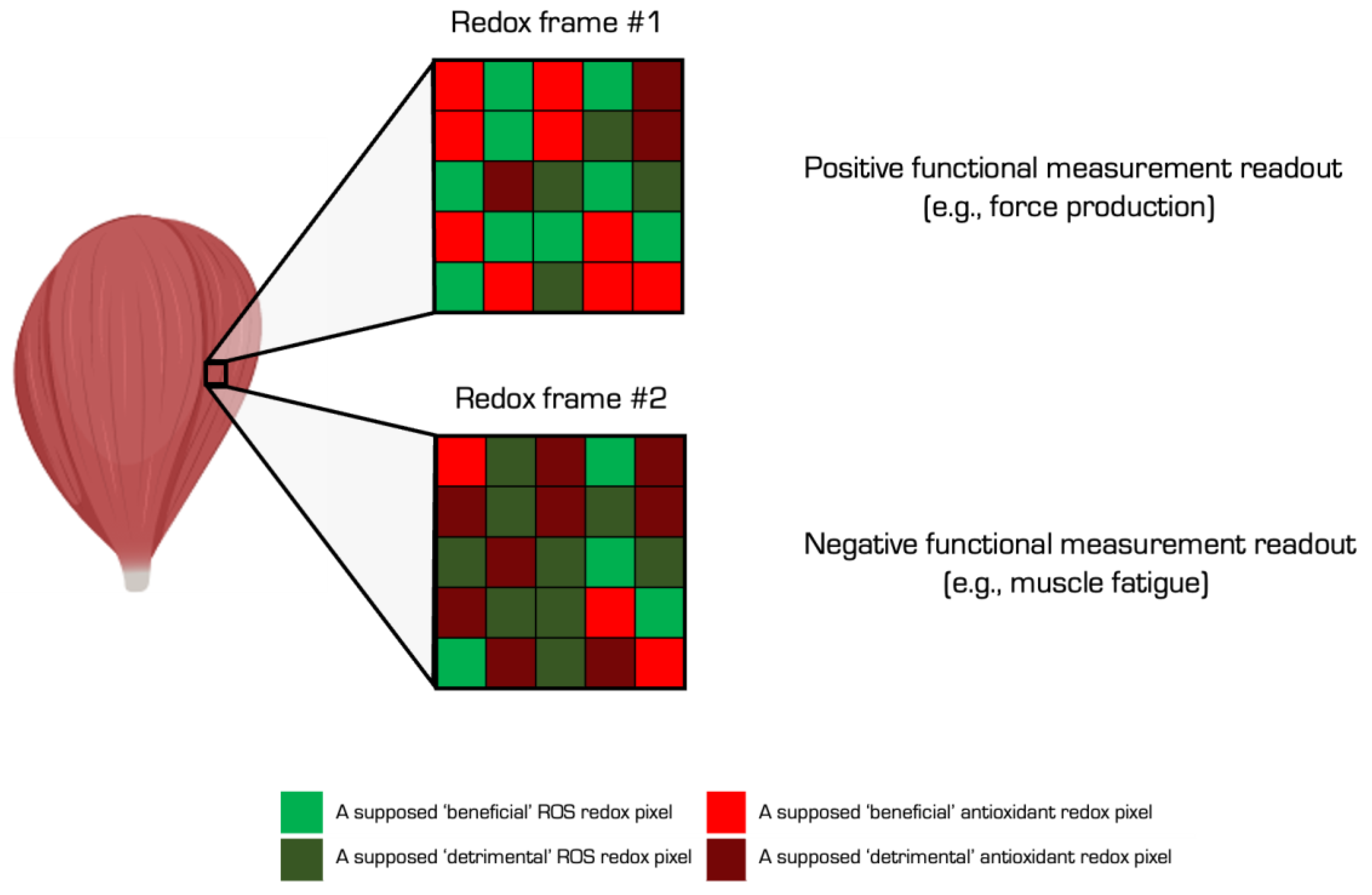

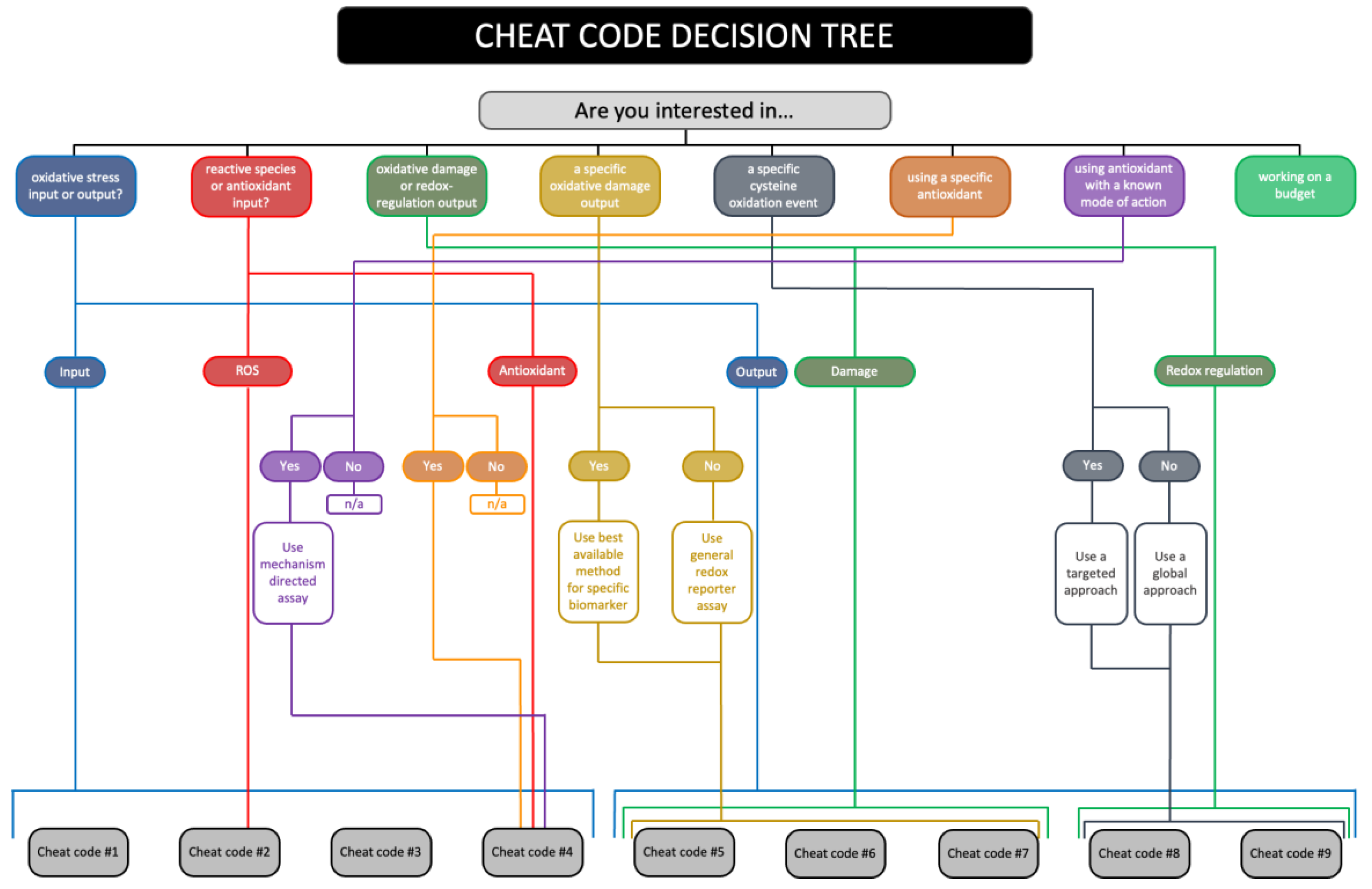

- Whether the redox approach is general or targeted, where the general ‘catch-all’ approach analyses as many distinct oxidative stress processes as possible and targeted ones focus on a specific process, such as lipid peroxidation. In both cases, multiple process-specific analytical indices are preferred. Still, the depth of the analyses depends on whether oxidative stress is a primary, secondary, or tertiary biochemical outcome variable.

- The type of biological material acquired, usually blood and/or tissue samples, and the number of samples dictate what can be measured and how. For example, performing MS-based proteomic analysis on 100 samples is unlikely to be financially viable. Relatedly, the relevant equipment and expertise to undertake the analysis must be available.

- Whether (1) a redox-active molecule, such as antioxidant or pro-oxidant (Jordan et al., 2021)) is being studied, (2) oxidative eustress or distress (e.g., harmful age-related DNA damage (Cobley et al., 2013)), is being studied, and (3) oxidative stress is linked to a given outcome variable, such as exercise adaptations.

- Cheat code 4 to verify increased NAC loading via HPLC-based analysis of plasma NAC. And assay GSH and GPX activity in erythrocytes or tissue lysates to infer whether NAC supports the glutathione redox system (Giustarini et al., 2023). This might be expected to alter peroxide metabolism and hence oxidative damage to proteins via lipid peroxidation products, such as 4-HNE (Zhang and Forman, 2017).

- Cheat code 5 to measure lipid peroxidation. In plasma, one might measure LOOH and 4-HNE via the FOX assay and immunoblotting, respectively. In tissue samples, one might measure 4-HNE via immunoblotting. Equally, one might implement a F2-isoprostanes ELISA in plasma or tissue (Paschalis et al., 2018).

- Cheat code 6 to measure oxidative damage to contractile proteins using targeted analysis. Immunocapture of a specific protein followed by immunoblot analysis for 4-HNE, 3-NT, or protein carbonyls (Place et al., 2015). Like how cutting fingernails yields thiyl radicals in alpha keratin (Chandra and Symons, 1987), mechanical stress produces protein-based free radicals (Zapp et al., 2020). Hence, one could add a spin trap to ‘clamp’ protein radicals for targeted immunoblot analysis with an anti-trap reagent (Mason and Ganini, 2019). If only circulating samples were available, the same approaches could be applied in these compartments to test the plausibility of NAC minimising oxidative damage to proteins (albeit non-contractile ones).

- Cheat codes 8-9 with chemotype analysis to determine whether NAC by supporting hydrogen sulfide production elicits beneficial effects by inducing contractile protein-specific persulfidation (Ezeriņa et al., 2018; Kalyanaraman, 2022; Pedre et al., 2021). If fluorescent labels are used, then cheat code 6, 8 and 9 could be implemented simultaneously (Zivanovic et al., 2019). For example, gel-based detection of persulfidation before 4-HNE immunoblotting.

| Are you interested in the | Answer | Refinement | Selection outcomes | Assay (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress input or output? | Output | n/a | Consider cheat codes 5-9 Disregard cheat codes 1 & 2 |

n/a |

|

Reactive species or antioxidant input? |

Yes | Interested in an antioxidant (yes) | Consider cheat code 4 Disregard cheat codes 1-3 |

n/a |

|

Oxidative damage or redox regulation output? |

Both | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| A specific oxidative damage output? | Yes | Yes | Consider cheat code 5-6 Disregard cheat code 7 (based on mechanism) |

Global 4-HNE immunoblot Contractile protein immunocapture for targeted 4-HNE analysis |

| A specific cysteine oxidation event? | Yes | Yes | Consider cheat codes 8 & 9 | Gel-based analysis of persulfides using a fluorescent probe |

| Using a specific antioxidant? | Yes | n/a | Consider cheat code 4 | n/a |

| Using an antioxidant with a known mode of action? | Yes | Use mechanism directed assay | Consider cheat code 4 | HPLC of [NAC] |

- Cheat code 4: GSH levels (systemic or tissue). Or cheat code 10 (see below).

- Cheat code 5: 4-HNE blot (systemic or tissue).

- Cheat code 6: Myosin-specific 4-HNE levels (tissue).

- NAC enters the circulation before it or a metabolite thereof accumulates in skeletal muscle (checked via cheat code 4: HPLC analysis of NAC).

- NAC indirectly acts as an antioxidant by impacting on a process that influences the oxidation of contractile proteins. The former can be checked via GSH-related lipid peroxidation analysis (cheat code 4-5) and the latter by targeted oxidative damage analysis pursuant to cheat code 6 or hydrogen sulfide donor effect per cheat code 8 or 9.

- By so doing, NAC impacts a whole-body marker of fatigue, such as exercise performance.

2. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adhikari, S., Nice, E.C., Deutsch, E.W., Lane, L., Omenn, G.S., Pennington, S.R., Paik, Y.-K., Overall, C.M., Corrales, F.J., Cristea, I.M., Eyk, J.E.V., Uhlén, M., Lindskog, C., Chan, D.W., Bairoch, A., Waddington, J.C., Justice, J.L., LaBaer, J., Rodriguez, H., He, F., Kostrzewa, M., Ping, P., Gundry, R.L., Stewart, P., Srivastava, Sanjeeva, Srivastava, Sudhir, Nogueira, F.C.S., Domont, G.B., Vandenbrouck, Y., Lam, M.P.Y., Wennersten, S., Vizcaino, J.A., Wilkins, M., Schwenk, J.M., Lundberg, E., Bandeira, N., Marko-Varga, G., Weintraub, S.T., Pineau, C., Kusebauch, U., Moritz, R.L., Ahn, S.B., Palmblad, M., Snyder, M.P., Aebersold, R., Baker, M.S., 2020. A high-stringency blueprint of the human proteome. Nat Commun 11, 5301. [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R., Agar, J.N., Amster, I.J., Baker, M.S., Bertozzi, C.R., Boja, E.S., Costello, C.E., Cravatt, B.F., Fenselau, C., Garcia, B.A., Ge, Y., Gunawardena, J., Hendrickson, R.C., Hergenrother, P.J., Huber, C.G., Ivanov, A.R., Jensen, O.N., Jewett, M.C., Kelleher, N.L., Kiessling, L.L., Krogan, N.J., Larsen, M.R., Loo, J.A., Loo, R.R.O., Lundberg, E., MacCoss, M.J., Mallick, P., Mootha, V.K., Mrksich, M., Muir, T.W., Patrie, S.M., Pesavento, J.J., Pitteri, S.J., Rodriguez, H., Saghatelian, A., Sandoval, W., Schlüter, H., Sechi, S., Slavoff, S.A., Smith, L.M., Snyder, M.P., Thomas, P.M., Uhlén, M., Eyk, J.E.V., Vidal, M., Walt, D.R., White, F.M., Williams, E.R., Wohlschlager, T., Wysocki, V.H., Yates, N.A., Young, N.L., Zhang, B., 2018. How many human proteoforms are there? Nat Chem Biol 14, 206–214. [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R., Mann, M., 2003. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 422, 198–207. [CrossRef]

- Akter, S., Fu, L., Jung, Y., Conte, M.L., Lawson, J.R., Lowther, W.T., Sun, R., Liu, K., Yang, J., Carroll, K.S., 2018. Chemical proteomics reveals new targets of cysteine sulfinic acid reductase. Nat Chem Biol 14, 995–1004. [CrossRef]

- Alcock, L.J., Perkins, M.V., Chalker, J.M., 2017. Chemical methods for mapping cysteine oxidation. Chem Soc Rev 47, 231–268. [CrossRef]

- Aldini, G., Domingues, M.R., Spickett, C.M., Domingues, P., Altomare, A., Sánchez-Gómez, F.J., Oeste, C.L., Pérez-Sala, D., 2015. Protein lipoxidation: Detection strategies and challenges. Redox Biol 5, 253–266. [CrossRef]

- Alhmoud, J.F., Woolley, J.F., Moustafa, A.-E.A., Malki, M.I., 2020. DNA Damage/Repair Management in Cancers. Cancers 12, 1050. [CrossRef]

- Allison, W.S., 1976. Formation and reactions of sulfenic acids in proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 9, 293–299. [CrossRef]

- Anschau, V., Ferrer-Sueta, G., Aleixo-Silva, R.L., Fernandes, R.B., Tairum, C.A., Tonoli, C.C.C., Murakami, M.T., Oliveira, M.A. de, Netto, L.E.S., 2020. Reduction of sulfenic acids by ascorbate in proteins, connecting thiol-dependent to alternative redox pathways. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 156, 207–216. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F., Brito, P.M., 2017. Quantitative biology of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Redox Biol 13, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Armas, M.I.D., Esteves, R., Viera, N., Reyes, A.M., Mastrogiovanni, M., Alegria, T.G.P., Netto, L.E.S., Tórtora, V., Radi, R., Trujillo, M., 2019. Rapid peroxynitrite reduction by human peroxiredoxin 3: Implications for the fate of oxidants in mitochondria. Free Radical Bio Med 130, 369–378. [CrossRef]

- Arnér, E.S.J., 2017. Selenoproteins, Methods and Protocols. Methods Mol Biology 1661, 301–309. [CrossRef]

- Ast, T., Mootha, V.K., 2019. Oxygen and mammalian cell culture: are we repeating the experiment of Dr. Ox? Nat Metabolism 1, 858–860. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.M., Culcasi, M., Filipponi, T., Brugniaux, J.V., Stacey, B.S., Marley, C.J., Soria, R., Rimoldi, S.F., Cerny, D., Rexhaj, E., Pratali, L., Salmòn, C.S., Jáuregui, C.M., Villena, M., Villafuerte, F., Rockenbauer, A., Pietri, S., Scherrer, U., Sartori, C., 2022. EPR spectroscopic evidence of iron-catalysed free radical formation in chronic mountain sickness: Dietary causes and vascular consequences. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 184, 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.M., Davies, B., Young, I.S., Jackson, M.J., Davison, G.W., Isaacson, R., Richardson, R.S., 2003. EPR spectroscopic detection of free radical outflow from an isolated muscle bed in exercising humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 94, 1714–1718. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.S., Ahn, S.B., Mohamedali, A., Islam, M.T., Cantor, D., Verhaert, P.D., Fanayan, S., Sharma, S., Nice, E.C., Connor, M., Ranganathan, S., 2017. Accelerating the search for the missing proteins in the human proteome. Nat Commun 8, 14271. [CrossRef]

- Barayeu, U., Schilling, D., Eid, M., Silva, T.N.X. da, Schlicker, L., Mitreska, N., Zapp, C., Gräter, F., Miller, A.K., Kappl, R., Schulze, A., Angeli, J.P.F., Dick, T.P., 2022. Hydropersulfides inhibit lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by scavenging radicals. Nat Chem Biol 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Bartosz, G., 2010. Non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity assays: Limitations of use in biomedicine. Free Radic. Res. 44, 711–720. [CrossRef]

- Batthyány, C., Bartesaghi, S., Mastrogiovanni, M., Lima, A., Demicheli, V., Radi, R., 2017. Tyrosine-Nitrated Proteins: Proteomic and Bioanalytical Aspects. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 26, 313–328. [CrossRef]

- Bayır, H., Anthonymuthu, T.S., Tyurina, Y.Y., Patel, S.J., Amoscato, A.A., Lamade, A.M., Yang, Q., Vladimirov, G.K., Philpott, C.C., Kagan, V.E., 2020. Achieving Life through Death: Redox Biology of Lipid Peroxidation in Ferroptosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 387–408. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C., Fridovich, I., 1971. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44, 276–287. [CrossRef]

- Bellissimo, C.A., Delfinis, L.J., Hughes, M.C., Turnbull, P.C., Gandhi, S., DiBenedetto, S.N., Rahman, F.A., Tadi, P., Amaral, C.A., Dehghani, A., Cobley, J., Quadrilatero, J., Schlattner, U., Perry, C.G.R., 2023. Mitochondrial creatine sensitivity is lost in the D2.mdx model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and rescued by the mitochondrial-enhancing compound Olesoxime. Am J Physiol-cell Ph. [CrossRef]

- Belousov, V.V., Fradkov, A.F., Lukyanov, K.A., Staroverov, D.B., Shakhbazov, K.S., Terskikh, A.V., Lukyanov, S., 2006. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Methods 3, 281–286. [CrossRef]

- Bersani, N.A., Merwin, J.R., Lopez, N.I., Pearson, G.D., Merrill, G.F., 2002. Protein Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay to Monitor Redox State of Thioredoxin in Cells. Methods Enzym. 347, 317–326. [CrossRef]

- Beyer, W.F., Fridovich, I., 1987. Assaying for superoxide dismutase activity: Some large consequences of minor changes in conditions. Anal. Biochem. 161, 559–566. [CrossRef]

- Bielski, B.H.J., Cabelli, D.E., Arudi, R.L., Ross, A.B., 1985. Reactivity of HO2/O−2 Radicals in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 14, 1041–1100. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, E., Lang, L., Zimmermann, J., Luczak, M., Kiefer, A.M., Niedner-Schatteburg, G., Manolikakes, G., Morgan, B., Deponte, M., 2023. Glutathione kinetically outcompetes reactions between dimedone and a cyclic sulfenamide or physiological sulfenic acids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 208, 165–177. [CrossRef]

- Biteau, B., Labarre, J., Toledano, M.B., 2003. ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine–sulphinic acid by S. cerevisiae sulphiredoxin. Nature 425, 980–984. [CrossRef]

- Bleier, L., Wittig, I., Heide, H., Steger, M., Brandt, U., Dröse, S., 2015. Generator-specific targets of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Free Radical Bio Med 78, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Blum, J., Fridovich, I., 1985. Inactivation of glutathione peroxidase by superoxide radical. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 240, 500–508. [CrossRef]

- Boivin, B., Zhang, S., Arbiser, J.L., Zhang, Z.-Y., Tonks, N.K., 2008. A modified cysteinyl-labeling assay reveals reversible oxidation of protein tyrosine phosphatases in angiomyolipoma cells. Proc National Acad Sci 105, 9959–9964. [CrossRef]

- Bollineni, R.C., Hoffmann, R., Fedorova, M., 2014. Proteome-wide profiling of carbonylated proteins and carbonylation sites in HeLa cells under mild oxidative stress conditions. Free Radical Bio Med 68, 186–195. [CrossRef]

- Bonini, M.G., Rota, C., Tomasi, A., Mason, R.P., 2006. The oxidation of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin to reactive oxygen species: A self-fulfilling prophesy? Free Radical Bio Med 40, 968–975. [CrossRef]

- Boveris, A., Chance, B., 1973. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem. J. 134, 707–716. [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.M., Meyer, A.S., 2022. Cataloguing the proteome: Current developments in single-molecule protein sequencing. Biophys. Rev. 3, 011304. [CrossRef]

- Bridge, H.N., Leiter, W., Frazier, C.L., Weeks, A.M., 2023. An N terminomics toolbox combining 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde probes and click chemistry for profiling protease specificity. Cell Chem. Biol. [CrossRef]

- Brigelius-Flohé, R., Flohé, L., 2011. Basic Principles and Emerging Concepts in the Redox Control of Transcription Factors. Antioxid Redox Sign 15, 2335–2381. [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, H., Kang, A.S.W., Liu, J., Aksimentiev, A., Dekker, C., 2021. Multiple rereads of single proteins at single–amino acid resolution using nanopores. Science 374, 1509–1513. [CrossRef]

- Brito, P.M., Antunes, F., 2014. Estimation of kinetic parameters related to biochemical interactions between hydrogen peroxide and signal transduction proteins. Front. Chem. 2, 82. [CrossRef]

- Bryk, R., Griffin, P., Nathan, C., 2000. Peroxynitrite reductase activity of bacterial peroxiredoxins. Nature 407, 211–215. [CrossRef]

- Buettner, G.R., 2011. Superoxide Dismutase in Redox Biology: The Roles of Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide. Anti-cancer Agent Me 11, 341–346. [CrossRef]

- Burger, N., James, A.M., Mulvey, J.F., Hoogewijs, K., Ding, S., Fearnley, I.M., Loureiro-López, M., Norman, A.A.I., Arndt, S., Mottahedin, A., Sauchanka, O., Hartley, R.C., Krieg, T., Murphy, M.P., 2022. ND3 Cys39 in complex I is exposed during mitochondrial respiration. Cell Chem Biol 29, 636-649.e14. [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, J.R., Madhani, M., Cuello, F., Charles, R.L., Brennan, J.P., Schröder, E., Browning, D.D., Eaton, P., 2007. Cysteine Redox Sensor in PKGIa Enables Oxidant-Induced Activation. Science 317, 1393–1397. [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, J.R., Oviosu, O., Eaton, P., 2013. The PEG-switch assay: A fast semi-quantitative method to determine protein reversible cysteine oxidation. J Pharmacol Toxicol 68, 297–301. [CrossRef]

- Burgunder, J.M., Varriale, A., Lauterburg, B.H., 1989. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on plasma cysteine and glutathione following paracetamol administration. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 36, 127–131. [CrossRef]

- Buss, H., Chan, T.P., Sluis, K.B., Domigan, N.M., Winterbourn, C.C., 1997. Protein Carbonyl Measurement by a Sensitive ELISA Method. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 23, 361–366. [CrossRef]

- Carbonara, K., Andonovski, M., Coorssen, J.R., 2021. Proteomes Are of Proteoforms: Embracing the Complexity. Proteomes 9, 38. [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, G., Mastrogiovanni, M., Zeida, A., Viera, N., Radi, R., Reyes, A.M., Trujillo, M., 2023. Mitochondrial Peroxiredoxin 3 Is Rapidly Oxidized and Hyperoxidized by Fatty Acid Hydroperoxides. Antioxidants 12, 408. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, L., Pattison, D.I., Davies, J.B., Anderson, R.F., Lopez-Alarcon, C., Davies, M.J., 2018. Superoxide radicals react with peptide-derived tryptophan radicals with very high rate constants to give hydroperoxides as major products. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 118, 126–136. [CrossRef]

- Chance, B., Sies, H., Boveris, A., 1979. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev 59, 527–605. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, H., Symons, M.C.R., 1987. Sulphur radicals formed by cutting α-keratin. Nature 328, 833–834. [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, P.N., Margaritelis, N.V., Paschalis, V., Theodorou, A.A., Vrabas, I.S., Kyparos, A., D’Alessandro, A., Nikolaidis, M.G., 2024. Erythrocyte metabolism. Acta Physiol. e14081. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G., Zielonka, M., Dranka, B., Kumar, S.N., Myers, C.R., Bennett, B., Garces, A.M., Machado, L.G.D.D., Thiebaut, D., Ouari, O., Hardy, M., Zielonka, J., Kalyanaraman, B., 2018. Detection of mitochondria-generated reactive oxygen species in cells using multiple probes and methods: Potentials, pitfalls, and the future. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 10363–10380. [CrossRef]

- Chouchani, E.T., Methner, C., Nadtochiy, S.M., Logan, A., Pell, V.R., Ding, S., James, A.M., Cochemé, H.M., Reinhold, J., Lilley, K.S., Partridge, L., Fearnley, I.M., Robinson, A.J., Hartley, R.C., Smith, R.A.J., Krieg, T., Brookes, P.S., Murphy, M.P., 2013. Cardioprotection by S-nitrosation of a cysteine switch on mitochondrial complex I. Nat Med 19, 753–759. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J., Noble, A., Bessell, R., Guille, M., Husi, H., 2020. Reversible Thiol Oxidation Inhibits the Mitochondrial ATP Synthase in Xenopus laevis Oocytes. Antioxidants 9, 215. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, James.N., Davison, G.W., 2022. Oxidative Eustress in Exercise Physiology. CRC Press.

- Cobley, J.N., 2023a. 50 shades of oxidative stress: A state-specific cysteine redox pattern hypothesis. Redox Biol. 67, 102936. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., 2023b. Oxiforms: Unique cysteine residue- and chemotype-specified chemical combinations can produce functionally-distinct proteoforms. Bioessays 45. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, James N., 2020. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial ROS Production in Assisted Reproduction: The Known, the Unknown, and the Intriguing. Antioxidants 9, 933. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, James Nathan, 2020. Oxidative Stress 447–462. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., 2018. Synapse Pruning: Mitochondrial ROS with Their Hands on the Shears. Bioessays 40, 1800031. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Bartlett, J.D., Kayani, A., Murray, S.W., Louhelainen, J., Donovan, T., Waldron, S., Gregson, W., Burniston, J.G., Morton, J.P., Close, G.L., 2012. PGC-1α transcriptional response and mitochondrial adaptation to acute exercise is maintained in skeletal muscle of sedentary elderly males. Biogerontology 13, 621–631. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Close, G.L., Bailey, D.M., Davison, G.W., 2017. Exercise redox biochemistry: Conceptual, methodological and technical recommendations. Redox Biol 12, 540–548. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Davison, G.W., 2022. Oxidative Eustress in Exercise Physiology 11–22. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Fiorello, M.L., Bailey, D.M., 2018. 13 reasons why the brain is susceptible to oxidative stress. Redox Biol 15, 490–503. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Husi, H., 2020. Immunological Techniques to Assess Protein Thiol Redox State: Opportunities, Challenges and Solutions. Antioxidants 9, 315. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Malik, Z.Ab., Morton, J.P., Close, G.L., Edwards, B.J., Burniston, J.G., 2016. Age- and Activity-Related Differences in the Abundance of Myosin Essential and Regulatory Light Chains in Human Muscle. Proteomes 4, 15. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Margaritelis, N.V., Morton, J.P., Close, G.L., Nikolaidis, M.G., Malone, J.K., 2015a. The basic chemistry of exercise-induced DNA oxidation: oxidative damage, redox signaling, and their interplay. Front Physiol 6, 182. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Marrin, K., 2012. Vitamin E supplementation does not alter physiological performance at fixed blood lactate concentrations in trained runners. J. sports Med. Phys. Fit. 52, 63–70.

- Cobley, J.N., McGlory, C., Morton, J.P., Close, G.L., 2011. N-Acetylcysteine’s Attenuation of Fatigue After Repeated Bouts of Intermittent Exercise: Practical Implications for Tournament Situations. Int J Sport Nutr Exe 21, 451–461. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., McHardy, H., Morton, J.P., Nikolaidis, M.G., Close, G.L., 2015b. Influence of vitamin C and vitamin E on redox signaling: Implications for exercise adaptations. Free Radical Bio Med 84, 65–76. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Moult, P.R., Burniston, J.G., Morton, J.P., Close, G.L., 2015c. Exercise improves mitochondrial and redox-regulated stress responses in the elderly: better late than never! Biogerontology 16, 249–264. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Noble, A., Jimenez-Fernandez, E., Moya, M.-T.V., Guille, M., Husi, H., 2019a. Catalyst-free Click PEGylation reveals substantial mitochondrial ATP synthase sub-unit alpha oxidation before and after fertilisation. Redox Biol 26, 101258. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Sakellariou, G.K., Husi, H., McDonagh, B., 2019b. Proteomic strategies to unravel age-related redox signalling defects in skeletal muscle. Free Radical Bio Med 132, 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Sakellariou, G.K., Murray, S., Waldron, S., Gregson, W., Burniston, J.G., Morton, J.P., Iwanejko, L.A., Close, G.L., 2013. Lifelong endurance training attenuates age-related genotoxic stress in human skeletal muscle. Longev Heal 2, 11. [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N., Sakellariou, G.K., Owens, D.J., Murray, S., Waldron, S., Gregson, W., Fraser, W.D., Burniston, J.G., Iwanejko, L.A., McArdle, A., Morton, J.P., Jackson, M.J., Close, G.L., 2014. Lifelong training preserves some redox-regulated adaptive responses after an acute exercise stimulus in aged human skeletal muscle. Free Radical Bio Med 70, 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.R., Azqueta, A., 2012. DNA repair as a biomarker in human biomonitoring studies; further applications of the comet assay. Mutat. Res.Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 736, 122–129. [CrossRef]

- Consortium, I.H.G.S., Research:, W.I. for B.R., Center for Genome, Lander, E.S., Linton, L.M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M.C., Baldwin, J., Devon, K., Dewar, K., Doyle, M., FitzHugh, W., Funke, R., Gage, D., Harris, K., Heaford, A., Howland, J., Kann, L., Lehoczky, J., LeVine, R., McEwan, P., McKernan, K., Meldrim, J., Mesirov, J.P., Miranda, C., Morris, W., Naylor, J., Raymond, Christina, Rosetti, M., Santos, R., Sheridan, A., Sougnez, C., Stange-Thomann, N., Stojanovic, N., Subramanian, A., Wyman, D., Centre:, T.S., Rogers, J., Sulston, J., Ainscough, R., Beck, S., Bentley, D., Burton, J., Clee, C., Carter, N., Coulson, A., Deadman, R., Deloukas, P., Dunham, A., Dunham, I., Durbin, R., French, L., Grafham, D., Gregory, S., Hubbard, T., Humphray, S., Hunt, A., Jones, M., Lloyd, C., McMurray, A., Matthews, L., Mercer, S., Milne, S., Mullikin, J.C., Mungall, A., Plumb, R., Ross, M., Shownkeen, R., Sims, S., Center, W.U.G.S., Waterston, R.H., Wilson, R.K., Hillier, L.W., McPherson, J.D., Marra, M.A., Mardis, E.R., Fulton, L.A., Chinwalla, A.T., Pepin, K.H., Gish, W.R., Chissoe, S.L., Wendl, M.C., Delehaunty, K.D., Miner, T.L., Delehaunty, A., Kramer, J.B., Cook, L.L., Fulton, R.S., Johnson, D.L., Minx, P.J., Clifton, S.W., Institute:, U.D.J.G., Hawkins, T., Branscomb, E., Predki, P., Richardson, P., Wenning, S., Slezak, T., Doggett, N., Cheng, J.-F., Olsen, A., Lucas, S., Elkin, C., Uberbacher, E., Frazier, M., Center:, B.C. of M.H.G.S., Gibbs, R.A., Muzny, D.M., Scherer, S.E., Bouck, J.B., Sodergren, E.J., Worley, K.C., Rives, C.M., Gorrell, J.H., Metzker, M.L., Naylor, S.L., Kucherlapati, R.S., Nelson, D.L., Weinstock, G.M., Center:, R.G.S., Sakaki, Y., Fujiyama, A., Hattori, M., Yada, T., Toyoda, A., Itoh, T., Kawagoe, C., Watanabe, H., Totoki, Y., Taylor, T., UMR-8030:, G. and C., Weissenbach, J., Heilig, R., Saurin, W., Artiguenave, F., Brottier, P., Bruls, T., Pelletier, E., Robert, C., Wincker, P., Biotechnology:, D. of G.A., Institute of Molecular, Rosenthal, A., Platzer, M., Nyakatura, G., Taudien, S., Rump, A., Center:, G.S., Smith, D.R., Doucette-Stamm, L., Rubenfield, M., Weinstock, K., Lee, H.M., Dubois, J., Center:, B.G.I.G., Yang, H., Yu, J., Wang, J., Huang, G., Gu, J., Biology:, M.S.C., The Institute for Systems, Hood, L., Rowen, L., Madan, A., Qin, S., Center:, S.G.T., Davis, R.W., Federspiel, N.A., Abola, A.P., Proctor, M.J., Technology:, U. of O.A.C. for G., Roe, B.A., Chen, F., Pan, H., Genetics:, M.P.I. for M., Ramser, J., Lehrach, H., Reinhardt, R., Center:, C.S.H.L., Lita Annenberg Hazen Genome, McCombie, W.R., Bastide, M. de la, Dedhia, N., Biotechnology:, G.R.C. for, Blöcker, H., Hornischer, K., Nordsiek, G., Agarwala, R., Aravind, L., Bailey, J.A., Bateman, A., Batzoglou, S., Birney, E., Bork, P., Brown, D.G., Burge, C.B., Cerutti, L., Chen, H.-C., Church, D., Clamp, M., Copley, R.R., Doerks, T., Eddy, S.R., Eichler, E.E., Furey, T.S., Galagan, J., Gilbert, J.G.R., Harmon, C., Hayashizaki, Y., Haussler, D., Hermjakob, H., Hokamp, K., Jang, W., Johnson, L.S., Jones, T.A., Kasif, S., Kaspryzk, A., Kennedy, S., Kent, W.J., Kitts, P., Koonin, E.V., Korf, I., Kulp, D., Lancet, D., Lowe, T.M., McLysaght, A., Mikkelsen, T., Moran, J.V., Mulder, N., Pollara, V.J., Ponting, C.P., Schuler, G., Schultz, J., Slater, G., Smit, A.F.A., Stupka, E., Szustakowki, J., Thierry-Mieg, D., Thierry-Mieg, J., Wagner, L., Wallis, J., Wheeler, R., Williams, A., Wolf, Y.I., Wolfe, K.H., Yang, S.-P., Yeh, R.-F., Health:, S. management: N.H.G.R.I., US National Institutes of, Collins, F., Guyer, M.S., Peterson, J., Felsenfeld, A., Wetterstrand, K.A., Center:, S.H.G., Myers, R.M., Schmutz, J., Dickson, M., Grimwood, J., Cox, D.R., Center:, U. of W.G., Olson, M.V., Kaul, R., Raymond, Christopher, Medicine:, D. of M.B., Keio University School of, Shimizu, N., Kawasaki, K., Minoshima, S., Dallas:, U. of T.S.M.C. at, Evans, G.A., Athanasiou, M., Schultz, R., Energy:, O. of S., US Department of, Patrinos, A., Trust:, T.W., Morgan, M.J., 2001. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921. [CrossRef]

- Crapo, J.D., McCord, J.M., Fridovich, I., 1978. Preparation and assay of superioxide dismutases. Methods Enzym. 53, 382–393. [CrossRef]

- Dagnell, M., Cheng, Q., Rizvi, S.H.M., Pace, P.E., Boivin, B., Winterbourn, C.C., Arnér, E.S.J., 2019. Bicarbonate is essential for protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) oxidation and cellular signaling through EGF-triggered phosphorylation cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 12330–12338. [CrossRef]

- Dagnell, M., Pace, P.E., Cheng, Q., Frijhoff, J., Östman, A., Arnér, E.S.J., Hampton, M.B., Winterbourn, C.C., 2017. Thioredoxin reductase 1 and NADPH directly protect protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B from inactivation during H2O2 exposure. J Biol Chem 292, 14371–14380. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y., Chamberlayne, C.F., Messina, M.S., Chang, C.J., Zare, R.N., You, L., Chilkoti, A., 2023. Interface of biomolecular condensates modulates redox reactions. Chem. [CrossRef]

- D’Autréaux, B., Toledano, M.B., 2007. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 8, 813–824. [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.J.A., Quintanilha, A.T., Brooks, G.A., Packer, L., 1982. Free radicals and tissue damage produced by exercise. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 107, 1198–1205. [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J., 2016. Protein oxidation and peroxidation. Biochem J 473, 805–825. [CrossRef]

- Davison, G.W., 2016. Exercise and Oxidative Damage in Nucleoid DNA Quantified Using Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis: Present and Future Application. Front. Physiol. 7, 249. [CrossRef]

- Day, N.J., Gaffrey, M.J., Qian, W.-J., 2021. Stoichiometric Thiol Redox Proteomics for Quantifying Cellular Responses to Perturbations. Antioxidants 10, 499. [CrossRef]

- Derks, J., Leduc, A., Wallmann, G., Huffman, R.G., Willetts, M., Khan, S., Specht, H., Ralser, M., Demichev, V., Slavov, N., 2022. Increasing the throughput of sensitive proteomics by plexDIA. Nat Biotechnol 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, B.C., Chang, C.J., 2011. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat Chem Biol 7, 504–511. [CrossRef]

- Dillard, C.J., Litov, R.E., Savin, W.M., Dumelin, E.E., Tappel, A.L., 1978. Effects of exercise, vitamin E, and ozone on pulmonary function and lipid peroxidation. J. Appl. Physiol. 45, 927–932. [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T., Holtzclaw, W.D., Cole, R.N., Itoh, K., Wakabayashi, N., Katoh, Y., Yamamoto, M., Talalay, P., 2002. Direct evidence that sulfhydryl groups of Keap1 are the sensors regulating induction of phase 2 enzymes that protect against carcinogens and oxidants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 11908–11913. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J., Lemberg, K.M., Lamprecht, M.R., Skouta, R., Zaitsev, E.M., Gleason, C.E., Patel, D.N., Bauer, A.J., Cantley, A.M., Yang, W.S., Morrison, B., Stockwell, B.R., 2012. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 149, 1060–1072. [CrossRef]

- Dizdaroglu, M., Jaruga, P., Rodriguez, H., 2001. Identification and quantification of 8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxy-adenosine in DNA by liquid chromatography/ mass spectrometry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 30, 774–784. [CrossRef]

- Echtay, K.S., Roussel, D., St-Pierre, J., Jekabsons, M.B., Cadenas, S., Stuart, J.A., Harper, J.A., Roebuck, S.J., Morrison, A., Pickering, S., Clapham, J.C., Brand, M.D., 2002. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature 415, 96–99. [CrossRef]

- Egan, B., Sharples, A.P., 2023. Molecular responses to acute exercise and their relevance for adaptations in skeletal muscle to exercise training. Physiol. Rev. 103, 2057–2170. [CrossRef]

- Egan, B., Zierath, J.R., 2013. Exercise Metabolism and the Molecular Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Adaptation. Cell Metab. 17, 162–184. [CrossRef]

- Eid, M., Barayeu, U., Sulková, K., Aranda-Vallejo, C., Dick, T.P., 2024. Using the heme peroxidase APEX2 to probe intracellular H2O2 flux and diffusion. Nat. Commun. 15, 1239. [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.L., 1959. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys 82, 70–77. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J., 2008. Why model. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation.

- Erdogan, Y.C., Altun, H.Y., Secilmis, M., Ata, B.N., Sevimli, G., Cokluk, Z., Zaki, A.G., Sezen, S., Caglar, T.A., Sevgen, İ., Steinhorn, B., Ai, H., Öztürk, G., Belousov, V.V., Michel, T., Eroglu, E., 2021. Complexities of the chemogenetic toolkit: Differential mDAAO activation by d-amino substrates and subcellular targeting. Free Radical Bio Med 177, 132–142. [CrossRef]

- Erve, T.J. van ‘t, Lih, F.B., Kadiiska, M.B., Deterding, L.J., Eling, T.E., Mason, R.P., 2015. Reinterpreting the best biomarker of oxidative stress: The 8-iso-PGF2α/PGF2α ratio distinguishes chemical from enzymatic lipid peroxidation. Free Radical Bio Med 83, 245–251. [CrossRef]

- Erve, T.J. van ’t, Kadiiska, M.B., London, S.J., Mason, R.P., 2017. Classifying oxidative stress by F2-isoprostane levels across human diseases: A meta-analysis. Redox Biol 12, 582–599. [CrossRef]

- Ezeriņa, D., Takano, Y., Hanaoka, K., Urano, Y., Dick, T.P., 2018. N-Acetyl Cysteine Functions as a Fast-Acting Antioxidant by Triggering Intracellular H2S and Sulfane Sulfur Production. Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 447-459.e4. [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, M., Bollineni, R.C., Hoffmann, R., 2014. Protein carbonylation as a major hallmark of oxidative damage: Update of analytical strategies. Mass Spectrom Rev 33, 79–97. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.B., Fu, L., Jung, Y., Yang, J., Carroll, K.S., 2022. Reaction-based fluorogenic probes for detecting protein cysteine oxidation in living cells. Nat Commun 13, 5522. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-González, G., Pérez-Plasencia, C., 2017. Strategies for the evaluation of DNA damage and repair mechanisms in cancer. Oncol. Lett. 13, 3982–3988. [CrossRef]

- Flohé, L., 2020. Looking Back at the Early Stages of Redox Biology. Antioxidants 9, 1254. [CrossRef]

- Flohé, L., 2013. The fairytale of the GSSG/GSH redox potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 1830, 3139–3142. [CrossRef]

- Floyd, R.A., Watson, J.J., Harris, J., West, M., Wong, P.K., 1986. Formation of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, hydroxyl free radical adduct of DNA in granulocytes exposed to the tumor promoter, tetradeconylphorbolacetate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 137, 841–846. [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J., Augusto, O., Brigelius-Flohe, R., Dennery, P.A., Kalyanaraman, B., Ischiropoulos, H., Mann, G.E., Radi, R., Roberts, L.J., Vina, J., Davies, K.J.A., 2015. Even free radicals should follow some rules: A Guide to free radical research terminology and methodology. Free Radical Bio Med 78, 233–235. [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J., Davies, K.J.A., Ursini, F., 2014. How do nutritional antioxidants really work: Nucleophilic tone and para-hormesis versus free radical scavenging in vivo. Free Radical Bio Med 66, 24–35. [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J., Davies, M.J., Krämer, A.C., Miotto, G., Zaccarin, M., Zhang, H., Ursini, F., 2017. Protein cysteine oxidation in redox signaling: Caveats on sulfenic acid detection and quantification. Arch Biochem Biophys 617, 26–37. [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J., Zhang, H., 2021. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Fridovich, I., 1998. Oxygen Toxicity: A Radical Explanation. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 1203–1209. [CrossRef]

- Fridovich, I., 1989. Superoxide dismutases An adaptation to a paramagnetic gas. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 7761–7764. [CrossRef]

- Fridovich, I., 1978. The Biology of Oxygen Radicals. Science 201, 875–880. [CrossRef]

- Frijhoff, J., Winyard, P.G., Zarkovic, N., Davies, S.S., Stocker, R., Cheng, D., Knight, A.R., Taylor, E.L., Oettrich, J., Ruskovska, T., Gasparovic, A.C., Cuadrado, A., Weber, D., Poulsen, H.E., Grune, T., Schmidt, H.H.H.W., Ghezzi, P., 2015. Clinical Relevance of Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 1144–1170. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Lemus, E., Davies, M.J., 2023. Effect of crowding, compartmentalization and nanodomains on protein modification and redox signaling – current state and future challenges. Free Radical Bio Med 196, 81–92. [CrossRef]

- Ganini, D., Santos, J.H., Bonini, M.G., Mason, R.P., 2018. Switch of Mitochondrial Superoxide Dismutase into a Prooxidant Peroxidase in Manganese-Deficient Cells and Mice. Cell Chem Biol 25, 413-425.e6. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, P.R., 2002. Aconitase: Sensitive target and measure of superoxide. Methods Enzym. 349, 9–23. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, P.R., Nguyen, D.D., White, C.W., 1994. Aconitase is a sensitive and critical target of oxygen poisoning in cultured mammalian cells and in rat lungs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91, 12248–12252. [CrossRef]

- Gatin-Fraudet, B., Ottenwelter, R., Saux, T.L., Norsikian, S., Pucher, M., Lombès, T., Baron, A., Durand, P., Doisneau, G., Bourdreux, Y., Iorga, B.I., Erard, M., Jullien, L., Guianvarc’h, D., Urban, D., Vauzeilles, B., 2021. Evaluation of borinic acids as new, fast hydrogen peroxide–responsive triggers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2107503118. [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, C.D., Zisimopoulos, D., Argyropoulou, V., Kalaitzopoulou, E., Ioannou, P.V., Salachas, G., Grune, T., 2018. Protein carbonyl determination by a rhodamine B hydrazide-based fluorometric assay. Redox Biol 17, 236–245. [CrossRef]

- Giustarini, D., Dalle-Donne, I., Colombo, R., Milzani, A., Rossi, R., 2003. An improved HPLC measurement for GSH and GSSG in human blood. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 35, 1365–1372. [CrossRef]

- Giustarini, D., Milzani, A., Dalle-Donne, I., Rossi, R., 2023. How to Increase Cellular Glutathione. Antioxidants 12, 1094. [CrossRef]

- Glover, M.R., Davies, M.J., Fuentes-Lemus, E., 2023. Oxidation of the active site cysteine residue of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase to the hyper-oxidized sulfonic acid form is favored under crowded conditions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.-M., Chandler, J.D., Jones, D.P., 2015. The cysteine proteome. Free Radical Bio Med 84, 227–245. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera, M., Borrás, C., Pallardó, F.V., Sastre, J., Ji, L.L., Viña, J., 2005. Decreasing xanthine oxidase-mediated oxidative stress prevents useful cellular adaptations to exercise in rats. J. Physiol. 567, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera, M.C., Carretero, A., Millan-Domingo, F., Garcia-Dominguez, E., Correas, A.G., Olaso-Gonzalez, G., Viña, J., 2021. Redox-related biomarkers in physical exercise. Redox Biol 42, 101956. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera, M.-C., Domenech, E., Romagnoli, M., Arduini, A., Borras, C., Pallardo, F.V., Sastre, J., Viña, J., 2008. Oral administration of vitamin C decreases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and hampers training-induced adaptations in endurance performance. Am J Clin Nutrition 87, 142–149. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Cabrera, M.-C., Pallardó, F.V., Sastre, J., Viña, J., García-del-Moral, L., 2003. Allopurinol and Markers of Muscle Damage Among Participants in the Tour de France. JAMA 289, 2503–2504. [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, R.L.S., Quinlan, C.L., Perevoshchikova, I.V., Hey-Mogensen, M., Brand, M.D., 2015. Sites of Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide Production by Muscle Mitochondria Assessed ex Vivo under Conditions Mimicking Rest and Exercise*. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 209–227. [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C., Halliwell, B., 2018. Mini-Review: Oxidative stress, redox stress or redox success? Biochem Bioph Res Co 502, 183–186. [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C., Halliwell, B., 2010. Antioxidants: Molecules, medicines, and myths. Biochem Bioph Res Co 393, 561–564. [CrossRef]

- GUTTERIDGE, J.M.C., HALLIWELL, B., 2000. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in the Year 2000: A Historical Look to the Future. Ann Ny Acad Sci 899, 136–147. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., 2023. Understanding mechanisms of antioxidant action in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., 2009. The wanderings of a free radical. Free Radical Bio Med 46, 531–542. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., 2008. Are polyphenols antioxidants or pro-oxidants? What do we learn from cell culture and in vivo studies? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 476, 107–112. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., 2007. Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Biochemical Society Transactions.

- Halliwell, B., 2006. Oxidative stress and cancer: have we moved forward? Biochem J 401, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., 1987. Oxidants and human disease: some new concepts1. FASEB J. 1, 358–364. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., Adhikary, A., Dingfelder, M., Dizdaroglu, M., 2021. Hydroxyl radical is a significant player in oxidative DNA damage in vivo. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 8355–8360. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., Gutteridge, J., 2015. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine.

- Halliwell, B., Lee, C.Y.J., 2010. Using Isoprostanes as Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress: Some Rarely Considered Issues. Antioxid Redox Sign 13, 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., Whiteman, M., 2004. Measuring reactive species and oxidative damage in vivo and in cell culture: how should you do it and what do the results mean? Brit J Pharmacol 142, 231–255. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., Zhao, K., Whiteman, M., 2000. The gastrointestinal tract: A major site of antioxidant action? Free Radic. Res. 33, 819–830. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.E., Winther, J.R., 2009. An introduction to methods for analyzing thiols and disulfides: Reactions, reagents, and practical considerations. Anal Biochem 394, 147–158. [CrossRef]

- Hausladen, A., Fridovich, I., 1994. Superoxide and peroxynitrite inactivate aconitases, but nitric oxide does not. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 29405–29408. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.L., Davies, M.J., 2019. Detection, identification, and quantification of oxidative protein modifications. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 19683–19708. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.L., Morgan, P.E., Davies, M.J., 2009. Quantification of protein modification by oxidants. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 46, 965–988. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D., Dinkova-Kostova, A.T., Tew, K.D., 2020. Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell 38, 167–197. [CrossRef]

- Held, J.M., 2020. Redox Systems Biology: Harnessing the Sentinels of the Cysteine Redoxome. Antioxid Redox Sign 32, 659–676. [CrossRef]

- Held, J.M., Danielson, S.R., Behring, J.B., Atsriku, C., Britton, D.J., Puckett, R.L., Schilling, B., Campisi, J., Benz, C.C., Gibson, B.W., 2010. Targeted Quantitation of Site-Specific Cysteine Oxidation in Endogenous Proteins Using a Differential Alkylation and Multiple Reaction Monitoring Mass Spectrometry Approach. Mol Cell Proteomics 9, 1400–1410. [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Olguin, C., Meneses-Valdes, R., Jensen, T.E., 2020. Compartmentalized muscle redox signals controlling exercise metabolism – Current state, future challenges. Redox Biol 35, 101473. [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Olguin, C., Meneses-Valdes, R., Kritsiligkou, P., Fuentes-Lemus, E., 2023. From workout to molecular switches: How does skeletal muscle produce, sense, and transduce subcellular redox signals? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 209, 355–365. [CrossRef]

- Hie, B.L., Shanker, V.R., Xu, D., Bruun, T.U.J., Weidenbacher, P.A., Tang, S., Wu, W., Pak, J.E., Kim, P.S., 2023. Efficient evolution of human antibodies from general protein language models. Nat Biotechnol 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Holmström, K.M., Finkel, T., 2014. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 15, 411–421. [CrossRef]

- Hou, C., Hsieh, C.-J., Li, S., Lee, H., Graham, T.J., Xu, K., Weng, C.-C., Doot, R.K., Chu, W., Chakraborty, S.K., Dugan, L.L., Mintun, M.A., Mach, R.H., 2018. Development of a Positron Emission Tomography Radiotracer for Imaging Elevated Levels of Superoxide in Neuroinflammation. Acs Chem Neurosci 9, 578–586. [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.K., Sikes, H.D., 2014. Quantifying intracellular hydrogen peroxide perturbations in terms of concentration. Redox Biol 2, 955–962. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Co, H.K., Lee, Y., Wu, C., Chen, S., 2021. Multistability maintains redox homeostasis in human cells. Mol. Syst. Biol. 17, e10480. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.J., Spelke, D.P., Xu, Z., Kang, C.-C., Schaffer, D.V., Herr, A.E., 2014. Single-cell western blotting. Nat Methods 11, 749–755. [CrossRef]

- Illés, E., Mizrahi, A., Marks, V., Meyerstein, D., 2019. Carbonate-radical-anions, and not hydroxyl radicals, are the products of the Fenton reaction in neutral solutions containing bicarbonate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 131, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Imlay, J.A., 2013. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat Rev Microbiol 11, 443–454. [CrossRef]

- Imlay, J.A., 2008. Cellular Defenses against Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 755–776. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, H.S., Jandl, J.H., 1966. Effects of Sulfhydryl Inhibition on Red Blood Cells III. GLUTATHIONE IN THE REGULATION OF THE HEXOSE MONOPHOSPHATE PATHWAY. J Biol Chem 241, 4243–4250. [CrossRef]

- Janes, K.A., 2015. An analysis of critical factors for quantitative immunoblotting. Sci Signal 8, rs2. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Stockwell, B.R., Conrad, M., 2021. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 22, 266–282. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P., 2006. Redefining Oxidative Stress. Antioxid Redox Sign 8, 1865–1879. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P., Sies, H., 2015. The Redox Code. Antioxid Redox Sign 23, 734–746. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.C., Perry, C.G.R., Cheng, A.J., 2021. Promoting a pro-oxidant state in skeletal muscle: Potential dietary, environmental, and exercise interventions for enhancing endurance-training adaptations. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 176, 189–202. [CrossRef]

- Kagan, V.E., Mao, G., Qu, F., Angeli, J.P.F., Doll, S., Croix, C.S., Dar, H.H., Liu, B., Tyurin, V.A., Ritov, V.B., Kapralov, A.A., Amoscato, A.A., Jiang, J., Anthonymuthu, T., Mohammadyani, D., Yang, Q., Proneth, B., Klein-Seetharaman, J., Watkins, S., Bahar, I., Greenberger, J., Mallampalli, R.K., Stockwell, B.R., Tyurina, Y.Y., Conrad, M., Bayır, H., 2017. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol 13, 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, B., 2022. NAC, NAC, Knockin’ on Heaven’s door: Interpreting the mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine in tumor and immune cells. Redox Biol. 57, 102497. [CrossRef]

- Karplus, P.A., 2015. A primer on peroxiredoxin biochemistry. Free Radical Bio Med 80, 183–190. [CrossRef]

- Keeley, T.P., Mann, G.E., 2019. Defining Physiological Normoxia for Improved Translation of Cell Physiology to Animal Models and Humans. Physiol. Rev. 99, 161–234. [CrossRef]

- Kerins, M.J., Milligan, J., Wohlschlegel, J.A., Ooi, A., 2018. Fumarate hydratase inactivation in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer is synthetic lethal with ferroptosis induction. Cancer Sci. 109, 2757–2766. [CrossRef]

- Kettle, A.J., Ashby, L.V., Winterbourn, C.C., Dickerhof, N., 2023. Superoxide: The enigmatic chemical chameleon in neutrophil biology. Immunol. Rev. 314, 181–196. [CrossRef]

- Khassaf, M., McArdle, A., Esanu, C., Vasilaki, A., McArdle, F., Griffiths, R.D., Brodie, D.A., Jackson, M.J., 2003. Effect of Vitamin C Supplements on Antioxidant Defence and Stress Proteins in Human Lymphocytes and Skeletal Muscle. J. Physiol. 549, 645–652. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Ha, S., Lee, H.Y., Lee, K., 2015. ROSics: Chemistry and proteomics of cysteine modifications in redox biology. Mass Spectrom Rev 34, 184–208. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, N., Galligan, J.J., 2023. A global view of the human post-translational modification landscape. Biochem. J. 480, 1241–1265. [CrossRef]

- Kitano, H., 2002. Computational systems biology. Nature 420, 206–210. [CrossRef]

- Kono, Y., Fridovich, I., 1982. Superoxide radical inhibits catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 5751–5754. [CrossRef]

- Koppenol, W.H., 2022. Ferryl for real. The Fenton reaction near neutral pH. Dalton Trans. 51, 17496–17502. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, P.A., Duan, J., Gaffrey, M.J., Shukla, A.K., Wang, L., Bammler, T.K., Qian, W.-J., Marcinek, D.J., 2018. Fatiguing contractions increase protein S-glutathionylation occupancy in mouse skeletal muscle. Redox Biol. 17, 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Kritsiligkou, P., Bosch, K., Shen, T.K., Meurer, M., Knop, M., Dick, T.P., 2023. Proteome-wide tagging with an H 2 O 2 biosensor reveals highly localized and dynamic redox microenvironments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2314043120. [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, J.R., 1997. A Tutorial on the Diffusibility and Reactivity of Free Nitric Oxide. Nitric Oxide 1, 18–30. [CrossRef]

- Langford, T.F., Deen, W.M., Sikes, H.D., 2018. A mathematical analysis of Prx2-STAT3 disulfide exchange rate constants for a bimolecular reaction mechanism. Free Radical Bio Med 120, 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, E.L., Karstoft, K., Poulsen, H.E., 2022. Exercise and RNA oxidation, in: Cobley, J.N., Davison, G.W. (Eds.), Oxidative Eustress in Exercise Physiology.

- Larsen, E.L., Weimann, A., Poulsen, H.E., 2019. Interventions targeted at oxidatively generated modifications of nucleic acids focused on urine and plasma markers. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 145, 256–283. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Chang, G., 2019. Quantitative display of the redox status of proteins with maleimide-polyethylene glycol tagging. Electrophoresis 40, 491–498. [CrossRef]

- Leeuwen, L.A.G. van, Hinchy, E.C., Murphy, M.P., Robb, E.L., Cochemé, H.M., 2017. Click-PEGylation – A mobility shift approach to assess the redox state of cysteines in candidate proteins. Free Radical Bio Med 108, 374–382. [CrossRef]

- Leichert, L.I., Gehrke, F., Gudiseva, H.V., Blackwell, T., Ilbert, M., Walker, A.K., Strahler, J.R., Andrews, P.C., Jakob, U., 2008. Quantifying changes in the thiol redox proteome upon oxidative stress in vivo. Proc National Acad Sci 105, 8197–8202. [CrossRef]

- Lennicke, C., Cochemé, H.M., 2021. Redox metabolism: ROS as specific molecular regulators of cell signaling and function. Mol Cell 81, 3691–3707. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Sancar, A., 2020. Methodologies for detecting environmentally induced DNA damage and repair. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 61, 664–679. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Gluth, A., Zhang, T., Qian, W., 2023. Thiol redox proteomics: Characterization of thiol-based post-translational modifications. Proteomics e2200194. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.H., Dedon, P.C., Deen, W.M., 2008. Kinetic Analysis of Intracellular Concentrations of Reactive Nitrogen Species. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 2134–2147. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.B., Huang, B.K., Deen, W.M., Sikes, H.D., 2015. Analysis of the lifetime and spatial localization of hydrogen peroxide generated in the cytosol using a reduced kinetic model. Free Radical Bio Med 89, 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.B., Langford, T.F., Huang, B.K., Deen, W.M., Sikes, H.D., 2016. A reaction-diffusion model of cytosolic hydrogen peroxide. Free Radical Bio Med 90, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Liochev, S.I., Fridovich, I., 2002. Copper, Zinc Superoxide Dismutase and H2O2 EFFECTS OF BICARBONATE ON INACTIVATION AND OXIDATIONS OF NADPH AND URATE, AND ON CONSUMPTION of H2O2 *. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34674–34678. [CrossRef]

- Lisi, V., Moulton, C., Fantini, C., Grazioli, E., Guidotti, F., Sgrò, P., Dimauro, I., Capranica, L., Parisi, A., Luigi, L.D., Caporossi, D., 2023. Steady-state redox status in circulating extracellular vesicles: A proof-of-principle study on the role of fitness level and short-term aerobic training in healthy young males. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 204, 266–275. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Herr, A.E., 2023. DropBlot: single-cell western blotting of chemically fixed cancer cells. [CrossRef]

- Low, F.M., Hampton, M.B., Peskin, A.V., Winterbourn, C.C., 2006. Peroxiredoxin 2 functions as a noncatalytic scavenger of low-level hydrogen peroxide in the erythrocyte. Blood 109, 2611–2617. [CrossRef]

- Low, F.M., Hampton, M.B., Winterbourn, C.C., 2008. Peroxiredoxin 2 and Peroxide Metabolism in the Erythrocyte. Antioxid Redox Sign 10, 1621–1630. [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J., Rauh-Pfeiffer, A., Yu, Y.M., Lu, X.-M., Zurakowski, D., Tompkins, R.G., Ajami, A.M., Young, V.R., Castillo, L., 2000. Blood glutathione synthesis rates in healthy adults receiving a sulfur amino acid-free diet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 5071–5076. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.I., Munch, H.K., Moore, T., Francis, M.B., 2015. One-step site-specific modification of native proteins with 2-pyridinecarboxyaldehydes. Nat Chem Biol 11, 326–331. [CrossRef]

- MacMillan-Crow, L.A., Crow, J.P., Kerby, J.D., Beckman, J.S., Thompson, J.A., 1996. Nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in chronic rejection of human renal allografts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93, 11853–11858. [CrossRef]

- Madani, A., Krause, B., Greene, E.R., Subramanian, S., Mohr, B.P., Holton, J.M., Olmos, J.L., Xiong, C., Sun, Z.Z., Socher, R., Fraser, J.S., Naik, N., 2023. Large language models generate functional protein sequences across diverse families. Nat Biotechnol 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Madian, A.G., Diaz-Maldonado, N., Gao, Q., Regnier, F.E., 2011. Oxidative stress induced carbonylation in human plasma. J Proteomics 74, 2395–2416. [CrossRef]

- Madian, A.G., Regnier, F.E., 2010. Profiling Carbonylated Proteins in Human Plasma. J Proteome Res 9, 1330–1343. [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, R.J., 2021. An update on methods and approaches for interrogating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Redox Biol 45, 102044. [CrossRef]

- Makmura, L., Hamann, M., Areopagita, A., Furuta, S., Muoz, A., Momand, J., 2001. Development of a Sensitive Assay to Detect Reversibly Oxidized Protein Cysteine Sulfhydryl Groups. Antioxid Redox Sign 3, 1105–1118. [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z.A., Cobley, J.N., Morton, J.P., Close, G.L., Edwards, B.J., Koch, L.G., Britton, S.L., Burniston, J.G., 2013. Label-Free LC-MS Profiling of Skeletal Muscle Reveals Heart-Type Fatty Acid Binding Protein as a Candidate Biomarker of Aerobic Capacity. Proteomes 1, 290–308. [CrossRef]

- Manford, A.G., Mena, E.L., Shih, K.Y., Gee, C.L., McMinimy, R., Martínez-González, B., Sherriff, R., Lew, B., Zoltek, M., Rodríguez-Pérez, F., Woldesenbet, M., Kuriyan, J., Rape, M., 2021. Structural basis and regulation of the reductive stress response. Cell. [CrossRef]

- Manford, A.G., Rodríguez-Pérez, F., Shih, K.Y., Shi, Z., Berdan, C.A., Choe, M., Titov, D.V., Nomura, D.K., Rape, M., 2020. A Cellular Mechanism to Detect and Alleviate Reductive Stress. Cell 183, 46-61.e21. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V., 2023. Personalized redox biology: Designs and concepts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 208, 112–125. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V., Chatzinikolaou, P.N., Chatzinikolaou, A.N., Paschalis, V., Theodorou, A.A., Vrabas, I.S., Kyparos, A., Nikolaidis, M.G., 2022. The redox signal: A physiological perspective. IUBMB Life 74, 29–40. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V., Cobley, J.N., Paschalis, V., Veskoukis, A.S., Theodorou, A.A., Kyparos, A., Nikolaidis, M.G., 2016. Going retro: Oxidative stress biomarkers in modern redox biology. Free Radical Bio Med 98, 2–12. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, Nikos V., Cobley, J.N., Paschalis, V., Veskoukis, A.S., Theodorou, A.A., Kyparos, A., Nikolaidis, M.G., 2016. Principles for integrating reactive species into in vivo biological processes: Examples from exercise physiology. Cell Signal 28, 256–271. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V., Kyparos, A., Paschalis, V., Theodorou, A.A., Panayiotou, G., Zafeiridis, A., Dipla, K., Nikolaidis, M.G., Vrabas, I.S., 2014. Reductive stress after exercise: The issue of redox individuality. Redox Biol. 2, 520–528. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V., Nastos, G.G., Vasileiadou, O., Chatzinikolaou, P.N., Theodorou, A.A., Paschalis, V., Vrabas, I.S., Kyparos, A., Fatouros, I.G., Nikolaidis, M.G., 2023. Inter-individual variability in redox and performance responses after antioxidant supplementation: A randomized double blind crossover study. Acta Physiol. 238, e14017. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V., Paschalis, V., Theodorou, A.A., Kyparos, A., Nikolaidis, M.G., 2020. Redox basis of exercise physiology. Redox Biol 35, 101499. [CrossRef]

- Margaritelis, N.V., Theodorou, A.A., Paschalis, V., Veskoukis, A.S., Dipla, K., Zafeiridis, A., Panayiotou, G., Vrabas, I.S., Kyparos, A., Nikolaidis, M.G., 2018. Adaptations to endurance training depend on exercise-induced oxidative stress: exploiting redox interindividual variability. Acta Physiol. 222, e12898. [CrossRef]

- Marinho, H.S., Real, C., Cyrne, L., Soares, H., Antunes, F., 2014. Hydrogen peroxide sensing, signaling and regulation of transcription factors. Redox Biol 2, 535–562. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Baniandres, P., Lan, W.-H., Board, S., Romero-Ruiz, M., Garcia-Manyes, S., Qing, Y., Bayley, H., 2023. Enzyme-less nanopore detection of post-translational modifications within long polypeptides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Marx, V., 2013. Finding the right antibody for the job. Nat Methods 10, 703–707. [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.P., Ganini, D., 2019. Immuno-spin trapping of macromolecules free radicals in vitro and in vivo – One stop shopping for free radical detection. Free Radical Bio Med 131, 318–331. [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A., Trewin, A.J., Parker, L., Wadley, G.D., 2020. Antioxidant supplements and endurance exercise: Current evidence and mechanistic insights. Redox Biol 35, 101471. [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.M., Fridovich, I., 1969. Superoxide Dismutase AN ENZYMIC FUNCTION FOR ERYTHROCUPREIN (HEMOCUPREIN). J Biol Chem 244, 6049–6055. [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.M., Fridovich, I., 1968. The Reduction of Cytochrome c by Milk Xanthine Oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 5753–5760. [CrossRef]

- Melo, T., Montero-Bullón, J.-F., Domingues, P., Domingues, M.R., 2019. Discovery of bioactive nitrated lipids and nitro-lipid-protein adducts using mass spectrometry-based approaches. Redox Biol. 23, 101106. [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.D., Venditti, P., 2020. Evolution of the Knowledge of Free Radicals and Other Oxidants. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 9829176. [CrossRef]

- MICHAILIDIS, Y., JAMURTAS, A.Z., NIKOLAIDIS, M.G., FATOUROS, I.G., KOUTEDAKIS, Y., PAPASSOTIRIOU, I., KOURETAS, D., 2007. Sampling Time is Crucial for Measurement of Aerobic Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 39, 1107–1113. [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.L., Nogueira, M.S., Gao, B., Sanchez, S.C., Amin, W., Thomas, S., Oger, C., Galano, J.-M., Murff, H.J., Yang, G., Durand, T., 2024. Identification of novel F2-isoprostane metabolites by specific UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Redox Biol. 70, 103020. [CrossRef]

- Milo, R., Phillips, R., 2006. Cell Biology by the numbers, 2nd Edition. ed. Garland Science, New York.

- Misra, H.P., 1974. Generation of Superoxide Free Radical during the Autoxidation of Thiols. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 2151–2155. [CrossRef]

- Misra, H.P., Fridovich, I., 1972. The Role of Superoxide Anion in the Autoxidation of Epinephrine and a Simple Assay for Superoxide Dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 3170–3175. [CrossRef]

- Mogilner, A., Wollman, R., Marshall, W.F., 2006. Quantitative Modeling in Cell Biology: What Is It Good for? Dev. Cell 11, 279–287. [CrossRef]

- Moi, P., Chan, K., Asunis, I., Cao, A., Kan, Y.W., 1994. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 91, 9926–9930. [CrossRef]

- Muggeridge, D.J., Crabtree, D.R., Tuncay, A., Megson, I.L., Davison, G., Cobley, J.N., 2022. Exercise decreases PP2A-specific reversible thiol oxidation in human erythrocytes: Implications for redox biomarkers. Free Radical Bio Med 182, 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P., 2014. Antioxidants as therapies: can we improve on nature? Free Radical Bio Med 66, 20–23. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P., 2009. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J 417, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P., Bayir, H., Belousov, V., Chang, C.J., Davies, K.J.A., Davies, M.J., Dick, T.P., Finkel, T., Forman, H.J., Janssen-Heininger, Y., Gems, D., Kagan, V.E., Kalyanaraman, B., Larsson, N.-G., Milne, G.L., Nyström, T., Poulsen, H.E., Radi, R., Remmen, H.V., Schumacker, P.T., Thornalley, P.J., Toyokuni, S., Winterbourn, C.C., Yin, H., Halliwell, B., 2022. Guidelines for measuring reactive oxygen species and oxidative damage in cells and in vivo. Nat Metabolism 4, 651–662. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P., Hartley, R.C., 2018. Mitochondria as a therapeutic target for common pathologies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17, 865–886. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P., Holmgren, A., Larsson, N.-G., Halliwell, B., Chang, C.J., Kalyanaraman, B., Rhee, S.G., Thornalley, P.J., Partridge, L., Gems, D., Nyström, T., Belousov, V., Schumacker, P.T., Winterbourn, C.C., 2011. Unraveling the Biological Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell Metab 13, 361–366. [CrossRef]

- Neuman, E.W., 1934. Potassium Superoxide and the Three-Electron Bond. J. Chem. Phys. 2, 31–33. [CrossRef]

- Niki, E., 2009. Lipid peroxidation: Physiological levels and dual biological effects. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 469–484. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, M., Margaritelis, N., Matsakas, A., 2020. Quantitative Redox Biology of Exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 41, 633–645. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, M.G., Kerksick, C.M., Lamprecht, M., McAnulty, S.R., 2012. Does Vitamin C and E Supplementation Impair the Favorable Adaptations of Regular Exercise? Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 707941. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, M.G., Kyparos, A., Vrabas, I.S., 2011. F2-isoprostane formation, measurement and interpretation: The role of exercise. Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, M.G., Margaritelis, N.V., 2023. Free radicals and antioxidants: appealing to magic. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, M.G., Margaritelis, N.V., 2018. Same Redox Evidence But Different Physiological “Stories”: The Rashomon Effect in Biology. Bioessays 40, 1800041. [CrossRef]

- Noble, A., Guille, M., Cobley, J.N., 2021. ALISA: A microplate assay to measure protein thiol redox state. Free Radical Bio Med 174, 272–280. [CrossRef]

- Ogilby, P.R., 2010. Singlet oxygen : there is indeed something new under the sun. Chem Soc Rev 39, 3181–3209. [CrossRef]

- Orrico, F., Möller, M.N., Cassina, A., Denicola, A., Thomson, L., 2018. Kinetic and stoichiometric constraints determine the pathway of H2O2 consumption by red blood cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 121, 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.L., Berry, S.R., Traustadóttir, T., 2021a. Effects of exercise training on redox stress resilience in young and older adults. Adv. Redox Res. 2, 100007. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.L., Traustadóttir, T., 2020. Aerobic exercise training partially reverses the impairment of Nrf2 activation in older humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 160, 418–432. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.L., Valencia, A.P., Marcinek, D.J., Traustadóttir, T., 2021b. High intensity muscle stimulation activates a systemic Nrf2-mediated redox stress response. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 172, 82–89. [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.J., Twist, C., Cobley, J.N., Howatson, G., Close, G.L., 2018. Exercise-induced muscle damage: What is it, what causes it and what are the nutritional solutions? Eur J Sport Sci 19, 1–15. [CrossRef]