1. Introduction

The ability of a material to react to external stimuli and alter its shape and functionality is a crucial characteristic of so-called ‘smart (bio)materials. In response to environmental cues like changes in pH, temperature, redox potential, or ionic strength, these structures can adapt their behavior or trigger desired reactions. This is an exciting property for novel engineering solutions in biotechnology and medicine [

1]. One example of such a material that has gained more and more attention since its introduction in the late 1960s is thermoresponsive polymers [

2,

3]. Upon reaching a specific temperature, thermoresponsive polymers dispersed in a solvent change their conformation from an expanded, well-soluble state to a collapsed, poorly soluble globular state over a narrow temperature range [

4]. This process is reversible. A thermoresponsive polymer can exhibit a lower (LCST) or upper critical solution temperature (UCST) and thereby decrease or increase its solvation, respectively, when the temperature is raised past its critical solution temperature (CST). The CST is concentration- and solvent-dependent.

What makes thermoresponsive polymers especially interesting for researchers is that adaptive behavior adds multifunctionality, which makes thermoresponsive polymers promising for applications in, e.g., tissue engineering, drug delivery, or catalysis [

5,

6,

7]. The most commonly investigated thermoresponsive polymer with applications in biotechnology is poly(

N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PNiPAm) [

8,

9,

10]. It has, e.g., been used as a surface modification to create planar substrates for cultivating cell sheets, first demonstrated by Okano et al. in 1993 [

11]. This success has sparked extensive research on various medical applications [

12,

13,

14,

15].

The exact CST or temperature range at which the transition happens depends on the polymer but also the solvent environment. Solvent polarity or changes to pH or ion concentration alter the CST of thermoresponsive polymers. For instance, intermolecular interactions in bulk deuterium oxide (D

2O) are stronger compared to water. D

2O molecules bind more strongly to polar groups of, e.g., polymer chains and the resulting entropic penalty of exposed non-polar segments to the polar solvent molecules is higher [

16]. This is crucial because some essential analytical techniques rely on D

2O as a measurement solvent. Prominent examples are nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), small-angle neutron scattering (SANS), and neutron reflectometry (NR), which are powerful techniques for investigating polymer structures in bulk and at interfaces. However, applications are designed for biological fluids (H

2O), where the polymer conformation and energetics could differ. A direct comparison of measurements with these techniques to complementary measurements by other techniques in normal water could be misleading.

Further, biological fluids contain high concentrations of Hofmeister series salts. The Hofmeister series describes salts according to their ability to affect the stability of proteins or polymers via their effect on the inter-water bonding network [

17,

18] and polar bonds of the polymer [

19,

20]. Historically, these species were often described as ‘structure-making’ or ‘structure-breaking’ compounds regarding their effect on bulk water. Regarding the stability of proteins, kosmotropes are known to promote and stabilize their defined folded conformation. Chaotropes, on the other hand, lead to the denaturation of proteins [

17,

21]. More recent findings, notably contributed by the Cremer group, suggest that the actual mechanism behind these effects is connected to the relative ion polarizabilities and the specific ion interactions directly with the macromolecular solutes and their immediately adjacent hydration shells [

19,

20]. Moreover, the intermolecular interactions of H

2O or D

2O molecules differ when such solutes are added [

22,

23,

24]. The influence of Hofmeister ions on the CST can be huge and vary depending on the polymer [

25], which agrees with the results of Cremer et al.

Despite the use of D

2O instead of H

2O in crucial analytical techniques used to study (bio)polymer conformations and their thermoresponsive properties, there is a lack of studies on the differences in the thermal solvation transition between them. Additionally, given the importance of the effect of Hofmeister ions on the solvent structure for polymer stability, there is a lack of data on how they affect structure in D

2O. This is a severe deficiency of the current literature, given that much of the characterization of polymer properties is performed in D

2O and not H

2O and, further, that these investigations are performed in pure D

2O without the presence of Hofmeister series ions. Still, such measurements are compared directly to other results obtained under physiological conditions in H

2O to draw conclusions for designing applications. Additionally, a disproportionate amount of research on the thermal transition of polymers in water was performed on PNiPAm. Other popular thermoresponsive polymers, e.g., poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline) (PiPOx), are less thoroughly investigated with salts co-solved during measurements. PiPOx is a promising material for biomedical applications because PiPOx exhibits better biocompatibility than PNiPAm, reacts more strongly to environmental changes, and has a tunable CST closer to human body temperature [

26,

27].

Published research on thermoresponsive polymers like PNiPAm or PiPOx primarily covers specific cases, e.g., investigating these polymers crosslinked in hydrogels, grafted to surfaces, or as part of more complex copolymers.[

28,

29,

30] Our study tries to fill the gap with data connecting the CST of PNiPAm and PiPOx to solvent and co-solute properties that include D

2O. Two complementary experimental techniques proper for both D

2O and H

2O were applied to investigate the CST: dynamic light scattering (DLS) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). DLS and DSC are two of the most frequently used techniques for determining critical solution temperatures. These techniques provide complementary information about the investigated systems, as they measure the CST in fundamentally different ways. By including data collected with both methods in this work, we aim to paint a more complete picture of the transition of thermoresponsive polymers than available in the existing literature [

25,

31,

32].

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Polymer Concentration on the CST in H2O and D2O

CST values were extracted from DLS and DSC measurements for PNiPAm and PiPOx of 21000 g mol

-1, respectively. DLS determines particle size from fluctuations in the scattered light intensity. The total scattered light intensity increases when aggregates are formed, which can also be measured sensitively with a DLS instrument. Once the CST has been reached, aggregates are formed. They sediment due to gravity and move in the bulk medium due to thermal convection in addition to Brownian motion. As a result, the recorded light intensity does not monotonously increase as aggregation sets in; it is susceptible to fluctuations depending on the movement of large scattering objects within the sampling volume of the DLS. In this study, DLS-derived CST values were, therefore, extracted from the initial increase of the scattering intensity as a function of temperature. This is the temperature at which the collapsing polymer coils start aggregating in response to their thermally induced reduced solvation. In contrast, DSC measures the energetics of the coil-globule transition. We recorded the temperature at the transition peak maximum as the CST. Although this point does not represent the start of the transition, it facilitates comparing the stability of polymers, as was shown in other studies [

33,

34].

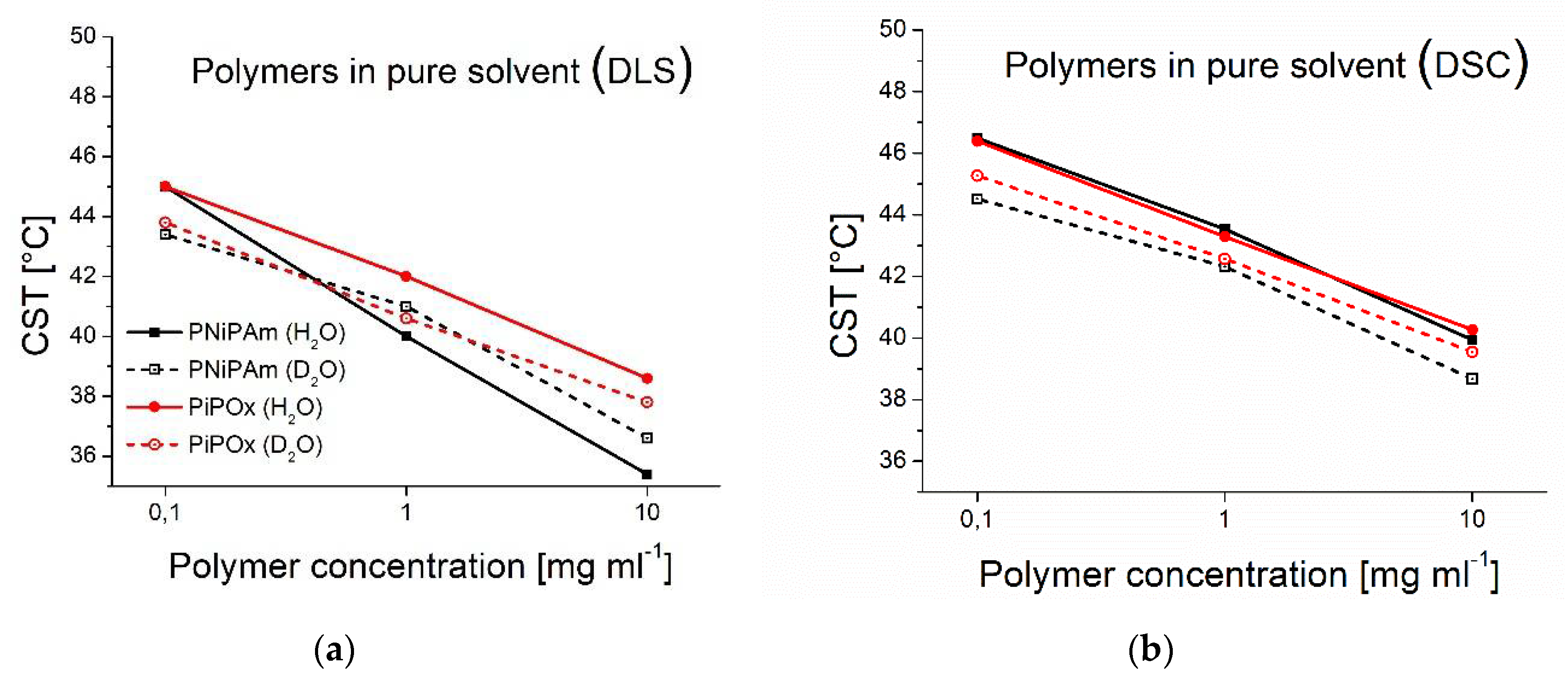

In

Figure 1, CST values of differently concentrated PNiPAm and PiPOx samples in H

2O and D

2O are shown (see

Table S1 of the supplementary material for exact values). Results from DSC and DLS experiments with PiPOx correspond well, as CST values follow the same trend of decreased temperatures with increasing polymer concentration. The CST determined by DLS is approximately 4 °C lower than for DSC for low (0.1 mg ml

-1) polymer concentrations, which decreases to 1 °C for high (10 mg ml

-1) concentrations, with our choices for selecting them. These values are close to the temperature difference between the peak onsets and peak maxima of the DSC thermograms. These also vary with concentration and are approximately 4 °C lower at 0.1 mg ml

-1 and 1 °C lower at 10 mg ml

-1 (see

Table S2). The CST decreases monotonously and quasi-linearly in the investigated concentration regime in a semi-log plot. The CST changes as a function of concentration measured by DSC are very similar in the case of all polymer and solvent combinations. The CST drops approximately 5 °C from 0.1 to 10 mg ml

-1. Measured by DLS, the CST drops with 5 °C for PiPOx but slightly more steeply for PNiPAm with close to 10 °C in H

2O and close to 7 °C in D

2O, in the same concentration range. A decrease of approximately 3 °C for an increase in polymer concentration from 0.1 mg ml

-1 to 1 mg ml

-1 was reported by Uyama and Kobayashi in 1992 for PiPOx of comparable molecular weight (

) [

35]. Our results are in the same range as their observations, which they made visually, and are therefore not as precise. Results reported by Pamies et al. show a CST shift of PNiPAm of about 4 °C between 0.1 and 1 mg ml

-1, which corresponds well to our findings, considering they measured PNiPAm at lower molecular weight (

) [

36].

Comparing H

2O and D

2O, the CSTs determined by DSC are lower in D

2O for both PiPOx and PNiPAm, with, on average, 1.0 °C and 1.5 °C, respectively. The dependence of the difference as a function of concentration is moderate, with 0.72 °C difference for the samples 10 mg ml

-1 and 1 mg ml

-1 and 1.12 °C in the case of the 0.1 mg ml

-1 sample. PiPOx shows a similar dependence on solvent measured by DLS as observed by DSC. The CST measured by DLS is approximately 1.0 °C lower in D

2O. In contrast, PNiPAm has a higher CST in D

2O than in H

2O measured by DLS at higher concentrations. Only at 0.1 mg ml

-1 is a higher CST in H

2O observed. Other studies have reported higher CST values for PNiPAm in D

2O as well, although the measured systems differ from ours: Xiaohui Wang and Chi Wu have measured a 1.5 °C upwards shift of the CST in D

2O for huge PNiPAm molecules in highly dilute dispersions (13000 kDa,

) using a combination of static and dynamic light scattering methods [

37]. Shirota et al. aimed to determine the CST of PNiPAm hydrogels by microscopically observing the volume phase transition and also reported a higher CST in D

2O of approximately 1 °C [

28]. We note that all these studies also relied on observing the aggregation of PNiPAm at high local concentrations and not the solvation transition directly.

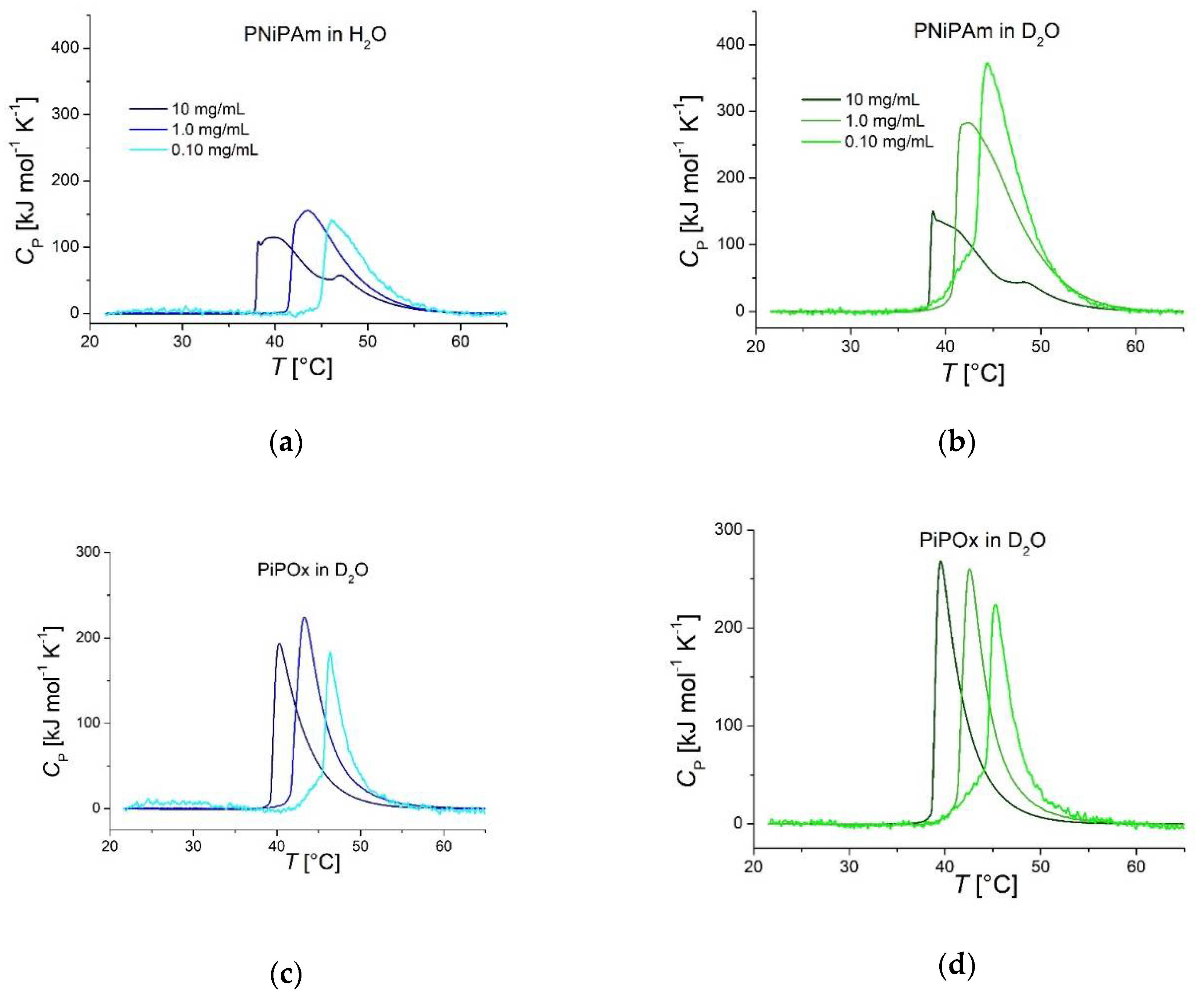

Figure 2a shows DSC thermograms of PNiPAm in H

2O and D

2O. The long high-temperature tails hint at a more complex process than a simple two-state transition. In contrast, the PiPOx thermograms shown in

Figure 2c,d suggest that the transitions differ less between the highest and lowest concentrations than for PNiPAm. Especially the heating curves of 10 mg ml

-1 PNiPAm plotted in panels (a) and (b) of

Figure 2 show more than one peak after a very sharp initial incline.

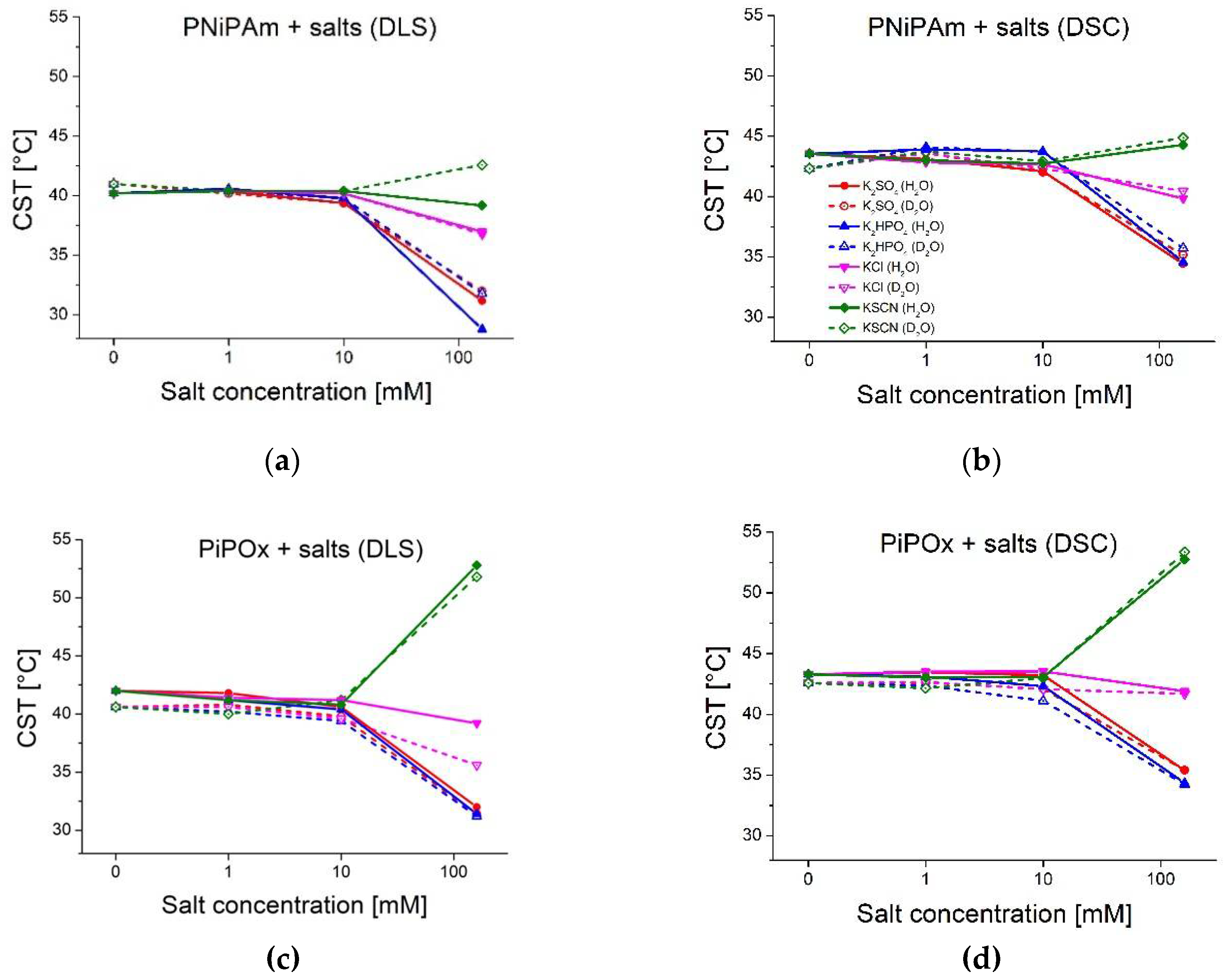

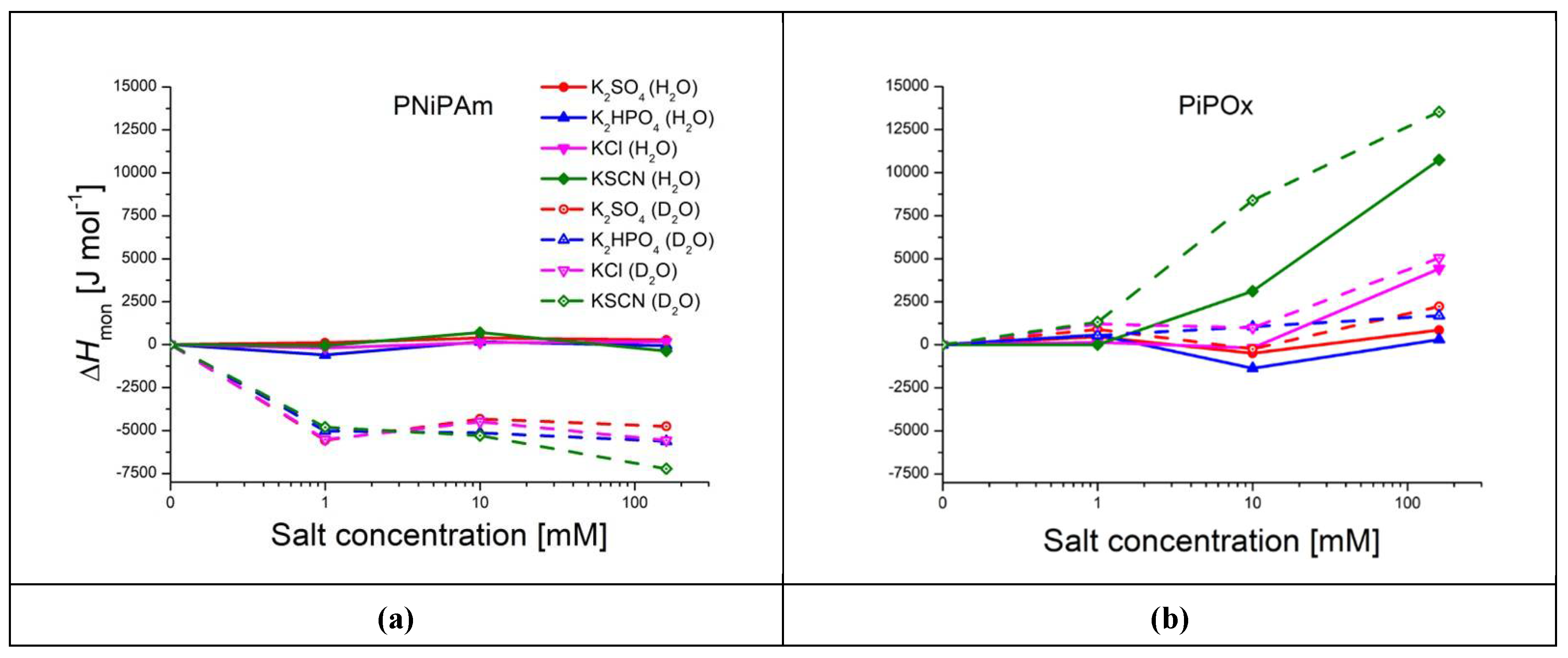

2.2. Hofmeister Series Anions and Solvent Isotope Effect

Figure 3 shows the CST values of both polymers derived from DLS and DSC experiments for different concentrations of the Hofmeister anion salts: KSCN, K

2HPO

4, KCl, and K

2SO

4. The CST was measured in a pure solvent, as well as in the presence of potassium salts of four different anions: thiocyanate (

), chloride (

), hydrogen phosphate (

), and sulfate (

), representing chaotropic and kosmotropic anions of the Hofmeister series [

17]. It is noticeable that with increasing salt concentration, CSTs shift further away from the values in pure solvent (see also

Table S3). This is true for both polymers in H

2O and D

2O, regardless of the measurement method. However, up to 10 mM concentration, all the salt effects are minor or negligible. For example, the CST value of PiPOx in 1 mM

is the same as for 1 mM

in H

2O (both 41.2 °C) and even slightly lower in D

2O (40.0 °C for 1mM

compared to 40.2 °C of PiPOx in 1 mM

). The chaotropic properties of

are not visible at the lowest concentration. These results show that significant changes to the CST, as measured by both DLS and DSC, only occur for ionic strengths in the 100 mM range. However, DLS measurements of PNiPAm or PiPOx in solutions of physiological ionic strength (160 mM potassium salts) clearly show how chaotropic and kosmotropic substances from the Hofmeister series affect polymer stability.

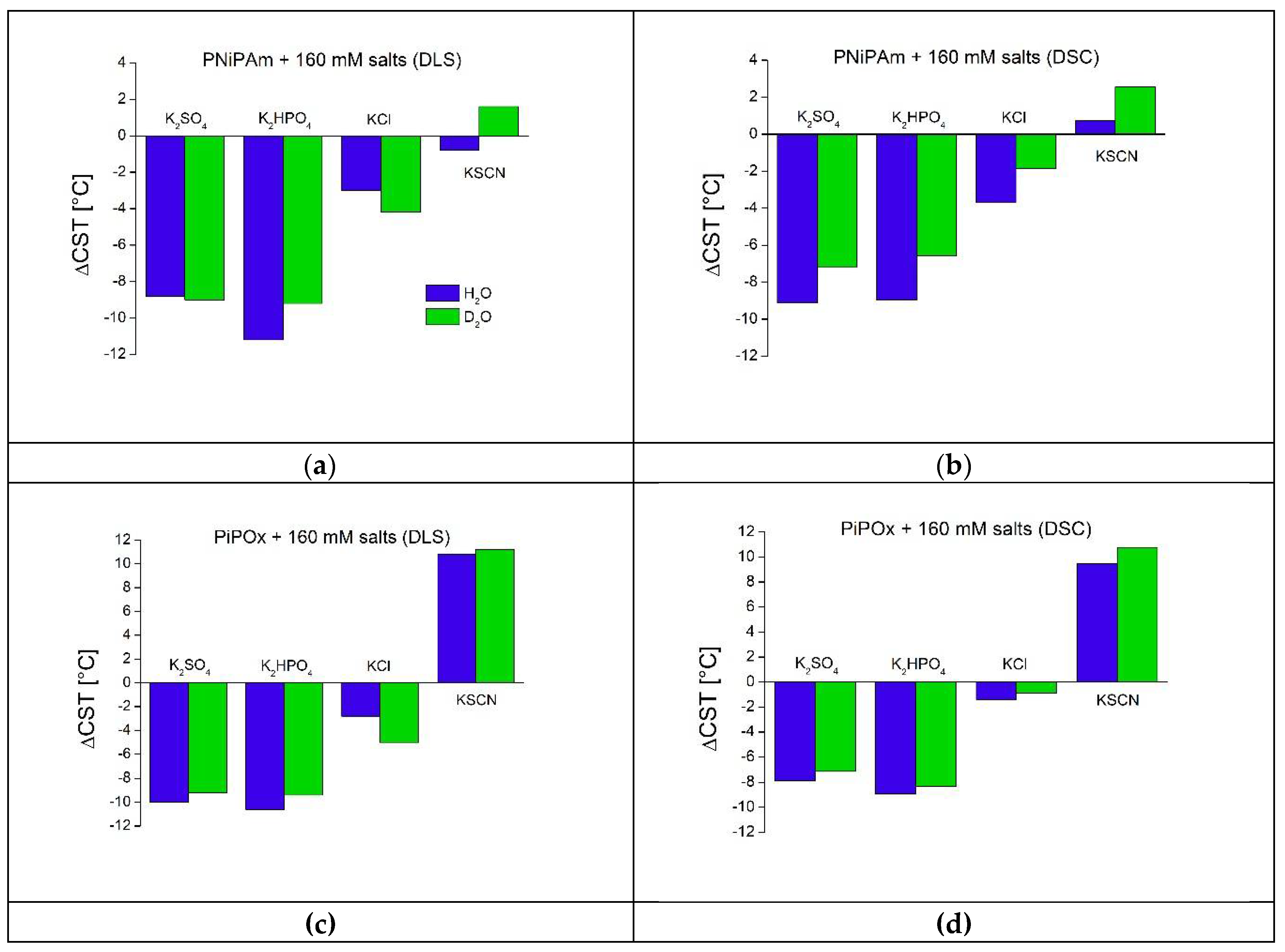

Figure 4 highlights these differences by comparing the CST of both polymers in a pure solvent and the presence of 160 mM salts.

The kosmotropic anion concentration generally affects PiPOx in the same way in H

2O and D

2O.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show how high concentrations of strong kosmotropes like

and

drastically reduce the CST of both polymers in pure H

2O or D

2O by approximately 7-10 °C. The chaotropic anion

promotes hydration of the polymer chain, increasing the CST. However, the effect is not as pronounced for PNiPAm as the effect of the kosmotropic ions. In the case of PNiPAm in H

2O, low concentrations of

do not increase the CST above the value measured in pure water. The same result is observed for PiPOx samples measured with both DLS and DSC for low ionic strengths, but the chaotropic effect of KSCN is on par with the kosmotropic ions at physiological ionic strength, shifting the CST higher by about 10 °C for PiPOx.

Comparing DSC peak maxima, CST shifts between H

2O and D

2O are generally smaller than 1 °C for PiPOx in the presence of all salt concentrations (see

Table S3). The same is true for CST values determined with DLS. The DSC measurements for PNiPAm are significantly different in 160 mM ionic strength, where the change in the CST values in D

2O is lower than in H

2O, generally with a difference in the shift of ~2 °C. Notably, the change of the CST for the chaotropic ion

is about 1.8 °C higher in D2O than in H

2O, indicating that PNiPAm retains a higher hydration in H

2O than in D

2O. An outlier compared to the other ions is KCl, for which H

2O seems to induce a lower effect on the hydration than D

2O for both PNiPAm and PiPOx.

2.3. Transition Energetics

In

Figure 2a and b, very large transition enthalpies per monomer are observed for PNiPAm (0.1 mg ml

-1 and 1 mg ml

-1) measured in D

2O compared to in H

2O. These samples require approximately twice the enthalpy per monomer unit compared to the same sample in H

2O (11838 J mol

-1 and 11459 J mol

-1 versus 4178 J mol

-1 and 5568 J mol

-1; see

Table 1). In comparison, Diab et al. reported a transition enthalpy of 5983.12 J mol

-1 for 1000 mg ml

-1 PNiPAm (13 kDa) in D

2O [

38], which is similar to our result for the same concentration. PiPOx didn’t show such significant differences in transition enthalpy and had a more uniform peak shape (

Figure 2c and d). There seems to be a weak correlation of a moderate increase in transition enthalpy for both polymers in H

2O. In D

2O, there are only minor differences in transition enthalpy for PiPOx. Still, PNiPAm shows a dramatic difference in peak

Cp and transition enthalpy for the lower concentrations compared to the highest. Both decrease with increasing concentration (

Table 1 and

Figure 2).

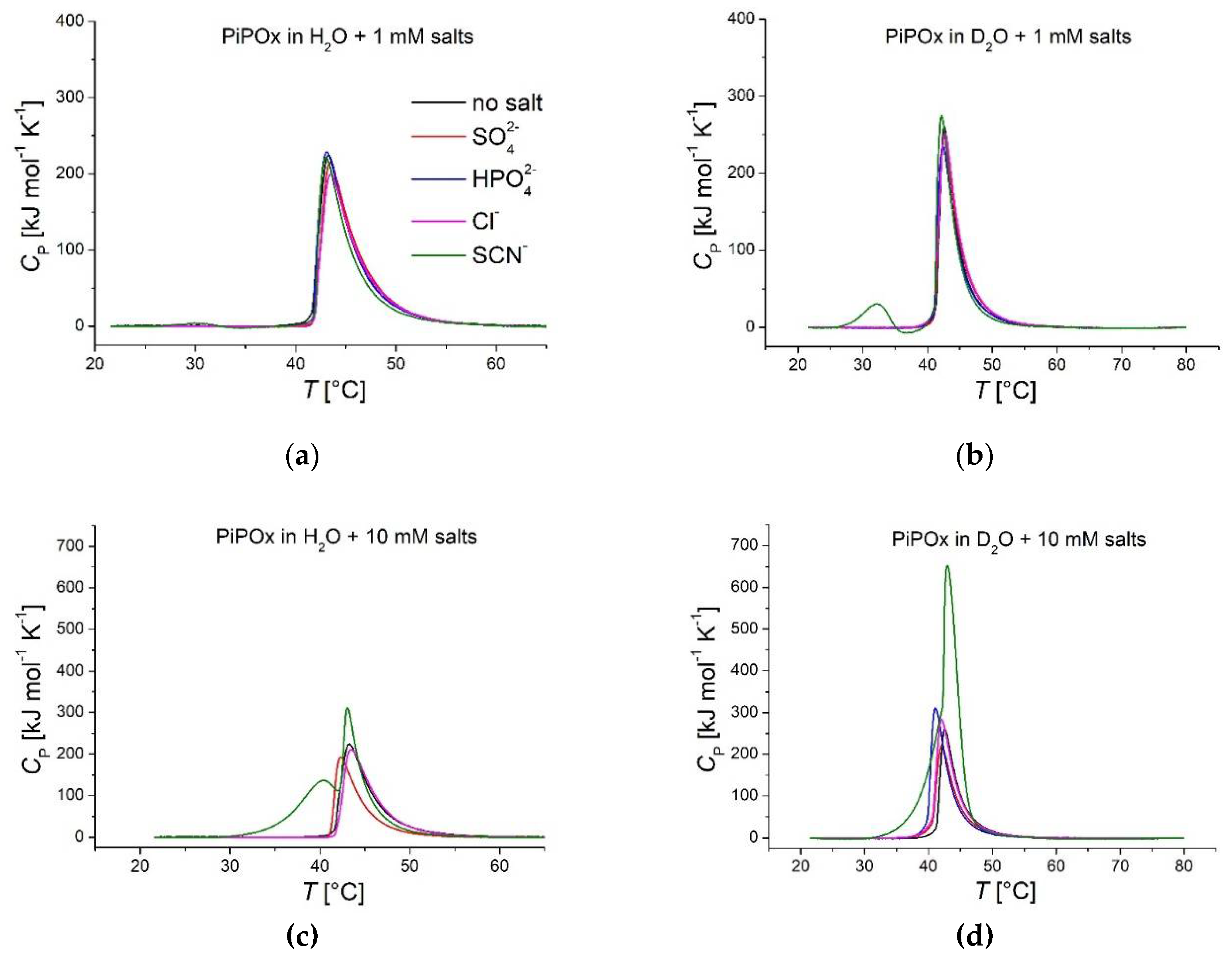

Figure 5 presents thermograms of PiPOx in H

2O and D

2O co-solved with salts of increasing varying concentration. In contrast to PNiPAm, PiPOx is affected more profoundly in its transition in the presence of some salts (compare

Figure 5 and

Figure S1), as seen from the shoulders and a second peak. The most pronounced effects are observed for the strong chaotrope

and the weak kosmotrope

(sometimes also referred to as a chaotrope) in H

2O.

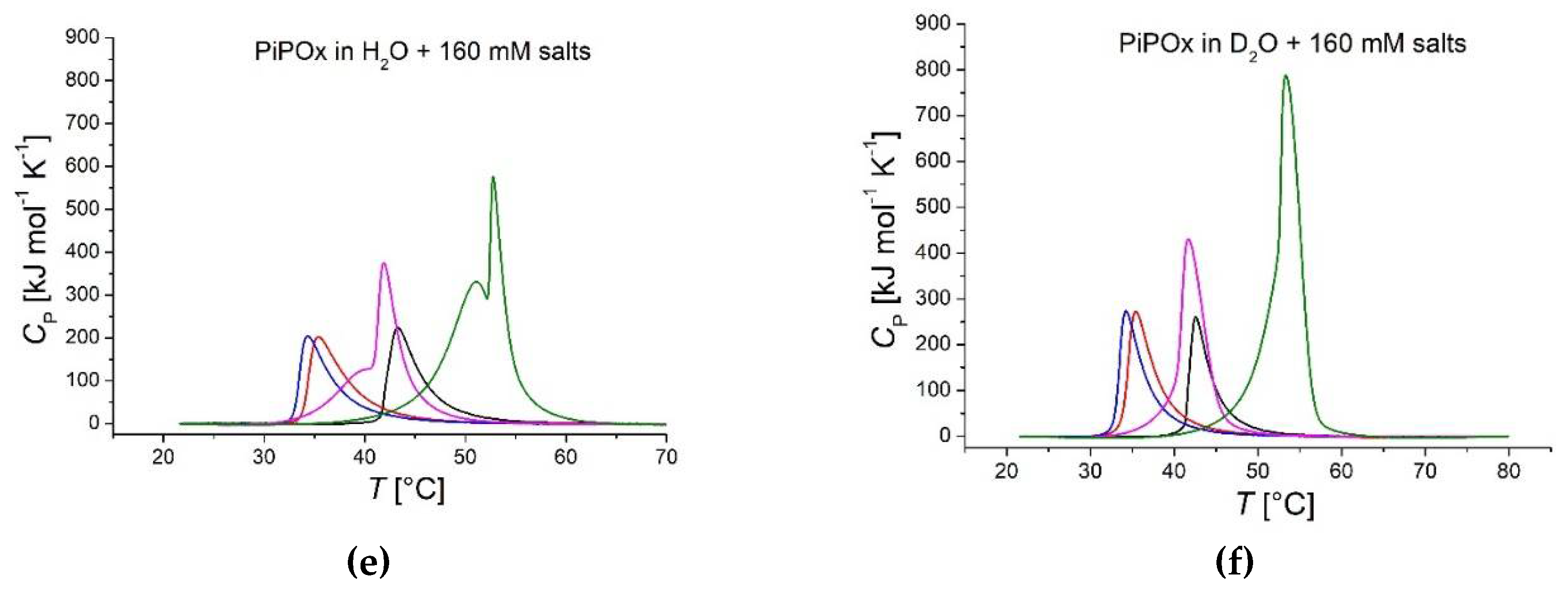

Data collected in

Figure 6 shows that the multi-step conformational change of PiPOx in the presence of medium to high concentrations of KSCN requires far more heat than in the presence of other salts, with

ranging from 7838 J mol

-1 (PiPOx in a solution of 10 mM KSCN in H

2O) to 18000 J mol

-1 (PiPOx in D

2O + 160 mM KSCN), compared to other samples with enthalpies mostly between 4000 and 6000 J mol

-1. This chaotrope thereby uniquely stabilizes the solvated polymer, as also evidenced by the higher CST. Although 160 mM KCl still leads to a kosmotropic effect on the CST, it also leads to a much higher transition enthalpy, especially in H

2O but also in D

2O; it displays pronounced double-peaks and transition enthalpies of 9135 J mol

-1 in H

2O and 9514 J mol

-1 in D

2O at 160 mM (

Figure 5e and f). In the PNiPAm samples, there seems to be no connection between CST and transition enthalpy. Values for

vary by approximately only 12 % between samples of the same salt concentration in H

2O and D

2O, except for PNiPAm in pure D

2O, for which it is almost twice as high as in H

2O or in D

2O salt solutions (11459 J mol

-1;

Figure 6 and

Table S4).

3. Discussion

Even though PNiPAm and PiPOx are structural isomers, they did not respond the same to being solvated in D

2O instead of H

2O. PiPOx clearly decreases its CST in D

2O. D

2O seems to decrease the CST for PNiPAm as well, at least at low concentration, but the DSC measurements reveal a possible two-step transition that becomes more accentuated in D

2O and leads to a strong concentration dependence (

Figure 2). Hence, the CST determined from DLS is higher in D

2O than in H

2O, while the CST determined from the peak of the main transition is lower in D

2O than in H

2O. Previously published literature does not report similar features in the DSC curves, but experimental conditions differ from the measurements conducted in this study. To investigate this phenomenon in more detail, follow-up research would be required, especially to pinpoint if the switch from H

2O to D

2O influences the hydration of different hydrogen-bonding groups on the polymers differently.

Compared to the Hofmeister series ions' effects on the CST of PNiPAm and PiPOx, we observe that D

2O has a relatively small influence. 160 mM strong kosmotropes and chaotropes solutions influenced the CSTs and the energetics of the solubility transition the most. Still, the difference between H

2O and D

2O was on par or larger than the effect of Hofmeister salts up to salt concentrations higher than 10 mM, especially for PiPOx. Both polymers significantly decrease their CST in response to strong kosmotropes in D

2O and H

2O. Interestingly, the relative effect of D

2O on the CST (in particular measured by DLS) and the transition energy were most pronounced for

and

, which are usually classified as strong and weak chaotropes. A first explanation could be that anions like

are hydrated weaker in D

2O than water and are associated closer to the polymer chain. This could lead to enhanced stabilization, i.e., a higher CST [

16,

39]. Hence, non-kosmotropes might be more influenced by a shift from H

2O to D

2O. Cremer and coworkers similarly proposed that chaotropes can stabilize amide side groups of PNiPAm and increase polymer solubility [

40].

Additionally, the differences in the shifts of the CST for PNiPAm with respect to Hofmeister ions were significantly different in magnitude for H2O and D2O. They generally differed by as much as 3 °C, while such differences were not observed for PiPOx. Again, this highlights that hydration effects depend on the nature of the polar, hydrogen-bonding groups on the polymer or the groups’ local environments, as PiPOx and PNiPAm are structural isomers.

Related to these observations, the solubility transition seems to include at least two solvation transitions following upon each other for PiPOx in H2O, making a determination of the CST using DSC by the peak Cp value ambiguous but revealing these additional details. Tentatively different parts of the polymer chains get dehydrated at different temperatures, reflecting preferential interactions of the anion with parts of the polymer. This could lead to significant differences between the CST determined by turbidity or DLS measurements and those determined by DSC. Unlike PNiPAm, PiPOx has an amide group in its backbone. Stronger hydration of in water than in D2O may allow the anion to stabilize the polymer backbone longer, leading to dehydration of the side chains first, which might cause the multiple transitions for PiPOx samples with KSCN (or KCl) solved in H2O as well as the higher CST than PNiPAm.

Curiously, polymer concentration greatly influenced the transition enthalpy of PNiPAm in D2O. The influence of polymer concentration on the CST is well known and was observed for all samples and solvents in our study, but this effect on the transition enthalpy stands out and could not be fully explained. Further, the observations of a two times higher enthalpy of the transition in D2O than in H2O, which strongly decreased at high polymer concentration, highlights that several parameters of the investigated system must be considered if one wants to determine CST in a specific environment, in particular in D2O.

Our observation of multiple transitions affected by the polarity of the solvent and the presence of Hofmeister anions requires further investigation of the molecular weight dependence of these features and whether they respond to different sidechain modifications. Previous publications have shown that the CST is decreased with increasing molecular weight for PNiPAm and PiPOx [

38,

41] and that sidechain modifications and polymer morphology, e.g., grafting, greatly influence the CST and internal coil and coil-coil desolvation transitions [

25,

42,

43].

In summary, we conclude that the thermoresponsive properties of polymers quantitatively differ in D2O and H2O, but the absolute differences depend on the polymer and solution conditions. The observed effects of changing from H2O to D2O were smaller than those of other commonly varied parameters, such as polymer concentration or the presence of physiological concentrations of Hofmeister series ions, but they are not negligible. Further, our results strongly imply that effects of different environmental parameters are not additive with this change in solvent, i.e., the dehydration of different molecular groups in a polymer can be differently affected as well as their interactions with Hofmeister series anions, which could, in turn, influence the overall thermoresponsive behavior. This was tentatively observed for the influence of amine polar bonds and chaotropic anions. These polymer-internal changes to the transition could be especially important if more complicated polymer morphologies, such as dendritic polymers or grafted polymers, are studied.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Polymer Synthesis

4.1.1. 2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline

The following synthesis of the 2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline (iPOx) monomer adapts the Witte-Seeliger cyclocondensation described in Schroffenegger et al. [

44,

45,

46].

Synthesis was conducted by mixing 45 mL (or 1 equivalent) of 2-methylpropanenitrile (Sigma-Aldrich) with 36 mL (1.2 eq.) ethanolamine (Sigma-Aldrich). Zinc acetate dihydrate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to catalyze the reaction (2.2038 g or 0.02 eq.). Heated to 130 °C in an oil bath and equipped with a reflux cooler, the solution was left to react in an inert atmosphere for one day. Formed ammonia was absorbed in hydrochloric acid. The product was dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM, Sigma-Aldrich) and extracted with MQ-H2O until the pH of the aqueous phase was neutral. The organic phase was dried with sodium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich). The solid was removed by filtration, and the product was separated from the solvent by vacuum distillation. After adding calcium hydride (Sigma-Aldrich), the solution was stirred under inert conditions to remove residual water. Finally, the product was purified using distillation with a Vigreux column at 50 °C and 50 mbar.

4.1.2. Poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline)

Polymerization of 2-Isopropyl-2-oxazoline followed Schroffenegger et al., who describe a cationic ring-opening polymerization (CROP) [

46]. 3 ml of the monomer and 9 ml

N,N-dimethylacetamide anhydrous (DMA, Sigma-Aldrich) were mixed with 38 µl methyl-

p-tosylate (Sigma-Aldrich) and left to react at 90 °C overnight. The reaction was quenched with sodium hydroxide and stirred for three hours at 50 °C, then at room temperature until the next day. The product was obtained by stepwise precipitation of the reaction mixture in approximately 25 ml of a 1:1 mixture of

n-hexane (Sigma-Aldrich) and diethyl ether (Carl Roth). The precipitate was then dissolved in DCM and purified by distillation.

Degree of polymerization (DP): 186; molecular weight (MW): 21 kDa; polydispersity index (PDI): 1.038; yield: 2.68 g, 94 %. 1H-NMR δH(300 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) 3.46 (d, 2H), 3.00 (s, 3H), 2.77 (d, 1H), 1.10 (s, 6H)

4.1.3. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)

This synthesis, described in Kurzhals et al., is an acid-terminated atomic transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) [

47]. First, the monomer

N-isopropyl acrylamide (NiPAm, Sigma-Aldrich) is recrystallized by dissolving 2 g NiPAm in 25 ml toluene (Carl Roth) and 35 ml

n-hexane and storing it at -20 °C overnight. The precipitate was then filtered and rinsed with

n-hexane, followed by vacuum distillation to remove the solvent.NiPAm (0.8 g), copper(II) bromide (1.6 mg, Sigma-Aldrich), copper(I) bromide (10.3 mg, Sigma-Aldrich) and 2-bromo-2-methylpropionic acid (13.4 mg, Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in 10 % methanol (Carl Roth) and purged with nitrogen while being cooled in an ice bath. After 20 minutes, 40 µl tris[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]amine (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1 ml MQ-H

2O were added to start the reaction, which continued for 24 h at 4 °C in an inert atmosphere. The polymerization was stopped by opening the flask to air, and the product separated from the reaction mixture by heating it to 50 °C to let the polymer precipitate. The supernatant was discarded. The gel-like, blue-colored polymer was dissolved in approximately 5 mL of tetrahydrofuran anhydrous (THF, Sigma-Aldrich) before reprecipitating in approximately 15 mL of cooled diethyl ether. The solid was dried in an evacuated desiccator. The polymer was solved again in Milli-Q H2O to remove impurities and dialyzed for four days; the water was changed five times. Finally, the polymer was then dried by lyophilization.

DP: 188; MW: 21 kDa; PDI: 1.049; yield: 0.62 g, 77 %. 1H-NMR δH(300 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) 4.02 (s, 1H), 2.14 (s, 1H), 1.66 (d, 2H), 1.15 (d, 6H)

4.2. Polymer Characterization

The molecular weight (

MW), as well as the polydispersity index (PDI) of PNiPAm and PiPOx were determined with gel permeation chromatography (GPC) based on their R

G against a standard of polystyrene in

N,

N-dimethylformamide (DMF) using a Malvern Viscotek GPC max and OmniSEC (Malvern Panalytical) 5.12 software (see

Figure S3 and S4). For the measurement, 3.5 mg polymer were dissolved in 1 ml DMF containing 0.05 mol l

-1 lithium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich). 50 µl of sample were measured at a flow rate of 9.5 ml min

-1 at 60 °C.

Successful synthesis in terms of correct chemical structure was investigated with nuclear magnetic resonance (

1H-NMR) with a BRUKER AV III 300 MHz spectrometer (Bruker Austria GmbH). 50 mg ml

-1 of either polymer were used to record the respective spectra in deuterated trichloromethane (Sigma-Aldrich). The chemical shifts (δ in ppm) were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS); see

Figures S3-S6 and

Table S4.

4.3. Determination of the Critical Solution Temperature

Solutions of PNiPAm and PiPOx in three different concentrations were prepared in H2O and D2O (0.1 mg ml-1, 1 mg ml-1, and 10 mg ml-1). Additionally, 1 mg ml-1 solutions of each polymer were prepared in either solvent containing one of four potassium salts in different concentrations (160 mM, 10 mM, or 1 mM of (≥99.0%, Sigma-Aldrich), (≥99%, Riedel-de Haën), KCl (>99.5%, Fluka BioChemika) and KSCN (≥98.0%, Merck), respectively). DLS size measurements were recorded with a step size of 1 kelvin and an equilibration time of 60 seconds. Close to the expected CST, increments were reduced to 0.2 K, and equilibration time after each step increased to 120 seconds for higher precision. At each point, three individual measurements were recorded with an automatically set number of runs and then averaged. All samples were measured with a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical) in backscatter mode. CST values were extracted at the initial increase of the recorded scattering patterns. For DSC experiments, 325 µl of each sample was scanned from 20 °C to 80 °C at a rate of 1 °C per minute with a PEAQ_DSC Automated (Malvern Panalytical). Before starting the measurements, the system was thermally equilibrated for 5 minutes, and 3 purge refills of the autosampler were performed between samples. CST values were extracted from the recorded thermograms at the transition peak maximum.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: DSC-recorded thermograms of PNiPAm in H2O and D2O; Figure S2: 1H NMR spectrum for PNiPAm; Figure S3: 1H NMR spectrum for PiPOx; Figure S4: GPC of PNiPAm; Figure S5: GPC of PiPOx; Table S1: CST of differently concentrated PNiPAm and PiPOx dispersions; Table S2: Comparison of onset and peak temperature values in DSC thermograms of PNiPAm and PiPOx; Table S3: CST of PNiPAm and PiPOx in Hofmeister series salt solutions; Table S4: Transition enthalpies of PNiPAm and PiPOx; Table S5: Polymer weight and polydispersity; Equation S1: PDI calculation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.; methodology, E.R.; validation, E.R. and K.N.B.; formal analysis, E.R., and K.N.B.; investigation, K.N.B.; resources, E.R.; data curation, K.N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.N.B.; writing—review and editing, K.N.B. and E.R.; visualization, K.N.B.; supervision, E.R.; project administration, E.R.; funding acquisition, E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge BOKU University and the BOKU Doctoral School Biomaterials & Biointerfaces for financial support.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request by the authors.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by EQ-BOKU VIBT GmbH through access to the DSC at the BOKU Core Facility for Biomolecular and Cellular Analysis. The authors thank Max Willinger for his contribution to polymer synthesis, and the Institute of Organic Chemistry, BOKU for carrying out NMR spectroscopy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lu, Y.; Aimetti, A.A.; Langer, R.; Gu, Z. Bioresponsive Materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskins, M.; Guillet, J.E. Solution Properties of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide). J. Macromol. Sci. Part - Chem. 1968, 2, 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schattling, P.; D. Jochum, F.; Theato, P. Multi-Stimuli Responsive Polymers – the All-in-One Talents. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, C.M. Nanobiotechnology. In Encyclopedia of Molecular Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; ISBN 978-3-527-60090-8. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, M.R.; Elvira, C.; Gallardo, A.; Vázquez, B.; Román, J.S. Smart Polymers and Their Applications as Biomaterials. Smart Polym. 3, 27.

- Klouda, L. Thermoresponsive Hydrogels in Biomedical Applications: A Seven-Year Update. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 97, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wang, D.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Electrostatic Self-Assembly of Au Nanoparticles onto Thermosensitive Magnetic Core-Shell Microgels for Thermally Tunable and Magnetically Recyclable Catalysis. Small 2015, 11, 2807–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin, A.; Kröger, M.; Winnik, F.M. Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Phase Diagrams: Fifty Years of Research. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15342–15367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, Y. PNIPAM Microgels for Biomedical Applications: From Dispersed Particles to 3D Assemblies. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 6375–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, W. Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide)-Based Smart Hydrogels: Design, Properties and Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 115, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, T.; Yamada, N.; Sakai, H.; Sakurai, Y. A Novel Recovery System for Cultured Cells Using Plasma-Treated Polystyrene Dishes Grafted with Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide). J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1993, 27, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doberenz, F.; Zeng, K.; Willems, C.; Zhang, K.; Groth, T. Thermoresponsive Polymers and Their Biomedical Application in Tissue Engineering – a Review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Weber, C.; Schubert, U.S.; Hoogenboom, R. Thermoresponsive Polymers with Lower Critical Solution Temperature: From Fundamental Aspects and Measuring Techniques to Recommended Turbidimetry Conditions. Mater. Horiz. 2017, 4, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, R. Poly(2-Oxazoline)s: A Polymer Class with Numerous Potential Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7978–7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Temperature Responsive Bio-Compatible Polymers Based on Poly(Ethylene Oxide) and Poly(2-Oxazoline)s. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 686–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, S.Z.; Thormann, E. Hofmeister Effect on Thermo-Responsive Poly(Propylene Oxide) in H2O and D2O. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 27969–27973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, F. Zur Lehre von der Wirkung der Salze: Dritte Mittheilung. Arch. Für Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 1888, 25, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwa, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Akashi, M.; Takano, K.; Tanaka, N.; Kunugi, S. Effects of Salt on the Temperature and Pressure Responsive Properties of Poly( N -Vinylisobutyramide) Aqueous Solutions. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1998, 276, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cremer, P.S. Interactions between Macromolecules and Ions: The Hofmeister Series. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006, 10, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Furyk, S.; Bergbreiter, D.E.; Cremer, P.S. Specific Ion Effects on the Water Solubility of Macromolecules: PNIPAM and the Hofmeister Series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14505–14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moelbert, S.; Normand, B.; De Los Rios, P. Kosmotropes and Chaotropes: Modelling Preferential Exclusion, Binding and Aggregate Stability. Biophys. Chem. 2004, 112, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, S.; Čuma, M. Relative Stability of Hydrogen and Deuterium Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Sagle, L.B.; Iimura, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kherb, J.; Chilkoti, A.; Scholtz, J.M.; Cremer, P.S. Hydrogen Bonding of β-Turn Structure Is Stabilized in D2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15188–15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, M.M.; Makhatadze, G.I. Solvent Isotope Effect on Thermodynamics of Hydration. Biophys. Chem. 1998, 74, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroffenegger, M.; Zirbs, R.; Kurzhals, S.; Reimhult, E. The Role of Chain Molecular Weight and Hofmeister Series Ions in Thermal Aggregation of Poly(2-Isopropyl-2-Oxazoline) Grafted Nanoparticles. Polymers 2018, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luxenhofer, R.; Sahay, G.; Schulz, A.; Alakhova, D.; Bronich, T.K.; Jordan, R.; Kabanov, A.V. Structure-Property Relationship in Cytotoxicity and Cell Uptake of Poly(2-Oxazoline) Amphiphiles. J. Controlled Release 2011, 153, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogenboom, R.; Schlaad, H. Thermoresponsive Poly(2-Oxazoline)s, Polypeptoids, and Polypeptides. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirota, H.; Endo, N.; Horie, K. Volume Phase Transition of Polymer Gel in Water and Heavy Water. Chem. Phys. 1998, 238, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzhals, S.; Schroffenegger, M.; Gal, N.; Zirbs, R.; Reimhult, E. Influence of Grafted Block Copolymer Structure on Thermoresponsiveness of Superparamagnetic Core–Shell Nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, M.H.; Hsieh, B.R.; Krieger, I.M.; Chen, T.T.; Lu, H.L. Low Surface Energy Polymers and Surface-Active Block Polymers: II. Rigid Microporous Foams by Emulsion Polymerization. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1987, 115, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, L.; Bastos-González, D.; Faraudo, J.; Drummond, C. Effect of Organic and Inorganic Ions on the Lower Critical Solution Transition and Aggregation of PNIPAM. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 7818–7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.-T.; Yao, Z.-H.; Chang, Y.-T.; Wang, F.-M.; Chern, C.-S. LCST Phase Transition Kinetics of Aqueous Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 93, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, H.G.; Tirrell, D.A. Microcalorimetric Detection of Lower Critical Solution Temperatures in Aqueous Polymer Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 4352–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunugi, S.; Tada, T.; Tanaka, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Akashi, M. Microcalorimetric Study of Aqueous Solution of a Thermoresponsive Polymer, Poly(N-Vinylisobutyramide) (PNVIBA). Polym. J. 2002, 34, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyama, H.; Kobayashi, S. A Novel Thermo-Sensitive Polymer. Poly(2-Iso-Propyl-2-Oxazoline). Chem. Lett. 1992, 21, 1643–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamies, R.; Zhu, K.; Kjøniksen, A.-L.; Nyström, B. Thermal Response of Low Molecular Weight Poly-(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Polymers in Aqueous Solution. Polym. Bull. 2009, 62, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, C. Light-Scattering Study of Coil-to-Globule Transition of a Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Chain in Deuterated Water. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 4299–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, C.; Akiyama, Y.; Kataoka, K.; Winnik, F.M. Microcalorimetric Study of the Temperature-Induced Phase Separation in Aqueous Solutions of Poly(2-Isopropyl-2-Oxazolines). Macromolecules 2004, 37, 2556–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner Swain, C.; Bader, R.F.W. The Nature of the Structure Difference between Light and Heavy Water and the Origin of the Solvent Isotope Effect—I. Tetrahedron 1960, 10, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Furyk, S.; Bergbreiter, D.E.; Cremer, P.S. Specific Ion Effects on the Water Solubility of Macromolecules: PNIPAM and the Hofmeister Series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14505–14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furyk, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ortiz-Acosta, D.; Cremer, P.S.; Bergbreiter, D.E. Effects of End Group Polarity and Molecular Weight on the Lower Critical Solution Temperature of Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide). J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhon, Y.K.; Bhat, R.R.; Jeong, C.; Rojas, O.J.; Szleifer, I.; Genzer, J. Salt-Induced Depression of Lower Critical Solution Temperature in a Surface-Grafted Neutral Thermoresponsive Polymer. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006, 27, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroffenegger, M.; Reimhult, E. Thermoresponsive Core-Shell Nanoparticles: Does Core Size Matter? Materials 2018, 11, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, H.; Seeliger, W. Cyclische Imidsäureester aus Nitrilen und Aminoalkoholen. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1974, 1974, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnery, B.D.; Shaunak, S.; Thanou, M.; Steinke, J.H.G. Improved Synthesis of Linear Poly(Ethylenimine) via Low-Temperature Polymerization of 2-Isopropyl-2-Oxazoline in Chlorobenzene. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 3197–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroffenegger, M.; Zirbs, R.; Kurzhals, S.; Reimhult, E. The Role of Chain Molecular Weight and Hofmeister Series Ions in Thermal Aggregation of Poly(2-Isopropyl-2-Oxazoline) Grafted Nanoparticles. Polymers 2018, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzhals, S.; Zirbs, R.; Reimhult, E. Synthesis and Magneto-Thermal Actuation of Iron Oxide Core–PNIPAM Shell Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 19342–19352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effect of solvent and polymer concentration on the CST (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa). Black lines: CST values of PNiPAm, red lines: CST values of PiPOx; solid lines: polymers dispersed in H2O, dashed lines: polymers dispersed in D2O (a) measurements with DLS; (b) measurements with DSC.

Figure 1.

Effect of solvent and polymer concentration on the CST (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa). Black lines: CST values of PNiPAm, red lines: CST values of PiPOx; solid lines: polymers dispersed in H2O, dashed lines: polymers dispersed in D2O (a) measurements with DLS; (b) measurements with DSC.

Figure 2.

DSC recorded thermograms of PNiPAm and PiPOx (21 kDa) measured in (a, c) D2O and (b, d) H2O. Darker colors represent higher polymer concentrations.

Figure 2.

DSC recorded thermograms of PNiPAm and PiPOx (21 kDa) measured in (a, c) D2O and (b, d) H2O. Darker colors represent higher polymer concentrations.

Figure 3.

Effect of salt concentration (0 mM, 1 mM, 10 mM, and 160 mM) on polymer CST in H2O and D2O (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa; 1 mg ml-1). Red: , blue: , pink: KCl, green: KSCN; solid lines: measured in H2O, dashed lines: D2O (a) PNiPAm measured with DLS; (b) PNiPAm measured with DSC; (c) PiPOx measured with DLS; (d) PiPOx measured with DSC.

Figure 3.

Effect of salt concentration (0 mM, 1 mM, 10 mM, and 160 mM) on polymer CST in H2O and D2O (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa; 1 mg ml-1). Red: , blue: , pink: KCl, green: KSCN; solid lines: measured in H2O, dashed lines: D2O (a) PNiPAm measured with DLS; (b) PNiPAm measured with DSC; (c) PiPOx measured with DLS; (d) PiPOx measured with DSC.

Figure 4.

Effect of physiological salt concentration (160 mM) on polymer CST in H2O and D2O (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa, 1 mg ml-1) compared to pure solvents. Blue: measured in H2O, green: D2O (a) PNiPAm measured with DLS; (b) PNiPAm measured with DSC; (c) PiPOx measured with DLS; (d) PiPOx measured with DSC.

Figure 4.

Effect of physiological salt concentration (160 mM) on polymer CST in H2O and D2O (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa, 1 mg ml-1) compared to pure solvents. Blue: measured in H2O, green: D2O (a) PNiPAm measured with DLS; (b) PNiPAm measured with DSC; (c) PiPOx measured with DLS; (d) PiPOx measured with DSC.

Figure 5.

DSC recorded thermograms of PiPOx (21 kDa, 1 mg ml-1) in H2O and D2O. Red: , blue: , pink: KCl, green: KSCN; polymer dispersed in solutions of (a) 1 mM salts in H2O; (b) 1 mM salts in D2O; (c) 10 mM salts in H2O; (d) 10 mM salts in D2O; (e) 160 mM salts in H2O and (f) 160 mM salts in D2O.

Figure 5.

DSC recorded thermograms of PiPOx (21 kDa, 1 mg ml-1) in H2O and D2O. Red: , blue: , pink: KCl, green: KSCN; polymer dispersed in solutions of (a) 1 mM salts in H2O; (b) 1 mM salts in D2O; (c) 10 mM salts in H2O; (d) 10 mM salts in D2O; (e) 160 mM salts in H2O and (f) 160 mM salts in D2O.

Figure 6.

Effect of salt concentration (1 mM, 10 mM, and 160 mM) on polymer transition enthalpies per monomer unit (ΔHmon) in H2O and D2O (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa; 1 mg ml-1). Red: , blue: , pink: KCl, green: KSCN; solid lines: measured in H2O, dashed lines: D2O. Plotted are delta values compared to ΔHmon in the pure solution of (a) PNiPAm and (b) PiPOx.

Figure 6.

Effect of salt concentration (1 mM, 10 mM, and 160 mM) on polymer transition enthalpies per monomer unit (ΔHmon) in H2O and D2O (PiPOx and PNiPAm: 21 kDa; 1 mg ml-1). Red: , blue: , pink: KCl, green: KSCN; solid lines: measured in H2O, dashed lines: D2O. Plotted are delta values compared to ΔHmon in the pure solution of (a) PNiPAm and (b) PiPOx.

Table 1.

DSC-derived transition enthalpies per monomer unit for differently concentrated PNiPAm and PiPOx dispersions (21 kDa) prepared in H2O and D2O.

Table 1.

DSC-derived transition enthalpies per monomer unit for differently concentrated PNiPAm and PiPOx dispersions (21 kDa) prepared in H2O and D2O.

| PNiPAm |

ΔHmonomer [J mol-1] |

| ρ [mg ml-1] |

H2O |

D2O |

| 10-1

|

4178 |

11838 |

| 100

|

5568 |

11459 |

| 101

|

5335 |

5676 |

| PiPOx |

ΔHmonomer [J mol-1] |

| ρ [mg ml-1] |

H2O |

D2O |

| 10-1

|

3708 |

4865 |

| 100

|

5324 |

5259 |

| 101

|

4535 |

5189 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).