1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Problem

Urban agriculture (UA) is known to be practiced worldwide and is increasingly being promoted, particularly in low-income countries. UA is an activity practiced in Africa with particular characteristics: it is not leisure [

1]. African UA is practiced for several reasons, each contributing to its growing prominence across cities and towns. Cultivating, processing, and distributing food in or around urban areas has become increasingly important due to economic, social, environmental, and health-related factors [

2]. UA is a significant activity in many African urban centers. One of these is that the areas concerned are vast. Secondly, it is income-generating, especially as many women are involved. Its contribution to health through food security is among the reasons for promoting it [

3]. The health aspects of this activity are often not studied by urban planners, and even though UA is practiced on urban land, they are supposed to be planned [

4].

UA has mixed effects on the health of practitioners, consumers, and city dwellers where it is practiced [

5,

6]. According to Ba et al., (2016), nitrate toxicity, for instance, generated through UA practices, is harmful to the health of consumers and even farmers due to their pollution. Inappropriate application of pesticides and chemical fertilizers can result in direct exposure for urban farmers and food contamination for consumers. Chronic exposure to pesticides is associated with a variety of health problems, including neurological disorders and cancers [

8]. Moreover, Urban soils can be contaminated by heavy metals (such as lead and cadmium) and toxic chemicals from industrial activities and road traffic [

9]. Urban farmers often struggle with accessing sufficient water for irrigation. The urban setting means water is not always readily available for agricultural use, especially during dry seasons or in arid regions [

10]. Also, the proximity of crops, animals, and dense human populations can facilitate the spread of pests and diseases, affecting yield and food safety. Humid conditions and stagnant water, common in urban farming areas, can encourage the proliferation of disease vectors such as mosquitoes. [

11].

1.2. Aims and Objectives of the Study

The research investigates UA’s Psychosocial association with farmers, consumers, and city dwellers. This study attempts to answer the following question: What motivates the maintenance of UA in African cities, specifically in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam, in terms of health-related aspects? This includes its spatial distribution, socio-economic and psychosocial benefits, its effect on community health, and how architectural design could enhance its practice.

The central idea of this study is that, through thoughtful urban planning and architectural design incorporating UA, it is possible to achieve a more equitable spatial, economic, and social distribution of the psychological well-being benefits associated with this activity. To achieve this, the study analyzes the relationship between UA outcomes and farmers’ psychological well-being [

12], highlighting the positive association between UA and urban women farmers life [

13].

Therefore, the project is structured around four primary objectives. The first two objectives will be explored through a literature review, while the last two will be studied by analyzing primary data collected in the field. The objectives are presented in the following sections.

1.2.1. UA Mapping

The initial phase involves a comprehensive mapping of UA, grounded in a literature review from a global perspective to a more localized focus. This review will explore prevalent farming locations within urban settings, progressively narrowing from an international scope to specific insights on Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and ultimately, Togo and Tanzania.

1.2.2. Assessment of UA Benefits and Challenges

The second objective includes examining the benefits associated with UA, as identified through existing literature. This assessment will highlight the positive outcomes of UA practices and acknowledge and explore potential disadvantages, offering a balanced view of UA.

1.2.3. Association between Psychosocial Element and UA

The third aspect of the study, which is one of the pillars of this research, delves into the psychosocial effects UA has on UA farmers. This investigation investigates how engagement in UA activities influences social well-being and psychological health.

1.2.4. Architectural and Urban Planning Contributions to UA

Finally, as another pillar of the study, the project seeks to illustrate how architectural design and urban planning strategies can enhance the spatial distribution of UA and amplify its benefits. This objective will explore the potential of design and planning to optimize the integration of UA into urban landscapes, thereby closing the loop on the study’s comprehensive examination of UA in this research.

1.3. Literature Review

1.3.1. UA Mapping

UA, circumscribed in this study as any cultivation activity producing food or animal husbandry within an urban and peri-urban spatial perimeter [

14], is an increasingly popular practice worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) attests that UA and associated businesses employ 200 million individuals, playing a role in feeding 800 million people residing in urban areas [

15]. It is also reported that in African nations, approximately 40% of city residents participate in agricultural activities, a figure that increases to 50% in countries across Latin America [

15]. In Africa, this activity has specific characteristics, such as using vast tracts of land and its role as a source of income, particularly for women [

16], thus contributing to food security and the population’s health.

UA in Greater Lomé, the capital of Togo, and Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, illustrate the potential and challenges inherent in this practice [

17]. In Greater Lomé, as early as the first Master Plan in 1981, UA was somewhat generalized by being included in “green spaces,” with 15 to 20% of the population engaged in this activity, over 50% of them women, using UA for land conservation, sale, and household food [

18,

19]. Although urban planners in Greater Lomé recognize UA, their commitment seems lukewarm; Grand Lomé’s Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement Urbain 2019-2030 did provide for Zones d’Aménagement Agricole (ZAA), but inconsistencies in the 2020 document reveal a particular neglect of UA. In Dar es Salaam, the 2012-2032 Master Plan was preserved and planned for urban and peri-UA, recognizing its importance as far back as the 1979 plan. However, as in Greater Lomé, 60% of the population practice UA, with a majority of women, despite the difficulties. UA products are even integrated into the local cuisines of both cities, testifying to their cultural and economic importance [

20,

21].

These observations underline the crucial importance of in-depth research designed to optimize UA’s benefits while mitigating its drawbacks [

22]. Future studies must focus on strategies to overcome the challenges of integrating UA into urban planning, resource access, and institutional recognition [

23,

24]. By adopting an approach that values UA, cities like Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam can not only feed their populations sustainably but also foster social and economic inclusion, particularly for women who play a leading role in this activity [

25].

Given these findings, it seems necessary to find strong arguments to support the practice of UA, given that its benefits could be exponential if well conducted. To demonstrate that UA contributes to the psychological well-being of farmers through the income it generates [

26], in particular by empowering women farmers, and to show that urban planning and architecture can contribute to a better spatial distribution and thus to a more even economic and social distribution of the benefits linked to psychological well-being.

1.3.2. UA Benefits and Drawbacks

UA is an essential component of cities’ socio-economic and environmental fabric worldwide, particularly highlighted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) for its multiple contributions to food security, income generation [

27], and improved public health. In Africa, this activity is distinguished by its specific features, notably the size of the cultivated areas and its predominant role in the household economy, with significant participation by women. These characteristics underline the importance of UA not only as a means of subsistence but also as a vector for sustainable urban development [

28].

However, despite the recognized advantages of UA, notable drawbacks have been identified, particularly in Africa, where the practice of UA has mixed effects on the health of farmers, consumers, and urban residents. For example, although UA is widely hailed for its positive contribution to food security, it has been found that UA products can be harmful due to their pollution or toxicity [

29], as in the case of nitrates [

30,

31]. Studies and testimonies from the field reveal ambivalent relationship between UA and the health of farmers, consumers, and urban dwellers. On the one hand, UA is celebrated for its crucial contribution to food security and its access to fresh, nutritious produce (Smith, 2004). On the other hand, concerns about the pollution and toxicity of UA products, particularly nitrate contamination, highlight the potential health risks for consumers and producers.

However, despite these promising prospects, UA in Africa faces significant challenges that cloud its effectiveness and viability [

32]. In this complex context, exploring new ways to strengthen and justify the practice of UA in African cities becomes imperative. Beyond the economic and food benefits, this research aims to shed light on other motivations supporting commitment to UA. The aim is to unveil solid arguments for its development, particularly about the positive associations between UA and farmers’ psychological well-being and social cohesion within urban communities [

33].

1.3.3. Psychosocial Associations

Happiness is the subjective enjoyment of an individual’s holistic life [

34]. In 1850, Webster’s dictionaries defined happiness as a state of well-being characterized by relative permanence, by dominantly agreeable emotion ranging in value from mere contentment to deep and intense joy in living, and by a natural desire for its continuation (Oishi et al., 2013, p.1).

Science is often characterized by exploring phenomena that can be perceived, quantified, or evaluated. As a result, the concept of happiness seems elusive and intangible, and it is generally considered that the study of happiness is not proper scientific research [

36]. However, the term is increasingly used in international institutions’ documents to assess the quality of life in cities, countries, or continents with precise, quantifiable indicators [

37]. As a result, scientists have also begun to attach greater importance to this subject. The introduction of the scientific study of happiness made positive psychology in 2011 the most popular course at Harvard University [

38]. After an integrative literature review, the researchers Scorsolini-Comin and Santos (2010) underlined the relevance of the consideration of Subjective Well-being (SWB) in health studies. Therefore, Norrish and Vella-Brodrick (2008) argue that studying happiness is a valid scientific topic, exploring how increasing happiness can help improve physical, mental, and social health.

Morris (2012) also believes that studying happiness as a science, whether drawn from evolutionary theory and neuroscience psychology or biology, psychosomatic and psychosocial medicine, cybernetics, and sociobiology [

40], is paramount to making appropriate public policy decisions. He adds that for happiness to be a scientific indicator, we must consider its hedonic definition. He argues that “part of the importance of a well-founded science of happiness derives from the promise it offers of facilitating more effective decisions about public policy and social organization” (Morris, 2012, p. 1). Helliwell et Aknin (2018) even argue for a “social science of happiness” that makes an empirical study of the subject and enables strong links between researchers and policymakers. In their article entitled “The Science of Happiness for Policymakers: An Overview, the authors also attest to how many scientists are calling for scientific measures of happiness to become an integral part of policy decisions and their recommendation to conduct interdisciplinary research on the subject [

42]. This is how the measurement of subjective well-being and happiness comes into play in this research, consisting of the farmer’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives [

43,

44].

Is also gradually seen in the introduction of happiness or well-being measurement in spatial planning research as part of the improvement of public health [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. Moreover, positive psychology and happiness studies motivate interdisciplinary research, creating policy and practice implications and recommendations [

50]. The linear regression performed by Baschera and Hahn (2022) showed that urban planning predicts happiness and well-being. These include time use perception, community vitality, ecological diversity and resilience, and living standards. The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) is often used to adequately study wellbeing. [

51,

52,

53].

The study focuses on several main areas. Firstly, it seeks to precisely identify the psychological health advantages and disadvantages associated with the practice of UA in African urban contexts, emphasizing the risks of pollution and toxicity of agricultural products. Secondly, it aims to demonstrate how UA can contribute to the psychological well-being of farmers, notably by empowering women through income generation and the acquisition of greater economic and social autonomy. This part of the research focuses on how the income generated by UA can positively influence the psychological state of farmers, offering them prospects for improving their quality of life and that of their families [

54].

1.3.4. Architectural Design and Urban Planning Can Improve Spatial Distribution

Finally, the study proposes to explore the potential role of urban planning and architecture in optimizing the practice of UA. The idea involves rethinking urban spaces in such a way as to integrate UA areas harmoniously, creating environments conducive to the health, biodiversity, and resilience of urban communities [

55,

56,

57]. It will be possible to see whether the space’s design can affect the happiness or well-being of its users, whether through the practice of activity or simply the time spent there [

58].

Integrating UA into urban planning and architectural design can promote a more balanced spatial distribution and a homogenous economic and social distribution of the benefits associated with psychological well-being. This research aims to understand better why UA should be maintained and promoted and how urban planners and architects can contribute to spatial planning and holistic design to maximize its benefits. Expected outcomes include the number of urban farmers surveyed, the correlation between UA income and farmers’ psychological well-being, a new perspective on the positive association between UA and urban women farmers, and a spatial analysis of UA and farmers’ psychological well-being.

2. Methods and Materials

The study is part of an inter-institutional and interdisciplinary project, with health as a common theme. This empirical research deals with spatial planning, UA, and psychological health. This study, therefore, applies various methods to bring out the involvement of these three fields in the research and the subject dealt with. The study sites are Greater Lomé, the capital of Togo, and Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania.

The same research protocol was adopted for both cities at virtually the same time for two consecutive years.

2.1. Study Areas

2.1.1. Greater Lomé

Greater Lomé (Figure 5.1) is Togo’s capital and largest city, located southwest of the country along the Gulf of Guinea. It is Togo’s administrative, industrial, and commercial center and an important seaport in West Africa. The city is known for its lively market and features a mix of colonial and modern architecture, with palm-lined boulevards and accessible beaches. Greater Lomé remains a vibrant, welcoming place, reflecting Togo’s rich culture and diversity.

Figure 5.

1. The city of Greater Lomé, Togo in Africa.

Figure 5.

1. The city of Greater Lomé, Togo in Africa.

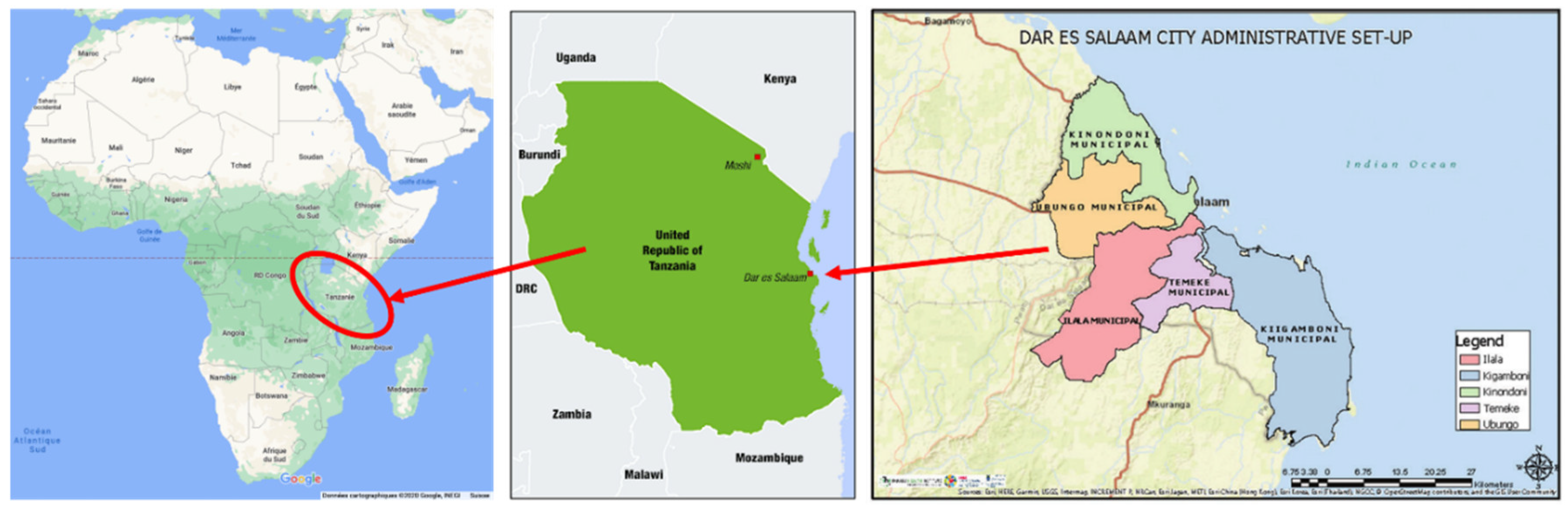

2.2.1. Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (Figure 5.2) is Tanzania’s largest city and main economic center, although Dodoma is the official capital. Situated along the east coast of Africa, on the shores of the Indian Ocean, Dar es Salaam is a vibrant, cosmopolitan hub that serves as a gateway to the islands of Zanzibar and the country’s safari national parks. Historically a small fishing village, the city has been overgrown to become a fascinating blend of cultures, architecture, and traditions.

Figure 5.

2. The city of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in Africa.

Figure 5.

2. The city of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in Africa.

Both cities are UA headquarters and have two major characteristics in common: the ports and the fact that they are both from Sub-Saharan Africa.

2.2. Data Collection

In this study, psychological well-being is treated as a continuous variable. The multidimensional approach provides a nuanced understanding of specific objectives.

According to the UNDP, 68% of the population of six Tanzanian cities practice UA. (De Bon et al., 2010) Several other estimates have been published, but the one that will be considered at this stage of the study is the UNDP estimate. In addition, mixed data from the literature and the researcher’s experience and observation of at least 15% of the population of Greater Lomé practicing UA and the application of the formula:

Where ‘s’ is the minimum sample size required to obtain significant results for a given event and risk level, ‘c’ is the Z score = 1.96 for a 95% CI., ‘p’ is the probability of occurrence of the event in %, and ‘e’ is the margin of error = 5% [

59].

2.2.1. UA field Types in Cities

Due to logistical constraints, the research strategy required targeting locations where a significant concentration of farmers could be reached simultaneously for questionnaire distribution. Consequently, any land cultivated by an individual for personal consumption, business, or both was identified as a critical data source. For this study, such cultivated land is called “farms.” The selection of study sites involved a process of spatial stratification, using administrative subdivisions to establish two distinct spatial strata based on a municipality/neighborhood gradient. Given the discrepancies between existing mapping data and actual conditions, preliminary site visits were conducted. These exploratory visits enabled us to gather the opinions of data collection supervisors in Greater Lomé and UA managers in Dar es Salaam to validate the selection of zones. Finally, seven areas in Greater Lomé and fifteen in Dar es Salaam were selected for inclusion in the study. This final selection encompassed intra-urban and peri-urban regions surrounding the two cities, providing a comprehensive view of the UA landscape.

2.2.2. Duration and Data Collectors

Given the time constraints, the research is a cross-sectional study. This cross-sectional study data collection which was carried out in March 2022 in Greater Lomé and March 2023 in Dar es Salaam, very early in the morning until noon at the latest, provided a detailed overview of the conditions present during these specific periods. At these times, the team was sure to find farmers in their fields.

The surveys of urban farmers were quantitative. They were administered by young urban planners from ARDHI University and the University of Greater Lomé, who received specialized training for this task. The interviewers used the KoBo toolbox for data collection in difficult areas. Each interviewer used a tablet to conduct the survey and geolocate completed questionnaires offline. Data collectors were recruited and trained to go into the neighborhoods of the target areas in the cities and distribute the questionnaire to the farmers.

Following research ethics approval, a strategic approach was adopted to carry out this work, involving recruiting and training skilled data collectors. These individuals embarked on a hands-on sampling expedition in targeted neighborhoods of the respective cities, engaging directly with local farmers using tablets installed with Kobotool boxes.

Five municipalities were selected in Dar es Salaam, and three sizeable urban farming zones were chosen in Greater Lomé.

2.2.3. Characteristics of Farmers

The leading players in the UA sector are growers, traders, retailers, and consumers. Focusing specifically on producers, UA managers engaged with growers in three distinct horticultural activities, resulting in a representative sample across five municipalities. The approach targeted the origins of production to assess the association between UA and urban health, namely the agricultural fields and the farmers themselves. These producers are classified into primary operators, employees, or volunteers. The strategy consisted of spontaneously approaching people engaged in farming activities in the study area without prior selection. During the engagement, people were asked about their ownership of a UA field.

2.3. Using the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF)

Measuring a person’s psychological well-being is an ambitious objective that requires appropriate tools in a scientific context. As this study could not be carried out on a cross-sectional basis, a standard questionnaire such as the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) was chosen for this purpose. The MHC-SF is a 14-item assessment tool designed to evaluate three aspects of well-being: emotional, social, and psychological. All three are sub-grouped into two types: emotional mental health (hedonic) and positive functioning. This tool comprises questions about farmers’ state of mind over the past month. It is protected by copyright [

60]. However, its use is authorized without prior consent from the authors, provided the source is referenced correctly [

60]. The tool is a self-administered questionnaire that can be used on paper, face-to-face, or by telephone. It is available in English, French, and at least six other translated languages. It is available in English, French, and at least six other languages. It can be used for adolescent and adult populations. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the MSF is 0.96, and according to George and Mallery (2003), a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient > 0.9 is excellent. [

61].

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Standard Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) Questionnaire

The table includes various data arranged in geographical coordinates (latitude, longitude, altitude), answers to questions on psychological well-being following the standard Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) questionnaire, and other direct questions assessing perceived well-being (e.g., “happy,” “interested in life,” “satisfied with life.” Demographic and socio-economic information, such as age, gender, household income, and farmers’ birthplaces where concerned, was also collected, and presented in the table. Some variables were then converted into appropriate numerical formats to facilitate analysis.

Here is a summary of some critical aspects of the data:

Psychological well-being variables: Responses generally range from 0 to 5, probably indicating a Likert scale [

62] to measure agreement or satisfaction with different aspects of well-being.

Demographic and socio-economic data: Age, gender, household income, and whether respondents were born in the city.

Geographical data: Latitude and longitude are provided for each observation, enabling spatial analysis.

Duration of activity in the city: This variable indicates how long farmers have practiced UA, with values ranging from 1960 to 2023.

2.4.2. Data Analysis Materials

The methodology used to analyze the data involved several stages. After coding in Microsoft Excel 16, descriptive, inferential, predictive, and spatial analyses were performed using Python. The data was cleaned, coded, and analyzed with Python using the libraries:

- -

Pandas: for data handling and cleansing.

- -

NumPy: for basic mathematical operations and array manipulation.

- -

Matplotlib: for data visualization creation, such as graphs and charts.

- -

Seaborn: for more advanced and aesthetically pleasing visualizations of statistical data.

- -

ScipyStats: for advanced statistics, such as correlation tests.

- -

Scikit-learn: for predictive modeling and machine learning, especially cluster analysis.

- -

GeoPandas: for working with geospatial data.

QGIS 3.32.2-Lima was used to visualize data in more detail. Results were interpreted and translated into writing in this paper.

2.4.3. Descriptive, Inferential, Predictive, and Spatial Statistics

Descriptive statistics were performed to provide information corresponding to the analysis of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF) emotional (hedonic) and positive functioning items. This information includes the same variables’ mean, median, and standard deviation.

In addition to the descriptive statistics used to summarize the characteristics of the data analyzed, the relationships between the psychological well-being target variable and the other explanatory variables were examined. The correlation is bivariate. The MHC-SF matrix was also used to deepen the analysis of psychological well-being.

A logistic regression analysis is more suitable for the study because the dependent variable is categorical (e.g., happy vs. not happy). The aim is to examine how specific factors (such as UA income, gender, or city) affect a farmer’s probability of being happy (a binary variable).

A mixed approach is used to assess the correlation between the general variable of mental well-being and the other variables, as some of these variables are categorical and others are numerical.

- ∘

Pearson correlation [

63] for numerical variables such as “Household members count” and “How long have you been farming fields or raising animals in the city?”.

- ∘

Spearman rank correlation [

64] for ordinal categorical variables, such as “Age range,” if data can be significantly ordered.

- ∘

Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests [

65,

66] for categorical variables, such as “Sex” or “City.”

A spatial cluster analysis method applying the K-Mean algorithm was used to identify groups of farmers with similar psychological well-being profiles in every city globally.

Next, the geographical distribution of clusters within each city was visualized using maps to observe areas of high or low concentrations of psychological well-being. In addition to Python, QGIS 3.32.2-Lima was used to create grids over the layers of Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam map shapefiles, clip the grid with the polygon, and perform the spatial analysis with the points thanks to the QGIS “Research tools,” “Geoprocessing tools,” and “Data management tools.”

3. Results: UA and Psychosocial Well-Being and the Place of Spatial Analysis

3.1. Generalities about UA Outcome and Related Psychological Well-Being

3.1.1. Happiness among the Urban Farmers Population Studied

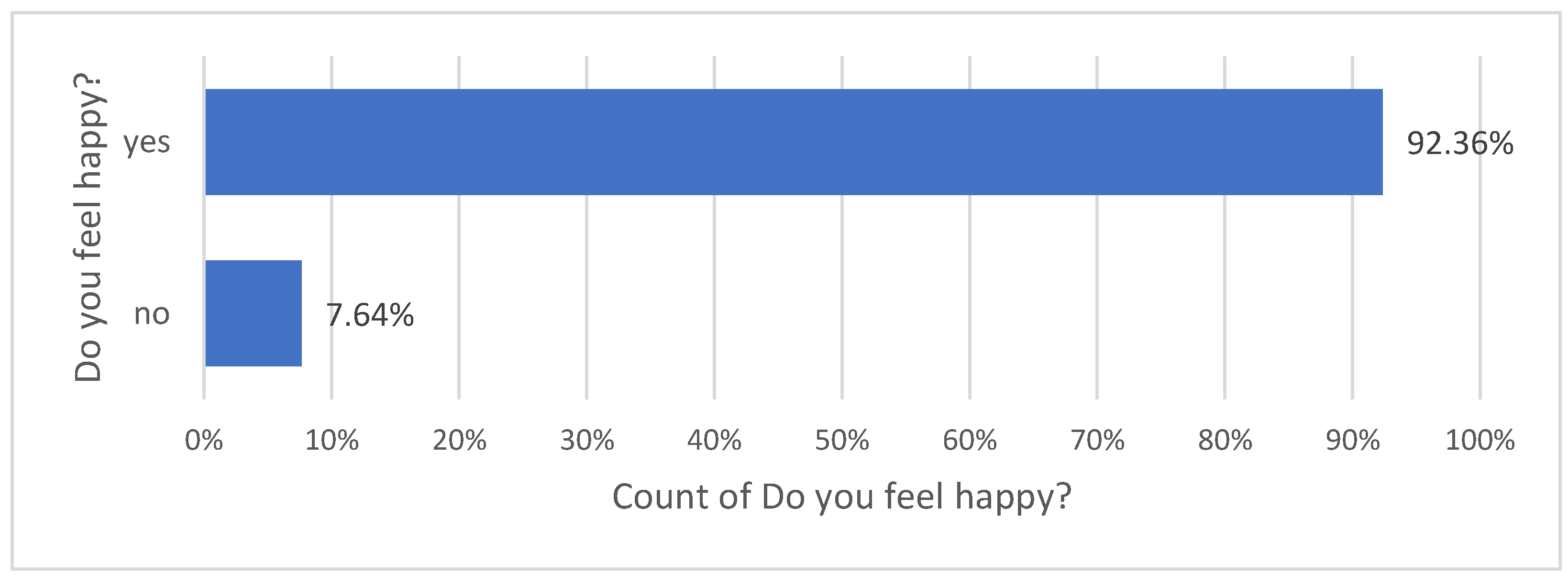

The graph (Figure 5.3) shows that 92.36% of urban farmers feel generally happy, while 7.64% do not, signifying a high prevalence of happiness among the urban farmer population studied.

Figure 5.

3. Perceived happiness among the urban farmers population studied.

Figure 5.

3. Perceived happiness among the urban farmers population studied.

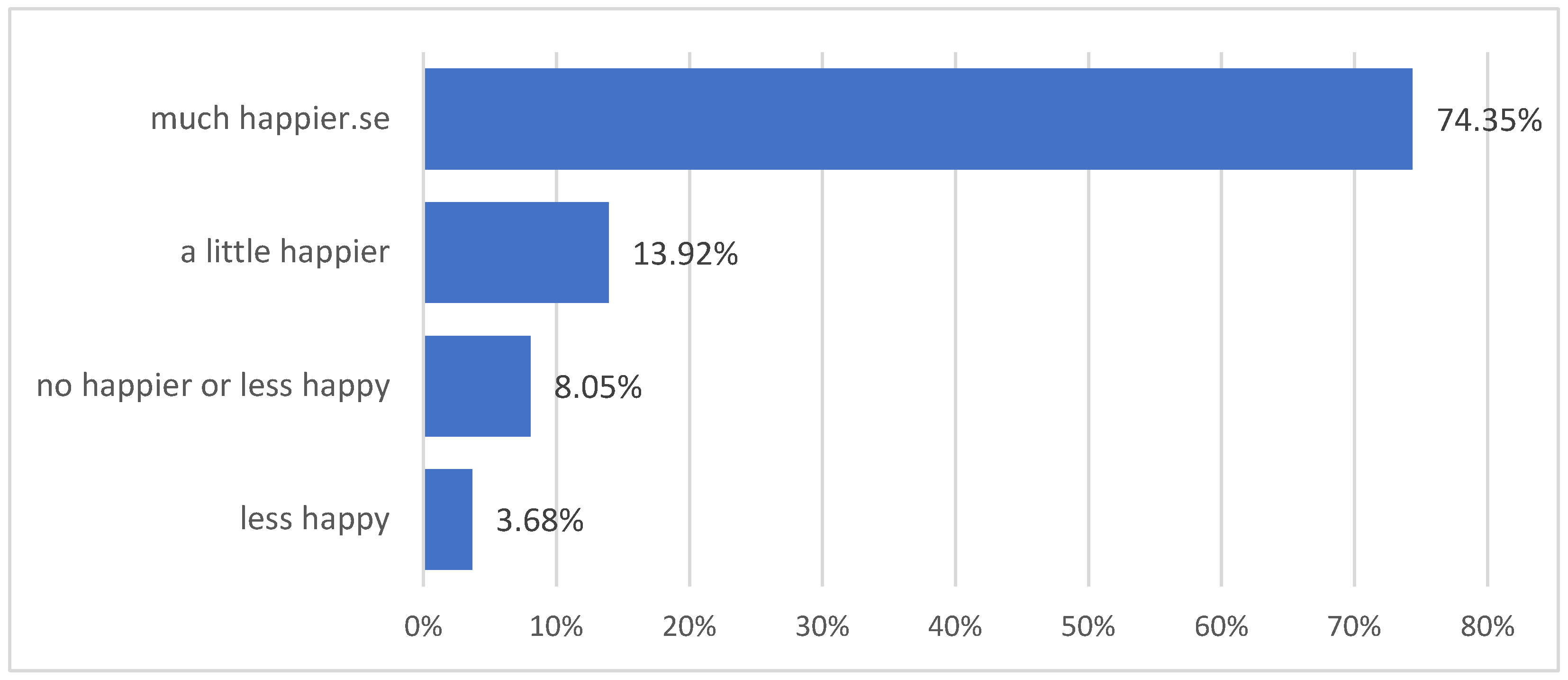

3.1.2. Happiness Among the Urban Farmers Population Studied since They Started Farming

This graph (Figure 5.4) shows that most farmers surveyed (74.35%) feel significantly happier since starting UA. Adding together, those who think “a little happier” represent almost 88% of respondents who think their happiness has improved due to UA. On the other hand, a minority (3.68%) feel less happy since starting UA, and around 8% have not noticed any change in their level of happiness.

Figure 5.

4. Perceived happiness among the urban farmers population has been studied since they started farming.

Figure 5.

4. Perceived happiness among the urban farmers population has been studied since they started farming.

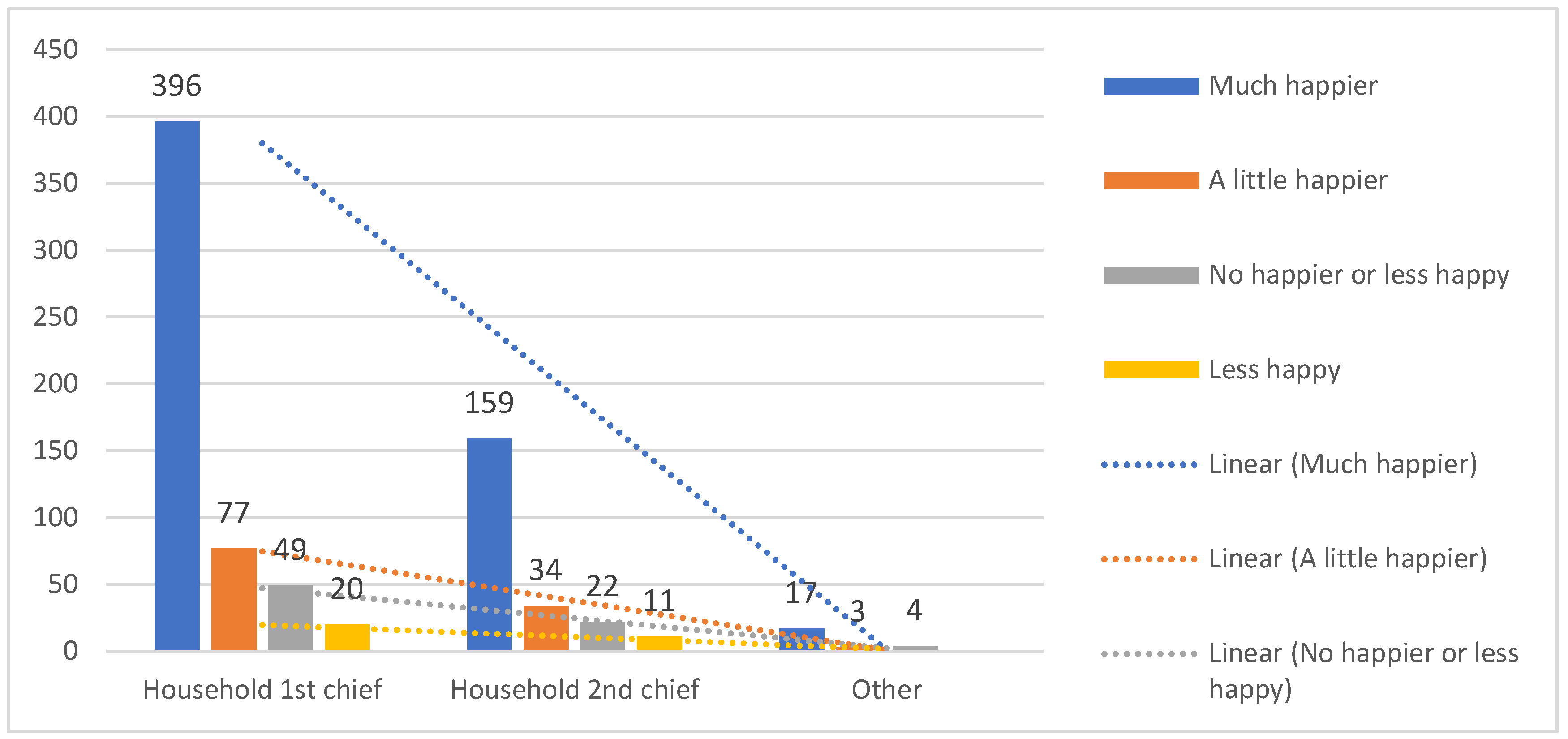

3.1.3. Level of Happiness Linked to UA and Household Position in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam

Figure 5.5 illustrates the distribution of farmers’ responses regarding their feelings of happiness related to the practice of UA according to their position in the household. The visualization and trend lines show that UA-related feelings vary among the different positions occupied within the household. The more farmers occupy the position of first head of household, the higher their perception of happiness linked to the practice of UA.

Figure 5.

5. Level of happiness linked to UA and household position in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam.

Figure 5.

5. Level of happiness linked to UA and household position in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam.

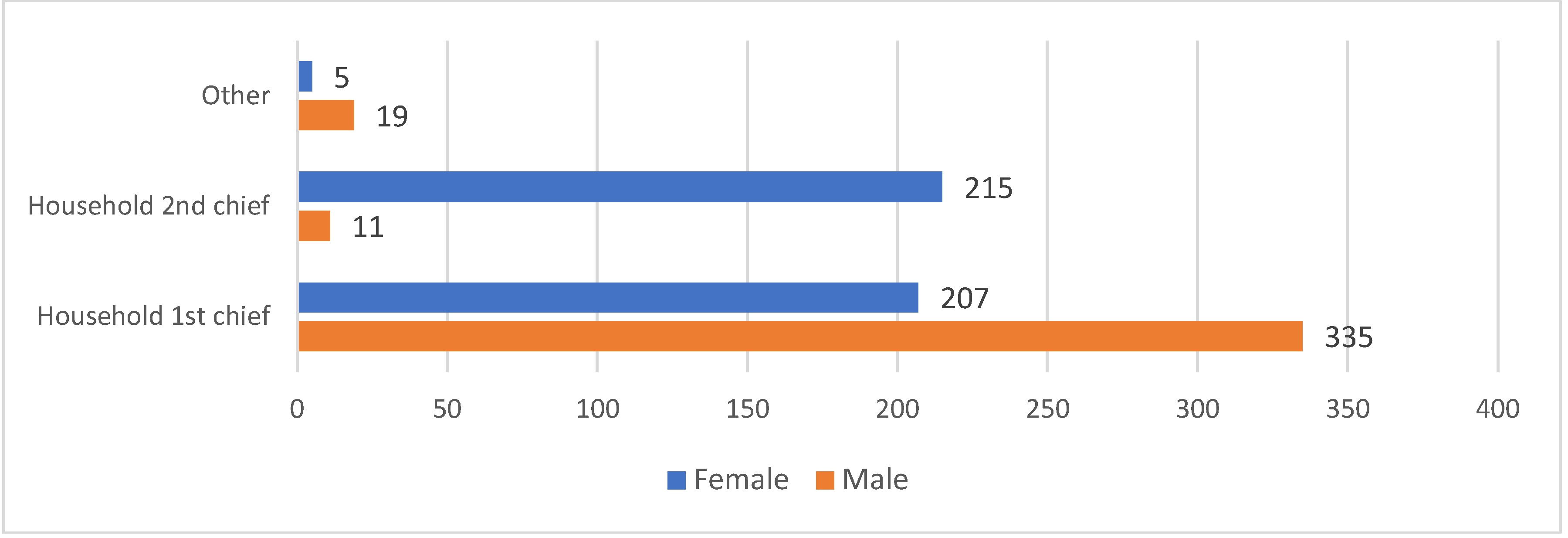

3.1.4. Sex by Household Position in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam

This distribution in Figure 5.6 gives us a visual representation of the gender distribution of the different roles within the household among the interviewees. It highlights the differences between the positions occupied by men and women in the study context. .

Figure 5.

6. Sex by household position in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam.

Figure 5.

6. Sex by household position in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam.

Slightly more than 1/3 of men farmers are first heads of household than women farmers.

For second heads of household, women are almost twenty times more numerous than men, and there are slightly more men than women in the “Other” category.

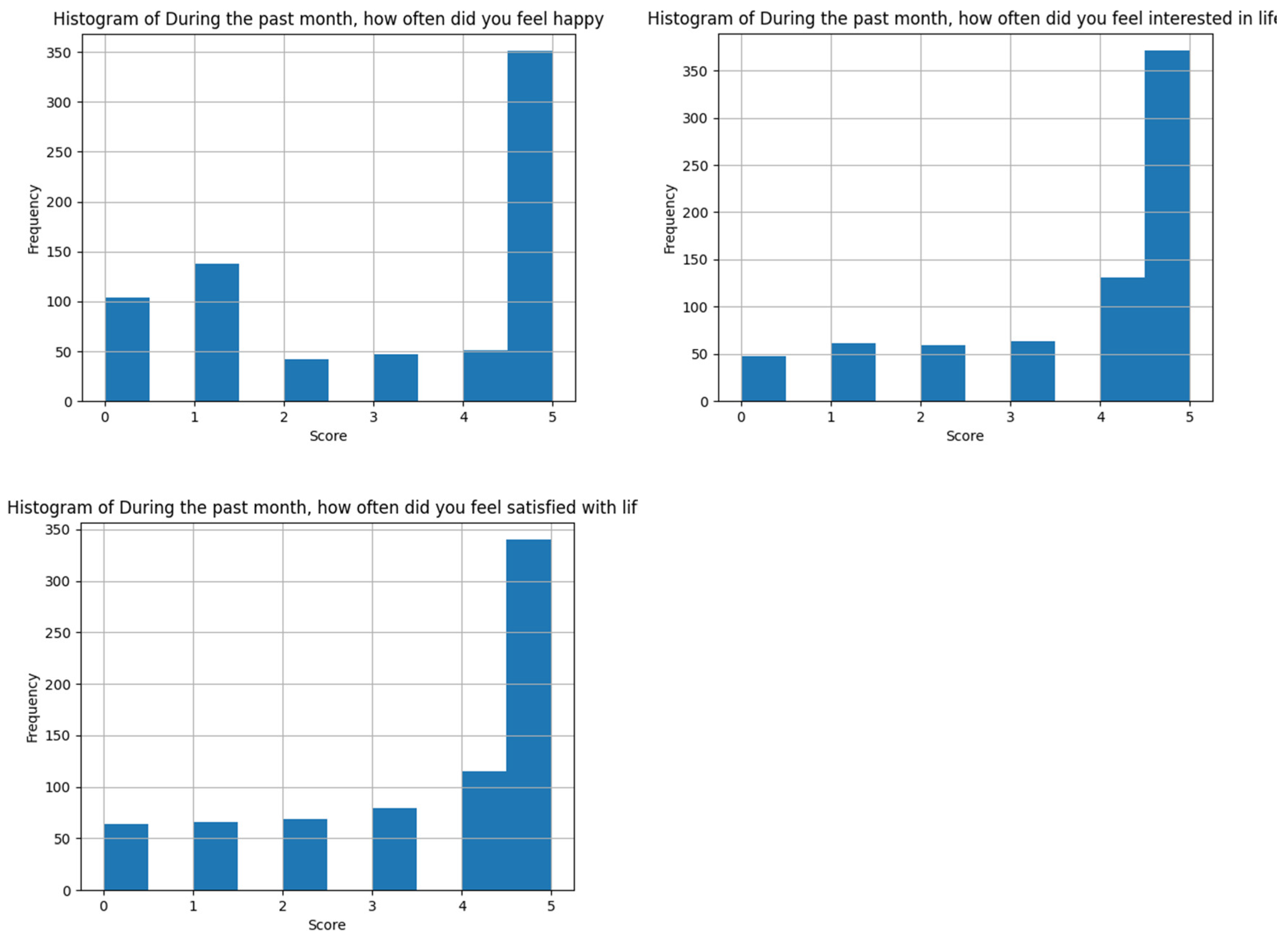

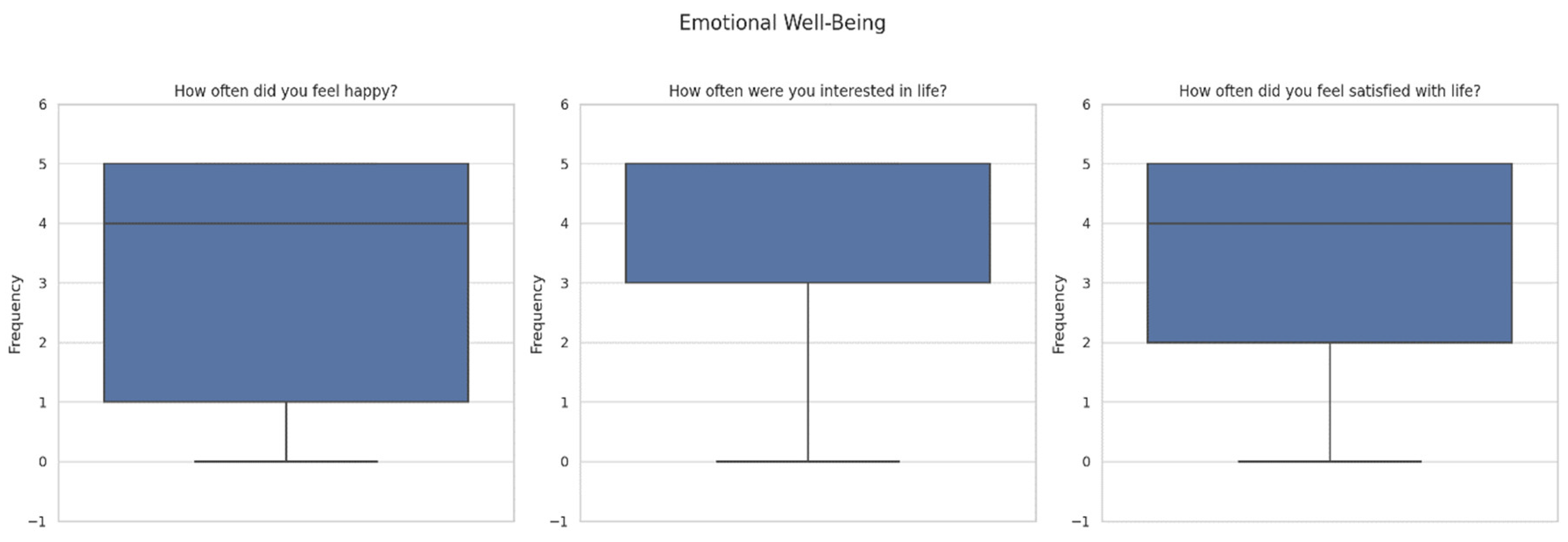

3.2. Measure of Emotional UA-Related ‘Well-Being’ Using the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF)

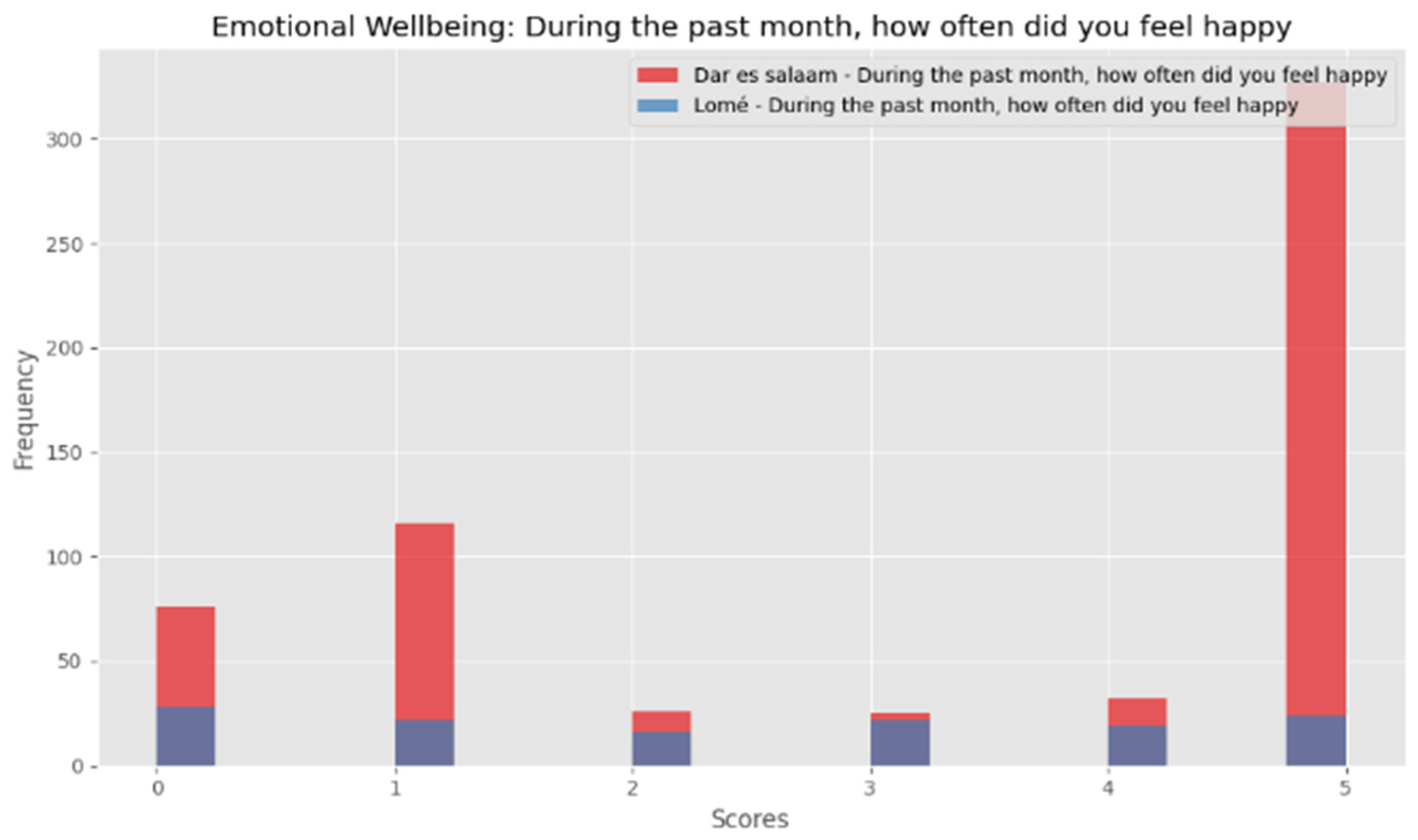

Table 5.1 and Figure 5.7 illustrate the Emotional Well-being results.

Table 5.

1. Urban farmers happiness.

Table 5.

1. Urban farmers happiness.

| |

During the past month, how often did you feel happy? |

During the past month, how often did you feel interested in life |

During the past month, how often did you feel satisfied with life? |

| count |

733 |

733 |

733 |

| mean |

3.167804 |

3.747613 |

3.548431 |

| std |

2.01238 |

1.628095 |

1.719198 |

| min |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 25% |

1 |

3 |

2 |

| 50% |

4 |

5 |

4 |

| 75% |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| max |

5 |

5 |

5 |

Figure 5.

7. Emotional well-being.

Figure 5.

7. Emotional well-being.

The outcomes show the following statistics for each of the questions asked to 733 farmers. Out of a total of 733 valid responses, the averages of the responses are 3.17 for the feeling of happiness, 3.75 for interest in life, and 3.55 for satisfaction with life, respectively, on a rating scale where 5 indicates high frequency. The standard deviation shows the variability of responses, with 2.01 for the feeling of happiness, 1.63 for interest in life, and 1.72 for life satisfaction, indicating a moderate dispersion around the mean. The minimum score for each question is 0, indicating that some respondents have never experienced happiness, interest in life, or satisfaction in the previous month.

25% or the top quartile of farmers rated their happiness at one or less, their interest in life at three or less, and their satisfaction at two or less. The median corresponding to 50% of respondents felt happy, interested in life, or satisfied with life, with a score of 4, suggesting a generally positive trend.

75% or the third quartile of farmers rated their sense of happiness, interest in life, and satisfaction with life at five or below, indicating a high level of these feelings.

The maximum score for each question is 5, showing that some respondents still felt happiness, interest in life, and satisfaction during the month.

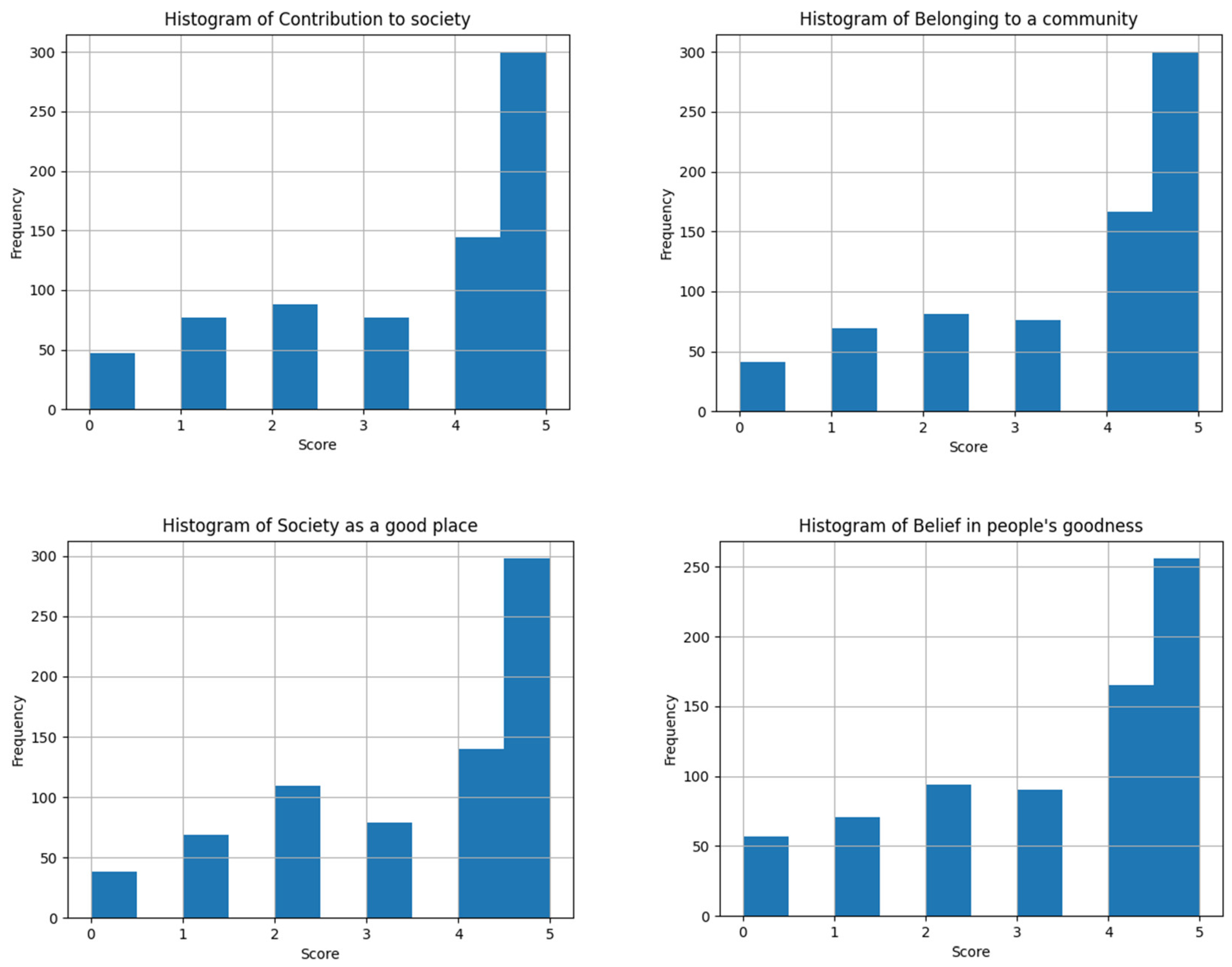

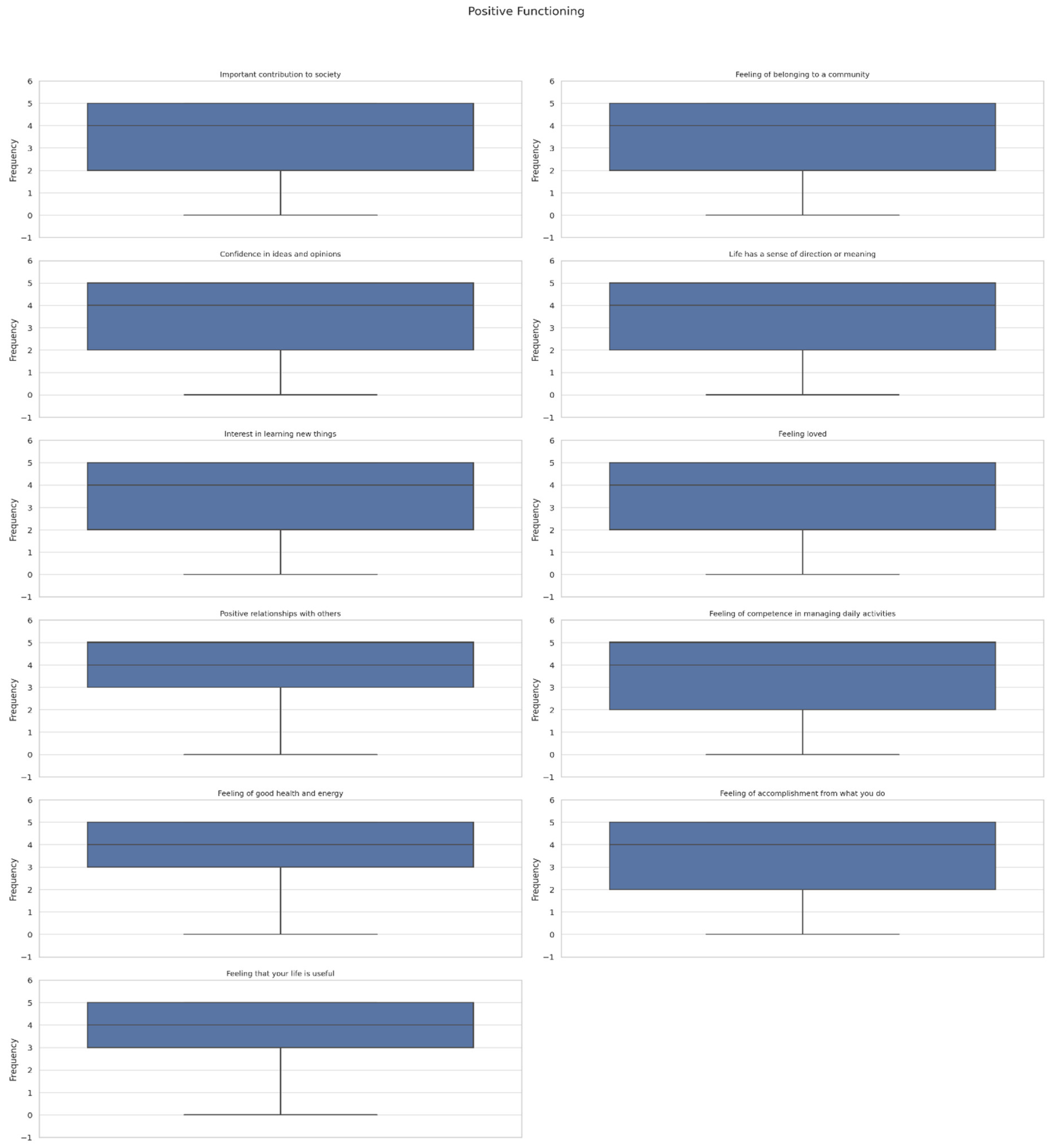

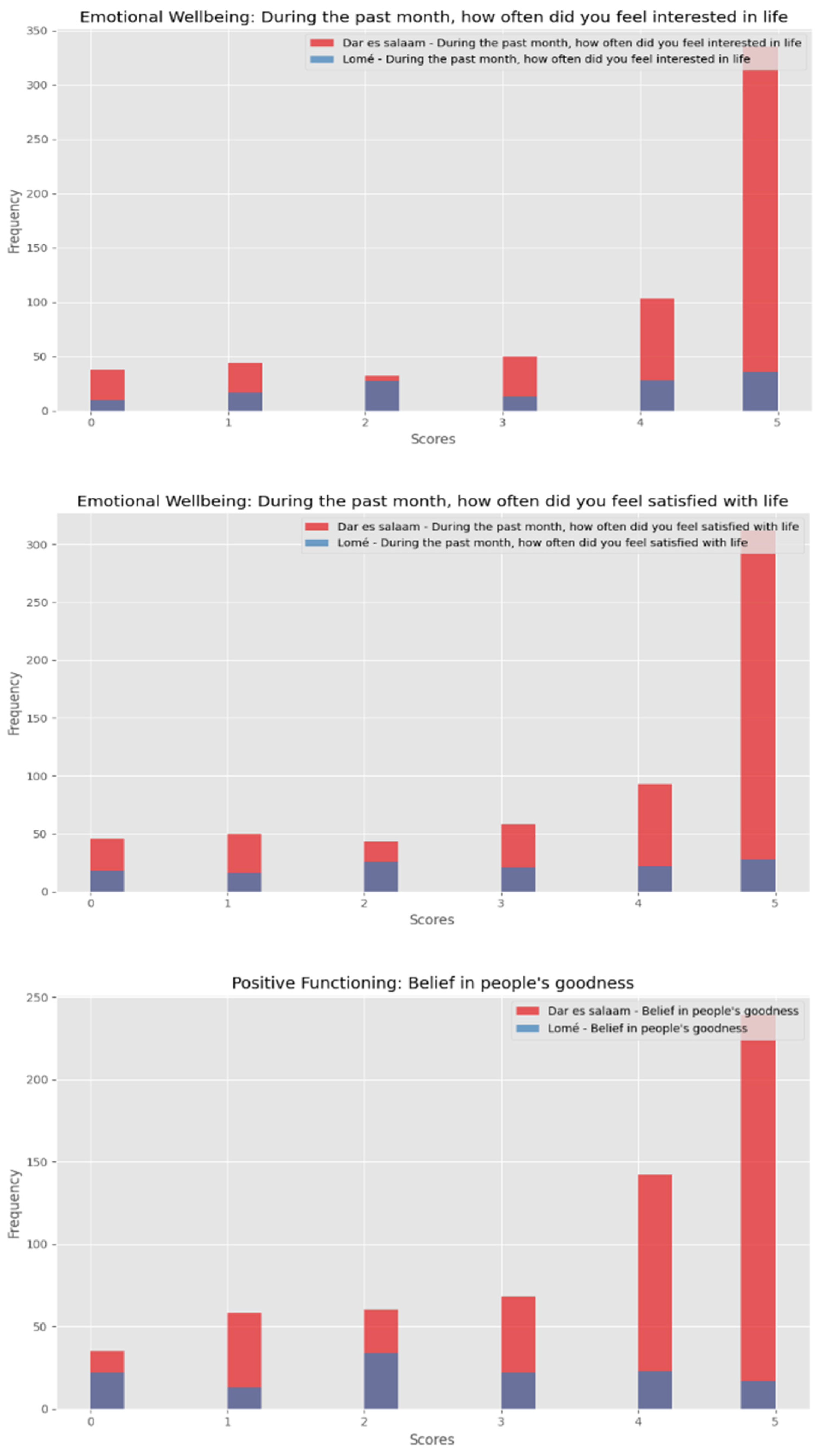

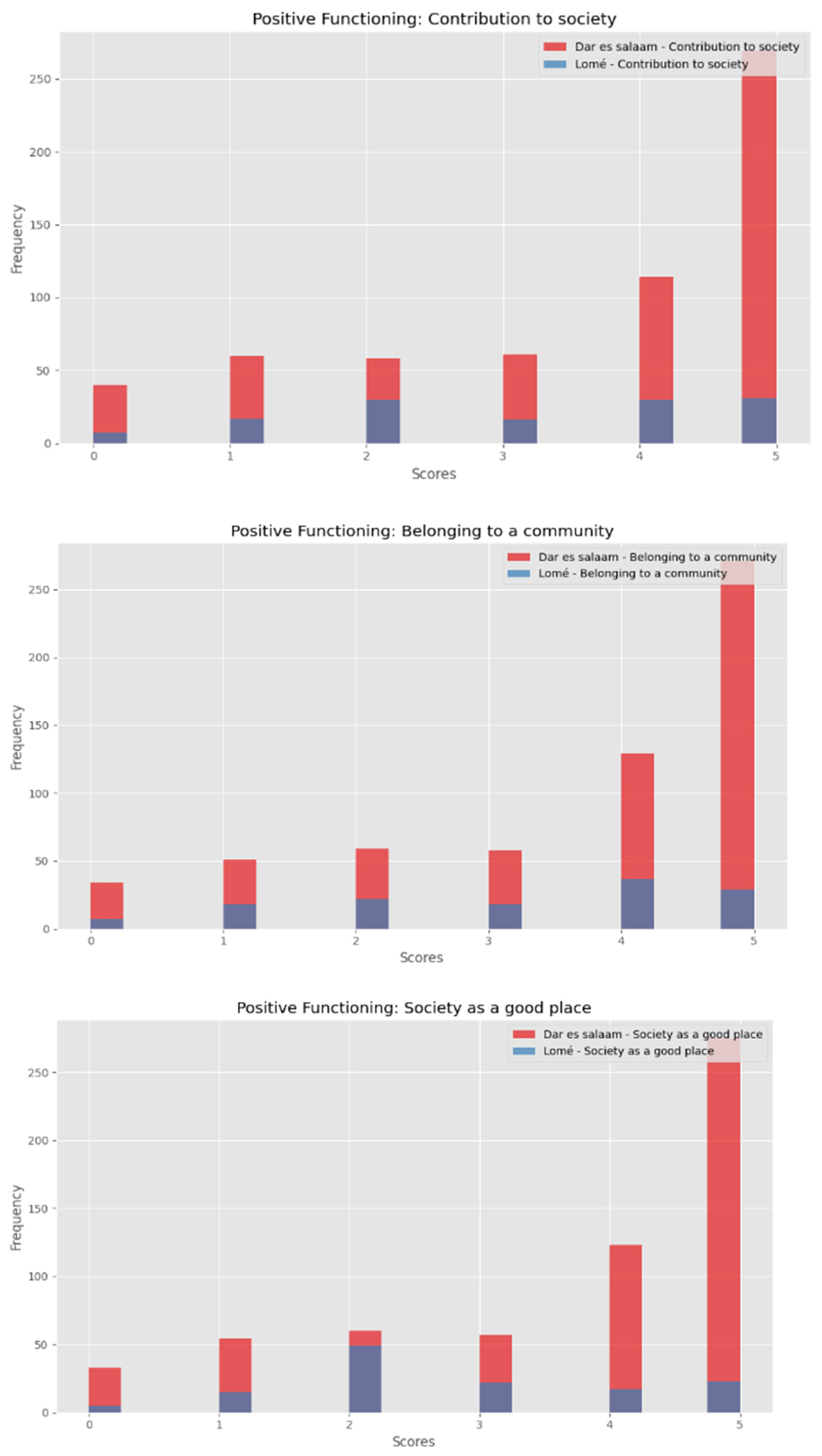

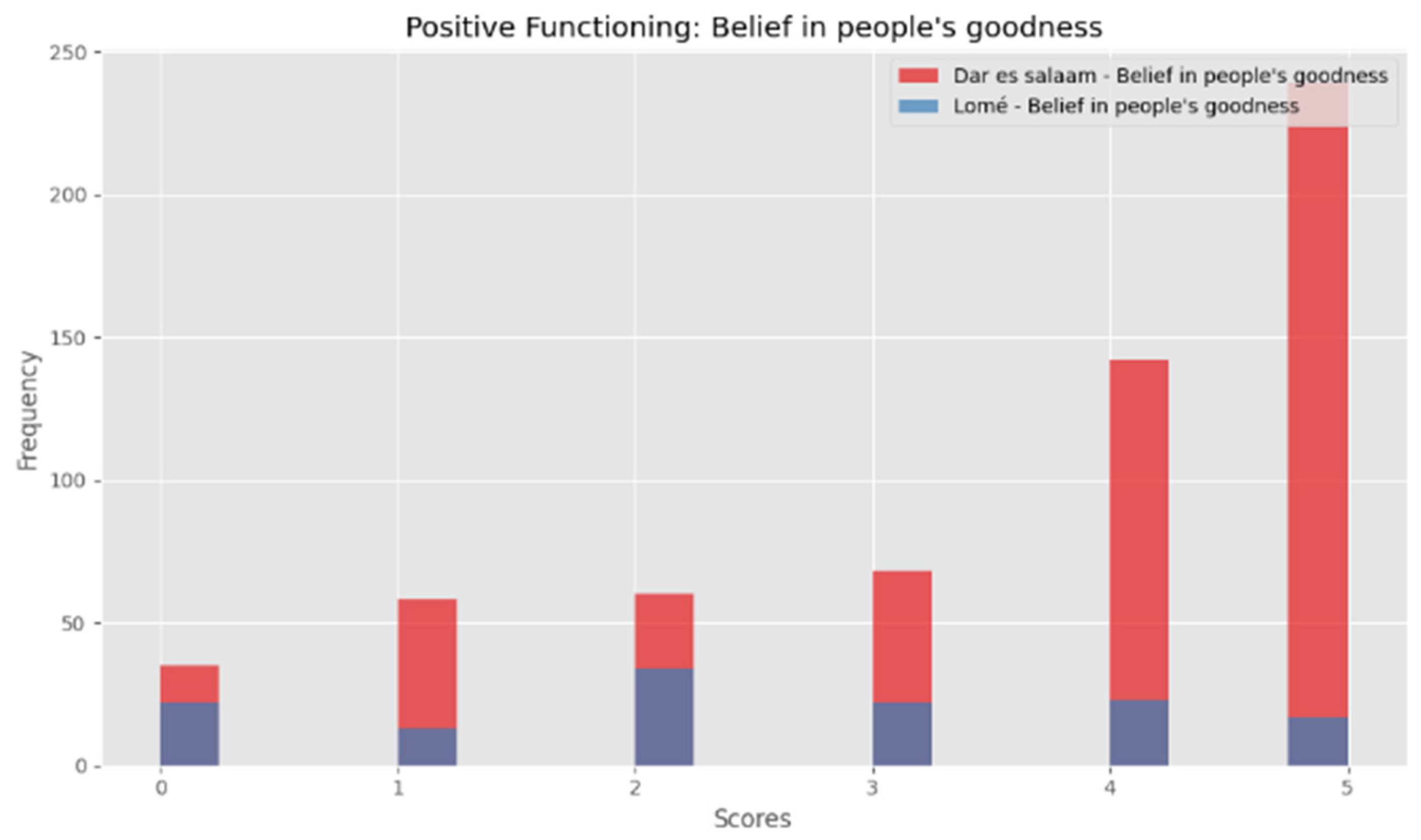

3.3. Measure of UA-Related ‘Positive Functioning’ Using the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF)

For Positive Functioning (Table 5.2 and Figure 5.8), means vary slightly across dimensions, with 3.49 for contribution to society, 3.58 for belonging to a community, 3.51 for perception of society as a good place, and 3.37 for belief in the goodness of people, indicating a positive evaluation overall. Standard deviations are relatively similar across the dimensions (around 1.59 to 1.65), suggesting moderate variability in farmers’ perceptions in the two cities. The minimum score is 0 for all questions, showing that some individuals do not positively perceive their relationship with society or the community.

Table 5.

2. Positive functioning table.

Table 5.

2. Positive functioning table.

| |

Contribution to society |

Belonging to a community |

Society is a good place |

Belief in people’s goodness |

| count |

733 |

733 |

733 |

733 |

| mean |

3.492496589 |

3.578444748 |

3.51159618 |

3.36834925 |

| std |

1.646825366 |

1.588353887 |

1.597107799 |

1.644890126 |

| min |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 25% |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| 50% |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| 75% |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| max |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

Figure 5.

8. Positive functioning.

Figure 5.

8. Positive functioning.

1/4 of respondents rated two or less, indicating that a quarter of individuals have a less positive perception or feel less integrated. The median of 4 for all questions reflects an overall positive trend, with most respondents feeling positively integrated and contributing. 75% of farmers have a rating of 5 or less, demonstrating high positive feelings towards their contribution and integration into society. The maximum score for each dimension is 5, indicating that some urban farmers feel strongly about their positive contribution to society, their belonging to a community, their positive view of society, and their belief in the goodness of people (Figure 5.8 - 10).

Figure 5.

9. Urban farmers' emotional well-being.

Figure 5.

9. Urban farmers' emotional well-being.

Figure 5.

10. Positive functioning of urban farmers.

Figure 5.

10. Positive functioning of urban farmers.

These results underline farmers’ generally positive perception of their role and place in society and their optimism about human nature and social improvement (Figure 5.10).

3.4. Comparison between the Two Cities Using the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF)

Generally, farmers in Dar es Salaam report higher levels of emotional well-being and positive functioning than those in Greater Lomé, as evidenced by the higher averages for almost all the questions assessed.

Residents of Dar es Salaam report feeling more interested in life and more satisfied with their lives, and they perceive their contribution to society and community more positively than those in Greater Lomé.

Responses concerning the perception of society as a good place and belief in the fundamental goodness of people also show variations between cities, with Dar es Salaam showing higher averages (Table 5.3 and Figure 5.11).

Table 5.

3. Comparison table between Dar es Salaam and Greater Lomé.

Table 5.

3. Comparison table between Dar es Salaam and Greater Lomé.

| 131 |

2.412214 |

1.809676 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

Greater Lomé |

During the past month, how often did you feel happy? |

Emotional Well-being |

| 602 |

3.895349 |

1.585294 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

Dar es Salaam |

During the past month, how often did you feel interested in life? |

| 131 |

3.068702 |

1.655717 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

Greater Lomé |

During the past month, how often did you feel interested in life? |

| 602 |

3.724252 |

1.673035 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

Dar es Salaam |

During the past month, how often did you feel satisfied with life? |

| 131 |

2.740458 |

1.703335 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Greater Lomé |

During the past month, how often did you feel satisfied with life? |

| 602 |

3.58804 |

1.65182 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

Dar es Salaam |

Contribution to society |

Positive Functioning |

| 131 |

3.053435 |

1.555699 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Greater Lomé |

Contribution to society |

| 602 |

3.677741 |

1.582707 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

Dar es Salaam |

Belonging to a community |

| 131 |

3.122137 |

1.539345 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

Greater Lomé |

Belonging to a community |

| 602 |

3.674419 |

1.591463 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

Dar es Salaam |

Society is a good place. |

| 131 |

2.763359 |

1.402372 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

Greater Lomé |

Society is a good place. |

| 602 |

3.563123 |

1.587231 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

Dar es Salaam |

Belief in people’s goodness |

| 131 |

2.473282 |

1.614017 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

Greater Lomé |

Belief in people’s goodness |

Figure 5.

11. Comparison between Dar es Salaam and Greater Lomé of Well-being variables.

Figure 5.

11. Comparison between Dar es Salaam and Greater Lomé of Well-being variables.

3.5. General Study about the Correlation between Psychological Well-Being and Other Variables

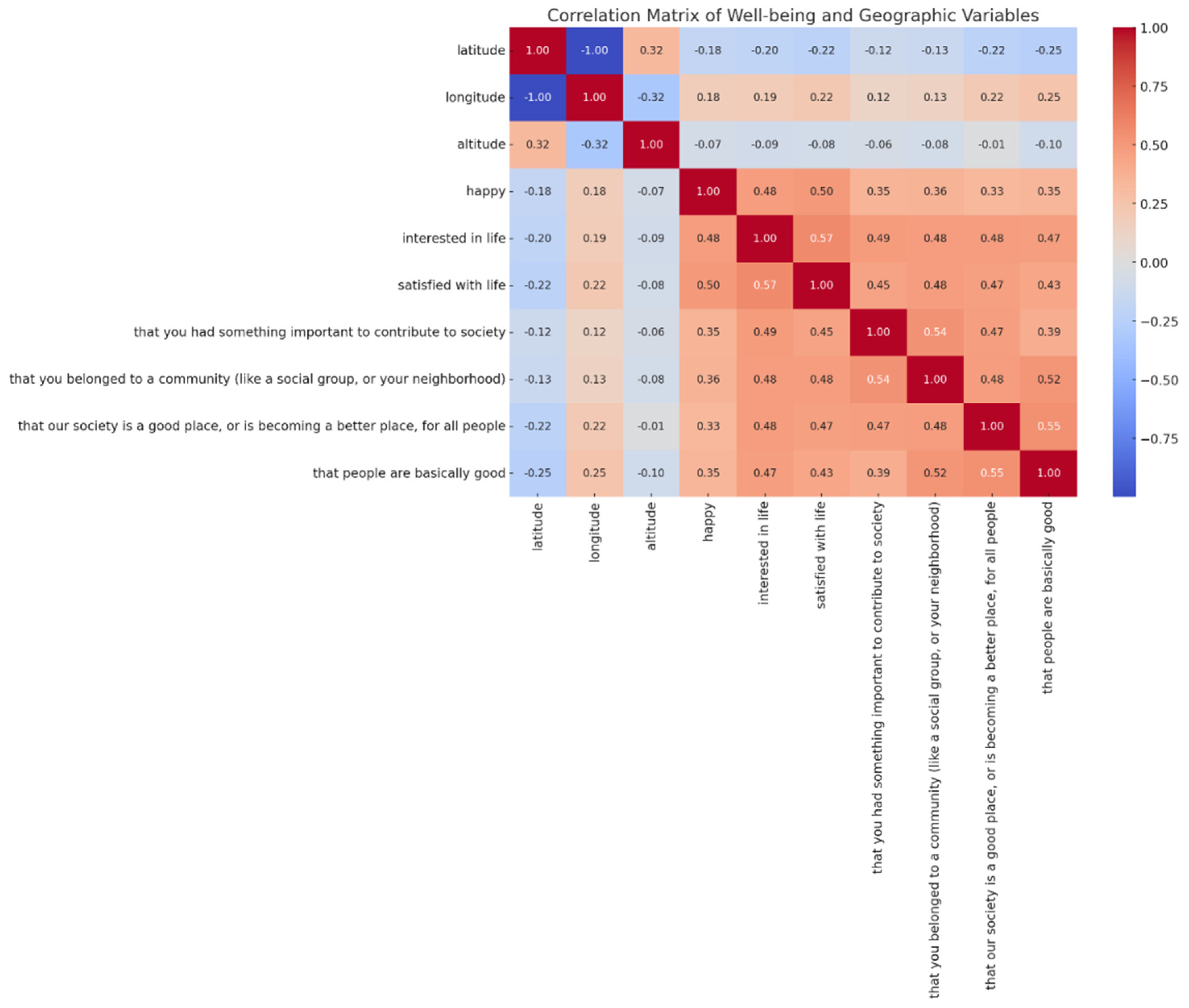

The correlation matrix (Figure 5.12) above shows the relationships between geographical variables (latitude, longitude, altitude) and the various measures of psychological well-being. Here are a few key observations:

Figure 5.

12. Correlation Matrix of Well-being and Geographic Variables.

Figure 5.

12. Correlation Matrix of Well-being and Geographic Variables.

3.5.1. Relationships between Well-Being Variables

Variables related to psychological well-being generally show positive correlations, indicating that respondents who tend to feel happy are also more likely to feel satisfied with life, interested in life, and positively perceive their contribution to society and belonging to a community.

3.5.2. Relationship with Geographical Variables within the Continent

Correlation coefficients between geographical variables (latitude, longitude, altitude) and measures of psychological well-being are generally low. The relationship supposes that there is no apparent direct link between farmers’ geographical location on the continent and their perception of psychological well-being, at least not at the level of granularity analyzed here.

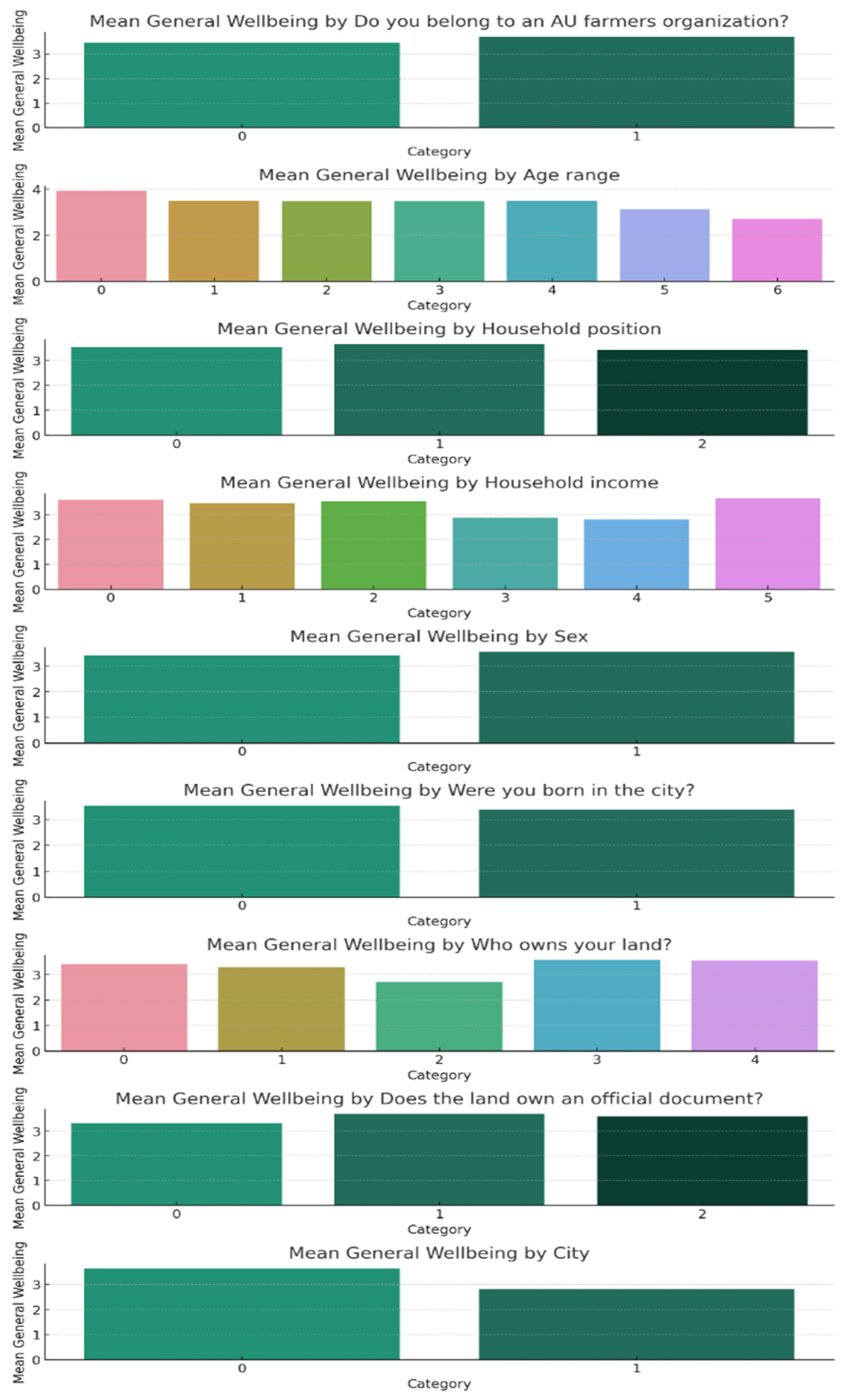

3.5.3. These Results Underline the Importance of Social and Personal Factors in the Perception of Psychological Well-Being Rather Than Specific Geographical Factors. Average Mental Well-Being by Category

The following bar charts (Figure 5.13) for the categorical variables show average mental well-being by category. There are differences in mean mental well-being between the categories of each categorical variable.

Figure 5.

13. Bar graphs showing average mental well-being by a categorical variable.

Figure 5.

13. Bar graphs showing average mental well-being by a categorical variable.

3.5.4. Relation to General Mental Well-Being

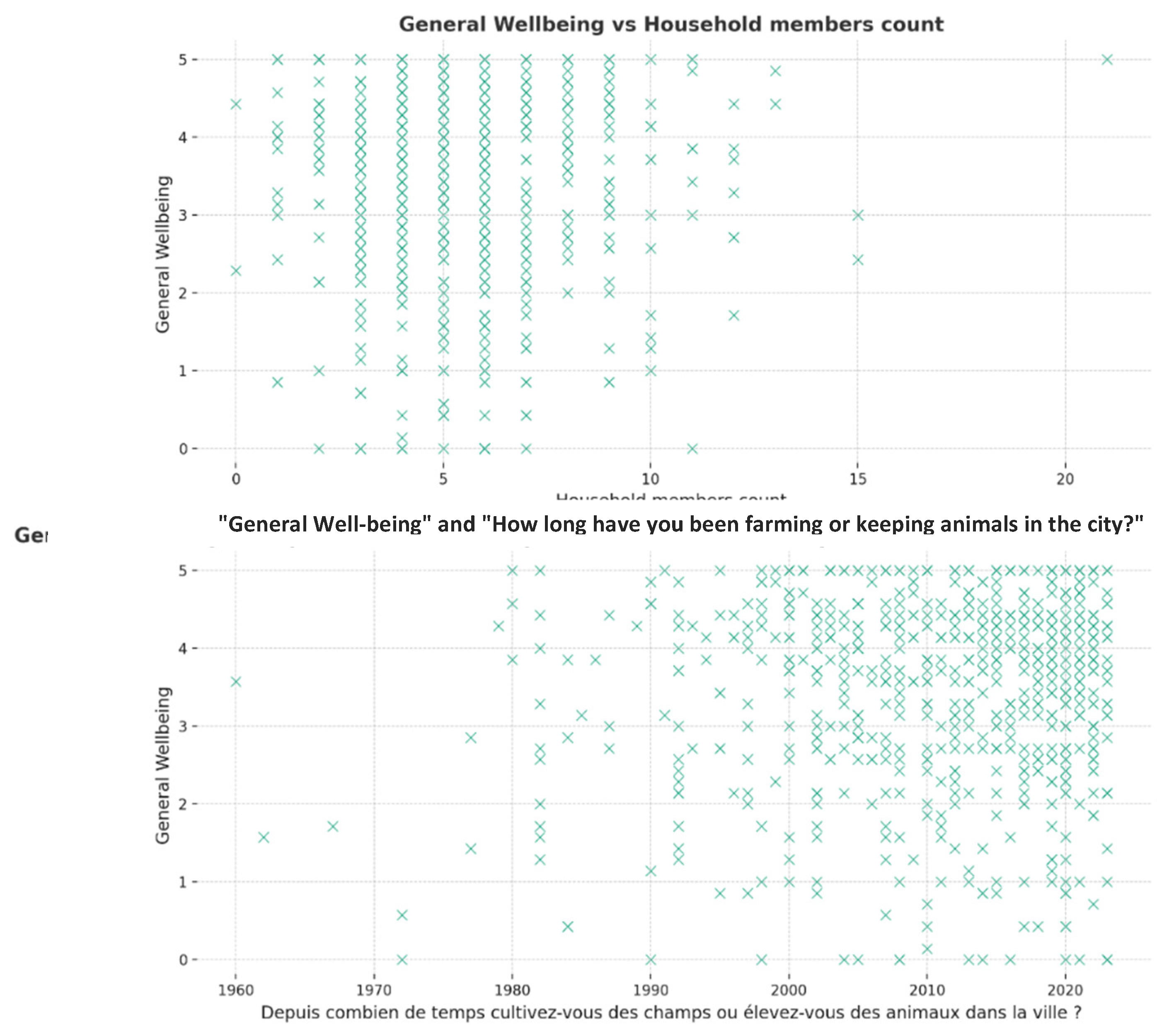

The first graph in Figure 5.14 shows the relationship between general well-being and the number of household members. The observed trend indicates that households of five (05) people report higher happiness.

Figure 5.

14. Scatter plot between “General Well-being” and “How long have you been farming or keeping animals in the city?”.

Figure 5.

14. Scatter plot between “General Well-being” and “How long have you been farming or keeping animals in the city?”.

Turning to the second scatter plot, which cross-references general well-being with length of involvement in UA, the data show that those who started farming after 2000 display more consistent happiness levels.

The results of the correlation calculations between the composite variable of general mental well-being and the other selected variables are as follows in the Table 5.4:

Table 5.

4. Correlation between general mental well-being and other selected variables.

Table 5.

4. Correlation between general mental well-being and other selected variables.

| Variable |

Measurement |

Correlation level |

| “Membership of an UA farmers’ organization.” |

0.043 |

Very low |

| “Age range |

-0.026 |

very low negative correlation |

| “Position in the household |

-0.068 |

low negative correlation |

| “Household income |

-0.100 |

low negative correlation |

| “Sex |

0.068 |

low positive correlation |

| “Born in the city |

-0.037 |

very low correlation |

| “Owner of the land” |

0.048 |

very low correlation |

| “Does the land have an official document?” |

0.081 |

low positive correlation |

| “City |

-0.281 |

moderate negative correlation, and the most significant of the variables examined |

The most notable correlation is with the “City” variable, suggesting that general mental well-being can vary significantly from one city to another. The other variables show weak correlations with general mental well-being. These results indicate that social and environmental factors may substantially influence mental well-being more than individual characteristics or economic factors. However, these correlations do not necessarily imply causality, and other unexamined factors could influence these relationships.

3.6. Statistical Analysis of Women’s Psychosocial Empowerment through UA-Related Well-Being Outcomes

3.6.1. Calculating Average Happiness by Gender

The results show the averages calculated for responses to the question “Do you feel happy?” for women and men, coded as 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no.” The averages are as follows:

- -

Women: 0.919118, or approximately 91.91%.

- -

Men: 0.917160, or approximately 91.72%.

These values suggest that, on average, around 91.91% of women and 91.72% of men in the study felt happy in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam.

The results of this analysis show that:

Both values are very close to 1, indicating that most people of both sexes feel happy. The values may reflect a generally positive perception among farmers.

The difference between women’s and men’s happiness averages is minimal (around 0.2%), suggesting no marked difference in this population’s self-reported happiness level between women and men. Both groups appear to be almost equally happy.

Although the women had a slightly higher average, this difference is probably insignificant without further statistical analysis. Therefore, a chi-square test was performed to determine whether the observed difference was statistically significant.

3.6.2. Chi-Square Test

The results of the chi-square test indicate the following:

Here is how the Chi-square test is interpreted:

High χ² statistic: The high value of the χ² statistic indicates a substantial discrepancy between observed and expected frequencies. The test suggests that the variables tested are probably not independent.

Extremely low p-value: The p-value is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.05, indicating that the differences observed in the data are statistically significant. With such a low p-value, you can reject the null hypothesis (which states no significant association between the variables tested) with high confidence.

Degrees of freedom (3): Degrees are based on the number of categories minus one in each variable. With 3 degrees of freedom, this corresponds to a 2x4 contingency table or similar, showing four categories compared between two groups.

Expected frequencies: Expected frequencies estimate what might be expected if the variables were independent. Differences between these expected and observed frequencies are the source of the high χ² statistic and the low p-value.

The chi-square test results, therefore, show a statistically significant association between the variables tested in the study. The results mean that the feeling of happiness is significantly associated with the city or gender of the participants. The exact nature of this association requires further analysis of observed versus expected frequencies to understand how specific categories contribute to this result.

3.7. Can Architectural Design and Urban Planning Improve Spatial Distribution? Spatial Analysis of Psychological Well-Being

3.7.1. Spatial Analysis

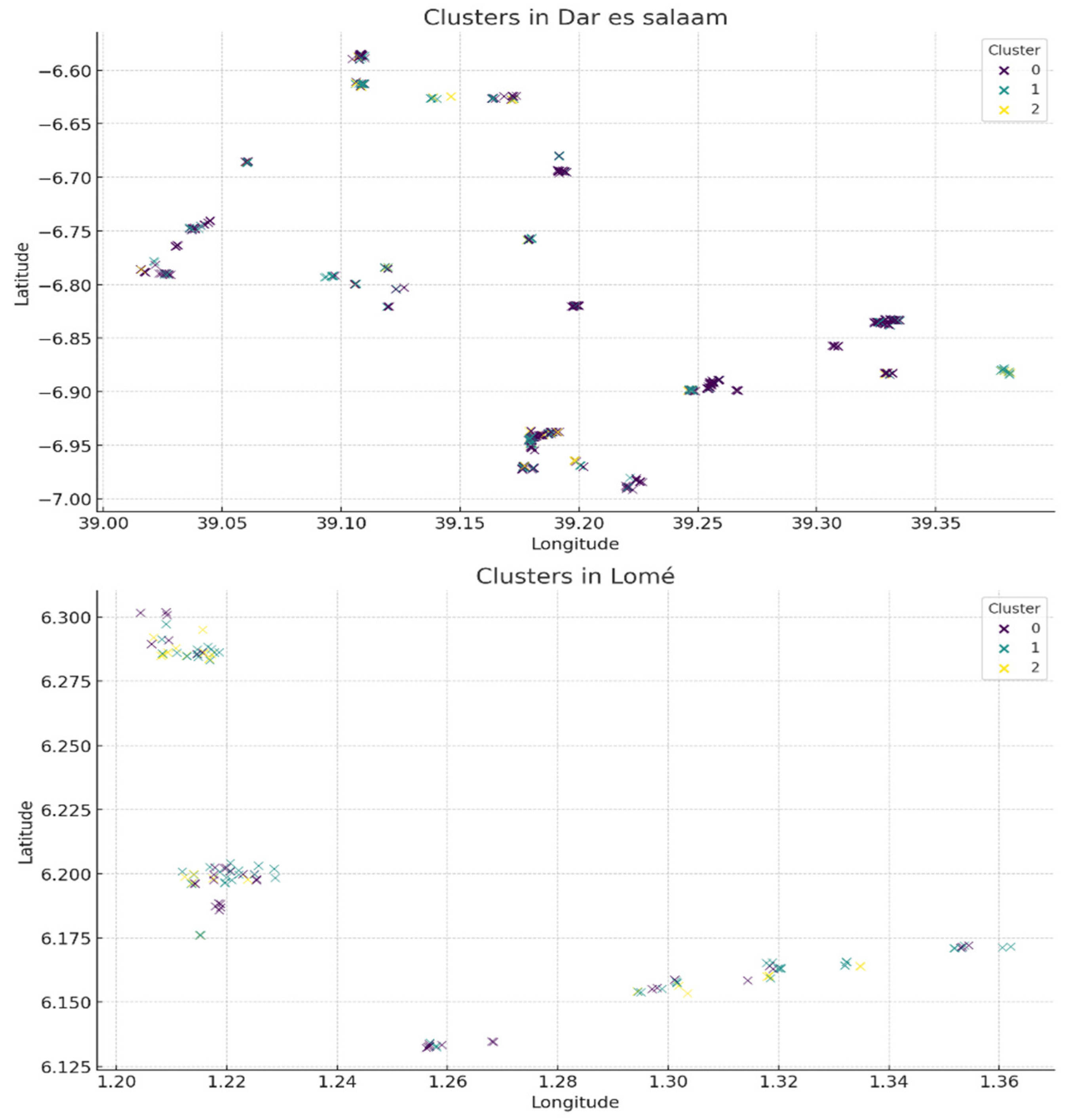

The K-Means algorithm was applied to both cities’ psychological well-being responses to identify clusters. An appropriate number of clusters was chosen based on the elbow method or similar criteria to ensure meaningful segmentation.

A map (Figure 5.15) was created with colored dots to visualize the spatial distribution of mental well-being by city.

Figure 5.

15. Spatial distribution of mental well-being by city.

Figure 5.

15. Spatial distribution of mental well-being by city.

Latitude and longitude were used to draw city maps with dots representing respondents, colored according to the cluster to which they belong.

Each point represents a respondent, colored according to the cluster to which it belongs. Three clusters were used to simplify the analysis, and the results show a spatial distribution of respondents according to their psychological well-being profile.

It is observed that :

- -

clusters are distributed across cities, suggesting variations in psychological well-being profiles within cities,

- -

some clusters seem to be more concentrated in certain areas of cities, which could indicate local environmental or social factors influencing psychological well-being.

3.7.2. QGIS Data Visualization of Clusters of the Cities of Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam

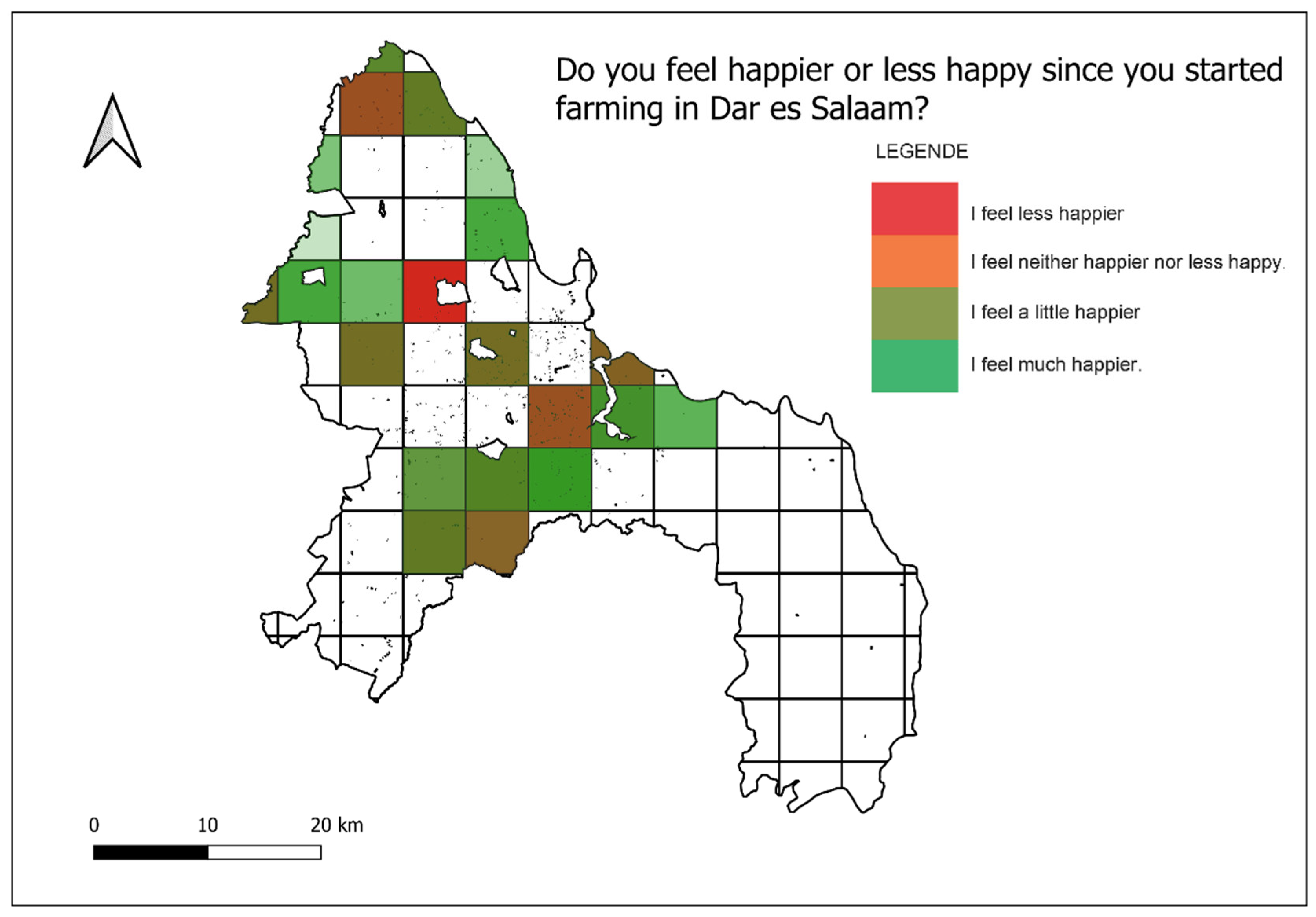

Analysis of the map of UA in Dar es Salaam (Figure 5.16) reveals some fascinating insights into urban farmers’ perceptions of this practice’s psychological benefits. Notably, those with little or no perception of the psychological benefits associated with UA are predominantly located in the central area of Dar es Salaam.

Figure 5.

16. ‘Do you feel happier or less happy since you starte farming in Dar es Salaam?’.

Figure 5.

16. ‘Do you feel happier or less happy since you starte farming in Dar es Salaam?’.

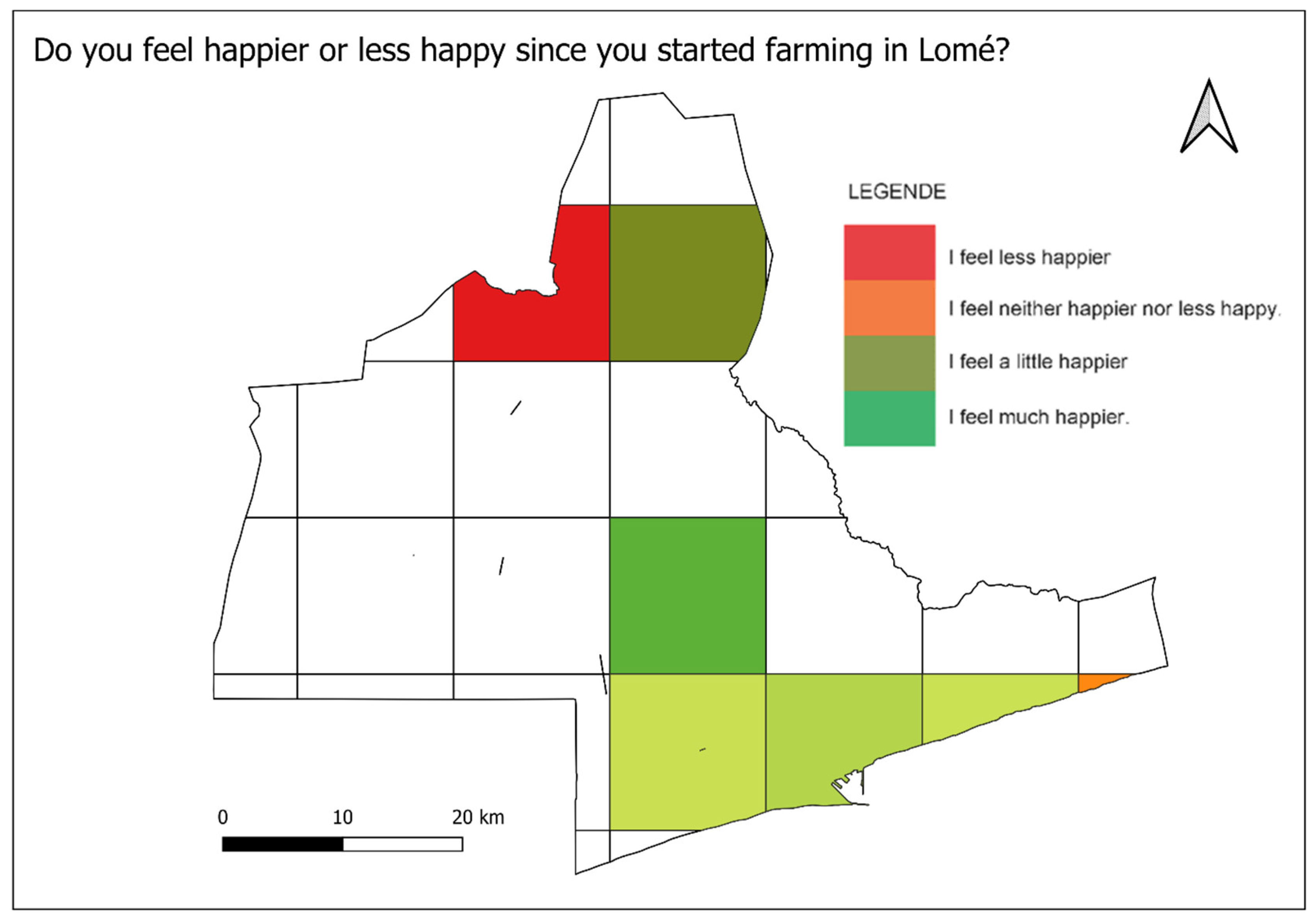

Examination of the map of Greater Lomé (Figure 5.17), focusing on UA and its benefits for psychological well-being, reveals a significant trend in the well-being of urban farmers. More specifically, farmers who express a feeling of ill-being or indifference towards the benefits of UA are mainly clustered in the northern peripheral areas of the city.

Figure 5.

17. “Do you feel happier or less happy since you starte farming in Greater Lomé?”.

Figure 5.

17. “Do you feel happier or less happy since you starte farming in Greater Lomé?”.

3.7.3. Comparison between Cities

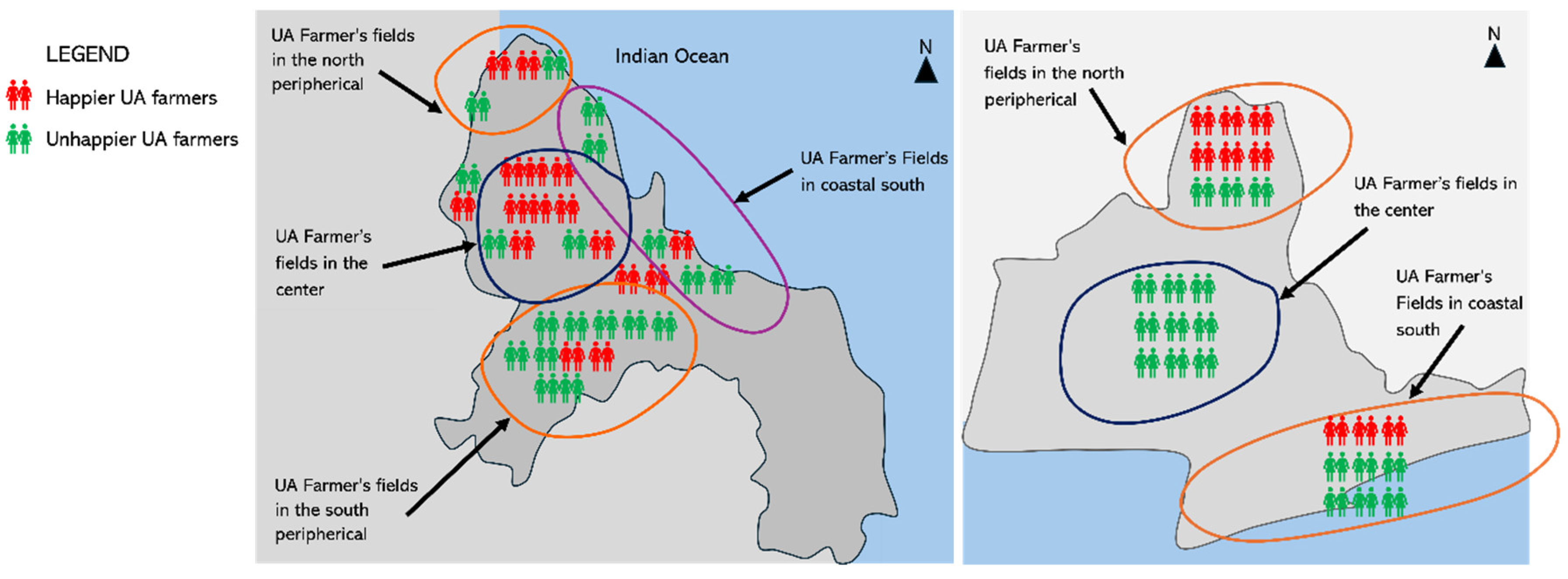

When the results of the two cities are compared (Figure 5.18), the clustering patterns are not uniform, indicating a diversity in psychological well-being that could reflect cultural, economic, or environmental differences.

Figure 5.

18. Comparison of Dar es Salaam and Greater Lomé spatial distribution of psychosocial Wellbeing.

Figure 5.

18. Comparison of Dar es Salaam and Greater Lomé spatial distribution of psychosocial Wellbeing.

4. Discussion

4.1. UA’s Contribution to Psychological Well-Being through Income

4.1.1. Overall Consideration of All Urban Farmers

The general question ‘Do you feel happy?’ measures farmers’ perceived well-being in a binary way. The large majority of over 90% of happy farmers could reflect a variety of positive factors influencing people’s well-being, such as personal satisfaction, a sense of community, economic security, or a favorable living environment [

67].

Regarding the question, “Do you feel happier or less happy since you started farming in the city?” the majority of positive results also suggest that UA is significantly associated with farmers’ emotional well-being. The figures for the 4% who felt less happy and the 8% who felt no difference since they started farming in the city indicate that, while UA may be a source of satisfaction for many [

68], it does not have the same effect on all farmers. The challenges associated with the practice, such as resource management, workload, or economic uncertainties, may affect urban farmers’ happiness differently.

Although these questions suggest a subjective measure of farmers’ well-being in Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam, the results are confirmed by the more detailed use of the standard Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) questionnaire.

As for the results of finer statistical calculations, a majority say they are happy, and the majority said they were happier than when they weren’t doing UA—there is no correlation with other variables.

Descriptive data analysis revealed a general trend toward positive perceptions of psychological well-being among participants. Most farmers reported feeling happy, interested in life, and satisfied, underlining a relatively high level of psychological well-being.

Inferential and predictive analyses between psychological well-being variables suggest that these aspects are often experienced jointly; for example, those who feel happy are also likely to feel satisfied and engaged in their community [

69]. The correlation between continental geographical factors between the two cities and some socio-economic indicators is weak, implying that psychological well-being may be more closely related to personal and behavioral factors than material or environmental conditions.

The results of the first scatter plot showing that the more households are composed of 5 people on average, the happier urban farmers report being could also be explained by the fact that if these households practice UA, it can offer an additional source of food and income, thus helping to improve the overall sense of well-being [

70].

As for the second scatter plot, those who attest to having started after 2000 seem to show higher happiness than others. This matter may reflect the technological improvements in access to information and support networks developed over the past two decades, making UA potentially more productive and less stressful [

71,

72]. It is also possible that recent initiatives to promote UA have created more favorable conditions for farmers, including better support policies, training programs, and more accessible markets to sell their crops, especially in Dar es Salaam [

73]. In addition, those who started more recently may have benefited from more sustainable and ecologically sensitive farming practices, contributing to a sense of positive contribution to the community and the environment, which can be linked to actual well-being [

74]. It could also be that those who have been practicing longer are the older ones and, therefore, those suffering from more UA-related health problems [

75].

4.1.2. Empowering Women through UA

General statistics regarding the link between gender and household leadership positions could indicate a cultural or societal trend in which men are more often recognized or self-appointed as the primary household leaders [

76]. This may have implications for decisions related to UA and access to resources [

77]. Secondary positions typically held by women could also reflect power and gender dynamics within households [

78].

The links between social status within the household and the emotional well-being derived from UA show that those who occupy the head of the household experience greater UA-related happiness [

77]. This matter could be attributed to the sense of autonomy and control involved in running a household and the responsibility of providing for the family, in which UA can play a substantial role. As primary heads of households, they may derive particular satisfaction from UA’s ability to improve their household’s well-being [

78].

Despite these data, further statistical calculations show that both sexes are equally affected. It is suggested that the practice of UA positively affects the psychological well-being of farmers of both sexes [

79]. However, in the samples, there were more women than men farmers in Dar es Salaam and fewer women than men in Greater Lomé. This means that, despite the disparities in status as head or second head of household, women feel empowered to a greater or lesser degree than men, thanks to UA. This means that, despite the disparities in status as head or second head of household, women feel empowered to a greater or lesser degree than men, thanks to UA, confer ‘The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index’ of Alkire et al. (2013).

UA significantly contributes to women’s empowerment [

81] by providing them with an income and improving their social status. The outcomes mark a step towards social equality in contexts where women’s rights are often limited.

In many households across the African continent, the mental burden borne by women is proving to be a considerable source of stress and, in some cases, can lead to mental disorders [

82,

83]. This reality is partly rooted in cultural norms that give women an inferior position both within the home and in society at large [

84,

85]. Indeed, in many African cultures, women are often denied the right to own land, a factor that not only limits their economic autonomy but also reinforces their dependence and vulnerability [

86].

Despite these obstacles, women’s contributions to the economy and development often exceed those of men through agriculture, trade, or other income-generating activities [

87,

88,

89]. However, their work and contributions remain largely undervalued and unrecognized, perpetuating a cycle of marginalization [

90,

91].

As a result, supporting and promoting income-generating activities for women in developing countries, specifically in Africa, is becoming a key strategy not only for combating poverty and fostering sustainable development but also for advancing gender equality and improving women’s mental and physical well-being [

92,

93].

As the study clearly illustrates, income-generating activities such as UA prove to be a promising avenue for women’s emancipation [

94]. UA offers women a source of income and a platform for strengthening their autonomy and position within society [

95]. By actively participating in UA, women can increase their food security, generate additional revenue for themselves and their families, and gain a sense of personal fulfillment and satisfaction [

96].

The study highlights how UA, as an income-generating activity, contributes significantly to the emancipation of women in African urban contexts [

13]. Through UA, women break down the cultural barriers that traditionally assign them an inferior role and demonstrate their ability to contribute significantly to the local economy and the well-being of their households and communities [

97,

98]. Involvement in UA enables women to take control of their lives, make important decisions about resource management, and assert their right to land ownership and urban space [

99,

100].

Within this framework, UA presents itself as an economic strategy and a holistic intervention supporting women’s emancipation on several economic, social, and psychological levels [

94]. By recognizing and supporting the role of women in UA, development policies and initiatives can, therefore, play a key role in promoting gender equality and improving the well-being of women in Africa [

101].

4.2. Urban Planning, Architectural Design, and Psychological Well-Being

4.2.1. Urban Farmers Are Slightly Happier in Dar es Salaam than in Greater Lomé

The analyses show differences in the spatial distribution of UA-related psychological well-being between Dar es Salaam and Greater Lomé. Dar es Salaam shows a more even distribution of well-being, thanks to better institutional integration of UA.

The data indicates that the income generated by UA is crucial in supporting farmers’ psychological well-being [

102]. This well-being is particularly evident in Dar es Salaam, where UA is institutionalized, provides a stable income, and contributes to a satisfactory standard of living. The fact suggests that people in Dar es Salaam have a more optimistic view of their society and fellow citizens than those in Greater Lomé.

The results could reflect cultural, economic, or social differences between the two cities that influence people’s perception of their well-being and societal role.

These differences could be due to various factors, including economic opportunities, social support, access to education and health services, or even climatic and environmental differences between the two cities [

103,

104,

105].

However, it is essential to note that although the averages are higher for Dar es Salaam in all categories, the presence of responses covering the whole scale (from 0 to 5) in both cities indicates a diversity of individual experiences and perceptions in each city. Standard deviations, which measure the dispersion of responses around the mean, also show considerable variability in farmers’ perceptions, suggesting that individual and contextual factors strongly influence emotional well-being and positive functioning.

In conclusion, this analysis suggests that while there are general differences in perceptions of emotional well-being and positive functioning between residents of Greater Lomé and Dar es Salaam, with an apparent advantage for Dar es Salaam, individual experiences vary widely. These differences call for a deeper understanding of the social, economic, and cultural contexts that contribute to personal well-being in these cities [

105].

4.2.2. Happiness IS located in Specific Spatial Zones in Each City

Spatial analysis through clusters shows that happiness is located in precise spatial zones in each city and is therefore linked to spatial location [

106,

107].

Spatial analysis revealed distinct clusters of psychological well-being within the cities studied. The maps generated illustrated significant spatial disparities, indicating that some urban areas could be islands of high or low well-being [

108]. The three main clusters identified by the K-Means analysis in each city showed that psychological well-being is heterogeneous, even within small geographical areas. The result may reflect differences in living conditions, economic opportunities, social networks, or available services and merits further investigation to understand the underlying causes of these patterns. The analysis, therefore, shows that psychological well-being varies within the populations studied, with distinct clusters reflecting different levels of well-being [

109]. These variations are present at individual, community, and city levels and not at a regional or continental level in this study.

The findings on the maps of the two cities underline the importance of a differentiated and targeted approach to UA support, considering the specificities and needs of farmers according to their geographical location [

110]. There are several reasons for this situation in the northern outskirts of Greater Lomé and the center of Dar es Salaam. Firstly, these regions may be characterized by more limited access to essential resources for agriculture, such as water, quality agricultural inputs, or markets to sell produce in Greater Lomé. In the case of Dar es Salaam, this could be linked to high urban density, land pressure and competition for space, pollution, and noise, limited access to resources, isolation, restrictive urban regulation, or the stress of high food requirements in the city center [

111]. These logistical and economic constraints can increase farmers’ stress and workload, reducing their overall satisfaction and well-being.

It is essential to develop tailored strategies to improve access to resources to improve the well-being of farmers in the northern outlying areas of Greater Lomé, strengthen support networks, and mitigate the environmental challenges specific to these regions [

112,

113,

114]. Such an approach could help transform the UA experience for these farmers from indifference or discomfort to a more positive appreciation of their activity and its association with their quality of life.

Further studies are recommended to identify the specific factors influencing psychological well-being in these clusters [

115]. Targeted interventions could be developed to support groups with lower psychological well-being, considering each community’s cultural and social specificities.

4.3. Recommendations

Here are some recommendations for Action for urban planners, architects, and planners of UA in African cities as part of considering the benefits of UA practice on the well-being of city dwellers.

4.3.1. Integrating UA Into Urban Planning, but also Spatial and Architectural Designs that Promote Psychological Well-Being

Urban planners and architects need to consider the integration of UA into urban development plans. The integration includes spatial data analysis [

116], the designation of well-located, spatially, and socio-economically heterogeneous greenable spaces suitable for UA in new development projects [

117], the programming and design of accompanying infrastructure for UA [

118], and the revision of existing plans to incorporate urban agricultural zones [

119].

It would also be beneficial to design urban spaces that encourage social interaction and the creation of support networks among urban farmers [

120,

121,

122,

123]. Green spaces for UA should be accessible, safe, and aesthetically pleasing to promote participation and support the psychological well-being of communities [

124,

125,

126].

4.3.2. In-Depth Studies and Research and Institutional Capacity-Building

Studies and research should be encouraged to understand better the factors that influence psychological well-being in the context of UA [

127,

128,

129]. The results should guide the development of policies and programs to maximize UA’s benefits on city dwellers’ well-being [

130].

Local authorities and development organizations could also build institutional capacity to support UA through training urban farmers, supporting the marketing of agricultural products, and developing UA-friendly policies [

131,

132,

133].

4.3.3. Supporting Women’s Empowerment through UA

The research recommends promoting UA as a means of economic and social empowerment for women [

134]. The results can be achieved by facilitating women’s access to land, financing, information, training, and adapted agricultural technologies [

135]. Initiatives should also eliminate legal and cultural barriers limiting women’s participation in UA [

136].

4.4. Limitations

When examining the results of the UA study and its association with psychological well-being, it is necessary to recognize a few limitations that could influence the interpretation of the data and the generalization of the results.

4.4.1. Other Factors Influencing Well-Being

A multitude of factors beyond UA practice alone can influence psychological well-being. These factors include but are not limited to, socio-economic conditions, access to mental health services, social support networks, and stress levels in other areas of life [

137,

138]. Therefore, although this study seeks to assess the association between UA and well-being, the differences observed between the two cities could also be attributable to these other uncontrolled variables.

4.4.2. Clustering of Farmers Surveyed

The method of selecting participants for the survey, mainly if the farmers surveyed were grouped in some regions of the towns, may introduce a clustering bias. The clustering means that the results may not fully represent the general UA population in each city. Farmers within the same cluster may share similar characteristics or be subject to particular environmental conditions that are not necessarily generalizable to the entire urban population practicing UA.

4.4.3. Psychological Well-Being Linked to Contact with Greenery

Another aspect of the association between UA and health, often put forward, is the psychological well-being linked to contact with plants and the color green, to the satisfaction of planting and seeing crops grow, but also to molecules such as endorphin secreted in the body after practicing UA as physical exercise [

139,

140,

141]. This dimension of well-being is particularly emphasized in Western contexts, where interaction with nature may be less frequent in everyday urban life. However, it is essential to recognize that the intensity of these effects can vary considerably from person to person and that the role of exercise itself could be a confounding factor in the association between UA and psychological well-being.

5. Conclusion

The findings of this study underline the importance of considering the psychological and social dimensions of well-being in urban and development policies. Local authorities could use this information to target interventions to improve well-being in areas with lower happiness levels. Further research is advocated to examine the specific factors contributing to psychological well-being in the clusters identified, including qualitative studies that could provide insight into residents’ lived experiences. Finally, the methodological approach adopted, combining statistical and spatial analyses, could be applied to other urban contexts to assess well-being and inform policy more granularly.

UA is emerging as a crucial vector for food security and economic strengthening in African cities and as a significant means of improving psychological well-being. The study highlights the importance of UA in promoting happiness, satisfaction, and community involvement among urban farmers, revealing its potential as a tool for empowerment, particularly for women.

There is a need to promote UA and do more because it enables women to become emancipated and achieve the same happiness as men. Which, culturally, is not the case. It seems that this conclusion underlines the importance of promoting initiatives that enable women to reach a level of happiness and empowerment equivalent to that of men, which, according to the text, is not yet a cultural norm.

The proposed recommendations, therefore, aim to encourage spatial analysis of the association between UA and the well-being of city dwellers, especially farmers, and the strategic integration of UA into urban planning and policy development, with particular emphasis on women’s empowerment and psychological well-being. Urban planners, architects, and policymakers must recognize UA as an economic necessity and an opportunity to strengthen the social fabric and improve the quality of life in African urban environments.

Finally, the edges of the study highlight the need for further, regular research to isolate the effect of UA on psychological well-being from the influences of other potential variables. Future studies could benefit from a methodological design that controls these confounding factors and provides a more detailed analysis of the mechanisms by which UA contributes to psychological well-being. By adopting a holistic and inclusive approach, UA can become a central pillar of sustainable urban planning, creating resilient, equitable, and thriving African cities where the well-being of all citizens is a priority.

Funding

This research was supported by an SNSF grant source of funding: This work was fully supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF#183577) Sinergia project - African contribution to global health: Circulation of knowledge and innovations.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the farmers of Dar es Salaam, the staff of the municipal offices, and all the students and staff of ARDHI University, in particular the School of Spatial Planning and Social Sciences (SSPSS) and the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, CERViDA DOUNEDON and the University of Lomé. We would also like to thank Vitor Pessoa Colombo, Marti Bosch, Pablo Txomin Harpo de Roulet from our CEAT laboratory at EPFL, Anne-Marlène Rüeder, M. Kodjo Mawuena Tchini for their support during our research.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Tallaki, K. Pest Control System in the Market Gardens of Lome, Togo, 2006.

- Konou, A.A.; Kemajou Mbianda, A.F.; Munyaka, B.J.-C.; Chenal, J. Two Decades of Architects’ and Urban Planners’ Contribution to Urban Agriculture and Health Research in Africa. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, K.; Conard, M.; Culligan, P.; Plunz, R.; Sutto, M.-P.; Whittinghill, L. Sustainable Food Systems for Future Cities: The Potential of Urban Agriculture. Econ. Soc. Rev. 2014, 45, 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Konou, A.A.; Kemajou Mbianda, A.F.; Munyaka, B.J.-C.; Chenal, J. Two Decades of Architects’ and Urban Planners’ Contribution to Urban Agriculture and Health Research in Africa. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, V.; Kouamé, C.; Pasquini, M.W.; Temple, L. A Review of Urban and Peri-Urban Vegetable Production in West Africa. Acta Hortic. 2007, 762, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S. Planning for Equitable Urban Agriculture: Opportunities and Quandaries. In Planning for Equitable Urban Agriculture in the United States: Future Directions for a New Ethic in City Building; Raja, S., Caton Campbell, M., Judelsohn, A., Born, B., Morales, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-3-031-32076-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, A.; Cantoreggi, N.; Simos, J.; Duchemin, É. Impacts Sur La Santé Des Pratiques Des Agriculteurs Urbains à Dakar (Sénégal). VertigO Rev. Électronique En Sci. L’environnement 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumat, C.; Xiong, T.; Shahid, M. Agriculture urbaine durable : opportunité pour la transition écologique; Presses Universitaires Européennes: Saarbrücken, DE, 2016; ISBN 978-3-639-69662-2. [Google Scholar]

- Nabulo, G.; Young, S.D.; Black, C.R. Assessing Risk to Human Health from Tropical Leafy Vegetables Grown on Contaminated Urban Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 5338–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, T.; Alfredo, K.; Fisher, J. Sustainable Water Management in Urban, Agricultural, and Natural Systems. Water 2014, 6, 3934–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkenberg, E.; McCall, P.; Wilson, M.D.; Amerasinghe, F.P.; Donnelly, M.J. Impact of Urban Agriculture on Malaria Vectors in Accra, Ghana. Malar. J. 2008, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulsen, M.N.; McNab, P.R.; Clayton, M.L.; Neff, R.A. A Systematic Review of Urban Agriculture and Food Security Impacts in Low-Income Countries. Food Policy 2015, 55, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, R.J. Urban Agriculture, Gender and Empowerment: An Alternative View. Dev. South. Afr. 2001, 18, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clucas, B.; Parker, I.D.; Feldpausch-Parker, A.M. A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Urban Agriculture and Biodiversity. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, R. Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture Sourcebook: From Production to Food Systems; FAO, Rikolto International s.o.n., RUAF Global Partnership on Sustainable Urban Agriculture and Food Systems: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-92-5-136111-5. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, M.N.; McNab, P.R.; Clayton, M.L.; Neff, R.A. A Systematic Review of Urban Agriculture and Food Security Impacts in Low-Income Countries. Food Policy 2015, 55, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsel, P.; Kunze, D. Waste Composting for Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture: Closing the Rural-Urban Nutrient Cycle in Sub-Saharan Africa; CABI, 2001; ISBN 978-0-85199-889-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mlozi, M.R.S. Impacts of Urban Agriculture in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Environmentalist 1997, 17, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, L.J.A. Agropolis: The Social, Political and Environmental Dimensions of Urban Agriculture; Routledge, 2010; ISBN 978-1-136-53592-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ahoudi, H.; Gnandi, K.; Tanouayi, G.; Ouro-Sama, K.; Yorke, J.-C.; Creppy, E.E.; Moesch, C. Assessment of Pesticides Residues Contents in the Vegetables Cultivated in Urban Area of Lome (Southern Togo) and Their Risks on Public Health and the Environment, Togo. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2018, 12, 2172–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakuru, M. Urbanization and Its Impacts to Food Systems and Environmental Sustainability in Urban Space: Evidence from Urban Agriculture Livelihoods in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. J. Environ. Prot. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, A. Designing Urban Agriculture: A Complete Guide to the Planning, Design, Construction, Maintenance and Management of Edible Landscapes; John Wiley & Sons, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-07383-4. [Google Scholar]

- Deksissa, T.; Trobman, H.; Zendehdel, K.; Azam, H. Integrating Urban Agriculture and Stormwater Management in a Circular Economy to Enhance Ecosystem Services: Connecting the Dots. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, L.J.A.; Centre (Canada), I.D.R. Growing Better Cities: Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Development; IDRC, 2006; ISBN 978-1-55250-226-6. [Google Scholar]

- Januszkiewicz, K.; Jarmusz, M. Envisioning Urban Farming for Food Security during the Climate Change Era. Vertical Farm within Highly Urbanized Areas. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 052094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, R. The Impact of Urban Agriculture on the Household and Local Economies. Grow. Cities Grow. Food Urban Agric. Policy Agenda 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mkwambisi, D.D.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J. Urban Agriculture and Poverty Reduction: Evaluating How Food Production in Cities Contributes to Food Security, Employment and Income in Malawi. J. Int. Dev. 2011, 23, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giradet, H. Urban Agriculture and Sustainable Urban Development. In Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes; Routledge, 2005; ISBN 978-0-08-045452-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tripon, M.; Boccanfuso, D. AGRICULTURE URBAINE, PRATIQUES AGRICOLES ET IMPACTS ENVIRONNEMENTAUX ET DE SANTE PUBLIQUE. 2020.

- Lawniczak, A.E.; Zbierska, J.; Nowak, B.; Achtenberg, K.; Grześkowiak, A.; Kanas, K. Impact of Agriculture and Land Use on Nitrate Contamination in Groundwater and Running Waters in Central-West Poland. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, I.; Otero, N.; Soler, A.; Green, A.J.; Soto, D.X. Agricultural and Urban Delivered Nitrate Pollution Input to Mediterranean Temporary Freshwaters - ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016788092030044X (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Maćkiewicz, B.; Asuero, R.P.; Almonacid, A.G. Urban Agriculture as the Path to Sustainable City Development. Insights into Allotment Gardens in Andalusia. Quaest. Geogr. 2019, 38, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit-Boix, A.; Apul, D. From Cascade to Bottom-Up Ecosystem Services Model: How Does Social Cohesion Emerge from Urban Agriculture? Sustainability 2018, 10, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalloh, A. Measuring Happiness: Examining Definitions and Instruments. Illuminare 2014, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S.; Graham, J.; Kesebir, S.; Galinha, I.C. Concepts of Happiness Across Time and Cultures. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norrish, J.M.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Is the Study of Happiness a Worthy Scientific Pursuit? Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 87, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravlev, A.L.; Yurevich, A.V. Happiness as a Scientific Category. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2014, 84, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourner, T.; Rospigliosi, A. The Importance of Scientific Research on Happiness and Its Relevance to Higher Education. High. Educ. Rev. 2014, 35–55. [Google Scholar]