Submitted:

07 May 2024

Posted:

08 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

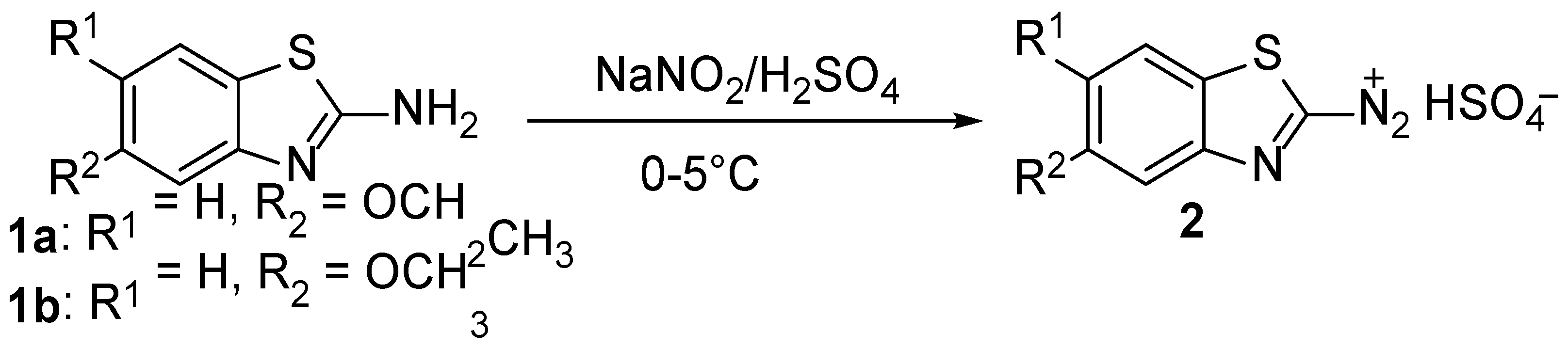

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. General Information

2.1.2. Preparation of the Reagents and Starting Materials

2.2. Biological Activity

2.2.1. Reference Compounds and Bacterial Strains

2.2.2. Determination of the Anti-Shigella Activity of Compounds and Antibiotics

2.2.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.2.4. Potential Mechanism of Antibacterial Action and Combination Studies

2.2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

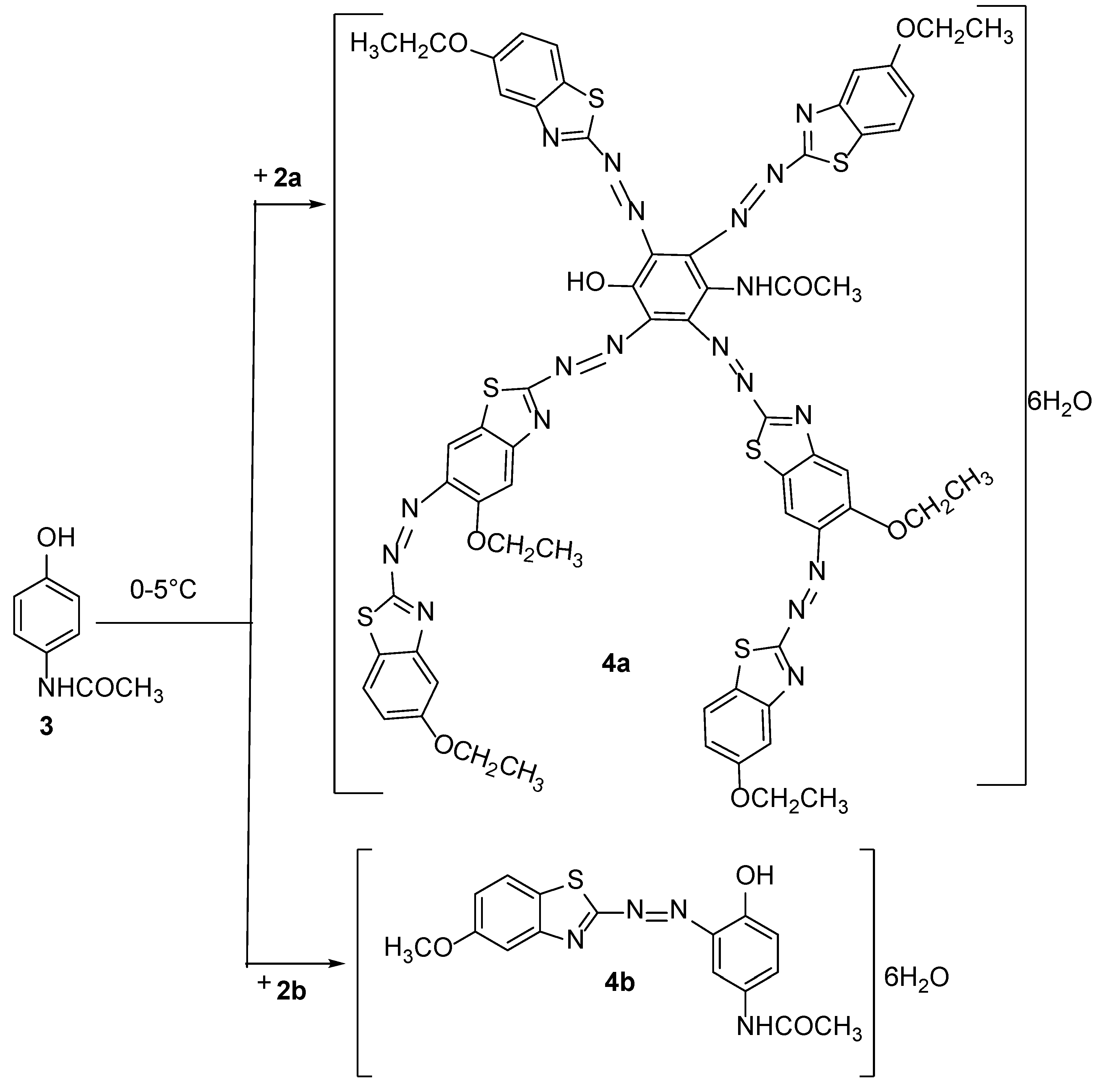

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Assays

3.3. Bacterial Growth Kinetics and Combination Studies

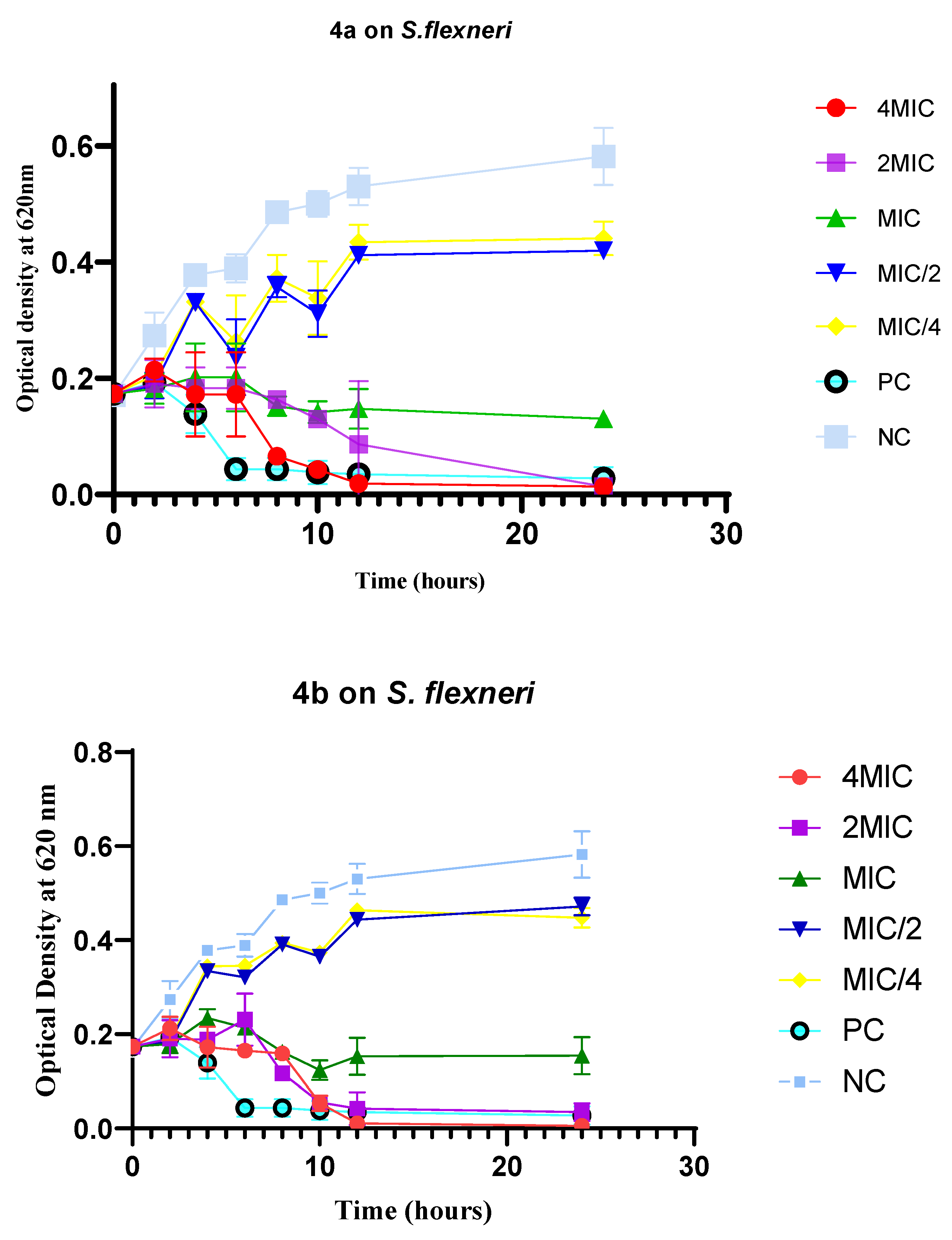

3.3.1. Shigella Growth Kinetics

3.3.2. Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activities of the Combination of Active Compounds with Selected Antibiotics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tarr, P.I.; Bass, D.M.; Hecht, G.A. Bacterial, viral, and toxic causes of diarrhea, gastroenteritis, and anorectal infections In: Yamada T, ed. Textbook of Gastroenterology. fifth ed. Blackwell; 2009, 1157-1224.

- The World Health Organization (WHO), 2023. Diarrheal disease. The Fact Sheets. https://www.who.int/health-topics/diarrhoea#tab=tab_3, Accessed on 30th August 2023.

- Ammoury, R.F.; Ghishan, F.K. Pathophysiology of diarrhea and its clinical implications, In J. D. W, Johnson Leonard R., Ghishan Fayez K., Kaunitz Jonathan D., Merchant Juanita L., Said Hamid M. (Ed.), Physiology of the Gastronintestinal Tract, Fifth Edit, Elsevier Inc, 2012, pp. 2183–2198.

- Ezekwesili, C.N.; Obiora, K.A.; Ugwu, O.P. Evaluation of anti-diarrhoeal property of crude aqueous extract of Ocimum gratissimum L. (Labiatae) in rats. Biokemistri. 2004, 16, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K.L.; Riddle, M.S.; Platts-Mills, J.A.; Pavlinac, P.; Zaidi, A.K.M. Shigellosis. Lancet (London, England) 2018, 391, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndze, V.N.; Akum, A.E.; Kamga, G.H.; Enjema, L.E.; Esona, M.D.; Banyai, K.; Therese, O.A. Epidemiology of rotavirus diarrhea in children under 5 years in Northern Cameroon. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2012, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taneja, N.; Mewara, A. Shigellosis: epidemiology in India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2016, 143, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, I.A.; Troeger, C.; Blacker, B.F.; Rao, P.C.; Brown, A.; Atherly, D.E.; Brewer, T.G.; Engmann, C.M.; Houpt, E.R.; Kang, G.; Kotloff, K.L.; Levine, M.M.; Luby, S.P.; MacLennan, C.A.; Pan, W.K.; Pavlinac, P.B.; Platts-Mills, J.A.; Qadri, F.; Riddle, M.S.; Ryan, E.T.; Shoultz, D.A.; Steele, A.D.; Walson, J.L; Sanders, JW.; Mokdad, A.H.; Murray, C.J.L.; Hay, S.I.; Reiner, R.C.Jr. Morbidity and mortality due to shigella and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli diarrhoea: the global burden of disease study 1990-2016. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahsay, A.G.; Muthupandian, S. A review on sero diversity and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Shigella species in Africa, Asia and South America, 2001–2014. BMC Res. Notes. 2016, 9, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Raval, I.H. Chapter 32 - Pathogenic Microbial Genetic Diversity with Reference to Health in Microbial Diversity in the Genomic Era, 2019, Pages 559-577.

- Stażyk, K.; Krycińska, R.; Jacek, C.; Garlicki, A.; Biesiada, G. Diarrhea caused by Shigella flexneri in patients with primary HIV infection. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2019, 30, 814–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, I.; Qasim, M.; Driessen, A.; Nijland, J.; Bari, F.; Haroon, M.; Rahman, H.; Yasin, N.; Khan, T.A.; Hussain, M.; Ullah, W. Molecular epidemiology of Shigella flexneri isolated from pediatrics in a diarrhea-endemic area of Khyber. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzari, M.; Sharma, M.; Chetia, P. Emergence of antibiotic resistant Shigella species: A matter of concern. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, D.; Ramamurthy, T.; Deen, J.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Shigellosis: challenges & management issues. Indian J. Med. Res. 2004, 120, 454–462. [Google Scholar]

- Thorley, K.; Charles, H.; Greig, D.R.; Prochazka, M.; Mason, L.C.E.; Baker, K.S.; Godbole, G.; Sinka, K.; Jenkins, C. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant Shigella flexneri serotype 2a associated with sexual transmission among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, in England: a descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faure, C. Role of antidiarrhoeal drugs as adjunctive therapies for acute diarrhoea in children. Int. J. Pediatrics 2013, 2013, 612403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broder, M.S.; Chang, E.; Romanus, D.; Cherepanov, D.; Neary, M.P. Healthcare and economic impact of diarrhea in patients with carcinoid syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 2118–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, E.; Abtahi, H.; van Belkum, A.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E. Multidrug-resistant Shigella infection in pediatric patients with diarrhea from central Iran. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaghani, S.; Shamsizadeh, A.; Nikfar, R.; Hesami, A. Shigella flexneri: a three-year antimicrobial resistance monitoring of isolates in a Children Hospital, Ahvaz, Iran. Iran J. Microbiol. 2014, 6, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.C.M.; Berkley, J.A. Guidelines for the treatment of dysentery (shigellosis): a systematic review of the evidence. Paediatrics and International Child Health 2018, 38, S50–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, R.; Farahani, A. Shigella: Antibiotic-resistance mechanisms and new horizons for treatment. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3137–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunchorntavakul, C.; Reddy, K.R. Acetaminophen-related hepatotoxicity. Clin. Liver Dis. 2013, 17, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Janabi, A.A. In vitro antibacterial activity of Ibuprofen and acetaminophen. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2010, 2, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, M.R.; Jaeschke, H. Metabolism and disposition of acetaminophen: recent advances in relation to hepatotoxicity and diagnosis. Pharm. Res. 2013, 30, 2174–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, A.L.; Buckley, N.A. Acetaminophen poisoning. Crit. Care Clin. 2021, 37, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, K.W.; Park, M.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, T.W.; Kim, H.J. Effects of benzothiazole on the xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes and metabolism of acetaminophen. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2000, 20, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Pérez, L.C.; Padilla-Martínez, I.I.; Cruz, A.; Mendieta-Wejebe, J.E.; Tamay-Cach, F.; Rosales-Hernández, M.C. Evaluation of a new benzothiazole derivative with antioxidant activity in the initial phase of acetaminophen toxicity. Arab. J. Chem 2019, 12, 3871–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsemeugne, J.; Nangmo, P.K.; Mkounga, P.; Tamokou, J.D.D.; Kengne, I.C.; Edwards, G.; Sopbué, E.F.; Nkengfack, A.E. Synthesis, characteristic fragmentation patterns, and antibacterial activity of new azo compounds from the coupling reaction of diazobenzothiazole ions and acetaminophen. Heterocycl. Commun. 2021, 27, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.C.; Kumar, R.; Chaudhary, M.; Sharma, A.; Rajak, H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel benzothiazole clubbed fluoroquinolone derivatives. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffer, H.E.; Fouda, M.M.G.; Khalifa, M.E. Synthesis of some novel 2-amino-5-arylazothiazole disperse dyes for dyeing polyester fabrics and their antimicrobial activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjorgjieva, M.; Tomašič, T.; Kikelj, D.; Mašič, L.P. Benzothiazole-based compounds in antibacterial drug discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 5218–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroun, M. Review on the developments of benzothiazole-containing antimicrobial agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 2630–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Luo, J.; Deng, F.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H. Antibiotic combination therapy: A strategy to overcome bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, S.H.; Ahmed, K.; Kazmi, S.U. The antibiofilm activity of acetylsalicylic acid, mefenamic acid, acetaminophen against biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa and S. epidermidis. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2019, 69, 1493–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Paes Leme, R.C.; da Silva, R.B. Antimicrobial activity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on biofilm: Current evidence and potential for drug repurposing. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 707629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI, 2012. CLSI Publishes 2012 Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Standards—Medical Design and Outsourcing. https://www.medicaldesignandoutsourcing.com/clsi-publishes-2012-antimicrobial-susceptibility-testing-standards/ (accessed 6.7.23).

- Sinha, S.; Batovska, D.I.; Medhi, B.; Radotra, B.D.; Bhalla, A.; Markova, N.; Sehgal, R. In vitro anti-malarial efficacy of chalcones: cytotoxicity profile, mechanism of action and their effect on erythrocytes. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidock, D.A.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Croft, S.L.; Brun, R.; Nwaka, S. Antimalarial drug discovery: efficacy models for compound screening. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melogmo Dongmo, Y.K.; Tchatat Tali, M.B.; Dize, D.; Jiatsa Mbouna, C.D.; Kache Fotsing, S.; Ngouana, V.; Pinlap, B.R.; Zeuko’o Menkem, E.; Yamthe Tchokouaha, L.R.; Fotso Wabo, G.; Lenta Ndjakou, B.; Lunga, P.K.; Fekam Boyom, F. Anti-Shigella and antioxidant-based screening of some Cameroonian medicinal plants, UHPLC-LIT-MS/MS fingerprints, and prediction of pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties of identified chemicals. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 324, 117788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepser, M.E.; Ernst, E.J.; Lewis, R.E.; Ernst, M.E.; Pfaller, M.A. Influence of test conditions on antifungal time-kill curve results: proposal for standardized methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellio, P.; Fagnani, L.; Nazzicone, L.; Celenza, G. New and simplified method for drug combination studies by checkerboard assay. Methods X, 2021, 8, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagadinou, M.; Onisor, M.O.; Rigas, A.; Musetescu, D.-V.; Gkentzi, D.; Assimakopoulos, S.F.; Panos, G.; Marangos, M. Antimicrobial properties on non-antibiotic drugs in the Era of increased bacterial resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A. Anti-inflammatory agents: Present and future. Cell 2010, 140, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliyappa, M.R.; Keshavayya, J.; Nazrulla, M.A.; Sudhanva, M.S.; Rangappa, S. Six-substituted benzothiazole based dispersed azo dyes having antipyrine moiety: synthesis, characterization, DFT, antimicrobial, anticancer and molecular docking studies. J. Iran Chem. Soc. 2022, 19, 3815–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, N.; Tittal, R.K.; Ghule, V.D. 1,2,3-Triazoles of 8-Hydroxyquinoline and HBT: synthesis and studies (DNA binding, antimicrobial, molecular docking, ADME, and DFT. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 27089–27100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skok, Z.; Barančoková, M.; Benek, O.; Cruz, C.D.; Tammela, P.; Tomašič, T.; Zidar, N.; Mašič, L.P.; Zega, A.; Stevenson, C.E.M.; Mundy, J.E.A.; Lawson, D.M.; Maxwell, A.; Kikelj, D.; Ilaš, J. Exploring the chemical space of benzothiazole based DNA Gyrase B inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2433–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.R.; Ghanavatkar, C.W.; Mali, S.N.; Chaudhari, H.K.; Sekar, N. Schiff base clubbed benzothiazole: synthesis, potent antimicrobial and MCF-7 anticancer activity, DNA cleavage and computational study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 38, 1772–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousaxidis, A.; Kovacikova, L.; Nicolaou, I.; Stefek, M.; Geronikaki, A. Non-acidic bifunctional benzothiazole-based thiazolidinones with antimicrobial and aldose reductase inhibitory activity as a promising therapeutic strategy for sepsis. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 1837–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsy, M.A.; Ali, E.M.; Kandeel, M.; Venugopala, K.N.; Nair, A.B.; Greish, K.; El-Daly, M. Screening and molecular docking of novel benzothiazole derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyambulingam, J.K.; Karvembu, R.; Bhuvanesh, N.S.P.; Enoch, I.V.M.V.; Selvakumar, P.M.; Premnath, D.; Subramanian, C.; Mayakrishnan, P.; Kim, S.-H.; Chung, I.-M. Synthesis, structure, biological/chemosensor evaluation and molecular docking studies of aminobenzothiazole Schiff bases. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2020, 34, 2590–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoi, M.N.; Borad, M.A.; Jethava, D.J.; Acharya, P.T.; Pithawala, E.A.; Patel, C.N.; Pandya, H.A.; Patel, H.D. Synthesis, biological evaluation and computational study of novel isoniazid containing 4H-Pyrimido [2,1-b] benzothiazoles derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 177, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.R.; Ghanavatkar, C.W.; Mali, S.N.; Qureshi, S.I.; Chaudhari, H.K.; Sekar, N. Design, synthesis, antimicrobial activity and computational studies of novel azo linked substituted benzimidazole, benzoxazole and benzothiazole derivatives. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 78, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondru, R.; Sirisha, K.; Raj, S.; Gunda, S.K.; Kumar, C.G.; Pasupuleti, M.; Bavantula, R. Design, synthesis, in vitro evaluation and docking studies of pyrazole-thiazole hybrids as antimicrobial and antibiofilm agents. Chem. Sel. 2018, 3, 8270–8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, B.; Chauhan, K.; Trivedi, J.; Jaiswal, V.; Kanwar, S.S.; Pokharel, Y.R. Benzothiazole-based-bioconjugates with improved antimicrobial, anticancer and antioxidant potential. Chem. Sel. 2018, 3, 11326–11332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaz, F.; Srivastava, R.; Singh, A.; Singh, N.; Verma, R.; Singh, V.K.; Singh, RK. Molecular modeling, synthesis, antibacterial and cytotoxicity evaluation of sulfonamide derivatives of benzimidazole, indazole, benzothiazole and thiazole. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 3414–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, P.; Verma, S.; Gupta, P.; Narang, R.; Lal, S.; Devgun, M. Recent insights into antibacterial potential of benzothiazole derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2023, 32, 1543–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniface, P.K.; Ferreira, E.I. Flavonoids as efficient scaffolds: Recent trends for malaria, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, and dengue. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2473–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, A.; Kwiatkowska, A.; Potocki, L. Antibiotics and bacterial resistance-A short story of an endless arms race. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusei, E.B.A.; Adosraku, R.K.; Oppong-Kyekyeku, J.; Amengor, C.D.K.; Jibira, Y. Resistance modulation action, time-kill kinetics assay, and inhibition of biofilm formation effects of plumbagin from Plumbago zeylanica Linn. J. Trop. Med. 2019, 2019, 1250645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougnon, V.; Hounsa, E.; Agbodjento, E.; Keilah, L.P.; Legba, B.B.; Sintondji, K.; Afaton, A.; Klotoe, J.R.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Bankole, H. Percentage destabilization effect of some West African medicinal plants on the outer membrane of various bacteria involved in infectious diarrhea. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohanski, M.A.; Dwyer, D.J.; Hayete, B.; Lawrence, C.A.; Collins, J.J. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 2007, 130, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, A.R.M.; Hu, Y.; Holt, J.; Yeh, P. Antibiotic combination therapy against resistant bacterial infections: synergy, rejuvenation and resistance reduction. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugaiyan, J.; Kumar, P.A.; Rao, G.S.; Iskandar, K.; Hawser, S.; Hays, J.P.; Mohsen, Y.; Adukkadukkam, S.; Awuah, W.A.; Jose, R.A.M.; Sylvia, N.; Nansubuga, E.P.; Tilocca, B..; Roncada, P.; Roson-Calero, N.; Moreno-Morales, J.; Amin, R.; Kumar, B.K.; Kumar, A.; Toufik, A.R.; Zaw, T.N.; Akinwotu, O.O.; Satyaseela, M.P.; van Dongen, M.B.M. Progress in alternative strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance: Focus on antibiotics. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 1, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguena-Dongue, B.N.; Tchamgoue, J.; Ngandjui Tchangoue, Y.A.; Lunga, P.K.; Toghueo, K.R.M.; Zeuko, O.M.E.; Melogmo, Y.K.D.; Tchouankeu, J.C.; Kouam, S.F.; Fekam, B.F. Potentiation effect of mallotojaponin B on chloramphenicol and mode of action of combinations against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0282008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibezim, A.; Onuku, R.S.; Ibezim, A.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Nwodo, N.J.; Adikwu, M.U. Structure-based virtual screening and molecular dynamics simulation studies to discover new SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Sci. Afr. 2021, 14, e00970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Hidalgo, L.; de Alarcón, A.; López-Cortes, L.E.; Luque-Márquez, R.; López-Cortes, L.F.; Gutiérrez-Valencia, A.; Gil-Navarro, M.V. Is once-daily high-dose ceftriaxone plus ampicillin an alternative for Enterococcus faecalis infective Endocarditis in outpatient parenteral antibiotic Therapy programs? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 65, e02099-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Minimum inhibitory concentrations(µg/mL) | HC50 | SI (HC50/MIC50) | ||||

| SF NR 518 | SO NR 519 | SB NR 521 | SDcpc | ||||

| Compounds | 1a | 100 | - | - | - | ˃200 | ˃4 |

| 1b | 100 | - | - | - | ˃200 | ˃4 | |

| 3 | - | - | - | - | ˃200 | / | |

| 4a | 12.5 | 50 | - | - | 148.85±2.95 | 23.68 | |

| 4b | 12.5 | 50 | - | - | 87.52±0.7 | 13.92 | |

| Antibiotics | Amp | ˂0.062 | / | / | / | / | / |

| Cef | 12.5 | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Tet | ˂0.062 | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Cot | 12.5 | / | / | / | / | / | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.062 | 0.015 | 0.062 | 0.015 | / | / | |

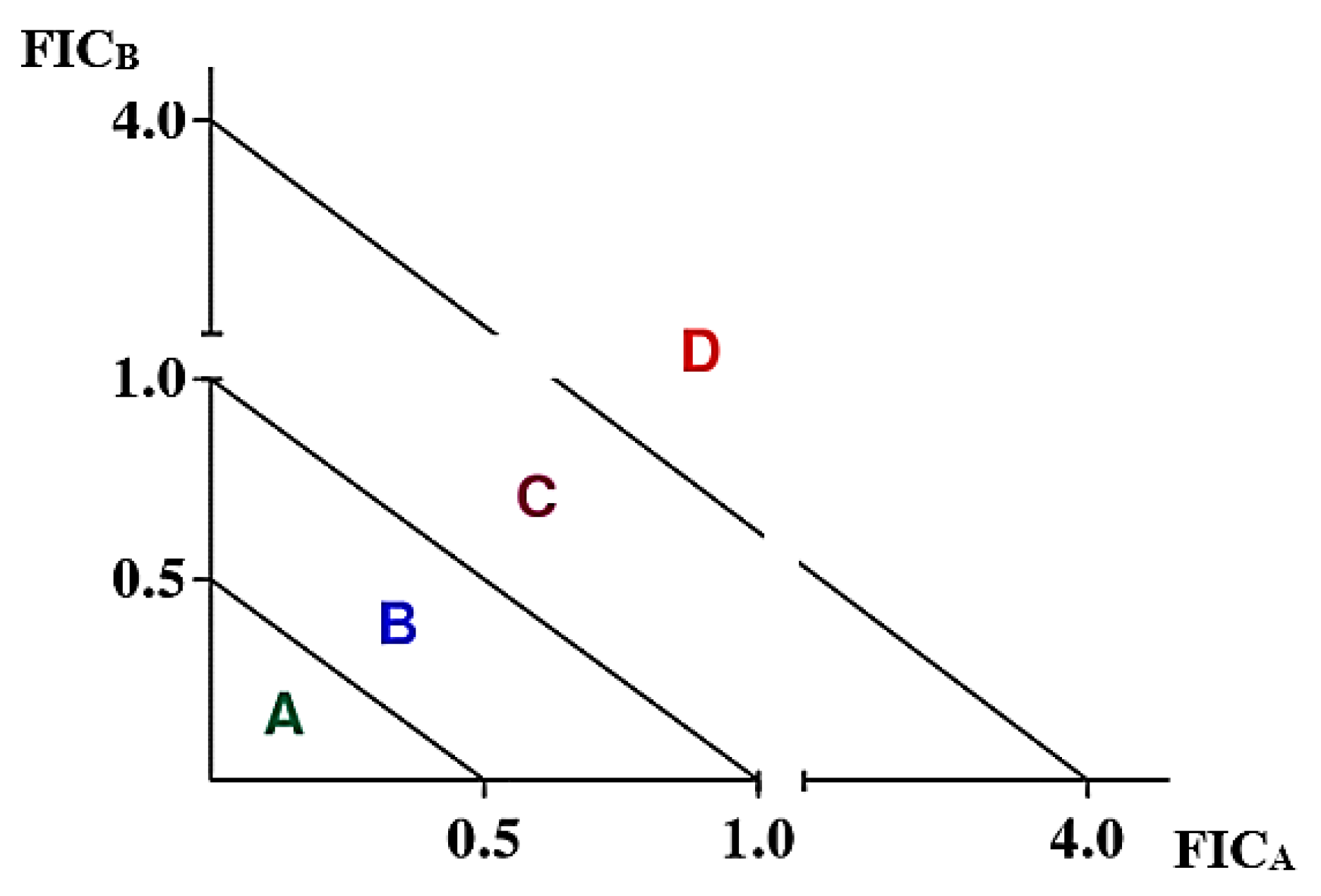

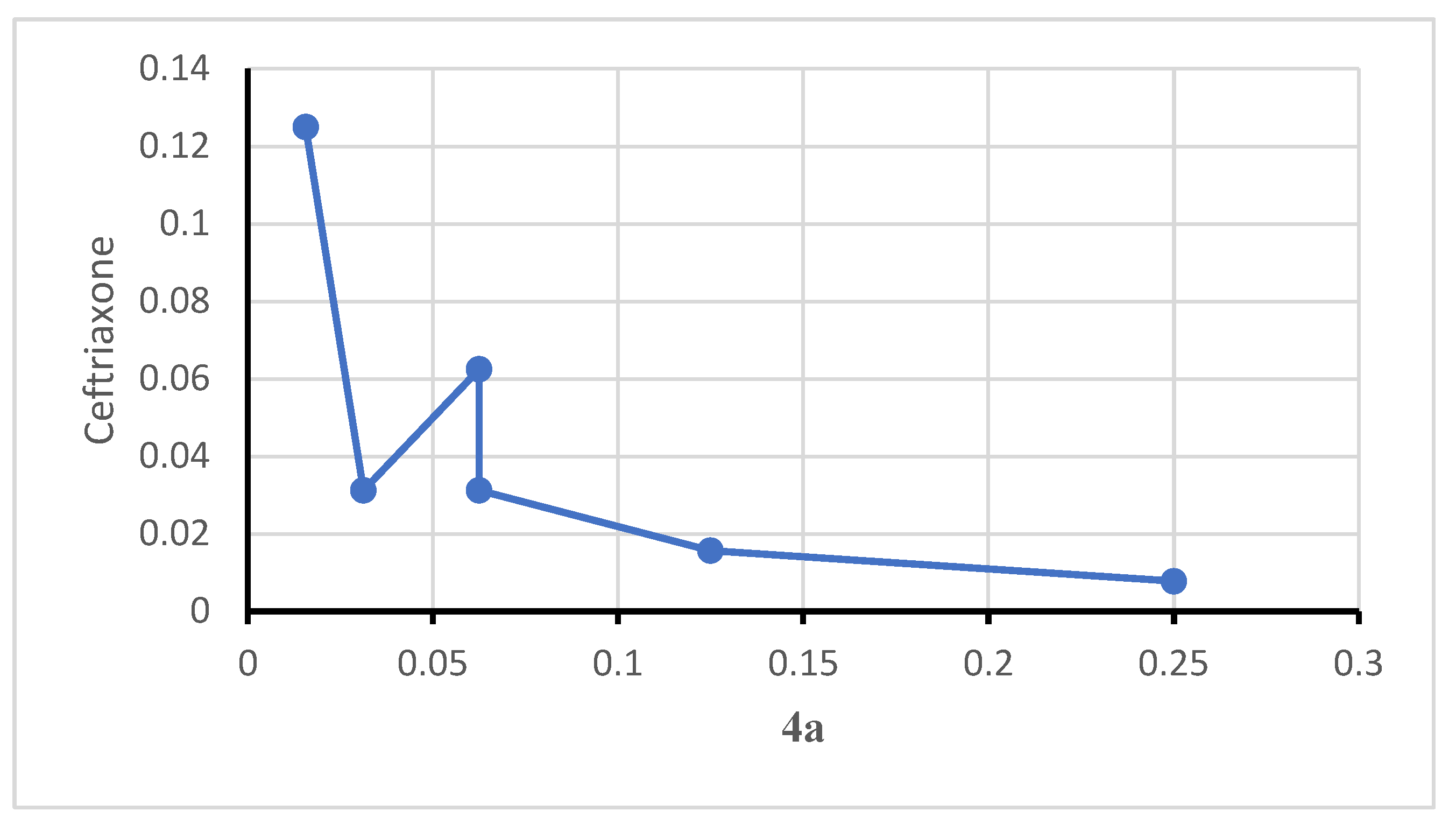

| Corresponding MICs wells | Conc. 4a (µg/mL) | Conc. Cef (µg/mL) | FIC 4a | FIC Cef | FICI |

| H3 | 3.125 | 0.097 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.26 |

| G4 | 1.562 | 0.195 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| F5 | 0.781 | 0.390 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| E5 | 0.781 | 0.781 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| F6 | 0.390 | 0.390 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| D7 | 0.195 | 1.562 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| D8 | 0.097 | 1.562 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Mean FICI (Interaction) | 0.14 (S) | ||||

| Corresponding MICs wells | Conc. 4a (µg/mL) | Conc. Cot (µg/mL) | FIC 4a | FIC cot | FICI |

| H3 | 3.125 | 0.097 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.26 |

| G3 | 3.125 | 0.195 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.27 |

| F4 | 1.562 | 0.390 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| E5 | 0.781 | 0.781 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| E6 | 0.390 | 0.781 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| E7 | 0.195 | 0.781 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| D8 | 0.097 | 1.562 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Mean FICI (Interaction) | 0.16 (S) | ||||

| Corresponding MICs wells | Conc. 4b (µg/mL) | Conc. Cot (µg/mL) | FIC 4b | FIC cot | FICI |

| H3 | 3.125 | 0.098 | 0.250 | 0.008 | 0.258 |

| G3 | 3.125 | 0.195 | 0.250 | 0.016 | 0.266 |

| G4 | 1.563 | 0.195 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.141 |

| G5 | 0.781 | 0.195 | 0.063 | 0.016 | 0.078 |

| F6 | 0.391 | 0.391 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.063 |

| E7 | 0.195 | 0.391 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.047 |

| E8 | 0.098 | 0.391 | 0.008 | 0.031 | 0.039 |

| Mean FICI (Interaction) | 0.127 (S) | ||||

| Corresponding MICs wells | Conc. 4b (µg/mL) | Conc. Cef (µg/mL) | FIC 4b | FIC Cef | FICI |

| H3 | 3.125 | 0.097 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.26 |

| G3 | 3.125 | 0.195 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.27 |

| F4 | 1.562 | 0.390 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| E5 | 0.781 | 0.781 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| E6 | 0.390 | 0.781 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| E7 | 0.195 | 0.781 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| E8 | 0.097 | 0.781 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Mean FICI (Interaction) | 0.15 (S) | ||||

| Combinations | MIC (µg/mL) on S. flexneri | HC50 (µg/mL) | SI (HC50/MIC50) |

| 4a-Cot | 2.5 | ˃200 | ˃80 |

| 4a-Cef | 1.25 | ˃200 | ˃160 |

| 4b-Cot | 0.625 | ˃200 | ˃320 |

| 4b-Cef | 0.625 | ˃200 | ˃320 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.062 | / | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).