Submitted:

15 January 2024

Posted:

16 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Bacterial strains and growth media

4.3. Chequerboard assay

4.4. Evaluation of combination effects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2016 Diarrhoeal Disease Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 1211-1228. [CrossRef]

- Kosek, M.; Bern, C.; Guerrant, R.L. The magnitude of the global burden of diarrhea from studies published 1992-2000. Bull World Health Organ 2003, 81, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diarrhoeal disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease. 2017 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Cooke, M.L. Causes and management of diarrhoea in children in a clinical setting. South Afr J Clin Nutr 2010, 23, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, F.; Shaheen, S.; Memon, Z.; Fatima, G. Culture and sensitivity patterns of various antibiotics used for the treatment of pediatric infectious diarrhea in children under 5 years of age: A tertiary care experience from Karachi. Int J Clin Med 2018, 9, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar, R.D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolhion, N.; Chassaing, B. When pathogenic bacteria meet the intestinal microbiota. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2016, 371:20150504. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, S.L; Finlay, B.B. Gut microbiota-mediated protection against diarrheal infections. J Travel Med 2017, 24, S39–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, B.A. Nosocomial diarrhea. Crit Care Clin 1998, 14, 329–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World health organization. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Yang, X.; Fei, B.; Leung, P.H.M.; Tao, X. Mechanistic study of synergistic antimicrobial effects between poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) oligomer and polyethylene glycol. Polymers 2020, 12, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Miller, R.; Lähnemann, D.; Schulenburg, H.; Ackermann, M.; Beardmore, R. The optimal deployment of synergistic antibiotics: a control-theoretic approach. J R Soc Interface 2012, 9, 2488–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doldán-Martelli, V.; Míguez, D.G. Synergistic interaction between selective drugs in cell populations models. PLoS One 2015, 10: e0117558. [CrossRef]

- Windiasti, G.; Feng, J.; Ma, L.; Hu, Y.; Hakeem, M.J.; Amoako, K.; Delaquis, P.; Lu, X. Investigating the synergistic antimicrobial effect of carvacrol and zinc oxide nanoparticles against Campylobacter jejuni. Food Control 2019, 96, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajuyigbe, O.O. Synergistic influence of tetracycline on the antibacterial activities of amoxicillin against resistant bacteria. J Pharm Allied Health Sci 2012, 2, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNASYN- ampicillin sodium and sulbactam sodium injection, powder, for solution Roerig. Updated October 2020. New York, NY 10017. Available online: https://labeling.pfizer.com/showlabeling.aspx?id=617 (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Khin-Maung, U.; Khin, M.; Nyunt-Nyunt, W.; Kyaw, A., Tin-U. Clinical trial of berberine in acute watery diarrhoea. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985, 291, 1601-1605. [CrossRef]

- Hamoud, R.; Reichling, J.; Wink, M. Synergistic antibacterial activity of the combination of the alkaloid sanguinarine with EDTA and the antibiotic streptomycin against multidrug resistant bacteria. J Pharm Pharmacol 2015, 67, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, B.; Hatton, C.K. 1999. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry Medicinal Plants. 2nd ed. Paris Secaucus N.J: Lavoisier Pub.; Intercept.

- Dey, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Chaudhury, M. Alkaloids From Apocynaceae: Origin, pharmacotherapeutic properties, and structure-activity studies, Editor(s): Atta-ur-Rahman. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry 2017, 52, 373–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C. The biochemistry, toxicology, and uses of the pharmacologically active phytochemicals: alkaloids, terpenes, polyphenols, and glycosides. J Food Pharm Sci 2019, 7, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croaker, A.; King, G.J.; Pyne, J.H.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Liu, L. Sanguinaria canadensis: Traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, H.; Dahan, M.; Soell, M. Effectiveness of a sanguinarine regimen after scaling and root planing. J Periodontol 1999, 70, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuete, V. Health Effects of Alkaloids from African Medicinal Plants. Toxicol survey of Afri med plants 2014, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

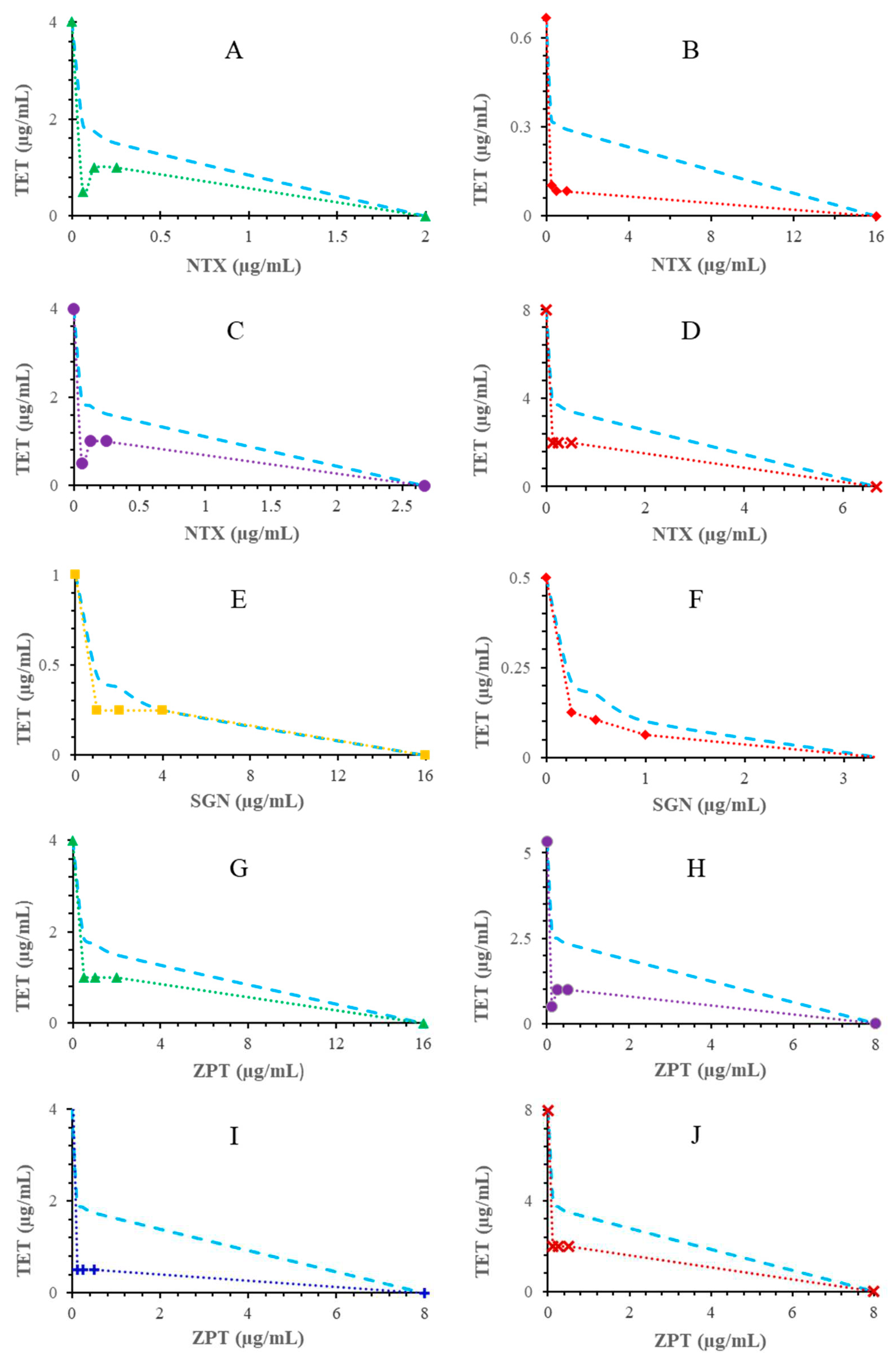

- Osei-Owusu, H.; Kudera, T.; Strakova, M.; Rondevaldova, J.; Skrivanova, E.; Novy, P.; Kokoska, L. In vitro selective combinatory effect of ciprofloxacin with nitroxoline, sanguinarine, and zinc pyrithione against diarrhea-causing and gut beneficial bacteria. Microbiol Spectr 2022, e0106322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresken, M.; Körber-Irrgang, B. In vitro activity of nitroxoline against Escherichia coli urine isolates from outpatient departments in Germany. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 7019–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, J.M; Bais, H.P.; Stermitz, F.R.; Thelen, G.C.; Callaway, R.M. Biogeographical variation in community response to root allelochemistry: novel weapons and exotic invasion. Ecol Lett 2004, 7, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Bingxiang, X.; Xiaopeng, W. Studies on active principles of Polyalthia nemoralis-I. The isolation and identification of natural zinc compound. Acta Chim Sin 1981, 39, 433–437. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, C.W.; Scheynius, A.; Heitman, J. Malassezia fungi are specialized to live on skin and associated with dandruff, eczema, and other skin diseases. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, C.; Wang, J.; Toi, M.J.; Lam, Y.I.; Goh. J.P.; Lee, S.M.; Dawson, T.L. Effect of zinc pyrithione shampoo treatment on skin commensal Malassezia. Med Mycol 2021, 59, 210-213. [CrossRef]

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "tetracycline". Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/science/tetracycline 2012 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Dwivedi, G.R.; Maurya, A.; Yadav, D.K; Singh, V.; Khan, F.; Gupta, M.K.; Singh, M.; Darokar, M.P.; Srivastava, S.K. Synergy of clavine alkaloid 'chanoclavine' with tetracycline against multi-drug-resistant E. coli. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2019, 37, 1307–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; Approved standard 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2020: Wayne, P. A. USA.

- Sirichoat, A.; Flórez, A.B; Vázquez, L.; Buppasiri, P.; Panya, M.; Lulitanond, V.; Mayo, B. Antibiotic resistance-susceptibility profiles of Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus spp. from the human vagina, and genome analysis of the genetic basis of intrinsic and acquired resistances. Front Microbiol 2020, 11:1438. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, A.; Lübke-Becker, A.; Heuwieser, W. Minimum inhibitory concentrations of frequently used antibiotics against Escherichia coli and Trueperella pyogenes isolated from uteri of postpartum dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2018, 101, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Walker, R.D.; Janes, M.E.; Prinyawiwatkul, W.; Ge, B. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus isolates from Louisiana Gulf and retail raw oysters. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 7096–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, I.; Wiedemann, B. An in-vitro study of the antimicrobial susceptibilities of Yersinia enterocolitica and the definition of a database. J Antimicrob Chemother 1999, 43, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Sherwood, J.S.; Logue, C.M. Antimicrobial resistance of Listeria spp. recovered from processed bison. Lett Appl Microbiol 2007, 44, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiyarov, R.S.; Bektemirov, A.M.; Ibadova, G.A.; Abdukhalilova, G.K.; Khodiev, A.V.; Bodhidatta, L.; Sethabutr, O.; Mason, C.J. Antimicrobial resistance patterns and prevalence of class 1 and 2 integrons in Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei isolated in Uzbekistan. Gut Pathog 2010, 2:18. [CrossRef]

- Kudera, T.; Doskocil, I.; Salmonova, H.; Petrtyl, M.; Skrivanova, E.; Kokoska, L. In vitro selective growth-inhibitory activities of phytochemicals, synthetic phytochemical analogs, and antibiotics against diarrheagenic/probiotic bacteria and cancer/normal intestinal cells. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13:233. [CrossRef]

- Omoya, F.O.; Ajayi, K.O. Synergistic effect of combined antibiotics against some selected multidrug resistant human pathogenic bacteria isolated from poultry droppings in Akure, Nigeria. Adv Microbiol 2016, 6, 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, I.; Roberts, M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2001, 65, 232–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, T.H. Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016, 6 :025387. [CrossRef]

- White, J.P.; Cantor, C.R. Role of magnesium in the binding of tetracycline to Escherichia coli ribosomes. J Mol Biol 1971, 58, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repac, A.D.; Parčina, M.; Gobin, I.; Petković, D.M. Chelation in antibacterial drugs: From nitroxoline to cefiderocol and beyond. Antibiotics 2022, 11:1105. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Flint, S.; Palmer, J. Magnesium and calcium ions: roles in bacterial cell attachment and biofilm structure maturation. Biofouling 2019, 35, :959-974. [CrossRef]

- Dinning AJ, Al-Adham IS, Austin P, Charlton M, Collier PJ. Pyrithione biocide interactions with bacterial phospholipid, head groups. J Appl Microbiol 1998, 85:132–140. [CrossRef]

- Obiang-Obounou, B.W.; Kang, O.H.; Choi, J.G.; Keum. J.H.; Kim, S.B.; Mun, S.H.; Shin, D.W.; Kim, K.W.; Park, C.B.; Kim, Y.G.; Han, S.H.; Kwon, D.Y. The mechanism of action of sanguinarine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Toxicol Sci 2011, 36, 277–283. [CrossRef]

- Shutter, M.C.; Akhondi, H. Tetracycline. [Updated 2022 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549905/.

- Poiger, H.; Schlatter, C. Interaction of cations and chelators with the intestinal absorption of tetracycline. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1979, 306, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, J.; Smith, L.P.; Gurney, M.; Lee, K.; Weinberg, W.G.; Longfield, J.N.; Tauber, W.B.; Karney, W.W. Comparison of single-dose tetracycline hydrochloride to conventional therapy of urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985, 27, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naber, K.G.; Niggemann, H.; Stein, G. Review of the literature and individual patients' data meta-analysis on efficacy and tolerance of nitroxoline in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14:628. [CrossRef]

- Becci, P.J.; Schwartz, H.; Barnes, H.H.; Southard, G.L. Short-term toxicity studies of sanguinarine and of two alkaloid extracts of Sanguinaria canadensis L. J Toxicol Environ Health 1987, 20, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS). Opinion on zinc pyrithione (ZPT) (P81) CAS N° 13463–41-7 submission III, Regulation 1223/2009, CAS 13463–41–7, preliminary version of 13 December 2019, final version of 03–04 March 2020, SCCS/1614/19. European Commission. Brussels. 13 December.

- Schwartz, J.R.; Shah, R.; Krigbaum, H.; Sacha, J.; Vogt, A.; Blume-Peytavi, U. New insights on dandruff/seborrhoeic dermatitis: the role of the scalp follicular infundibulum in effective treatment strategies. Br J Dermatol 2011, 165 Suppl 2, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; Approved standard 10th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Wayne, P.A. USA.

- Leber, A. synergism testing: Broth microdilution checkerboard and broth microdilution methods. In Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook, 4th ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cos, P.; Vlietinck, A.J.; Vanden Berghe, D.; Maes, L. Anti-infective potential of natural products: How to develop a stronger in vitro 'proof-of-concept'. J Ethnopharmacol 2006, 106, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, J.H.; Turnidge, J.D.; Washington, J.A. Antibacterial susceptibility tests: dilution and disk diffusion methods, p 1526–1543. In Murray P.R.; Baron, E.J.; Pfaller, M.A.; Tenover, F.C.; Yolken, R.H (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, 1999. Washington, DC.

- Okoliegbe, I.N.; Hijazi, K.; Cooper, K.; Ironside, C.; Gould, I.M. Antimicrobial synergy testing: Comparing the tobramycin and ceftazidime gradient diffusion methodology used in assessing synergy in cystic fibrosis-derived multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics 2021, 10:967. [CrossRef]

- Frankova, A.; Vistejnova, L.; Merinas-Amo, T.; Leheckova, Z.; Doskocil, I.; Wong Soon, J.; Kudera, T.; Laupua, F.; Alonso-Moraga, A.; Kokoska, L. In vitro antibacterial activity of extracts from Samoan medicinal plants and their effect on proliferation and migration of human fibroblasts. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 264:113220. [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID). EUCAST Definitive Document E. Def 1.2. Terminology relating to methods for the determination of susceptibility of bacteria to antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Infect 2000, 6, 503-508.

- Rakholiya, K.D.; Kaneria, M.J.; Chanda, S.V. Medicinal plants as alternative sources of therapeutics against multidrug-resistant pathogenic microorganisms based on their antimicrobial potential and synergistic properties. Editor(s): Rai, M.K.; Kon, K.V. Fighting multidrug resistance with herbal extracts, essential oils and their components. Academic Press, 2013, 165-179.

- Odds, F.C. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003, 52:1. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.M. Synergy and other interactions in phytomedicines. Phytomedicine 2001, 8, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteriuma | MICb alone | MIC of NTX (numbers in bold)/MIC of TET/FICIc of corresponding NTX-TET combination | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TET | NTX | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |||||||||

| E. faecalis | 1 | 16 | 0.031 | 2.031 | 0.031 | 1.031 | 0.031 | 0.531 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.375 | 0.25 | 0.313 | 1 | 1.031 | 1 | 1.016 |

| L. monocytogenes | 0.667 | 16 | 0.016 | 2.024 | 0.016 | 1.024 | 0.052 | 0.578 | 0.109 | 0.413 | 0.083 | 0.249 | 0.083 | 0.187 | 0.083 | 0.156 | 0.104 | 0.172 |

| 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | |||||||||||

| E. coli 0175:H7 | 4 | 2 | 0.063 | 4.016 | 0.063 | 2.016 | 0.063 | 1.016 | 1 | 0.75 | 4 | 1.25 | 1 | 0.375 | 1 | 0.313 | 0.5 | 0.157 |

| S. flexneri | 4 | 2.667 | 0.063 | 3.015 | 0.063 | 1.516 | 0.063 | 0.766 | 2.333 | 0.958 | 3 | 0.937 | 1 | 0.344 | 1 | 0.297 | 0.25 | 0.086 |

| V. parahaemolyticus | 2 | 2 | 0.016 | 4.008 | 0.016 | 2.008 | 0.016 | 1.008 | 0.016 | 0.508 | 0.5 | 0.50 | 0.5 | 0.375 | 0.5 | 0.313 | 0.5 | 0.282 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.031 | |||||||||||

| Y. enterocolitica | 8 | 6.667 | 0.031 | 0.604 | 1 | 0.425 | 2 | 0.400 | 2 | 0.325 | 2 | 0.287 | 2 | 0.269 | 2 | 0.259 | 2 | 0.255 |

| Bacteriuma | MICb alone | MIC of ZPT (numbers in bold)/MIC of TET/FICIc of corresponding ZPT-TET combination | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TET | ZPT | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | |||||||||

| S. flexneri | 5.333 | 8 | 0.063 | 2.012 | 0.063 | 1.012 | 1 | 0.688 | 1 | 0.438 | 1 | 0.313 | 1 | 0.250 | 1 | 0.219 | 0.5 | 0.109 |

| V. parahaemolyticus | 4 | 8 | 0.016 | 2.004 | 0.016 | 1.004 | 0.016 | 0.504 | 0.031 | 0.258 | 0.031 | 0.133 | 0.5 | 0.188 | 0.5 | 0.156 | 0.5 | 0.141 |

| 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | |||||||||||

| E. coli 0175:H7 | 4 | 16 | 0.063 | 0.516 | 0.25 | 0.313 | 1 | 0.375 | 1 | 0.313 | 1 | 0.281 | 2 | 0.516 | 2 | 0.508 | 1 | 0.254 |

| E. faecalis | 1 | 8 | 0.031 | 1.031 | 0.031 | 0.531 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 1.125 | 1 | 1.063 | 1 | 1.031 | 1 | 1.016 | 1 | 1.008 |

| Y. enterocolitica | 8 | 8 | 0.031 | 1.004 | 0.25 | 0.531 | 1 | 0.375 | 1 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.313 | 2 | 0.281 | 2 | 0.266 | 2 | 0.258 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | 0.031 | |||||||||||

| L. monocytogenes | 0.5 | 8 | 0.016 | 0.532 | 0.016 | 0.282 | 0.125 | 0.375 | 0.208 | 0.479 | 0.208 | 0.447 | 0.125 | 0.266 | 0.125 | 0.258 | 0.125 | 0.254 |

| Bacteriuma | MICb alone | MIC of SGN (numbers in bold)/MIC of TET/FICIc of corresponding SGN-TET combination | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TET | SGN | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| E. coli 0175:H7 | 4 | 128 | 0.25 | 0.563 | 4 | 1.25 | 4 | 1.125 | 4 | 1.063 | 4 | 1.031 | 4 | 1.016 | 2 | 0.508 | 2 | 0.504 |

| 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |||||||||||

| E. faecalis | 1 | 16 | 0.031 | 2.031 | 0.031 | 1.031 | 0.031 | 0.531 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.375 | 0.25 | 0.313 | 1 | 1.031 | 1 | 1.016 |

| Y. enterocolitica | 2 | 64 | 0.031 | 0.516 | 2 | 1.25 | 2 | 1.125 | 2 | 1.063 | 2 | 1.031 | 2 | 1.016 | 2 | 1.008 | 2 | 1.004 |

| 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | |||||||||||

| L. monocytogenes | 0.5 | 3.333 | 0.016 | 4.832 | 0.016 | 2.432 | 0.016 | 1.232 | 0.031 | 0.662 | 0.063 | 0.426 | 0.104 | 0.358 | 0.125 | 0.325 | 0.125 | 0.288 |

| 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.063 | |||||||||||

| S. flexneri | 1 | 16 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.25 | 1 | 1.125 | 1 | 1.063 | 0.5 | 0.531 | 0.5 | 0.516 | 1 | 1.008 | 1 | 1.004 |

| V. parahaemolyticus | 1 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.625 | 0.5 | 0.563 | 1 | 1.031 | 1 | 1.016 | 1 | 1.008 | 1 | 1.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).