Submitted:

07 May 2024

Posted:

08 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Isolates

2.2. Genomic DNA Extraction

2.3. Pathogenicity Islands (PAI) Detection

2.4. Plasmid DNA Extraction.

2.5. Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Associated Genes

2.6. Extended Spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) Producing Phenotype

2.7. Carbapenemase Producing Phenotype

2.8. Bacterial Adherence Patterns to HeLa Cells

2.9. Pathotypes Detection

2.10. Multiplex PCR for Dominant Sequence Types (STs) in EXPEC Isolates

2.11. Enterobacteriaceae Repetitive Intergenic Consensus (ERIC) PCR

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

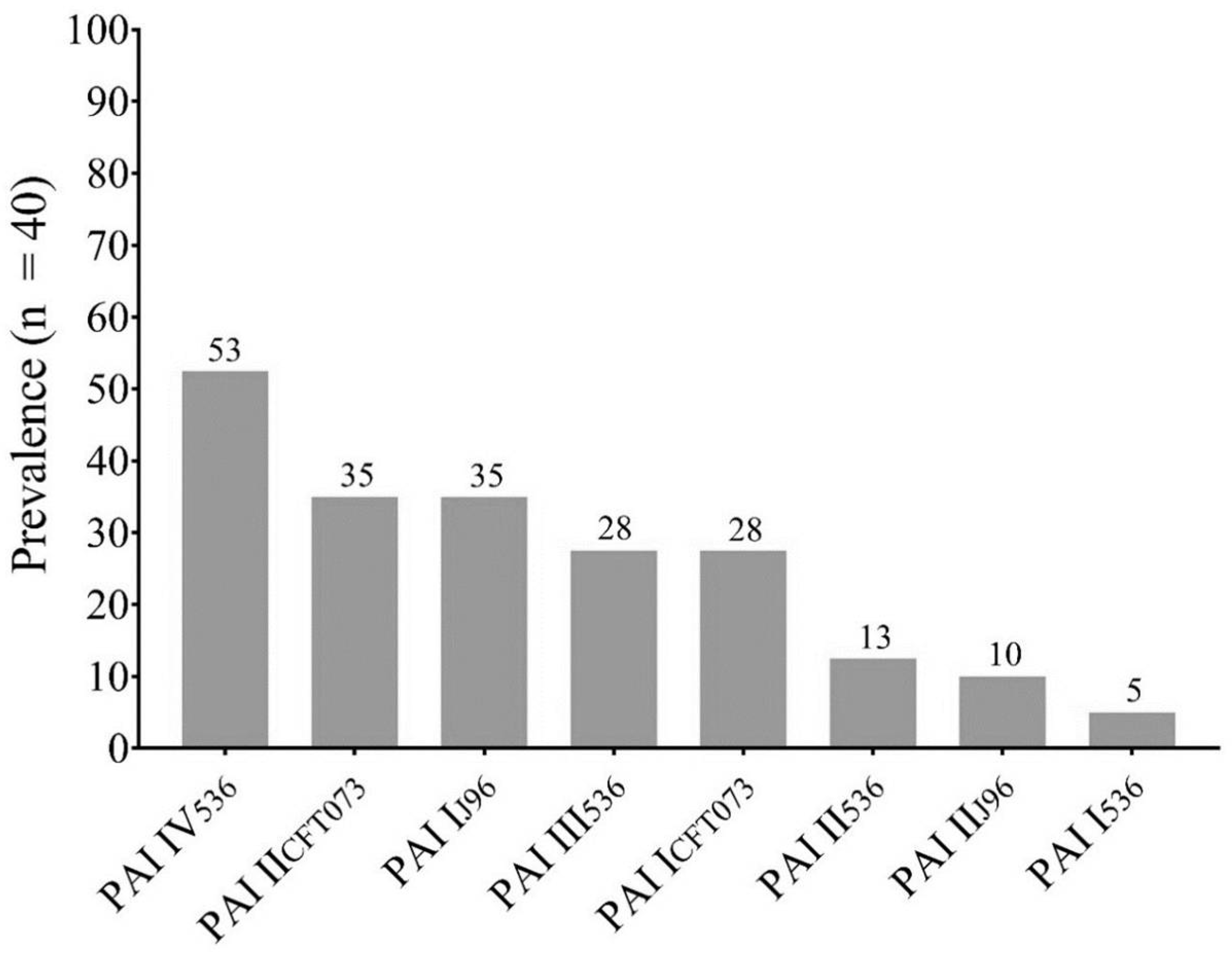

3.1. Clinical Isolates of E. coli from UTI Cases in Mexico Harbor Pathogenicity Islands

3.2. Clinical Isolates of E. coli Are ESBL Producers

3.3. Carbapenem Resistance is Mediated by Carbapenemases Production

3.4. Clinical Isolates Harbored Antibiotic Resistance Genes

β-lactams

Aminoglycosides or Fluoroquinolones

3.5. Plasmids of Clinical Isolates are Correlated with Resistance Genes Prevalence

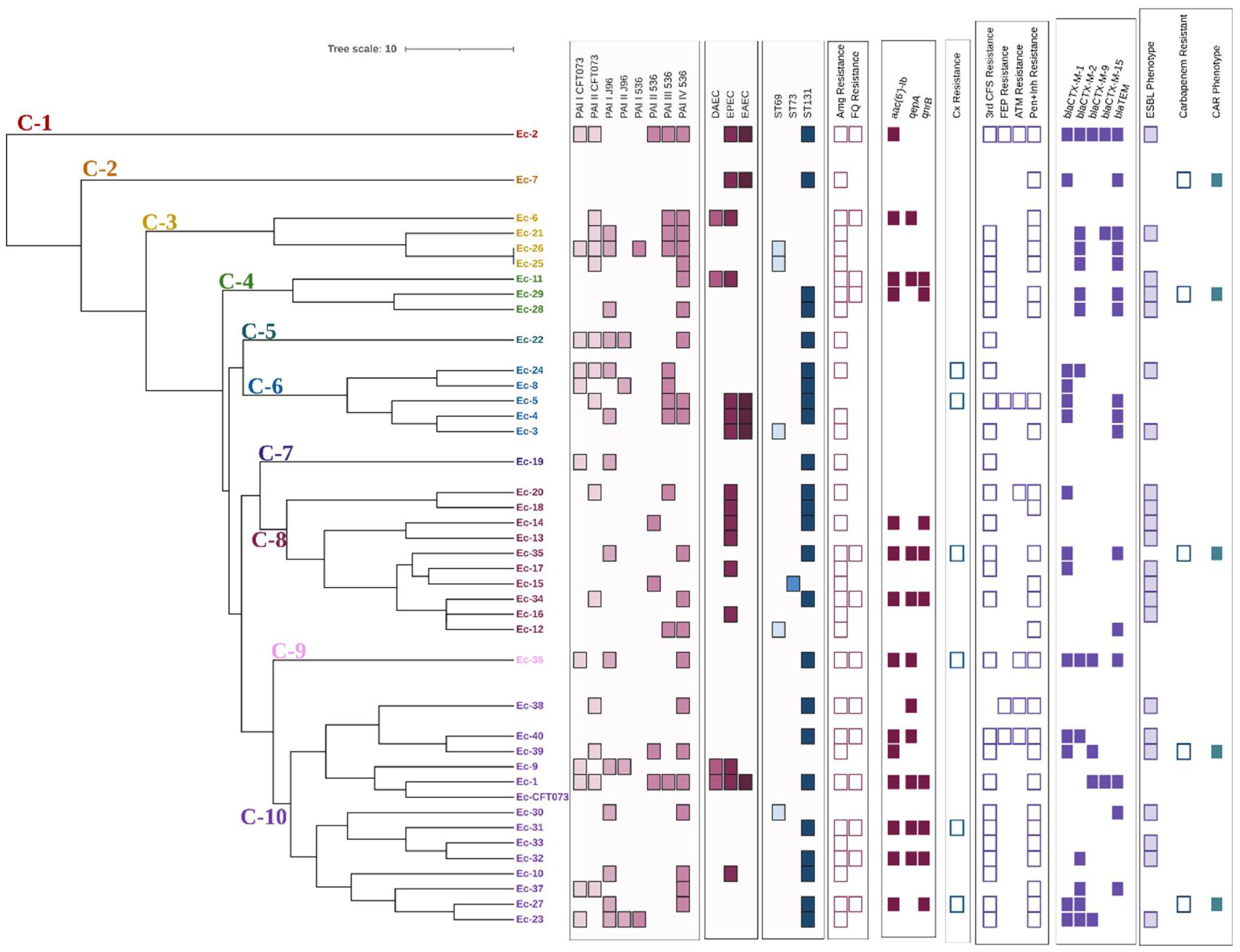

3.6. ST131 Is the most Prevalent Clonal Group

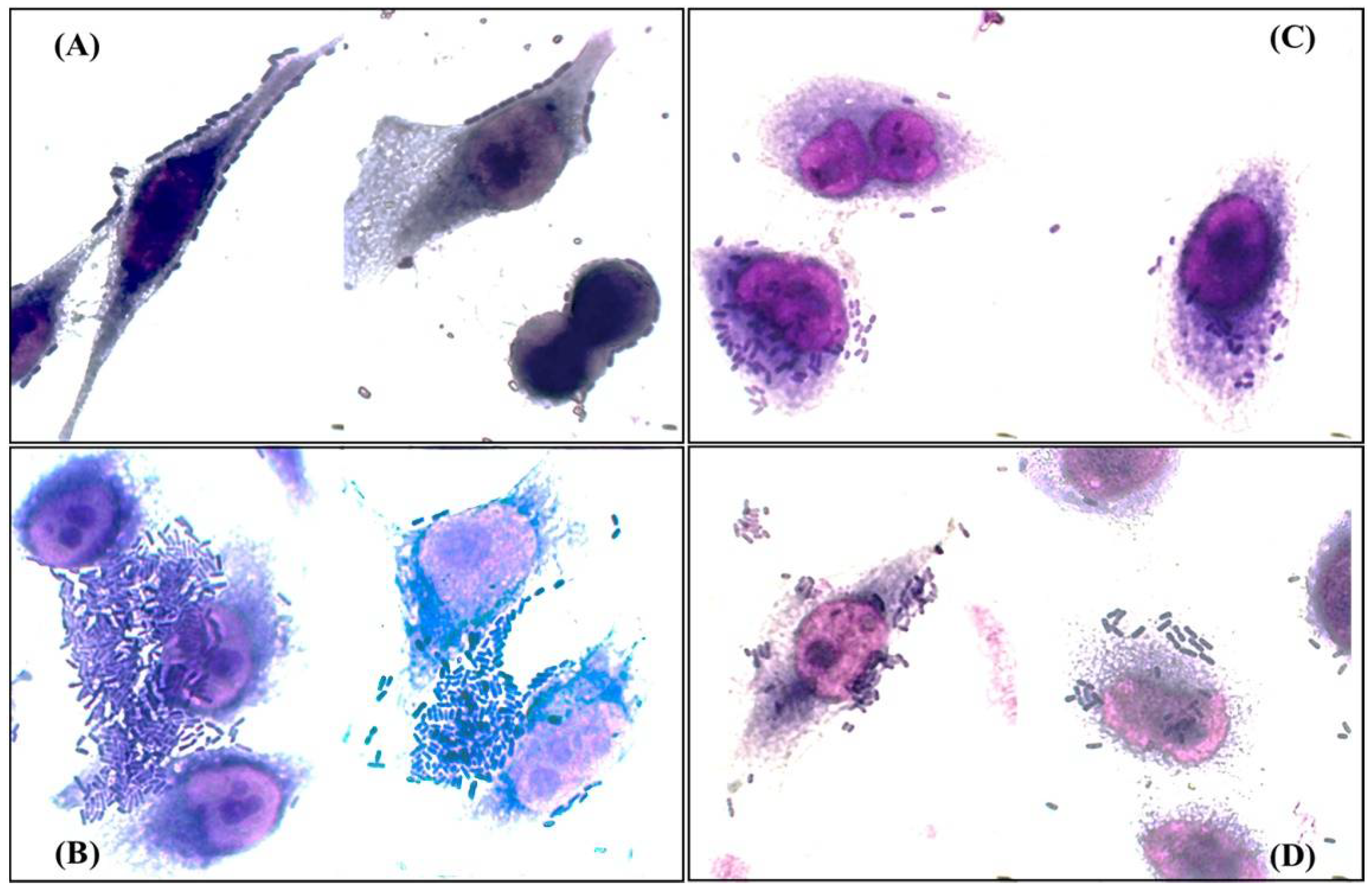

3.7. Clinical Isolates Show Mixed Adherence Patterns, Including some Associated with Diarrheagenic Pathotypes of E. coli

3.8. Clinical Isolates have Molecular Markers Associated with DEC Pathotypes

3.9. ERIC Fingerprint Pattern in Clinical Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Croxen, M.A.; Law, R.J.; Scholz, R.; Keeney, K.M.; Wlodarska, M.; Finlay, B.B. Recent Advances in Understanding Enteric Pathogenic E. coli. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013, 26, 822–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, T.A.; Johnson, J.R. Proposal for a New Inclusive Designation for Extraintestinal Pathogenic Isolates of E. coli: ExPEC. J Infect Dis 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mireles, A.L.; Walker, J.N.; Caparon, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Urinary Tract Infections: Epidemiology, Mechanisms of Infection and Treatment Options. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015, 13, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros-Monrreal, M.G.; Mendez-Pfeiffer, P.; Barrios-Villa, E.; Arenas-Hernández, M.M.P.; Enciso-Martínez, Y.; Sepúlveda-Moreno, C.O.; Bolado-Martínez, E.; Valencia, D. Uropathogenic E. coli in Mexico, an Overview of Virulence and Resistance Determinants: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Med Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyles, C.; Boerlin, P. Horizontally Transferred Genetic Elements and Their Role in Pathogenesis of Bacterial Disease. Veterinary Pathology 2014, 51, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samei, A.; Haghi, F.; Zeighami, H. Distribution of Pathogenicity Island Markers in Commensal and Uropathogenic E. coli Isolates. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2016, 61, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Hensel, M. Pathogenicity Islands in Bacterial Pathogenesis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004, 17, 14–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabate, M.; Moreno, E.; Perez, T.; Andreu, A.; Prats, G. Pathogenicity Island Markers in Commensal and Uropathogenic E. coli Isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006, 12, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desvaux, M.; Dalmasso, G.; Beyrouthy, R.; Barnich, N.; Delmas, J.; Bonnet, R. Pathogenicity Factors of Genomic Islands in Intestinal and Extraintestinal E. coli. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Monrreal, M.G.; Arenas-Hernández, M.M.P.; Barrios-Villa, E.; Juarez, J.; Álvarez-Ainza, M.L.; Taboada, P.; De la Rosa-López, R.; Bolado-Martínez, E.; Valencia, D. Bacterial Morphotypes as Important Trait for Uropathogenic E. coli Diagnostic; a Virulence-Phenotype-Phylogeny Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amábile-Cuevas, C.F. Antibiotic Resistance in Mexico: A Brief Overview of the Current Status and Its Causes. J Infect Dev Ctries 2010, 4, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros-Monrreal, M.G.; Arenas-Hernández, M.M.P.; Enciso-Martínez, Y.; Martinez de la Peña, C.F.; Rocha-Gracia, R. del C.; Lozano-Zarain, P.; Navarro-Ocaña, A.; Martínez-Laguna, Y.; de la Rosa-López, R. Virulence and Resistance Determinants of Uropathogenic E. coli Strains Isolated from Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Women from Two States in Mexico. Infect Drug Resist 2020, 13, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Méndez, M. Reservoirs of CTX-M Extended Spectrum β -Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Microbiol. Exp 2019, 7, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.F.; De Oliveira Martins, P.; De Melo, A.B.F.; Da Silva, R.C.R.M.; De Paulo Martins, V.; Pitondo-Silva, A.; De Campos, T.A. Multidrug Resistance Dissemination by Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli Causing Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infection in the Central-Western Region, Brazil. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2016, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Estrada, L.I.; Ruíz-Rosas, M.; Molina-López, J.; Parra-Rojas, I.; González-Villalobos, E.; Castro-Alarcón, N. Relación Entre Factores de Virulencia, Resistencia a Antibióticos y Los Grupos Filogenéticos de E. coli Uropatógena En Dos Localidades de México. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2017, 35, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavala-Cerna, M.G.; Segura-Cobos, M.; Gonzalez, R.; Zavala-Trujillo, I.G.; Navarro-Perez, S.F.; Rueda-Cruz, J.A.; Satoscoy-Tovar, F.A. The Clinical Significance of High Antimicrobial Resistance in Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F.A. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles of Bacteria Causing Urinary Tract Infections in Mexico: Single-Centre Experience with 10 Years of Results. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018, 14, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Mukherjee, M. Incidence and Risk of Co-Transmission of Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Genes in Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Uropathogenic E. coli: A First Study from Kolkata, India. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018, 14, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, L.P.; Cooles, S.W.; Osborn, M.K.; Piddock, L.J. V; Woodward, M.J. Antibiotic Resistance Genes, Integrons and Multiple Antibiotic Resistance in Thirty-Five Serotypes of Salmonella enterica Isolated from Humans and Animals in the UK. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2004, 53, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Jacobo, V.; Ramírez-Díaz, M.; Silva-Sánchez, J.; Cervantes, C. Resistencia Bacteriana a Quinolonas: Determinantes Codificados En Plásmidos. REB. Revista de educación bioquímica 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bielaszewska, M.; Schiller, R.; Lammers, L.; Bauwens, A.; Fruth, A.; Middendorf, B.; Schmidt, M.A.; Tarr, P.I.; Dobrindt, U.; Karch, H.; et al. Heteropathogenic Virulence and Phylogeny Reveal Phased Pathogenic Metamorphosis in E. coli O2: H6. EMBO Mol Med 2014, 6, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Moreno, E.; Caporal-Hernandez, L.; Mendez-Pfeiffer, P.A.; Enciso-Martinez, Y.; De la Rosa López, R.; Valencia, D.; Arenas-Hernández, M.M.P.; Ballesteros-Monrreal, M.G.; Barrios-Villa, E. Characterization of Diarreaghenic E. coli Strains Isolated from Healthy Donors, Including a Triple Hybrid Strain. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.I.; McQuillan, J.; Taiwo, M.; Parks, R.; Stenton, C.A.; Morgan, H.; Mowlem, M.C.; Lees, D.N. A Highly Specific E. coli QPCR and Its Comparison with Existing Methods for Environmental Waters. Water Res 2017, 126, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreón, E. Estudio Molecular de La Resistencia y Virulencia de Cepas de E. coli Productoras de β-Lactamasas de Espectro Extendido Aisladas de Vegetales Crudos., Benemerita Universidad Autonoma de Puebla, 2019.

- Sambrook, J. [Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual; 2012; Vol. 33; ISBN 9781936113415.

- Eftekhar, F.; Seyedpour, S.M. Prevalence of Qnr and Aac(6’)-Ib-Cr Genes in Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella Pneumoniae from Imam Hussein Hospital in Tehran. Iran J Med Sci 2015, 40, 515–521. [Google Scholar]

- Garza-González, E.; Bocanegra-Ibarias, P.; Bobadilla-del-Valle, M.; Ponce-de-León-Garduño, L.A.; Esteban-Kenel, V.; Silva-Sánchez, J.; Garza-Ramos, U.; Barrios-Camacho, H.; López-Jácome, L.E.; Colin-Castro, C.A.; et al. Drug Resistance Phenotypes and Genotypes in Mexico in Representative Gram-Negative Species: Results from the Infivar Network. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0248614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Ramos, U.; Davila, G.; Gonzalez, V.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.; López-Collada, V.R.; Alcantar-Curiel, D.; Newton, O.; Silva-Sanchez, J. The BlaSHV-5 Gene Is Encoded in a Compound Transposon Duplicated in Tandem in Enterobacter cloacae. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2009, 15, 878–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robicsek, A.; Strahilevitz, J.; Sahm, D.F.; Jacoby, G.A.; Hooper, D.C. Qnr Prevalence in Ceftazidime-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Isolates from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 2872–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamane, K.; Wachino, J.; Suzuki, S.; Arakawa, Y. Plasmid-Mediated QepA Gene among E. coli Clinical Isolates from Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008, 52, 1564–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2023.

- Mansan-Almeida, R.; Pereira, A.L.; Giugliano, L.G. Diffusely Adherent E. colistrains Isolated from Children and Adults Constitute Two Different Populations. BMC Microbiol 2013, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Angeles, M.G. Principales Características y Diagnóstico de Los Grupos Patógenos de E. coli. Salud Publica Mex 2002, 44, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, K.R.S.; Fabbricotti, S.H.; Fagundes-Neto, U.; Scaletsky, I.C.A. Single Multiplex Assay to Identify Simultaneously Enteropathogenic, Enteroaggregative, Enterotoxigenic, Enteroinvasive and Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli Strains in Brazilian Children. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2007, 267, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, J.; Franke, S.; Schmidt, H.; Schwarzkopf, A.; Wieler, L.H.; Baljer, G.; Beutin, L.; Karch, H. Nucleotide Sequence Analysis of Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) Adherence Factor Probe and Development of PCR for Rapid Detection of EPEC Harboring Virulence Plasmids. J Clin Microbiol 1994, 32, 2460–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumith, M.; Day, M.; Ciesielczuk, H.; Hope, R.; Underwood, A.; Reynolds, R.; Wain, J.; Livermore, D.M.; Woodford, N. Rapid Identification of Major E. coli Sequence Types Causing Urinary Tract and Bloodstream Infections. J Clin Microbiol 2015, 53, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versalovic, J.; Koeuth, T.; Lupski, R. Distribution of Repetitive DNA Sequences in Eubacteria and Application to Finerpriting of Bacterial Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (ITOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros-Monrreal, M.G.; Arenas-Hernández, M.M.P.; Barrios-Villa, E.; Juarez, J.; Álvarez-Ainza, M.L.; Taboada, P.; De la Rosa-López, R.; Bolado-Martínez, E.; Valencia, D. Bacterial Morphotypes as Important Trait for Uropathogenic E. coli Diagnostic; a Virulence-Phenotype-Phylogeny Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, C.; Mazel, D.; Hochhut, B.; Middendorf, B.; Le Roux, F.; Carniel, E.; Dobrindt, U.; Hacker, J. Delineation of the Recombination Sites Necessary for Integration of Pathogenicity Islands II and III into the E. coli 536 Chromosome. Mol Microbiol 2008, 68, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navidinia, M.; Najar Peerayeh, S.; Fallah, F.; Bakhshi, B.; Adabian, S.; Alimehr, S.; Gholinejad, Z. Distribution of the Pathogenicity Islands Markers (PAIs) in Uropathogenic E. Coli Isolated from Children in Mofid Children Hospital. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis 2013, 1, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittò, M.; Berger, M.; Klotz, L.; Dobrindt, U. Sub-Inhibitory Concentrations of SOS-Response Inducing Antibiotics Stimulate Integrase Expression and Excision of Pathogenicity Islands in Uropathogenic E. coli Strain 536. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2020, 310, 151361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozeh, F.; Soleimani-Moorchekhorti, L.; Zibaei, M. Evaluation of Pathogenicity Islands in Uropathogenic E. coli Isolated from Patients with Urinary Catheters. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 2017, 11, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrindt, U.; Blum-Oehler, G.; Nagy, G.; Schneider, G.; Johann, A.; Gottschalk, G.; Hacker, J. Genetic Structure and Distribution of Four Pathogenicity Islands (PAI I536 to PAI IV536) of Uropathogenic E. coli Strain 536. Infect Immun 2002, 70, 6365–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G.; Dobrindt, U.; Brüggemann, H.; Nagy, G.; Janke, B.; Blum-Oehler, G.; Buchrieser, C.; Gottschalk, G.; Emödy, L.; Hacker, J. The Pathogenicity Island-Associated K15 Capsule Determinant Exhibits a Novel Genetic Structure and Correlates with Virulence in Uropathogenic E. coli Strain 536. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 5993–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, S.; Métayer, V.; Gay, E.; Madec, J.-Y.; Haenni, M. Characterization of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-Carrying Plasmids and Clones of Enterobacteriaceae Causing Cattle Mastitis in France. Vet Microbiol 2013, 162, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua-Contreras, G.L.; Monroy-Pérez, E.; Bautista, A.; Reyes, R.; Vicente, A.; Vaca-Paniagua, F.; Díaz, C.E.; Martínez, S.; Domínguez, P.; García, L.R.; et al. Multiple Antibiotic Resistances and Virulence Markers of Uropathogenic E. coli from Mexico. Pathog Glob Health 2018, 112, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Méndez, M. Caracterización Molecular y Patrón de Susceptibilidad Antimicrobiana de E. coli Productora de β;-Lactamasas de Espectro Extendido En Infección Del Tracto Urinario Adquirida En La Comunidad. Revista chilena de infectología 2018, 35, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántar-Curiel, M.D.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M.; Varona-Bobadilla, H.J.; Gayosso-Vázquez, C.; Jarillo-Quijada, M.D.; Frías-Mendivil, M.; Sanjuan-Padrón, L.; Santos-Preciado, J.I. Risk Factors for Extended-Spectrumb-Lactamases-Producing E. coli urinary Tract Infections in a Tertiary Hospital. Salud Publica Mex 2015, 57, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Miranda, V.; Garza-Ramos, U.; Bolado-Martínez, E.; Navarro-navarro, M.; Félix-Murray, K.R.; Carmen, M.; Sanchez-Martinez, G.; Dúran-Bedolla, J.; Silva-Sanchez, J.; Garza-Ramos, U.; et al. ESBL-Producing E. coli and Klebsiella Pneumoniae from Health-Care Institutions in Mexico. Journal of Chemotherapy 2020, 0, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayo Morfín-Otero, Soraya Mendoza-Olazarán, Jesús Silva-Sánchez, Eduardo Rodríguez-Noriega, Jorge Laca-Díaz, Perla Tinoco-Carrillo, Luis Petersen, Perla López, Fernando Reyna-Flores, Dolores Alcantar -Curiel, Ulises Garza-Ramos. Characterization of Enterobacteriaceae Isolates Obtained from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Mexico, Which Produce Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase. 2013, 19, 378–383. [CrossRef]

- Reyna-Flores, F.; Barrios, H.; Garza-Ramos, U.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Rojas-Moreno, T.; Uribe-Salas, F.J.; Fagundo-Sierra, R.; Silva-Sanchez, J. Molecular Epidemiology of E. coli O25b-ST131 Isolates Causing Community-Acquired UTIs in Mexico. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013, 76, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua-Contreras, G.L.; Monroy-Pérez, E.; Díaz-Velásquez, C.E.; Uribe-García, A.; Labastida, A.; Peñaloza-Figueroa, F.; Domínguez-Trejo, P.; García, L.R.; Vaca-Paniagua, F.; Vaca, S. Whole-Genome Sequence Analysis of Multidrug-Resistant Uropathogenic Strains of E. coli from Mexico. Infect Drug Resist 2019, 12, 2363–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkovic, D.; Morris, A.J.; Dyet, K.; Bakker, S.; Heffernan, H. Plasmid-Mediated AmpC Beta-Lactamase-Producing E. coli Causing Urinary Tract Infection in the Auckland Community Likely to Be Resistant to Commonly Prescribed Antimicrobials. N Z Med J 2015, 128, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, B.; Haque, A.; Qasim, M.; Ali, A.; Sarwar, Y. High Prevalence of Extensively Drug Resistant and Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamases (ESBLs) Producing Uropathogenic E. coli Isolated from Faisalabad, Pakistan. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2023, 39, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Castillo, F.Y.; Moreno-Flores, A.C.; Avelar-González, F.J.; Márquez-Díaz, F.; Harel, J.; Guerrero-Barrera, A.L. An Evaluation of Multidrug-Resistant E. coli Isolates in Urinary Tract Infections from Aguascalientes, Mexico: Cross-Sectional Study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2018, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robicsek, A.; Strahilevitz, J.; Jacoby, G.A.; Macielag, M.; Abbanat, D.; Hye Park, C.; Bush, K.; Hooper, D.C. Fluoroquinolone-Modifying Enzyme: A New Adaptation of a Common Aminoglycoside Acetyltransferase. Nat Med 2006, 12, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasson, I.; Cavallaro, A.; Bergo, C.; Richter, S.N.; Palù, G. Prevalence of Aac(6’)-Ib-Cr Plasmid-Mediated and Chromosome-Encoded Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Enterobacteriaceae in Italy. Gut Pathog 2011, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raherison, S.; Jove, T.; Gaschet, M.; Pinault, E.; Tabesse, A.; Torres, C.; Ploy, M.-C. Expression of the Aac(6′)-Ib-Cr Gene in Class 1 Integrons. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seni, J.; Falgenhauer, L.; Simeo, N.; Mirambo, M.M.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Matee, M.; Rweyemamu, M.; Chakraborty, T.; Mshana, S.E. Multiple ESBL-Producing E. coli Sequence Types Carrying Quinolone and Aminoglycoside Resistance Genes Circulating in Companion and Domestic Farm Animals in Mwanza, Tanzania, Harbor Commonly Occurring Plasmids. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraschek, K.; Malekzadah, J.; Malorny, B.; Käsbohrer, A.; Schwarz, S.; Meemken, D.; Hammerl, J.A. Characterization of QnrB-Carrying Plasmids from ESBL- and Non-ESBL-Producing E. coli. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, L.W. Pandemic Lineages of Extraintestinal Pathogenic E. coli. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2014, 20, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira da Silva, R.C.R.; de Oliveira Martins Júnior, P.; Gonçalves, L.F.; de Paulo Martins, V.; de Melo, A.B.F.; Pitondo-Silva, A.; de Campos, T.A. Ciprofloxacin Resistance in Uropathogenic E. coli Isolates Causing Community-Acquired Urinary Infections in Brasília, Brazil. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2017, 9, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, M.; Ünlü, Ö.; İstanbullu Tosun, A. Detection of O25b-ST131 Clone, CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-15 Genes via Real-Time PCR in E. coli Strains in Patients with UTIs Obtained from a University Hospital in Istanbul. J Infect Public Health 2019, 12, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Ewers, C.; Nandanwar, N.; Guenther, S.; Jadhav, S.; Wieler, L.H.; Ahmed, N. Multiresistant Uropathogenic E. coli from a Region in India Where Urinary Tract Infections Are Endemic: Genotypic and Phenotypic Characteristics of Sequence Type 131 Isolates of the CTX-M-15 Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Lineage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012, 56, 6358–6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiatti, T.B.; Santos, F.F.; Santos, A.C.M.; Nascimento, J.A.S.; Silva, R.M.; Carvalho, E.; Sinigaglia, R.; Gomes, T.A.T. Genetic and Virulence Characteristics of a Hybrid Atypical Enteropathogenic and Uropathogenic E. coli (AEPEC/UPEC) Strain. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, R.H.S.; Dias, R.C.B.; Orsi, H.; de Lira, D.R.P.; Vieira, M.A.; dos Santos, L.F.; Ferreira, A.M.; Rall, V.L.M.; Mondelli, A.L.; Gomes, T.A.T.; et al. Characterization of Uropathogenic E. coli Reveals Hybrid Isolates of Uropathogenic and Diarrheagenic (UPEC/DEC) E. coli. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Ama, A. Estudio de Las Propiedades de Virulencia En Cepas de E. coli Uropatógena; Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla: Puebla, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.C. de M.; Santos, F.F.; Silva, R.M.; Gomes, T.A.T. Diversity of Hybrid- and Hetero-Pathogenic E. coli and Their Potential Implication in More Severe Diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PAI Profile | Isolate ID |

|---|---|

| PAI I 536, PAI I CFT073 | 25 |

| PAI I 536, PAI I J96, PAI II J96, PAI I CFT073 | 23 |

| PAI I 536, PAI III 536, PAIV 536, PAI J96, PAI I CFT073, PAI II CF073 | 26 |

| PAI I J96, PAI I CFT073 | 19 |

| PAI I J96, PAII J96, PAI I CFT073 | 9 |

| PAI II 536 | 14,15 |

| PAI II 536, PAI III 536, PAI IV 536, PAI I CFT073, PAI II CFT073 | 1, 2 |

| PAI II 536, PAI IV 536, PAI II CFT073 | 39 |

| PAI III 536, PAI II CFT073 | 20 |

| PAI III 536, PAI II J96, PAI I CFT073 | 8 |

| PAI III 536, PAI IV 536 | 12 |

| PAI III 536, PAI IV 536, PAI I J96, PAI II CFT073 | 21 |

| PAI III 536, PAI IV 536, PAI II CFT073 | 5,6 |

| PAI III 536, PAI IV 536, PAI J96 | 4 |

| PAI III 536, PAI J96, PAI I CFT073, PAI II CFT073 | 24 |

| PAI IV 536, PAI II CFT073 | 34 |

| PAI IV 536 | 11 |

| PAI IV 536, PAI I CFT073, PAI II CFT073 | 37 |

| PAI IV 536, PAI I J96 | 10, 27, 28, 30, 35 |

| PAI IV 536, PAI I J96, PAI I CFT073 | 36 |

| PAI IV 536, PAI I J96, PAI II J96, PAI I CFT073, PAI II CFT073 | 22 |

| PAI IV 536, PAI II CFT073 | 25, 38 |

| Negatives | 3, 4,13,16-18,29,31-33,40 |

| ID | Antibiotic Resistance* | ESBL Phenotype | ESBL Profile | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CX | AMC | AMS | CFZ | CTX | CRO | FEP | ATM | CTX | CFZ | CRO | FEP | ATM | ||

| 1 | R | R | R | |||||||||||

| 5 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| 10 | R | R | ||||||||||||

| 12 | R | R | R | |||||||||||

| 19 | R | R | ||||||||||||

| 22 | R | R | ||||||||||||

| 25 | R | R | R | |||||||||||

| 26 | R | R | R | |||||||||||

| 27 | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| 31 | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||||

| 35 | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||||

| 36 | R | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| 21 | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | CFZ, CRO | ||||||

| 3 | R | R | R | R | + | CRO | ||||||||

| 11 | R | R | R | + | CTX | |||||||||

| 13 | R | R | + | CTX | ||||||||||

| 14 | R | R | + | CTX | ||||||||||

| 15 | R | R | + | CTX | ||||||||||

| 16 | R | R | + | CTX | ||||||||||

| 17 | R | + | CTX | |||||||||||

| 18 | R | R | R | + | CTX | |||||||||

| 23 | R | R | R | + | CTX | |||||||||

| 20 | R | R | R | R | + | + | CTX, ATM | |||||||

| 40 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | CTX, ATM | ||||

| 24 | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | CTX, CFZ | ||||||

| 30 | R | R | R | R | + | + | CTX, CFZ | |||||||

| 28 | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | + | CTX, CFZ, CRO | |||||

| 32 | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | + | CTX, CFZ, CRO | |||||

| 34 | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | + | CTX, CFZ, CRO | |||||

| 2 | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | CTX, CFZ, CRO,FEP, ATM | |

| 29 | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | + | + | + | CTX, CFZ, CRO,FEP, ATM | |||

| 39 | R | R | R | R | + | + | CTX, CRO | |||||||

| 33 | R | R | R | R | R | + | + | + | CTX, CRO, ATM | |||||

| 38 | R | R | R | R | + | + | FEP, ATM | |||||||

| Feature | ST73 %(n = 1) |

ST69 %(n = 5) |

STNT %(n = 10) |

ST131 %(n= 24) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAI III536 | 0 | 40 (2) | 20 (2) | 29.2 (7) | |

| PAI IV536 | 0 | 80 (4) | 50 (5) | 50 (12) | |

| PAI IICFT073 | 0 | 40 (2) | 40 (4) | 33.3 (8) | |

| PAI II536 | 100 (1) | 0 | 10 (1) | 13 (3) | |

| PAI IJ96 | 0 | 40 (2) | 20 (2) | 42 (10) | |

| PAI ICFT073 | 0 | 20 (1) | 20 (2) | 33.3 (8) | |

| PAI I536 | 0 | 20 (1) | 0 | 4.2 (1) | |

| PAI IIJ96 | 0 | 0 | 10 (1) | 13 (3) | |

| Aminoglycosides | 100 (1) | 80 (4) | 70 (7) | 83.3 (20) | |

| Fluoroquinolones | 0 | 0 | 30 (3) | 50 (12) * | 0.05 |

| Cotrimoxazole | 100 (1) | 60 (3) | 40 (4) | 46 (11) | |

| Cephamycins | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 (6) | |

| 3st Cephalosporins | 100 (1) | 100 (5) | 70 (7) | 83.3 (20) | |

| 4th Cephalosporins | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (4) | |

| Monobactams | 0 | 0 | 20 (2) | 33.3 (8) | |

| Pen-Inh | 100 (1) | 100 (5) | 70 (7) | 79.2 (19) | |

| Carbapenems | 0 | 0 | 10 (1) | 17 (4) | |

| ESBL Phenotype | 100 (1) | 40 (2) | 70 (7) | 50 (12) | |

| CAR Phenotype | 0 | 0 | 10 (1) | 17 (4) | |

| blaCTX-M 1 y 8 | 0 | 0 | 40 (4) | 58.3 (14)* | 0.005 |

| blaCTX-M-9 | 0 | 0 | 10 (1) | 17 (4)* | 0.02 |

| blaTEM | 0 | 100 (5)* | 20 (2) | 38 (9) | |

| blaCTX-M-2 | 100 (1) | 60 (3) | 30 (3) | 46 (11) | |

| blaCTX-M-15 | 0 | 0 | 10 (1) | 8.3 (2)* | 0.05 |

| qepA | 0 | 0 | 20 (2) | 33.3 (8)* | 0.001 |

| aac(6')-Ib | 0 | 0 | 30 (3) | 46 (11)* | 0.002 |

| qnrB | 0 | 0 | 10 (1) | 33.3 (8)* | <0.001 |

| ID | Pattern | Profile | PAI Profile | Pathotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bs/Lo | pCVD432, eaeA, daaE, bfpA |

PAI III536, PAI IV536, PAI IICFT073, PAI II536, PAI ICFT073 |

UPEC/EPEC/DAEC/EAEC |

| 2 | Bs/Dif | pCVD432, bfpA | PAI III536, PAI IV536, PAI IICFT073, PAI II536, PAI ICFT073 |

UPEC/EAEC/EPEC |

| 3 | Bs/Lo/Ag | pCVD432, bfpA | - | UPEC/EAEC/EPEC |

| 4 | Bs/Lo | pCVD432, bfpA | PAI III536, PAI IV536, PAIIJ96 | UPEC/EAEC/EPEC |

| 5 | Ag | pCVD432, bfpA | PAI III536, PAI IV536, PAI IICFT073 | UPEC/EAEC/EPEC |

| 6 | Bs/Lo/Di | daaE, bfpA | PAI III536, PAI IV536, PAI IICFT073 | UPEC/DAEC/EPEC |

| 7 | Bs | pCVD432, bfpA | - | UPEC/EAEC/EPEC |

| 8 | Bs/Lo | - | PAI III536, PAI ICFT073, PAI IIJ96 | UPEC |

| 9 | Bs/Ag | daaE, bfpA | PAI IJ96, PAI ICFT073, PAI IIJ96 | UPEC/DAEC/EPEC |

| 10 | Bs/Lo | bfpA | PAI IV536, PAIIJ96 | UPEC/EPEC |

| 11 | Bs | daaE, bfpA | PAI IV536 | UPEC/DAEC/EPEC |

| 12 | Lo | - | PAI III536, PAI IV536 | UPEC |

| 13 | Ag/Lo | bfpA | - | UPEC/EPEC |

| 14 | Bs | bfpA | PAI II536 | UPEC/EPEC |

| 15 | Bs | - | PAI II536 | UPEC |

| 16 | Ag/Bs/Lo | bfpA | - | UPEC/EPEC |

| 17 | Bs | bfpA | - | UPEC/EPEC |

| 18 | Bs | bfpA | - | UPEC/EPEC |

| 19 | Bs/Ag/Lo | - | PAI IJ96, PAI ICFT073 | UPEC |

| 20 | Bs/Lo/Di | bfpA | PAI III536, PAI IICFT073 | UPEC/EPEC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).