Submitted:

07 May 2024

Posted:

07 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Cultures

2.2. Retroviral Constructs

2.3. Transduction of the NIH 3T3 Cells

2.4. Magnetic Selection of Transduced Cells

2.5. Flow Cytometry

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

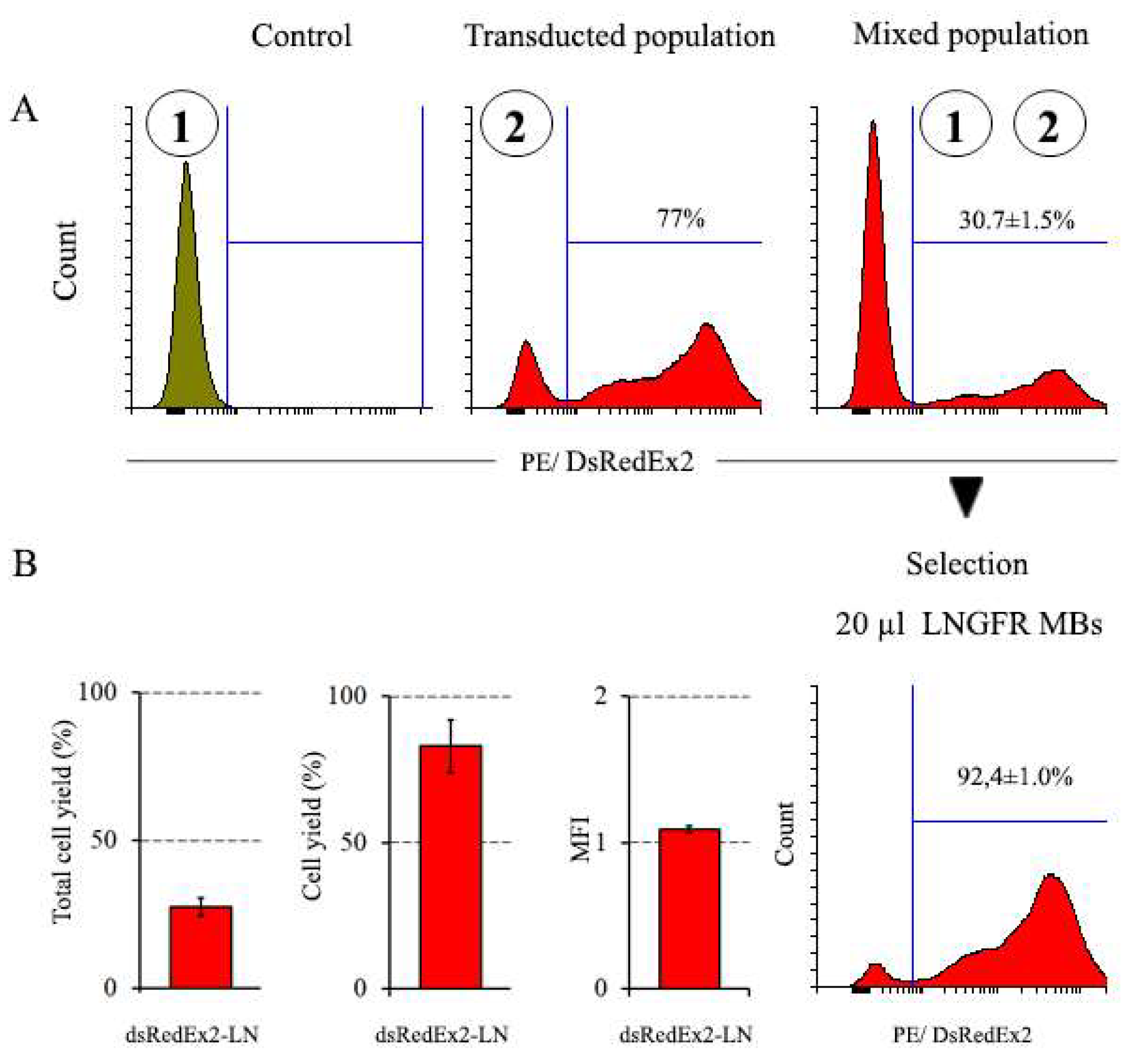

3.1. Retroviral Constructs

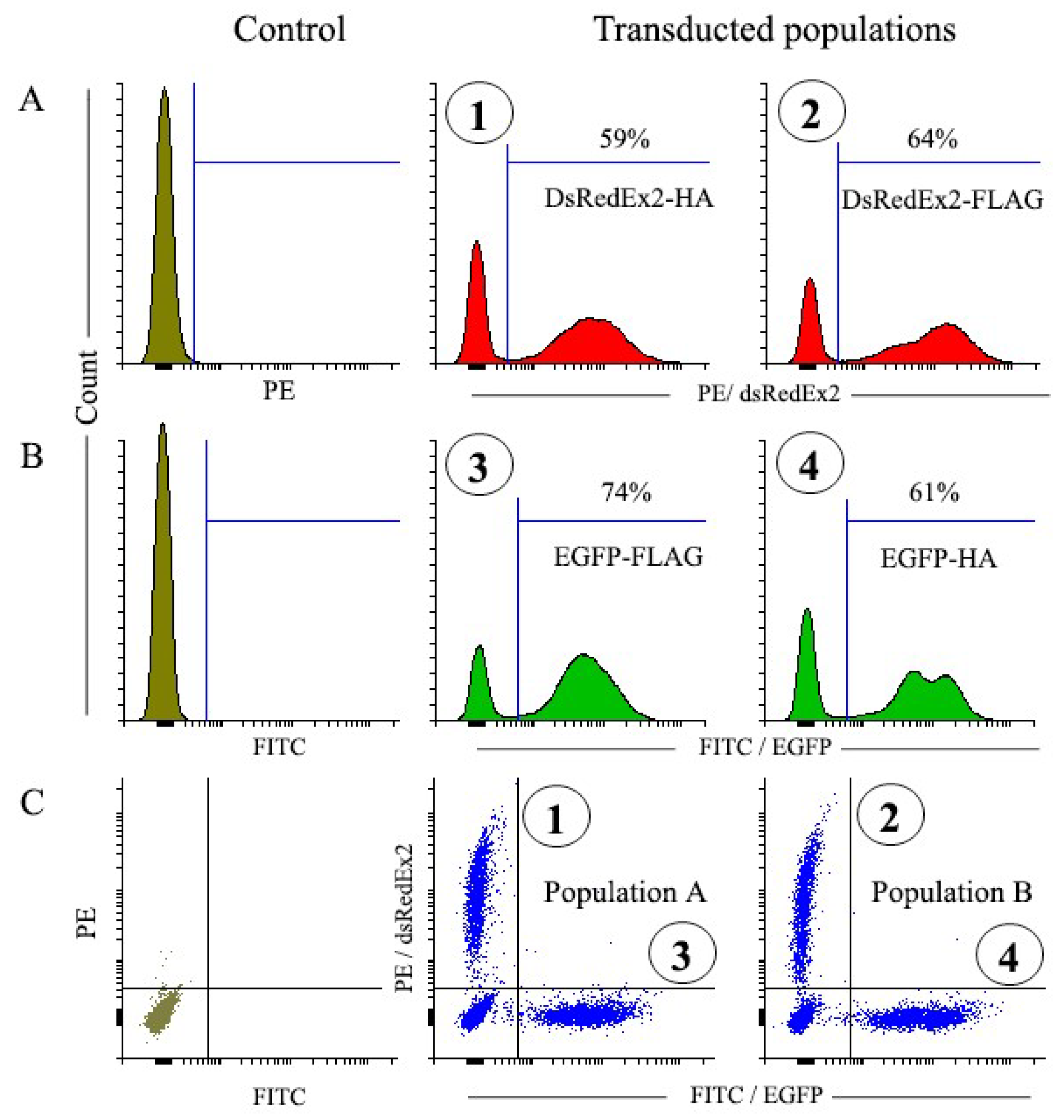

3.2. Transduction of NIH 3T3 Cells

3.3. Magnetic Selection of NIH 3T3 Transduced Cells

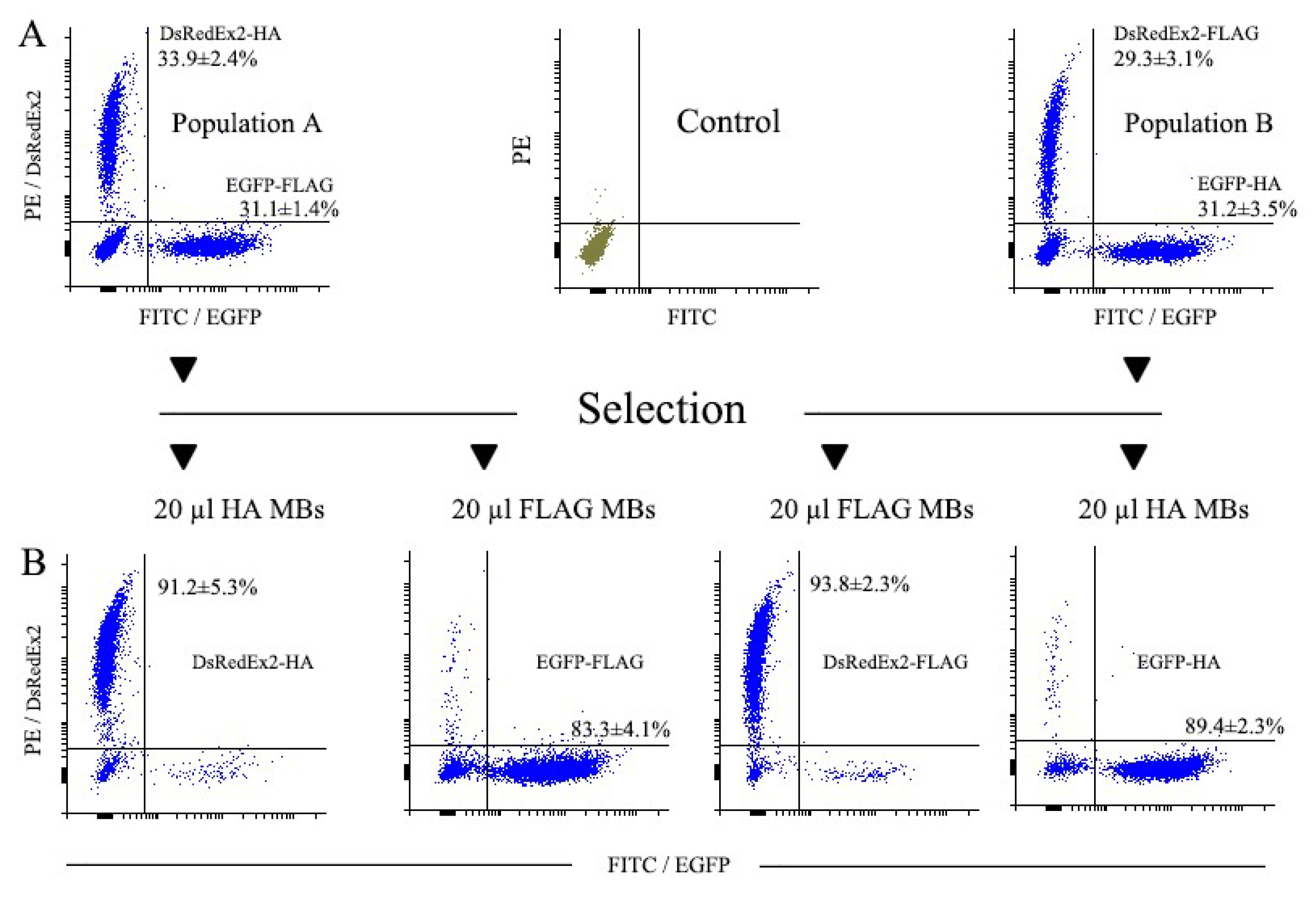

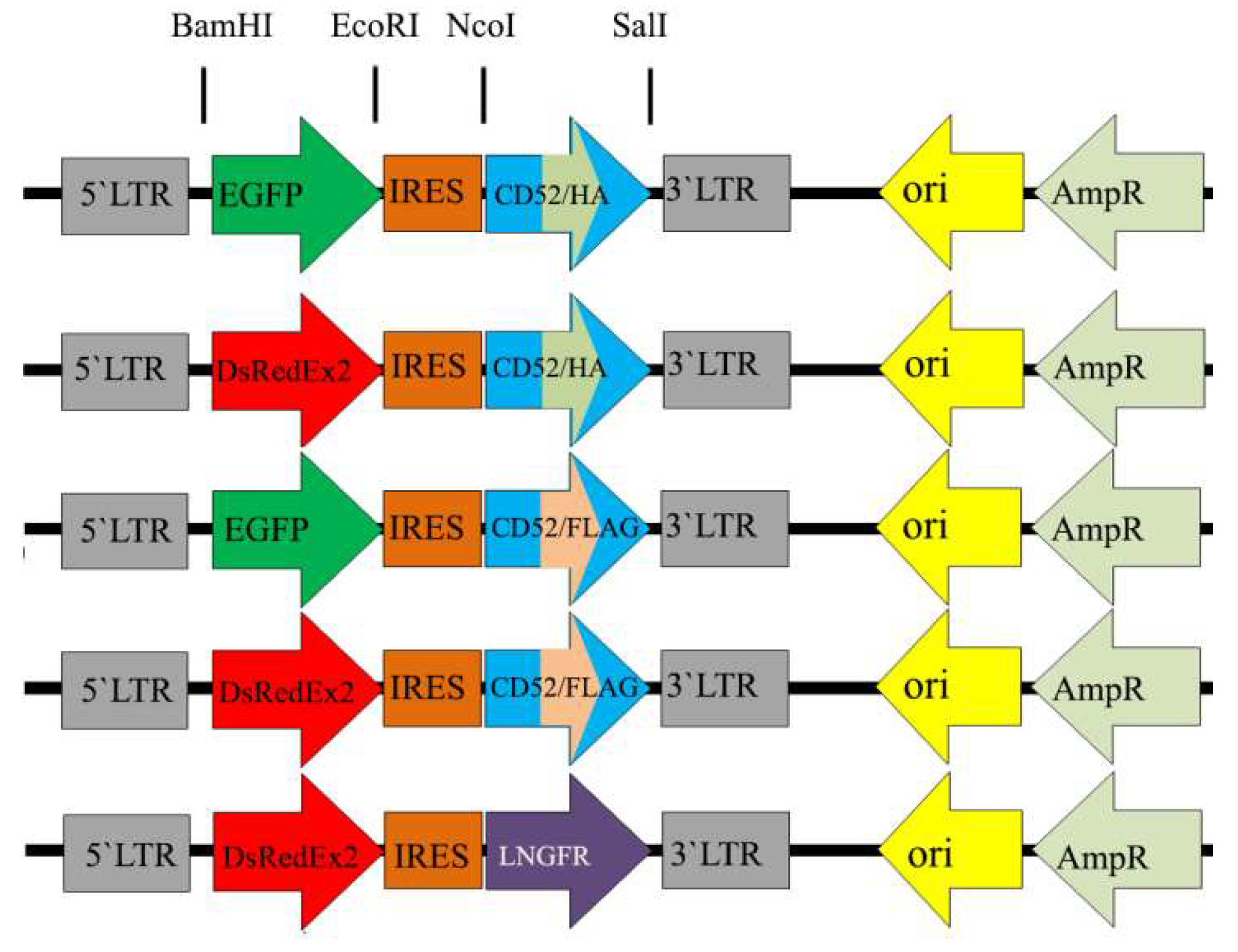

3.3.1. Magnetic Selection of FLAG+ and HA+ Cells

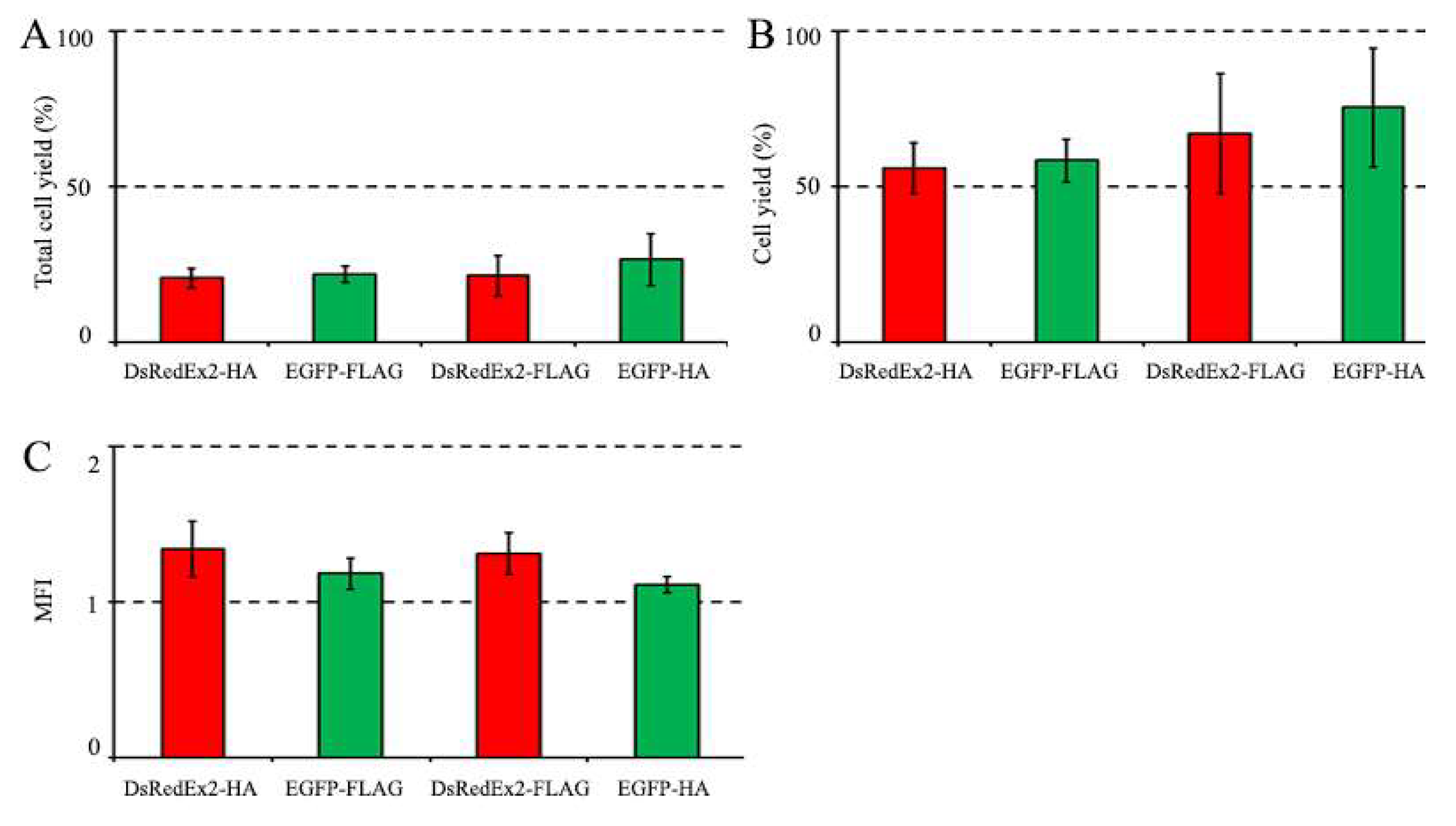

3.3.2. Magnetic Selection of LNGFR+ Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Wynter, E.A.; Coutinho, L.H.; Pei, X.; Marsh, J.C.; Hows, J.; Luft, T.; Testa, N.G. Comparison of Purity and Enrichment of CD34+ Cells From Bone Marrow, Umbilical Cord and Peripheral Blood (Primed for Apheresis) Using Five Separation Systems. Stem Cells 1995, 13, 5. 524-532. [CrossRef]

- Dainiak, M.B.; Kumar, A.; Galaev, I.Yu.; Mattiasson, B. Methods in cell separations. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2007, 106, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouffe, B.D.; Murthy, S.K.; Lewis, L.H. Fundamentals and Application of Magnetic Particles in Cell Isolation and Enrichment. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78, 016601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenea-Robin, M.; Marchalot, J. Basic principles and recent advances in magnetic cell separation. Magnetochemistry 2022, 8, 11. [CrossRef]

- Amos, P.J.; Bozkulak, E.C.; Qyang, Y. Methods of Cell Purification: A Critical Juncture for Laboratory Research and Translational Science. Cells Tissues Organs 2012, 195, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, R.M.; Kingston, R.E. Selection of transfected mammalian cells. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2009, 86:9.5.1-9.5.13. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, B.; Radbruch, A.; Kümmel, T.; Wickenhauser, C.; Korb, H.; Hansmann, M.; Thiele, J.; Fischer, R. Magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS)—a new immunomagnetic method for megakaryocytic cell isolation: comparison of different separation techniques. European Journal of Haematology 1994, 5, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutermaster, B.A.; Darling, E.M. Considerations for high-yield, high-throughput cell enrichment: fluorescence versus magnetic sorting. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wan, J. Methodological comparison of FACS and MACS isolation of enriched microglia and astrocytes from mouse brain. J. Immunol. Methods 2020, 486, 112834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M,Y.; Lufkin, T. Development of the "Three-step MACS": a novel strategy for isolating rare cell populations in the absence of known cell surface markers from complex animal tissue. J. Biomol. Tech. 2012, 23, 2, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Lin, S.; Ahmed, S.; Angers, S.; Sargent, E.H.; Kelley, S.O. Nanoparticle Amplification Labeling for High-Performance Magnetic Cell Sorting. Nano Lett. 2022, 12, 4774–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakova, N.; Kandarakov, O.; Belyavsky, A. Selection of cell populations with high or low surface marker expression using magnetic sorting. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Liu, Q.; He, W.; Ong, K.; Liu, X.; Gao, B. An efficient vector system to modify cells genetically. PLoS ONE, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, H.; Matsumoto, Y. Cell-surface streptavidin fusion protein for rapid selection of transfected mammalian cells. Gene 2007, 2, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, N.J.; Peden, A.A.; Lehner, P.J. Antibody-free magnetic cell sorting of genetically modified primary human CD4+ T cells by one-step streptavidin affinity purification. PLoS ONE 2014, 9(10):e111437. [CrossRef]

- Gaines, P.; Wojchowski, D.M. pIRES-CD4t, a dicistronic expression vector for MACS-or FACS-based selection of transfected cells. Biotechniques 1999, 4, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.; Groebner, M.; Franz, W.M. Magnetic cell sorting purification of differentiated embryonic stem cells stably expressing truncated human CD4 as surface marker. Stem Cells 2005, 23, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, W.L.; Kocman, I.; Agrawal, V.; Rahn, H-P. ; Besser, D.; Gossen, M. Homogeneity and persistence of transgene expression by omitting antibiotic selection in cell line isolation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 17, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, T.M.; Rettig, W.J.; Chesa, P.G.; Green, S.H.; Mena, A.C.; Old, L.J. Expression of human nerve growth factor receptor on cells derived from all three germ layers. Exp. Cell Res. 1988, 2, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Duan, X.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wen, N.; Smith, A.J.; Zhao, W.; Jin, Y. Isolation of neural crest-derived stem cells from rat embryonic mandibular processes. Biol. Cell 2006, 10, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirici, N.; Soligo, D.; Bossolasco, P.; Servida, F.; Lumini, C.; Deliliers, G.L. Isolation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by anti-nerve growth factor receptor antibodies. Exp. Hematol. 2002, 7, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barilani, M.; Banfi, F.; Sironi, S.; Ragni, E.; Guillaumin, S.; Polveraccio, F.; Rosso, L.; Moro, M.; Astori, G.; Pozzobon, M.; Lazzari, L. Low-affinity Nerve Growth Factor Receptor (CD271) Heterogeneous Expression in Adult and Fetal Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, S.; Skorska, A.; Lux, C.A.; Steinhoff, G.; David, R.; Gaebel, R. Angiogenic Potential of Bone Marrow Derived CD133+ and CD271+ Intramyocardial Stem Cell Trans-Plantation Post MI. Cells 2020, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.J.P.; Faroni, A.; Barrow, J.R.; Soul, J.; Reid, A.J. The angiogenic potential of CD271+ human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäck, L.M.; Noack, S.; Weist, R.; Jagodzinski, M.; Krettek, C.; Buettner, M.; Hoffmann, A. Analysis of surface protein expression in human bone marrow stromal cells: new aspects of culture-induced changes, inter-donor differences and intracellular expression. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 24, 3226–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, G.G.; Atashroo, D.A.; Maan, Z.N.; Hu, M.S.; Zielins, E.R.; Tsai, J.M.; Duscher, D.; Paik, K.; Tevlin, R.; Marecic, O.; Wan, D.C.; Gurtner, G.C.; Longaker, M.T. High-Throughput Screening of Surface Marker Expression on Undifferentiated and Differentiated Human-Derived Stromal Cells. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2015, 21, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Liang, S. Several affinity tags commonly used in chromatographic purification. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2013, 581093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafuente-González, E.; Guadaño-Sánchez, M.; Urriza-Arsuaga, I.; Urraca, J.L. Core-Shell Magnetic Imprinted Polymers for the Recognition of FLAG-Tagpeptide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandemoortele, G.; Eyckerman, S.; Gevaert, K. Pick a Tag and Explore the Functions of Your Pet Protein. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 10, 1078-1090.

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, T.; Shan, Y.; Pan, G. Generation of RYBP FLAG-HA knock-in human embryonic stem cell line through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination. Stem Cell Res. 2022, 62, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zotova, A.; Pichugin, A.; Atemasova, A.; Knyazhanskaya, E.; Lopatukhina, E.; Mitkin, N.; Holmuhamedov, E.; Gottikh, M.; Kuprash, D.; Filatov, A.; Mazurov, D. Isolation of gene-edited cells via knock-in of short glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored epitope tags. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grützkau, A.; Radbruch, A. Small but mighty: how the MACS-technology based on nanosized superparamagnetic particles has helped to analyze the immune system within the last 20 years. Cytometry A 2010, 77, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plouffe, B.D.; Murthy, S.K.; Lewis, L.H. Fundamentals and application of magnetic particles in cell isolation and enrichment: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78, 016601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yu, G.; Wang, D.; Guo, S.; Shan, F. Comparison of the purity and vitality of natural killer cells with different isolation kits. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 1875–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino-Ramos, D.; Lule, S.; Mahjoum, S.; Ughetto, S.; Bragg, D.C.; Pereira de Almeida, L.; Breakefield, X.O.; Breynea, K. Using genetically modified extracellular vesicles as a non-invasive strategy to evaluate brain-specific cargo. Biomaterials 2022, 281, 121366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scheme . | Total yield (%) |

Cell Yield (%) |

Purity (%) |

MFI change* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DsRedExp2-HA | 20.5±3.2 | 55.9±8.2 | 91.2±5.3 | 1.34±0.18 |

| EGFP-FLAG | 21.7±2.5 | 58.3±6.9 | 83.3±4.1 | 1.18±0.10 |

| DsRedExp2-FLAG | 21.2±6.6 | 67.0±19.3 | 93.8±2.3 | 1.31±0.14 |

| EGFP-HA | 26.5±8.4 | 74.5±19.2 | 89.4±2.3 | 1.11±0.05 |

| DsRedExp2-LNGFR | 27.5±3.0 | 82.9±9.0 | 92.4±1.0 | 1.09±0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).