Submitted:

02 May 2024

Posted:

07 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Plasticity in Granule Cells

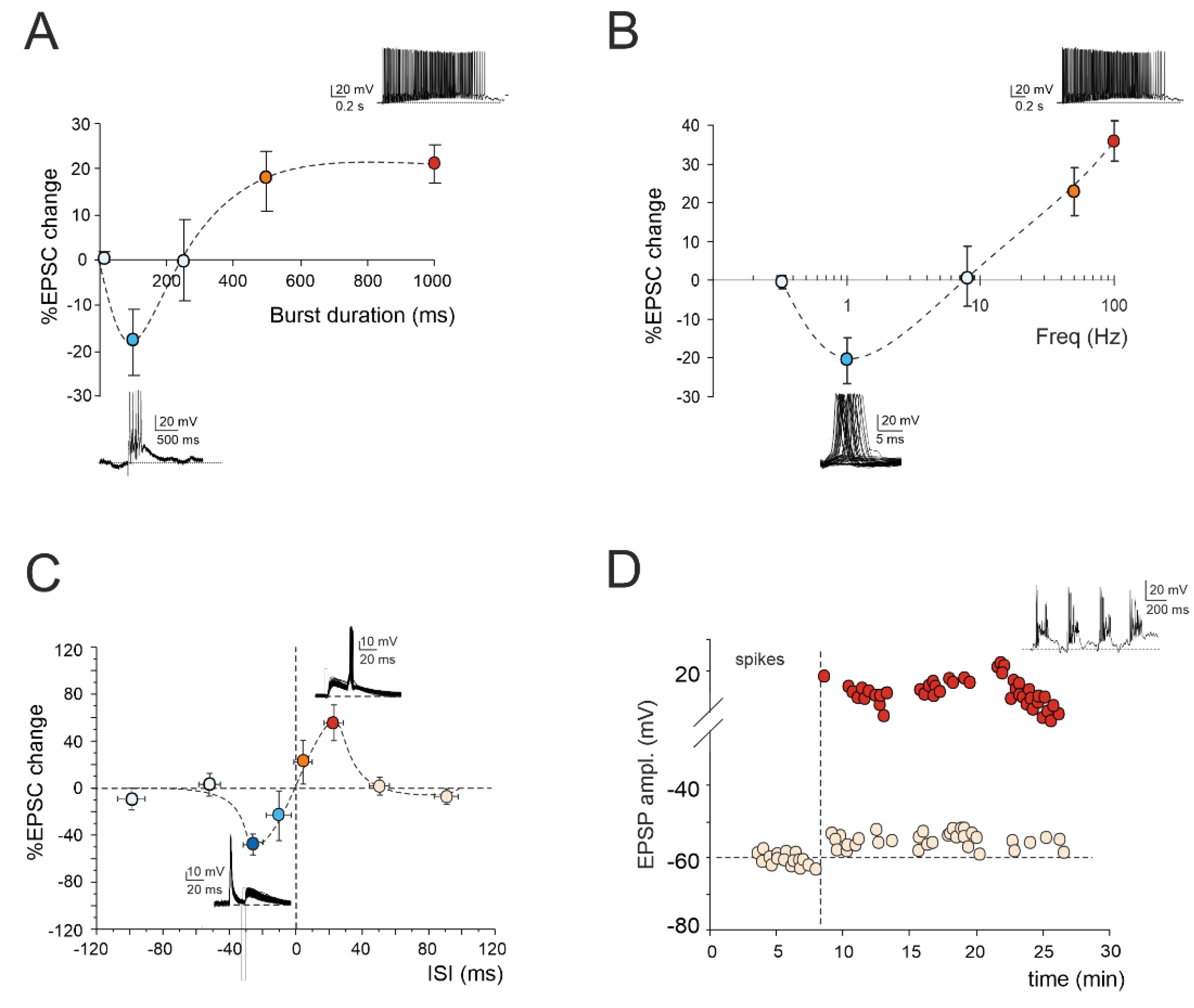

1.1. LTP/LTD Balance at Mossy Fiber-Granule Cell Synapse

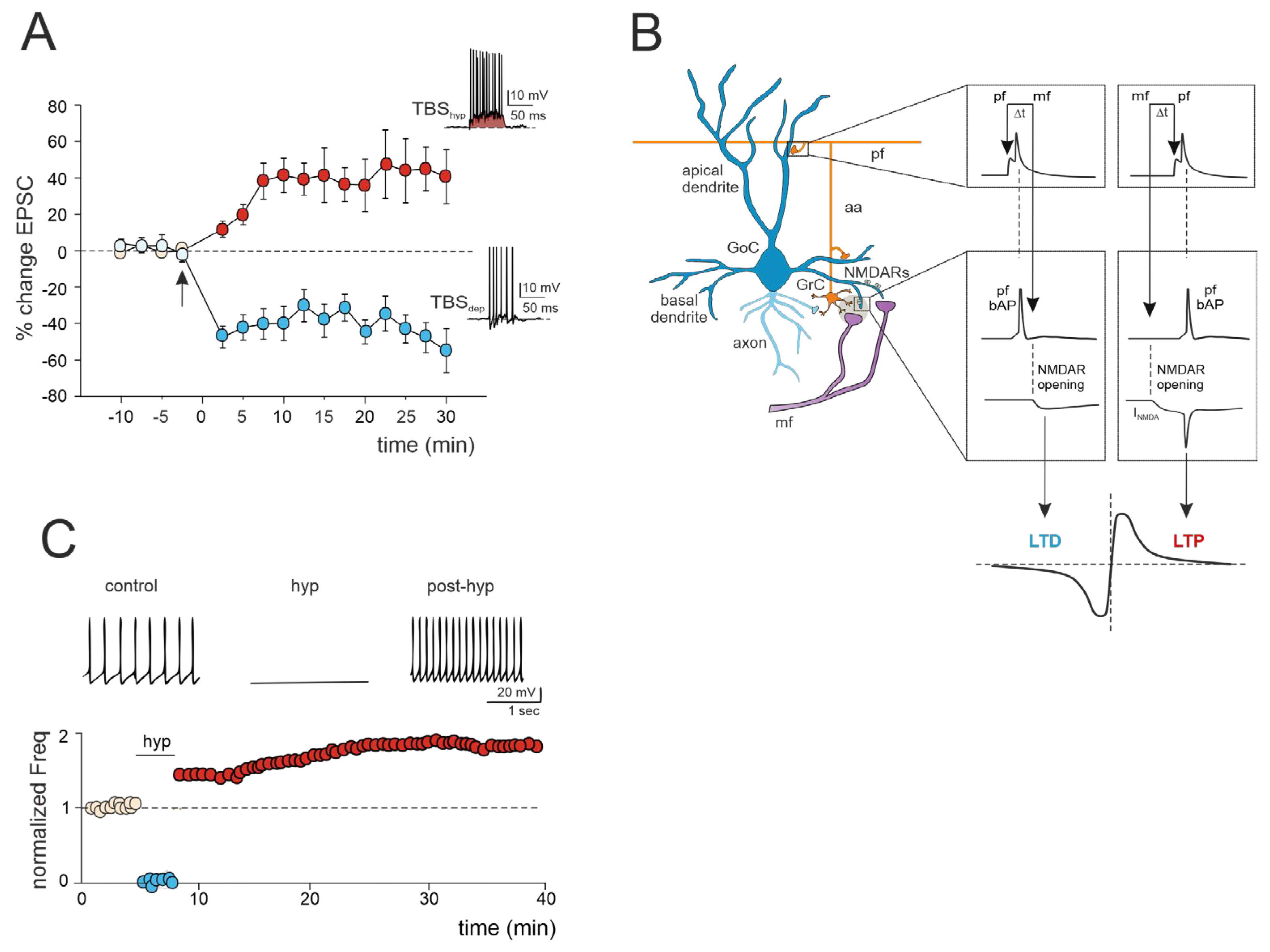

1.2. Spike-Timing Dependent Plasticity at Mossy Fiber-Granule Cell Synapse

1.3. Granule Cell Intrinsic Plasticity

2. Plasticity in Golgi Cells

2.1. LTP/LTD Balance at the Mossy Fiber-Golgi Cell Synapse

2.2. Golgi Cell Intrinsic Plasticity

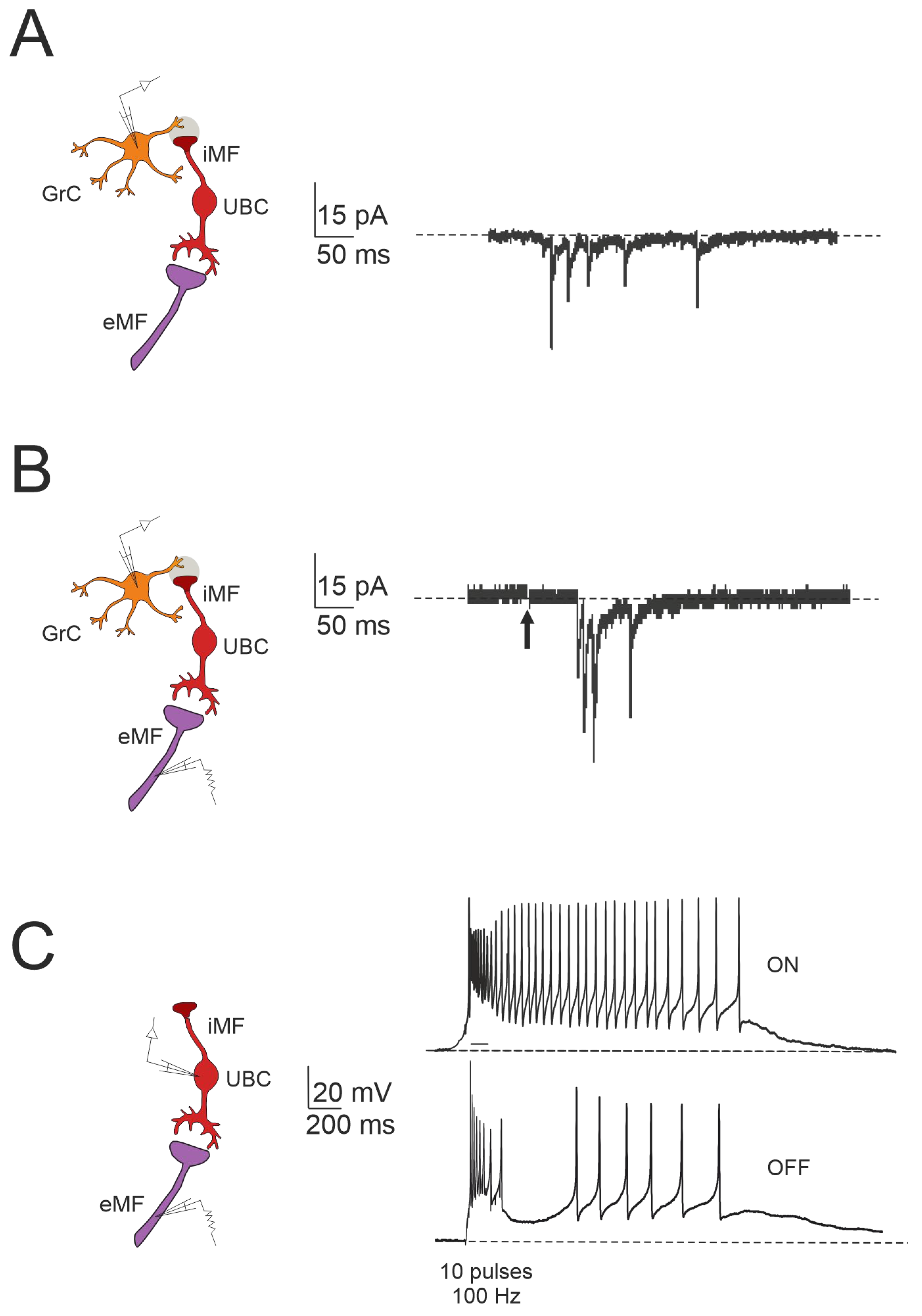

3. Plasticity in Unipolar Brush Cells

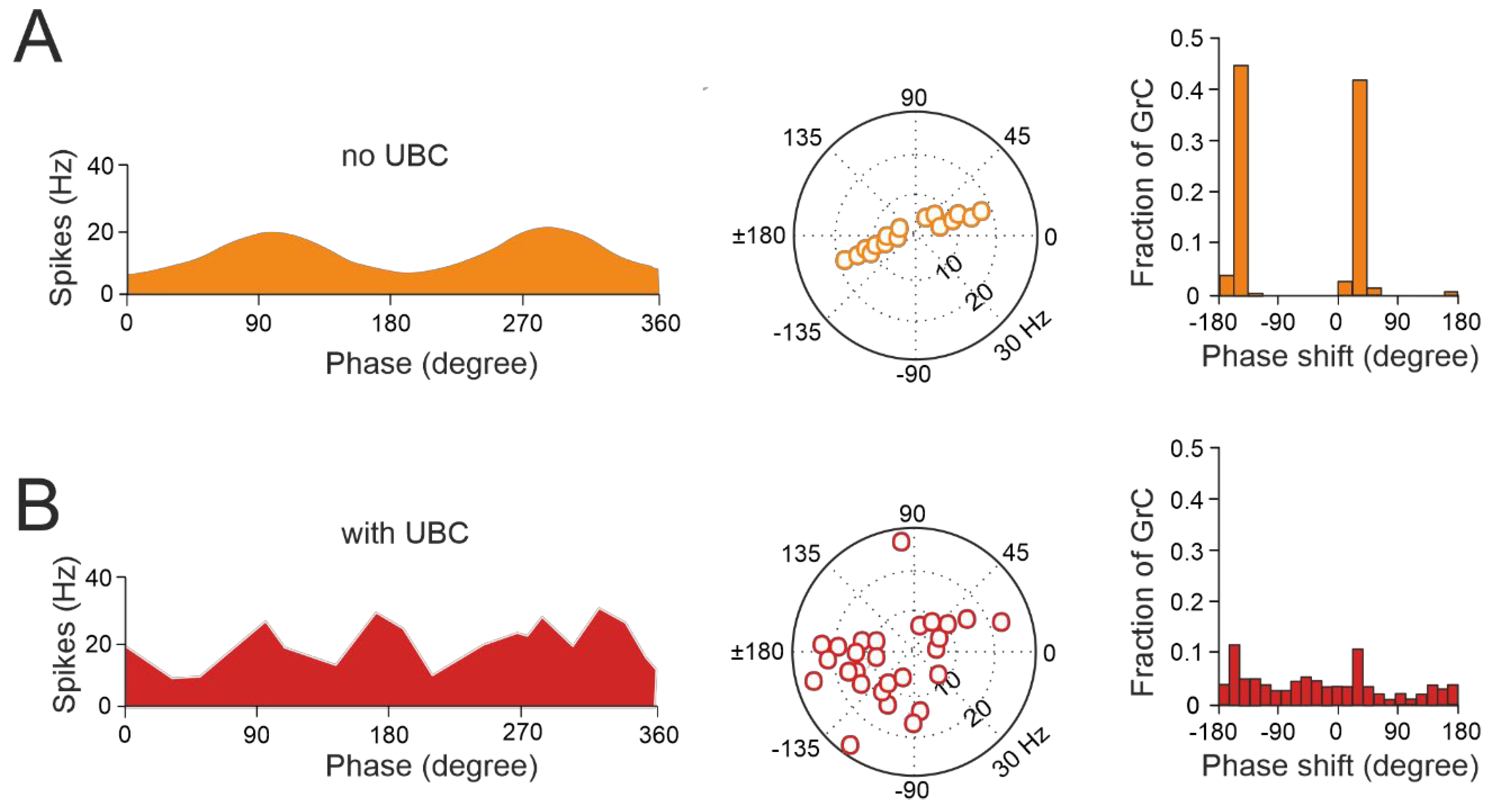

3.1. The Impact of UBC on Temporal Dynamics in the Granular Layer Network

4. Granular Layer Plasticity: Insights from Computational Models

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, S.J.; Grimwood, P.D.; Morris, R.G.M. Synaptic Plasticity and Memory: An Evaluation of the Hypothesis. Annu Rev Neurosci 2000, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweatt, J.D. Neural Plasticity and Behavior – Sixty Years of Conceptual Advances. J Neurochem 2016, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marr, D. A Theory of Cerebellar Cortex. J Physiol 1969, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albus, J.S. A Theory of Cerebellar Function. Math Biosci 1971, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloedel, J.R. Cerebellar Afferent Systems: A Review. Prog Neurobiol 1973, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voogd, J.; Glickstein, M. The Anatomy of the Cerebellum. Trends Neurosci 1998, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hámori, J.; Somogyi, J. Differentiation of Cerebellar Mossy Fiber Synapses in the Rat: A Quantitative Electron Microscope Study. Journal of Comparative Neurology 1983, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakab, R.L.; Hámori, J. Quantitative Morphology and Synaptology of Cerebellar Glomeruli in the Rat. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1988, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli, L.; Solinas, S.; D’Angelo, E. Integration and Regulation of Glomerular Inhibition in the Cerebellar Granular Layer Circuit. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Armano, S.; Rossi, P.; Taglietti, V.; D’angelo, E. 2000.

- D’Angelo, E.; Rossi, P.; Armano, S.; Taglietti, V. Evidence for NMDA and MGLU Receptor-Dependent Long-Term Potentiation of Mossy Fiber-Granule Cell Transmission in Rat Cerebellum. J Neurophysiol 1999, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, C.; Linden, D.J.; D’Angelo, E. Beyond Parallel Fiber LTD: The Diversity of Synaptic and Non-Synaptic Plasticity in the Cerebellum. Nat Neurosci 2001, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffei, A.; Prestori, F.; Rossi, P.; Taglietti, V.; D’Angelo, E. Presynaptic Current Changes at the Mossy Fiber-Granule Cell Synapse of Cerebellum during LTP. J Neurophysiol 2002, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, I.I.; Kaftan, E.J.; Ehrlich, B.E.; Watras, J. Regulation of Type 1 Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate-Gated Calcium Channels by InsP3 and Calcium: Simulation of Single Channel Kinetics Based on Ligand Binding and Electrophysiological Analysis. Journal of General Physiology 1999, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaftan, E.J.; Ehrlich, B.E.; Watras, J. Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate (InsP3) and Calcium Interact to Increase the Dynamic Range of InsP3 Receptor-Dependent Calcium Signaling. Journal of General Physiology 1997, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, H.R.; Gehring, C.A.; Parish, R.W. Changes in Cytosolic PH and Calcium of Guard Cells Precede Stomatal Movements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, P.B.; Nahorski, S.R.; Challiss, R.A.J. Agonist-Evoked Ca2+ Mobilization from Stores Expressing Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptors and Ryanodine Receptors in Cerebellar Granule Neurones. J Neurochem 1996, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, E.; Mclaughlin, M.; Downes, C.P.; Nicholls, D.G. Differential Coupling of G-Protein-Linked Receptors to Ca2+ Mobilization through Inositol(1,4,5)Trisphosphate or Ryanodine Receptors in Cerebellar Granule Cells in Primary Culture. European Journal of Neuroscience 1999, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliss, T.V.P.; Collingridge, G.L.; Morris, R.G.M. Synaptic Plasticity in Health and Disease: Introduction and Overview. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2014, 369. [CrossRef]

- Kullmann, D.M.; Erdemli, G.; Asztély, F. LTP of AMPA and NMDA Receptor-Mediated Signals: Evidence for Presynaptic Expression and Extrasynaptic Glutamate Spill-Over. Neuron 1996, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, J. Long-Term Potentiation: Outstanding Questions and Attempted Synthesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2003, 358.

- Sola, E.; Prestori, F.; Rossi, P.; Taglietti, V.; D’Angelo, E. Increased Neurotransmitter Release during Long-Term Potentiation at Mossy Fibre-Granule Cell Synapses in Rat Cerebellum. Journal of Physiology 2004, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieus, T.; Sola, E.; Mapelli, J.; Saftenku, E.; Rossi, P.; D’Angelo, E. LTP Regulates Burst Initiation and Frequency at Mossy Fiber-Granule Cell Synapses of Rat Cerebellum: Experimental Observations and Theoretical Predictions. J Neurophysiol 2006, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebb, D.O. The First Stage of Perception: Growth of the Assembly. The Organization of Behavior 1949. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bienenstock, E.L.; Cooper, L.N.; Munro, P.W. Theory for the Development of Neuron Selectivity: Orientation Specificity and Binocular Interaction in Visual Cortex. Journal of Neuroscience 1982, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisman, J. A Mechanism for the Hebb and the Anti-Hebb Processes Underlying Learning and Memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, P.K.; Chattarji, S.; Sejnowski, T.J. 2-Amino-3-Phosphonopropionic Acid, an Inhibitor of Glutamate-Stimulated Phosphoinositide Turnover, Blocks Induction of Homosynaptic Long-Term Depression, but Not Potentiation, in Rat Hippocampus. Neurosci Lett 1991, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Errico, A.; Prestori, F.; D’Angelo, E. Differential Induction of Bidirectional Long-Term Changes in Neurotransmitter Release by Frequency-Coded Patterns at the Cerebellar Input. Journal of Physiology 2009, 587, 5843–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diwakar, S.; Lombardo, P.; Solinas, S.; Naldi, G.; D’Angelo, E. Local Field Potential Modeling Predicts Dense Activation in Cerebellar Granule Cells Clusters under LTP and LTD Control. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, D.; Prestori, F.; Sola, E.; D’Errico, A.; Roussel, C.; Forti, L.; Rossi, P.; D’Angelo, E. Intracellular Calcium Regulation by Burst Discharge Determines Bidirectional Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity at the Cerebellum Input Stage. Journal of Neuroscience 2005, 25, 4813–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggeri, L.; Rivieccio, B.; Rossi, P.; D’Angelo, E. Tactile Stimulation Evokes Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity in the Granular Layer of Cerebellum. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 6354–6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffei, A.; Prestori, F.; Shibuki, K.; Rossi, P.; Taglietti, V.; D’Angelo, E. NO Enhances Presynaptic Currents during Cerebellar Mossy Fiber - Granule Cell LTP. J Neurophysiol 2003, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestori, F.; Bonardi, C.; Mapelli, L.; Lombardo, P.; Goselink, R.; De Stefano, M.E.; Gandolfi, D.; Mapelli, J.; Bertrand, D.; Schonewille, M.; et al. Gating of Long-Term Potentiation by Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors at the Cerebellum Input Stage. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fore, T.R.; Taylor, B.N.; Brunel, N.; Court Hull, X. Acetylcholine Modulates Cerebellar Granule Cell Spiking by Regulating the Balance of Synaptic Excitation and Inhibition. Journal of Neuroscience 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markram, H.; Lübke, J.; Frotscher, M.; Sakmann, B. Regulation of Synaptic Efficacy by Coincidence of Postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science (1979) 1997, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, G.Q.; Poo, M.M. Synaptic Modifications in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons: Dependence on Spike Timing, Synaptic Strength, and Postsynaptic Cell Type. Journal of Neuroscience 1998, 18, 10464–10472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debanne, D.; Inglebert, Y. Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity and Memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2023, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, D.E. The Spike-Timing Dependence of Plasticity. Neuron 2012, 75, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöström, P.J.; Turrigiano, G.G.; Nelson, S.B. Rate, Timing, and Cooperativity Jointly Determine Cortical Synaptic Plasticity. Neuron 2001, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markram, H.; Gerstner, W.; Sjöström, P.J. Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity: A Comprehensive Overview. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2012. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markram, H.; Gerstner, W.; Sjöström, P.J. A History of Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.Q.; Wang, H.X. Temporal Asymmetry in Spike Timing-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity. Physiol Behav 2002, 77, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, N.; Neuroscience, Y.D.-A.R. of; 2008, undefined Spike Timing–Dependent Plasticity: A Hebbian Learning Rule. iasbs.ac.ir 2008, 31, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepecs, A.; Van Rossum, M.C.W.; Song, S.; Tegner, J. Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity: Common Themes and Divergent Vistas. Biol Cybern 2002, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgritta, M.; Locatelli, F.; Soda, T.; Prestori, F.; D’Angelo, E.U. Hebbian Spike-Timing Dependent Plasticity at the Cerebellar Input Stage. Journal of Neuroscience 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, E.; Koekkoek, S.K.E.; Lombardo, P.; Solinas, S.; Ros, E.; Garrido, J.; Schonewille, M.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Timing in the Cerebellum: Oscillations and Resonance in the Granular Layer. Neuroscience 2009, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zeeuw, C.I.; Hoebeek, F.E.; Schonewille, M. Causes and Consequences of Oscillations in the Cerebellar Cortex. Neuron 2008, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerin, J.P.; Lamarre, Y. Local Field Potential Oscillations in Primate Cerebellar Cortex during Voluntary Movement. J Neurophysiol 1997, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.L. Timing Tasks Synchronize Cerebellar and Frontal Ramping Activity and Theta Oscillations: Implications for Cerebellar Stimulation in Diseases of Impaired Cognition. Front Psychiatry 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtemanche, R.; Robinson, J.C.; Aponte, D.I. Linking Oscillations in Cerebellar Circuits. Front Neural Circuits 2013. [CrossRef]

- Cheron, G.; Márquez-Ruiz, J.; Dan, B. Oscillations, Timing, Plasticity, and Learning in the Cerebellum. Cerebellum 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudal, G.; Debanne, D. Long-Term Plasticity of Intrinsic Excitability: Learning Rules and Mechanisms. Learning and Memory 2003, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debanne, D.; Inglebert, Y.; Russier, M. Plasticity of Intrinsic Neuronal Excitability. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2019, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.A.; Traynelis, S.F.; Cull-Candy, S.G. Rapid-Time-Course Miniature and Evoked Excitatory Currents at Cerebellar Synapses in Situ. Nature 1992, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, E.; Rossi, P.; Taglietti, V. Different Proportions of N-Methyl-d-Aspartate and Non-N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Currents at the Mossy Fibre-Granule Cell Synapse of Developing Rat Cerebellum. Neuroscience 1993, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent, P.B.; Saviane, C.; Nielsen, T.A.; DiGregorio, D.A.; Silver, R.A. Rapid Vesicular Release, Quantal Variability, and Spillover Contribute to the Precision and Reliability of Transmission at a Glomerular Synapse. Journal of Neuroscience 2005, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapelli, J.; Gandolfi, D.; Vilella, A.; Zoli, M.; Bigiani, A. Heterosynaptic GABAergic Plasticity Bidirectionally Driven by the Activity of Pre- and Postsynaptic NMDA Receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, E.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Timing and Plasticity in the Cerebellum: Focus on the Granular Layer. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, F.; Soda, T.; Montagna, I.; Tritto, S.; Botta, L.; Prestori, F.; D’Angelo, E. Calcium Channel-Dependent Induction of Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity at Excitatory Golgi Cell Synapses of Cerebellum. Journal of Neuroscience 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoli, S.; Ottaviani, A.; Casali, S.; D’Angelo, E. Cerebellar Golgi Cell Models Predict Dendritic Processing and Mechanisms of Synaptic Plasticity. PLoS Comput Biol 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, J.A.; Ros, E.; D’Angelo, E. Spike Timing Regulation on the Millisecond Scale by Distributed Synaptic Plasticity at the Cerebellum Input Stage: A Simulation Study. Front Comput Neurosci 2013. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, C.A.; Chu, Y.X.; Thanawala, M.; Regehr, W.G. Hyperpolarization Induces a Long-Term Increase in the Spontaneous Firing Rate of Cerebellar Golgi Cells. Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33, 5895–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.; Regehr, W.G. Identification of an Inhibitory Circuit That Regulates Cerebellar Golgi Cell Activity. Neuron 2012, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervaeke, K.; LÖrincz, A.; Gleeson, P.; Farinella, M.; Nusser, Z.; Silver, R.A. Rapid Desynchronization of an Electrically Coupled Interneuron Network with Sparse Excitatory Synaptic Input. Neuron 2010, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervaeke, K.; Lorincz, A.; Nusser, Z.; Silver, R.A. Gap Junctions Compensate for Sublinear Dendritic Integration in an Inhibitory Network. Science (1979) 2012, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugué, G.P.; Brunel, N.; Hakim, V.; Schwartz, E.; Chat, M.; Lévesque, M.; Courtemanche, R.; Léna, C.; Dieudonné, S. Electrical Coupling Mediates Tunable Low-Frequency Oscillations and Resonance in the Cerebellar Golgi Cell Network. Neuron 2009, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcamí, P.; Pereda, A.E. Beyond Plasticity: The Dynamic Impact of Electrical Synapses on Neural Circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hormuzdi, S.G.; Filippov, M.A.; Mitropoulou, G.; Monyer, H.; Bruzzone, R. Electrical Synapses: A Dynamic Signaling System That Shapes the Activity of Neuronal Networks. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2004, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulon, P.; Landisman, C.E. The Potential Role of Gap Junctional Plasticity in the Regulation of State. Neuron 2017, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernelle, G.; Nicola, W.; Clopath, C. Gap Junction Plasticity as a Mechanism to Regulate Network-Wide Oscillations. PLoS Comput Biol 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereda, A.E.; Curti, S.; Hoge, G.; Cachope, R.; Flores, C.E.; Rash, J.E. Gap Junction-Mediated Electrical Transmission: Regulatory Mechanisms and Plasticity. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2013, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.; Bloomfield, S.A. Plasticity of Retinal Gap Junctions: Roles in Synaptic P hysiology and Disease. Annu Rev Vis Sci 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, N.T.; Rossi, D.J.; Diño, M.R.; Jaarsm, D.; Mugnaini, E. Physiology and Ultrastructure of Unipolar Brush Cells in the Vestibulo-Cerebellum. In Neurochemistry of the Vestibular System; 2023.

- Nunzi, M.G.; Mugnaini, E. Unipolar Brush Cell Axons Form a Large System of Intrinsic Mossy Fibers in the Postnatal Vestibulocerebellum. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2000, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnaini, E.; Sekerková, G.; Martina, M. The Unipolar Brush Cell: A Remarkable Neuron Finally Receiving Deserved Attention. Brain Res Rev 2011, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunzi, M.G.; Birnstiel, S.; Bhattacharyya, B.J.; Slater, N.T.; Mugnaini, E. Unipolar Brush Cells Form a Glutamatergic Projection System within the Mouse Cerebellar Cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2001, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, D.J.; Alford, S.; Mugnaini, E.; Slater, N.T. Properties of Transmission at a Giant Glutamatergic Synapse in Cerebellum: The Mossy Fiber-Unipolar Brush Cell Synapse. J Neurophysiol 1995, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnaini, E.; Floris, A.; Wright-Goss, M. Extraordinary Synapses of the Unipolar Brush Cell: An Electron Microscopic Study in the Rat Cerebellum. Synapse 1994, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, G.A.; Overstreet, L.S.; Slater, N.T. Prolonged Physiological Entrapment of Glutamate in the Synaptic Cleft of Cerebellar Unipolar Brush Cells. J Neurophysiol 1997, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, N.T.; Rossi, D.J.; Kinney, G.A. Physiology of Transmission at a Giant Glutamatergic Synapse in Cerebellum. Prog Brain Res 1997, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dorp, S.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Forward Signaling by Unipolar Brush Cells in the Mouse Cerebellum. Cerebellum 2015, 14, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F.; Bottà, L.; Prestori, F.; Masetto, S.; D’Angelo, E. Late-Onset Bursts Evoked by Mossy Fibre Bundle Stimulation in Unipolar Brush Cells: Evidence for the Involvement of H- and TRP-Currents. Journal of Physiology 2013, 591, 899–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniyam, S.; Solinas, S.; Perin, P.; Locatelli, F.; Masetto, S.; D’Angelo, E. Computational Modeling Predicts the Ionic Mechanism of Late-Onset Responses in Unipolar Brush Cells. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diño, M.R.; Schuerger, R.J.; Liu, Y.B.; Slater, N.T.; Mugnaini, E. Unipolar Brush Cell: A Potential Feedforward Excitatory Interneuron of the Cerebellum. Neuroscience 2000, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitoma, H.; Manto, M.; Hampe, C.S. Time Is Cerebellum. Cerebellum 2018, 17, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bareš, M.; Apps, R.; Avanzino, L.; Breska, A.; D’Angelo, E.; Filip, P.; Gerwig, M.; Ivry, R.B.; Lawrenson, C.L.; Louis, E.D.; et al. Consensus Paper: Decoding the Contributions of the Cerebellum as a Time Machine. From Neurons to Clinical Applications. Cerebellum 2019, 18, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivry, R.B.; Spencer, R.M.; Zelaznik, H.N.; Diedrichsen, J. The Cerebellum and Event Timing. In Proceedings of the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; 2002; Vol. 978. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, E.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Timing and Plasticity in the Cerebellum: Focus on the Granular Layer. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zeeuw, C.I.; Hoebeek, F.E.; Bosman, L.W.J.; Schonewille, M.; Witter, L.; Koekkoek, S.K. Spatiotemporal Firing Patterns in the Cerebellum. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011, 12, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariani, H.N.; Algstam, A.B.; Candler, C.T.; Witteveen, I.F.; Sidhu, J.K.; Balmer, T.S. A System of Feed-Forward Cerebellar Circuits That Extend and Diversify Sensory Signaling. Elife 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampini, V.; Liu, J.K.; Diana, M.A.; Maldonado, P.P.; Brunel, N.; Phane Dieudonné, S. Mechanisms and Functional Roles of Glutamatergic Synapse Diversity in a Cerebellar Circuit. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Van Dorp, S.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Variable Timing of Synaptic Transmission in Cerebellar Unipolar Brush Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 5403–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Merjane, C.; Trussell, L.O. ON and OFF Unipolar Brush Cells Transform Multisensory Inputs to the Auditory System. Neuron 2015, 85, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, T.S.; Trussell, L.O. Selective Targeting of Unipolar Brush Cell Subtypes by Cerebellar Mossy Fibers. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Huson, V.; Macosko, E.Z.; Regehr, W.G. Graded Heterogeneity of Metabotropic Signaling Underlies a Continuum of Cell-Intrinsic Temporal Responses in Unipolar Brush Cells. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.; Wayne, G.; Kaifosh, P.; Alviña, K.; Abbott, L.F.; Sawtell, N.B. A Temporal Basis for Predicting the Sensory Consequences of Motor Commands in an Electric Fish. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Huson, V.; Macosko, E.Z.; Regehr, W.G. Graded Heterogeneity of Metabotropic Signaling Underlies a Continuum of Cell-Intrinsic Temporal Responses in Unipolar Brush Cells. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M. Adaptive Filter Model of the Cerebellum. Biol Cybern 1982, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, P.; Porrill, J.; Ekerot, C.; Neuroscience, H.J.-N.R. ; 2010, undefined The Cerebellar Microcircuit as an Adaptive Filter: Experimental and Computational Evidence. nature.comP Dean, J Porrill, CF Ekerot, H JörntellNature Reviews Neuroscience, 2010•nature.com 2009, 11. [CrossRef]

- Dean, P.; Porrill, J. Evaluating the Adaptive-Filter Model of the Cerebellum. Journal of Physiology 2011, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.F.; Garcia, K.S.; Nores, W.L.; Taylor, N.M.; Mauk, M.D. Timing Mechanisms in the Cerebellum: Testing Predictions of a Large- Scale Computer Simulation. Journal of Neuroscience 2000, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Van Beugen, B.J.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Distributed Synergistic Plasticity and Cerebellar Learning. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.D.; Bell, C.C. Computational Consequences of Temporally Asymmetric Learning Rules: II. Sensory Image Cancellation. J Comput Neurosci 2000, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barmack, N.H.; Yakhnitsa, V. Functions of Interneurons in Mouse Cerebellum. Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Víg, J.; Takács, J.; Ábrahám, H.; Kovács, G.G.; Hámori, J. Calretinin-Immunoreactive Unipolar Brush Cells in the Developing Human Cerebellum. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 2005, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, J.; Borostyánkõi, Z.A.; Veisenberger, E.; Vastagh, C.; Víg, J.; Görcs, T.J.; Hámori, J. Postnatal Development of Unipolar Brush Cells in the Cerebellar Cortex of Cat. J Neurosci Res 2000, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diño, M.R.; Willard, F.H.; Mugnaini, E. Distribution of Unipolar Brush Cells and Other Calretinin Immunoreactive Components in the Mammalian Cerebellar Cortex. J Neurocytol 1999, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestori, F.; Mapelli, L.; D’Angelo, E. Diverse Neuron Properties and Complex Network Dynamics in the Cerebellar Cortical Inhibitory Circuit. Front Mol Neurosci 2019, 12, 492015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli, J.; Gandolfi, D.; D’Angelo, E. High-Pass Filtering and Dynamic Gain Regulation Enhance Vertical Bursts Transmission along the Mossy Fiber Pathway of Cerebellum. Front Cell Neurosci 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, E.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Timing and Plasticity in the Cerebellum: Focus on the Granular Layer. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweighofer, N.; Doya, K.; Lay, F. Unsupervised Learning of Granule Cell Sparse Codes Enhances Cerebellar Adaptive Control. Neuroscience 2001, 103, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solinas, S.; Nieus, T.; D’Angelo, E. A Realistic Large-Scale Model of the Cerebellum Granular Layer Predicts Circuit Spatio-Temporal Filtering Properties. Front Cell Neurosci 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casali, S.; Tognolina, M.; Gandolfi, D.; Mapelli, J.; D’Angelo, E. Cellular-Resolution Mapping Uncovers Spatial Adaptive Filtering at the Rat Cerebellum Input Stage. Commun Biol 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, E.; Mapelli, L.; Casellato, C.; Garrido, J.A.; Luque, N.; Monaco, J.; Prestori, F.; Pedrocchi, A.; Ros, E. Distributed Circuit Plasticity: New Clues for the Cerebellar Mechanisms of Learning. Cerebellum 2016, 15, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Van Beugen, B.J.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Distributed Synergistic Plasticity and Cerebellar Learning. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012, 13, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rössert, C.; Dean, P.; Porrill, J. At the Edge of Chaos: How Cerebellar Granular Layer Network Dynamics Can Provide the Basis for Temporal Filters. PLoS Comput Biol 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, E.A.; Field, G.D.; Tadross, M.R.; Hull, C. Local Synaptic Inhibition Mediates Cerebellar Granule Cell Pattern Separation and Enables Learned Sensorimotor Associations. Nat Neurosci 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gilmer, J.I.; Person, A.L. Morphological Constraints on Cerebellar Granule Cell Combinatorial Diversity. Journal of Neuroscience 2017, 37, 12153–12166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proville, R.D.; Spolidoro, M.; Guyon, N.; Dugué, G.P.; Selimi, F.; Isope, P.; Popa, D.; Léna, C. Cerebellum Involvement in Cortical Sensorimotor Circuits for the Control of Voluntary Movements. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).