Submitted:

30 April 2024

Posted:

01 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

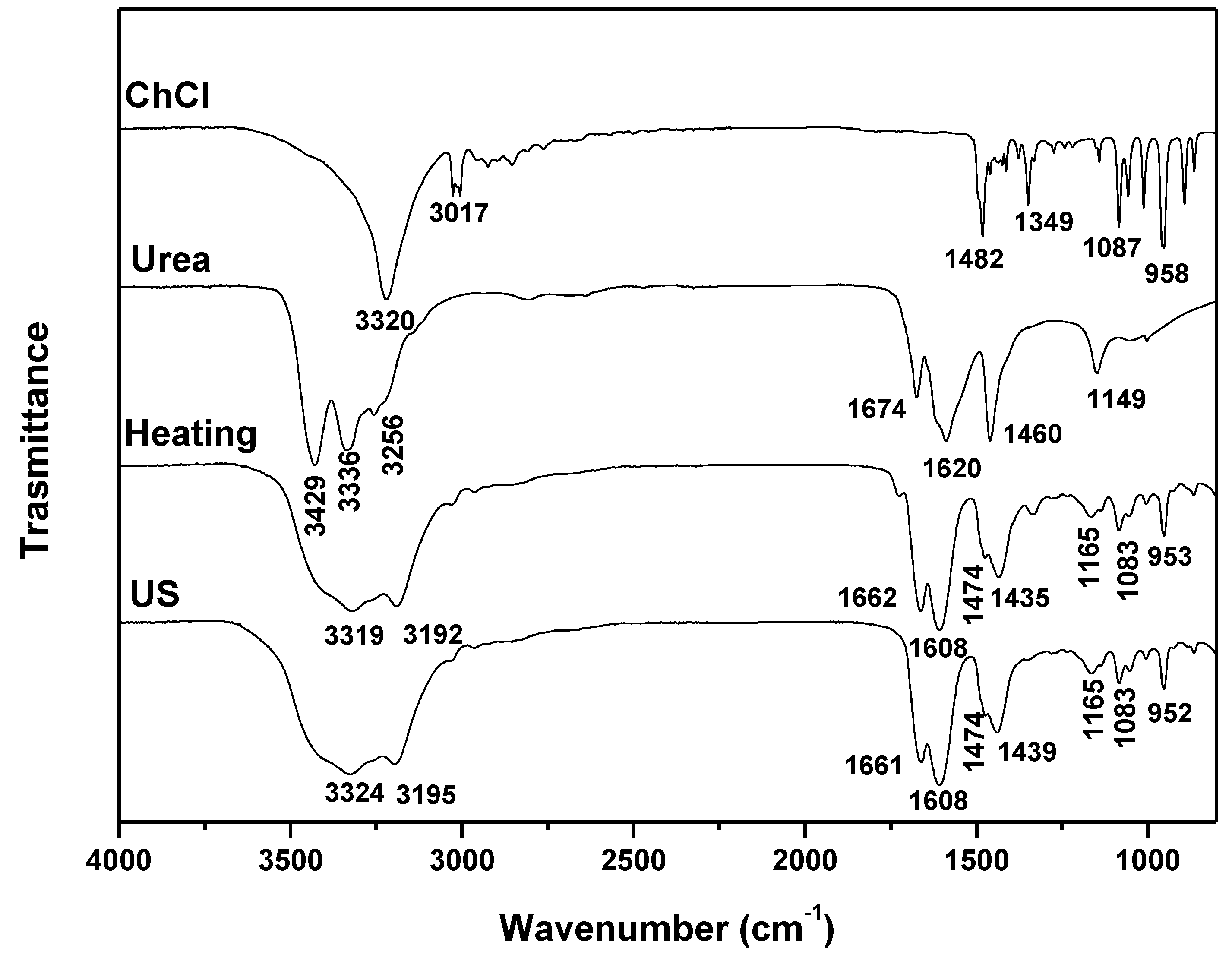

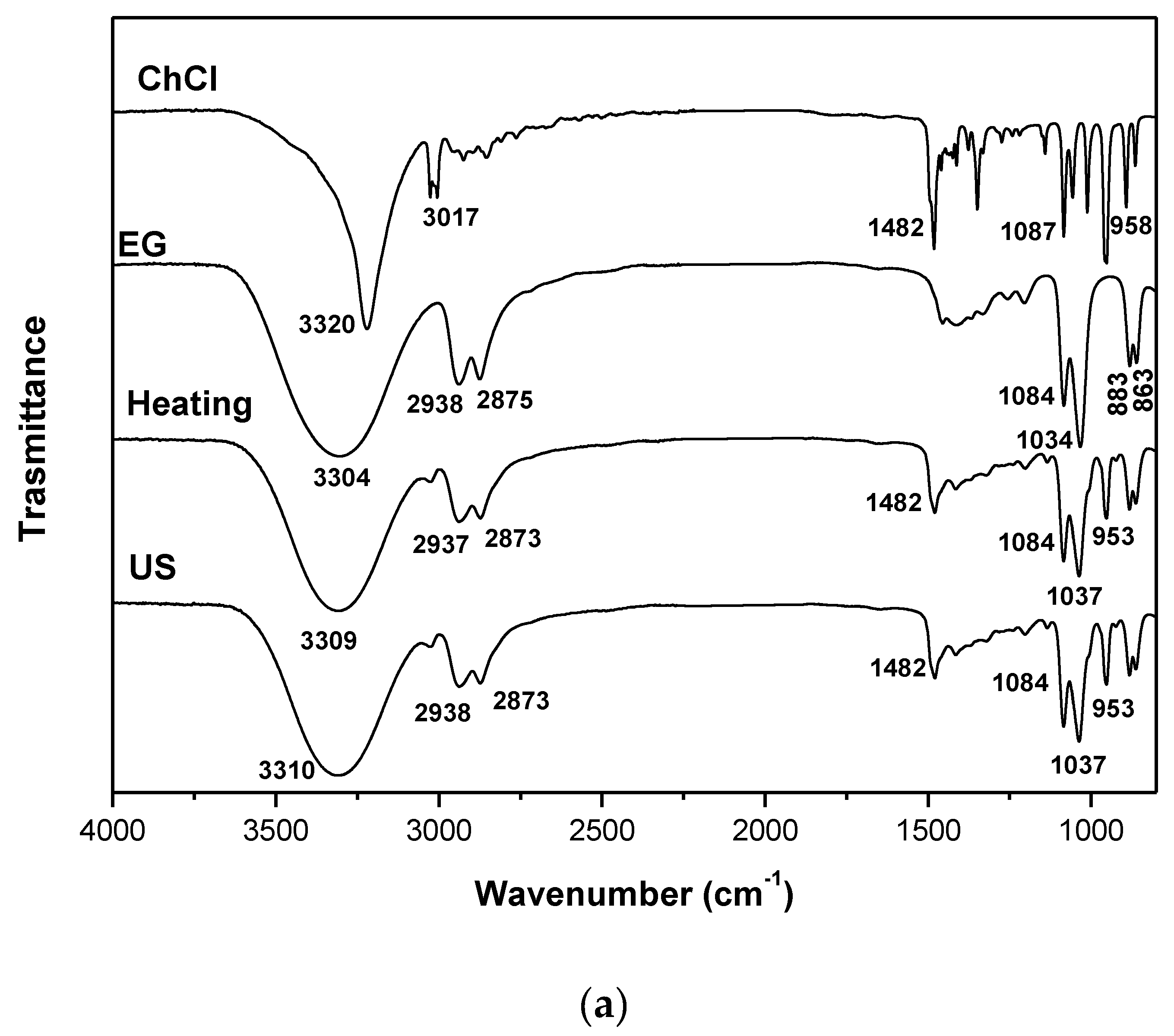

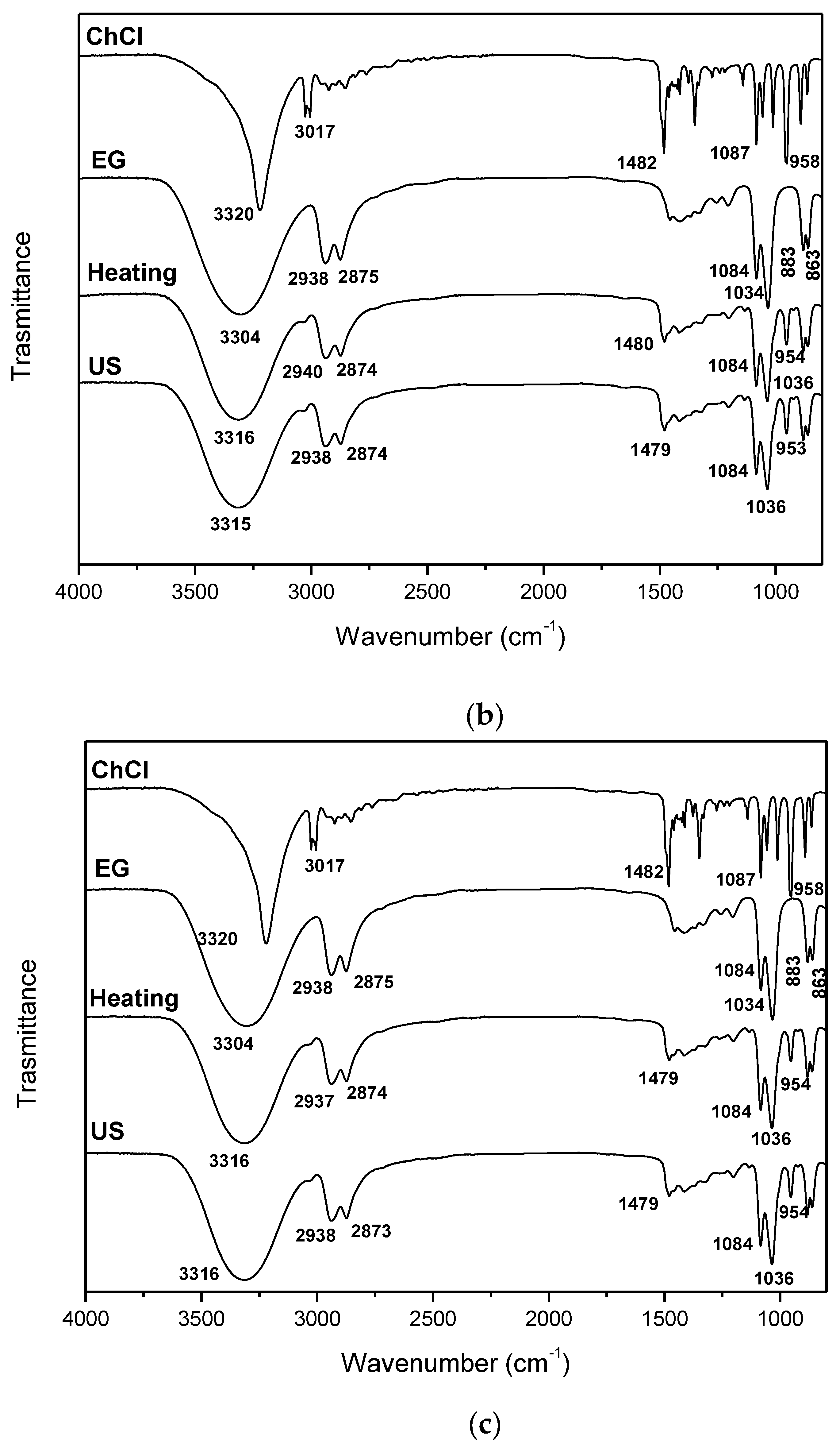

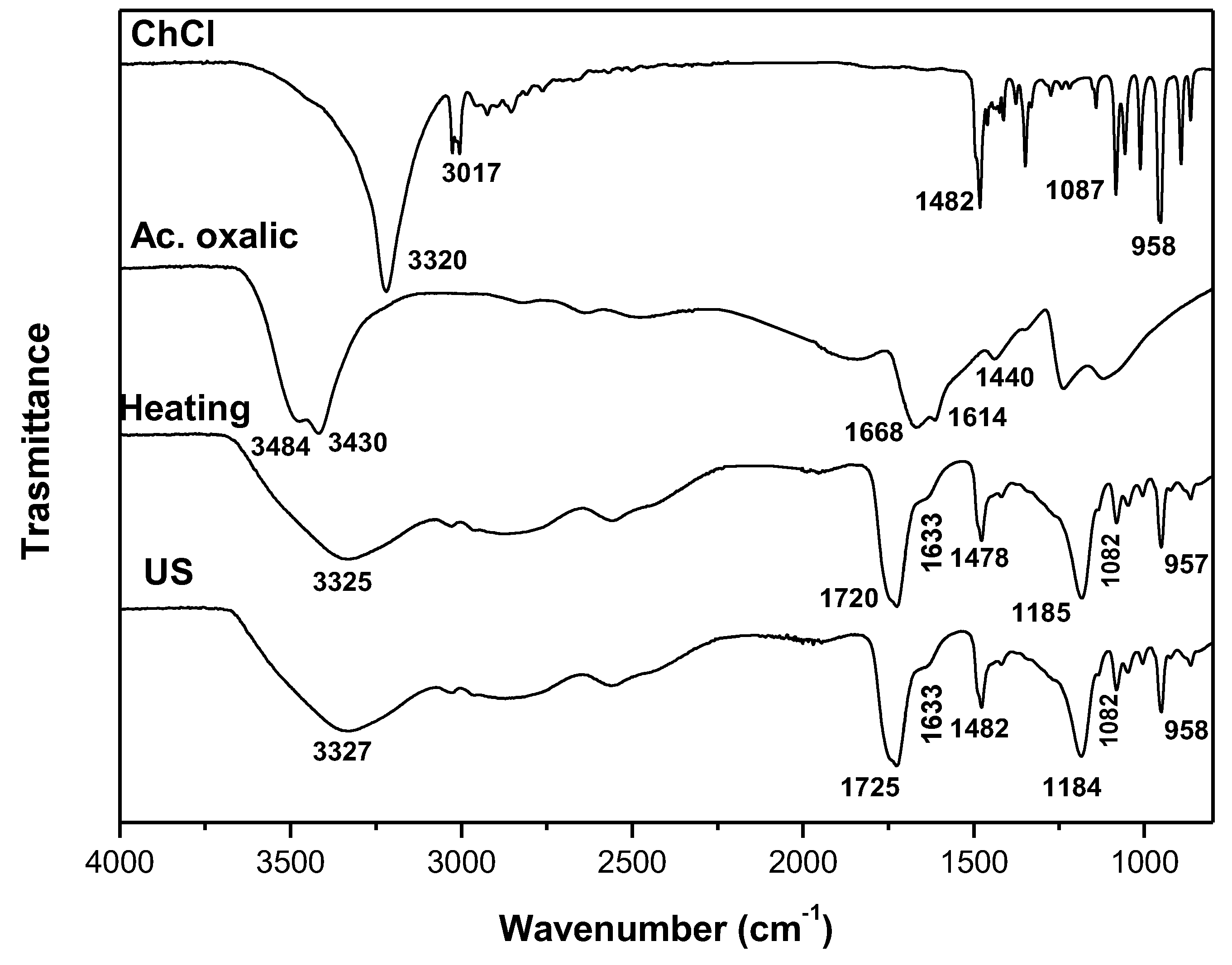

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Reagents

3.2. Synthesis Method

3.3. Physical-Chemical Characterization of the DESs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixturesElectronic supplementary information (ESI) available: spectroscopic data. See http://www.rsc.org/suppdata/cc/b2/b210714g/. Chem. Commun. 2003; 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.B.; Kumar, V.S.; Chaudhary, M.; Singh, P. A mini review on synthesis, properties and applications of deep eutectic solvents. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2021, 98, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, R.; Ilangeswaran, D. Synthesis of some metal nanoparticles using the effective media of choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 3366–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussagy, C.U.; Hucke, H.U.; Ramos, N.F.; Ribeiro, H.F.; Alves, M.B.; Mustafa, A.; Pereira, J.F.B.; Farias, F.O. Tailor-made solvents for microbial carotenoids recovery. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, C.M.A. Perspectives for the use of deep eutectic solvents in the preparation of electrochemical sensors and biosensors. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2024, 45, 101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Saeed, B.; AlMohamadi, H.; Lee, M.; Gilani, M.A.; Nawaz, R.; Khan, A.L.; Yasin, M. Sustainable and green membranes for chemical separations: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.I.; García-Díaz, I.; López, F.A. Properties and perspective of using deep eutectic solvents for hydrometallurgy metal recovery. Miner. Eng. 2023, 203, 108306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.B.; Spittle, S.; Chen, B.; Poe, D.; Zhang, Y.; Klein, J.M.; Horton, A.; Adhikari, L.; Zelovich, T.; Doherty, B.W.; et al. Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1232–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Davies, D.L.; Munro, H.L.; Rasheed, R.K.; Tambyrajah, V. Preparation of novel, moisture-stable, Lewis-acidic ionic liquids containing quaternary ammonium salts with functional side chains. Chem. Commun. 2001, 2010–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibuna, M.; Theresa, L.V.; Sreekumar, K. Neoteric deep eutectic solvents: history, recent developments, and catalytic applications. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 2695–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, C.; Oliveira, F.S.; Rebelo, L.P.N.; Fernandes, A.M.; Marrucho, I.M. Insights into the Synthesis and Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Cholinium Chloride and Carboxylic Acids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2416–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Rodriguez, N.; van den Bruinhorst, A.; Kollau, L.J.B.M.; Kroon, M.C.; Binnemans, K. Degradation of Deep-Eutectic Solvents Based on Choline Chloride and Carboxylic Acids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11521–11528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Flores, F.G.; Mingorance-Sánchez, C. Deep Eutectic Solvents and Multicomponent Reactions: Two Convergent Items to Green Chemistry Strategies. ChemistryOpen 2021, 10, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.Q.; Abbasi, N.M.; Anderson, J.L. Deep eutectic solvents in separations: Methods of preparation, polarity, and applications in extractions and capillary electrochromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1633, 461613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, D.E.; Wright, L.A.; James, S.L.; Abbott, A.P. Efficient continuous synthesis of high purity deep eutectic solvents by twin screw extrusion. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4215–4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, M.C.; Ferrer, M.L.; Yuste, L.; Rojo, F.; del Monte, F. Bacteria Incorporation in Deep-eutectic Solvents through Freeze-Drying. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 2158–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, M.W.; Zhao, J.; Lee, M.S.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, J. Enhanced extraction of bioactive natural products using tailor-made deep eutectic solvents: application to flavonoid extraction from Flos sophorae. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; van Spronsen, J.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural deep eutectic solvents as new potential media for green technology. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 766, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Tailoring properties of natural deep eutectic solvents with water to facilitate their applications. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, F.J. V.; Espino, M.; Fernández, M.A.; Silva, M.F. A Greener Approach to Prepare Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 6122–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, A.P.R.; Mora-Vargas, J.A.; Guimarães, T.G.S.; Amaral, C.D.B.; Oliveira, A.; Gonzalez, M.H. Sustainable synthesis of natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) by different methods. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 293, 111452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, O.; Banach, M. Green methods for obtaining deep eutectic solvents (DES). J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, H.J.; Vallance, S.R.; Kennedy, J.L.; Tapia-Ruiz, N.; Carassiti, L.; Harrison, A.; Whittaker, A.G.; Drysdale, T.D.; Kingman, S.W.; Gregory, D.H. Modern Microwave Methods in Solid-State Inorganic Materials Chemistry: From Fundamentals to Manufacturing. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1170–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banakar, V.V.; Sabnis, S.S.; Gogate, P.R.; Raha, A. Saurabh Ultrasound assisted continuous processing in microreactors with focus on crystallization and chemical synthesis: A critical review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 182, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Dey, S.; Chakraborty, R. Effect of choline chloride-oxalic acid based deep eutectic solvent on the ultrasonic assisted extraction of polyphenols from Aegle marmelos. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 287, 110956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Jia, Y.; Yao, Y.; Sun, J.; Jing, Y. Structure and electrochemical behavior of ionic liquid analogue based on choline chloride and urea. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 65, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Liao, C. Insights into the Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvent Based on Reline for Ga-Controllable CIGS Solar Cell in One-Step Electrodeposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, D689–D693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotroneo-Figueroa, V.P.; Gajardo-Parra, N.F.; López-Porfiri, P.; Leiva, Á.; Gonzalez-Miquel, M.; Garrido, J.M.; Canales, R.I. Hydrogen bond donor and alcohol chain length effect on the physicochemical properties of choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents mixed with alcohols. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 345, 116986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo-Parra, N.F.; Lubben, M.J.; Winnert, J.M.; Leiva, Á.; Brennecke, J.F.; Canales, R.I. Physicochemical properties of choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents and excess properties of their pseudo-binary mixtures with 1-butanol. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2019, 133, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullaikah, S.; Rachmaniah, O.; Utomo, A.T.; Niawanti, H.; Ju, Y.H. Green Separation of bioactive natural products using liquiefied mixture of solids; Green Chem.; 2018.

- Milevskii, N.A.; Zinov’eva, I.V.; Zakhodyaeva, Y.A.; Voshkin, A.A. Separation of Li(I), Co(II), Ni(II), Mn(II), and Fe(III) from hydrochloric acid solution using a menthol-based hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 207, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.; Schennach, R.; Gollas, B. In situ PM-IRRAS of a glassy carbon electrode/deep eutectic solvent interface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 12870–12880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, F.; Chiarini, M.; Germani, R.; Tiecco, M.; Spreti, N. Effect of water addition on choline chloride/glycol deep eutectic solvents: Characterization of their structural and physicochemical properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 291, 111301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendive, C.B.; Bredow, T.; Blesa, M.A.; Bahnemann, D.W. ATR-FTIR measurements and quantum chemical calculations concerning the adsorption and photoreaction of oxalic acid on TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, S.L.; Painter, P.; Colina, C.M. Experimental and Computational Studies of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2014, 59, 3652–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, F.A. Isolation and identification of antimicrobial compound from Mentha longifolia L. leaves grown wild in Iraq. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2009, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.K.; Rout, P.C.; Sarangi, K.; Nathsarma, K.C. Solvent extraction of Fe(III) from the chloride leach liquor of low grade iron ore tailings using Aliquat 336. Hydrometallurgy 2011, 108, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.Y.; Morad, N.; Ismail, N.; Talebi, A.; Rafatullah, M. Optimization for Liquid-Liquid Extraction of Cd(II) over Cu(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions Using Ionic Liquid Aliquat 336 with Tributyl Phosphate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, P.J.; Cosby, T.; Holt, A.P.; Benson, R.S.; Sangoro, J.R. Charge Transport and Structural Dynamics in Carboxylic-Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Mixtures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 9378–9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Poe, D.; Heroux, L.; Squire, H.; Doherty, B.W.; Long, Z.; Dadmun, M.; Gurkan, B.; Tuckerman, M.E.; Maginn, E.J. Liquid Structure and Transport Properties of the Deep Eutectic Solvent Ethaline. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 5251–5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.P.; Harris, R.C.; Ryder, K.S. Application of Hole Theory to Define Ionic Liquids by their Transport Properties. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 4910–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mero, A.; Koutsoumpos, S.; Giannios, P.; Stavrakas, I.; Moutzouris, K.; Mezzetta, A.; Guazzelli, L. Comparison of physicochemical and thermal properties of choline chloride and betaine-based deep eutectic solvents: The influence of hydrogen bond acceptor and hydrogen bond donor nature and their molar ratios. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 377, 121563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.H.; Sabri, M.A.; Abdel Jabbar, N.; Nancarrow, P.; Mjalli, F.S.; AlNashef, I. Thermal Conductivities of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Mixtures with Water: Measurement and Estimation. Molecules 2020, 25, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, A.P.; Capper, G.; Gray, S. Design of Improved Deep Eutectic Solvents Using Hole Theory. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Osch, D.J.G.P.; Dietz, C.H.J.T.; van Spronsen, J.; Kroon, M.C.; Gallucci, F.; van Sint Annaland, M.; Tuinier, R. A Search for Natural Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Natural Components. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 2933–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijardar, S.P.; Singh, V.; Gardas, R.L. Revisiting the Physicochemical Properties and Applications of Deep Eutectic Solvents. Molecules 2022, 27, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, M.C.; Ferrer, M.L.; Mateo, C.R.; del Monte, F. Freeze-Drying of Aqueous Solutions of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Suitable Approach to Deep Eutectic Suspensions of Self-Assembled Structures. Langmuir 2009, 25, 5509–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Tang, Q.F.; Zhu, Y.W.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.J. An alternative electrolyte of deep eutectic solvent by choline chloride and ethylene glycol for wide temperature range supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 2020, 452, 227847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

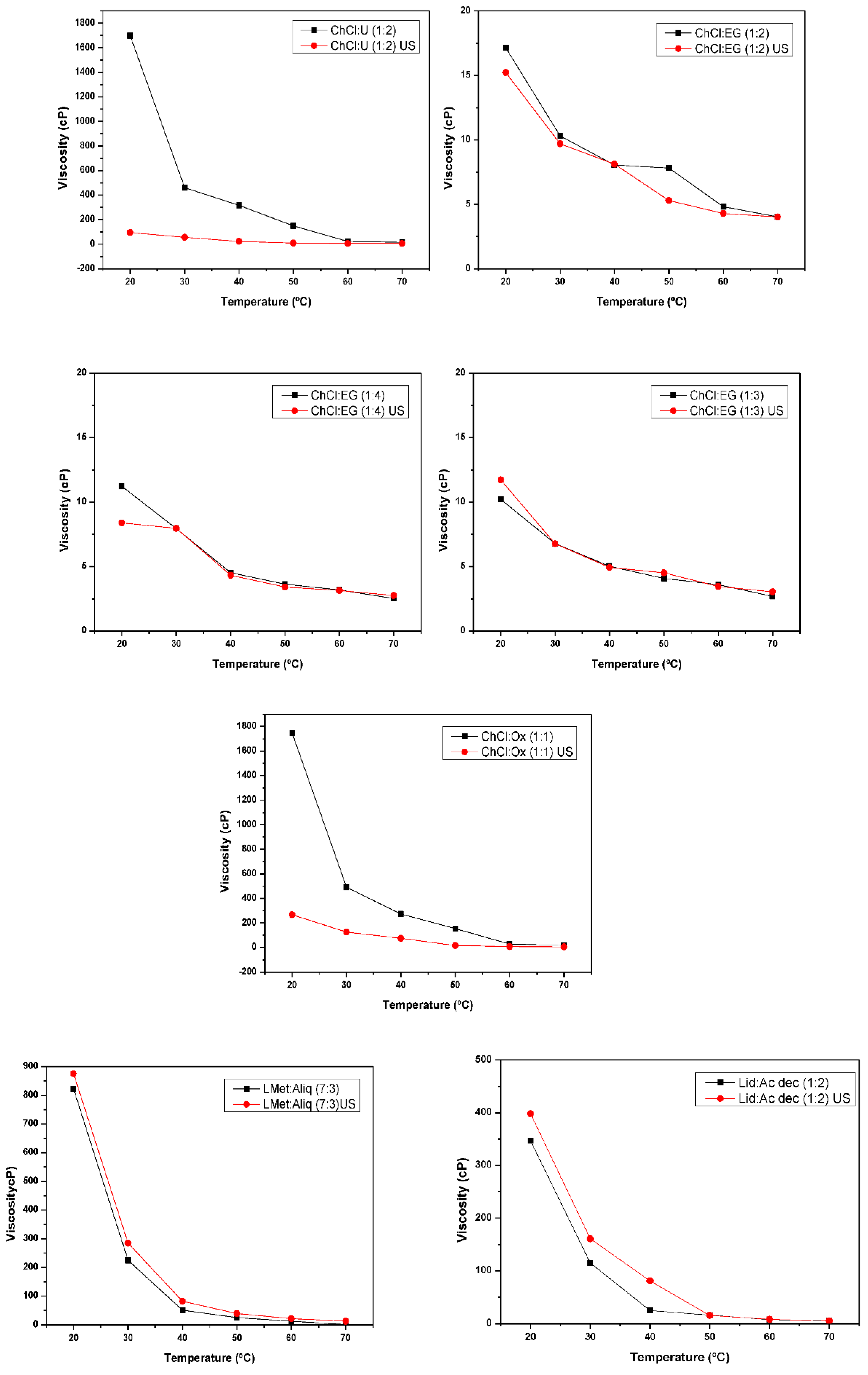

| DES | Heating-stirring | Ultrasound | ||

| Time (h) | Temperature (ºC) | Time (h) | Temperature (ºC) | |

| ChCl: U (1:2) | 5 | 80 | 4 | 50 |

| ChCl:EG (1:2) | 24 | 80 | 1 | 50 |

| ChCl:EG (1:3) | 24 | 80 | 1 | 45 |

| ChCl:EG (1:4) | 24 | 80 | 1 | 45 |

| ChCl:Ox (1:1) | 4.5 | 60 | 3 | 58 |

| Aliq:LMet (3:7) | 0.5 | 60 | 0.5 | 46 |

| Lid: Ac Dec (1:2) | 1 | 60 | 1 | 44 |

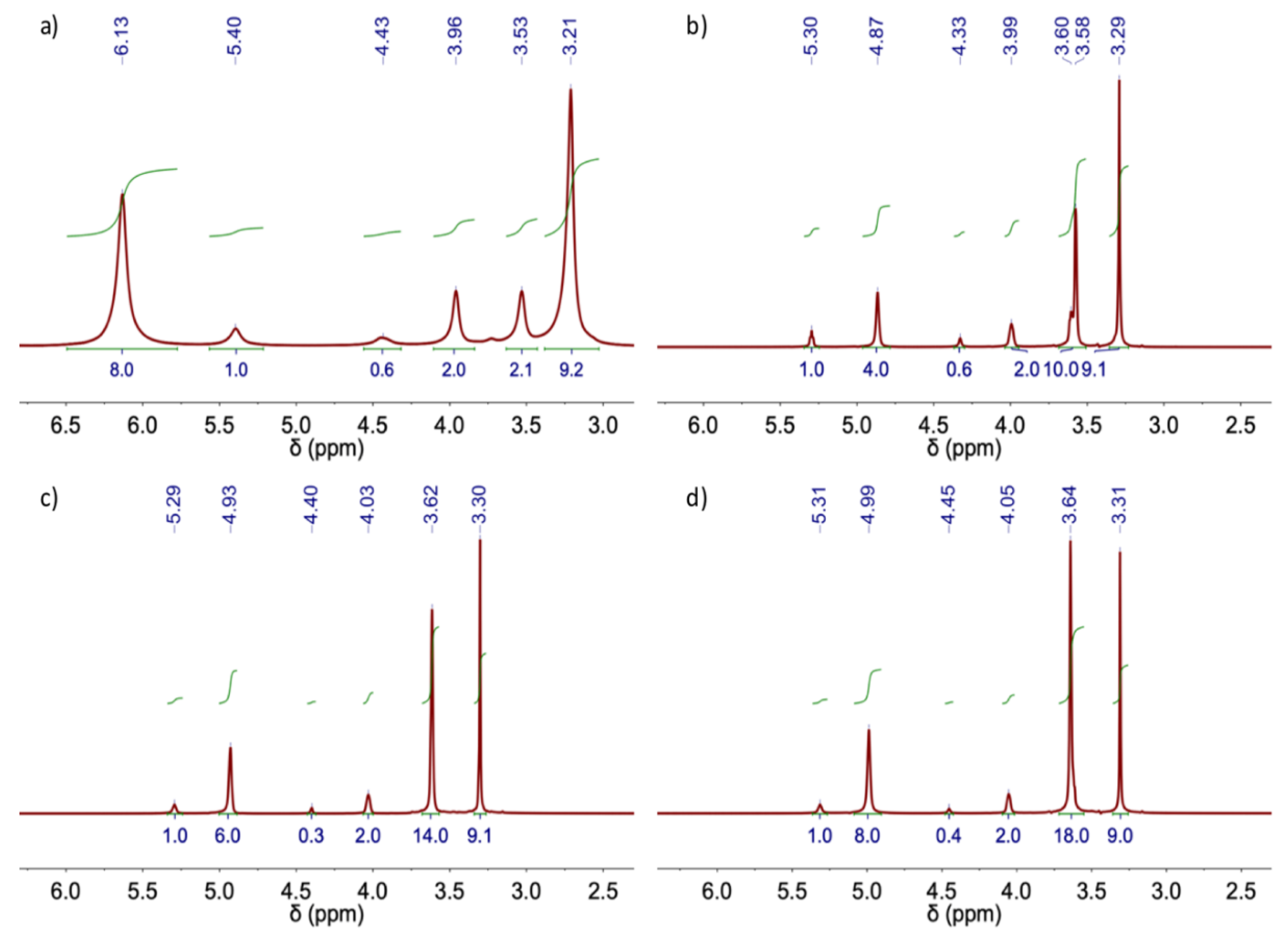

| δ (ppm) | ||||||||

| DES | EG | ChCl | H2O | |||||

| OH | O-CH2 | OH | O-CH2 | +N-CH2 | +N-(CH3)3 |

HO |

||

| ChCl:EG (1:2) | 4.87 (4H) |

3.60-3.58 (8H+2H) |

5.30 (1H) |

3.99 (2H) |

3.60-3.58 (2H+8H) |

3.29 (9H) |

4.33 (0.6H) |

|

| ChCl:EG (1:3) | 4.93 (6H) |

3.63 (12H+2H) |

5.29 (1H) |

4.03 (2H) |

3.62 (2H+12H) |

3.30 (9H) |

4.40 (0.3H) |

|

| ChCl:EG (1:4) | 4.99 (8H) |

3.64 (16H+2H) |

5.31 (1H) |

4.05 (2H) |

3.64 (2H+16H) |

3.31 (9H) |

4.45 (0.4H) |

|

| δ (ppm) | ||||||

| DES | U | ChCl | H2O | |||

| C-NH2 | OH | O-CH2 | +N-CH2 | +N-(CH3)3 | HO | |

| ChCl: U (1:2) | 6.13 (8H) |

5.40 (1H) |

3.96 (2H) |

3.53 (2H) |

3.21 (9H) |

4.43 (0.6H) |

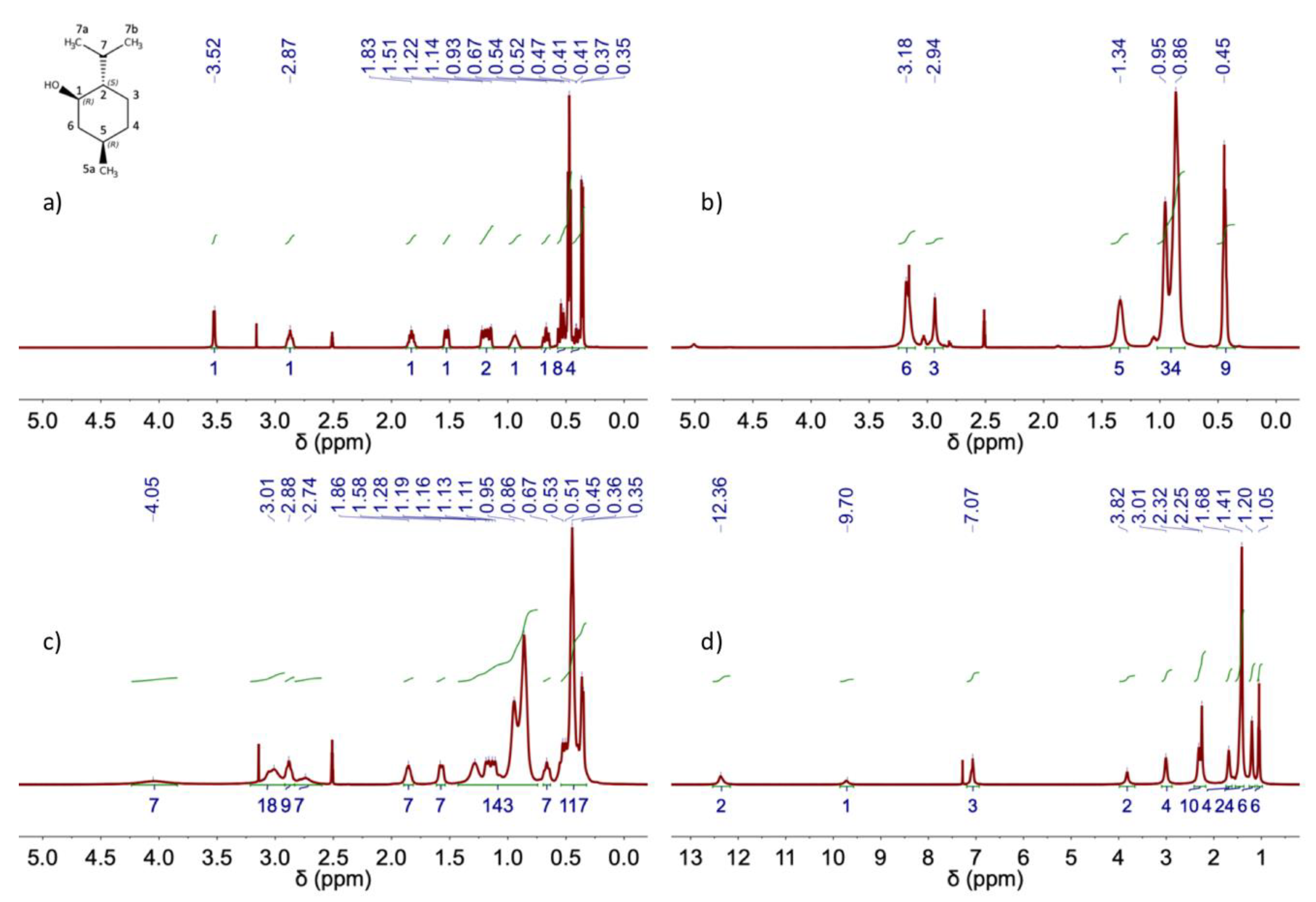

| δ (ppm) | ||||||||||

| Decanoic acid | Lidocaine | |||||||||

| HOOC | HOOC-CH2 | OC-CH2-CH2-(CH2)6 | (CH2)6 | CH3 | NH | Ar-H | Ar-CH3 | OC-CH2-N | CH2CH3 | CH2CH3 |

| 12.36 (2H) |

2.32 (4H+6H) |

1.68 (4H) |

1.41 (24H) |

1.05 (6H) |

9.70 (1H) |

7.07 (3H) |

2.25 (6H+4H) |

3.82 (2H) |

3.01 (4H) |

1.20 (6H) |

| δ (ppm) | |||||

| L-Menthol | Aliquat 336 TG | Aliq:LMet (3:7) | |||

| L-Menthol | H1 | 2.87 (1H) | 2.74 (7H) | Aliq-LMet (3:7) | |

| H2 | 0.67 (1H) | 0.67 (7H) | |||

| H3a | 1.22 (1H) | 1.19-1.16 | |||

| H3b | 0.41 (1H) | 0.53-0.35 | |||

| H4a | 1.14 (1H) | 1.12 | |||

| H4b | 0.54 (1H) | 0.53-0.35 | |||

| H5 | 0.93 (1H) | 0.95-0.86 | |||

| H6a | 1.51 (1H) | 1.58 (7H) | |||

| H6b | 0.52 (1H) | 0.53-0.35 | |||

| H7 | 1.83 (1H) | 1.86 (7H) | |||

| CH3 5a | 0.47 (3H) | 0.45 | |||

| CH3 7a | 0.36 (3H) | 0.36 | |||

| CH3 7b | 0.47 (3H) | 0.45 | |||

| OH | 3.52 (1H) | 4.05 (7H) | |||

| Aliquat-336 TG | +N-CH3 | 2.94 (3H) | 2.88 (9H) | ||

| +NCH2CH2(CH2)nCH3 | 3.18 (6H) | 3.01 (18H) | |||

| +NCH2CH2(CH2)nCH3 | 1.34 (5H) | 1.28 | |||

| +NCH2CH2(CH2)nCH3 | 0.95-0.86 (34H) | 0.95-0.86 | |||

| +NCH2CH2(CH2)nCH3 | 0.45 (9H) | 0.45 | |||

| DES | Density (g/cm3) Heating and stirring |

Density (g/cm3) Ultrasound |

| Hydrophilic DES |

||

| ChCl: U (1:2) | 1.1846±0.0060 | 1.1646±0.0016 |

| ChCl:EG (1:2) | 1.0931±0.0010 | 1.1024±0.0045 |

| ChCl:EG (1:3) | 1.0953±0.0021 | 1.1050±0.0072 |

| ChCl:EG (1:4) | 1.0995±0.0035 | 1.1026±0.0109 |

| ChCl: Ox (1:1) | 1.2289±0.0034 | 1.2103±0.0012 |

| Hydrophobic DES |

||

| Aliq: LMet (3:7) Lid:Ac.Dec (1:2) |

0.8862±0.0025 0.9466±0.0020 |

0.8877±0.0018 0.9489±0.0012 |

| Hydrophilic DES |

Density (g/cm3) | Reference |

| ChCl:EG (1:2) | 1.12 | [40] |

| ChCl:EG (1:3) | 1.12 | [41] |

| ChCl:EG (1:4) | 1.11 | [42] |

| ChCl:U (1:2) | 1.21 | [43] |

| ChCl:U (1:2) | 1.25 | [44] |

| ChCl:Ox (1:1) | 1.15 | [11] |

| Hydrophofic DES |

||

| Aliq:LMet (3:7) | 0.88 | [31] |

| Lid:Ac.Dec (1:2) | 0.89 | [45] |

|

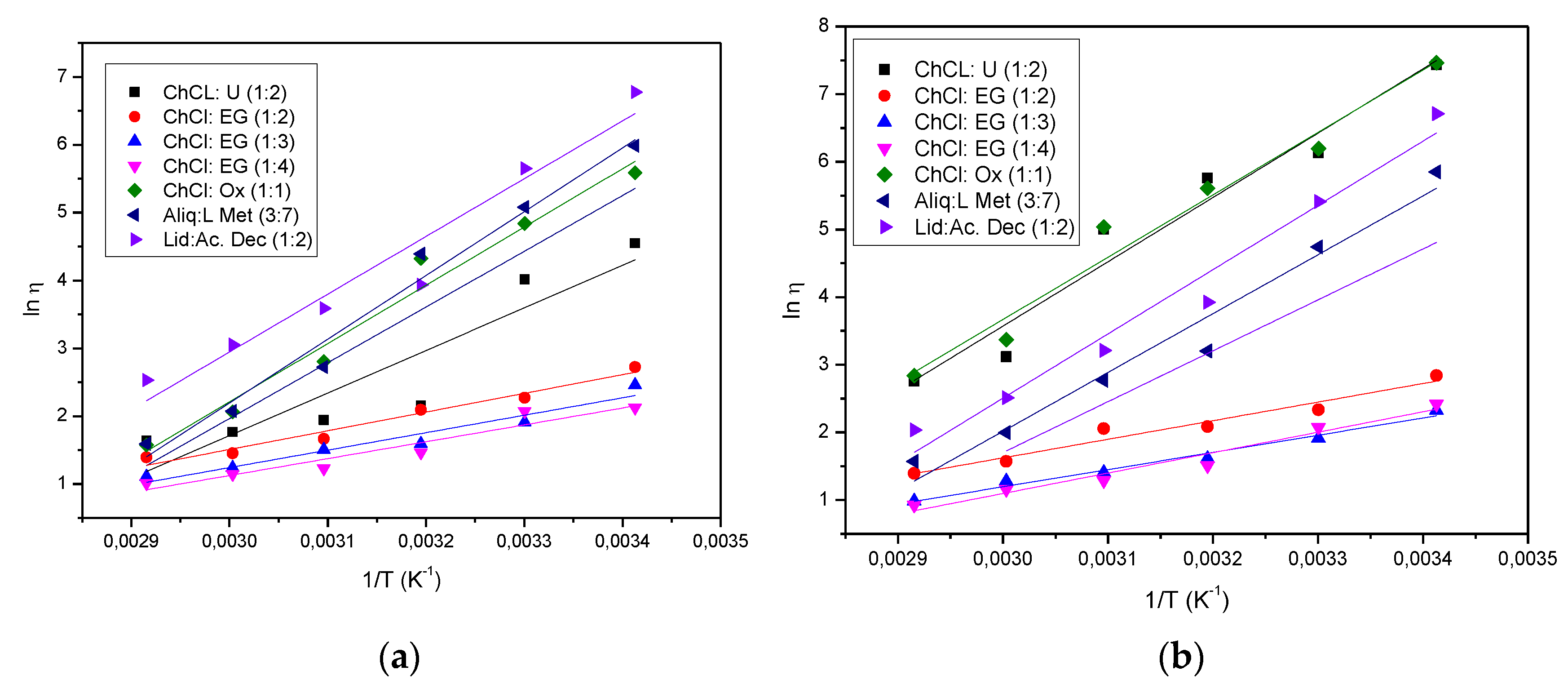

Hydrophilic DES |

Eⴄ (KJ/mol) |

ⴄ0 |

| ChCl: U (1:2) | 79.04 | 1.46E-11 |

| ChCl: U (1:2) US | 53.30 | 2.94E-08 |

| ChCl:EG (1:2) | 22.85 | 1.33E-03 |

| ChCl:EG (1:2) US | 22.93 | 1.15E-03 |

| ChCl:EG (1:3) | 21.13 | 1.62E-03 |

| ChCl:EG (1:3) US | 21.38 | 1.54E-03 |

| ChCl:EG (1:4) | 25.11 | 3.48E-04 |

| ChCl:EG (1:4) US | 20.67 | 1.77E-03 |

| ChCl: Ox (1:1) | 76.68 | 3.77E-11 |

| ChCl: Ox (1:1) US | 71.40 | 5.90E-11 |

|

Hydrophobic DES |

||

| Aliq: LMet (3:7) Aliq: LMet (3:7) US Lid: Ac.Dec (1:2) Lid: Ac.Dec (1:2) US |

78.97 71.48 72.33 78.14 |

5.17E-12 1.29E-10 3.48E-11 5.11E-12 |

| Chemical reagents | Reagent name | Manufacturer | Mass fraction purity |

|---|---|---|---|

| C5H14NOCl | Choline chloride | PanReac AppliChem | High purify grade |

| CO(NH₂)₂ | Urea | PanReac AppliChem | >99% (N) |

| CH2OH-CH2OH | Ethylene glycol | PanReac AppliChem | Pure |

| H2C2O4.2H2O | Oxalic acid 2-hidrate | PanReac AppliChem | 99% |

| C10H20O | L-Menthol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 99% |

| [CH3(CH2)7]3NCH3Cl | Aliquat 336 TG | Thermo Fisher Scientific | - |

| C14H22N2O | Lidocaine | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 97.5% |

| CH₃(CH₂)₈COOH | Decanoic acid | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 99% |

| DES | HBA | HBD | HBA:HBD ratios |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChCl: U (1:2) | Choline chloride | Urea | 1:2 |

| ChCl:EG (1:2) | Choline chloride | Ethylene glicol | 1:2 |

| ChCl:EG (1:3) | Choline chloride | Ethylene glicol | 1:3 |

| ChCl:EG (1:4) | Choline chloride | Ethylene glicol | 1:4 |

| ChCl: Ox (1:1) | Choline chloride | Oxalic acid | 1:1 |

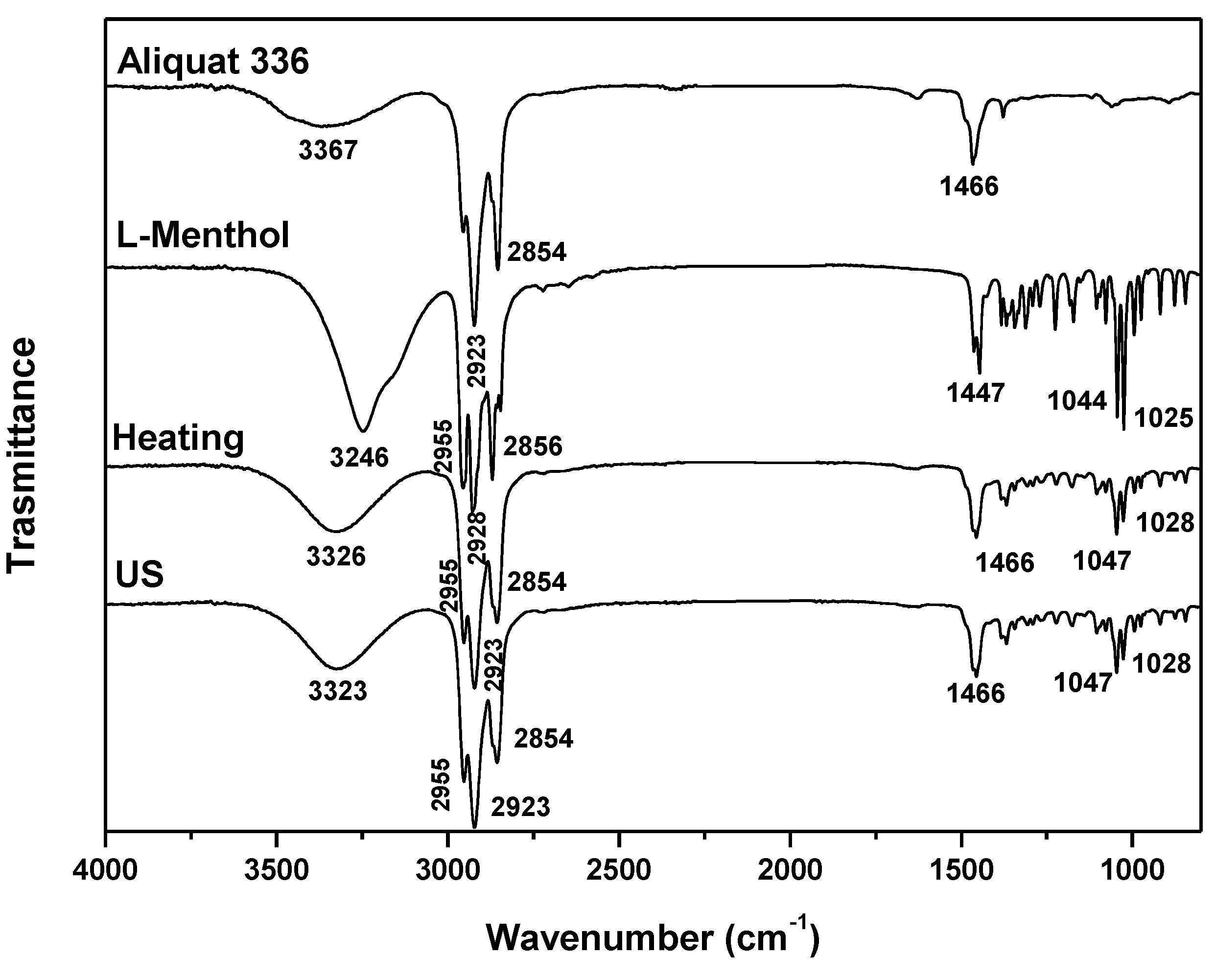

| Aliq: LMet (3:7) | Aliquat 336 | L-Menthol | 3:7 |

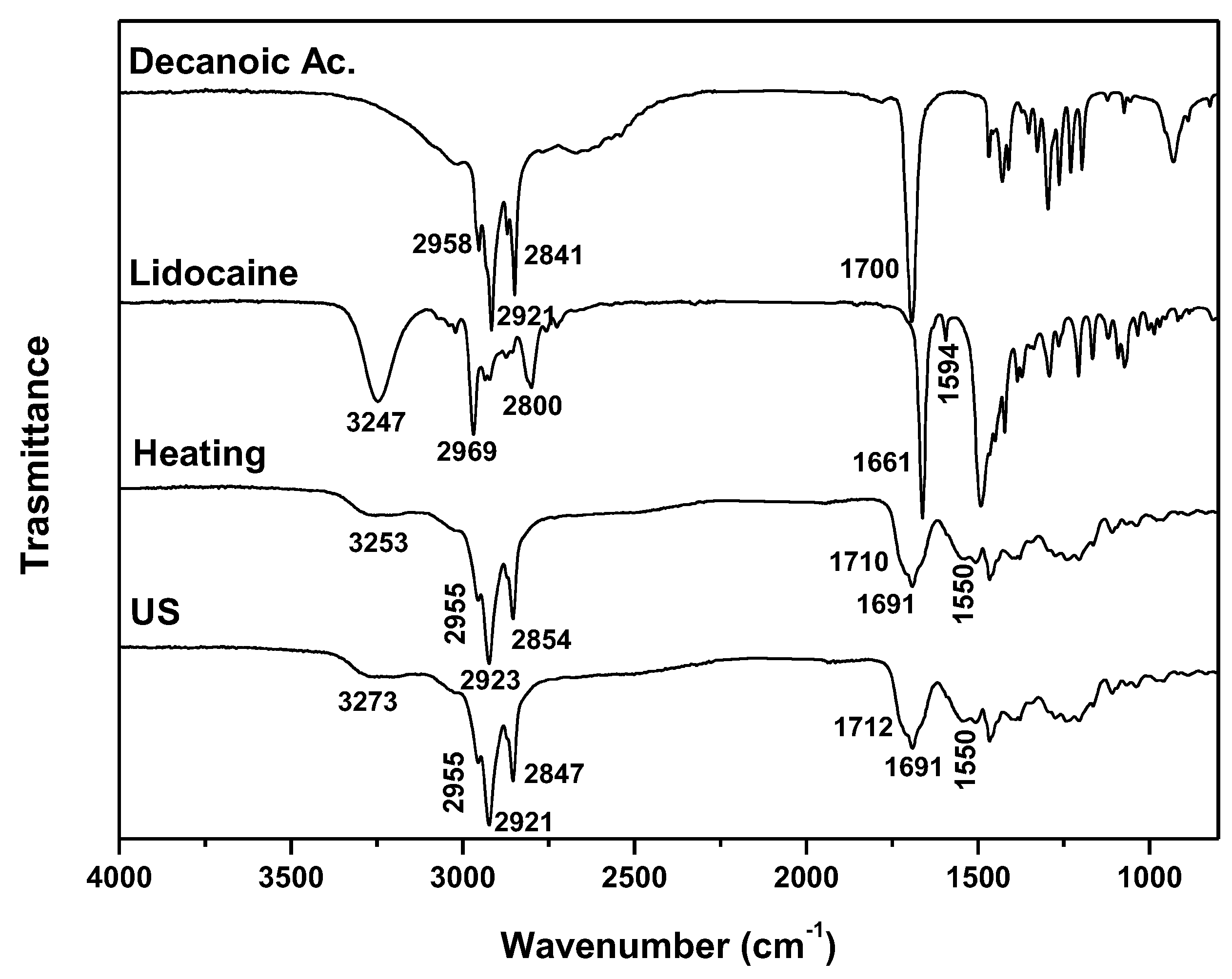

| Lid: Ac Dec (1:2) | Lidocaine | Decanoic acid | 1:2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).