Submitted:

30 April 2024

Posted:

01 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

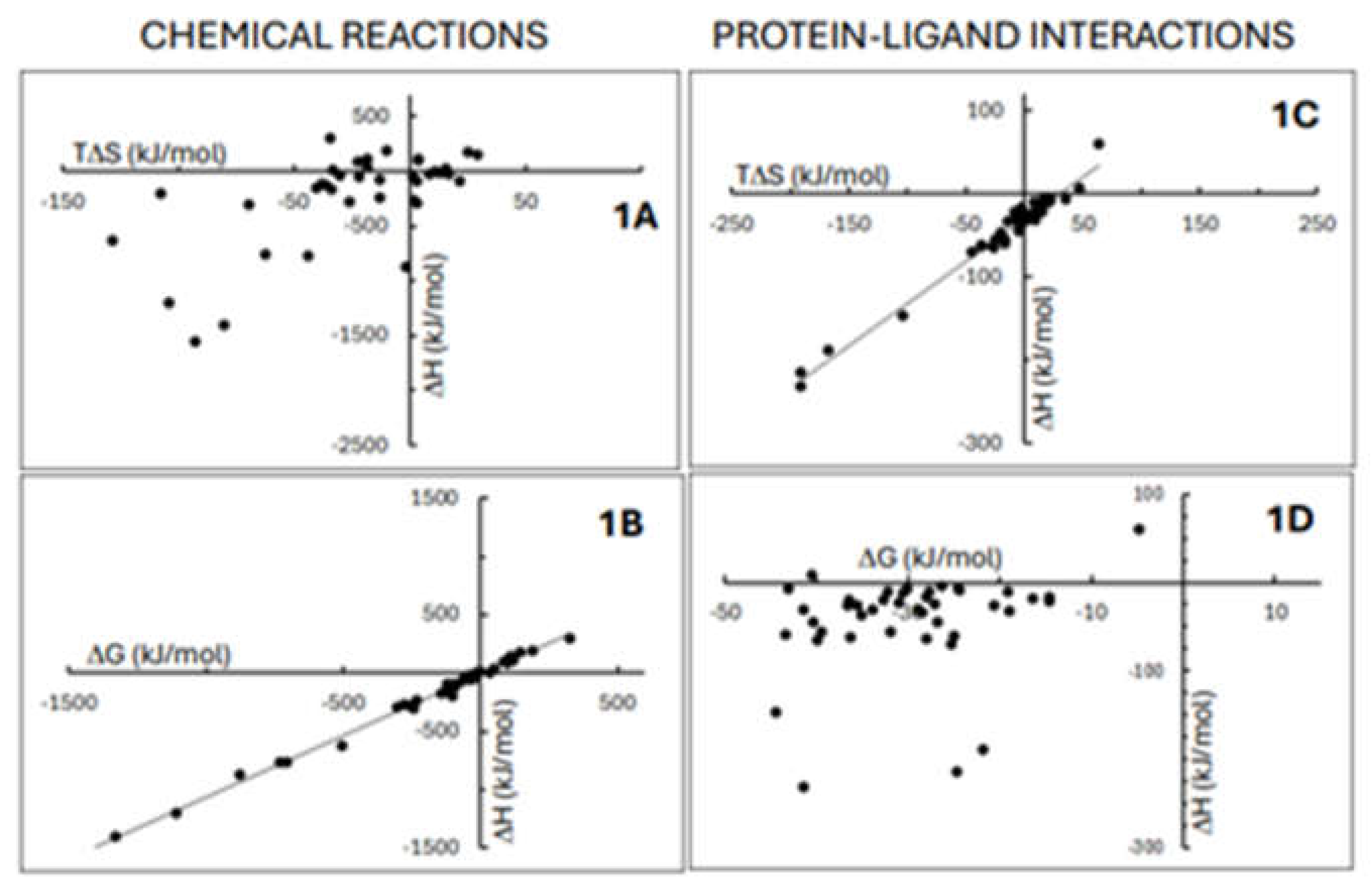

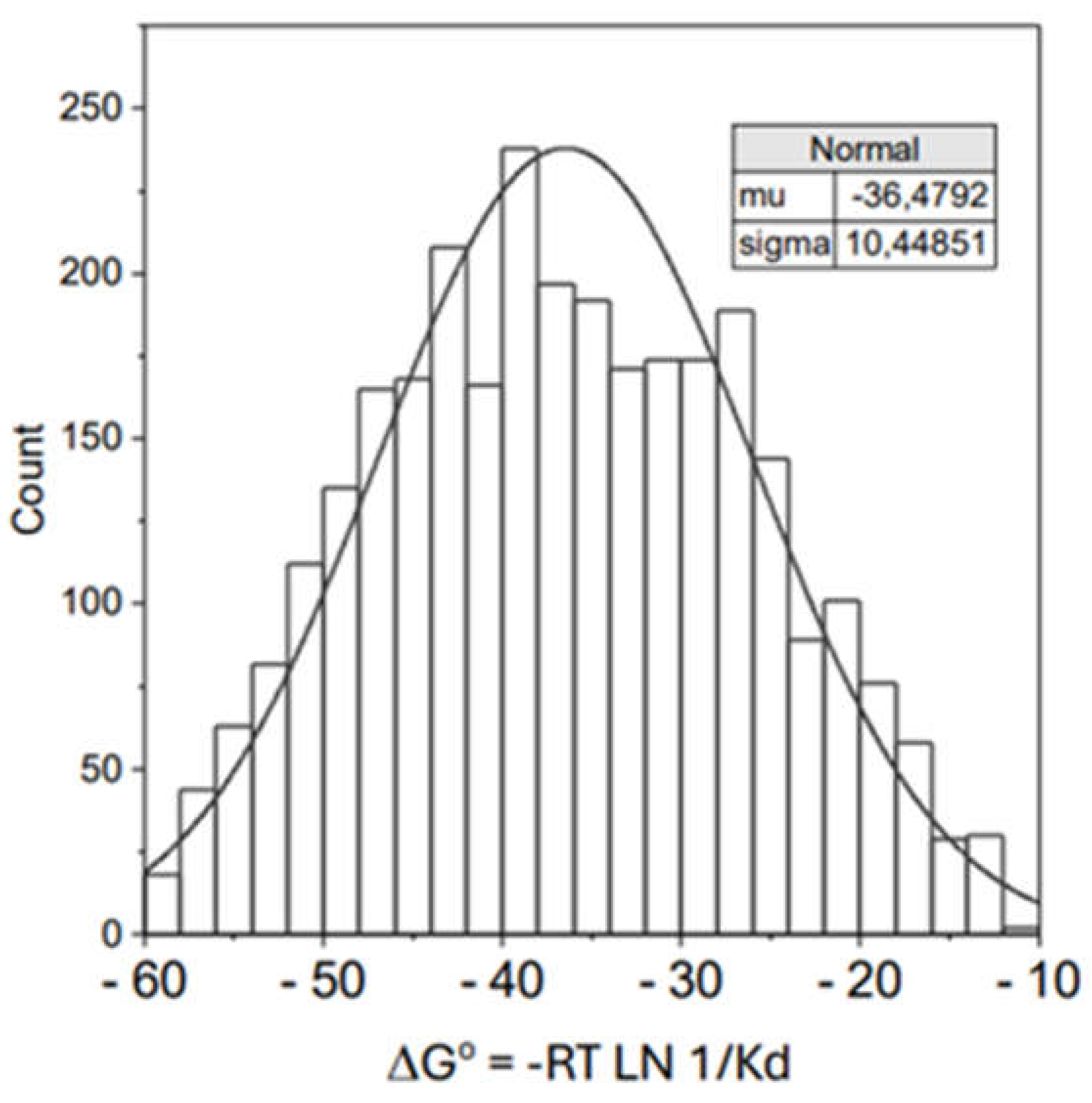

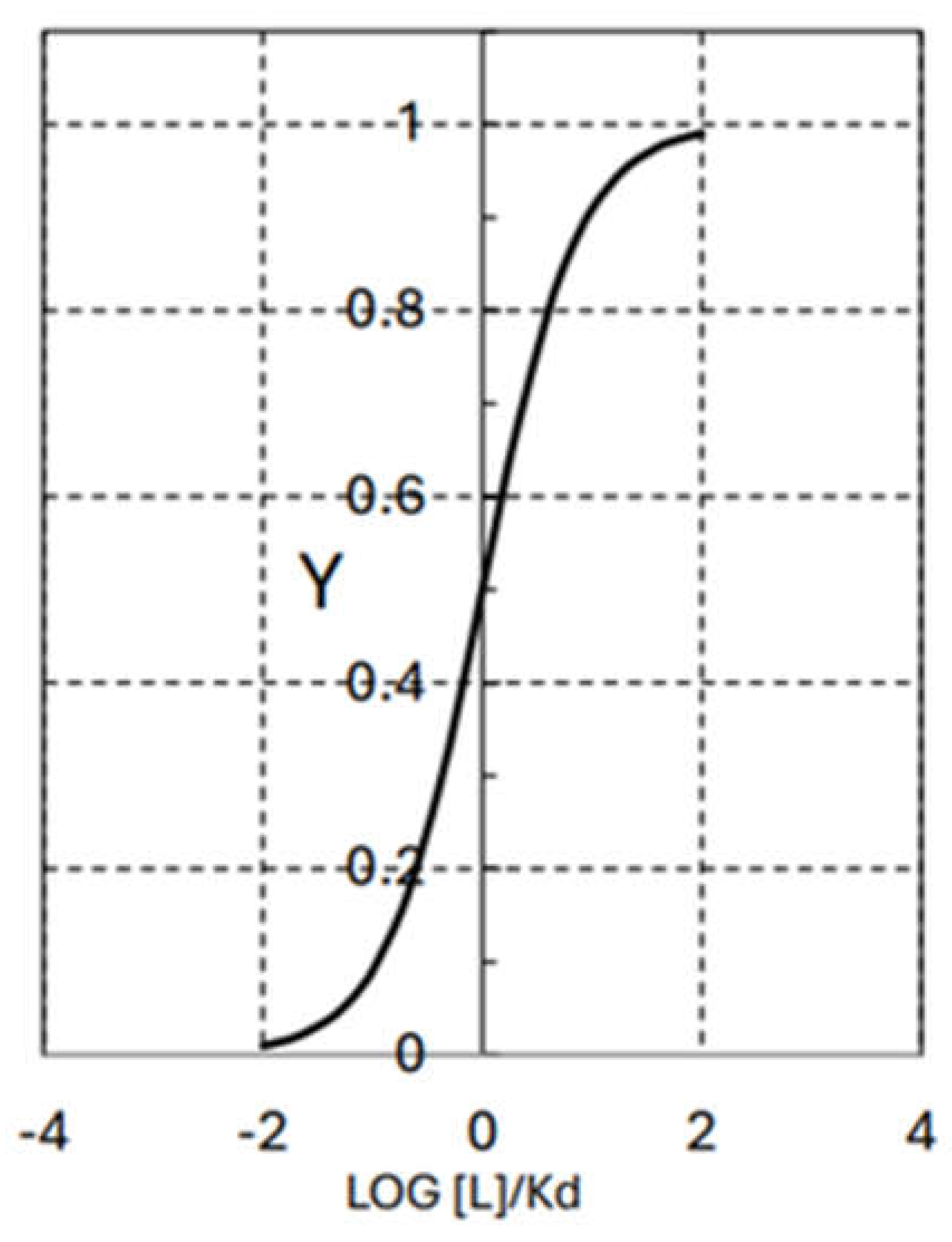

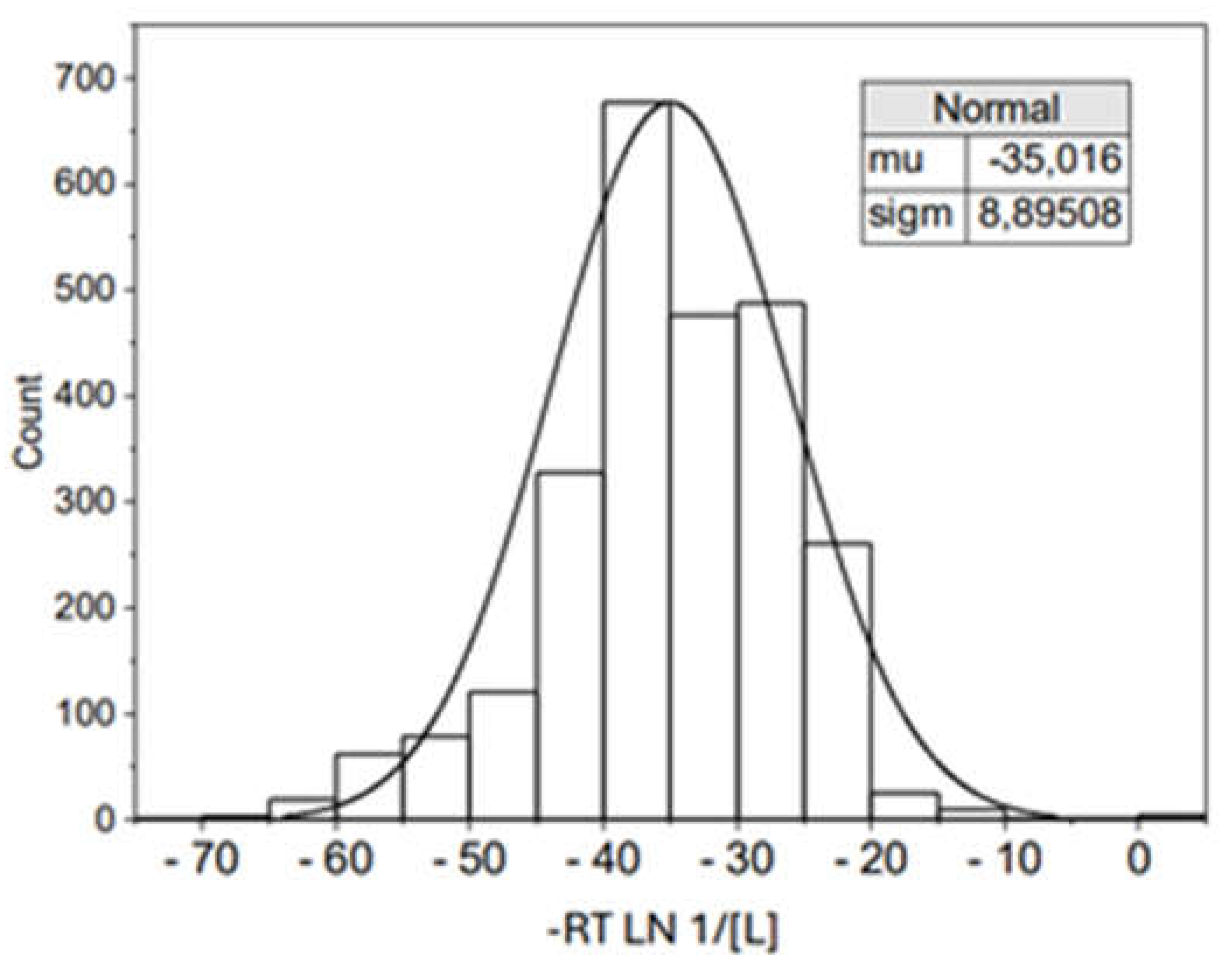

2. Results and Discussion

3. Methods

Acknowledgments

References

- Aggarwal, S.; Tanwar, N.; Singh, A.; Munde, M. Formation of Protamine and Zn−Insulin Assembly: Exploring Biophysical Consequences. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 41044–41057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberty, R.A. Calculation of Standard Transformed Gibbs Energies and Standard Transformed Enthalpies of Biochemical Reactants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 353, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, P.; De Paula, J. Physical Chemistry for Life Sciences. Oxford University Press. ( 2006.

- Camero, S. Thermodynamics of the interaction between Alzheimer's disease related tau protein and DNA. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Z-G. Using Implicit-Solvent Potentials to Extract Water Contributions to Enthalpy−Entropy Compensation in Biomolecular Associations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 6825–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.; et al. Involvement of water in carbohydrate-protein binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 12238–12247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A. Thermodynamic analysis of biomolecular interactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1999, 3, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish-Bowden, A. Enthalpy–entropy compensation and the isokinetic temperature in enzyme catalysis. J Biosci.

- Crisalli, A.M.; Cai, A.; Cho, B.P. Probing the Interactions of Perfluorocarboxylic Acids of Various Chain Lengths with Human Serum Albumin: Calorimetric and Spectroscopic Investigations. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2023, 36, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danesha, N.; Sedighia, Z.N.; Beigolib, S.; Sharifi-Radc, A.; Saberid, M.R. & Chamania, J. Determining the binding site and binding affinity of estradiol to human serum albumin and holo-transferrin: Fluorescence spectroscopic, isothermal titration calorimetry and molecular modeling approaches. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 2018, 36, 1747–1763. [Google Scholar]

- Denbigh, K. in The Principles of Chemical Equilibrium (Fourth Ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1981).

- Dragan, A.I.; Read, C.M.; Crane-Robinson, C. Enthalpy-entropy compensation: The role of solvation. Eur. Biophys. J. 2017, 46, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J.D. Win some, lose some: Enthalpy-entropy compensation in weak intermolecular interactions. Chemistry & Biology 1995, 2, 709–712. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, JM, Zhao, M.; Fink, M.J.; Kang, K.; Whitesides G.M. The Molecular Origin of.

- Enthalpy/Entropy Compensation in Biomolecular Recognition. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018, 47, 223–250. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukada, H.; Sturtevant, J.M.; Quiocho, F.A. Thermodynamics of the binding of L-arabinose and of D-galactose to the L-arabinose-binding protein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 13193–13198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, P.D.; Andley, U.P. In vitro interactions of histones and α-crystallin Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2018, 15, 7–12. 15.

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (D.R. Lide (Ed.) Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (D.R. Lide, Ed.) CRC Press. 85th edition, 2004-2005.

- Hinz, H.J.; Steininger, G.; Schmid, F.; Jaenide, R. Studies on an energy structure-function relationship of dehydrogenases. II. Calorimetric investigations on the interaction of coenzyme fragments with pig skeletal muscle lactate dehydrogenase. FEBS Lett. 1978, 87, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Honnappa, S.; Cutting, B.; Jahnke, W.; Seelig, J.; Steinmetz, M.O. Thermodynamics of the Op18/Stathmin-Tubulin Interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 38926–38934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrapunov, S. The Enthalpy-entropy Compensation Phenomenon. Limitations for the Use of Some Basic Thermodynamic Equations. Curr Protein Pept Sci, 19, 1088–1091.

- Levine, I.N. in Physical Chemistry (Fith Ed. McGraw Hill, New York, 2002).

- Lewis, G.N.; Randall, M. in Thermodynamics. 2nd Edition. McGraw-Hill.

- Liu, L.; Yang, C.; Guo, Q-X. A study on the enthalpy-entropy compensation in protein unfolding. Biophys. Chem. 2000, 84, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumry, R. Uses of enthalpy-entropy compensation in protein research. Biophys.Chem. 2003, 105, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.F.; Clements, J.H. . Correlating Structure and Energetics in Protein-Ligand Interactions: Paradigms and Paradoxes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, P.L.; Barón, C.; López-Mayorga, O.; Jiménez, J.S.; Cortijo, M. AMP and IMP binding to glycogen phosphorylase b. A calorimetric and equilibrium dialysis study. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 9384–9389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olsson, T.S.G.; Ladbury, J.E.; Pitt, W.R.; Williams, M.A. Extent of enthalpy-entropy compensation in protein-ligand interactions. Protein Sci. 2011, 20, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paketurytė V, Linkuvienė V, Krainer G, Chen WY, Matulis D. Repeatability, precision, and accuracy of the enthalpies and Gibbs energies of a protein-ligand binding reaction measured by isothermal titration calorimetry. Eur Biophys J. 48, 139-152.

- Pan, A.; Kar, T.; Rakshit, A.K.; Moulik, S.P. Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation (EEC) Effect: Decisive Role of Free Energy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 10531–10539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccati, F.; Jiménez-Osés, G. Enthalpy−Entropy Compensation in Biomolecular Recognition: A Computational Perspective. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11122–11130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ruiz, J.M. Differential scanning calorimetry of proteins. Subcell Biochem 1995, 24, 133–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, K. Entropy-Enthalpy compensation: Fact or artifact. Protein Sci. 2001, 10, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.H.; Lou, Y.Y.; Zhou, K.L.; Pan, D.Q. (2018) Elucidation of intermolecular interaction of bovine serum albumin with Fenhexamid: A biophysical prospect. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B, Biol. 2018, 180, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhany, M.; Negishi, M. Characterization of specific donor binding to α1,4Nacteylhexosaminyltransferase EXTL2 using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry. Methods Enzymol. 2006, 416, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi, Y.; Panahi-Azar, V.; Barzegar, A.; Dolatabadi, J.E.N.; Dehghan, P. Spectroscopic, thermodynamic and molecular docking studies of bovine serum albumin interaction with ascorbyl palmitate food additive. BioImpacts, 2017, 7, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, H.; Zhuang, C.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Quan, C.; Dong, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Xiu, Z. Trivaric acid, a new inhibitor of PTP1b with potent beneficial effect on diabetes. Life Sciences 2017, 169, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, C.M.; Michmerhuizen, N.L.; Witte, A.B.; Van Winkle, M.; Zhou, D.; Sinniah, K. An Isothermal Titration and Differential Scanning Calorimetry Study of the G-Quadruplex DNA−Insulin Interaction. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 1784–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, I.; Yamanaka, M. Titration calorimetry of anesthetic-protein interaction: Negative enthalpy of binding and anesthetic potency. Biophys. J. 1997, 72, 1812–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- et al. “Selected Values of Chemical Thermodynamic Properties.” Nat. Bur. Stand. Tech. Notes 270-3, 270–274, 270-5, 270–276. 270-7 and 270-8. Washington, (1968-1981).

- Wang, R. Fang, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, S. The PDB bind Database for Protein-Ligand Complexes with known Three-Dimensional Structures. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 2977–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart DS, Guo A, Oler E, Wang F, Anjum A, Peters H, Dizon R, Sayeeda Z, Tian S, Lee BL, Berjanskii M, Mah R, Yamamoto M, Jovel J, Torres-Calzada C, Hiebert-Giesbrecht M, Lui VW, Varshavi D, Varshavi D, Allen D, Arndt D, Khetarpal N, Sivakumaran A, Harford K, Sanford S, Yee K, Cao X, Budinski Z, Liigand J, Zhang L, Zheng J, Mandal R, Karu N, Dambrova M, Schiöth HB, Greiner R, Gautam V. the Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D622–D631.

- Ylilauri, M.; Mattila, E.; Nurminen, E.M.; Käpylä, J.; Niinivehmas, S.P.; Määttä, J.A.; Pentikäinen, U.; Ivaska, J.; Pentikäinen, O.T. Molecular mechanism of T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase (TCPTP) activation by mitoxantrone. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2013, 1834, 1988–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ΔHo (kJ/mol) | ΔGo (kJ/mol) | TΔSo (kJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ½ Cl2 + O2 ↔ ClO2 (a) | 102.5 | 120.5 | -18 |

| ½ Cl2 + ½ O2 + ½ H2 ↔ HClO (a) | -78.7 | -66.1 | -12.6 |

| ½ Cl2 + ½ F2 ↔ FCl (a) | -54.5 | -55.9 | 1.4 |

| ½ Cl2 + 3/2 F2 ↔ ClF3 (a) | -163.2 | -123.0 | -40.2 |

| ½ Br2 + ½ Cl2 ↔ BrCl (a) | 14.6 | -0.98 | 15.58 |

| ½ I2 + ½ O2 ↔ IO (a) | 175.0 | 149.8 | 25.2 |

| ½ I2 + ½ F2 ↔ IF (a) | -95.7 | -118.5 | 22.8 |

| S + O2 ↔ SO2 (a) | -296.8 | -300.2 | 3.4 |

| S + ½ H2 ↔ HS (a) | 142.7 | 113.3 | 29.4 |

| S + H2 ↔ H2S (a) | -20.6 | -33.6 | 13 |

| S + 2 F2 ↔ SF4 (a) | -774.9 | -731.3 | -43.6 |

| S + 3 F2 ↔ SF6 (a) | -1209.0 | -1105.3 | -103.7 |

| ½ N2 + O2 ↔ NO2(a) | 33.2 | 51.3 | -18.1 |

| ½ N2 + H2 ↔ NH2 (a) | 184.9 | 194.6 | -9.7 |

| 3/2 N2 + ½ H2 ↔ HN3 (b) | 294.1 | 328.1 | -34 |

| ½ N2 + 3/2 H2 ↔ NH3 (b) | -46.1 | -16.5 | -29.6 |

| ½ H2 + ½ Br2 ↔ HBr (d) | -36.4 | -53.5 | 17.1 |

| H2O + ½ O2 ↔ H2O2 (d) | 98.1 | 116.8 | -18.7 |

| CO + H2 ↔ HCHO (d) | 2.0 | 34.6 | -32.6 |

| NO + ½ O2 ↔ NO2 (d) | -57.1 | -35.2 | -21.9 |

| C2H2 + 2 H2 ↔ C2H6(d) | -311.4 | -242.0 | -69.4 |

| CH3COOH + 2 O2 ↔ 2 CO2 + 2H2O (d) | -874.4 | -873.1 | -1.3 |

| C6H6 + 3 H2 ↔ C6H12 (d) | -205 | -97.5 | -107.5 |

| 3 C2H2 ↔ C6H6 (d) | -631.2 | -503.3 | -127.9 |

| C2H4 + 3 O2 ↔ 2 CO2+ 2 H2O (d) | -1411 | -1331 | -80 |

| CH3OH + 3/2 O2 ↔ CO2 + 2 H2O (d) | -765.0 | -702 | -63 |

| C2H6 + 7/2 O2 ↔ 2 CO2 + 3 H2O (d) | -1560 | -1467 | -93 |

| C2H2 + H2 ↔ C2H4 (b) | -174 | -141 | -33 |

| C2H4 + H2 ↔ C2H6 (b) | -137 | -101 | -36 |

| C4H8 + H2 ↔ C4H10 (b) | -126 | -88.4 | -37.6 |

| ½ H2 + ½ F2 ↔ HF (c) | -271 | -273.3 | 2.3 |

| ½ H2 + ½ Cl2 ↔ HCl (c) | -92.3 | -95.4 | 3.1 |

| ½ N2 + ½ O2 ↔ NO (c) | 90.3 | 86.5 | 3.8 |

| ½ Cl2 + ½ O2 ↔ ClO (f) | 102 | 98.1 | 3.9 |

| CO + ½ O2 ↔ CO2 (c) | -283 | -257 | -26 |

| H2 + ½ O2 ↔ H2O (c) | -242 | -229 | -13 |

| N2 + ½ O2 ↔ N2O (f) | 82.1 | 104.2 | -22.1 |

| ATP + H2O ↔ ADP + P (e) | -24.4 | -37.6 | 13.2 |

| ADP + H2O ↔ AMP + P (e) | -25.7 | -34.4 | 8.7 |

| AMP + H2O ↔ Adenosine + P (e) | -3.23 | -14.4 | 11.17 |

| ΔHo (kJ/mol) | ΔGo (kJ/mol) | TΔSo (kJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTP1b + Trivaric acid (a) | -189 | -21.8 | -167.2 |

| TCPTP + Mitoxantrone (b) | -31.4 | -33.9 | 2.5 |

| Insulin + Protamine (c) | -64 | -28 | -36 |

| Human Serum Albumin + BA (d) | -4.5 | -26.3 | 21.8 |

| Human Serum Albumin + HxA (d) | -7.8 | -30.1 | 22.3 |

| Human Serum Albumin + HpA (d) | -16.6 | -28 | 11.4 |

| Human Serum Albumin + OA (d) | -20.3 | -32.6 | 12.3 |

| Human Serum Albumin + NA (d) | -27.3 | -35.5 | 8.2 |

| Human Serum Albumin + DA(d) | -214.9 | -24.7 | -190.2 |

| Human Serum Albumin + PFBA (d) | -33.9 | -28.4 | -5.5 |

| Human Serum Albumin + PFHxA (d) | -10.6 | -32.2 | 21.6 |

| Human Serum Albumin + Genx (D) | -11.9 | -30.5 | 18.6 |

| Human Serum Albumin + PFHpA (d) | -21 | -36.6 | 15.6 |

| Human Serum Albumin + PFDA (d) | -23 | -30.9 | 7.9 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin + Chloroform (e) | -10.4 | -19 | 8.6 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase + NADH (f) | -31.6 | -28.9 | -2.7 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase + AMP (f) | -16.9 | -14.6 | -2.3 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase + ADP (f) | -21.9 | -14.5 | -7.4 |

| Phosphorylase b dimers + AMP (g) | -27 | -20.5 | -6.5 |

| Phosphorylase b dimers + AMP (g) | -70 | -25.2 | -44.8 |

| Phosphorylase b dimers + IMP (g) | -18 | -16.4 | -1.6 |

| Phosphorylase b dimers + IMP (g) | -33 | -18.9 | -14.1 |

| Tau protein + DNA (h) | -32 | -41.4 | 9.4 |

| L-Arabinose binding protein + L-Arabinose (i) | -62.7 | -36.3 | -26.4 |

| Carbonic Anhydrase II + Acetazolamide (j) | -59.5 | -43.3 | -16.2 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin + Fenhexamid (k) | -61.6 | -25 | -36.6 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin + Ascorbyl Palmitate (l) | 59.2 | -4.75 | 64 |

| α1,4-N-acetylhexosaminyltransferase + UDP (m) | -25.3 | -27 | 1.7 |

| α1,4-N-acetylhexosaminyltransferase + UDP-GalNAc(m) | -8.8 | -24.4 | 15.6 |

| α1,4-N-acetylhexosaminyltransferase + UDP-GlcNac (m) | -8.3 | -24.5 | 16.2 |

| Concavalin A + Trimannoside 1 (n) | -55.7 | -31.8 | -23.9 |

| Concavalin A + Trimannoside 2 (n) | -46.1 | -26.8 | -19.3 |

| α-Crystallin (o) | -26.3 | -36.5 | 10.2 |

| α-Crystallin + Histones (o) | -7.6 | -43 | 35.4 |

| βL-Crystallin (o) | -44.8 | -40.3 | -4.5 |

| βL-Crystallin + Histones (o) | -37.1 | -35 | -2.1 |

| γ- Crystallin (o) | -55.9 | -39.4 | -16.5 |

| γ- Crystallin + Histones (o) | -65.9 | -39.9 | -26 |

| Insulin + G-Quaduplex DNA (p) | -10.8 | -27.7 | 16.9 |

| Tubulin-GTP + Stathmin (q) | 7.1 | -40.5 | 47.6 |

| Human Serum Albumin + Estradiol (r) | -231.7 | -41.4 | 190.3 |

| Holo-Transferrin + Estradiol (r) | -147.2 | -44.3 | -102.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).