Submitted:

30 April 2024

Posted:

30 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids and Chemicals

2.2. Screening of the Signal Peptides for Extracellualr Producing APL

2.3. Construction of the Recombinant Signal Peptides

2.4. Enzyme Assay and SDS-PAGE

2.5. Transcription Detection by Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.6. Fed-Batch Fermentation of the Engineered Strain to Produce Extracellualr APL

3. Results

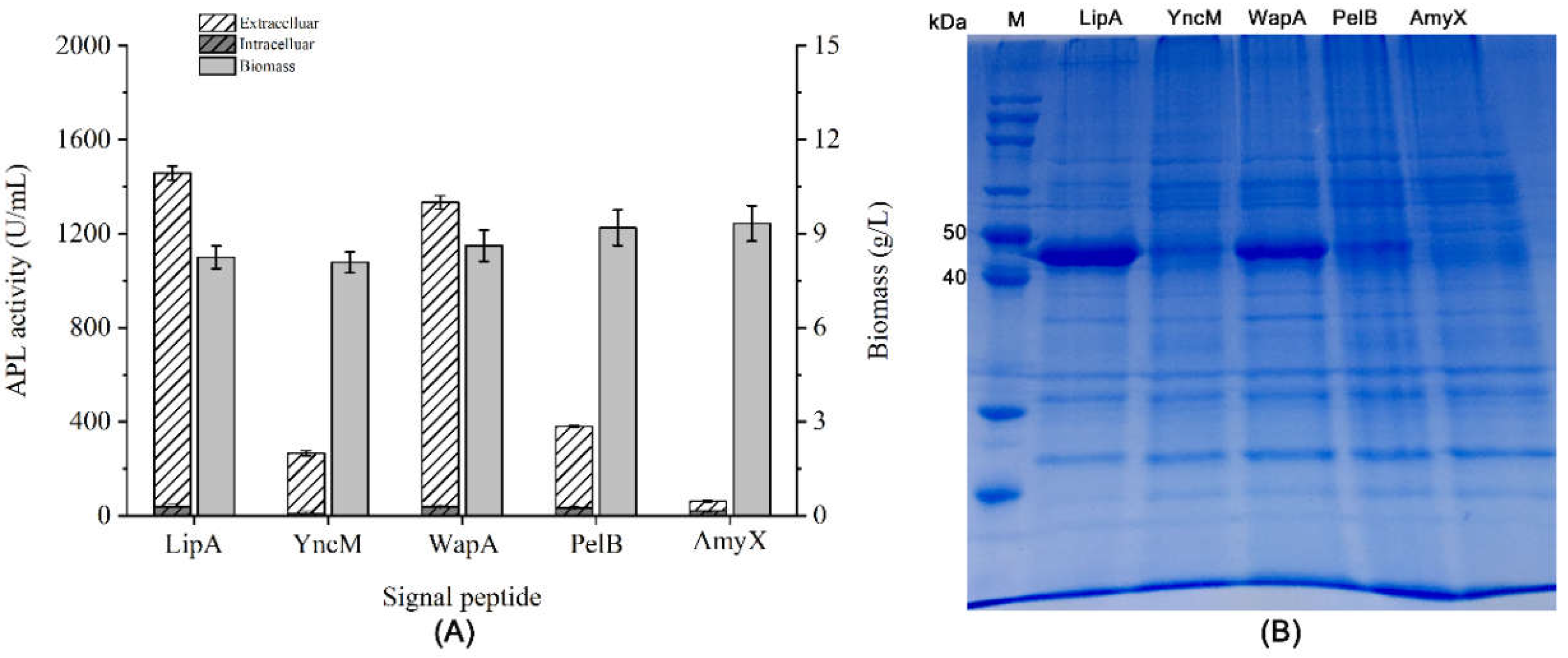

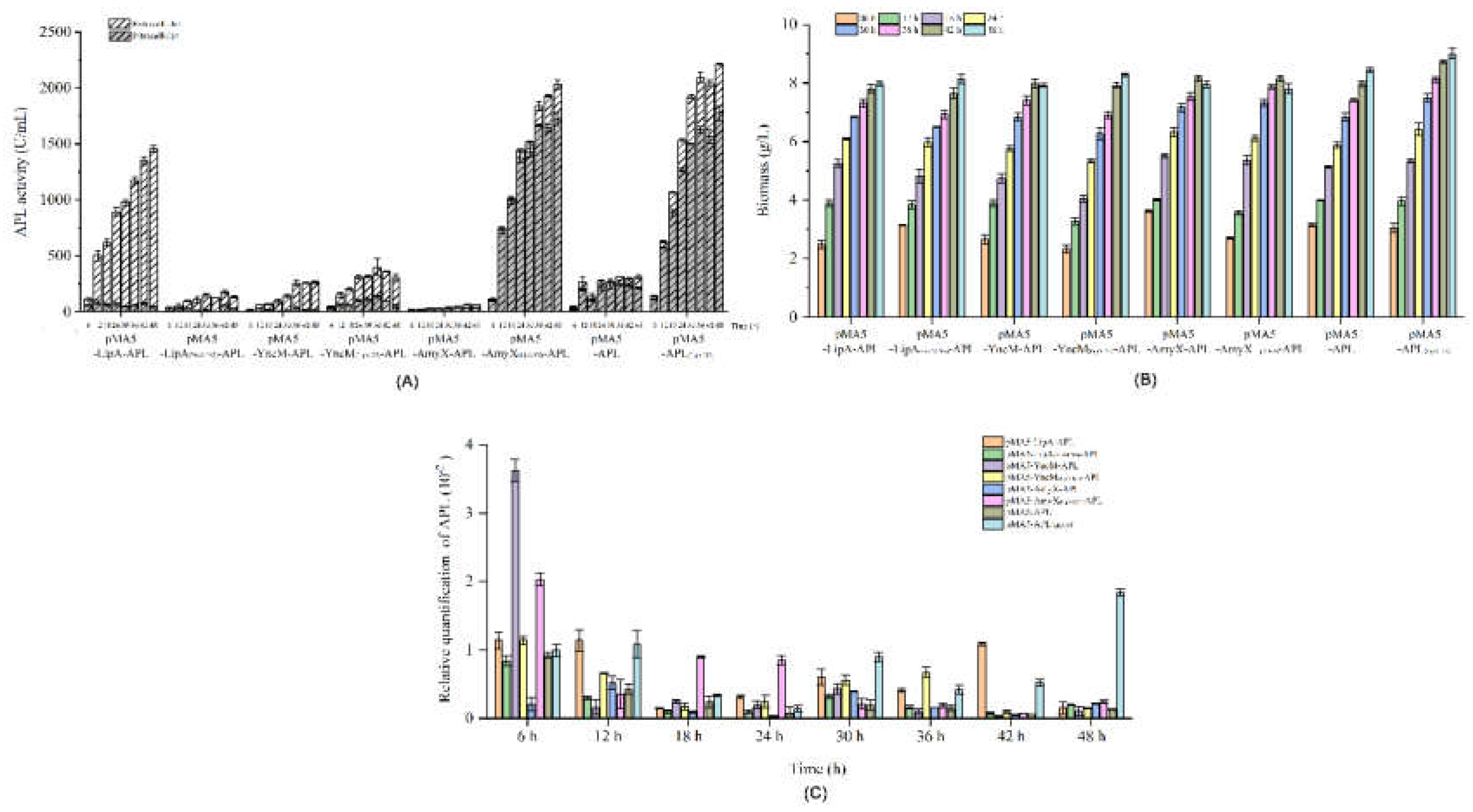

3.1. Effects of Different Signal Peptides on the Secretory Expression of APL in B. subtilis

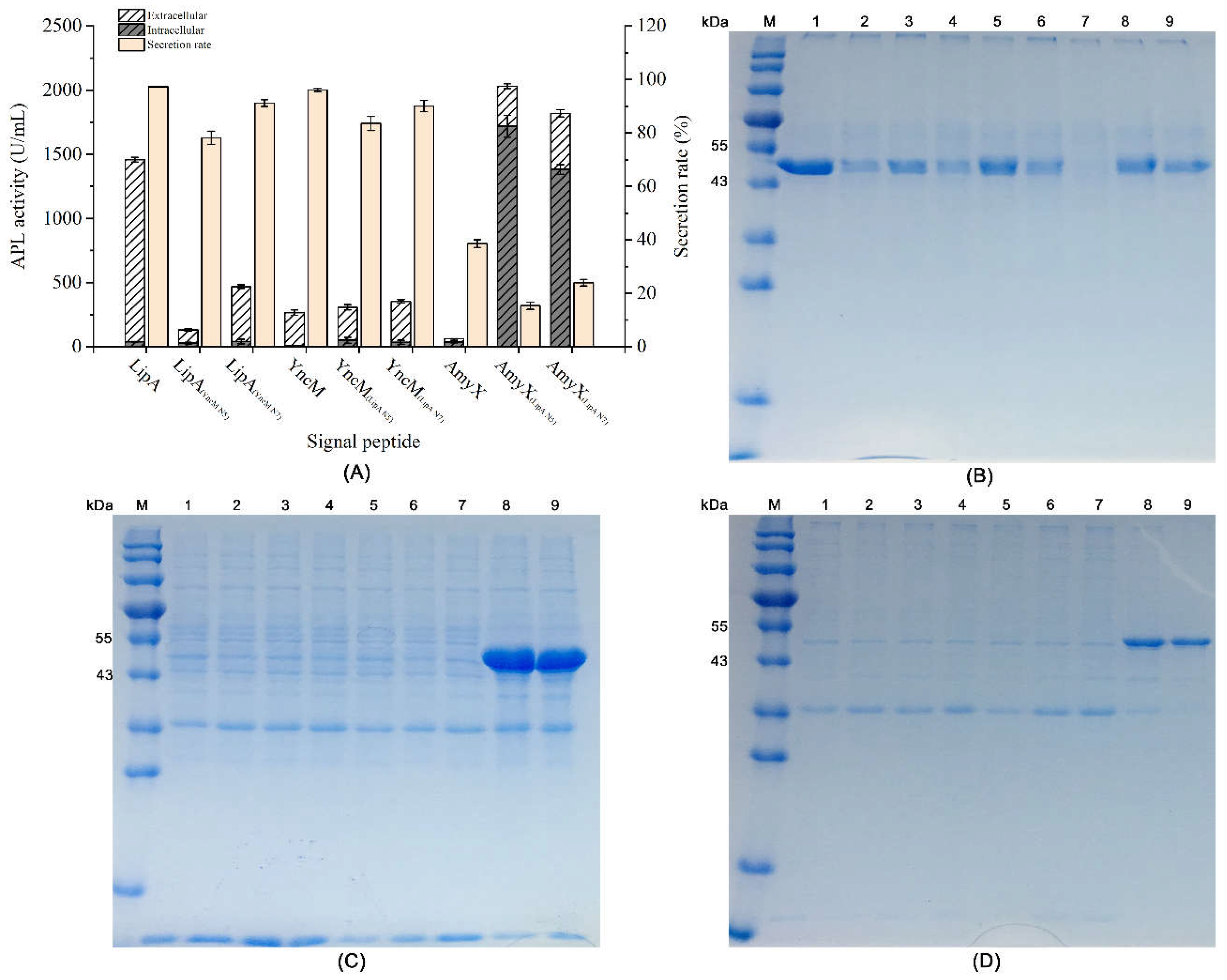

3.2. Effects of the N-Terminal 5-7 Amino Acids Sequences of the Signal Peptides on the Secretory Expression of APL in B. subtilis

3.3. Effects of the N-Terminal 5 Amino Acids Sequences of the Signal Peptides on the Gene Transcript in B. subtilis

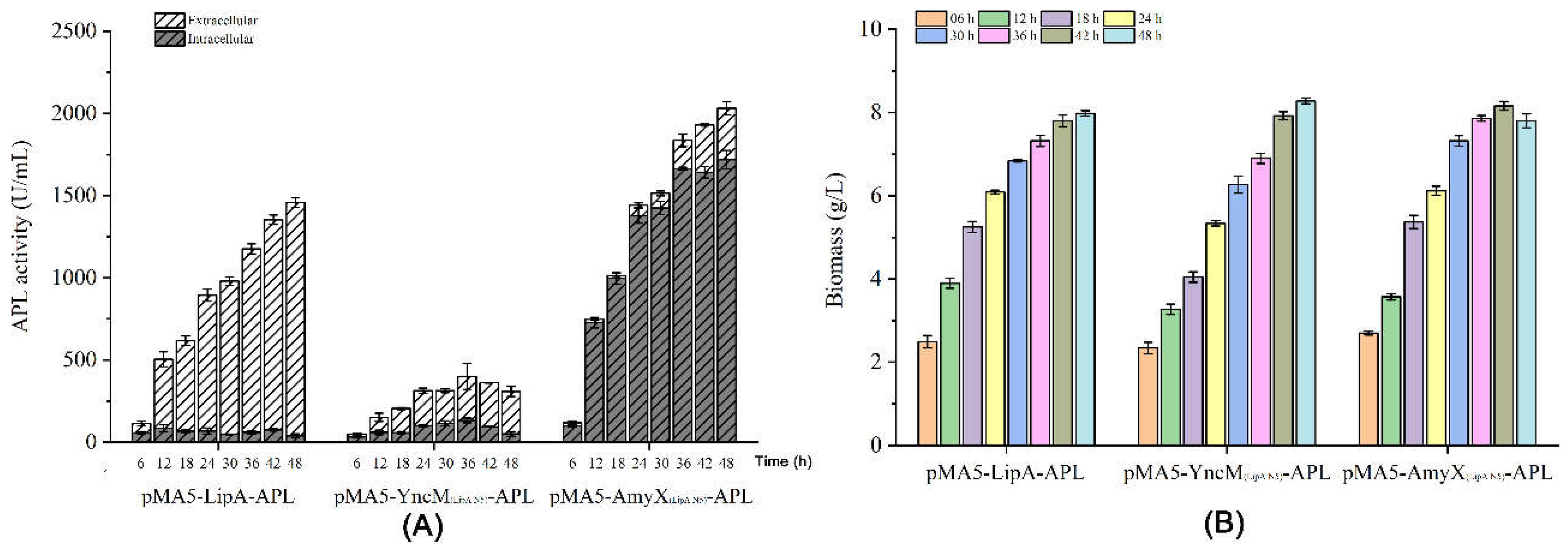

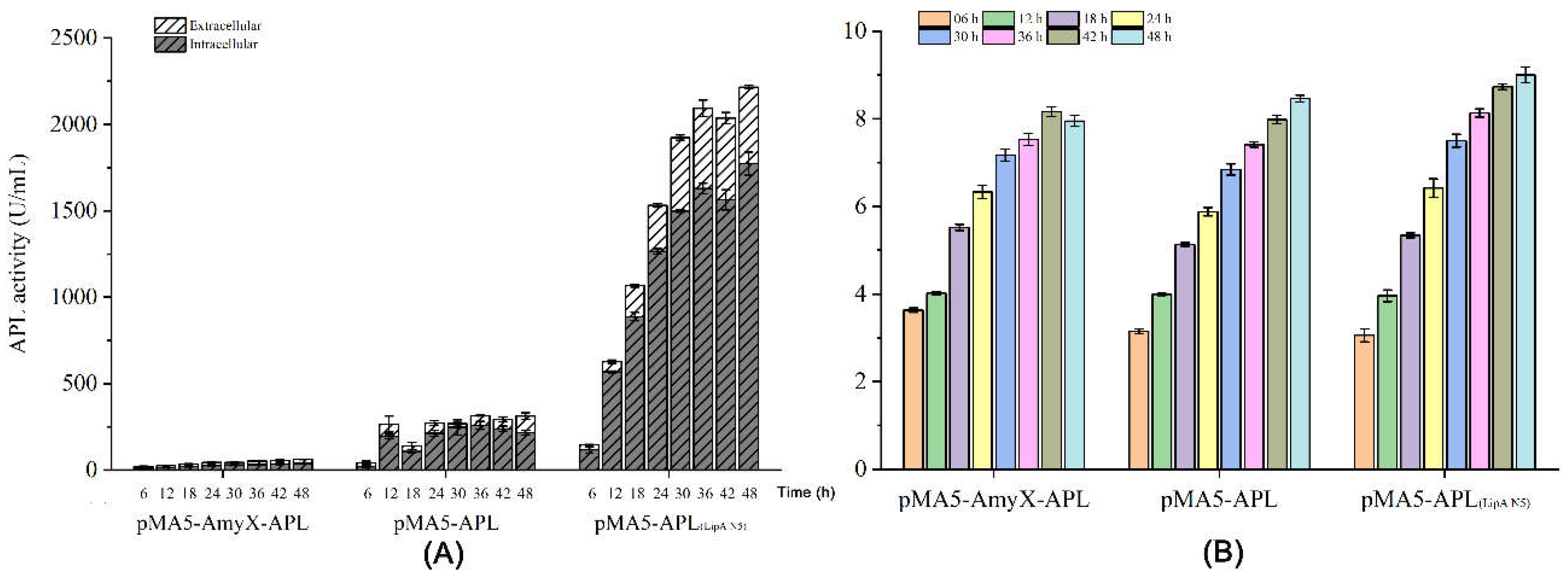

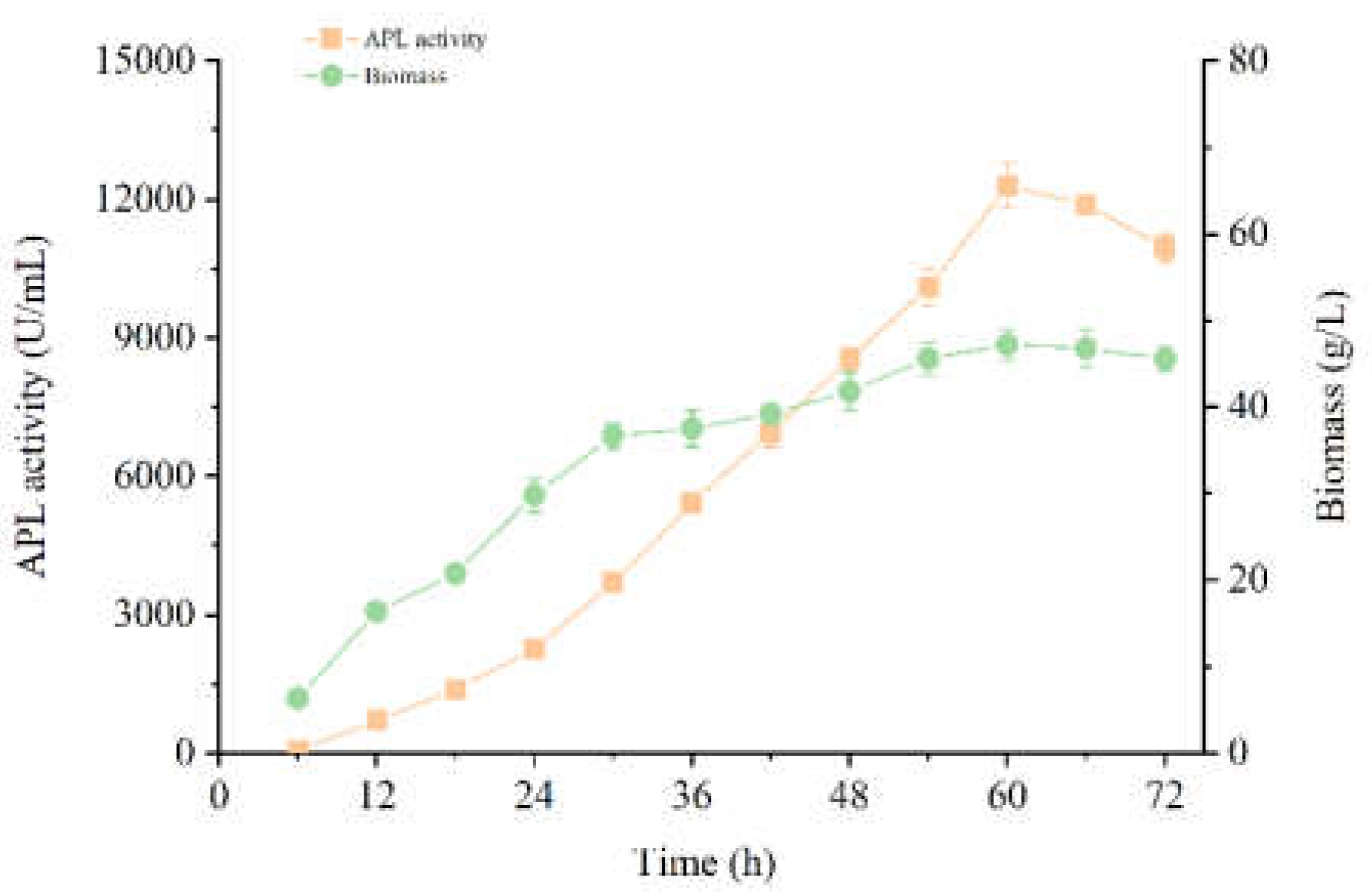

3.4. High Yield of APL through Fermentation of the Recombiant Strain in a 5-L Reactor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, K.; Su, L.; Wu, J. Enhancing extracellular pullulanase production in Bacillus subtilis through dltB disruption and signal peptide optimization. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2022, 194, 1206-1220. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhen, J.; Song, H.; Xu, J.; Zheng, H.; Bai, W. Trehalose Production Using Three Extracellular Enzymes Produced via One-Step Fermentation of an Engineered Bacillus subtilis Strain. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xuan, X.; Gao, R.; Xie, G. Increased Expression Levels of Thermophilic Serine Protease TTHA0724 through Signal Peptide Screening in Bacillus subtilis and Applications of the Enzyme. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhao, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Bai, W.; Song, H. Overexpression of a thermostable α-amylase through genome integration in Bacillus subtilis. Fermentation 2023, 9, 139. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Jin, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Chen, J.; Lv, X.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; et al. A pathway independent multi-modular ordered control system based on thermosensors and CRISPRi improves bioproduction in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, 6587-6600. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. A Programmable CRISPR/Cas9 Toolkit Improves Lycopene Production in Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2023, 89, e0023023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Qin, G.; Zhao, X.; Shen, Y. Enhanced extracellular beta-mannanase production by overexpressing PrsA lipoprotein in Bacillus subtilis and optimizing culture conditions. J Basic Microbiol 2022, 62, 815-823. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Hu, R.; Fang, Y.; Lyu, M.; Wang, S.; Lu, Z. Optimal Secretory Expression of Acetaldehyde Dehydrogenase from Issatchenkia terricola in Bacillus subtilis through a Combined Strategy. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Harwood, C.R.; Cranenburgh, R. Bacillus protein secretion: an unfolding story. Trends Microbiol 2008, 16, 73-79. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Guo, J.; Miao, L.; Liu, H. Enhancing the secretion of a feruloyl esterase in Bacillus subtilis by signal peptide screening and rational design. Protein Expr Purif 2022, 200, 106165. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C.; Minshull, J.; Govindarajan, S.; Ness, J.; Villalobos, A.; Welch, M. Engineering genes for predictable protein expression. Protein Expr Purif 2012, 83, 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Dabene, V.; Hendriks, M.; Zwartjens, P.; Pellaux, R.; Held, M.; Panke, S.; van Dijl, J.M.; Meyer, A.; van Rij, T. Signal Peptide Efficiency: From High-Throughput Data to Prediction and Explanation. ACS Synth Biol 2023, 12, 390-404. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Cao, L.; Qin, Z.; Li, S.; Kong, W.; Liu, Y. Tat-Independent Secretion of Polyethylene Terephthalate Hydrolase PETase in Bacillus subtilis 168 Mediated by Its Native Signal Peptide. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 13217-13227. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zuo, Z.; Xu, Y.; Song, C.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, C.; Xu, P.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, C. Twin-arginine signal peptide of Bacillus subtilis YwbN can direct Tat-dependent secretion of methyl parathion hydrolase. J Agric Food Chem 2014, 62, 2913-2918. [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Efficient secretory expression of Bacillus stearothermophilus alpha/beta-cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase in Bacillus subtilis. J Biotechnol 2021, 331, 74-82. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y. Heterologous Expression of Recombinant Transglutaminase in Bacillus subtilis SCK6 with Optimized Signal Peptide and Codon, and Its Impact on Gelatin Properties. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 30, 1082-1091. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Guan, F.; Lv, X.; Han, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, N.; Xia, X.; Tian, J. Enhancing secretion of polyethylene terephthalate hydrolase PETase in Bacillus subtilis WB600 mediated by the SP(amy) signal peptide. Lett Appl Microbiol 2020, 71, 235-241. [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.M.; Cai, X.; Huang, Z.H.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zheng, Y.G. Construction of a highly active secretory expression system in Bacillus subtilis of a recombinant amidase by promoter and signal peptide engineering. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 143, 833-841. [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, J.; Drewniok, C.; Neugebauer, E.; Kellner, H.; Wiegert, T. The YoaW signal peptide directs efficient secretion of different heterologous proteins fused to a StrepII-SUMO tag in Bacillus subtilis. Microb Cell Fact 2019, 18, 31. [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Choi, J.; Cottrell, K.A.; Lavagnino, Z.; Thomas, E.N.; Pavlovic-Djuranovic, S.; Szczesny, P.; Piston, D.W.; Zaher, H.S.; Puglisi, J.D.; et al. A short translational ramp determines the efficiency of protein synthesis. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5774. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Z.; You, C.; Zhang, Y.H. Transformation of Bacillus subtilis. Methods Mol Biol 2014, 1151, 95-101. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, J.; Tan, M.; Fu, X.; Shu, W.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; Xu, J.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, H.; Song, H. High-level extracellular production of an alkaline pectate lyase in E. coli BL21 (DE3) and its application in bioscouring of cotton fabric. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 49. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhen, J.; Shu, W.; Yang, S.; Xu, J.; Song, H.; Ma, Y. Multiplex genetic engineering improves endogenous expression of mesophilic alpha-amylase gene in a wild strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 205. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 165, 609-618. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, F. Reducing the cell lysis to enhance yield of acid-stable alpha amylase by deletion of multiple peptidoglycan hydrolase-related genes in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 167, 777-786. [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.; Lv, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Liu, L. The elucidation of phosphosugar stress response in Bacillus subtilis guides strain engineering for high N-acetylglucosamine production. Biotechnol Bioeng 2020. [CrossRef]

| Signal Peptide | Nucleotide Sequence | Amino Acid Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| LipA | ATGAAATTTGTGAAACGCAGAATTATTGCGCTGGTGACAATTCTGATGCTGAGCGTGACAAGCCTGTTTGCGCTGCAACCGAGCGCGAAAGCG | MKFVKRRIIALVTILMLSVTSLFALQPSAKA |

| YncM | ATGGCTAAACCGCTGTCAAAAGGCGGCATTCTGGTTAAAAAAGTTCTGATTGCAGGCGCAGTTGGCACAGCAGTCCTGTTTGGCACGCTGAGTAGCGGCATTCCGGGACTGCCAGCAGCTGATGCG | MAKPLSKGGILVKKVLIAGAVGTAVLFGTLSSGIPGLPAADA |

| WapA | ATGAAAAAACGCAAACGCAGAAATTTTAAACGCTTTATTGCGGCGTTTCTGGTTCTGGCGCTGATGATTAGCCTGGTTCCGGCGGATGTGCTGGCG | MKKRKRRNFKRFIAAFLVLALMISLVPADVLA |

| PelB | ATGAAATACCTGCTGCCGACCGCTGCTGCTGGTCTGCTGCTCCTCGCTGCCCAGCCGGCGATGGCC | MKYLLPTAAAGLLLLAAQPAMA |

| AmyX | ATGGTCAGCATCCGCCGCAGCTTCGAAGCGTATGTCGATGACATGAATATCATTACTGTTCTGATTCCTGCTGAACAAAAGGAAATCATGACACCGCCG | MVSIRRSFEAYVDDMNIITVLIPAEQKEIMTPP |

| LipA(YncM N5) | ATGGCTAAACCGCTGCGCAGAATTATTGCGCTGGTGACAATTCTGATGCTGAGCGTGACAAGCCTGTTTGCGCTGCAACCGAGCGCGAAAGCG | MAKPLRRIIALVTILMLSVTSLFALQPSAKA |

| LipA(YncMN7) | ATGGCTAAACCGCTGTCAAAAATTATTGCGCTGGTGACAATTCTGATGCTGAGCGTGACAAGCCTGTTTGCGCTGCAACCGAGCGCGAAAGCG | MAKPLSKIIALVTILMLSVTSLFALQPSAKA |

| YncM(LipAN5) | ATGAAATTTGTGAAATCAAAAGGCGGCATTCTGGTTAAAAAAGTTCTGATTGCAGGCGCAGTTGGCACAGCAGTCCTGTTTGGCACGCTGAGTAGCGGCATTCCGGGACTGCCAGCAGCTGATGCG | MKFVKSKGGILVKKVLIAGAVGTAVLFGTLSSGIPGLPAADA |

| YncM(LipAN7) | ATGAAATTTGTGAAACGCAGAGGCGGCATTCTGGTTAAAAAAGTTCTGATTGCAGGCGCAGTTGGCACAGCAGTCCTGTTTGGCACGCTGAGTAGCGGCATTCCGGGACTGCCAGCAGCTGATGCG | MKFVKRRGGILVKKVLIAGAVGTAVLFGTLSSGIPGLPAADA |

| AmyX(LipA N5) | ATGAAATTTGTGAAACGCAGCTTCGAAGCGTATGTCGATGACATGAATATCATTACTGTTCTGATTCCTGCTGAACAAAAGGAAATCATGACACCGCCG | MKFVKRSFEAYVDDMNIITVLIPAEQKEIMTPP |

| AmyX(LipA N7) | ATGAAATTTGTGAAACGCAGATTCGAAGCGTATGTCGATGACATGAATATCATTACTGTTCTGATTCCTGCTGAACAAAAGGAAATCATGACACCGCCG | MKFVKRRFEAYVDDMNIITVLIPAEQKEIMTPP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).