Submitted:

23 April 2024

Posted:

26 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

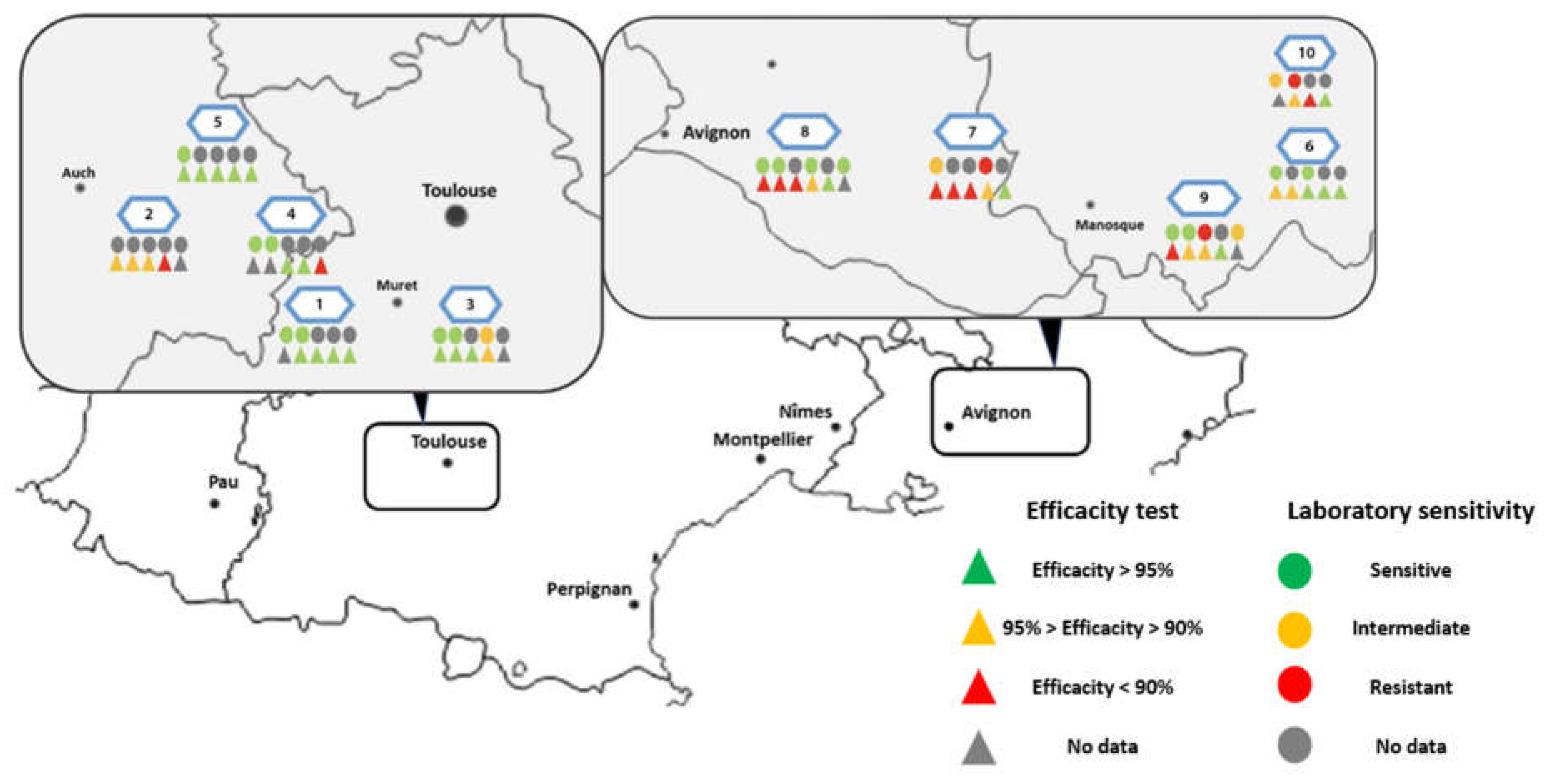

2.1. Apiary Locations

2.2. Laboratory Sensitivity of Varroa Mites Exposed to Amitraz in 2020 and 2021

2.2.1. Determination of Reference LC90 Concentration of Amitraz

- −

- show no signs of other diseases (such as American or European foulbrood, or nosemosis),

- −

- −

- not have a new queen introduced or been merged with colonies that have been treated with amitraz in the past 5 years,

- −

- have sufficient nutritional resources and include frames that have been renewed,

- −

- varroa mites were harvested the same day of reception and 24 hours later by opening each cell capped one by one. For this preliminary study, varroa mites were grouped by apiary, even if they came from different colonies. Only mature varroa females (founding females or young mature females) extracted from capped cells were used for the assay. Ten subjects, or just eight when the quantity was not sufficient, were placed in each capsule. Capsules and Petri dishes were placed in an incubator at 32.5°C, with a relative humidity (RH) of about 70%. After 1 hour, the mites were observed under a magnifying glass binocular, then transferred to a Petri dish with 2 or 3 new larvae/nymphs of worker bees, taken from capped cells from the same brood fragments the varroa mites were harvested from.

- −

- 3 replicates x 10 varroa mites per apiary: 0 ppm 0.5 ppm 1 ppm 2 ppm 3 ppm 5 ppm 7.5 ppm 10 ppm,

- −

- 2 replicates x 10 varroa mites per apiary: 12.5 ppm,

- −

- 1 replicate x 10 varroa mites per apiary: 15 ppm, 20 ppm, 50 ppm, 100 ppm.

- −

- 3 replicates x 8 varroas: 0 ppm 1 ppm 5 ppm 7.5 ppm 10 ppm 12.5 ppm 15 ppm 20 ppm 25 ppm 30 ppm

- −

- 1 replicate x 8 varroas: 40 ppm 50 ppm 100 ppm

2.2.2. Preparation of Paraffin Capsules Coated with Amitraz

2.2.3. Laboratory Exposure of Varroa Mites Towards LC90 Concentration of Amitraz

- −

- mobile mites: when mites could move when put on their paws and after stimuli, if necessary (with the brush),

- −

- paralyzed mites: when mites could move one or more appendages but without being able to move (change location),

- −

- dead mites: when there was no reaction after three stimuli.

2.2.5. Laboratory Assays in 2020 and 2021

2.2.4. Data Analysis

- -

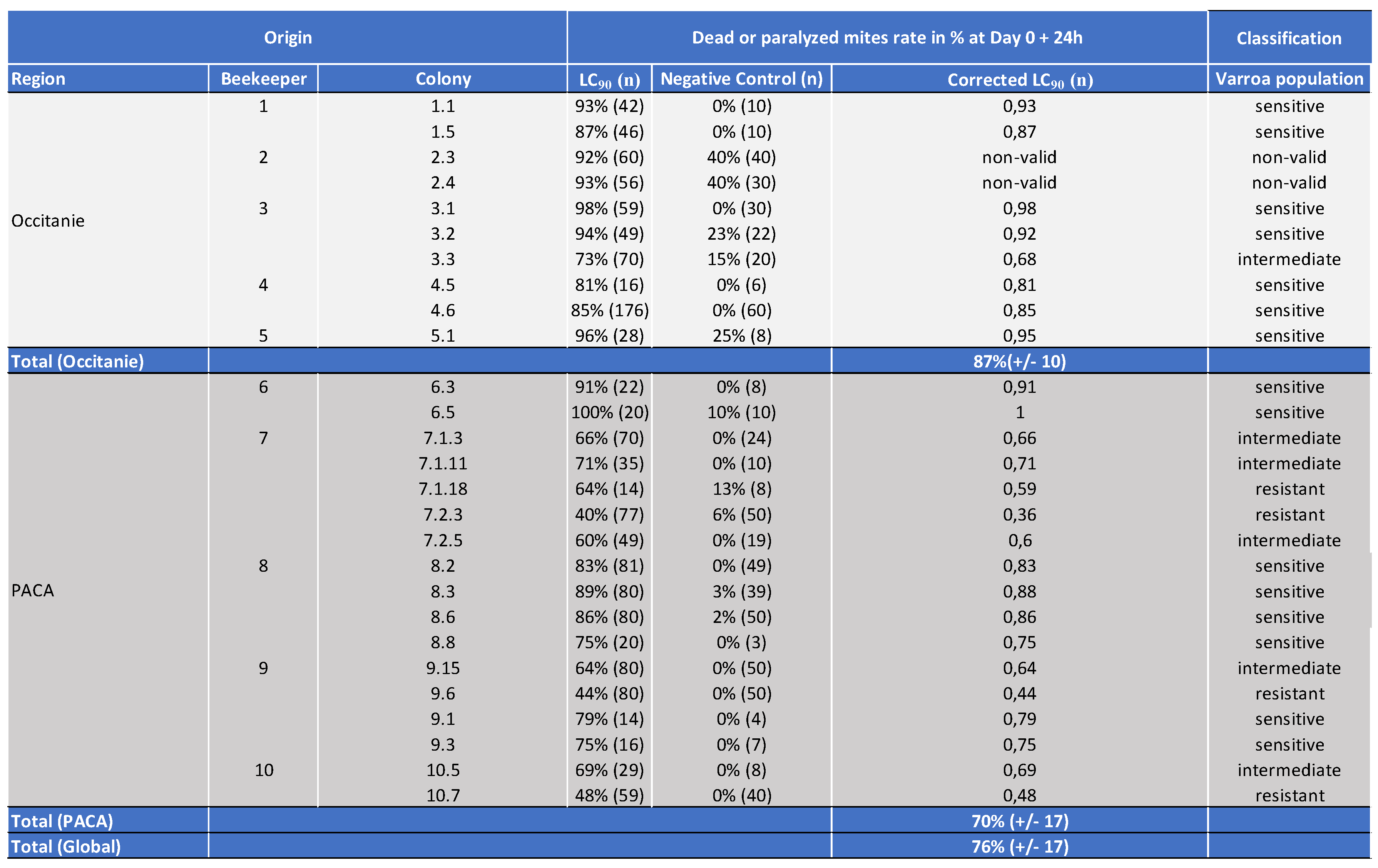

- between 75% and 100%: sensitive population

- -

- between 60% and 75%: intermediate population

- -

- under 60%: resistant population

3. Genotyping of the ORβ-2R-L Gene and Potential Links to Amitraz Resistance

3.1. Genomic DNA Extraction

3.2. Genotyping by Sanger Sequencing

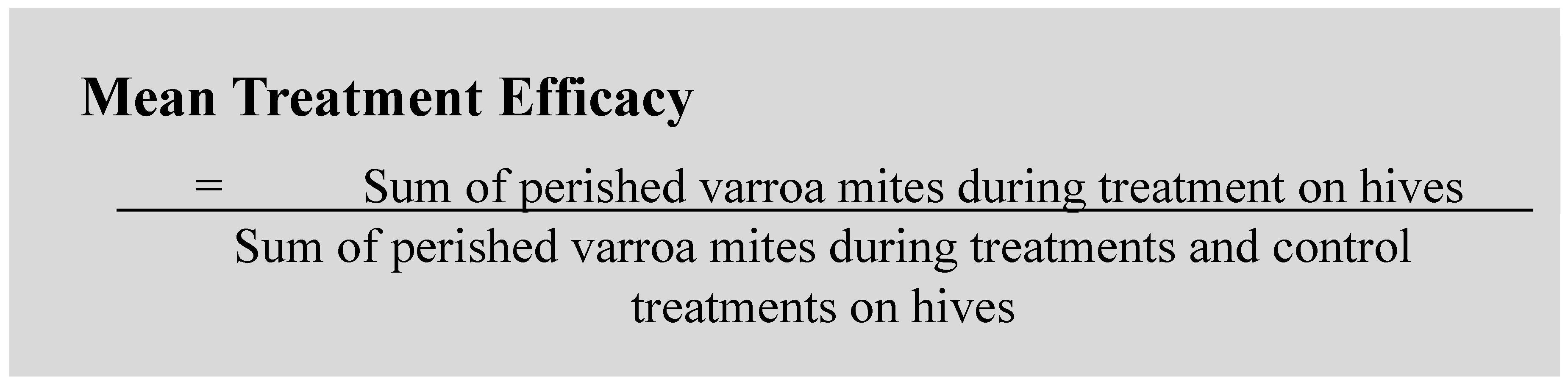

4. Treatment Efficacy of Apivar® in the Field

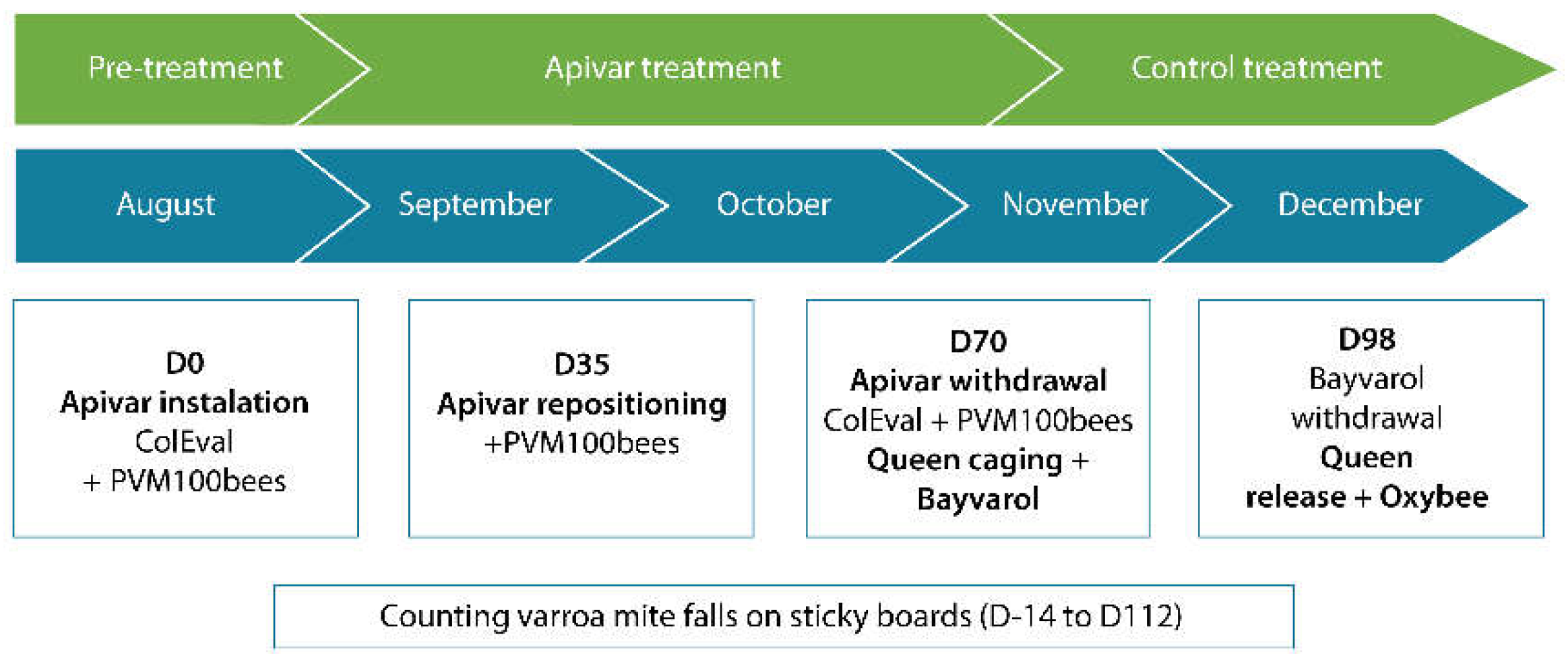

Treatment Efficacy of Apivar® - Protocol 2021 (PACA and Occitanie Region)

5. Results

5.1. Laboratory Sensitivity of Varroa Mites Exposed to Amitraz LC90 and Genotyping of Varroa Mites in 2020

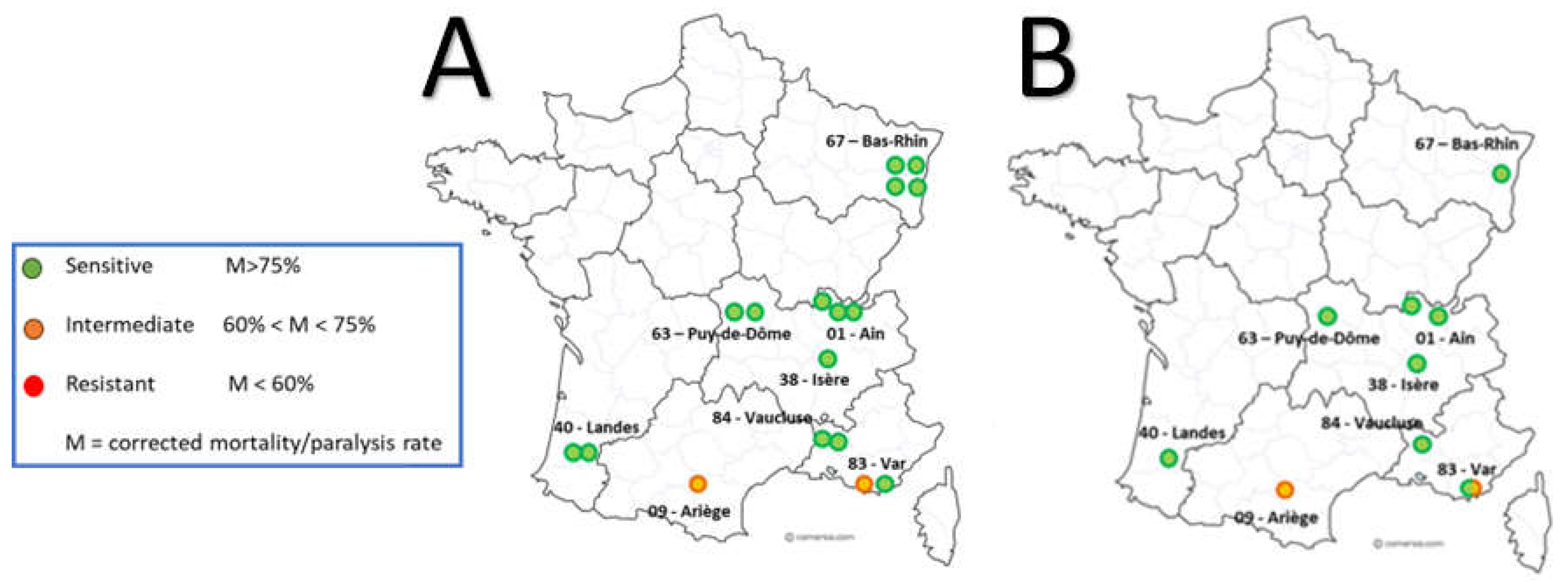

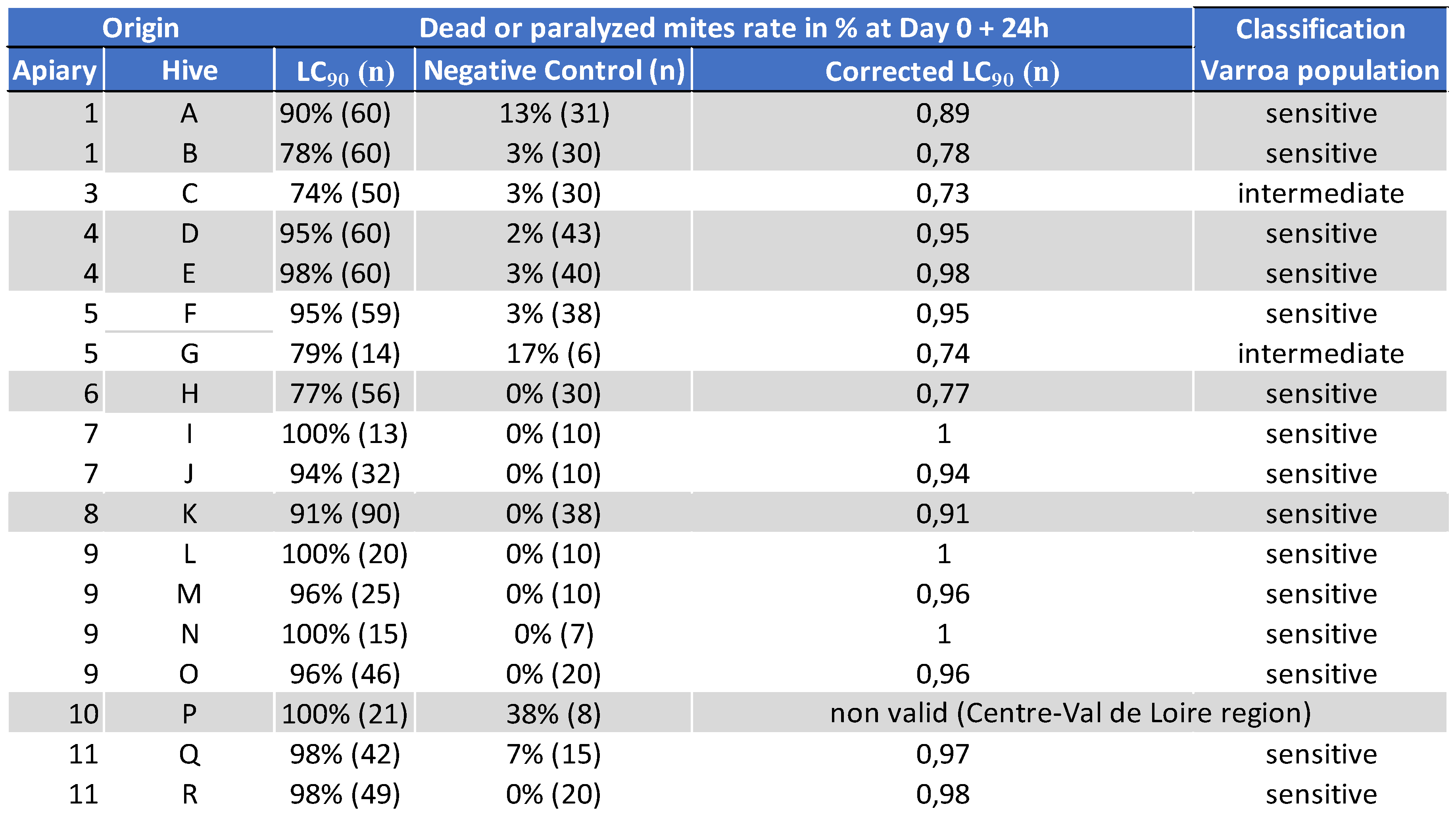

5.1.1. Laboratory Sensitivity of Varroa Mites Towards the LC90 of Amitraz (2020)

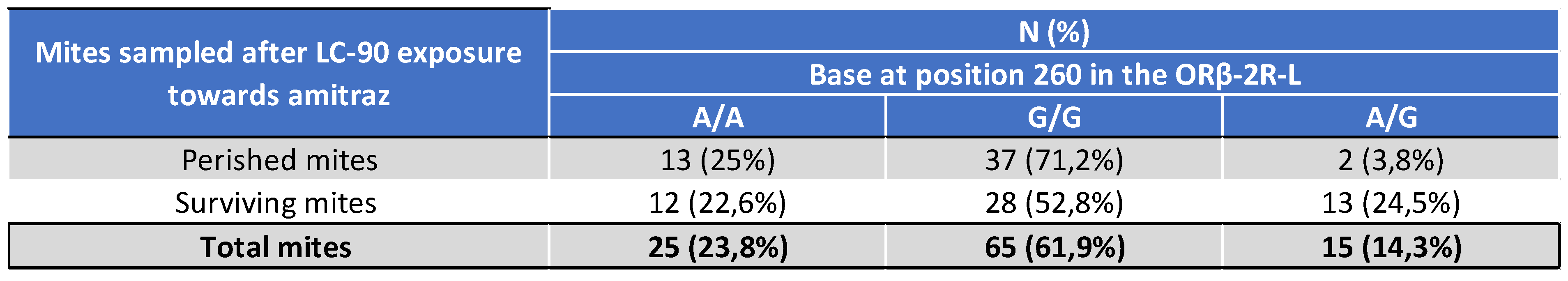

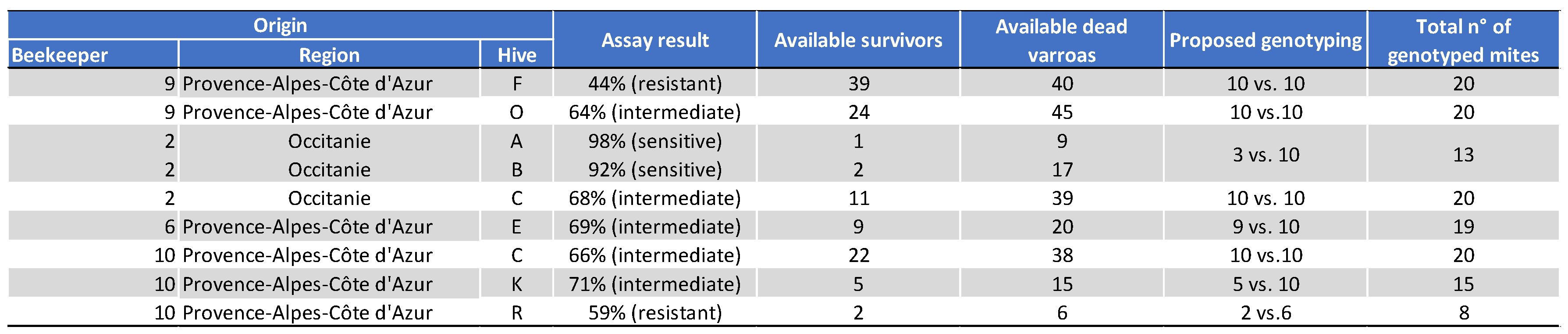

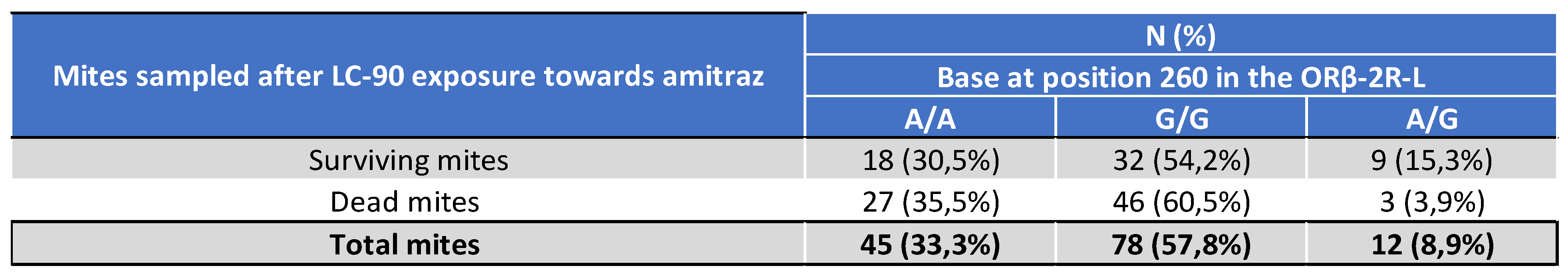

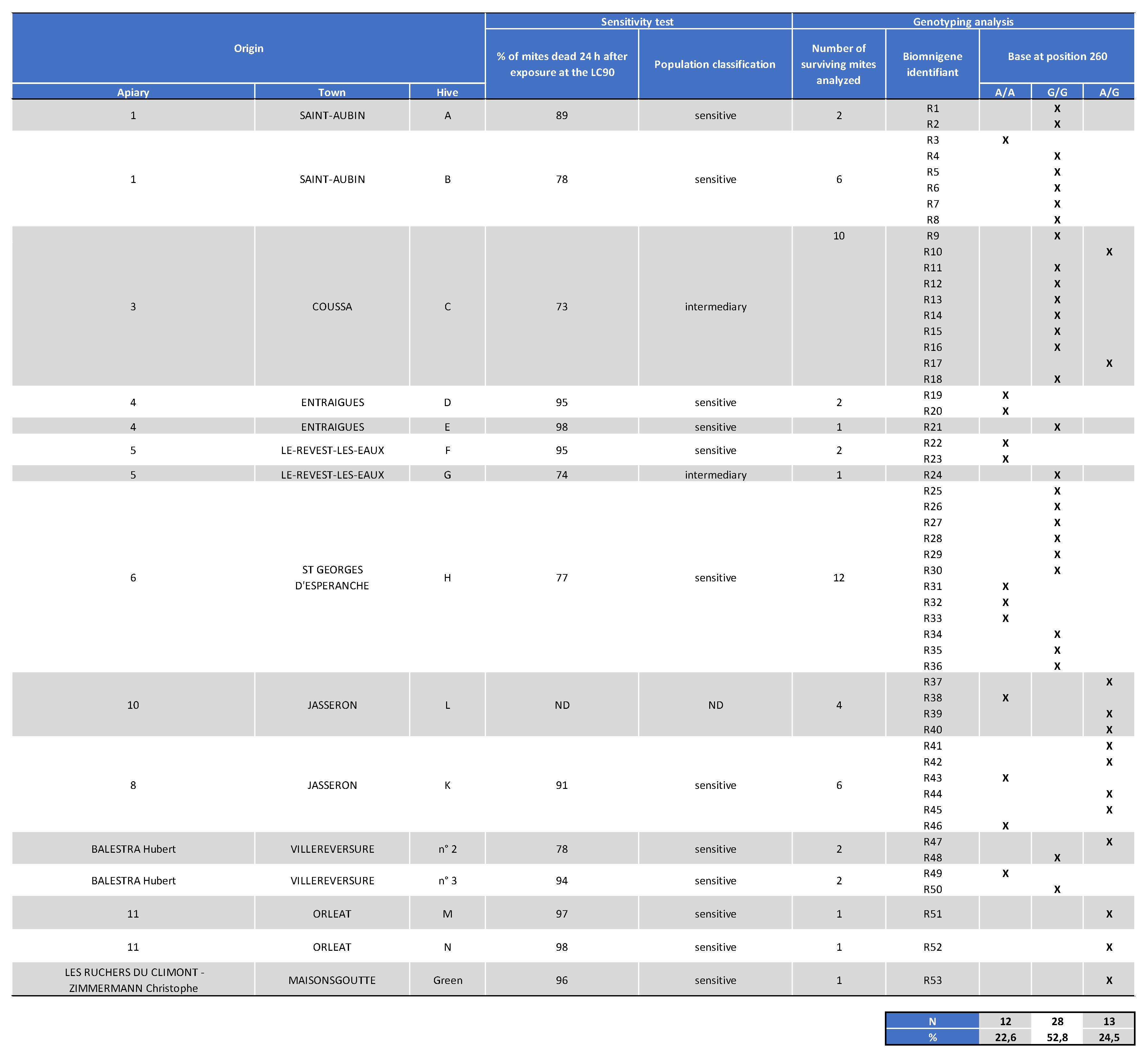

5.1.2. Genotyping of Varroa Mites Previously Tested in the 2020 Laboratory Assay

5.2. Laboratory Sensitivity of Varroa Mites Exposed to Amitraz LC90, Treatment Efficacy of Apivar® in the Field, and Genotyping of Varroa Mites in 2021

5.2.1. Laboratory Sensitivity of Varroa Mites Towards the LC90 of Amitraz (2021)

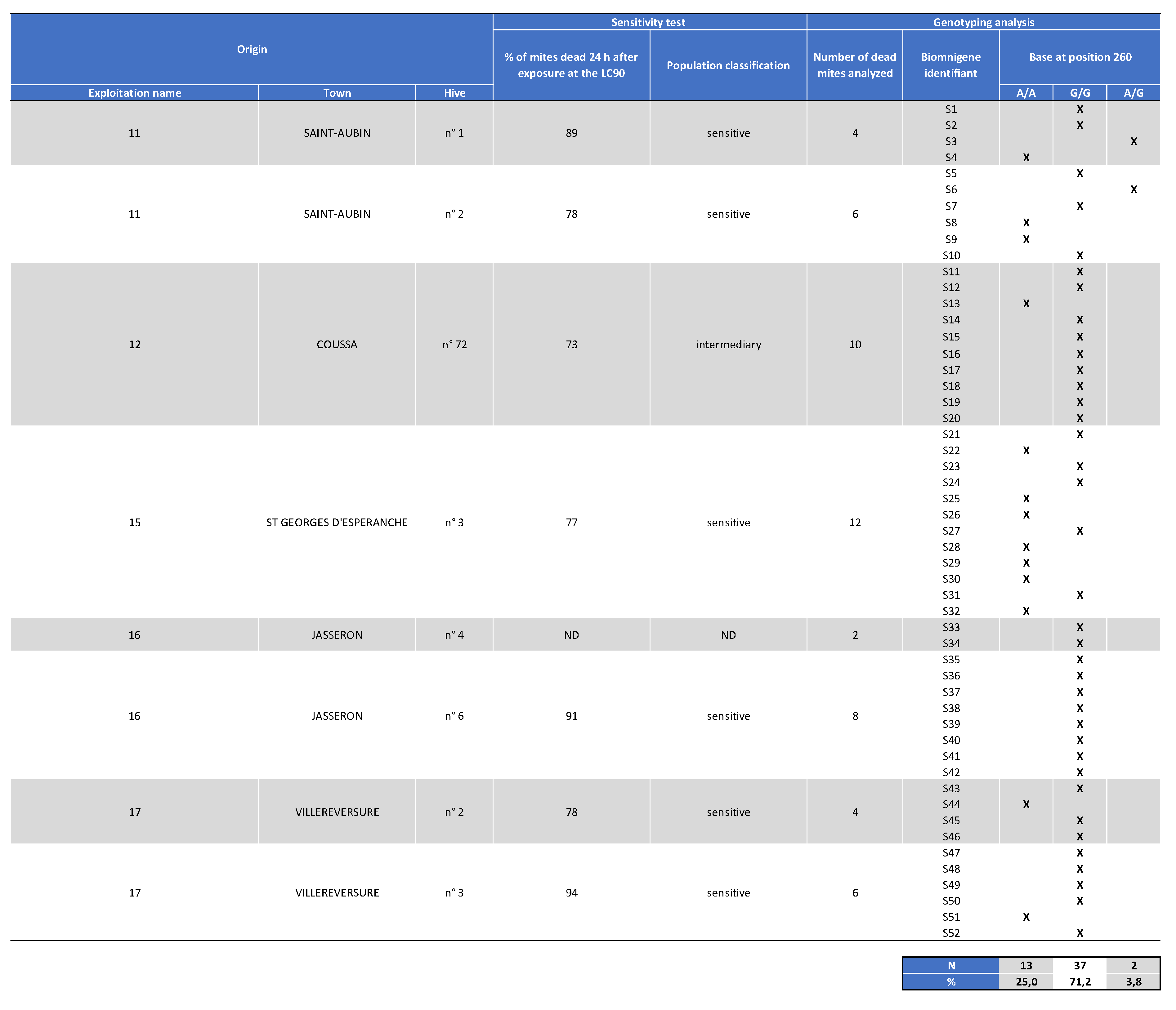

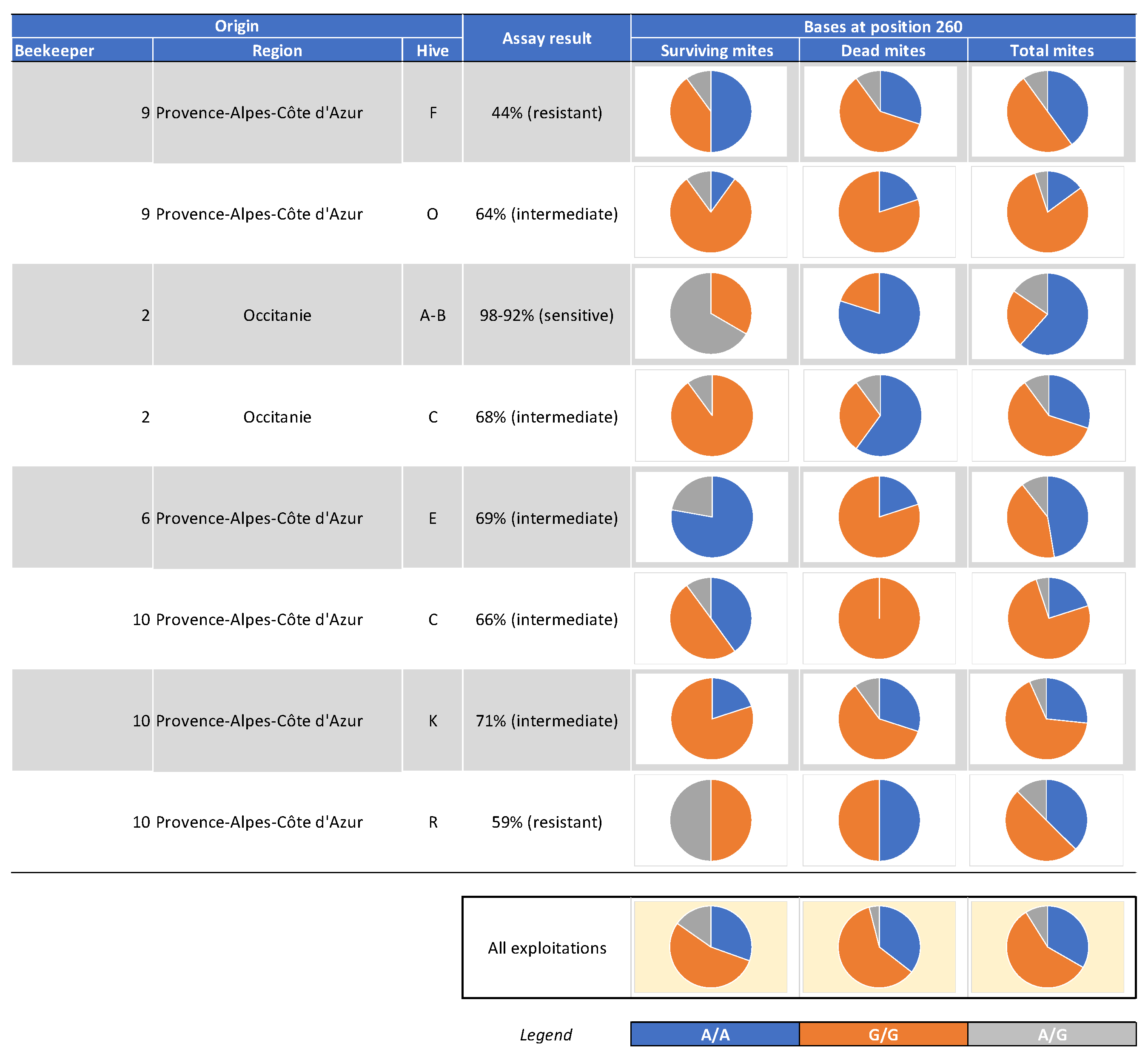

5.2.2. Genotyping of Varroa Mites Previously Tested in the 2021 Laboratory Assay

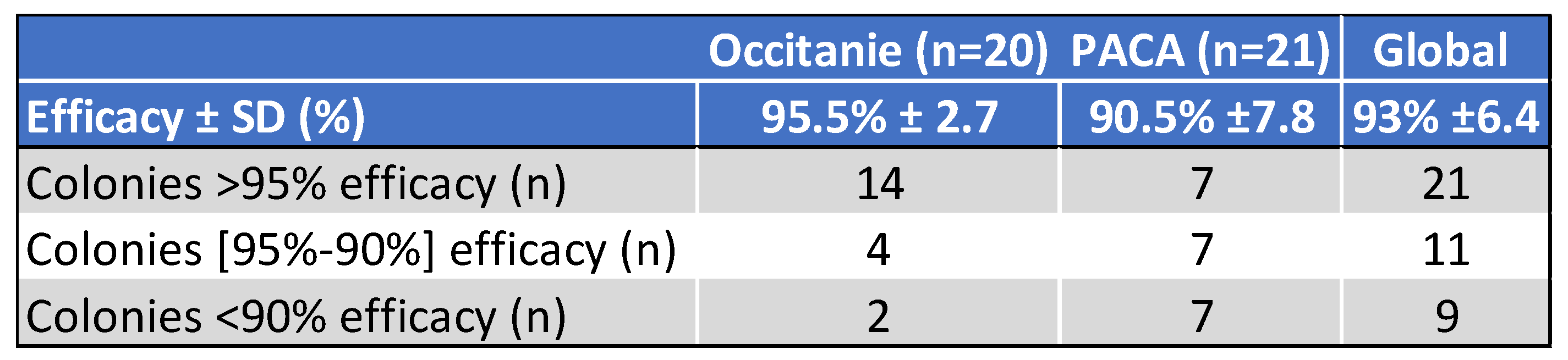

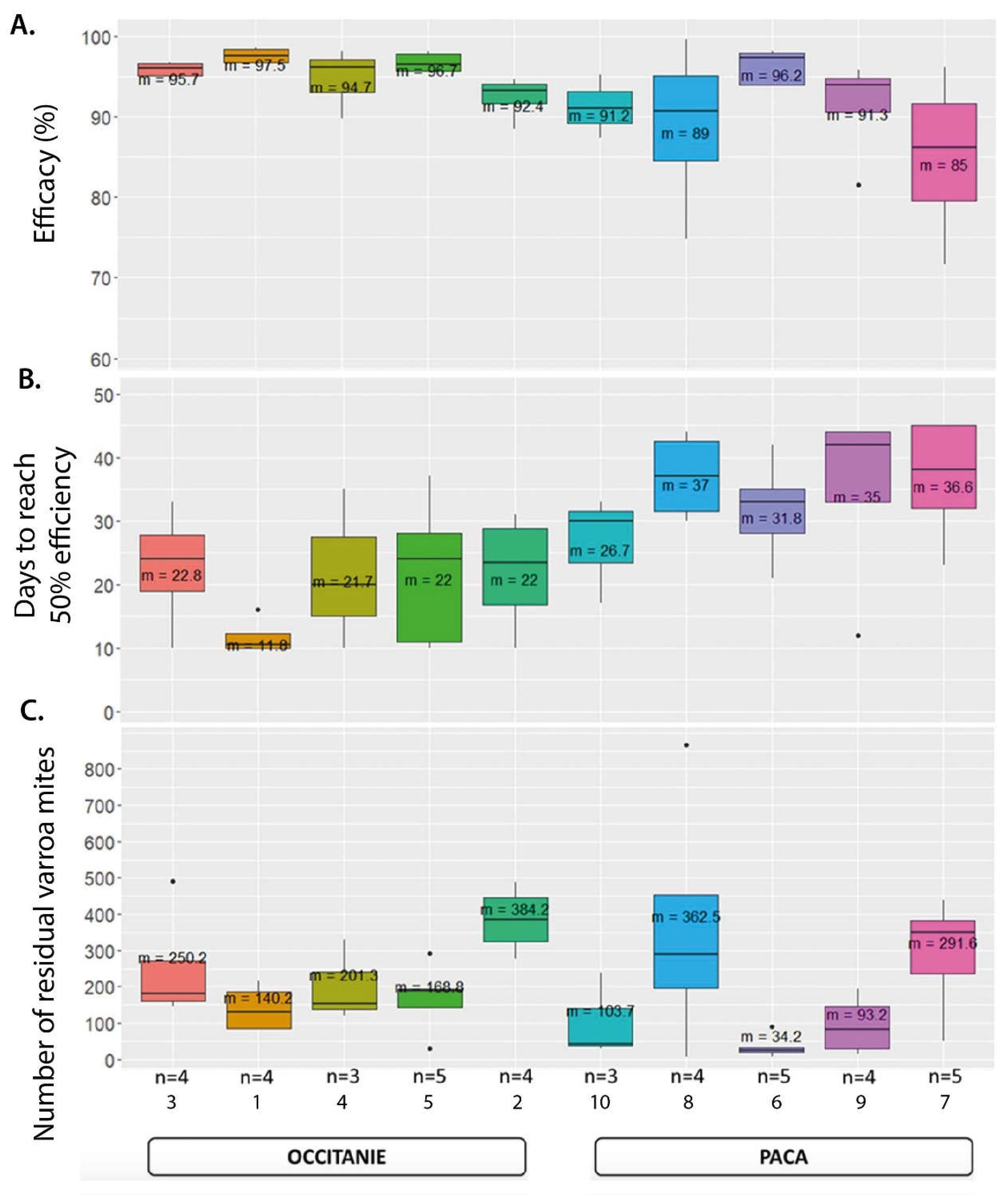

5.2.3. Treatment Efficacy of Apivar® (2021) in the Occitanie and PACA Regions

6. Discussion

6.1. Geographic Distribution and Spread and Magnitude of Amitraz Resistance Detected the Field in French Apiaries

6.2. Genotyping of the ORβ-2R-L Gene and Potential Links to Amitraz Resistance

7. Conclusions

Funding

Authors’ Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

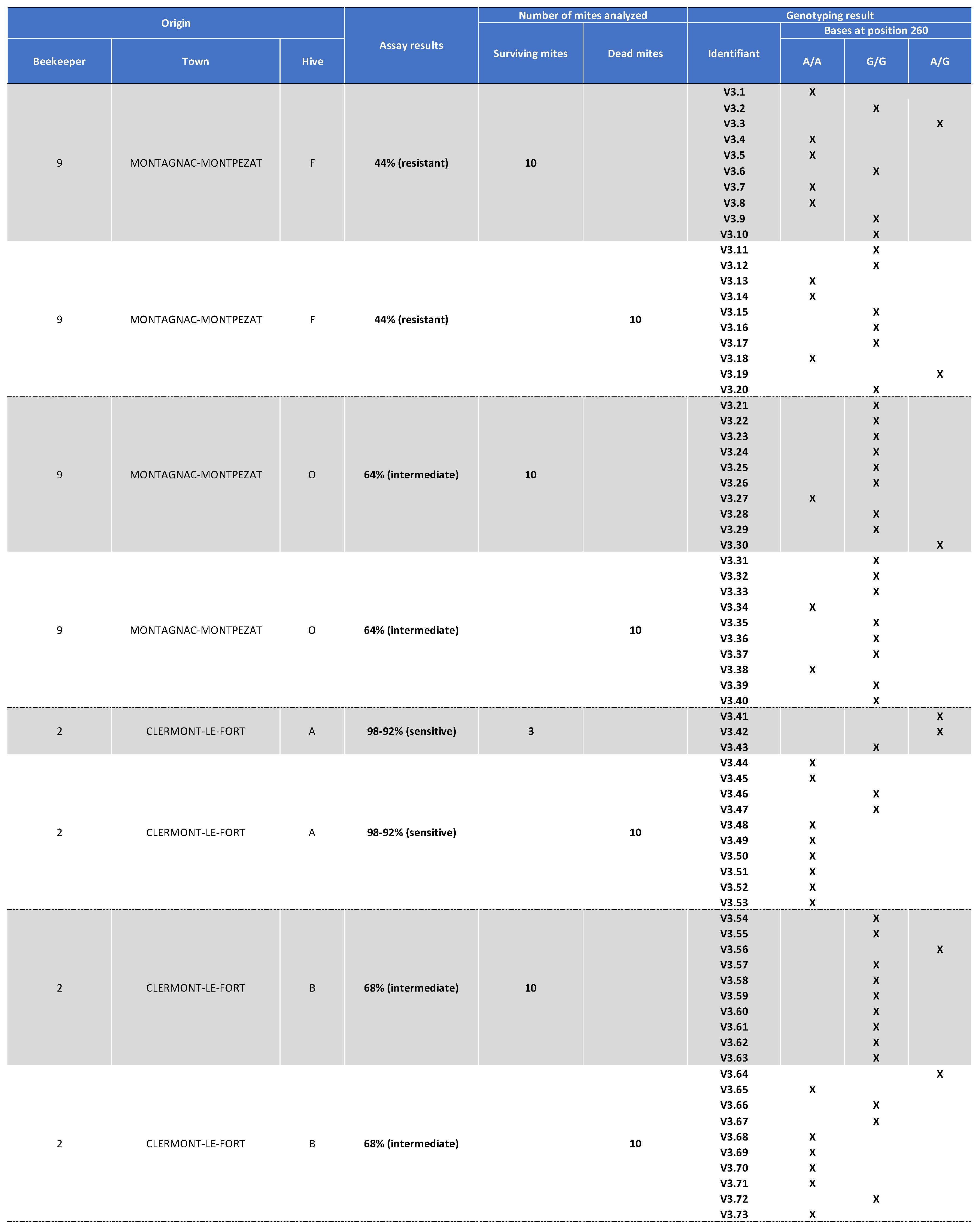

Appendix I. Table Showing the Mites’ Origin, Classification After the Laboratory Assay (Sensitive, Intermediate, or Resistant) as well as Genotyping Results for Varroa Surviving Mite Samples Collected in 2020.

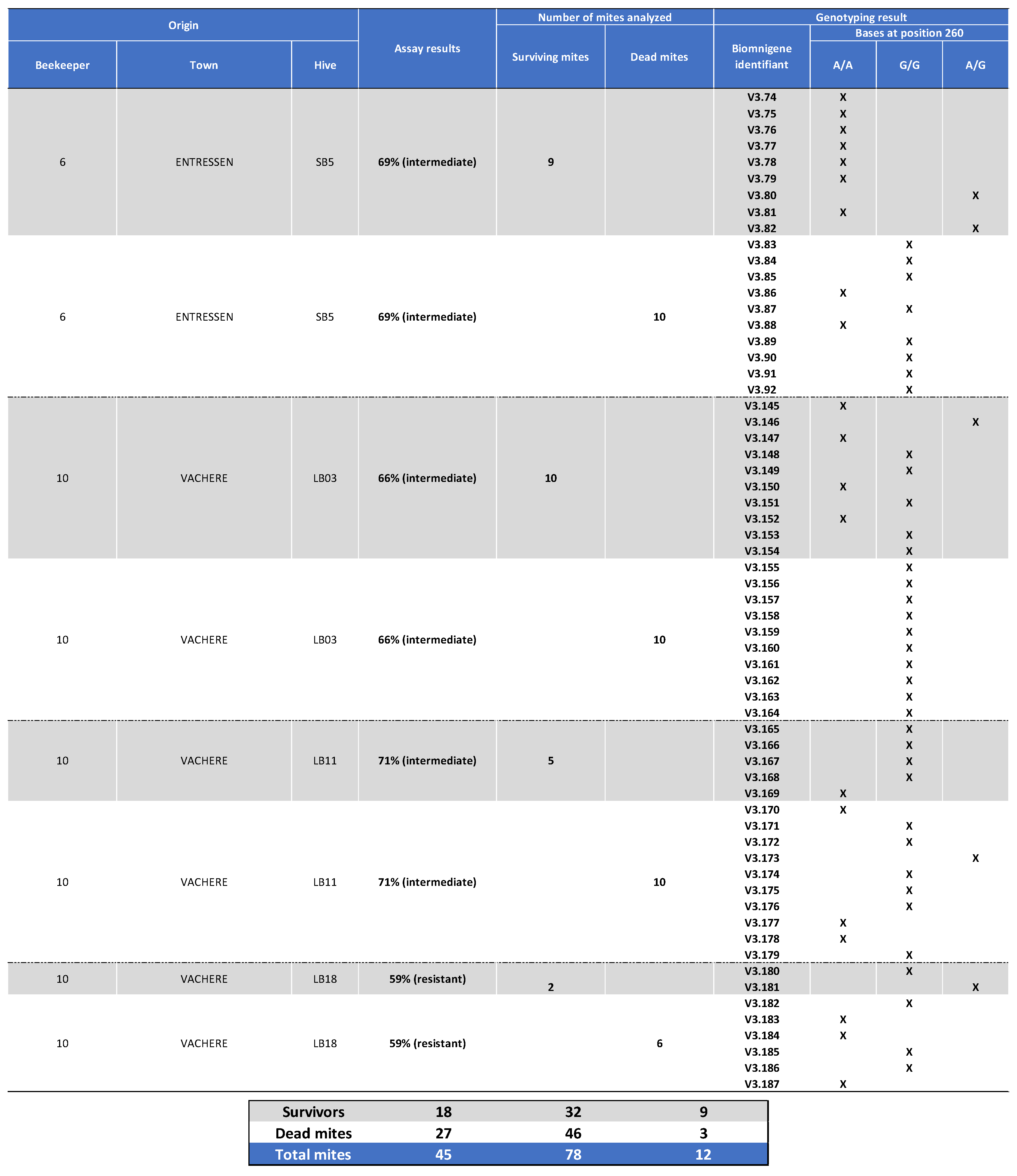

Appendix II. Table Showing the Mites Origin, Classification after the Laboratory Assay (Sensitive, Intermediate, or Resistant) as well as Genotyping Results for Varroa Dead Mite Samples Collected in 2020.

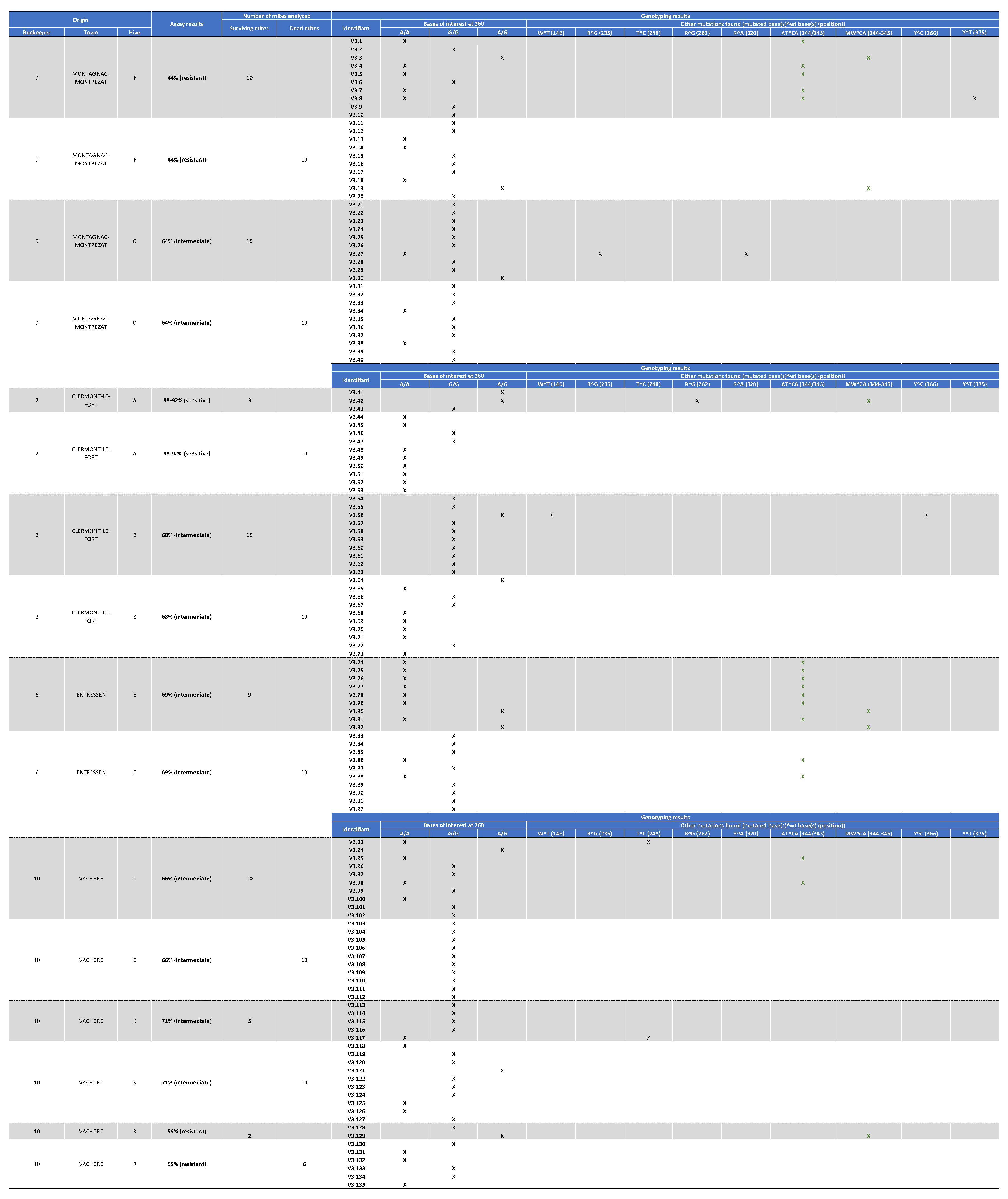

Appendix III. Table Showing the mites’ Origin, Classification after the Laboratory Assay (Sensitive, Intermediate, or Resistant) as well as Genotyping Results for Varroa Mite Samples Collected in 2021.

Appendix IV. Table Reporting the Nature and Positions of the Variations Found in the 135 Sequenced Samples in 2021.

References

- Mondet F, Parejo M, Meixner MD, Costa C, Kryger P, Andonov S, Servin B, Basso B, Bieńkowska M, Bigio G, Căuia E, Cebotari V, Dahle B, Dražić MM, Hatjina F, Kovačić M, Kretavicius J, Lima AS, Panasiuk B, Pinto MA, Uzunov A, Wilde J, Büchler R. Evaluation of Suppressed Mite Reproduction (SMR) Reveals Potential for Varroa Resistance in European Honey Bees (Apis mellifera L.). Insects. 2020 Sep 3;11(9):595. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Engelsdorp D, Hayes J Jr, Underwood RM, Pettis J. A survey of honey bee colony losses in the U.S., fall 2007 to spring 2008. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e4071. Epub 2008 Dec 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahlmann-Brown, P.; Hall, R.J.; Pragert, H.; Robertson, T. Varroa Appears to Drive Persistent Increases in New Zealand Colony Losses. Insects 2022, 13, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutinelli F, Pinto A, Barzon L, Toson M. Some Considerations about Winter Colony Losses in Italy According to the Coloss Questionnaire. Insects. 2022 Nov 16;13(11):1059. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, Rodney & Conflitti, Ida & Labuschagne, Renata & Hoover, Shelley & Currie, Rob & Giovenazzo, Pierre & Guarna, M. & Pernal, Stephen & Foster, Leonard & Zayed, Amro. (2023). Land use changes associated with declining honey bee health across temperate North America. Environmental Research Letters. 18. [CrossRef]

- Smoliński S, Langowska A, Glazaczow A. Raised seasonal temperatures reinforce autumn Varroa destructor infestation in honey bee colonies. Sci Rep. 2021 Nov 15;11(1):22256. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack CJ, de Bem Oliveira I, Kimmel CB and Ellis JD (2023) Seasonal differences in Varroa destructor population growth in western honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11:1102457. [CrossRef]

- Rose A. McGruddy, Mariana Bulgarella, Antoine Felden, James W. Baty, John Haywood, Philip Stahlmann-Brown, Philip J. Lester. Are increasing honey bee colony losses attributed to Varroa destructor in New Zealand driven by miticide resistance? 2023. bioRxiv. 2023.03.22.533871. [CrossRef]

- Posada-Florez, F., Lamas, Z.S., Hawthorne, D.J. Ryabov, Eugene V.. Pupal cannibalism by worker honey bees contributes to the spread of deformed wing virus. Sci Rep 11, 8989 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Mitton, Giulia & Meroi Arcerito, Facundo & Cooley, Hazel & Fernandez de Landa, Gregorio & Eguaras, Martín & Ruffinengo, Sergio & Maggi, Matías. (2022). More than sixty years living with Varroa destructor: a review of acaricide resistance. International Journal of Pest Management. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Lodesani, Marco, Mauro Colombo, and M. Spreafico. “Ineffectiveness of Apistan® treatment against the mite Varroa jacobsoni Oud in several districts of Lombardy (Italy).” Apidologie 26.1 (1995): 67-72. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Reed M., Henry S. Pollock, and May R. Berenbaum. “Synergistic interactionsbetween in-hive miticides in Apis mellifera.” Journal of economic entomology 102.2 (2009): 474-479.

- Patti J. Elzen, Frank A. Eischen, James R. Baxter, Gary W. Elzen, William T. Wilson. “Detection of resistance in US Varroa jacobsoni Oud.(Mesostigmata: Varroidae) to the acaricide fluvalinate.” Apidologie 30.1 (1999): 13-17. [CrossRef]

- Trouiller, Jérôme. “Monitoring Varroa jacobsoni resistance to pyrethroids in western Europe.” Apidologie 29.6 (1998): 537-546.

- Helen M. Thompson, Michael A. Brown, Richard F. Ball, Medwin H. Bew. “First report of Varroa destructor resistance to pyrethroids in the UK.” Apidologie 33.4 (2002) : 357-366. [CrossRef]

- Mitton, G. A., Quintana, S., Giménez Martínez, P., Mendoza, Y., Ramallo, G., Brasesco, C., Villalba, A., Eguaras, M. J., Maggi, M. D., Ruffinengo, S. R. (2016). First record of resistance to flumethrin in a varroa population from Uruguay. Journal of Apicultural Research, 55(5), 422–427. [CrossRef]

- González-Cabrera J, Davies TG, Field LM, Kennedy PJ, Williamson MS. An amino acid substitution (L925V) associated with resistance to pyrethroids in Varroa destructor. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 18;8(12):e82941. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Cabrera J, Rodríguez-Vargas S, Davies TG, Field LM, Schmehl D, Ellis JD, Krieger K, Williamson MS. Novel Mutations in the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel of Pyrethroid-Resistant Varroa destructor Populations from the Southeastern USA. PLoS One. 2016 May 18;11(5):e0155332. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán-Leiva A, Marín Ó, Christmon K, vanEngelsdorp D, González-Cabrera J. Mutations associated with pyrethroid resistance in Varroa mite, a parasite of honey bees, are widespread across the United States. Pest Manag Sci. 2021 Jul;77(7):3241-3249. Epub 2021 Apr 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semkiw, Piotr & Skubida, Piotr & Pohorecka, Krystyna. (2013). The Amitraz Strips Efficacy in Control of Varroa Destructor After Many Years Application of Amitraz in Apiaries. Journal of Apicultural Science. 57. 107-121. [CrossRef]

- Higes M, Martín-Hernández R, Hernández-Rodríguez CS, González-Cabrera J. Assessing the resistance to acaricides in Varroa destructor from several Spanish locations. Parasitol Res. 2020 Nov;119(11):3595-3601. Epub 2020 Sep 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almecija G, Poirot B, Cochard P, Suppo C. Inventory of Varroa destructor susceptibility to amitraz and tau-fluvalinate in France. Exp Appl Acarol. 2020 Sep;82(1):1-16. Epub 2020 Aug 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinkevich, Frank D. “Detection of amitraz resistance and reduced treatment efficacy in the Varroa Mite, Varroa destructor, within commercial beekeeping operations.” PloS one 15.1 (2020): e0227264.

- Hernández-Rodríguez, C.S., Moreno-Martí, S., Almecija, G., Christmon K., Johnson, J. D., Ventelon, M., vanEngelsdorp, D., Cook, S. C., González-Cabrera, J., Resistance to amitraz in the parasitic honey bee mite Varroa destructor is associated with mutations in the β-adrenergic-like octopamine receptor. J Pest Sci 95, 1179–1195 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Pettis, J. S., H. Shimanuki, and M. F. Feldlaufer. “Detection of varroa resistant to fluvalinate.” Vida Apicola (España) (1999).

- Almecija, Gabrielle. “Résistances de Varroa destructor aux acaricides : conséquences sur l’efficacité des traitements. Application au tau-fluvalinate et à l’amitraze.” (2021).

- Morfin, N., Rawn, D., Petukhova, T., Kozak, P., Eccles, L., Chaput, J., Pasma, T., and Guzman-Novoa, E. 2022. Surveillance of synthetic acaricide efficacy against Varroa destructor in Ontario, Canada. The Canadian Entomologist. [CrossRef]

- Milani, Norberto & Vedova, Giorgio. Decline in the proportion of mites resistant to fluvalinate in a population of Varroa destructor not treated with pyrethroids. (2002). Apidologie 33(4):417-422.

- Elzen, Patti & Westervelt, David. A scientific note on reversion of fluvalinate resistance to a degree of susceptibility in Varroa destructor. (2004). Apidologie 35(5):519-520.

- Dietemann, V; Ellis, J D; Neumann, P. EDS. The COLOSS BEEBOOK, Volume I: standard methods for Apis mellifera research. International Bee Research Association; Cardiff, UK. 636 pp. ISBN 978-0-86098-274-6 (2013).

- Milani, N. The resistance of Varroa jacobsoni Oud. To pyrethroids – a laboratory assay. Apidologie 26 : 415–429 (1995).

- Sandon Y., Viry, A. Lutte contre le Varroa – Etude de sensibilité/résistance à l’amitraze chez Varroa destructor – La Santé de l’Abeille N°277: 47-56 (2017).

- Giles, David P., Rothwell David N. The sub-lethal activity of amidines on insects and acarids. Pesticide Science 14, (3), 303–312 (1983).

- Evans P.D., Gee J.D. Action of formamidine pesticides on octopamine receptors. Nature 1980; 287 (5777): 60-62. [CrossRef]

- Alban Maisonnasse, J. Hernandez, C. Le Quintec, Marianne Cousin, Constance Beri, et al. Evaluation de la structure des colonies d’abeilles, création et utilisation de la méthode ColEval (Colony Evaluation). Innovations Agronomiques, 2016, 53, pp.27-37.

- Observatoire de la production de miel et de gelée royale - Edition juillet 2022 © FranceAgriMer 2022.

- Guideline on veterinary medicinal products controlling Varroa destructor parasitosis in bees EMA/CVMP/EWP/459883/2008-Rev.1.

- Rapport d’étude Evaluation de l’efficacité du traitement Apivar® en lien avec la sensibilité des populations de varroas à l’amitraze (2021). (Microsoft Word - Rapport_EfficacitéApivar2021_v04082022 (adaoccitanie.org)).

- Rosenkranz P, Aumeier P, Ziegelmann B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010; 103:S96–S119. [PubMed: 19909970].

- Oldroyd, B. P. 1999. Coevolution while you wait: Varroa jacobsoni, a new parasite of western honeybees. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14: 312–315.

- Ayan, A., O. S. Aldemır, and Z. Selamoglu. 2017. Analysis of COI gene region of Varroa destructor in honey bees (Apis mellifera) in province of Siirt. Turkish J. Vet. Res. 1: 20–23.

- Hajializadeh, Z., M. Asadi, and H. Kavousi. 2018. First report of Varroa genotype in western Asia based on genotype identification of Iranian Varroa destructor populations (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) using RAPD marker. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 23: 199–205.

- Ogihara, M. H., M. Yoshiyama, N. Morimoto, and K. Kimura. 2020. Dominant honeybee colony infestation by Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) K haplotype in Japan. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 55: 189–197.

- Navajas, M., D. L. Anderson, L. I. De Guzman, Z. Y. Huang, J. Clement, T. Zhou, and Y. Le Conte. 2010. New Asian types of Varroa destructor: a potential new threat for world apiculture. Apidologie. 41: 181–193.

- Techer, M. A., J. M. K. Roberts, R. A. Cartwright, and A. S. Mikheyev. 2021. The first steps toward a global pandemic: Reconstructing the demographic history of parasite host switches in its native range. Mol Ecol. [CrossRef]

- Dynes TL, et al. Fine scale population genetic structure of Varroa destructor, an ectoparasitic mite of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) Apidologie. 2017;48:93–101. [CrossRef]

- Beaurepaire A.L., Moro A., Mondet F., Le Conte Y., Neumann P., Locke B. Population genetics of ectoparasitic mites suggest arms race with honeybee hosts. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:11355. [CrossRef]

- Ascunce, M. S., Toups, M. A., Kassu, G., Fane, J., Scholl, K., & Reed, D. L. (2013). Nuclear genetic diversity in human lice (Pediculus humanus) reveals continental differences and high inbreeding among worldwide populations. PLoS One, 8(2), e57619. [CrossRef]

- Nozais J.P. The origin and dispersion of human parasitic diseases in the old world (Africa, Europe and Madagascar) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98(Suppl. I):13–19.

- Dietemann, V. , Beaurepaire, A. , Page, P. , Yañez, O. , Buawangpong, N. , Chantawannakul, P. , & Neumann, P. (2019). Population genetics of ectoparasitic mites Varroa spp. in Eastern and Western honey bees. Parasitology, 146, 1429–1439.

- Techer, M. A., R. V. Rane, M. L. Grau, J. M. K. Roberts, S. T. Sullivan, I. Liachko, A. K. Childers, J. D. Evans, and A. S. Mikheyev. 2019. Divergent evolutionary trajectories following speciation in two ectoparasitic honey bee mites. Commun. Biol. 2: 357.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).