Submitted:

24 April 2024

Posted:

25 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

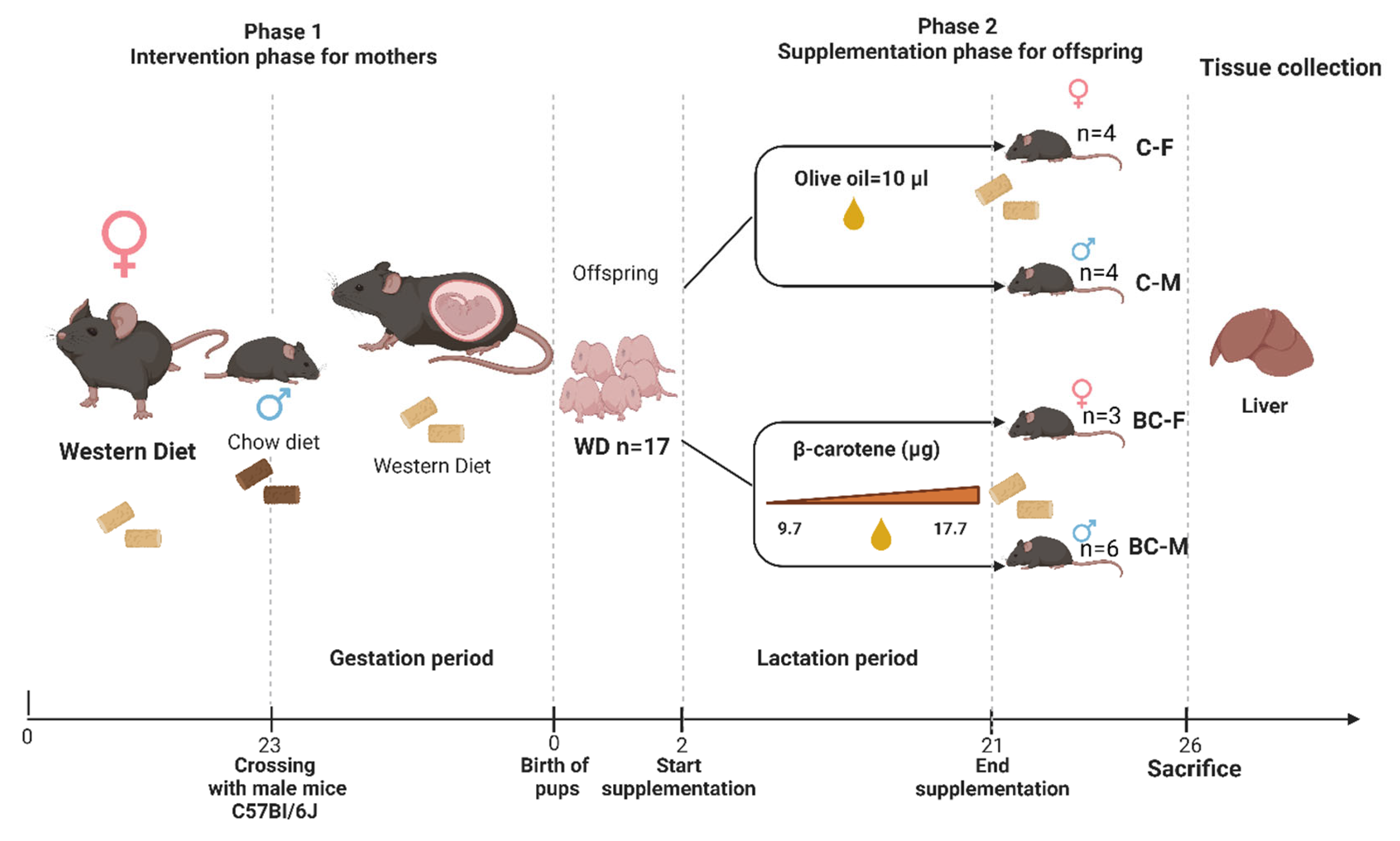

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. RNA Isolation and Quantification

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biometric Parameters

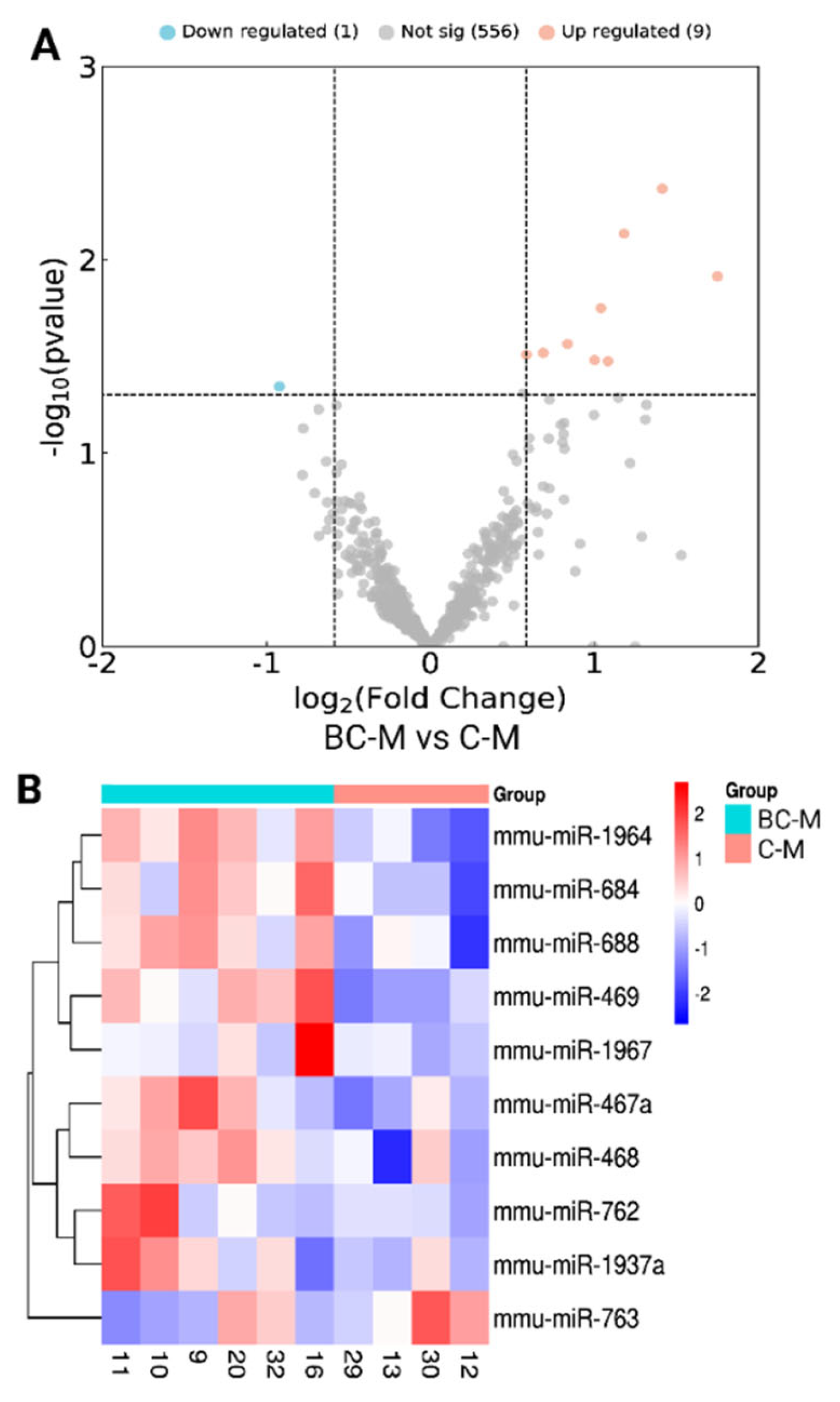

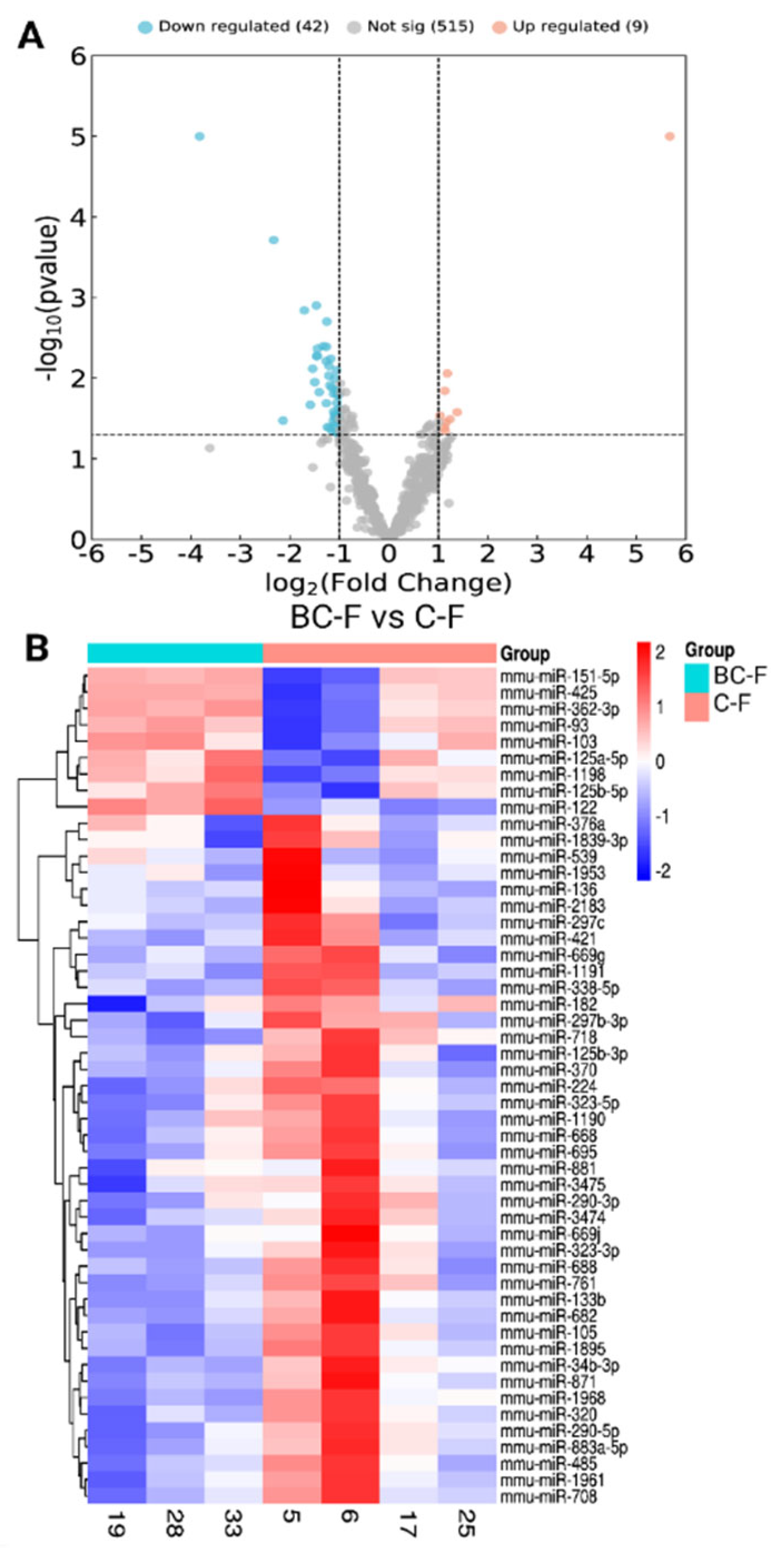

3.2. Nanostring Analysis of miRNAs and Differentially Expressed miRNAs

| miRNA | Fold change | Regulation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| mmu-miR-763 | -1.893 | Down | 0.0453 |

| mmu-miR-1937a/b | 1.751 | Up | 0.0121 |

| mmu-miR-762 | 1.41458 | Up | 0.004291 |

| mmu-miR-468 | 1.181217 | Up | 0.007326 |

| mmu-miR-1967 | 1.083272 | Up | 0.033513 |

| mmu-miR-469 | 1.040029 | Up | 0.017799 |

| mmu-miR-688 | 1.001268 | Up | 0.033073 |

| mmu-miR-684 | 0.836395 | Up | 0.027278 |

| mmu-miR-1964 | 0.687733 | Up | 0.030326 |

| mmu-miR-467a | 0.585563 | Up | 0.030996 |

| miRNA | Fold change | Regulation | P- value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mmu-miR-1191 | -14.1521 | Down | 3.09E-07 | |||||

| mmu-miR-2183 | -5.01241 | Down | 0.000193 | |||||

| mmu-miR-376a | -4.40317 | Down | 0.033524 | |||||

| mmu-miR-1968 | -3.26993 | Down | 0.001442 | |||||

| mmu-miR-539 | -3.00592 | Down | 0.021402 | |||||

| mmu-miR-136 | -2.90541 | Down | 0.007614 | |||||

| mmu-miR-669g | -2.8221 | Down | 0.011202 | |||||

| mmu-miR-338-5p | -2.76262 | Down | 0.001253 | |||||

| mmu-miR-682 | -2.75437 | Down | 0.005321 | |||||

| mmu-miR-323-5p | -2.72259 | Down | 0.005302 | |||||

| mmu-miR-290-5p | -2.7219 | Down | 0.004294 | |||||

| mmu-miR-182 | -2.65349 | Down | 0.014895 | |||||

| mmu-miR-320 | -2.50812 | Down | 0.004008 | |||||

| mmu-miR-761 | -2.40692 | Down | 0.00612 | |||||

| mmu-miR-871 | -2.40115 | Down | 0.004071 | |||||

| mmu-miR-1839-3p | -2.40041 | Down | 0.020481 | |||||

| mmu-miR-34b-3p | -2.38487 | Down | 0.001983 | |||||

| mmu-miR-881 | -2.36257 | Down | 0.040452 | |||||

| mmu-miR-224 | -2.32138 | Down | 0.009298 | |||||

| mmu-miR-1961 | -2.31858 | Down | 0.007012 | |||||

| mmu-miR-125b-3p | -2.2945 | Down | 0.041596 | |||||

| mmu-miR-297c | -2.28392 | Down | 0.012285 | |||||

| mmu-miR-421 | -2.25396 | Down | 0.005722 | |||||

| mmu-miR-883a-5p | -2.21618 | Down | 0.013146 | |||||

| mmu-miR-3474 | -2.19501 | Down | 0.04617 | |||||

| mmu-miR-3475 | -2.17952 | Down | 0.033841 | |||||

| mmu-miR-297b-3p | -2.16784 | Down | 0.015613 | |||||

| mmu-miR-1953 | -2.16066 | Down | 0.025989 | |||||

| mmu-miR-695 | -2.1502 | Down | 0.039103 | |||||

| mmu-miR-323-3p | -2.13416 | Down | 0.028574 | |||||

| mmu-miR-133b | -2.13306 | Down | 0.010116 | |||||

| mmu-miR-370 | -2.12883 | Down | 0.03029 | |||||

| mmu-miR-1895 | -2.08625 | Down | 0.007972 | |||||

| mmu-miR-688 | -2.07886 | Down | 0.047323 | |||||

| mmu-miR-485 | -2.0763 | Down | 0.014138 | |||||

| mmu-miR-290-3p | -2.07055 | Down | 0.020309 | |||||

| mmu-miR-105 | -2.06476 | Down | 0.015803 | |||||

| mmu-miR-669j | -2.06456 | Down | 0.035964 | |||||

| mmu-miR-1190 | -2.0396 | Down | 0.048281 | |||||

| mmu-miR-708 | -2.03612 | Down | 0.016461 | |||||

| mmu-miR-668 | -2.03022 | Down | 0.029321 | |||||

| mmu-miR-718 | -2.01753 | Down | 0.024074 | |||||

| mmu-miR-122 | 51.125 | Up | 1.74E-25 | |||||

| mmu-miR-103 | 2.598296 | Up | 0.026379 | |||||

| mmu-miR-125b-5p | 2.352268 | Up | 0.032295 | |||||

| mmu-miR-362-3p | 2.265612 | Up | 0.008745 | |||||

| mmu-miR-151-5p | 2.229765 | Up | 0.035369 | |||||

| mmu-miR-125a-5p | 2.19763 | Up | 0.044985 | |||||

| mmu-miR-1198 | 2.186721 | Up | 0.014346 | |||||

| mmu-miR-93 | 2.170918 | Up | 0.041012 | |||||

| mmu-miR-425 | 2.050926 | Up | 0.029188 | |||||

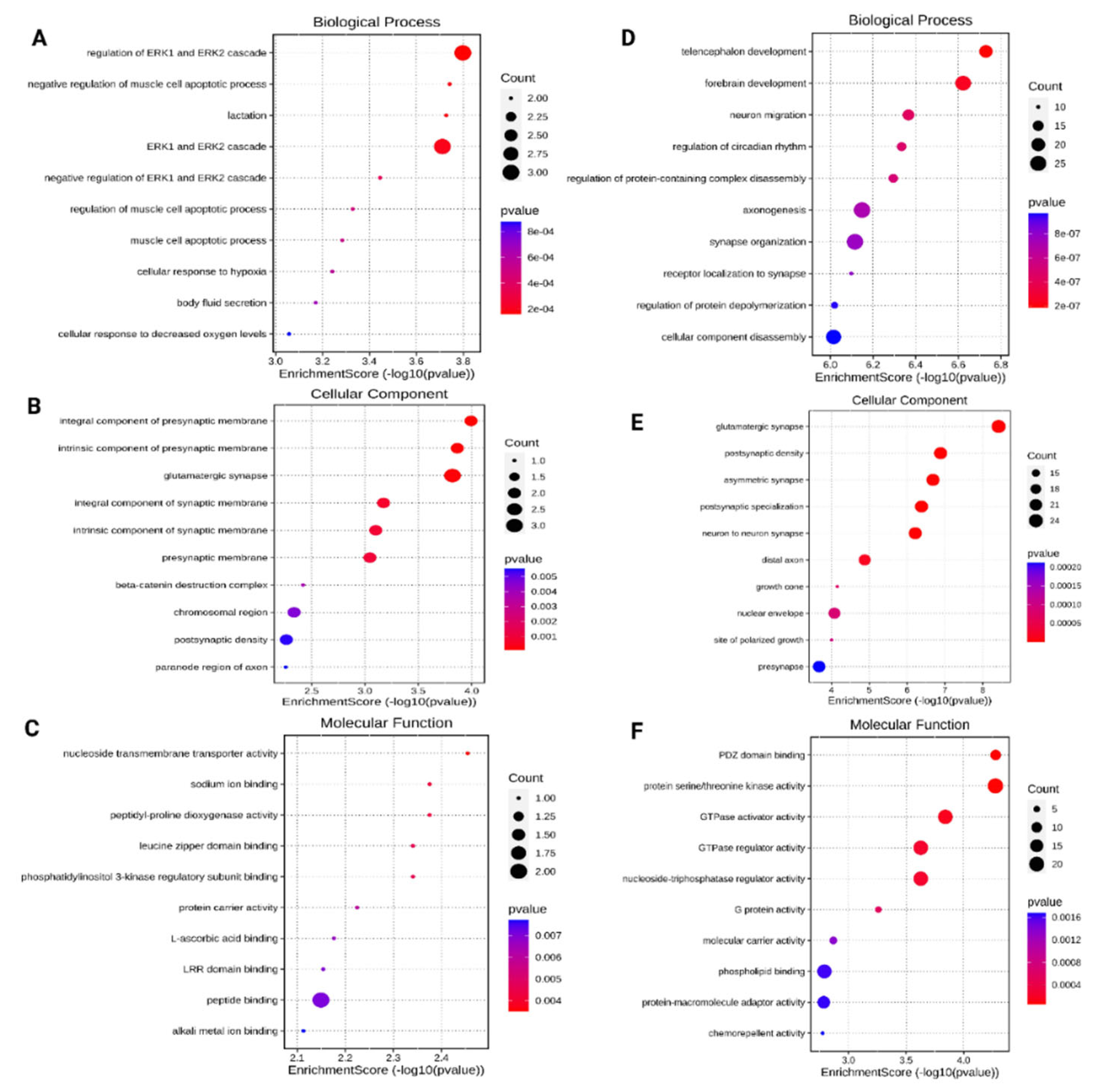

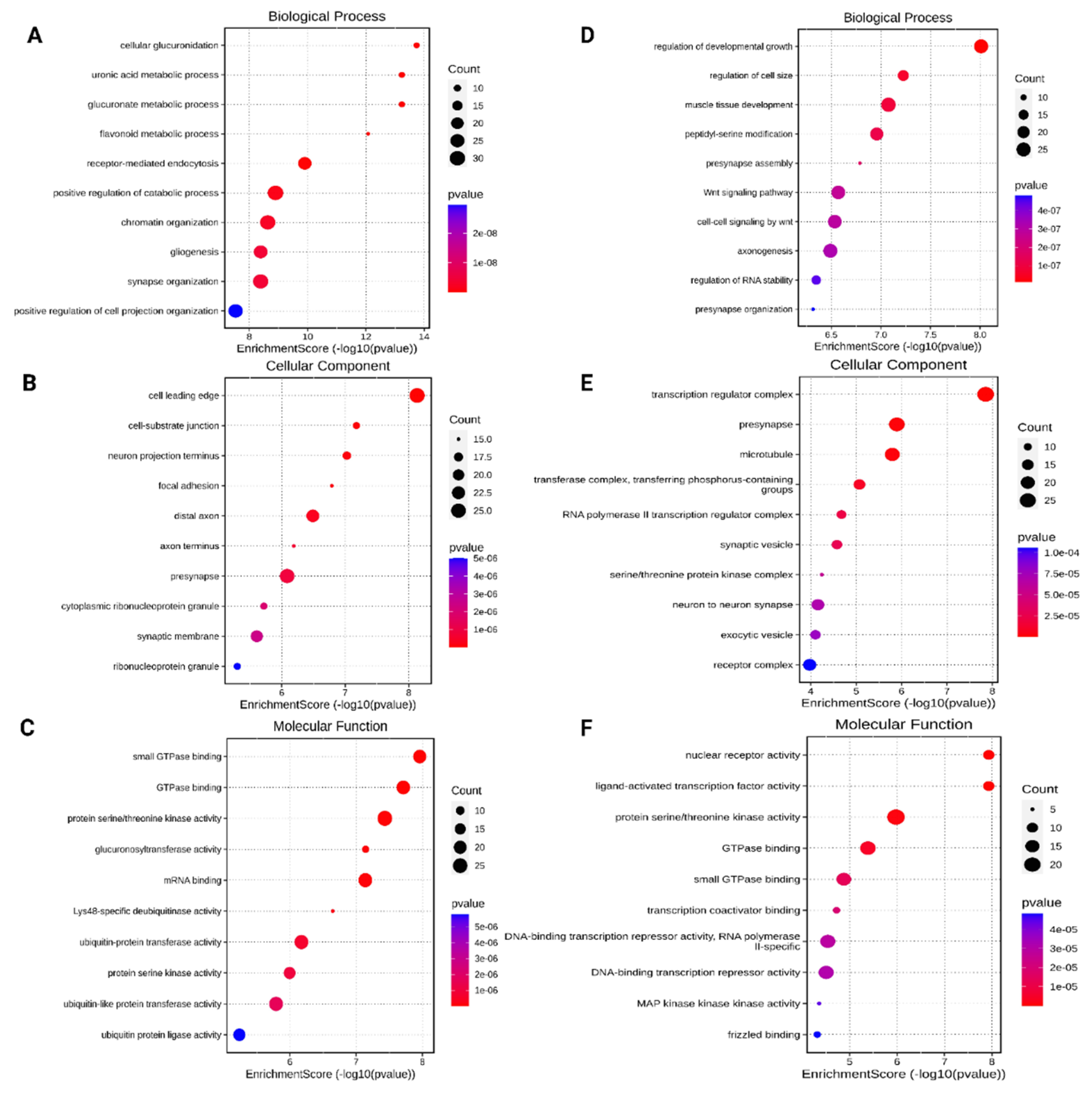

3.3. Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis of the Differentially Expressed miRNAs Target Genes

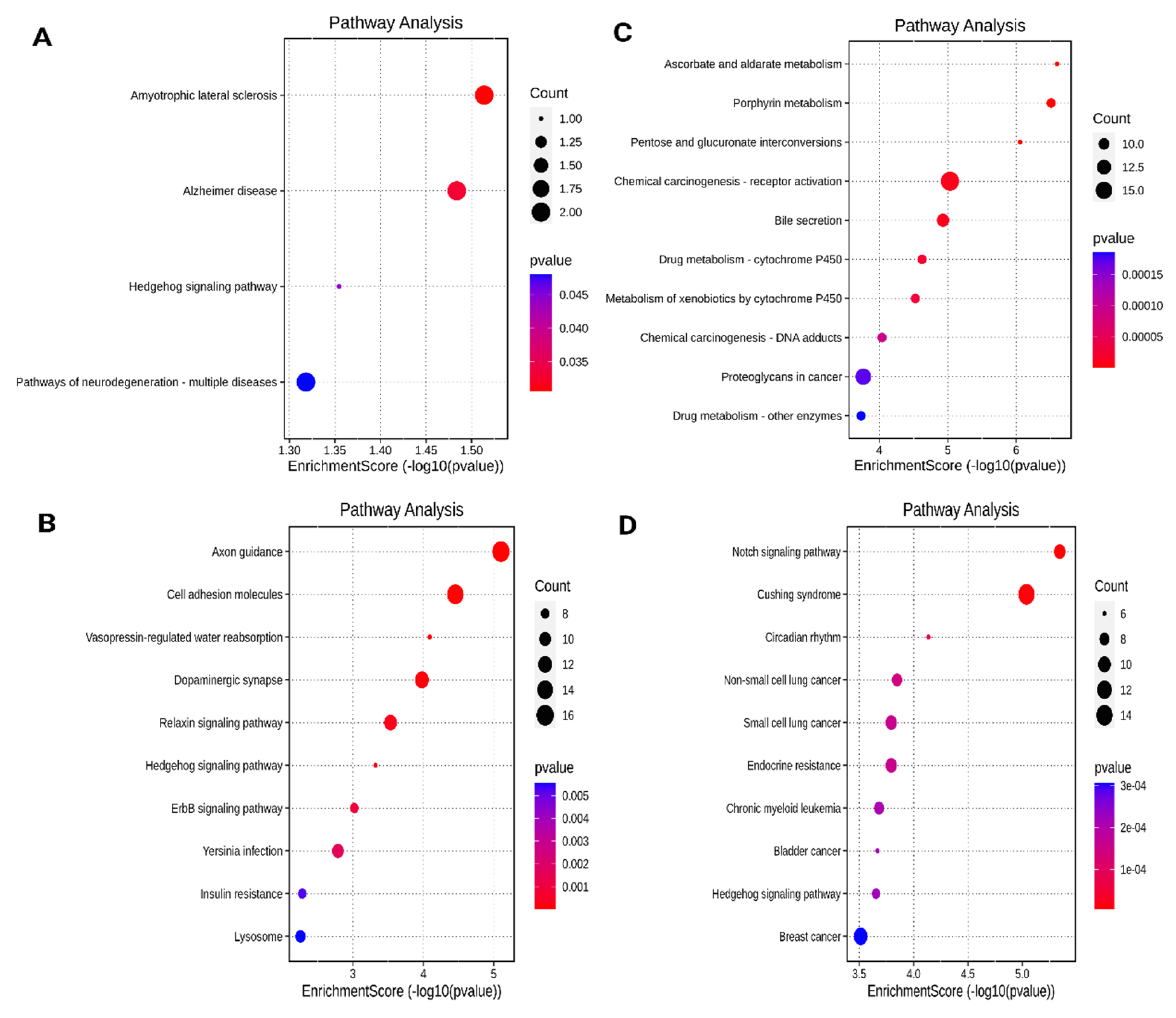

3.4. KEGG Pathway Functional Enrichment Analysis

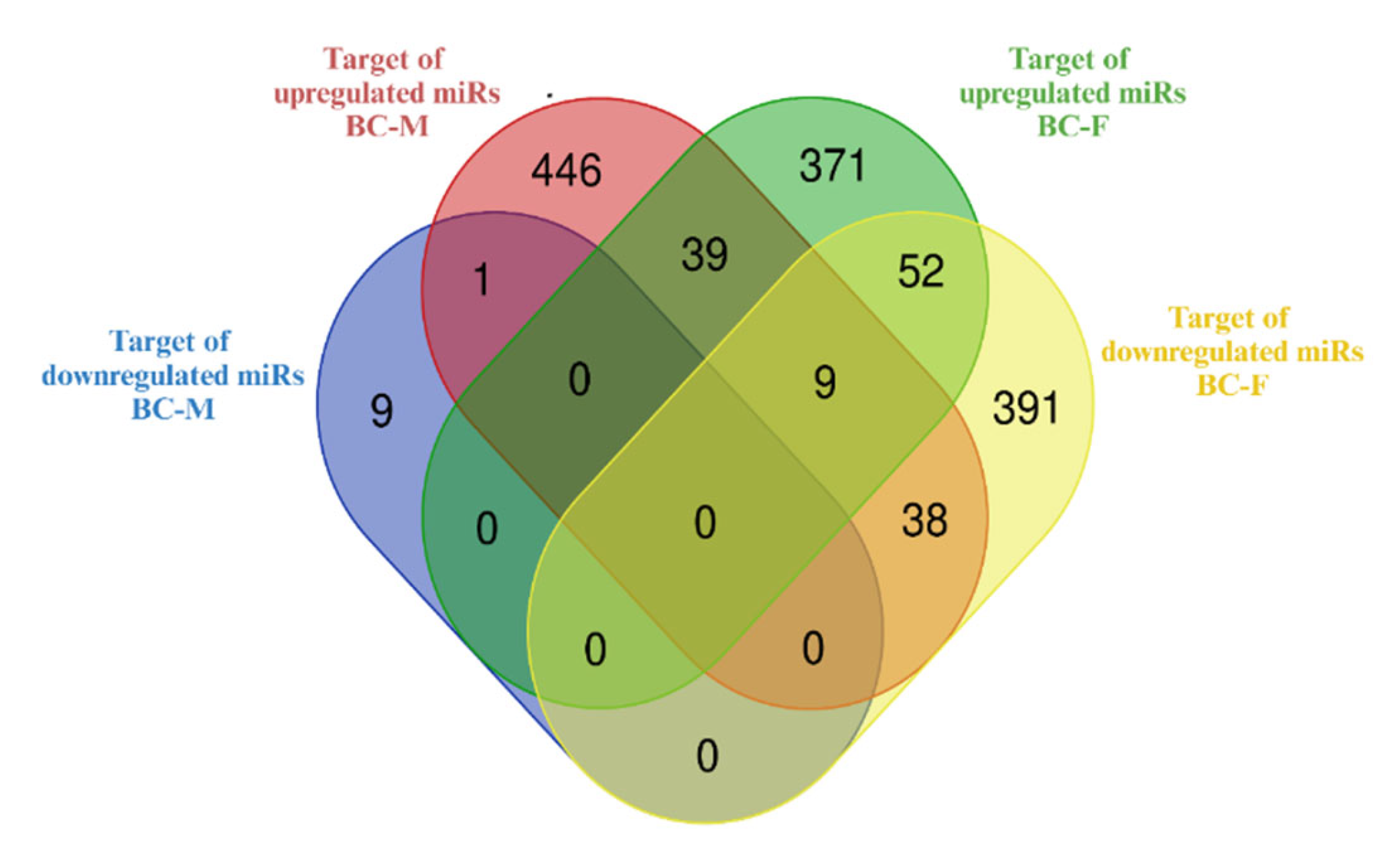

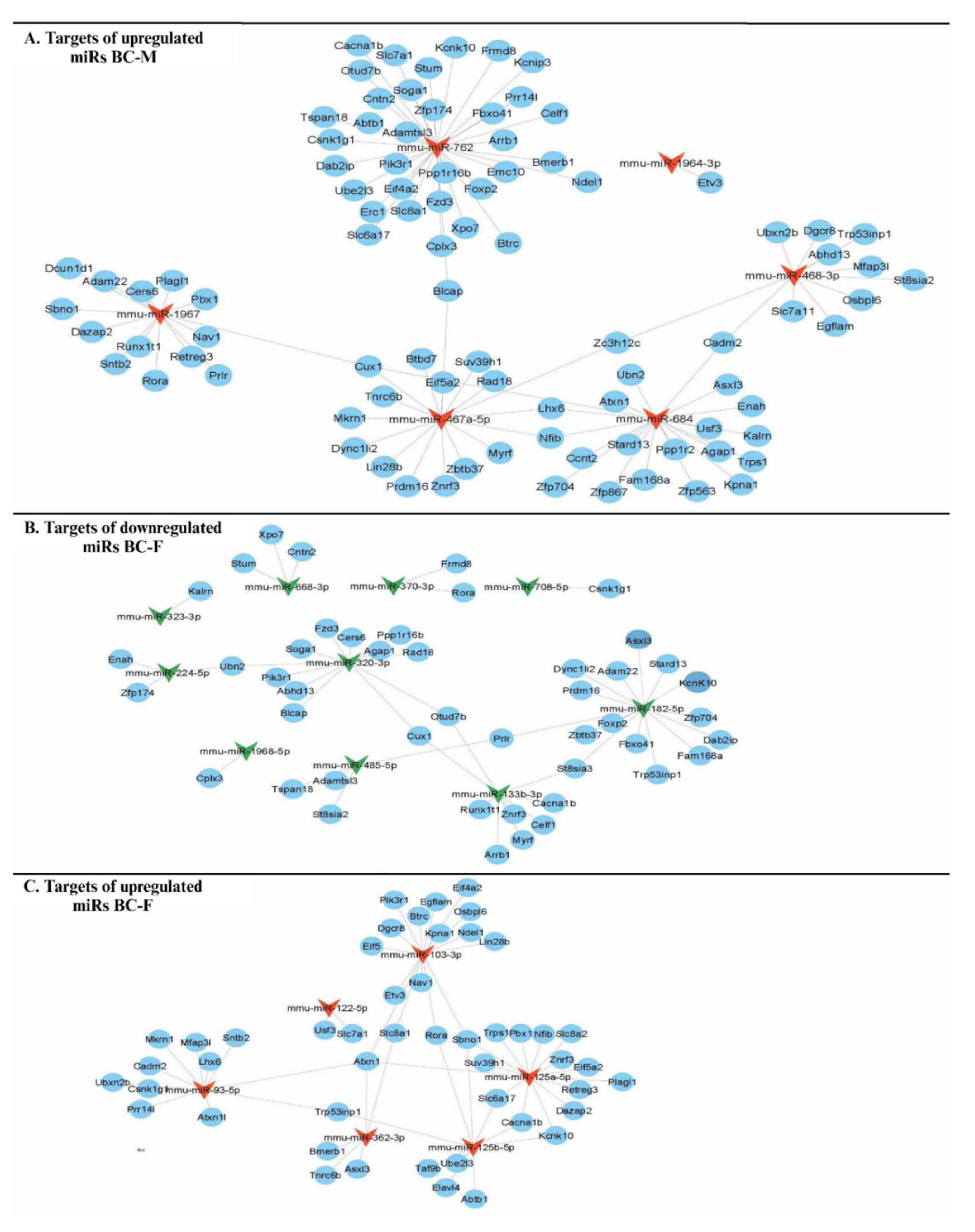

3.5. Construction of miRNA-Gene Interactional Networks and Identification of miRNAs with Bco1 as Target

| Gene | Sex | miRNAs downregulated | miRNAs upregulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bco1 | Male | mmu-miR-763 | - |

| Female | mmu-miR-668, -105, -370, -323, -3p, -290-3p | - |

3.6. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis

| Males upregulated | Females downregulated | Females upregulated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | Node Degree | Genes | Node Degree | Genes | Node Degree |

| Pik3r1 | 23 | Pik3r1 | 29 | Pik3r1 | 23 |

| Arrb1 | 16 | Arrb1 | 16 | Atxn1 | 19 |

| Kalrn | 15 | Xpo7 | 16 | Btrc | 13 |

| Atxn1 | 13 | Kalrn | 13 | Suv39h1 | 12 |

| Cacna1b | 9 | Cacna1b | 11 | Eif4a2 | 10 |

| Ube2l3 | 9 | Celf1 | 11 | Erc1 | 9 |

| Xpo7 | 9 | Foxp2 | 11 | Rora | 8 |

| Btrc | 8 | Cux1 | 9 | Ube2l3 | 7 |

| Dab2ip | 8 | Adam22 | 6 | Cacna1b | 6 |

| Ndel1 | 8 | Cntn2 | 6 | Dgcr8 | 6 |

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson: E.J. The role of carotenoids in human health. Nutr Clin Care 2002, 5, 56-65. [CrossRef]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research, G. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol 2001, 119, 1417-1436. [CrossRef]

- Baswan, S.M.; Klosner, A.E.; Weir, C.; Salter-Venzon, D.; Gellenbeck, K.W.; Leverett, J.; Krutmann, J. Role of ingestible carotenoids in skin protection: A review of clinical evidence. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2021, 37, 490-504. [CrossRef]

- Bonet, M.L.; Ribot, J.; Galmes, S.; Serra, F.; Palou, A. Carotenoids and carotenoid conversion products in adipose tissue biology and obesity: Pre-clinical and human studies. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular and cell biology of lipids 2020, 1865, 158676. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Fondell, E.; Ascherio, A.; Okereke, O.I.; Grodstein, F.; Hofman, A.; Willett, W.C. Long-Term Intake of Dietary Carotenoids Is Positively Associated with Late-Life Subjective Cognitive Function in a Prospective Study in US Women. J Nutr 2020, 150, 1871-1879. [CrossRef]

- Abrego-Guandique, D.M.; Bonet, M.L.; Caroleo, M.C.; Cannataro, R.; Tucci, P.; Ribot, J.; Cione, E. The Effect of Beta-Carotene on Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Bonet, M.L.; Borel, P.; Keijer, J.; Landrier, J.F.; Milisav, I.; Ribot, J.; Riso, P.; Winklhofer-Roob, B.; Sharoni, Y.; et al. Mechanistic aspects of carotenoid health benefits - where are we now? Nutr Res Rev 2021, 34, 276-302. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Sahin, K.; Bilen, H.; Bahcecioglu, I.H.; Bilir, B.; Ashraf, S.; Halazun, K.J.; Kucuk, O. Carotenoids and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2015, 4, 161-171. [CrossRef]

- Elvira-Torales, L.I.; Garcia-Alonso, J.; Periago-Caston, M.J. Nutritional Importance of Carotenoids and Their Effect on Liver Health: A Review. Antioxidants 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Willeit, P.; Skroblin, P.; Kiechl, S.; Fernandez-Hernando, C.; Mayr, M. Liver microRNAs: potential mediators and biomarkers for metabolic and cardiovascular disease? European heart journal 2016, 37, 3260-3266. [CrossRef]

- Cione, E.; Abrego Guandique, D.M.; Caroleo, M.C.; Luciani, F.; Colosimo, M.; Cannataro, R. Liver Damage and microRNAs: An Update. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2022, 45, 78-91. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Liu, C.; Hu, K.Q.; Smith, D.E.; Wang, X.D. Ablation of carotenoid cleavage enzymes (BCO1 and BCO2) induced hepatic steatosis by altering the farnesoid X receptor/miR-34a/sirtuin 1 pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys 2018, 654, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Peleg-Raibstein, D. Understanding the Link Between Maternal Overnutrition, Cardio-Metabolic Dysfunction and Cognitive Aging. Front Neurosci 2021, 15, 645569. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. The roles of microRNAs in epigenetic regulation. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2019, 51, 11-17. [CrossRef]

- Perri, M.; Lucente, M.; Cannataro, R.; De Luca, I.F.; Gallelli, L.; Moro, G.; De Sarro, G.; Caroleo, M.C.; Cione, E. Variation in Immune-Related microRNAs Profile in Human Milk Amongst Lactating Women. Microrna 2018, 7, 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Pomar, C.A.; Castro, H.; Pico, C.; Serra, F.; Palou, A.; Sanchez, J. Cafeteria Diet Consumption during Lactation in Rats, Rather than Obesity Per Se, alters miR-222, miR-200a, and miR-26a Levels in Milk. Mol Nutr Food Res 2019, 63, e1800928. [CrossRef]

- Puppala, S.; Li, C.; Glenn, J.P.; Saxena, R.; Gawrieh, S.; Quinn, A.; Palarczyk, J.; Dick, E.J., Jr.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Cox, L.A. Primate fetal hepatic responses to maternal obesity: epigenetic signalling pathways and lipid accumulation. J Physiol 2018, 596, 5823-5837. [CrossRef]

- Sugino, K.Y.; Mandala, A.; Janssen, R.C.; Gurung, S.; Trammell, M.; Day, M.W.; Brush, R.S.; Papin, J.F.; Dyer, D.W.; Agbaga, M.P.; et al. Western diet-induced shifts in the maternal microbiome are associated with altered microRNA expression in baboon placenta and fetal liver. Front Clin Diabetes Healthc 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Benatti, R.O.; Melo, A.M.; Borges, F.O.; Ignacio-Souza, L.M.; Simino, L.A.; Milanski, M.; Velloso, L.A.; Torsoni, M.A.; Torsoni, A.S. Maternal high-fat diet consumption modulates hepatic lipid metabolism and microRNA-122 (miR-122) and microRNA-370 (miR-370) expression in offspring. Br J Nutr 2014, 111, 2112-2122. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Didelot, X.; Bruce, K.D.; Cagampang, F.R.; Vatish, M.; Hanson, M.; Lehnert, H.; Ceriello, A.; Byrne, C.D. Maternal high fat diet during pregnancy and lactation alters hepatic expression of insulin like growth factor-2 and key microRNAs in the adult offspring. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 478. [CrossRef]

- Mennitti, L.V.; Carpenter, A.A.M.; Loche, E.; Pantaleao, L.C.; Fernandez-Twinn, D.S.; Schoonejans, J.M.; Blackmore, H.L.; Ashmore, T.J.; Pisani, L.P.; Tadross, J.A.; et al. Effects of maternal diet-induced obesity on metabolic disorders and age-associated miRNA expression in the liver of male mouse offspring. Int J Obes (Lond) 2022, 46, 269-278. [CrossRef]

- Lipkie, T.E.; Morrow, A.L.; Jouni, Z.E.; McMahon, R.J.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Longitudinal Survey of Carotenoids in Human Milk from Urban Cohorts in China, Mexico, and the USA. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0127729. [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathan, R.; Panagos, P.; Sen, S. Breast milk carotenoid concentrations are decreased in obese mothers. In Proceedings of the The FASEB Journal 2014 28:1_supplement, 2014.

- Arreguin, A.; Ribot, J.; Musinovic, H.; von Lintig, J.; Palou, A.; Bonet, M.L. Dietary vitamin A impacts DNA methylation patterns of adipogenesis-related genes in suckling rats. Arch Biochem Biophys 2018, 650, 75-84. [CrossRef]

- O'Byrne, S.M.; Kako, Y.; Deckelbaum, R.J.; Hansen, I.H.; Palczewski, K.; Goldberg, I.J.; Blaner, W.S. Multiple pathways ensure retinoid delivery to milk: studies in genetically modified mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010, 298, E862-870. [CrossRef]

- Rath, E.A.; Thenen, S.W. Use of tritiated water for measurement of 24-hour milk intake in suckling lean and genetically obese (ob/ob) mice. J Nutr 1979, 109, 840-847. [CrossRef]

- Musinovic, H.; Bonet, M.L.; Granados, N.; Amengual, J.; von Lintig, J.; Ribot, J.; Palou, A. beta-Carotene during the suckling period is absorbed intact and induces retinoic acid dependent responses similar to preformed vitamin A in intestine and liver, but not adipose tissue of young rats. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014, 58, 2157-2165. [CrossRef]

- Geiss, G.K.; Bumgarner, R.E.; Birditt, B.; Dahl, T.; Dowidar, N.; Dunaway, D.L.; Fell, H.P.; Ferree, S.; George, R.D.; Grogan, T.; et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol 2008, 26, 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Tastsoglou, S.; Skoufos, G.; Miliotis, M.; Karagkouni, D.; Koutsoukos, I.; Karavangeli, A.; Kardaras, F.S.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G. DIANA-miRPath v4.0: expanding target-based miRNA functional analysis in cell-type and tissue contexts. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W154-W159. [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Silva, B.; Gao, T.; Xu, Z.; Cui, J. Dynamic and Modularized MicroRNA Regulation and Its Implication in Human Cancers. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 13356. [CrossRef]

- von Lintig, J.; Vogt, K. Filling the gap in vitamin A research. Molecular identification of an enzyme cleaving beta-carotene to retinal. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 11915-11920.

- Rao, M.S.; Van Vleet, T.R.; Ciurlionis, R.; Buck, W.R.; Mittelstadt, S.W.; Blomme, E.A.G.; Liguori, M.J. Comparison of RNA-Seq and Microarray Gene Expression Platforms for the Toxicogenomic Evaluation of Liver From Short-Term Rat Toxicity Studies. Front Genet 2018, 9, 636. [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, C.; Muntion, S.; Roson, B.; Blanco, B.; Lopez-Villar, O.; Carrancio, S.; Sanchez-Guijo, F.M.; Diez-Campelo, M.; Alvarez-Fernandez, S.; Sarasquete, M.E.; et al. Impaired expression of DICER, DROSHA, SBDS and some microRNAs in mesenchymal stromal cells from myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1218-1224. [CrossRef]

- Rando, G.; Wahli, W. Sex differences in nuclear receptor-regulated liver metabolic pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1812, 964-973. [CrossRef]

- Nevola, R.; Tortorella, G.; Rosato, V.; Rinaldi, L.; Imbriani, S.; Perillo, P.; Mastrocinque, D.; La Montagna, M.; Russo, A.; Di Lorenzo, G.; et al. Gender Differences in the Pathogenesis and Risk Factors of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- van Helden, Y.G.; Godschalk, R.W.; von Lintig, J.; Lietz, G.; Landrier, J.F.; Bonet, M.L.; van Schooten, F.J.; Keijer, J. Gene expression response of mouse lung, liver and white adipose tissue to beta-carotene supplementation, knockout of Bcmo1 and sex. Mol Nutr Food Res 2011, 55, 1466-1474. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.; Gustavsson, C.; Norstedt, G.; Tollet-Egnell, P. Sex-different and growth hormone-regulated expression of microRNA in rat liver. BMC Mol Biol 2009, 10, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lagos-Quintana, M.; Rauhut, R.; Yalcin, A.; Meyer, J.; Lendeckel, W.; Tuschl, T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol 2002, 12, 735-739. [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Friedman, J.R. miR-122 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism and tumor suppression. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 2773-2776. [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, D.; Drosatos, K.; Hiyama, Y.; Goldberg, I.J.; Zannis, V.I. MicroRNA-370 controls the expression of microRNA-122 and Cpt1alpha and affects lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res 2010, 51, 1513-1523. [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, F.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wen, J.; Farris, A.B.; Czaja, M.J. Redundant Functions of ERK1 and ERK2 Maintain Mouse Liver Homeostasis Through Down-Regulation of Bile Acid Synthesis. Hepatol Commun 2022, 6, 980-994. [CrossRef]

- Matz-Soja, M.; Rennert, C.; Schonefeld, K.; Aleithe, S.; Boettger, J.; Schmidt-Heck, W.; Weiss, T.S.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Zellmer, S.; Kloting, N.; et al. Hedgehog signaling is a potent regulator of liver lipid metabolism and reveals a GLI-code associated with steatosis. Elife 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Sedzikowska, A.; Szablewski, L. Insulin and Insulin Resistance in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Huebbe, P.; Lange, J.; Lietz, G.; Rimbach, G. Dietary beta-carotene and lutein metabolism is modulated by the APOE genotype. Biofactors 2016, 42, 388-396. [CrossRef]

- Raulin, A.C.; Doss, S.V.; Trottier, Z.A.; Ikezu, T.C.; Bu, G.; Liu, C.C. ApoE in Alzheimer's disease: pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Mol Neurodegener 2022, 17, 72. [CrossRef]

- Shete, V.; Costabile, B.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Quadro, L. Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Contributes to beta-Carotene Uptake in the Maternal Liver. Nutrients 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Karppi, J.; Nurmi, T.; Kurl, S.; Rissanen, T.H.; Nyyssonen, K. Lycopene, lutein and beta-carotene as determinants of LDL conjugated dienes in serum. Atherosclerosis 2010, 209, 565-572. [CrossRef]

- Linna, M.S.; Ahotupa, M.; Kukkonen-Harjula, K.; Fogelholm, M.; Vasankari, T.J. Co-existence of insulin resistance and high concentrations of circulating oxidized LDL lipids. Ann Med 2015, 47, 394-398. [CrossRef]

- Holvoet, P.; De Keyzer, D.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr. Oxidized LDL and the metabolic syndrome. Future Lipidol 2008, 3, 637-649. [CrossRef]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Nikiforov, N.G.; Markin, A.M.; Kashirskikh, D.A.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Gerasimova, E.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Overview of OxLDL and Its Impact on Cardiovascular Health: Focus on Atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 613780. [CrossRef]

- Yamchuen, P.; Aimjongjun, S.; Limpeanchob, N. Oxidized low density lipoprotein increases acetylcholinesterase activity correlating with reactive oxygen species production. Neurochem Int 2014, 78, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Harari, A.; Coster, A.C.F.; Jenkins, A.; Xu, A.; Greenfield, J.R.; Harats, D.; Shaish, A.; Samocha-Bonet, D. Obesity and Insulin Resistance Are Inversely Associated with Serum and Adipose Tissue Carotenoid Concentrations in Adults. J Nutr 2020, 150, 38-46. [CrossRef]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Chen, X.; Jha, K.; Beydoun, H.A.; Zonderman, A.B.; Canas, J.A. Carotenoids, vitamin A, and their association with the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 2019, 77, 32-45. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Jimenez, F.J.; Molina, J.A.; de Bustos, F.; Orti-Pareja, M.; Benito-Leon, J.; Tallon-Barranco, A.; Gasalla, T.; Porta, J.; Arenas, J. Serum levels of beta-carotene, alpha-carotene and vitamin A in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurol 1999, 6, 495-497. [CrossRef]

- Mullan, K.; Williams, M.A.; Cardwell, C.R.; McGuinness, B.; Passmore, P.; Silvestri, G.; Woodside, J.V.; McKay, G.J. Serum concentrations of vitamin E and carotenoids are altered in Alzheimer's disease: A case-control study. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2017, 3, 432-439. [CrossRef]

- Ciarambino, T.; Crispino, P.; Guarisco, G.; Giordano, M. Gender Differences in Insulin Resistance: New Knowledge and Perspectives. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2023, 45, 7845-7861. [CrossRef]

- Macotela, Y.; Boucher, J.; Tran, T.T.; Kahn, C.R. Sex and depot differences in adipocyte insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Diabetes 2009, 58, 803-812. [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Su, J.; Liu, R.; Zhao, S.; Li, W.; Xu, X.; Li, D.; Shi, J.; Gu, B.; Zhang, J.; et al. Sexual dimorphism in glucose metabolism is shaped by androgen-driven gut microbiome. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 7080. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Zampino, M.; Tanaka, T.; Bandinelli, S.; Moaddel, R.; Fantoni, G.; Candia, J.; Ferrucci, L.; Semba, R.D. The Plasma Proteome Fingerprint Associated with Circulating Carotenoids and Retinol in Older Adults. J Nutr 2022, 152, 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Janesick, A.; Wu, S.C.; Blumberg, B. Retinoic acid signaling and neuronal differentiation. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015, 72, 1559-1576. [CrossRef]

- Reay, W.R.; Kiltschewskij, D.J.; Di Biase, M.A.; Gerring, Z.F.; Kundu, K.; Surendran, P.; Greco, L.A.; Clarke, E.D.; Collins, C.E.; Mondul, A.M.; et al. Genetic influences on circulating retinol and its relationship to human health. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1490. [CrossRef]

- Kanki, K.; Akechi, Y.; Ueda, C.; Tsuchiya, H.; Shimizu, H.; Ishijima, N.; Toriguchi, K.; Hatano, E.; Endo, K.; Hirooka, Y.; et al. Biological and clinical implications of retinoic acid-responsive genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Hepatol 2013, 59, 1037-1044. [CrossRef]

- van Helden, Y.G.; Godschalk, R.W.; Swarts, H.J.; Hollman, P.C.; van Schooten, F.J.; Keijer, J. Beta-carotene affects gene expression in lungs of male and female Bcmo1 (-/-) mice in opposite directions. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011, 68, 489-504. [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.G.; Jung, H.J.; Kim, S.; Arulkumar, R.; Kim, D.H.; Park, D.; Chung, H.Y. Regulation of Circadian Genes Nr1d1 and Nr1d2 in Sex-Different Manners during Liver Aging. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Rivkin, M.; Berkovits, L.; Simerzin, A.; Zorde-Khvalevsky, E.; Rosenberg, N.; Klein, S.; Yaish, D.; Durst, R.; Shpitzen, S.; et al. Metabolic Circuit Involving Free Fatty Acids, microRNA 122, and Triglyceride Synthesis in Liver and Muscle Tissues. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 1404-1415. [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.K.; Panda, S.; Miraglia, L.J.; Reyes, T.M.; Rudic, R.D.; McNamara, P.; Naik, K.A.; FitzGerald, G.A.; Kay, S.A.; Hogenesch, J.B. A functional genomics strategy reveals Rora as a component of the mammalian circadian clock. Neuron 2004, 43, 527-537. [CrossRef]

- Ersahin, T.; Tuncbag, N.; Cetin-Atalay, R. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR interactive pathway. Mol Biosyst 2015, 11, 1946-1954. [CrossRef]

- Tsay, A.; Wang, J.C. The Role of PIK3R1 in Metabolic Function and Insulin Sensitivity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.W.; Mills, G.B. Targeting therapeutic liabilities engendered by PIK3R1 mutations for cancer treatment. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 17, 297-307. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Ma, T.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, F.; Peng, K.; Li, B. beta-Carotene Attenuates Apoptosis and Autophagy via PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Necrotizing Enterocolitis Model Cells IEC-6. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022, 2022, 2502263. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. Beta carotene protects H9c2 cardiomyocytes from advanced glycation end product-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, and autophagy via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 647. [CrossRef]

- Amengual, J.; Gouranton, E.; van Helden, Y.G.; Hessel, S.; Ribot, J.; Kramer, E.; Kiec-Wilk, B.; Razny, U.; Lietz, G.; Wyss, A.; et al. Beta-carotene reduces body adiposity of mice via BCMO1. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20644. [CrossRef]

- Coronel, J.; Yu, J.; Pilli, N.; Kane, M.A.; Amengual, J. The conversion of beta-carotene to vitamin A in adipocytes drives the anti-obesogenic effects of beta-carotene in mice. Mol Metab 2022, 66, 101640. [CrossRef]

- Amengual, J.; Coronel, J.; Marques, C.; Aradillas-Garcia, C.; Morales, J.M.V.; Andrade, F.C.D.; Erdman, J.W.; Teran-Garcia, M. beta-Carotene Oxygenase 1 Activity Modulates Circulating Cholesterol Concentrations in Mice and Humans. J Nutr 2020, 150, 2023-2030. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wu, X.; Pinos, I.; Abraham, B.M.; Barrett, T.J.; von Lintig, J.; Fisher, E.A.; Amengual, J. beta-Carotene conversion to vitamin A delays atherosclerosis progression by decreasing hepatic lipid secretion in mice. J Lipid Res 2020, 61, 1491-1503. [CrossRef]

- Pinos, I.; Coronel, J.; Albakri, A.; Blanco, A.; McQueen, P.; Molina, D.; Sim, J.; Fisher, E.A.; Amengual, J. beta-Carotene accelerates the resolution of atherosclerosis in mice. Elife 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.C.; Hessel, S.; Meplan, C.; Flint, J.; Oberhauser, V.; Tourniaire, F.; Hesketh, J.E.; von Lintig, J.; Lietz, G. Two common single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene encoding beta-carotene 15,15'-monoxygenase alter beta-carotene metabolism in female volunteers. FASEB J 2009, 23, 1041-1053. [CrossRef]

- Grune, T.; Lietz, G.; Palou, A.; Ross, A.C.; Stahl, W.; Tang, G.; Thurnham, D.; Yin, S.A.; Biesalski, H.K. Beta-carotene is an important vitamin A source for humans. J Nutr 2010, 140, 2268S-2285S, . [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Gong, X.; Rubin, L.P.; Choi, S.W.; Kim, Y. beta-Carotene 15,15'-oxygenase inhibits cancer cell stemness and metastasis by regulating differentiation-related miRNAs in human neuroblastoma. J Nutr Biochem 2019, 69, 31-43. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).