Submitted:

23 April 2024

Posted:

24 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material, DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.2. Mitome Assembly

2.3. Organellar Genotyping Using PCR and KASP Markers

3. Results

3.1. Confirmed F1 Hybrids

3.2. Mitome Assemblies

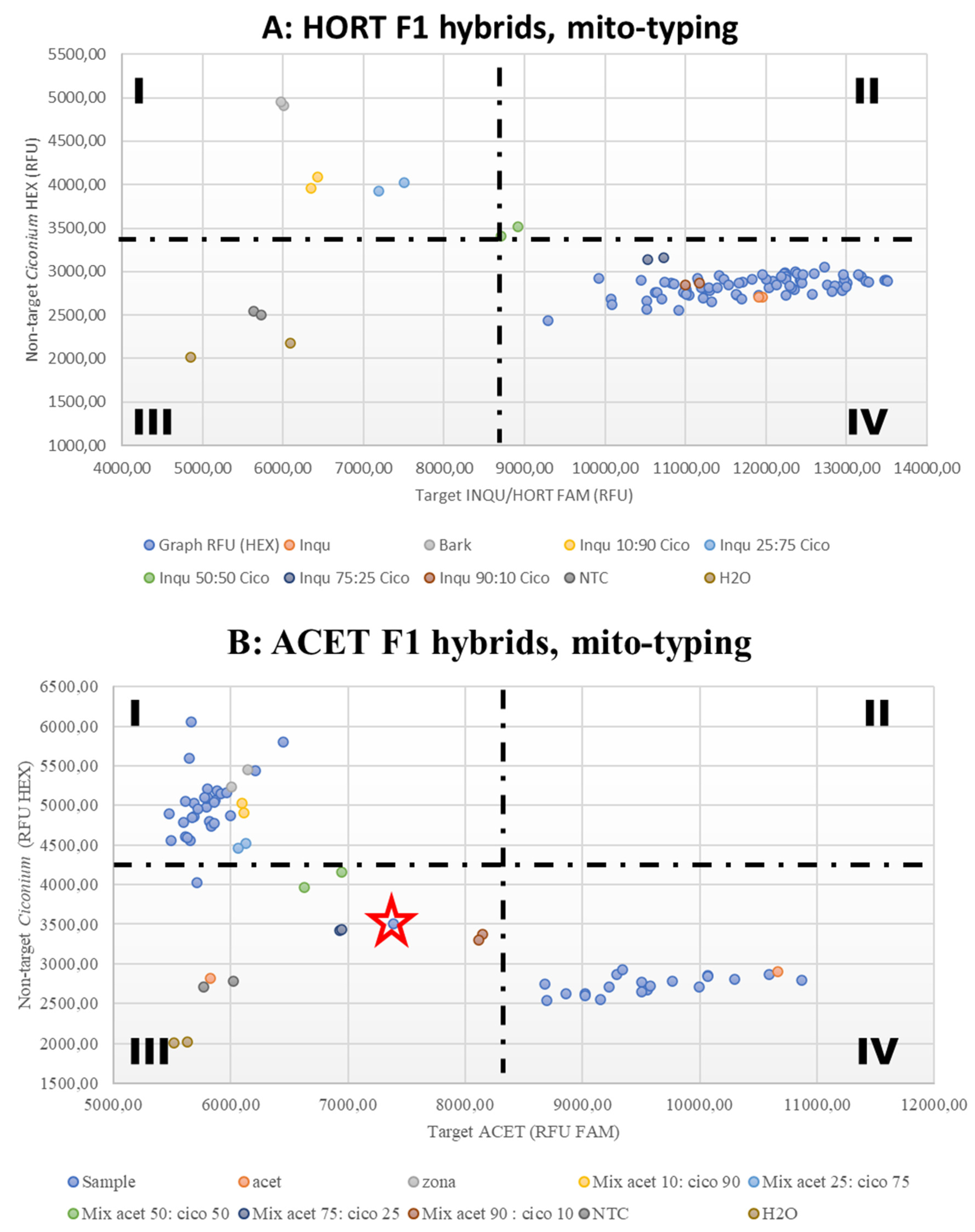

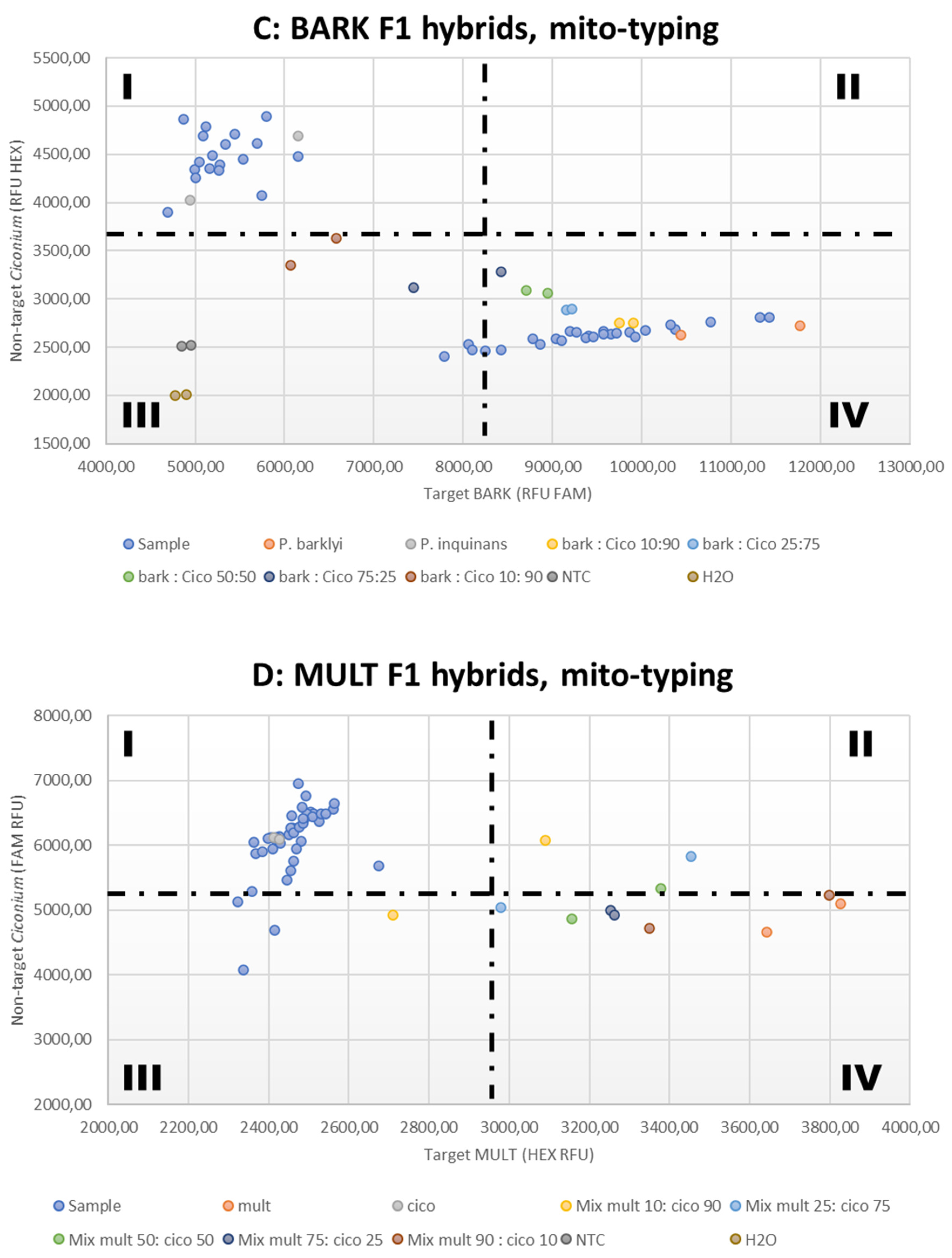

3.3. Mitotyping

4. Discussion

The Case of P. multibracteatum

Evolutionary Effects of mCNI

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baur E. Das Wesen und die Earblichkeitsverhältnisse der ‘varietates albomarginatae hort’ von Pelargonium zonale. Z. Indukt. Abstammungs-Vererbungsl 1909, 1, 330–351. [CrossRef]

- Tilney-Bassett, R. A. E. The control of plastid inheritance in Pelargonium II. Heredity 1973, 30, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tilney-Bassett, R. A. E. The control of plastid inheritance in Pelargonium III. Heredity 1974, 33, 353–360. [CrossRef]

- Tilney-Bassett, R. A. E. “Genetics of variegated plants,” in Genetics and biogenesis of mitochondria and chloroplasts. Eds. C. W.Birky P. S Perlman, and T. J Byers (Columbus: Ohio State University Press), 1975, 268–308.

- Horn, W. Interspecific crossability and inheritance in Pelargonium. Plant Breeding 1994, 113, 3–17. [CrossRef]

- Breman, F.C.; Snijder, R.C.; Korver, J.W.; Pelzer, S.; Sancho-Such, M.; Schranz, M.E.; Bakker, F.T. Interspecific Hybrids Between Pelargonium × hortorum and species From P. section Ciconium reveal biparental plastid inheritance and multi-locus cyto-nuclear incompatibility. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11:614871. [CrossRef]

- Breman, F.C. Exploring patterns of cytonuclear incompatibility in Pelargonium section Ciconium. PhD thesis, Wageningen UR, the Netherlands; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bateson, W. Heredity and variation in modern lights. In Darwin and modern science (ed. A. C. Seward), pp. 85– 101. Cambridge, UK: 1909. Cambridge University Press.

- Dobzhansky T. Studies on hybrid sterility. II. Localization of sterility factors in Drosophila pseudoobscura hybrids. Genetics 1936, 21, 113–135.

- Müller, HJ. Isolating mechanisms, evolution, and temperature. Biol. Symp. 1942, 6, 71–125.

- Schnable, P.S.; Wise, R.P. The molecular basis of cytoplasmic male sterility and fertility restoration. Trends Plant Sci 1998, 3:175–180. [CrossRef]

- Tilney-Bassett, R.A.E.; Almouslem, A.B.; Amoate, H.M. Complementary genes control biparental plastid inheritance in Pelargonium. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1992, 85:317-324. [CrossRef]

- Weihe, A.; Apitz, J.; Salinas, A.; Pohlheim, F.; Börner, T. Biparental inheritance of plastidial and mitochondrial DNA and hybrid variegation in Pelargonium. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2009, 282:587–593. [CrossRef]

- Kuroiwa, T.; Kawazu, T.; Ushida, H.; Ohta, T. Kuroiwa H. Direct evidence of plastid DNA and mitochondrial DNA in sperm cells in relation to biparental inheritance of organelle DNA in Pelargonium zonale by fluorescence/electron microscopy. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 62:307–313.

- Guo, F.L.; Hu, S.Y. Cytological evidence of biparental inheritance of plastids and mitochondria in Pelargonium. Protoplasma. 1995, 186:201-207. [CrossRef]

- Apitz, J.; Weihe, A.; Pohlheim, F.; Börner, T. Biparental inheritance of organelles in Pelargonium: evidence for intergenomic recombination of mitochondrial DNA. Planta 2013, 237:509–515. [CrossRef]

- Sobanski, J.; Giavalisco, P.; Fischer, A.; Kreiner, J.M.; Walther, D.; Schöttler, M.A.; Pellizzer, T.; Golczyk, H.; Obata, T.; Bock, R.; Sears, B.B.; Greiner, S. Chloroplast competition is controlled by lipid biosynthesis in evening primroses. PNAS 2019 Doi: www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1811661116.

- Park, S.; Grewe, F.; Zhu, A.; et al. Dynamic evolution of Geranium mitochondrial genomes through multiple horizontal and intracellular gene transfers. The New Phytologist. 2015, 208(2):570-583. [CrossRef]

- Breman, F.C.; Korver, J.W.; Snijder, R.C.; Bakker, F.T. Plastid-encoded RNA polymerase variation in Pelargonium sect. Ciconium. HORTIC. ADV. 2024, 2. 1. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.J.; Yu, W.B.; Yang, J.B.; et al. GetOrganelle: a fast and versatile toolkit for accurate de novo assembly of organelle genomes. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 241. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, F.T.; Breman, F.C.; Merckx, V. DNA sequence evolution in fast evolving mitochondrial DNA nad1 exons in Geraniaceae and Plantaginaceae. Taxon 2006, 55:887–896. [CrossRef]

- Grewe, F.; Zhu, A.; Mower, J.P. Loss of a trans-splicing nad1 intron from Geraniaceae and transfer of the maturase gene matR to the nucleus in Pelargonium. Genome Biol Evol. 2016, 30;8(10):3193-3201. [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, P.J.; Kumar, A.; Penmetsa, R.V.; Farmer, A.; Schlueter, J.A.; et al. Large-scale development of cost- effective SNP marker assays for diversity assessment and genetic mapping in chickpea and comparative mapping in legumes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012, 10:716–32. [CrossRef]

- Semagn, K.; Babu, R.; Hearne, S. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP): Over view of the technology and its application in crop improvement. Mol. Breed. 2014, 33:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Thyssen, G.N.; Jenkins, J.N.; Fang, D.D. Detection, validation, and application of genotyping-by-sequencing based single nucleotide polymorphisms in upland Cotton. Plant Genome 2014, 8:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ka S, Quinton-Tulloch MJ, Amgai RB, et al. Accelerating public sector rice breeding with high-density KASP markers derived from whole genome sequencing of indica rice. Mol. Breed. 2018, 38:38. [CrossRef]

- Bakker F.T.; Culham A.; Pankhurst C.E.; Gibby M. Mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA-based phylogeny of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). Amer. J. Bot. 2000, 87: 727– 734. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.D.; Adams, K.L.; Cho, Y.; Parkinson, C.L.; Qiu, Y.L.; Song, K. Dynamic evolution of plant mitochondrial genomes: mobile genes and introns and highly variable mutation rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97: 6960–6966. [CrossRef]

- Choi K.; Weng M-L.; Ruhlman T.A.; Jansen R.K. Extensive variation in nucleotide substitution rate and gene/intron loss in mitochondrial genomes of Pelargonium. Mol. Phyl. and Evol. 2021, 155, (106986). [CrossRef]

- Mower J.P.; Touzet P.; Gummow J.S.; Delph L.F.; Palmer J.D.; Extensive variation in synonymous substitution rates in mitochondrial genes of seed plants. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7:135. [CrossRef]

- Kerke, van de S.J.; Shrestha B.; Ruhlman T.A.; Weng M-L.; Jansen R.K.; Jones C.S.; Schlichting C.D.; et al. Plastome based phylogenetics and younger crown node age in Pelargonium. Mol. Phyl. and Evol. 2019, 137:33–43. [CrossRef]

- Kirk J.T.O.; Tilney-Bassett R.A.E. The plastids. Freeman and Co., London 1967, United Kingdom.

- Greiner S.; Sobanski J.; Bock R. Why are most organelle genomes transmitted maternally? Bioessays 2015, 37, 80–94. [CrossRef]

- Kuroiwa, H.; Kuroiwa, T. Giant mitochondria in the mature egg cell of Pelargonium zonale. Protoplasma 1992, 168, 184–188. [CrossRef]

- Maréchal A.; Brisson N. Recombination and the maintenance of plant organelle genome stability. New Phytol. 2010, 186: 299–317.

- Barnard-Kubow, K.B.; McCoy, M.A.; Galloway, L.F. Biparental chloroplast inheritance leads to rescue from cytonuclear incompatibility. New Phytol. 2017, 213(3):1466-1476. [CrossRef]

- Barnard-Kubow, K.B.; So, N.; Galloway, L.F. Cytonuclear incompatibility contributes to the early stages of speciation. Evolution 2016, 70(12):2752-2766. [CrossRef]

- Greiner, S.; Bock, R. Tuning a ménage à trois: Co-evolution and co-adaptation of nuclear and organellar genomes in plants. Bioessays 2013, 35: 354–365. [CrossRef]

- Röschenbleck, J.; Albers, F.; Müller, K.; Weinl, S.; Kudla, J. Phylogenetics, character evolution and a subgeneric revision of the genus Pelargonium (Geraniaceae). Phytotaxa 2014, 159(2), 31–76. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, F.T.; Culham, A.; Daugherty, L.C.; Gibby, M. A trnL-F based phylogeny for species of (Geraniaceae) with small chromosomes in Pelargonium. Plant Species Biol. 1999, 216, 309–324.

- Bakker F.T.; A. Culham A.; Marais E.M.; Gibby M. Nested radiation in Cape Pelargonium. Pp. 75–100 in Bakker FT, Chartrou LW, Gravendeel B, Pielser PB, eds. Plant species-level systematics: new perspectives on pattern and process. A. R. G. Ganter Verlag K. G., Ruggell, Liechtstein 2005.

- Dodsworth S.; Jang T.S.; Struebig M.; Chase M.W.; Weiss-Schneeweiss H.; et al. Genome-wide repeat dynamics reflect phylogenetic distance in closely related allotetraploid Nicotiana (Solanaceae). Pl. Syst. and Evol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Breman, F.C.; Chen G.; Snijder R.C.; Schranz M.E.; F.T. Repeatome-Based Phylogenetics in Pelargonium Section Ciconium (Sweet) Harvey, Genome Biol. and Evol., 2021, 13(12), evab269. [CrossRef]

- Knuth R. Geraniaceae. - In Encler A., (Ed.): Das Pflanzenreich 4, 1–9. – Leipzig (1912), Germany Engelmann.

- Van der Walt J.J.A.; Albers F.; Gibby M. Delimitation of Pelargonium sect. Glaucophyllum. PI. Syst. Evol. 1990, 171: 15—26. [CrossRef]

| species | Herbarium Voucher accession | Institute1 | Acronym used in text |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. acetosum | 1243 | STEU | ACET |

| P. acraeum | 1975 | STEU | ACRA |

| P. alchemilloides | 1885 | STEU | ALCH2x |

| P. alchemilloides | 1882 | STEU | ALCH4x |

| P. articulatum | 1972055 | WAG | ARTI |

| P. barklyi | 1972061 | WAG | BARK |

| P. frutetorum | 0754 | STEU | FRUT |

| P. inquinans | 0682 | STEU | INQU |

| P. multibracteatum | 2902 | STEU | MULT |

| P. peltatum | 1890 | STEU | PELT |

| P. quinquelobatum | 1972049 | WAG | QUIN |

| P. ranuncolophyllum | A3651 | MSUN* | RANU |

| P. tongaense | 3074 | STEU | TONG |

| P. zonale | 1896 | STEU | ZONA |

| P. elongatum | 0854 | STEU | ELON |

| P. aridum | 1847 | STEU | ARID |

| P. insularis | 19990489 | RBGE | INSU |

| P. yemenense sp. nov | 1972037 | WAG | YEME |

| P. omanense sp. nov | 2184 | RBGE | OMAN |

| P. somalense | V-067490 | V | SOMA |

| F1 types | # plants/cross | # marker pairs /cross | fertility phenotype | (M), (P), (B), (H), (R), (WT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acet_x_frut | 2 | 1 | P | M |

| acet_x_inqu | 1 | 2 | P | M |

| acet_x_zona | 12 | 1 | -- | M (11) P (1) |

| alch(4x)_x_bark | 1 | 1 | -- | M |

| alch(4x)_x_yeme | 2 | 1 | P | P |

| bark_x_frut | 3 | 1 | MS | M |

| bark_x_inqu | 1 | 2 | -- | P |

| bark_x_mult | 3 | 2 | MS | M |

| bark_x_quin | 2 | 1 | -- | M(2) P(1) |

| frut_x_acet | 1 | 1 | P | M |

| frut_x_bark | 3 | 1 | MS | M |

| hort(4x)_x_arti(4x) | 8 | 1 | MS | M |

| (hort_x_zona)_x_arid | 5 | 1 | MS | M |

| hort_x_acet | 3 | 2 | P | M |

| hort_x_acra | 1 | 1 | P | M |

| hort_x_alch | 1 | 1 | MS | M |

| hort_x_arid | 6 | 2 | MS | M |

| hort_x_bark | 2 | 1 | -- | M |

| hort_x_frut | 1 | 1 | F | M |

| hort_x_mult | 1 | 1 | MS | M |

| hort_x_quin | 15 | 1 | MS | M(8) P(7) |

| hort_x_tong | 8 | 1 | P | M |

| hort_x_tong(4x) | 1 | 1 | P | M |

| hort_x_zona | 26 | 1 | P | M |

| tong_x_acet | 7 | 1-2 | P | B(1)/P |

| yeme_x_alch(4x) | 1 | 1 | P | P |

| P. inquinans | 1 | 1 | F | WT |

| P. peltatum | 1 | 1 | F | WT |

| P. salmoneum | 1 | 2 | F | WT |

| P. x hortorum_4x° | 1 | 1 | P | WT* |

| P. quinquelobatum | 1 | 3 | F | WT |

| P. yemenense | 1 | 3 | F | WT |

| P. barklyi | 1 | 3 | F | |

| P. aridum | 1 | 3 | F | WT |

| P. quinquelobatum | 1 | 3 | F | WT |

| P. alchemilloides | 1 | 3 | F | WT |

| P. tongaense | 1 | 1 | F | WT |

| P. articulatum | 1 | 1 | F | WT |

| P. multibreacteatum | 1 | 2 | F | WT/H |

| mult_x_acet | 8 | 2-3 | -- | B/H* |

| mult_x_alch | 14 | 2 | P | P/H* |

| mult_x_arid | 3 | 1 | MS | P/H* |

| mult_x_bark | 5 | 2 | MS | B/H* |

| mult_x_inqu | 3 | 1 | -- | P/H* |

| mult_x_pelt | 3 | 1 | MS | P/H* |

| mult_x_quin | 6 | 2 | P | P/H* |

| mult_x_ranu | 9 | 1-2 | P | P/H* |

| mult_x_tong | 2 | 1 | MS | P/H* |

| mult_x_zona | 2 | 2 | MS | P/H* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).