Submitted:

23 April 2024

Posted:

24 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Related Work

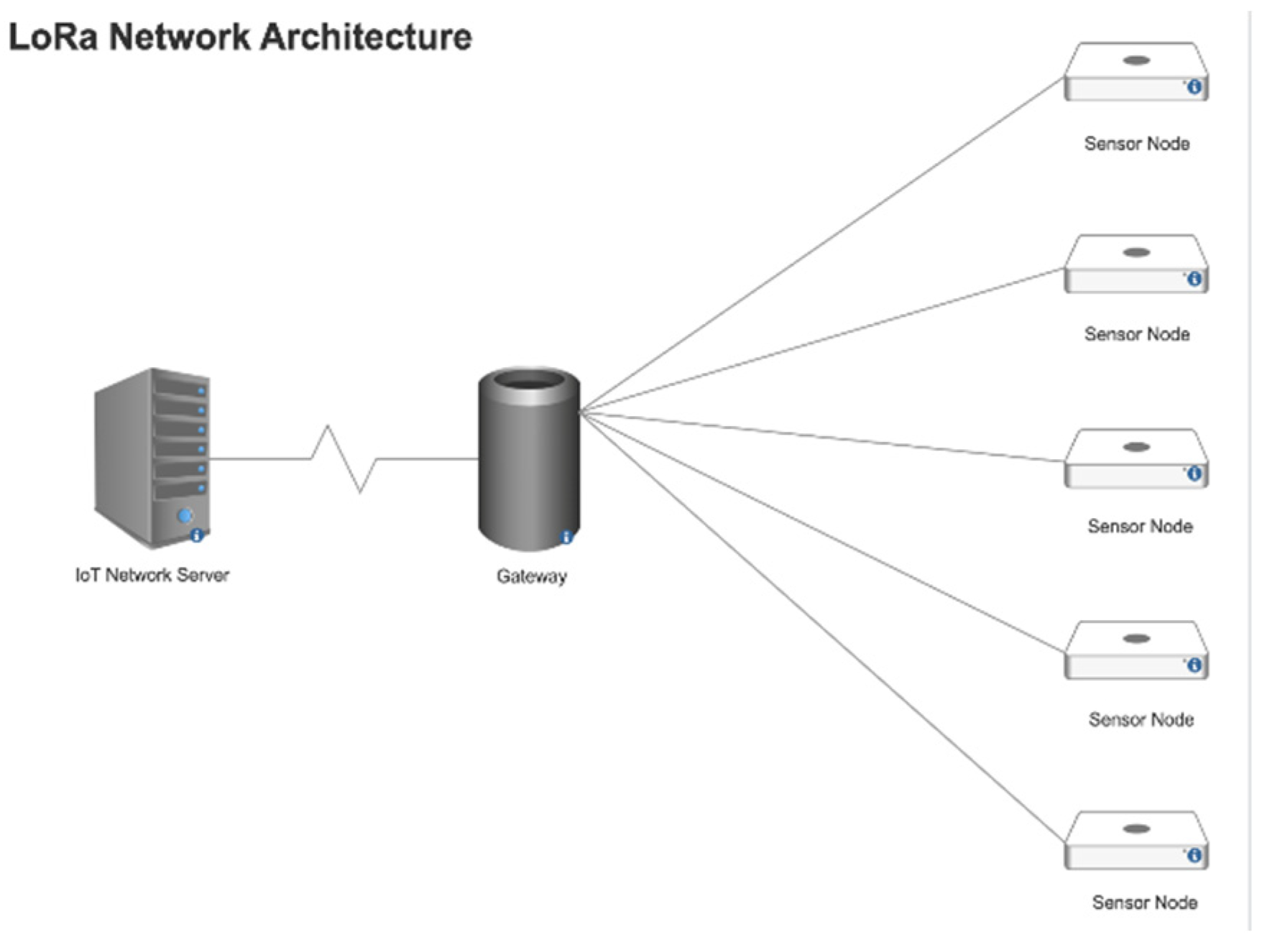

A. LoRaWAN Network for IoT

B. Man-in-the-Middle Attack on LoRaWan

C. Blockchain Security

III. Current Network Design

A. Network Architecture

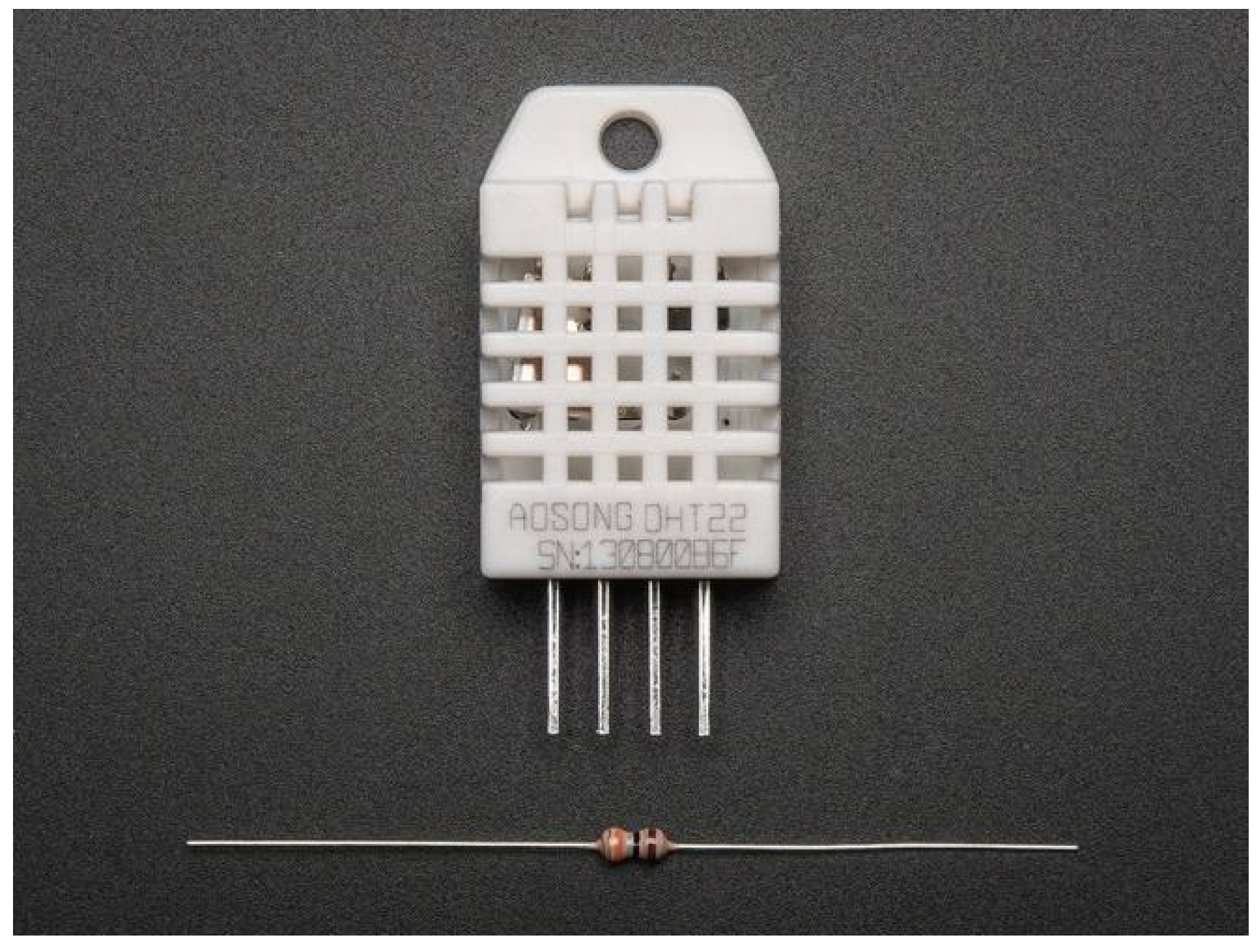

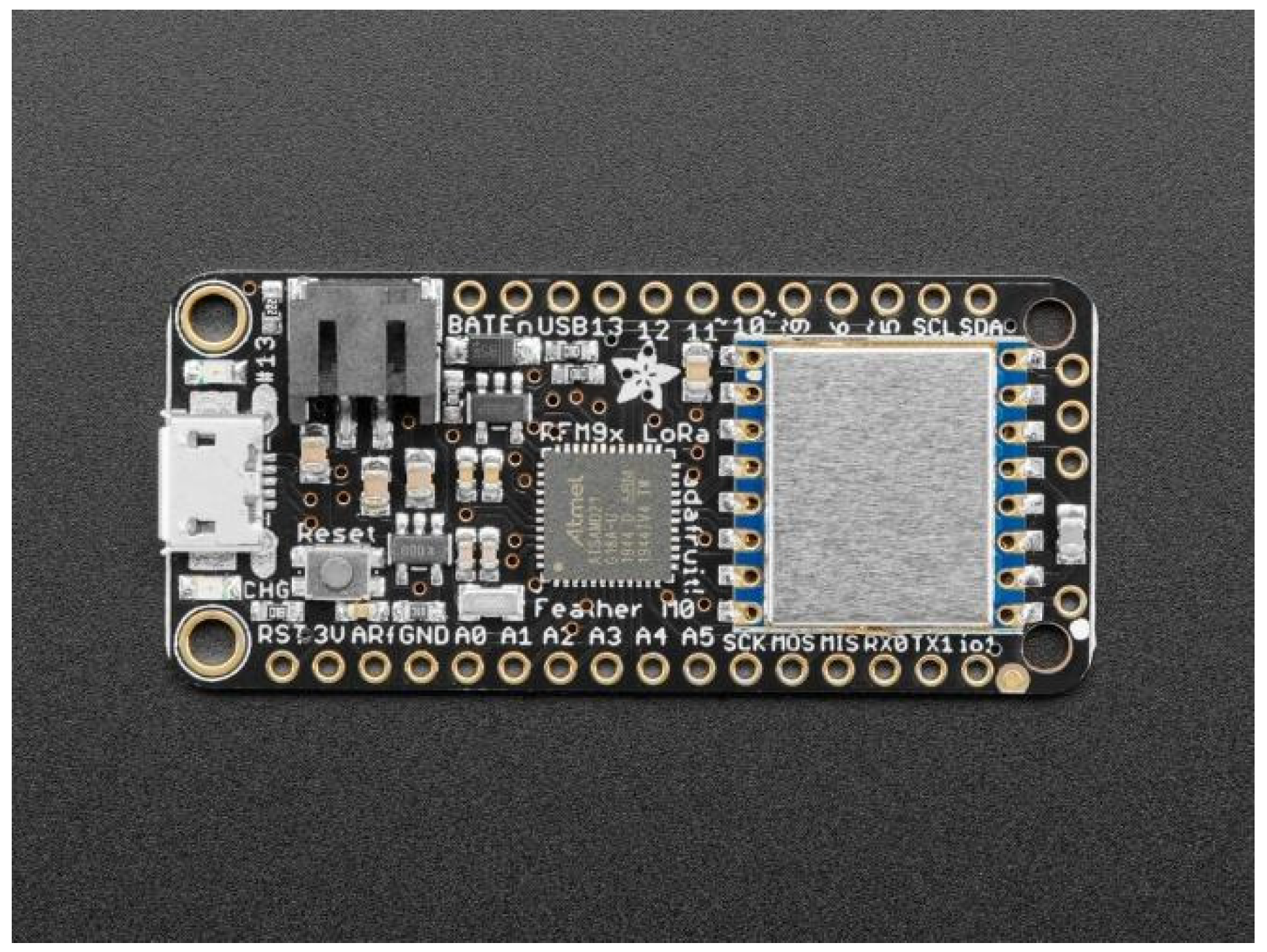

B. Current Hardware Specifications

IV. Blockchain Technology

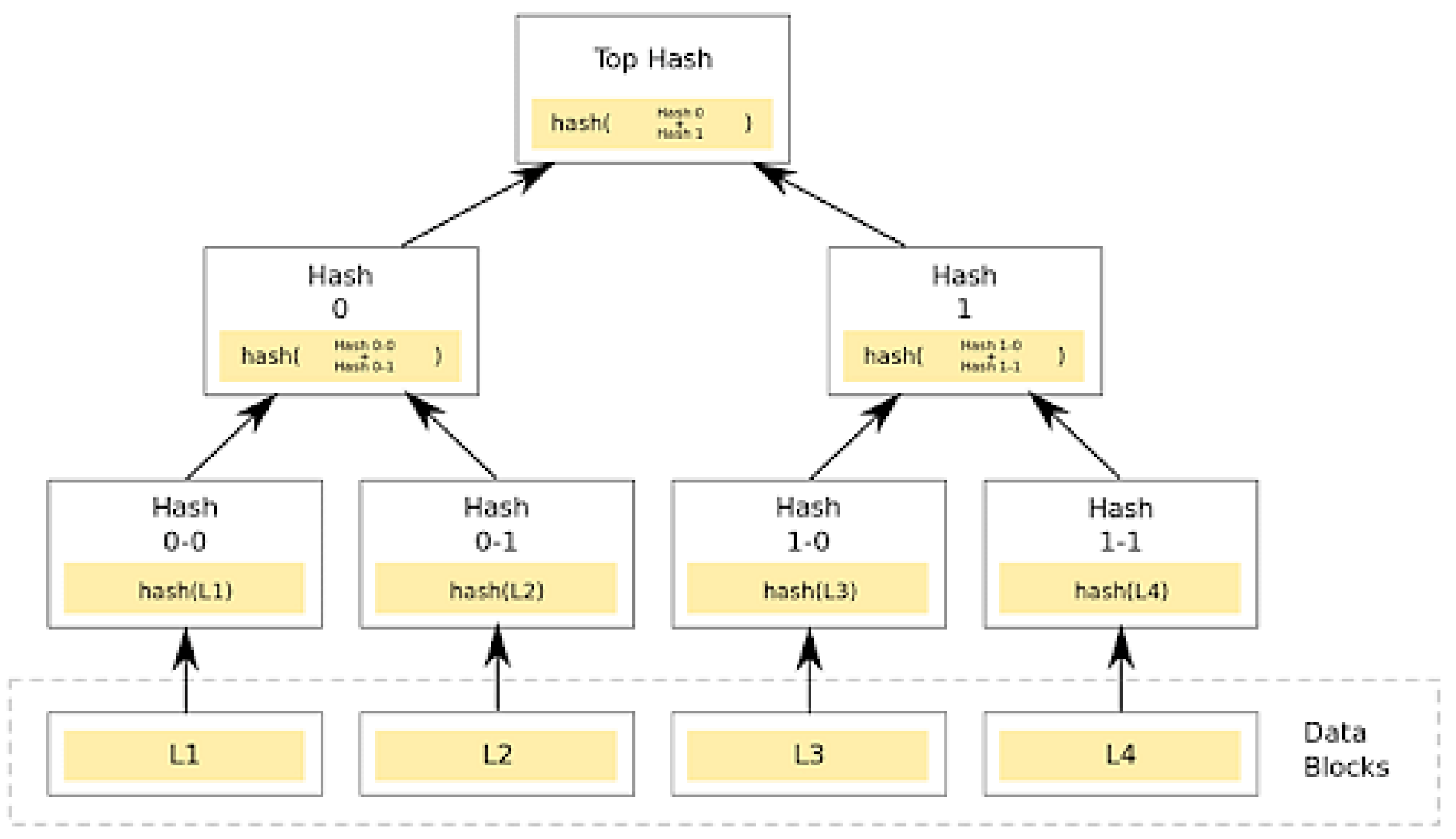

A. Lightweight Scalable Blockchain Architecture Using Ordered Merkle Tree

V. Conclusion and Future Work

References

- Baiocchi, F. C.C. Martins, F. Baiocchi, K. Biondi, S. Teng and C.P. De Souza, “User-Generated Data Collected from a Wireless Sensor Network: Monitoring Air Pollution Levels in the Azores, 2019, Guimarães. Anais do XI International Conference on Engineering and Computer Education - ICECE2019, 2019. p. 1-2.

- M. R. Villarim, D. F. Medeiros, L. C. S Medeiros, C. P. de Souza, M. H. Pontieri, N. A dos Santos and O. Baiocchi, “A Calibrated Intelligent Sensor for Monitoring of Particulate Matter in Smart Cities,” Sensors and Transducers, vol. 250, no. 3, pp. 1–9, Mar. 2021.

- K. Biondi, E. Al-Masri, O. Baiocchi, S. Jeyaraman, E. Pospisil, G. Boyer, and C. P. de Souza, “Air Pollution Detection System using Edge Computing,” in 2019 International Conference on Engineering Applications, ICEA 2019 - Proceedings, 2019.

- M. R. Villarim, J. V. H. de Luna, D. F. Medeiros, R. I. S. Pereira, and C. P. de Souza, “LoRa performance assessment in dense urban and forest areas for environmental monitoring,” in INSCIT 2019 - 4th International Symposium on Instrumentation Systems, Circuits and Transducers, 2019.

- J. P. Shanmuga Sundaram, W. Du and Z. Zhao, "A Survey on LoRa Networking: Research Problems, Current Solutions, and Open Issues," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 371-388, Firstquarter 2020. [CrossRef]

- What Is LoRa? [online] Available: https://www.semtech.com/lora/what-is-lora.

- Semtech, [Online]. Available: [Archived from the original on Julu 18, 2019]. [Accessed: February 5, 2020.].

- J. P. Shanmuga Sundaram, W. Du and Z. Zhao, "A Survey on LoRa Networking: Research Problems, Current Solutions, and Open Issues," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 371-388, Firstquarter 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Reynders and S. Pollin, “Chirp spread spectrum as a modulation technique for a long-range communication,” in Proceeding of the 2016 Symposium on Communications and Vehicular Technologies (SCVT), Mons, Belgium, 22-22 November 2016, pp. 1-5.

- LoRa Alliance, “LoRaWAN 1.0 Specification,” 2015 [Online]. Available: https://lora-alliance.org/resource-hub/lorawanr-specification-v10.

- LoRa Alliance, “LoRaWAN 1.0 Specification,” 2017 [Online]. Available: https://lora-alliance.org/resource-hub/lorawanr-specification-v11.

- LoRa Alliance, “LoRaWAN 1.0.3 Specification,” 2018 [Online]. Available: https://lora-alliance.org/resource-hub.lorawanr-specification-v103.

- J.P. Shanmuga Sundaram, W. Du, Z. Zhao, “A Survey on LoRa Networking: Research Problems, Current Solutions, and Open Issues,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 371-388, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J.Haxhibeqiri, E. De Poorter, I. Moerman, and J. Hoebeke, “A Survey of LoRAWAN for IoT: From Tehnology to Application, “Sensors, vol. 18, no. 11, pp.3995, 2018. [CrossRef]

- U.Raza, P. Kulkarni, and M. Sooriyabandara, “Low Power Wide Area Networks: An Overview,” IEEE Communications Survey & Tutorials, vol. 19, no. 2, pp.855-873, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Vangelista, A. Zanella, and M. Zorzi, “Long-Range IoT Technologies: The Dawn of LorRa,” in Future Access Enablers for Ubiquitous and Intelligent Infrastructures, V. Atanasovski and A. Leon-Garcia, Eds., Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, vol. 159, Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, 2015, pp. 51-58.

- Mallik, Avijit. "Man-in-the-middle-attack: Understanding in simple words." Cyberspace: Jurnal Pendidikan Teknologi Informasi 2.2 (2019): 109-134. [CrossRef]

- G. Nath Nayak and S. Ghosh Samaddar, "Different flavours of Man-In-The-Middle attack, consequences and feasible solutions," 2010 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology, Chengdu, China, 2010, pp. 491-495. [CrossRef]

- S. Heinrich, Public Key Infrastructure based on Authentication of Media Attestments. arXiv:1311.7182.

- B. Bhushan, G. Sahoo and A. K. Rai, "Man-in-the-middle attack in wireless and computer networking — A review," 2017 3rd International Conference on Advances in Computing,Communication & Automation (ICACCA) (Fall), Dehradun, India, 2017, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Diro, H. Reda, N. Chilamkurti, A. Mahmood, N. Zaman and Y. Nam, "Lightweight Authenticated-Encryption Scheme for Internet of Things Based on Publish-Subscribe Communication," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 60539-60551, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, J. Bonneau, E. Felten, A. Miller, and S. Goldfeder, "Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Comprehensive Introduction.".

- R. Zhang, R. Xue, and L. Liu, "Security and Privacy on Blockchain," ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 52, no. 3, Article No. 51, pp. 1-34, 2019. [CrossRef]

- LoRaWAN Part 1: How to Get 15 km Wireless and 10-Year Battery Life for IoT [online] Available: https://www.digikey.com/en/articles/lorawan-part-1-15-km wireless-10-year-battery-life-iot.

- Using LoRaWAN and The Things Network with Feather [online] Available: https://learn.adafruit.com/the-things-network-for feather.

- Frequency Plans [online] Available: https://www.thethingsnetwork.org/docs/lorawan/frequency plans/index.html [19] LoRa and LoRaWAN: Techincal overview | DEVELOPER PORTAL [online] Available: https://lora developers.semtech.com/library/tech-papers-and-guides/lora-and lorawan.

- Khalifeh A, Mazunga F, Nechibvute A, Nyambo BM. Microcontroller Unit-Based Wireless Sensor Network Nodes: A Review. Sensors. 2022; 22(22):8937. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Merkle, “A Digital Signature Based on a Conventional Encryption Function,” Advances in Cryptology, CRYPTO ’87. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 293. 1987.

- D. Koo, Y. Shin, J. Yun, and J. Hur, “Improving Security and Reliability in Merkle Tree-Based Online Data Authentication with Leakage Resilience,” Applied Sciences, vol. 8, no. 12, p. 2532, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Ramkumar, "Scalable Computing in a Blockchain," 2018 IEEE 39th Sarnoff Symposium, Newark, NJ, USA, 2018, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).