Highlights

Developed a novel solar-powered corona dielectric barrier discharge (cDBD) microreactor for sustainable agriculture.

cDBD microreactor lowers pH and elevates ORP, nitrite, and nitrate levels in PAW.

PAW treatment doubled spinach seedling growth and can increase germination rates by 135%.

PAW modulates germination-related hormones to enhance aged seed rejuvenation and growth.

1. Introduction

Seed germination is of the utmost significance for seed banks and breeding institutions. It serves as a vital indicator of seed health and viability within their collections, ensuring the preservation of genetic diversity among plant species. Regular assessments of the germination process are necessary to ensure the maintenance of genetic integrity and to build a robust repository that accurately reflects the original diversity of these plant species. Breeding institutions heavily rely on successful germination to develop superior crop varieties, as it allows breeders to select and advance seeds with desired genetic traits, ensuring these traits are expressed in future plant generations[

1]. In addition, the germination process is also a key factor in adaptive breeding for climate resilience[

2]. Both seed banks and breeding institutions prioritize seeds with higher germination rates, as these are often more adaptable to environmental stresses. This selection is crucial for developing crop varieties that are resilient to changing climatic conditions and enhancing agricultural sustainability in diverse ecological settings[

3]. Lastly, in seed banks dedicated to endangered species, the germination success of stored seeds is pivotal for both conservation and species restoration programs[

4]. The capacity to achieve germination in these rare genotypes is essential for maintaining genetic diversity and is integral to reintroducing these species in their native habitats. In summary, the successful germination of seeds during storage plays a pivotal role in genetic conservation, breeding advancements, climate resilience, and the restoration of endangered plant species, and thus it is indispensable for enhancing the long-term sustainability and adaptability of seed banks and breeding institutions.

Seed longevity varies significantly among species. While some seeds retain their vitality for centuries, others deteriorate within a few years. Despite optimal storage conditions designed to prolong germplasm viability, seed vitality inevitably declines over time. This decrease in germination is attributed to various factors. As seeds age, they suffer from viability loss, degradation of genetic material, moisture content fluctuations, and sometimes less-than-ideal storage environments[

5]. The physical and metabolic changes in seeds, coupled with the buildup of germination-inhibiting substances, also lead to lower germination rates[

6]. Additionally, factors such as respiration, susceptibility to diseases, oxidative stress, and alterations in the seed coat further diminish the germination potential of aging seeds[

7]. Therefore, developing methods to rejuvenate aged seeds and enhance their germination rates is not just about preserving genetic diversity; it is also crucial for maintaining a resilient and diverse germplasm repository, which is vital for fostering sustainable agriculture and ensuring food security amidst evolving environmental challenges.

Various methods such as gamma radiation[

8], ultrasound [

9], cold stratification[

10], scarification[

11], hormonal treatments[

12], biostimulants[

13], environmental control[

14], and salt solution pretreatment[

15] can enhance seed germination. However, these techniques often face limitations like high labor and cost, the need for specific conditions, or inconsistent results across different seed types. These constraints make them less universally applicable in agriculture. Recent research has highlighted the potential of non-thermal plasma-treated water in significantly enhancing seed germination rates and boosting overall health and vigor of seedlings. However, the implementation of non-thermal plasma (NTP) technology also presents some limitations, particularly regarding energy consumption and equipment costs. This high energy requirement poses challenges to its widespread application, especially in settings with limited resources. Furthermore, while plasma-activated water (PAW) has shown promise in general seed germination, there is a notable gap in research specifically focusing on its effects on improving the germination rates of aged seeds.

Spinach is not only a vital economic vegetable crop but also a powerhouse of nutrients and health-promoting compounds, making it an indispensable part of the human diet. In 2022, the United States produced 8,417,300 hundredweight (CWT) of spinach[

16], maintaining its position as the world's second-largest producer of this leafy green, underlining its significant role in both the agricultural economy and public health. This substantial production highlights the crucial role spinach plays in the agricultural economy and its significant contributions to public health. However, the rapid aging of spinach, characterized by a seed viability ranging from 2 to 5 years, poses challenges for storage and longevity. Old seeds are likely to produce less vigorous plants, with both the germination rate and plant vigor potentially declining. This means that even if old seeds manage to sprout, the resulting seedlings may exhibit slower or spindlier growth. Additionally, plants that do reach maturity could be less productive or yield less fruit, leading to significant economic losses.

To address these challenges, this study employs a low-cost plasma generation device outlined in our previously research[

17], and now innovatively paired with a solar cell for energy storage. In this study, various parameters of the PAW under different conditions were discussed, including pH, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), nitrite (NO2-) and nitrate (NO3-). Additionally, the applied voltage and plasma treatment duration were optimized to achieve the highest seed germination rate. Moreover, this research investigated the detailed mechanisms behind the generation of reactive species in PAW and illustrated how these influence germination at the molecular level. This comprehensive analysis sheds light on the system's operational efficiency and increases the understanding of seed germination enhancement processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

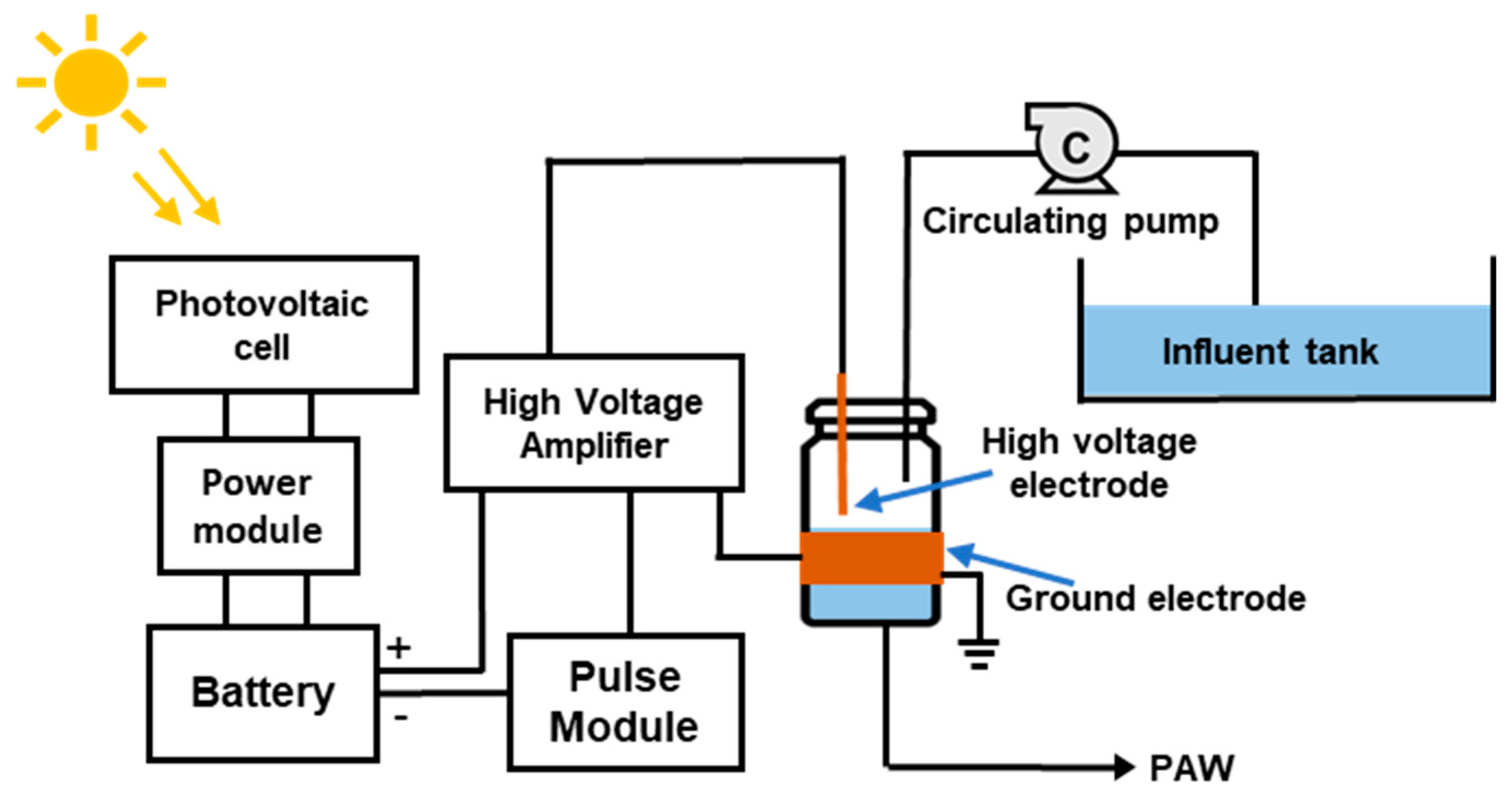

The schematic of the NTP discharger is shown in

Figure 1. The experimental reactor was assembled using a 20 mL glass vial as the main body, with an external diameter of 28 mm and a working volume of 12 mL . An 18-gauge copper wire was employed as the high voltage electrode, whereas the ground electrode was a copper tape, 0.1 mm in thickness and 0.5 inches in length, and was wound around the exterior of the glass vial. The gap facilitating electrical discharge between these electrodes was meticulously maintained at 1 mm. A 30W solar panel was used for power generation and a 40 Ah lithium polymer battery was employed as a power bank to provide electricity during periods of insufficient sunlight. The voltage applied to the reactor was carefully regulated through the adjustment of input voltage from 3 V to 6 V, which was then amplified to a range of 17 to 27 kV by a Tesla coil (high voltage amplifier). A working frequency of 0.3 Hz, along with a 50% duty cycle, was employed in the power module to ensure stable output and minimize internal heat generation.

2.2. Seeds and PAW Preparation

The spinach (Spinacia oleracea; breeding line: “08-280”) seeds used in this study were provided by the Vegetable Research Station of University of Arkansas (3810 Thornhill Street, Alma, AR 72921), which had been stored at 4°C in a cooling room for 23 years. Prior to the main experiment, the seeds were disinfected by soaking in the ethanol solution (~90%) for one minute and then washed with deionized water. After surface sterilization, the seeds were immersed in the PAW of different experimental condition for 12 hours to induce germination. Only seeds that appeared intact were selected, ensuring that any visibly broken, crushed, or infected seeds were excluded from the experiments. For the germination experiments, a petri dish measuring 100 mm in diameter and 15 mm in height was utilized. The base of each dish was covered with Whatman filter paper. Each dish was then filled with 2 mL of treated or untreated tap water sown with 30 spinach seeds each. Equivalent volumes (2 mL) of plasma-treated or untreated water were added to the corresponding petri dish daily to compensate for any evaporation loss that occurred.

For PAW preparation, the tap water was exposed to plasma under atmosphere conditions for various durations, e.g., 17 kV for 5, 10, and 15minutes (PAW17-5, PAW17-10, and PAW17-15). Additionally, the plasma was generated at 17 kV, 22 kV, and 27 kV, each lasting for 10 minutes (PAW17-10, PAW22-10, and PAW27-10). The PAW was used immediately after activation and 15 repetitions were conducted (a total of 450 seeds).

2.3. Analytical Methods

The germination experiments were carried out in triplicates for each voltage and duration combination. Results from these trials were presented with a mean value accompanied by its standard deviation. The seed germination rate and shoot and root length (SRL) were recorded every day after sowing. The germination rate (GR) was calculated using equation 1.

where

is the number of seed germinated at day “i”, N is the total number of seeds.

Nitrite and nitrate were measured using Hach vials (TNT 822 and TNT 872, Hach Company, Loveland, CO, USA) with a Hach DR 3900 spectrophotometer according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The ORP was measured using an EZO-ORP kit from Atlas Scientific (NY, USA), and the pH of the solution was determined using a PHS-25 digital-display pH meter (XL 600, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA). Since the pH measurements conducted immediately after the activation of PAW could be affected by the elevated temperature, leading to the enhanced ion mobility and the increased molecular dissociation[

18], a mandatory recalibration process was performed using the Nernst's equation below:

where F is the Faraday constant and R is the universal gas constant. The standard potential (E

0) and the coefficient are estimated using a two-point calibration in buffer solutions at pH levels of 4.01 and 7.00. T-tests were employed to compare the germination rates between PAW and tap water groups and the

p-value was used to assess statistical significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physiochemical Properties of PAW

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the pH, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), nitrite (NO

2-) and nitrate (NO

3- ) content of the tap water (control) and PAW treated solution at different times at 17 kV and different voltages for 10 min. Overall, the pH decreased with longer treatment times and higher plasma discharge voltages, while the ORP, nitrite, and nitrate levels increased correspondingly. Additionally, the impact of voltage on these parameters was more substantial than that of treatment time, suggesting a greater effect of voltage on pH, ORP, nitrite, and nitrate levels.

The pH level of the environment in which a seed germinates plays a crucial role in determining its germination success. Most seeds prefer a slightly acidic to neutral pH for optimal enzyme activity. Enzymes essential for breaking down food reserves in the seed are pH-sensitive, requiring an optimal pH level for efficient operation. Highly acidic environments hinder these enzymes' synthesis and activity, compromise seed coat integrity through dissolution or pathogen-induced perforation, and impede essential biochemical pathways[

19]. According to Jensen et al.[

20], the majority of plants thrive best in a neutral pH range of from 6.5 to 7.5, which is considered optimal for plant root development. However, low pH conditions can significantly impede seed germination by damaging to the seed coat, adversely affecting enzymatic activities essential for seed growth, increasing concentrations of toxic metal ions, disrupting the balance of soil microbial communities, and cause hormonal imbalances in seeds. Therefore, the pH reduction caused by NTP dischargers can be detrimental. To address this, modifying the NTP discharger to minimize acid production is crucial, involving optimization of operating voltage and frequency, use of inert gases as feedstock, and careful control of treatment duration and environmental conditions. Compared with other studies where pH levels drop to 3 within minutes, this study revealed a relatively similar hydroxide ion concentration, calculated using the ionic product (Kw). Only minor decreases were observed in pH (from 7.37 in the control to 7.18 and 6.86 in the PAW17-15 and PAW27-10 samples, respectively). This result is similar to Judee et al.'s findings regarding stable pH levels after plasma treatment, with some minor variations that could be due to differences in the setup of the plasma device[

21].

The oxidizing and reducing capabilities of the solutions were assessed using their ORPs, which increased with the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) by the NTP discharger. While these reactive species can be beneficial at certain levels, excessively high ORP levels can induce oxidative stress, potentially damaging the cellular structures of seeds and consequently inhibiting or delaying germination [

22]. In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) has established a standard for drinking water, where an ORP value of 650 mV is considered sufficient for immediate bacterial disinfection [

23]. This standard implies that while higher ORP levels are effective for disinfection, moderate ORP values are generally preferable for processes like seed germination to avoid the negative effects of excessive oxidative stress.

Both nitrite and nitrate play pivotal roles in enhancing seed germination. As outlined by Hendricks and Taylorson[

24], the measured enzymatic activities and the observed sensitivity of hemoproteins to inhibition by various compounds suggest that nitrites enhance seed germination through the inhibition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) breakdown by catalase. Concurrently, nitrate at low concentrations acts as both a nutrient and a signaling molecule, undergoing assimilation first into nitrite and then into ammonium, a crucial step for amino acid synthesis [

25]. This dual function underscores the significance of nitrite and nitrate and those two can also be adjusted through controlling operational parameters of NTP dischargers. It is found that higher voltage settings are more conducive to the formation of nitrates than nitrites, indicating an optimization factor for PAW preparation. For example, the nitrate content in PAW generated at 27 kV for 10 minutes (13.5 mg·L

−1) doubled that in PAW produced at 17 kV for 15 minutes (6.45 mg·L

−1). This suggests that the operational parameters of NTP dischargers are crucial and that a higher voltage tends to favor the accumulation of desirable nitrate levels in PAW. Moreover, higher nitrate levels compared to nitrites in PAW are likely due to ozone-induced nitrite-to-nitrate conversion[

21]. This observation aligns with a study by Liu et al.[

26], which attributed 90 percent of nitrite reduction in PAW to excess ozone.

3.2. Seed Germination Performances

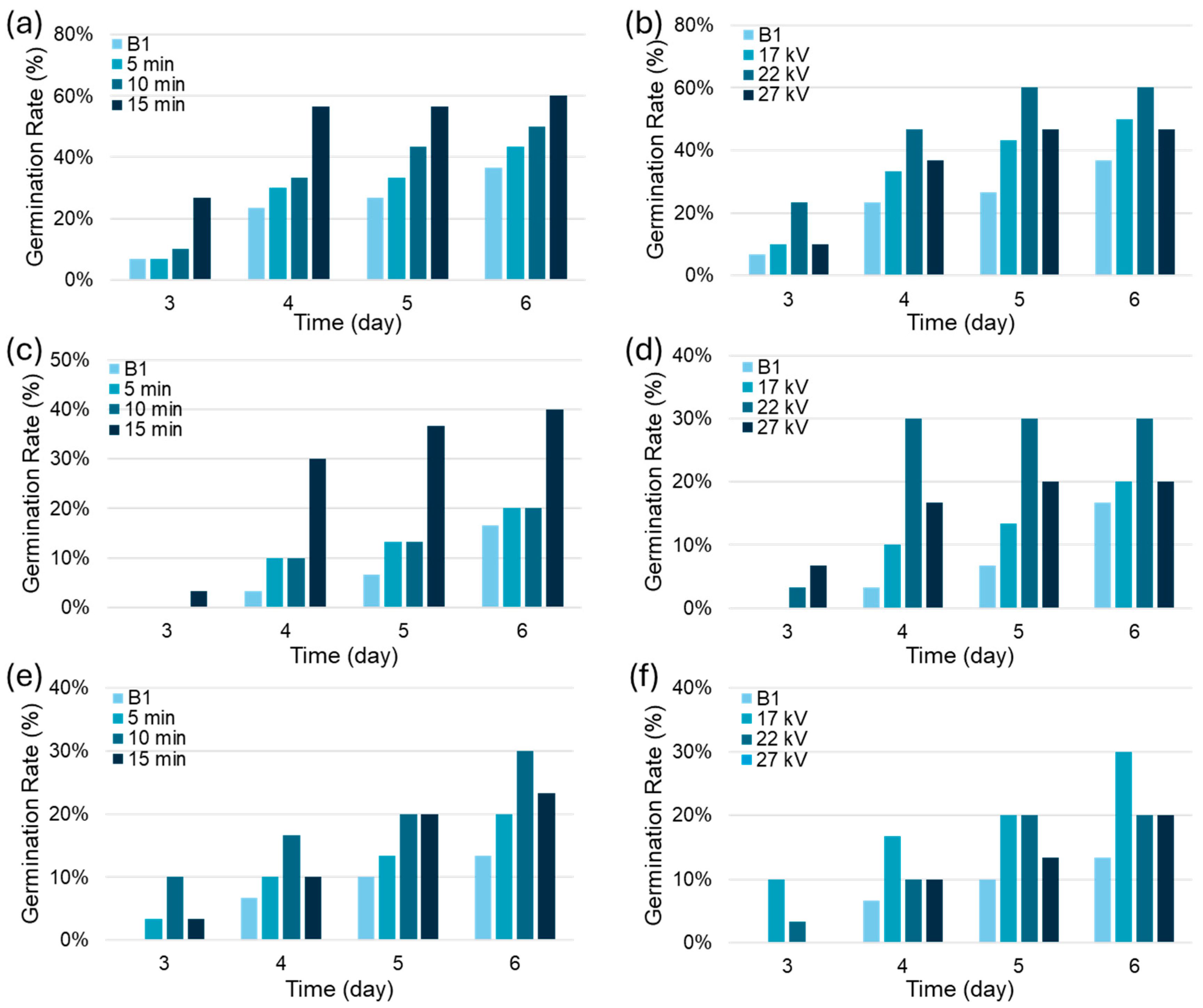

The germination rate of spinach seeds is significantly influenced by both the voltage and the treatment duration of the NTP discharger, with all PAW treatments surpassing the performance of the control group that was treated with tap water only. Specifically, a distinct trend where longer exposure times generally lead to an improvement in the rate of germination over the control. Furthermore, while the control group for strains 08-415 and F415 showed no germination on day 3 (as depicted in

Figure 2(c) and (e)), seeds began to germinate following PAW treatment at 17 kV for 15 minutes in 08-415, and for 5, 10, and 15 minutes in F415. However, while strains 08-280 and 08-415 show increased germination rates with prolonged PAW treatment at 17 kV, as evidenced in

Figure 2(a) and (c), with optimal rates achieved at 15 minutes reaching 60% and 40% respectively, strain F415 deviates from this trend. As depicted in

Figure 2(e), F415 attains its highest germination rate of 30% at a shorter PAW exposure of 10 minutes at 17 kV. This variation suggests that different seed strains have specific optimal germination conditions, likely due to their unique nutritional requirements or differential responses to PAW treatment. By day 6, it was observed that the germination rates for seeds treated with PAW peaked at 60% for 08-280 (PAW17-15), 40% for 08-415 (PAW17-15), and 30% for F415 (PAW17-10). These represent substantial improvements over the control groups, showing an increase of approximately 62% for 08-280, 135% for 08-415, and 130% for F415 against control germination rates of 37%, 17%, and 13%, respectively. The effectiveness of PAW in enhancing germination is further substantiated by the notably low p-values derived from the t-test, all of which are well below the 0.01 threshold, indicating a statistically significant improvement in germination rates attributable to PAW treatment.

The germination rates of spinach seeds were also significantly influenced by the voltage applied during PAW treatment, with PAW22-10 achieving a 60% germination rate for strain 08-280 (

Figure 2(b)) and a 33% rate for 08-415 (

Figure 2(d)), while PAW17-10 resulted in a 30% rate for F415 (

Figure 2(f)). These differences can be attributed to the optimal generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) at specific NTP discharger voltages. These reactive species are crucial for stimulating germination without the negative effects that come with higher voltages, such as more ROS and lower pH, which can lead to seed surface erosion or an excessive buildup of reactive species. This underscores the importance of finding a balanced approach to PAW treatment that considers both voltage and duration to maximize benefits across various seed strains.

Notably, the impact of voltage on germination rates aligns with the previously discussed effects of treatment duration. As treatment time increases or voltage rises, parameters such as pH, ORP, and concentrations of NO2- and NO3- tend to decrease, affecting seed germination. Accordingly, the optimal germination rates observed with extended PAW treatment — 60% for 08-280 (PAW17-15), 40% for 08-415 (PAW17-15), and 30% for F415 (PAW17-10) — are consistent with the patterns seen with voltage adjustments, where PAW22-10 treatment yields similarly high germination rates for strains 08-280 and 08-415, and PAW17-10 does so for F415. This coherence between the effects of treatment duration and voltage emphasizes the complex interplay between these factors and their collective influence on the efficacy of PAW treatment in promoting seed germination.

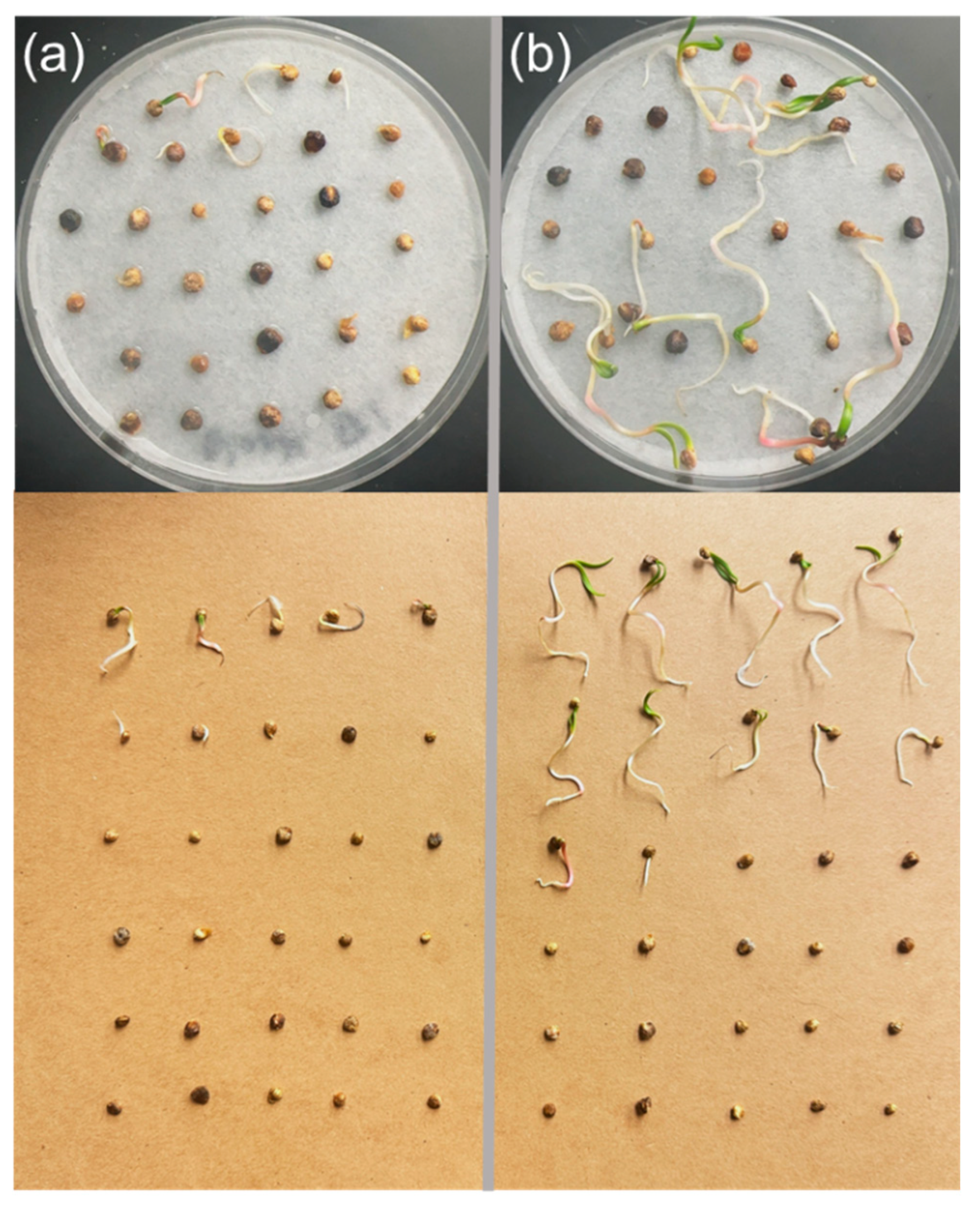

At the end of the germination phase, a representative petri dish from control and PAW17-5 was shown in Figure 3. It is obvious that the seedlings from the PAW17-5 treatment exhibit not only a higher germination rate but also a markedly more vigorous (max length: 5.8 cm) early growth compared to the control group (max length: 2.6 cm). The

p-values indicated a significant difference in germination rates between PAW treatment and un-treated seeds. This is particularly noteworthy given the seeds' advanced age of 23 years, for which the germination rate was previously less than 20%. The PAW treatment has evidently resulted in more robust and healthy seedlings. It is possible that nitrates generated during plasma activation served as an alternative source of nitrogen that enhances plant growth. Similar phenomena have been reported by Takaki et al.[

27], who reported that PAW significantly boosted the growth of

Brassica rapa var. perviridis over 28 days, with plants in 20-minute treated PAW reaching 90 mm, over twice the height of the 40 mm control group, suggesting that PAW's reactive nitrogen species functioned as an effective fertilizer. Similarly, Judée et al. [

21] found that PAW irrigation increased lentil seedling lengths by 34.0% and 128.4% after 3 and 6 days, respectively, compared to untreated water, with other studies reporting comparable effects. The consistent observations across various studies underscore the potential of PAW as a sustainable enhancer for plant growth, where it compensates for diminished natural germination rates by providing a vital nutrient boost through reactive nitrogen species.

Figure 4.

Photographs of spinach (08-280) germination and seedling growth after 7th day of sowing for (a) control, and (b) PAW-17-5.

Figure 4.

Photographs of spinach (08-280) germination and seedling growth after 7th day of sowing for (a) control, and (b) PAW-17-5.

3.3. Mechanisms

Despite the challenges associated with analyzing the chemical processes of plasma interactions with tap water, which vary in salt concentrations and organic impurities, the primary mechanism of our solar-powered plasma device for seed germination remains clear and well-defined. This mechanism involves the generation of reactive species through non-thermal plasma (NTP). This process starts with electron collisions with neutral molecules, leading to the formation of primary reactive species such as ionized and excited molecules, atomic nitrogen, and oxygen (Eq. 3-4). These species rapidly evolve into secondary reactive species including H

2O

2, nitric oxide (NO), and ozone (O

3) (Eq 5-10), which would dissolve into the liquid phase to become a more stable form (Eq 11-13). These stable species, which include O

3, H

2O

2, NO

2−, NO

3−, and peroxynitrite (ONOO

-) and have a longer lifespan (ranging from milliseconds to several days), play a crucial role in enhancing seed germination as discussed below.

PAW can improve seed germination rates by increasing the surface wettability of the seeds[

28], killing bacteria and pathogens present on the seed surface [

29], softening the seed coat, and stimulating the growth of hypocotyl and radicle [

30] This enhanced germination and growth from PAW treatment can be further understood by examining its impact on the fundamental stages of seed development. The germination process involves two critical phases: the primary cell elongation in the axial part of the embryo, and cell division, either simultaneous or delayed, in the radicle meristem [

31]. Research indicates that both critical phases can be influenced by PAW through the modulation of gibberellins (GA), abscisic acid (ABA), and catalase (CAT). GA plays a major role in the primary cell elongation phase, essential for breaking seed dormancy and initiating growth by stimulating cell elongation within the embryo[

32]. In contrast, ABA generally acts to maintain seed dormancy and inhibit germination, regulating stress responses to prevent premature germination under unfavorable conditions[

33]. Meanwhile, CAT activity becomes particularly relevant during the cell division phase in the radicle meristem, where it helps manage oxidative stress, crucial for protecting actively dividing cells and supporting healthy seedling development[

34].

Based on this understanding, the role of ROS and RNS in several signaling pathways involved in the seed germination was investigated. First, ROS and RNS could modulate ABA and GA transduction pathways and help in controlling numerous transcription factors and altering the properties of specific proteins through carbonylation[

35]. For example, Grainge et al. [

36] reported that PAW could facilitate the release of physiological seed dormancy in Arabidopsis thaliana through a synergistic interaction between plasma-generated reactive species (NO

3−, H

2O

2 ·NO, and ·OH) and signaling pathways that target GA and ABA metabolism. This interaction also alters the expression of genes responsible for cell wall remodeling, vital for germination. To be more specific, they found that when the seeds were treated with air-PAW, there was an early up-regulation of genes like GA3OX1 (involved in bioactive GA biosynthesis) and CYP707A2 (ABA degradation), along with the downregulation of NCED2 and NCED9 (ABA biosynthesis). In addition, PAW treatment could also enhance the CAT activity in the roots of the grown plants[

37]. This increased CAT activity contributed to the upregulation of various physiological processes, resulting in improved germination, growth, and overall development of the target seeds. Similar research has been conducted by Puač et al.[

38], who found that the presence of H2O2 in PAW was important in activating the CAT genes in seeds. This activation leads to the synthesis of new proteins, which was observed to significantly enhance the germination of Paulownia tomentosa seeds. Those reactive species in PAW can actually be generated and released by mitochondria within the cell, which are regarded as the primary sites of production[

39]. It has been found that RNS are more effective in stimulating the germination rate at higher concentrations, while an increase in ROS levels is associated with longer shoot growth. Thus, the presence of additional reactive species present in PAW could significantly boost the seed germination rate[

40].

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

This study addressed the prevalent issue of declining germination rates in aged seeds, a common problem in agriculture. A new, solar-powered corona dielectric barrier discharge (cDBD) microreactor has been developed, capable of generating plasma-activated water efficiently and in an environmentally sustainable manner. Physicochemical analysis revealed that longer treatment times and higher voltages decreased pH and increased ORP, nitrite, and nitrate levels in the PAW. The optimal PAW treatment (PAW17-15), applied to 23-year-old spinach seeds (strain 08-15), led to a remarkable 135% increase in germination rates compared to the control group. This study also detailed the changes in physicochemical properties of PAW and their effects on seeds at a molecular level, demonstrating how PAW treatment not only improved germination by modulating gibberellins and abscisic acid but also enhanced early seedling growth through increased catalase activity.

These findings underscore the effectiveness of this solar-powered cDBD microreactor in enhancing the viability of aged seeds, offering a sustainable and cost-effective solution to support global agricultural food production. The technology also serves as an on-site tool for farmers, promoting the adoption of more resilient agricultural practices. However, while PAW has proven to enhance seed germination by modifying seed surface properties and facilitating the formation of reactive species that break seed dormancy, the complex interactions between plasma-activated water, seed germination, and plant growth remain incompletely understood. The variability in plant species, growth phases, and environmental conditions can significantly influence the outcomes of plasma treatments. Moreover, scaling these plasma devices for large-scale agricultural operations presents challenges due to unexplored effects on different seed types across various conditions, impacting the consistency and reliability of results. Additionally, the long-term impacts of plasma-treated seeds on crop yield and quality need further evaluation to ensure farmer adoption. Further research and development are essential to address these limitations, enhancing the feasibility of plasma technology in agriculture and providing a more comprehensive understanding of its benefits and constraints.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Arkansas Agriculture Experiment Station of the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture and the Center for Agricultural and Rural Sustainability (Hatch project: ARK02604).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Yiting Xiao, Yang Tian, Haizheng Xiong, Ainong Shi, and Jun Zhu declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial conflicts to disclose.

References

- Ahmar, S.; Gill, R.A.; Jung, K.-H.; Faheem, A.; Qasim, M.U.; Mubeen, M.; Zhou, W. Conventional and Molecular Techniques from Simple Breeding to Speed Breeding in Crop Plants: Recent Advances and Future Outlook. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2590. [CrossRef]

- Singh R P, Prasad P V V, Reddy K R. Chapter Two - Climate Change: Implications for Stakeholders in Genetic Resources and Seed Sector. In: Sparks D L, ed. Advances in Agronomy. Vol 129. Academic Press, 2015, 117–180.

- Lin B B. Resilience in Agriculture through Crop Diversification: Adaptive Management for Environmental Change. BioScience, 2011, 61(3): 183–193.

- Walker T, Harris S A, Dixon K W. Plant conservation. In: Key Topics in Conservation Biology 2. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013, 313–326.

- Gough R E. Seed Quality: Basic Mechanisms and Agricultural Implications. CRC Press, 2020 Google-Books-ID: TEMPEAAAQBAJ.

- Chenyin, P.; Yu, W.; Fenghou, S.; Yongbao, S. Review of the Current Research Progress of Seed Germination Inhibitors. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 462. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Li, Y.-F.; Klämpfl, T.G.; Shimizu, T.; Jeon, J.; Morfill, G.E.; Zimmermann, J.L. Inactivation of Surface-Borne Microorganisms and Increased Germination of Seed Specimen by Cold Atmospheric Plasma. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 645–653. [CrossRef]

- Beyaz, R.; Kahramanogullari, C.T.; Yildiz, C.; Darcin, E.S.; Yildiz, M. The effect of gamma radiation on seed germination and seedling growth of Lathyrus chrysanthus Boiss. under in vitro conditions. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016, 162-163, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Miano, A.C.; Forti, V.A.; Abud, H.F.; Gomes-Junior, F.G.; Cicero, S.M.; Augusto, P.E.D. Effect of ultrasound technology on barley seed germination and vigour. Seed Sci. Technol. 2015, 43, 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, W.; Rave, G. The effect of cold stratification and light on the seed germination of temperate sedges (Carex) from various habitats and implications for regenerative strategies. Plant Ecol. 1999, 144, 215–230. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Sánchez, E.; Lindig-Cisneros, R. Effect of scarification and growing media on seed germination of Lupinus elegans H.B.K.. Seed Sci. Technol. 2005, 33, 237–241. [CrossRef]

- Kucera, B.; Cohn, M.A.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Plant hormone interactions during seed dormancy release and germination. Seed Sci. Res. 2005, 15, 281–307. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Doležal, K.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Balázs, E.; Van Staden, J. Role of non-microbial biostimulants in regulation of seed germination and seedling establishment. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 97, 271–313. [CrossRef]

- Hazebroek J P, Metzger J D. Environmental Control of Seed Germination in Thlaspi Arvense (cruciferae). American Journal of Botany, 1990, 77(7): 945–953.

- Ashraf M, Foolad M R. Pre-Sowing Seed Treatment—A Shotgun Approach to Improve Germination, Plant Growth, and Crop Yield Under Saline and Non-Saline Conditions. In: Advances in Agronomy. Vol 88. Academic Press, 2005, 223–271.

- USDA. Vegetables 2022 Summary 02/15/2023. 2022.

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zhu, J. Optimization of a Low-Cost Corona Dielectric-Barrier Discharge Plasma Wastewater Treatment System through Central Composite Design/Response Surface Methodology with Mechanistic and Efficiency Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 605. [CrossRef]

- Ashton J, Geary L. The effects of temperature on pH measurement. Tsp, 2011, 1(2): 1–7.

- Vleeshouwers, L.M.; Bouwmeester, H.J.; Karssen, C.M. Redefining Seed Dormancy: An Attempt to Integrate Physiology and Ecology. J. Ecol. 1995, 83, 1031. [CrossRef]

- Jensen T L, Thomas L. Soil pH and the availability of plant nutrients. IPNI Plant Nutrition Today, 2010, 2.

- Judée, F.; Simon, S.; Bailly, C.; Dufour, T. Plasma-activation of tap water using DBD for agronomy applications: Identification and quantification of long lifetime chemical species and production/consumption mechanisms. Water Res. 2018, 133, 47–59. [CrossRef]

- Sivachandiran, L.; Khacef, A. Enhanced seed germination and plant growth by atmospheric pressure cold air plasma: combined effect of seed and water treatment. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 1822–1832. [CrossRef]

- McFerson L. Understanding ORP’s role in the disinfection process. Water Eng. Management, 1993, 140: 29–31.

- Hendricks, S.B.; Taylorson, R.B. Promotion of Seed Germination by Nitrate, Nitrite, Hydroxylamine, and Ammonium Salts. Plant Physiol. 1974, 54, 304–309. [CrossRef]

- Duermeyer, L.; Khodapanahi, E.; Yan, D.; Krapp, A.; Rothstein, S.J.; Nambara, E. Regulation of seed dormancy and germination by nitrate. Seed Sci. Res. 2018, 28, 150–157. [CrossRef]

- Liu D X, Liu Z C, Chen C, Yang A J, Li D, Rong M Z, Chen H L, Kong M G. Aqueous reactive species induced by a surface air discharge: Heterogeneous mass transfer and liquid chemistry pathways. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 23737.

- Takaki, K.; Takahata, J.; Watanabe, S.; Satta, N.; Yamada, O.; Fujio, T.; Sasaki, Y. Improvements in plant growth rate using underwater discharge. J. Physics: Conf. Ser. 2013, 418, 012140. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, V.; Tiwari, B.S.; Nema, S.K. Treatment of Pea Seeds with Plasma Activated Water to Enhance Germination, Plant Growth, and Plant Composition. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2021, 42, 109–129. [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.S.; Hardy, G.E.S.J.; Bayliss, K.L. Cold plasma: a potential new method to manage postharvest diseases caused by fungal plant pathogens. Plant Pathol. 2017, 67, 1011–1021. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Yang, S.; Bazaka, K.; Ostrikov, K. Effects of Atmospheric-Pressure N2, He, Air, and O2 Microplasmas on Mung Bean Seed Germination and Seedling Growth. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32603. [CrossRef]

- Šírová, J.; Sedlářová, M.; Piterková, J.; Luhová, L.; Petřivalský, M. The role of nitric oxide in the germination of plant seeds and pollen. Plant Sci. 2011, 181, 560–572. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L. Gibberellins: Their Physiological Role. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1973, 24, 571–598. [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Qanmber, G.; Li, F.; Wang, Z. Updated role of ABA in seed maturation, dormancy, and germination. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 35, 199–214. [CrossRef]

- Considine, M.J.; Foyer, C.H. Redox Regulation of Plant Development. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2014, 21, 1305–1326. [CrossRef]

- El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H.; Bailly, C. Oxidative signaling in seed germination and dormancy. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Grainge, G.; Nakabayashi, K.; Steinbrecher, T.; Kennedy, S.; Ren, J.; Iza, F.; Leubner-Metzger, G. Molecular mechanisms of seed dormancy release by gas plasma-activated water technology. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 4065–4078. [CrossRef]

- Sajib S A, Billah M, Mahmud S, Miah M, Hossain F, Omar F B, Roy N C, Hoque K M F, Talukder M R, Kabir A H, Reza M A. Plasma activated water: the next generation eco-friendly stimulant for enhancing plant seed germination, vigor and increased enzyme activity, a study on black gram (Vigna mungo L.). Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing, 2020, 40(1): 119–143.

- Puač, N.; Škoro, N.; Spasić, K.; Živković, S.; Milutinović, M.; Malović, G.; Petrović, Z.L. Activity of catalase enzyme in Paulownia tomentosa seeds during the process of germination after treatments with low pressure plasma and plasma activated water. Plasma Process. Polym. 2017, 15. [CrossRef]

- Møller, I.M.; Jensen, P.E.; Hansson, A. Oxidative Modifications to Cellular Components in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007, 58, 459–481. [CrossRef]

- Thirumdas, R.; Kothakota, A.; Annapure, U.; Siliveru, K.; Blundell, R.; Gatt, R.; Valdramidis, V.P. Plasma activated water (PAW): Chemistry, physico-chemical properties, applications in food and agriculture. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 21–31. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).