1. Introduction

Metagenomic studies, especially in the field of virome, have shown significant growth in recent years due to their advantages investigation of viruses that are inaccessible to classical methods, characterizing viral diversity in various environments, detecting of viruses in samples with low viral load, identifying novel strains and study viral evolution. Thus, this led to detailed studies on the human respiratory virome [

1,

2,

3]. It has been demonstrated that one of the ubiquitous members of the human respiratory virome is the enigmatic

Anelloviridae family viruses [

1]. It is presented in up to 90% of individuals and acquired in childhood [

4,

5]. Various transmission routes are described such as vertical, fecal-oral, parenteral, sexual [

6,

7,

8]. With age, the “anellome” (the composition of anello-viruses (AVs) in the body), representing the diversity of AVs within an individual, be-comes stable; however, in childhood, the composition is variable with a predominance of TTMV (Torque teno mini virus) and TTMDV (Torque teno midi virus) [

9,

10].

The

Anelloviridae family comprises 30 genera, four of which are detected in humans:

Alphatorquevirus (Torque teno virus, TTV),

Betatorquevirus (TTMV, previously known as TTV-like Mini virus, TLMV),

Gammatorquevirus (TTMDV), and the recently discovered

Hetorquevirus (Torque teno hominid virus) [

11]. This group includes non-enveloped viruses with single-stranded negative-sense DNA circular genomes ranging in size from 1.6 to 3.9 kb [

5,

11]. AVs exhibit a high degree of heterogeneity among DNA viruses [

9,

12,

13]. It is proposed to consider the species demarcation threshold as nucleotide sequence identity of ORF1 at 31% [

11]. This means that if a new AV shows 69% or higher pairwise similarity with a classified member of the species, it is classified within that species.

While it is not definitively established whether AVs cause diseases, it is currently considered that they are commensal viruses. However, their involvement in the development of a wide range of pathologies, including respiratory infections, hepatitis, multiple sclerosis, lymphoma, autoimmune diseases, and others, is also suspected [

3,

4,

6,

14,

15]. It is reliably noted that an increase in viral load occurs in conditions of compromised immune function (such as HIV/AIDS) [

16,

17], and replication is controlled by the immune system [

18]. Moreover, there is a growing number of studies investigating whether AVs are associated with respiratory diseases [

1,

6,

8,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. In this study, we employed viral metagenomics to investigate the presence, diversity, phylogenetic relationship of AVs among pediatric patients exhibiting acute respiratory symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal Research Center for Fundamental and Translational Medicine. Nasal and throat swabs were collected from 1310 pediatric patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms (from October 2022 to May 2023) in Novosibirsk, Russia. Clinical diagnoses and demographic data of patients were taken from medical records. Samples were placed in tubes with transport medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Capricorn Scientific, Ebsdorfergrund, Germany) with 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 100 μg/mL of gentamicin sulfate (BioloT, Saint-Petersburg, Russia), and 50 units/mL of amphotericin B (BioloT, Saint-Petersburg, Russia). Tubes were stored in liquid nitrogen immediately. After transport to the laboratory, all samples were stored at -80 °C for future studies.

2.2. Virus Detection

All samples were tested for the presence of major respiratory viruses. RNA was extracted using the RIBO-sorb kit (Interlabservice, Moscow, Russia). Reverse transcription was performed using the REVERTA-L kit (Interlabservice, Moscow, Russia). The resulting cDNA was used to detect respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV); alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses (HCoV); parainfluenza virus (HPIV); metapneumovirus (HMPV); rhinovirus (HRV); adenovirus (HAdV) and bocavirus (HBoV) using the AmpliSens ARVI-screen-FL kit (Interlabservice, Moscow, Russia).

Detection of influenza virus A, influenza virus B and SARS-CoV-2 was carried out in a one-step real-time PCR reaction using the AmpliPrime Influenza SARS-CoV-2/Flu(A/B/H1pdm09) kit (Nextbio, Moscow, Russia).

2.3. Bacteria Detection

Additionally, bacterial culture for opportunistic and pathogenic organisms (including Acinetobacter baumannii, Candida albicans, Candida lusitaniae, Candida parapsilosis, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxitoca, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Neisseria spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus viridans) was performed in the clinical diagnostics laboratory of the Municipal Children’s Infectious Diseases Hospital, Novosibirsk, Russia. During the microbiological study, the primary sowing of clinical material on nutrient media was carried out, followed by the re-sowing of grown colonies of microorganisms on selective media. The species identification of microorganisms was carried out using the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry method.

Four individual samples from children aged 2-4 years diagnosed with pneumonia or bronchitis were selected for further viral metagenomic analysis. We selected three samples in which respiratory viruses were present as a monoinfection and one sample without respiratory pathogens (for more details, refer to the

Table 1).

2.4. Sample Preparation for Metagenomics

2.4.1. Enrichment of Samples with Virus-Like Particles

The sample preparation for viromic analysis was conducted in accordance to the NetoVIR protocol, with modifications [

24]. Test tubes with transport medium and viscose swabs were mixed using a vortex for 3 minutes. An aliquot of each sample was then transferred to a clean tube and centrifuged for 3 min at 17,000 × g. The supernatant was filtered on a 0.8 μm filter (Sartorius Vivaclear, Göttingen, Germany) for 1 min at 17,000 × g. 20× enzyme buffer was added to the filtrate. Then benzonase and 1 μL of microccocal nuclease were added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The reaction was stopped with 0.2 M EDTA and extraction began immediately.

2.4.2. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription and Amplification of Double-Stranded cDNA

Nucleic acids were extracted using a column-based extraction kit (Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia). Complementary DNA was obtained using Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer-Amplification (SISPA) according to the protocol [

25]. Briefly, first-strand cDNA was prepared using K-8N primer (5’-GACCATCTAGCGACCTCCACNNNNNNNN-3’). To do this, 50 pmol of the K-8N primer was added to the viral RNA and incubated for 2 min at 70°C. Then RT buffer, M-MuLV reverse transcriptase, and water from the M-MuLV-RH kit (Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia) were added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, 42 °C for 60 min and 70 °C for 10 min.

To synthesize the second strand of cDNA, 10x Klenov Bufer, 20 pmol K-8N primer and 250 mM of each dNTP were added to the entire volume of the previous reaction. The reaction mixture was incubated at 95 °C for 3 min. Then cooled to 4 °C, added Klenow fragment (SibEnzyme, Novosibirsk, Russia) and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. The reaction products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

Double-Stranded cDNA (ds-cDNA) amplification was carried out using the Encyclo Plus PCR kit (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia). To 10 μl of ds-cDNA, 5 μl of 10x Encyclo buffer, 1 μl of dNTP mix (10 mM each), 5 μl of K-primer (5’-GACCATCTAGCGACCTCCAC-3’) 100 pmol/μl, 1 μl of 50x Encyclo polymerase mix and 28 μl of water were added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The reaction products were purified by Reaction mixtures DNA isolation kit (Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia) and quantified through a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with a Spectra Q HS Kit (Sesana, Moscow, Russia).

2.5. Library Preparation and Sequencing

Preparation of whole transcriptome libraries was carried out using the KAPA HyperPrep Kit (Roche, Switzerland). Briefly, Briefly, the size of cDNA fragments was assessed using a 4150 TapeStation automated gel electrophoresis platform (Agilent, USA). Then, the terminal sections of the cDNA fragments were repaired and the 3′ ends were adenylated. After this, the adapter was ligated and the target cDNA fragments were selected using KAPA Pure Beads (Roche, Switzerland). Next, the libraries were amplified with indexing primers and target fragments were selected using KAPA Pure Beads (Roche, Switzerland). Finally, the quality and quantity of whole-transcriptome cDNA libraries were assessed on a Qubit 4.0 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) fluorometer using the dsDNA HS kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) and an automatic gel electrophoresis platform 4150 TapeStation (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) using the HS D1000 ScreenTape kit.

Sequencing was performed on the GenoLab M platform (GeneMind, Shenzhen, China). The finished whole transcriptome libraries were diluted to a concentration of 4 nM and pooled according to the operating manual of the GenoLab M sequencing system (GeneMind, Shenzhen, China). The library pool was denatured and diluted to a final concentration of 2.8 pM, and the volume fraction of PhiX in the pool was 1%. Datasets is deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (accession number are available upon request).

2.6. Bioinformatics Processing

Sequencing was conducted on the GenoLab M (GeneMind, Shenzhen, China) platform and approximately 13-17 million 150 bp paired-end reads per sample were achieved. Raw reads were trimmed to remove low-quality bases, ambiguous bases and adapter sequences using Trimmomatic v0.39 [

26]. Trimmed reads have been decontaminated from the human genome using Bowtie2 [

27]. To reduce the deduplication level, we utilized fastp v0.23.4 [

28], Clumpify (from the BBMap v39.06 package [

29]), and FastUniq v1.1 [

30]. These reads were processed using the Virome Paired-End Reads (ViPER) pipeline (

https://github.com/Matthijnssenslab/ViPER). For

de novo assembly, we utilized metaSPAdes v3.15.5 [

31] and filtered the assembled contigs based on coverage (≥10x) and length (≥300 nt). The annotation and classification of the assembled contigs were performed using DIAMOND v2.0.15 [

32] and KronaTools v2.8.1 [

33]. Contigs from

Anelloviridae were filtered out and handled individually. To assemble according to the reference, the contigs of AVs were mapped against the nr/nt database BLAST to obtain the closest full genomic (or complete CDS) sequence, followed by consensus building from the libraries using BWA-MEM [

34], SAMtools [

35]. Sequences (> 400 nt) obtained were analyzed by BLASTn and classified by

Anelloviridae genus. Seven sequences of AVs from phylogenetic analysis are available in GenBank (accession numbers are available upon request).

2.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed based on the complete (or almost complete) amino acid ORF1 sequences of the seven AVs (five TTMVs, two TTMDVs) acquired in this study, their closest relatives based on BLASTx and other representative virus strains. MAFFT v7.520 [

36] was employed for multiple sequence alignment using the mafft-linsi option and a maximum of 100 iterations separately for TTMVs and TTMDVs. Subsequently, the alignments were merged (“--merge”) and trimmed using TrimAl v1.2 with the “--gappyout” option [

37]. Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees were constructed for amino acid dataset using MEGA 11.0 under the best-fit substitution model (GTR + F + G + I) [

38]. Bootstrap with 1,000 samples were performed to assess the robustness of tree topologies.

3. Results

We examined four nasal and throat swabs from children aged 2-4 years with respiratory symptoms from Novosibirsk, Russia, collected between November and December 2022. Three swabs showed the presence of respiratory pathogens, while sample E3 exhibited no detection of either bacterial or viral respiratory pathogens (

Table 1). Despite the absence of major respiratory pathogens, the patient exhibited pneumonia symptoms, fever, malaise, nasal congestion, and cough.

To obtain comprehensive information on the prevalence of viruses in children with respiratory symptoms, a virome study was performed. The metagenomic analysis results were consistent with the qPCR diagnostic data.

3.1. Characteristics of the Obtained Reads and Contigs

Following sequencing, there were 13-17 million reads obtained. After trimming, deduplication, and removal of host reads, there were approximately 2 million reads remaining in samples E1, E2, and E3, and 4 million reads in sample E4 (

Table 2). Through

de novo assembly, we obtained 967 contigs in E1, 497 in E2, 944 in E3, and 962 in E4. Among these, 3, 1, 25, and 4 contigs belonged to AVs in each respective sample. After reference-based assembly using these contigs, we obtained 13 sequences of AVs (length 1,165-2,832 nt). In addition, 3 contigs (1 from E1, 2 from E4) remained unchanged in the attempt to assemble them based on the reference. Thus, a total of 16 unique sequences of AVs were obtained, 8 of which were > 2,000 nt (1 each in E1, E2 and 6 in E3), and 8 were < 2,000 nt (2 in E1, 2 in E3, and 4 in E4).

3.2. Prevalence of Viral Families by Samples

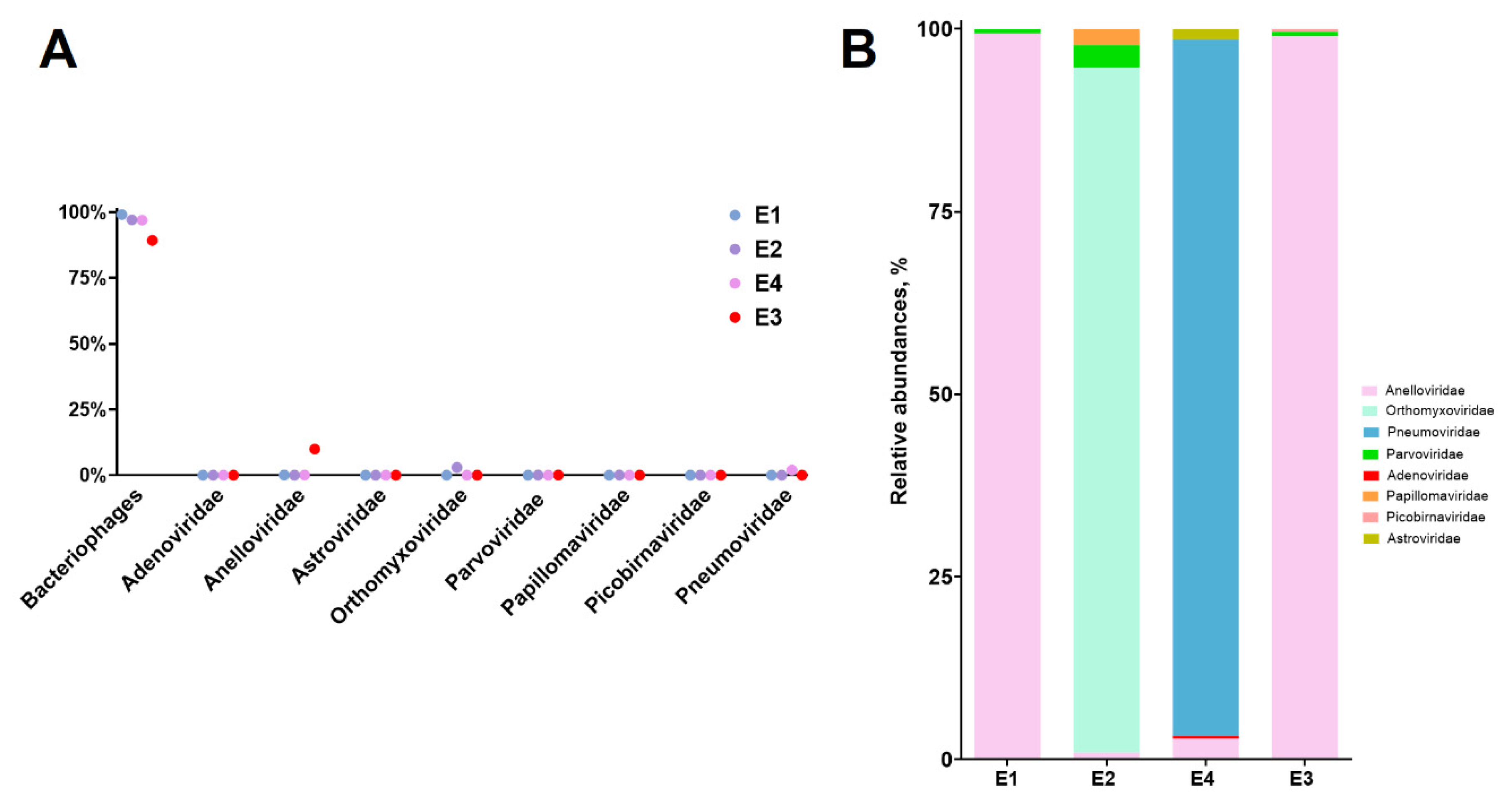

The prevailing number of viral reads were assigned to bacteriophages (

Caudoviricetes, Crassvirales, Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, Inoviridae, Podoviridae, Herelleviridae), comprising 97-99% in PCR-positive samples (E1, E2, E4) and 89% in PCR-negative sample (E3) (

Figure 1A). Among eukaryotic viruses (excluding bacteriophages), reads mapping to the family

Anelloviridae predominated in sample E1 and Е4. Meanwhile in sample E2 the family

Orthomyxoviridae predominated. Additionally, in the samples E1 and E4 we found reads mapping to the Human bocavirus and

Pneumoviridae respectively (

Figure 1B), which is corresponding to the respiratory viruses detected in the PCR analysis. It is worth mentioning that in sample E4, contigs belonging to the family

Astroviridae were identified, specifically Astrovirus VA3. This finding is noteworthy as it is usually associated with gastrointestinal disorders [

39,

40], however there are also some studies reporting the presence of this virus in nasopharyngeal swabs from febrile children [

41,

42,

43].

3.3. Characterization of AVs Sequences

Sequences of AVs were detected in all tested samples, with sample E3 exhibiting a significantly higher number of assembled contigs of

Anelloviridae (p <0.05) compared to the others (

Figure 1A,

Table 2). While this abundance in E3 may be related to gender, as male typically have a richer anellome [

44], the possibility that AVs may have played a role in the development of inflammation cannot be excluded, as the patient exhibited respiratory symptoms.

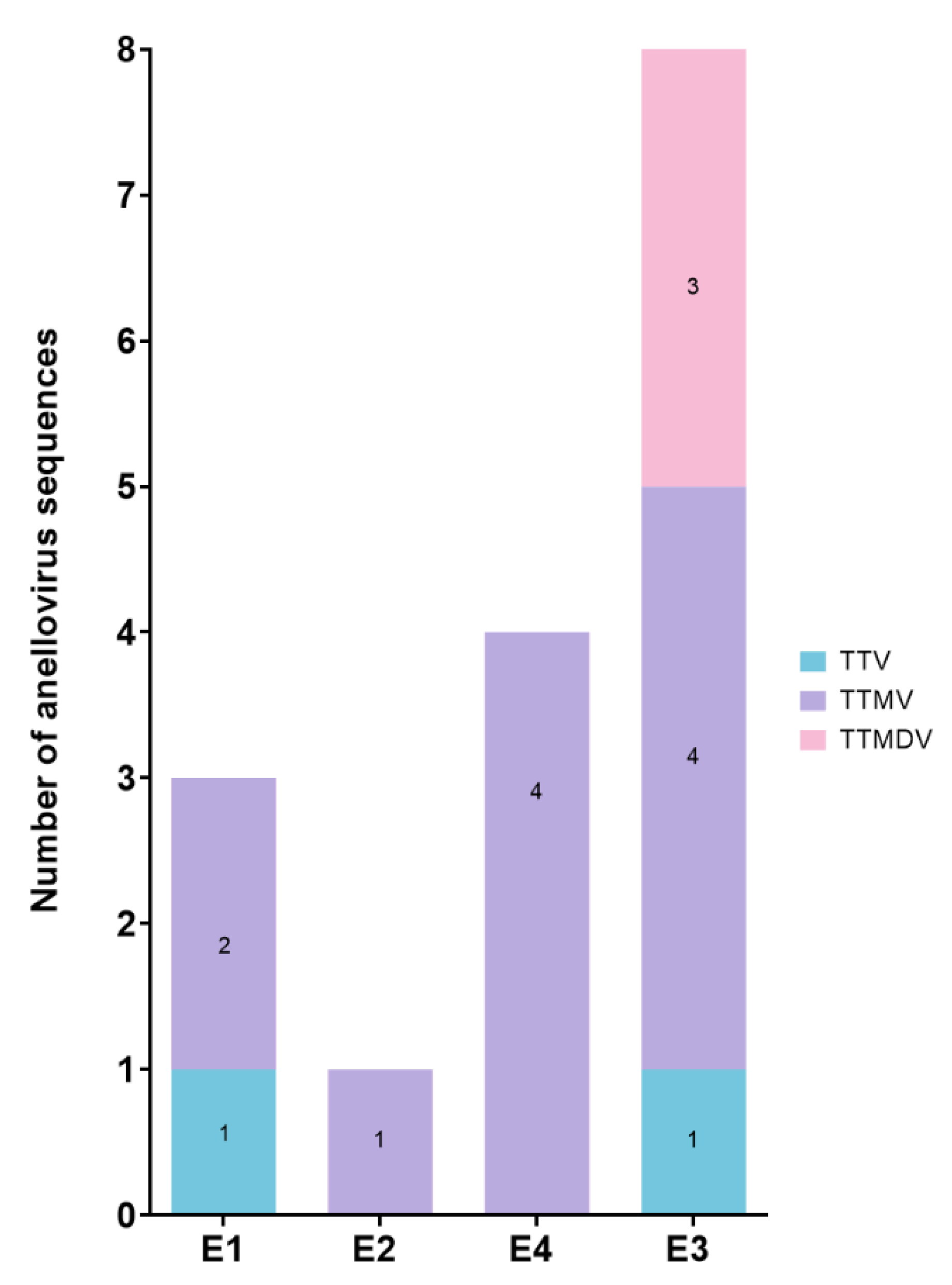

The overwhelming majority of AVs sequences identified across all patient samples belonged to the

Betatorquevirus genus (TTMV) (11 out of 16, 68.8%). Meanwhile, three sequences (18.8%) were attributed to the

Gammatorquevirus genus (TTMDV) and two sequences (12.5%) to the

Alphatorquevirus genus (TTV). The higher content of TTMVs and TTMDVs in children is in line with studies reporting an increased prevalence of these AVs in younger age groups [

10]. In our study, all individuals had TTMVs. However, E2 and E4 exhibited monoinfections (solely TTMV), E1 showed double coinfections (TTM + TTMV), and E3 presented with triple coinfections (TTM + TTMV + TTMDV) (

Figure 2).

3.4. Variability of AVs

To establish a genetic relationship between AVs strains, a phylogenetic analysis based on the amino acid sequence of ORF1 was conducted for 7 assembled full-length or almost full-length genomes (the smallest being 2,520 nt ORF1, 94% of the complete genome) (

Figure 3). The remaining 9 sequences had lengths less than 75% of ORF1, hence they were not included in the phylogenetic analysis.

All our sequences collected from pediatric patients show similarity to genomes obtained in a large viromic study of blood from febrile Tanzanian children [

45] (

Figure 3, evolutionary distances). These genomes display significant differences from previously well-described species in NCBI and do not cluster with them. This feature is particularly evident in the genus

Gammatorquevirus (

Figure 3), where the branch with reference strains is separate from the group of our sequences and those from the virome study of febrile children. This may indicate a significant gap in the detection and well description of TTMDV sequences, which could potentially fill the gap between these two branches.

Studied TTMV genomes differentiated into distant clades from each other and demonstrated a high degree of divergence. The exceptions are NODEA508_E2 and NODE99_E3, which exhibit a high degree of identity (99% amino acid similarity of ORF1,

Supplementary Table S1) despite being collected from different children. Due to the highly divergent TTMV sequences, it can be hypothesized that patient E3 was infected with multiple strains of

Betatorquevirus that evaded host immune system eradication. Two sequences of TTMDVs NODEA98_E3 and NODEA297_E3 are very similar (100% amino acid identity of ORF1,

Supplementary Table S1) and cluster together on the phylogenetic tree.

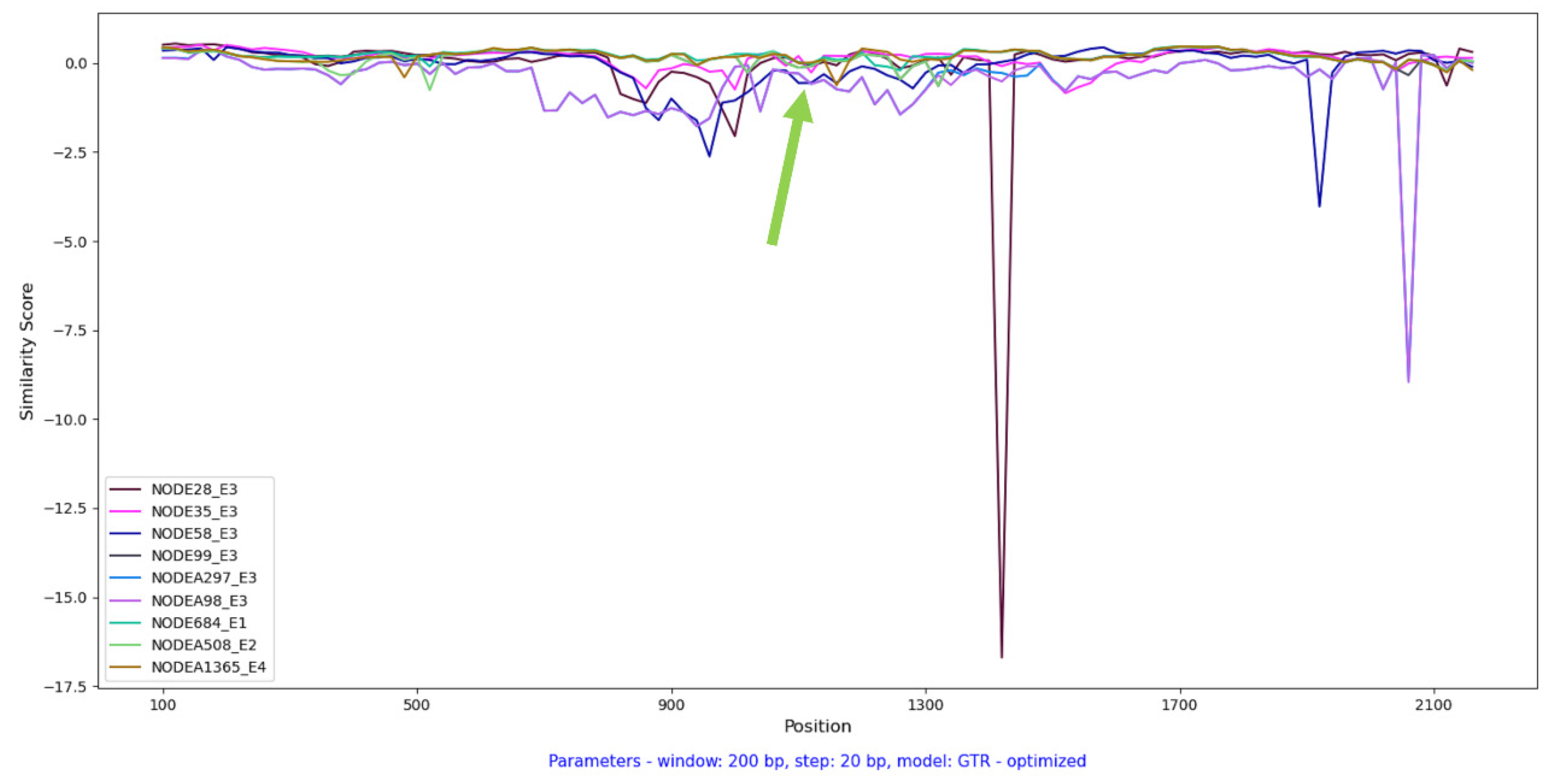

Additionally, a plot was constructed showing the similarity of ORF1 for TTMV sequences covering over 80% of the complete genome (

Figure 4). The alignment was performed against the prototype species for the TTMV genus - Torque teno mini virus 1-CBD279. The greatest distance from the prototype strain was demonstrated by NODE_28, NODE_58, NODE_98 from sample E3.

4. Discussion

Thus, the current metagenomic study provided viral profiles for children with respiratory symptoms. The analysis of the obtained data confirmed the results of PCR diagnostics for major respiratory pathogens. Additionally, it provided information on AVs in the examined pediatric patients. The research findings indicate that different AVs are presented in the virome of children with acute respiratory symptoms. The presence of viruses from

Anelloviridae family in all samples is accordance with data on the prevalence of AV-infections in children with respiratory diseases [

6,

48].

Interestingly, in the symptomatically diseased patient without respiratory viruses, there was the highest representation of AVs in terms of both read numbers and genetic diversity. It is possible that this representation of AVs can activate immune and inflammatory responses, influencing the occurrence and maintenance of respiratory symptoms. Although a similar phenomenon has so far been well described only for TTV infection, in which TTV interacts with PAMPs (Pathogen-associated molecular patterns) receptors, modulating inflammation [

1,

8,

19,

48,

49,

50]

The low representation of AVs in patients with respiratory viruses (E1, E2, E4 as opposed to E3) prompts speculation about the conditions under which AVs have an opportunity for replication. It is likely that the immune system, activated to combat pathogens, suppresses the replication of AVs. After the elimination of the main pathogen, AVs increase to their initial levels, and the anellome stabilizes. Similar observations in fluctuations of AV levels have been made in patients with COVID-19, where the anellovirus load significantly decreased in the first weeks of SARS-CoV-2 infection [

51].

TTVs were detected only in samples E1 and E3, possibly due to a tendency for anellome to shift toward the presence of

Alphatorquevirus with age [

10,

52]. TTMDVs were identified only in the E3 sample, which exhibited the highest diversity of annelloviruses.

All patients exhibited respiratory symptoms and TTMVs were present in the anellome. However, contrary data can be found that the human AV TTMV is not associated with fever and severe infection [

6]. Unfortunately, the widespread presence of AVs complicates the search for a definitive answer to whether this group of viruses truly worsens the clinical course of the disease.

5. Limitations

A technical negative control sample (i.e., a sample with transport medium and probe) that underwent metagenomic analysis was missing in our study. However, we compared the assembled contigs of respiratory viruses and found no identical contigs across different samples, indicating the absence of cross-contamination.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Distance matrix of multiple alignments of amino acid sequences from ORF1, calculated in relative numbers using the “Simple Similarity” option using UGENE.

Funding

This research was supported by project RSF 19-74-10055-P (sampling, laboratory diagnostics, and analysis) and by the State-funded budget project 122012400086-2 (sample preparation for metagenomics).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the legal representatives of all children involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets is deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (accession number are available upon request). Seven sequences of AVs from phylogenetic analysis are available in GenBank (accession numbers are available upon request).

Acknowledgments

We thank the clinicians of Novosibirsk Children’s Municipal Clinical Hospitals №6 for their assistance with sample collection. The study was partly supported by the Centers for Collective Use of Scientific Equipment “Proteomic analysis”, and funding was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (agreement No. 075-15-2021-691), “Modern optical Systems” of Research Center of Fundamental and Translational Medicine (Novosibirsk, Russia)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Freer, G.; Maggi, F.; Pifferi, M.; Di Cicco, M.E.; Peroni, D.G.; Pistello, M. The Virome and Its Major Component, Anellovirus, a Convoluted System Molding Human Immune Defenses and Possibly Affecting the Development of Asthma and Respiratory Diseases in Childhood. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.B.; Glanville, A.R. Introduction to Techniques and Methodologies for Characterizing the Human Respiratory Virome. In The Human Virome; Moya, A., Pérez Brocal, V., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4939-8681-1. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijn, A.L.; Van Boheemen, S.; Sidorov, I.; Carbo, E.C.; Pappas, N.; Mei, H.; Feltkamp, M.; Aanerud, M.; Bakke, P.; Claas, E.C.J.; et al. The Respiratory Virome and Exacerbations in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, W.M.; Fumagalli, M.J.; De Araujo, J.; Sabino-Santos, G.; Maia, F.G.M.; Romeiro, M.F.; Modha, S.; Nardi, M.S.; Queiroz, L.H.; Durigon, E.L.; et al. Discovery of Novel Anelloviruses in Small Mammals Expands the Host Range and Diversity of the Anelloviridae. Virology 2018, 514, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spandole, S.; Cimponeriu, D.; Berca, L.M.; Mihăescu, G. Human Anelloviruses: An Update of Molecular, Epidemiological and Clinical Aspects. Arch Virol 2015, 160, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElvania TeKippe, E.; Wylie, K.M.; Deych, E.; Sodergren, E.; Weinstock, G.; Storch, G.A. Increased Prevalence of Anellovirus in Pediatric Patients with Fever. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.J.; Keeler, E.L.; Bushman, F.D.; Collman, R.G. The Enigmatic Roles of Anelloviridae and Redondoviridae in Humans. Curr Opin Virol 2022, 55, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggi, F.; Pifferi, M.; Tempestini, E.; Fornai, C.; Lanini, L.; Andreoli, E.; Vatteroni, M.; Presciuttini, S.; Pietrobelli, A.; Boner, A.; et al. TT Virus Loads and Lymphocyte Subpopulations in Children with Acute Respiratory Diseases. J Virol 2003, 77, 9081–9083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, J.; van der Hoek, L. Human Anelloviruses: Diverse, Omnipresent and Commensal Members of the Virome. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2020, 44, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, J.; Cicilionytė, A.; Timmerman, A.L.; Deijs, M.; Jebbink, M.F.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Van Keulen, B.J.; Bakker, M.; Van Der Hoek, L. Early-Life Colonization by Anelloviruses in Infants. Viruses 2022, 14, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsani, A.; Opriessnig, T.; Celer, V.; Maggi, F.; Okamoto, H.; Blomström, A.-L.; Cadar, D.; Harrach, B.; Biagini, P.; Kraberger, S. Taxonomic Update for Mammalian Anelloviruses (Family Anelloviridae). Arch Virol 2021, 166, 2943–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arze, C.A.; Springer, S.; Dudas, G.; Patel, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Swaminathan, H.; Brugnara, C.; Delagrave, S.; Ong, T.; Kahvejian, A.; et al. Global Genome Analysis Reveals a Vast and Dynamic Anellovirus Landscape within the Human Virome. Cell Host & Microbe 2021, 29, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.A.; Young, J.C.; Clarke, E.L.; Diamond, J.M.; Imai, I.; Haas, A.R.; Cantu, E.; Lederer, D.J.; Meyer, K.; Milewski, R.K.; et al. Bidirectional Transfer of Anelloviridae Lineages between Graft and Host during Lung Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2019, 19, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jazaeri Farsani, S.M.; Jebbink, M.F.; Deijs, M.; Canuti, M.; van Dort, K.A.; Bakker, M.; Grady, B.P.X.; Prins, M.; van Hemert, F.J.; Kootstra, N.A.; et al. Identification of a New Genotype of Torque Teno Mini Virus. Virol J 2013, 10, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, R.; Saresella, M.; Hernis, A.; Agostini, S.; Piancone, F.; Caputo, D.; Maggi, F.; Clerici, M. Torque Teno Virus (TTV) in Multiple Sclerosis Patients with Different Patterns of Disease. Journal of Medical Virology 2013, 85, 2176–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibayama, T.; Masuda, G.; Ajisawa, A.; Takahashi, M.; Nishizawa, T.; Tsuda, F.; Okamoto, H. Inverse Relationship between the Titre of TT Virus DNA and the CD4 Cell Count in Patients Infected with HIV. AIDS 2001, 15, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wan, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Jin, X.; Hao, P.; et al. HIV-1 Infection Alters the Viral Composition of Plasma in Men Who Have Sex with Men. mSphere 2021, 6, e00081–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmerman, A.L.; Schönert, A.L.M.; van der Hoek, L. Anelloviruses versus Human Immunity: How Do We Control These Viruses? FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2024, 48, fuae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodi, G.; Attanasi, M.; Di Filippo, P.; Di Pillo, S.; Chiarelli, F. Virome in the Lungs: The Role of Anelloviruses in Childhood Respiratory Diseases. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moen, E.M.; Sagedal, S.; Bjøro, K.; Degré, M.; Opstad, P.K.; Grinde, B. Effect of Immune Modulation on TT Virus (TTV) and TTV-like-Mini-Virus (TLMV) Viremia. J Med Virol 2003, 70, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifferi, M.; Maggi, F.; Andreoli, E.; Lanini, L.; Marco, E.D.; Fornai, C.; Vatteroni, M.L.; Pistello, M.; Ragazzo, V.; Macchia, P.; et al. Associations between Nasal Torquetenovirus Load and Spirometric Indices in Children with Asthma. J Infect Dis 2005, 192, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, A.; Destras, G.; Sabatier, M.; Pichon, M.; Regue, H.; Oriol, G.; Gillet, Y.; Lina, B.; Brengel-Pesce, K.; Josset, L.; et al. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals High Abundance of Torque Teno Mini Virus in the Respiratory Tract of Children with Acute Respiratory Illness. Viruses 2022, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rosal, T.; García-García, M.L.; Casas, I.; Iglesias-Caballero, M.; Pozo, F.; Alcolea, S.; Bravo, B.; Rodrigo-Muñoz, J.M.; Del Pozo, V.; Calvo, C. Torque Teno Virus in Nasopharyngeal Aspirate of Children With Viral Respiratory Infections. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2023, 42, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição-Neto, N.; Yinda, K.C.; Van Ranst, M.; Matthijnssens, J. NetoVIR: Modular Approach to Customize Sample Preparation Procedures for Viral Metagenomics. In The Human Virome; Moya, A., Pérez Brocal, V., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4939-8681-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chrzastek, K.; Lee, D.; Smith, D.; Sharma, P.; Suarez, D.L.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.; Kapczynski, D.R. Use of Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer-Amplification (SISPA) for Rapid Detection, Identification, and Characterization of Avian RNA Viruses. Virology 2017, 509, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S. Ultrafast One-pass FASTQ Data Preprocessing, Quality Control, and Deduplication Using Fastp. iMeta 2023, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, B. BBMap: A Fast, Accurate, Splice-Aware Aligner. 2014.

- Xu, H.; Luo, X.; Qian, J.; Pang, X.; Song, J.; Qian, G.; Chen, J.; Chen, S. FastUniq: A Fast De Novo Duplicates Removal Tool for Paired Short Reads. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: A New Versatile Metagenomic Assembler. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchfink, B.; Xie, C.; Huson, D.H. Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment Using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillippy, A.M. Interactive Metagenomic Visualization in a Web Browser. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows–Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. ; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkbeiner, S.R.; Holtz, L.R.; Jiang, Y.; Rajendran, P.; Franz, C.J.; Zhao, G.; Kang, G.; Wang, D. Human Stool Contains a Previously Unrecognized Diversity of Novel Astroviruses. Virol J 2009, 6, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, A.; Li, L.; Victoria, J.; Oderinde, B.; Mason, C.; Pandey, P.; Zaidi, S.Z.; Delwart, E. Multiple Novel Astrovirus Species in Human Stool. Journal of General Virology 2009, 90, 2965–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wylie, K.M.; Mihindukulasuriya, K.A.; Sodergren, E.; Weinstock, G.M.; Storch, G.A. Sequence Analysis of the Human Virome in Febrile and Afebrile Children. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e27735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordey, S.; Brito, F.; Vu, D.-L.; Turin, L.; Kilowoko, M.; Kyungu, E.; Genton, B.; Zdobnov, E.M.; D’Acremont, V.; Kaiser, L. Astrovirus VA1 Identified by Next-Generation Sequencing in a Nasopharyngeal Specimen of a Febrile Tanzanian Child with Acute Respiratory Disease of Unknown Etiology. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2016, 5, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordey, S.; Zanella, M.; Wagner, N.; Turin, L.; Kaiser, L. Novel Human Astroviruses in Pediatric Respiratory Samples: A One-year Survey in a Swiss Tertiary Care Hospital. Journal of Medical Virology 2018, 90, 1775–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebriá-Mendoza, M.; Beamud, B.; Andreu-Moreno, I.; Arbona, C.; Larrea, L.; Díaz, W.; Sanjuán, R.; Cuevas, J.M. Human Anelloviruses: Influence of Demographic Factors, Recombination, and Worldwide Diversity. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e04928–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordey, S.; Laubscher, F.; Hartley, M.-A.; Junier, T.; Keitel, K.; Docquier, M.; Guex, N.; Iseli, C.; Vieille, G.; Le Mercier, P.; et al. Blood Virosphere in Febrile Tanzanian Children. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2021, 10, 982–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, S.; Lord, É.; Makarenkov, V. SimPlot++: A Python Application for Representing Sequence Similarity and Detecting Recombination. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 3118–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggi, F.; Bendinelli, M. Immunobiology of the Torque Teno Viruses and Other Anelloviruses. In TT Viruses; De Villiers, E.-M., Hausen, H.Z., Eds.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009; ISBN 978-3-540-70971-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Ye, L.; Fang, X.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, X.; Kong, L.; Wang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, L.; et al. Torque Teno Virus (SANBAN Isolate) ORF2 Protein Suppresses NF-κB Pathways via Interaction with IκB Kinases. J Virol 2007, 81, 11917–11924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchi, J.; Ricci, V.; Albani, M.; Lanini, L.; Andreoli, E.; Macera, L.; Pistello, M.; Ceccherini-Nelli, L.; Bendinelli, M.; Maggi, F. Torquetenovirus DNA Drives Proinflammatory Cytokines Production and Secretion by Immune Cells via Toll-like Receptor 9. Virology 2009, 394, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmerman, A.L.; Commandeur, L.; Deijs, M.; Burggraaff, M.G.J.M.; Lavell, A.H.A.; Van Der Straten, K.; Tejjani, K.; Van Rijswijk, J.; Van Gils, M.J.; Sikkens, J.J.; et al. The Impact of First-Time SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Human Anelloviruses. Viruses 2024, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubscher, F.; Hartley, M.-A.; Kaiser, L.; Cordey, S. Genomic Diversity of Torque Teno Virus in Blood Samples from Febrile Paediatric Outpatients in Tanzania: A Descriptive Cohort Study. Viruses 2022, 14, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).