Submitted:

16 April 2024

Posted:

18 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Tungsten-Doped Vanadium Dioxide Thin Films with Different Contents

2.2. Characterization Measurement of Tungsten-Doped Vanadium Dioxide Thin Films

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optical Properties of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

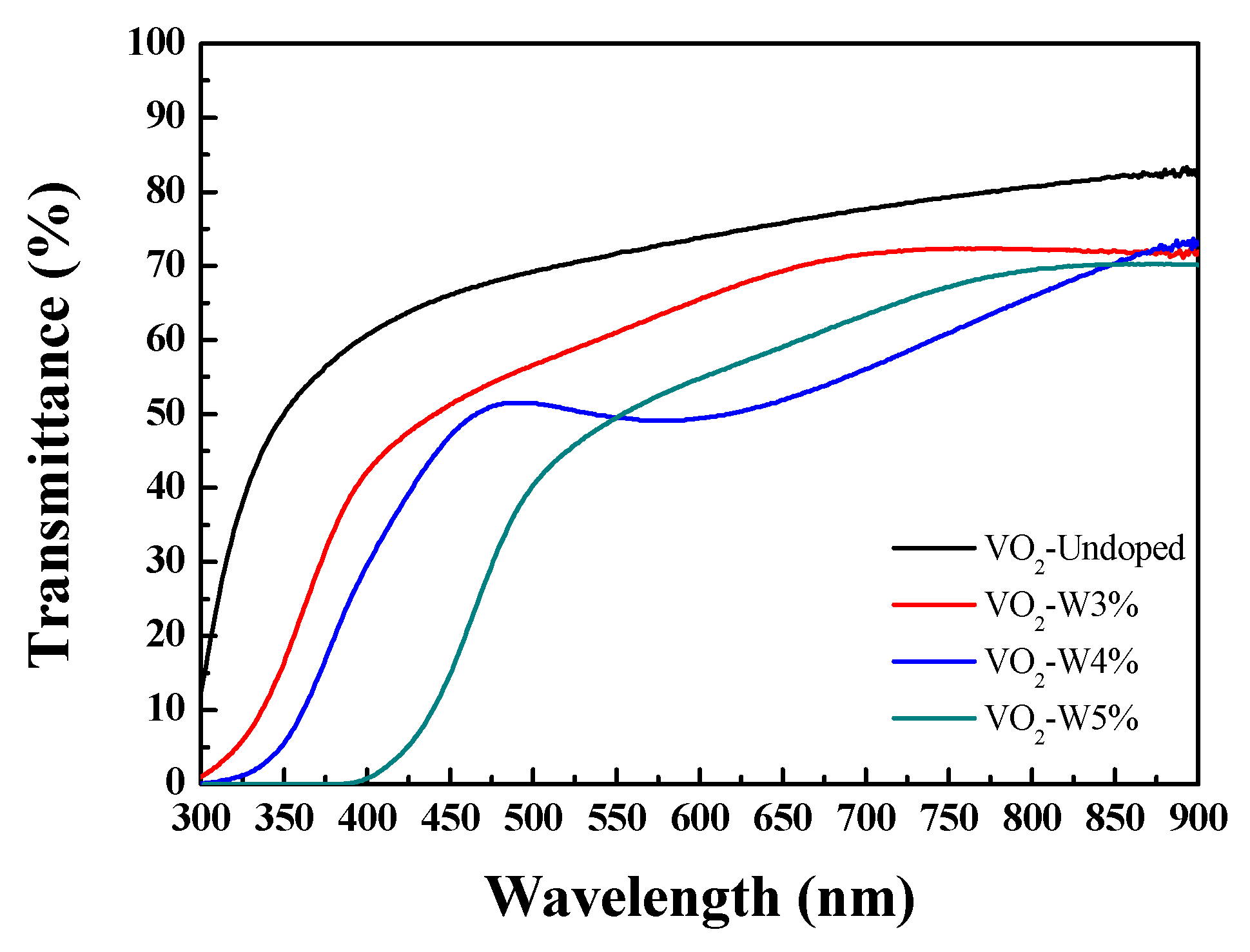

3.1.1. Transmission Spectral Characteristics of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

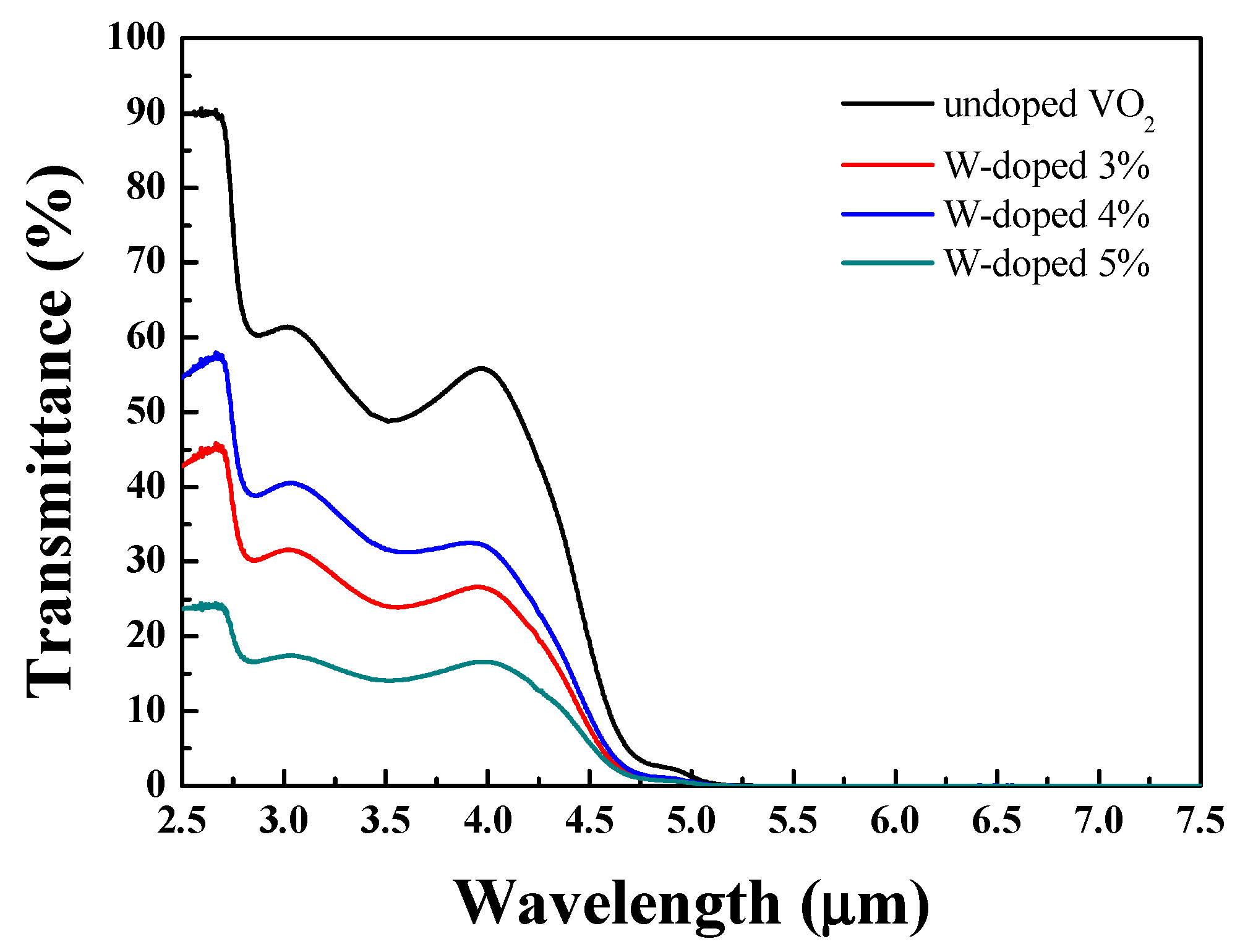

3.1.2. Infrared Transmittance Spectra of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

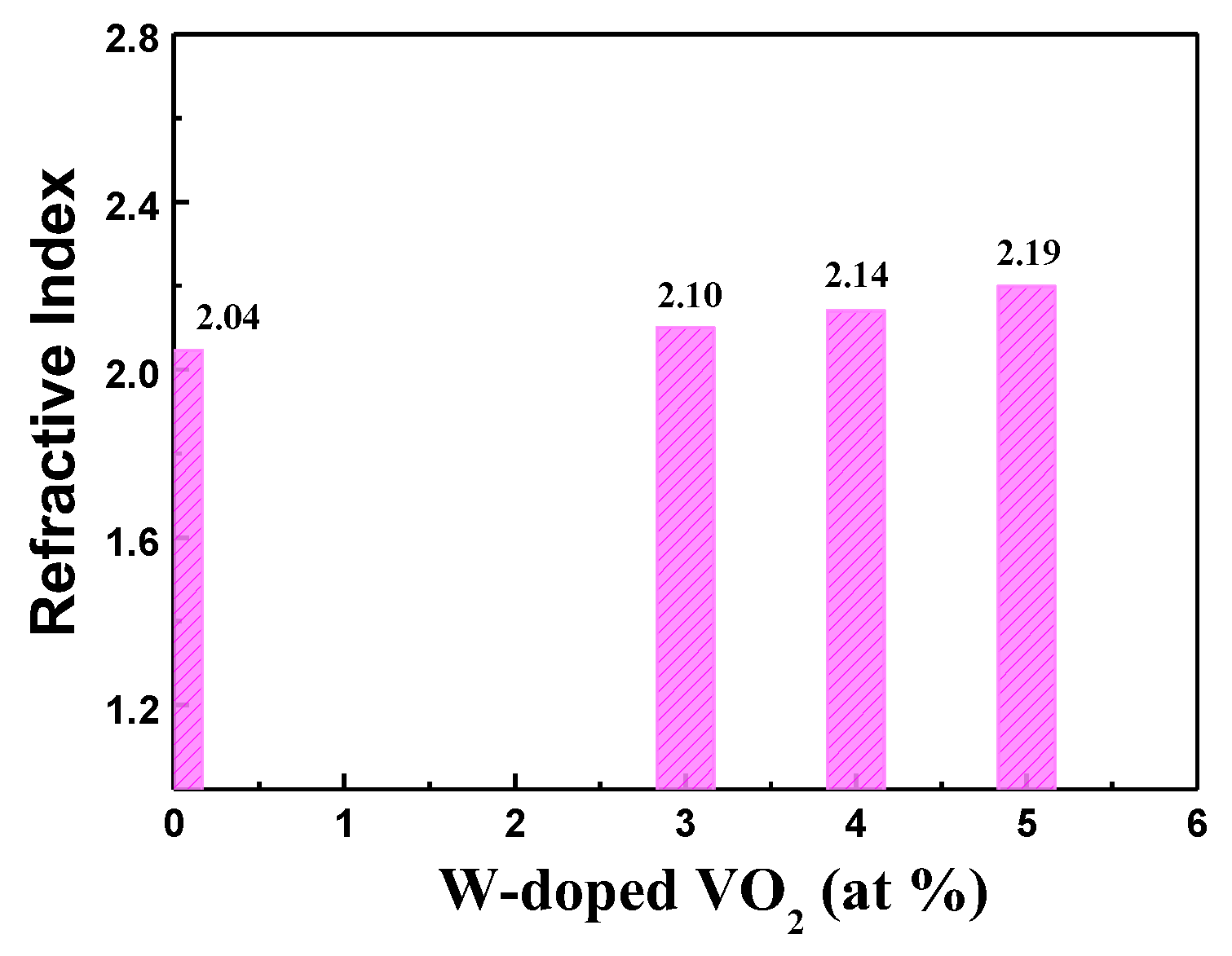

3.1.3. Refractive Index of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

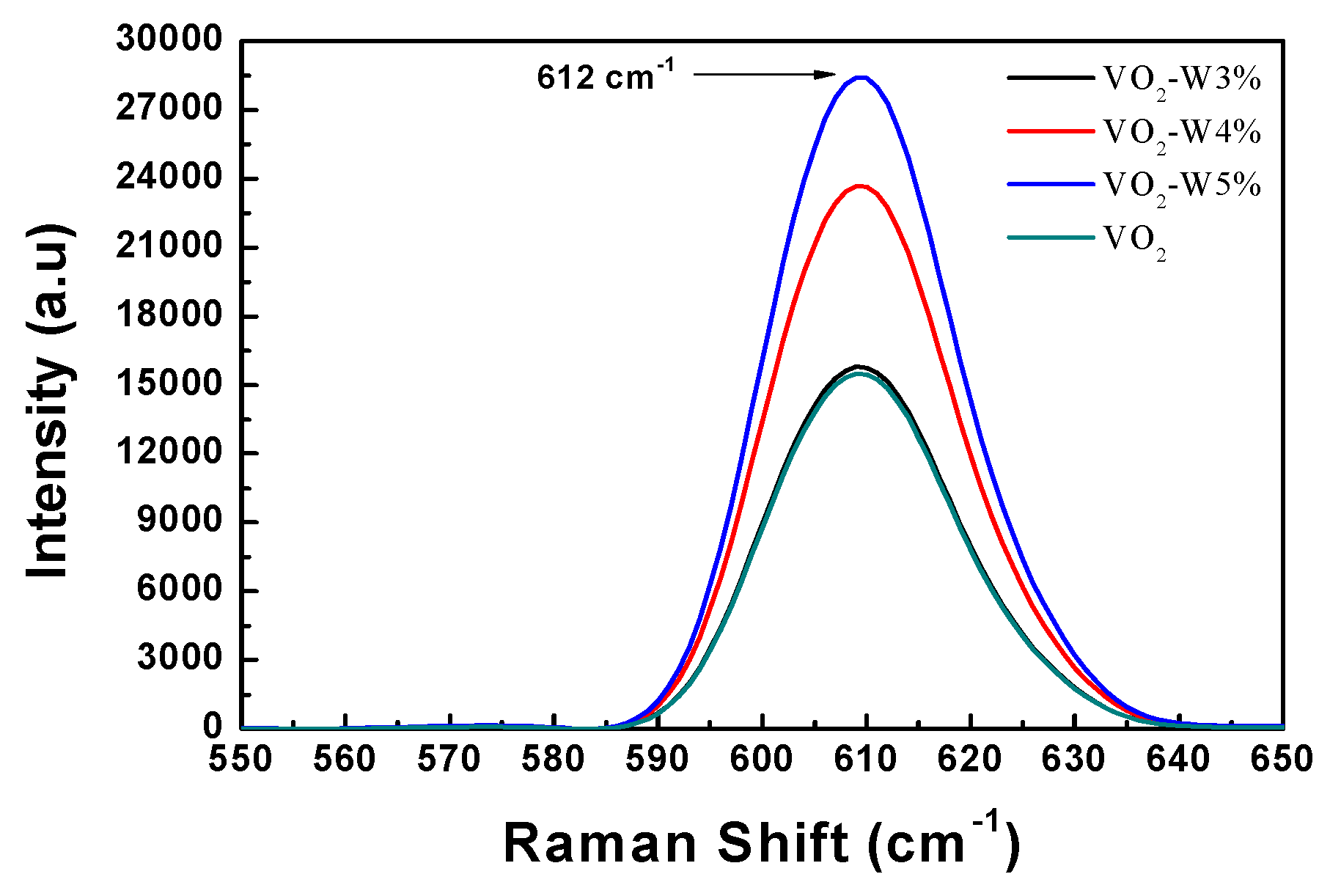

3.1.4. Raman Spectra of W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

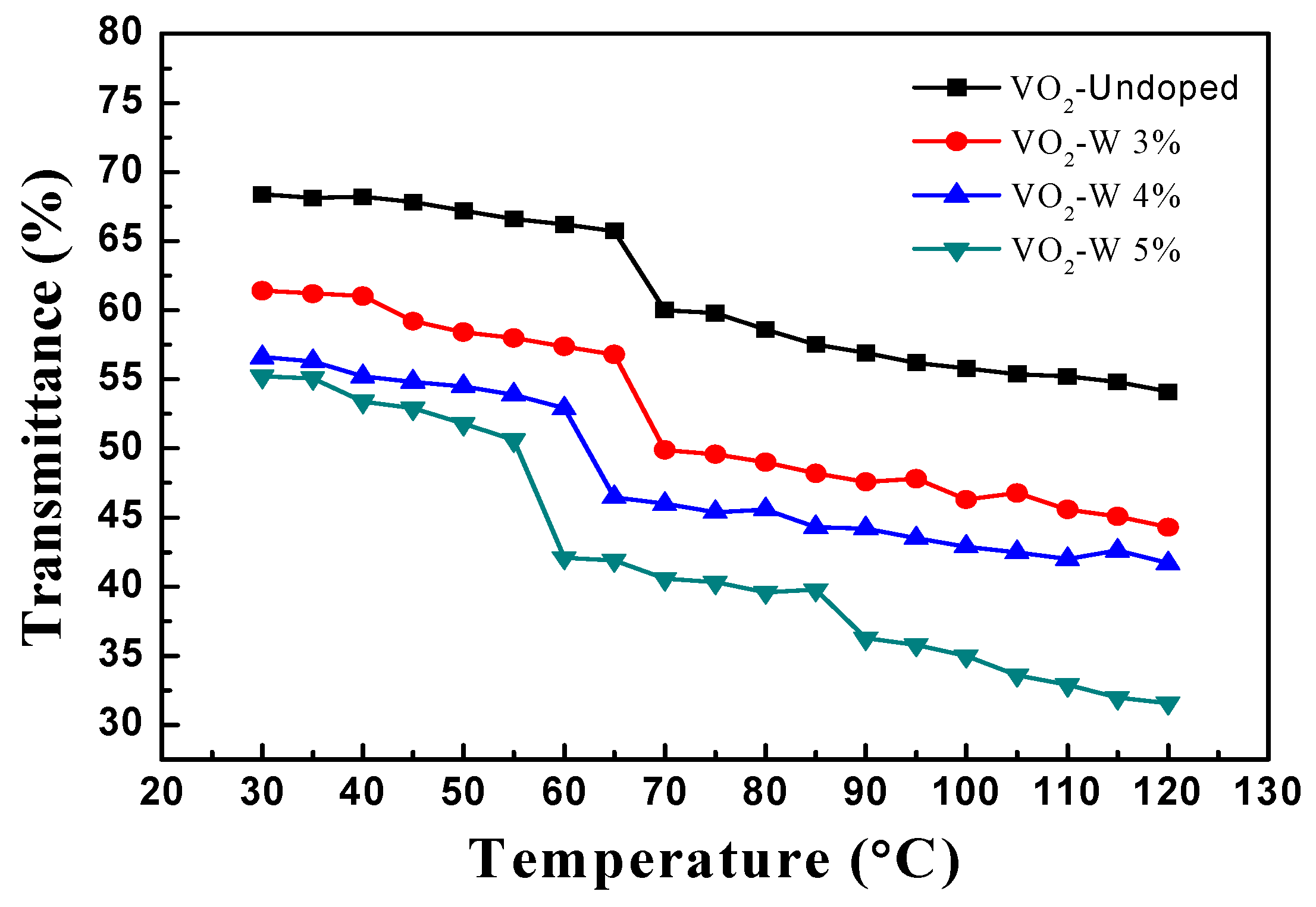

3.1.5. Temperature-Dependent Transmission Spectra of VO2 Thin Films

3.2. Thermo-Mechanical Properties of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

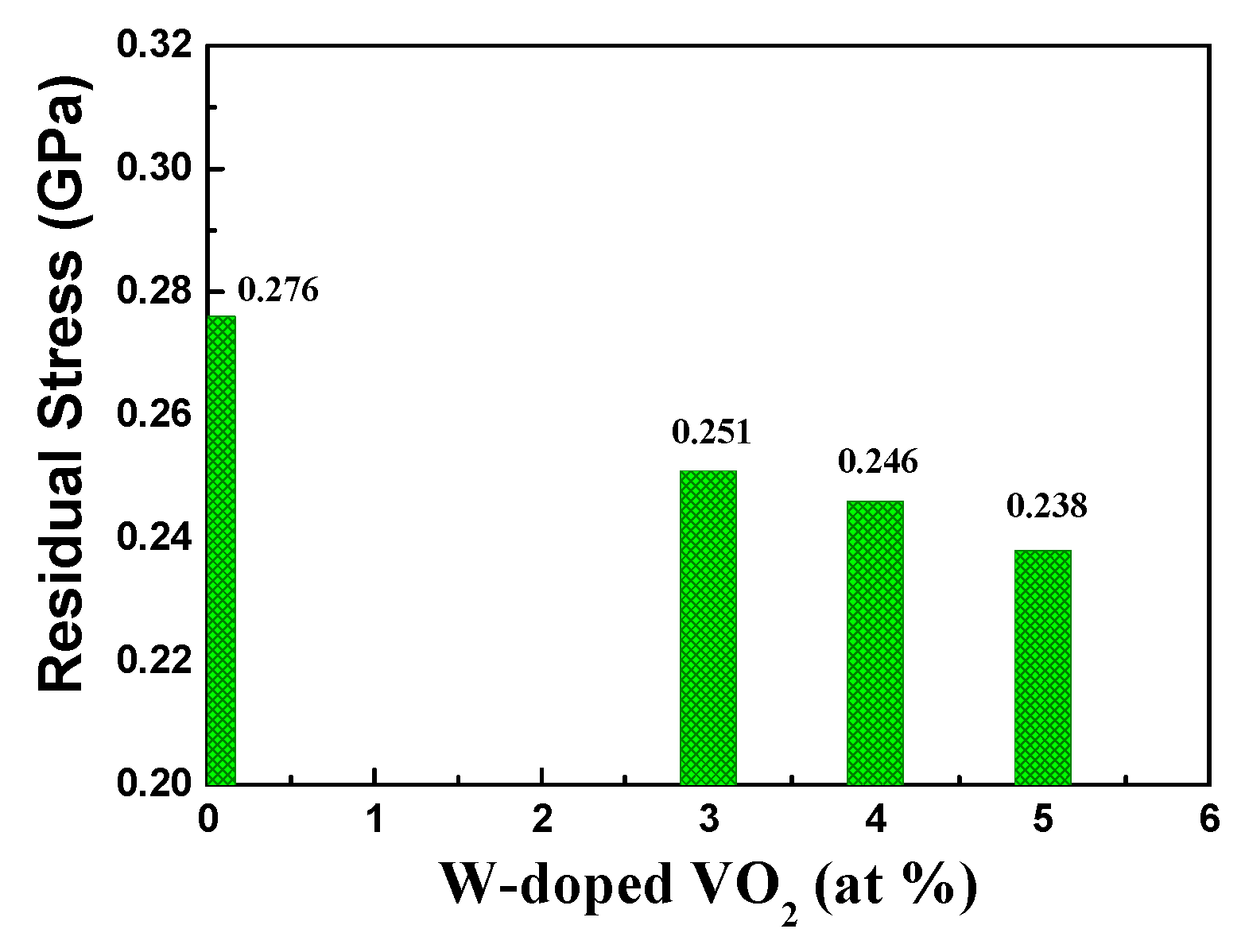

3.2.1. Residual Stress of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

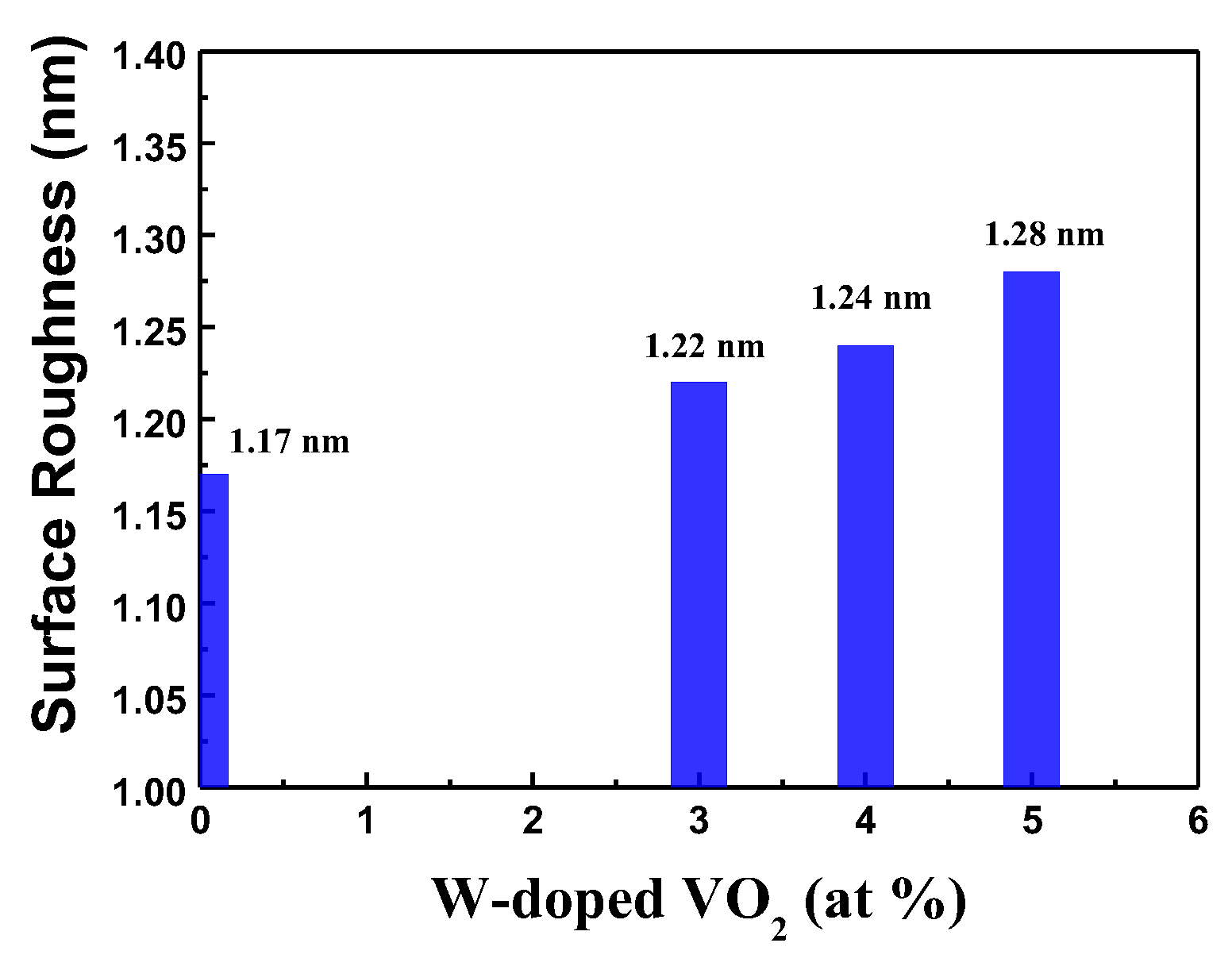

3.2.2. Surface Roughness Measurement of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

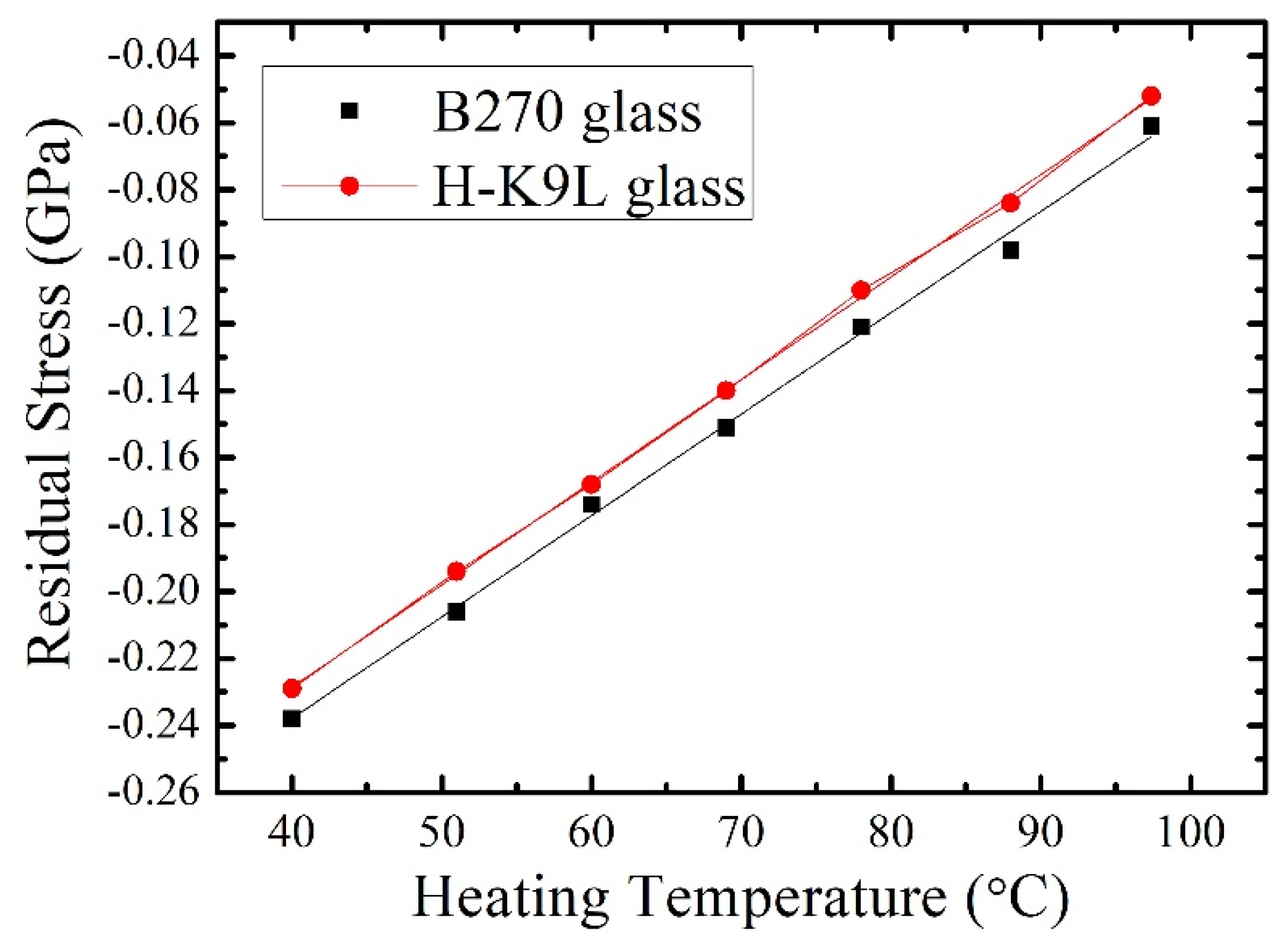

3.2.3. Temperature-Dependent Residual Stress of W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

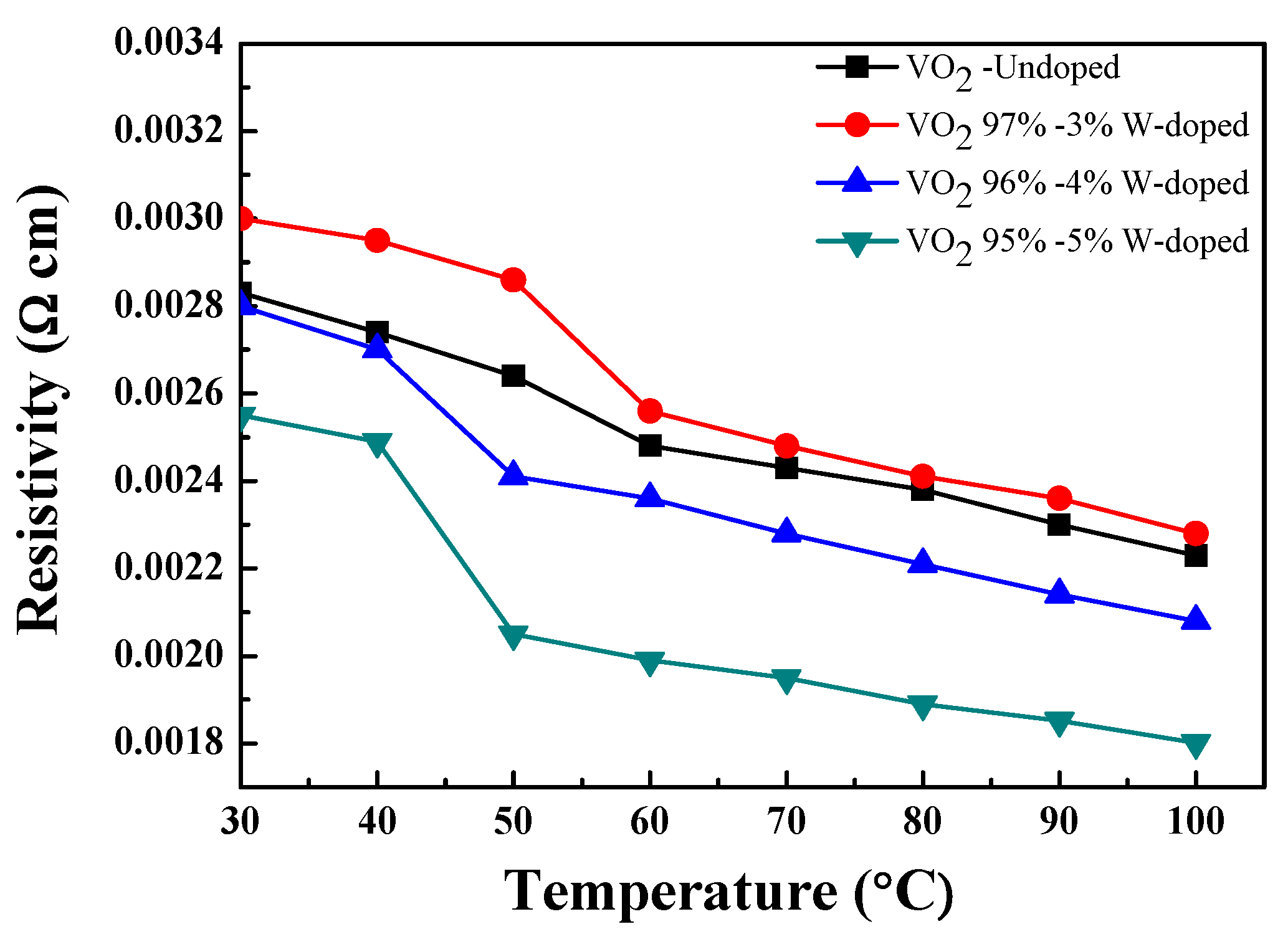

3.2.4. Temperature-Dependent Electrical Resistivity of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

3.3. Microstructural Properties of VO2 Thin Films

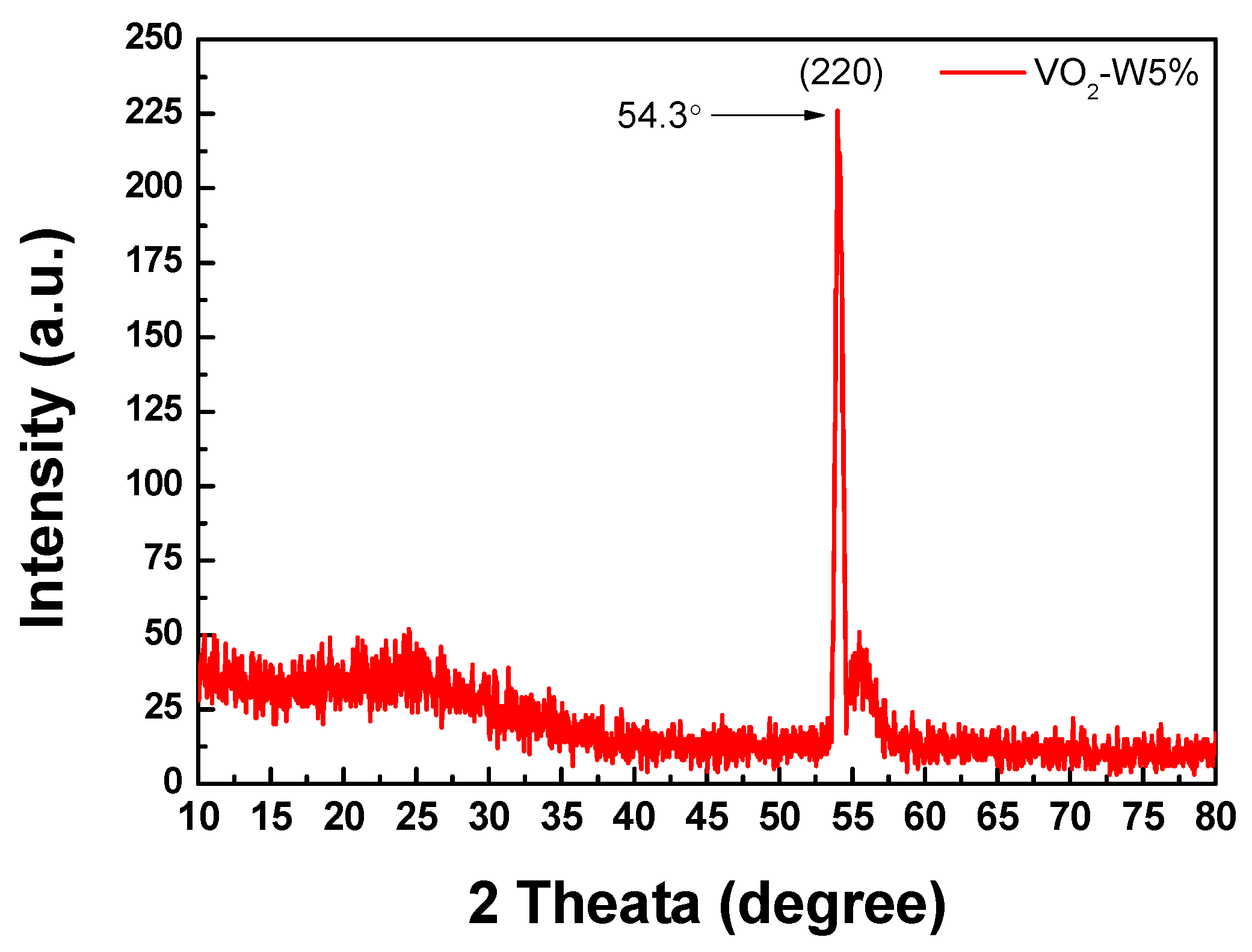

3.3.1. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) of W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

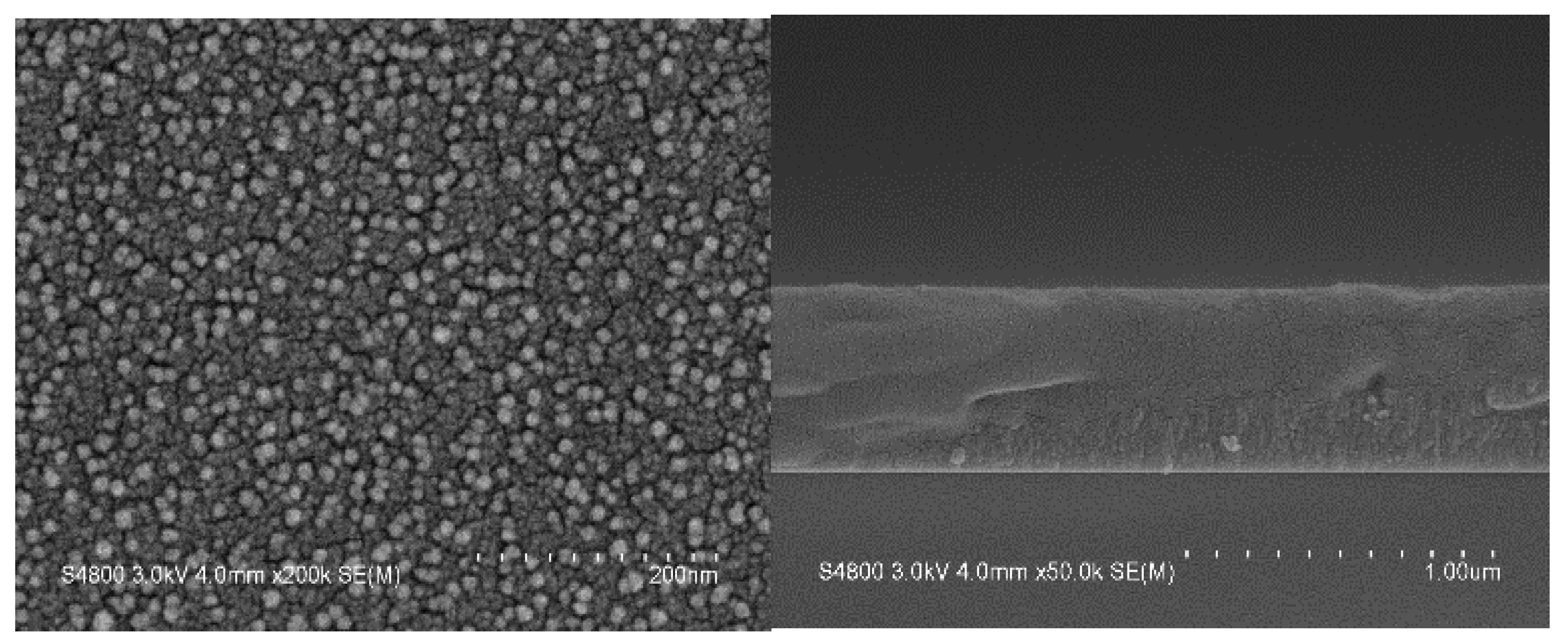

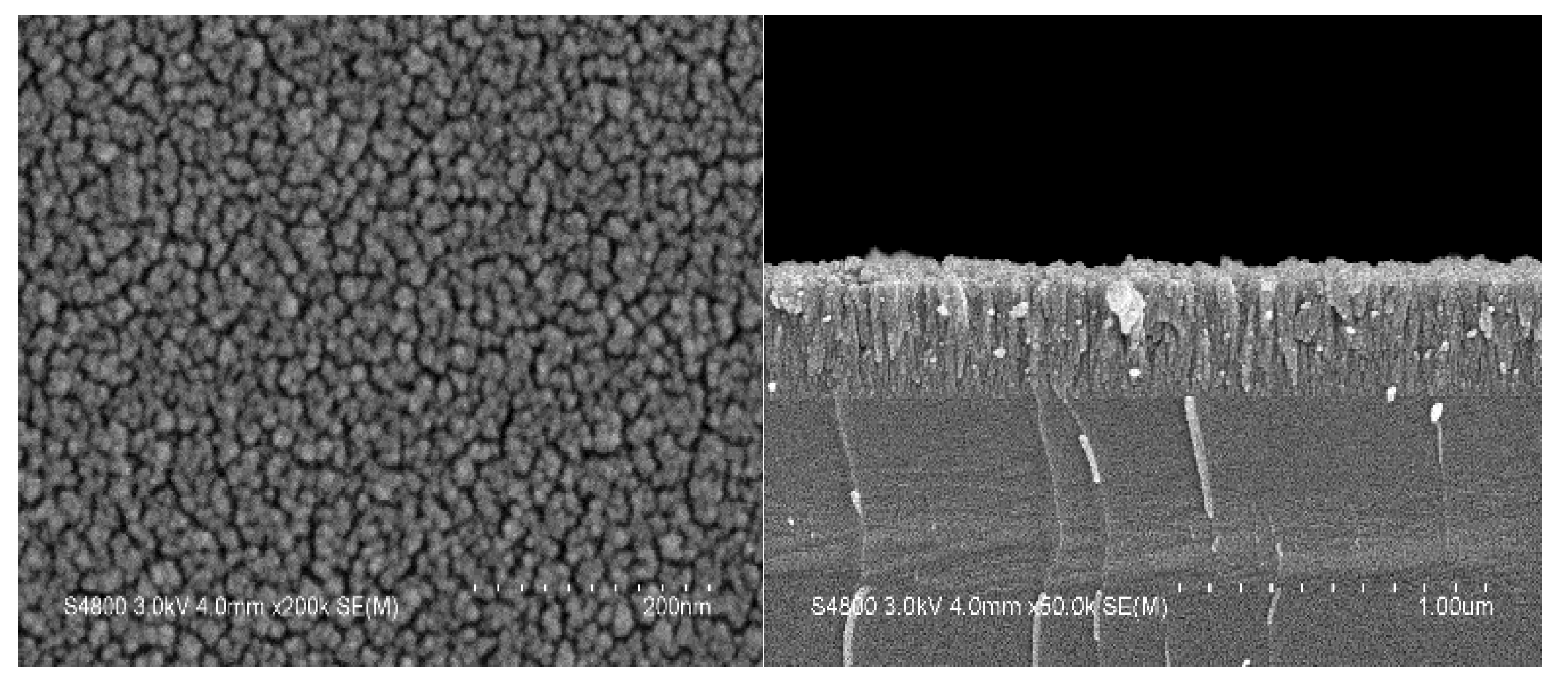

3.3.2. Surface Morphology of Undoped VO2 and W-Doped VO2 Thin Films

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tain, J.; Peng, H.; Du, X.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Du, Z. Hybrid thermochromic microgels based on UCNPs/PNIPAm hydrogel for smart window with enhanced solar modulation. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 858, 157725. [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C.; Cao, X.; Bao, S.H.; Ji, S.D.; Luo, H.J.; Jin, P. Review on thermochromic vanadium dioxide based smart coatings: from lab to commercial application. Advances Manufacturing 2018, 6, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.D.; Pan, T.S.; Bi, Z.; Liang, W.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.Z.; Wen, Q.Y.; Zhang, H.W.; Chen, C.L.; Jia, Q.X.; Lin, Y. Epitaxial growth and metal-insulator transition of vanadium oxide thin films with controllable phases. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 071902. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Huang, K.; Tang, Z.; Xu, X.; Tan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Wang, C.; Cao, J. The effect of Argon pressure dependent V thin film on the phase transition process of VO2 thin film. Applied Surface Science 2018, 427, Part B 304-311. [CrossRef]

- Bhupathi, S.; Wang, S.; Ke, Y.; Long, Y. Recent progress in vanadium dioxide: The multi-stimuli responsive material and its applications. Materials Science and Engineering 2023, 155, 100747. [CrossRef]

- Dou, S., Zhang, W., Wang, Y., Tian, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, L., Wang, L., Zhao, J., Li, Y. A facile method for the preparation of W-doped VO2 films with lowered phase transition temperature, narrowed hysteresis loops and excellent cycle stability. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2018, 215, 91-98. [CrossRef]

- Outón, J.; Casas-Acuña, A.; Domínguez, M.; Blanco, E.; Delgado, J.J.; Ramírez-del-Solar, M. Novel laser texturing of W-doped VO2 thin film for the improvement of luminous transmittance in smart windows application. Applied Surface Science 2023, 608, 155180. [CrossRef]

- Takami, H.; Kanki, T.; Ueda, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Tanaka, H. Filling-controlled Mott transition in W-doped VO2. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 205111. [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Liu, D.; Cheng, H. Infrared optical modulation characteristics of W-doped VO2(M) nanoparticles in the MWIR and LWIR regions. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2020, 119, 105141. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhou, L. Preparation, characterization and properties of thermochromic tungsten-doped vanadium dioxide by thermal reduction and annealing. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2010, 504, 503-507. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Kim, M.G. RTA and stoichiometry effect on the thermochromism of VO2 thin films. Thin Solid Films 1996, 286(1–2), 219–222. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Mansour, S. A critical overview of thin films coating technologies for energy applications. Cogent Engineering 2023, 10, 2179467. [CrossRef]

- Tien, C. L.; Zeng, H. D. Measuring residual stress of anisotropic thin film by fast Fourier transform. Optics Express 2010, 18(16), 16594-16600. [CrossRef]

- Tien, C. L.; Yang, H.M.; Liu, M.C. The measurement of surface roughness of optical thin films based on fast Fourier transform. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517(17), 5110-5115. [CrossRef]

- Tien, C. L.; Yu, K.C.; Tsai, T.Y.; Lin, C.S.; Li, C.Y. Measurement of surface roughness of thin films by a hybrid interference microscope with different phase algorithms. Applied Optics 2014, 53 (29), H213-H219. [CrossRef]

- Begara, F. U.; Crunteanu, A.; Raskina, J. P. Raman and XPS characterization of vanadium oxide thin films with temperature. Applied Surface Science 2017, 403, 717-727. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Heredia, C. L.; Ramirez-Rincon, J.A.; Bhardwaj, D.; Rajasekar, P.; Tadeo, I. J.; Cervantes-Lopez, J. L.; Ordonez-Miranda, J.; Ares1, O.; Umarji, A. M.; Drevillon, J.; Joulain, K.; Ezzahri, Y.; Alvarado-Gil, J. J. Measurement of the hysteretic thermal properties of W-doped and undoped nanocrystalline powders of VO2. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 14687. [CrossRef]

- Mulchandani, K.; Soni, A.; Pathy, K.; Mavani, K.R. Structural Transformation and Tuning of Electronic Transitions by W-Doping in VO2 Thin Films. Superlattices Microstruct. 2021, 154, 106883. [CrossRef]

- Schilbe, P. Raman Scattering in VO2. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2002, 316–317, 600–602. [CrossRef]

- Jung, K. H.; Yun, S. J.; Slusar, T.; Kim, H.T.; Roh, T. M. Highly transparent ultrathin vanadium dioxide films with temperature-dependent infrared reflectance for smart windows. Applied Surface Science 2022, 589, 714-721. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. E.; Lu, H. H.; Brahma, S. Effects of annealing on thermochromic properties of W-doped vanadium dioxide thin films deposited by electron beam evaporation. Thin Solid Films 2017, 644, 52-56. [CrossRef]

- Batista, C.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Teixeira, V. Synthesis and characterization of VO2-based thermochromic thin films for energy-efficient windows. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kittiwatanakul, S.; Laverock, J.; Newby, D.; Smith, K.E.; Wolf, S.A.; Lu, J. Transport behavior and electronic structure of phase pure VO2 thin films grown on c-plane sapphire under different O2 partial pressure. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 053703. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.P.; Zhu, M.D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K.; Liang, G.X.; Zheng, Z.H.; Cai, X. M.; Fan, P. High performance VO2 thin films growth by DC magnetron sputtering at low temperature for smart energy efficient window application. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 659, 198–202. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh, J. P.; Chae, K.H.; Park, J.; Lee, H.H. Annealing effect on phase transition and thermochromic properties of VO2 thin films. Superlattices and Microstructures 2020, 137, 106335. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Bishop, S. R.; Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Bluhm, H.; Tuller, H. L.; Lee, H. N.; Yildiz, B. Electrochemically Triggered Metal-Insulator Transition between VO2 and V2O5. Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 28, 1803024. [CrossRef]

- Thurn, J.; Hughey, M. P. Evaluation of film biaxial modulus and coefficient of thermal expansion from thermoelastic film stress measurements. J Appl Phys. 2004, 95(12), 7892–7897. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X. Modeling of thermal stresses in elastic multilayer coating systems. Journal of Applied Physics 2015, 117(5), 055305. [CrossRef]

- J. Ye, J.; Zhou, L. Preparation, characterization and properties of thermochromic tungsten-doped vanadium dioxide by thermal reduction and annealing. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2010, 504, 503-507. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, C., Lv, C.; Chen, S. Tungsten-doped vanadium dioxide thin films on borosilicate glass for smart window application. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2013, 564, 158-161. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).