1. Introduction

Polyamide 6 (PA6), also known as nylon 6, is a kind of high-performance polymer with processability, excellent mechanical properties, chemical durability, and low cost. It can be used for spinning, blow molding, and industrial molding, which contributes to a wide range of applications in the fields of textiles, packaging, and engineering plastics.[

1,

2,

3] Currently, industrial nylon 6 is mostly prepared by hydrolysis ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactam(CPL) at high temperature, which has the advantages of relatively mild reaction conditions, easy scale-up production, and narrow molecular weight distribution. However, due to the influence of the hydrolysis ring-opening chemical equilibrium, the molecular weight of industrial nylon 6 products is not high.[

1,

4] Linear nylon 6 with not high molecular weight has insufficient melt strength, which limits its application in thermal forming, injection molding, foaming, and other fields dominated by stretching flow. [

5] In addition, linear nylon 6 with not high molecular weight is highly sensitive to crack propagation and exhibits brittle fracture behavior under low temperature and severe load conditions, with poor impact resistance. [

6] By introducing multifunctional monomers into the polymerization process, branched nylon 6 co-polymerized with the monomers and CPL can be prepared. Compared with linear nylon 6, branched nylon 6 has significantly different melt rheological properties and crystallization properties, which affect its processing properties in spinning, film stretching, injection molding, and other processes, thereby expanding the application of nylon 6.[

7,

8]

ε-lysine, with one carboxyl group and two amino groups, is an AB

2-type multifunctional compound. Currently, ε-lysine is mainly produced through fermentation of corn stalks in the industry, which has the advantages of wide raw material sources and environmental friendliness. [

9] By co-polymerizing ε-lysine or its derivatives with CPL, novel nylon 6 polymers with branched structure can be obtained. Scholl et al.[

10] prepared highly branched nylon 6 with a relative molecular weight of 23000 by starting from ε-lysine salt and adding a certain amount of copolymerizable monomer and adjusting the polymerization conditions. Steeman et al. [

11] prepared randomly branched nylon 6 by copolymerizing 2,4,6-triaminohexanoic acid with CPL, and the long-chain branching led to an increase in the zero-shear viscosity of nylon 6 and a more pronounced shear-thinning behavior, while the melt strength increased. Li et al. [

12] directly copolymerized ε-lysine with CPL to prepare randomly branched nylon 6 with a small amount of long-chain branching. With the close relative viscosity, the melting point of long-chain branched nylon 6 is basically the same as that of linear nylon 6, and it exhibits a more significant shear-thinning phenomenon. The introduction of long-chain branching increases the entanglement between molecular chains, making the molecular chains more easily oriented along the processing direction.

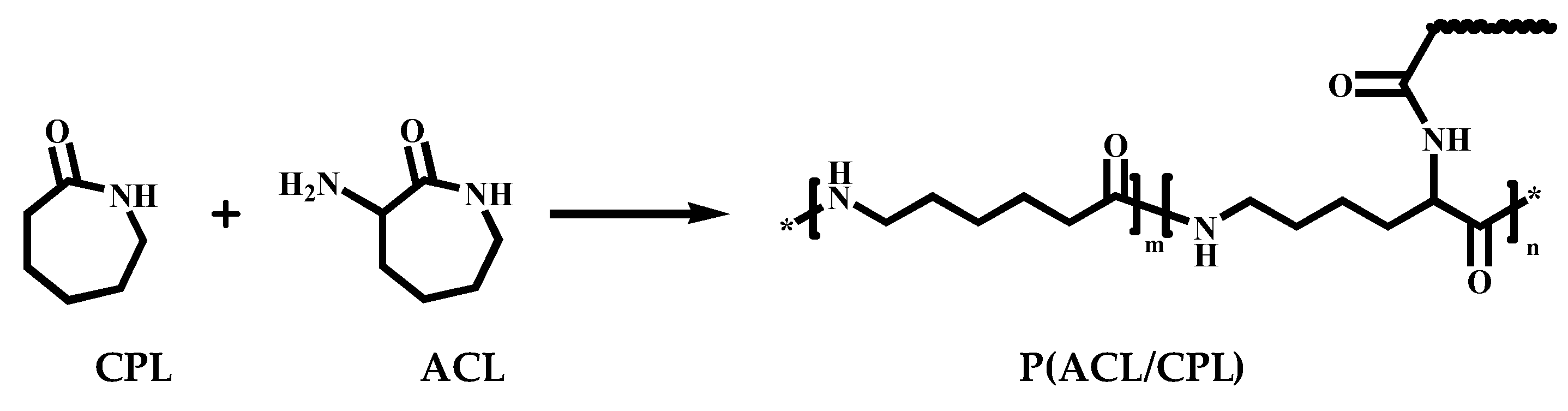

Figure 1.

The co-polymazation of CPL and ACL.

Figure 1.

The co-polymazation of CPL and ACL.

In our previous work, we successfully synthesized

α-Amino-ε-caprolactam (ACL) by cyclizing lysine.[

13] ACL has a similar structure to CPL, but amino group at the α position contributes to bifunctionality after hydrolysis. In this study, we copolymerized CPL and ACL through hydrolytic ring-opening polymerization at different ACL/CPL ratios, and successfully prepared a modified nylon 6, named P(ACL/CPL), with long-chain branched structure(Scheme 1). The structure of P(ACL/CPL) was characterized by

1H NMR and

13C NMR spectra, which confirmed the feasibility of copolymerization and the generation of branched structures, and predicted the reaction mechanism. The rheological properties of the P(ACL/CPL) copolymer was tested using the rotational rheometer, and its thermodynamic characteristics were determined using the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Finally, the tensile behavior of P(ACL/CPL) was tested, and the optimal ratio of caprolactam to ACL was determined based on the results of rheological and thermodynamic tests.

3. Results

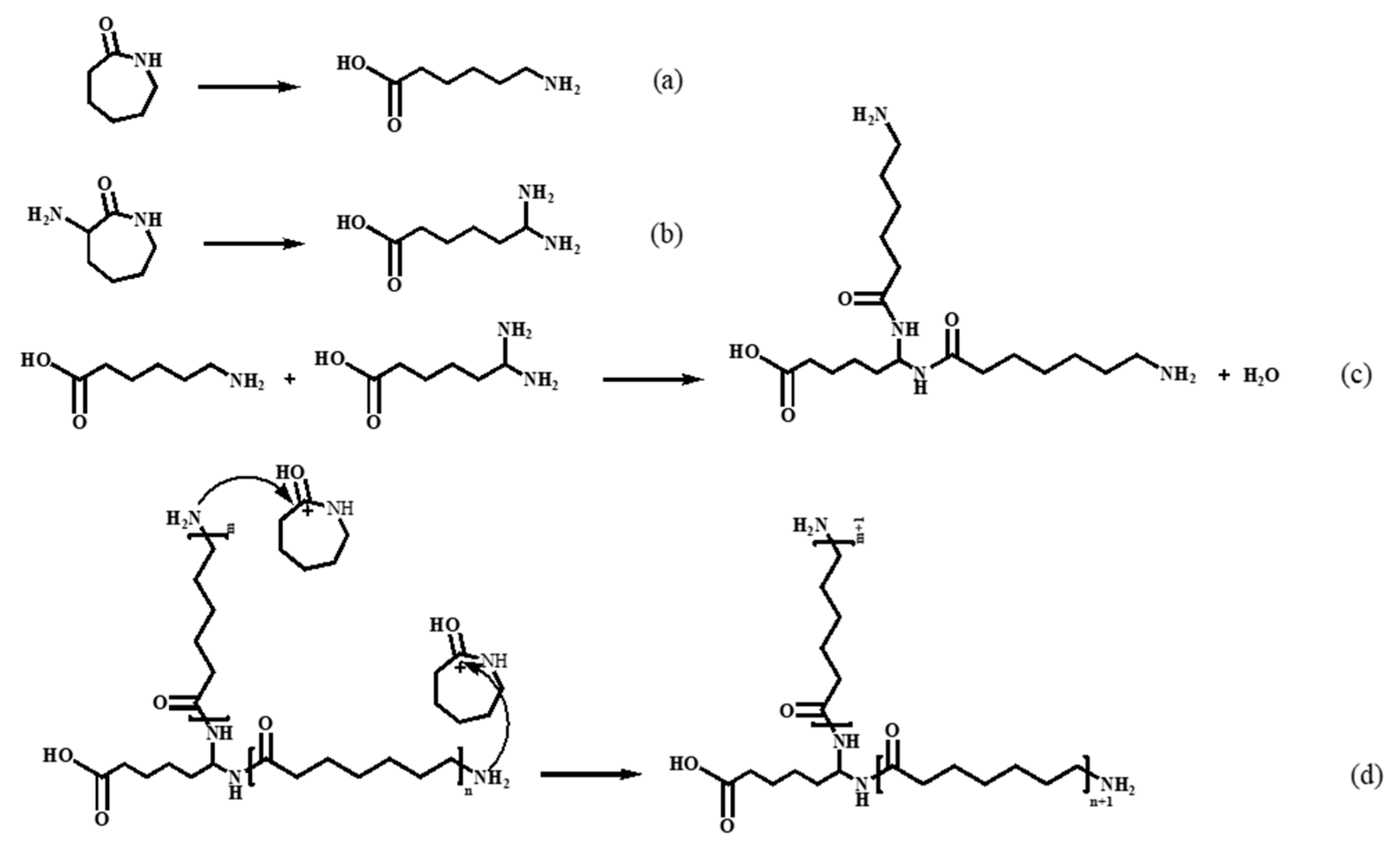

The reaction mechanism of nylon 6 synthesis via hydrolytic ring-opening polymerization of caprolactam is well-understood. Under high temperature and water conditions, the amide bond of caprolactam undergoes cleavage, resulting in the formation of aminocaproic acid(

Figure 2(a)). Aminocaproic acid can undergo condensation to form short-chain polyamide. The terminal amino group of the short-chain polyamide attacks the carbonyl carbon of the CPL monomer's amide bond, directly adding the CPL monomer to the polymer chain and achieving chain growth. [

29] For our co-polymer system, the reaction progress and mechanism can be shown in

Figure 2. ACL was supposed to have the similar properties to CPL so that its amide bond can also cleavage to form linear molecule(

Figure 2(b)). A small account of ring opening products of CPL and ACL can undergo polycondensation to form low molecular weight polymers with main chain and side chain(

Figure 2(c)). The terminal amino groups in both main chain and side chain of the polymer can react with the monomers protonated by carboxyl groups leading to chain addition(

Figure 2(d)).

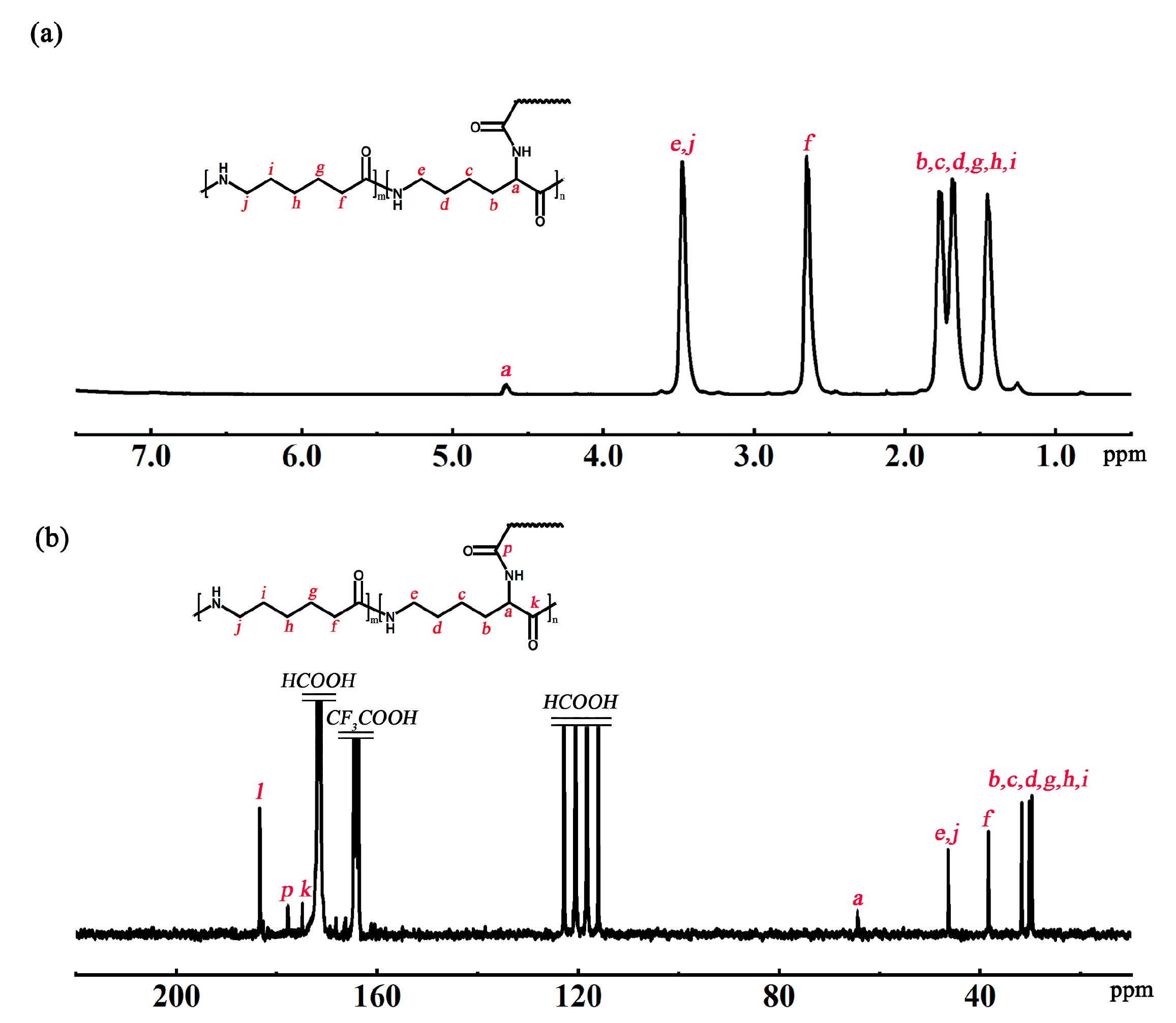

The chemical shifts of H atoms and C at branching sites were determined by

1H NMR and

13C NMR, respectively, to determine the structure of the P(ACL/CPL) co-polymer. The structural formula and

1H NMR spectrum of P(ACL/CPL) are shown in

Figure 3(a), with the chemical shifts of H atoms as follows: δ4.63 (branching site), δ3.42, 2.58, 1.45-1.78 (main chain and side chain). The structural formula and

13C NMR spectrum of P(ACL/CPL) are given in

Figure 3(b), with the chemical shifts of C atoms as follows: δ65.2 (branching site), δ3.42, 2.58, 1.45-1.78 (main chain and side chain).

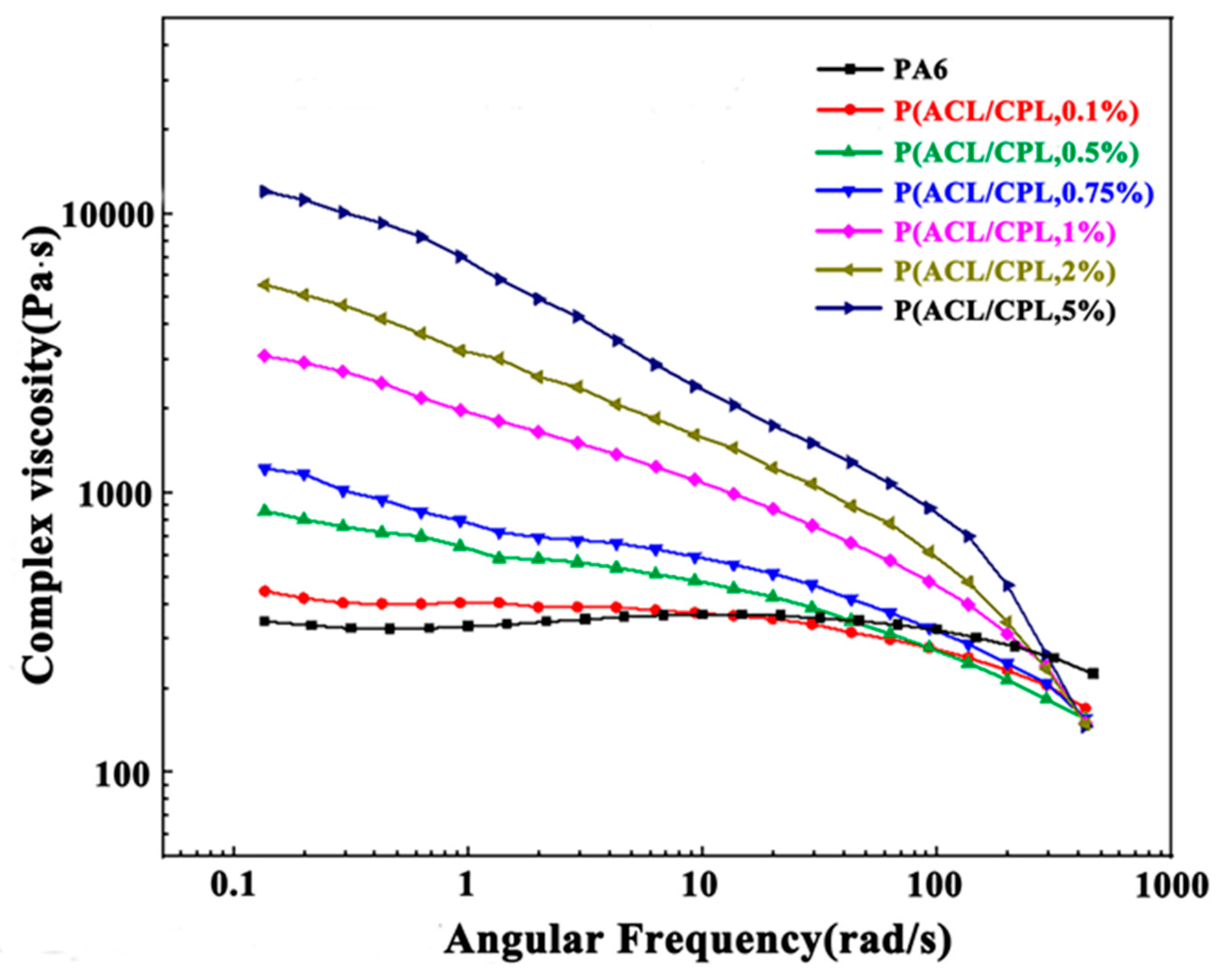

The rheological properties of polymers, highly sensitive to the changes in molecular chain, can be used to reveal chain structure of polymers.[

15] The complex viscosity (η) of pure PA6 and our co-polymer samples as a function of angular frequency (ω) is shown in

Figure 4. With linear molecular chain structure, pure PA6 complex viscosity showed little change with angular frequency increased, and the the η-ω curve of which showed a clear Newtonian plateau. After the addition of ACL, the complex viscosity of the co-polymers decreased significantly with the increase of angular frequency, and the Newtonian plateau in the η-ω curve disappeared as shear thinning phenomenon occured. Moreover, the more ACL was added, the more pronounced the shear thinning became. The above phenomena was consistent with the changes in rheological properties of long-branched samples. Zero shear viscosity is the complex viscosity of a sample when the shear rate tends to zero and the system approaches an equilibrium state, which can reflect the characteristic structural of the sample in an equilibrium or near-equilibrium state. [

16]For linear polymers, the zero shear viscosity is related to the relative molecular weight of the sample, and the relationship between the relative viscosity of PA6 and the relative molecular weight follows a power law of 3.4 [

17](shown as Equation 2)

where η

0 represents zero shear viscosity, M

w represents relative molecular weight, and

k represents temperature-dependent constant. From the law, we can see that a larger zero shear viscosity corresponds to a higher molecular weight. However, with the addition of ACL, the molecular weight of the co-polymers first remains unchanged and then decreases. This indicates that the structure of the co-polymers is no longer linear. The zero shear viscosity of the co-polymers can be calculated through the simple Carreau equation with Cox-Merz rule[

18]

where η

0 is the zero shear rate viscosity, γ is the shear rate, τ

n is the characteristic time, and n is a parameter. From

Table 1, we can see that after the addition of ACL exceeds 1wt%, the zero shear viscosity of the co-polymer increased significantly. This is because under near-equilibrium conditions, the viscosity of the material is mainly influenced by long branches with longer relaxation times. The entanglement of long branches hinders the movement of chain segments, resulting in an increase in zero shear viscosity of long-branched samples compared to linear chains with the same molecular weight. In addition, due to the longer relaxation time corresponding to long branches, it means that it takes a lower deformation rate to fully relax them. Therefore, compared to linear chains with the same molecular weight, systems containing long branches start to exhibit a phenomenon of viscosity decrease at lower deformation rates, known as shear thinning phenomenon. [

19,

20,

21,

27]Generation of a gel structure can be another possible reason for the significant increase in zero shear viscosity. Though three dimensionally crosslinked polymers are incapable of macroscopic viscous flow ,but the crosslinked chains can flow with other chains when the added amount of ACL is very small. However, it was checked that all co-polymer can completely soluble in formic acid with no remaining particles by the particle size analyzer. In addition, the crosslinked section is infusible in the melt, but the melt we observed in the experiment was all homogeneous[

28].

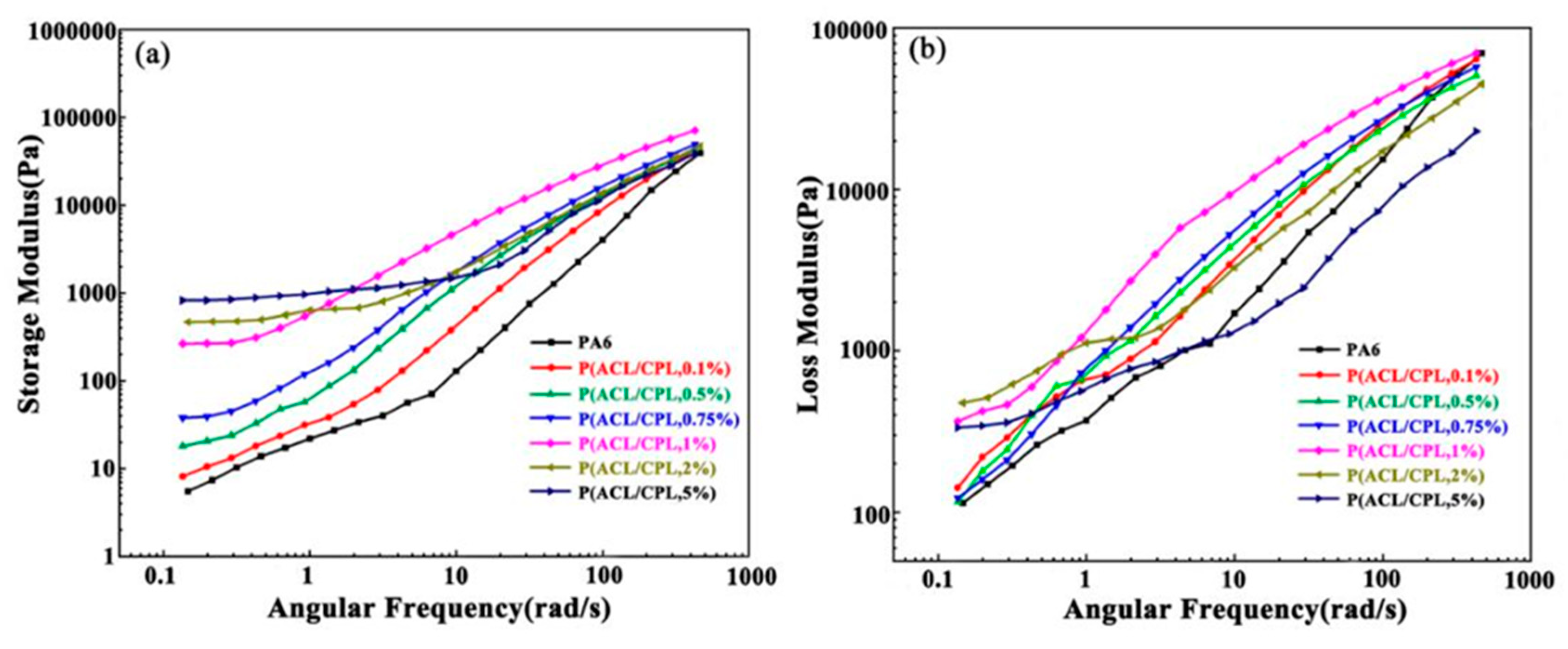

Storage modulus, loss modulus, and loss factor are also important rheological parameters reflecting the structure of the sample. The storage modulus reflects the elasticity of the sample, that is, the ability of the sample to maintain its original shape after being subjected to an external force, manifesting as solid-like behavior. The higher the storage modulus, the stronger the ability of the sample to maintain its original equilibrium state after being subjected to an external force, and the longer the time it takes to return to its original equilibrium shape after the same deformation, which can also be referred to as the relaxation time. On the other hand, the loss modulus reflects the viscous response of the sample, with a higher loss modulus indicating stronger liquid-like behavior.[

22]According to linear viscoelastic theory, at the low-frequency region, pure linear PA6 exhibited terminal behavior, that is, the storage modulus and loss modulus have the following relationship with angular frequency: [

23]

According to the relationship, in the double logarithmic coordinate system, the slope of the linear pure PA6 G’

- ω curve approaches 2 at low-frequency region. As shown in

Figure 5(a), the slope of the PA6 curve was consistent with the above, while with the addition of cycloaliphatic lysine, the slope of the G’

- ω curve at the low-frequency region for our co-polymers gradually decreased from 1.75[P(ACL/CPL,0.1%)] to 0.17[P(ACL/CPL,5%)], deviating from the linear end behavior. Meanwhile, the storage modulus value increased by nearly 200 times, reflecting that with the addition of ACL, the long-chain branching structure in the co-polymers increased, the degree of molecular entanglement raised, and the sample's solid-like properties were enhanced, corresponding to a longer relaxation time.

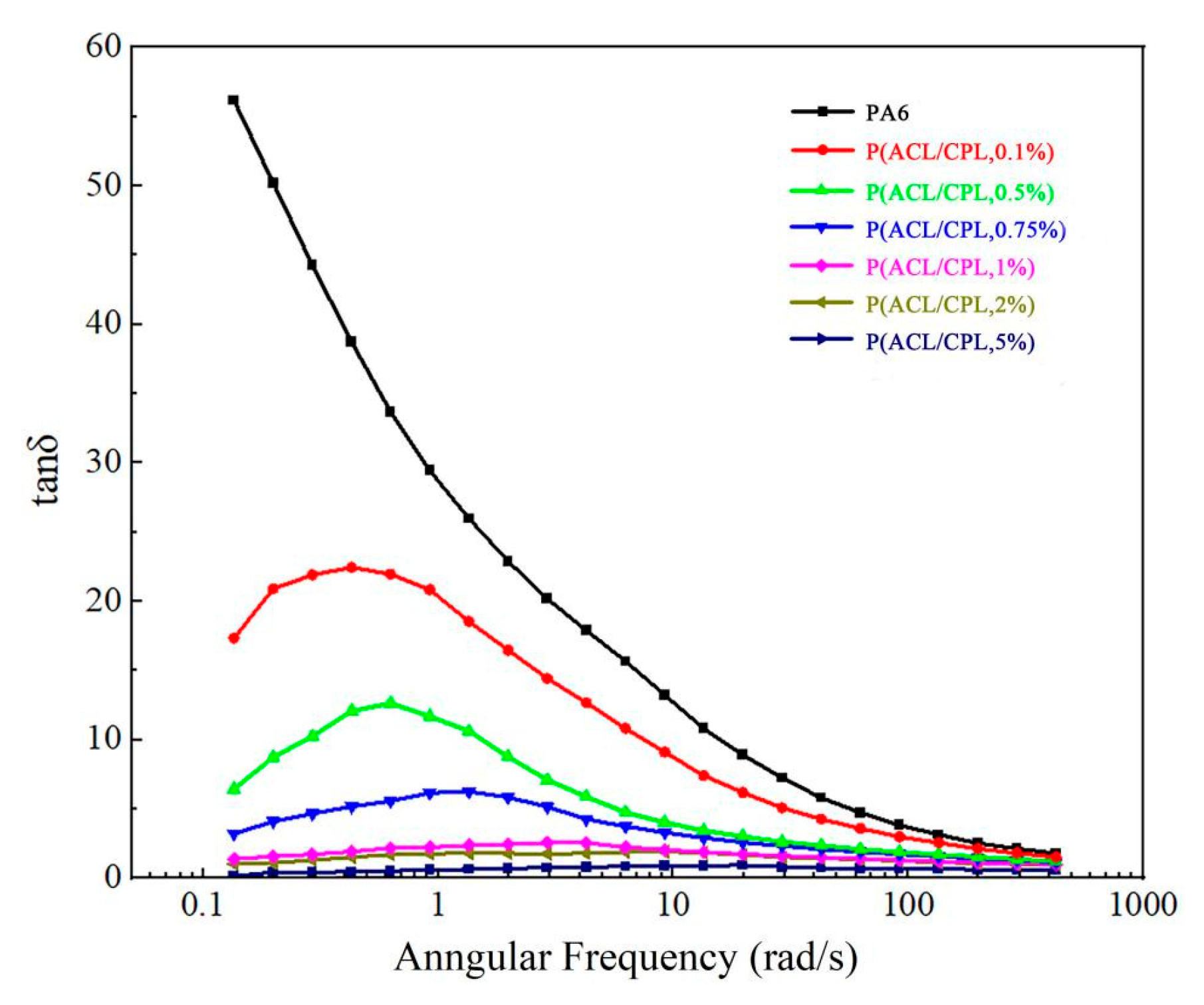

The loss factor tanδ is the ratio of the loss modulus to the storage modulus (tanδ = G’’/ G’), and its inverse trigonometric function is the loss angle. As the loss factor approaches zero, it indicates that the material is nearing purely elastic behavior while as the loss factor approaches infinity, it indicates that the material is nearing purely viscous behavior. The formation of branches is also reflected in the changes of the loss factor and loss angle. [

24]

Figure 6 shows the tanδ-ω curves for pure PA6 and our co-polymers with different contents of ACL. For pure PA6, the loss factor tanδ increased with the decrease of ω, and the curve raise sharply at the low-frequency end, which was a typical liquid-like terminal behavior of linear molecular chains. With the addition of ACL, branched structure formed in the sample, and the tanδ decreased in the low-frequency region, with the curve beginning to show an inflection point. Moreover, as the co-polymerization amount of ACL increased, the tanδ continued to decrease, and the tanδ-ω curve gradually formed a plateau in the low-frequency region. This is consistent with the findings of Graebling et al. [

25], who believed that the storage modulus of the sample is more sensitive to the formation of branches, and a small amount of branching can cause a significant increase in the storage modulus, while the loss modulus is less sensitive to this, hence the magnitude of tanδ is mainly influenced by the changes in the storage modulus. With the formation of branches, there is a significant increase in the storage modulus in the low-frequency region, while the change in the loss modulus is relatively small, therefore tanδ begins to decline in the low-frequency region At the same time, the presence of branches enhances the relaxation time of the sample at the low-frequency end, and the storage modulus of the sample gradually stabilizes, hence the tanδ-ω curve shows a plateau.

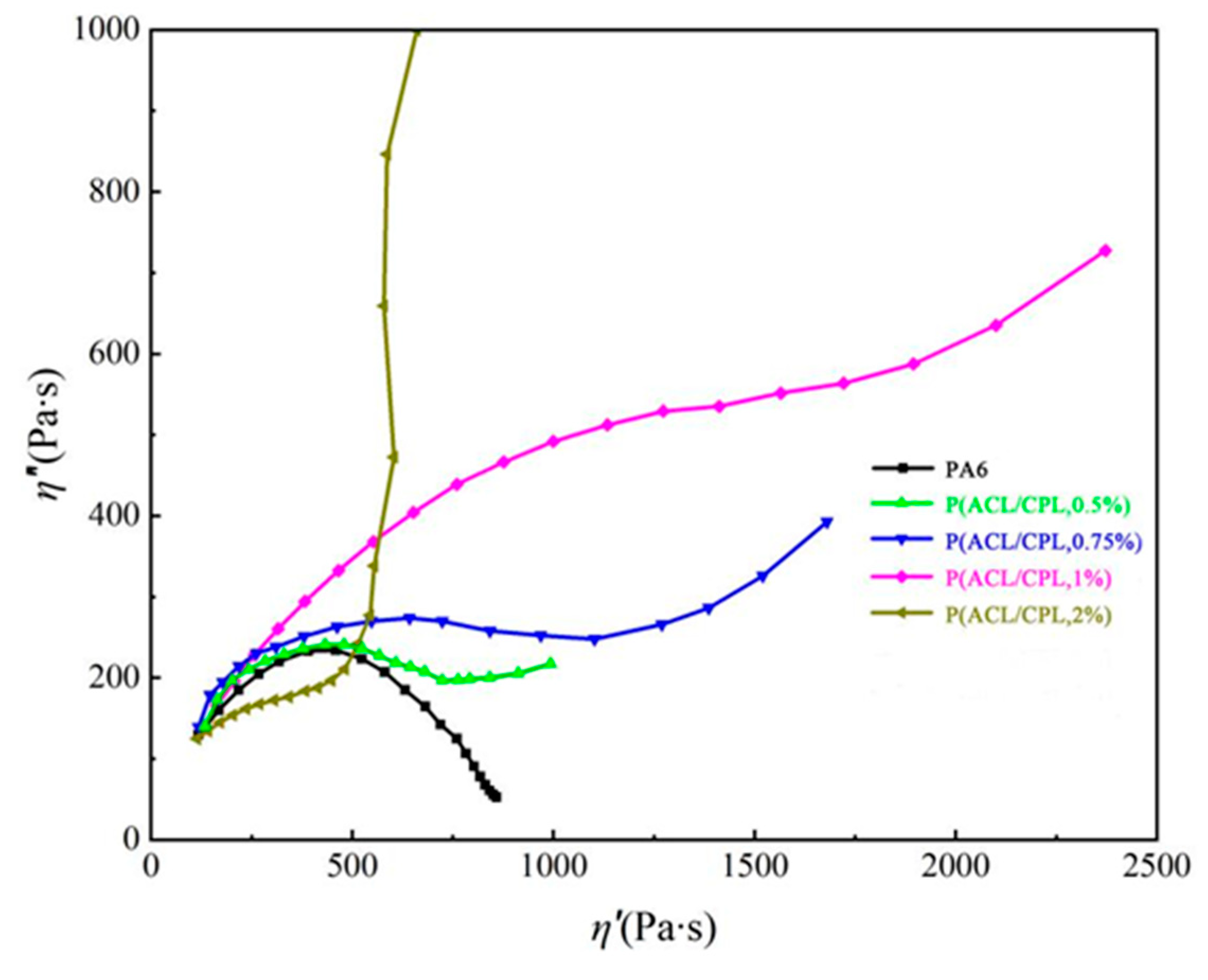

The Cole-Cole plot is a graph that represents the relationship between the imaginary viscosity η’’ (η’’ = G’/ω) and the real viscosity η’ (η’ = G’’/ω) of a sample. The deflection of the Cole-Cole plot curve can be used to characterize the relaxation time and relaxation mechanism of polymer samples. [

26]For samples with linear molecular chain structures, their Cole-Cole curves are close to semicircular. In

Figure 7, the Cole-Cole curve of PA6 is close to semicircular, which is consistent with the conclusion. With the generation of branches, the Cole-Cole curve of the N-PA6 sample gradually deviates from the semicircular shape, and the curve begins to turn up at high η’, that is, in the low-frequency region, indicating that the relaxation process of the sample is extended, the relaxation time of the system increases, and the greater the amount of co-polymerized ACL, the greater the semicircular deflection of the corresponding curve, with more branched structures corresponding to longer relaxation times.

The end-group test results of the co-polymers are shown in

Table 1. When the amount of ACL was less than 1%, the carboxyl group concentration was similar, around 65mmol/kg. When the amount of ACL exceeded 1%, the carboxyl group concentration increased, which was due to a significant decrease in molecular weight. The end-amine concentration of the copolymer significantly increased with the addition of ACL, as well as the ratio of end-amine to end-carboxyl groups. Based on the mechanism of branching mentioned above, this is because the addition of ACL increases the number of branches, and each branch end is also an amino group, resulting in a significant increase in amino group concentration.

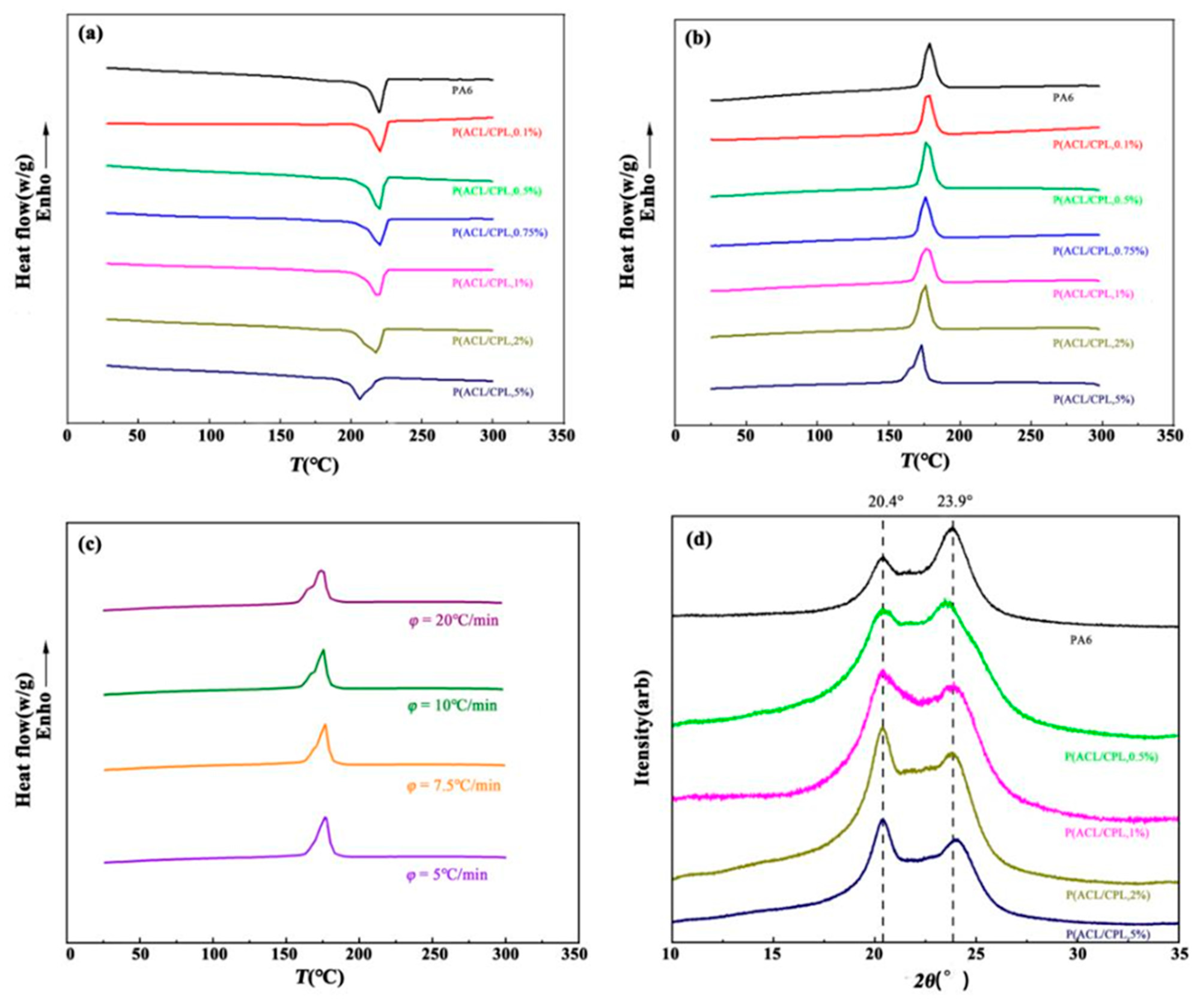

The thermal properties of the co-polymers were determined by DSC scanning, as shown in

Figure 8(a)(b) and

Table 2. It can be seen that the melting point of the samples significantly decreases when the amount of ACL exceeds 1wt%. The crystallization process of the samples is more sensitive to the addition of ACL, as the crystallization temperature and degree of crystallinity decrease significantly, and the crystallization peak becomes broader. This is because the addition of a small amount of ACL disrupts the regularity of the molecular chains, and the presence of some shorter side chains reduced the chain migration rate, hindering the crystallization of the samples [

30].

When the ACL content is 5%, the co-polymer exhibited a double crystallization peak, which may be due to different crystallization temperatures of different segments in the copolymer, or the presence of more side chains and network structures in the polymer, under the cooling rate of 10℃/min, the molecular chains responded insufficiently, resulting in incomplete folding and arrangement of the molecular chains, leading to different crystalline forms. [

31]Therefore, we conducted cooling crystallization tests on the co-polymers at different cooling rates, and the cooling curves obtained are shown in

Figure 8(c). The double crystallization peak becomes more pronounced when the cooling rate is increased to 20℃/min, while the crystallization peak becomes a single peak when the cooling rate is reduced to 5℃/min. This indicates that the double peaks observed in the cooling crystallization curve at higher cooling rates are due to the slow response of the molecular chains to the fast cooling rate, and the difference in crystallization temperature of different side chains in the sample is not significant.

Figure 8(d) shows the X-ray diffraction characterization results of the copolymers with different ACL contents. It can be seen that although the addition of ACL affects the crystallinity of the samples, the crystal structure of the samples remained unchanged, and all samples exhibit characteristic peaks at 20.4° and 23.9°, corresponding to the α-crystal form of nylon 6.

Table 3.

The tensile mechanical properties of PA6 and P(ACL/CPL) co-polymers.

Table 3.

The tensile mechanical properties of PA6 and P(ACL/CPL) co-polymers.

| entry |

feed CPL/ACLmass ratio |

yield strength

(MPa) |

tensile strength

(MPa) |

fracture elongation

rate (%) |

| 1 |

0 |

51.55 |

42.52 |

250.24 |

| 2 |

0.1/100 |

51.93 |

50.12 |

300.02 |

| 3 |

0.5/100 |

52.07 |

55.42 |

312.24 |

| 4 |

0.75/100 |

52.66 |

58.84 |

318.27 |

| 5 |

1/100 |

52.87 |

62.27 |

358.24 |

| 6 |

2/100 |

54.25 |

51.92 |

320.52 |

| 7 |

5/100 |

58.20 |

58.20 |

66.67 |

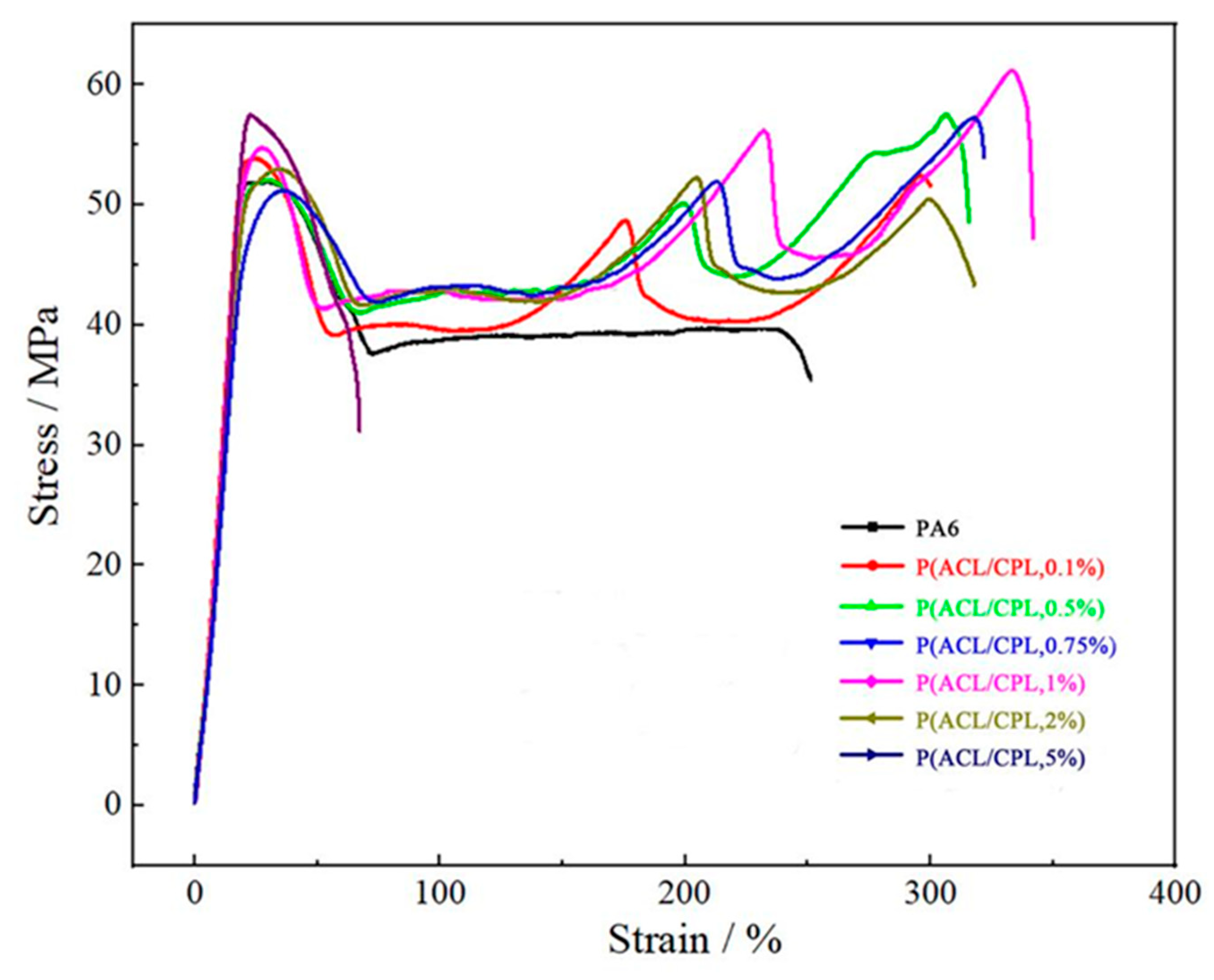

Figure 9 shows the stress-strain curve during the tensile process of co-polymers with different ACL contents. It can be seen that the stress decreased after the yield point of pure nylon samples, and then remained constant until the sample fractures, which was the tensile strength. With the addition of ACL, the stress plateau after yield became shorter, and then increases with strain, experiencing 2-4 times increment. When the ACL content did not exceed 1wt%, the tensile strength of the samples increased with the ACL content, and was always greater than the yield strength, indicating the occurrence of strain hardening. When the ACL content was 2%, the stress after yield also increasd multiple times with strain, but the ultimate fracture strength was lower than the yield strength, indicating no strain hardening phenomenon. When the ACL content was 5%, the sample fractured quickly after yield. With the addition of ACL, the change in co-polymers yield strength was not significant, but the tensile strength and fracture elongation rate significantly increased when the ACL content was below 1wt%, indicating enhanced toughness of the samples. After the ACL content exceeded 1wt%, the tensile strength and fracture elongation rate decreased. Typically, for linear polymers, the tensile strength and fracture elongation rate decreased with decreasing crystallinity. The addition of ACL reduced the crystallinity but increased the branching, resulting in more chain entanglements. During the tensile process, the entangled chains rearrange and gradually untangled after yield, requiring further energy barrier overcoming, thus the stress gradually increased. [

32]When the ACL content exceeded 2%, the molecular weight of the co-polymers started to decrease significantly, leading to a decrease in the subsequent tensile strength and fracture elongation rate. Comparing the tensile properties of co-polymers with different ACL contents, P(ACL/CPL,1%) exhibited the best tensile mechanical properties.