1. Introduction

Sleep problems is one of the most common complaints in medical practice. Non-restorative or inadequate sleep can interfere with normal functioning in the physical, mental, and social spheres of life [

1]. Sleep disorders may have a profound impact on the overall health and quality of life, which in turn are associated with high odds of multimorbidity including psychiatric and non-psychiatric diseases [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Although disturbed sleep is easy to diagnose with many self-assessment instruments for aid, sleep disorders are still underrecognized and undertreated in a substantial number of patients, particularly those presenting to physicians with other comorbid medical diseases [

7,

8] or in many patients who experience sleep problems and did not report them to their doctors [

9]. There is a complex interplay with interactive and bidirectional relationships between insomnia and many psychiatric disorders, with the severity of sleep disturbance showing a correlation with the severity of the mental illness [

4]. However, in clinical practice, clinicians are faced with the challenge of the possibility of sleep disturbance considered as an epiphenomenon that will disappear once the primary mental disorder is treated or as a valid stand-alone clinical entity [

9].

Sleep problems and stress are two conditions, which are strongly associated and appear to be pathophysiologically integrated, as the occurrence of stress increases the risk of insomnia, insomnia exacerbates stress, and the coexistence of both conditions has a negative influence on their prognosis [

10,

11]. Mental stress and poor sleep quality are interlinked outcomes among university and college students in academic settings [

12]. Also, it has been shown that healthy individuals and good sleepers are prone to experience situational sleep problems and insomnia under stressful life conditions [

13].

Symptomatic treatment of insomnia includes sleep hygiene combined with pharmacological modalities especially benzodiazepines [

14,

15]. However, sleep medications improve short-term outcomes but have significant adverse effects and may be addictive. Non-pharmacological therapies have been extensively advocated in the management different psychiatric and psychological symptoms of stress, particularly to overcome the negative side effects of conventional pharmacotherapy.

Complementary and alternative medicine strategies based on dietary supplements and popular herbal remedies have progressively gained attention to improve symptoms of either stress or sleep problems, particularly as multimodal interventions used by subjects seeking adjunct non-pharmacological natural therapies [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Among the potential herbs available,

Aloysia citrodora Paláu (

Lippia citriodora Kunth), commonly known as "lemon verbena" has shown multiple biological activities, including antioxidant, anxiolytic, neuroprotective, anticancer, anesthetic, antimicrobial, and sedative effects, which have been mainly attributed to verbascoside, an abundant polyphenol found in lemon verbena leaves [

20,

21,

22]. The mechanisms by which lemon verbena exerts its beneficial properties involve binding of the GABA-A receptor, modulation of cAMP and calcium channels, and increased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine [

23,

24,

25,

26].

In relation to the potential anxiolytic and sedative effects of the plant, a recent study in 40 subjects with anxiety and sleep problems randomly assigned to supplementation with an extract of lemon verbena (

Lippia citriodora) or placebo for 8 weeks followed by a 4-week washout period, showed that subjects assigned to the intervention group experienced lower stress levels and reported to sleep better [

27]. The present clinical trial was conducted to add further evidence of the efficacy of an extract of

Aloysia citrodora to alleviate poor sleep quality in a population of healthy subjects who received dietary supplementation with the nutraceutical formulation of lemon verbena or placebo for 90 days. Also, the effect of the extract in melatonin production was elucidated in the current study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled and single-center clinical trial with two parallel arms was carried out at the Health Sciences Department of Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (UCAM), in Murcia, Spain. The study period was from 4 April to 27 July 2023. The primary objective of the study was to assess the effect of a nutraceutical formulation of lemon verbena consumed for 90 days on improving sleep quality in healthy individuals who reported sleep problems as their major complaint. Secondary objectives included changes in plasma cortisol levels and nocturnal melatonin levels associated with the use of the experimental product, and safety.

Participants were recruited by advertising the study through mass media, social networks, and e-mails lists of the UCAM research institution. Eligibility included subjects of both sexes, aged 18 years or older, with poor sleep quality assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), moderate level of anxiety assessed by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and able to complete the study procedures. Participants were excluded if at least one of the following criterion were fulfilled: severe or terminal illness; body mass index (BMI) > 32 kg/m2; cognitive impairment due to organic diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease); use of drugs that may affect cognitive performance or sleep quality, such as anticonvulsants, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, neuroleptics, alcohol and drugs of abuse; known allergy to any of the study components; pregnant and breastfeeding women; participation in another clinical trial that included blood sampling or a dietary intervention; and inability to provide informed consent.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (code CE032302, approval date 30 March 2023) (Murcia, Spain) and was registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06154629). All participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Randomization, Intervention and Study Procedures

Participants were randomized to the intervention (experimental) group or the placebo group using a simple randomization procedure (1, 1) with the Epidat version 4.1 software program by an independent center.

The investigational product consisted of a purified extract of lemon verbena leaves (

A. citriodora) standardized in a minimum of 28% total phenylpropanoids, of which 24% minimum corresponds to verbascoside (commercially known as PLX or RelaxPLX, as in a previous study [

27]). Each capsule contained 400 mg of lemon verbena and 150 mg of excipient (cellulose microcrystalline). Placebo capsules contained cellulose microcrystalline and maltodextrin and had the same organoleptic properties as the investigational product. All participants were instructed to take 1 capsule per day of the assigned supplement, 1 hour before sleeping for 90 consecutive days.

The dietary supplement was provided at the baseline visit and at the mid-study visit (day 45) and subjects were required to consume at least 80% of the capsules, so that only 18 capsules could be left in total corresponding to 18 days out of 90 days of consumption. Subjects were advised of not introducing changes in their dietary habits or levels of physical activity. The use of any new medication should be reported to the principal investigator.

The study included a screening visit, a baseline visit (visit 1), a mid-study visit at 45 days (visit 2), and a final visit at 90 days (visit 3) at the end of the study. The screening visit took place within ± 10 days prior to the baseline visit, in which the inclusion criteria were checked and the written informed consent was obtained. Patients were also randomized to one of the study groups.

At the baseline visit (visit 1), data recorded were medical history; physical examination; vital signs; body weight and height; quality of sleep according to the PSQI questionnaire, the VAS score, and actigraphy-based sleep parameters; level of stress using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and anxiety using the STAI questionnaire; body composition by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA); and level of physical activity. Laboratory tests included plasma cortisol levels, nocturnal melatonin levels, and standard hematological and biochemical parameters. The dietary supplement was provided at the baseline visit.

At the mid-study visit (45 days, visit 2), study procedures of the baseline visit were repeated except for laboratory tests. The remaining dietary product was collected and compliance was calculated. Subjects received the assigned product for additional 45 days of treatment and adverse events (AEs) were registered. At the final visit (90 days, visit 3), the same study procedures as those of the baseline visit were performed. The investigational product was collected and compliance was calculated. AEs were recorded.

2.3. Study Variables

A 10-cm unnumbered VAS scale was used to assess sleep quality in the past month, where 0 was ‘very poor sleep quality’ and 10 ‘very good sleep quality’. The score was determined by measuring the distance on the 10-cm line between the ‘very poor sleep quality’ anchor and the subject’s mark. VAS scores < 5 indicated a poor-moderate sleep quality, whereas scores > 6 indicated moderate-good sleep quality.

The PSQI is a short self-report questionnaire and the most widely used subjective measure of sleep quality over an interval of 1 month. The instrument measures seven dimensions from 0 (best) to 3 (worst). These seven components can be broadly categorized into sleep efficiency factors (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, and habitual sleep efficiency) to which sleep disturbing factors (sleep disturbance, use of sleep medications, and daytime disturbance) can be added. Adding up the average scores of the seven components gives a global PSQI score from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate worse sleep quality. In this study an overall PSQI score > 5 was required. A Spanish-validated version of the PSQI was administered [

28].

Sleep quality was measured during 24 hours using a wrist-worn accelerometer (ActiGraph wGT3X-BT accelerometer, ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL, USA) during 3 days of the week and 1 day of the weekend, at the baseline visit and after 45 and 90 days of consumption of the dietary product. The following variables were recorded: sleep latency, sleep efficiency, total time in bed, total sleep time, wakefulness after sleep onset, number of awakenings, and average number in minutes of awakenings.

The STAI questionnaire measures state (STAI-state) and trait (STAI-trait) of anxiety based on 20 questions for each domain, scores can vary between 0 and 60 with higher scores indicating greater anxiety levels. Scores 0–9 indicate normal or no anxiety, 10-18, mild to moderate anxiety, 19-29, moderate to severe anxiety; and 30–60, severe anxiety. A Spanish validated version was used [

29].

The PSS scale includes 14 items measuring the frequency or extent of a certain stress-signaling event occurrence of a 5-point scale. Total perceived stress level score ranges between 0 and 56, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress over the previous month. A Spanish validated version was used [

30].

A whole body bioimpedance analyzer (Tanita BC-420MA, Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was used to determine corporal composition (weight, body mass index [BMI], fat mass [expressed in kg], percentage of fat mass, and muscle mass [expressed in kg]). The level of physical activity was evaluated with the accelerometer used to assess sleep quality, with results expressed as metabolic equivalents (METs).

Plasma cortisol levels were measured in blood samples taken early in the morning, and nocturnal melatonin levels in samples taken late in the evening. Results were expressed as pg/mL. Safety data included blood pressure recording and laboratory analyses. Standard hematological (hemogram) and biochemical parameters (renal and liver function tests) were measured.

2.5. Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was the change from baseline to the end of study (90 days) in the quality of sleep measured by VAS in the experimental arm (lemon verbena) as compared with the placebo arm. Secondary endpoints were changes in sleep quality measured by the PSQI and actigraphy as well as changes in PSS, STAI, plasma cortisol and nocturnal melatonin levels after 90 days of consumption of the dietary supplement. Safety endpoints were anthropometric variables, level physical activity, vital signs, laboratory values, and AEs.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data of all participants who met the eligible criteria and completed the 90-day study period were analyzed. Categorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous data as mean and standard deviation (± SD). Differences in the distribution of variables between the experimental and control groups were analyzed with the chi-square (χ2) test for qualitative variables and the Student’s t test for quantitative variables. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was used to assess the change of variables corresponding to each group throughout the study period. The subject factor included data at baseline, at the mid-study visit (45 days), and at the final visit (90 days) and the between-subject factor for paired data included the product administered, that is lemon verbena or placebo. Turkey’s or Bonferroni’s correction was applied for post-hoc analyses. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with the SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) software program.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

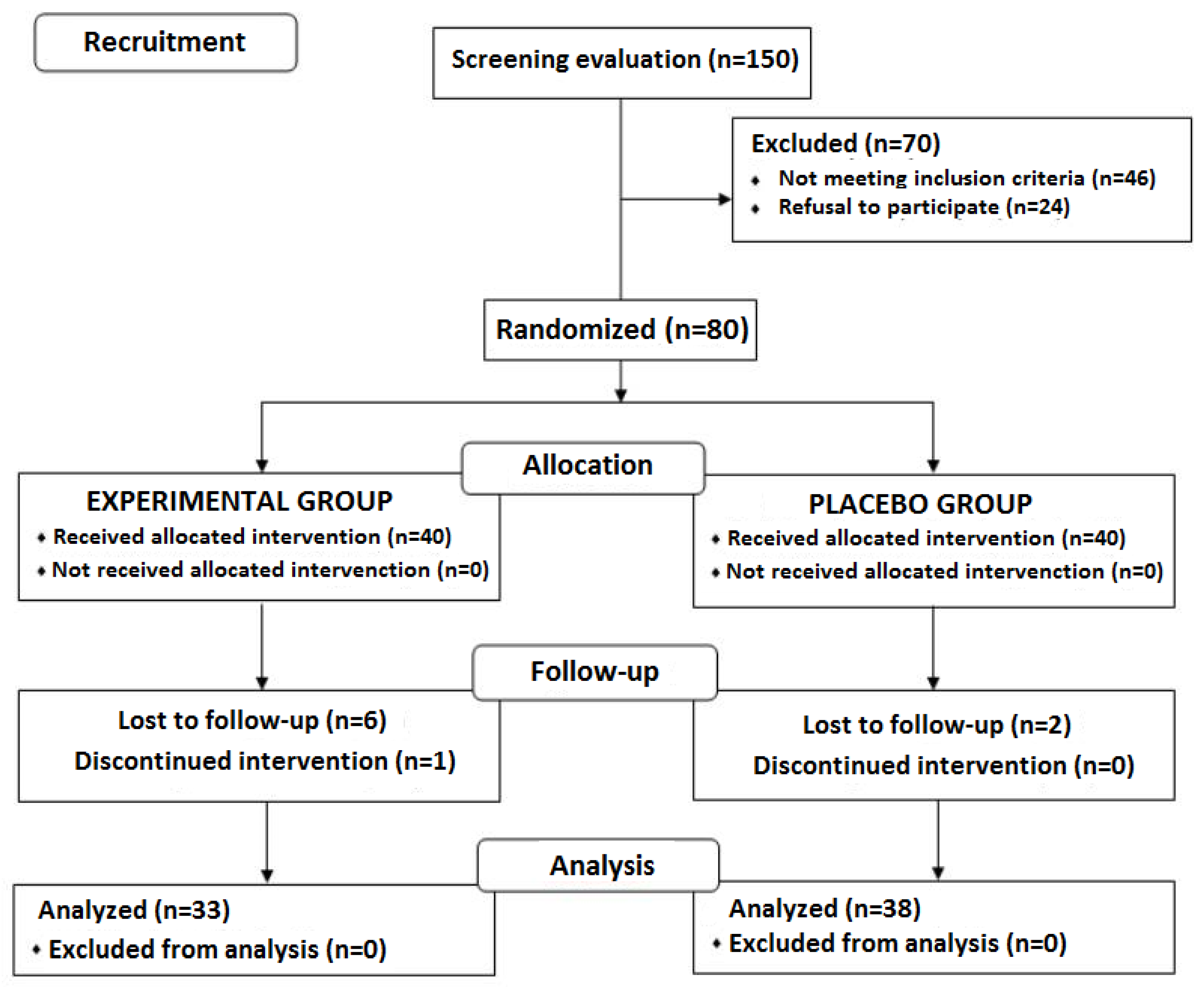

Of a total of 150 subjects who were initially selected for the study, 80 were eligible. Seventy subjects were excluded because inclusion criteria were not met in 46 and refusal to participate in the remaining 24. Of the 80 eligible subjects, 40 were randomized to the experimental (lemon verbena) group and 40 to the placebo group. During the intervention period, 9 subjects were lost to follow-up, 7 from the experimental group and 2 from the control group. The final study population included 71 subjects (33 in the experimental group and 38 in the placebo group). The flow chart distribution of participants is shown in

Figure 1.

Regarding the baseline characteristics of participants, the mean age was 29.5 ± 11.2 years and the mean weight 70.8 ± 15.6 kg. The mean VAS score of sleep quality was 3.7 ± 1.7, and the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure 114.5 ± 12.0 and 74.6 ± 7.4 mmHg, respectively. Differences in baseline data between the study groups were not found (

Table 1).

3.2. Sleep Quality

3.2.1. VAS Scores

Changes of VAS scores of the quality of sleep in the previous month rated by subjects assigned to the experimental and placebo groups throughout the study are shown in

Table 2. The sleep quality improved significantly in both study groups in the comparison between values recorded at baseline and at the mid-term and final visits. However, the use of the interventional product over 90 days was associated with a statistically significant greater improvement in the quality of sleep as compared with placebo (

p = 0.021).

3.2.2. PSQI Scores

After 45 days of consumption of the assigned dietary supplement, there was an improvement in the overall score and all components of the PSQI questionnaire as compared with baseline. At the end of the study (90 days), the comparison of the overall score, sleep latency, and sleep efficiency between the experimental and the placebo groups showed significant differences (

p < 0.05) in favor of the experimental group. Sleep latency also improved significantly between visit 2 at 45 days and visit 3 at 90 days in the experimental group (

p = 0.042). Subjects assigned to the experimental group showed statistically significant differences as compared with placebo over the study period in the overall score of the PSQI questionnaire as well as in the domains of sleep latency and sleep efficiency (

Table 3).

3.3.3. Actigraphy

Results of actigraphy sleep studies are shown in

Table 4. Participants assigned to the experimental group as compared to those treated with placebo had statistically significant improvements in the four domains of sleep latency, sleep efficiency, wakefulness after sleep onset, and mean number of awakenings at the final visit on day 90. Moreover, between-group statistically significant differences for these four sleep domains were observed at the final visit on day 90. In the remaining domains of total time in bed, total sleep time, and number of awakenings, differences between the study groups as well as within each group during the study period were not detected.

3.4. Perceived Stress and Anxiety

As shown in

Table 5, the PSS total score showed a decreasing trend over the study period, which was of a greater magnitude in the experimental group (mean decrease of 9.1 points) as compared with the placebo group (mean decrease 5.8 points), although between-group differences were not statistically significant. In relation to anxiety levels, subjects assigned to the experimental group showed a statistically significant decrease of scores in the STAI-state scale as compared with placebo (

p = 0.037), whereas changes in the STAI-trait scale were not observed (

Table 5).

3.5. Plasma Cortisol and Nocturnal Melatonin Levels

As shown in

Table 6, plasma cortisol levels did not change in any of the study groups, whereas plasma nocturnal melatonin levels increased significantly in the experimental arm as compared with placebo.

3.6. Anthropometric Variables and Level of Physical Activity

Changes in anthropometric variables measured by BIA and levels of physical activity were not statistically significant in any of the study groups over the 90 days of administration of the dietary supplement (

Table 7).

3.7. Compliance and Safety

All participants consumed at least 80% of the study product. The maximum number of capsules returned was 12, with compliance ranging between 100% and 86.6%. Changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate during the study period were not observed. Also, the results of laboratory tests remained within the normal ranges. AEs related to consumption of the study product were not observed.

4. Discussion

In the present study group of 71 of adult subjects with low sleep quality (mean VAS score of 3.6 and mean PQSI score of 10.4 al baseline), the administration of a dietary supplement of lemon verbena extract for 90 days was associated with significant improvement in the quality of sleep as compared to placebo.

Improvements in the quality of sleep in the experimental group were noted in all sleep-related variables measured with the three study methods: the VAS score, the PSQI questionnaire, and the actigraphy device. In relation to stress-related complaints, subjects assigned to the experimental group also showed improvements in the overall score of the PSS scale of a greater magnitude as compared with placebo (non-significant differences), as well as significant amelioration of the STAI-state score. Interestingly, melatonin levels significantly increased in the subjects consuming the dietary supplement.

Plants have played a major role as human sources of medicine since ancient times and herbal plant extracts continues to be a widely accepted complementary medical option. The use of herbal medicinal products and supplements has increased tremendously over the past three decades with not less than 80% of people worldwide relying on them especially in primary healthcare [

31]. Botanical-based formulas have been integrated as effective and safe approaches for a large variety of complaints especially those that are common in the general population, such as sleep problems and feelings of stress. To this end, the World Health Organization (WHO) has developed research guidelines for the rational use and further development of herbal medicines, which should be supported by appropriate scientific studies of these products [

32].

A. citrodora (lemon verbena), a species of flowering plant of the verbena family Verbenacea, is native to South America but is cultivated in many other parts of the world including the Middle East and the Mediterranean region [

33]. Among the pleomorphic properties of the plant mostly attributed to the polyphenol verbascoside [

20], a few clinical studies have examined the sedative effects of lemon verbena for improving sleep disorders and reducing anxiety symptoms. In a randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled study, Afrasiabian et al. [

34] reported the results of the administration of 10 cc of a syrup of

A. citrodora (total essential oil content of the product 1.66 mg/10 mL and flavonoid quercetin 3.22 mg/10 mL) or placebo one hour before bedtime for 4 weeks in subjects with insomnia. All participants had a score > 5 of the PSQI questionnaire. The final analysis included 47 subjects in the intervention group and 43 in the placebo group. Main findings of this study were significant improvements in four components of the PSQI questionnaire (sleep latency, habitual sleep efficiency, daytime dysfunction, and subjective sleep quality) and also in the overall score of the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) questionnaire, which indicated better sleep quality in the

A. citriodora group. A benzodiazepine-like effect on the GABA receptor has been suggested as a plausible mechanism of action of

A. citrodora in experimental studies [

35,

36].

In our study, after 90 days of supplementation, we found significant differences in the overall score of the PSQI and in the subscales of sleep latency and sleep efficiency, with improvements already observed at data analysis of the mid-study visit, with better sleep quality in subjects treated with lemon verbena. The beneficial effects of the supplementation with lemon verbena on sleep parameters were also found in sleep analysis by actigraphy. In this case, not only sleep latency and sleep efficiency improved significantly in the experimental group, but also results obtained in wakefulness after sleep onset and duration of awakenings were significantly more favorable as compared with the placebo group. These additional benefits could be due to the specific characteristics of the lemon verbena extract used, which is standardized in containing at least 24% verbascoside.

The tranquilizing effect of lemon verbena have been also reported by others. In a randomized single-blind aromatherapy study in women undergoing a cesarean section, the administration of three inhaled drops of lemon verbena essential oil before surgery as compared to distilled water reduced preoperative anxiety [

37]. Martínez-Rodríguez et al. [

27] conducted a randomized double-blind controlled study to assess the effect of dietary supplementation with

Lippia citriodora vs. placebo in subjects with sleep problems and anxiety symptoms treated over an 8-week study period. The results of this study are similar to our findings, with reduction of perceived stress and improved sleep quality, with a stronger effect on sleep quality in women. A previous study of these authors in two groups of 14 volunteers each consuming an extract of lemon verbena or placebo during 21 days, results of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) showed reduced values in the subscales of tension-anxiety, anger-hostility and fatigue-inertia at the end of the study compared to placebo [

38].

Consumption of the lemon verbena extract over 90 days was associated not only with better sleep quality, but also with a significant increase in nocturnal melatonin levels. These findings are consistent with restoration of nocturnal melatonin secretion in patients with sleep disorders treated with sleep medications [

39,

40]. As far as we are aware, this is the first study to demonstrate, at least clinically, that lemon verbena can increase the production/secretion of melatonin at night. There are very few herb extracts that are known to be able to increase melatonin production. As melatonin use is increasing among the population, including children, and the long-term effects of its use is relatively unknown, the use of other, more natural alternatives to increase endogenous melatonin production is of great interest.

Analysis of plasma cortisol levels was unrevealing in our study, without differences between baseline and 90-day values in any of the study groups. In the study of Martínez-Rodríguez et al. [

27], cortisol levels showed a 15.6% decrease after 2 months of supplementation with lemon verbena extract, which coincided with decreased perceived stress reported in this study. Lower baseline values of plasma cortisol levels in the present study may account for the differences as compared with the study of Martínez-Rodríguez et al. [

27].

All changes in the study variables were unrelated to the effect of anthropometric variables or physical activity levels since changes in these parameters between baseline and the end of the study did not occur. Moreover, all participants showed a good adherence to the study products. The investigational supplement of lemon verbena was well tolerated and safe.

The present results should be interpreted taking into account some limitations of the study, particularly the reduced sample size and the duration of dietary supplementation of 90 days. Although it was emphasized to maintain dietary habits over the course of the study, strict control of dietary intake was not performed.

5. Conclusions

The administration of a dietary supplement comprised of Aloysia citrodora (lemon verbena) extract for 90 days in healthy volunteers with sleep problems resulted in a significant improvement of sleep quality as compared with placebo. Improvements were also apparent at the mid-study visit after 45 days of supplementation. Melatonin levels also significantly increased in the experimental group. However, further randomized controlled studies with a larger study population and a more prolonged duration of supplementation are necessary to confirm these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.L.-R.; methodology, F.J.L.-R. and S.P.-P.; software, S.P.-P. and J.C.M.-C.; validation, S.P.-P. and J.C.M.-C.; formal analysis, F.J.L.-R.; investigation, S.P.-P., J.C.M.-C., J.E.-T., M.M.-C., C.H.-F., A.I.G.-G. and V.Á.-G.; data curation, F.J.L.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.L.-R, S.P.-P., J.C.M.-C., J.E.-T., M.M.-C. and C.H.-F.; writing—review and editing, F.J.L.-R, S.P.-P., J.C.M.-C., J.E.-T., M.M.-C., C.H.-F., A.I.G.-G., V.Á.-G., J.J, N.C., P.N.,; visualization, J.J., N.C., P.N.,; supervision, S.P.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Monteloeder, S.L., Elche, Alicante, Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia (code CE032302, approval date 30 March 2023), Murcia, Spain.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marta Pulido, MD, PhD, for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance. The authors decline the use of artificial intelligence, language models, machine learning or similar technologies to create content or assist with writing or editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors, S.P.-P., J.C.M.-C., J.E.-T., M.M.-C., C.H.-F., A.I.G.-G., V.Á.-G. and F.J.L.-R. declare no conflict of interest. J.J, N.C., and P.N. declare competing interests as employees of Monteloeder S.L.

References

- Panossian LA, Avidan AY. Review of sleep disorders. Med Clin North Am. 2009, 93, 407–425. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou Y, Jin Y, Zhu Y, Fang W, Dai X, Lim C, Mishra SR, Song P, Xu X. Sleep problems associate with multimorbidity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Rev. 2023, 44, 1605469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleton SL, Gill TK, Lang CJ, Taylor AW, McEvoy RD, Stocks NP, González-Chica DA, Adams RJ. Prevalence and comorbidity of sleep conditions in Australian adults: 2016 Sleep Health Foundation national survey. Sleep Health. 2018, 4, 13–19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San L, Arranz B. The night and day challenge of sleep disorders and insomnia: A narrative review. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2024, 52, 46–56.

- Reimer MA, Flemons WW. Quality of life in sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2003, 7, 335–349. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikeos D, Georgantopoulos G. Medical comorbidity of sleep disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011, 24, 346–354. [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar S, Hemavathy D, Prasad S. Prevalence of chronic insomnia in adult patients and its correlation with medical comorbidities. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016, 5, 780–784. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting L, Malhotra A. Disorders of sleep: An overview. Prim Care. 2005, 32, 305–318. [CrossRef]

- Kallestad H, Hansen B, Langsrud K, Ruud T, Morken G, Stiles TC, Gråwe RW. Impact of sleep disturbance on patients in treatment for mental disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2012, 12, 179. [CrossRef]

- Basta M, Chrousos GP, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN. Chronic insomnia and stress system. Sleep Med Clin. 2007, 2, 279–291. [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.M. Insomnia: An integrative approach to stress-induced insomnia. Holist Nurs Pract. 2011, 25, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhog M S, Medikonda J. A clinical and technical methodological review on stress detection and sleep quality prediction in an academic environment. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 235, 107521. [CrossRef]

- Jarrin DC, Chen IY, Ivers H, Morin CM. The role of vulnerability in stress-related insomnia, social support and coping styles on incidence and persistence of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2014, 23, 681–688. [CrossRef]

- Maczaj, M. Pharmacological treatment of insomnia. Drugs. 1993, 45, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson E, Hainer BL. Insomnia: Pharmacologic therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2017, 96, 29–35.

- Saeed SA, Bloch RM, Antonacci DJ. Herbal and dietary supplements for treatment of anxiety disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007, 76, 549–556.

- Barić H, Đorđević V, Cerovečki I, Trkulja V. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for generalized anxiety disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Ther. 2018, 35, 261–288. [CrossRef]

- Zhao FY, Xu P, Kennedy GA, Conduit R, Zhang WJ, Wang YM, Fu QQ, Zheng Z. Identifying complementary and alternative medicine recommendations for insomnia treatment and care: A systematic review and critical assessment of comprehensive clinical practice guidelines. Front Public Health. 2023, 11, 1157419. [CrossRef]

- Ell J, Schmid SR, Benz F, Spille L. Complementary and alternative treatments for insomnia disorder: A systematic umbrella review. J Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13979. [CrossRef]

- Bahramsoltani R, Rostamiasrabadi P, Shahpiri Z, Marques AM, Rahimi R, Farzaei MH. Aloysia citrodora Paláu (Lemon verbena): A review of phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 222, 34–51. [CrossRef]

- Abuhamdah S, Abuhamdah R, Howes MJ, Al-Olimat S, Ennaceur A, Chazot PL. Pharmacological and neuroprotective profile of an essential oil derived from leaves of Aloysia citrodora Palau. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1306–1315. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadhosseini M, Frezza C, Venditti A, Mahdavi B. An overview of the genus Aloysia Paláu (Verbenaceae): Essential oil composition, ethnobotany and biological activities. Nat Prod Res. 2022, 36, 5091–5107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabti M, Sasaki K, Gadhi C, Isoda H. Elucidation of the molecular mechanism underlying Lippia citriodora(Lim.)-induced relaxation and anti-depression. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3556. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelucci MA, Martinez EZ, Pereira AMS. Aloysia polystachya (Griseb.) Moldenke (Verbenaceae) powdered leaves are effective in treating anxiety symptoms: A phase-2, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 242, 112060. [CrossRef]

- Ragone M, Sella M, Pastore A, Consolini A. Sedative and cardiovascular effects of Aloysia citriodora Palau, on mice and rats. Lat Am J Pharm. 2010, 29, 79–86.

- Costa de Melo N, Sánchez-Ortiz BL, Dos Santos Sampaio TI, Matias Pereira AC, Pinheiro da Silva Neto FL, Ribeiro da Silva H, Alves Soares Cruz R, Keita H, Soares Pereira AM, Tavares Carvalho JC. Anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of the hydroethanolic extract from the leaves of Aloysia polystachya (Griseb.) Moldenke: A study on Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2019, 12, 106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez A, Martínez-Olcina M, Mora J, Navarro P, Caturla N, Jones J. Anxiolytic effect and improved sleep quality in individuals taking Lippia citriodora extract. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 218. [CrossRef]

- Hita-Contreras, F.; Martínez-López, E.; Latorre-Román, P.A.; Garrido, F.; Santos, M.A.; Martínez-Amat, A. Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) in patients with fibromyalgia. Rheumatol. Int. 2014, 34, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buela-Casal G, Guillén-Riquelme A. Short form of the Spanish adaptation of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Int J Clin Health Psycho 2017, 17, 261–268. [CrossRef]

- Remor E, Carrobles JA. Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14): Psychometric study in a HIV+ sample. Ansiedad y Estrés 2001, 7, 195–201.

- Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front Pharmacol. 2014, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Research guidelines for evaluating the safety and efficacy of herbal medicines. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9290611103 (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Pascual ME, Slowing K, Carretero E, Sánchez Mata D, Villar, A. Lippia: Traditional uses, chemistry and pharmacology: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 76, 201–214. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrasiabian F, Mirabzadeh Ardakani M, Rahmani K, Azadi NA, Alemohammad ZB, Bidaki R, Karimi M, Emtiazy M, Hashempur MH. Aloysia citriodora Palau (lemon verbena) for insomnia patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Phytother Res. 2019, 33, 350–359.

- Ragone MI, Sella M, Pastore A, Consolini AE. Sedative and cardiovascular effects of Aloysia citriodora Palau, on mice and rats. Lat Am J Pharm. 2010, 29, 79–86.

- Razavi BM, Zargarani N, Hosseinzadeh H. Anti-anxiety and hypnotic effects of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Lippia citriodora leaves and verbascoside in mice. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2017, 7, 353–365.

- Haryalchi K, Kazemi Aski S, Mansour Ghanaie M, Fotouhi M, Mansoori R, Sadraei SM, Yaghobi Y, Olangian-Tehrani S. Effects of the aroma of lemone verbena (Aloysia citriodora Paláu) essential oil on anxiety and the hemodynamic profile before cesarean section: A randomized clinical trial. Health Sci Rep. 2023, 6, e1282. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez A, Moya Mm Vicente-Salar N, Brouzet T, Carrera-Quintanar L, Cervelló E, Micol V, Roche E. Changes in biochemical and psychological parameters in university students performing aerobic exercise and consuming lemon verbena extracts. Curr Top Nutraceutical Res. 2015, 13, 95–102.

- Hajak G, Rodenbeck A, Adler L, Huether G, Bandelow B, Herrendorf G, Staedt J, Rüther E. Nocturnal melatonin secretion and sleep after doxepin administration in chronic primary insomnia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1996, 29, 187–192. [CrossRef]

- Rodenbeck A, Huether G, Rüther E, Hajak G. Nocturnal melatonin secretion and its modification by treatment in patients with sleep disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999, 467, 89–93.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).