Submitted:

16 April 2024

Posted:

17 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

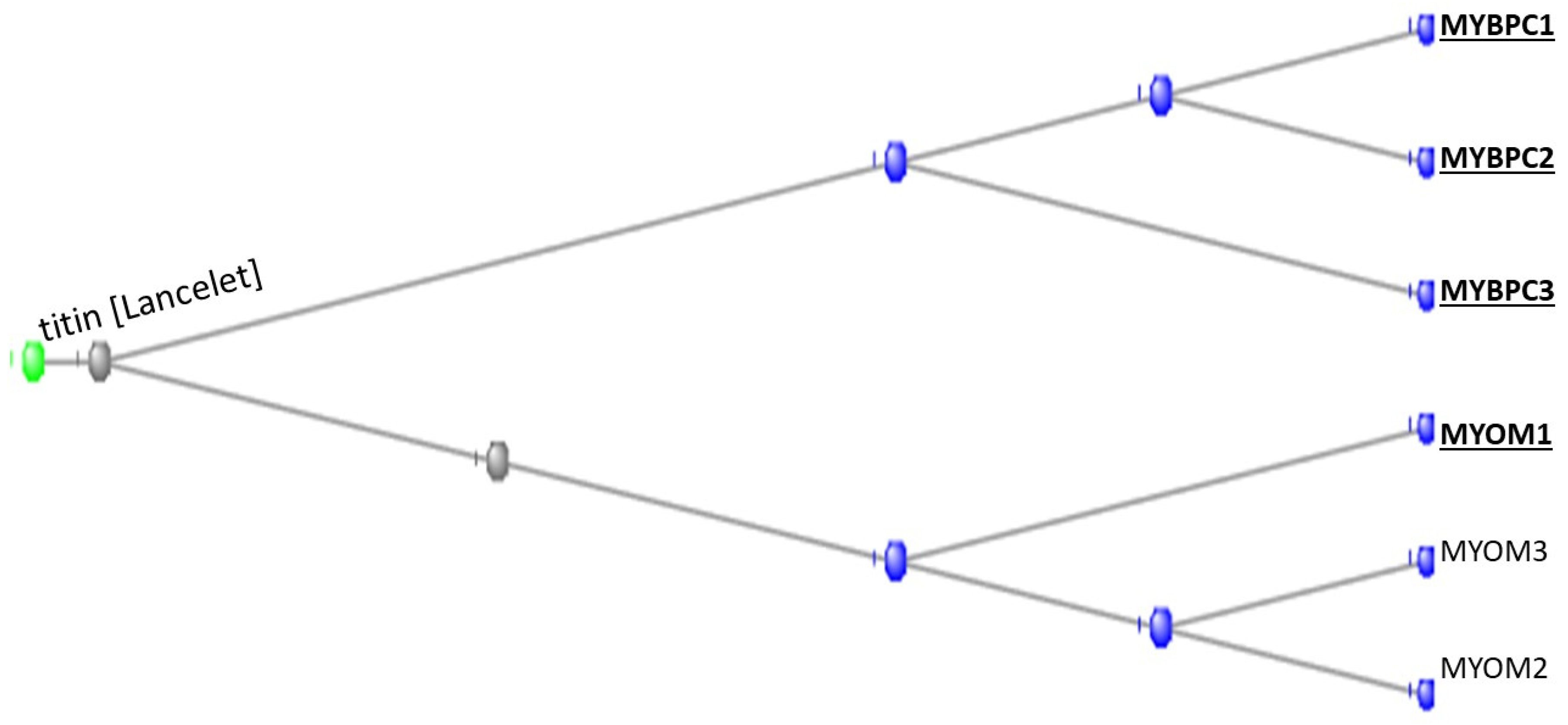

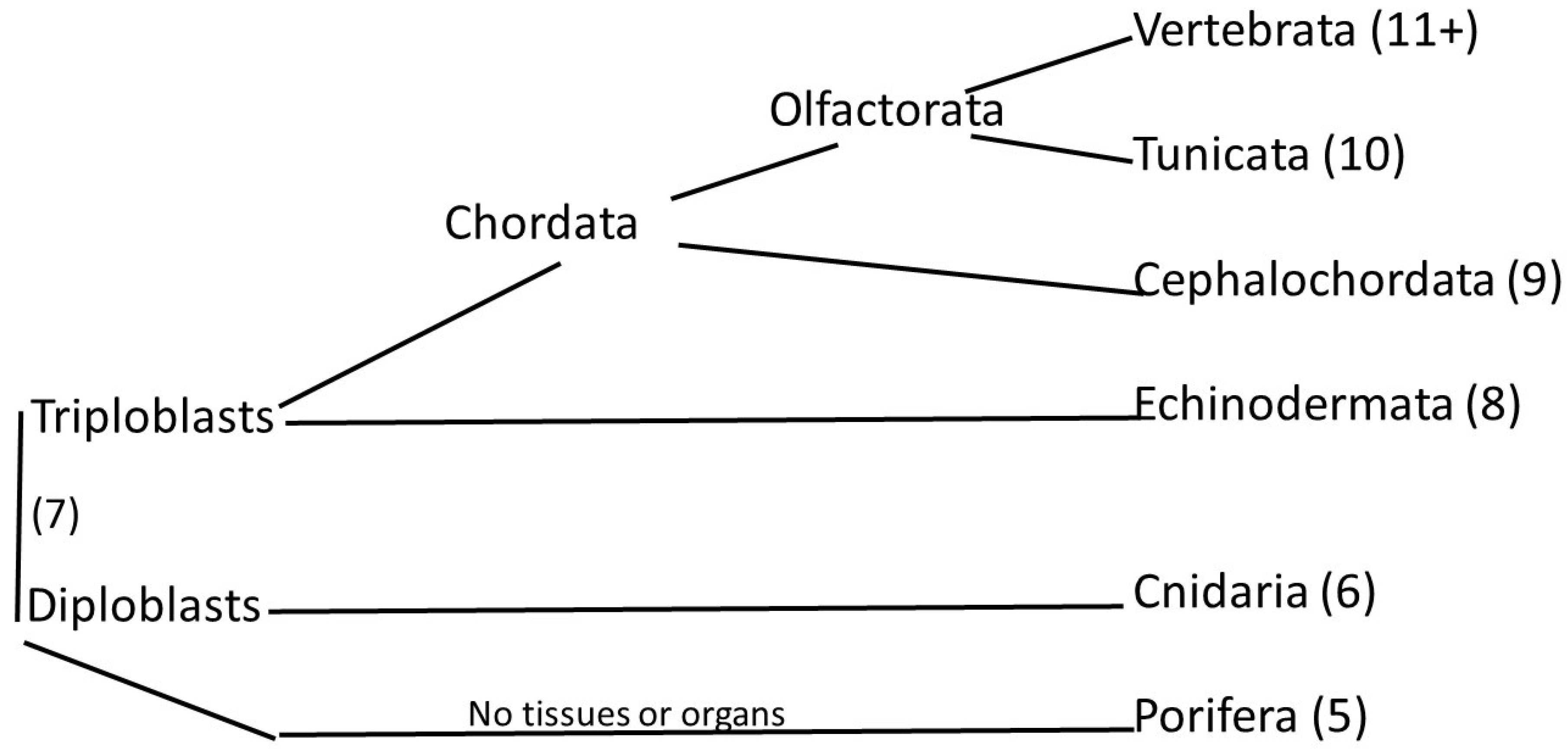

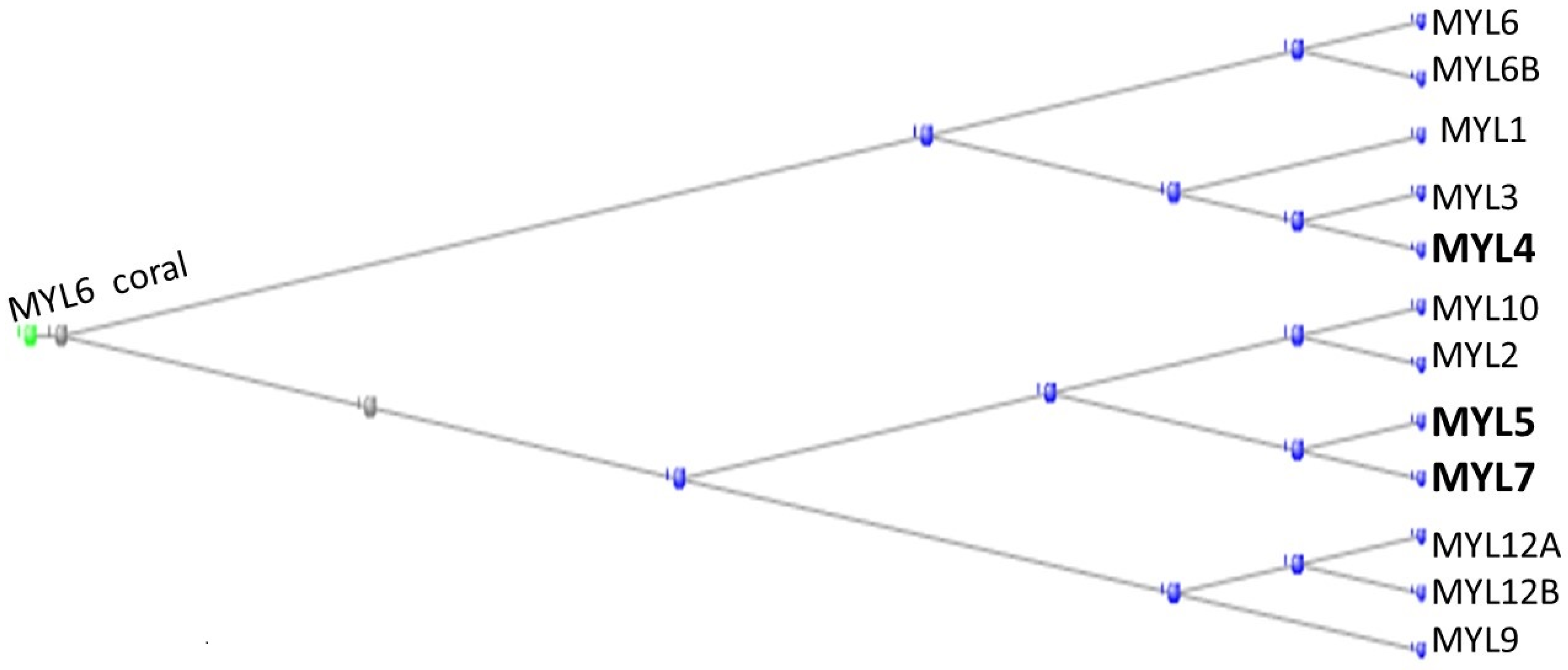

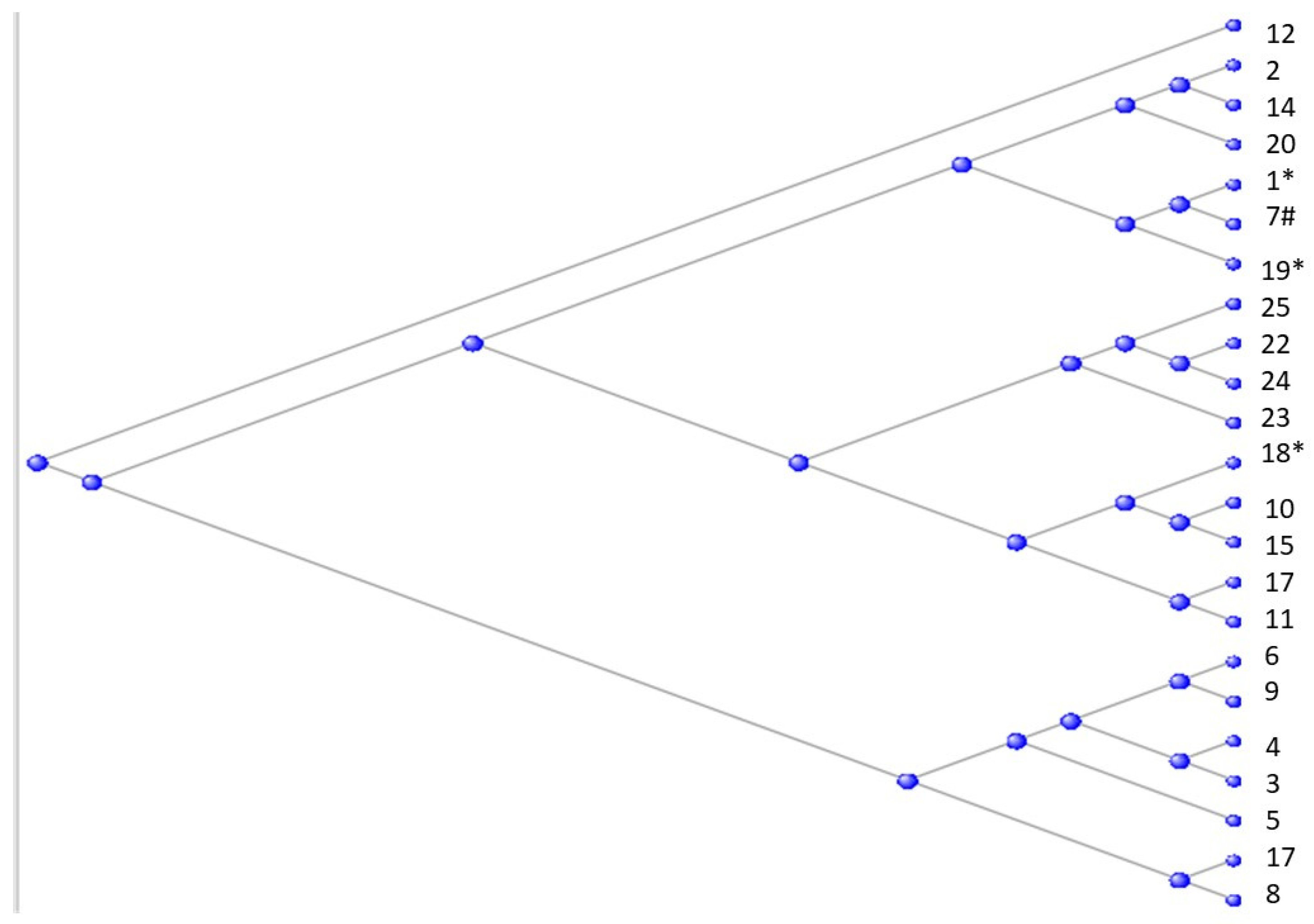

3.1. The Muscle Protein Genes

The Proteins of Muscle

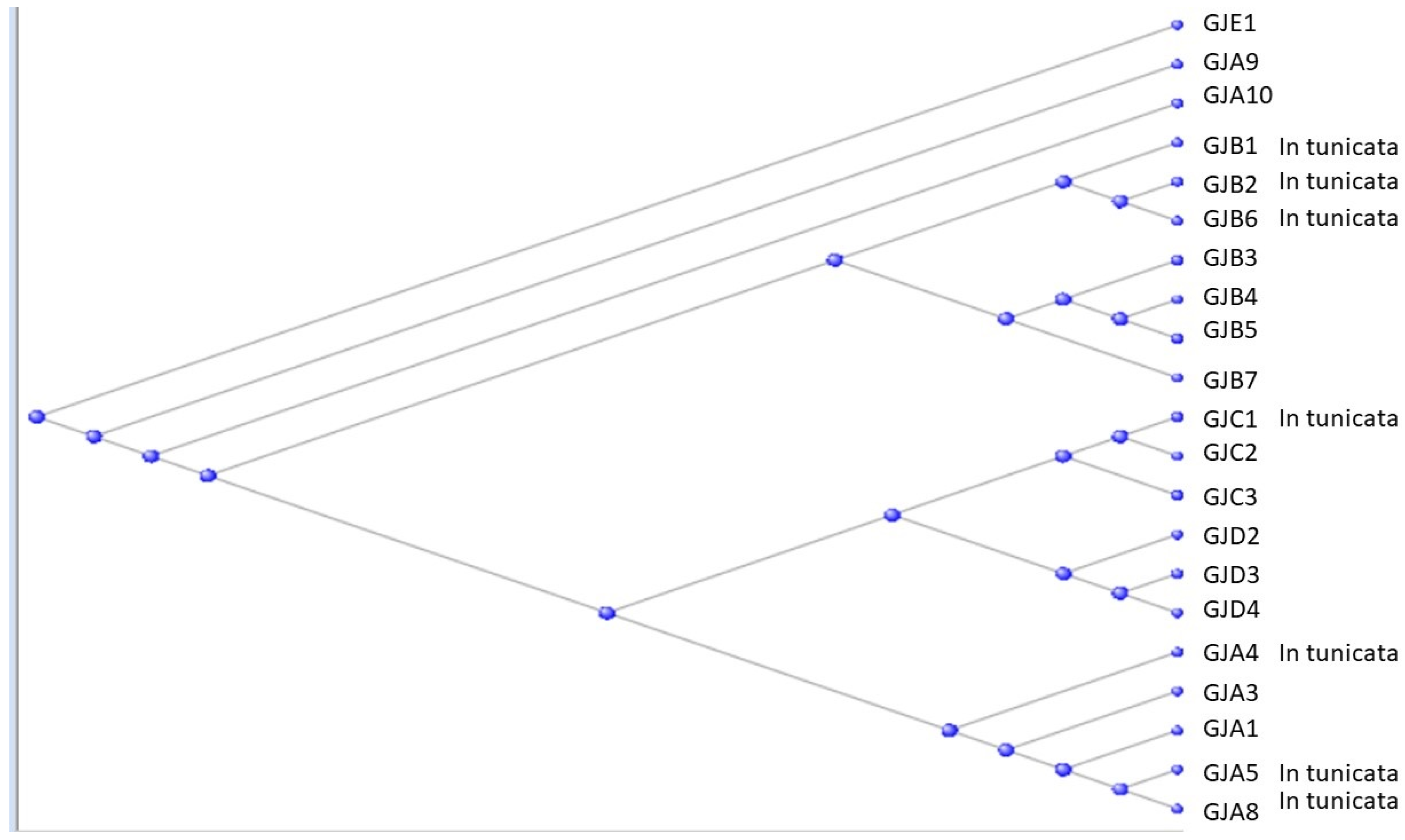

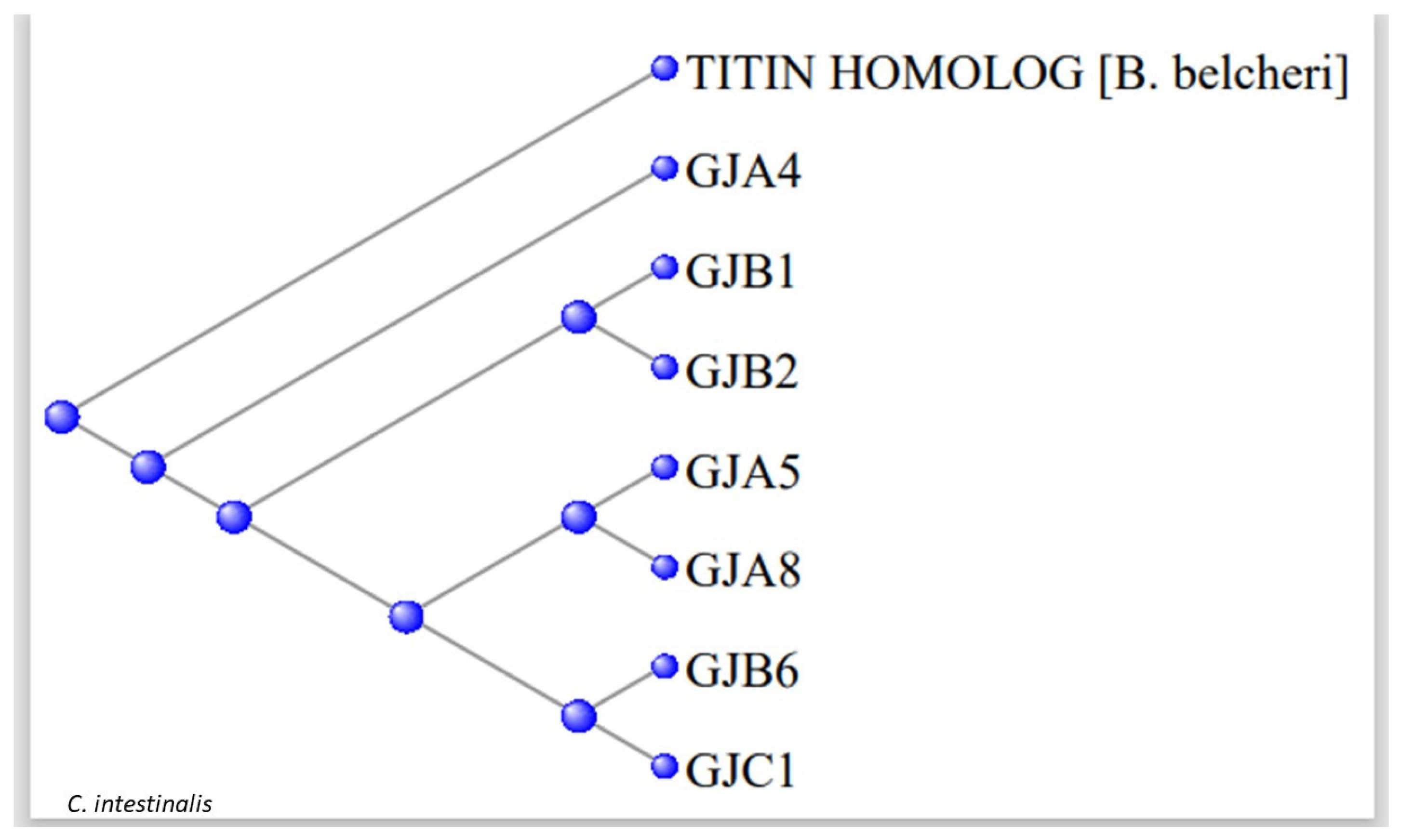

3.2. The Gap Junction Proteins

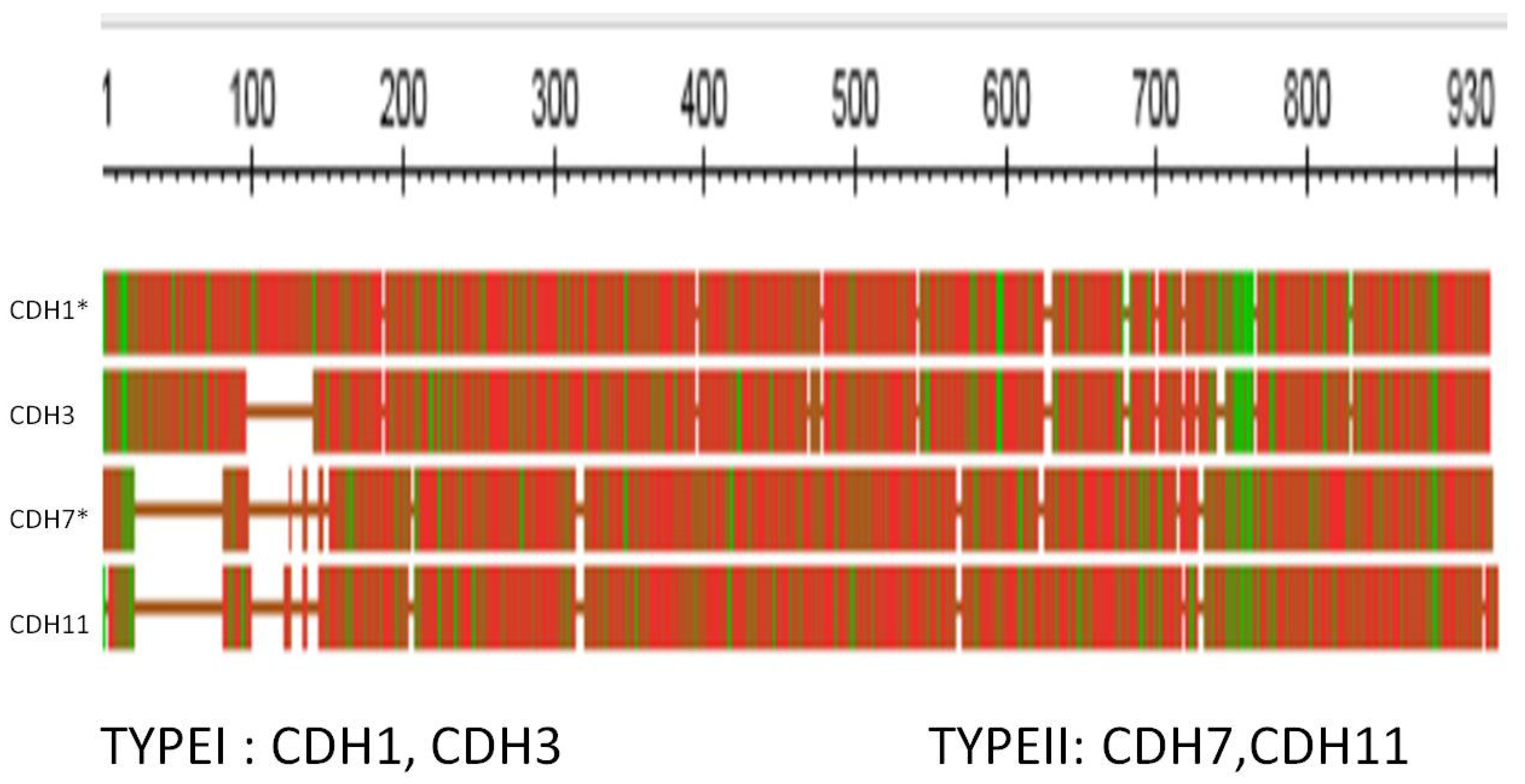

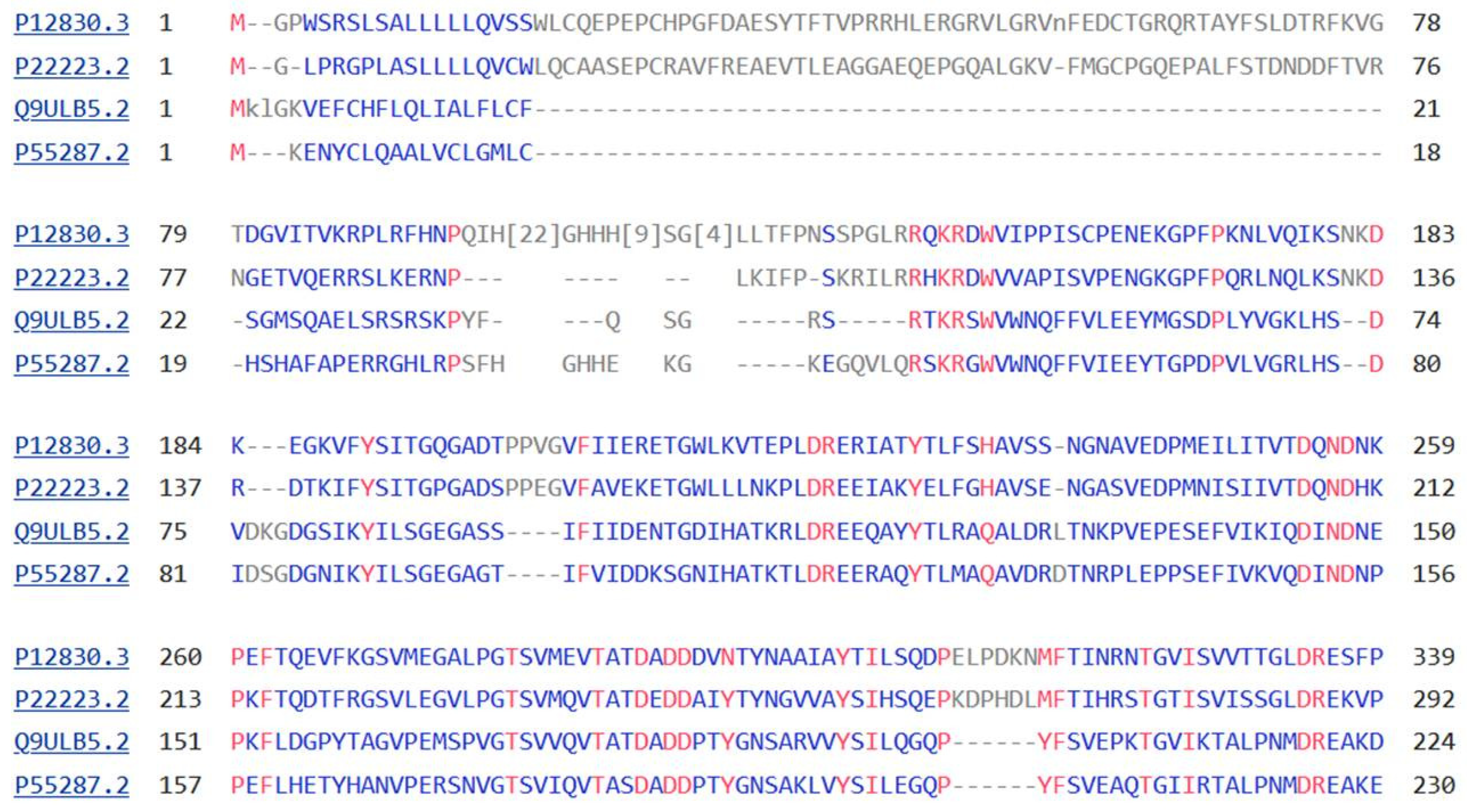

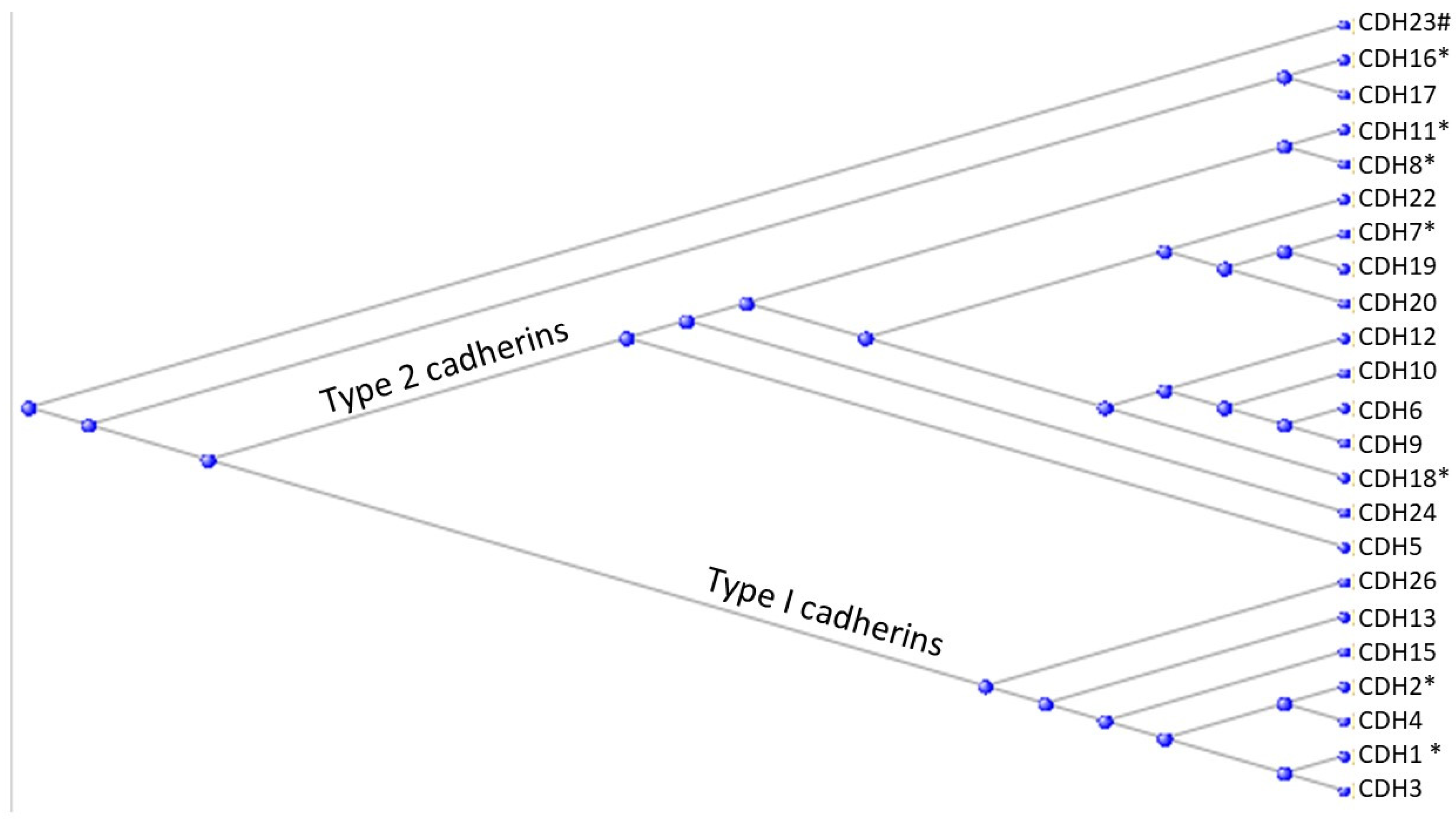

3.3. The Cadherins

| Familiar name | Tissue distribution | HGNC | Type | Has Tunicate ortholog ? |

| Cadherin E | Epithelial | CDH1 | I | Yes |

| Cadherin N | Neural | CDH2 | I | Yes |

| Cadherin P | Placental | CDH3 | I | |

| Cadherin R | Retinal | CDH4 | I | |

| Cadherin VE | Epithelial | CDH5 | II | |

| Cadherin K | Brain; kidney | CDH6 | II | |

| Cadherin OB | Osteoblast | CDH11 | II | Yes |

| Cadherin BR | Brain | CDH12 | II | |

| Cadherin T and H | Heart | CDH13 | I | |

| Cadherin M | Muscle | CDH15 | I |

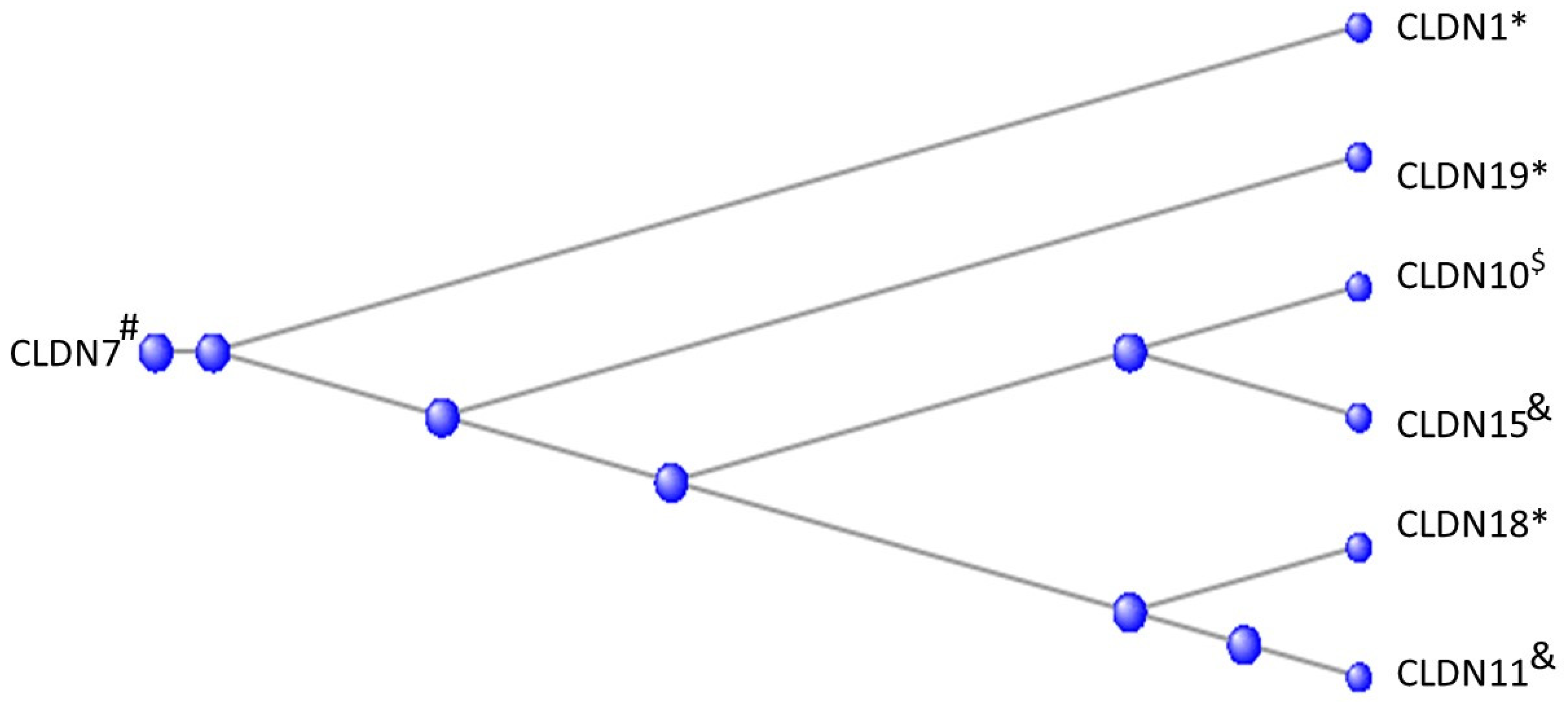

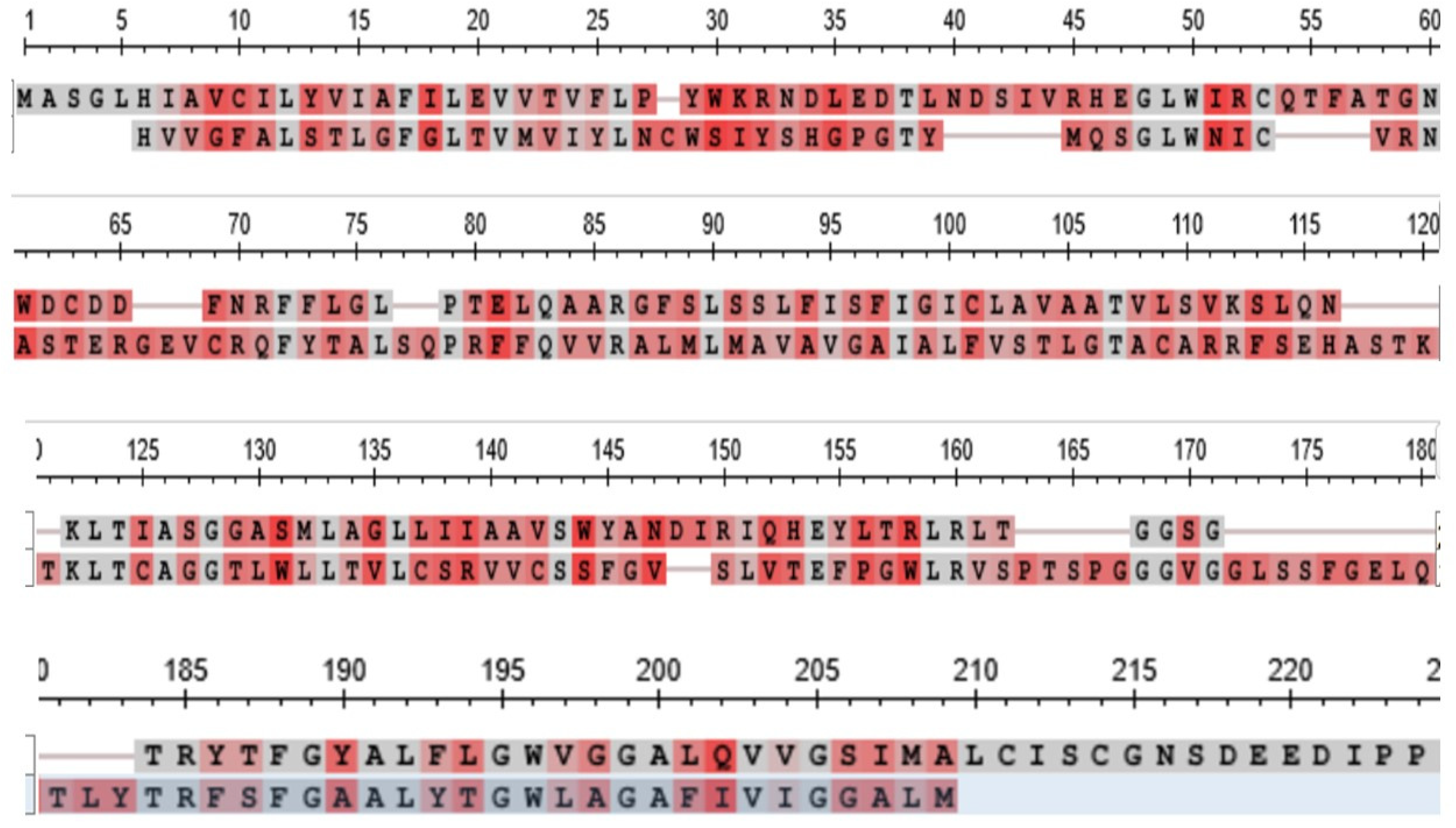

3.4. The Claudins

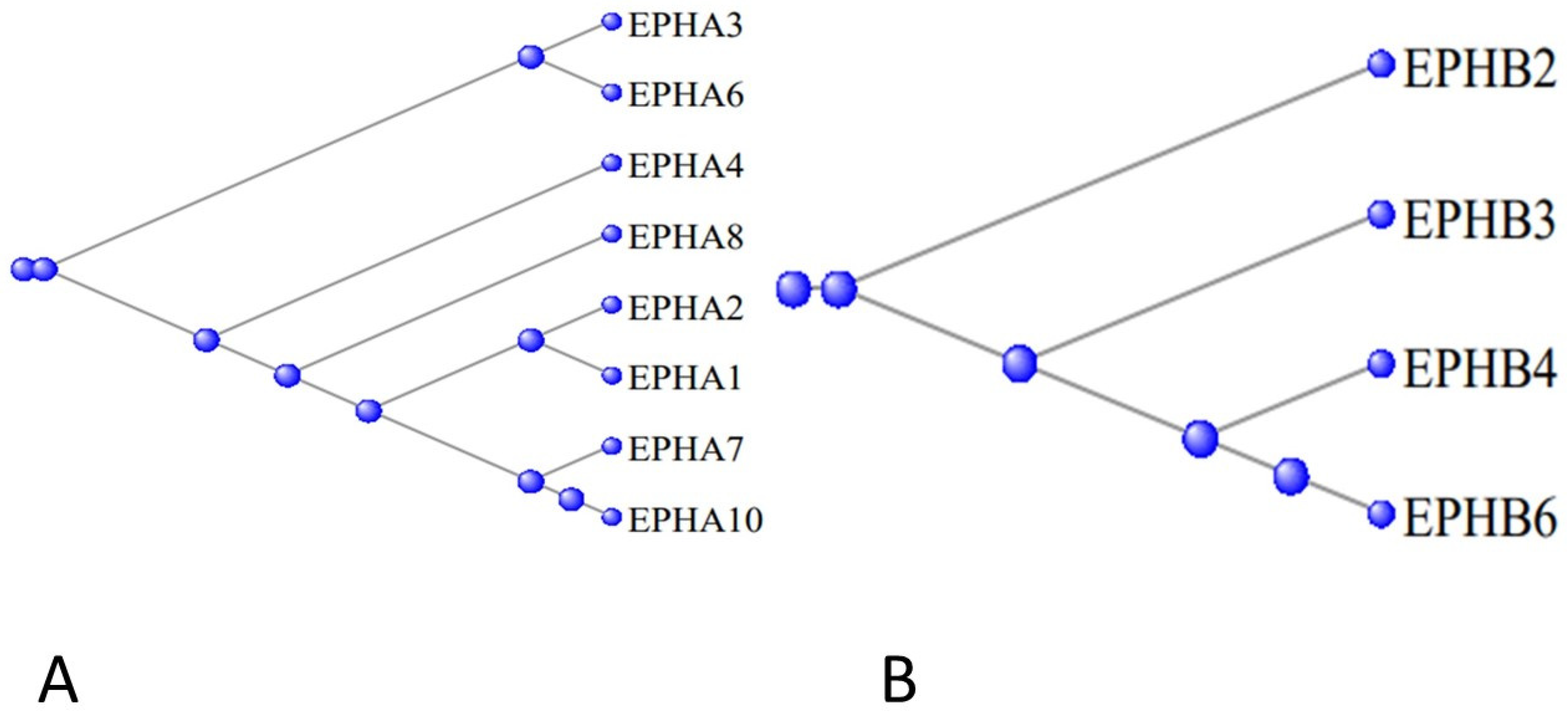

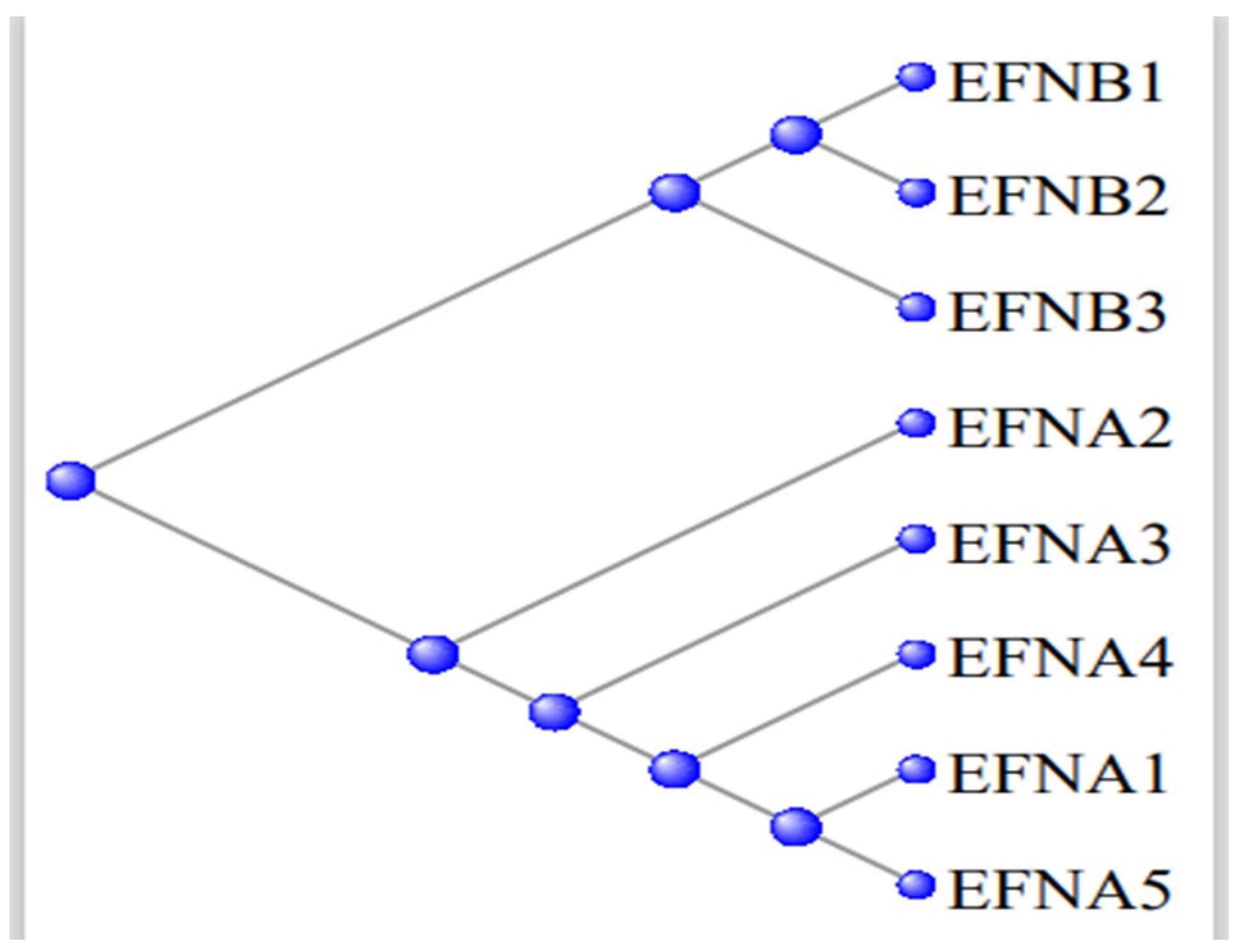

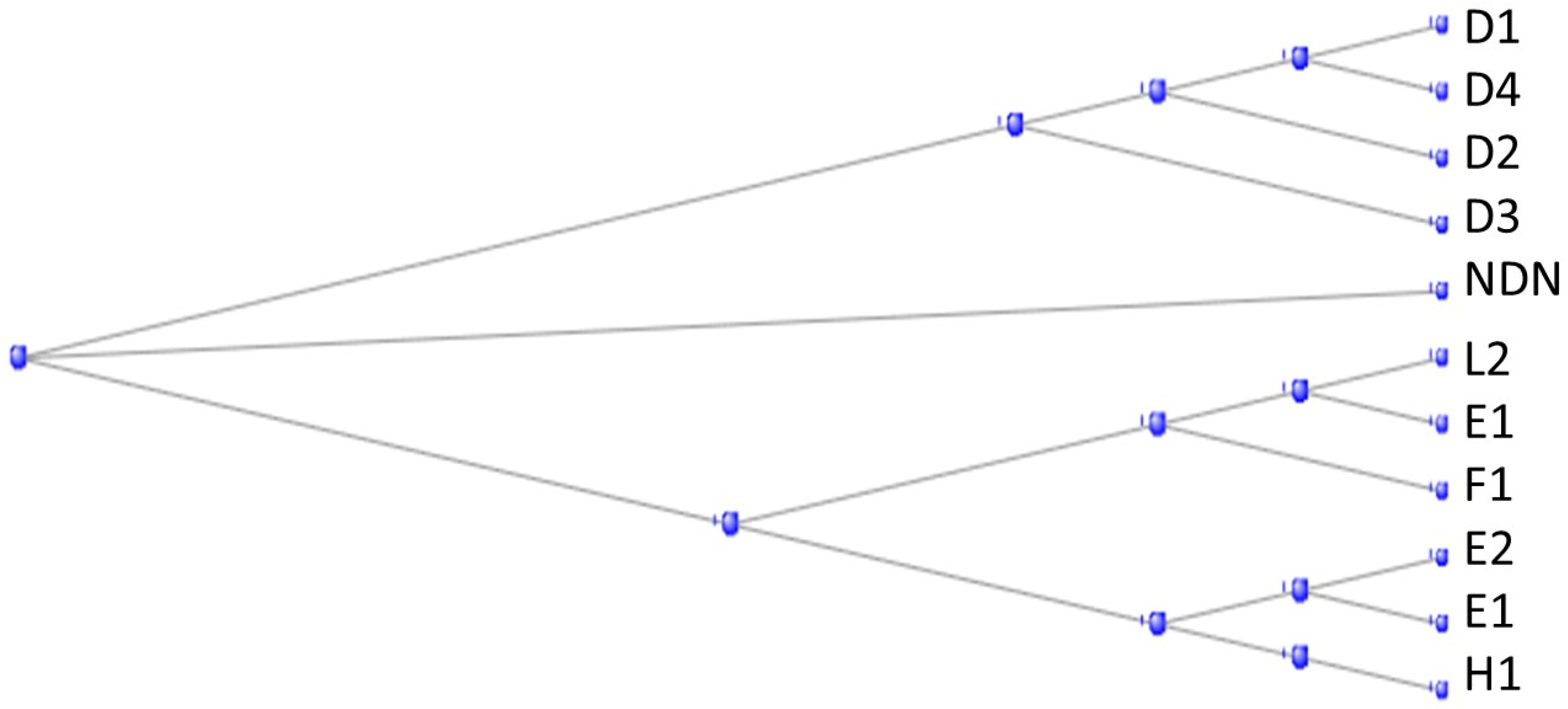

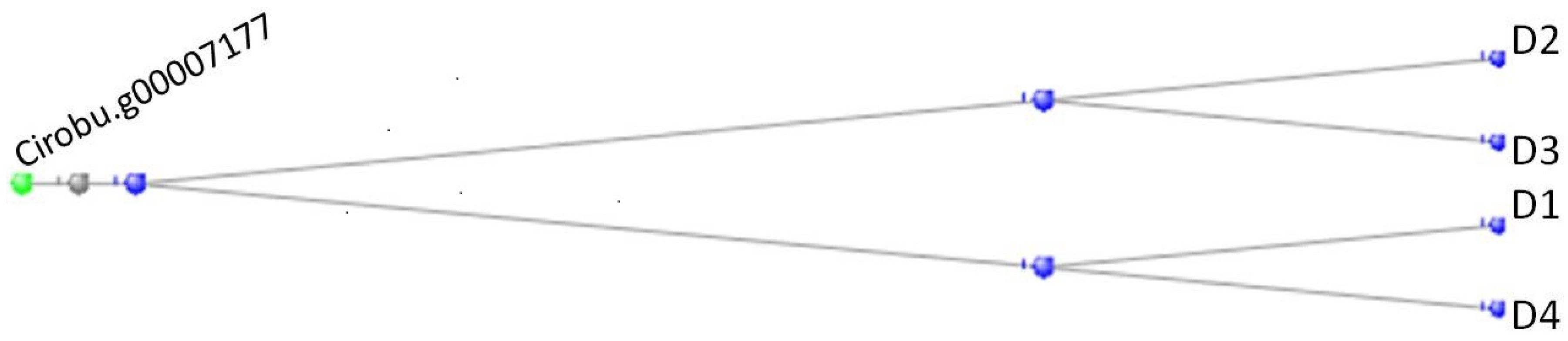

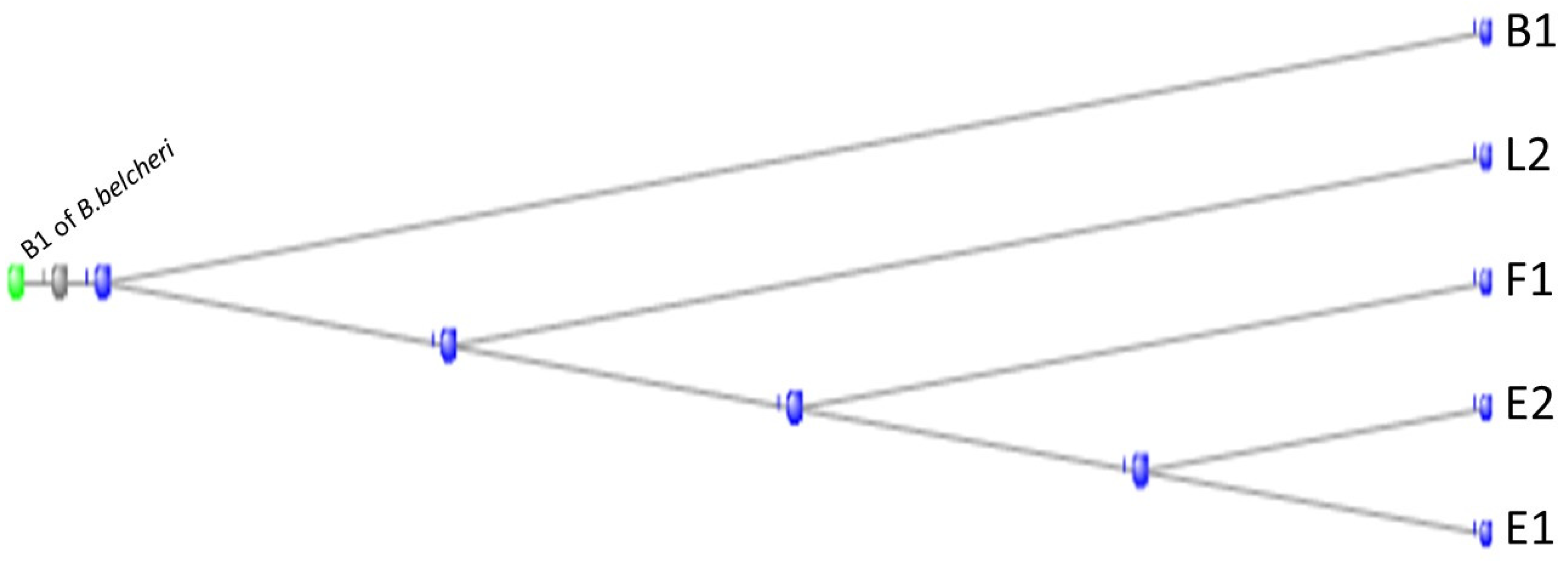

3.5. The Ephrons and Ephrins

3.6. The MAGE Genes

3.7. The Crystallins

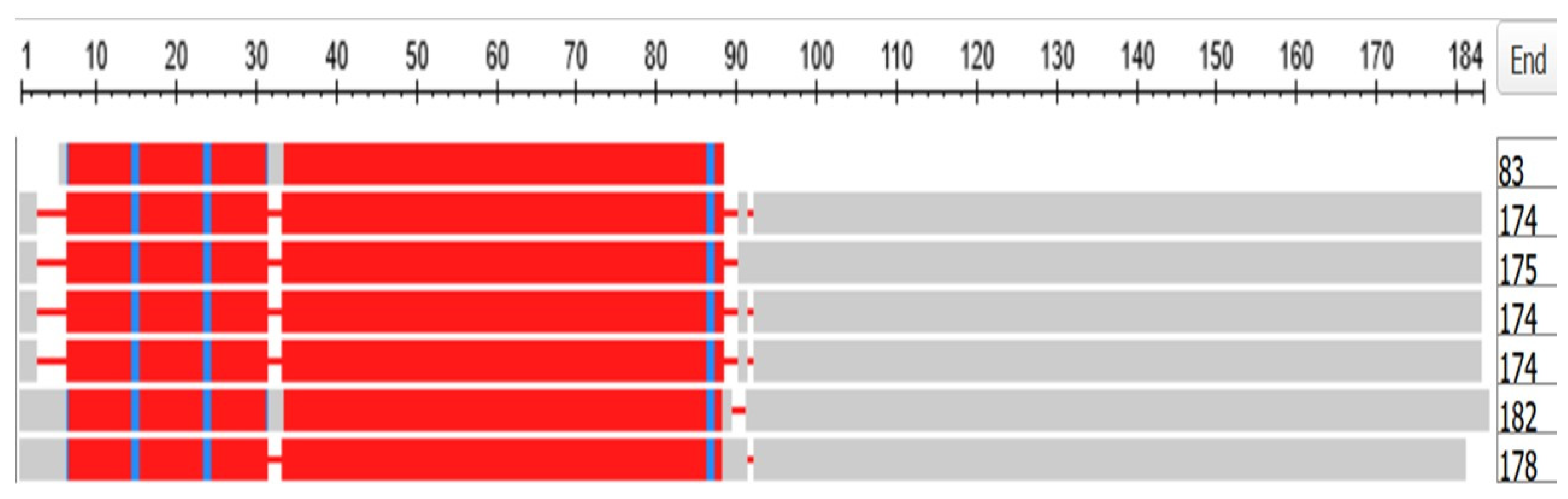

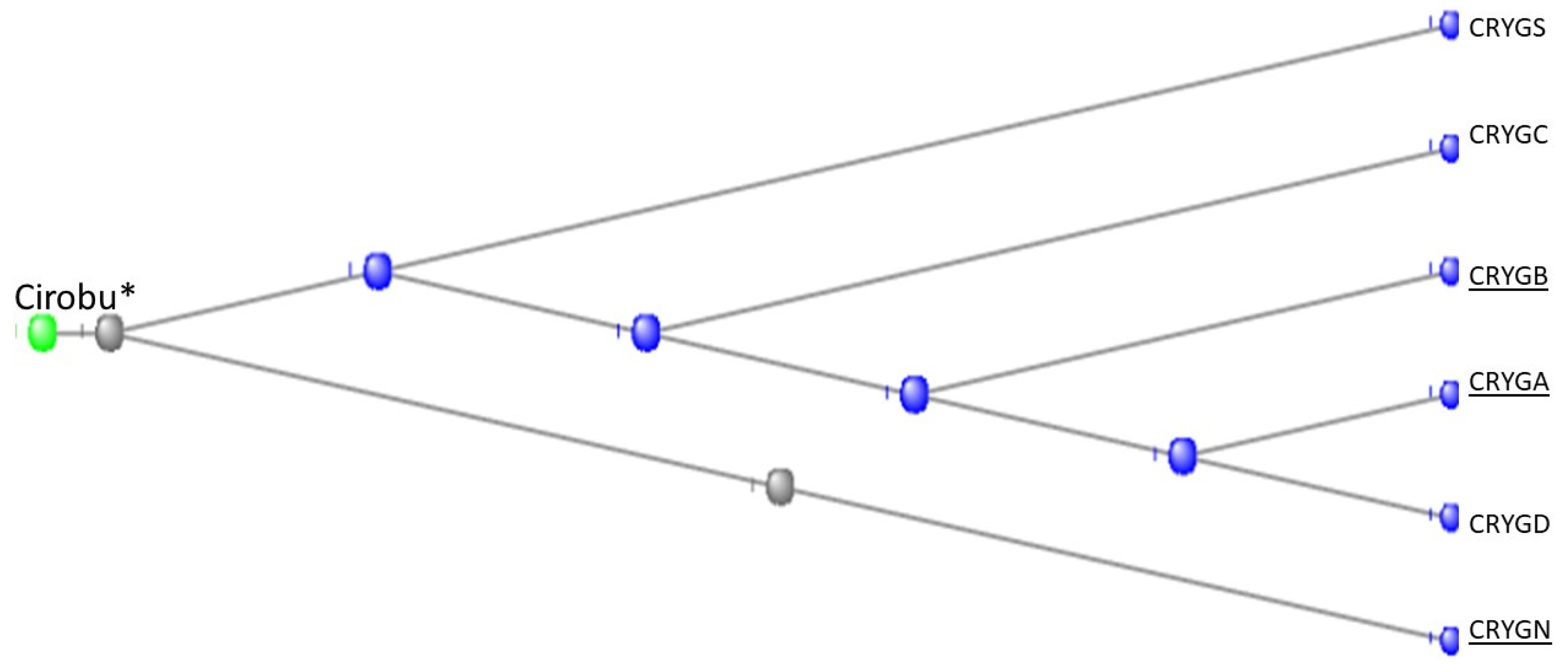

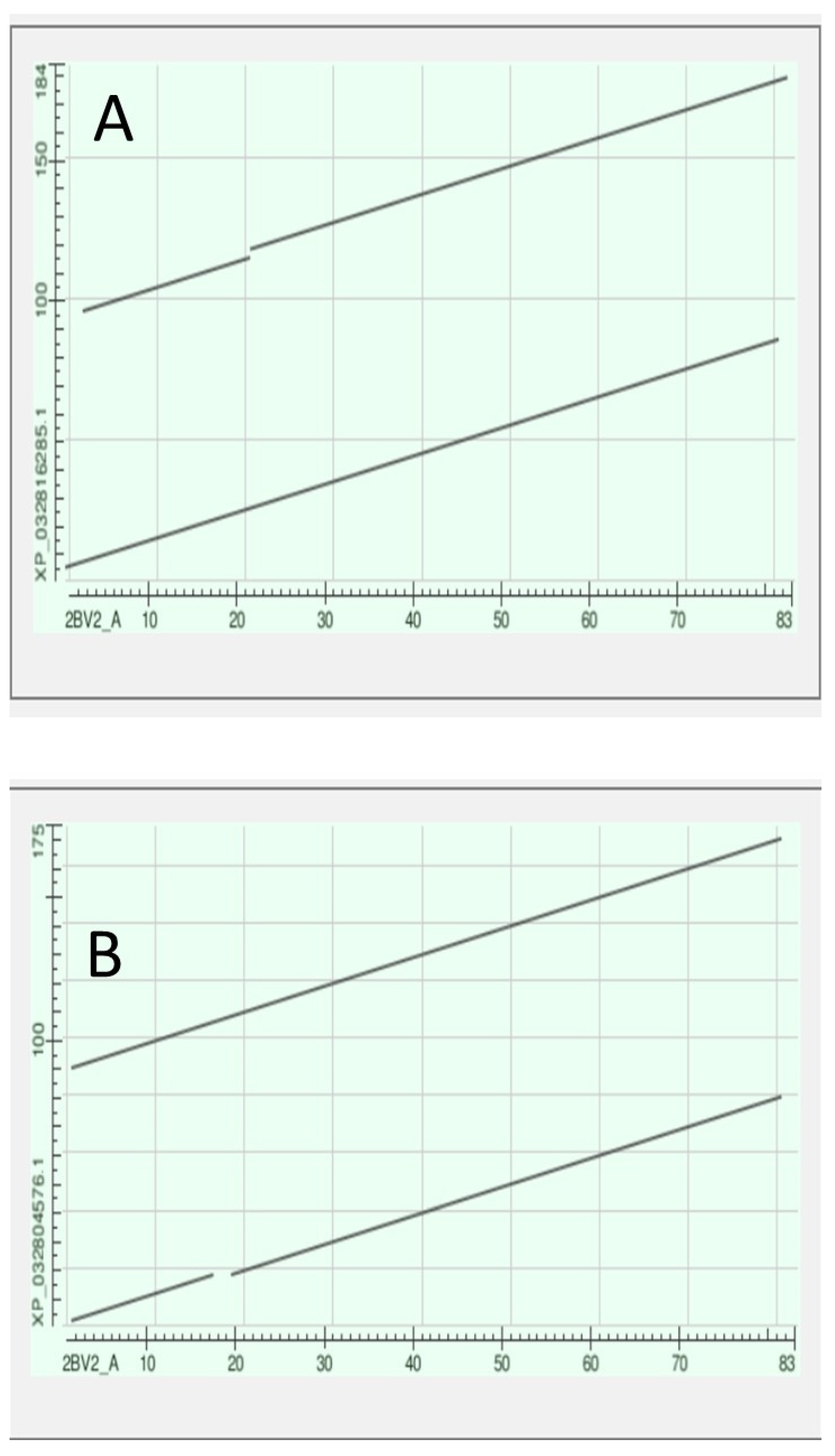

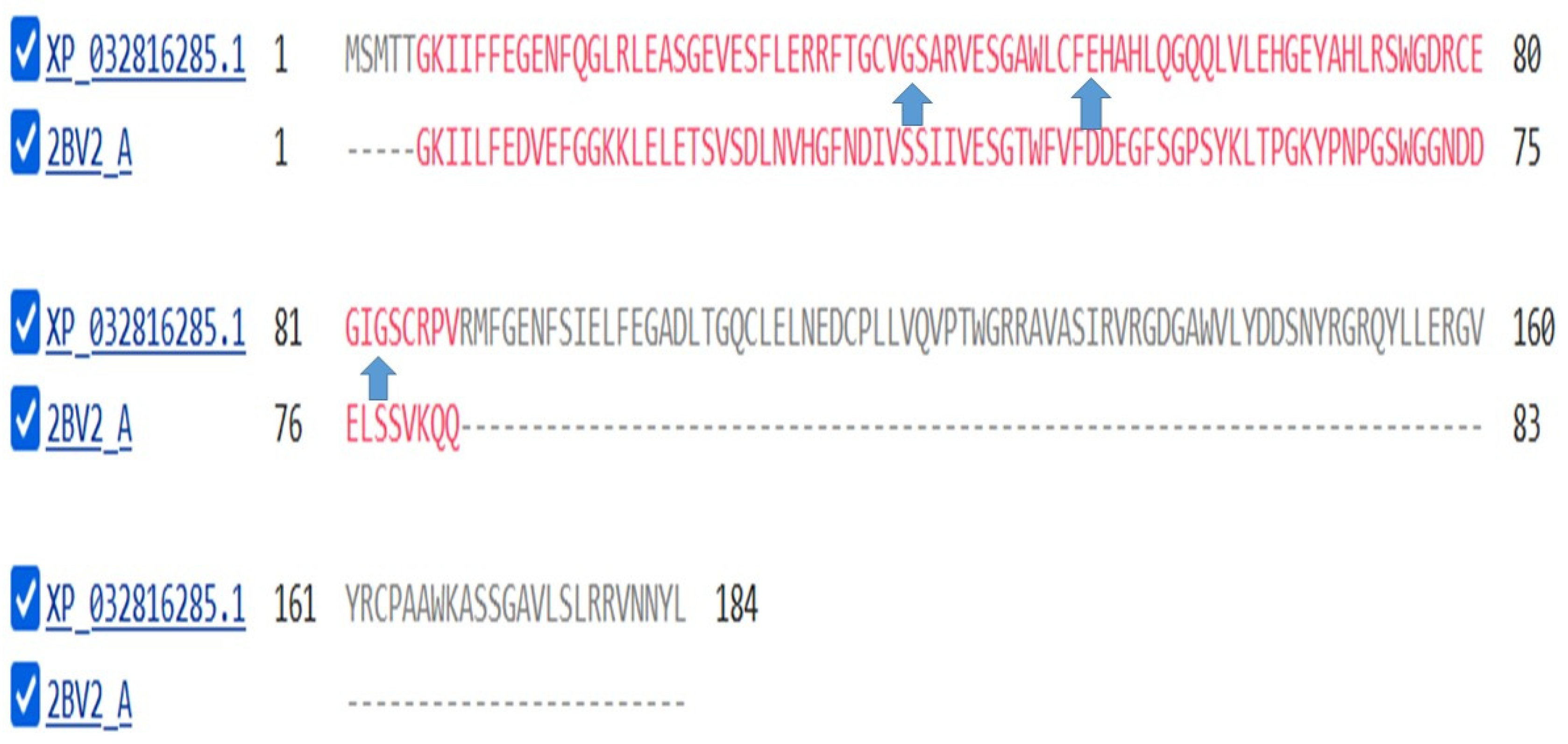

The Gamma Crystallins

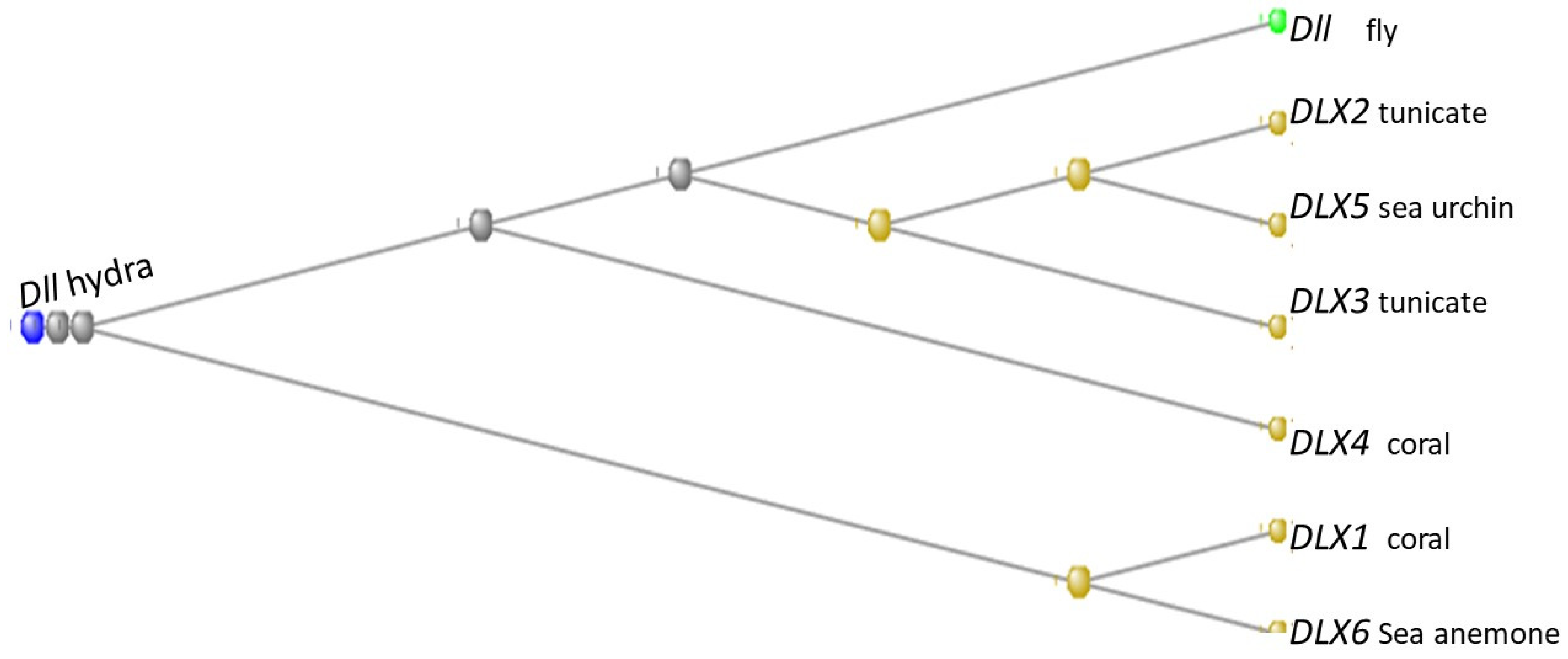

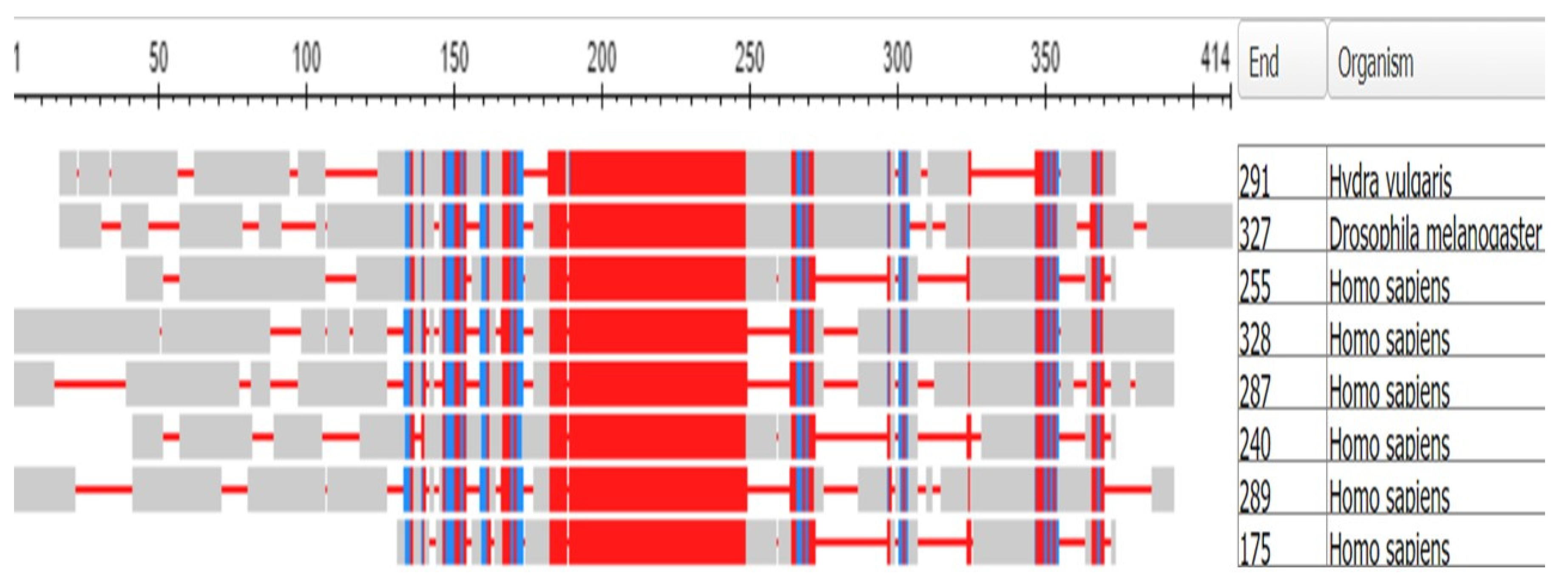

3.8. The Distal-Less Genes

3.9. DAVID Analysis of Individual Orthologs Not Discussed in Previous Subsections

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contribution

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Domazet-Lošo, T.; Tautz, D. Phylostratigraphic tracking of cancer genes suggests a link to the emergence of multicellularity in metazoa. BMC Biol 2010, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delsuc, F.; Brinkmann, H.; Chourrout, D.; Philippe, H. Tunicates and not cephalo-chordates are the closest living relatives of vertebrates. Nature 2006, 439, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebeskind, B.J.; McWhite, D.; Marcotte, E.M. Towards consensus gene ages. Genome Biol Evol 2016, 8, 1812–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litman, T.; Stein, W.D. Obtaining estimates for the ages of all the protein-coding genes and most of the ontology-identified noncoding genes of the human genome, assigned to 19 phylostrata. Sem Oncology 2019, 46, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colgren, J.; Nichols, S.A. MRTF specifies a muscle-like contractile module in Porifera. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zullo, L.; Bozzo, M.; Daya, A.; Di Clemente, A.; Mancini, F.P.; Megighian, A.; Nesher, N.; Röttinger, E.; Shomrat, T.; Tiozzo, S.; Zullo, A.; Candiani, S. The diversity of muscles and their regenerative potential across animals. Cells 2020, 9, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnel, S.M.; Walz, M.; Technau, U. Development and epithelial organisation of muscle cells in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Front Zoolog 2014, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkie, I.C.; Candia Carnevali, M.D.; Andrietti, F. Mechanical properties of sea-urchin lantern muscles: A comparative investigation of intact muscle groups in Paracentrotus lividus (Lam.) and Stylocidaris affinis (Phil.) (Echinodermata, Echinoidea). J Comp Physiol B 1998, 168, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, T.C.; Gemmell, B.J.; von Dassow, G.; Conley, K.R.; Sutherland, K.R. The hydrodynamics and kinematics of the appendicularian tail underpin peristaltic pumping. J Roy Soc Interface 2023, 20, 20230404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindskog, C.; Linné, J.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Sundberg, C.J.; Lindholm, M.; Huss, M.; Kampf, C.; Choi, H.; Liem, D.A.; Ping, P.; Väremo, L.; Mardinoglu, A.; Nielsen, J.; Larsson, E.; Pontén, F.; Uhlén, M. The human cardiac and skeletal muscle proteomes defined by transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenauer, R.; Bertoncini, P.; Machaidze, G.; Aebi, U.; Perriard, J.C.; Hegner, M.; Agarkova, I. Myomesin is a molecular spring with adaptable elasticity. J Mol Biol 2005, 349, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abascal, F.; Zardoya, R. Evolutionary analyses of gap junction protein families. Biochimica Biophysica Acta 2013, 1828, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucaciu, S.A.; Leighton, S.E.; Hauser, A.; Yee, R.; Laird, D.W. Diversity in connexin biology. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; et al. (Eds.) Neuroscience, 2nd edition; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- More, H.L.; O’Connor, S.M.; Brøndum, E.; Wang, T.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Grøndahl, C.; Kastberg, K.; Hørlyck, A.; Funder, J.; Maxwell Donelan, J. Sensorimotor responsiveness and resolution in the giraffe. J Exp Biol 2013, 216, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, M.T.; Heibeck, S.; Topperwien, M.; tom Dieck, S.; Ruhwedel, T.; Salditt, T.; Rodicio, M.C.; Morgan, J.R.; Nave, K.A.; Mobius, W.; Werner, H.B. Axonal ensheathment in the nervous system of lamprey: Implications for the evolution of myelinating glia. J Neurosci 2018, 38, 6586–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.M.; Morrison, H.G.; Gilland, E.; Campbell, R.K. Myelin tetraspan family proteins but no non-tetraspan family proteins are present in the ascidian (Ciona intestinalis) genome. Biol Bull 2005, 209, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.D.; Ciatto, C.; Chen, C.P.; Bahna, F.; Rajebhosale, M.; Arkus, N.; Schieren, I.; Jessell, T.M.; Honig, B.; Price, S.R.; Shapiro, L. Type II cadherin ectodomain structures: Implications for classical cadherin specificity. Cell 2006, 124, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneyhill, L.A. To adhere or not to adhere: The role of cadherins in neural crest development. Cell Adhesion & Migration 2008, 2, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, H.; Akiyama-Oda, Y.; Zhang, S. Two classic cadherin-related molecules with no cadherin extracellular repeats in the cephalochordate amphioxus: Distinct adhesive specificities and possible involvement in the development of multicell-layered structures. J Cell Sci 2003, 117, 2757–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.R.; McCauley, D.W. The origin and evolution of vertebrate neural crest cells. Open Biol 2020, 10, 190285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, T.; Satoh, N. A comprehensive survey of cadherin superfamily gene expression patterns in Ciona intestinalis. Gene Expression Patterns 2008, 8, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, W.R.; Chiba, T.; Krajka, F.R.; Deyts, C.; Satoh, N.; Joly, J.S. Trunk lateral cells are neural crest-like cells in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis: Insights into the ancestry and evolution of the neural crest. Dev Biol 2008, 324, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niessen, C.M.; Leckband, D.; Yap, A.S. Tissue organization by cadherin adhesion molecules: Dynamic molecular and cellular mechanisms of morphogenetic regulation. Physiol Rev 2011, 91, 691–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.C.; Nazarko, O.V.; Sando, R., III; Salzman, G.S.; Li, N.S.; Südhof, T.C.; Araç, D. Structural basis of latrophilin-FLRT-UNC5 interaction in cell adhesion. Structure 2015, 23, 1678–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Toro, D.; Carrasquero-Ordaz, M.A.; Chu, A.; Ruff, T.; Shahin, M.; Jackson, V.A.; Chavent, M.; Berbeira-Santana, M.; Seyit-Bremer, G.; Brignani, S.; Kaufmann, R.; Lowe, E.; Klein, R.; Seiradake, E. Structural basis of teneurin-latrophilin interaction in repulsive guidance of migrating neurons. Cell 2020, 180, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuse, M.; Fujita, K.; Hiiragi, T.; Fujimoto, K.; Tsukita, S. Claudin-1 and -2: Novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J Cell Biol 1998, 141, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günzel, D.; Yu, A.S.L. Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol Rev 2013, 93, 525–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmar, R.; Nakamura, S.K.; Kappler, J.A.; Hudspeth, A.J. Expression and phylogeny of claudins in vertebrate primordia. PNAS 2001, 98, 1810196–10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellott, D.O.; Burke, R.D. The molecular phylogeny of eph receptors and ephrin ligands. BMC Cell Biol 2008, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.; Campbell, J.; Nobes, C.D. Ephs and ephrins. Curr Biol 2027, 27, R83–R102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williaume, G.; de Buyl, S.; Sirour, C.; Haupaix, N.; Bettoni, R.; Imai, K.S.; Satou, Y.; Dupont, G.; Hudson, C.; Yasuo, H. Cell geometry, signal dampening, and a bimodal transcriptional response underlie the spatial precision of an ERK-mediated embryonic induction. Dev Cell 2021, 56, 2966–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiuza, U.M.; Negishi, T.; Rouan, A.; Yasuo, H.; Lemaire, P. A Nodal/Eph signalling relay drives the transition from apical constriction to apico-basal shortening in ascidian endoderm invagination. Development 2020, 147, dev186965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negishi, T.; Nishida, H. Asymmetric and Unequal Cell Divisions in Ascidian Embryos. In Asymmetric cell division in development, differentiation and cancer; Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation; Tassan, J.P., Kubiak, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2017; Volume 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupaix, N.; Abitua, P.B.; Sirour, C.; Yasuo, H.; Levine, M.; Hudson, C. Ephrin-mediated restriction of ERK1/2 activity delimits the number of pigment cells in the Ciona CNS. Dev Biol 2014, 394, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolfi, A.; Wagner, E.; Taliaferro, J.M.; Chou, S.; Levine, M. Neural tube patterning by Ephrin, FGF and Notch signaling relays. Development 2011, 138, 5429–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, R.R.F.; Chen, H.; Lee, A.K.; Daly, C.A.; Wilander, B.A.; Fon Tacer, K.; Potts, P.R. Emerging roles of the MAGE protein family in stress response pathways. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 16121–16155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.E.; Wistow, G.; Su, Y.A.; Meltzer, P.S.; Trent, J.M. AIM1, a novel non-lens member of the bg-crystallin superfamily, is associated with the control of tumorigenicity in human malignant melanoma. PNAS 1997, 94, 3229–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimeld Sebastian, M.; Purkiss, A.G.; Dirks, R.P.H.; Bateman, O.A.; Slingsby, C.; Lubsen, N.H. Urochordate-crystallin and the evolutionary origin of the vertebrate eye lens. Curr Biol 2005, 15, 1684–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riyahi, K.; Shimeld, S.M. Chordate βγ-crystallins and the evolutionary developmental biology of the vertebrate lens. Comp Biochem Physiol Part B 2007, 147, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappe, G.; Purkiss, A.G.; van Genesen, S.T.; Slingsby, C.; Lubsen, N.H. Explosive expansion of bc-crystallin genes in the ancestral vertebrate. J Mol Evol 2010, 71, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingsby, C.; Wistow, G.J.; Clark, A.R. Evolution of crystallins for a role in the vertebrate eye lens. Prot Science 2013, 22, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvekl, A.; Zhao, Y.; McGreal, R.; Xie, Q.; Gu, X.; Zheng, D. Evolutionary origins of Pax6 control of crystallin genes. Genome Biol Evol 2017, 9, 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenga, F.; Wunderera, J.; Salvenmosera, W.; Hessb, M.W.; Ladurnera, P.; Rothbächera, U. Papillae revisited and the nature of the adhesive secreting collocytes. Dev Biol 2019, 448, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horie, T.; Sakurai, D.; Ohtsuki, H.; Terakita, A.; Shichida, Y.; Usukura, J.; Kusakabe, T.; Tsuda, M. Pigmented and nonpigmented ocelli in the brain vesicle of the ascidian larva. J Comp Neur 2008, 509, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlyuk, N.; Sengupta, S.; Bierma, J.C.; Martin, R.W. Calcium binding dramatically stabilizes an ancestral crystallin fold in tunicate βγ-crystallin. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 6961–6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.M.; Bronner, G.; Kuttner, F.; Jurgens, G.; Jackie, H. Distal-less encodes a homoeodomain protein required for limb development in Drosophila. Nature 1989, 338, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.A.; Nulsen, C.; Nagy, L.M. A complex role for distal-less in crustacean appendage development. Dev Biol 2002, 241, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Hammid, A.; Umair, M.; Ahmad, W. A novel heterozygous intragenic sequence variant in DLX6 probably underlies first case of autosomal dominant split-hand/foot malformation type 1. Mol Syndromol 2017, 8, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, D. Many ways to build a polyp. Trends Gen 2019, 35, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, C.J.; Wray, G.A. Radical alterations in the roles of homeobox genes during echinoderm evolution. Nature 1997, 389, 718–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prpic, N.M.; Tautz, D. The expression of the proximodistal axis patterning genes Distal-less and dachshund in the appendages of Glomeris marginata (Myriapoda: Diplopoda) suggests a special role of these genes in patterning the head appendages. Dev Biol 2003, 260, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, A.; Di Gregorio, A.; Aniello, F.; Di Lauro, R.; Branno, M. Identification and developmental expression of three Distal-less homeobox containing genes in the ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Mech Dev 2000, 99, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, N.D.; Panganiban, G.; Henyey, E.L.; Holland, L.Z. Sequence and developmental expression of amphidll, an amphioxus Distal-less gene transcribed in the ectoderm, epidermis and nervous system: Insights into evolution of craniate forebrain and neural crest. Development 1996, 122, 2911–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyamala, K.; Yanduri, S.; Girish, H.C.; Murgod, S. Neural crest: The fourth germ layer. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2015, 19, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; DeLeon, C.; Sun, W.; Quae, S.R.; Roth, B.L.; Südhof, T.C. Alternative splicing of latrophilin-3 controls synapse formation. Nature 2024, 626, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, P.A.J. Caldesmon. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1997, 29, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polanco, J.; Reyes-Vigil, F.; Weisberg, S.D.; Dhimitruka, I.; Brusés, J.L. differential spatiotemporal expression of type i and type ii cadherins associated with the segmentation of the central nervous system and formation of brain nuclei in the developing mouse. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, H.; Munro, E. Differential expression of a classic cadherin directs tissue-level contractile asymmetry during neural tube closure. Dev Cell 2019, 51, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulson, A.F.; Prasad, M.S.; Thuringer, A.H. Manzerra P. Regulation of cadherin expression in nervous system development. Cell Adhesion & Migration 2014, 8, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, H.; Yamaoka, A.; Hamashima, T.; Shima, A.; Kosako, M.; Tahara, Y.; Kamishikiryo, J.; Michihara, A. EGF-dependent activation of ELK1 contributes to the induction of CLDND1 expression involved in tight junction formation. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exposito, J.Y.; Cluzel, C.; Garrone, R.; Lethias, C. Evolution of collagens. Anatom Rec 2002, 268, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panganiban, G.; Rubenstein, J.L.R. Developmental functions of the Distal-less/Dlx homeobox genes. Development 2002, 129, 4371–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolfi, A.; Gainous, T.B.; Young, J.J.; Mori, A.; Levine, M.; Christiaen, L. Early chordate origins of the vertebrate second heart field. Science 2010, 329, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, C.; Gossel’, K.A.; Balaz, M.; Balazova, L.; Horvath, C.; Künzle, P.; Okreglicka, K.M.; Li, F.; Blüher, M.; Stierstorferf, B.; Hessf, E.; Lamla, T.; Hamilton, B.; Klein, H.; Neubauerf, H.; Wolfrum, C.; Wolfrum, S. FAM3D: A gut secreted protein and its potential in the regulation of glucose metabolism. Peptides 2023, 167, 171047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, D.; Xie, L.; Wang, A.; Zhao, H.; Guo, C.; Sun, Y.; Nie, Y.; Hong, A.; Xiong, S. SCF-FBXO24 regulates cell proliferation by mediating ubiquitination and degradation of PRMT6. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 2020, 530, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satou, Y.; Tokuoka, M.; Oda-Ishii, I.; Tokuhiro, S.; Ishida, T.; Liu, B.; Iwamura, Y. A manually curated gene model set for an ascidian, Ciona robusta (Ciona intestinalis type A). Zool Sci 2022, 39, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.M.; Khairallah, S.M.; Nguyen, A.H.; Newman-Smith, E.; Smith, W.C. Misregulation of cell adhesion molecules in the Ciona neural tube closure mutant bugeye. Dev Biol 2021, 480, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abitua, P.B.; Gainous, T.B.; Kaczmarczyk, A.N.; Winchell, C.J.; Hudson, C.; Kamata, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Tsuda, M.; Kusakabe, T.G.; Levine, M. The pre-vertebrate origins of neurogenic placodes. Nature 2015, 524, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edvardsen, R.B.; Seo, H.C.; Jensen, M.F.; Mialon, A.; Mikhaleva, J.; Bjordal, M.; Cartry, J.; Reinhardt, R.; Weissenbach, J.; Wincker, P.; Chourrout, D. Remodelling of the homeobox gene complement in the tunicate Oikopleura dioica. Curr Biol 2005, 15, R12–R13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labat-de-Hoz, L.; Rubio-Ramos, A.; Correas, I.; Alonso, M.A. The MAL family of proteins: Normal function, expression in cancer, and potential use as cancer biomarkers. Cancers 2023, 15, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Pai, C.W.; Huang, S.W.; Chang, S.N.; Lin, L.Y.; Chiang, F.T.; Lin, J.L.; Hwang, J.J.; Tsai, C.T. Inactivation of myosin binding protein C homolog in zebrafish as a model for human cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc 2013, 2, e000231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razy-Krajka, F.; Stolf, A. Regulation and evolution of muscle development in tunicates. EvoDevo 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heissler, S.M.; Sellers, J.R. Myosin light chains: Teaching old dogs new tricks. Bioarchitecture 2014, 4, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, I.; Gholkar, A.A.; Velasquez, E.F.; Guo, X.; Tofig, B.; Damoiseaux, R.; Torres, J.Z. The myosin regulatory light chain Myl5 localizes to mitotic spindle poles and is required for proper cell division. Cytoskeleton 2021, 78, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.F.; Gillis, T.E. Evolution of the regulatory control of vertebrate striated muscle: The roles of troponin I and myosin binding protein-C. Physiol Genomics 2010, 42, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langea, S.; Pinotsisc, N.; Agarkovad, I.; Ehlere, E. The M-band: The underestimated part of the sarcomere. BBA Mol Cell Res 2020, 1867, 118440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Pasquier, L. Speculations on the origin of the vertebrate immune system. Immunol Lett. 2004, 92, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juriloff, D.M.; Harris, M.J. Insights into the etiology of mammalian neural tube closure defects from developmental, genetic and evolutionary studies. J Dev Biol 2018, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Martinez, O.; Shah, R.; Jamrich, M. Pitx3 controls multiple aspects of lens development. Dev Dyn 2009, 238, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, S.J.; Hesser, B.A.; Masuda, E.S.; Scheller, R.H. Amisyn, a novel syntaxin-binding protein that may regulate snare complex assembly. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 28271–28279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Jin, J.P. TNNT1, TNNT2, and TNNT3: Isoform genes, regulation, and structure-function relationships. Gene 2016, 582, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satou, Y.; Imai, K.S. Ascidian Zic Genes. In Zic family. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Aruga, J., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HGNC | Steps | equal to mode | HGNC | Steps | equal to mode | |

| ADGRL3 | 3.15 | 4 | MGAT4D | 4.08 | 4 | |

| ANKRD16 | 4.77 | 4 | MSMP | 1.15 | 6 | |

| ANKRD42 | 2.38 | 8 | MUM1 | 2.10 | 5 | |

| ARHGEF38 | 2.67 | 4 | MYBPC3 | 2.08 | 6 | |

| ASB2 | 3.92 | 5 | MYL5 | 5.01 | 3 | |

| ATRAID | 0.46 | 11 | NEBL | 2.16 | 6 | |

| BCL6B | 2.95 | 4 | NECTIN3 | 1.85 | 4 | |

| C18ORF21 | 0.62 | 9 | NEXN | 2.46 | 5 | |

| CALML6 | 2.47 | 8 | NPC1L1 | 4.85 | 5 | |

| CASR | 1.92 | 7 | OLFML2A | 1.54 | 5 | |

| CATIP | 3.18 | 4 | OTULIN | 1.55 | 7 | |

| CBLN1 | 1.38 | 4 | PDX1 | 2.77 | 4 | |

| CCDC78 | 2.62 | 4 | PHF21A | 2.46 | 4 | |

| CEP63 | 3.40 | 5 | PODN | 3.46 | 4 | |

| CEP83 | 2.46 | 7 | PRR14 | 2.27 | 6 | |

| CKAP2 | 2.54 | 5 | RBM14 | 3.61 | 3 | |

| CLDN1 | 0.83 | 7 | RHBDL2 | 4.54 | 4 | |

| CLDN18 | 1.25 | 5 | RNF4 | 4.85 | 3 | |

| CLDN19 | 0.92 | 7 | SCLT1 | 3.18 | 6 | |

| CLDN7 | 1.23 | 6 | SERINC5 | 4.38 | 5 | |

| EFNA1 | 1.92 | 4 | SLC35G2 | 3.31 | 4 | |

| FABP2 | 1.00 | 8 | SLC35G3 | 4.86 | 3 | |

| FAM155B | 1.54 | 5 | SLC35G4 | 5.13 | 3 | |

| FAM187A | 1.23 | 6 | SLC35G5 | 5.50 | 3 | |

| FAM3D | 2.38 | 4 | SLC35G6 | 4.25 | 4 | |

| FBXO24 | 2.23 | 6 | SLC6A14 | 3.54 | 3 | |

| FOXH1 | 2.95 | 5 | SLC6A6 | 3.46 | 4 | |

| GJA10 | 2.02 | 5 | SNRNP48 | 2.31 | 8 | |

| GJA3 | 1.16 | 7 | SPATA21 | 4.50 | 3 | |

| GJC2 | 2.38 | 6 | STXBP6 | 1.77 | 8 | |

| GNA15 | 4.00 | 3 | TGFB1 | 2.15 | 4 | |

| GTF2IRD2 | 3.00 | 3 | TGFB2 | 1.54 | 6 | |

| GTF2IRD2B | 4.30 | 3 | TLCD2 | 3.62 | 3 | |

| GVQW1 | 4.05 | 2 | TMEM218 | 0.62 | 9 | |

| H1FOO | 3.23 | 3 | TNNC1 | 4.08 | 6 | |

| HMMR | 2.92 | 8 | TNNC2 | 4.08 | 4 | |

| HNF1A | 1.15 | 7 | TSPAN12 | 2.69 | 5 | |

| HSPB1 | 3.23 | 3 | WSB1 | 2.31 | 4 | |

| IKZF5 | 2.85 | 5 | ZBED5 | 2.46 | 4 | |

| IL17C | 1.78 | 4 | ZBED8 | 2.83 | 4 | |

| KIZ | 1.23 | 6 | ZC3H7B | 1.38 | 8 | |

| LRRC29 | 3.09 | 4 | ZNF91 | 4.88 | 2 |

| HGNC | Unique ID * | Uniprot | Expect value ** |

| MYBPC1 | Cirobu.g00000146 | Q00872 | 0 |

| MYBPC2 | Cirobu.g00000146 | Q14324 | 0 |

| MYBPC3 | Cirobu.g00000146 | Q14896 | 0 |

| MYH1 | Boschl.g00071919 | P12882 | 0 as myosin heavy chain, cardiac muscle isoform Ciona intestinalis |

| MYH13 | Harore.g00014293 | Q9UKX3 | 0 as embryonic muscle myosin heavy chain Halocynthia roretzi |

| MYH15 | Harore.g00003537 | Q9Y2K3 | 0 as embryonic muscle myosin heavy chain Halocynthia roretzi |

| MYH4 | Cirobu.g00005587 | Q9Y623 | 0 as myosin heavy chain, cardiac muscle isoform Ciona intestinalis |

| MYH8 | Harore.g00010698 | P13535 | 0 as embryonic muscle myosin heavy chain Halocynthia roretzi |

| MYL4 | Cirobu.g00008856 | P12829 | 2E-74 as smooth muscle isoform X3 of Ciona intestinalis |

| MYL5 | Cirobu.g00008931 | Q02045 | 2.00E-82 |

| MYL7 | Cirobu.g00009534 | Q01449 | 3E-73 as smooth muscle isoform X1 of Ciona intestinalis |

| MYOM1 | Phmamm.g00001992 | P52179 | 7.00E-93 |

| MYBPC1 | Cirobu.g00000146 | Q00872 | 0 |

| MYBPC2 | Cirobu.g00000146 | Q14324 | 0 |

| MYBPC3 | Cirobu.g00000146 | Q14896 | 0 |

| PALLD | Cirobu.g00008036 | Q8WX93 | 1.00E-109 |

| SYNPO2 | Boleac.g00003200 | Q9UMS6 | 2.00E-13 |

| TNNT1 | Cirobu.g00006671 | P13805 | 8E-85 as TroponinT, slow skletal muscle of Ciona intestinalis |

| HGNC Symbol | Uniprot Symbol | Expect Value * | XP_026690575.1 |

| GJA4 | P35212 | 4.00E-41 | XP_002119855.2 |

| GJA5 | P36382 | 1.00E-32 | XP_004227068.2 |

| GJA8 | P48165 | 3.00E-57 | CAB3249107.1 |

| GJB1 | P08034 | 6.00E-34 | CAB3249120.1 |

| GJB2 | P29033 | 7.00E-35 | XP_026696017.1 |

| GJB6 | O95452 | 3.00E-47 | XP_002130872.1 |

| GJC1 | P36383 | 3.00E-67 | XP_026691633.1 |

| * The Expect values were from 2-sequence BLAST analyses against the corresponding human homolog | ** from BLAST search. Click to retrieve the FASTA sequence | ||

| Ephron Genes | Ephrin Genes | ||

| HGNC symbol | Latest ortholog in: | HGNC symbol | Latest ortholog in: |

| EPHA2 | Tunicata | EFNA1 | Tunicata |

| EPHA3 | Elasmobranchii | EFNA2 | Tunicata |

| EPHA4 | Tunicata | EFNA3 | Tunicata |

| EPHA5 | Branchiostomata | EFNA4 | Tunicata |

| EPHA6 | Elasmobranchii | EFNA5 | Tunicata |

| EPHA7 | Elasmobranchii | EFNB1 | Tunicata |

| EPHA8 | Elasmobranchii | EFNB2 | Branchiostomato |

| EPHA10 | Osteichthyes | EFNB3 | Elasmobranchii |

| EPHB2 | Branchiostomata | ||

| EPHB3 | Elasmobranchii | ||

| EPHB4 | Cnidaria | ||

| Term | Genes | FDR * | |

| Cluster 2 | |||

| heterophilic cell-cell adhesion via plasma membrane cell adhesion molecules | NECTIN3, CBLN1, NECTIN1 | 0.358759 | |

| identical protein binding | TFAP2E, COL23A1, HSPB1, NECTIN3, CBLN1, NECTIN1 | 0.671885 | |

| Cluster 4 | Synapse | NECTIN3, CBLN1, NECTIN1 | 0.935728 |

| homophilic cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules | PALLD, NECTIN3, NECTIN1 | 0.739434 | |

| DOMAIN:Ig-like C2-type 1 | PALLD, NECTIN3, NECTIN1 | 0.656496 | |

| DOMAIN:Ig-like C2-type 2 | PALLD, NECTIN3, NECTIN1 | 0.656496 | |

| Immunoglobulin domain | PALLD, NECTIN3, NECTIN1 | 0.877976 | |

| Immunoglobulin-like fold | PALLD, NECTIN3, NECTIN1 | 0.984375 | |

| Cluster 6 | |||

| Z disc | PALLD, SYNPO2, HSPB1 | 0.481232 | |

| actin cytoskeleton | CALD1, PALLD, SYNPO2 | 0.564483 | |

| actin binding | CALD1, PALLD, SYNPO2 | 0.614614 | |

| focal adhesion | PALLD, SYNPO2, HSPB1 | 0.679141 | |

| Cluster 7 | |||

| Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells | FZD3, ZIC3, FZD6 | 0.180791 | |

| Developmental protein | FZD3, ZIC3, FZD6, PITX3 | 0.819281 | |

| Cluster 8 | |||

| Zinc | ZMAT1, ZIC3, ASXL3 | 1 | |

| Zinc-finger | ZMAT1, ZIC3, ASXL3 | 0.988184 | |

| Metal-binding | ZMAT1, ZIC3, ASXL3 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).