1. Background

Spondylodiscitis are infections that affect the spine, particularly the vertebrae and intervertebral discs. Spinal infections can be described etiologically as pyogenic, granulomatous (tuberculous, brucellar, fungal) and parasitic [

1]. Spreading to the vertebrae and intervertebral discs can occur either by hematogenous seeding or by exogenous inoculation [

1].

Invasive candidiasis is the infection of a sterile site by

Candida spp., and includes both candidaemia and deep-seated tissue candidiasis, which arises from dissemination of

Candida spp. to a sterile body site (e.g., endocarditis, peritonitis, endophthalmitis) [

2].

Candida spp. spondylodiscitis (CS) is a rare manifestation of invasive candidiasis: only 89 cases of culture confirmed CS have been reported so far, according to a recent meta-analysis [

3].

Candida albicans spondylodiscitis was the most frequent species isolated and only 6 cases of

C. parapsilosis were described [

3].

C. parapsilosis represents a high risk for immunocompromised individuals and surgical patients, particularly those subjected to gastrointestinal track surgery. The incidence of

C. parapsilosis infections in Europe is region-dependent; in Southern European hospitals (Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Greece) it is the second most isolated species [

4].

The last results from the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Candida III study, an observational study assess

Candida spp. distribution and antifungal resistance of candidaemia across Europe found, found that acquired fluconazole resistance was common in

C. glabrata and

C. parapsilosis and a 24% rate of fluconazole resistant

C. parapsilosis in Greece, Italy and particularly Turkey [

5].

According to meta-analysis by Adelhoefer and colleagues, among the 89 included patients with CS, antifungal monotherapy was given in 58%: the most commonly used antifungal agents were fluconazole (68%), amphotericin B (38%), and echinocandins (26%), and the median length of antifungal treatment was six months [

3]. Surgical intervention was performed in 68%, including 34% undergoing instrumented discectomy [

3]. At a median follow-up of 12 months, 3% developed sepsis, 6% underwent revision, and 12% died of disease [

3]. Younger age (p = 0.042) and longer length of antifungal therapy (p = 0.061) were predictive of survival, whereas outcome did not differ based on Candida strain (p = 0.74) and affected spinal level (p = 0.44) [

3].

No definitive indications for treatment of CS exist, but the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends treating

Candida spp. osteomyelitis with fluconazole 6 mg/kg daily for 6 to 12 months, or an echinocandin or liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) for 2 weeks, followed by long-term fluconazole [

6].

Rezafungin is a novel semisynthetic, long-acting second-generation echinocandin derived from anidulafungin with favorable pharmacokinetic properties due to structural modifications [

7]. It has several advantages over the already approved echinocandins as it has better tissue penetration, better pharmacokinetic/phamacodynamic (PK/PD) pharmacometrics, and a good safety profile [

7]. Rezafungin exhibits superior stability in solution compared to older echinocandins, enhancing its versatility in dosing, storage, and production [

7]. This enhanced stability facilitates once-weekly administration via intravenous route and holds potential for topical and subcutaneous application. Furthermore, higher dosage regimens have been evaluated without any observed toxic effects, which could ultimately mitigate the emergence or proliferation of resistant strains [

7].

Despite

C. parapsilosis isolates have shown the highest in vitro MICs for rezafungin (1.657, 0.063->4) among all the Candida species, according to a multicenter study across four European laboratory [

8], rezafungin was able to inhibit 100% of

C. parapsilosis isolates at ≤4 μg/ml with MIC50/90 of 1/2 μg/ml in a worldwide collection of 2,205 invasive fungal isolates recovered from 2016 to 2018 and interpretated with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth microdilution methods [

9].

In phase 2 (STRIVE) trial, adults with candidemia and/or invasive candidiasis were randomized to receive either rezafungin 400 mg once weekly or rezafungin 400 mg on week 1 followed by 200 mg once weekly or caspofungin 70 mg as a loading dose, followed by 50 mg daily for ≤4 weeks [

10]. The overall cure rate was highest for rezafungin 400/200 mg compared to rezafungin 400 mg or caspofungin (76.1% vs 60.5% vs 67.2%, respectively) and the mortality rate was lowest for rezafungin 400/200 mg compared to rezafungin 400 mg or caspofungin (4.4% vs 15.8% vs 13.1%, respectively), with candidemia cleared earlier in patients on rezafungin than those receiving caspofungin [

10].

Moreover, in phase 3 (ReSTORE) trial, adults with systemic signs and mycological confirmation of candidaemia or invasive candidiasis were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive intravenous rezafungin once a week (400 mg in week 1, followed by 200 mg weekly, for a total of two to four doses) or intravenous caspofungin (70 mg loading dose on day 1, followed by 50 mg daily) for no more than 4 weeks [

11]. The global cure rate at day 14 was 59% in the rezafungin group, compared to 61% in the caspofungin group, while 30-day mortality was 24% and 21% in the rezafungin and caspofungin groups, respectively, thus showing non-inferiority of rezafungin to caspofungin [

11].

Nonetheless, patients with osteoarticular infections were excluded from the abovementioned trials and only few case reports have described its use for more than 4 weeks and for infections outside the bloodstream [

12,

13,

14].

We hereby report the first use of rezafungin for a CS due to Candida parapsilosis with reduced susceptibility to azoles.

2. Case Report

A 68 years-old patient was admitted to our ward for persistent febrile episodes. Patient’s remote history was characterized by: paraplegia due to vertebral trauma after car accident, with complete injury at D4-D6 level, stabilized with trans peduncular bars and screws and complicated with sub lesional syringomyelia and complete sub lesional anesthesia; short bowel syndrome after ileo-cecal resection with latero-lateral ileo-colic anastomosis, due to bowel volvulus, on home parenteral nutrition via peripherally inserted central venous catheter (PICC); paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; neurogenic bladder on self-catheterization.

The patient reported the onset of fever and subcutaneous swelling at D7-D9 level from March 2023. Blood cultures collected at home from peripheral vein in May 2023 yielded azole resistant Candida parapsilosis, for which he hadn’t received therapy. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination in May 2023 showed fluid collection at the level of the subcutaneous tissue at D7-D8 and L4-L5 spondylodiscitis. The patient was then admitted to the Infectious Diseases ward of Federico II University Hospital at the beginning of June 2023.

Blood cultures and the tip of the removed PICC yielded

C. parapsilosis resistant to posaconazole, voriconazole and fluconazole (

Table 1). The therapy with anidulafungin 100 mg i.v. daily was started after 200 mg loading dose for treatment of candidemia, with negative surveillance blood cultures at 72 h. The patient underwent transesophageal echocardiography and fundus oculi examination as recommended for candidemia and were both negative for metastatic localization.

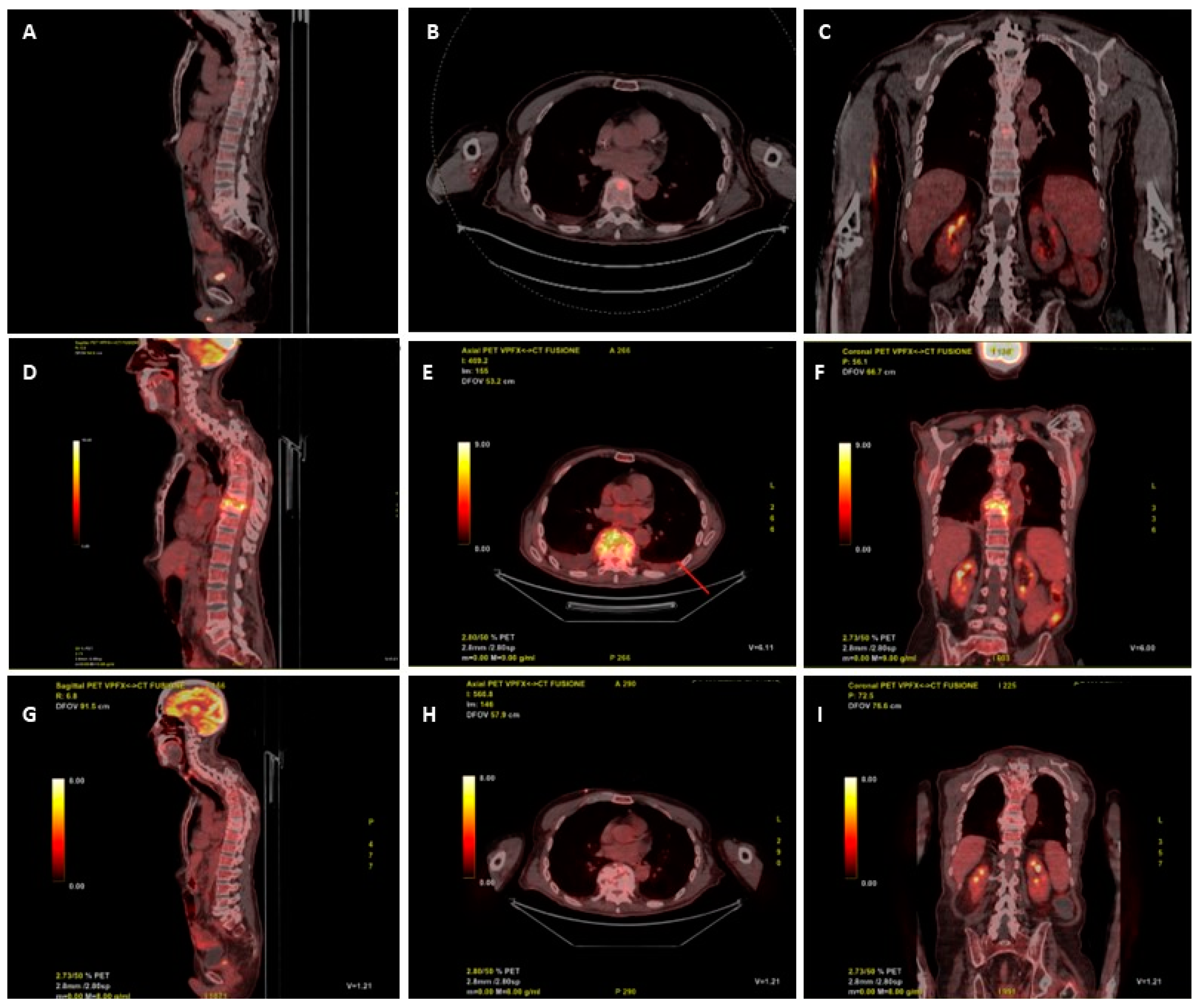

A 18-FDG-PET/CT scan requested on admission for suspected vertebral infection level showed a focal increased uptake in the body of D9 (SUV max 9.5) and in L4-L5 (SUV max 5.9) (

Figure 1 A, B, C). Ten days after start of anidulafungin therapy, the patient underwent a trans peduncular bone biopsy of D9, on which culture yielded fluconazole resistant

C. parapsilosis, with increased exposure sensitivity to voriconazole and sensitivity to itraconazole and posaconazole (

Table 1). The histopathologic examination of biopsy was unremarkable, mostly due to the scarcity of the sample.

In order to facilitate patient’s discharge to the outpatient parenteral hospital therapy service, antifungal therapy was switched to voriconazole 4 mg/kg orally every 12 hours plus liposomal amphotericin B 10 mg/kg i.v. three times a week. He started this therapy while he was still hospitalized. Meanwhile our center applied for a rezafungin expanded access program. The rational for this decision lies in several factors: the differences in susceptibility profiles of Candida parapsilosis in blood and in bone, the length of antifungal therapy required for the treatment of Candida spp. osteomyelitis and the concern about the actual absorption of an oral therapy because of intestinal resection performed by the patient in 2019.

Seven days after the start of therapy with voriconazole plus liposomal amphotericin B three times a week patient developed insomnia, hallucinations, prolonged QTc interval and hypokaliemia as side effects of current antifungal therapy. For this reason, on August 16th, antifungal therapy was stopped, the patient was discharged at home, and he received a loading dose of 400 mg i.v. of rezafungin, followed by 200 mg weekly.

He remained in good conditions, with persistently negative serum Beta-D-Glucan (BDG), through all the follow-up, during which he developed, in September and in October, two PICC-related bloodstream infections due to methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus haemolyticus, both treated with dalbavancin 1500 mg i.v. and catheter removal. A new 18-FDG-PET/CT was requested at the end of October, after 11 weeks of rezafungin, that showed increased glucose uptake between D9 and D10 (SUV 15.6), with no uptake at L4-L5 level (

Figure 1 D, E, F). A subsequent contrast enhanced spine MRI, performed two days later, showed signs of D8-D9 spondylodiscitis with epidural abscess between D7 and D11. Despite the patient was stable, afebrile and with negative C-reactive protein (CRP) and BDG, in the suspicion of therapeutic failure or coexistence of other diseases (neoplasm, mycobacterial or Staphylococcal superinfection) other multiple vertebral biopsies were collected at D8 and D9, all resulted negative for both mycobacteria (molecular, acid fast stain and culture), fungi, bacteria and with non-specific histopathology. Despite the unexplained radiological worsening, rezafungin was continued.

The patient remained in good condition, with persistently negative serum BDG and CRP, during follow-up. A new 18-FDG-PET/CT performed after 36 weeks of antifungal treatment (and after 26 weeks of rezafungin), showed remarkable reduction of 18-FDG uptake (SUV 2 vs. 15.6) at D9-D10 and no pathologic uptake at L4-L5 (

Figure 1 G, H, I), thus, antifungal therapy was stopped.

In summary, the patient received 200 mg weekly of rezafungin for 26 weeks (and a total of 36 weeks of effective antifungal therapy, when considering the previous therapies). He is still in good clinical condition, with negative CRP and serum BDG.

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a successful use of rezafungin for the treatment of an osteoarticular infection due to

Candida spp and one of the few cases in which it has been used for more than 4 weeks. In fact, in both phase 2 and 3 trials, the longest administration of rezafungin permitted per protocol was 28 days [

10,

11]. Moreover, patients with

Candida-associated septic arthritis in a prosthetic joint, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, or myocarditis, meningitis, chorioretinitis, CNS infection, as well as those affected by chronic disseminated candidiasis, or urinary tract candidiasis, were excluded from the trials [

10,

11].

Compassionate use of rezafungin for difficult-to-treat Candida infection has been reported in one case of aortic graft mediastinal infection, in which it has been used for more than 1 year; one case of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in a patient with primary immunodeficiency (5 weeks) and one case of intrabdominal candidiasis in a liver transplant recipient (12 weeks) [

12,

13,

14].

The rationale for using rezafungin in fluconazole-resistant

Candida spp. osteoarticular infections relies on bone penetration of anidulafungin, which, based on animal models, reach values similar to plasma concentrations, regardless of dosing duration, with bone/plasma concentration ratio of approximately 1.0 in neonatal rats [

15].

Other antifungal agents have proved to reach a bone/plasma concentration ratio ranging from >0.5 to ≤5 (itraconazole and 5-flucystosin) or >5 (voriconazole, amphotericin B deoxycolate) [

16]. Nonetheless, these drugs are characterized by high toxicity, needing for therapeutic drug monitoring or intravenous daily dosing, that makes them not appealing for a prolonged therapy. Conversely, rezafungin has shown to be safe, with no need for dose adjustment by age, body surface area and albumin levels in pharmacokinetic models [

17], with similar outcomes in obese patients in phase 2 trial [

18] and absence of significant drug-drug interactions [

19].

To overcome some limitations of current guidelines on candidemia and invasive candidiasis, the ECMM, in Cooperation with The International Society for Human & Animal Mycology (ISHAM), has recently developed an initiative for New Global Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candidiasis, that has recently undergone a public review and has still to be published. It is expected that rezafungin will receive a first-line indication for the treatment of candidemia alongside with echinocandin, but the role of this new molecule for the treatment of deep-seated infections is still to be clarified.

In our experience, the coexistence of quasispecies of Candida parapsilosis in blood and bone, including some azole-resistant strains, together with the presence of short bowel that might have impaired adequate therapeutic level of voriconazole, the development of toxicity from voriconazole and amphotericin, as well as the need for a long-term treatment, made our patient the ideal candidate for rezafungin via expanded access program.

Our patient had a satisfactory clinical and biochemical response to rezafungin, with no adverse reaction reported during therapy. We still cannot fully explain the increased FDG uptake that we found at the intermediate follow-up 18-FDG-PET/CT. We speculate that the patient underwent the first PET too early in the history of the infection, thus we cannot exclude that the radiological picture we found in October 2023 reflected an alteration that occurred in the first week after the first PET was performed, also because the patient has complete sub lesional anesthesia below D4, so we couldn’t rely on symptoms of pain or neurological worsening.

4. Conclusion

Rezafungin is a promising therapeutic option for patients with Candida osteomyelitis and with difficult-to-treat IC in general, especially when oral azole therapy is not an option. Further studies are required to understand the exact duration of therapy, the right dose, the need for therapeutic drug monitoring and the need for combination with other antifungals.

Author Contributions

G.V., I.G. and A.R.B. conceptualization and supervision; N.E., T.S., L.C. and C.G.M. formal analysis; G.V. and A.R.B. writing original draft; M.M.S. resources and project administration; I.G. and C.G.M. review and editing. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

no funding source has been used.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Ethical Committee Campania 3 have approved the EAP (deliberation of the 27th of July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient’s written informed consent was obtained for the participation to the EAP and for the publication of all the material, including radiological pictures.

Data availability

not applicable.

Aknowledgement

the authors want to acknowledge Mundipharma Research Limited for have provided rezafungin through the expanded access program (EAP).

Transparency declaration

All authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2010, 65, iii11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano A, Honore PM, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Vidal C, Pagotto A, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, et al. Invasive candidiasis: current clinical challenges and unmet needs in adult populations. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2023, 78, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelhoefer SJ, Gonzalez MR, Bedi A, Kienzle A, Bäcker HC, Andronic O, et al. Candida spondylodiscitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of seventy two studies. Int Orthop. 2024, 48, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branco J, Miranda IM, Rodrigues AG. Candida parapsilosis Virulence and Antifungal Resistance Mechanisms: A Comprehensive Review of Key Determinants. Journal of Fungi. 2023, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup MC, Arikan-Akdagli S, Jørgensen KM, Barac A, Steinmann J, Toscano C, et al. European candidaemia is characterised by notable differential epidemiology and susceptibility pattern: Results from the ECMM Candida III study. Journal of Infection. 2023, 87, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016, 62, e1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Effron, G. Rezafungin—Mechanisms of Action, Susceptibility and Resistance: Similarities and Differences with the Other Echinocandins. Journal of Fungi. 2020, 6, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup MC, Meletiadis J, Zaragoza O, Jørgensen KM, Marcos-Zambrano LJ, Kanioura L, et al. Multicentre determination of rezafungin (CD101) susceptibility of Candida species by the EUCAST method. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2018, 24, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller MA, Carvalhaes C, Messer SA, Rhomberg PR, Castanheira M. Activity of a Long-Acting Echinocandin, Rezafungin, and Comparator Antifungal Agents Tested against Contemporary Invasive Fungal Isolates (SENTRY Program, 2016 to 2018). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson GR, Soriano A, Skoutelis A, Vazquez JA, Honore PM, Horcajada JP, et al. Rezafungin Versus Caspofungin in a Phase 2, Randomized, Double-blind Study for the Treatment of Candidemia and Invasive Candidiasis: The STRIVE Trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021, 73, e3647–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson GR, Soriano A, Cornely OA, Kullberg BJ, Kollef M, Vazquez J, et al. Rezafungin versus caspofungin for treatment of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis (ReSTORE): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2023, 401, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechacek J, Yakubu I, Vissichelli NC, Bruno D, Morales MK. Successful expanded access use of rezafungin, a novel echinocandin, to eradicate refractory invasive candidiasis in a liver transplant recipient. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2022, 77, 2571–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melenotte C, Ratiney R, Hermine O, Bougnoux ME, Lanternier F. Successful Rezafungin Treatment of an Azole-Resistant Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis in a STAT-1 Gain-of-Function Patient. J Clin Immunol. 2023, 43, 1182–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 14. Adeel A, Qu MD, Siddiqui E, Levitz SM, Ellison RT. Expanded access use of rezafungin for salvage therapy of invasive Candida glabrata infection: A case report. Open Forum Infect Dis.

- Ripp SL, Aram JA, Bowman CJ, Chmielewski G, Conte U, Cross DM, et al. Tissue Distribution of Anidulafungin in Neonatal Rats. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2012, 95, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felton T, Troke PF, Hope WW. Tissue Penetration of Antifungal Agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014, 27, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roepcke S, Passarell J, Walker H, Flanagan S. Population pharmacokinetic modeling and target attainment analyses of rezafungin for the treatment of candidemia and invasive candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2023, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez JA, Flanagan S, Pappas P, Thompson GR, Sandison T, Honore PM. 637. Outcomes by Body Mass Index (BMI) in the STRIVE Phase 2 Trial of Once-Weekly Rezafungin for Treatment of Candidemia and Invasive Candidiasis Compared with Caspofungin. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020, 7, S378–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan S, Walker H, Ong V, Sandison T. Absence of Clinically Meaningful Drug-Drug Interactions with Rezafungin: Outcome of Investigations. Microbiol Spectr. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).