Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design & Patient enrolment

2.2. Sample Collection and Microbiology Methods

2.3. Statistical Methodology

3. Results

| Candida spp. | 2020 n (%) |

2021 n (%) |

2022 n (%) |

2023 n (%) |

2024 n (%) |

2020-2024 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 54 (45,8) | 26 (27,4) | 42 (51,9) | 61 (79,2) | 121 (78,1) | 304 (57,8) |

| C. glabrata | 46 (39,0) | 41 (43,2) | 23 (28,4) | 4 (5,2) | 25 (16,1) | 139 (26,4) |

| C. krusei | 12 (10,2) | 13 (13,7) | 8 (9,9) | 3 (3,9) | 4 (2,6) | 40 (7,6) |

| C. parapsilosis | 6 (5,1) | 9 (9,5) | 4 (4,9) | 4 (5,2) | 4 (2,6) | 27 (5,1) |

| C. tropicalis | 0 | 6 (6,3) | 4 (4,9) | 5 (6,5) | 1 (0,6) | 16 (3,0) |

| Total cases/year | 118 | 95 | 81 | 77 | 155 | 526 |

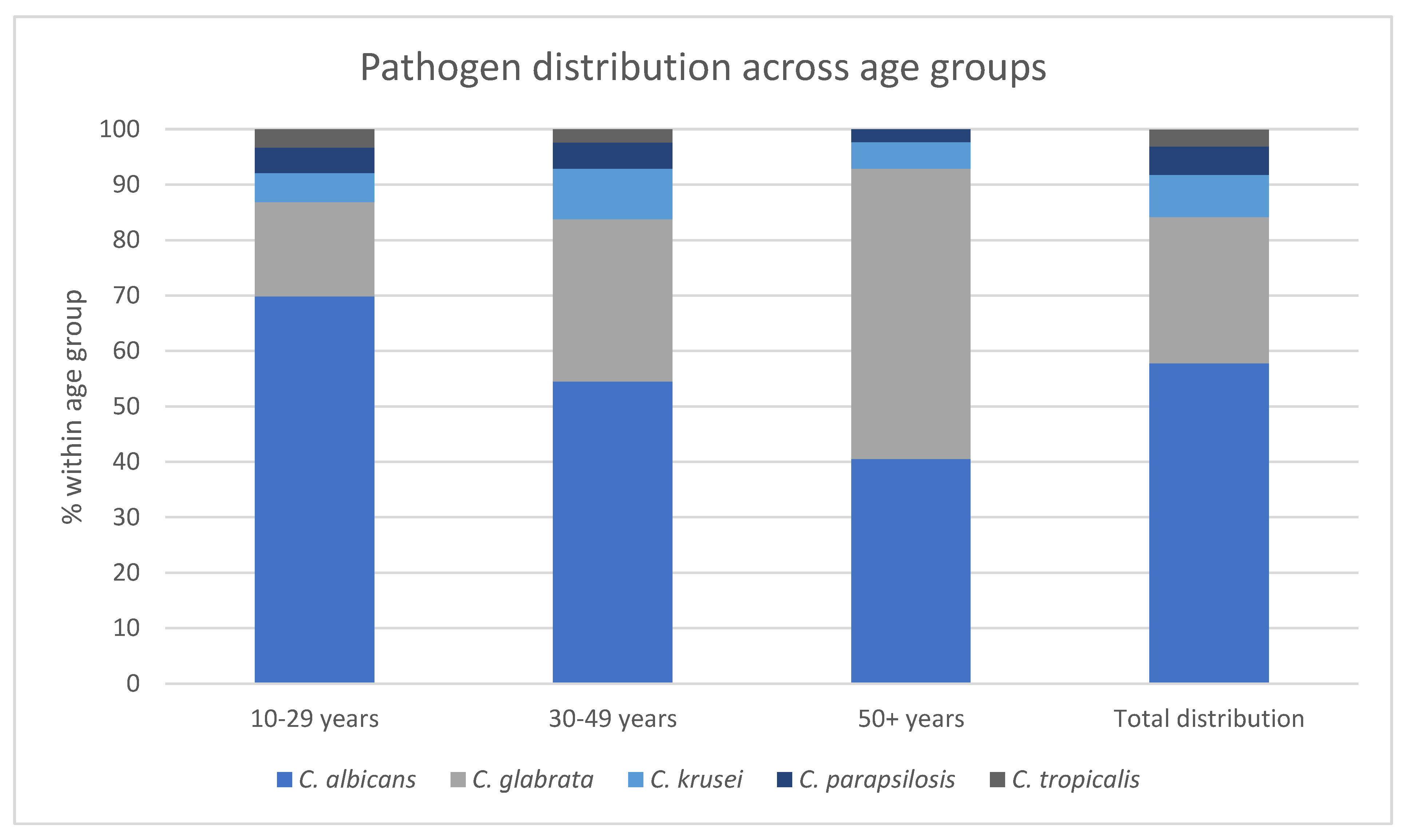

| Age group |

C. albicans n (% within age group) |

C. glabrata n (% within age group) |

C. krusei n (% within age group) |

C. parapsilosis n (% within age group) |

C. tropicalis n (% within age group) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-29 years | 113 (69,9) | 27 (17,0) | 9 (5,2) | 9 (4,6) | 7 (3,3) |

| 30-49 years | 168 (54,5) | 88 (29,3) | 28 (9,1) | 16 (4,7) | 9 (2,4) |

| 50+ years |

23 (40,5) | 24 (52,4) | 3 (4,8) | 2 (2,3) | 0 (0,0) |

| Total distribution | 304 (57,8) | 139 (26,4) | 40 (7,6) | 27 (5,1) | 16 (3,0) |

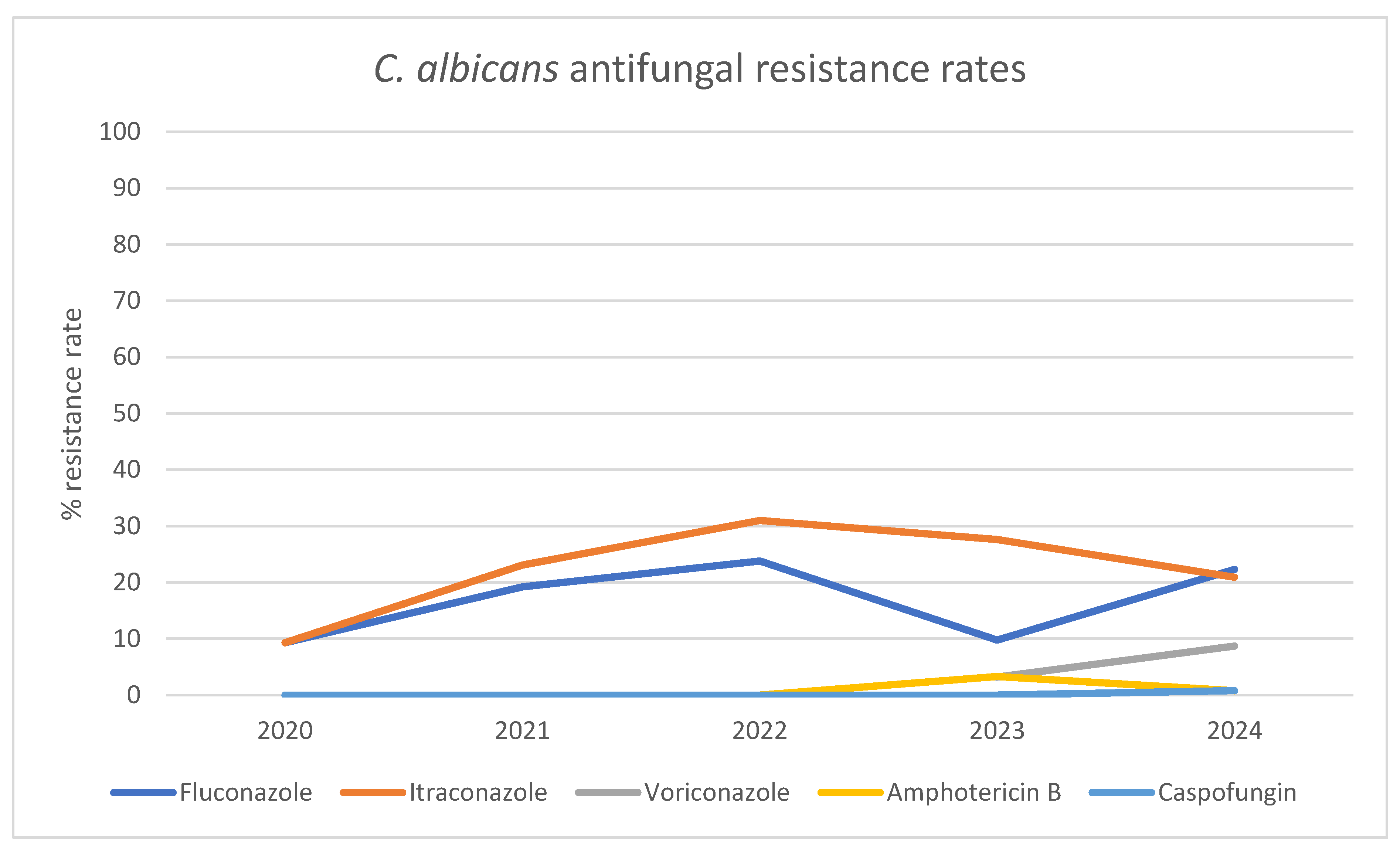

| Antifungal Agent | 2020 n (% Resistance Rate) |

2021 n (% Resistance Rate) |

2022 n (% Resistance Rate) |

2023 n (% Resistance Rate) |

2024 n (% Resistance Rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluconazole | 5 (9,3) |

5 (19,2) | 10 (23,8) | 6 (9,8) | 27 (22,3) |

| Itraconazole | 5 (9,3) |

6 (23,1) | 13 (31,0) | 8 (27,6) | 23 (20,9) |

| Voriconazole | ND |

ND | ND | 1 (3,2) | 8 (8,7) |

| Amphotericin B | 0 (0,0) |

0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 2 (3,3) | 1 (0,8) |

| Caspofungin | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (0,8) |

| NAC Species | Fluconazole n (% Resistance Rate) |

Itraconazole n (% Resistance Rate) |

Amphotericin B n (% Resistance Rate) |

Micafungin n (% Resistance Rate) |

Caspofungin n (% Resistance Rate) |

Anidulafungin n (% Resistance Rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. glabrata | 139 (100) |

139 (100) | 19 (13,7) | 0 (0,0) | 19 (13,8) | 0 (0,0) |

| C. krusei | 40 (100) | 40 (100) | 5 (13,2) | ND | ND | ND |

| C. parapsilosis | 1 (3,7) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

| C. tropicalis | 2 (12,5) | 1 (10,0) | 0 (0,0) | ND | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VVC | Vulvovaginal candidiasis |

| NAC | Non-albicans Candida |

| OTC | Over the counter |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

References

- Sobel, J.D. Vulvovaginal candidosis. Lancet (London, England) 2007, 369, 1961–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W.; Kneale, M.; Sobel, J.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Global burden of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2018, 18, e339–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrioli, J.L.; Oliveira, G.S.; Barreto, C.S.; Sousa, Z.L.; Oliveira, M.C.; Cazorla, I.M.; Fontana, R. [Frequency of yeasts in vaginal fluid of women with and without clinical suspicion of vulvovaginal candidiasis]. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2009, 31, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, L.; John, M.; Kalder, M.; Kostev, K. Prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis in gynecological practices in Germany: A retrospective study of 954,186 patients. Curr Med Mycol 2018, 4, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouri, I.; Sellami, H.; Borji, N.; Abbes, S.; Sellami, A.; Cheikhrouhou, F.; Maazoun, L.; Khaled, S.; Khrouf, S.; Boujelben, Y.; et al. Epidemiological survey of vulvovaginal candidosis in Sfax, Tunisia. Mycoses 2011, 54, e499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.S.; Morton, A.N.; Garland, S.M.; Morris, M.B.; Moss, L.M.; Fairley, C.K. Higher-risk behavioral practices associated with bacterial vaginosis compared with vaginal candidiasis. Obstet Gynecol 2005, 106, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E.; Stafylaki, D.; Nioti, E.; Hamilos, G.; Kasimati, A. Epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida isolates from Greek women with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Mycoses 2019, 62, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriou, O.; Baka, S.; Makrakis, E.; Hassiakos, D.; Kapparos, G.; Kouskouni, E. Prevalence of clinical vaginal candidiasis in a university hospital and possible risk factors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006, 126, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanjuola, O.; Bongomin, F.; Fayemiwo, S.A. An Update on the Roles of Non-albicans Candida Species in Vulvovaginitis. J Fungi (Basel) 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.G.; Hoffman, P.; El-Zaatari, M. Fungal species changes in the female genital tract. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2004, 8, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, M.; Poch, F.; Levin, D. High rate of vaginal infections caused by non-C. albicans Candida species among asymptomatic women. Med Mycol 2002, 40, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donders, G.G.; Marconi, C.; Bellen, G.; Donders, F.; Michiels, T. Effect of short training on vaginal fluid microscopy (wet mount) learning. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2015, 19, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donders, G.G.; Bellen, G. Anything wrong with conventional wet mount microscopy? J Low Genit Tract Dis 2014, 18, E26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, J.D.; Hay, P. Diagnostic techniques for bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis - requirement for a simple differential test. Expert Opin Med Diagn 2010, 4, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, K.; Lyman, M.; Jackson, B.R. Possible misdiagnosis, inappropriate empiric treatment, and opportunities for increased diagnostic testing for patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis-United States, 2018. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0267866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinosoglou, K.; Schinas, G.; Papageorgiou, D.; Polyzou, E.; Massie, Z.; Ozcelik, S.; Donders, F.; Donders, G. Rapid Molecular Diagnostics in Vulvovaginal Candidosis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2313–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, S.M.; Bared, E.E.; Fanous, R.; Kyriacos, S. Practices of Lebanese gynecologists regarding treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. N Am J Med Sci 2011, 3, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaig, L.F.; McNeil, M.M. Trends in prescribing for vulvovaginal candidiasis in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005, 14, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D.G.; Dekle, C.; Litaker, M.S. Women's use of over-the-counter antifungal medications for gynecologic symptoms. J Fam Pract 1996, 42, 595–600. [Google Scholar]

- Yano, J.; Sobel, J.D.; Nyirjesy, P.; Sobel, R.; Williams, V.L.; Yu, Q.; Noverr, M.C.; Fidel, P.L., Jr. Current patient perspectives of vulvovaginal candidiasis: incidence, symptoms, management and post-treatment outcomes. BMC Womens Health 2019, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardh, P.A.; Wagstrom, J.; Landgren, M.; Holmen, J. Usage of antifungal drugs for therapy of genital Candida infections, purchased as over-the-counter products or by prescription: 2. Factors that may have influenced the marked changes in sales volumes during the 1990s. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2004, 12, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- File, B.; Sobel, R.; Becker, M.; Nyirjesy, P. Fluconazole-Resistant Candida albicans Vaginal Infections at a Referral Center and Treated With Boric Acid. Journal of lower genital tract disease 2023, 27, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Ahmed, J.; Gul, A.; Ikram, A.; Lalani, F.K. Antifungal susceptibility testing of vulvovaginal Candida species among women attending antenatal clinic in tertiary care hospitals of Peshawar. Infection and Drug Resistance 2018, 11, 447–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinosoglou, K.; Livieratos, A.; Asimos, K.; Donders, F.; Donders, G.G.G. Fluconazole-Resistant Vulvovaginal Candidosis: An Update on Current Management. Pharmaceutics 2024, Vol. 16, Page 1555 2024, 16, 1555–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitew, A.; Abebaw, Y. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Species distribution of Candida and their antifungal susceptibility pattern. BMC Women's Health 2018, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaddar, N.; Anastasiadis, E.; Halimeh, R.; Ghaddar, A.; Dhar, R.; Alfouzan, W.; Yusef, H.; El Chaar, M. Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of Candida albicans causing vaginal discharge among pregnant women in Lebanon. BMC Infectious Diseases 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V.; Banerjee, T.; Kumar, P.; Pandey, S.; Tilak, R. Emergence of non-albicans Candida among candidal vulvovaginitis cases and study of their potential virulence factors, from a tertiary care center, North India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2013, 56, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfouzan, W.; Dhar, R.; Ashkanani, H.; Gupta, M.; Rachel, C.; Khan, Z.U. Species spectrum and antifungal susceptibility profile of vaginal isolates of Candida in Kuwait. Journal de mycologie medicale 2015, 25, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolt, T.M.; Klafke, G.B.; Gonçalves, C.V.; Bitencourt, L.R.; Martinez, A.M.B.d.; Mendes, J.F.; Meireles, M.C.A.; Xavier, M.O. Prevalence of Candida spp. in cervical-vaginal samples and the in vitro susceptibility of isolates. Brazilian journal of microbiology : [publication of the Brazilian Society for Microbiology] 2017, 48, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Ji, T.; Meng, L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Lu, B.; et al. Detection of Candida species in pregnant Chinese women with a molecular beacon method. Journal of medical microbiology 2018, 67, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intra, J.; Sala, M.R.; Brambilla, P.; Carcione, D.; Leoni, V. Prevalence and species distribution of microorganisms isolated among non-pregnant women affected by vulvovaginal candidiasis: A retrospective study over a 20 year-period. Journal of Medical Mycology 2022, 32, 101278–101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Kan, S.; Pang, Q.; Mei, H.; Zheng, H.; Li, D.; Cui, F.; Lv, G.; An, R.; Li, P.; et al. A prospective study on vulvovaginal candidiasis: multicentre molecular epidemiology of pathogenic yeasts in China. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV 2022, 36, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anh, D.N.; Hung, D.N.; Tien, T.V.; Dinh, V.N.; Son, V.T.; Luong, N.V.; Van, N.T.; Quynh, N.T.N.; Van Tuan, N.; Tuan, L.Q.; et al. Prevalence, species distribution and antifungal susceptibility of Candida albicans causing vaginal discharge among symptomatic non-pregnant women of reproductive age at a tertiary care hospital, Vietnam. BMC infectious diseases 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, J.C.; Wilson, J.; Roberts, K.; Armitage, C.; Barton, R.C. Increasing rate of non-Candida albicans yeasts and fluconazole resistance in yeast isolates from women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis in Leeds, United Kingdom. Sexually Transmitted Infections 2025, 101, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Matehkolaei, A.; Shafiei, S.; Zarei-Mahmoudabadi, A. Isolation, molecular identification, and antifungal susceptibility profiles of vaginal isolates of Candida species. Iranian Journal of Microbiology 2016, 8, 410–410. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Ruan, H.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, W.; Qiu, J.; Song, W.; Zhang, C.; Xue, F.; Qin, T.; et al. Oteseconazole versus fluconazole for the treatment of severe vulvovaginal candidiasis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 trial. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2023, 68, e00778–00723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, J.D.; Sobel, R. Current treatment options for vulvovaginal candidiasis caused by azole-resistant Candida species. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018, 19, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sobel, J.D.; White, T.C. A Combination Fluorescence Assay Demonstrates Increased Efflux Pump Activity as a Resistance Mechanism in Azole-Resistant Vaginal Candida albicans Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 5858–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Gao, J.; Tang, Z.; Chen, H.; Ying, C. Clonal spread and azole-resistant mechanisms of non-susceptible Candida albicans isolates from vulvovaginal candidiasis patients in three Shanghai maternity hospitals. Med Mycol 2018, 56, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sae-Tia, S.; Fries, B.C. Candidiasis and Mechanisms of Antifungal Resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfali, E.; Erami, M.; Fattahi, M.; Nemati, H.; Ghasemi, Z.; Mahdavi, E. Analysis of molecular resistance to azole and echinocandin in Candida species in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Curr Med Mycol 2022, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlin, D.S. Echinocandin Resistance in Candida. Clin Infect Dis 2015, 61 Suppl 6, S612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Perlin, D.S. Echinocandin resistance: an emerging clinical problem? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2014, 27, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlin, D.S. Echinocandin resistance, susceptibility testing and prophylaxis: implications for patient management. Drugs 2014, 74, 1573–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsonis, N.A.; Saah, A.; Lipka, C.J.; Taylor, A.; Sable, C.A. Second-line therapy with caspofungin for mucosal or invasive candidiasis: results from the caspofungin compassionate-use study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004, 53, 878–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Lasso, M.; Betts, R.; Klimko, N.; Vazquez, J.; Dobb, G.; Velez, J.; Williams-Diaz, A.; Lipka, J.; Taylor, A.; et al. Caspofungin for the treatment of less common forms of invasive candidiasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 60, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdag, D.; Pullukcu, H.; Yamazhan, T.; Metin, D.Y.; Sipahi, O.R.; Ener, B.; Isikgoz Tasbakan, M. Anidulafungin treatment for fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans vaginitis with cross-resistance to azoles: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol 2021, 41, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, D.; Akanmu, M.H.; Al Mutair, A.; Alhumaid, S.; Rabaan, A.A.; Hajissa, K. Global Prevalence of Antifungal-Resistant Candida parapsilosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2022, 7, 188–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, L.; Kean, R.; McKloud, E.; O'Donnell, L.E.; Metcalfe, R.; Jones, B.L.; Ramage, G. Biofilms Formed by Isolates from Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Patients Are Heterogeneous and Insensitive to Fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soll, D.R.; Galask, R.; Isley, S.; Rao, T.V.; Stone, D.; Hicks, J.; Schmid, J.; Mac, K.; Hanna, C. Switching of Candida albicans during successive episodes of recurrent vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol 1989, 27, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, D.M.; Coste, A.; Ischer, F.; Jacobsen, M.D.; Odds, F.C.; Sanglard, D. Genetic dissection of azole resistance mechanisms in Candida albicans and their validation in a mouse model of disseminated infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rex, J.H.; Nelson, P.W.; Paetznick, V.L.; Lozano-Chiu, M.; Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Anaissie, E.J. Optimizing the correlation between results of testing in vitro and therapeutic outcome in vivo for fluconazole by testing critical isolates in a murine model of invasive candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998, 42, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyirjesy, P.; Brookhart, C.; Lazenby, G.; Schwebke, J.; Sobel, J.D. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: A Review of the Evidence for the 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, S162–S168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinosoglou, K.; Schinas, G.; Polyzou, E.; Tsiakalos, A.; Donders, G.G.G. Probiotics in the Management of Vulvovaginal Candidosis. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.G.G.; Viera Baptista, P. The ReCiDiF method to treat recurrent vulvovaginal candidosis: A friend with benefits. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2018, 58, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donders, G.G.; Bellen, G.; Mendling, W. Management of recurrent vulvo-vaginal candidosis as a chronic illness. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2010, 70, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).