Submitted:

11 April 2024

Posted:

15 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

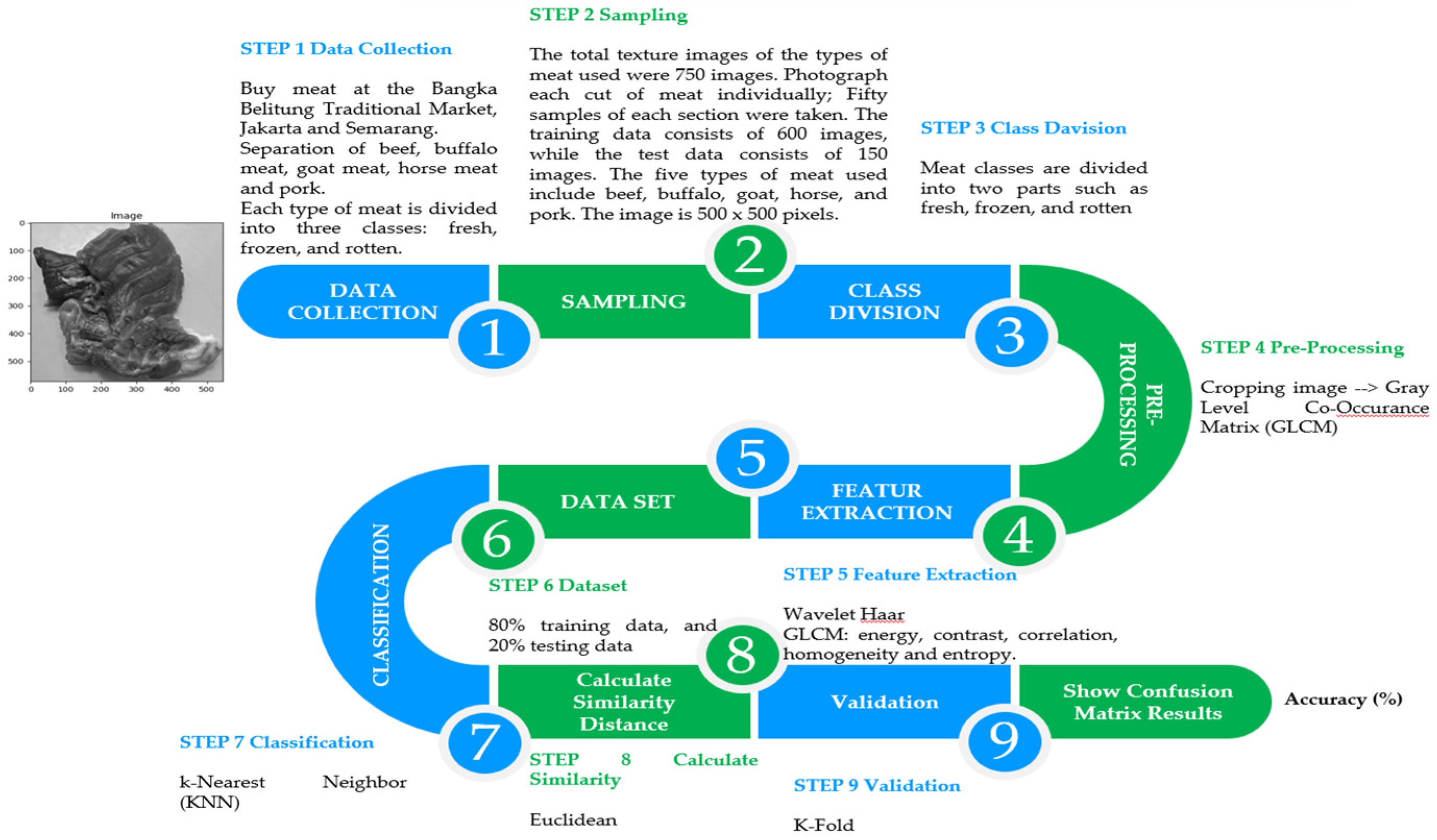

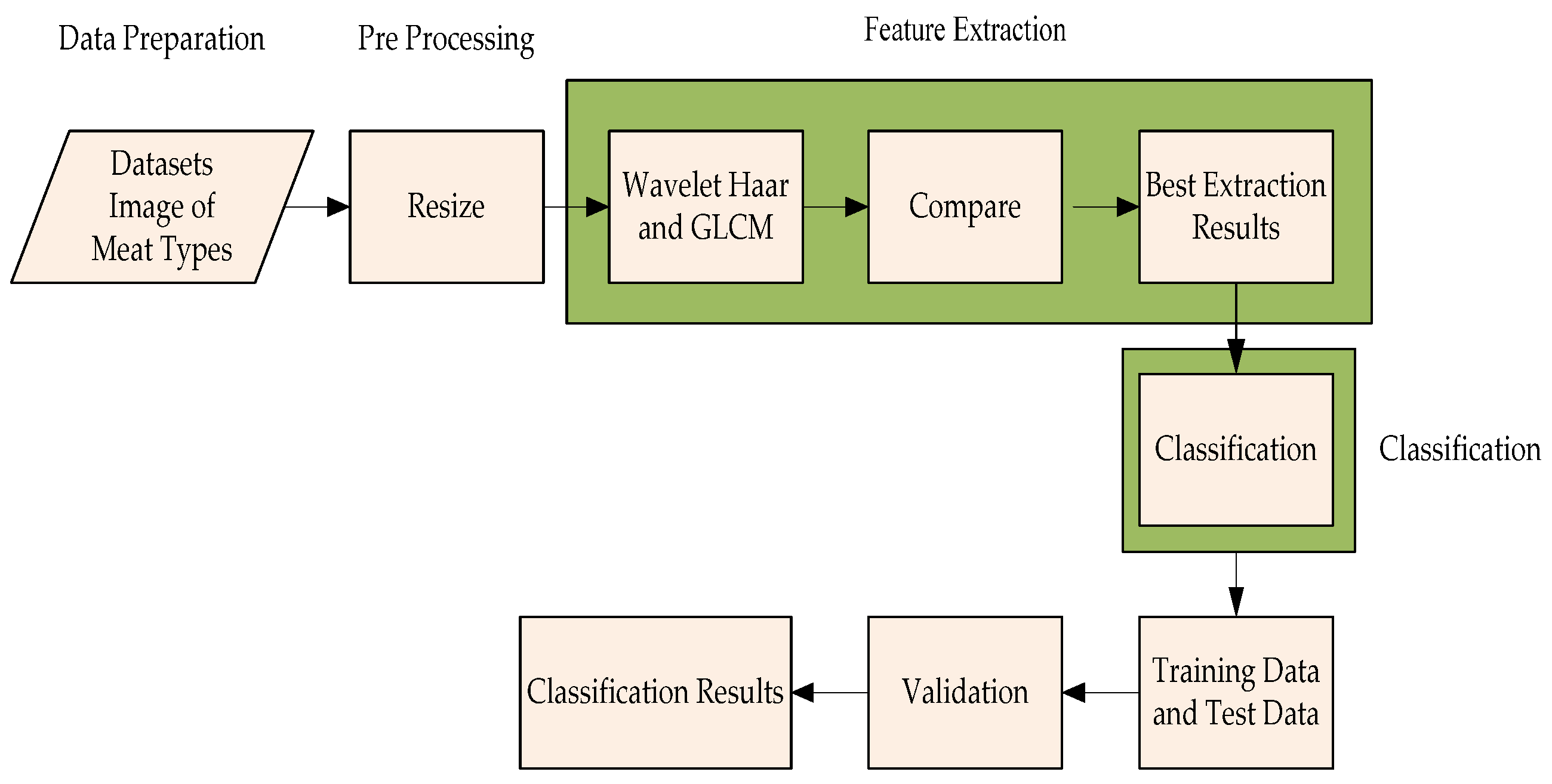

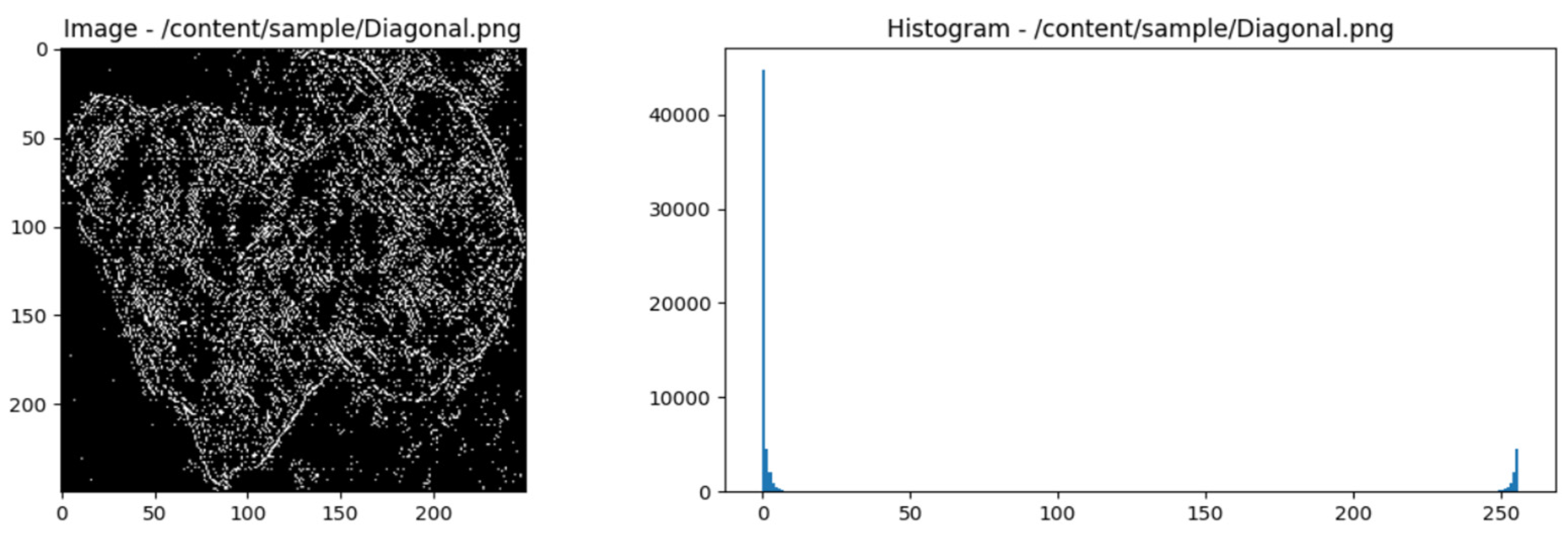

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Retrieval

2.2. Pre-Processing

2.3. Feature Extraction

2.4. Meat Sample Collection

2.5. Sampling

2.6. k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN)

| : euclidien distance between vector x and y | |

| : distance testing data to training data | |

| : testing data -j, with j = 1,2,..., n | |

| : training data -j, with j = 1,2,...., n | |

| : amount of feature. |

- The distance metric used to calculate the proximity between data points should be chosen. Euclidean distance is the distance metric that is employed.

- Using the Euclidean distance metric, determine the distance to each data point in the training dataset and the distance for each test data point.

- After computing the distance, find the k-nearest neighbours; see the test data points' k-nearest neighbours based on the most negligible distance value. Sorting the calculated distances and choosing the lowest K value will do this.

- Predicting a class (classification) As the class prediction for the test data point, if the task involves classification, ascertain the majority class of the k-nearest neighbours.

2.6.1. Performance Evaluation of Classification Results

- True Negative (TN): The number of negative observations correctly predicted by the model.

- False Positive (FP): The number of negative observations incorrectly predicted as positive by the model (Type I error).

- False Negative (FN): The number of positive observations incorrectly predicted as negative by the model (Type II error).

2.6.2. Validation

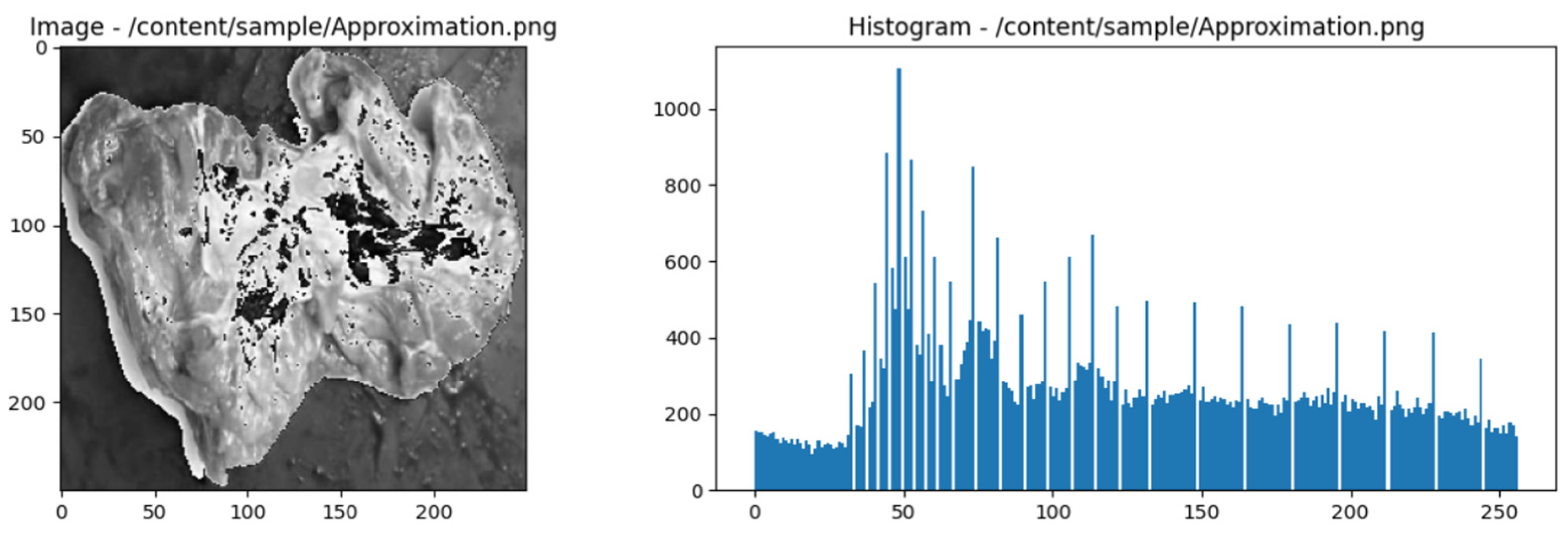

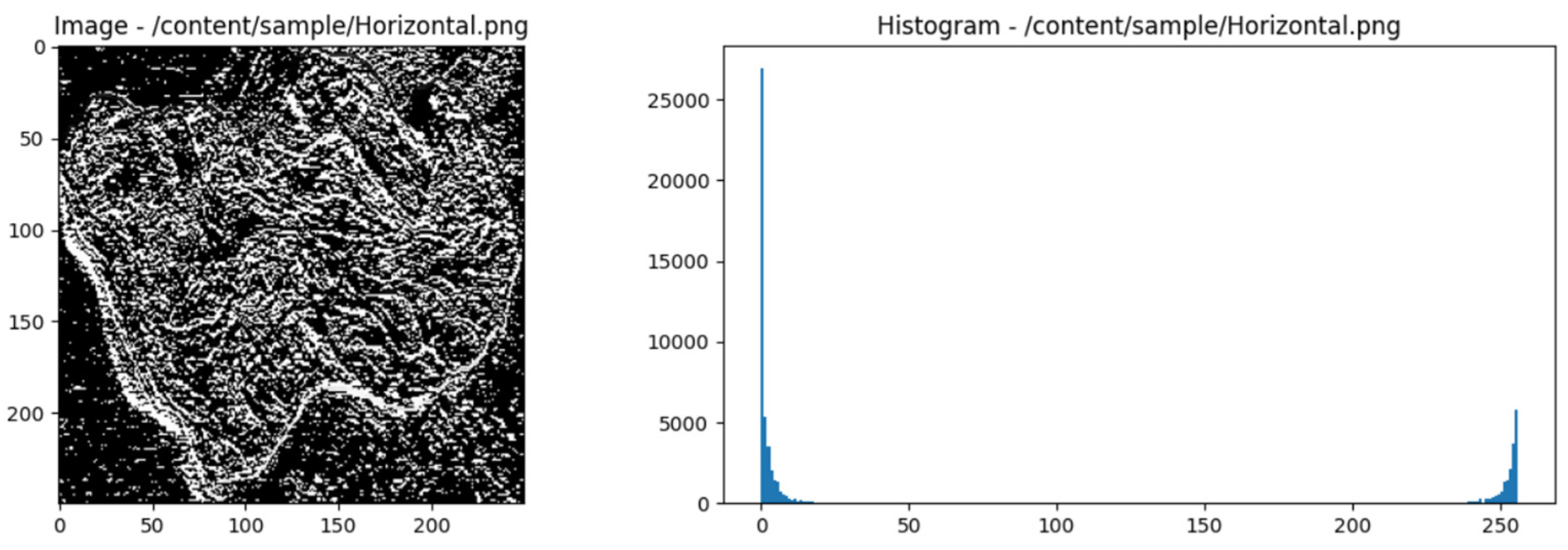

2.7. Wavelet Haar

- Approximation Coefficient:

- Detailed Coefficients:

- Intervals for texture photos of different kinds of meat are divided into smaller intervals. A convolution operation on neighbouring intervals or the average of two successive values can accomplish this.

- Once the intervals have been separated, compute the approximation coefficient (A) and the detail coefficient (D). The ap-proximation coefficient represents the finer details or low-frequency components in a meat type's texture image. Detail coefficients represent high-frequency elements or information that is coarser or changes more quickly.

- Normalize the coefficient values to suit the requirements of a particular use case. Scale adjustments or weight assignments could be part of this process.

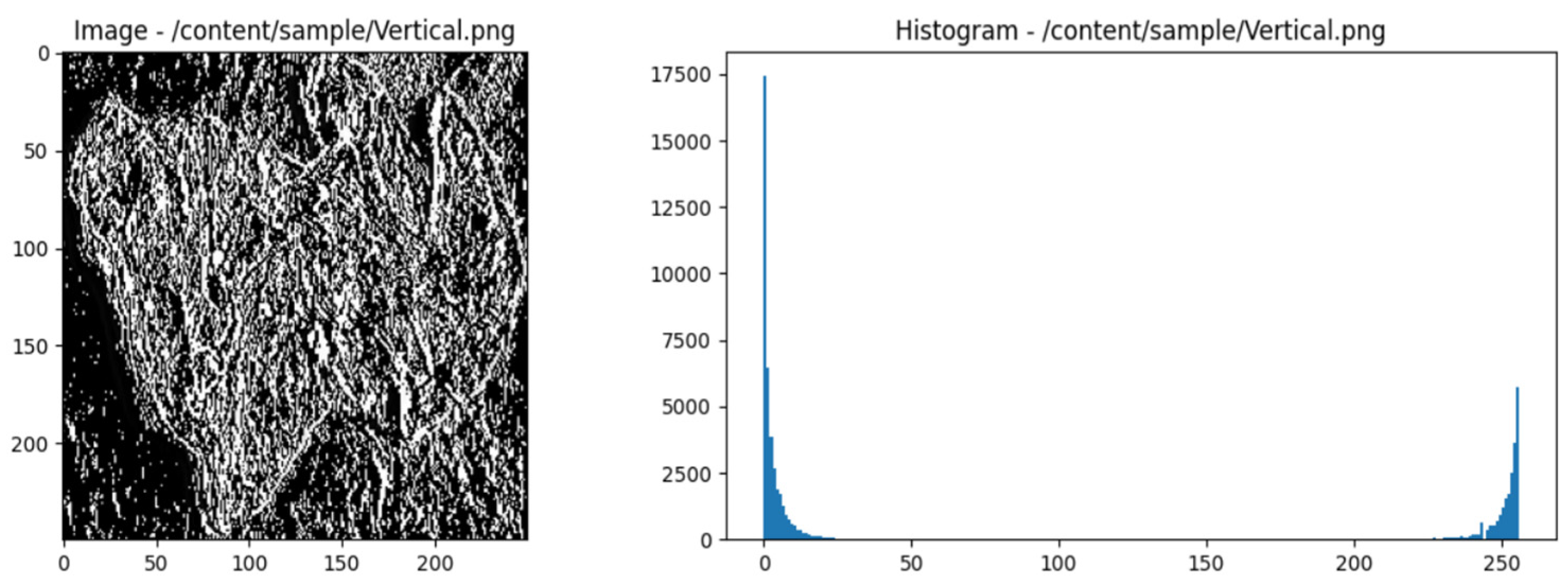

2.8. Gray Level Co-Occurrence Matrix (GLCM)

- is the image's pixel intensity at coordinates (m, n).

- is a delta function that returns one if the statement in parentheses is accurate and 0 otherwise.

- M is the number of image rows.

- N is the number of image columns.

- Select horizontal direction and distance 1.

-

Count the pairs of pixels that appear together:

- Scan the image to identify pairs of pixels with matching intensities.

- Pixel pairs that appear together are: (1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4), (2, 2), (3, 3), (4, 4 ), (1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3), (3, 4), (2, 2), (3, 3), (4, 4).

-

Create GLCM Matrix:

- Count the occurrences of pixel pairs and insert them into the GLCM matrix.

-

GLCM Matrix Normalization:

- Normalize the matrix to obtain a probability distribution.

- is the image's pixel intensity at coordinates (m, n).

- is a delta function that returns one if the statement in parentheses is accurate and 0 otherwise.

- M is the number of image rows.

- N is the number of image columns.

- Select horizontal direction and distance 1.

-

Count the pairs of pixels that appear together:

- Scan the image to identify pairs of pixels with matching intensities.

- Pixel pairs that appear together are: (1, 1), (2, 2), (1, 1), (3, 4), (2, 2), (1, 1), (4, 4), (2, 2), (2, 2), (3, 3), (4, 4), (2, 2), (2, 2), (4, 4).

-

Create GLCM Matrix:

- Count the occurrences of pixel pairs and insert them into the GLCM matrix.

-

GLCM Matrix Normalization:

- Normalize the matrix to obtain a probability distribution.

- is the image's pixel intensity at coordinates (m, n).

- is a delta function that returns one if the statement in parentheses is accurate and 0 otherwise.

- M is the number of image rows.

- N is the number of image columns.

- Select horizontal direction and distance 1.

-

Count the pairs of pixels that appear together:

- Scan the image to identify pairs of pixels with matching intensities.

- Pixel pairs that appear together are: (1, 1), (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3), (2, 2), (3, 3), (4, 4), (1, 1), (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3), (2, 2), (3, 3), (4, 4).

-

Create GLCM Matrix:

- Count the occurrences of pixel pairs and insert them into the GLCM matrix.

-

GLCM Matrix Normalization:

- Normalize the matrix to obtain a probability distribution.

-

Direction and Distance SelectionThe selection of direction and distance holds significance as it influences the measurement of the relationship between pixels. This has an impact on the texture information that is taken from the picture.

-

GLCM Matrix CalculationCounting the occurrences of particular pairs of pixel intensities at specific distances and directions is necessary to calculate a GLCM matrix. The end product is a matrix displaying the frequency of particular pairs of pixels occurring together.

-

Matrix NormalizationMatrix normalisation is applied to determine the probability distribution of pixel pair appearances. This probability distribution can calculate the likelihood that a pair of pixels will appear about the image's overall size.

-

Feature Extraction from Matrix NormalizationAfter normalisation, numerous texture properties, including energy, contrast, correlation, homogeneity, and entropy, can be retrieved from the matrix. Every element offers distinct details regarding the textural characteristics of the picture

-

Texture Statistics and CharacteristicsEnergy calculations can see the degree to which pixel intensity approaches a given value. The difference in the intensities of neighbouring pixels is referred to as contrast. The degree of correlation between pixel brightness within a specific distance and direction is reflected in correlation. The degree of uniformity in pixel intensity distribution across the image is known as homogeneity. The degree of uncertainty in the pixel intensity distribution is measured by entropy.

2.9. System Implementation and Testing

-

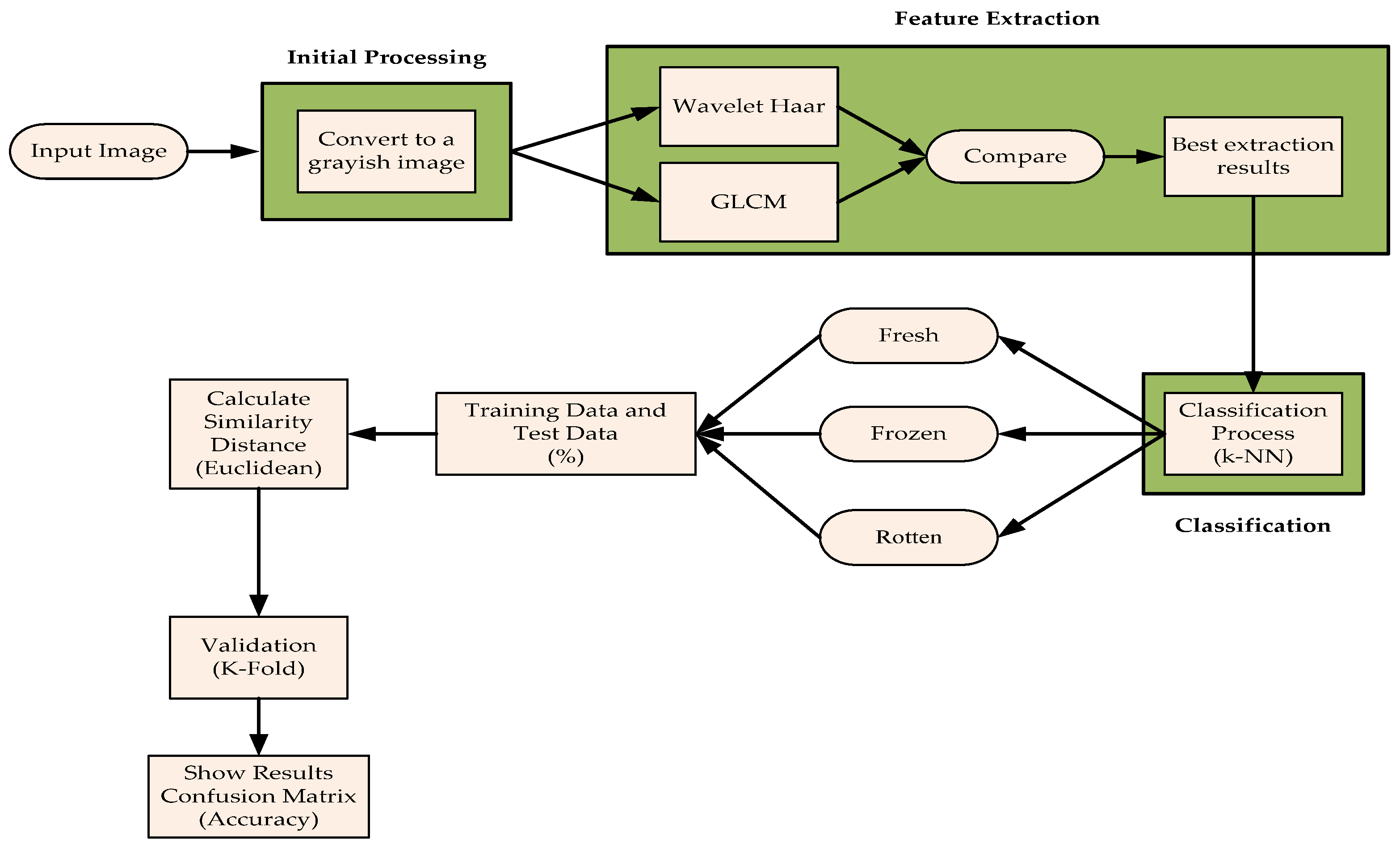

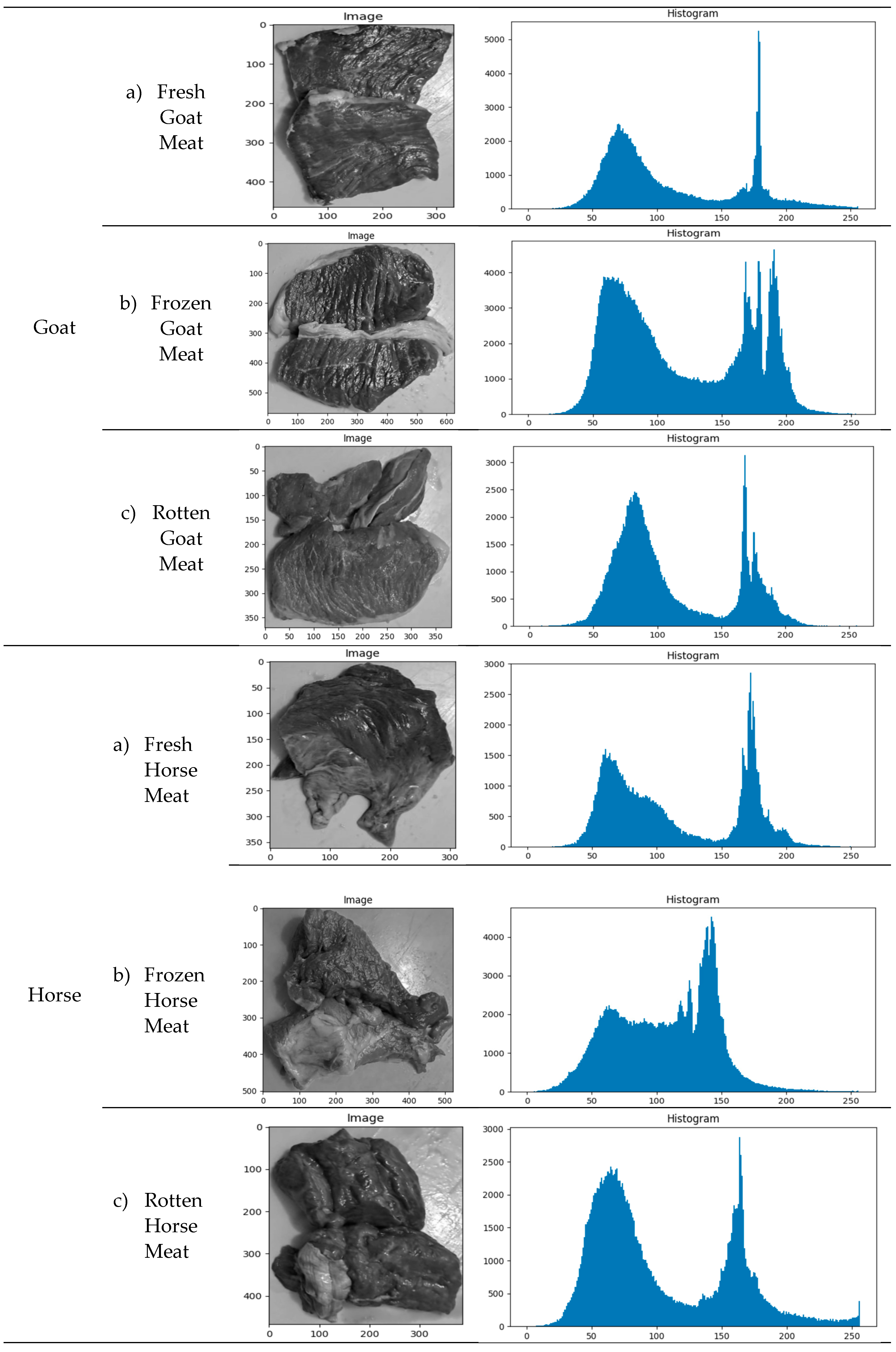

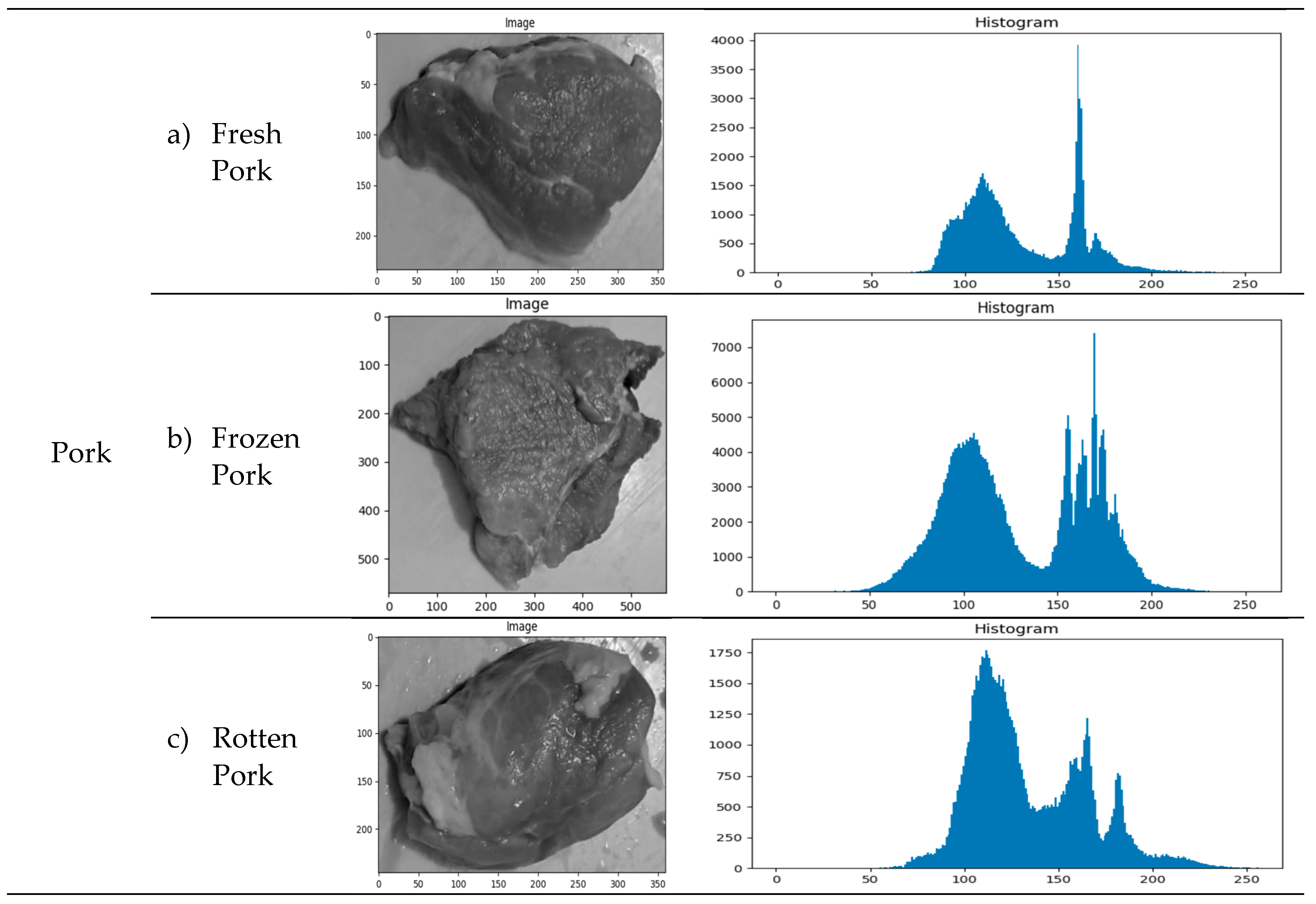

Number of samples and classificationSeven hundred and fifty images show various types of meat textures. Every kind of meat has three categories: fresh, frozen and rotten. There are fifty texture images for each class of beef and 150 images per type of meat.

-

Dataset divisionThe 600 images in the training set and the 150 in the testing set form the two main parts of the dataset. Sharing these datasets is essential so that models can be trained and their performance can be tested objectively.

-

Type of meat testedFive different kinds of meat were tested: pork, goat, horse, buffalo, and beef. Each sort of meat has three texture grades: fresh, frozen, and rotten.

-

Use of digital camerasA digital camera with the same light intensity and distance takes images that form a meat texture data set. This is important to guarantee constant shooting conditions.

-

Image sizeThere are 500x500 pixels in the image. This site offers enough resolution to allow for detailed texture investigation.

-

Example of image acquisition resultsExamples of the results of taking texture photos for each class of meat are shown in Table 2. Understanding the range of images tested and used in the categorization process is crucial.

-

Distribution of GLCM ValuesThe distribution of GLCM values based on the meat-type image histogram is shown in Table 2. This examination makes understanding textural characteristics that can be retrieved and applied to the classification process possible.

3.0. Classification

3.1. Histogram

- is the frequency of occurrence of the pixel intensity to-

- is the number of pixels with intensity to-

- is the total number of pixels in the image.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experiment Results

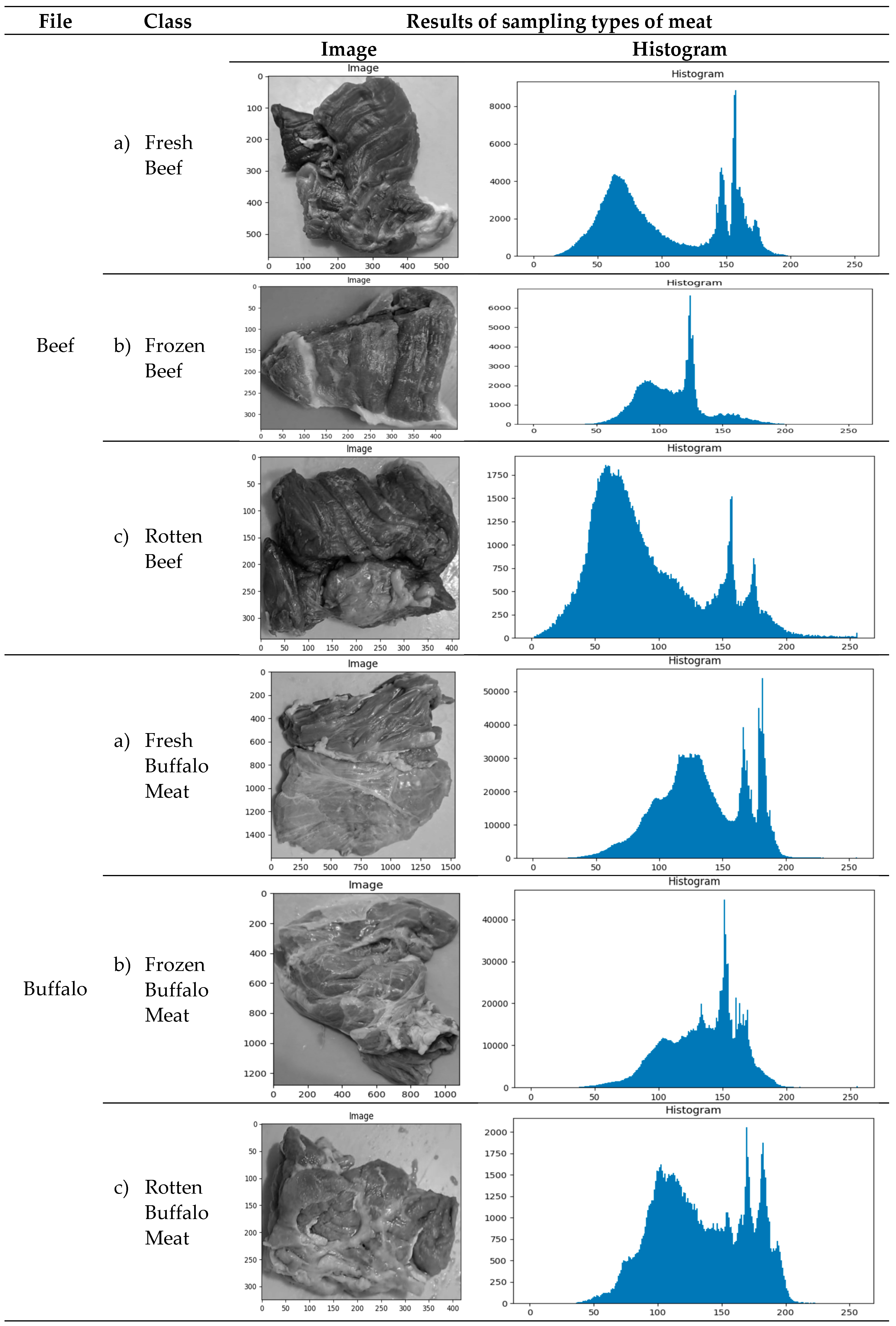

3.2. Feature Selection Result

| Author | Structure | Texture Analysis Method (Features) | Method | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yudhana, Anton Umar, Rusydi Saputra, Sabarudin[36] | Fish | RGB colors and GLCM features | k-NN | 94% |

| Don Africa, Aaron M Claire Alberto, Stephanie T Evan Tan, Travis Y[62] | Beef and pork | Skewness, Kurtosis, Mean, and Std Deviation | k-NN | 98.6% |

| Wijaya, Dedy Rahman Sarno, Riyanarto Zulaika, Enny[63] | beef | Regression results (black: actual, blue: prediction, red: prediction with error | Discrete Wavelets Transform and Long Short-Term Memory (DWTLSTM) dan k-nearest neighbour (k-NN) | 85,05% |

| Kiswanto, Hadiyanto, and Eko Sediyon[2] | Beef, buffalo, goat, horse and pork | RGB, GLCM and HSV | Haar wave algorithm | 76.72% |

| Ayaz, Hamail Ahmad, Muhammad Mazzara, Manuel Sohaib, Ahmed[64] | Meat | HSI | k-NN | 82% |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Ayu Aisah, A. Hanifa Setyaningrum, L. Kesuma Wardhani, and R. Bahaweres, “Identifying Pork Raw-Meat Based on Color and Texture Extraction Using Support Vector Machine,” 2020 8th Int. Conf. Cyber IT Serv. Manag. CITSM 2020, no. c, 2020. [CrossRef]

- and E. S. Kiswanto, Hadiyanto, Modification of the Haar Wavelet Algorithm for Texture Identification of Types of Meat Using Machine. Springer Nature Singapore, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. H. H, S. Madenda, and S. Widiyanto, “Comparison of Beef Marbling Segmentation by Experts towards Computational Techniques by Using Jaccard , Dice and Cosine Comparison of Beef Marbling Segmentation by Experts towards Computational Techniques by Using Jaccard , Dice and Cosine,” vol. 12, no. 13, pp. 623–627, 2021.

- H. H. Handayani and A. F. N. Masruriyah, “Determination of beef marbling based on fat percentage for meat quality,” Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 8394–8401, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Adi, S. Pujiyanto, O. D. Nurhayati, and A. Pamungkas, “Beef quality identification using color analysis and k-nearest neighbor classification,” Proc. - 2015 4th Int. Conf. Instrumentation, Commun. Inf. Technol. Biomed. Eng. ICICI-BME 2015, pp. 180–184, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. K. Uddin, M. A. M. Hossain, Z. Z. Chowdhury, and M. R. Bin Johan, “Short targeting multiplex PCR assay to detect and discriminate beef, buffalo, chicken, duck, goat, sheep and pork DNA in food products,” Food Addit. Contam. - Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess., vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 1273–1288, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Sciences et al., “Review Article Identiication of Diferent Animal Species in Meat and Meat Products: Trends and Advances,” vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 334–346, 2015.

- L. S. Dalsecco, R. M. Palhares, P. C. Oliveira, L. V. Teixeira, M. G. Drummond, and D. A. A. de Oliveira, “A Fast and Reliable Real-Time PCR Method for Detection of Ten Animal Species in Meat Products,” J. Food Sci., vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 258–265, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Li et al., “Comparative review and the recent progress in detection technologies of meat product adulteration,” Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf., vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 2256–2296, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. M. Hossain et al., “Quantitative Tetraplex Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay with TaqMan Probes Discriminates Cattle, Buffalo, and Porcine Materials in Food Chain,” J. Agric. Food Chem., vol. 65, no. 19, pp. 3975–3985, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. M. Albkosh, M. S. Hitam, W. N. J. H. Wan Yussof, A. A. K. Abdul Hamid, and R. Ali, “Optimization of discrete wavelet transform features using artificial bee colony algorithm for texture image classification,” Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng., vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 5253–5262, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun et al., “Predicting beef tenderness using color and multispectral image texture features,” Meat Sci., vol. 92, no. 4, pp. 386–393, 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. Jackman, D. W. Sun, P. Allen, N. A. Valous, F. Mendoza, and P. Ward, “Identification of important image features for pork and turkey ham classification using colour and wavelet texture features and genetic selection,” Meat Sci., vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 711–717, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ávila et al., “Magnetic Resonance Imaging, texture analysis and regression techniques to non-destructively predict the quality characteristics of meat pieces,” Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., vol. 82, no. March, pp. 110–125, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, “Accepted manuscript to appear in IJWMIP Accepted Manuscript International Journal of Wavelets, Multiresolution and Information Processing,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Wijaya, “Noise filtering framework for electronic nose signals: An application for beef quality monitoring,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 157, pp. 305–321, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Kishore, A. Issac, N. Minhas, and B. Sarkar, “Image processing based method to assess fi sh quality and freshness,” J. Food Eng., vol. 177, pp. 50–58, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Pu, A. Xie, D. W. Sun, M. Kamruzzaman, and J. Ma, “Application of Wavelet Analysis to Spectral Data for Categorization of Lamb Muscles,” Food Bioprocess Technol., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–16, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Masoumi, M. Marcoux, L. Maignel, and C. Pomar, “Weight prediction of pork cuts and tissue composition using spectral graph wavelet,” J. Food Eng., vol. 299, no. January, p. 110501, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Wijaya, R. Sarno, E. Zulaika, and S. I. Sabila, “Development of mobile electronic nose for beef quality monitoring,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 124, pp. 728–735, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Song, S. hui Wang, D. Yang, and T. yu Shi, “Combination of spectral and image information from hyperspectral imaging for the prediction and visualization of the total volatile basic nitrogen content in cooked beef,” J. Food Meas. Charact., vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 4006–4020, 2021. [CrossRef]

- I.G. Sujana and E. Putra, “Classification of Tuna Meat Grade Quality Based on Color Space Using Wavelet and k-Nearest Neighbor Algorithm,” no. November, pp. 2–4, 2023.

- V. Amin, D. Wilson, G. Rouse, and S. Udpa, “Multiresoi , Utional Texture Analysis for Ultrasound Tissue,” vol. 14, pp. 201–215, 1998.

- Y. Tao, “Wavelet-based adaptive thresholding method for image segmentation,” Opt. Eng., vol. 40, no. 5, p. 868, 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Dutta, A. Issac, N. Minhas, and B. Sarkar, “Image processing based method to assess fish quality and freshness,” J. Food Eng., vol. 177, pp. 50–58, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Kim, V. Amin, D. Wilson, G. Rouse, and S. Udpa, “Ultrasound image texture analysis for characterizing intramuscular fat content of live beef cattle,” Ultrason. Imaging, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 191–205, 1998. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Asmara et al., “Classification of pork and beef meat images using extraction of color and texture feature by Grey Level Co-Occurrence Matrix method,” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 434, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Widiyanto, “Texture Feature Extraction Based On GLCM and DWT for Beef Tenderness Classification,” 2018 Third Int. Conf. Informatics Comput., pp. 1–4.

- R. A. Asmara et al., “Chicken meat freshness identification using colors and textures feature,” 2018 Jt. 7th Int. Conf. Informatics, Electron. Vis. 2nd Int. Conf. Imaging, Vis. Pattern Recognition, ICIEV-IVPR 2018, pp. 93–98, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Santoni, D. I. Sensuse, A. M. Arymurthy, and M. I. Fanany, “Cattle Race Classification Using Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix Convolutional Neural Networks,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 59, no. Iccsci, pp. 493–502, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. E.-H. . H. M. E. . H. M. . & N. M. Ibrahim, “Muzzle feature extraction based on gray level co-occurrence matrix,” Isr. J. Vet. Med., vol. 01, pp. 16–24, 2016.

- R. Farinda, Z. Firmansyah, C. Sulton, I. G. P. S. Wijaya, and F. Bimantoro, “Beef Quality Classification based on Texture and Color Features using SVM Beef Quality Classification based on Texture and Color Features using SVM Classifier,” no. September, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Agustin and R. Dijaya, “Beef Image Classification using K-Nearest Neighbor Algorithm for Identification Quality and Freshness,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1179, no. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Jia, W. Wang, S. C. Yoon, H. Zhuang, and Y. F. Li, “Using a combination of spectral and textural data to measure water-holding capacity in fresh chicken breast fillets,” Appl. Sci., vol. 8, no. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Suhadi, P. Dina Atika, S. Sugiyatno, A. Panogari, R. Trias Handayanto, and H. Herlawati, “Mobile-based fish quality detection system using k-nearest neighbors method,” 2020 5th Int. Conf. Informatics Comput. ICIC 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A.Yudhana, R. Umar, and S. Saputra, “Fish Freshness Identification Using Machine Learning: Performance Comparison of k-NN and Naïve Bayes Classifier,” J. Comput. Sci. Eng., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 153–164, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Jiang, W. Yuan, Y. Ru, Q. Chen, J. Wang, and H. Zhou, “Feasibility of identifying the authenticity of fresh and cooked mutton kebabs using visible and near-infrared hyperspectral imaging,” Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc., vol. 282, no. July, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A.P. A. da C. Barbon et al., “Development of a flexible Computer Vision System for marbling classification,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 142, no. November, pp. 536–544, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Sabilla, R. Sarno, K. Triyana, and K. Hayashi, “Deep learning in a sensor array system based on the distribution of volatile compounds from meat cuts using GC–MS analysis,” Sens. Bio-Sensing Res., vol. 29, no. July, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Matera et al., “Discrimination of Brazilian artisanal and inspected pork sausages: Application of unsupervised, linear and non-linear supervised chemometric methods,” Food Res. Int., vol. 64, pp. 380–386, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Gaber, A. Tharwat, A. E. Hassanien, and V. Snasel, “Biometric cattle identification approach based on Weber’s Local Descriptor and AdaBoost classifier,” Comput. Electron. Agric., vol. 122, pp. 55–66, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xiong et al., “Non-Destructive Detection of Chicken Freshness Based on Electronic Nose Technology and Transfer Learning,” Agric., vol. 13, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. González-Mohino, T. Pérez-Palacios, T. Antequera, J. Ruiz-Carrascal, L. S. Olegario, and S. Grassi, “Monitoring the processing of dry fermented sausages with a portable NIRS device,” Foods, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Varghese, S. Jain, M. Jawahar, and A. A. Prince, “Auto-pore segmentation of digital microscopic leather images for species identification,” Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., vol. 126, no. PC, p. 107049, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Fernández-Ibáñez, T. Fearn, A. Soldado, and B. de la Roza-Delgado, “Development and validation of near infrared microscopy spectral libraries of ingredients in animal feed as a first step to adopting traceability and authenticity as guarantors of food safety,” Food Chem., vol. 121, no. 3, pp. 871–877, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar, S. K. Singh, R. Singh, and A. K. Singh, “Animal biometrics: Techniques and applications,” Anim. Biometrics Tech. Appl., pp. 1–243, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen, X. Qi, M. Chen, and B. Chen, “Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry Detection of Odor Fingerprint as Markers of Rapeseed Oil Refined Grade,” J. Anal. Methods Chem., vol. 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Najam ul Hasan, N. Ejaz, W. Ejaz, and H. S. Kim, “Meat and fish freshness inspection system based on odor sensing,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 11, pp. 15542–15557, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A.V. Shik et al., “Rapid Testing of Irradissation Dose in Beef and Potatoes by Reaction-Based Optical Sensing Technique,” J. Food Compos. Anal., vol. 127, no. August 2023, p. 105946, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. S. Jiang, Rongchang, Rongchang Jiang, Jingxin Shen, Xinran Li, Rui Gao, Qinghe Zhao, “Detection and recognition of veterinary drug residues in beef using hyperspectral discrete wavelet transform and deep learning,” Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 224–232, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Malegori, L. Franzetti, R. Guidetti, E. Casiraghi, and R. Rossi, “GLCM , an image analysis technique for early detection of bio fi lm,” J. Food Eng., vol. 185, pp. 48–55, 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. P. S. Parsania and D. P. V.Virparia, “A Review: Image Interpolation Techniques for Image Scaling,” Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng., vol. 02, no. 12, pp. 7409–7414, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, T. Utkina, O. Nechyporenko, and Y. Korpan, “Development of technique for face detection in image based on binarization, scaling and segmentation methods,” Eastern-European J. Enterp. Technol., vol. 1, no. 9–103, pp. 23–31, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. DeCarli, D. G. M. Murphy, D. Teichberg, G. Campbell, and G. S. Sobering, “Local histogram correction of MRI spatially dependent image pixel intensity nonuniformity,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 519–528, 1996. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Bae and M. Kim, “A novel SSIM index for image quality assessment using a new luminance adaptation effect model in pixel intensity domain,” 2015 Vis. Commun. Image Process. VCIP 2015, pp. 5–8, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Ã and W. C. Ro, “Data processing and image reconstruction methods for pixel detectors The first transmission radiogram was measured by,” vol. 576, pp. 223–234, 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu and Z. Li, “Scale Issues in Remote Sensing: A Review on Analysis, Processing and Modeling,” pp. 1768–1793, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, W. Wang, H. Zhuang, S. C. Yoon, and H. Jiang, “Fusion of spectra and texture data of hyperspectral imaging for the prediction of the water-holding capacity of fresh chicken breast filets,” Appl. Sci., vol. 8, no. 4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Park, M. Kise, W. R. Windham, K. C. Lawrence, and S. C. Yoon, “Textural analysis of hyperspectral images for improving contaminant detection accuracy,” Sens. Instrum. Food Qual. Saf., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 208–214, 2008. [CrossRef]

- N. Ali, D. Neagu, and P. Trundle, “Evaluation of k - nearest neighbour classifier performance for heterogeneous data sets,” SN Appl. Sci., no. September, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Gallego, J. R. Rico-juan, and J. J. Valero-mas, “Efficient k -nearest neighbor search based on clustering and adaptive k values,” Pattern Recognit., vol. 122, p. 108356, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Don Africa, S. T. Claire Alberto, and T. Y. Evan Tan, “Development of a portable electronic device for the detection and indication of fireworks and firecrackers for security personnel,” Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 1194–1203, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D.R. Wijaya, R. Sarno, and E. Zulaika, “DWTLSTM for electronic nose signal processing in beef quality monitoring,” Sensors Actuators, B Chem., vol. 326, no. September 2020, p. 128931, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Ayaz, M. Ahmad, M. Mazzara, and A. Sohaib, “Hyperspectral imaging for minced meat classification using nonlinear deep features,” Appl. Sci., vol. 10, no. 21, pp. 1–13, 2020. [CrossRef]

| Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Actual Classification | Positive | TP | FN |

| Negative | FP | TN | |

| No | Type of meat | Feature Subsets | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beef | Fresh Beef | 50 |

| Frozen Beef | 50 | ||

| Rotten Beef | 50 | ||

| 2 | Buffalo | Fresh Buffalo Meat | 50 |

| Frozen Buffalo Meat | 50 | ||

| Rotten Buffalo Meat | 50 | ||

| 3 | Goat | Fresh Goat Meat | 50 |

| Frozen Goat Meat | 50 | ||

| Rotten Goat Meat | 50 | ||

| 4 | Horse | Fresh Horse Meat | 50 |

| Frozen Horse Meat | 50 | ||

| Rotten Horse Meat | 50 | ||

| 5 | Pork | Fresh Pork | 50 |

| Frozen Pork | 50 | ||

| Rotten Pork | 50 |

| Type of meat | Class | Metrics GLCM | Minimal | Maximum | Average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Correlation | Energy | Homogeneity | Entropy | |||||

| Beef | Fresh Beef | 686,14 | 0,466 | 0,016 | 0,055 | -72,23 | -72,23 | 686,14 | 122,89 |

| Frozen Beef | 552,35 | 0,454 | 0,014 | 0,063 | -72,15 | -72,15 | 552,35 | 96,15 | |

| Rotten Beef | 651,1 | 0,86 | 0,014 | 0,058 | -73,09 | -73,09 | 651,1 | 115,79 | |

| Buffalo | Fresh Buffalo Meat | 656,57 | 0,68 | 0,01 | 0,056 | -72,66 | -72,66 | 656,57 | 116,93 |

| Frozen Buffalo Meat | 551,83 | 0,644 | 0,012 | 0,056 | -73,53 | -73,53 | 551,83 | 95,80 | |

| Rotten Buffalo Meat | 583,98 | 0,056 | 0,018 | 0,053 | -72,43 | -72,43 | 583,98 | 102,33 | |

| Goat | Fresh Goat Meat | 988,17 | 0,28 | 0,015 | 0,056 | -72,48 | -72,48 | 988,17 | 183,21 |

| Frozen Goat Meat | 999,097 | 0,474 | 0,012 | 0,05 | -70,90 | -70,90 | 999,097 | 185,75 | |

| Rotten Goat Meat | 545,43 | 0,304 | 0,017 | 0,064 | -71,60 | -71,60 | 545,43 | 94,84 | |

| Horse | Fresh Horse Meat | 716,54 | 0,278 | 0,012 | 0,055 | -72,82 | -72,82 | 716,54 | 128,81 |

| Frozen Horse Meat | 624,06 | 0,488 | 0,013 | 0,06 | -73,25 | -73,25 | 624,06 | 110,28 | |

| Rotten Horse Meat | 458,32 | 0,332 | 0,02 | 0,079 | -72,17 | -72,17 | 458,32 | 77,32 | |

| Pork | Fresh Pork | 329,53 | 0,376 | 0,025 | 0,056 | -72,37 | -72,37 | 329,53 | 51,52 |

| Frozen Pork | 462,78 | 0,392 | 0,024 | 0,051 | -71,99 | -71,99 | 462,78 | 78,25 | |

| Rotten Pork | 244,98 | 0,34 | 0,029 | 0,064 | -72,30 | -72,30 | 244,98 | 34,62 | |

| Number of neighbors (k) | Class | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fresh Beef | 98.039% | 100% | 99% | 98.02% |

| Frozen Beef | 96.154% | 100% | 98% | 96.077% | |

| Rotten Beef | 94.231% | 97.917% | 96% | 92.074% | |

| 2 | Fresh Buffalo Meat | 97.959% | 96.078% | 97% | 94.019% |

| Frozen Buffalo Meat | 96.078% | 97.959% | 97% | 94.019% | |

| Rotten Buffalo Meat | 92.308% | 95.833% | 94% | 88.07% | |

| 3 | Fresh Goat Meat | 100% | 98.039% | 99% | 98.02% |

| Frozen Goat Meat | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% | |

| Rotten Goat Meat | 96% | 96% | 96% | 92% | |

| 4 | Fresh Horse Meat | 100% | 98.939% | 99% | 98.02% |

| Frozen Horse Meat | 96.154% | 100% | 98% | 96.077% | |

| Rotten Horse Meat | 94.118% | 95.918% | 95% | 90.018% | |

| 5 | Fresh Pork | 98% | 98% | 98% | 96% |

| Frozen Pork | 100% | 98.039% | 99% | 98.02% | |

| Rotten Pork | 94.231% | 97.917% | 96% | 92.074% |

| File | Class | k-NN Accuracy % |

Haar Wavelet Accuracy % |

GLCM Accuracy % |

| Beef | Fresh Beef | 99 | 89,96 | 122,89 |

| Frozen Beef | 98 | 88,25 | 96,15 | |

| Rotten Beef | 96 | 87,97 | 115,79 | |

| Buffalo | Fresh Buffalo Meat | 97 | 89,75 | 116,93 |

| Frozen Buffalo Meat | 97 | 87,96 | 95,80 | |

| Rotten Buffalo Meat | 94 | 86,88 | 102,33 | |

| Goat | Fresh Goat Meat | 99 | 89,47 | 183,21 |

| Frozen Goat Meat | 98 | 86,73 | 185,75 | |

| Rotten Goat Meat | 96 | 86,79 | 94,84 | |

| Horse | Fresh Horse Meat | 99 | 89,85 | 128,81 |

| Frozen Horse Meat | 98 | 87,56 | 110,28 | |

| Rotten Horse Meat | 95 | 86,26 | 77,32 | |

| Pork | Fresh Pork | 98 | 89,25 | 51,52 |

| Frozen Pork | 99 | 87,67 | 78,25 | |

| Rotten Pork | 96 | 86,36 | 34,62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).