Submitted:

11 April 2024

Posted:

15 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Design

- population (change in natural birthrate; change in migration balance; change in old-age dependency ratios; change in feminization rate; change in population density; change in the number of marriages),

- construction activity and housing stock (change in the number of building permits; change in the number of dwellings, including commissioned dwellings; change in the average floor area of dwellings; change in the number of persons per dwelling; change in the proportion using gas infrastructure, sewerage and water supply networks),

- land use and spatial policy (change in the share of the area covered by the existing local spatial development plans; change in the share of the area of agricultural land subject to alteration in terms of designation for non-agricultural purposes in the plans; change in the share of the area of forest land subject to alteration in designation for non-forest purposes in the plans; change in the proportion of areas designated in the study requiring switching from agricultural land use to use for non-agricultural purposes; change in the proportion of areas designated in the study requiring moving from forest land use to use for non-forest purposes; change in the proportion of parks, green spaces and residential green areas; change in the share of green areas),

- economic and investment attractiveness (change in the number of businesses - including micro-enterprises; change in the number of natural persons engaged in business activities; change in the share of PIT and CIT taxes in municipalities’ own revenues; change in the number of businesses in sections J-N, the creative sector, and the agri-food sector; change in the number of accommodation facilities and beds).

3. Results

3.1. Dimensions of Socio-Spatial Diversity of the WMA and Spheres Affected by Suburbanisation

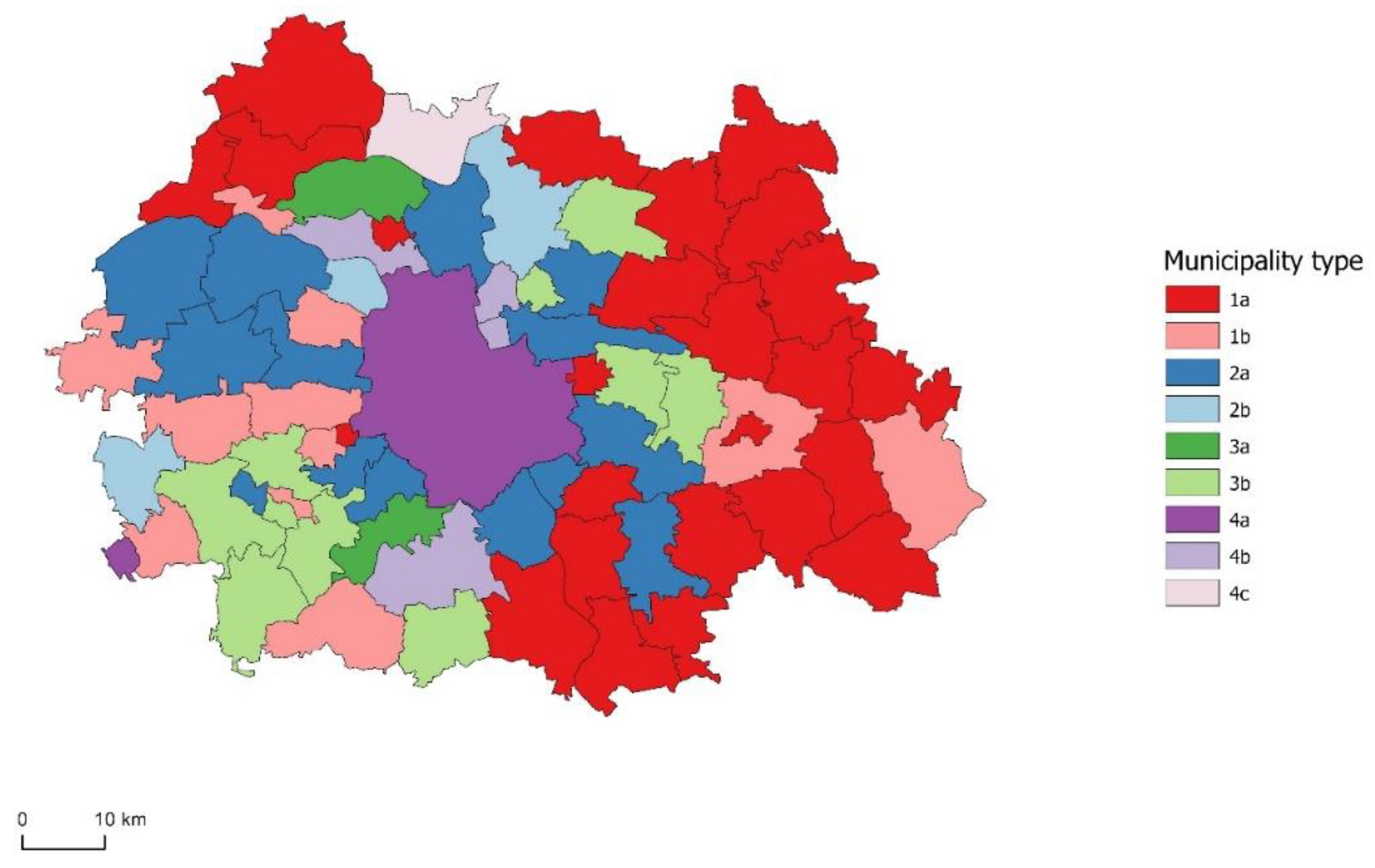

3.2. Typology of WMA Municipalities According to the Course of Suburbanisation

3.3. Changes in the Characteristics of Suburbanization Processes in the WMA and Directions of Its Potential Expansion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asikhia, M. O. , Nkeki, N. F. Polycentric employment growth and the commuting behaviour in Benin Metropolitan Region, Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Geology 2013, 5(2), 1-17.

- Brusch, I. , Brusch, M., Kozlowski, T. Factors influencing employer branding: Investigations of student perceptions outside metropolitan regions. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences 2018, 10(2), 149-162.

- Davies, W. Factorial Ecology. 1984. Gower: Aldershot.

- Grochowski, M. (ed.) Suburbanizacja. Człowiek – zmiana – przestrzeń, (Suburbanization. Man – change – space), Rządowa Rada Ludnościowa, 2023, Warszawa.

- Grochowski, M. Samorząd terytorialny a rozwój zrównoważony obszarów metropolitalnych (Local government and sustainable development of metropolitan areas). Mazowsze Studia Regionalne, 2009, 2, pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Grochowski, M. Samorządność lokalna a terytorialny wymiar rozwoju. Zarządzanie obszarami funkcjonalnymi (Local self-government and the territorial dimension of development. Management of functional areas development). Mazowsze Studia Regionalne, 2014, 15, pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hatz, G. Features and dynamics of socio-spatial differentiation in Vienna and the Vienna Metropolitan region. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 2009, 100(4), 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakayaci, Z The concept of urban sprawl and its causes, The Journal of International Social Research, 2016, vol. 9, issue 45, pp. 815-818.

- Knox, P. , Pinch S. Urban Social Geography. An Introduction. 5th edition. 2000, Harlow: Pearson.

- Korcelli, P. , Grochowski, M. , Kozubek, E., Korcelli-Olejniczak, E., Werner, P. Development of urban-rural regions: from European to local perspective. Monografie IGiPZ PAN, 2012, 4, IGiPZ PAN, Warszawa. [Google Scholar]

- Metropolia Warszawska, Available online: https://omw.um.warszawa.pl/ (accessed on 10.09.2023).

- Moisio, S. and Jonas, A.E.G. City-regions and city-regionalism. In: Handbook on the Geographies of Regions and Territories Eds. Paasi, A., Harrison, J. and M. Jones, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018, pp. 285-297.

- Podawca, K. , Karsznia, K., Pawłat-Zawrzykraj, A. The assessment of the suburbanisation degree of Warsaw Functional Area using changes of the land development structure, Miscellanea Geographica, 2019, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 215-224.

- Podawca, K. , Mrozik, K Dywersyfikacja stopnia realizacji procesów planistyczno-inwestycyjnych w gminach Warszawskiego Obszaru Funkcjonalnego (Diversification of planning and investment processes in the municipalities of Warsaw Functional Area), Scientific Review Engineering and Environmental Sciences, 2019, vol. 28(1), pp. 105-117.

- Porczek, M., Typology of Localities in the Warsaw Metropolitan Area Resulting from the Spatial Development Structure, Sustainability, 2023, 15, 15879. [CrossRef]

- Prasongthan, S. Factors affecting intention to travel of people with disabilities in Bangkok Metropolitan Region: A preliminary study. Asian Administration & Management Review 2018, 1(2).

- Ravetz, J. , Fertner, C., Nielsen, T.S. (2013). The dynamics of peri-urbanization, In: Peri-Urban Futures: Scenarios and Models for Land Use Change in Europe, Nilsson, K., Pauleit, S., Bell, S., Aalbers, C., Nielsen T.S. (Eds.),. 2013, Springer, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London, pp. 13–44.

- Śleszyński, P (ed.) 2012, Warszawa i obszar metropolitalny Warszawy a rozwój Mazowsza (Warsaw and its metropolitan area versus the development of Masovia), Trendy Rozwojowe Mazowsza, 2012, no. 8, pp. 1-160.

- Śleszyński, P. , Nowak, M., Legutko-Kobus, P., Hołuj, A., Lityński, P., Jadach-Sepioło, A., Blaszke, M. Suburbanizacja w Polsce jako wyzwanie dla polityki rozwoju (Suburbanization in Poland. Challenges for development policies), Cykl Monografii, 2021, 11/203, Komitet Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju PAN, Warszawa.

- Smętkowski, M. Socio-spatial differentiation in Warsaw: inertia or metamorphosis of the city structure? Geographia Polonica 2011, 84(2), 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A. , Huang, Y., Yang, L., Huang, C., Xiang, H. Assessment of the Impact of Basic Public Service Facility Configuration on Social–Spatial Differentiation: Taking the Zhaomushan District of Chongqing, China. Sustainability 2023, 16(1), 196.

- Wachsmuth, D. Competitive multi-city regionalism: Growth politics beyond the growth machine. Regional Studies, 2017, 51(4), 643–653.

- Webb, J.W. The natural and migrational components of population changes in England and Wales, 1921–1931. Economic Geography 1963, 392, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Change in the number of businesses in sections J-N per 1,000 inhabitants | 0.905 | 0.156 | -0.075 | 0.055 | -0.061 |

| Change in the number of entities employing up to 9 persons per 10,000 inhabitants of working age | 0.866 | 0.121 | 0.185 | 0.08 | 0.042 |

| Change in the number of businesses per 1,000 working-age population | 0.857 | 0.109 | 0.192 | 0.068 | 0.036 |

| Change in the share of PIT in the municipality’s own income | 0.796 | -0.204 | 0.102 | -0.189 | -0.047 |

| Change in the number of sole traders per 100,000 people of working age | 0.781 | 0.064 | 0.416 | 0.027 | 0.070 |

| Change in the proportion of parks, green spaces and residential green spaces in the area of the municipality | 0.465 | 0.179 | -0.246 | -0.344 | -0.290 |

| Change in the share of CIT in the municipality’s own income | 0.416 | -0.129 | -0.19 | 0.131 | -0.089 |

| Change in old-age dependency ratio | 0.094 | -0.759 | 0.044 | 0.088 | 0.030 |

| Change in the birth rate | -0.058 | 0.721 | -0.104 | 0.087 | 0.051 |

| Change in population density | 0.095 | 0.635 | -0.546 | -0.081 | 0.126 |

| Change in the proportion using gas infrastructure | 0.013 | 0.389 | 0.192 | 0.175 | 0.334 |

| Change in average floor area of commissioned dwellings per 1,000 population | 0.177 | 0.374 | 0.34 | 0.304 | 0.257 |

| Change in average floor area of 1 dwelling | 0.456 | 0.063 | 0.663 | -0.118 | 0.135 |

| Change in the number of building permits per 1,000 population | 0.131 | 0.391 | 0.524 | 0.08 | -0.232 |

| Change in the average number of persons per dwelling | 0.072 | 0.151 | 0.383 | -0.682 | -0.118 |

| Change in the number of tourism entities per 1,000 population | 0.15 | 0.024 | 0.295 | 0.669 | -0.104 |

| Change in the number of tourist accommodation establishments per 1,000 population | 0.202 | 0.043 | 0.341 | 0.663 | -0.097 |

| Change in the number of dwellings per 1,000 population | 0.269 | 0.058 | -0.53 | 0.572 | -0.085 |

| Change in the share of newly registered creative sector entities in the total number of newly registered entities | 0.203 | -0.050 | 0.060 | -0.427 | 0.070 |

| Change in migration balance | -0.336 | -0.097 | -0.126 | 0.413 | 0.258 |

| Change in the share of newly registered entities of the agri-food processing sector in the total number of newly registered entities | 0.057 | 0.107 | -0.095 | 0.281 | -0.082 |

| Change in the number of marriages per 1,000 population | 0.177 | 0.109 | -0.071 | -0.251 | 0.007 |

| Change in share of sewerage users | 0.155 | -0.063 | -0.108 | -0.180 | 0.723 |

| Change in the proportion using the water supply system | -0.095 | 0.090 | -0.046 | -0.160 | 0.673 |

| Change in share of new dwellings in total number of dwellings | -0.310 | 0.314 | 0.242 | 0.104 | 0.599 |

| Change in the proportion of agricultural land for which the plans foresee change to non-agricultural use | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.229 | -0.07 | -0.404 |

| Change in the proportion of forest land for which the plans foresee change to non-forest use | 0.114 | 0.102 | 0.156 | -0.051 | 0.397 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).